User login

Rapid Onset of Widespread Nodules and Lymphadenopathy

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous γδ T-cell Lymphoma

Primary cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphoma (PCGDTL) is a distinct entity that can be confused with other types of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas. Often rapidly fatal, PCGDTL has a broad clinical spectrum that may include indolent variants—subcutaneous, epidermotropic, and dermal.1 Primary cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphoma represents less than 1% of all cutaneous T-cell lymphomas.2 Diagnosis and treatment remain challenging. Patients typically present with nodular lesions that progress to ulceration and necrosis. Early lesions can be confused with erythema nodosum, mycosis fungoides, or infection on clinical examination; biopsy establishes the diagnosis. Typical findings include a cytotoxic phenotype, variable epidermotropism, dermal and subcutaneous involvement, and loss of CD4 and often CD8 expression. Testing for Epstein-Barr virus expression yields negative results. The neoplastic lymphocytes in dermal and subcutaneous PCGDTL typically are T-cell intracellular antigen-1 (TIA-1) and granzyme positive.1

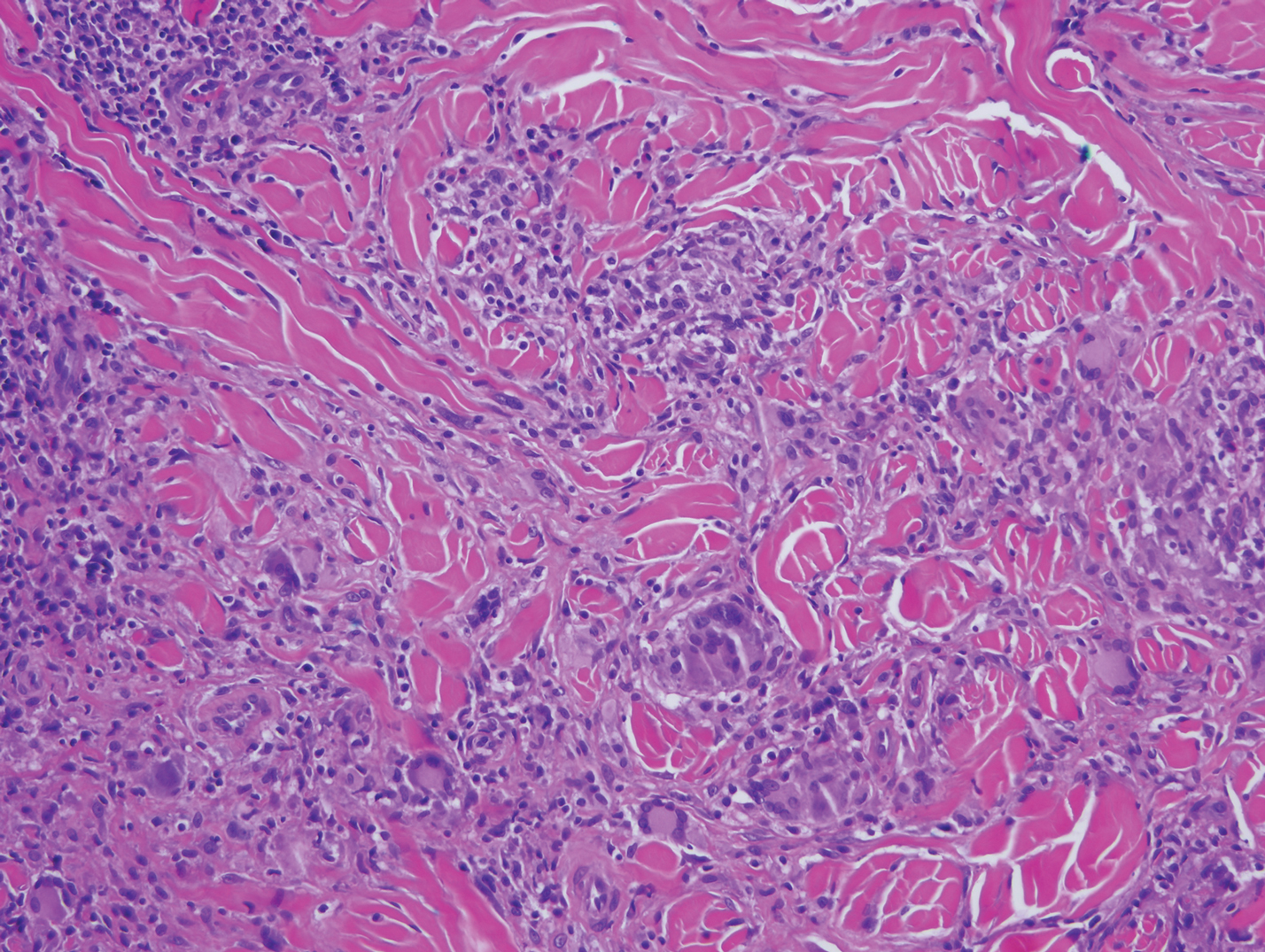

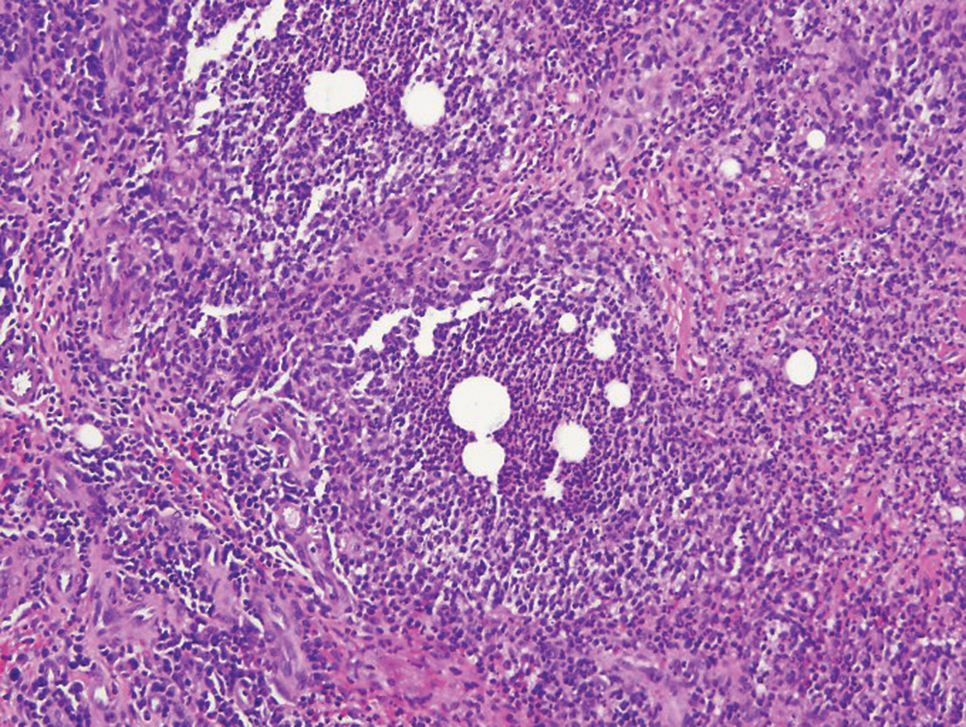

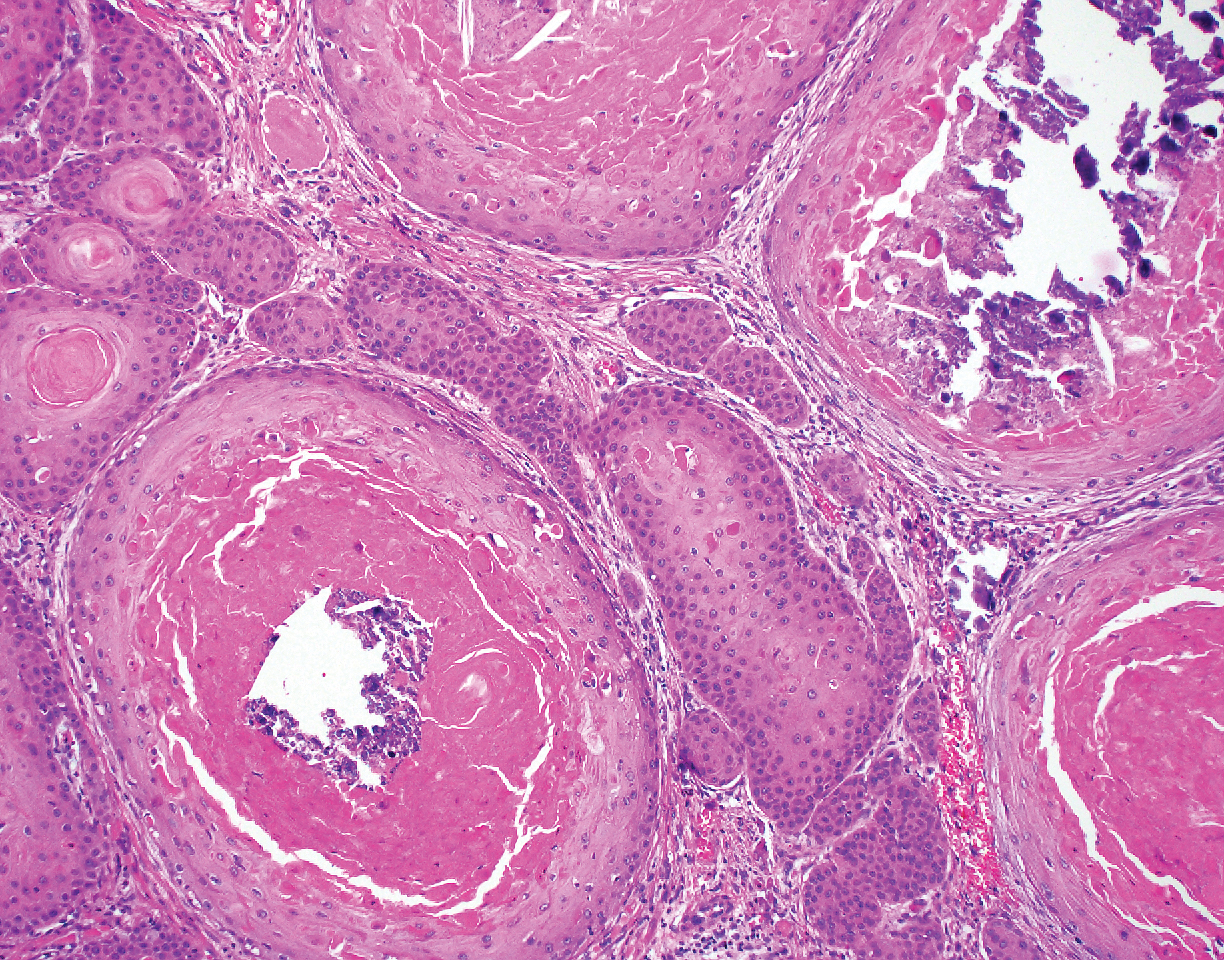

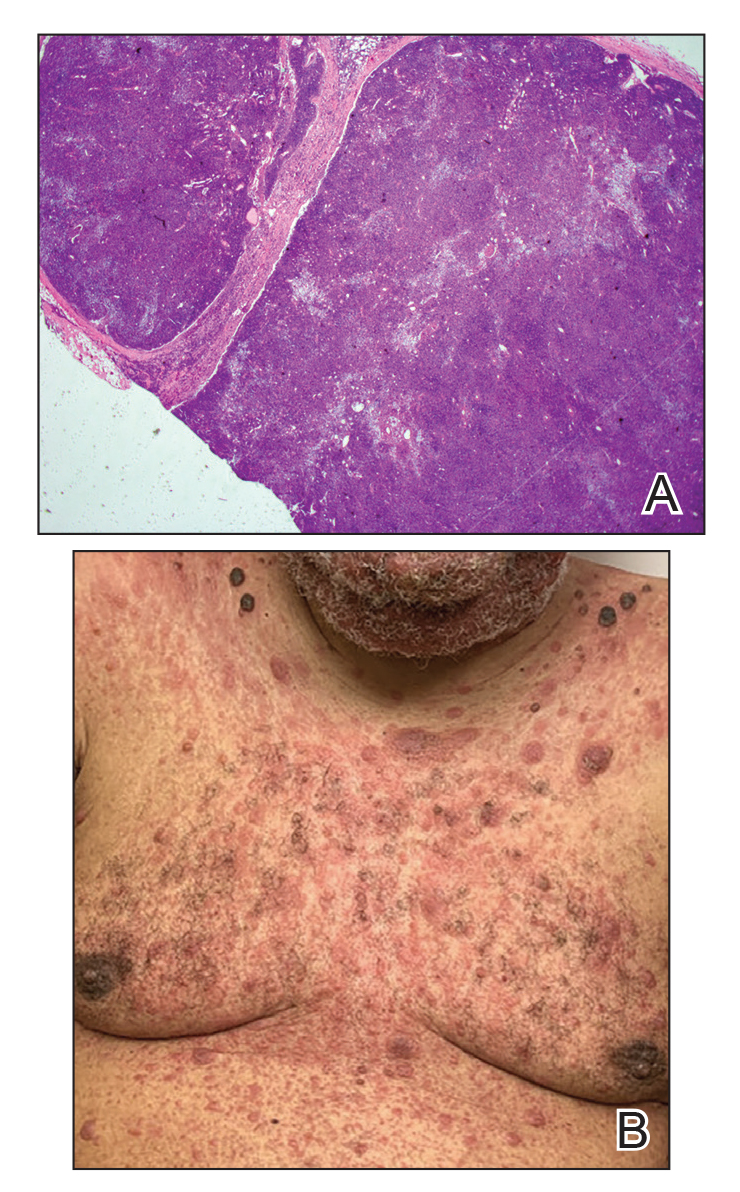

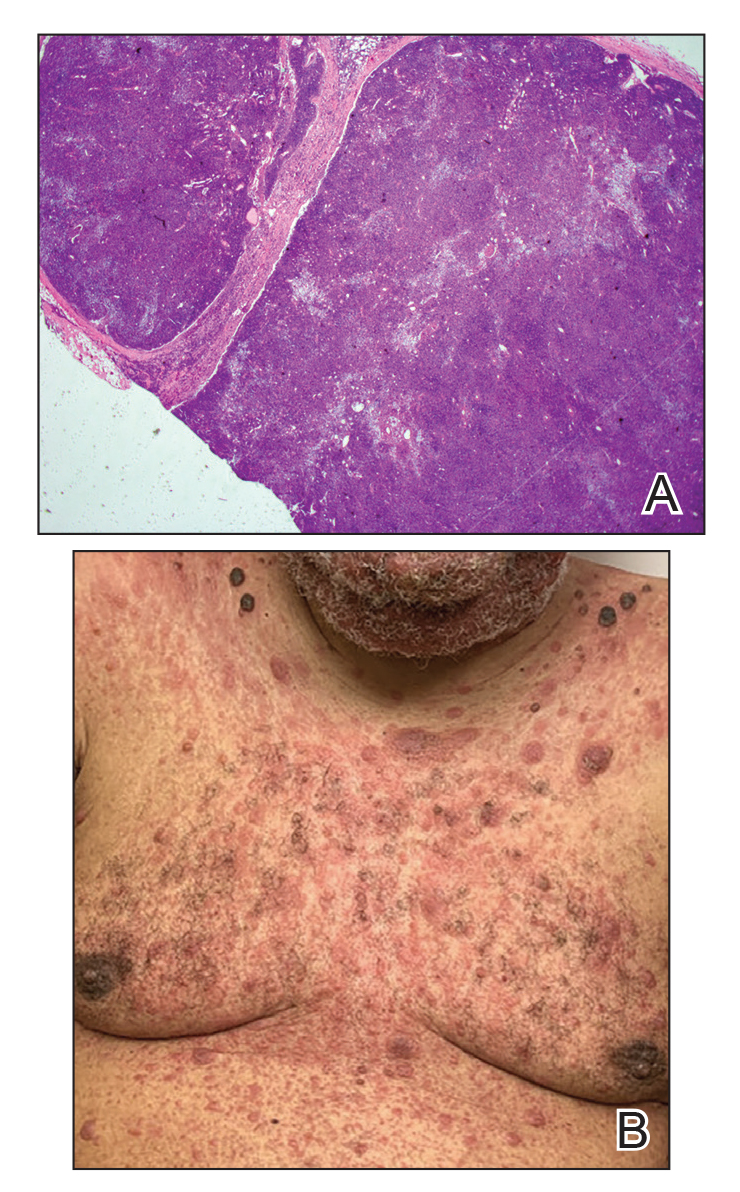

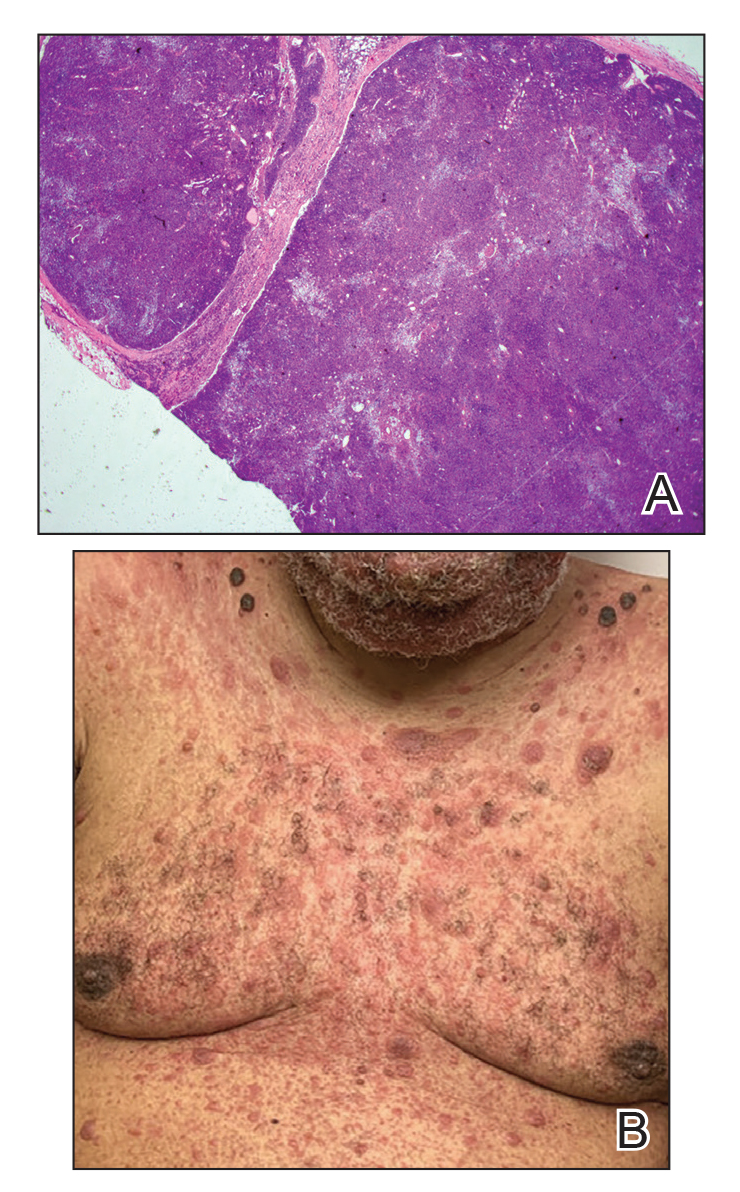

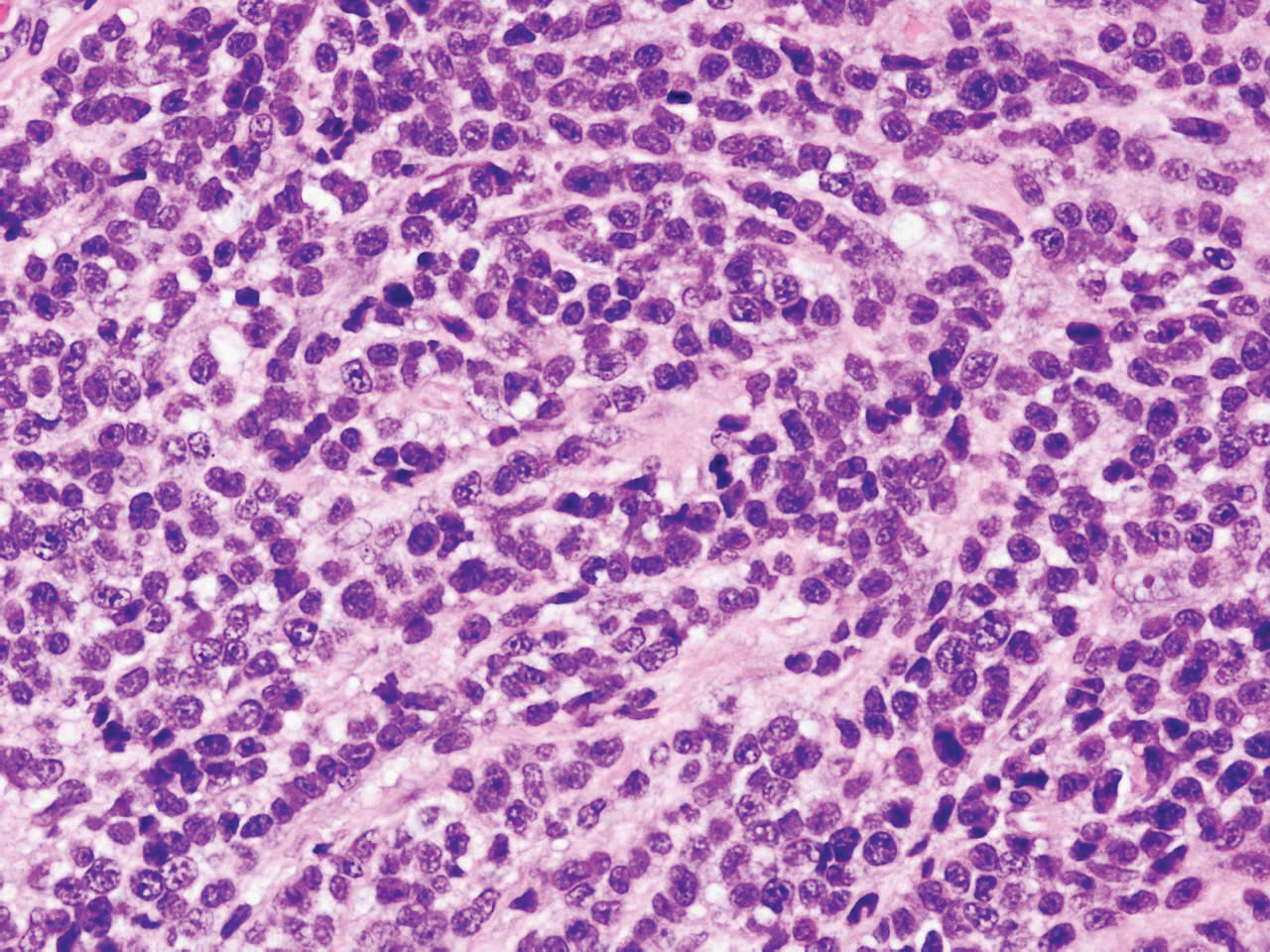

Immunohistochemistry failed to reveal CD8, CD56, granzyme, or T-cell intracellular antigen-1 staining of neoplastic cells in our patient but stained diffusely positive with CD3 and CD4. A CD20 stain decorated only a few dermal cells. The patient’s skin lesions continued to enlarge, and the massive lymphadenopathy made breathing difficult. Computed tomography revealed diffuse systemic involvement. An axillary lymph node biopsy revealed sinusoids with complete diffuse effacement of architecture as well as frequent mitotic figures and karyorrhectic debris (Figure 1A). Negative staining for T-cell receptor beta-F1 of the axillary lymph node biopsy and clonal rearrangement of the T-cell receptor gamma chain supported the diagnosis of PCGDTL. Nuclear staining for Epstein-Barr virus–encoded RNA was negative. Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 antibodies and polymerase chain reaction also were negative. Flow cytometry demonstrated an atypical population of CD3+, CD4+, and CD7− γδ T lymphocytes, further supporting the diagnosis of lymphoma.

The median life expectancy for patients with dermal or subcutaneous PCGDTL is 10 to 15 months after diagnosis.3 The 5-year life expectancy for PCGDTL is approximately 11%.2 Limited treatment options contribute to the poor outcome. Chemotherapy regimens such as CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisolone) and EPOCH (etoposide phosphate, prednisone, vincristine sulfate, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride) have yielded inconsistent results. Stem cell transplant has been tried in progressive disease and also has yielded mixed results.2 Brentuximab is indicated for individuals whose tumors express CD30.4 Associated hemophagic lymphohistiocytosis portends a poor prognosis.5

Despite treatment with etoposide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and high-dose oral steroids, our patient developed progressive difficulty breathing, stridor, kidney injury, and anemia. Our patient died less than 1 month after diagnosis—after only 1 round of chemotherapy—secondary to progressive disease and an uncontrollable gastrointestinal tract bleed. The leonine facies (Figure 1B) encountered in our patient can raise a differential diagnosis that includes infectious as well as neoplastic etiologies; however, most infectious etiologies associated with leonine facies manifest in a chronic fashion rather than with a sudden eruption, as noted in our patient.

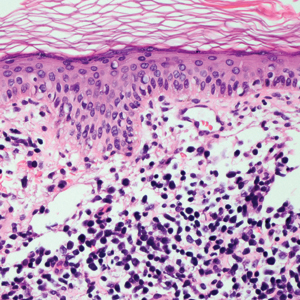

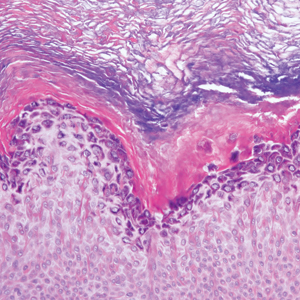

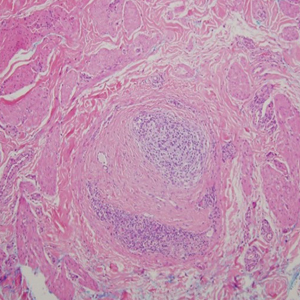

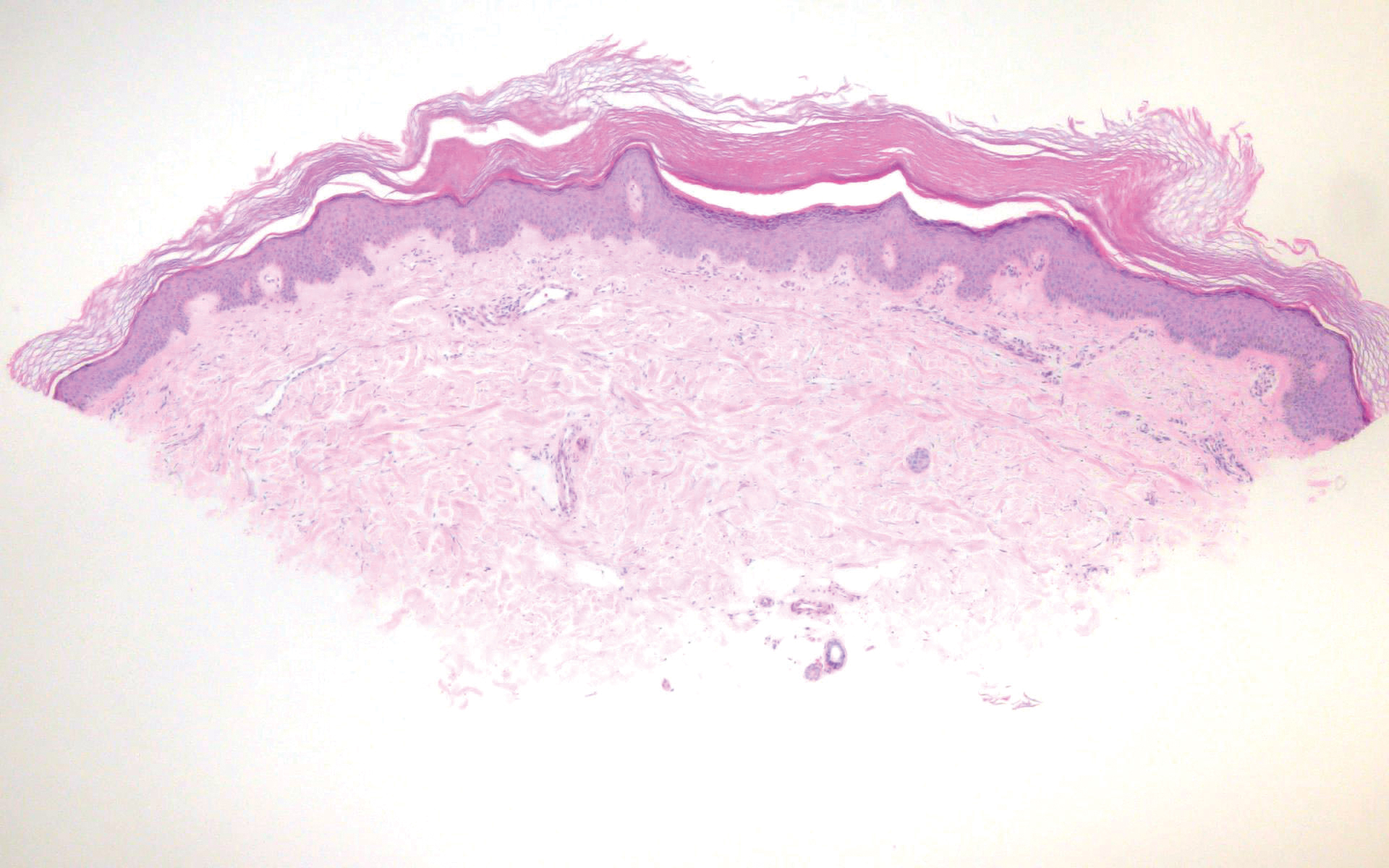

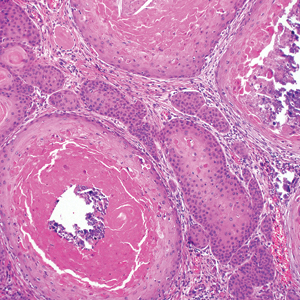

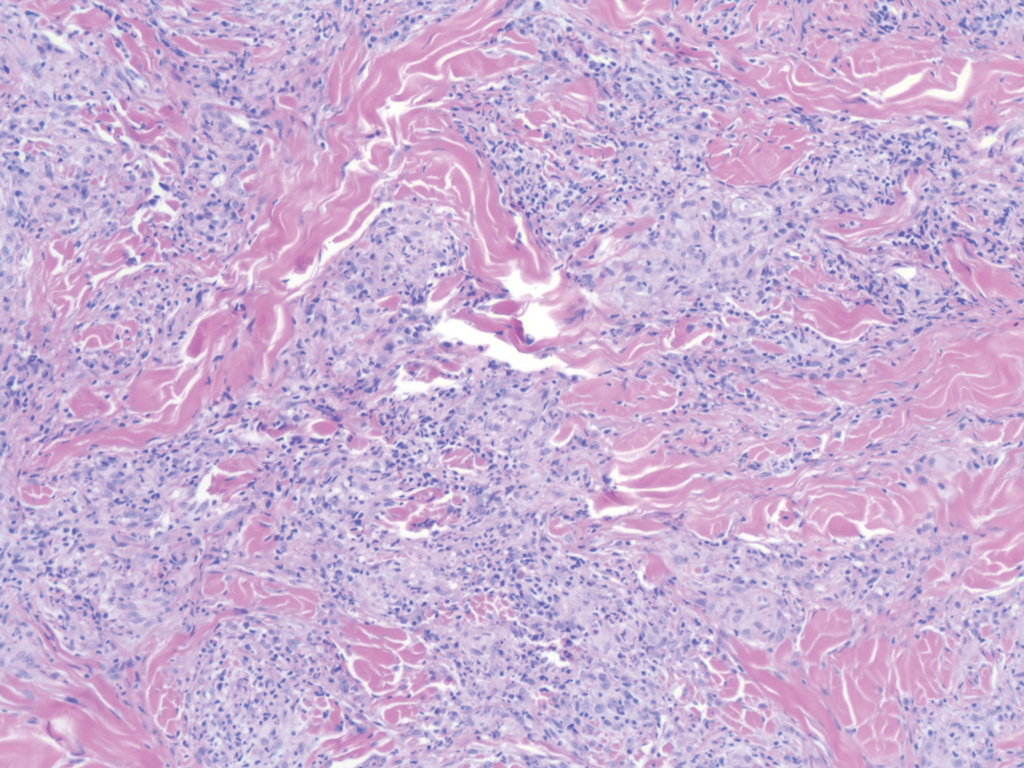

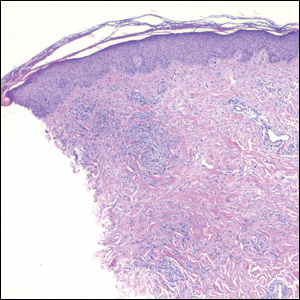

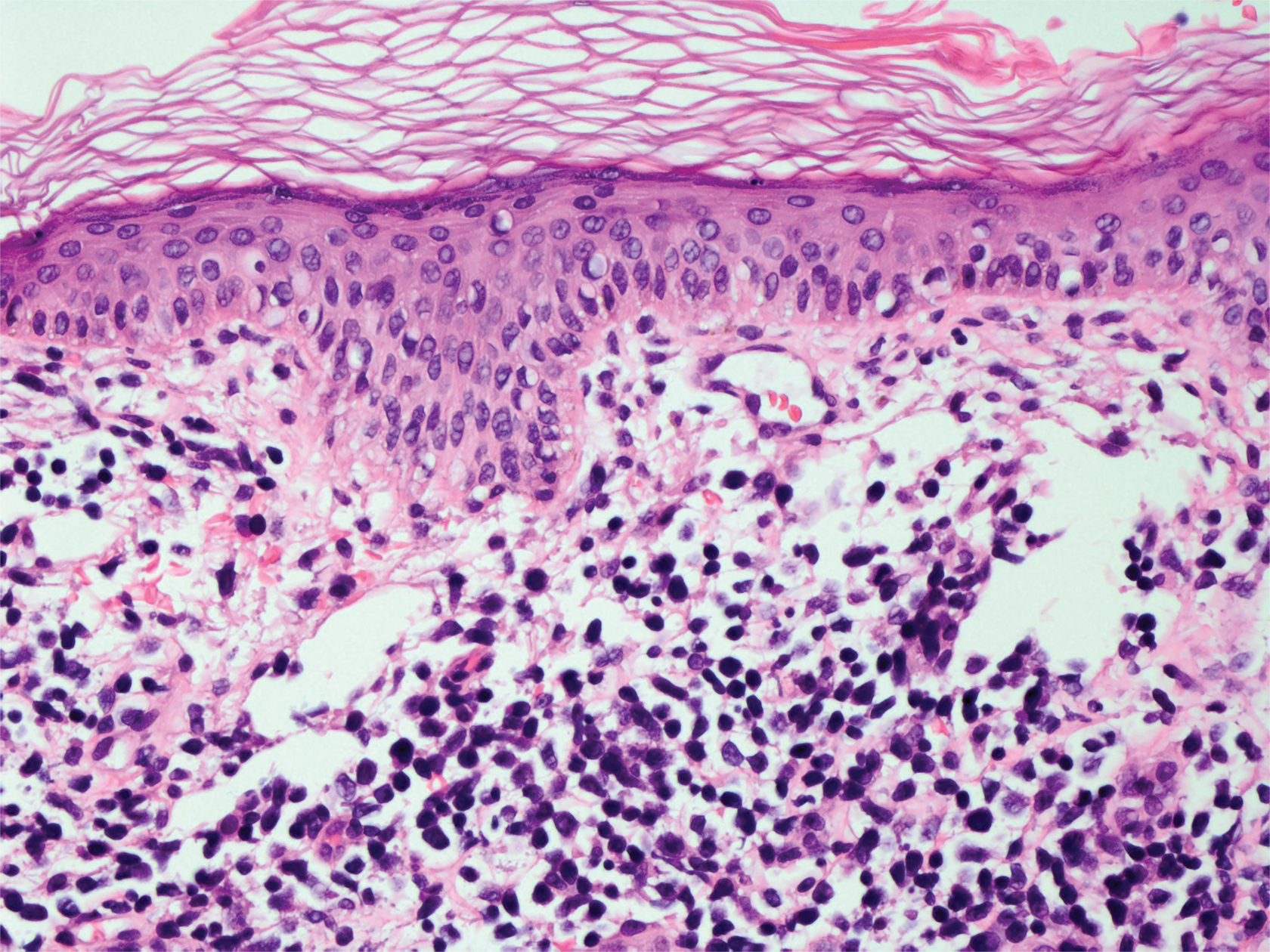

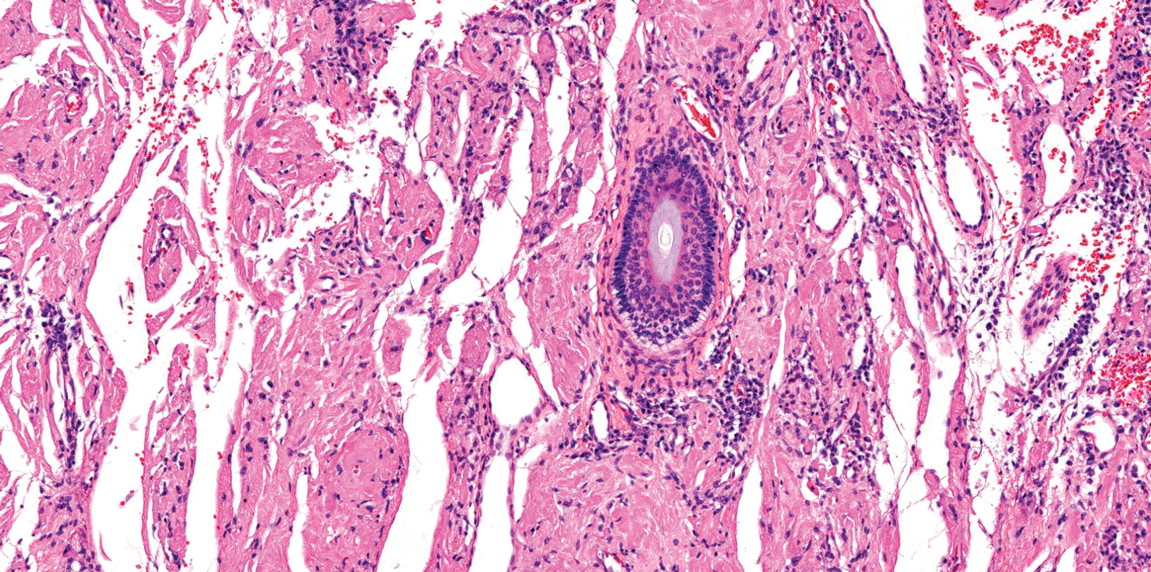

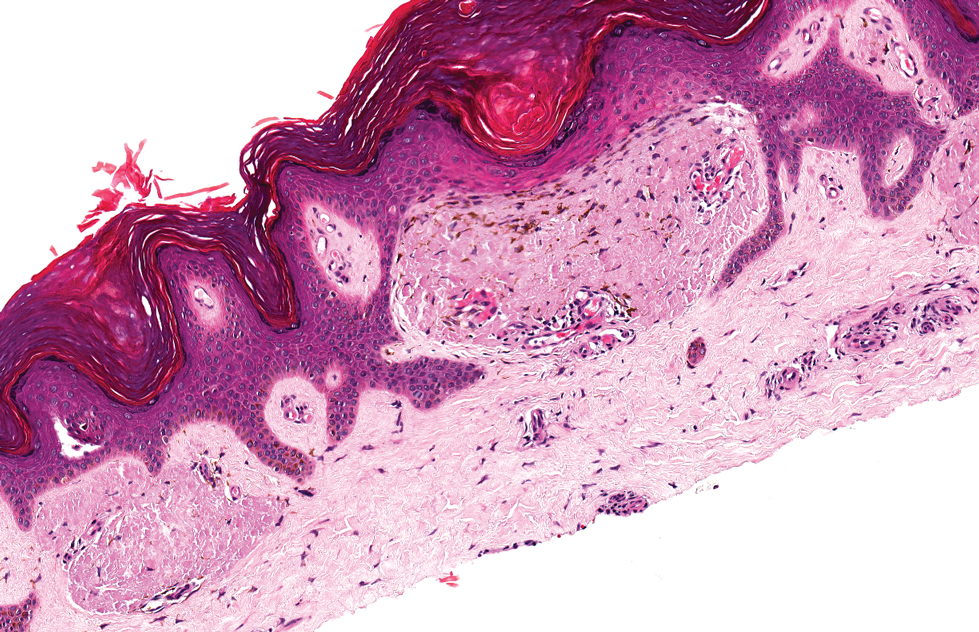

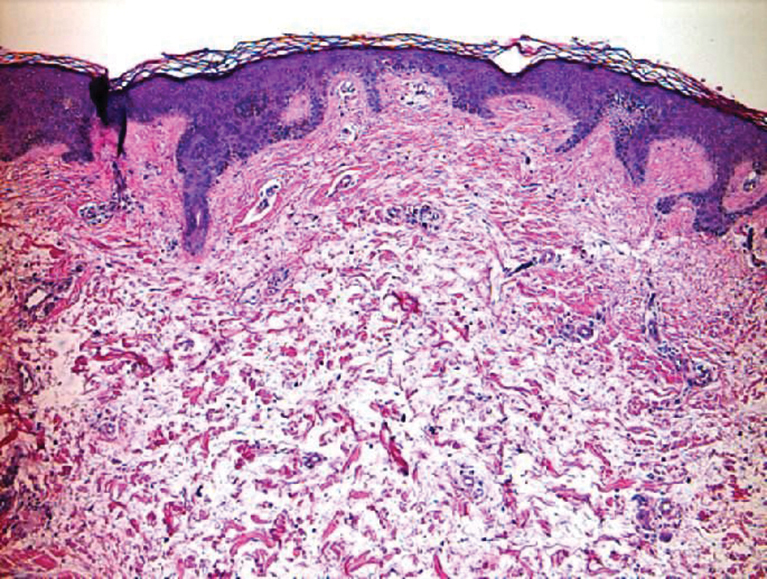

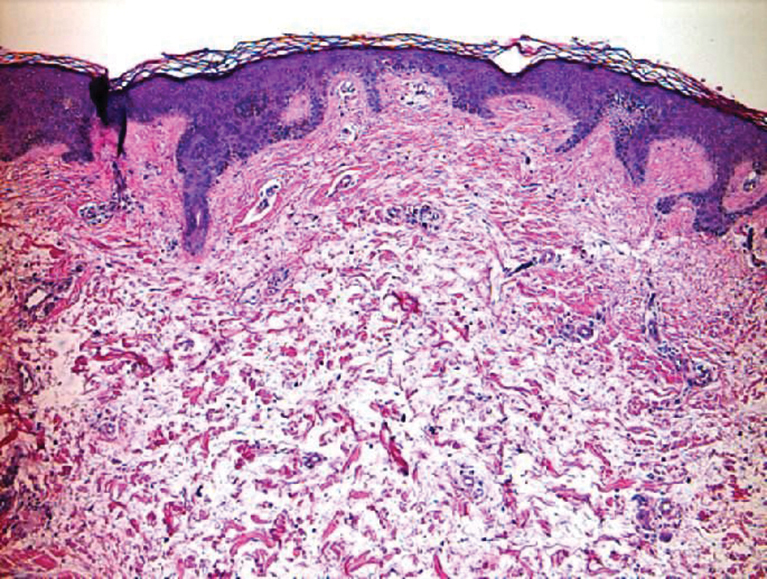

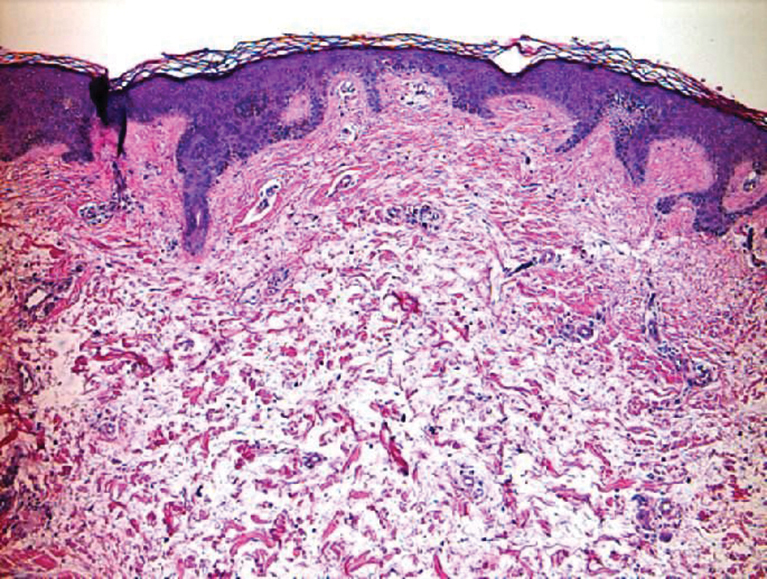

Leprosy is caused by Mycobacterium leprae, a grampositive bacillus. The condition manifests across a spectrum, with the poles being tuberculoid and lepromatous, and borderline variants in between.6-8 Lepromatous leprosy arises in individuals who are unable to mount cellular immunity against M leprae secondary to anergy.6 Lepromatous leprosy often presents with numerous papules and nodules. Aside from cutaneous manifestations, lepromatous leprosy has a predilection for peripheral nerves and specifically Schwann cells. Histologically, biopsy reveals a flat epidermis and a cell-free subepidermal grenz zone. Within the dermis, there is a diffuse histiocytic infiltrate that typically is not centered around nerves (Figure 2).6,7 Mycobacterium leprae can appear scattered throughout or clustered in globi. Mycobacterium leprae stains red with Ziehl-Neelsen or Wade-Fite stains.6,7 Immunohistochemistry reveals a CD4+ helper T cell (TH2) predominance, supported by the increased expression of type 2 reaction cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13.8

