User login

Painless Vulvar Nodule

The Diagnosis: Proximal-Type Epithelioid Sarcoma

Proximal-type epithelioid sarcoma (PES) is a rare high-grade sarcoma of uncertain histogenesis that may present with a benign clinical appearance. Proximal-type epithelioid sarcoma peaks at 20 to 40 years of age and has a slight male predominance. This tumor exhibits aggressive behavior with both local recurrence and metastasis.1 The average overall survival is poor; however, tumor size less than 5 cm and complete excision with tumor-free margin status improves the prognosis.2 Proximal-type epithelioid sarcoma should not be confused with distal-type epithelioid sarcoma, which has a better prognosis and occurs in younger patients.1 Treatment of PES is wide excision, and chemotherapy trials with tazemetostat are ongoing.3

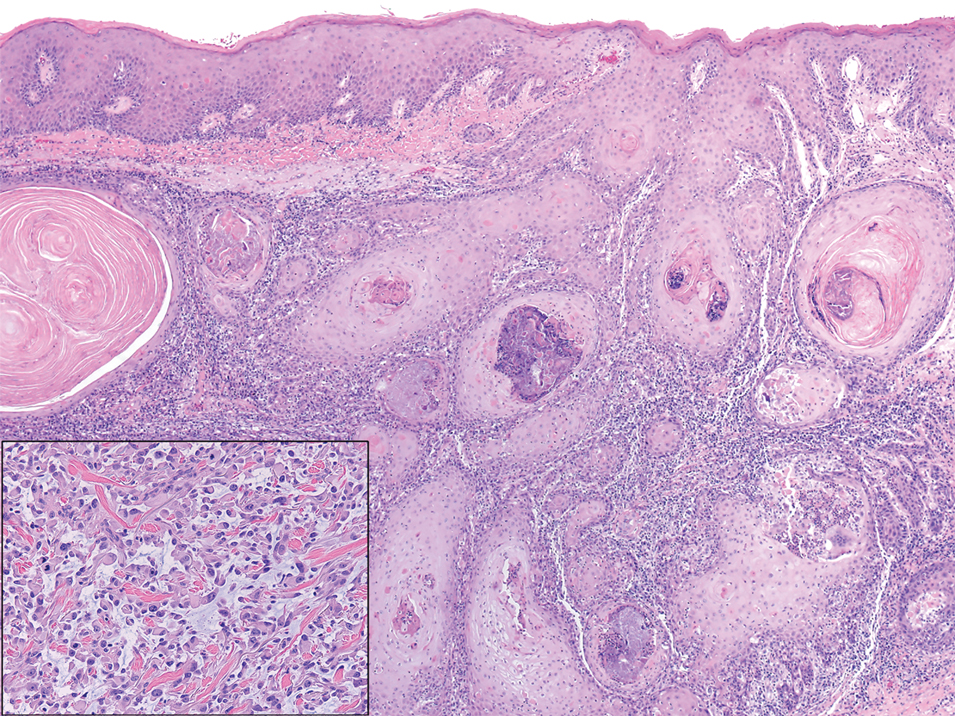

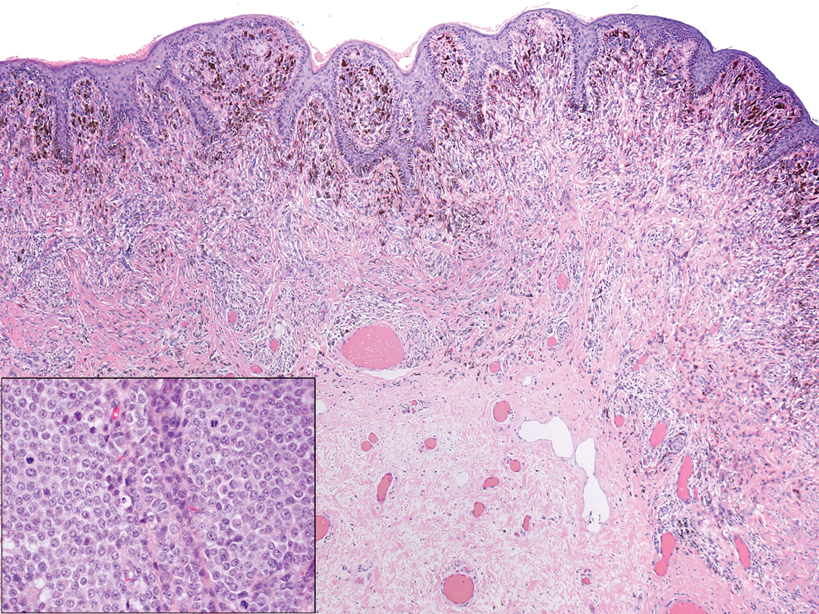

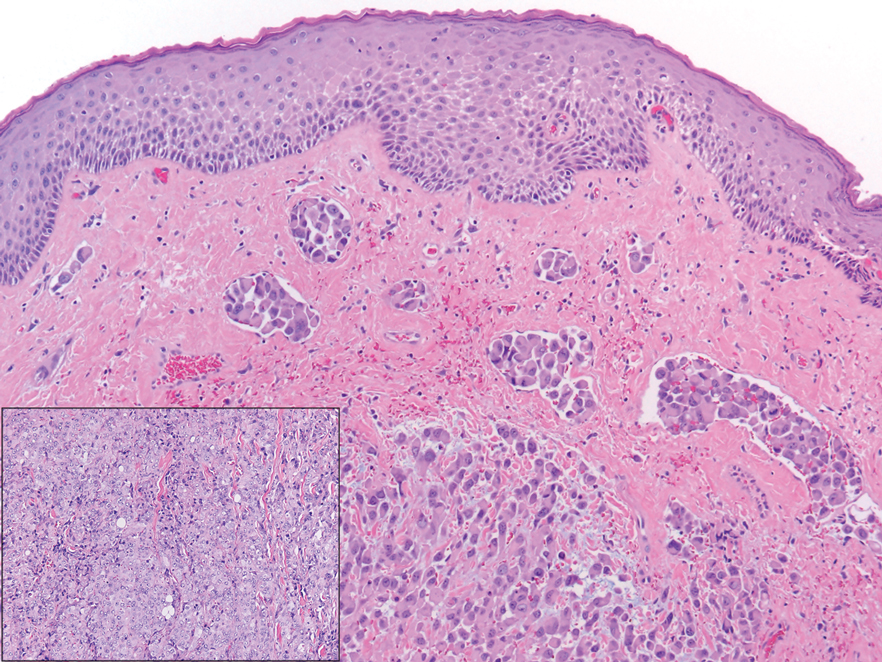