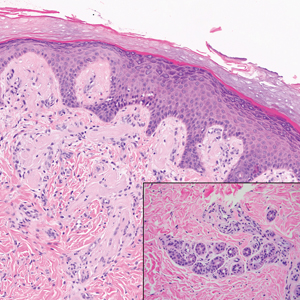

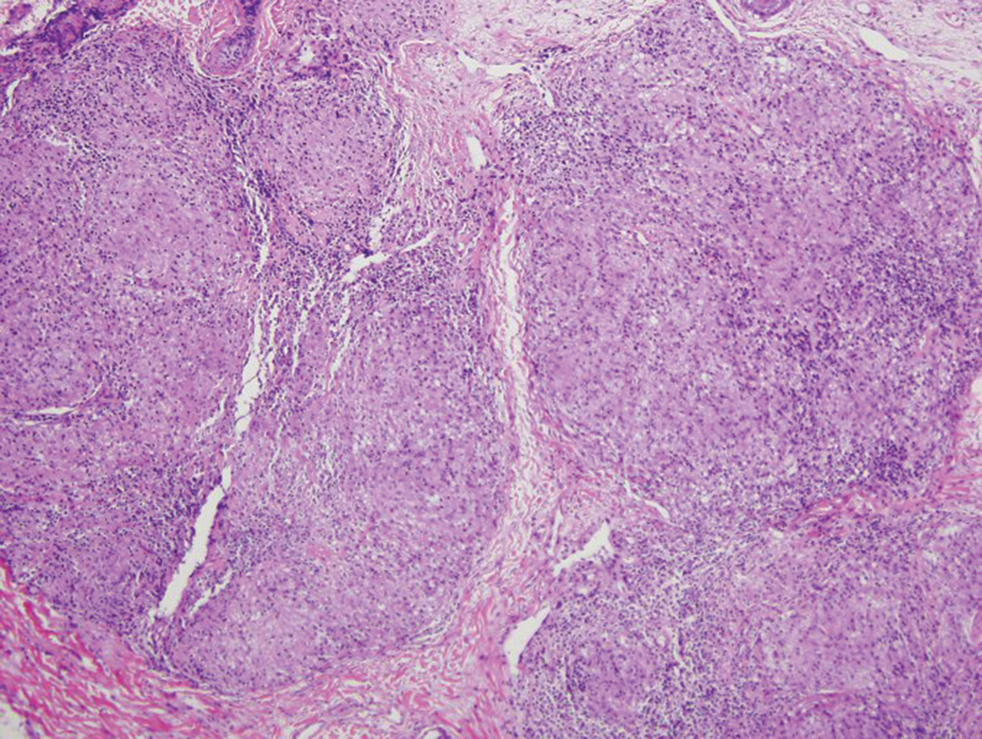

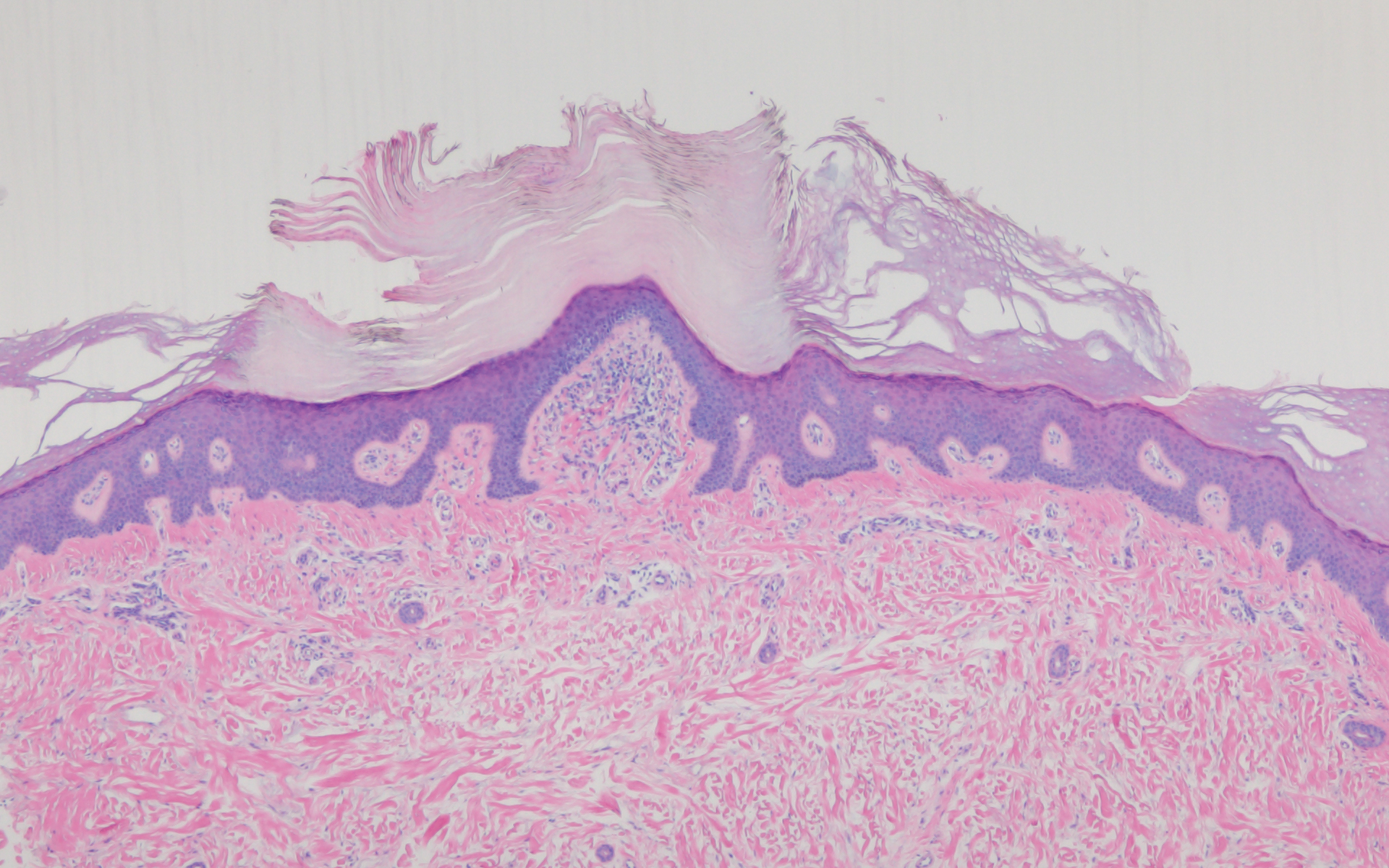

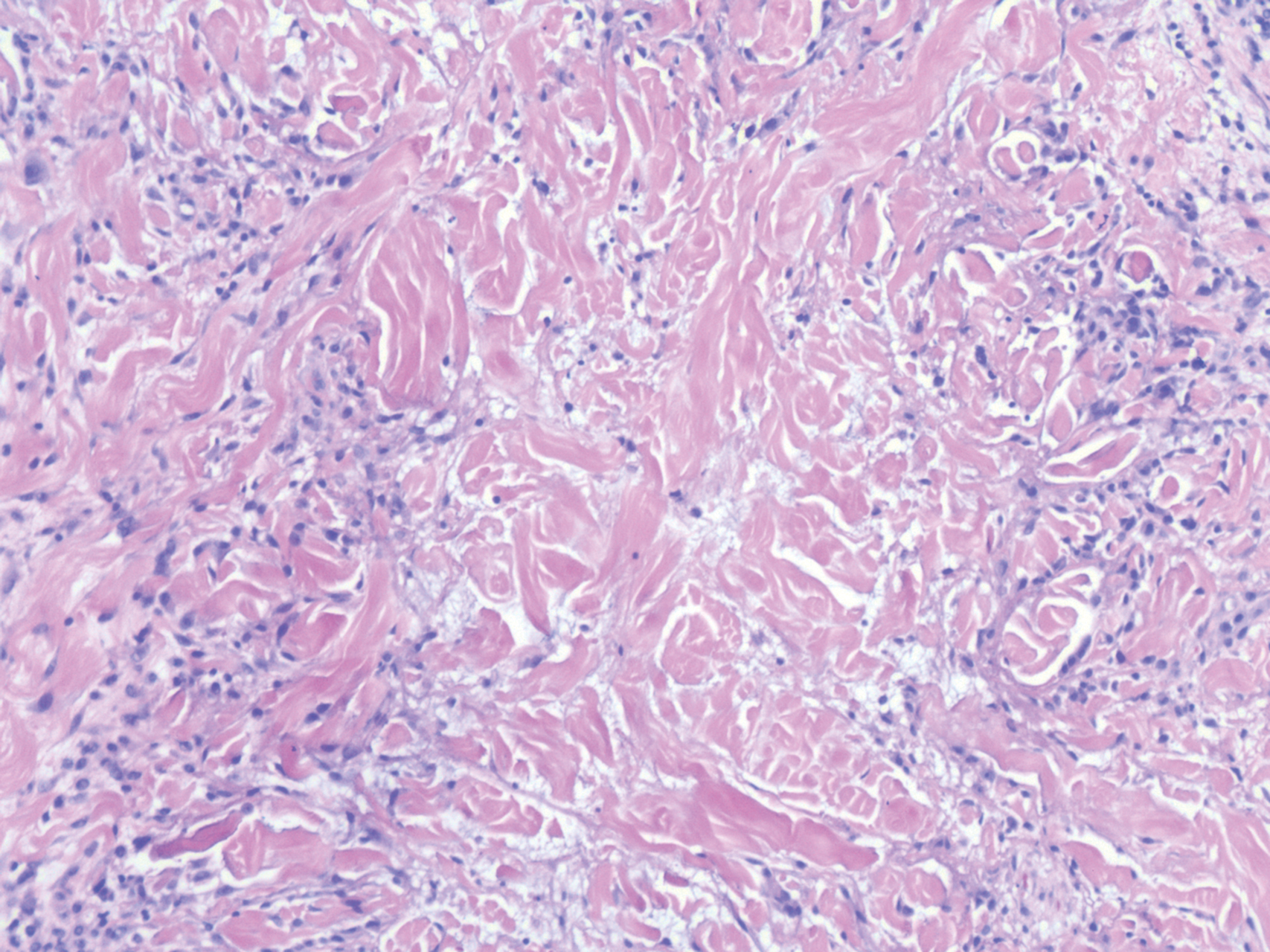

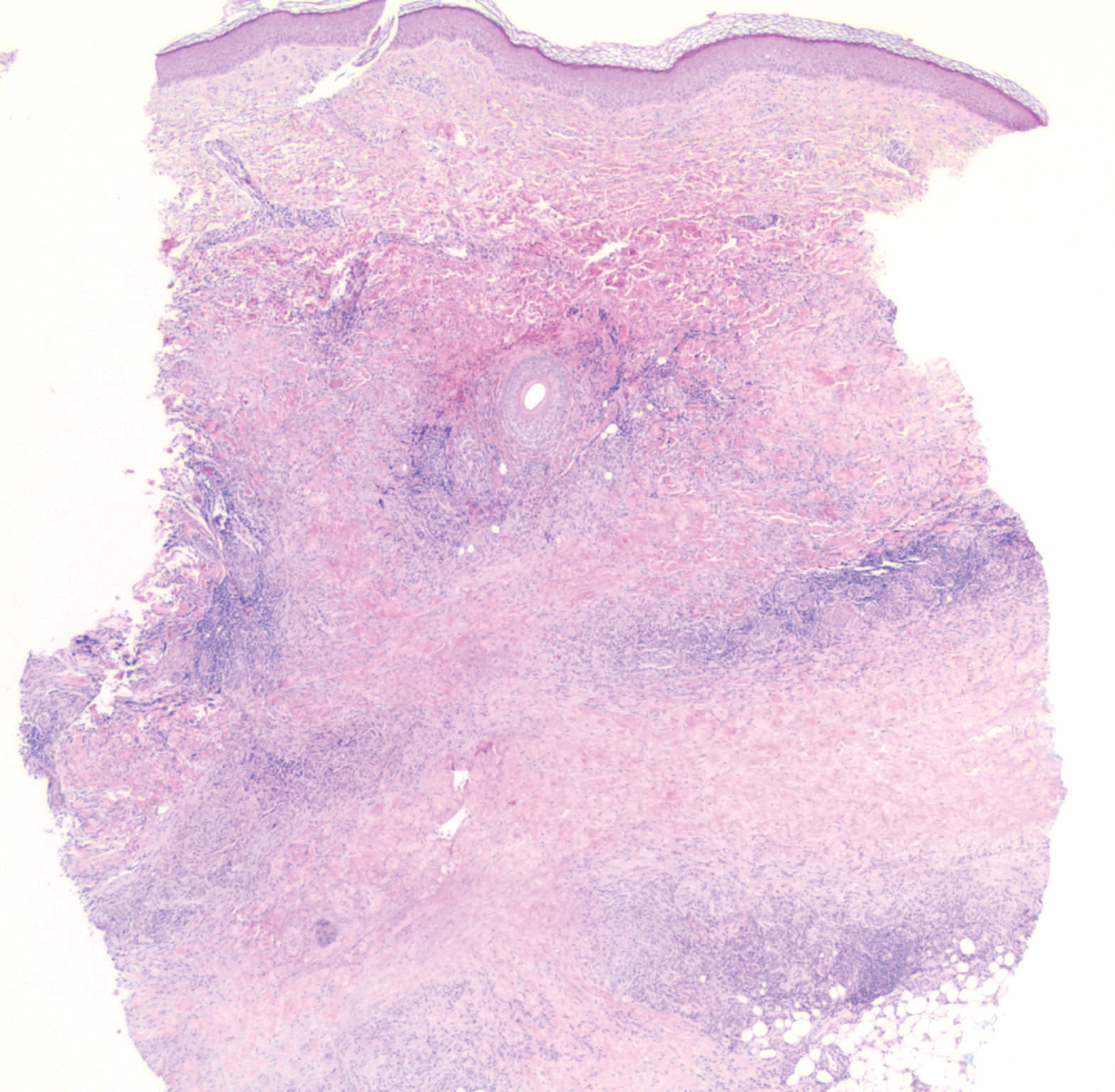

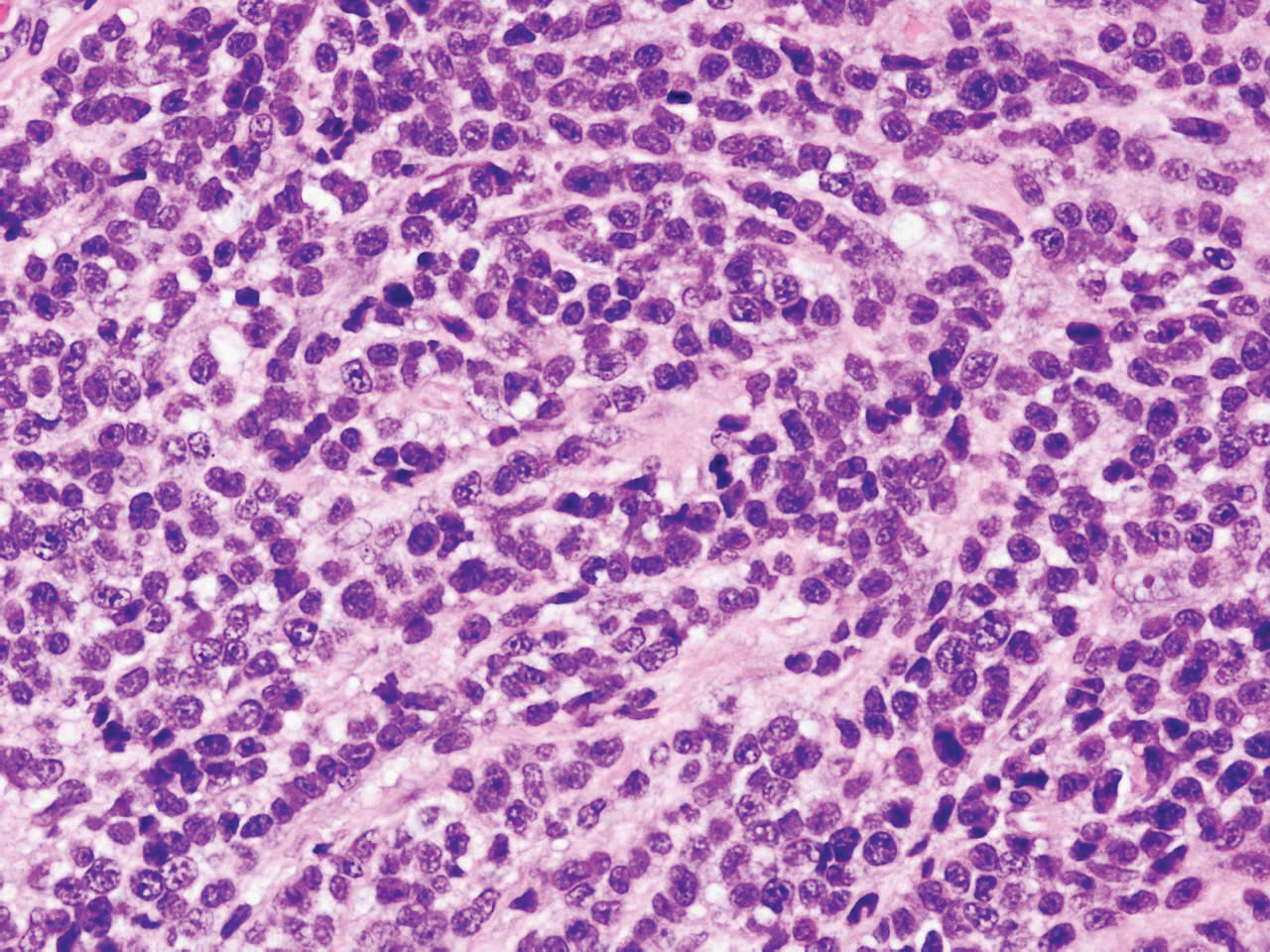

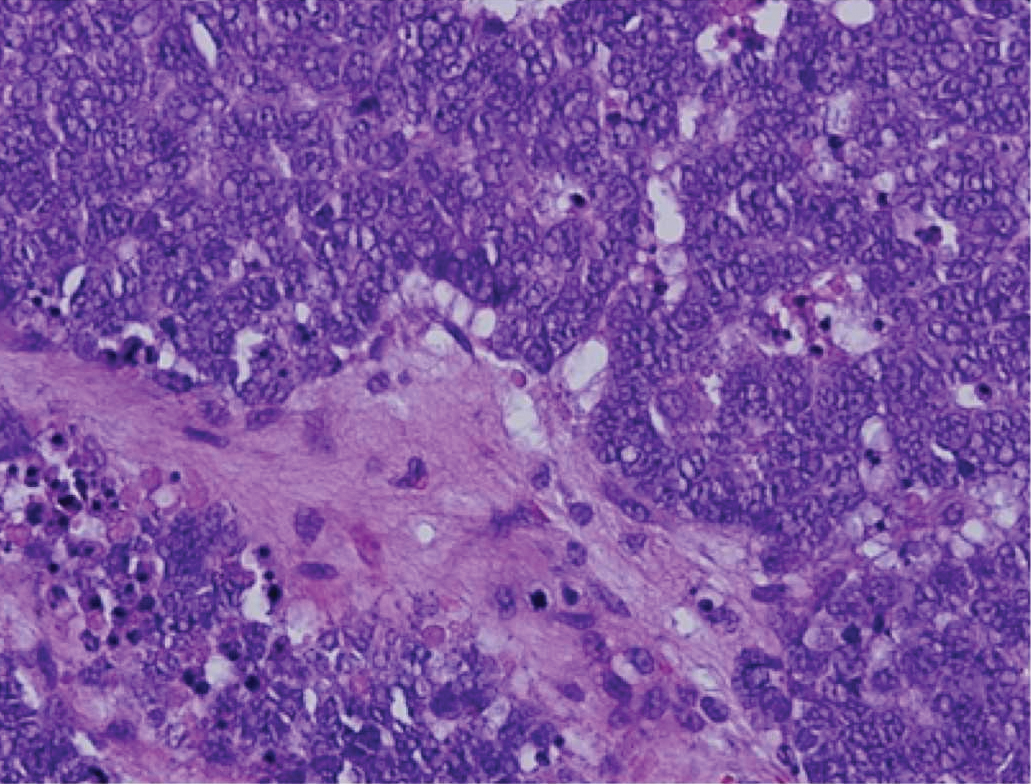

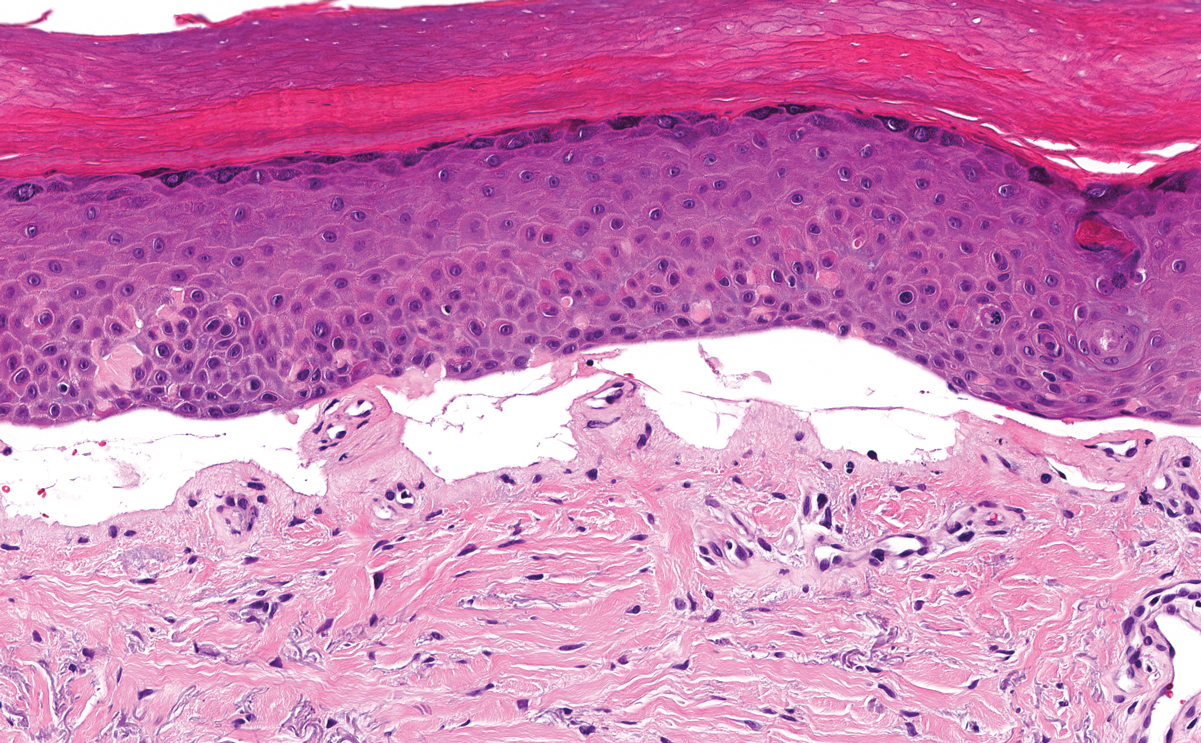

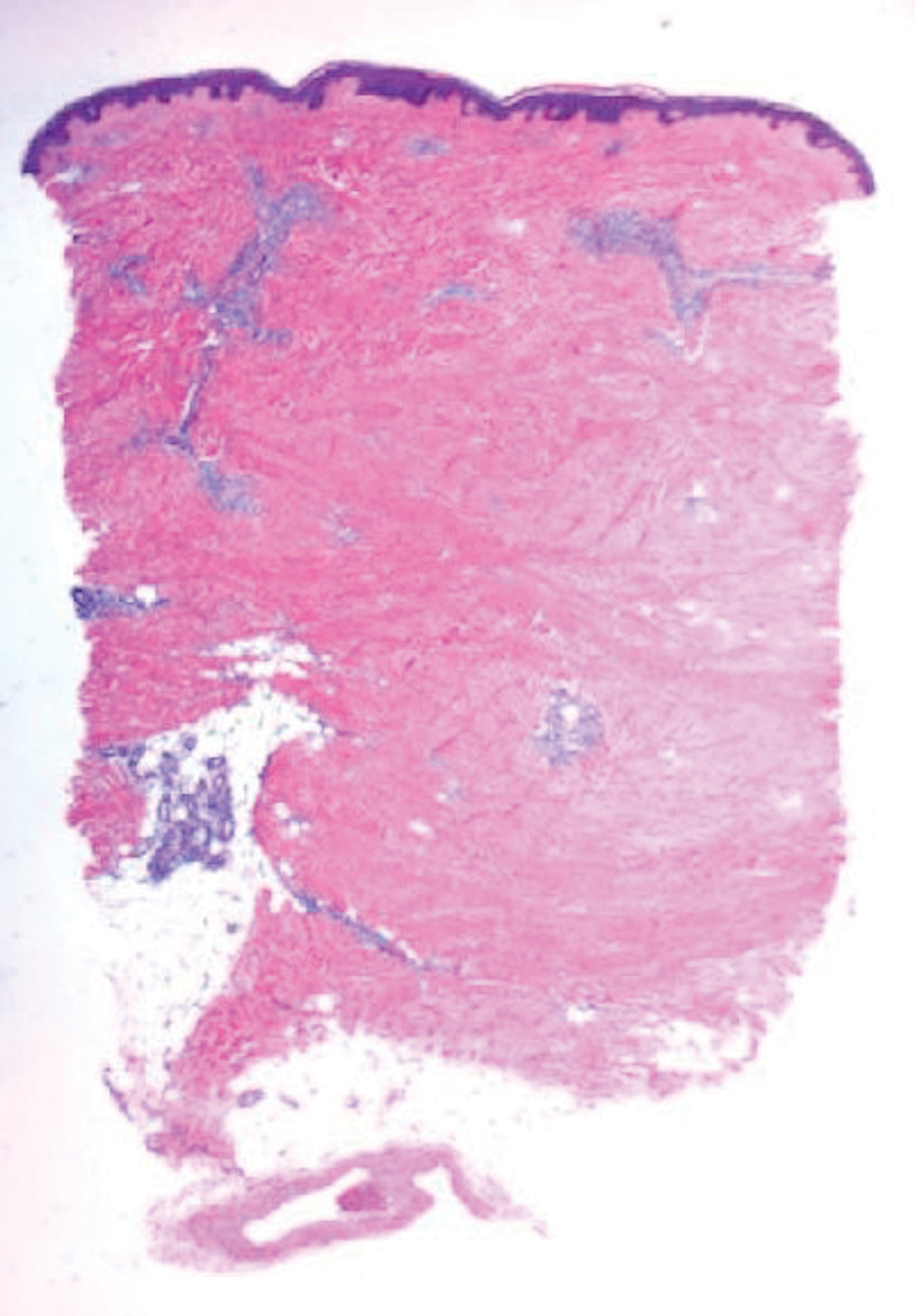

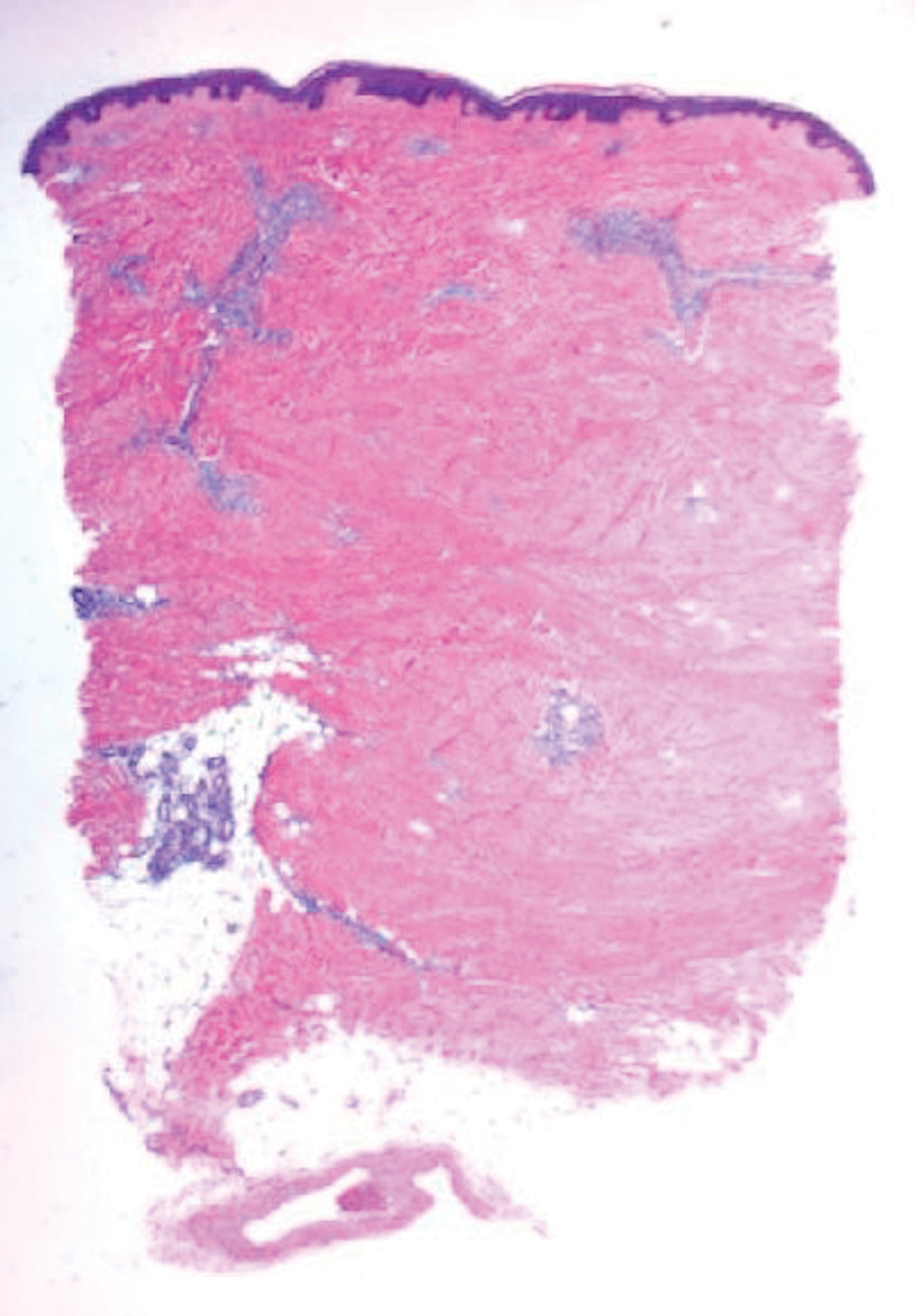

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) embodies 10% to 20% of all primary cutaneous lymphomas; it is more prevalent in older adults (age range, 70–82 years) and women. Clinically, DLBCL presents as either single or multiple rapidly progressing nodules or plaques, usually violaceous or blue-red in color.9,10 The most common area of presentation is on the legs, though it also can surface at other sites.9 On histology, DLBCL has clearly malignant features including frequent mitotic figures, large immunoblasts, and involvement throughout the dermis as well as perivascularly (Figure 3). Spindle-shaped cells and anaplastic features can be present. Immunohistochemically, DLBCL stains strongly positive for CD20 and B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) along with other pan–B-cell markers.9-11 The aggressive leg type of DLBCL stains positively for multiple myeloma oncogene 1 (MUM-1).9,11