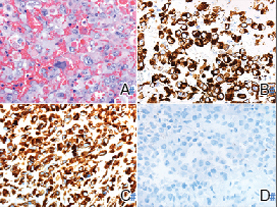

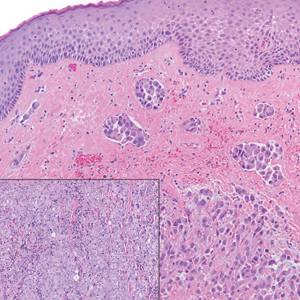

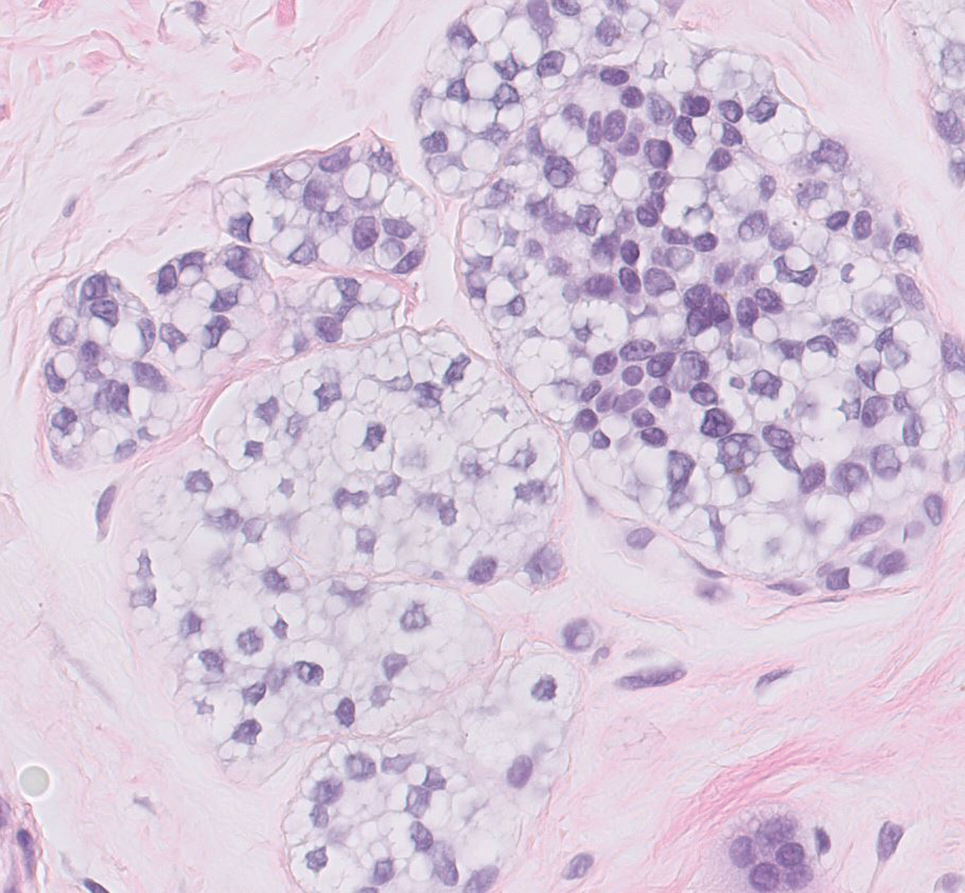

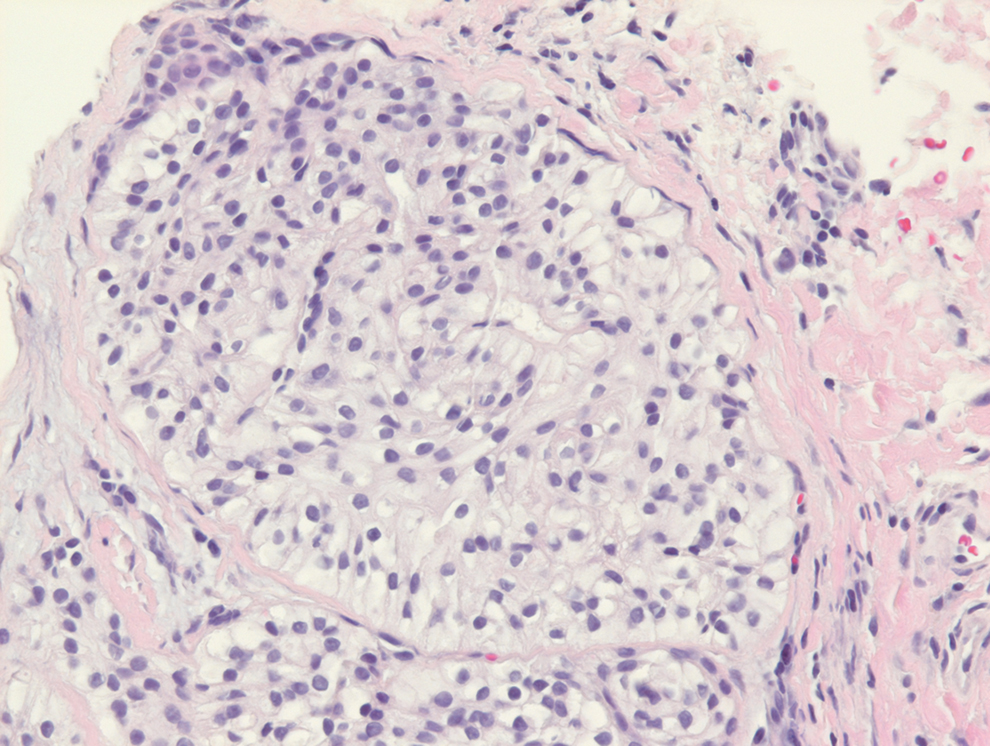

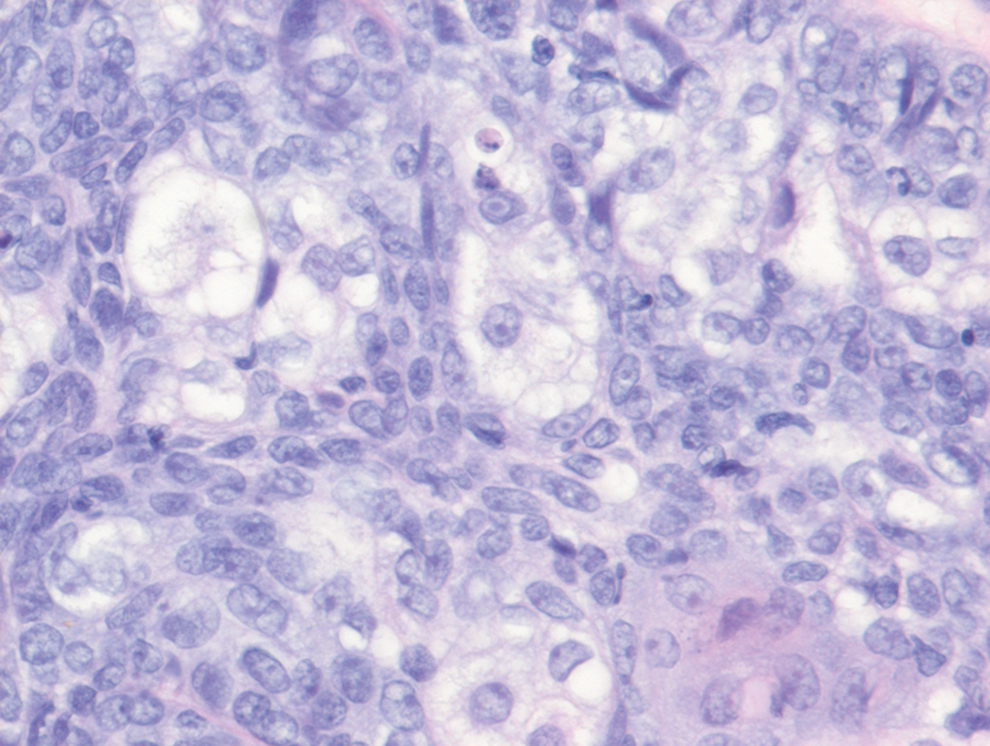

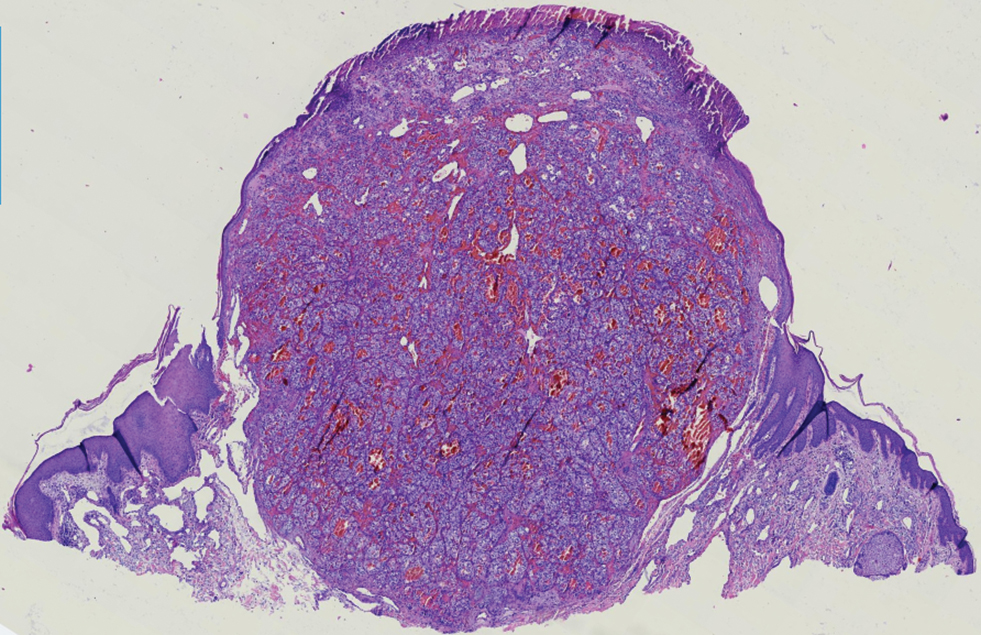

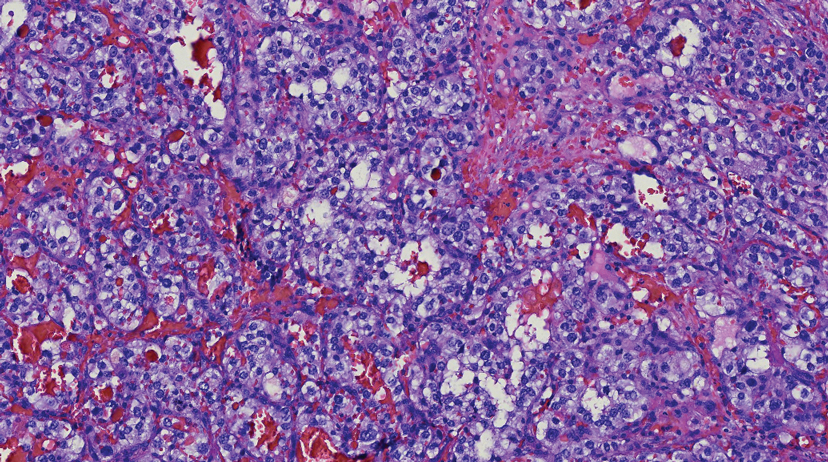

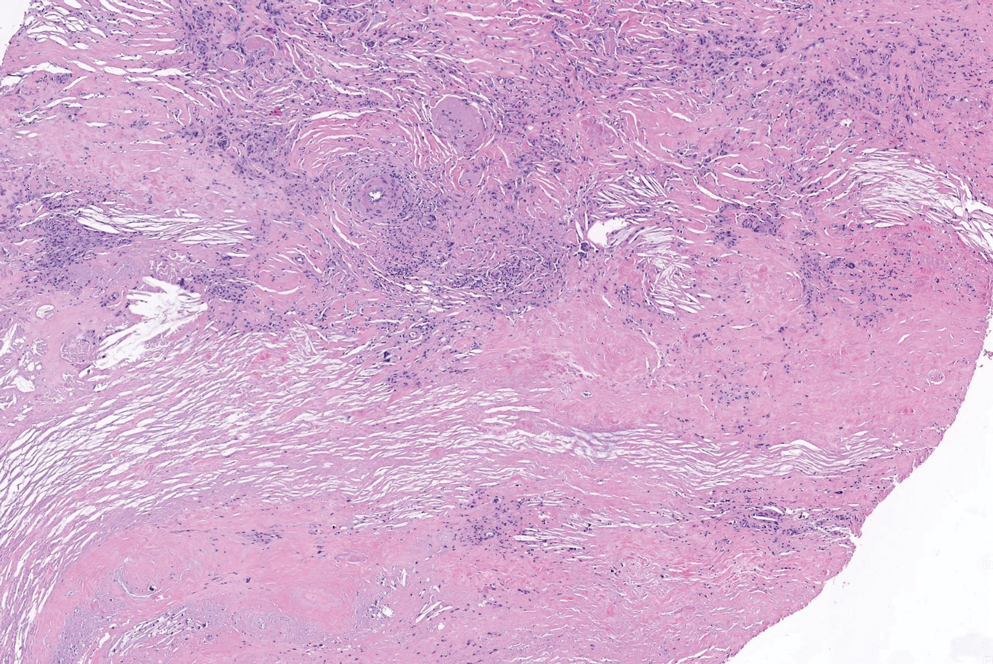

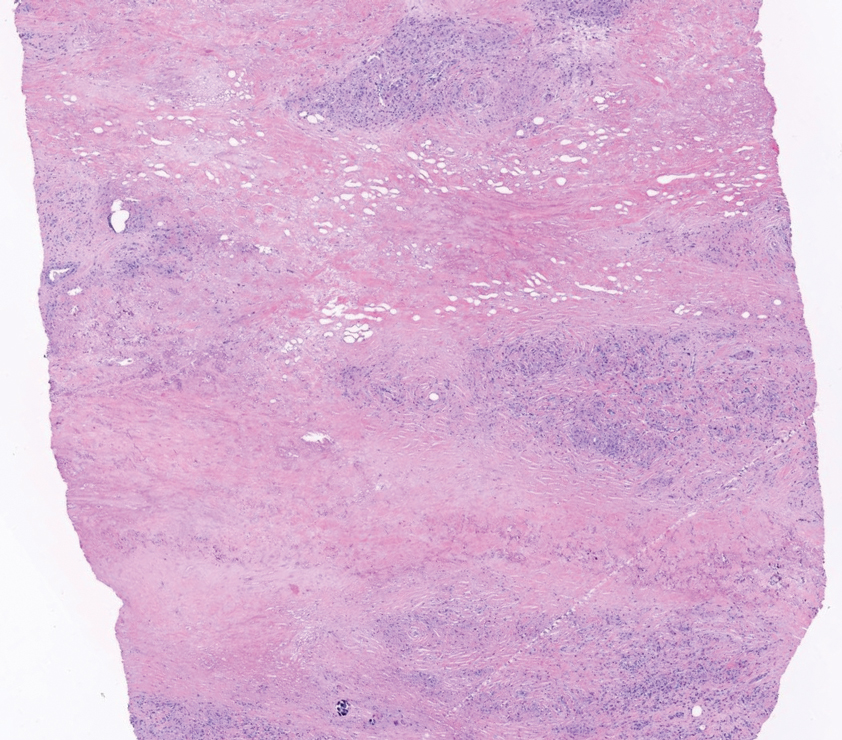

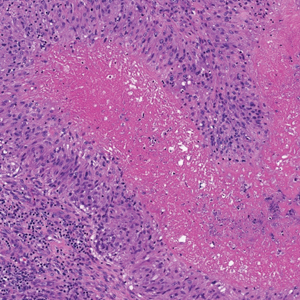

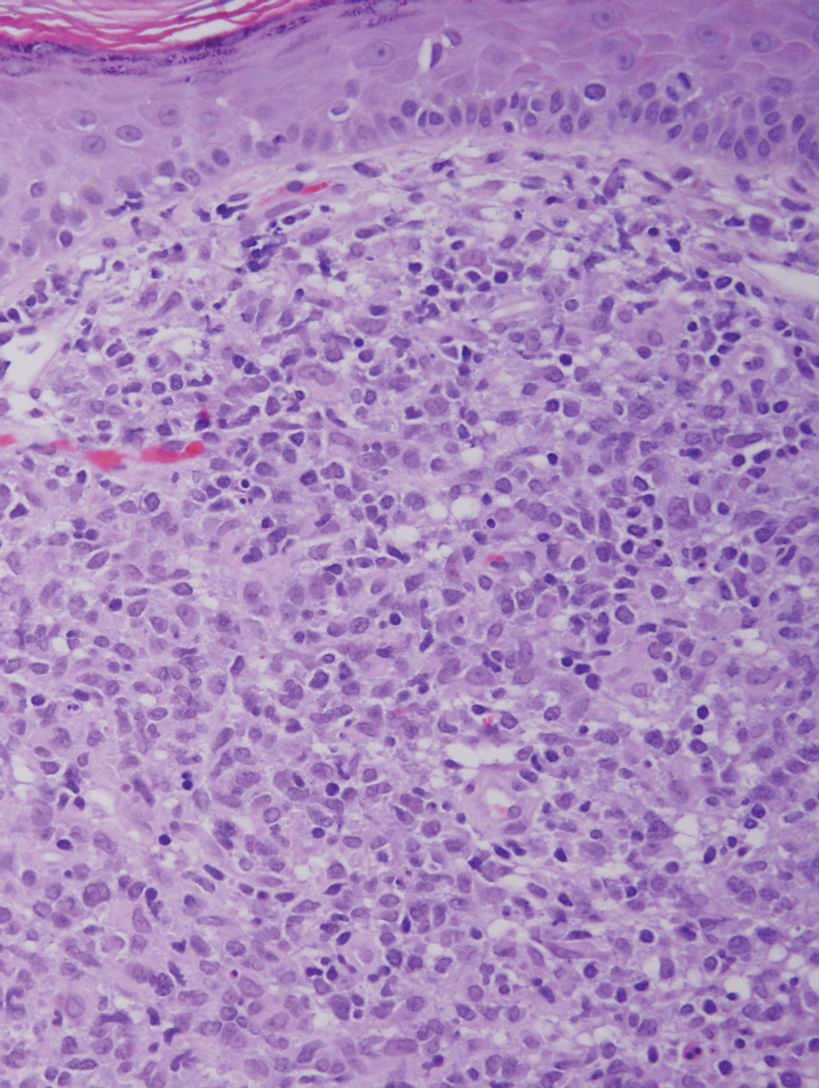

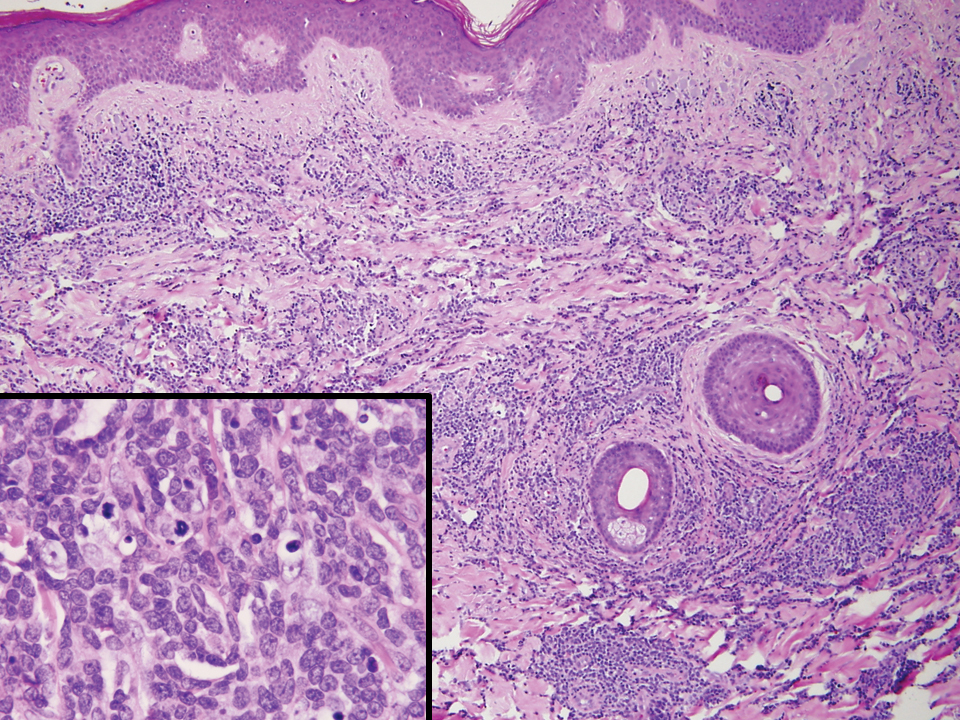

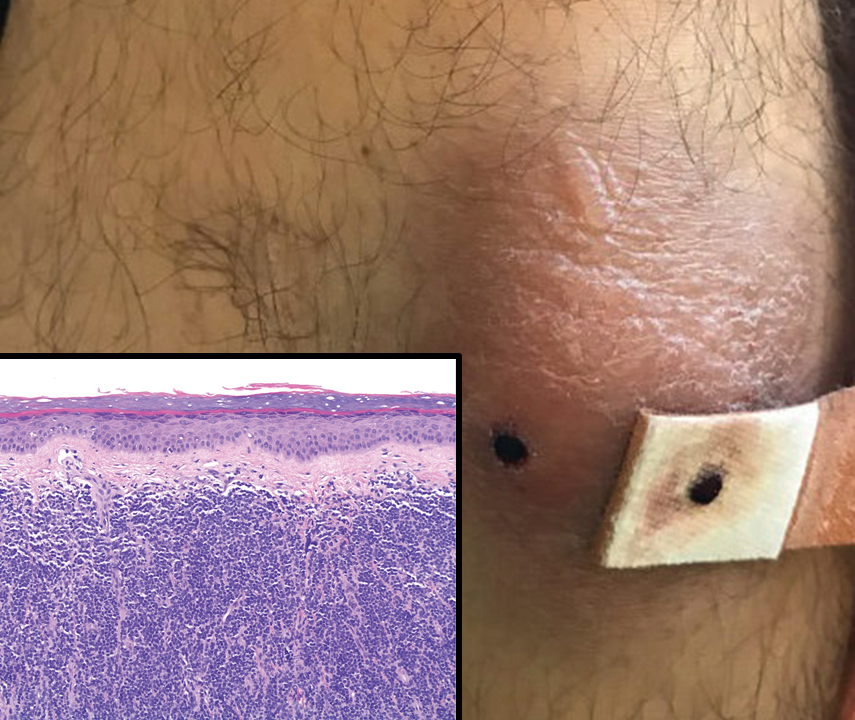

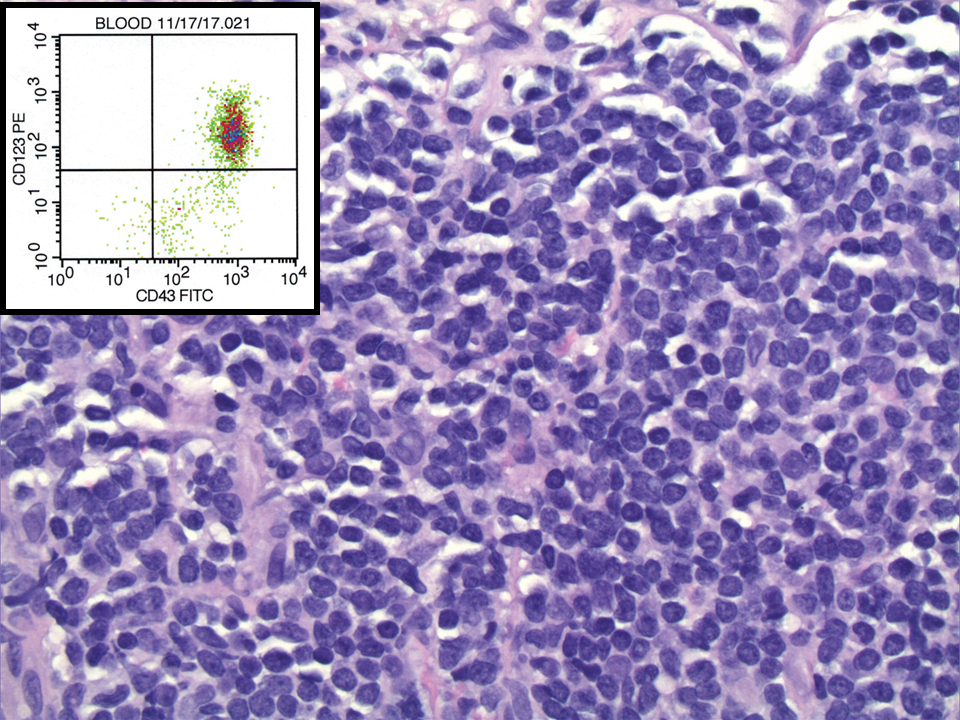

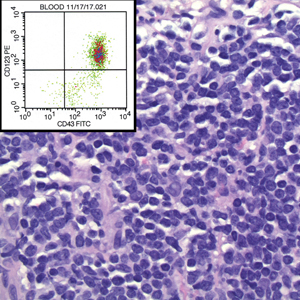

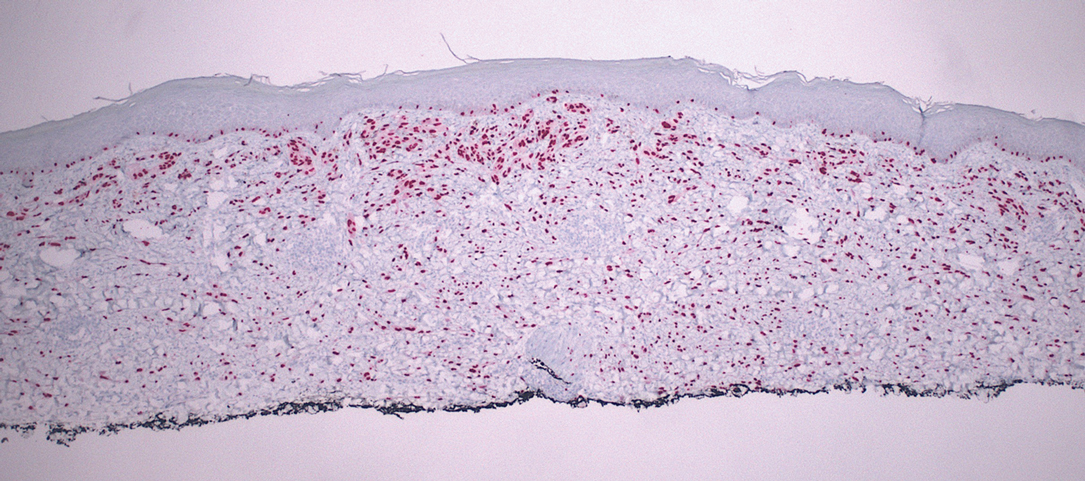

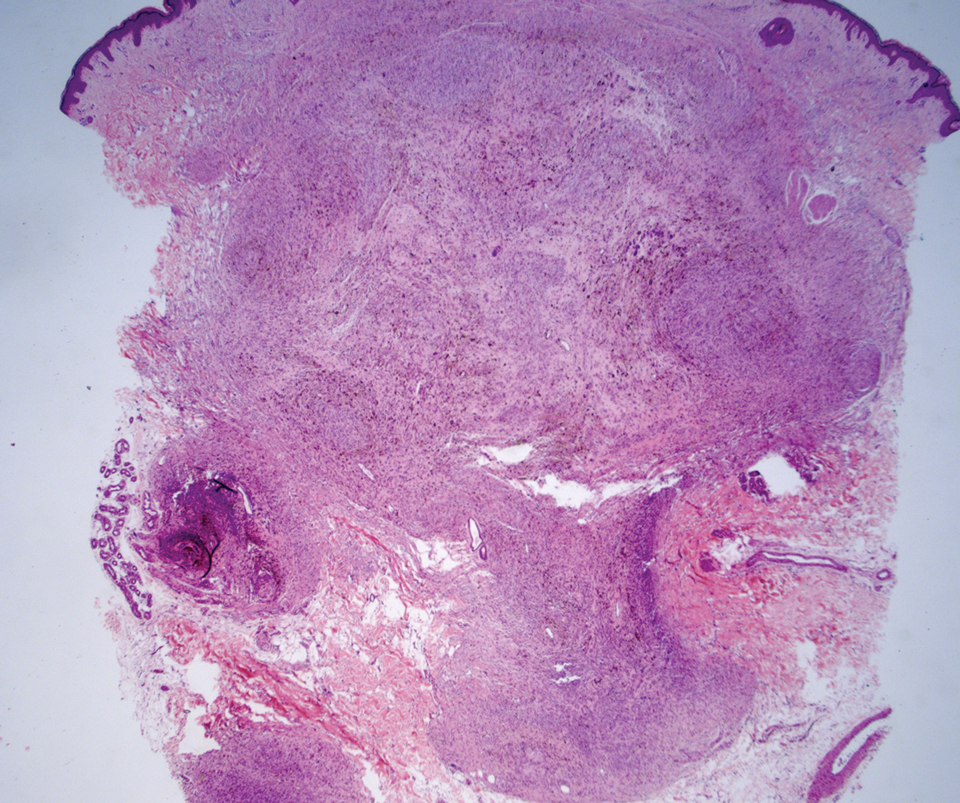

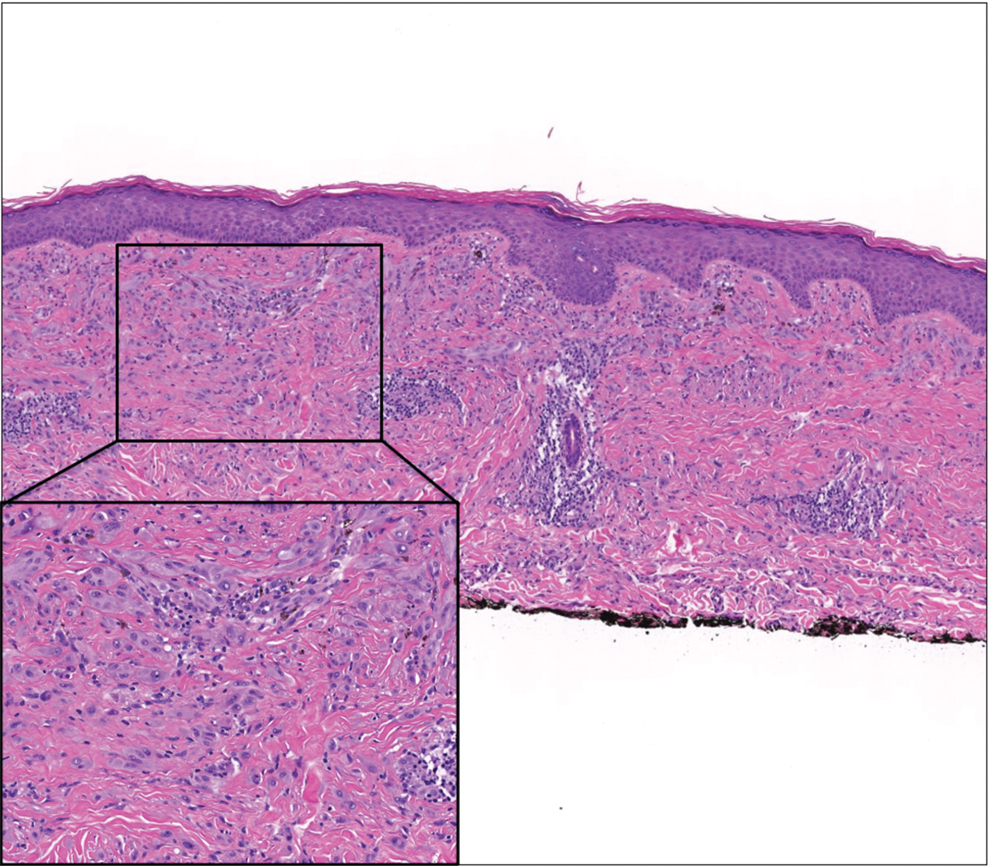

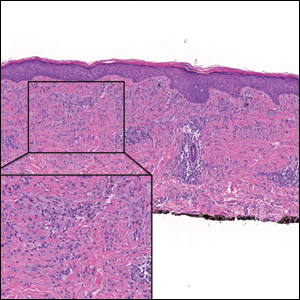

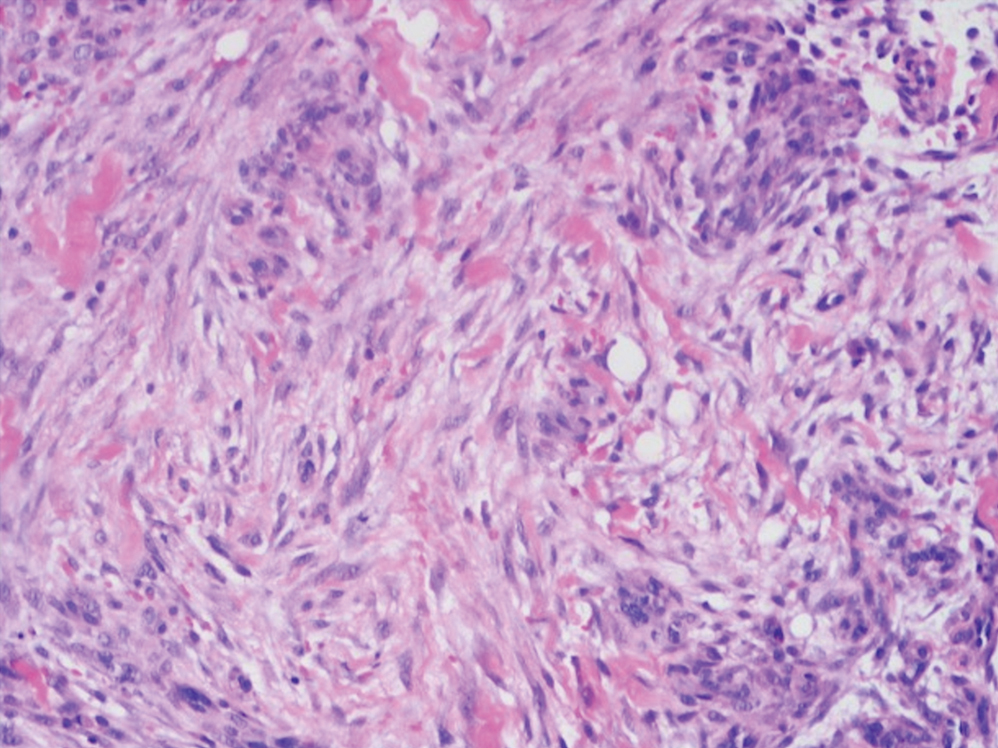

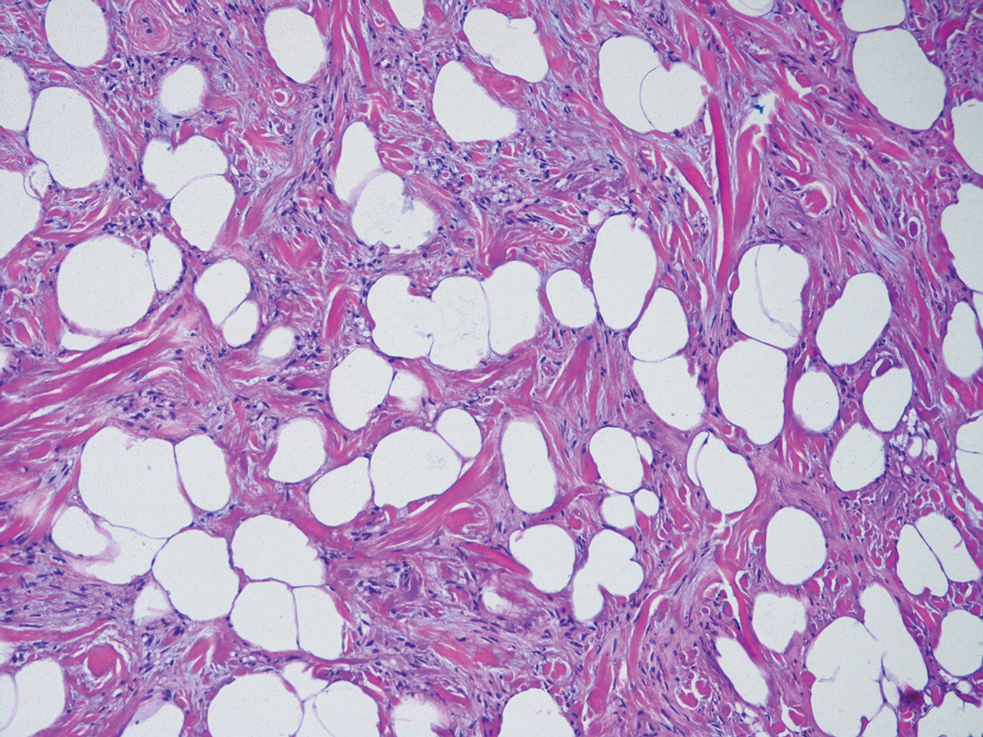

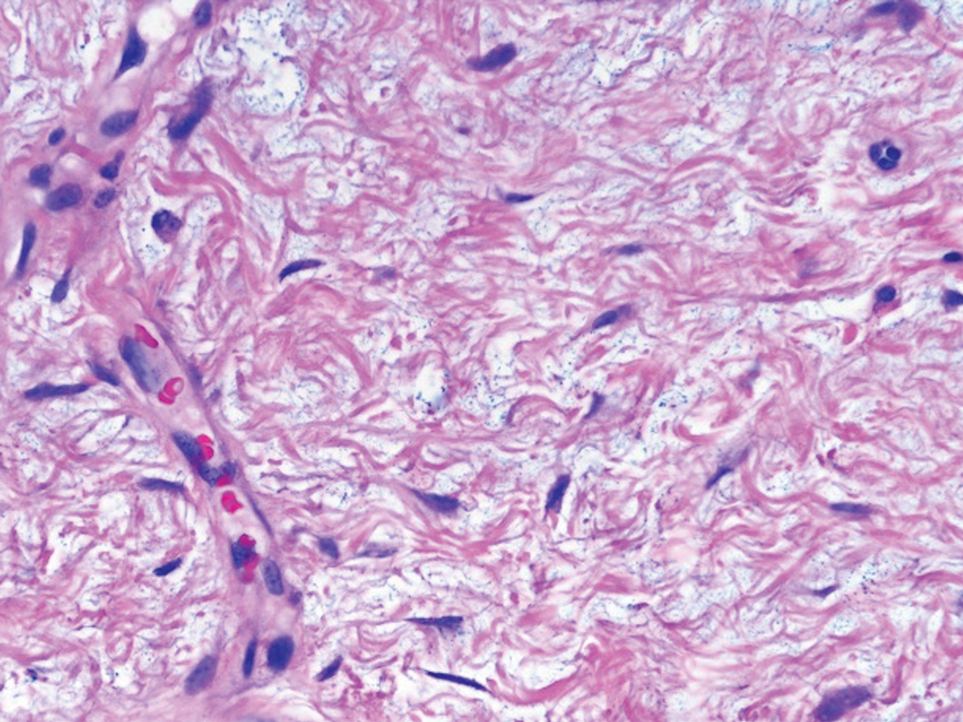

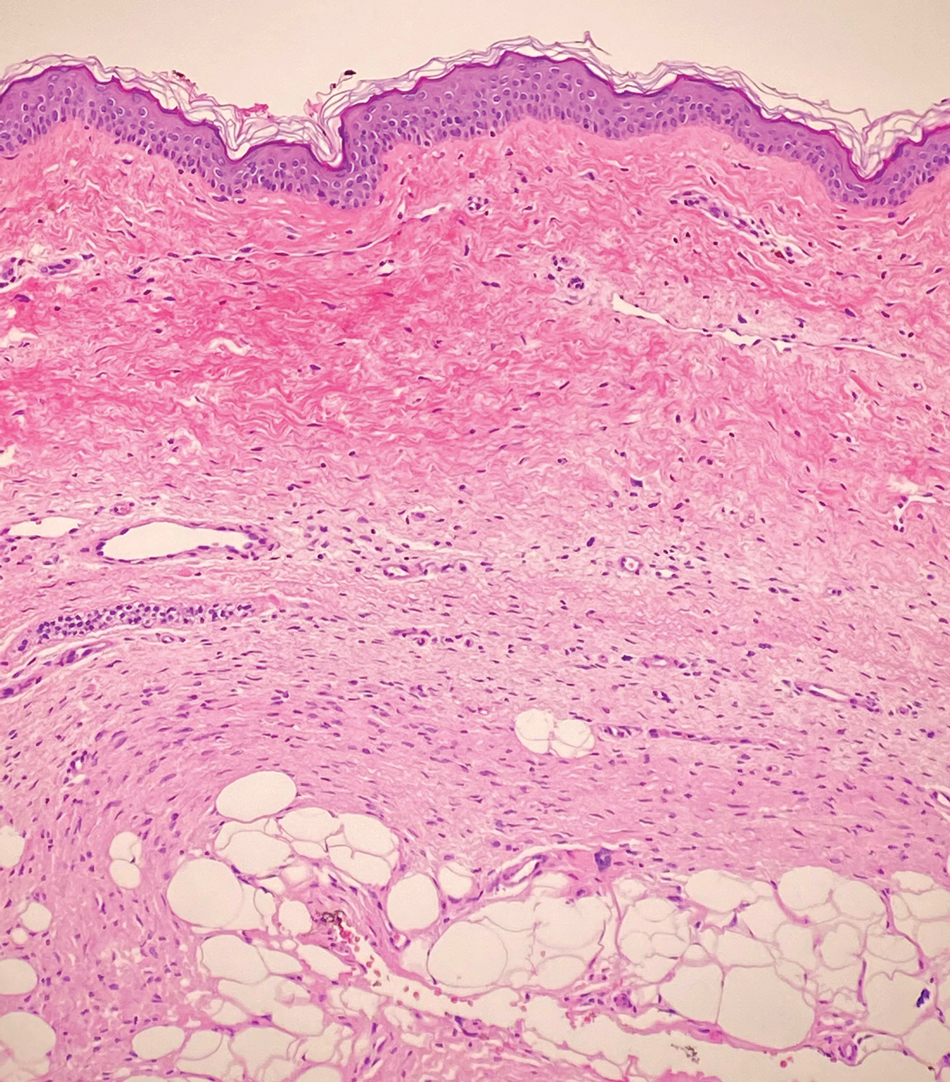

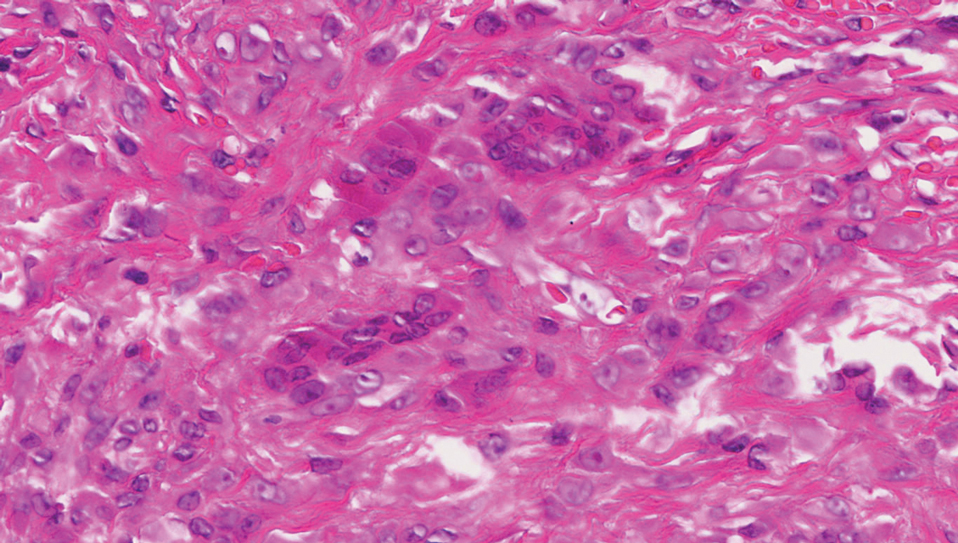

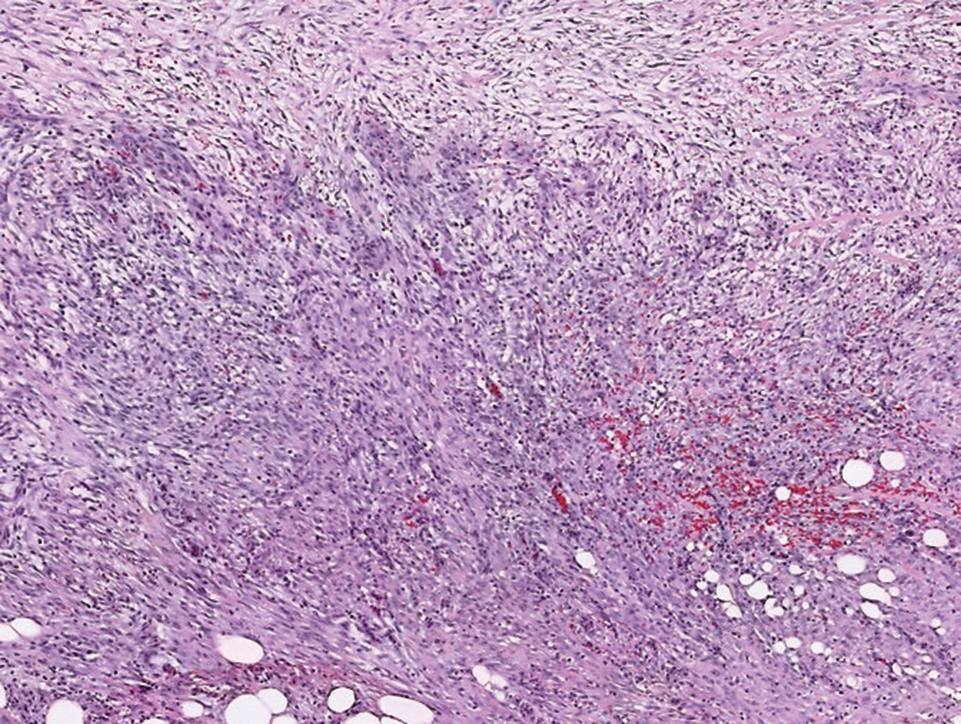

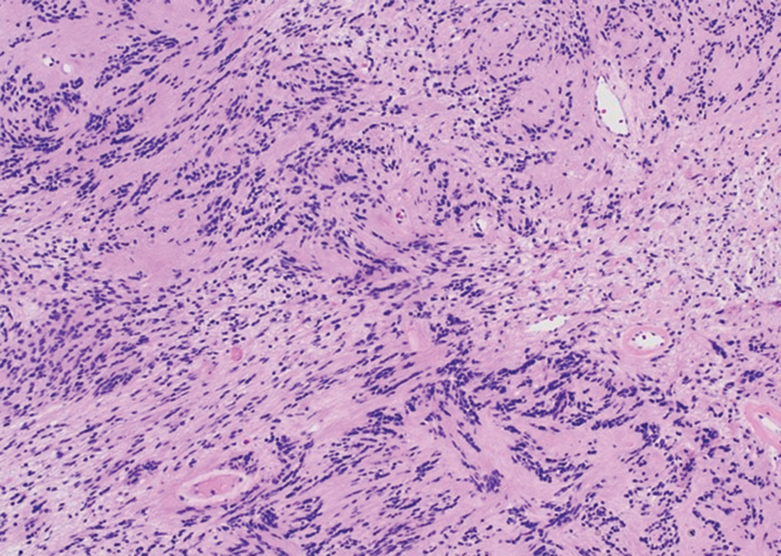

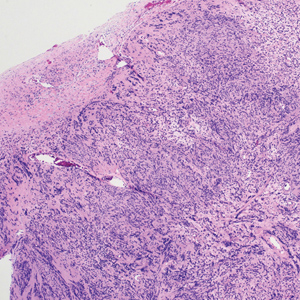

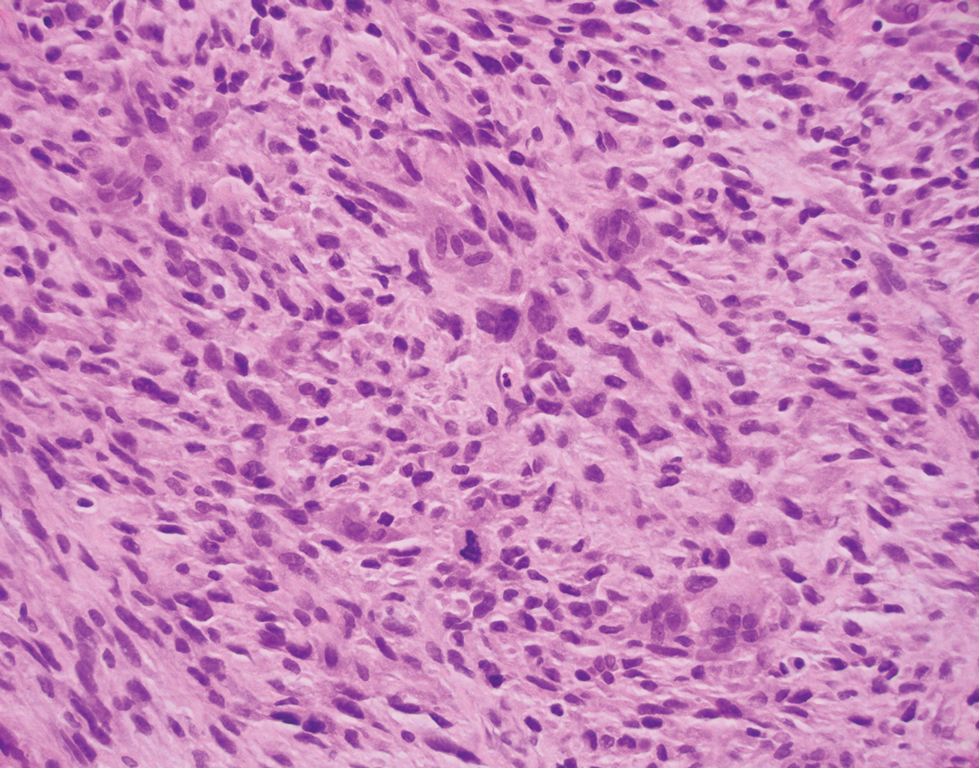

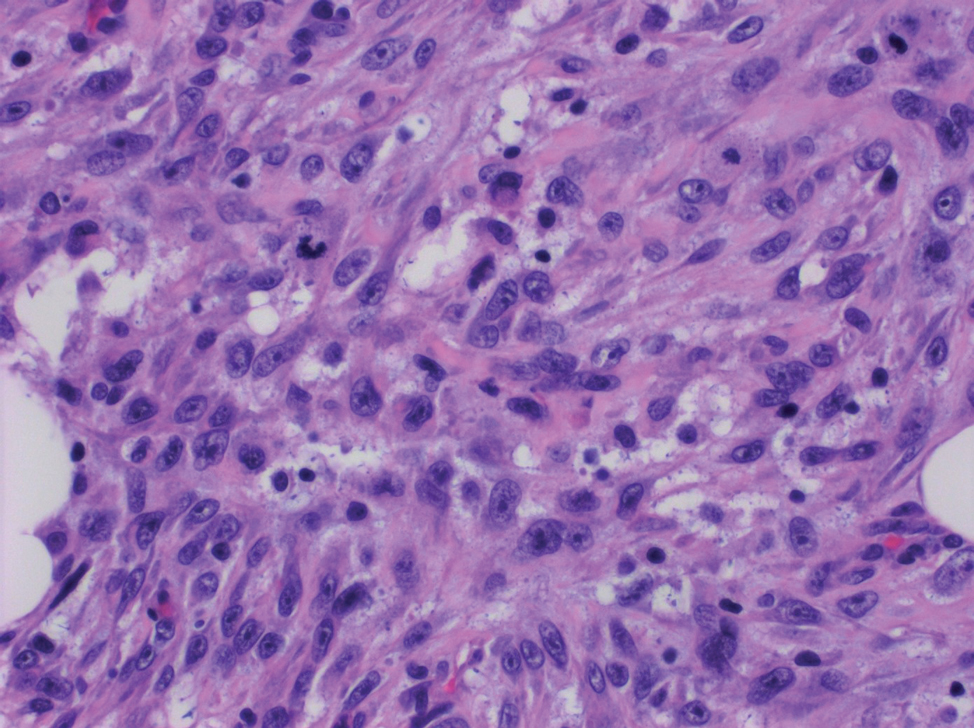

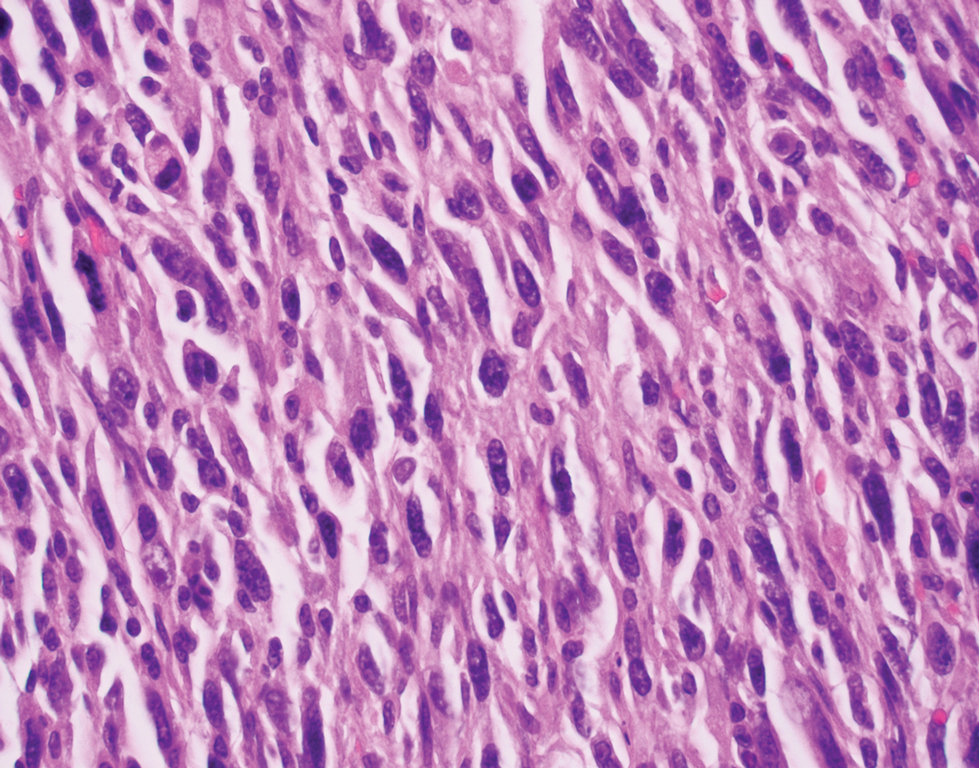

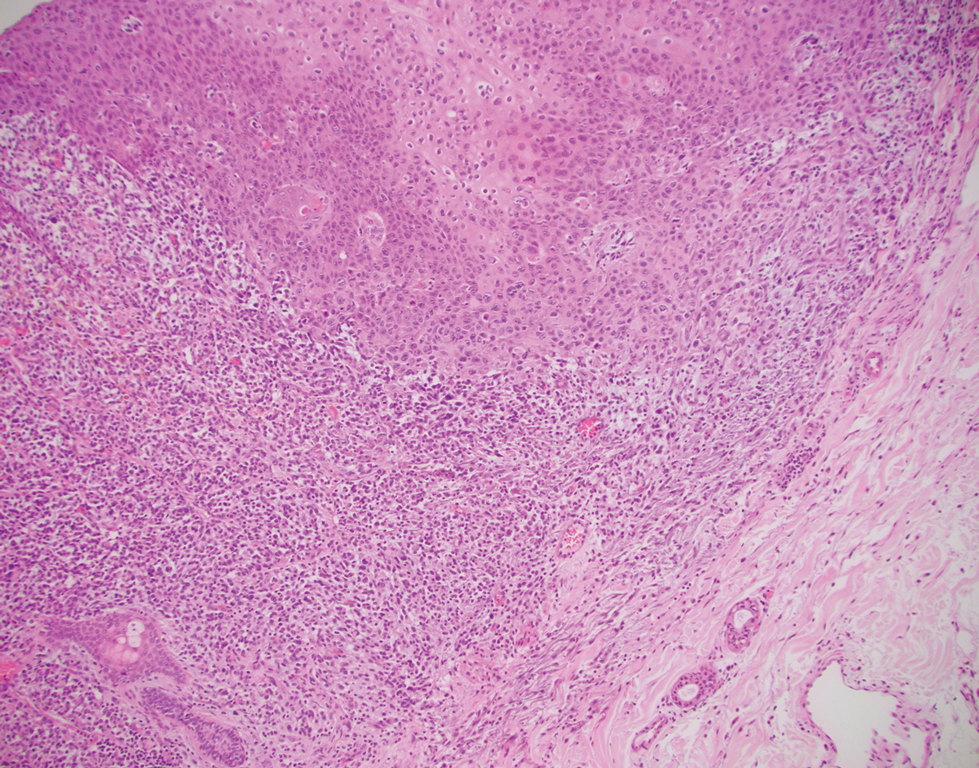

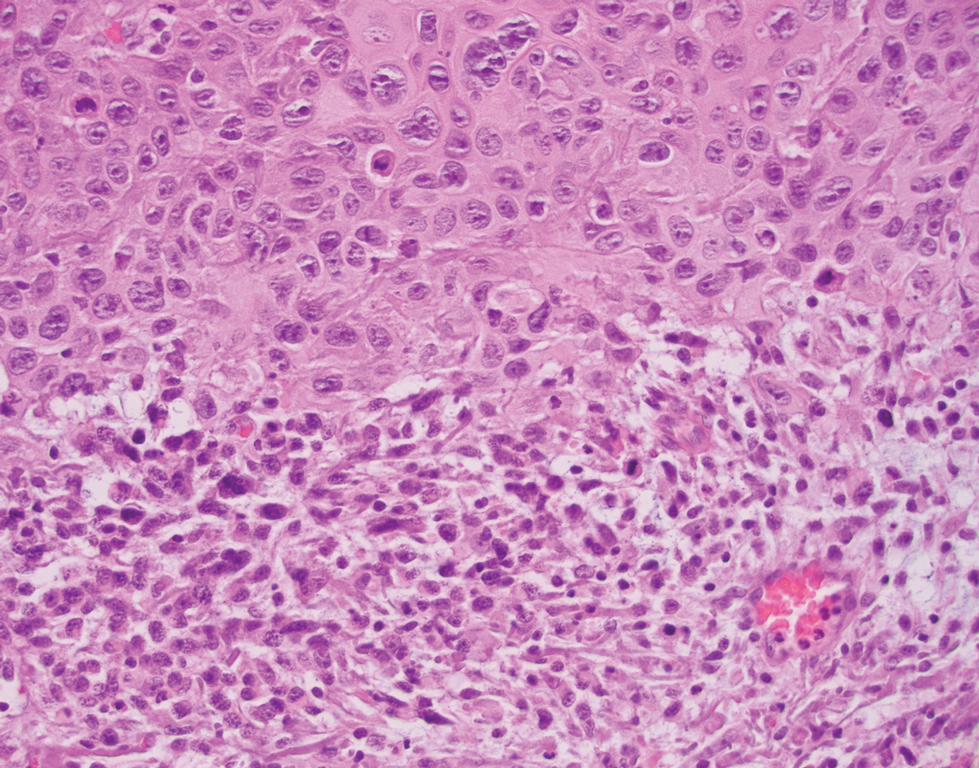

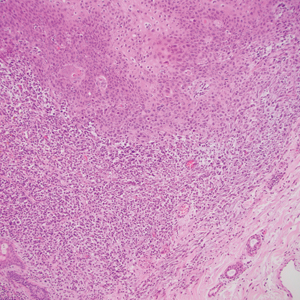

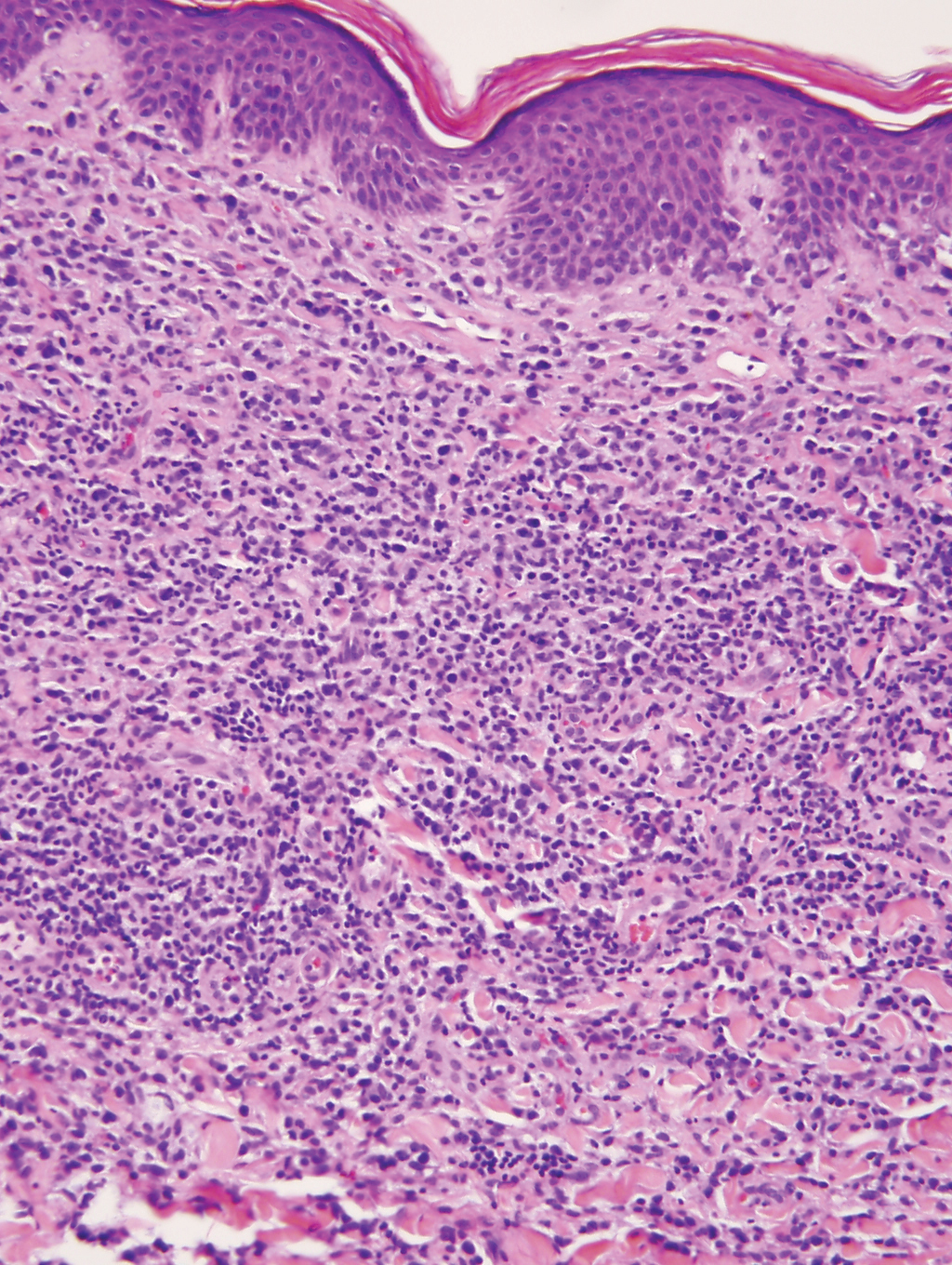

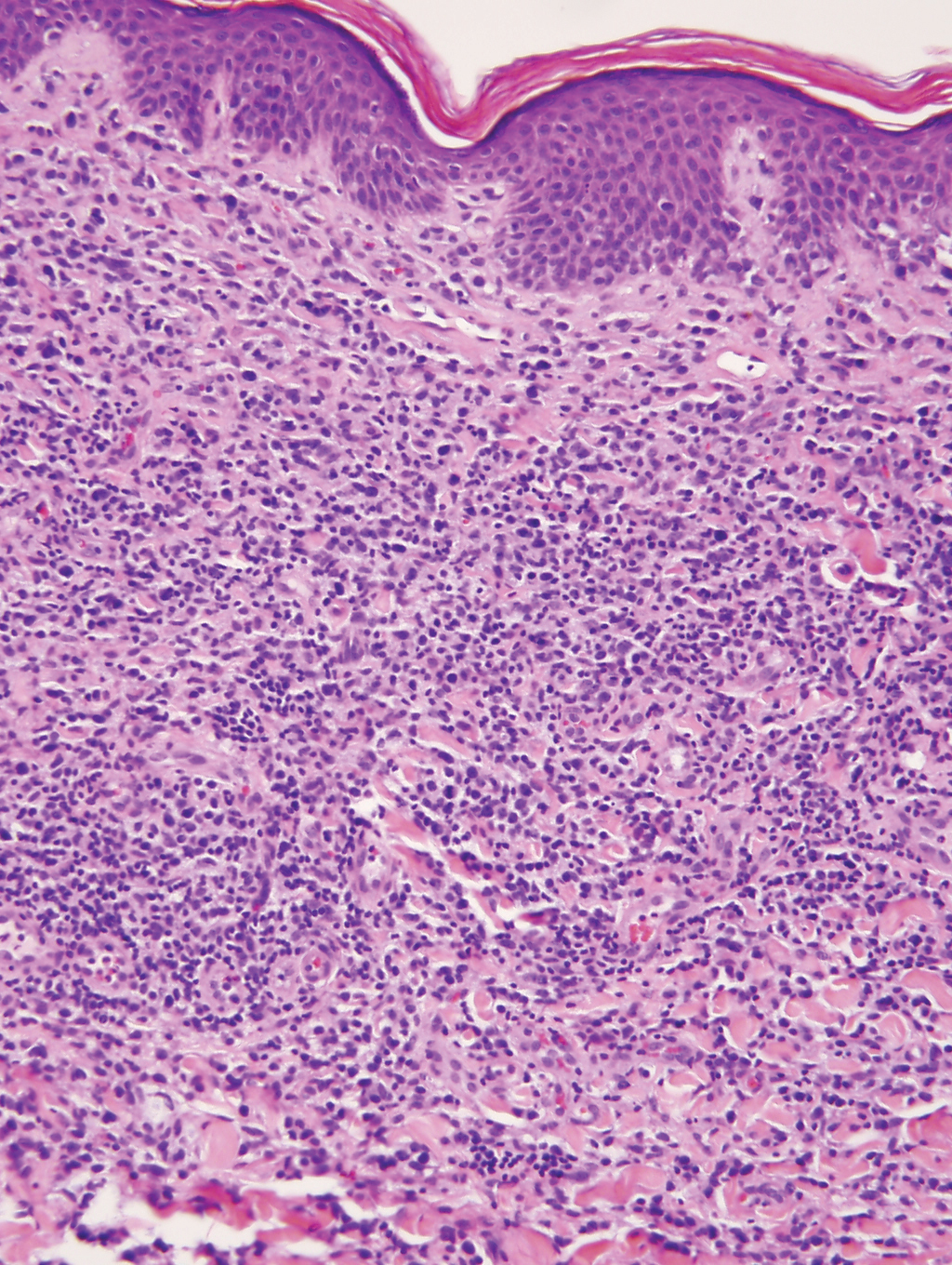

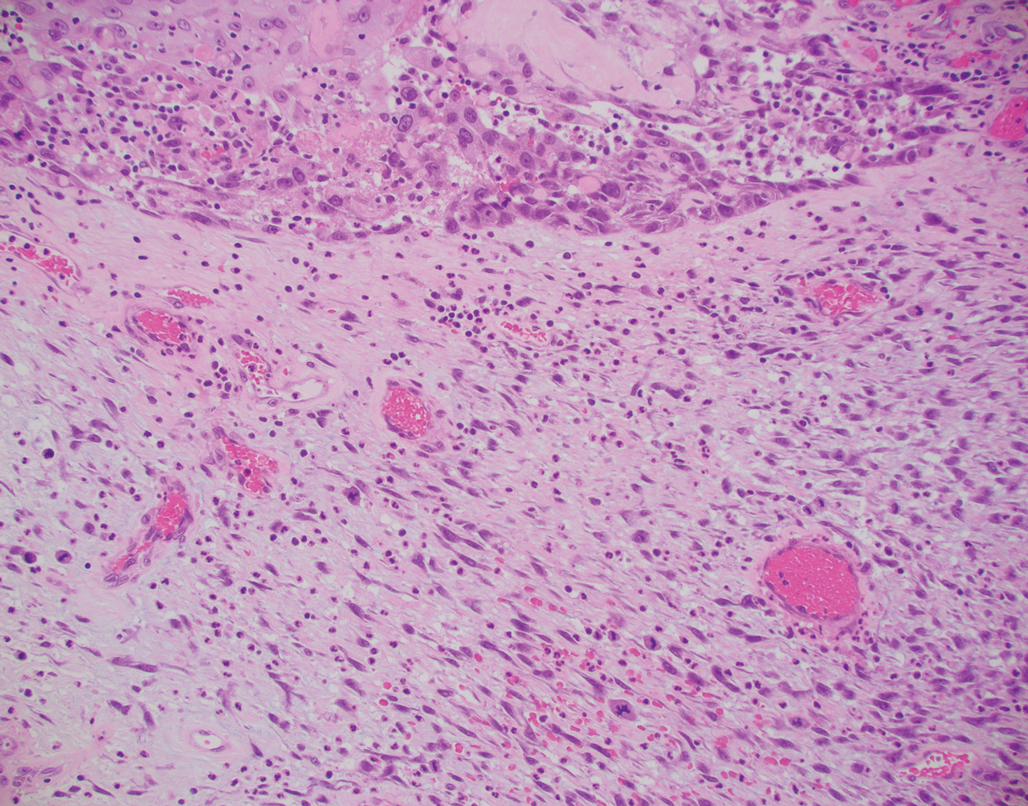

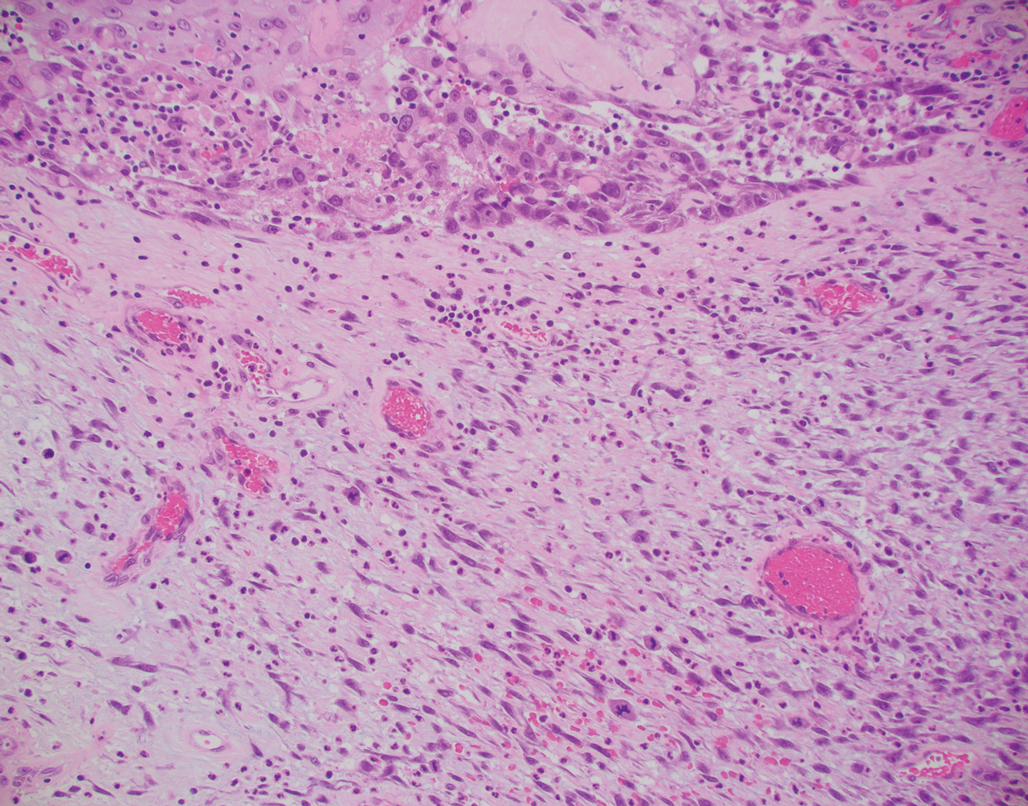

The deceptively banal clinical appearance of PES may delay appropriate diagnosis and treatment. Proximal-type epithelioid sarcoma often grows in sheets (quiz image [top] inset) and loose nests1 but also may take on a more corded appearance mimicking myoepithelial carcinoma. The cells themselves are plump dyscohesive epithelioid cells (quiz image [top]) with large nucleoli and eosinophilic cytoplasm or hyaline globules1 (quiz image [bottom]), but cells also may be focally spindled. Myxoid stroma, hemorrhage, and necrosis often are prominent features. Epithelioid sarcomas characteristically demonstrate positive immunostaining for both epithelial and mesenchymal markers (pan-cytokeratin and vimentin),1 with the majority having loss of expression of integrase interactor 1 (INI-1).2 Histology in this case was positive for cytokeratin monoclonal antibodies CAM5.2 and OSCAR, epithelial membrane antigen, and vimentin; it showed loss of INI-1 staining (quiz image [bottom]). Negative stains included S-100, p63, cytokeratins 7 and 20, CD34, CD31, ERG, glial fibrillary acidic protein, transducin-like enhancer of split 1, CD117, myogenin, synaptophysin, chromogranin, CD10, inhibin, CD99, and estrogen receptor.