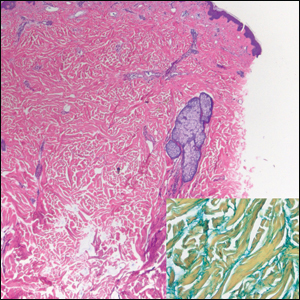

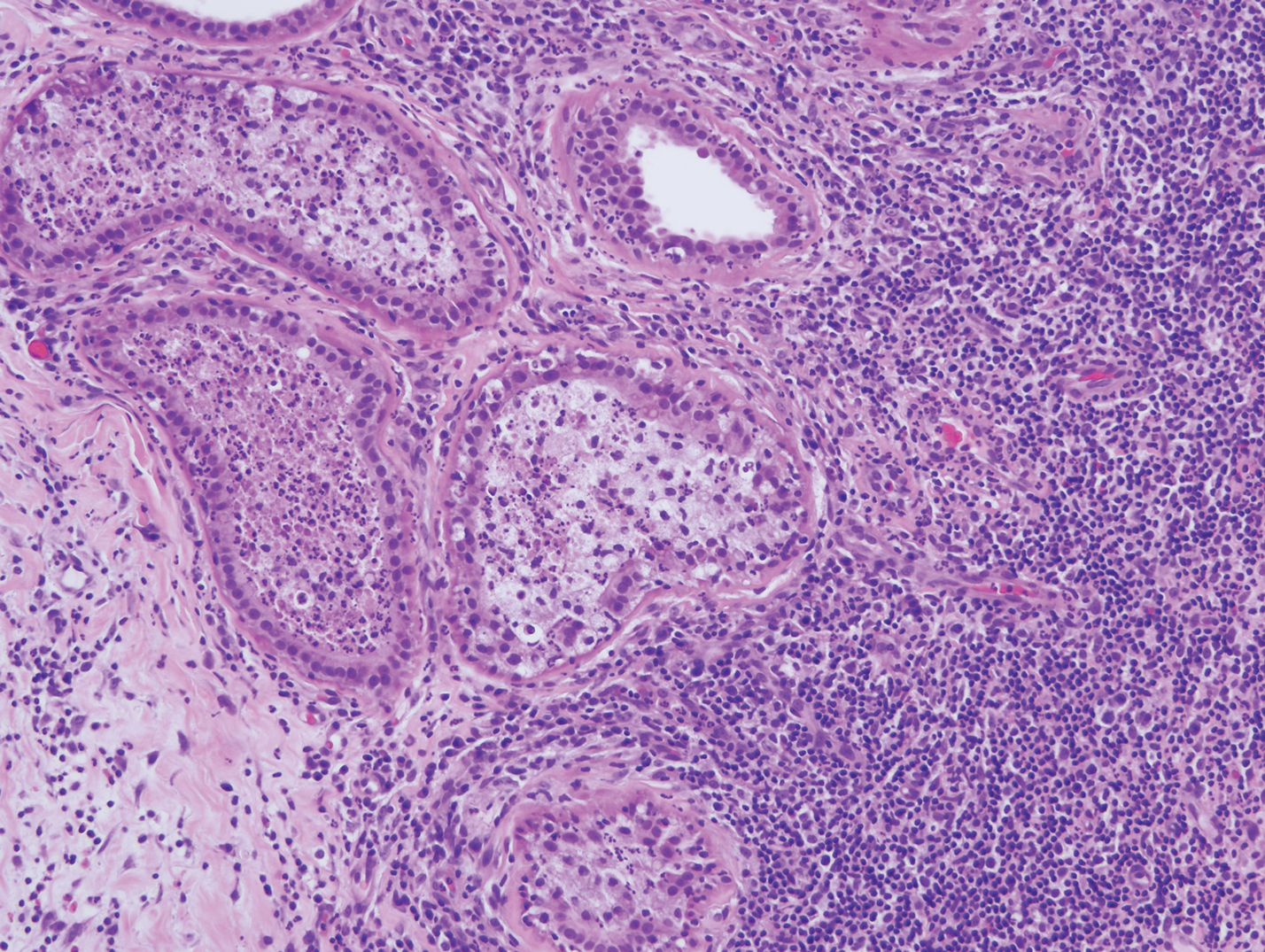

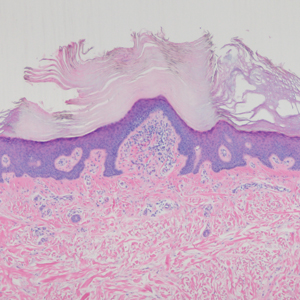

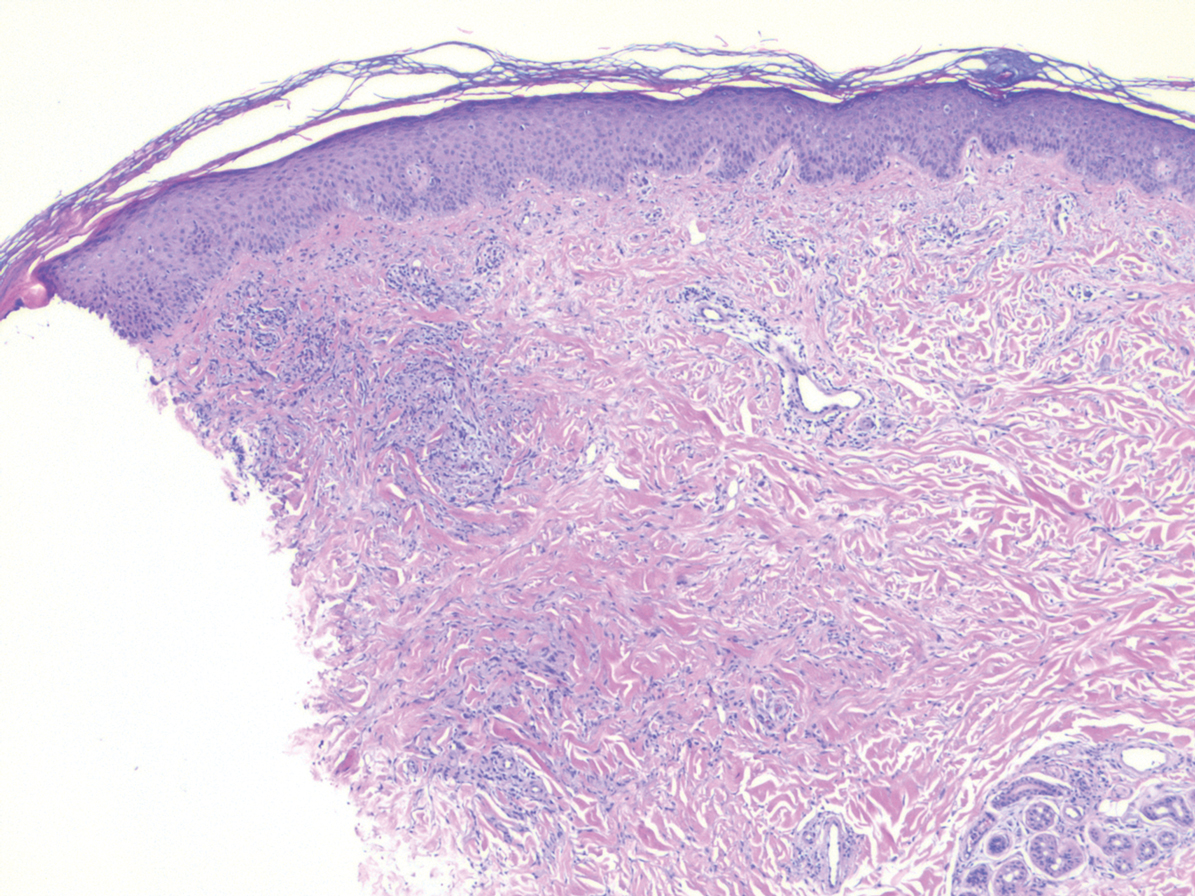

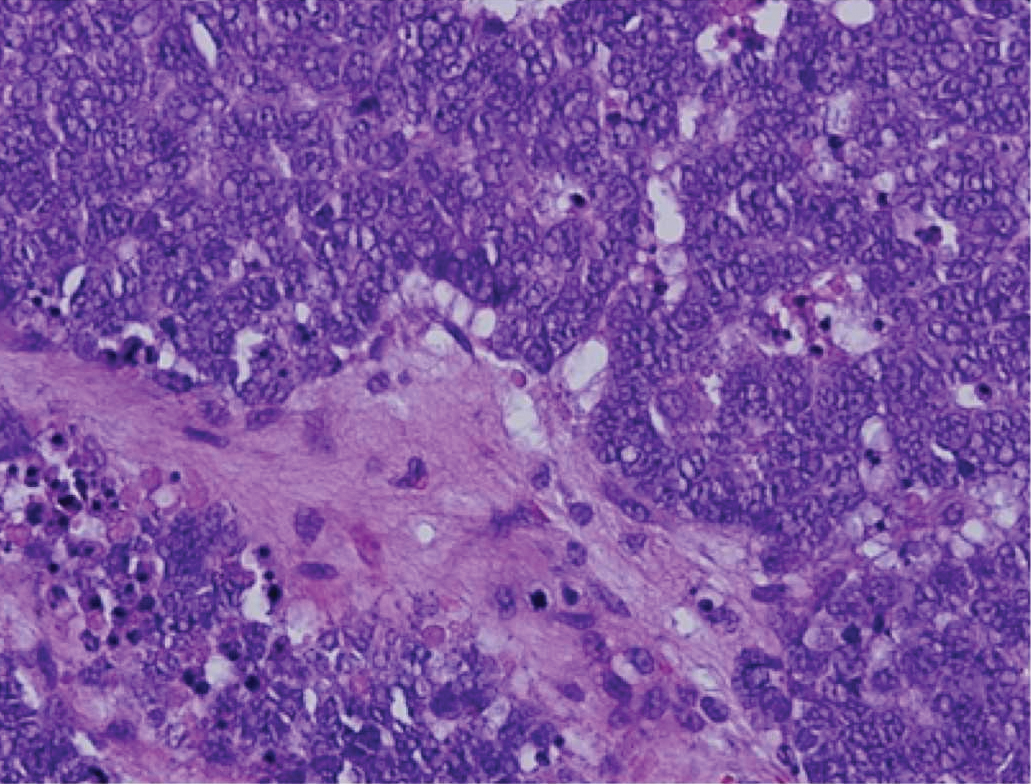

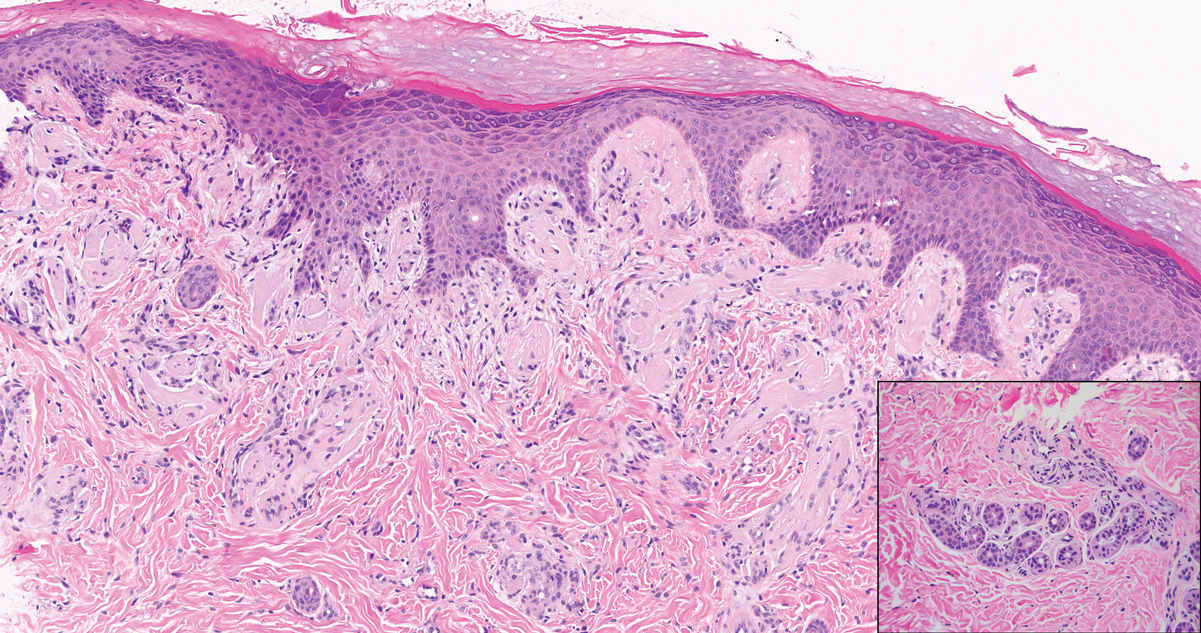

Cutaneous metastatic adenocarcinoma from internal malignancies occurs in approximately 5% of cancer patients with metastatic spread.12 Most of these cutaneous lesions develop in close proximity to the primary tumor such as on the trunk, head, or neck. All cutaneous metastases carry a poor prognosis. Clinical presentation can vary greatly, ranging from painless, firm, or elastic nodules to lesions that mimic inflammatory skin conditions such as erysipelas or scleroderma. The majority of these metastases develop as painless firm nodules that are flesh colored, pink, red-brown, or purple.12,13 The histopathology of metastatic adenocarcinoma demonstrates an infiltrative nodular appearance, though there rarely are well-circumscribed nodules found.13 The lesion originates in the dermis or subcutaneous tissue. It is a glandulartype lesion that may reflect the tissue of the primary tumor (Figure 4).12,14 Immunohistochemical stains likely will remain consistent with those of the primary tumor, which is not always the case.14

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is an aggressive cutaneous malignancy of epithelial and neuroendocrine origin, first described as trabecular carcinoma due to the arrangement of tumor resembling cancellous bone.15,16 Merkel cells are mechanoreceptors found near nerve terminals.17 Approximately 80% of MCCs are associated with Merkel cell polyomavirus, which is a small, double-stranded DNA virus with an icosahedral capsid.17,18 Merkel cell polyomavirus–positive cases of MCC tend to have a better prognosis. In Merkel cell polyomavirus–negative MCC, there is an association with UV damage and increased chromosomal aberrations.18 Merkel cell carcinoma is known for its high rate of recurrence as well as local and distant metastasis. Nodal involvement is the most important prognostic indicator.15 Clinically, MCC is associated with the AEIOU mnemonic (asymptomatic, expanding rapidly, immunosuppression, older than 50 years, UV exposed/fair skin).15-17 Lesions appear as red-blue papules on sun-exposed skin and usually are smaller than 2 cm by their greatest dimension. On histopathology, MCC demonstrates small, round, blue cells arranged in sheets or nests originating in the dermis and occasionally can infiltrate the subcutis and lymphovascular surroundings (Figure 5).16-19 Cells have scant eosinophilic cytoplasm and may have fine granular chromatin. Numerous mitotic figures and apoptotic cells also are present. On immunohistochemistry, these cells will stain positive for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, anticytokeratin (CAM 5.2), CK20, and CD56. Due to their neuroendocrine derivation, they also are commonly synaptophysin, neuron-specific enolase, and chromogranin A positive. Notably, MCC will stain negative for leukocyte common antigen, CD20, CD3, CD34, and thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1).16,17

Primary cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphoma can be difficult to diagnose and requires urgent treatment. Clinicians and dermatopathologists need to work together to establish the diagnosis. There is a high mortality rate associated with PCGDTL, making prompt recognition and timely treatment critical. Acknowledgments—Thank you to our colleagues with the Penn State Health Hematology/Oncology Department (Hershey, Pennsylvania) for comanagement of this patient.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to our colleagues with the Penn State Health Hematology/Oncology Department (Hershey, Pennsylvania) for comanagement of this patient.

- Merrill ED, Agbay R, Miranda RN, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphomas showing gamma-delta (γδ) phenotype and predominantly epidermotropic pattern are clinicopathologically distinct from classic primary cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41:204-215.

- Foppoli M, Ferreri AJ. Gamma‐delta T‐cell lymphomas. Eur J Haematol. 2015;94:206-218.

- Toro JR, Liewehr DJ, Pabby N, et al. Gamma-delta T-cell phenotype is associated with significantly decreased survival in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2003;101:3407-3412.

- Rubio-Gonzalez B, Zain J, Garcia L, et al. Cutaneous gamma-delta T-cell lymphoma successfully treated with brentuximab vedotin. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1388-1390.

- Tong H, Ren Y, Liu H, et al. Clinical characteristics of T-cell lymphoma associated with hemophagocytic syndrome: comparison of T-cell lymphoma with and without hemophagocytic syndrome. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49:81-87.

- Brehmer-Andersson E. Leprosy. Dermatopathology. New York, NY: Springer; 2006:110-113.

- Massone C, Belachew WA, Schettini A. Histopathology of the lepromatous skin biopsy. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:38-45.

- Naafs B, Noto S. Reactions in leprosy. In: Nunzi E, Massone C, eds. Leprosy: A Practical Guide. Milan, Italy: Springer; 2012:219-239.

- Hope CB, Pincus LB. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas. Clin Lab Med. 2017;37:547-574.

- Billero VL, LaSenna CE, Romanelli M, et al. Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma presenting as chronic non-healing ulcer. Int Wound J. 2017;14:830-832.

- Testo N, Olson L, Subramaniyam S, et al. Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with a MYC-IGH rearrangement and gain of BCL2: expanding the spectrum of MYC/BCL2 double hit lymphomas. Am J Dermatopathol. 2016;38:769-774.

- Boyd AS. Pulmonary signet-ring cell adenocarcinoma metastatic to the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:E66-E68.

- Guanziroli E, Coggi A, Venegoni L, et al. Cutaneous metastases of internal malignancies: an experience from a single institution. Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:609-614.

- Fernandez-Flores A, Cassarino DS. Cutaneous metastasis of adenocarcinoma of the ampulla of Vater. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:758-761.

- Trinidad CM, Torres-Cabala CA, Prieto VG, et. Al. Update on eighth edition American Joint Committee on Cancer classification for Merkel Cell carcinoma and histopathological parameters that determine prognosis. J Clin Pathol. 2017;72:337-340.

- Bandino JP, Purvis CG, Shaffer BR, et al. A comparison of the histopathologic growth patterns between non-Merkel cell small round blue cell tumors and Merkel cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:815-818.

- Mauzo SH, Rerrarotto R, Bell D, et al. Molecular characteristics and potential therapeutic targets in Merkel cell carcinoma. J Clin Pathol. 2016;69:382-390.

- Lowe G, Brewer J, Bordeaux J. Epidemiology and genetics. In: Alam M, Bordeaux JS, Yu SS, eds. Merkel Cell Carcinoma. New York, NY: Springer; 2013:26-28.

- North J, McCalmont T. Histopathologic diagnosis. In: Alam M, Bordeaux JS, Yu SS, eds. Merkel Cell Carcinoma. New York, NY: Springer; 2013:66-69.

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous γδ T-cell Lymphoma

Primary cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphoma (PCGDTL) is a distinct entity that can be confused with other types of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas. Often rapidly fatal, PCGDTL has a broad clinical spectrum that may include indolent variants—subcutaneous, epidermotropic, and dermal.1 Primary cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphoma represents less than 1% of all cutaneous T-cell lymphomas.2 Diagnosis and treatment remain challenging. Patients typically present with nodular lesions that progress to ulceration and necrosis. Early lesions can be confused with erythema nodosum, mycosis fungoides, or infection on clinical examination; biopsy establishes the diagnosis. Typical findings include a cytotoxic phenotype, variable epidermotropism, dermal and subcutaneous involvement, and loss of CD4 and often CD8 expression. Testing for Epstein-Barr virus expression yields negative results. The neoplastic lymphocytes in dermal and subcutaneous PCGDTL typically are T-cell intracellular antigen-1 (TIA-1) and granzyme positive.1

Immunohistochemistry failed to reveal CD8, CD56, granzyme, or T-cell intracellular antigen-1 staining of neoplastic cells in our patient but stained diffusely positive with CD3 and CD4. A CD20 stain decorated only a few dermal cells. The patient’s skin lesions continued to enlarge, and the massive lymphadenopathy made breathing difficult. Computed tomography revealed diffuse systemic involvement. An axillary lymph node biopsy revealed sinusoids with complete diffuse effacement of architecture as well as frequent mitotic figures and karyorrhectic debris (Figure 1A). Negative staining for T-cell receptor beta-F1 of the axillary lymph node biopsy and clonal rearrangement of the T-cell receptor gamma chain supported the diagnosis of PCGDTL. Nuclear staining for Epstein-Barr virus–encoded RNA was negative. Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 antibodies and polymerase chain reaction also were negative. Flow cytometry demonstrated an atypical population of CD3+, CD4+, and CD7− γδ T lymphocytes, further supporting the diagnosis of lymphoma.

The median life expectancy for patients with dermal or subcutaneous PCGDTL is 10 to 15 months after diagnosis.3 The 5-year life expectancy for PCGDTL is approximately 11%.2 Limited treatment options contribute to the poor outcome. Chemotherapy regimens such as CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisolone) and EPOCH (etoposide phosphate, prednisone, vincristine sulfate, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride) have yielded inconsistent results. Stem cell transplant has been tried in progressive disease and also has yielded mixed results.2 Brentuximab is indicated for individuals whose tumors express CD30.4 Associated hemophagic lymphohistiocytosis portends a poor prognosis.5

Despite treatment with etoposide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and high-dose oral steroids, our patient developed progressive difficulty breathing, stridor, kidney injury, and anemia. Our patient died less than 1 month after diagnosis—after only 1 round of chemotherapy—secondary to progressive disease and an uncontrollable gastrointestinal tract bleed. The leonine facies (Figure 1B) encountered in our patient can raise a differential diagnosis that includes infectious as well as neoplastic etiologies; however, most infectious etiologies associated with leonine facies manifest in a chronic fashion rather than with a sudden eruption, as noted in our patient.

Leprosy is caused by Mycobacterium leprae, a grampositive bacillus. The condition manifests across a spectrum, with the poles being tuberculoid and lepromatous, and borderline variants in between.6-8 Lepromatous leprosy arises in individuals who are unable to mount cellular immunity against M leprae secondary to anergy.6 Lepromatous leprosy often presents with numerous papules and nodules. Aside from cutaneous manifestations, lepromatous leprosy has a predilection for peripheral nerves and specifically Schwann cells. Histologically, biopsy reveals a flat epidermis and a cell-free subepidermal grenz zone. Within the dermis, there is a diffuse histiocytic infiltrate that typically is not centered around nerves (Figure 2).6,7 Mycobacterium leprae can appear scattered throughout or clustered in globi. Mycobacterium leprae stains red with Ziehl-Neelsen or Wade-Fite stains.6,7 Immunohistochemistry reveals a CD4+ helper T cell (TH2) predominance, supported by the increased expression of type 2 reaction cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13.8

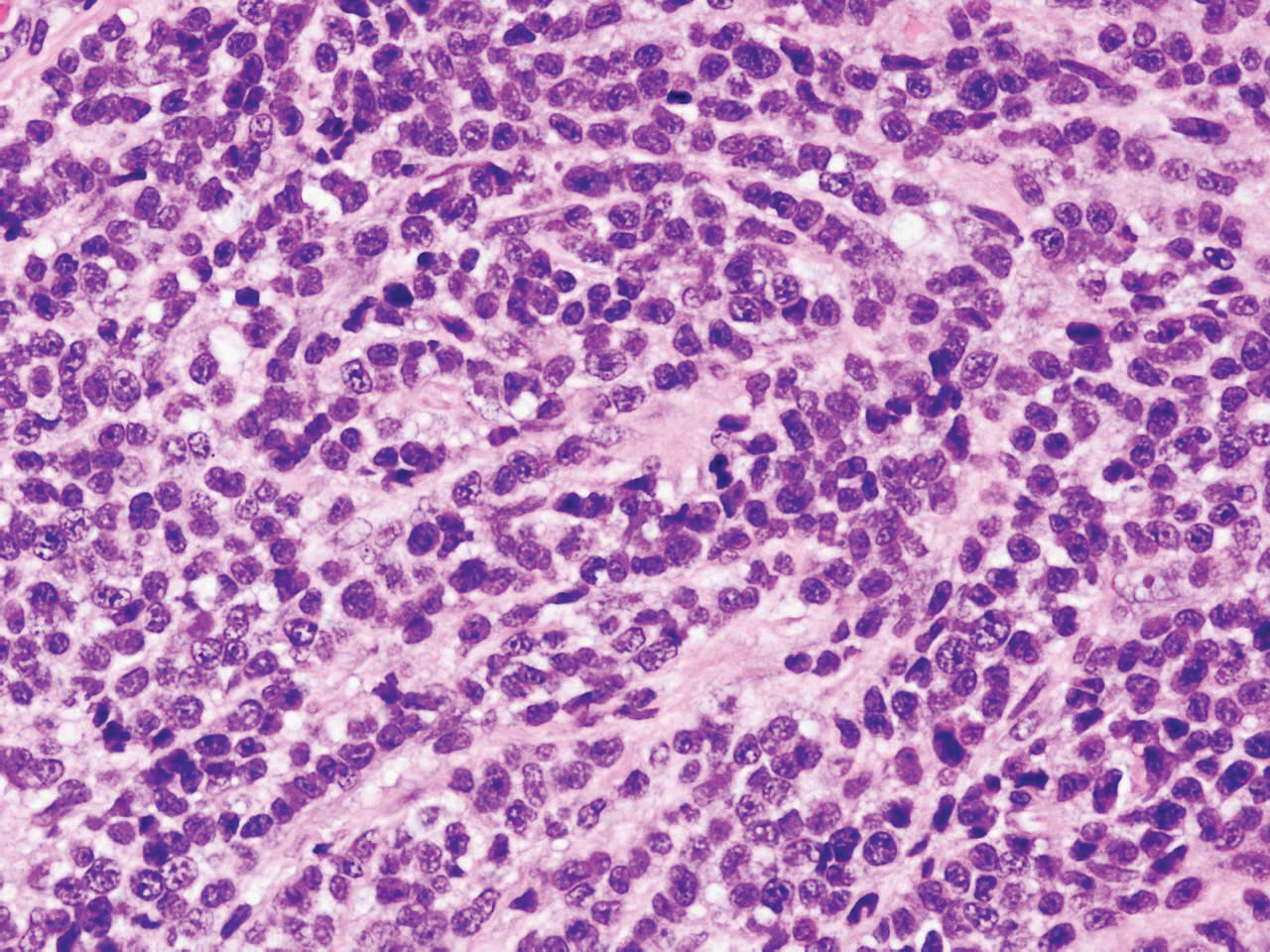

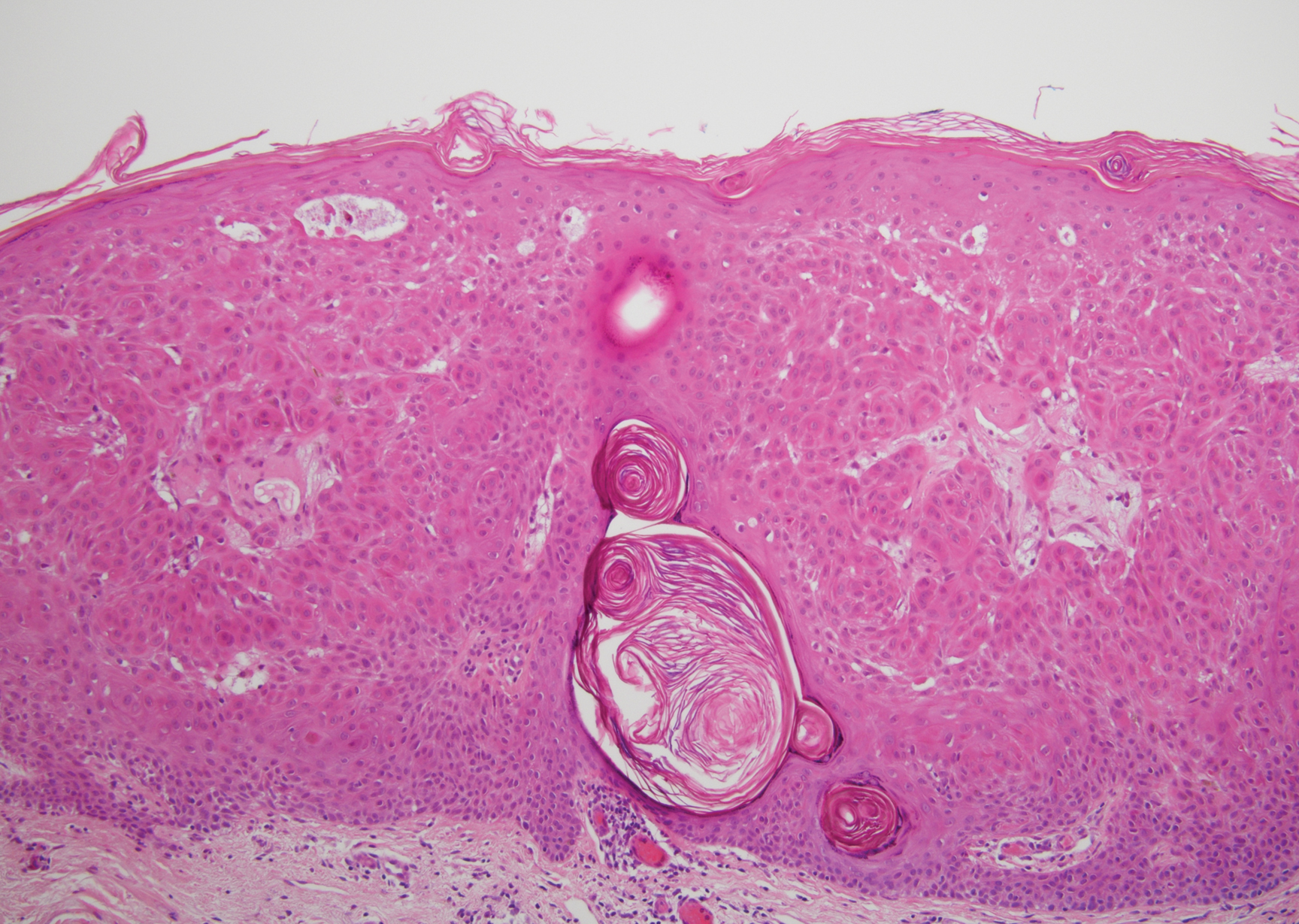

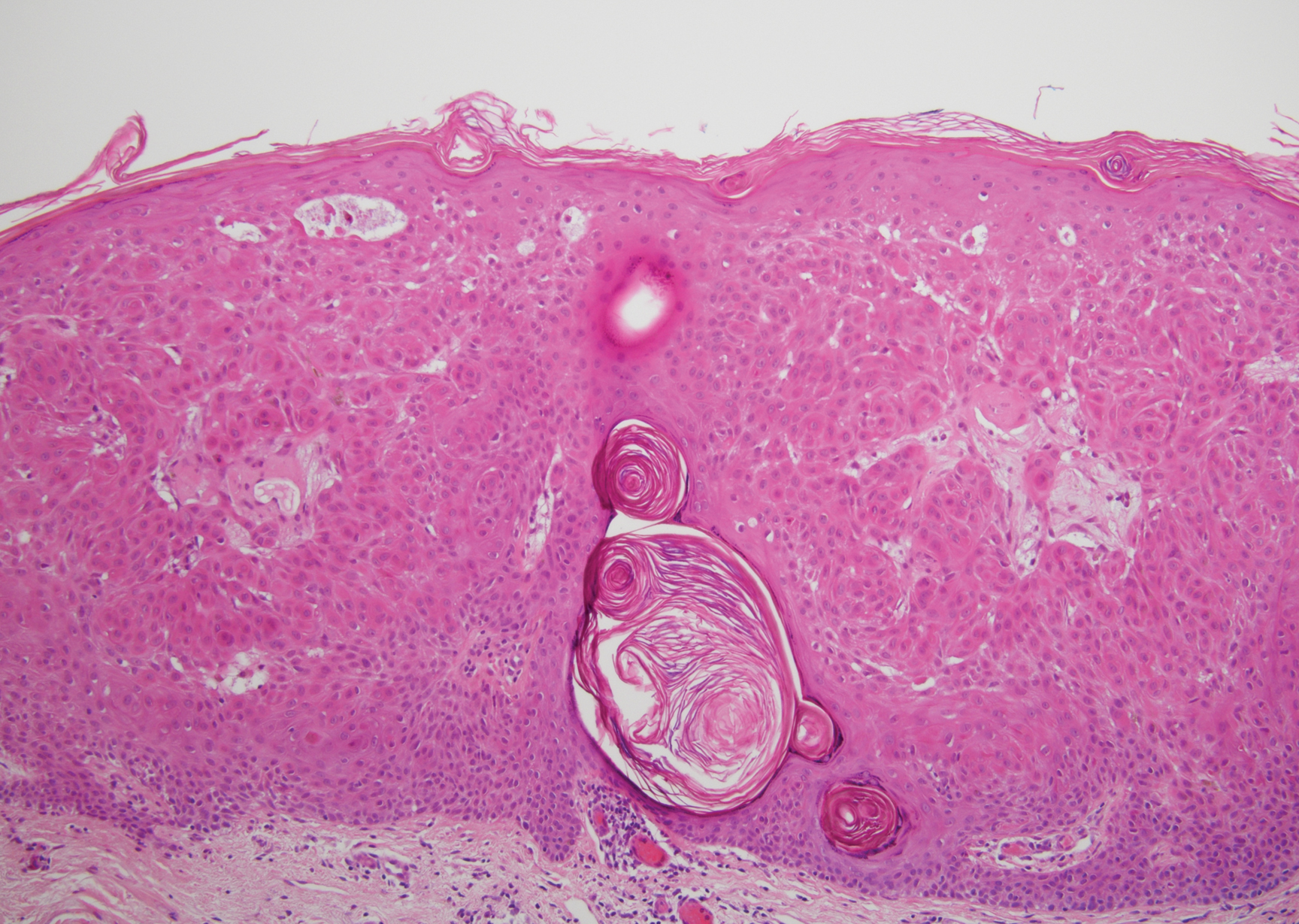

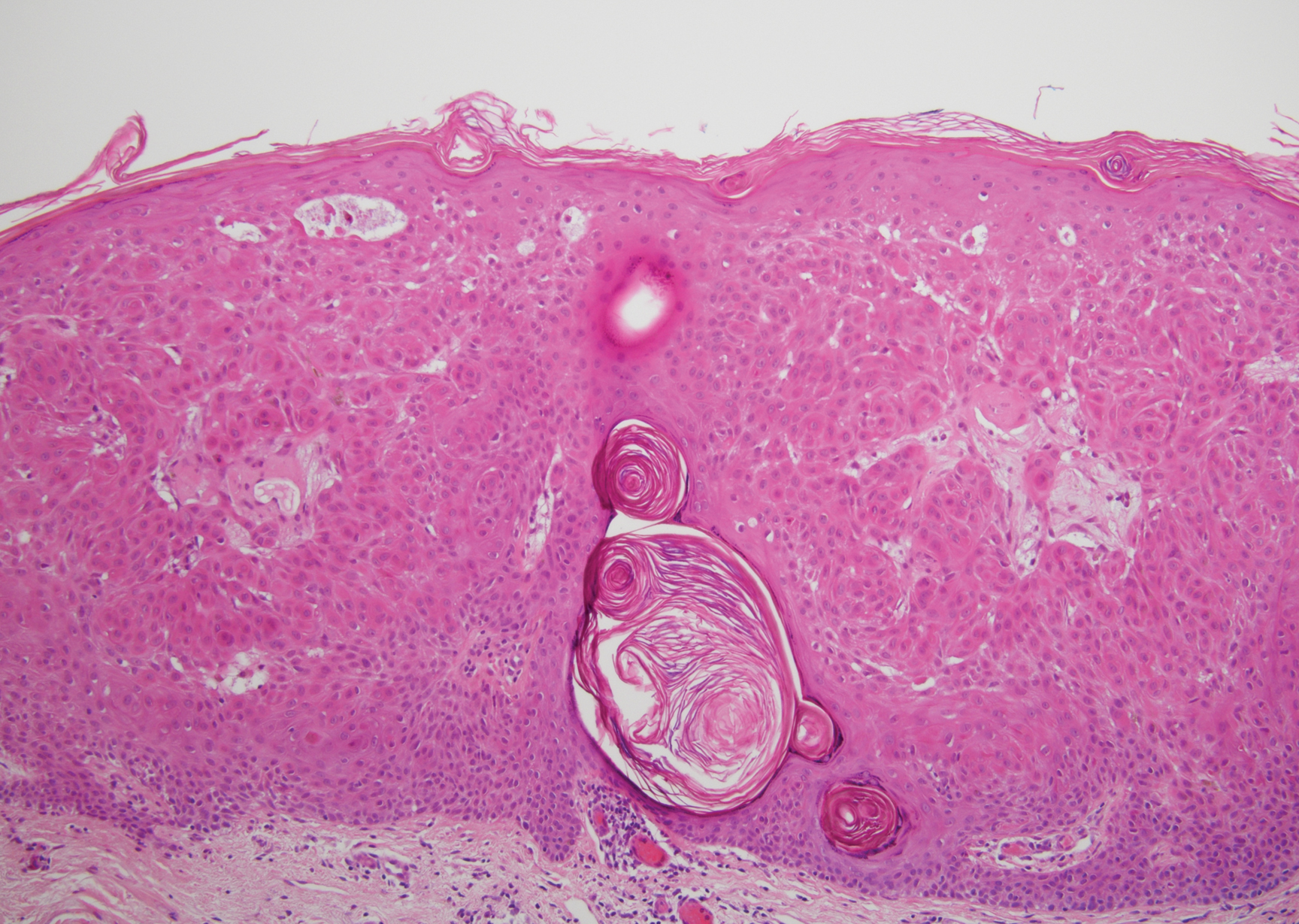

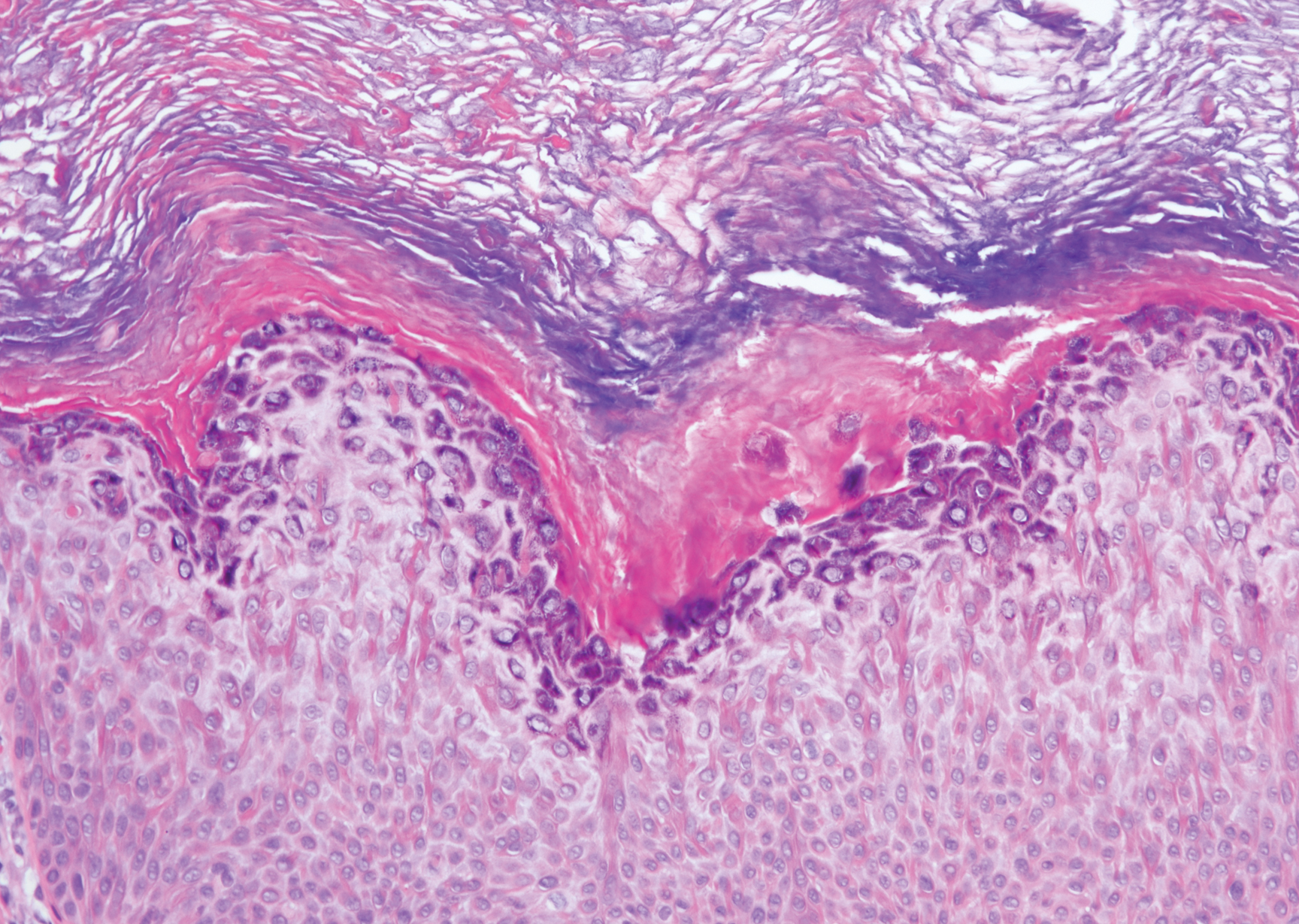

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) embodies 10% to 20% of all primary cutaneous lymphomas; it is more prevalent in older adults (age range, 70–82 years) and women. Clinically, DLBCL presents as either single or multiple rapidly progressing nodules or plaques, usually violaceous or blue-red in color.9,10 The most common area of presentation is on the legs, though it also can surface at other sites.9 On histology, DLBCL has clearly malignant features including frequent mitotic figures, large immunoblasts, and involvement throughout the dermis as well as perivascularly (Figure 3). Spindle-shaped cells and anaplastic features can be present. Immunohistochemically, DLBCL stains strongly positive for CD20 and B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) along with other pan–B-cell markers.9-11 The aggressive leg type of DLBCL stains positively for multiple myeloma oncogene 1 (MUM-1).9,11

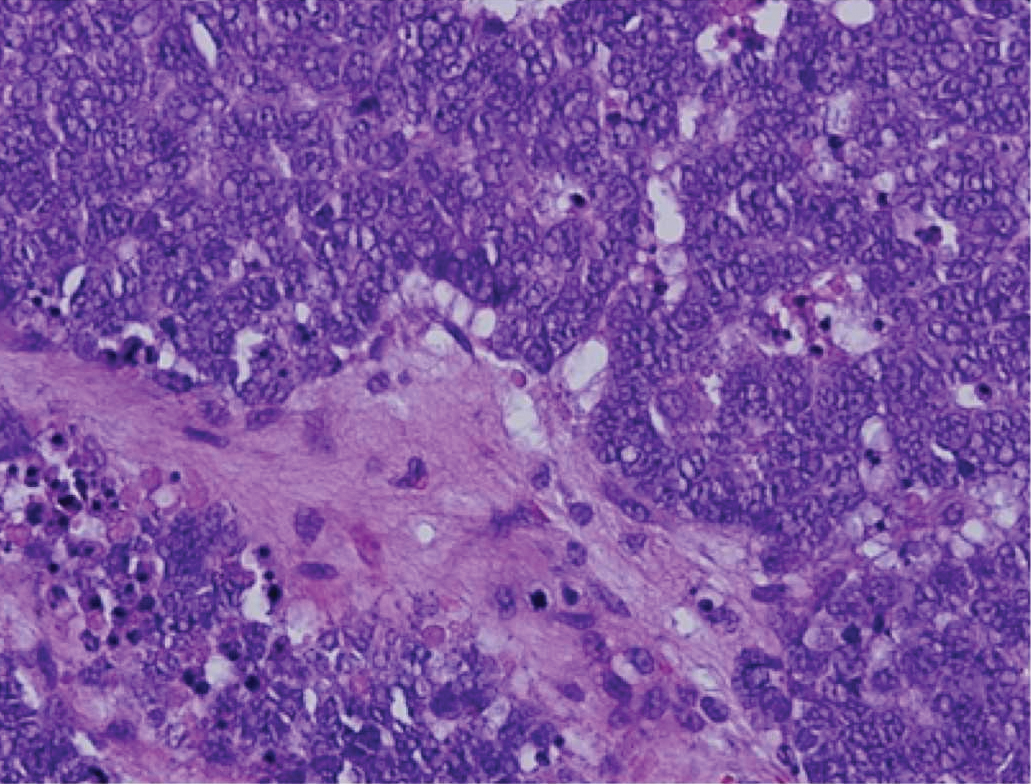

Cutaneous metastatic adenocarcinoma from internal malignancies occurs in approximately 5% of cancer patients with metastatic spread.12 Most of these cutaneous lesions develop in close proximity to the primary tumor such as on the trunk, head, or neck. All cutaneous metastases carry a poor prognosis. Clinical presentation can vary greatly, ranging from painless, firm, or elastic nodules to lesions that mimic inflammatory skin conditions such as erysipelas or scleroderma. The majority of these metastases develop as painless firm nodules that are flesh colored, pink, red-brown, or purple.12,13 The histopathology of metastatic adenocarcinoma demonstrates an infiltrative nodular appearance, though there rarely are well-circumscribed nodules found.13 The lesion originates in the dermis or subcutaneous tissue. It is a glandulartype lesion that may reflect the tissue of the primary tumor (Figure 4).12,14 Immunohistochemical stains likely will remain consistent with those of the primary tumor, which is not always the case.14

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is an aggressive cutaneous malignancy of epithelial and neuroendocrine origin, first described as trabecular carcinoma due to the arrangement of tumor resembling cancellous bone.15,16 Merkel cells are mechanoreceptors found near nerve terminals.17 Approximately 80% of MCCs are associated with Merkel cell polyomavirus, which is a small, double-stranded DNA virus with an icosahedral capsid.17,18 Merkel cell polyomavirus–positive cases of MCC tend to have a better prognosis. In Merkel cell polyomavirus–negative MCC, there is an association with UV damage and increased chromosomal aberrations.18 Merkel cell carcinoma is known for its high rate of recurrence as well as local and distant metastasis. Nodal involvement is the most important prognostic indicator.15 Clinically, MCC is associated with the AEIOU mnemonic (asymptomatic, expanding rapidly, immunosuppression, older than 50 years, UV exposed/fair skin).15-17 Lesions appear as red-blue papules on sun-exposed skin and usually are smaller than 2 cm by their greatest dimension. On histopathology, MCC demonstrates small, round, blue cells arranged in sheets or nests originating in the dermis and occasionally can infiltrate the subcutis and lymphovascular surroundings (Figure 5).16-19 Cells have scant eosinophilic cytoplasm and may have fine granular chromatin. Numerous mitotic figures and apoptotic cells also are present. On immunohistochemistry, these cells will stain positive for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, anticytokeratin (CAM 5.2), CK20, and CD56. Due to their neuroendocrine derivation, they also are commonly synaptophysin, neuron-specific enolase, and chromogranin A positive. Notably, MCC will stain negative for leukocyte common antigen, CD20, CD3, CD34, and thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1).16,17

Primary cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphoma can be difficult to diagnose and requires urgent treatment. Clinicians and dermatopathologists need to work together to establish the diagnosis. There is a high mortality rate associated with PCGDTL, making prompt recognition and timely treatment critical. Acknowledgments—Thank you to our colleagues with the Penn State Health Hematology/Oncology Department (Hershey, Pennsylvania) for comanagement of this patient.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to our colleagues with the Penn State Health Hematology/Oncology Department (Hershey, Pennsylvania) for comanagement of this patient.