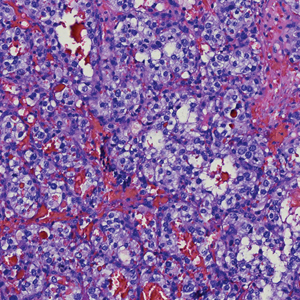

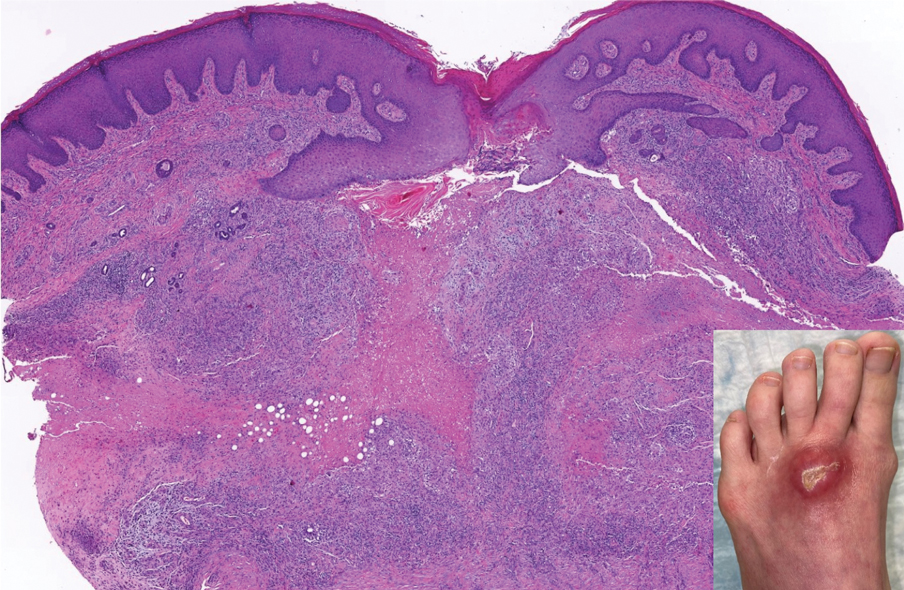

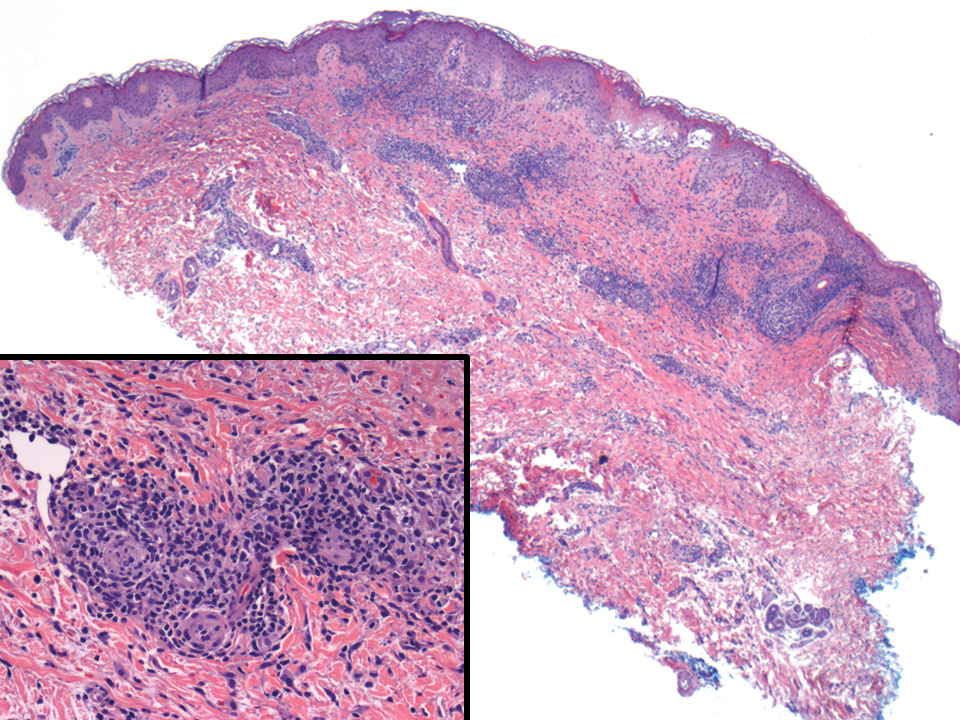

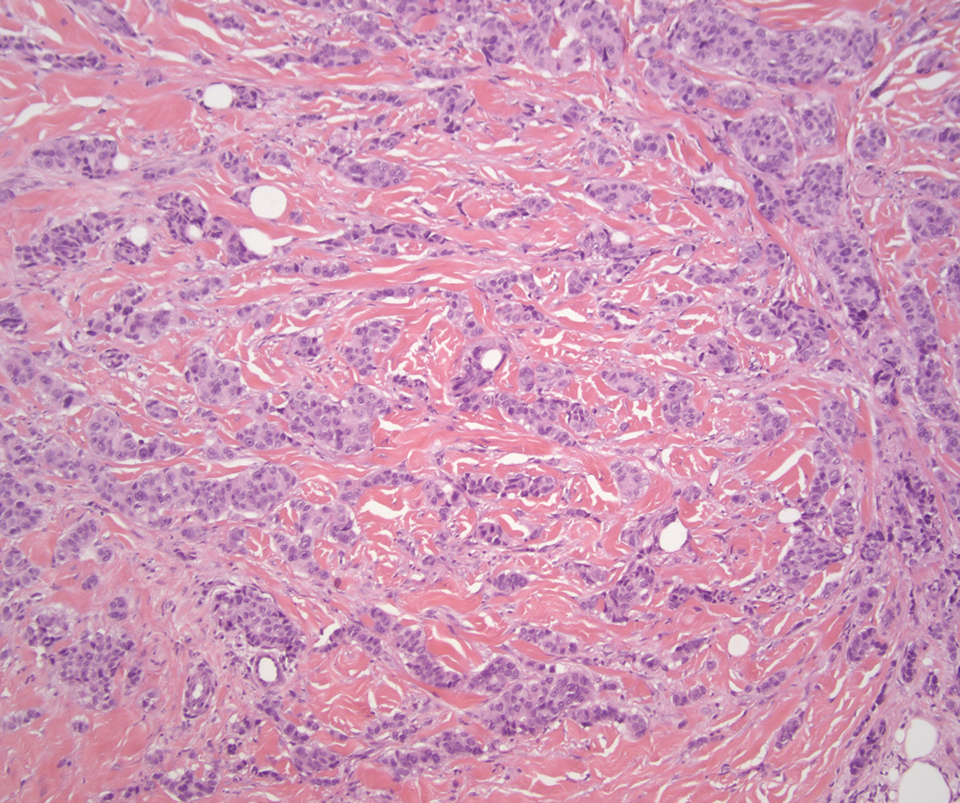

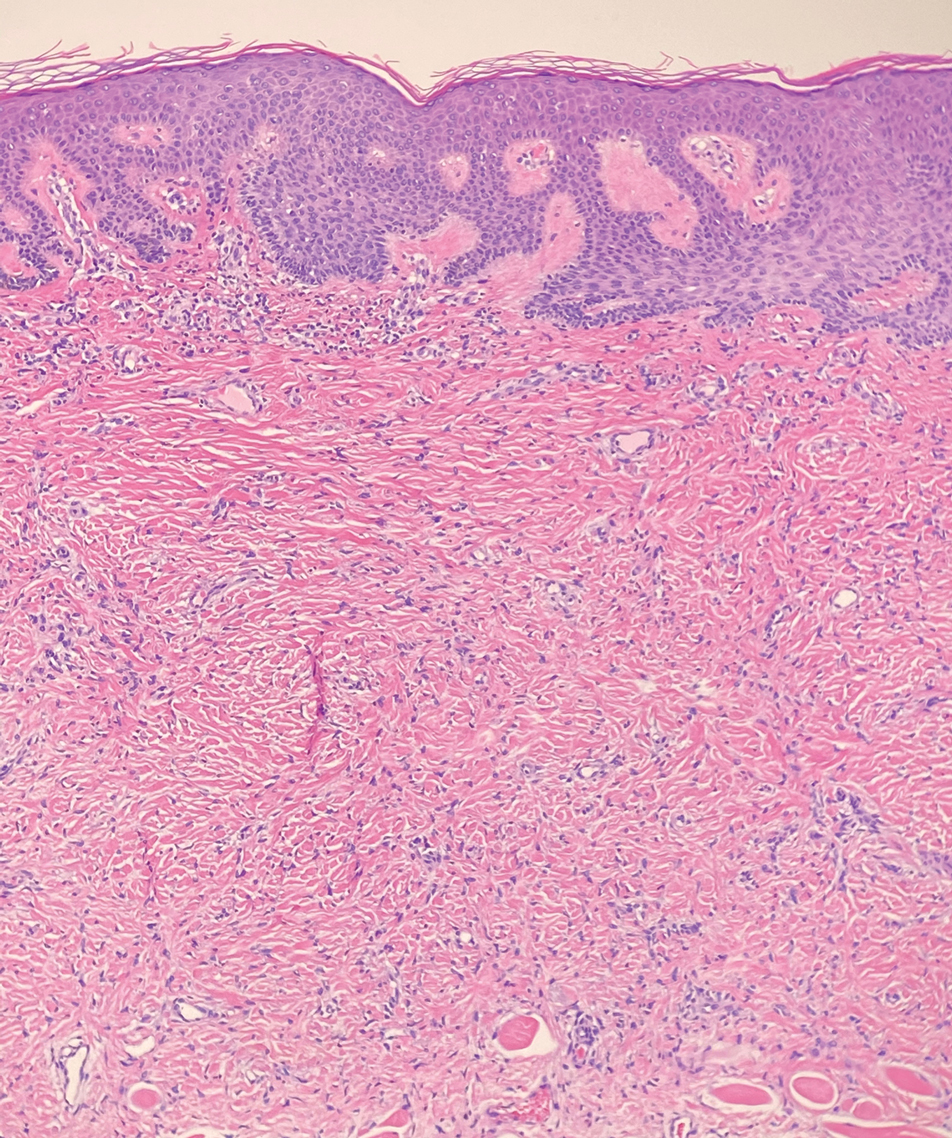

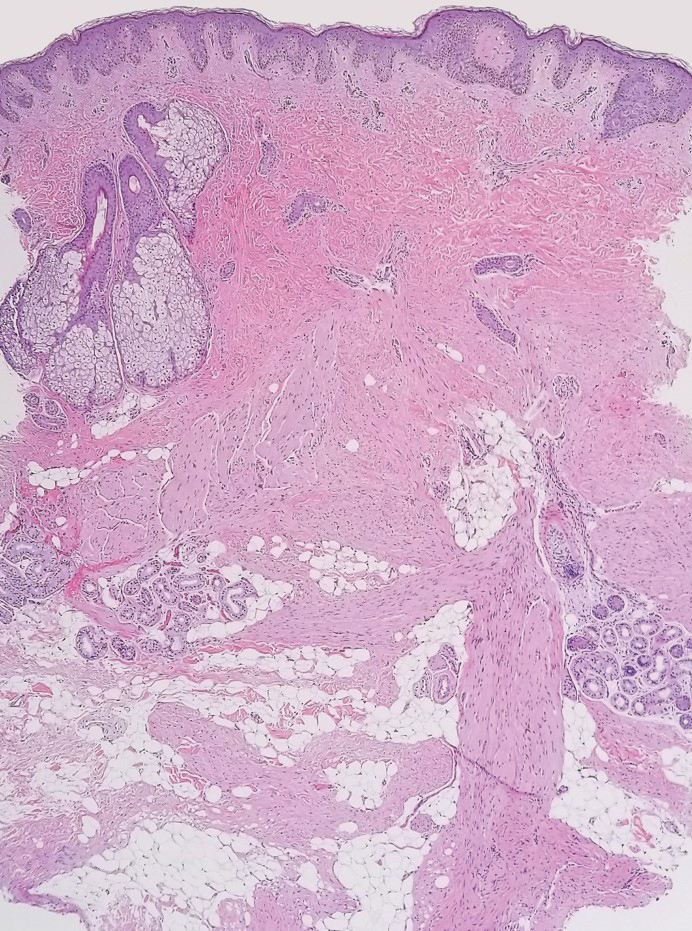

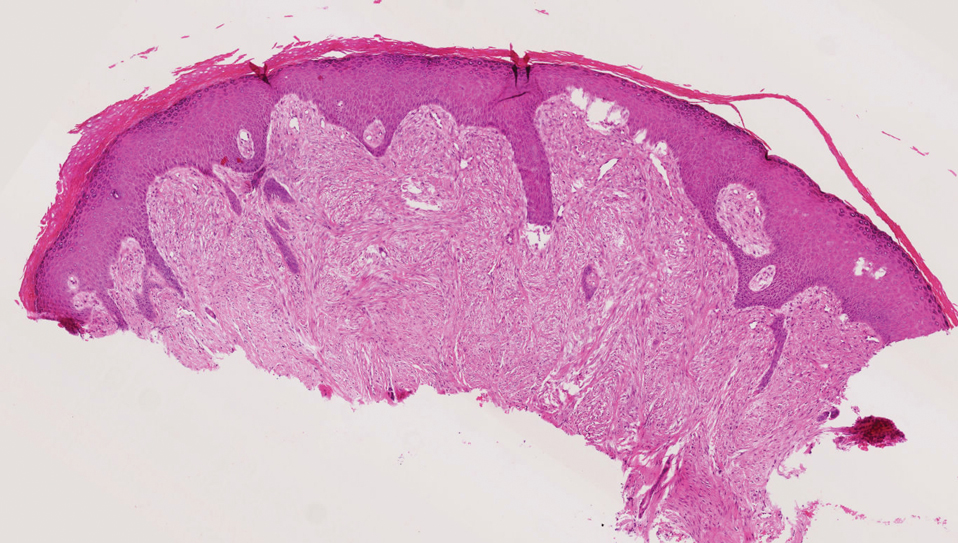

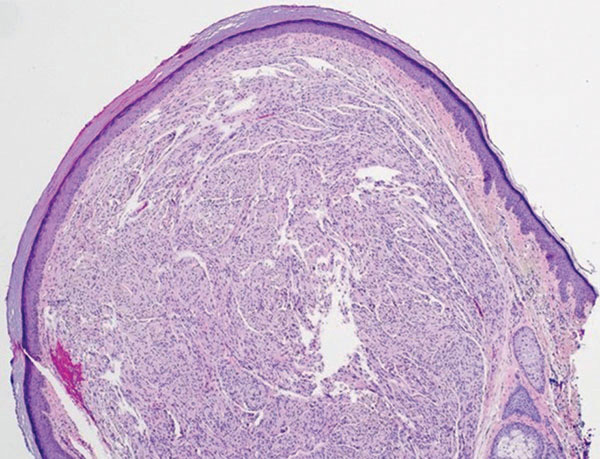

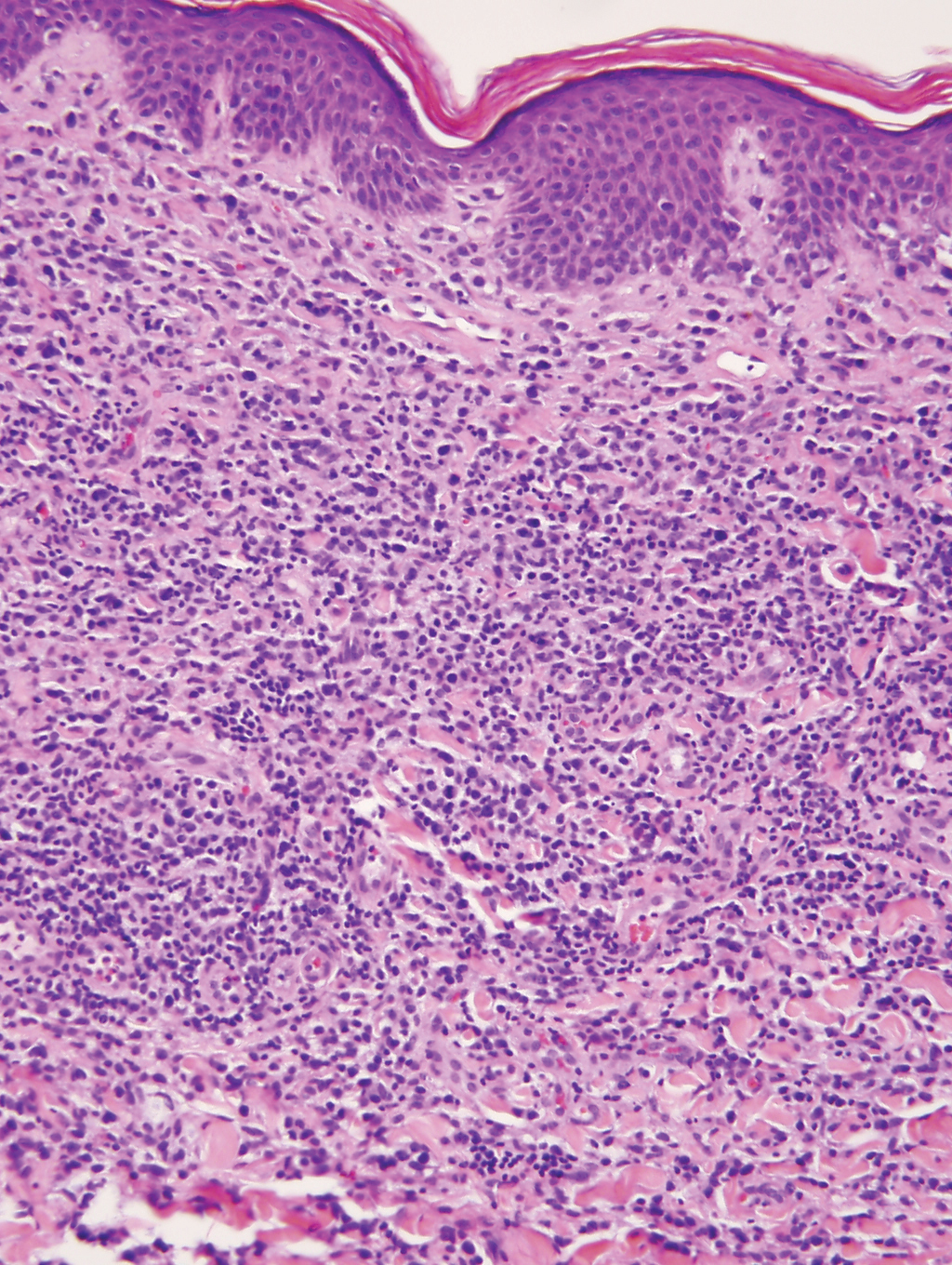

The differential diagnosis of PES includes poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (Figure 1 [inset]), melanoma, myoepithelial carcinoma, and epithelioid angiosarcoma. Primary squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva presents as an endophytic or exophytic mass with raised borders. Vulvar cancer is uncommon among gynecologic malignancies, with squamous cell carcinoma being the most commonly encountered.4 Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) is increasing in incidence, while the occurrence of invasive squamous cell carcinoma remains stable.5 Human papillomavirus–related VIN (usual-type VIN) is less likely to progress to squamous cell carcinoma than differentiated VIN (d-VIN), a dysplasia that is unrelated to human papillomavirus that frequently harbors p53 mutations.4 The presence of histologic epidermal involvement can help distinguish squamous cell carcinoma from PES (Figure 1). As opposed to PES, metastatic squamous cell carcinoma is characterized by intercellular bridges and often at least focal keratinization (Figure 1). Squamous cell carcinoma demonstrates positivity with p63 and p40 immunohistochemical stains, while PES rarely stains for either.6

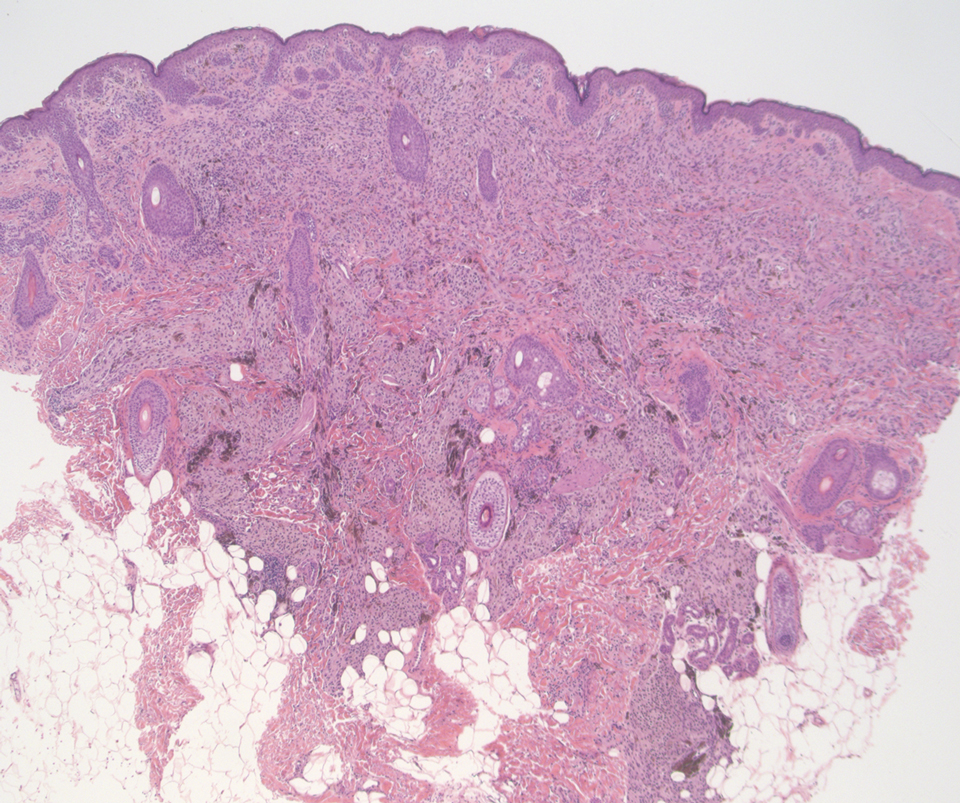

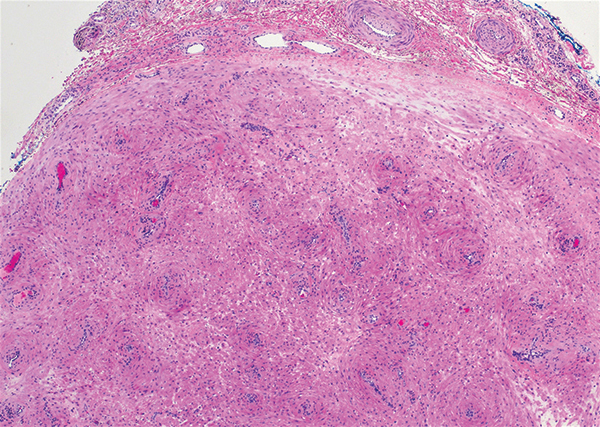

Melanoma is the second most common vulvar malignancy. Vulvar melanoma tends to occur in women of advanced age but has been reported in girls as young as 10 years old.7 There is some evidence that patients with lichen sclerosus may be at an increased risk for the development of vulvar melanoma.8 Compared to PES, primary vulvar melanoma usually demonstrates epidermal involvement as well as clinical findings of a pigmented lesion (Figure 2). A notable minority of vulvar melanomas are amelanotic.9 Melanoma may be distinguished from PES with a panel of melanocytic markers—human melanoma black 45, Melan-A, SRY-box transcription factor 10, S-100, and microphthalmia transcription factor—that rarely are expressed in the latter. Both PES and rhabdoid melanoma have eosinophilic and tinctorial cytoplasmic inclusions.10 Melanin pigment and more cohesive nests are helpful clues that may point to melanoma when present.