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous γδ T-cell Lymphoma

Primary cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphoma (PCGDTL) is a distinct entity that can be confused with other types of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas. Often rapidly fatal, PCGDTL has a broad clinical spectrum that may include indolent variants—subcutaneous, epidermotropic, and dermal.1 Primary cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphoma represents less than 1% of all cutaneous T-cell lymphomas.2 Diagnosis and treatment remain challenging. Patients typically present with nodular lesions that progress to ulceration and necrosis. Early lesions can be confused with erythema nodosum, mycosis fungoides, or infection on clinical examination; biopsy establishes the diagnosis. Typical findings include a cytotoxic phenotype, variable epidermotropism, dermal and subcutaneous involvement, and loss of CD4 and often CD8 expression. Testing for Epstein-Barr virus expression yields negative results. The neoplastic lymphocytes in dermal and subcutaneous PCGDTL typically are T-cell intracellular antigen-1 (TIA-1) and granzyme positive.1

Immunohistochemistry failed to reveal CD8, CD56, granzyme, or T-cell intracellular antigen-1 staining of neoplastic cells in our patient but stained diffusely positive with CD3 and CD4. A CD20 stain decorated only a few dermal cells. The patient’s skin lesions continued to enlarge, and the massive lymphadenopathy made breathing difficult. Computed tomography revealed diffuse systemic involvement. An axillary lymph node biopsy revealed sinusoids with complete diffuse effacement of architecture as well as frequent mitotic figures and karyorrhectic debris (Figure 1A). Negative staining for T-cell receptor beta-F1 of the axillary lymph node biopsy and clonal rearrangement of the T-cell receptor gamma chain supported the diagnosis of PCGDTL. Nuclear staining for Epstein-Barr virus–encoded RNA was negative. Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 antibodies and polymerase chain reaction also were negative. Flow cytometry demonstrated an atypical population of CD3+, CD4+, and CD7− γδ T lymphocytes, further supporting the diagnosis of lymphoma.

The median life expectancy for patients with dermal or subcutaneous PCGDTL is 10 to 15 months after diagnosis.3 The 5-year life expectancy for PCGDTL is approximately 11%.2 Limited treatment options contribute to the poor outcome. Chemotherapy regimens such as CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisolone) and EPOCH (etoposide phosphate, prednisone, vincristine sulfate, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride) have yielded inconsistent results. Stem cell transplant has been tried in progressive disease and also has yielded mixed results.2 Brentuximab is indicated for individuals whose tumors express CD30.4 Associated hemophagic lymphohistiocytosis portends a poor prognosis.5

Despite treatment with etoposide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and high-dose oral steroids, our patient developed progressive difficulty breathing, stridor, kidney injury, and anemia. Our patient died less than 1 month after diagnosis—after only 1 round of chemotherapy—secondary to progressive disease and an uncontrollable gastrointestinal tract bleed. The leonine facies (Figure 1B) encountered in our patient can raise a differential diagnosis that includes infectious as well as neoplastic etiologies; however, most infectious etiologies associated with leonine facies manifest in a chronic fashion rather than with a sudden eruption, as noted in our patient.

Leprosy is caused by Mycobacterium leprae, a grampositive bacillus. The condition manifests across a spectrum, with the poles being tuberculoid and lepromatous, and borderline variants in between.6-8 Lepromatous leprosy arises in individuals who are unable to mount cellular immunity against M leprae secondary to anergy.6 Lepromatous leprosy often presents with numerous papules and nodules. Aside from cutaneous manifestations, lepromatous leprosy has a predilection for peripheral nerves and specifically Schwann cells. Histologically, biopsy reveals a flat epidermis and a cell-free subepidermal grenz zone. Within the dermis, there is a diffuse histiocytic infiltrate that typically is not centered around nerves (Figure 2).6,7 Mycobacterium leprae can appear scattered throughout or clustered in globi. Mycobacterium leprae stains red with Ziehl-Neelsen or Wade-Fite stains.6,7 Immunohistochemistry reveals a CD4+ helper T cell (TH2) predominance, supported by the increased expression of type 2 reaction cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13.8

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) embodies 10% to 20% of all primary cutaneous lymphomas; it is more prevalent in older adults (age range, 70–82 years) and women. Clinically, DLBCL presents as either single or multiple rapidly progressing nodules or plaques, usually violaceous or blue-red in color.9,10 The most common area of presentation is on the legs, though it also can surface at other sites.9 On histology, DLBCL has clearly malignant features including frequent mitotic figures, large immunoblasts, and involvement throughout the dermis as well as perivascularly (Figure 3). Spindle-shaped cells and anaplastic features can be present. Immunohistochemically, DLBCL stains strongly positive for CD20 and B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) along with other pan–B-cell markers.9-11 The aggressive leg type of DLBCL stains positively for multiple myeloma oncogene 1 (MUM-1).9,11

Cutaneous metastatic adenocarcinoma from internal malignancies occurs in approximately 5% of cancer patients with metastatic spread.12 Most of these cutaneous lesions develop in close proximity to the primary tumor such as on the trunk, head, or neck. All cutaneous metastases carry a poor prognosis. Clinical presentation can vary greatly, ranging from painless, firm, or elastic nodules to lesions that mimic inflammatory skin conditions such as erysipelas or scleroderma. The majority of these metastases develop as painless firm nodules that are flesh colored, pink, red-brown, or purple.12,13 The histopathology of metastatic adenocarcinoma demonstrates an infiltrative nodular appearance, though there rarely are well-circumscribed nodules found.13 The lesion originates in the dermis or subcutaneous tissue. It is a glandulartype lesion that may reflect the tissue of the primary tumor (Figure 4).12,14 Immunohistochemical stains likely will remain consistent with those of the primary tumor, which is not always the case.14

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is an aggressive cutaneous malignancy of epithelial and neuroendocrine origin, first described as trabecular carcinoma due to the arrangement of tumor resembling cancellous bone.15,16 Merkel cells are mechanoreceptors found near nerve terminals.17 Approximately 80% of MCCs are associated with Merkel cell polyomavirus, which is a small, double-stranded DNA virus with an icosahedral capsid.17,18 Merkel cell polyomavirus–positive cases of MCC tend to have a better prognosis. In Merkel cell polyomavirus–negative MCC, there is an association with UV damage and increased chromosomal aberrations.18 Merkel cell carcinoma is known for its high rate of recurrence as well as local and distant metastasis. Nodal involvement is the most important prognostic indicator.15 Clinically, MCC is associated with the AEIOU mnemonic (asymptomatic, expanding rapidly, immunosuppression, older than 50 years, UV exposed/fair skin).15-17 Lesions appear as red-blue papules on sun-exposed skin and usually are smaller than 2 cm by their greatest dimension. On histopathology, MCC demonstrates small, round, blue cells arranged in sheets or nests originating in the dermis and occasionally can infiltrate the subcutis and lymphovascular surroundings (Figure 5).16-19 Cells have scant eosinophilic cytoplasm and may have fine granular chromatin. Numerous mitotic figures and apoptotic cells also are present. On immunohistochemistry, these cells will stain positive for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, anticytokeratin (CAM 5.2), CK20, and CD56. Due to their neuroendocrine derivation, they also are commonly synaptophysin, neuron-specific enolase, and chromogranin A positive. Notably, MCC will stain negative for leukocyte common antigen, CD20, CD3, CD34, and thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1).16,17

Primary cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphoma can be difficult to diagnose and requires urgent treatment. Clinicians and dermatopathologists need to work together to establish the diagnosis. There is a high mortality rate associated with PCGDTL, making prompt recognition and timely treatment critical. Acknowledgments—Thank you to our colleagues with the Penn State Health Hematology/Oncology Department (Hershey, Pennsylvania) for comanagement of this patient.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to our colleagues with the Penn State Health Hematology/Oncology Department (Hershey, Pennsylvania) for comanagement of this patient.

- Merrill ED, Agbay R, Miranda RN, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphomas showing gamma-delta (γδ) phenotype and predominantly epidermotropic pattern are clinicopathologically distinct from classic primary cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41:204-215.

- Foppoli M, Ferreri AJ. Gamma‐delta T‐cell lymphomas. Eur J Haematol. 2015;94:206-218.

- Toro JR, Liewehr DJ, Pabby N, et al. Gamma-delta T-cell phenotype is associated with significantly decreased survival in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2003;101:3407-3412.

- Rubio-Gonzalez B, Zain J, Garcia L, et al. Cutaneous gamma-delta T-cell lymphoma successfully treated with brentuximab vedotin. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1388-1390.

- Tong H, Ren Y, Liu H, et al. Clinical characteristics of T-cell lymphoma associated with hemophagocytic syndrome: comparison of T-cell lymphoma with and without hemophagocytic syndrome. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49:81-87.

- Brehmer-Andersson E. Leprosy. Dermatopathology. New York, NY: Springer; 2006:110-113.

- Massone C, Belachew WA, Schettini A. Histopathology of the lepromatous skin biopsy. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:38-45.

- Naafs B, Noto S. Reactions in leprosy. In: Nunzi E, Massone C, eds. Leprosy: A Practical Guide. Milan, Italy: Springer; 2012:219-239.

- Hope CB, Pincus LB. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas. Clin Lab Med. 2017;37:547-574.

- Billero VL, LaSenna CE, Romanelli M, et al. Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma presenting as chronic non-healing ulcer. Int Wound J. 2017;14:830-832.

- Testo N, Olson L, Subramaniyam S, et al. Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with a MYC-IGH rearrangement and gain of BCL2: expanding the spectrum of MYC/BCL2 double hit lymphomas. Am J Dermatopathol. 2016;38:769-774.

- Boyd AS. Pulmonary signet-ring cell adenocarcinoma metastatic to the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:E66-E68.

- Guanziroli E, Coggi A, Venegoni L, et al. Cutaneous metastases of internal malignancies: an experience from a single institution. Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:609-614.

- Fernandez-Flores A, Cassarino DS. Cutaneous metastasis of adenocarcinoma of the ampulla of Vater. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:758-761.

- Trinidad CM, Torres-Cabala CA, Prieto VG, et. Al. Update on eighth edition American Joint Committee on Cancer classification for Merkel Cell carcinoma and histopathological parameters that determine prognosis. J Clin Pathol. 2017;72:337-340.

- Bandino JP, Purvis CG, Shaffer BR, et al. A comparison of the histopathologic growth patterns between non-Merkel cell small round blue cell tumors and Merkel cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:815-818.

- Mauzo SH, Rerrarotto R, Bell D, et al. Molecular characteristics and potential therapeutic targets in Merkel cell carcinoma. J Clin Pathol. 2016;69:382-390.

- Lowe G, Brewer J, Bordeaux J. Epidemiology and genetics. In: Alam M, Bordeaux JS, Yu SS, eds. Merkel Cell Carcinoma. New York, NY: Springer; 2013:26-28.

- North J, McCalmont T. Histopathologic diagnosis. In: Alam M, Bordeaux JS, Yu SS, eds. Merkel Cell Carcinoma. New York, NY: Springer; 2013:66-69.

- Merrill ED, Agbay R, Miranda RN, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphomas showing gamma-delta (γδ) phenotype and predominantly epidermotropic pattern are clinicopathologically distinct from classic primary cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41:204-215.

- Foppoli M, Ferreri AJ. Gamma‐delta T‐cell lymphomas. Eur J Haematol. 2015;94:206-218.

- Toro JR, Liewehr DJ, Pabby N, et al. Gamma-delta T-cell phenotype is associated with significantly decreased survival in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2003;101:3407-3412.

- Rubio-Gonzalez B, Zain J, Garcia L, et al. Cutaneous gamma-delta T-cell lymphoma successfully treated with brentuximab vedotin. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1388-1390.

- Tong H, Ren Y, Liu H, et al. Clinical characteristics of T-cell lymphoma associated with hemophagocytic syndrome: comparison of T-cell lymphoma with and without hemophagocytic syndrome. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49:81-87.

- Brehmer-Andersson E. Leprosy. Dermatopathology. New York, NY: Springer; 2006:110-113.

- Massone C, Belachew WA, Schettini A. Histopathology of the lepromatous skin biopsy. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:38-45.

- Naafs B, Noto S. Reactions in leprosy. In: Nunzi E, Massone C, eds. Leprosy: A Practical Guide. Milan, Italy: Springer; 2012:219-239.

- Hope CB, Pincus LB. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas. Clin Lab Med. 2017;37:547-574.

- Billero VL, LaSenna CE, Romanelli M, et al. Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma presenting as chronic non-healing ulcer. Int Wound J. 2017;14:830-832.

- Testo N, Olson L, Subramaniyam S, et al. Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with a MYC-IGH rearrangement and gain of BCL2: expanding the spectrum of MYC/BCL2 double hit lymphomas. Am J Dermatopathol. 2016;38:769-774.

- Boyd AS. Pulmonary signet-ring cell adenocarcinoma metastatic to the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:E66-E68.

- Guanziroli E, Coggi A, Venegoni L, et al. Cutaneous metastases of internal malignancies: an experience from a single institution. Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:609-614.

- Fernandez-Flores A, Cassarino DS. Cutaneous metastasis of adenocarcinoma of the ampulla of Vater. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:758-761.

- Trinidad CM, Torres-Cabala CA, Prieto VG, et. Al. Update on eighth edition American Joint Committee on Cancer classification for Merkel Cell carcinoma and histopathological parameters that determine prognosis. J Clin Pathol. 2017;72:337-340.

- Bandino JP, Purvis CG, Shaffer BR, et al. A comparison of the histopathologic growth patterns between non-Merkel cell small round blue cell tumors and Merkel cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:815-818.

- Mauzo SH, Rerrarotto R, Bell D, et al. Molecular characteristics and potential therapeutic targets in Merkel cell carcinoma. J Clin Pathol. 2016;69:382-390.

- Lowe G, Brewer J, Bordeaux J. Epidemiology and genetics. In: Alam M, Bordeaux JS, Yu SS, eds. Merkel Cell Carcinoma. New York, NY: Springer; 2013:26-28.

- North J, McCalmont T. Histopathologic diagnosis. In: Alam M, Bordeaux JS, Yu SS, eds. Merkel Cell Carcinoma. New York, NY: Springer; 2013:66-69.

A 71-year-old man presented with an eruption on the face, shoulders, upper back, and arms of 3 weeks’ duration. The lesions were asymptomatic, and he denied fever, chills, or weight loss. He had a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia. Physical examination revealed coarse facial features with purple-pink nodules on the face and trunk and ulcerated nodules on the upper extremities. Mucous membrane involvement was noted, and there was marked occipital and submandibular lymphadenopathy. A biopsy of an arm nodule revealed a superficial and deep dermal and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrate of atypical CD3+ cells.

Depressed Shiny Scars and Crusted Erosions

The Diagnosis: Erythropoietic Protoporphyria

Erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP) is an autosomal-recessive photodermatosis that results from loss of activity of ferrochelatase, the last enzyme in the heme biosynthetic pathway.1 Erythropoietic protoporphyria normally involves sun-exposed areas of the body. Skin that is exposed to sunlight develops intense burning and stinging pain followed by erythema, edema, crusting, and petechiae that develops into waxy scarring over time. In contrast to other porphyrias, blistering generally is not seen.2 Accurate diagnosis often can be delayed by a decade or more following symptom onset due to the prominence of subjective pain as the presenting sign.

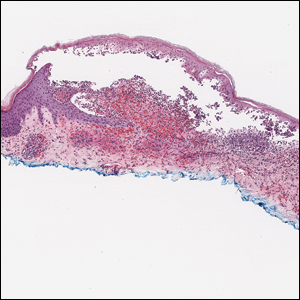

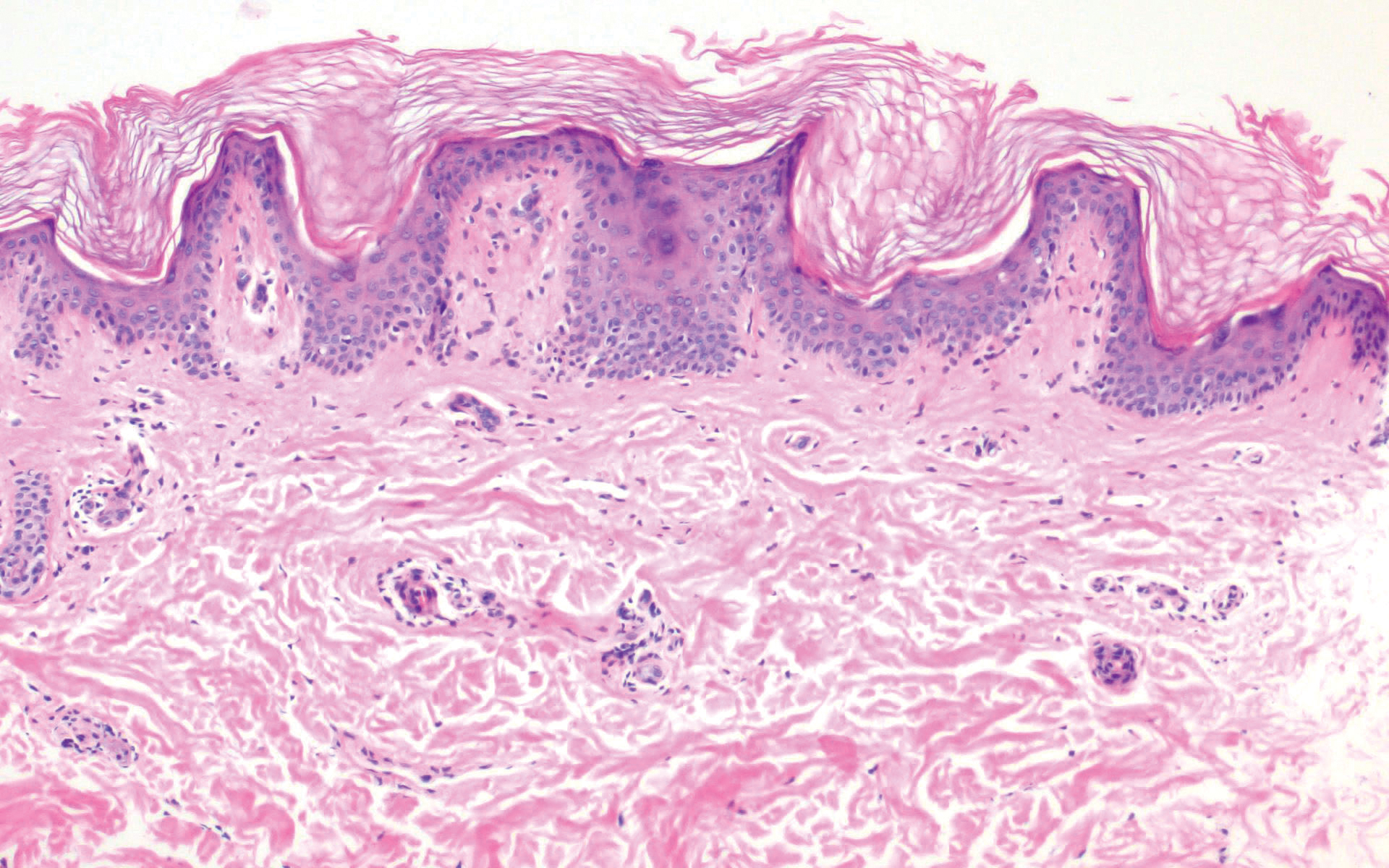

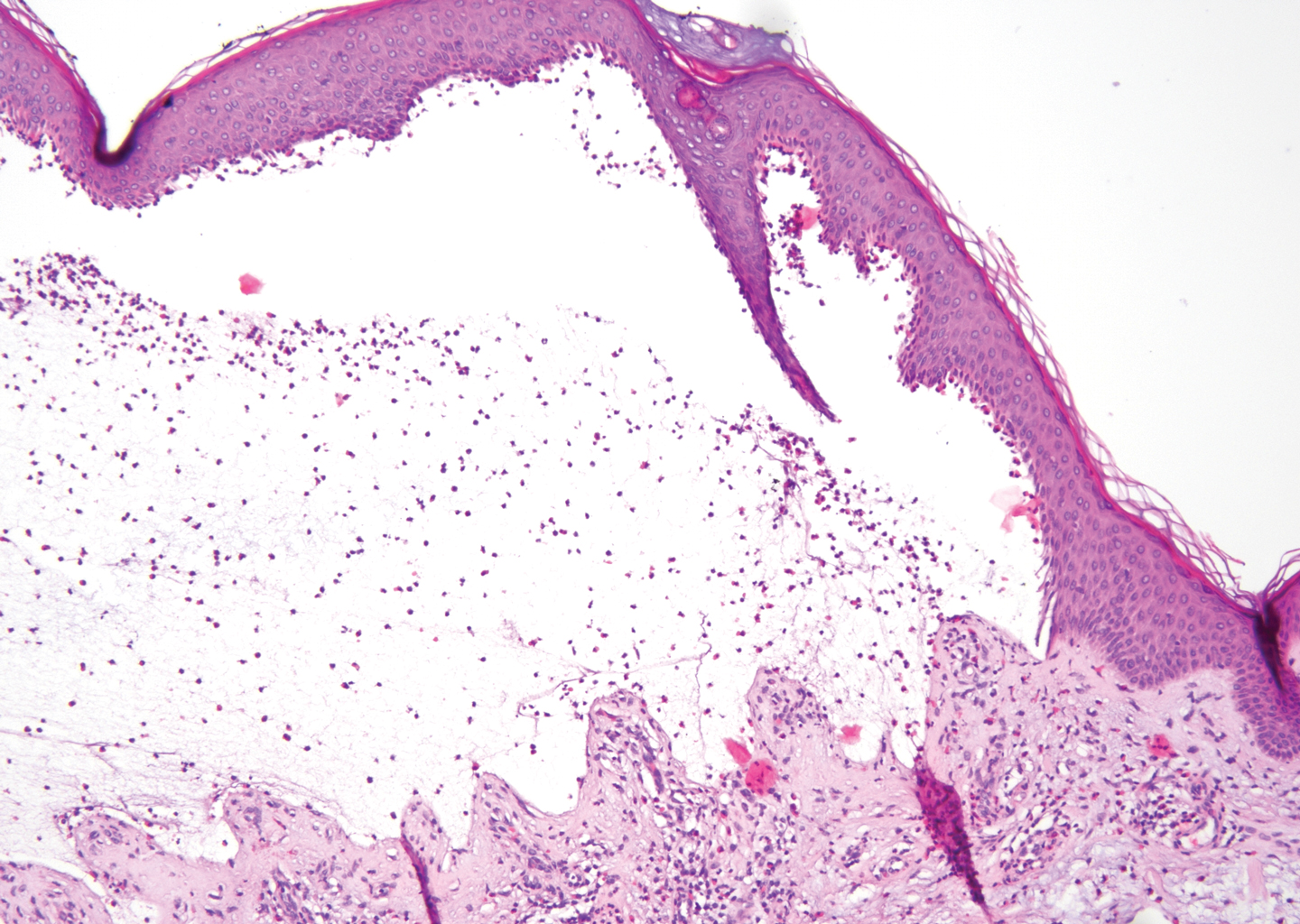

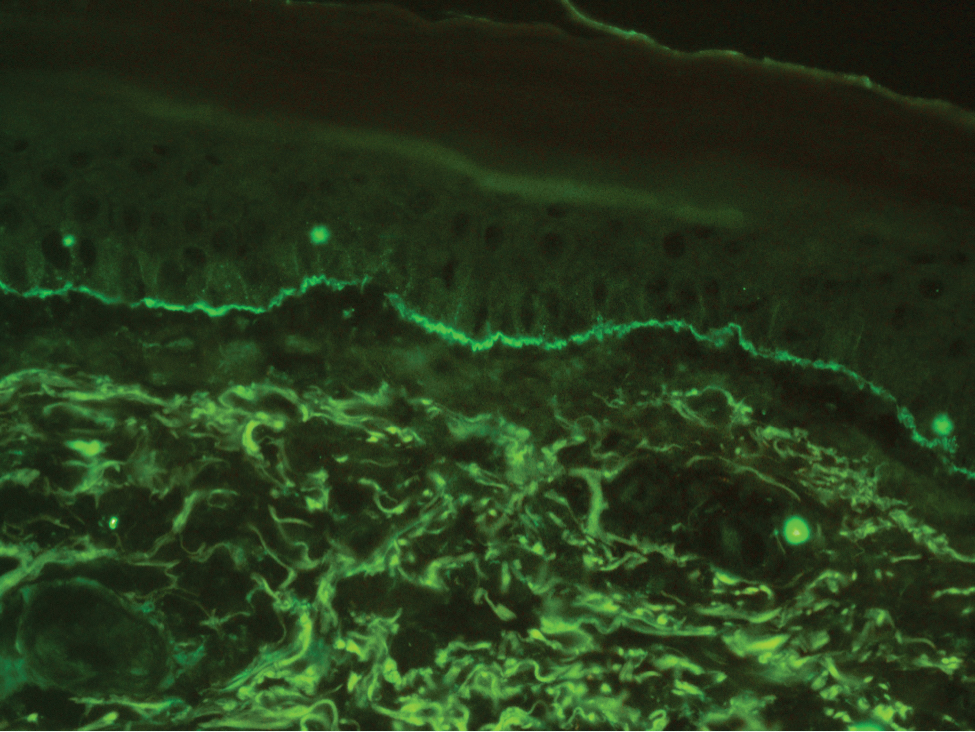

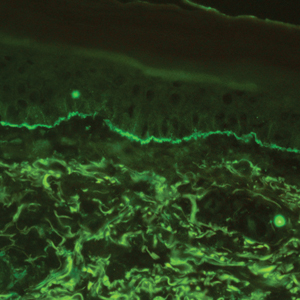

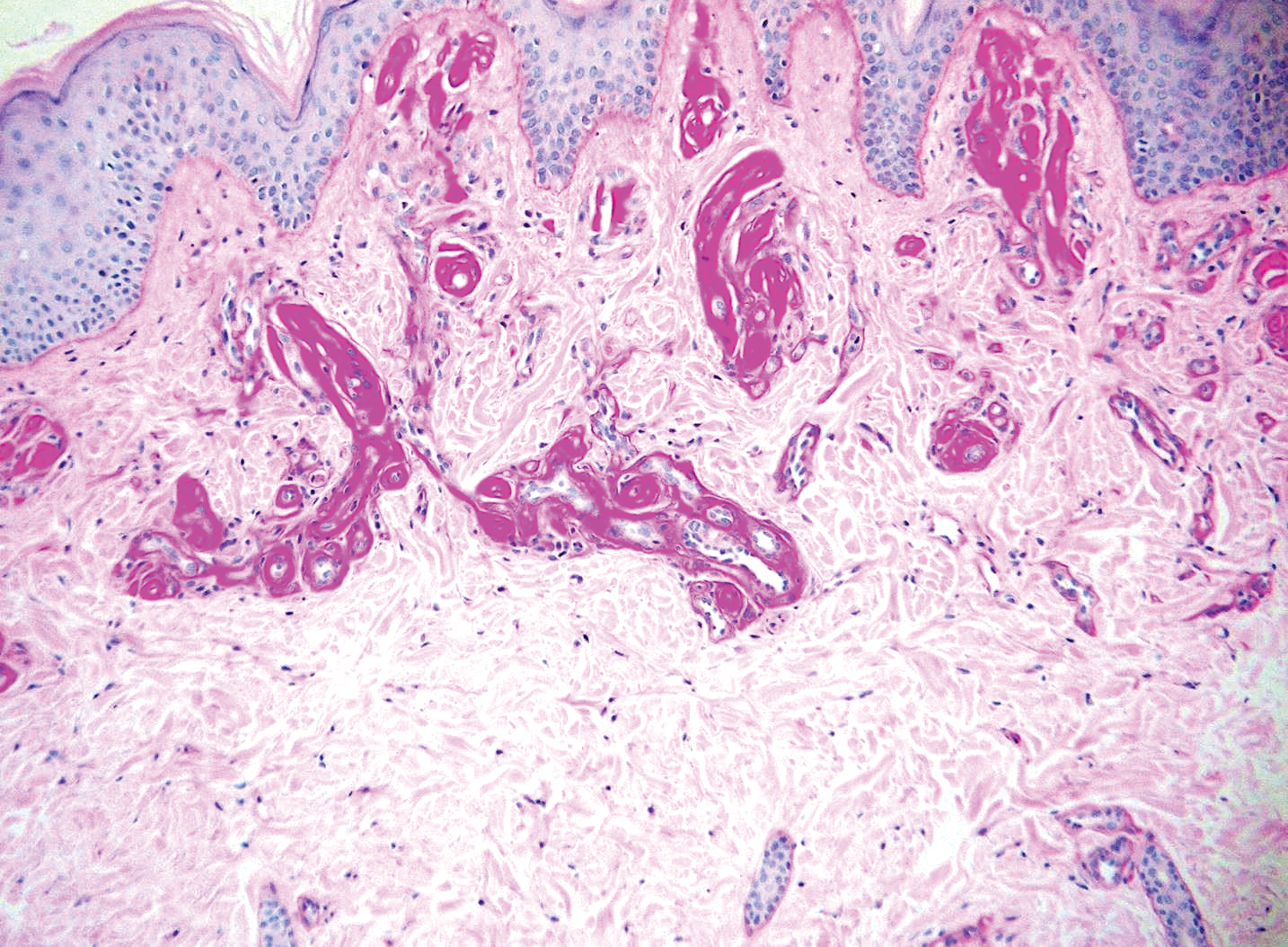

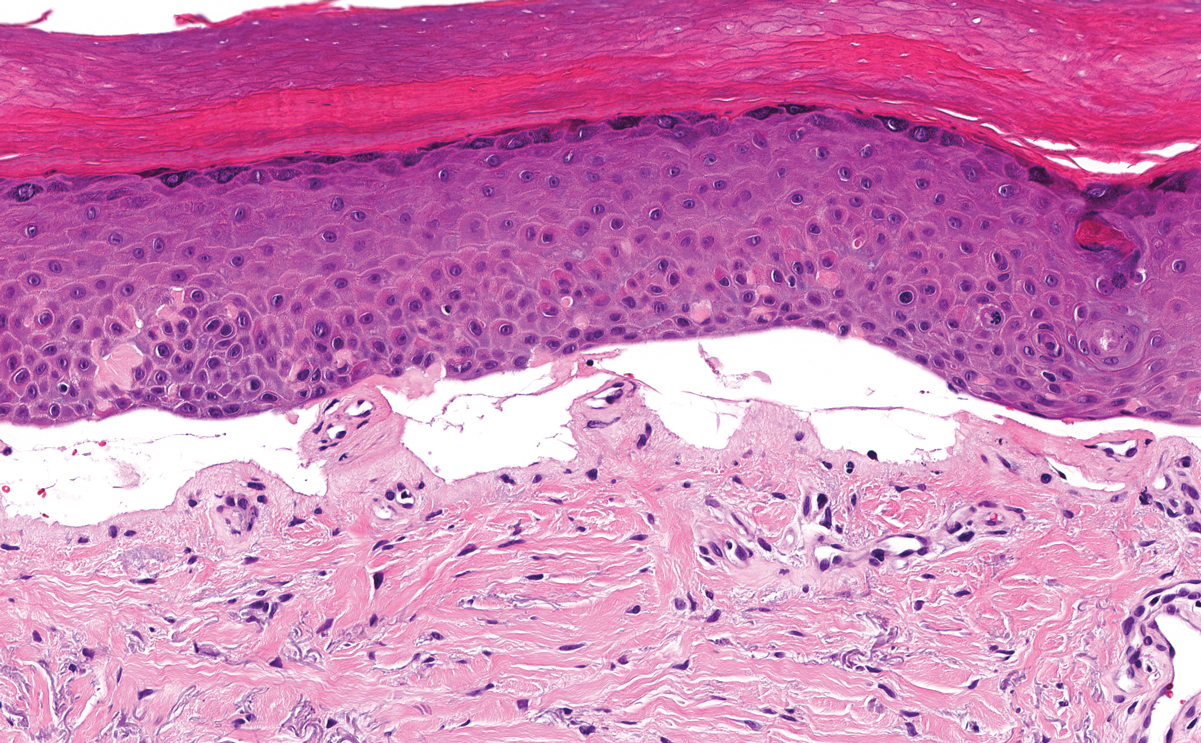

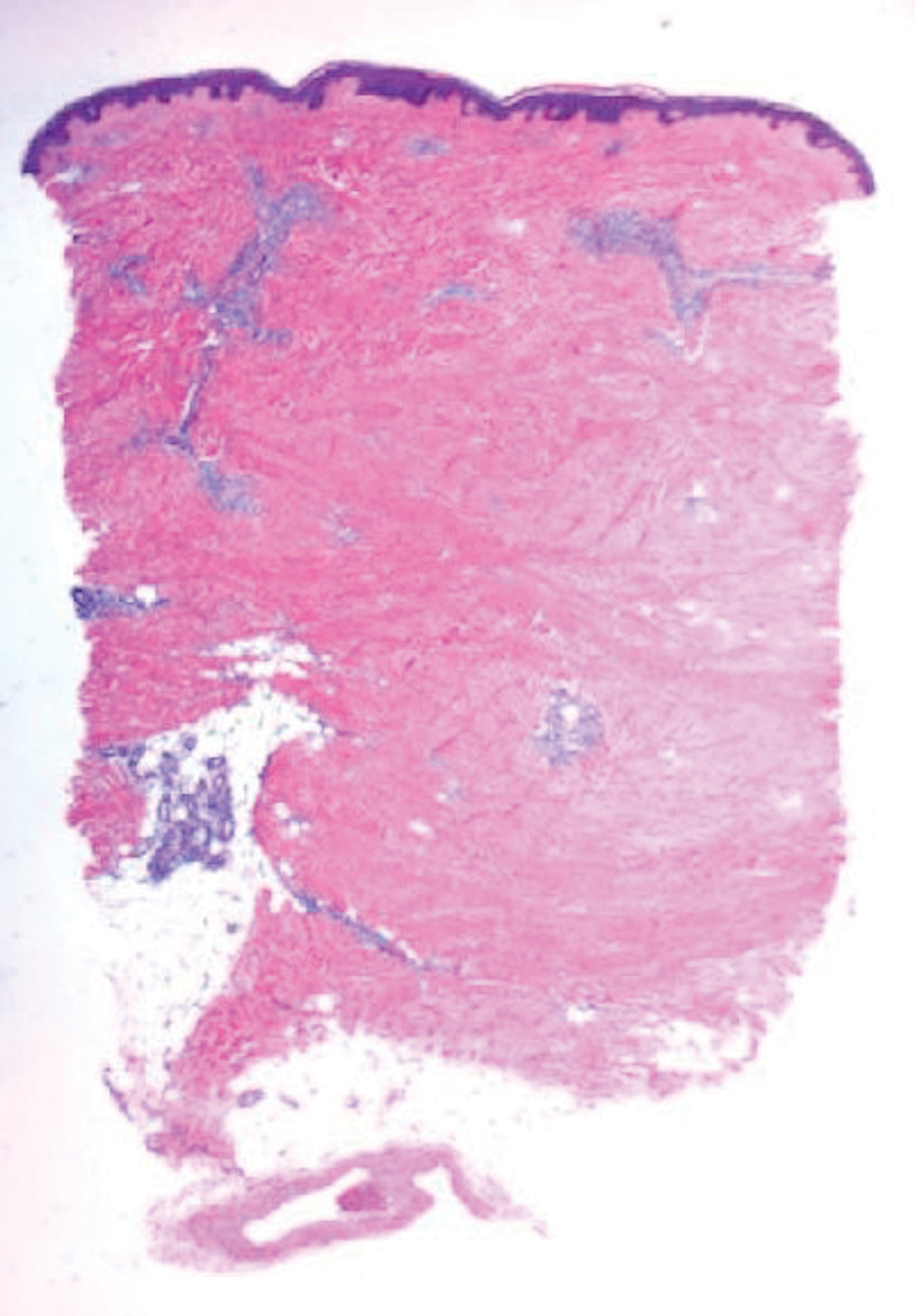

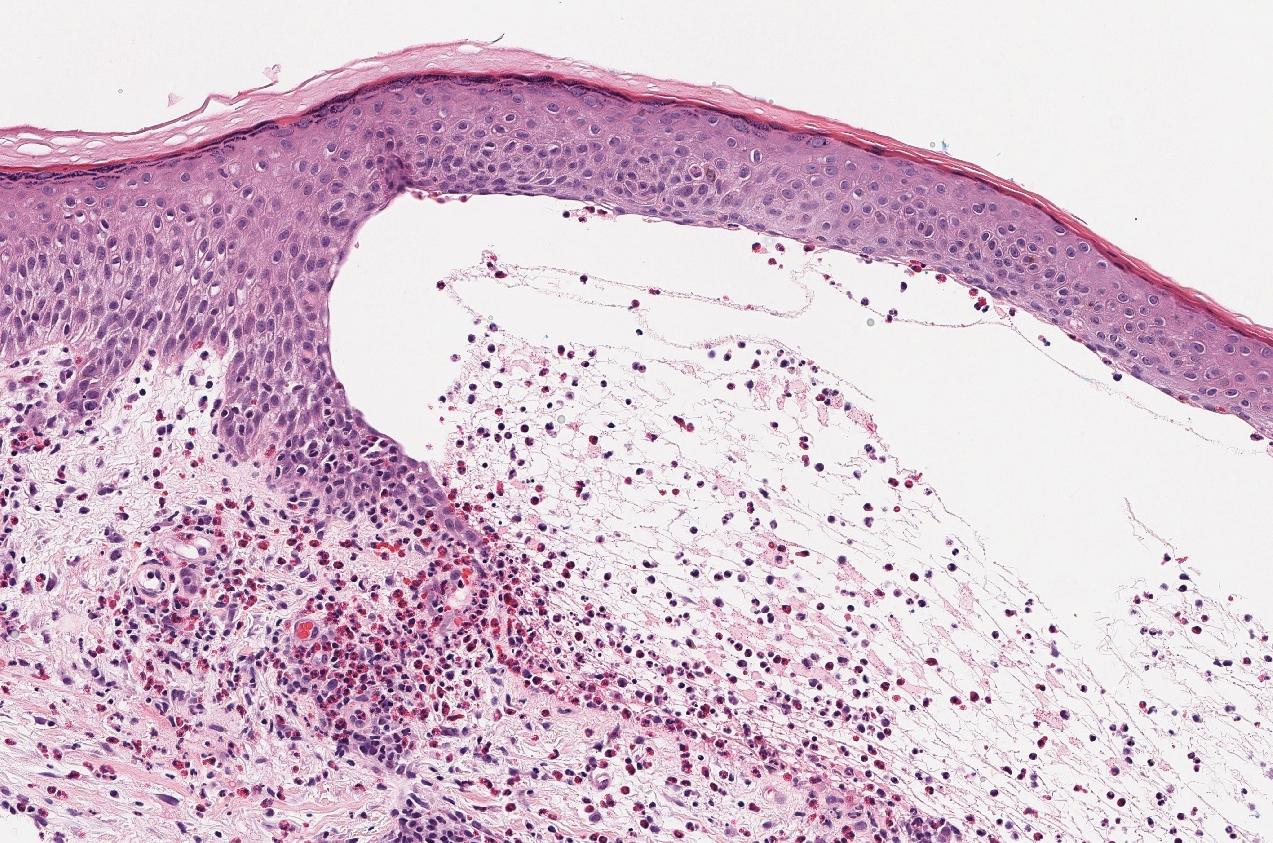

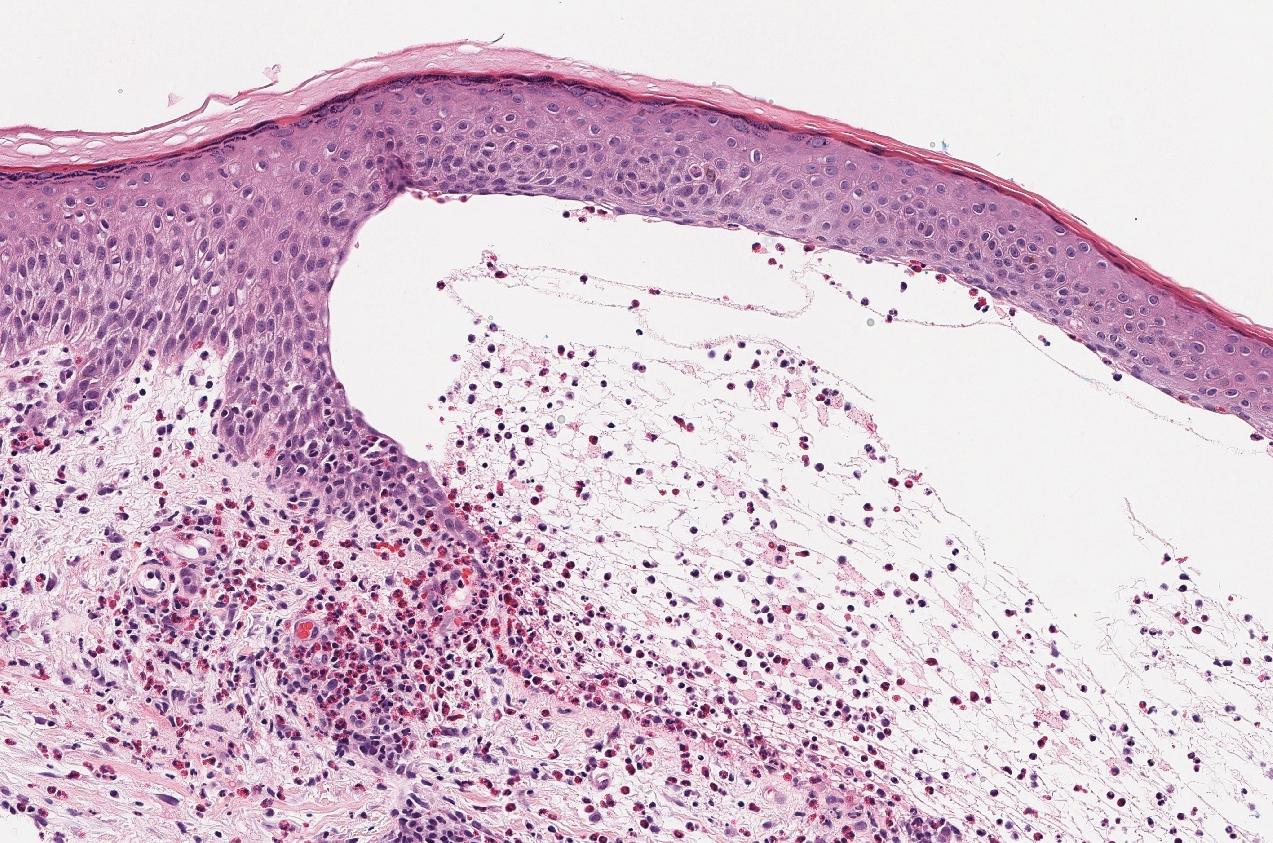

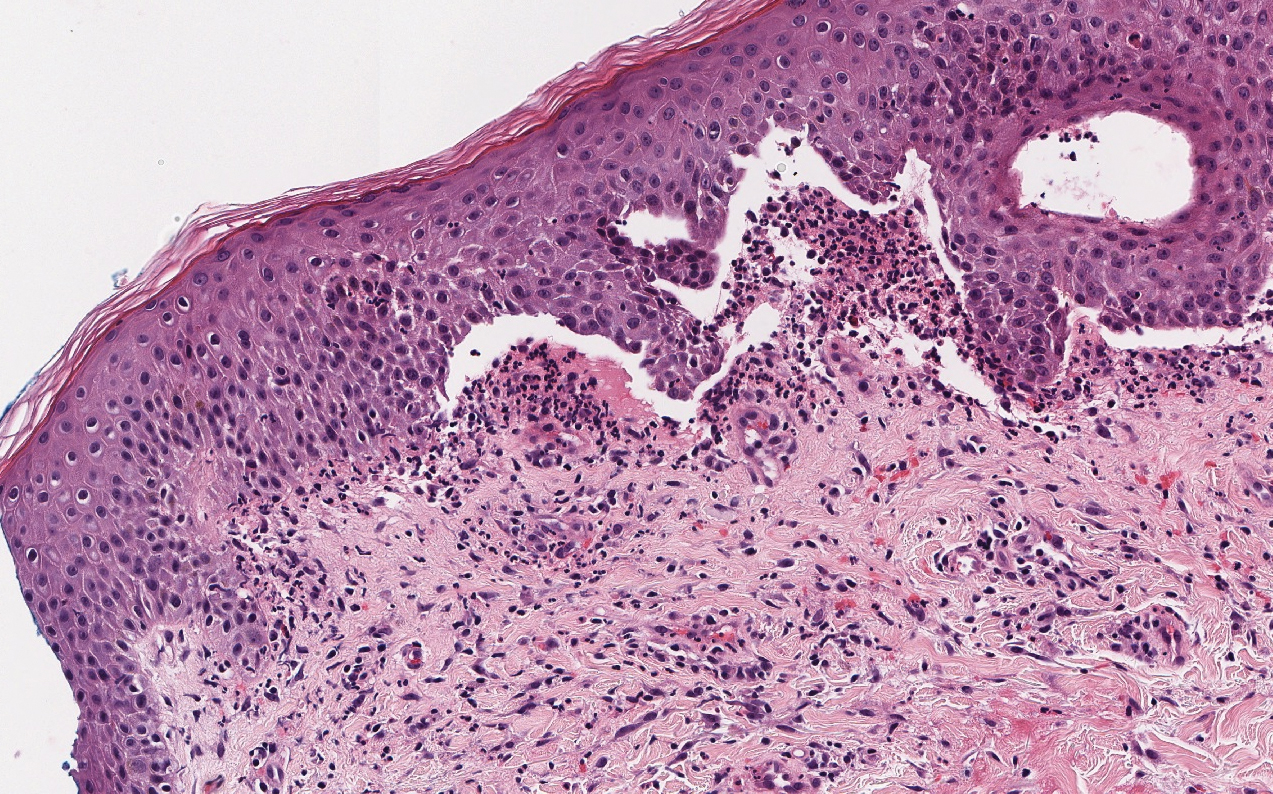

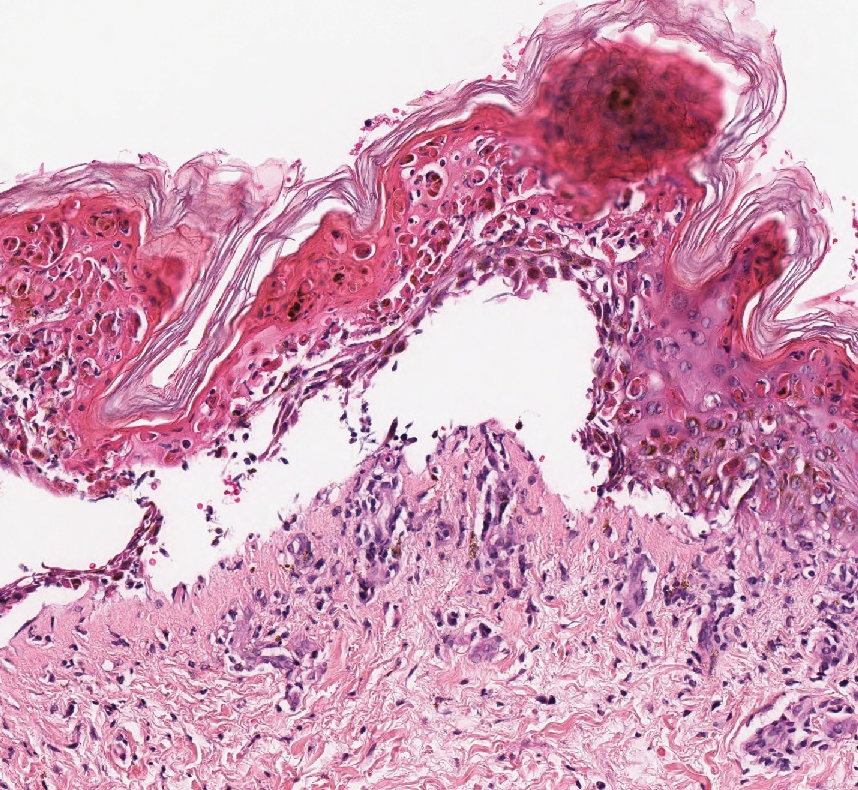

The histologic appearance of EPP differs depending on the chronicity of lesions. Biopsies of acute lesions show vacuolization of epidermal cells with intercellular edema, vacuolization and cytolysis of endothelial cells in superficial blood vessels, and focal red blood cell extravasation.3,4 A largely neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrate can be present.5 Hyaline cuffing develops over time in and around vessels in the papillary and superficial reticular dermis with notable sparing of adnexal structures. The perivascular deposits are strongly periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) positive and diastase resistant (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence shows mainly IgG and some IgM, fibrinogen, and C3 outlining characteristic donut-shaped blood vessels in the papillary dermis.6 The prominent thickness of the perivascular hyaline material depositions and the absence of subepidermal blistering can help differentiate EPP from porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT) and pseudoporphyria.6,7 When the deposition is extensive and involves the surrounding dermis, EPP can mimic colloid milium. Additional histologic differential diagnoses of EPP include other dermal depositional diseases such as lipoid proteinosis and amyloidosis.