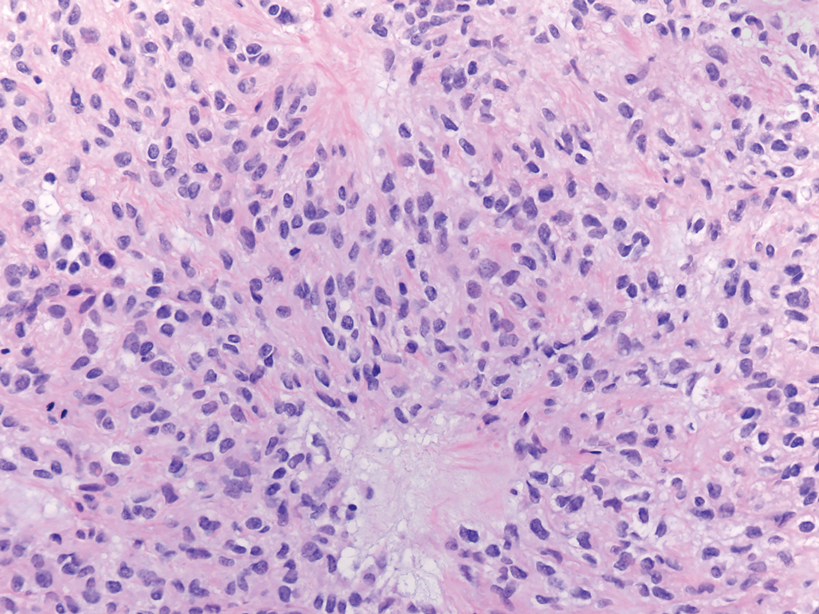

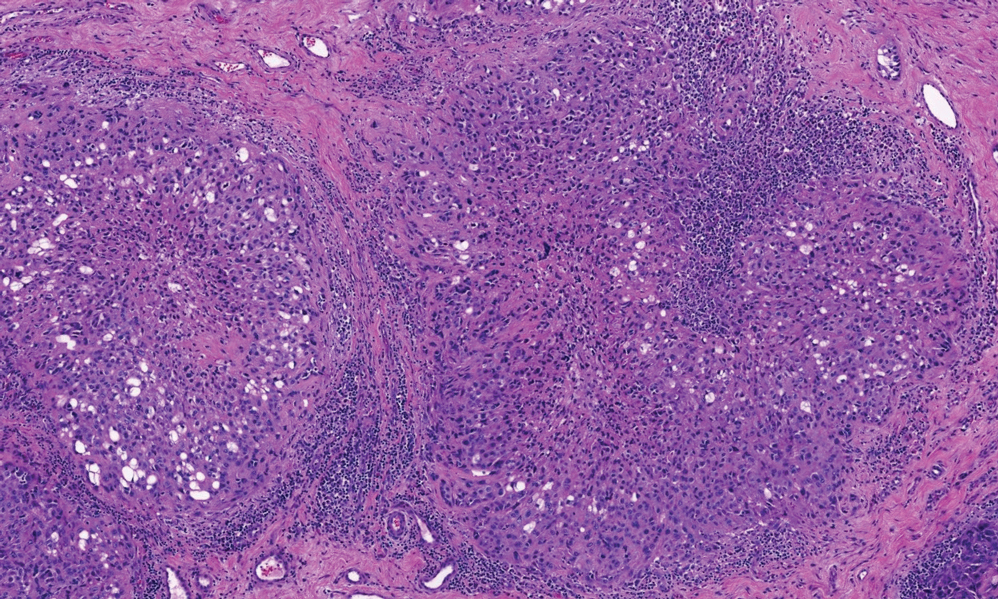

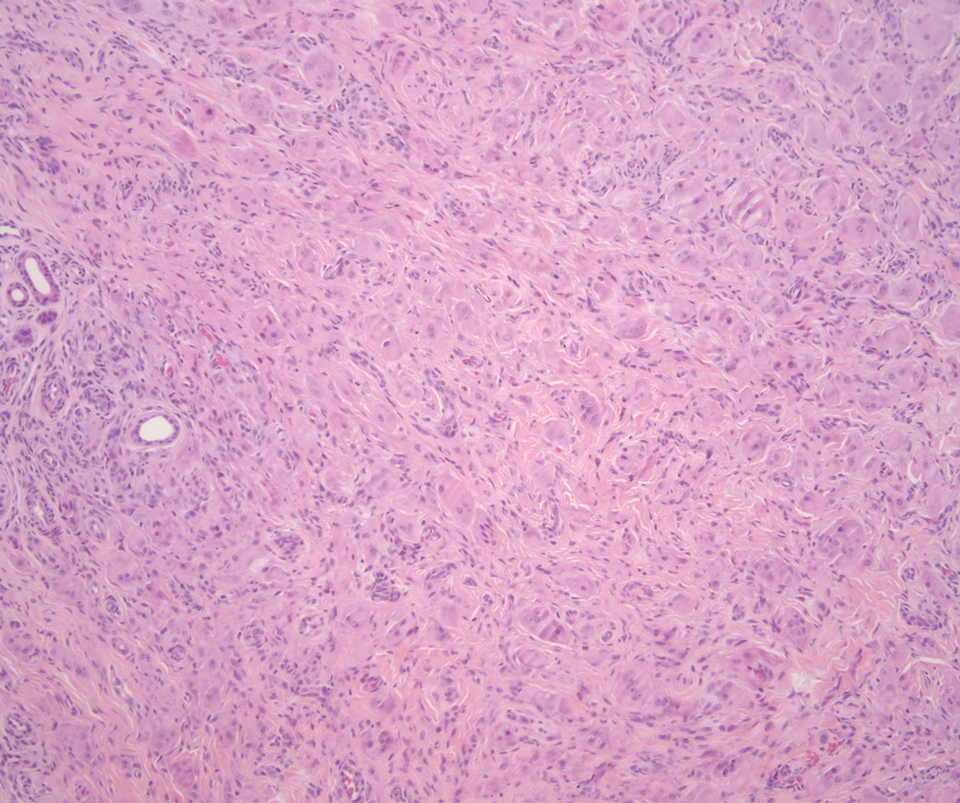

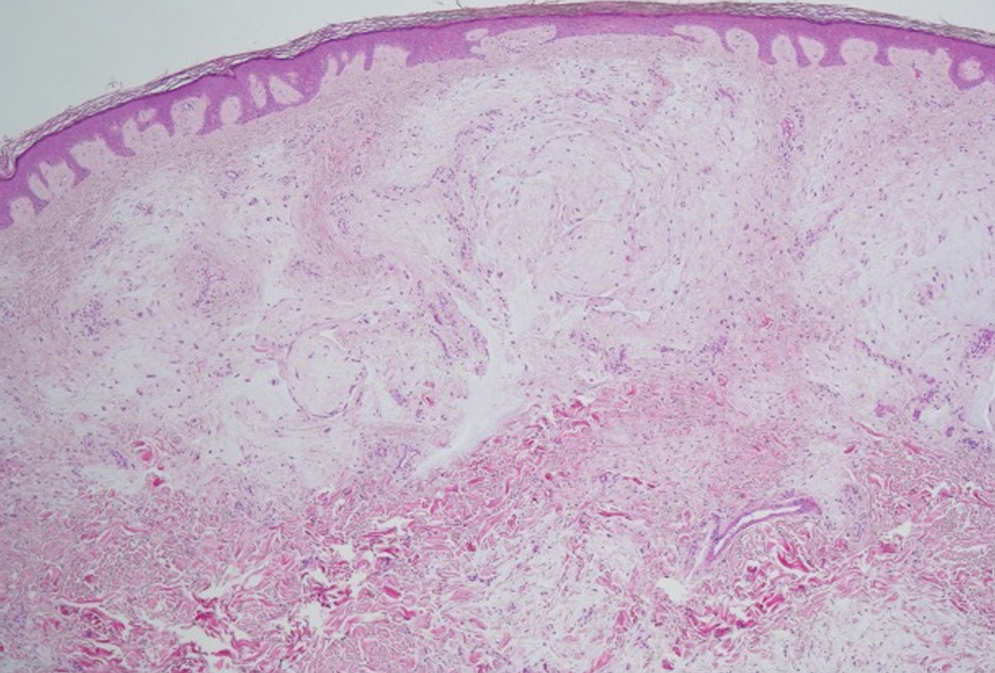

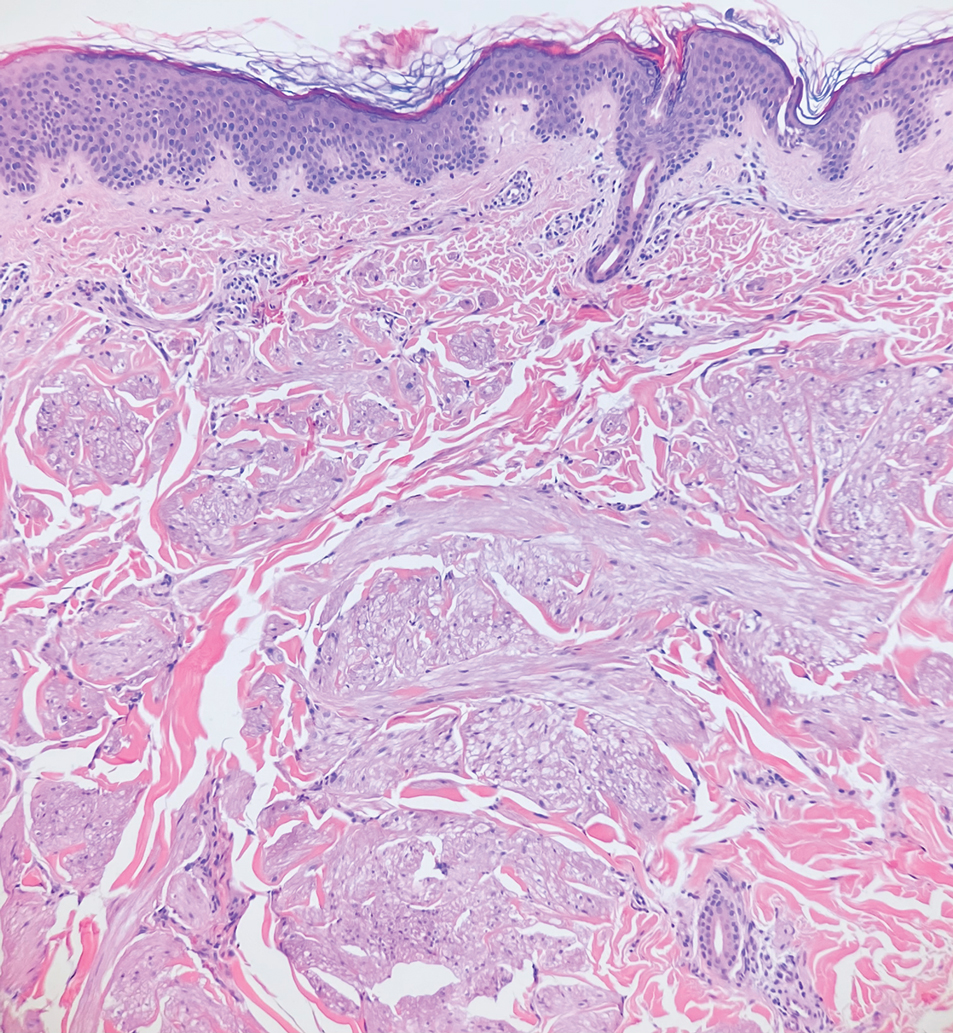

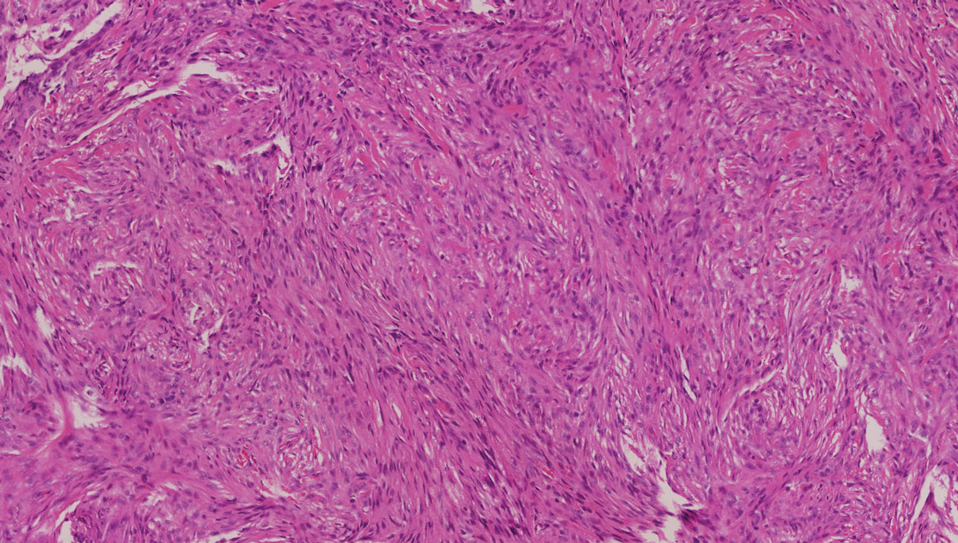

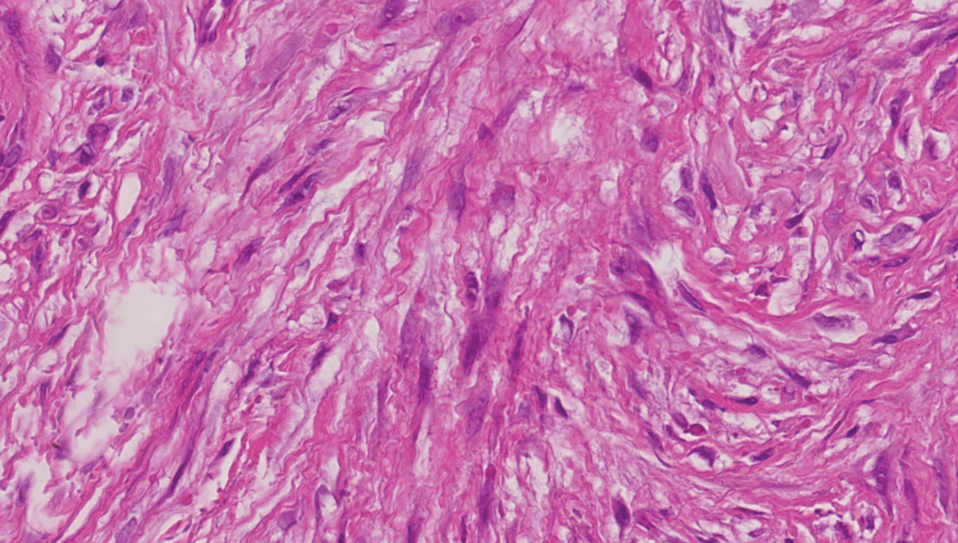

Myoepithelial carcinoma of the vulva is rare.11 Myoepithelial carcinoma of soft tissue is more aggressive than its benign counterpart, with up to a 50% metastasis rate.12 The presence of prominent corded or trabecular growth in a myxoid or hyaline background may point to the diagnosis (Figure 3). Similar to PES, myoepithelial carcinoma may lose expression of nuclear INI-1, while myoepithelial carcinoma is more likely to express S-100 and glial fibrillary acidic protein.13 Rearrangements of EWS RNA binding protein 1, EWSR1, have been found in half of myoepithelial neoplasms.12