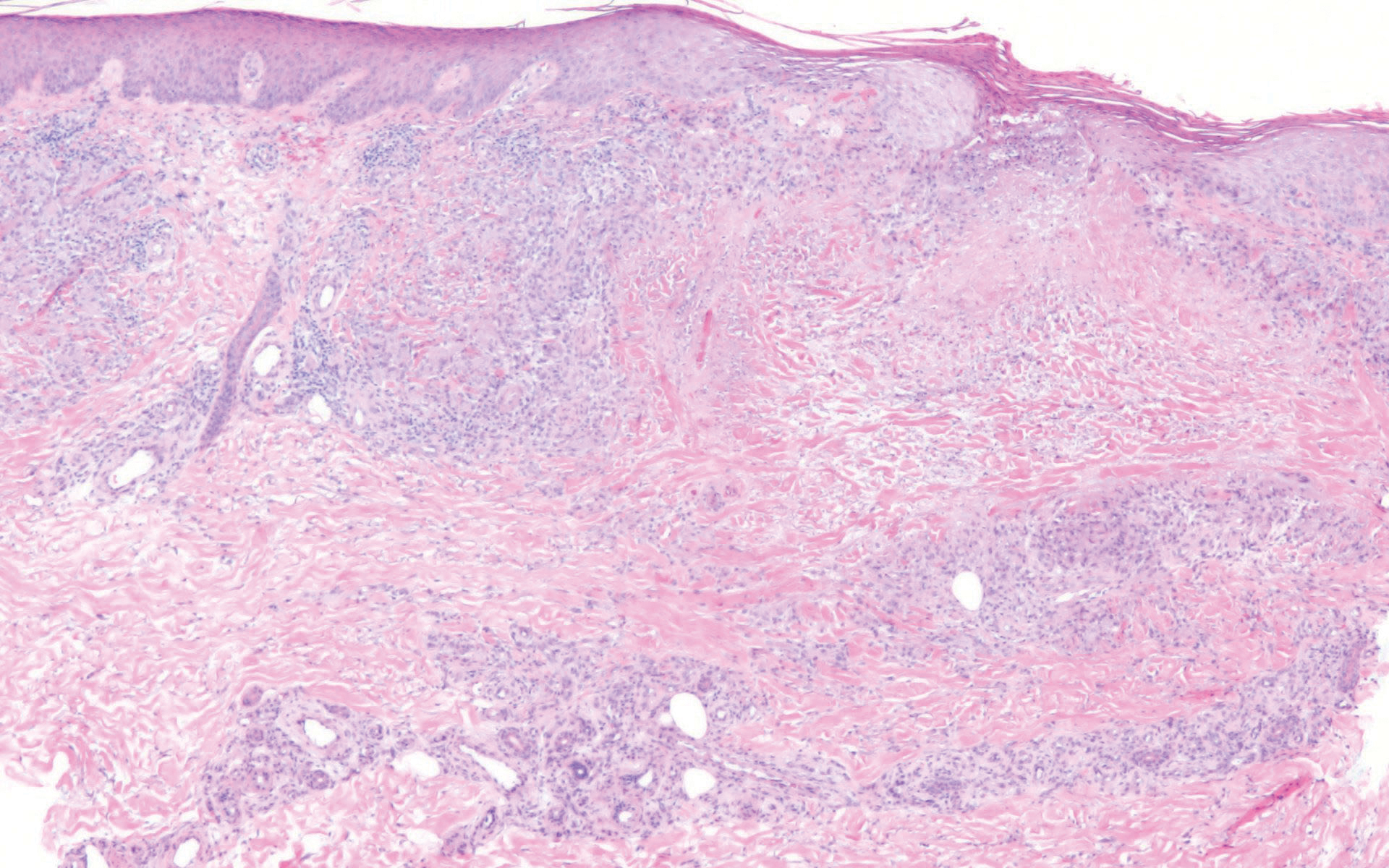

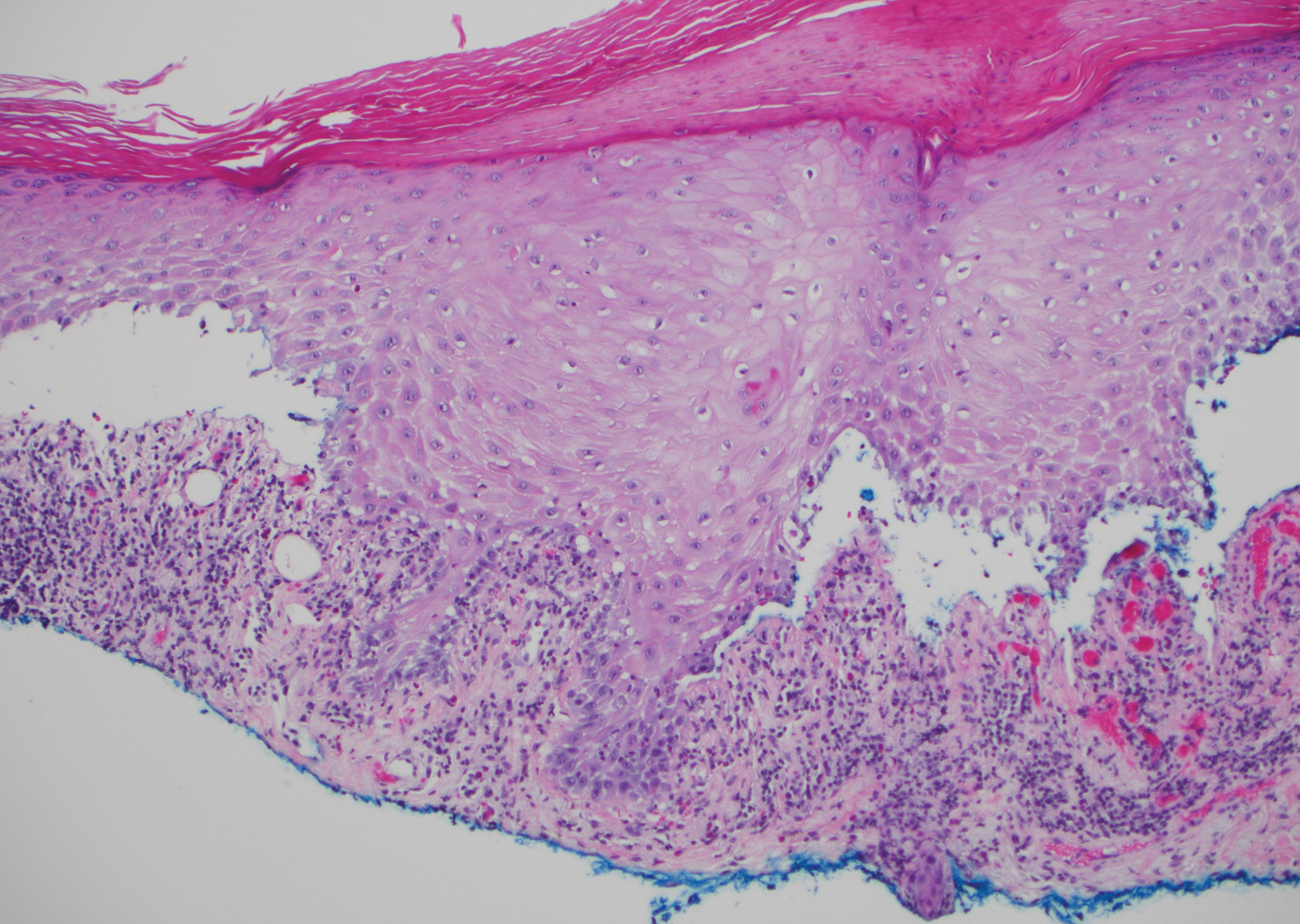

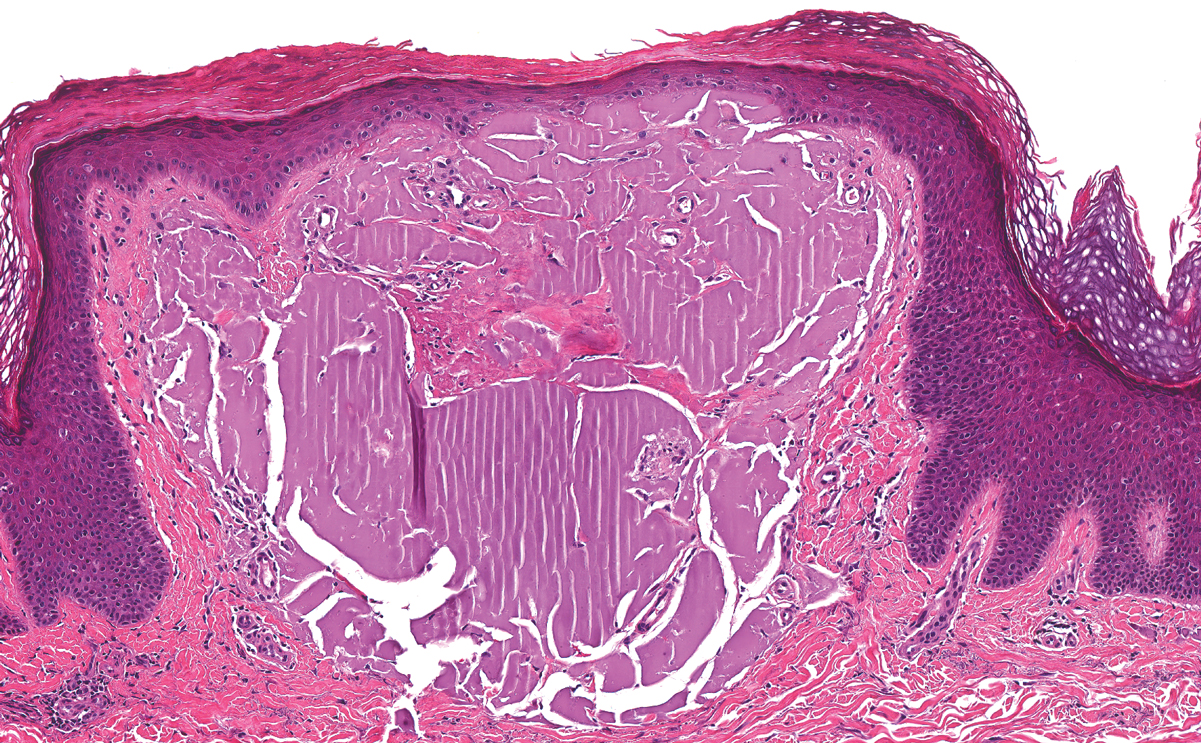

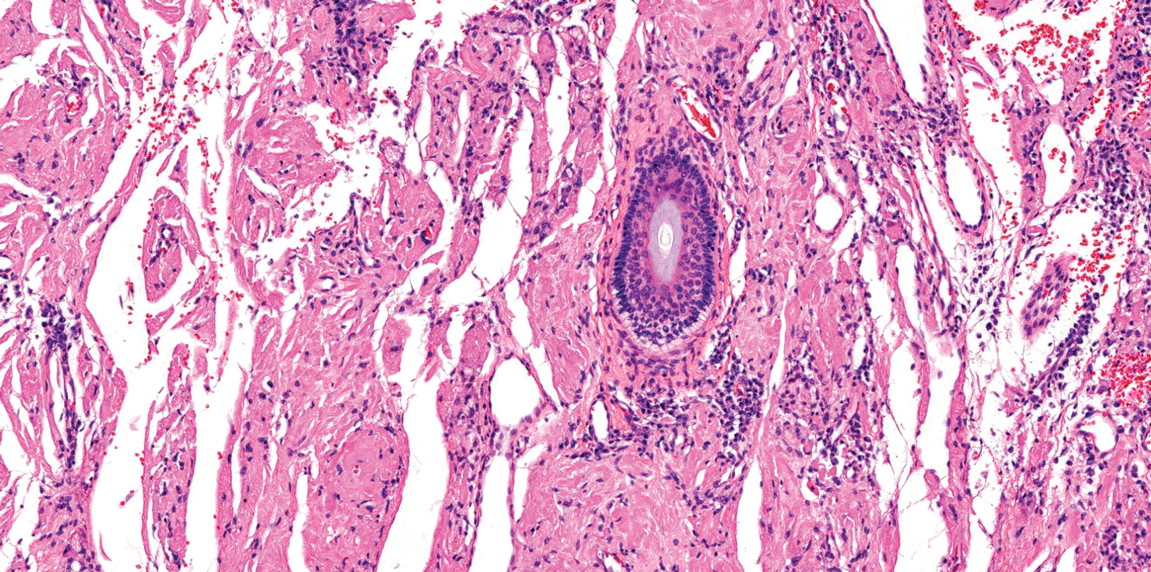

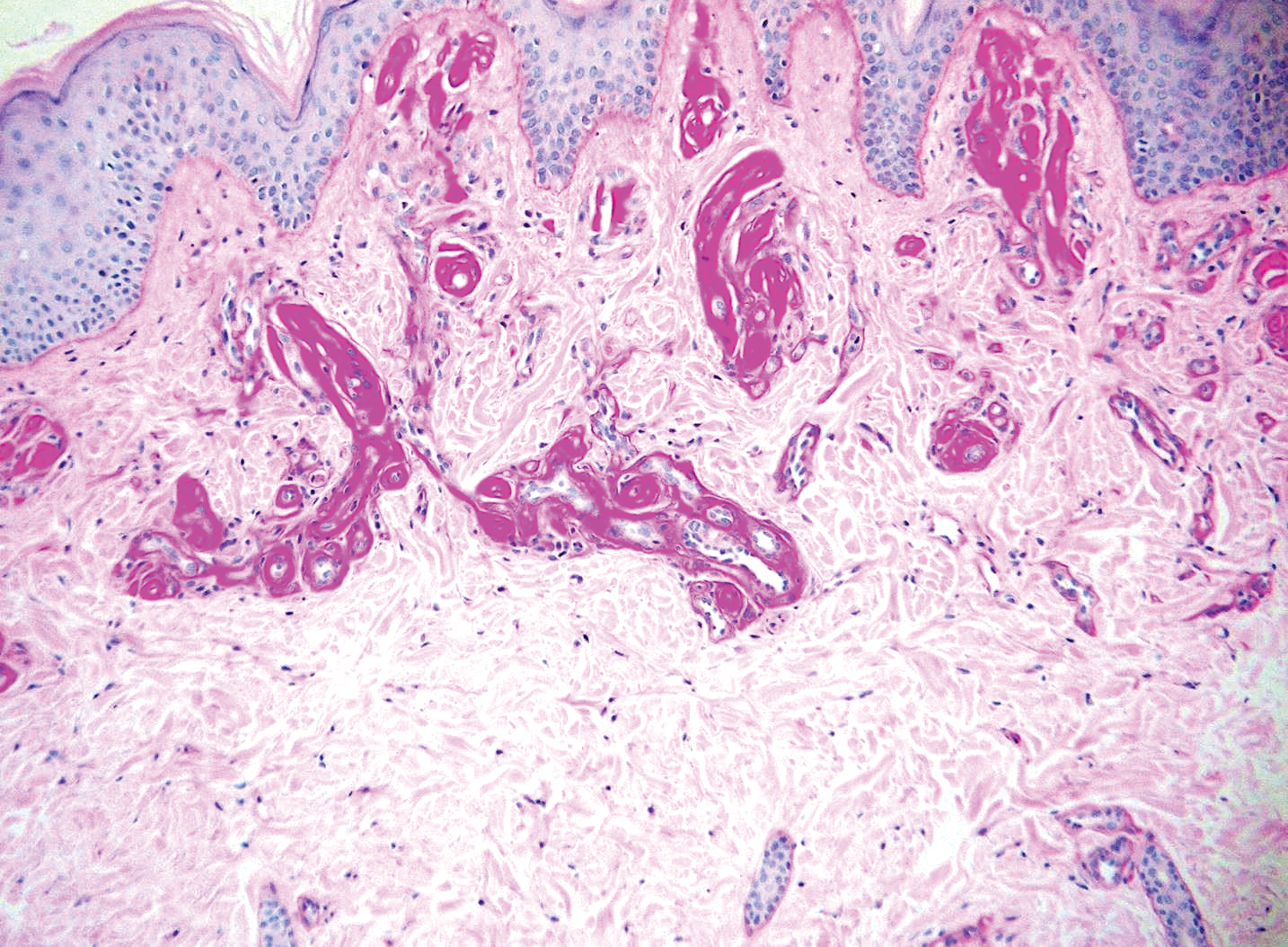

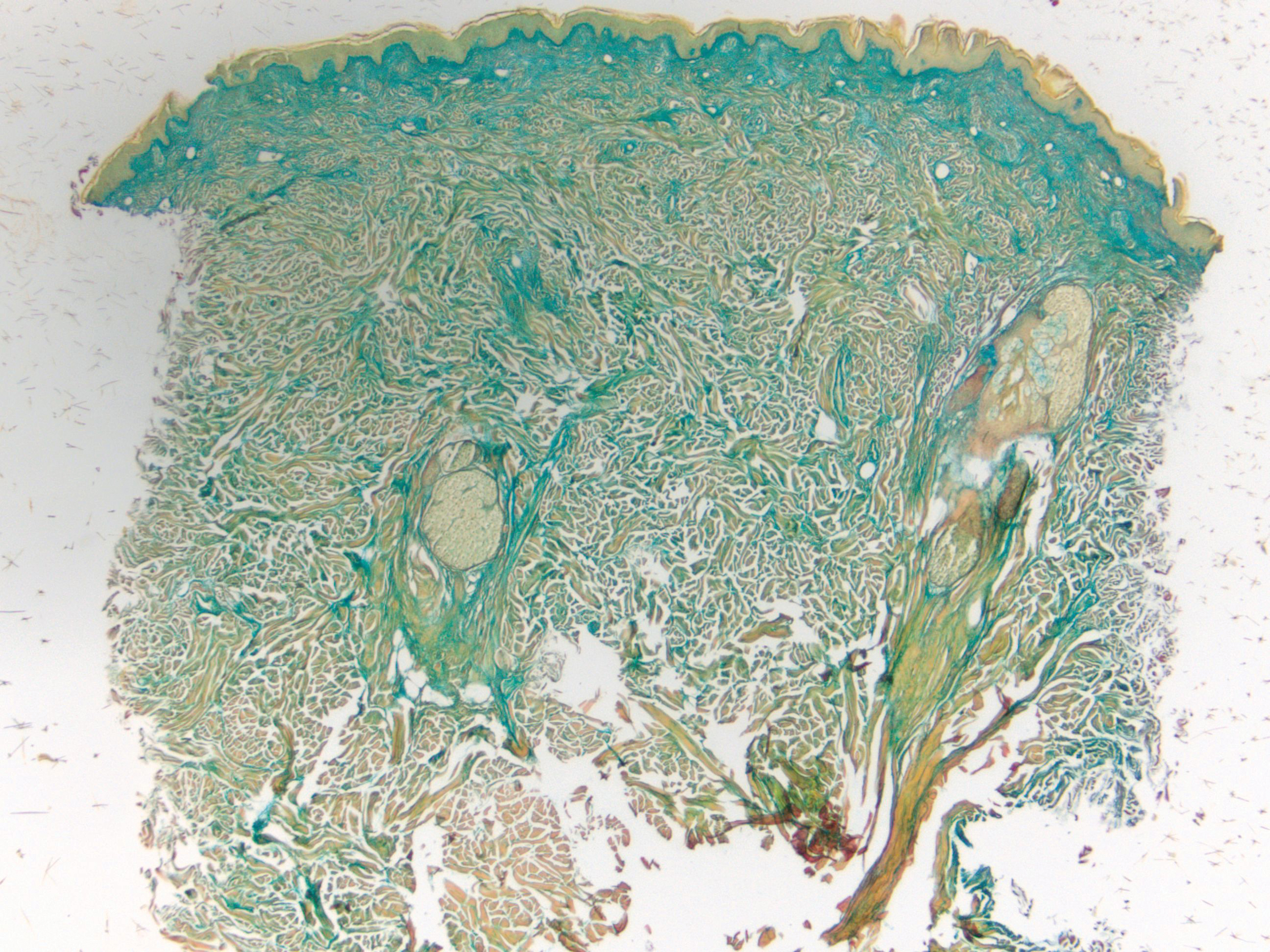

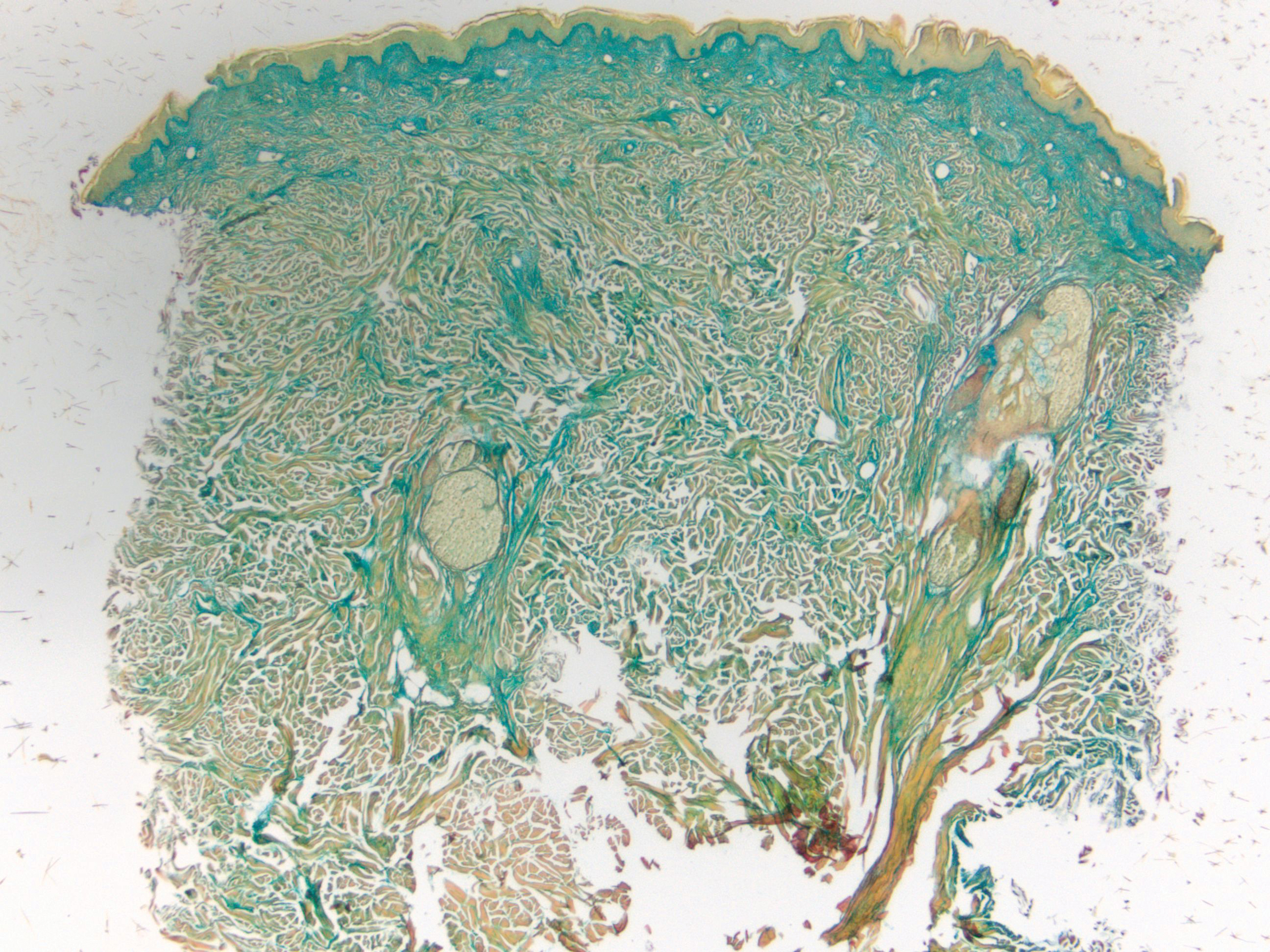

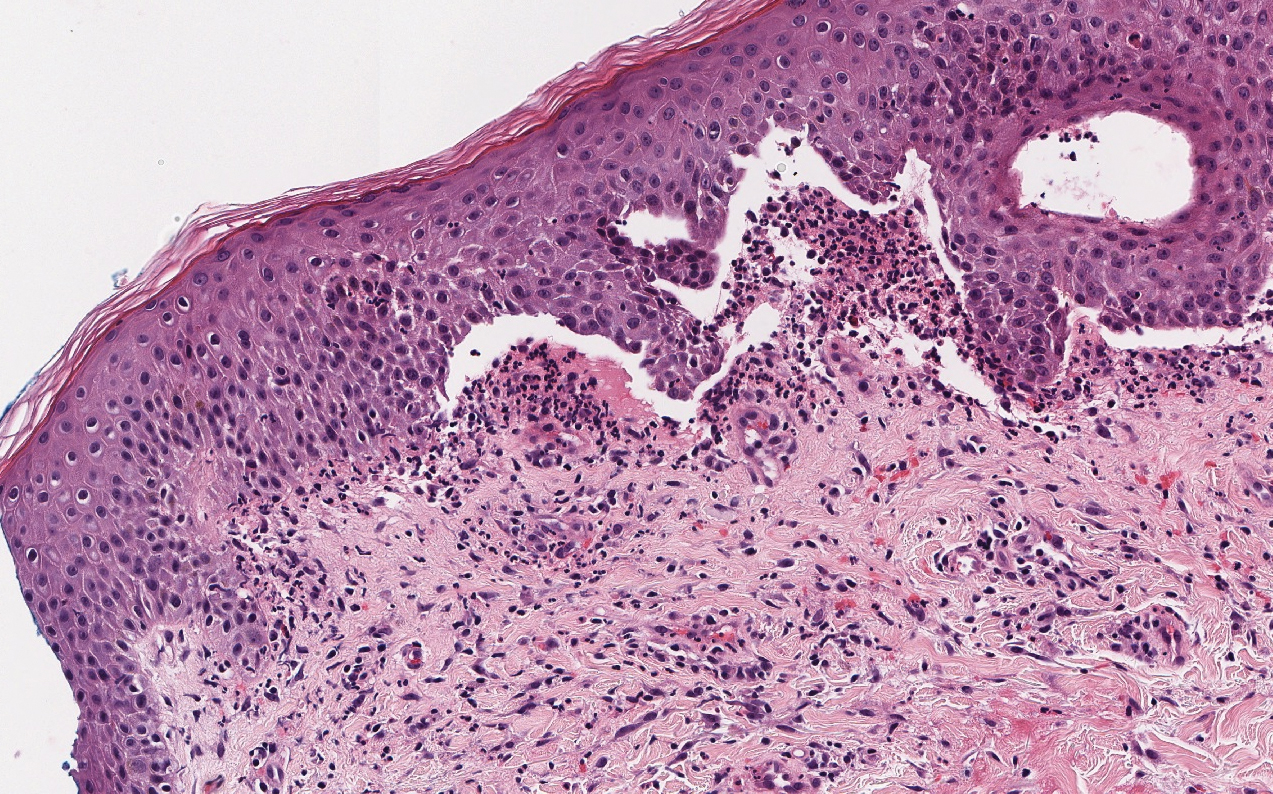

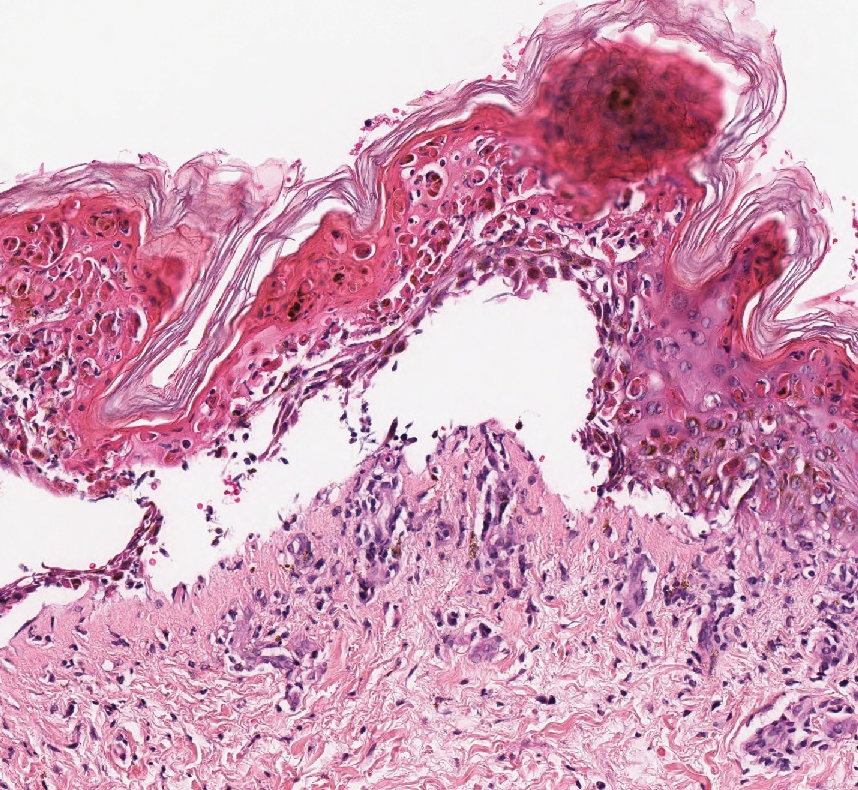

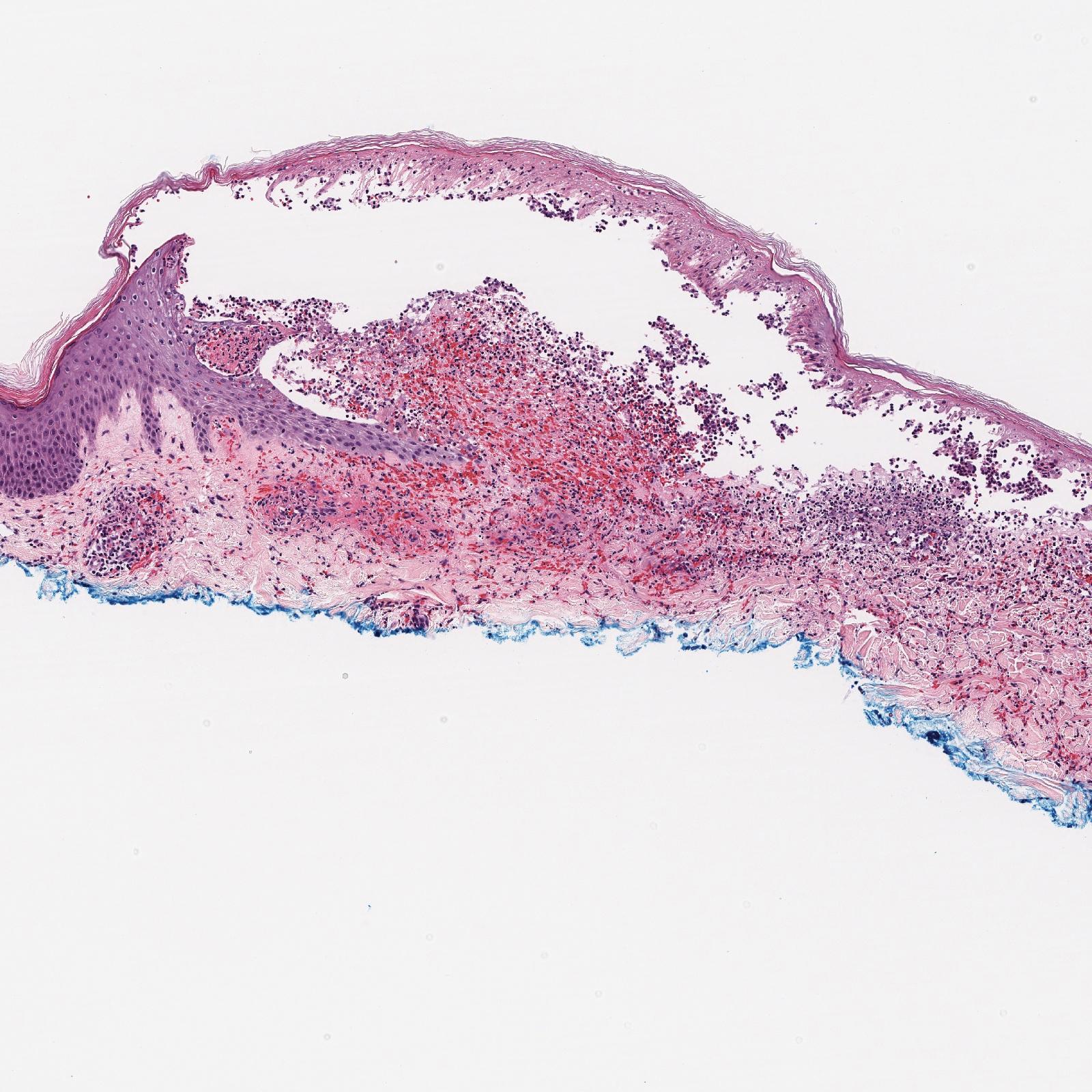

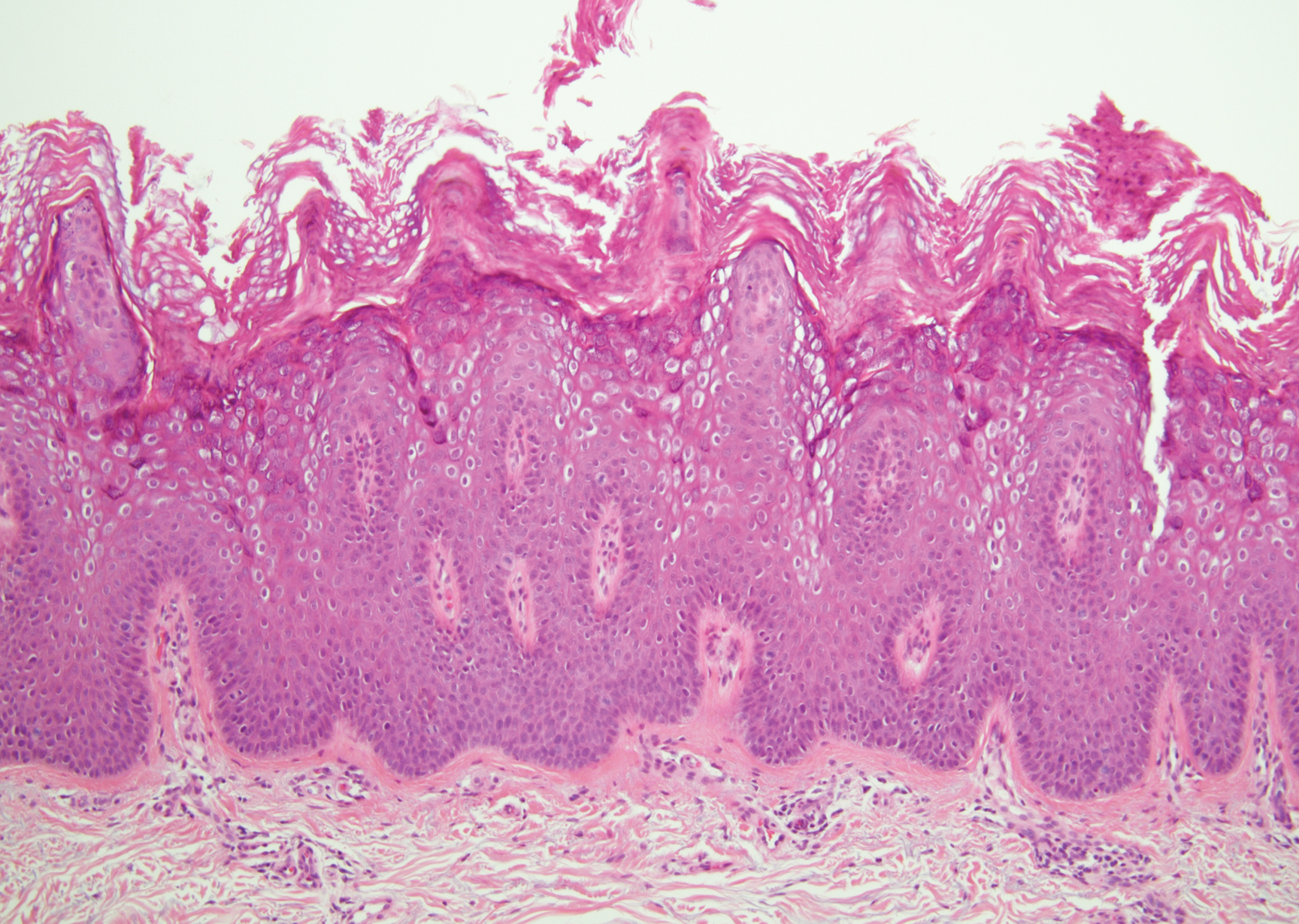

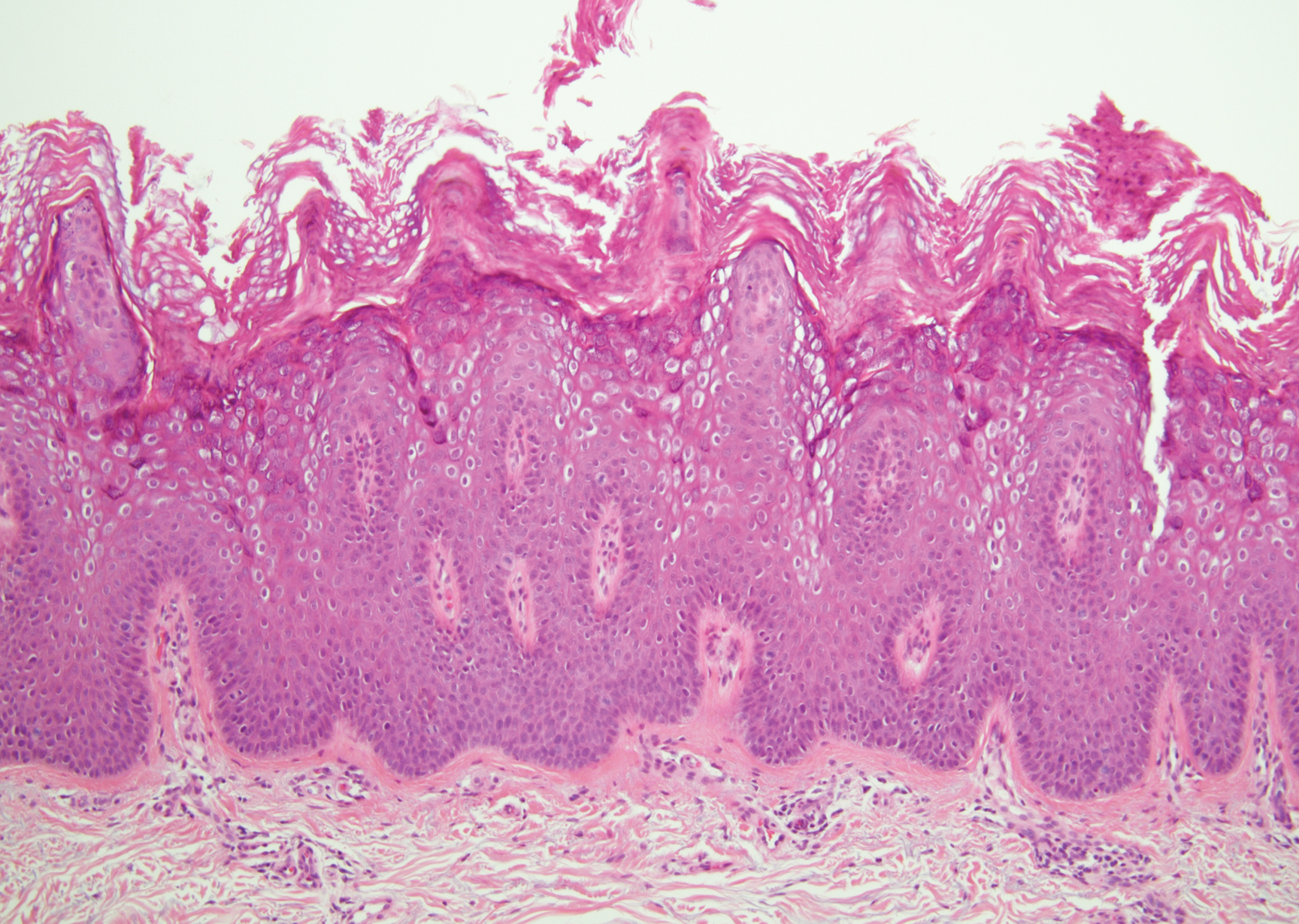

Lipoid proteinosis is an autosomal-recessive multisystem genodermatosis caused by mutations in extracellular matrix gene 1, ECM1. The first clinical sign can be a hoarse cry in infancy due to infiltration of vocal cords.3 Development of papulonodular lesions along the eyelids can result in a string-of-beads appearance called moniliform blepharosis, which is pathognomonic for lipoid proteinosis.6 With chronicity, the involved skin can become yellow, waxy, and thickened, particularly in the flexures or areas of trauma. Histologically, the dermis in lipoid proteinosis becomes diffusely thickened due to deposition of PAS-positive eosinophilic hyaline material that stains weakly with Congo red and thioflavin T.6 Early lesions demonstrate pale pink, hyalinelike thickening of the papillary dermal capillaries. Chronic lesions reveal an acanthotic epidermis, occasional papillomatosis with overlying hyperkeratosis, and a thickened dermis where diffuse thick bundles of pink hyaline deposits are oriented perpendicularly to the dermoepidermal junction.1,6 Lipoid proteinosis can be differentiated from EPP by the involvement of adnexal structures such as hair follicles, sebaceous glands, and arrector pili muscles (Figure 2), as opposed to EPP where adnexal structures are spared.1 Additionally, depositions in lipoid proteinosis are centered around both superficial and deep vessels with an onion skin-like pattern, while EPP involves mainly superficial vessels with more mild and focal hyalinization.

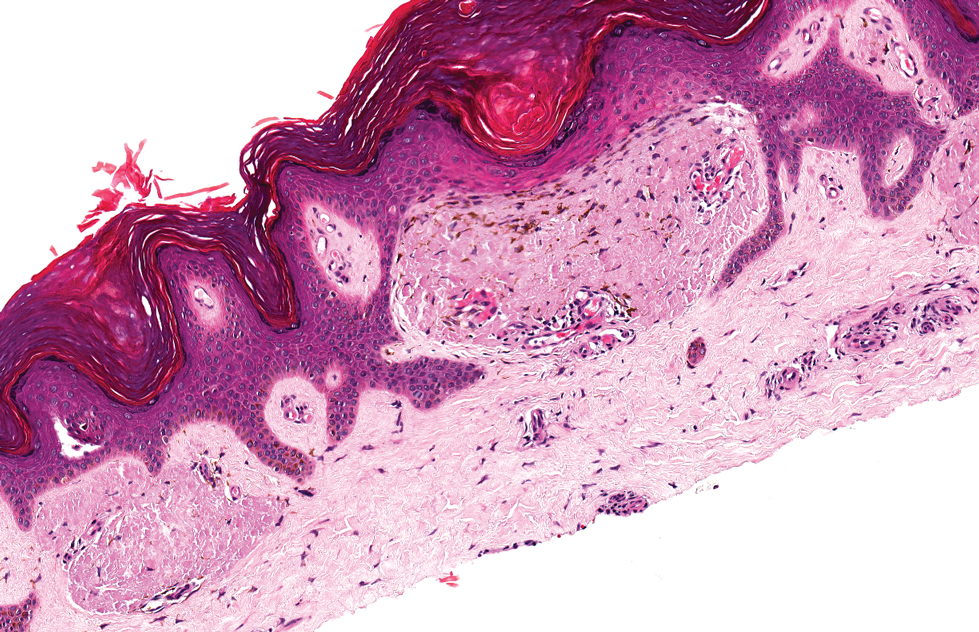

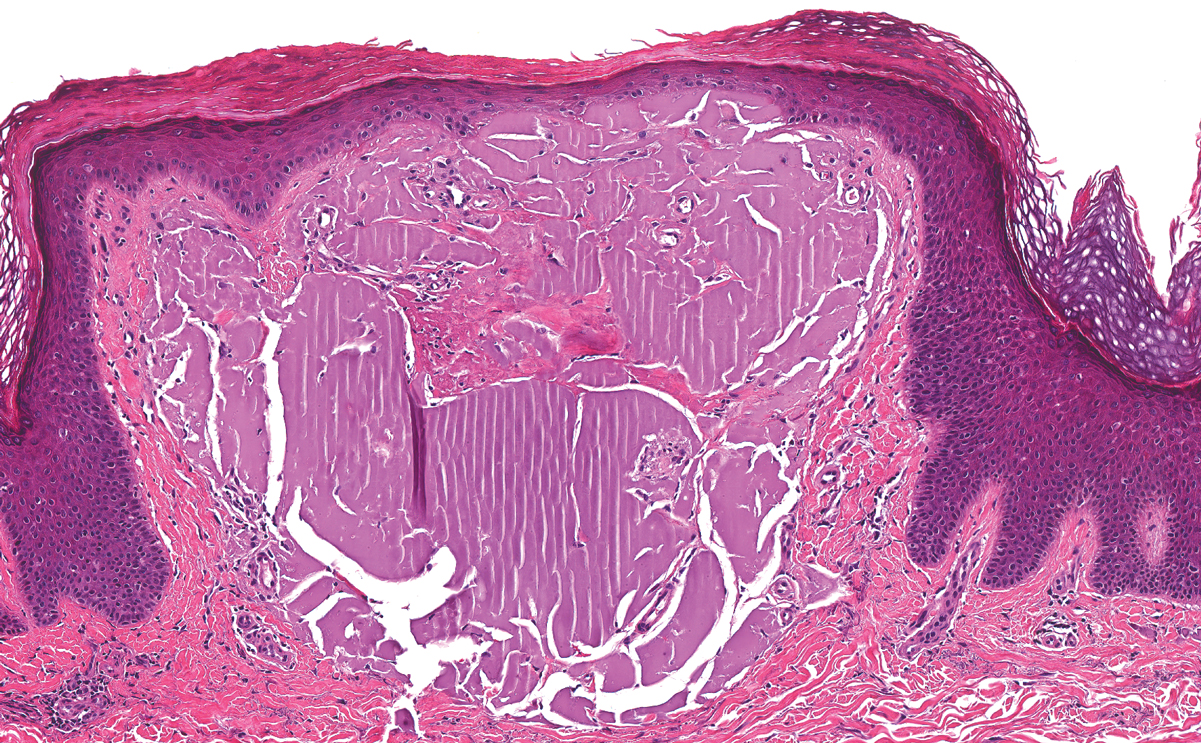

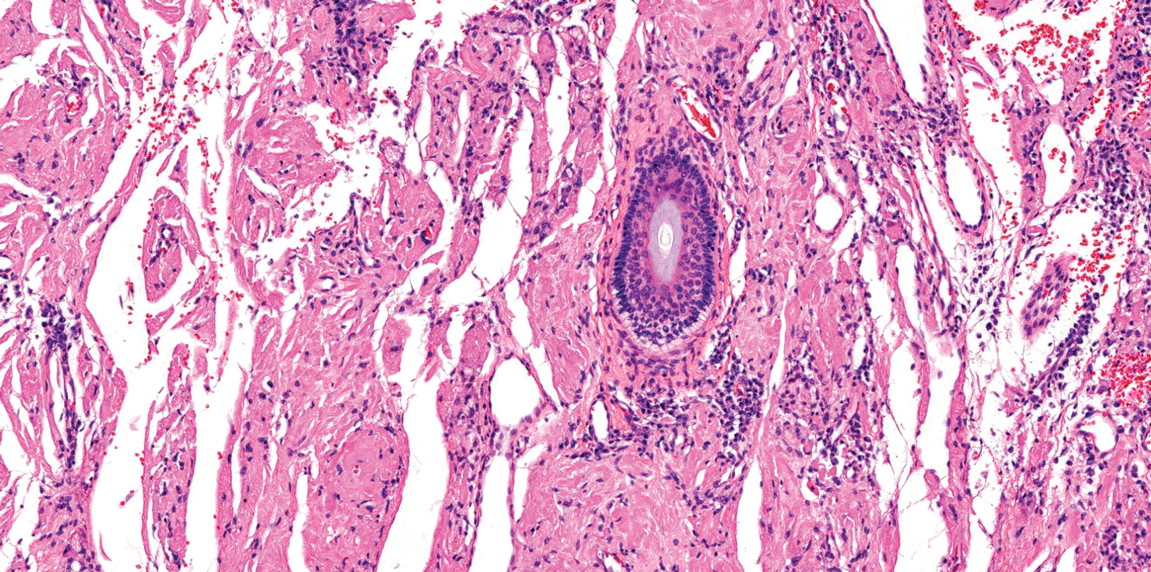

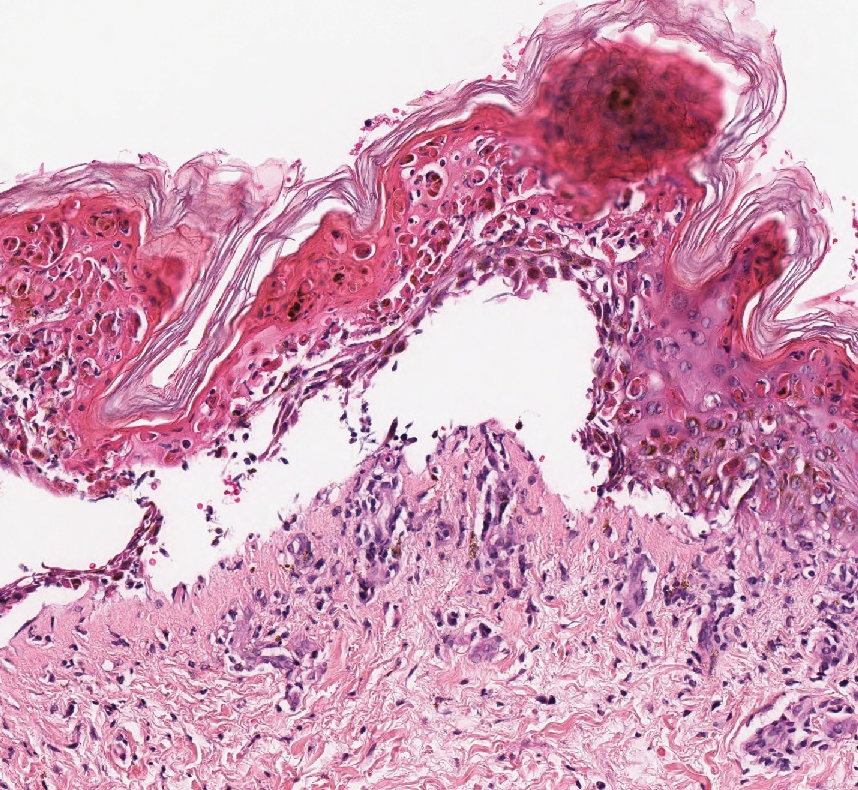

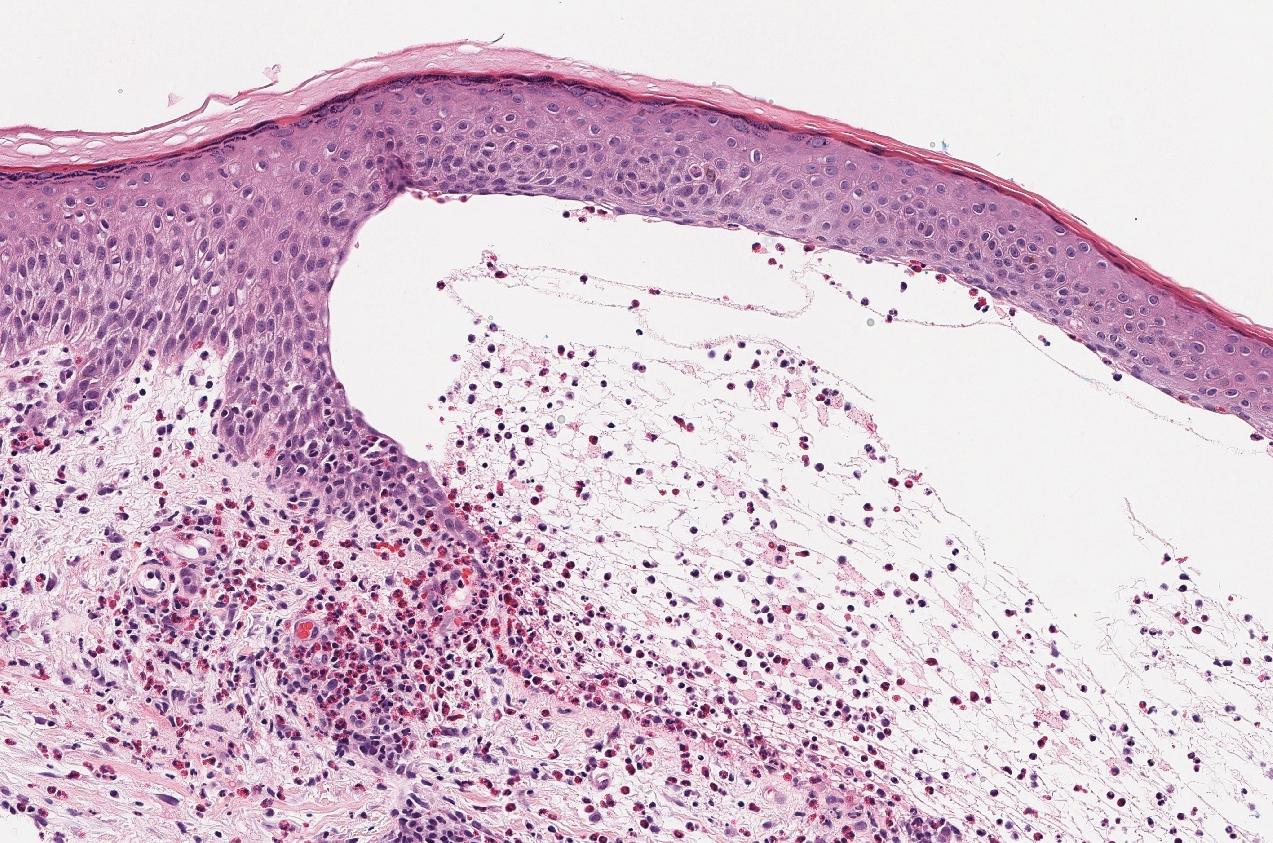

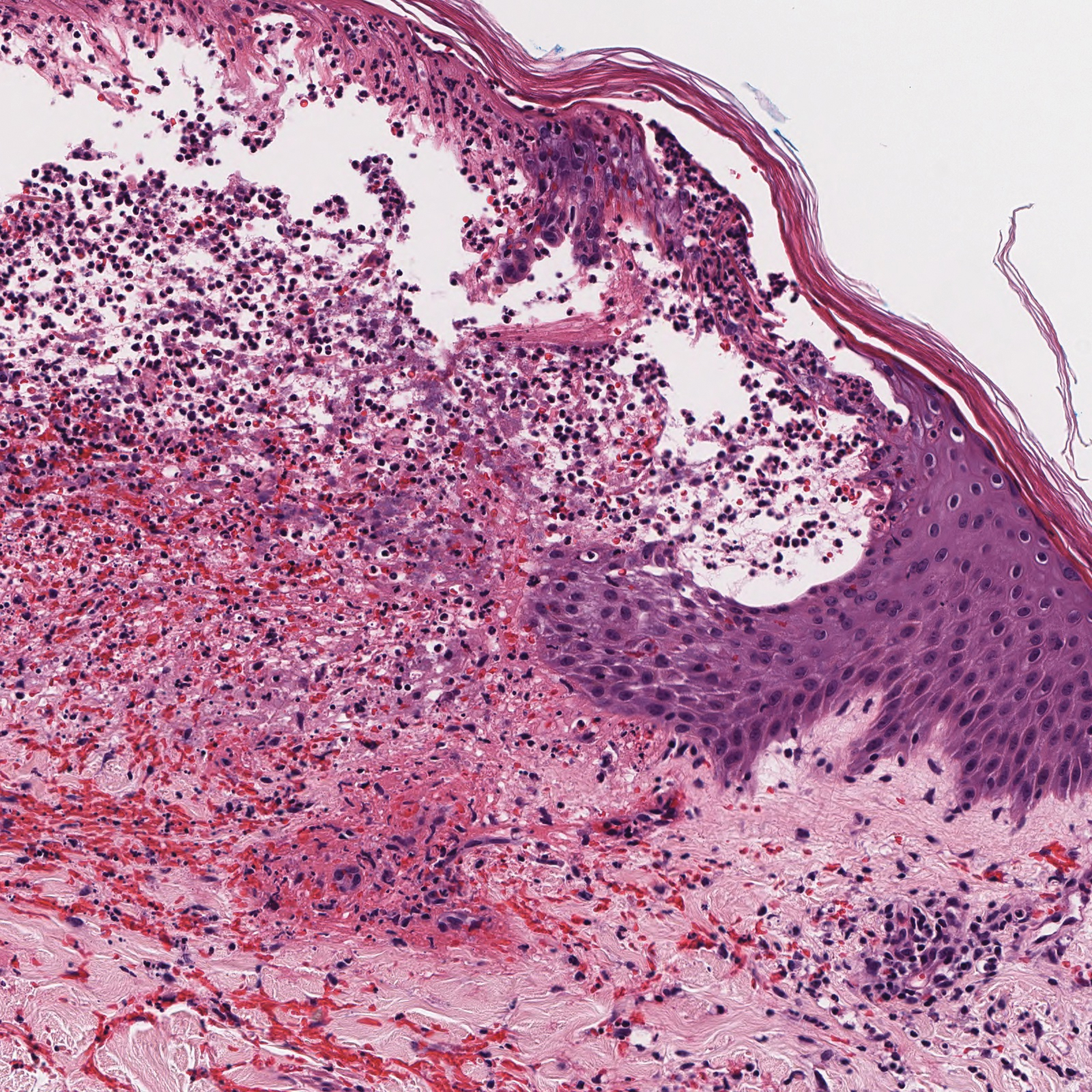

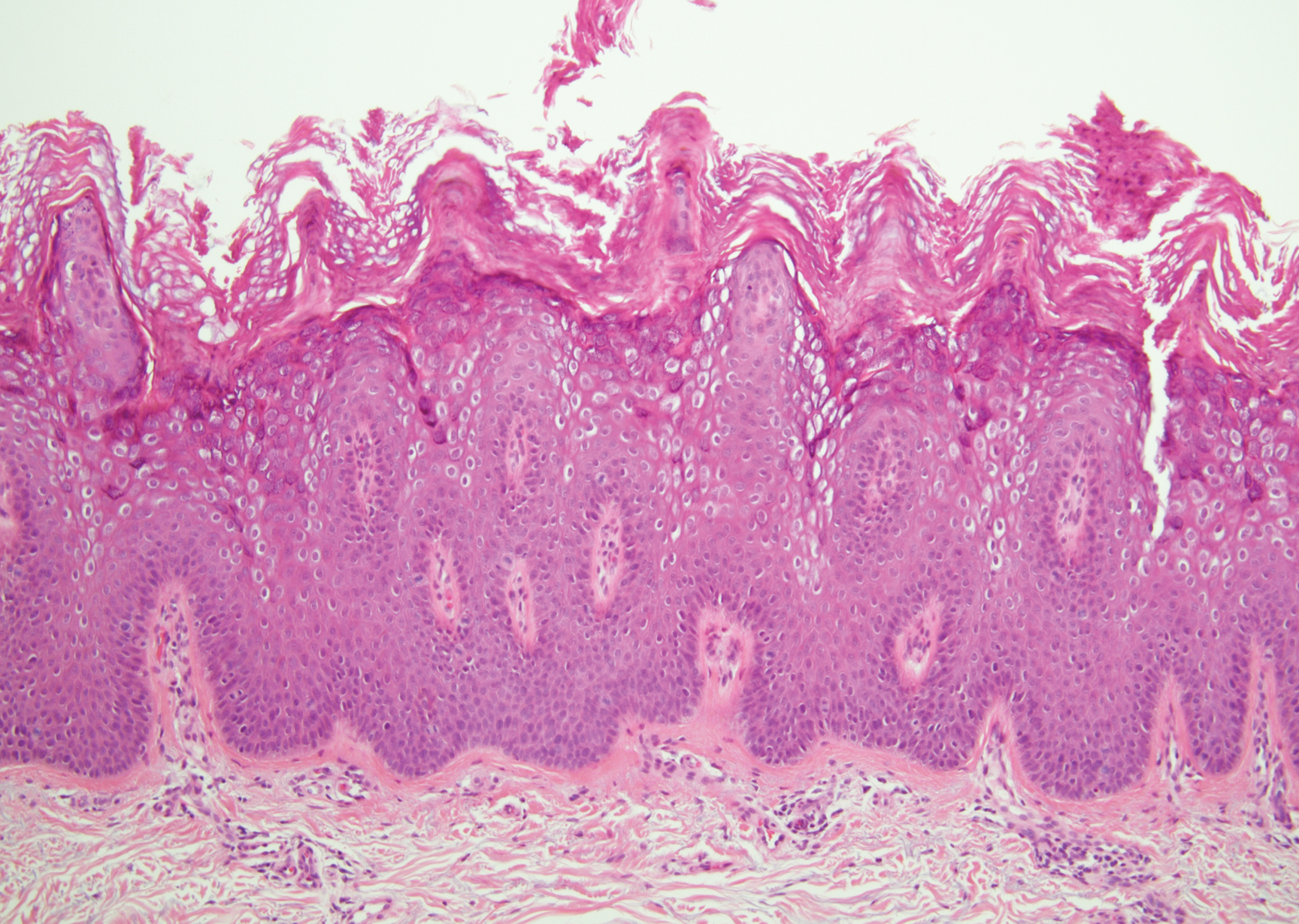

Juvenile colloid milium (JCM) is a rare condition that presents before puberty with discrete, yellow-brown, translucent papules predominantly located on the cheeks and nose and around the mouth. A gelatinous material can be expressed after puncturing a lesion.6 Gingival deposits and ligneous conjunctivitis also can be present. On histopathology, JCM shows degeneration of epidermal keratinocytes that form colloid bodies within the superficial dermis following apoptosis.6 Hematoxylin and eosin staining shows amorphous, fissured, pale pink deposits completely filling and expanding the superficial to mid dermis with clefting and no inflammation (Figure 3). Spindle-shaped fibroblasts may be seen within the lines of colloid fissuring and dispersed throughout the deposits.1 Histologically, JCM can be differentiated from EPP because deposits in EPP are distributed around and within superficial blood vessel walls, causing prominent vascular thickening not seen in JCM.6 The adult variant of colloid milium also can be distinguished from EPP by the presence of solar elastosis, which is absent in EPP due to a history of sun avoidance.3,7

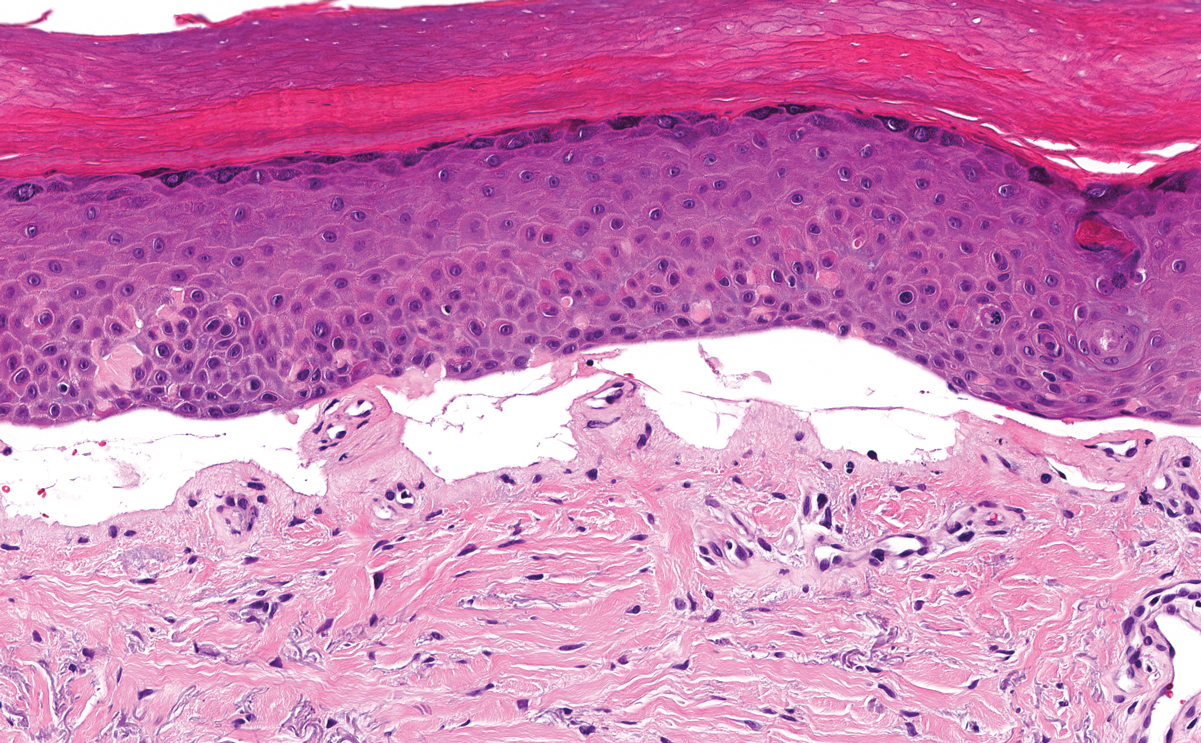

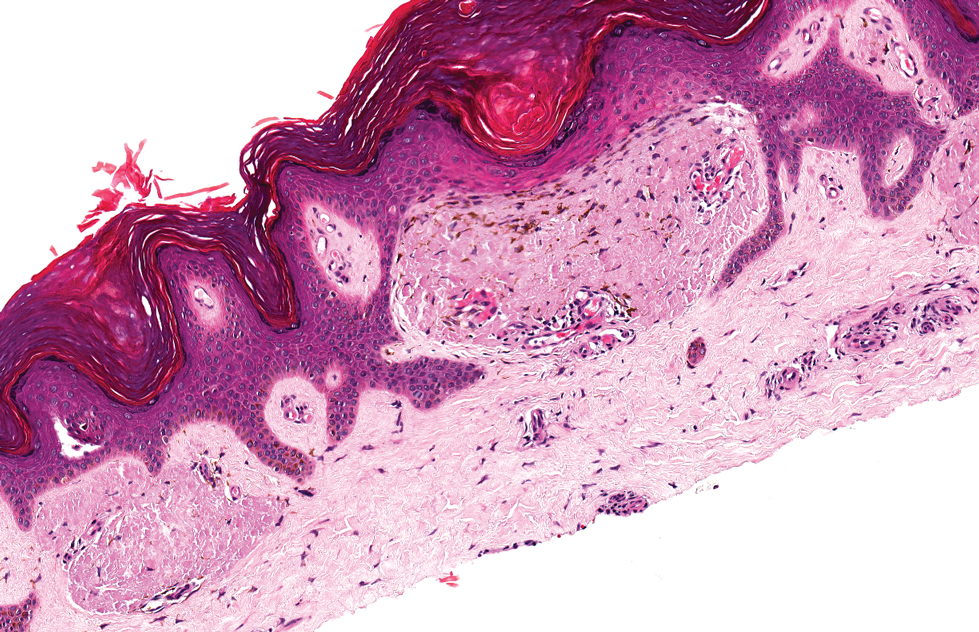

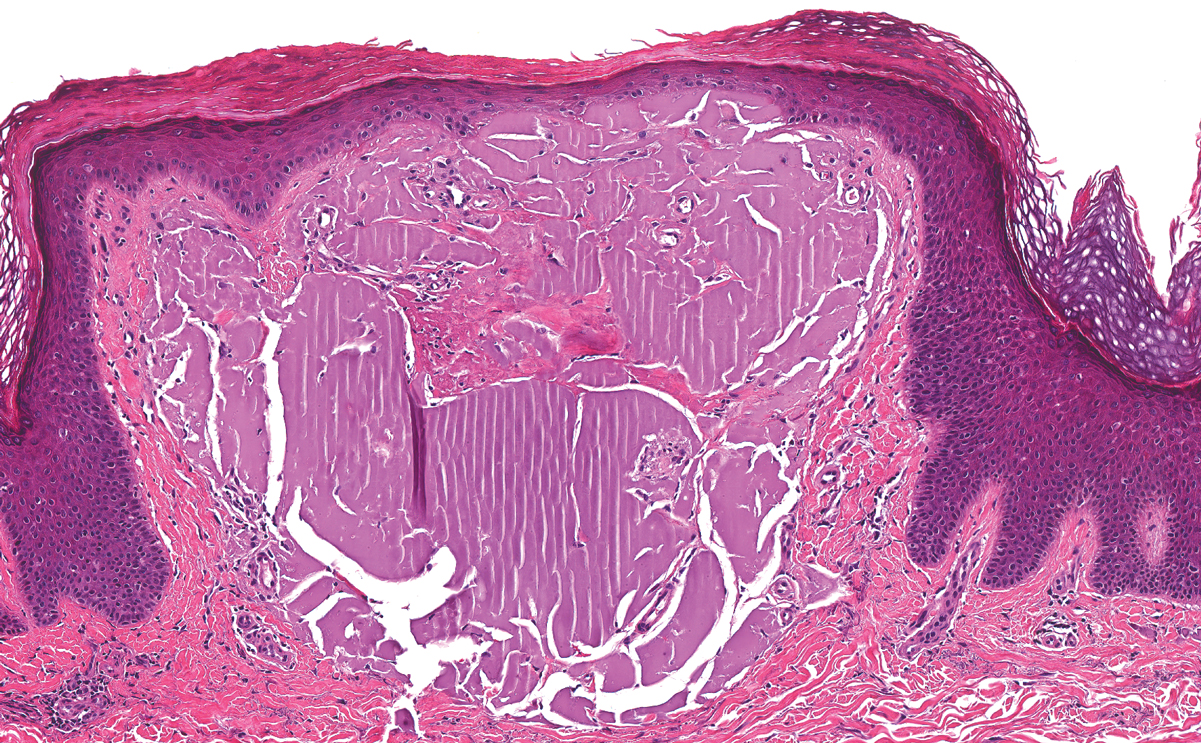

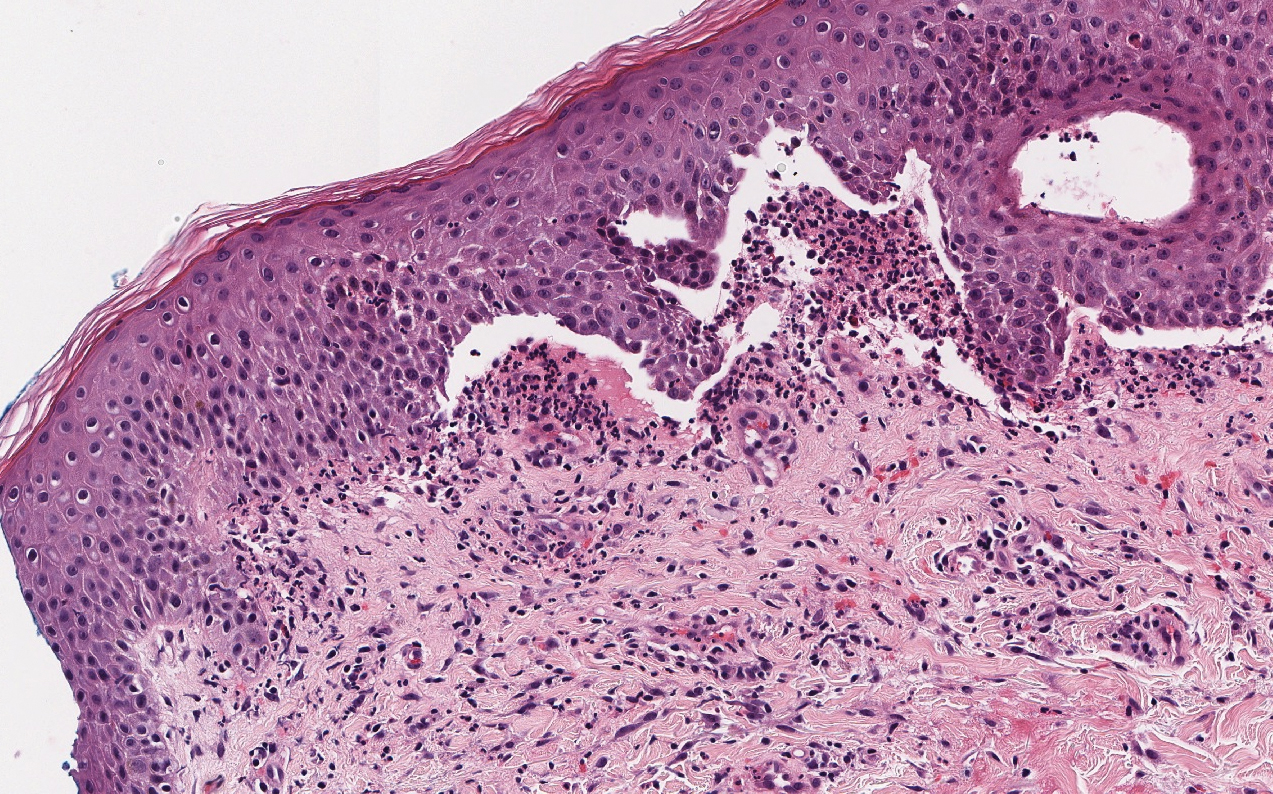

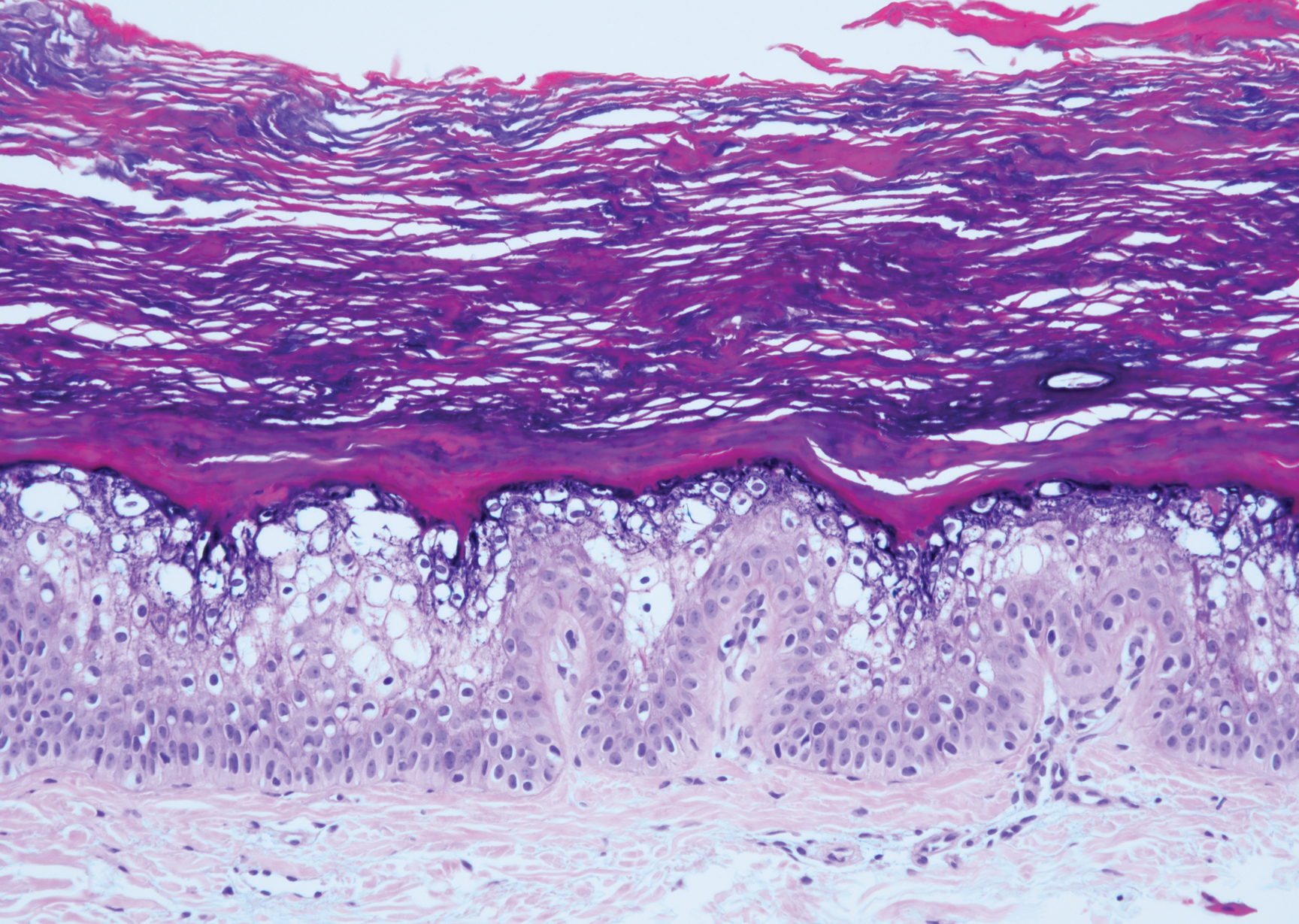

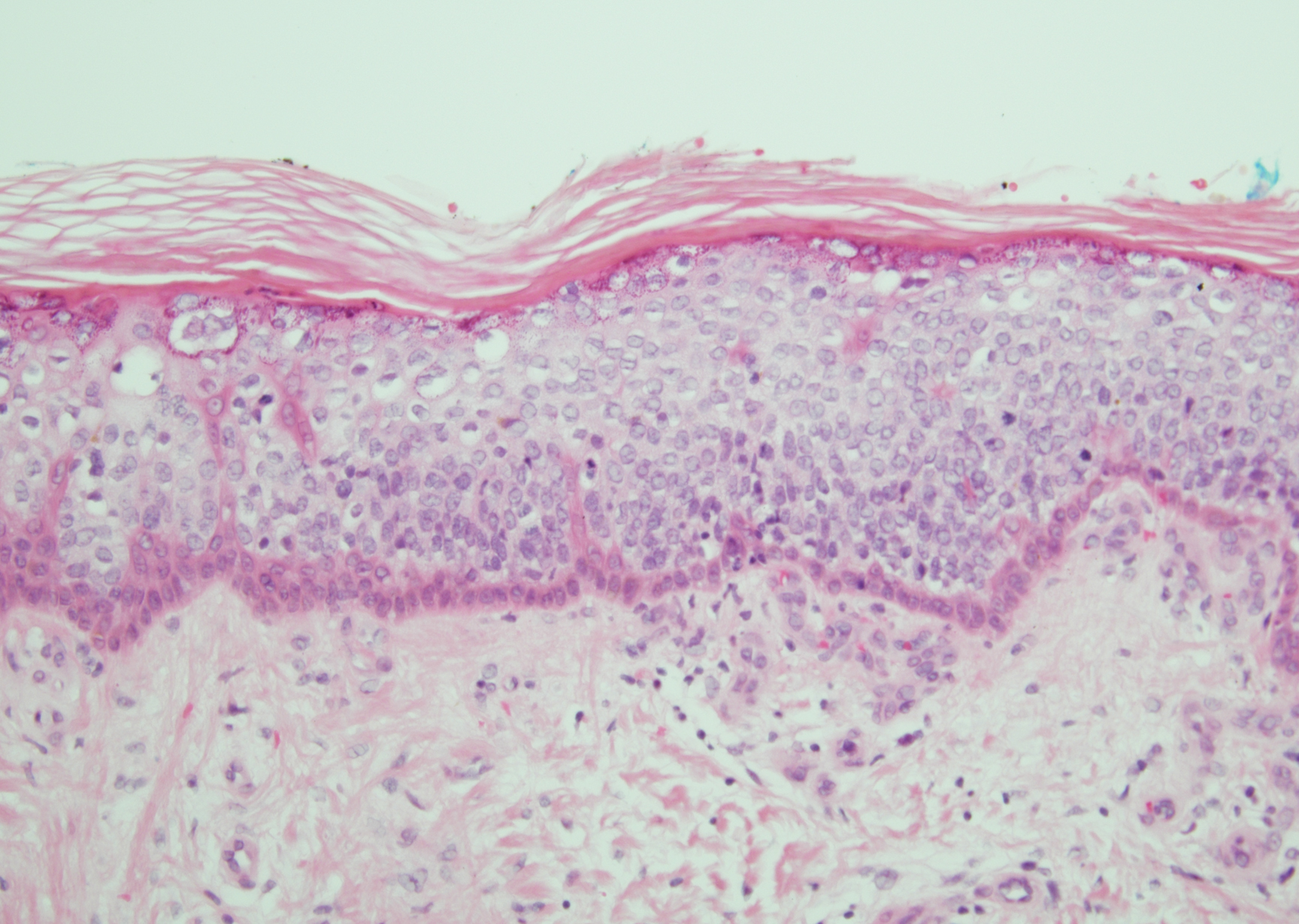

Lichen amyloidosis presents with highly pruritic, red-brown, hyperkeratotic papules that commonly are found on the anterior lower legs and extensor forearms.1 The calves, ankles, dorsal aspects of the feet, thighs, and trunk also may be affected. Excoriations, lichenification, and nodular prurigo-like lesions due to chronic scratching can be present.6 Lichen amyloidosis is characterized by large, pink, amorphous deposits in the papillary dermis with epidermal acanthosis, hypergranulosis, and hyperkeratosis (Figure 4).6 Perivascular deposits are not a feature of primary cutaneous localized amyloid lesions.6 The diagnosis can be confirmed with Congo red staining under polarized light, which classically demonstrates apple green birefringence.1 For cases of amyloid that are not detected by Congo red or are not clear-cut, direct immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry can be used as adjuncts for diagnosis. Amyloid deposits fluoresce positively for immunoglobulins or complements, particularly IgM and C3,8 and immunohistochemistry confirms the presence of keratin epitopes in deposits.9

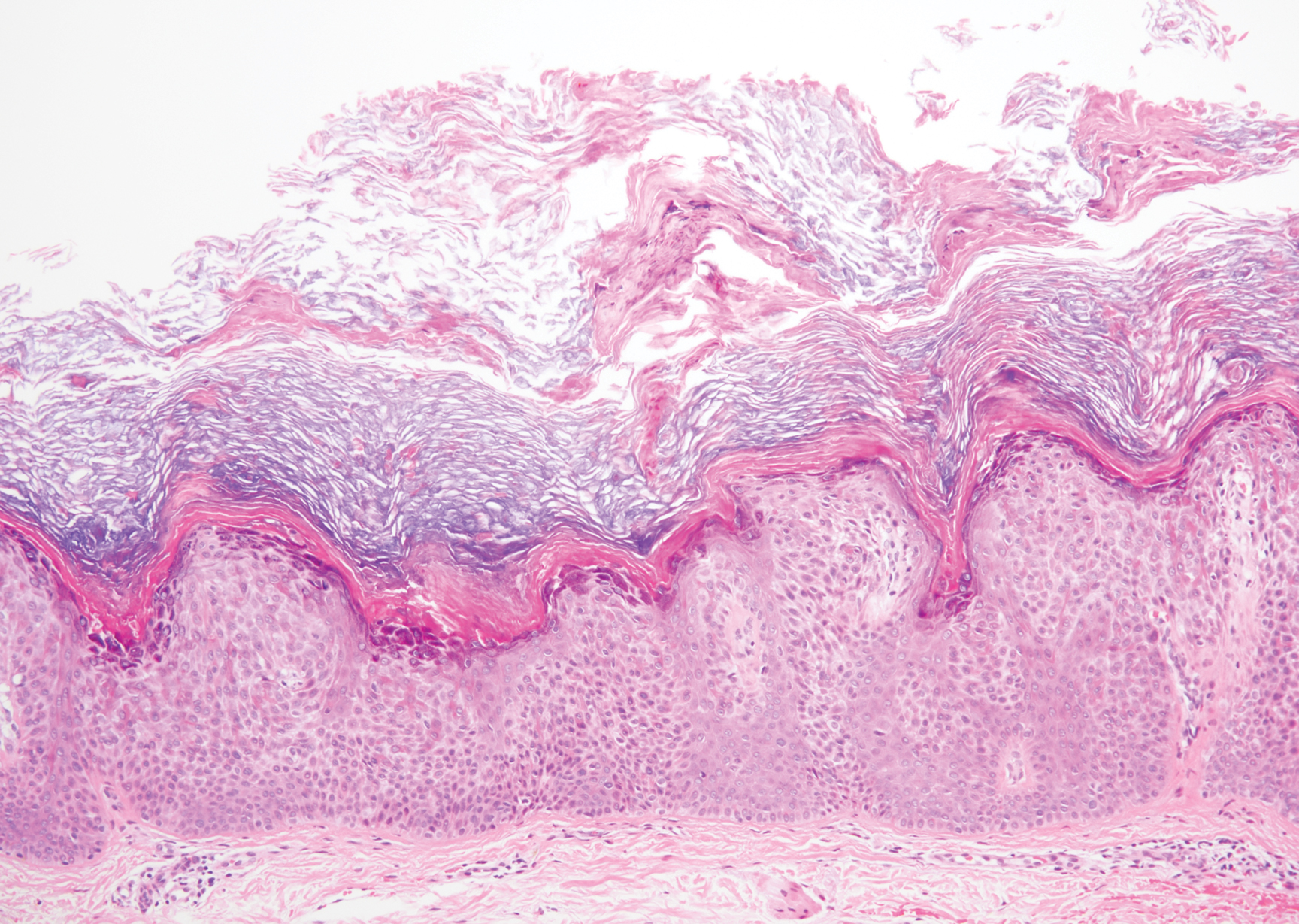

Porphyria cutanea tarda can appear histologically similar to EPP. Caterpillar bodies, or linearly arranged eosinophilic PAS-positive globules in the epidermis overlying subepidermal bullae, are a diagnostic histopathologic finding in both PCT and EPP but are seen in less than half of both cases.7,10 Compared to EPP, the perivascular deposits in PCT typically are less pronounced and limited to the vessel wall with smaller hyaline cuffs (Figure 5).7 Additionally, solar elastosis can be seen in PCT lesions but not in EPP, as patients with PCT tend to be older and have increased cumulative sun damage.

- Touart DM, Sau P. Cutaneous deposition diseases. part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(2, pt 1):149-171; quiz 172-144.

- Lim HW. Pathogenesis of photosensitivity in the cutaneous porphyrias. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:xvi-xvii.

- In: Alikhan A, Hocker TLH, eds. Review of Dermatology. China: Elsevier; 2017.

- Horner ME, Alikhan A, Tintle S, et al. Cutaneous porphyrias part I: epidemiology, pathogenesis, presentation, diagnosis, and histopathology. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:1464-1480.

- Michaels BD, Del Rosso JQ, Mobini N, et al. Erythropoietic protoporphyria: a case report and literature review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:44-48.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A, et al, eds. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Patterson JW. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier Limited; 2016.

- MacDonald DM, Black MM, Ramnarain N. Immunofluorescence studies in primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis. Br J Dermatol. 1977;96:635-641.

- Ortiz-Romero PL, Ballestin-Carcavilla C, Lopez-Estebaranz JL, et al. Clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical studies on lichen amyloidosis and macular amyloidosis. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1559-1560.

- Raso DS, Greene WB, Maize JC, et al. Caterpillar bodies of porphyria cutanea tarda ultrastructurally represent a unique arrangement of colloid and basement membrane bodies. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:24-29.

The Diagnosis: Erythropoietic Protoporphyria

Erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP) is an autosomal-recessive photodermatosis that results from loss of activity of ferrochelatase, the last enzyme in the heme biosynthetic pathway.1 Erythropoietic protoporphyria normally involves sun-exposed areas of the body. Skin that is exposed to sunlight develops intense burning and stinging pain followed by erythema, edema, crusting, and petechiae that develops into waxy scarring over time. In contrast to other porphyrias, blistering generally is not seen.2 Accurate diagnosis often can be delayed by a decade or more following symptom onset due to the prominence of subjective pain as the presenting sign.

The histologic appearance of EPP differs depending on the chronicity of lesions. Biopsies of acute lesions show vacuolization of epidermal cells with intercellular edema, vacuolization and cytolysis of endothelial cells in superficial blood vessels, and focal red blood cell extravasation.3,4 A largely neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrate can be present.5 Hyaline cuffing develops over time in and around vessels in the papillary and superficial reticular dermis with notable sparing of adnexal structures. The perivascular deposits are strongly periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) positive and diastase resistant (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence shows mainly IgG and some IgM, fibrinogen, and C3 outlining characteristic donut-shaped blood vessels in the papillary dermis.6 The prominent thickness of the perivascular hyaline material depositions and the absence of subepidermal blistering can help differentiate EPP from porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT) and pseudoporphyria.6,7 When the deposition is extensive and involves the surrounding dermis, EPP can mimic colloid milium. Additional histologic differential diagnoses of EPP include other dermal depositional diseases such as lipoid proteinosis and amyloidosis.

Lipoid proteinosis is an autosomal-recessive multisystem genodermatosis caused by mutations in extracellular matrix gene 1, ECM1. The first clinical sign can be a hoarse cry in infancy due to infiltration of vocal cords.3 Development of papulonodular lesions along the eyelids can result in a string-of-beads appearance called moniliform blepharosis, which is pathognomonic for lipoid proteinosis.6 With chronicity, the involved skin can become yellow, waxy, and thickened, particularly in the flexures or areas of trauma. Histologically, the dermis in lipoid proteinosis becomes diffusely thickened due to deposition of PAS-positive eosinophilic hyaline material that stains weakly with Congo red and thioflavin T.6 Early lesions demonstrate pale pink, hyalinelike thickening of the papillary dermal capillaries. Chronic lesions reveal an acanthotic epidermis, occasional papillomatosis with overlying hyperkeratosis, and a thickened dermis where diffuse thick bundles of pink hyaline deposits are oriented perpendicularly to the dermoepidermal junction.1,6 Lipoid proteinosis can be differentiated from EPP by the involvement of adnexal structures such as hair follicles, sebaceous glands, and arrector pili muscles (Figure 2), as opposed to EPP where adnexal structures are spared.1 Additionally, depositions in lipoid proteinosis are centered around both superficial and deep vessels with an onion skin-like pattern, while EPP involves mainly superficial vessels with more mild and focal hyalinization.

Juvenile colloid milium (JCM) is a rare condition that presents before puberty with discrete, yellow-brown, translucent papules predominantly located on the cheeks and nose and around the mouth. A gelatinous material can be expressed after puncturing a lesion.6 Gingival deposits and ligneous conjunctivitis also can be present. On histopathology, JCM shows degeneration of epidermal keratinocytes that form colloid bodies within the superficial dermis following apoptosis.6 Hematoxylin and eosin staining shows amorphous, fissured, pale pink deposits completely filling and expanding the superficial to mid dermis with clefting and no inflammation (Figure 3). Spindle-shaped fibroblasts may be seen within the lines of colloid fissuring and dispersed throughout the deposits.1 Histologically, JCM can be differentiated from EPP because deposits in EPP are distributed around and within superficial blood vessel walls, causing prominent vascular thickening not seen in JCM.6 The adult variant of colloid milium also can be distinguished from EPP by the presence of solar elastosis, which is absent in EPP due to a history of sun avoidance.3,7

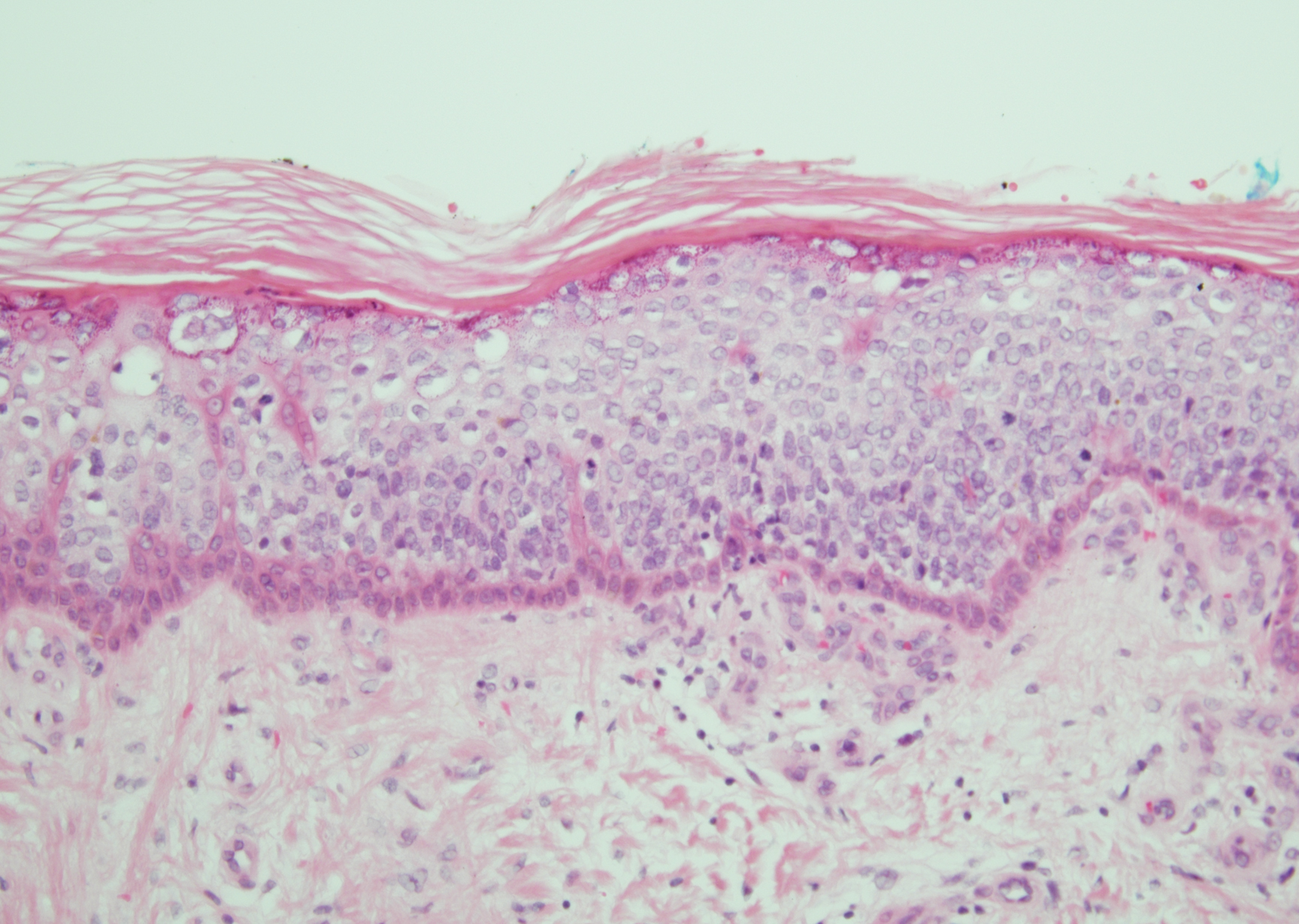

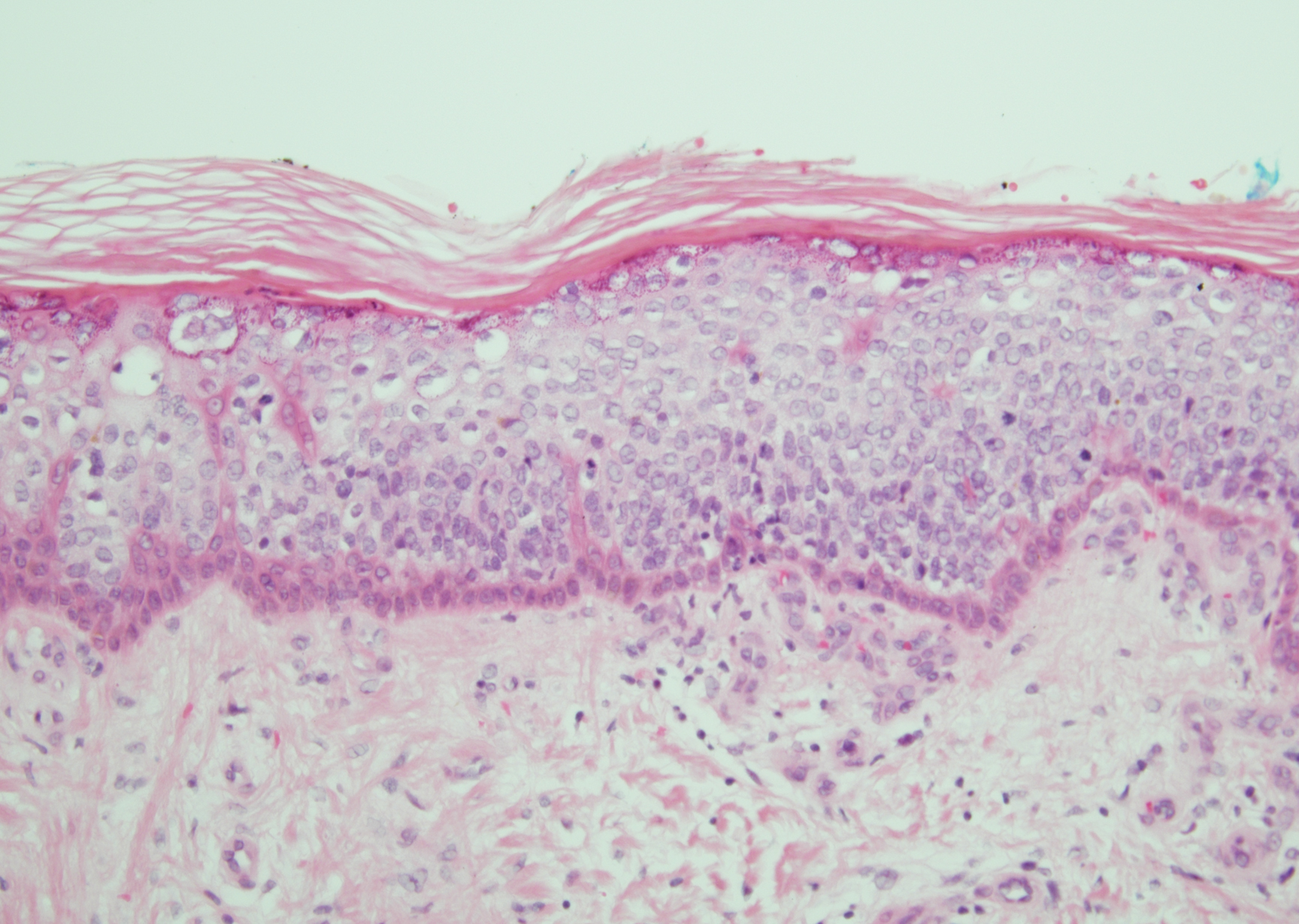

Lichen amyloidosis presents with highly pruritic, red-brown, hyperkeratotic papules that commonly are found on the anterior lower legs and extensor forearms.1 The calves, ankles, dorsal aspects of the feet, thighs, and trunk also may be affected. Excoriations, lichenification, and nodular prurigo-like lesions due to chronic scratching can be present.6 Lichen amyloidosis is characterized by large, pink, amorphous deposits in the papillary dermis with epidermal acanthosis, hypergranulosis, and hyperkeratosis (Figure 4).6 Perivascular deposits are not a feature of primary cutaneous localized amyloid lesions.6 The diagnosis can be confirmed with Congo red staining under polarized light, which classically demonstrates apple green birefringence.1 For cases of amyloid that are not detected by Congo red or are not clear-cut, direct immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry can be used as adjuncts for diagnosis. Amyloid deposits fluoresce positively for immunoglobulins or complements, particularly IgM and C3,8 and immunohistochemistry confirms the presence of keratin epitopes in deposits.9

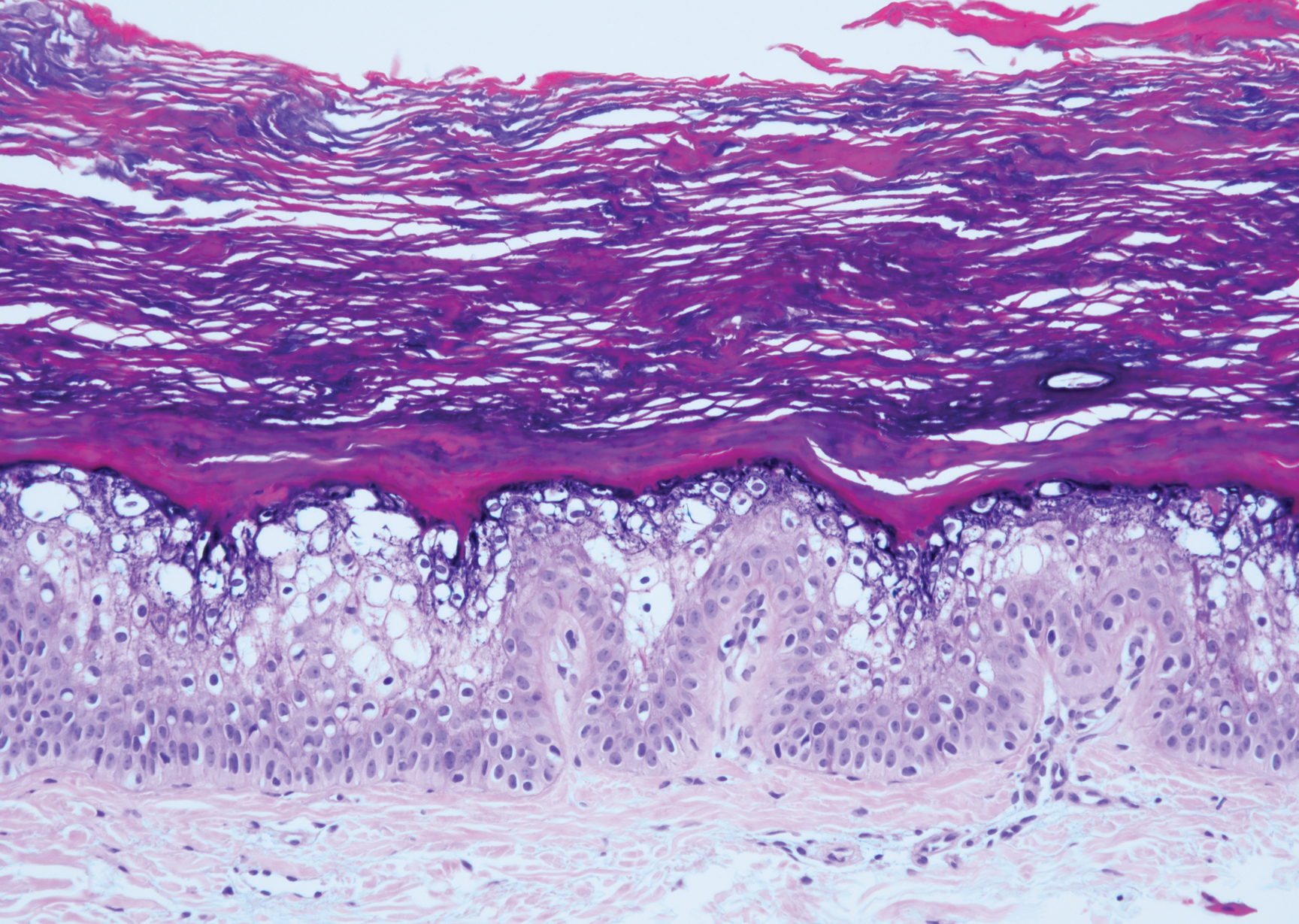

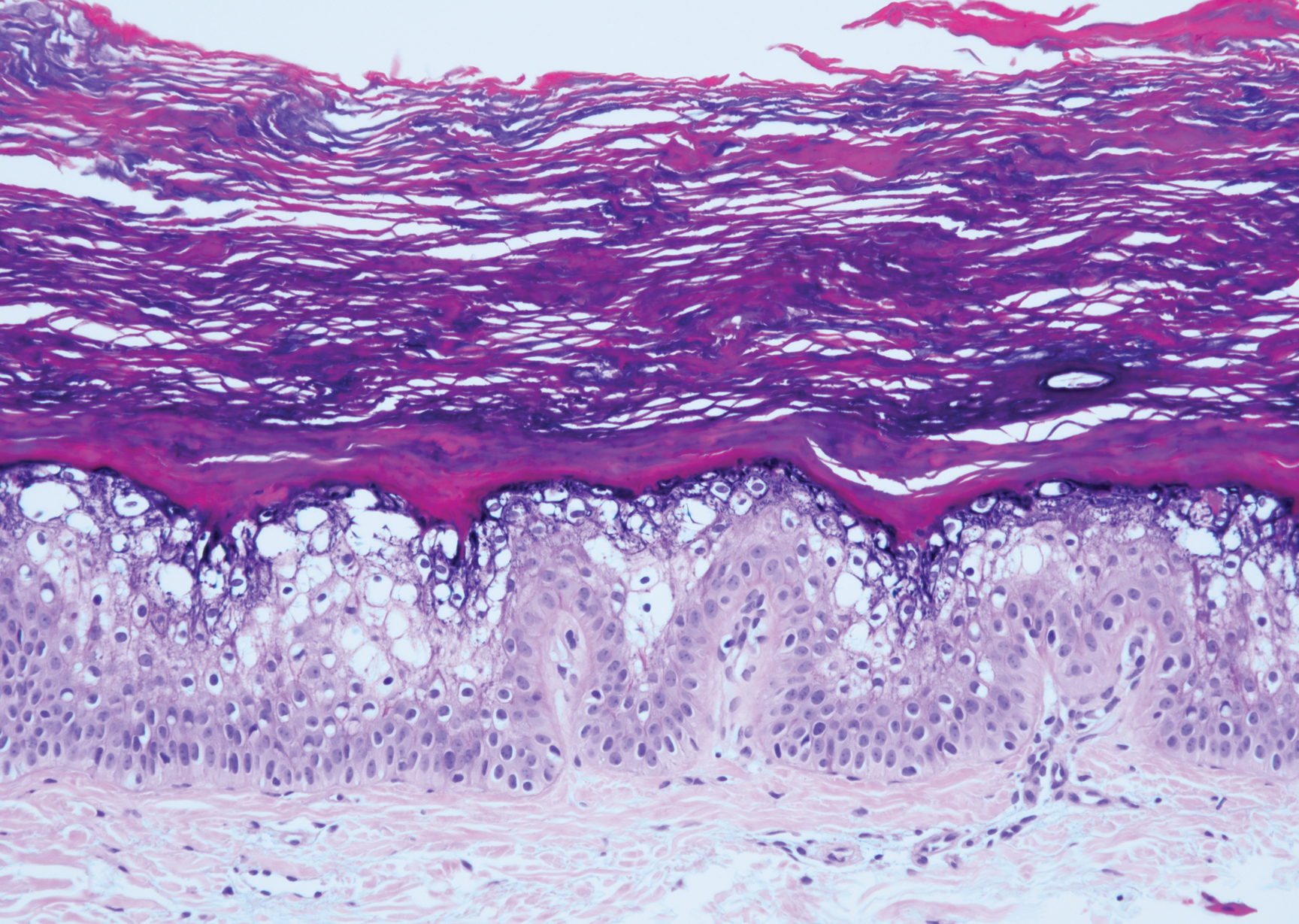

Porphyria cutanea tarda can appear histologically similar to EPP. Caterpillar bodies, or linearly arranged eosinophilic PAS-positive globules in the epidermis overlying subepidermal bullae, are a diagnostic histopathologic finding in both PCT and EPP but are seen in less than half of both cases.7,10 Compared to EPP, the perivascular deposits in PCT typically are less pronounced and limited to the vessel wall with smaller hyaline cuffs (Figure 5).7 Additionally, solar elastosis can be seen in PCT lesions but not in EPP, as patients with PCT tend to be older and have increased cumulative sun damage.

The Diagnosis: Erythropoietic Protoporphyria

Erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP) is an autosomal-recessive photodermatosis that results from loss of activity of ferrochelatase, the last enzyme in the heme biosynthetic pathway.1 Erythropoietic protoporphyria normally involves sun-exposed areas of the body. Skin that is exposed to sunlight develops intense burning and stinging pain followed by erythema, edema, crusting, and petechiae that develops into waxy scarring over time. In contrast to other porphyrias, blistering generally is not seen.2 Accurate diagnosis often can be delayed by a decade or more following symptom onset due to the prominence of subjective pain as the presenting sign.

The histologic appearance of EPP differs depending on the chronicity of lesions. Biopsies of acute lesions show vacuolization of epidermal cells with intercellular edema, vacuolization and cytolysis of endothelial cells in superficial blood vessels, and focal red blood cell extravasation.3,4 A largely neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrate can be present.5 Hyaline cuffing develops over time in and around vessels in the papillary and superficial reticular dermis with notable sparing of adnexal structures. The perivascular deposits are strongly periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) positive and diastase resistant (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence shows mainly IgG and some IgM, fibrinogen, and C3 outlining characteristic donut-shaped blood vessels in the papillary dermis.6 The prominent thickness of the perivascular hyaline material depositions and the absence of subepidermal blistering can help differentiate EPP from porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT) and pseudoporphyria.6,7 When the deposition is extensive and involves the surrounding dermis, EPP can mimic colloid milium. Additional histologic differential diagnoses of EPP include other dermal depositional diseases such as lipoid proteinosis and amyloidosis.

Lipoid proteinosis is an autosomal-recessive multisystem genodermatosis caused by mutations in extracellular matrix gene 1, ECM1. The first clinical sign can be a hoarse cry in infancy due to infiltration of vocal cords.3 Development of papulonodular lesions along the eyelids can result in a string-of-beads appearance called moniliform blepharosis, which is pathognomonic for lipoid proteinosis.6 With chronicity, the involved skin can become yellow, waxy, and thickened, particularly in the flexures or areas of trauma. Histologically, the dermis in lipoid proteinosis becomes diffusely thickened due to deposition of PAS-positive eosinophilic hyaline material that stains weakly with Congo red and thioflavin T.6 Early lesions demonstrate pale pink, hyalinelike thickening of the papillary dermal capillaries. Chronic lesions reveal an acanthotic epidermis, occasional papillomatosis with overlying hyperkeratosis, and a thickened dermis where diffuse thick bundles of pink hyaline deposits are oriented perpendicularly to the dermoepidermal junction.1,6 Lipoid proteinosis can be differentiated from EPP by the involvement of adnexal structures such as hair follicles, sebaceous glands, and arrector pili muscles (Figure 2), as opposed to EPP where adnexal structures are spared.1 Additionally, depositions in lipoid proteinosis are centered around both superficial and deep vessels with an onion skin-like pattern, while EPP involves mainly superficial vessels with more mild and focal hyalinization.

Juvenile colloid milium (JCM) is a rare condition that presents before puberty with discrete, yellow-brown, translucent papules predominantly located on the cheeks and nose and around the mouth. A gelatinous material can be expressed after puncturing a lesion.6 Gingival deposits and ligneous conjunctivitis also can be present. On histopathology, JCM shows degeneration of epidermal keratinocytes that form colloid bodies within the superficial dermis following apoptosis.6 Hematoxylin and eosin staining shows amorphous, fissured, pale pink deposits completely filling and expanding the superficial to mid dermis with clefting and no inflammation (Figure 3). Spindle-shaped fibroblasts may be seen within the lines of colloid fissuring and dispersed throughout the deposits.1 Histologically, JCM can be differentiated from EPP because deposits in EPP are distributed around and within superficial blood vessel walls, causing prominent vascular thickening not seen in JCM.6 The adult variant of colloid milium also can be distinguished from EPP by the presence of solar elastosis, which is absent in EPP due to a history of sun avoidance.3,7

Lichen amyloidosis presents with highly pruritic, red-brown, hyperkeratotic papules that commonly are found on the anterior lower legs and extensor forearms.1 The calves, ankles, dorsal aspects of the feet, thighs, and trunk also may be affected. Excoriations, lichenification, and nodular prurigo-like lesions due to chronic scratching can be present.6 Lichen amyloidosis is characterized by large, pink, amorphous deposits in the papillary dermis with epidermal acanthosis, hypergranulosis, and hyperkeratosis (Figure 4).6 Perivascular deposits are not a feature of primary cutaneous localized amyloid lesions.6 The diagnosis can be confirmed with Congo red staining under polarized light, which classically demonstrates apple green birefringence.1 For cases of amyloid that are not detected by Congo red or are not clear-cut, direct immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry can be used as adjuncts for diagnosis. Amyloid deposits fluoresce positively for immunoglobulins or complements, particularly IgM and C3,8 and immunohistochemistry confirms the presence of keratin epitopes in deposits.9

Porphyria cutanea tarda can appear histologically similar to EPP. Caterpillar bodies, or linearly arranged eosinophilic PAS-positive globules in the epidermis overlying subepidermal bullae, are a diagnostic histopathologic finding in both PCT and EPP but are seen in less than half of both cases.7,10 Compared to EPP, the perivascular deposits in PCT typically are less pronounced and limited to the vessel wall with smaller hyaline cuffs (Figure 5).7 Additionally, solar elastosis can be seen in PCT lesions but not in EPP, as patients with PCT tend to be older and have increased cumulative sun damage.

- Touart DM, Sau P. Cutaneous deposition diseases. part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(2, pt 1):149-171; quiz 172-144.

- Lim HW. Pathogenesis of photosensitivity in the cutaneous porphyrias. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:xvi-xvii.

- In: Alikhan A, Hocker TLH, eds. Review of Dermatology. China: Elsevier; 2017.

- Horner ME, Alikhan A, Tintle S, et al. Cutaneous porphyrias part I: epidemiology, pathogenesis, presentation, diagnosis, and histopathology. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:1464-1480.

- Michaels BD, Del Rosso JQ, Mobini N, et al. Erythropoietic protoporphyria: a case report and literature review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:44-48.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A, et al, eds. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Patterson JW. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier Limited; 2016.

- MacDonald DM, Black MM, Ramnarain N. Immunofluorescence studies in primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis. Br J Dermatol. 1977;96:635-641.

- Ortiz-Romero PL, Ballestin-Carcavilla C, Lopez-Estebaranz JL, et al. Clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical studies on lichen amyloidosis and macular amyloidosis. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1559-1560.

- Raso DS, Greene WB, Maize JC, et al. Caterpillar bodies of porphyria cutanea tarda ultrastructurally represent a unique arrangement of colloid and basement membrane bodies. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:24-29.

- Touart DM, Sau P. Cutaneous deposition diseases. part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(2, pt 1):149-171; quiz 172-144.

- Lim HW. Pathogenesis of photosensitivity in the cutaneous porphyrias. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:xvi-xvii.

- In: Alikhan A, Hocker TLH, eds. Review of Dermatology. China: Elsevier; 2017.

- Horner ME, Alikhan A, Tintle S, et al. Cutaneous porphyrias part I: epidemiology, pathogenesis, presentation, diagnosis, and histopathology. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:1464-1480.

- Michaels BD, Del Rosso JQ, Mobini N, et al. Erythropoietic protoporphyria: a case report and literature review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:44-48.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A, et al, eds. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Patterson JW. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier Limited; 2016.

- MacDonald DM, Black MM, Ramnarain N. Immunofluorescence studies in primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis. Br J Dermatol. 1977;96:635-641.

- Ortiz-Romero PL, Ballestin-Carcavilla C, Lopez-Estebaranz JL, et al. Clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical studies on lichen amyloidosis and macular amyloidosis. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1559-1560.

- Raso DS, Greene WB, Maize JC, et al. Caterpillar bodies of porphyria cutanea tarda ultrastructurally represent a unique arrangement of colloid and basement membrane bodies. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:24-29.

A 9-year-old girl presented with unexplained burning pain on the face, hands, and feet of 3 years' duration. Physical examination showed depressed shiny scars and crusted erosions on the dorsal aspect of the nose, arms, hands, and fingers. A 3-mm punch biopsy specimen was obtained from the right hand.