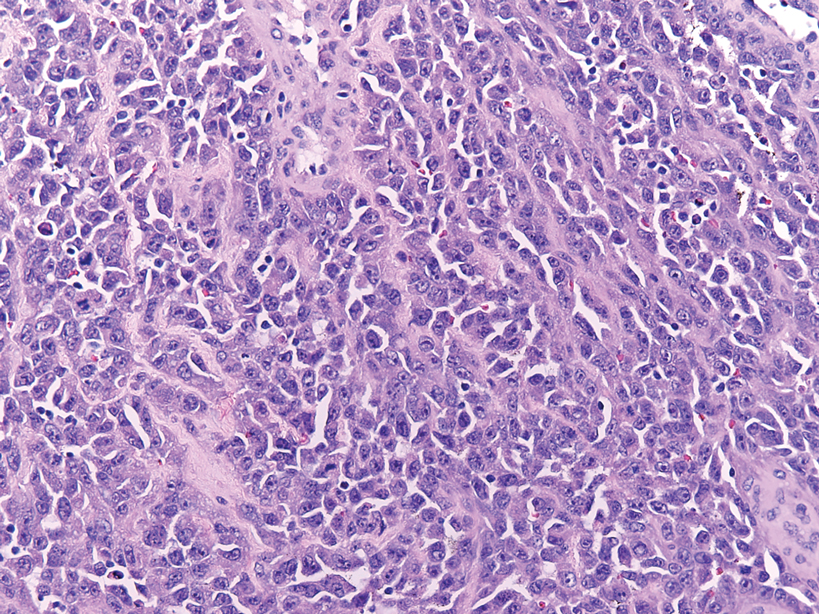

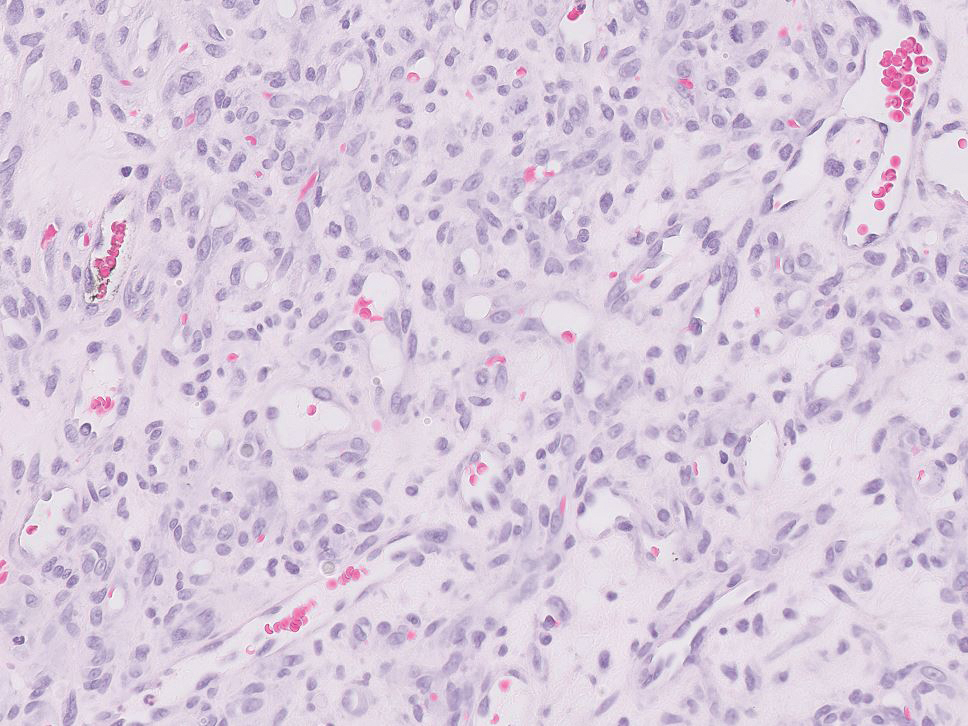

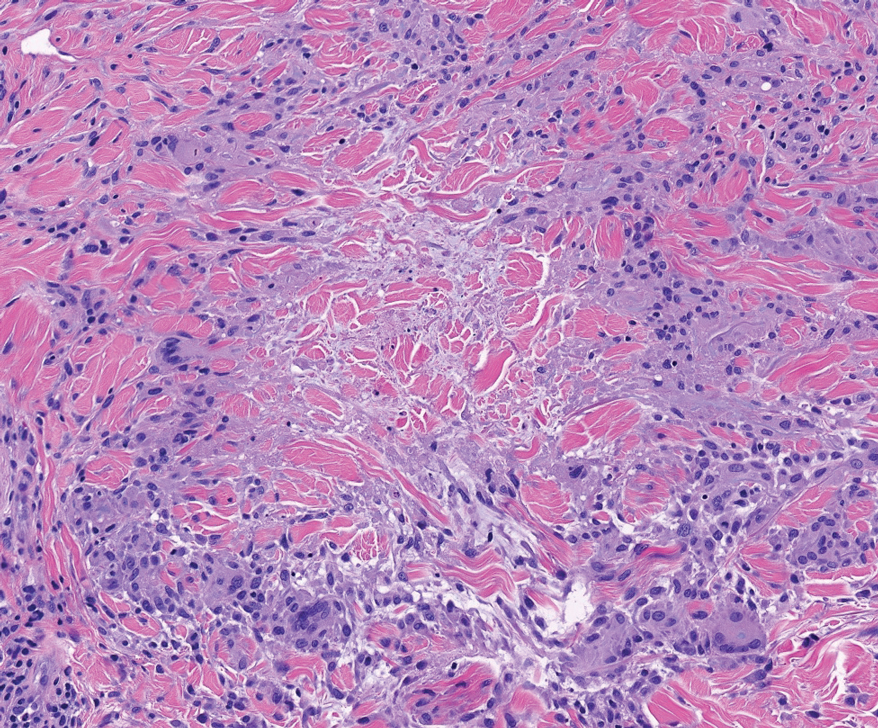

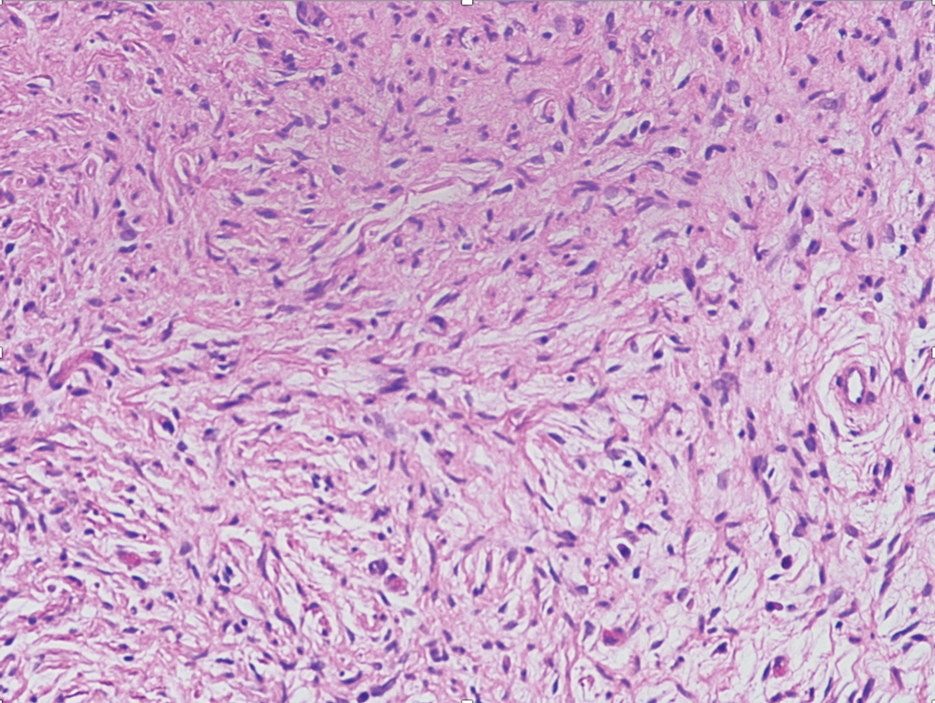

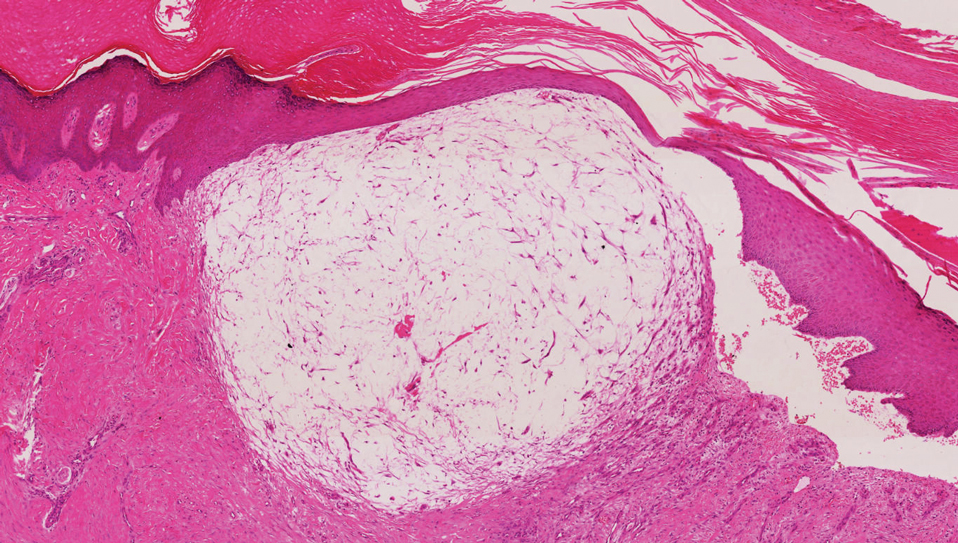

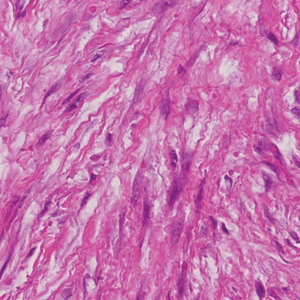

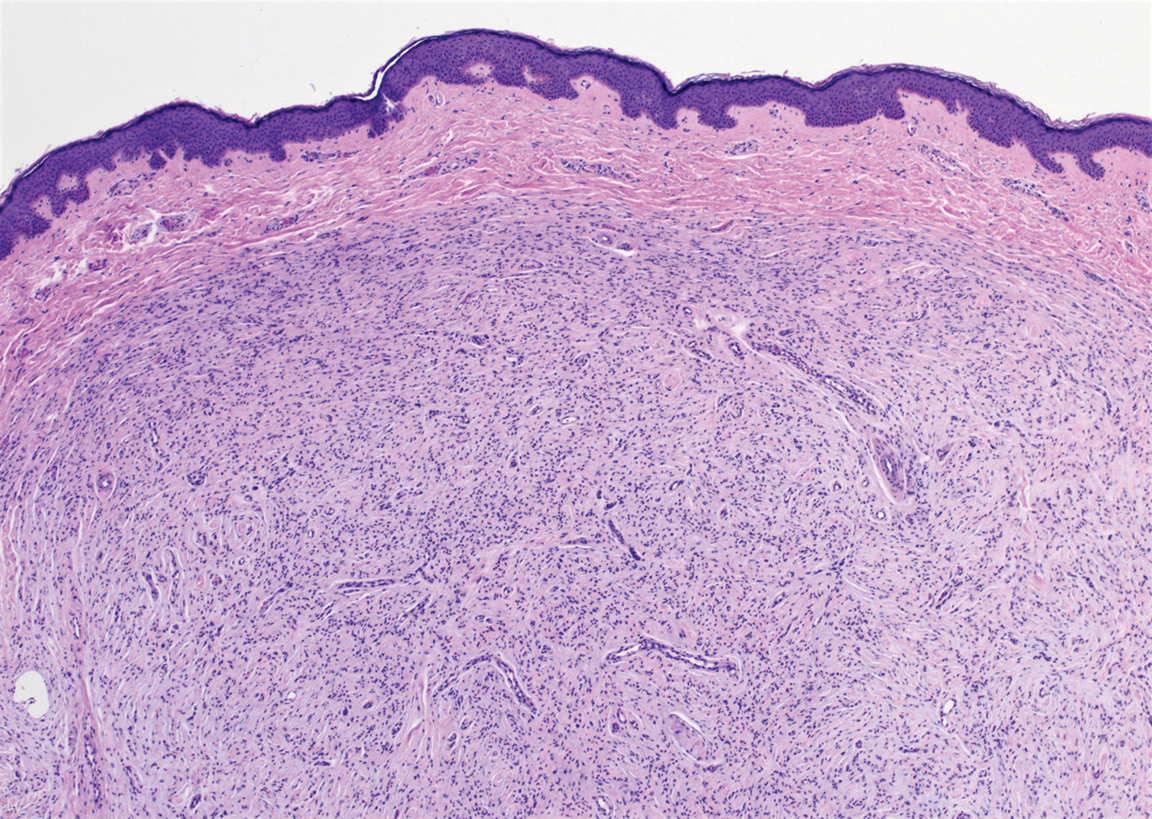

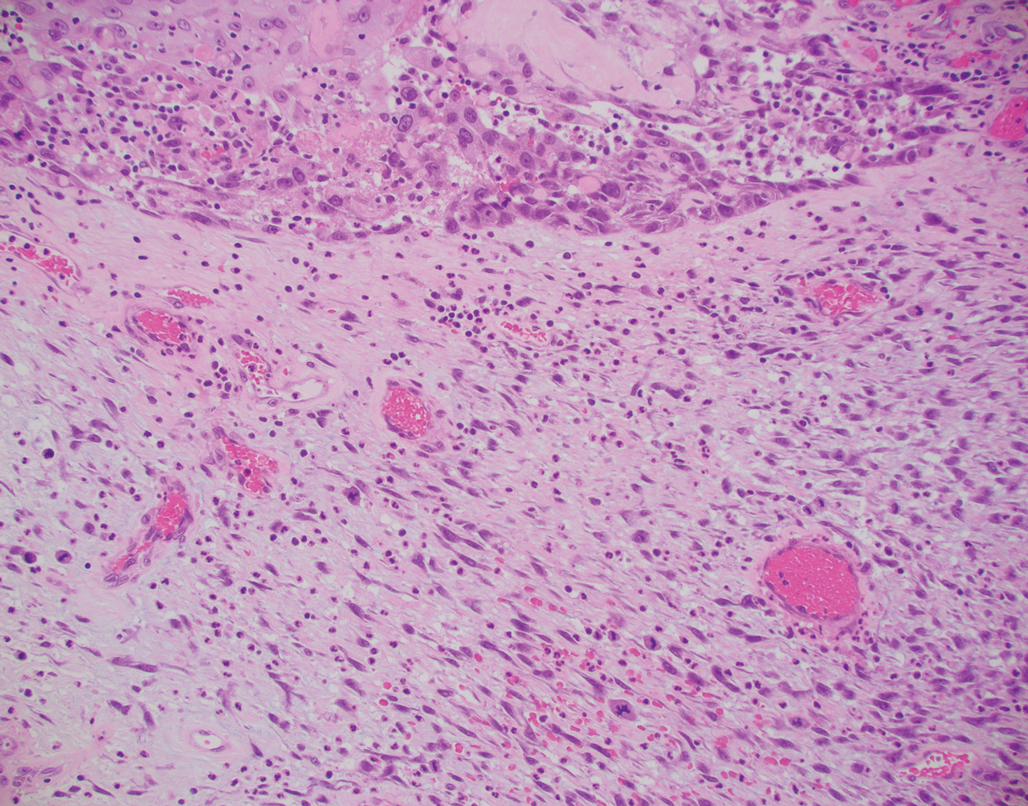

Angiosarcomas represent 5% of cutaneous sarcomas and rarely have been reported in the vulva, primarily occurring in the setting of long-standing lymphedema and radiation.14 Angiosarcoma more often occurs on the head and neck, breasts, or extremities. Additional risk factors for the development of angiosarcoma include toxin exposure (eg, polyvinyl chloride, thorium dioxide, arsenic), anabolic steroids, and filariasis, as well as genetic disorders (eg, neurofibromatosis type 1, BRCA gene mutations, Maffucci syndrome).15 Epithelioid angiosarcoma is an infiltrative tumor composed of irregular anastomosing vascular channels with extravasated erythrocytes (Figure 4). Solid growth and necrosis may be present in more aggressive tumors. The cells themselves are pleomorphic endothelial cells with vesicular chromatin and prominent nucleoli. Epithelioid angiosarcoma may resemble carcinoma and have focal keratin expression. However, the characteristic eosinophilic cytoplasm seen in PES should not be identified in epithelioid angiosarcoma. Unlike PES, epithelioid angiosarcoma is positive for CD31 and has retained expression for INI-1. Both angiosarcoma and proximal-type epithelioid sarcoma may express vascular markers CD34 and FLI-116; thus an expanded panel of immunohistochemical studies may be of utility.

- Guillou L, Wadden C, Coindre JM, et al. “Proximal-type” epithelioid sarcoma, a distinctive aggressive neoplasm showing rhabdoid features. clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural study of a series. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:130-146.

- Hasegawa T, Matsuno Y, Shimoda T, et al. Proximal-type epithelioid sarcoma: a clinicopathological study of 20 cases. Mod Pathol. 2001;14:655-663.

- Czarnecka AM, Sobczuk P, Kostrzanowski M, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma—from genetics to clinical practice. Cancers. 2020:12:2112.

- Hoang LH, Park KJ, Soslow RA, et al. Squamous precursor lesions of the vulva: current classification and diagnostic challenges. Pathology. 2016;48:291-302.

- Allbritton J. Vulvar neoplasms, benign and malignant. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2017;44:339-352.

- Laskin WB, Miettinen M. Epithelioid sarcoma: new insights based on an extended immunohistochemical analysis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:1161-1168.

- Boer FL, Eikelder MLGT, Kapitejn EH, et al. Vulvar malignant melanoma: pathogenesis, clinical behavior and management: review of the literature. Cancer Treat Rev. 2019;73:91-103.

- Hieta N, Rintala SKM, Soderlund J, et al. Association of vulvar melanoma with lichen sclerosus. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:339-340.

- Edwards L. Pigmented vulvar lesions. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:449-457.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA, Prenshaw KL, eds. Weedon's Skin Pathology. Elsevier Limited; 2021.

- Kyriazi MA, Carvounis EE, Kitsou M, et al. Myoepithelial carcinoma of the vulva mimicking Bartholin gland abscess in a pregnant woman: case report and review of literature. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2010:29:501-504.

- Jo VY, Fletcher CD. Myoepithelial neoplasma of soft tissue: an updated review of the clinicopathological, immunophenotypic, and genetic features. Head Neck Pathol. 2015;9:32-38.

- Rekhi B, Sable M, Jambhekar NA. Histopathological, immunohistochemical and molecular spectrum of myoepithelial tumours of soft tissues. Virchows Arch. 2012;461:687-697.

- Yost S, Bradish J, Grossheim L, et al. Epithelioid angiosarcoma of the vulva: a case report. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2017;21:91-93.

- Young RJ, Brown NJ, Reed MW, et al. Angiosarcoma. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:983-991.

- Stockman DL, Hornick JL, Deavers MT, et al. ERG and FLI1 protein expression in epithelioid sarcoma. Mod Pathol. 2014;27:496-501.

The Diagnosis: Proximal-Type Epithelioid Sarcoma

Proximal-type epithelioid sarcoma (PES) is a rare high-grade sarcoma of uncertain histogenesis that may present with a benign clinical appearance. Proximal-type epithelioid sarcoma peaks at 20 to 40 years of age and has a slight male predominance. This tumor exhibits aggressive behavior with both local recurrence and metastasis.1 The average overall survival is poor; however, tumor size less than 5 cm and complete excision with tumor-free margin status improves the prognosis.2 Proximal-type epithelioid sarcoma should not be confused with distal-type epithelioid sarcoma, which has a better prognosis and occurs in younger patients.1 Treatment of PES is wide excision, and chemotherapy trials with tazemetostat are ongoing.3

The deceptively banal clinical appearance of PES may delay appropriate diagnosis and treatment. Proximal-type epithelioid sarcoma often grows in sheets (quiz image [top] inset) and loose nests1 but also may take on a more corded appearance mimicking myoepithelial carcinoma. The cells themselves are plump dyscohesive epithelioid cells (quiz image [top]) with large nucleoli and eosinophilic cytoplasm or hyaline globules1 (quiz image [bottom]), but cells also may be focally spindled. Myxoid stroma, hemorrhage, and necrosis often are prominent features. Epithelioid sarcomas characteristically demonstrate positive immunostaining for both epithelial and mesenchymal markers (pan-cytokeratin and vimentin),1 with the majority having loss of expression of integrase interactor 1 (INI-1).2 Histology in this case was positive for cytokeratin monoclonal antibodies CAM5.2 and OSCAR, epithelial membrane antigen, and vimentin; it showed loss of INI-1 staining (quiz image [bottom]). Negative stains included S-100, p63, cytokeratins 7 and 20, CD34, CD31, ERG, glial fibrillary acidic protein, transducin-like enhancer of split 1, CD117, myogenin, synaptophysin, chromogranin, CD10, inhibin, CD99, and estrogen receptor.

The differential diagnosis of PES includes poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (Figure 1 [inset]), melanoma, myoepithelial carcinoma, and epithelioid angiosarcoma. Primary squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva presents as an endophytic or exophytic mass with raised borders. Vulvar cancer is uncommon among gynecologic malignancies, with squamous cell carcinoma being the most commonly encountered.4 Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) is increasing in incidence, while the occurrence of invasive squamous cell carcinoma remains stable.5 Human papillomavirus–related VIN (usual-type VIN) is less likely to progress to squamous cell carcinoma than differentiated VIN (d-VIN), a dysplasia that is unrelated to human papillomavirus that frequently harbors p53 mutations.4 The presence of histologic epidermal involvement can help distinguish squamous cell carcinoma from PES (Figure 1). As opposed to PES, metastatic squamous cell carcinoma is characterized by intercellular bridges and often at least focal keratinization (Figure 1). Squamous cell carcinoma demonstrates positivity with p63 and p40 immunohistochemical stains, while PES rarely stains for either.6

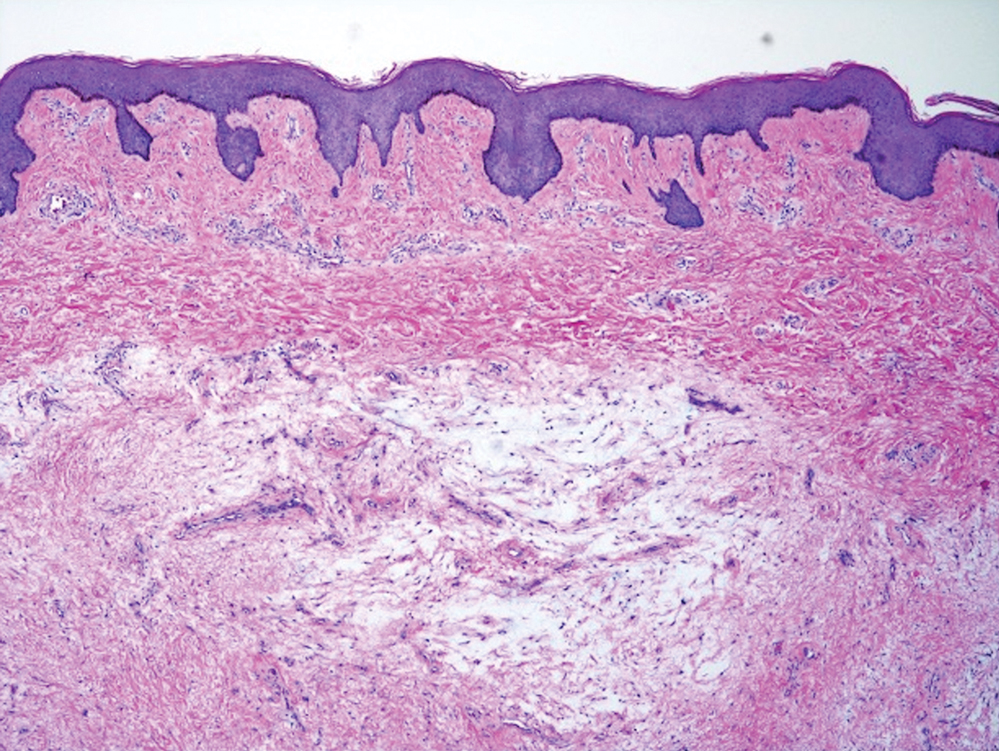

Melanoma is the second most common vulvar malignancy. Vulvar melanoma tends to occur in women of advanced age but has been reported in girls as young as 10 years old.7 There is some evidence that patients with lichen sclerosus may be at an increased risk for the development of vulvar melanoma.8 Compared to PES, primary vulvar melanoma usually demonstrates epidermal involvement as well as clinical findings of a pigmented lesion (Figure 2). A notable minority of vulvar melanomas are amelanotic.9 Melanoma may be distinguished from PES with a panel of melanocytic markers—human melanoma black 45, Melan-A, SRY-box transcription factor 10, S-100, and microphthalmia transcription factor—that rarely are expressed in the latter. Both PES and rhabdoid melanoma have eosinophilic and tinctorial cytoplasmic inclusions.10 Melanin pigment and more cohesive nests are helpful clues that may point to melanoma when present.

Myoepithelial carcinoma of the vulva is rare.11 Myoepithelial carcinoma of soft tissue is more aggressive than its benign counterpart, with up to a 50% metastasis rate.12 The presence of prominent corded or trabecular growth in a myxoid or hyaline background may point to the diagnosis (Figure 3). Similar to PES, myoepithelial carcinoma may lose expression of nuclear INI-1, while myoepithelial carcinoma is more likely to express S-100 and glial fibrillary acidic protein.13 Rearrangements of EWS RNA binding protein 1, EWSR1, have been found in half of myoepithelial neoplasms.12

Angiosarcomas represent 5% of cutaneous sarcomas and rarely have been reported in the vulva, primarily occurring in the setting of long-standing lymphedema and radiation.14 Angiosarcoma more often occurs on the head and neck, breasts, or extremities. Additional risk factors for the development of angiosarcoma include toxin exposure (eg, polyvinyl chloride, thorium dioxide, arsenic), anabolic steroids, and filariasis, as well as genetic disorders (eg, neurofibromatosis type 1, BRCA gene mutations, Maffucci syndrome).15 Epithelioid angiosarcoma is an infiltrative tumor composed of irregular anastomosing vascular channels with extravasated erythrocytes (Figure 4). Solid growth and necrosis may be present in more aggressive tumors. The cells themselves are pleomorphic endothelial cells with vesicular chromatin and prominent nucleoli. Epithelioid angiosarcoma may resemble carcinoma and have focal keratin expression. However, the characteristic eosinophilic cytoplasm seen in PES should not be identified in epithelioid angiosarcoma. Unlike PES, epithelioid angiosarcoma is positive for CD31 and has retained expression for INI-1. Both angiosarcoma and proximal-type epithelioid sarcoma may express vascular markers CD34 and FLI-116; thus an expanded panel of immunohistochemical studies may be of utility.

The Diagnosis: Proximal-Type Epithelioid Sarcoma

Proximal-type epithelioid sarcoma (PES) is a rare high-grade sarcoma of uncertain histogenesis that may present with a benign clinical appearance. Proximal-type epithelioid sarcoma peaks at 20 to 40 years of age and has a slight male predominance. This tumor exhibits aggressive behavior with both local recurrence and metastasis.1 The average overall survival is poor; however, tumor size less than 5 cm and complete excision with tumor-free margin status improves the prognosis.2 Proximal-type epithelioid sarcoma should not be confused with distal-type epithelioid sarcoma, which has a better prognosis and occurs in younger patients.1 Treatment of PES is wide excision, and chemotherapy trials with tazemetostat are ongoing.3

The deceptively banal clinical appearance of PES may delay appropriate diagnosis and treatment. Proximal-type epithelioid sarcoma often grows in sheets (quiz image [top] inset) and loose nests1 but also may take on a more corded appearance mimicking myoepithelial carcinoma. The cells themselves are plump dyscohesive epithelioid cells (quiz image [top]) with large nucleoli and eosinophilic cytoplasm or hyaline globules1 (quiz image [bottom]), but cells also may be focally spindled. Myxoid stroma, hemorrhage, and necrosis often are prominent features. Epithelioid sarcomas characteristically demonstrate positive immunostaining for both epithelial and mesenchymal markers (pan-cytokeratin and vimentin),1 with the majority having loss of expression of integrase interactor 1 (INI-1).2 Histology in this case was positive for cytokeratin monoclonal antibodies CAM5.2 and OSCAR, epithelial membrane antigen, and vimentin; it showed loss of INI-1 staining (quiz image [bottom]). Negative stains included S-100, p63, cytokeratins 7 and 20, CD34, CD31, ERG, glial fibrillary acidic protein, transducin-like enhancer of split 1, CD117, myogenin, synaptophysin, chromogranin, CD10, inhibin, CD99, and estrogen receptor.

The differential diagnosis of PES includes poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (Figure 1 [inset]), melanoma, myoepithelial carcinoma, and epithelioid angiosarcoma. Primary squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva presents as an endophytic or exophytic mass with raised borders. Vulvar cancer is uncommon among gynecologic malignancies, with squamous cell carcinoma being the most commonly encountered.4 Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) is increasing in incidence, while the occurrence of invasive squamous cell carcinoma remains stable.5 Human papillomavirus–related VIN (usual-type VIN) is less likely to progress to squamous cell carcinoma than differentiated VIN (d-VIN), a dysplasia that is unrelated to human papillomavirus that frequently harbors p53 mutations.4 The presence of histologic epidermal involvement can help distinguish squamous cell carcinoma from PES (Figure 1). As opposed to PES, metastatic squamous cell carcinoma is characterized by intercellular bridges and often at least focal keratinization (Figure 1). Squamous cell carcinoma demonstrates positivity with p63 and p40 immunohistochemical stains, while PES rarely stains for either.6

Melanoma is the second most common vulvar malignancy. Vulvar melanoma tends to occur in women of advanced age but has been reported in girls as young as 10 years old.7 There is some evidence that patients with lichen sclerosus may be at an increased risk for the development of vulvar melanoma.8 Compared to PES, primary vulvar melanoma usually demonstrates epidermal involvement as well as clinical findings of a pigmented lesion (Figure 2). A notable minority of vulvar melanomas are amelanotic.9 Melanoma may be distinguished from PES with a panel of melanocytic markers—human melanoma black 45, Melan-A, SRY-box transcription factor 10, S-100, and microphthalmia transcription factor—that rarely are expressed in the latter. Both PES and rhabdoid melanoma have eosinophilic and tinctorial cytoplasmic inclusions.10 Melanin pigment and more cohesive nests are helpful clues that may point to melanoma when present.

Myoepithelial carcinoma of the vulva is rare.11 Myoepithelial carcinoma of soft tissue is more aggressive than its benign counterpart, with up to a 50% metastasis rate.12 The presence of prominent corded or trabecular growth in a myxoid or hyaline background may point to the diagnosis (Figure 3). Similar to PES, myoepithelial carcinoma may lose expression of nuclear INI-1, while myoepithelial carcinoma is more likely to express S-100 and glial fibrillary acidic protein.13 Rearrangements of EWS RNA binding protein 1, EWSR1, have been found in half of myoepithelial neoplasms.12

Angiosarcomas represent 5% of cutaneous sarcomas and rarely have been reported in the vulva, primarily occurring in the setting of long-standing lymphedema and radiation.14 Angiosarcoma more often occurs on the head and neck, breasts, or extremities. Additional risk factors for the development of angiosarcoma include toxin exposure (eg, polyvinyl chloride, thorium dioxide, arsenic), anabolic steroids, and filariasis, as well as genetic disorders (eg, neurofibromatosis type 1, BRCA gene mutations, Maffucci syndrome).15 Epithelioid angiosarcoma is an infiltrative tumor composed of irregular anastomosing vascular channels with extravasated erythrocytes (Figure 4). Solid growth and necrosis may be present in more aggressive tumors. The cells themselves are pleomorphic endothelial cells with vesicular chromatin and prominent nucleoli. Epithelioid angiosarcoma may resemble carcinoma and have focal keratin expression. However, the characteristic eosinophilic cytoplasm seen in PES should not be identified in epithelioid angiosarcoma. Unlike PES, epithelioid angiosarcoma is positive for CD31 and has retained expression for INI-1. Both angiosarcoma and proximal-type epithelioid sarcoma may express vascular markers CD34 and FLI-116; thus an expanded panel of immunohistochemical studies may be of utility.

- Guillou L, Wadden C, Coindre JM, et al. “Proximal-type” epithelioid sarcoma, a distinctive aggressive neoplasm showing rhabdoid features. clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural study of a series. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:130-146.