Woody Erythematous Induration on the Posterior Neck

The Diagnosis: Scleredema Diabeticorum

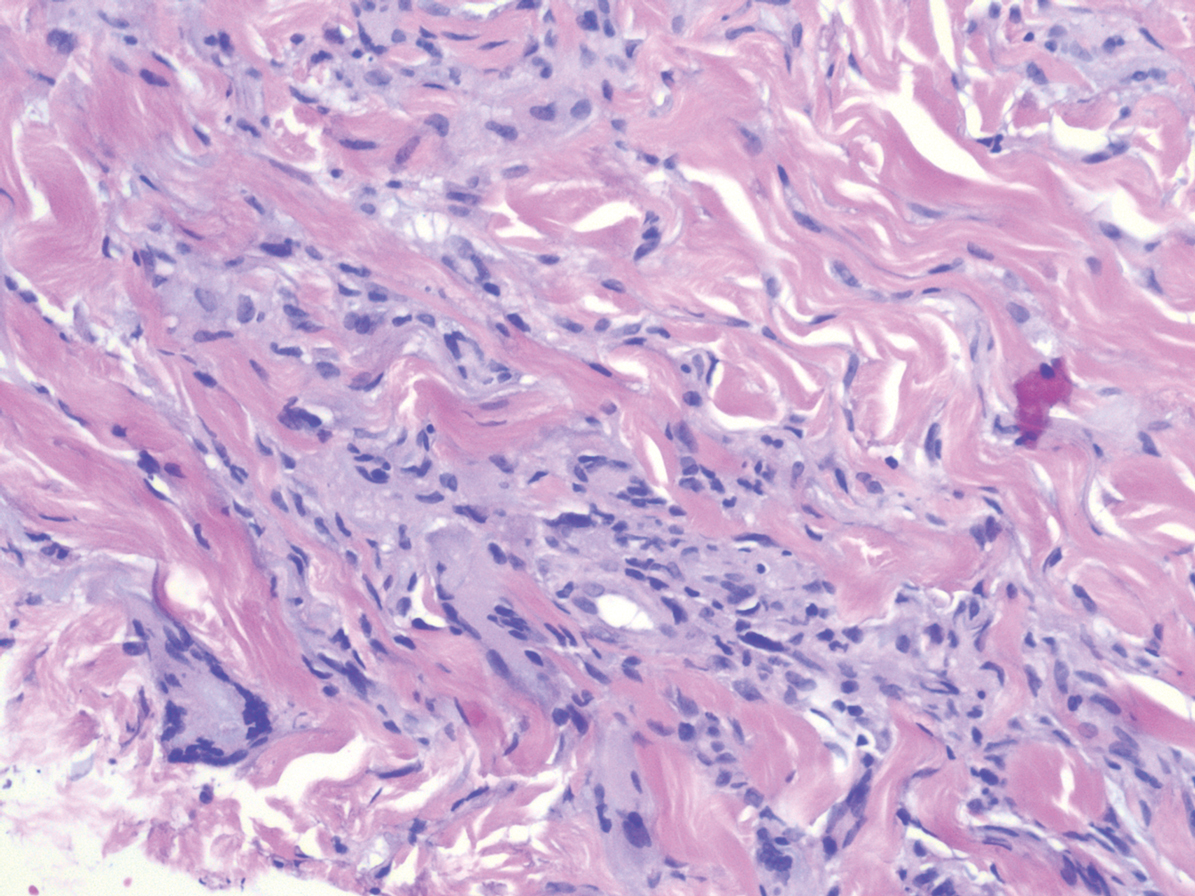

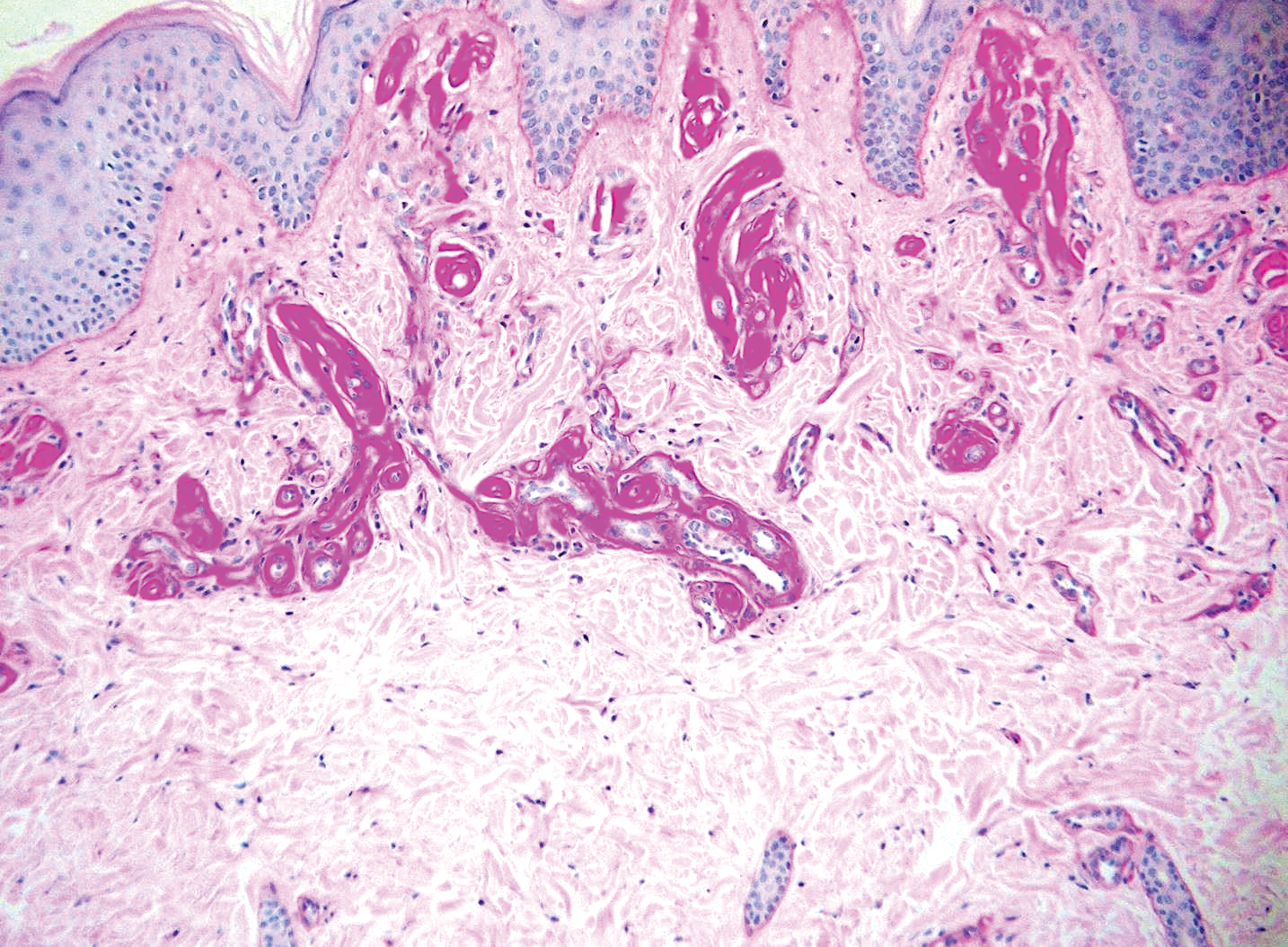

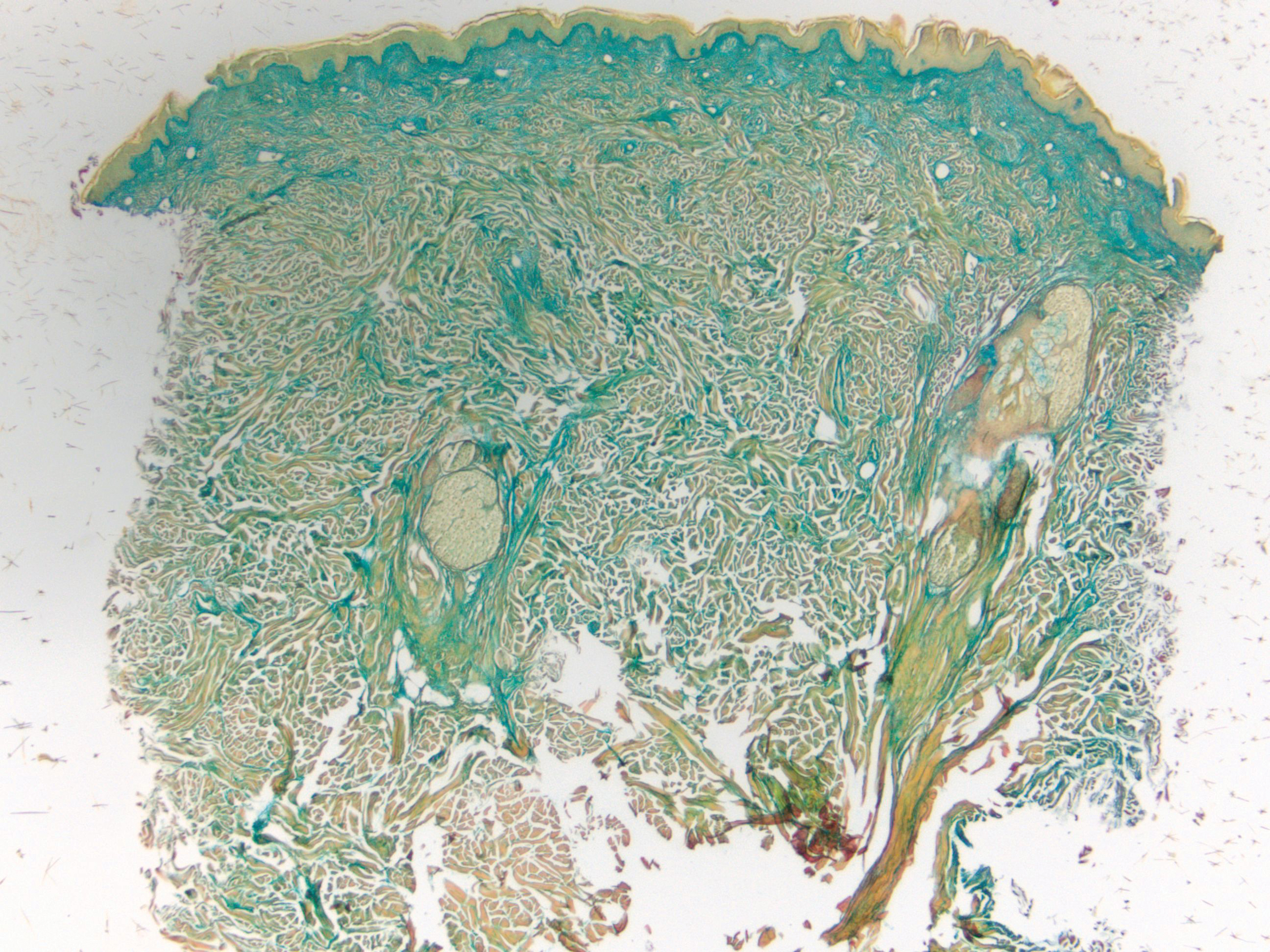

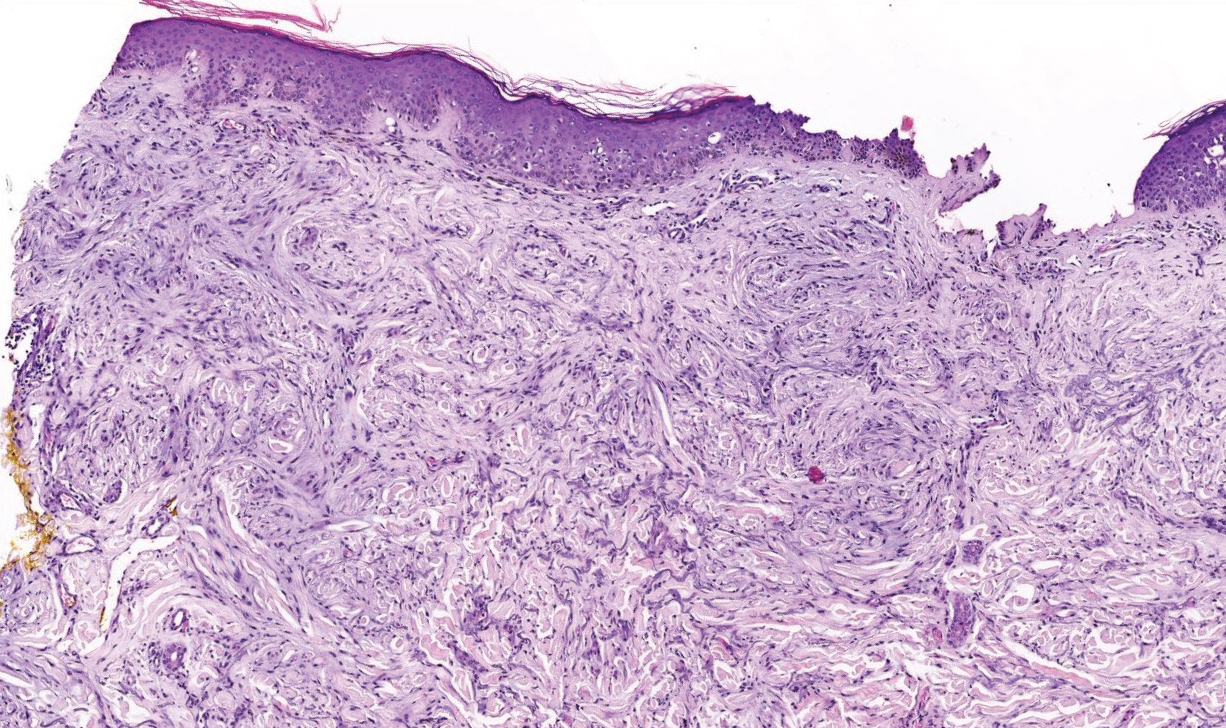

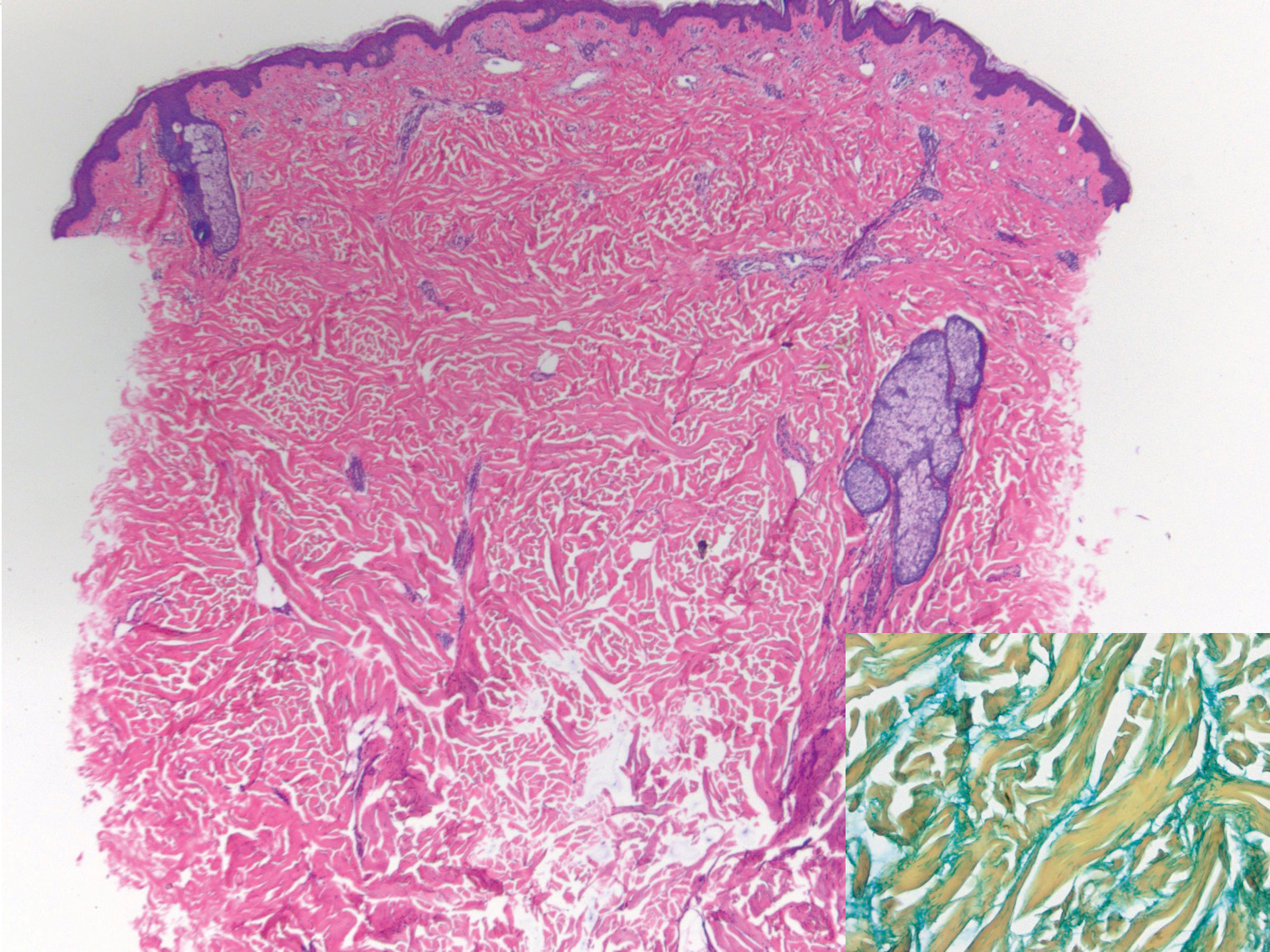

Histologically, scleredema is characterized by mucin deposition between collagen bundles in the deep dermis. Clinically, it is characterized by a progressive indurated plaque with associated stiffness of the involved area. It most commonly presents on the posterior aspect of the neck, though it can extend to involve the shoulders and upper torso.1 Scleredema is divided into 3 subtypes based on clinical associations. Type 1 often is preceded by an infection, most commonly group A Streptococcus. This type occurs acutely and often resolves completely over a few months.2 Type 2, which has progressive onset, is associated with monoclonal gammopathy.3 Type 3 is the most common type and is associated with diabetes mellitus. A study of 484 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus demonstrated a prevalence of 2.5%.4 Although the exact pathogenesis has not been defined, it is hypothesized that irreversible glycosylation of collagen and alterations in collagenase activity may lead to accumulation of collagen and mucin in the dermis.5 Similar to type 2, type 3 scleredema appears subtly, progresses slowly, and tends to be chronic.1,6 Scleredema is characterized by marked dermal thickening and enlarged collagen bundles separated by mucin deposition (Figure 1). Fibroblast proliferation is characteristically absent.1

Clinically, tumid lupus erythematosus presents with erythematous edematous plaques on sun-exposed areas.7 Pretibial myxedema (PM) classically is associated with Graves disease; however, it can present in association with other types of thyroid dysfunction. Classically, PM presents on the pretibial regions as well-demarcated erythematous or hyperpigmented plaques.8 Similar to scleredema, histologic examination of tumid lupus erythematosus and PM reveals mucin deposition. Tumid lupus erythematosus also may demonstrate periadnexal and perivascular lymphocytic inflammation (Figure 2).7 The collagen bundles present in PM often are thin in comparison to scleredema (Figure 3).8

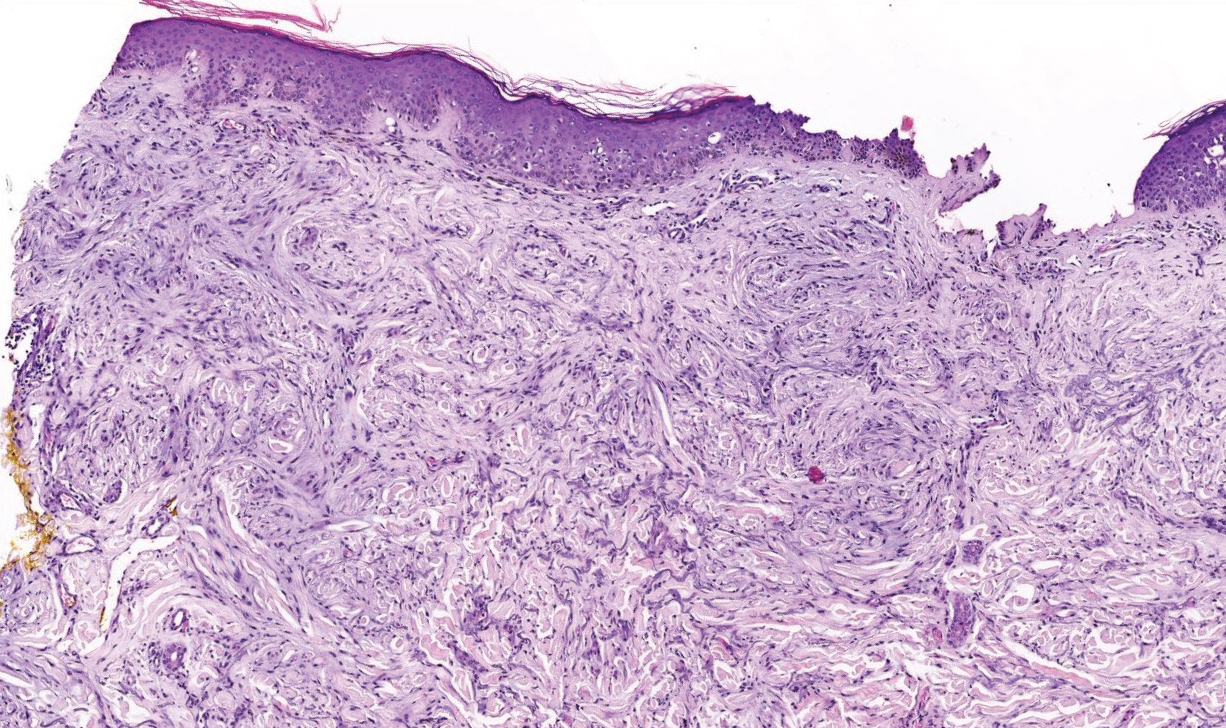

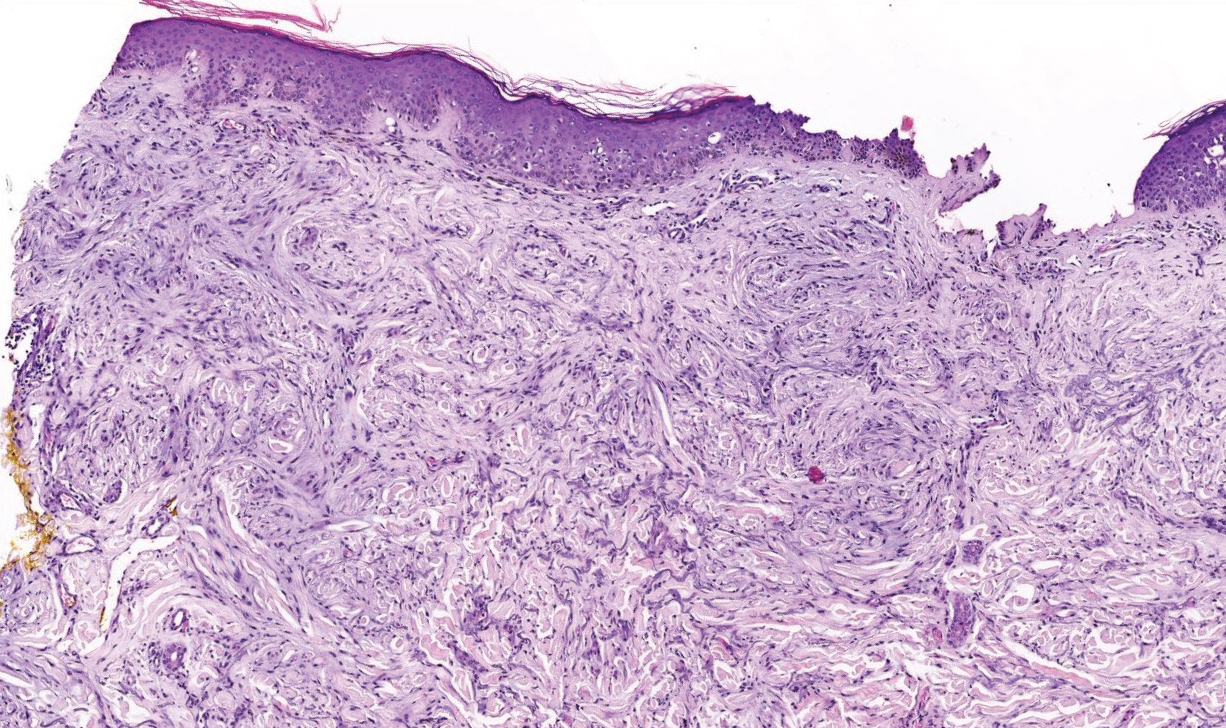

Scleroderma also presents with skin induration, erythema, and stiffening. However, unlike scleredema, scleroderma commonly involves the fingers, toes, and face. It presents with symptoms of Raynaud phenomenon, painful digital nonpitting edema, perioral skin tightening, mucocutaneous telangiectasia, and calcinosis cutis. Scleroderma also can involve organs such as the lungs, heart, kidneys, and gastrointestinal tract.9 Histologically, scleroderma is characterized by a compact dermis with closely packed collagen bundles. Other features of scleroderma can include perivascular mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltration, progressive atrophy of intradermal and perieccrine fat, and fibrosis (Figure 4).10

Scleromyxedema, also called papular mucinosis, is primary dermal mucinosis that often presents with waxy, dome-shaped papules that may coalesce into plaques. Similar to scleredema, scleromyxedema shows increased mucin deposition. However, scleromyxedema commonly is associated with fibroblast proliferation, which is characteristically absent in scleredema (Figure 5).11

- Beers WH, Ince A, Moore TL. Scleredema adultorum of Buschke: a case report and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35:355-359.

- Cron RQ, Swetter SM. Scleredema revisited. a poststreptococcal complication. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1994;33:606-610.

- Kövary PM, Vakilzadeh F, Macher E, et al. Monoclonal gammopathy in scleredema. observations in three cases. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:536-539.

- Cole GW, Headley J, Skowsky R. Scleredema diabeticorum: a common and distinct cutaneous manifestation of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1983;6:189-192.

- Namas R, Ashraf A. Scleredema of Buschke. Eur J Rheumatol. 2016;3:191-192.

- Knobler R, Moinzadeh P, Hunzelmann N, et al. European Dermatology Forum S1-guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of sclerosing diseases of the skin, part 2: scleromyxedema, scleredema and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:1581-1594.

- Kuhn A, Richter-Hintz D, Oslislo C, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus--a neglected subset of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: report of 40 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1033-1041.

- Fatourechi V. Pretibial myxedema: pathophysiology and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:295-309.

- van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, et al. 2013 Classification Criteria for Systemic Sclerosis: An American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism Collaborative Initiative. 2013;65:2737-2747.

- Ferreli C, Gasparini G, Parodi A, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of scleroderma and scleroderma-like disorders: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2017;53:306-336.

- Rongioletti F, Merlo G, Cinotti E, et al. Scleromyxedema: a multicenter study of characteristics, comorbidities, course, and therapy in 30 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:66-72.

The Diagnosis: Scleredema Diabeticorum

Histologically, scleredema is characterized by mucin deposition between collagen bundles in the deep dermis. Clinically, it is characterized by a progressive indurated plaque with associated stiffness of the involved area. It most commonly presents on the posterior aspect of the neck, though it can extend to involve the shoulders and upper torso.1 Scleredema is divided into 3 subtypes based on clinical associations. Type 1 often is preceded by an infection, most commonly group A Streptococcus. This type occurs acutely and often resolves completely over a few months.2 Type 2, which has progressive onset, is associated with monoclonal gammopathy.3 Type 3 is the most common type and is associated with diabetes mellitus. A study of 484 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus demonstrated a prevalence of 2.5%.4 Although the exact pathogenesis has not been defined, it is hypothesized that irreversible glycosylation of collagen and alterations in collagenase activity may lead to accumulation of collagen and mucin in the dermis.5 Similar to type 2, type 3 scleredema appears subtly, progresses slowly, and tends to be chronic.1,6 Scleredema is characterized by marked dermal thickening and enlarged collagen bundles separated by mucin deposition (Figure 1). Fibroblast proliferation is characteristically absent.1

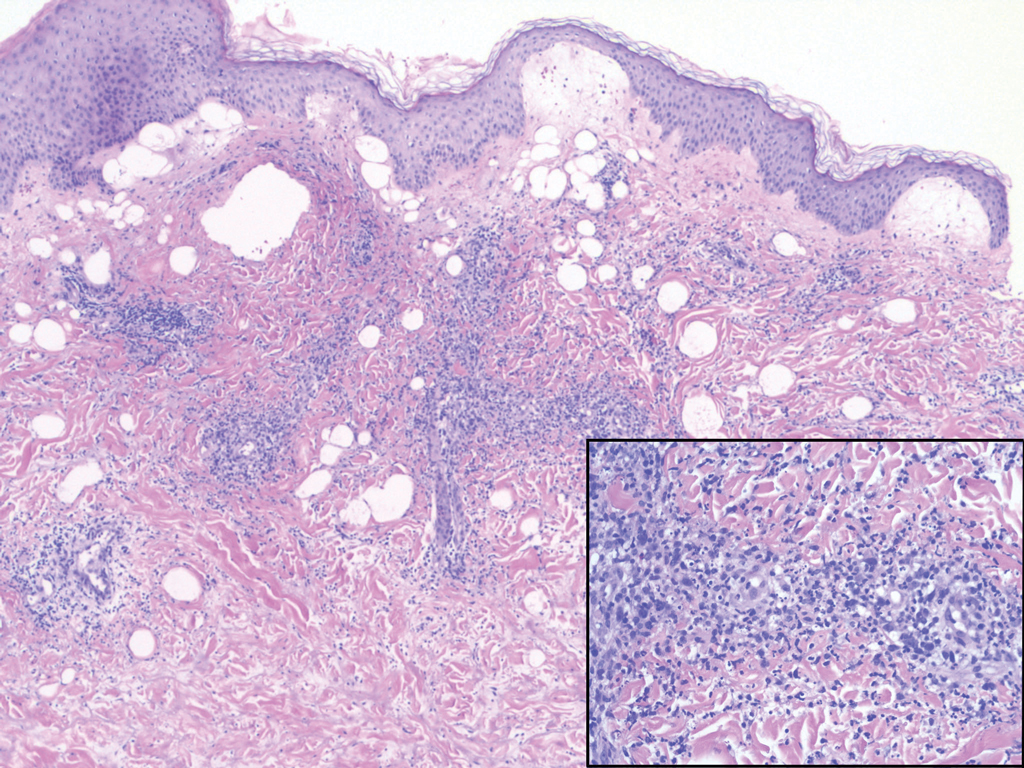

Clinically, tumid lupus erythematosus presents with erythematous edematous plaques on sun-exposed areas.7 Pretibial myxedema (PM) classically is associated with Graves disease; however, it can present in association with other types of thyroid dysfunction. Classically, PM presents on the pretibial regions as well-demarcated erythematous or hyperpigmented plaques.8 Similar to scleredema, histologic examination of tumid lupus erythematosus and PM reveals mucin deposition. Tumid lupus erythematosus also may demonstrate periadnexal and perivascular lymphocytic inflammation (Figure 2).7 The collagen bundles present in PM often are thin in comparison to scleredema (Figure 3).8

Scleroderma also presents with skin induration, erythema, and stiffening. However, unlike scleredema, scleroderma commonly involves the fingers, toes, and face. It presents with symptoms of Raynaud phenomenon, painful digital nonpitting edema, perioral skin tightening, mucocutaneous telangiectasia, and calcinosis cutis. Scleroderma also can involve organs such as the lungs, heart, kidneys, and gastrointestinal tract.9 Histologically, scleroderma is characterized by a compact dermis with closely packed collagen bundles. Other features of scleroderma can include perivascular mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltration, progressive atrophy of intradermal and perieccrine fat, and fibrosis (Figure 4).10

Scleromyxedema, also called papular mucinosis, is primary dermal mucinosis that often presents with waxy, dome-shaped papules that may coalesce into plaques. Similar to scleredema, scleromyxedema shows increased mucin deposition. However, scleromyxedema commonly is associated with fibroblast proliferation, which is characteristically absent in scleredema (Figure 5).11

The Diagnosis: Scleredema Diabeticorum

Histologically, scleredema is characterized by mucin deposition between collagen bundles in the deep dermis. Clinically, it is characterized by a progressive indurated plaque with associated stiffness of the involved area. It most commonly presents on the posterior aspect of the neck, though it can extend to involve the shoulders and upper torso.1 Scleredema is divided into 3 subtypes based on clinical associations. Type 1 often is preceded by an infection, most commonly group A Streptococcus. This type occurs acutely and often resolves completely over a few months.2 Type 2, which has progressive onset, is associated with monoclonal gammopathy.3 Type 3 is the most common type and is associated with diabetes mellitus. A study of 484 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus demonstrated a prevalence of 2.5%.4 Although the exact pathogenesis has not been defined, it is hypothesized that irreversible glycosylation of collagen and alterations in collagenase activity may lead to accumulation of collagen and mucin in the dermis.5 Similar to type 2, type 3 scleredema appears subtly, progresses slowly, and tends to be chronic.1,6 Scleredema is characterized by marked dermal thickening and enlarged collagen bundles separated by mucin deposition (Figure 1). Fibroblast proliferation is characteristically absent.1

Clinically, tumid lupus erythematosus presents with erythematous edematous plaques on sun-exposed areas.7 Pretibial myxedema (PM) classically is associated with Graves disease; however, it can present in association with other types of thyroid dysfunction. Classically, PM presents on the pretibial regions as well-demarcated erythematous or hyperpigmented plaques.8 Similar to scleredema, histologic examination of tumid lupus erythematosus and PM reveals mucin deposition. Tumid lupus erythematosus also may demonstrate periadnexal and perivascular lymphocytic inflammation (Figure 2).7 The collagen bundles present in PM often are thin in comparison to scleredema (Figure 3).8

Scleroderma also presents with skin induration, erythema, and stiffening. However, unlike scleredema, scleroderma commonly involves the fingers, toes, and face. It presents with symptoms of Raynaud phenomenon, painful digital nonpitting edema, perioral skin tightening, mucocutaneous telangiectasia, and calcinosis cutis. Scleroderma also can involve organs such as the lungs, heart, kidneys, and gastrointestinal tract.9 Histologically, scleroderma is characterized by a compact dermis with closely packed collagen bundles. Other features of scleroderma can include perivascular mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltration, progressive atrophy of intradermal and perieccrine fat, and fibrosis (Figure 4).10

Scleromyxedema, also called papular mucinosis, is primary dermal mucinosis that often presents with waxy, dome-shaped papules that may coalesce into plaques. Similar to scleredema, scleromyxedema shows increased mucin deposition. However, scleromyxedema commonly is associated with fibroblast proliferation, which is characteristically absent in scleredema (Figure 5).11

- Beers WH, Ince A, Moore TL. Scleredema adultorum of Buschke: a case report and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35:355-359.

- Cron RQ, Swetter SM. Scleredema revisited. a poststreptococcal complication. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1994;33:606-610.

- Kövary PM, Vakilzadeh F, Macher E, et al. Monoclonal gammopathy in scleredema. observations in three cases. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:536-539.

- Cole GW, Headley J, Skowsky R. Scleredema diabeticorum: a common and distinct cutaneous manifestation of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1983;6:189-192.

- Namas R, Ashraf A. Scleredema of Buschke. Eur J Rheumatol. 2016;3:191-192.

- Knobler R, Moinzadeh P, Hunzelmann N, et al. European Dermatology Forum S1-guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of sclerosing diseases of the skin, part 2: scleromyxedema, scleredema and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:1581-1594.

- Kuhn A, Richter-Hintz D, Oslislo C, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus--a neglected subset of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: report of 40 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1033-1041.

- Fatourechi V. Pretibial myxedema: pathophysiology and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:295-309.

- van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, et al. 2013 Classification Criteria for Systemic Sclerosis: An American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism Collaborative Initiative. 2013;65:2737-2747.

- Ferreli C, Gasparini G, Parodi A, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of scleroderma and scleroderma-like disorders: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2017;53:306-336.

- Rongioletti F, Merlo G, Cinotti E, et al. Scleromyxedema: a multicenter study of characteristics, comorbidities, course, and therapy in 30 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:66-72.

- Beers WH, Ince A, Moore TL. Scleredema adultorum of Buschke: a case report and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35:355-359.

- Cron RQ, Swetter SM. Scleredema revisited. a poststreptococcal complication. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1994;33:606-610.

- Kövary PM, Vakilzadeh F, Macher E, et al. Monoclonal gammopathy in scleredema. observations in three cases. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:536-539.

- Cole GW, Headley J, Skowsky R. Scleredema diabeticorum: a common and distinct cutaneous manifestation of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1983;6:189-192.

- Namas R, Ashraf A. Scleredema of Buschke. Eur J Rheumatol. 2016;3:191-192.

- Knobler R, Moinzadeh P, Hunzelmann N, et al. European Dermatology Forum S1-guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of sclerosing diseases of the skin, part 2: scleromyxedema, scleredema and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:1581-1594.

- Kuhn A, Richter-Hintz D, Oslislo C, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus--a neglected subset of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: report of 40 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1033-1041.

- Fatourechi V. Pretibial myxedema: pathophysiology and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:295-309.

- van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, et al. 2013 Classification Criteria for Systemic Sclerosis: An American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism Collaborative Initiative. 2013;65:2737-2747.

- Ferreli C, Gasparini G, Parodi A, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of scleroderma and scleroderma-like disorders: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2017;53:306-336.

- Rongioletti F, Merlo G, Cinotti E, et al. Scleromyxedema: a multicenter study of characteristics, comorbidities, course, and therapy in 30 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:66-72.

A 39-year-old white woman with a medical history of type 1 diabetes mellitus and rheumatoid arthritis presented to the dermatology clinic with pain and thickened skin on the posterior neck of 4 weeks’ duration. The patient noted stiffness in the neck and shoulders but denied any pain, pruritus, fever, chills, night sweats, fatigue, cough, dyspnea, dysphagia, weight loss, or change in appetite. Physical examination revealed a woody indurated plaque with slight erythema that was present diffusely on the posterior neck and upper back. The patient reported that a recent complete blood cell count and complete metabolic panel performed by her primary care physician were within reference range. Hemoglobin A1C was 8.6% of total hemoglobin (reference range, 4%–7%). A punch biopsy was performed.

Purpuric Bullae on the Lower Extremities

The Diagnosis: Bullous Leukocytoclastic Vasculitis

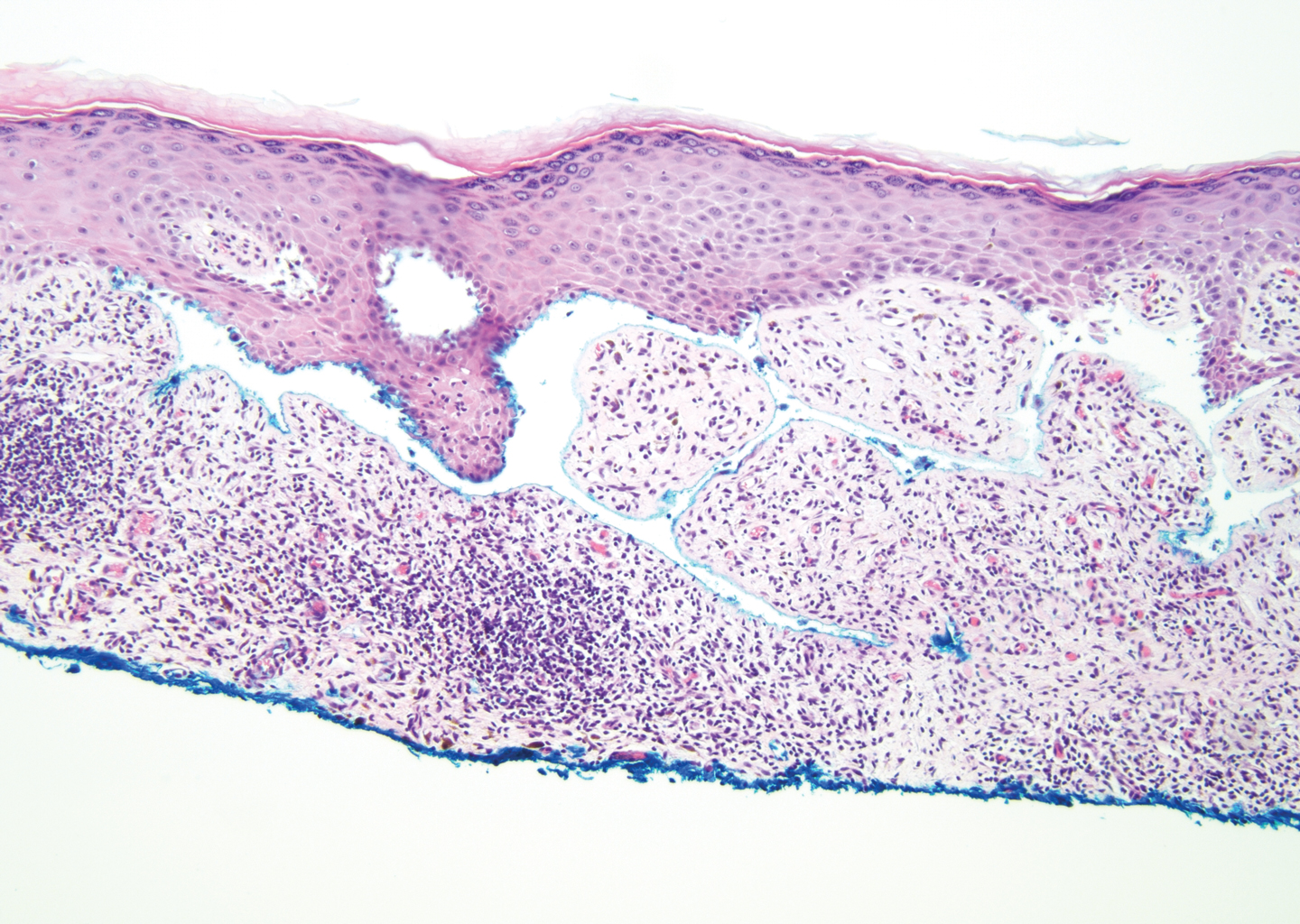

Histopathology with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain showed a perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate, karyorrhexis, red blood cell extravasation, and fibrin deposition in the vessel wall (quiz images). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) showed fibrin surrounding the vasculature, consistent with vasculitis. The clinical and histopathological evaluation supported the diagnosis of bullous leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV). The patient had a full LCV workup including antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, hepatitis B and hepatitis C screening, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and C3/C4/total complement level, which were all within reference range. The patient denied that she had taken any medications prior to the onset of the rash. She was started on a 12-day prednisone taper starting at 60 mg, and the rash resolved in 1 week.

Although the incidence of LCV is estimated to be 30 cases per million individuals per year,1 bullous LCV is a rarer entity with only a few cases reported in the literature.2,3 As in our patient's case, up to 50% of LCV cases are idiopathic or the etiology cannot be determined despite laboratory workup and medication review. Other cases can be secondary to medication, infection, collagen vascular disease, or malignancy.3 Despite the exact pathogenesis of bullous LCV being unknown,4 it likely is related to a type III hypersensitivity reaction with immune complex deposition in postcapillary venules leading to endothelial injury, activation of the complement cascade, and development of intraepidermal or subepidermal blister formation depending on location of inflammation and edema.2 Clinically, an intraepidermal split would be more flaccid, similar to pemphigus vulgaris, while a subepidermal split, as in our patient, would be taut bullae. The subepidermal split more commonly is seen in bullous LCV.2

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis on H&E staining characteristically has a perivascular inflammatory infiltrate, neutrophilic fragments called leukocytoclasis, and blood extravasation.3 Extravasated blood presents clinically as petechiae. In this case, the petechiae helped distinguish this entity from the differential diagnosis. Furthermore, DIF would be helpful in distinguishing bullous diseases such as bullous pemphigoid (BP) and pemphigus vulgaris from LCV.2 Direct immunofluorescence in bullous LCV would have fibrinogen surrounding the vasculature without C3 and IgG deposition (intraepidermal or subepidermal).

Mild cases of LCV often resolve with supportive measures including elevation of the legs, ice packs applied to the affected area, and removal of the inciting drug or event.4 In the few cases reported in the literature, bullous LCV presented more diffusely than classic LCV with bullous lesions on the forearms and the lower extremities. Oral steroids are efficacious for extensive bullous LCV.4