- Hasegawa T, Matsuno Y, Shimoda T, et al. Proximal-type epithelioid sarcoma: a clinicopathological study of 20 cases. Mod Pathol. 2001;14:655-663.

- Czarnecka AM, Sobczuk P, Kostrzanowski M, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma—from genetics to clinical practice. Cancers. 2020:12:2112.

- Hoang LH, Park KJ, Soslow RA, et al. Squamous precursor lesions of the vulva: current classification and diagnostic challenges. Pathology. 2016;48:291-302.

- Allbritton J. Vulvar neoplasms, benign and malignant. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2017;44:339-352.

- Laskin WB, Miettinen M. Epithelioid sarcoma: new insights based on an extended immunohistochemical analysis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:1161-1168.

- Boer FL, Eikelder MLGT, Kapitejn EH, et al. Vulvar malignant melanoma: pathogenesis, clinical behavior and management: review of the literature. Cancer Treat Rev. 2019;73:91-103.

- Hieta N, Rintala SKM, Soderlund J, et al. Association of vulvar melanoma with lichen sclerosus. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:339-340.

- Edwards L. Pigmented vulvar lesions. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:449-457.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA, Prenshaw KL, eds. Weedon's Skin Pathology. Elsevier Limited; 2021.

- Kyriazi MA, Carvounis EE, Kitsou M, et al. Myoepithelial carcinoma of the vulva mimicking Bartholin gland abscess in a pregnant woman: case report and review of literature. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2010:29:501-504.

- Jo VY, Fletcher CD. Myoepithelial neoplasma of soft tissue: an updated review of the clinicopathological, immunophenotypic, and genetic features. Head Neck Pathol. 2015;9:32-38.

- Rekhi B, Sable M, Jambhekar NA. Histopathological, immunohistochemical and molecular spectrum of myoepithelial tumours of soft tissues. Virchows Arch. 2012;461:687-697.

- Yost S, Bradish J, Grossheim L, et al. Epithelioid angiosarcoma of the vulva: a case report. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2017;21:91-93.

- Young RJ, Brown NJ, Reed MW, et al. Angiosarcoma. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:983-991.

- Stockman DL, Hornick JL, Deavers MT, et al. ERG and FLI1 protein expression in epithelioid sarcoma. Mod Pathol. 2014;27:496-501.

- Guillou L, Wadden C, Coindre JM, et al. “Proximal-type” epithelioid sarcoma, a distinctive aggressive neoplasm showing rhabdoid features. clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural study of a series. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:130-146.

- Hasegawa T, Matsuno Y, Shimoda T, et al. Proximal-type epithelioid sarcoma: a clinicopathological study of 20 cases. Mod Pathol. 2001;14:655-663.

- Czarnecka AM, Sobczuk P, Kostrzanowski M, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma—from genetics to clinical practice. Cancers. 2020:12:2112.

- Hoang LH, Park KJ, Soslow RA, et al. Squamous precursor lesions of the vulva: current classification and diagnostic challenges. Pathology. 2016;48:291-302.

- Allbritton J. Vulvar neoplasms, benign and malignant. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2017;44:339-352.

- Laskin WB, Miettinen M. Epithelioid sarcoma: new insights based on an extended immunohistochemical analysis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:1161-1168.

- Boer FL, Eikelder MLGT, Kapitejn EH, et al. Vulvar malignant melanoma: pathogenesis, clinical behavior and management: review of the literature. Cancer Treat Rev. 2019;73:91-103.

- Hieta N, Rintala SKM, Soderlund J, et al. Association of vulvar melanoma with lichen sclerosus. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:339-340.

- Edwards L. Pigmented vulvar lesions. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:449-457.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA, Prenshaw KL, eds. Weedon's Skin Pathology. Elsevier Limited; 2021.

- Kyriazi MA, Carvounis EE, Kitsou M, et al. Myoepithelial carcinoma of the vulva mimicking Bartholin gland abscess in a pregnant woman: case report and review of literature. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2010:29:501-504.

- Jo VY, Fletcher CD. Myoepithelial neoplasma of soft tissue: an updated review of the clinicopathological, immunophenotypic, and genetic features. Head Neck Pathol. 2015;9:32-38.

- Rekhi B, Sable M, Jambhekar NA. Histopathological, immunohistochemical and molecular spectrum of myoepithelial tumours of soft tissues. Virchows Arch. 2012;461:687-697.

- Yost S, Bradish J, Grossheim L, et al. Epithelioid angiosarcoma of the vulva: a case report. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2017;21:91-93.

- Young RJ, Brown NJ, Reed MW, et al. Angiosarcoma. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:983-991.

- Stockman DL, Hornick JL, Deavers MT, et al. ERG and FLI1 protein expression in epithelioid sarcoma. Mod Pathol. 2014;27:496-501.

A 45-year-old woman with no notable medical history presented with a small nodule in the left pubic region lateral to the left labia majora. The lesion grew to 8 cm over the course of several months, and she underwent a simple excision for what clinically appeared to be a cyst.

Bleeding Nodule on the Lip

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is a common genitourinary system malignancy with incidence peaking between 50 and 70 years of age and a male predominance.1 The clear cell variant is the most common subtype of RCC, accounting for 70% to 75% of all cases. It is known to be a highly aggressive malignancy that frequently metastasizes to the lungs, lymphatics, bones, liver, and brain.2,3 Approximately 20% to 50% of patients with RCC eventually will develop metastasis after nephrectomy.4 Survival with metastatic RCC to any site typically is in the range of 10 to 22 months.5,6 Cutaneous metastases of RCC rarely have been reported in the literature (3%–6% of cases7) and most commonly are found on the scalp, followed by the chest or abdomen. 8 Cutaneous metastases generally are regarded as a late manifestation of the disease with a very poor prognosis. 9 It is unusual to identify cutaneous RCC metastasis without known RCC or other symptoms consistent with advanced RCC, such as hematuria or abdominal/flank pain. Renal cell carcinoma accounts for an estimated 6% to 7% of all cutaneous metastatic lesions.10 Cutaneous metastatic lesions of RCC often are solitary and grow rapidly, with the clinical appearance of an erythematous or violaceous, nodular, highly vascular, and often hemorrhagic growth.9,11,12

Following the histologic diagnosis of metastatic clear cell RCC, our patient was referred to medical oncology for further workup. Magnetic resonance imaging and a positron emission tomography scan demonstrated widespread disease with a 7-cm left renal mass, liver and lung metastases, and bilateral mediastinal lymphadenopathy. The patient was started on combination immunotherapy as a palliative treatment given the widespread disease.

Histologically, clear cell RCC is characterized by lipid and glycogen-rich cells with ample cytoplasm and a well-developed vascular network, which often is thin walled with a chicken wire–like architecture. Metastatic clear cell RCC tumor cells may form glandular, acinar, or papillary structures with variable lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrates and abundant capillary formation. Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells should demonstrate positivity for paired box gene 8, PAX8, and RCC marker antigen.13 Vimentin and carcinoembryonic antigen may be utilized to distinguish from hidradenoma as carcinoembryonic antigen will be positive in hidradenoma and vimentin will be negative.14 Renal cell carcinoma also has a common molecular signature of von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor gene inactivation as well as upregulation of hypoxia inducible factor and vascular endothelial growth factor.15

Balloon cell nevi often clinically present in young patients as bicolored nevi that sometimes are polypoid or verrucous in appearance with central yellow globules surrounded by a peripheral reticular pattern on dermoscopy. Histologically, balloon cell nevi are characterized by large cells with small, round, centrally located basophilic nuclei and clear foamy cytoplasm (Figure 1), which are thought to be formed by progressive vacuolization of melanocytes due to the enlargement and disintegration of melanosomes. This ballooning change reflects an seen in malignant melanoma, in which case nuclear pleomorphism, atypia, and increased mitotic activity also are observed. The prominent vascular network characteristic of RCC typically is not present.16

Clear cell hidradenomas are benign skin appendage tumors that often present as small, firm, solitary dermal nodules that may extend into the subcutaneous fat. They have a predilection for the head, face, and arms and demonstrate 2 predominant cell types, including a polyhedral cell with a rounded nucleus and slightly basophilic cytoplasm as well as a round cell with clear cytoplasm and bland nuclei (Figure 2). The latter cell type is less common, representing the predominant cell type in less than one-third of hidradenomas, and can present a diagnostic quandary based on histologic similarity to other clear cell neoplasms. The clear cells contain glycogen but no lipid. Ductlike structures often are present, and the intervening stroma varies from delicate vascularized cords of fibrous tissue to dense hyalinized collagen. Immunohistochemistry may be required for definitive diagnosis, and clear cell hidradenomas should react with monoclonal antibodies that label both eccrine and apocrine secretory elements, such as cytokeratins 6/18, 7, and 8/18.17

Pyogenic granulomas (also referred to as lobular capillary hemangiomas) are common and present clinically as rapidly growing, polypoid, red masses surrounded by a thickened epidermis that often are found on the fingers or lips. This entity is benign and often regresses spontaneously. Histologically, pyogenic granulomas are characterized by a lobular pattern of vascular proliferation associated with edema and inflammation resembling granulation tissue, with acanthosis and hyperkeratosis at the edges of the lesion (Figure 3).18

Sebaceous carcinoma is a locally aggressive malignant neoplasm arising from the cells of the sebaceous glands and occurring most commonly in the periorbital area. This neoplasm most often affects older adults, with a mean age at diagnosis of 63 to 77 years. It commonly presents as a solitary nodule with yellowish discoloration and madarosis, which is a key distinguishing feature to differentiate this entity from a chalazion or hordeolum. Histologically, sebaceous carcinoma is a dermal-based infiltrative, nodular tumor with varying degrees of clear cell changes—well-differentiated tumors show more clear cell change as compared to more poorly differentiated variants—along with basaloid or squamous features and abundant mitotic activity (Figure 4), which may be useful in distinguishing it from the other entities in the clear cell neoplasm differential.19-22

- Alves de Paula T, Lopes da Silva P, Sueth Berriel LG. Renal cell carcinoma with cutaneous metastasis: case report. J Bras Nefrol. 2010;32:213-215.

- Amaadour L, Atreche L, Azegrar M, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of renal cell carcinoma: a case report. J Cancer Ther. 2017;8:603-607.

- Weiss L, Harlos JP, Torhorst J, et al. Metastatic patterns of renal carcinoma: an analysis of 687 necropsies. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1988;114:605-612.

- Flamigan RC, Campbell SC, Clark JI, et al. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2003;4:385-390.

- Motzer RJ, Bacik J, Schwarz LH, et al. Prognostic factors for survival in previously treated patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:453-463.

- Heng DY, Xie W, Regan MM, et al. Prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with vascular endothelial growth factor–targeted agents: results from a large, multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5694-5799.

- Smyth LG, Rowan GC, David MQ. Renal cell carcinoma presenting as an ominous metachronous scalp metastasis. Can Urol Assoc J. 2010;4:E64-E66.

- Dorairajan LN, Hemal AK, Aron M, et al. Cutaneous metastases in renal cell carcinoma. Urol Int. 1999;63:164-167.

- Koga S, Tsuda S, Nishikido M, et al. Renal cell carcinoma metastatic to the skin. Anticancer Res. 2000;20:1939-1940.

- Krathen RA, Orengo IF, Rosen T. Cutaneous metastasis: a metaanalysis of the data. South Med J. 2003;96:164-167.

- Amano Y, Ohni S, Ishige T, et al. A case of cutaneous metastasis from a clear cell renal cell carcinoma with an eosinophilic cell component to the submandibular region. J Nihon Univ Med Assoc. 2015;74:73-77.

- Arrabal-Polo MA, Arias-Santiago SA, Aneiros-Fernandez J, et al. Cutaneous metastases in renal cell carcinoma: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:7948.

- Sangoi AR, Karamchandani J, Kim J, et al. The use of immunohistochemistry in the diagnosis of metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma: a review of PAX-8, PAX-2, hKIM-1, RCCma, and CD10. Adv Anat Pathol. 2010;17:377-393.

- Velez MJ, Thomas CL, Stratton J, et al. The utility of using immunohistochemistry in the differentiation of metastatic, cutaneous clear cell renal cell carcinoma and clear cell hidradenoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:612-615.

- Nezami BG, MacLennan G. Clear cell. PathologyOutlines website. Published April 20, 2021. Updated March 2, 2022. Accessed April 22, 2022. https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/kidneytumormalignantrccclear.html

- Dhaille F, Courville P, Joly P, et al. Balloon cell nevus: histologic and dermoscopic features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:E55-E56.

- Volmar KE, Cummings TJ, Wang WH, et al. Clear cell hidradenoma: a mimic of metastatic clear cell tumors. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129:E113-E116.

- Hale CS. Capillary/pyogenic granuloma. Pathology Outlines website. Published August 1, 2012. Updated March 10, 2022. Accessed April 20, 2022. https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/skintumornonmelanocyticpyogenicgranuloma.html

- Zada S, Lee BA. Sebaceous carcinoma. Pathology Outlines website. Published August 11, 2021. Accessed April 20, 2022. https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/skintumornonmelanocyticsebaceouscarcinoma.html

- Kahana A, Pribila, JT, Nelson CC, et al. Sebaceous cell carcinoma. In: Levin LA, Albert DM, eds. Ocular Disease: Mechanisms and Management. Elsevier; 2010:396-407.

- Wick MR. Cutaneous tumors and pseudotumors of the head and neck. In: Gnepp DR, ed. Diagnostic Surgical Pathology of the Head and Neck. 2nd ed. Saunders Elsevier; 2009:975-1068.

- Cassarino DS, Dadras SS, Lindberg MR, et al. Sebaceous carcinoma. In: Cassarino DS, Dadras SS, Lindberg MR, et al, eds. Diagnostic Pathology: Neoplastic Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2017:174-179.

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is a common genitourinary system malignancy with incidence peaking between 50 and 70 years of age and a male predominance.1 The clear cell variant is the most common subtype of RCC, accounting for 70% to 75% of all cases. It is known to be a highly aggressive malignancy that frequently metastasizes to the lungs, lymphatics, bones, liver, and brain.2,3 Approximately 20% to 50% of patients with RCC eventually will develop metastasis after nephrectomy.4 Survival with metastatic RCC to any site typically is in the range of 10 to 22 months.5,6 Cutaneous metastases of RCC rarely have been reported in the literature (3%–6% of cases7) and most commonly are found on the scalp, followed by the chest or abdomen. 8 Cutaneous metastases generally are regarded as a late manifestation of the disease with a very poor prognosis. 9 It is unusual to identify cutaneous RCC metastasis without known RCC or other symptoms consistent with advanced RCC, such as hematuria or abdominal/flank pain. Renal cell carcinoma accounts for an estimated 6% to 7% of all cutaneous metastatic lesions.10 Cutaneous metastatic lesions of RCC often are solitary and grow rapidly, with the clinical appearance of an erythematous or violaceous, nodular, highly vascular, and often hemorrhagic growth.9,11,12

Following the histologic diagnosis of metastatic clear cell RCC, our patient was referred to medical oncology for further workup. Magnetic resonance imaging and a positron emission tomography scan demonstrated widespread disease with a 7-cm left renal mass, liver and lung metastases, and bilateral mediastinal lymphadenopathy. The patient was started on combination immunotherapy as a palliative treatment given the widespread disease.

Histologically, clear cell RCC is characterized by lipid and glycogen-rich cells with ample cytoplasm and a well-developed vascular network, which often is thin walled with a chicken wire–like architecture. Metastatic clear cell RCC tumor cells may form glandular, acinar, or papillary structures with variable lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrates and abundant capillary formation. Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells should demonstrate positivity for paired box gene 8, PAX8, and RCC marker antigen.13 Vimentin and carcinoembryonic antigen may be utilized to distinguish from hidradenoma as carcinoembryonic antigen will be positive in hidradenoma and vimentin will be negative.14 Renal cell carcinoma also has a common molecular signature of von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor gene inactivation as well as upregulation of hypoxia inducible factor and vascular endothelial growth factor.15

Balloon cell nevi often clinically present in young patients as bicolored nevi that sometimes are polypoid or verrucous in appearance with central yellow globules surrounded by a peripheral reticular pattern on dermoscopy. Histologically, balloon cell nevi are characterized by large cells with small, round, centrally located basophilic nuclei and clear foamy cytoplasm (Figure 1), which are thought to be formed by progressive vacuolization of melanocytes due to the enlargement and disintegration of melanosomes. This ballooning change reflects an seen in malignant melanoma, in which case nuclear pleomorphism, atypia, and increased mitotic activity also are observed. The prominent vascular network characteristic of RCC typically is not present.16

Clear cell hidradenomas are benign skin appendage tumors that often present as small, firm, solitary dermal nodules that may extend into the subcutaneous fat. They have a predilection for the head, face, and arms and demonstrate 2 predominant cell types, including a polyhedral cell with a rounded nucleus and slightly basophilic cytoplasm as well as a round cell with clear cytoplasm and bland nuclei (Figure 2). The latter cell type is less common, representing the predominant cell type in less than one-third of hidradenomas, and can present a diagnostic quandary based on histologic similarity to other clear cell neoplasms. The clear cells contain glycogen but no lipid. Ductlike structures often are present, and the intervening stroma varies from delicate vascularized cords of fibrous tissue to dense hyalinized collagen. Immunohistochemistry may be required for definitive diagnosis, and clear cell hidradenomas should react with monoclonal antibodies that label both eccrine and apocrine secretory elements, such as cytokeratins 6/18, 7, and 8/18.17

Pyogenic granulomas (also referred to as lobular capillary hemangiomas) are common and present clinically as rapidly growing, polypoid, red masses surrounded by a thickened epidermis that often are found on the fingers or lips. This entity is benign and often regresses spontaneously. Histologically, pyogenic granulomas are characterized by a lobular pattern of vascular proliferation associated with edema and inflammation resembling granulation tissue, with acanthosis and hyperkeratosis at the edges of the lesion (Figure 3).18

Sebaceous carcinoma is a locally aggressive malignant neoplasm arising from the cells of the sebaceous glands and occurring most commonly in the periorbital area. This neoplasm most often affects older adults, with a mean age at diagnosis of 63 to 77 years. It commonly presents as a solitary nodule with yellowish discoloration and madarosis, which is a key distinguishing feature to differentiate this entity from a chalazion or hordeolum. Histologically, sebaceous carcinoma is a dermal-based infiltrative, nodular tumor with varying degrees of clear cell changes—well-differentiated tumors show more clear cell change as compared to more poorly differentiated variants—along with basaloid or squamous features and abundant mitotic activity (Figure 4), which may be useful in distinguishing it from the other entities in the clear cell neoplasm differential.19-22

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is a common genitourinary system malignancy with incidence peaking between 50 and 70 years of age and a male predominance.1 The clear cell variant is the most common subtype of RCC, accounting for 70% to 75% of all cases. It is known to be a highly aggressive malignancy that frequently metastasizes to the lungs, lymphatics, bones, liver, and brain.2,3 Approximately 20% to 50% of patients with RCC eventually will develop metastasis after nephrectomy.4 Survival with metastatic RCC to any site typically is in the range of 10 to 22 months.5,6 Cutaneous metastases of RCC rarely have been reported in the literature (3%–6% of cases7) and most commonly are found on the scalp, followed by the chest or abdomen. 8 Cutaneous metastases generally are regarded as a late manifestation of the disease with a very poor prognosis. 9 It is unusual to identify cutaneous RCC metastasis without known RCC or other symptoms consistent with advanced RCC, such as hematuria or abdominal/flank pain. Renal cell carcinoma accounts for an estimated 6% to 7% of all cutaneous metastatic lesions.10 Cutaneous metastatic lesions of RCC often are solitary and grow rapidly, with the clinical appearance of an erythematous or violaceous, nodular, highly vascular, and often hemorrhagic growth.9,11,12

Following the histologic diagnosis of metastatic clear cell RCC, our patient was referred to medical oncology for further workup. Magnetic resonance imaging and a positron emission tomography scan demonstrated widespread disease with a 7-cm left renal mass, liver and lung metastases, and bilateral mediastinal lymphadenopathy. The patient was started on combination immunotherapy as a palliative treatment given the widespread disease.

Histologically, clear cell RCC is characterized by lipid and glycogen-rich cells with ample cytoplasm and a well-developed vascular network, which often is thin walled with a chicken wire–like architecture. Metastatic clear cell RCC tumor cells may form glandular, acinar, or papillary structures with variable lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrates and abundant capillary formation. Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells should demonstrate positivity for paired box gene 8, PAX8, and RCC marker antigen.13 Vimentin and carcinoembryonic antigen may be utilized to distinguish from hidradenoma as carcinoembryonic antigen will be positive in hidradenoma and vimentin will be negative.14 Renal cell carcinoma also has a common molecular signature of von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor gene inactivation as well as upregulation of hypoxia inducible factor and vascular endothelial growth factor.15

Balloon cell nevi often clinically present in young patients as bicolored nevi that sometimes are polypoid or verrucous in appearance with central yellow globules surrounded by a peripheral reticular pattern on dermoscopy. Histologically, balloon cell nevi are characterized by large cells with small, round, centrally located basophilic nuclei and clear foamy cytoplasm (Figure 1), which are thought to be formed by progressive vacuolization of melanocytes due to the enlargement and disintegration of melanosomes. This ballooning change reflects an seen in malignant melanoma, in which case nuclear pleomorphism, atypia, and increased mitotic activity also are observed. The prominent vascular network characteristic of RCC typically is not present.16

Clear cell hidradenomas are benign skin appendage tumors that often present as small, firm, solitary dermal nodules that may extend into the subcutaneous fat. They have a predilection for the head, face, and arms and demonstrate 2 predominant cell types, including a polyhedral cell with a rounded nucleus and slightly basophilic cytoplasm as well as a round cell with clear cytoplasm and bland nuclei (Figure 2). The latter cell type is less common, representing the predominant cell type in less than one-third of hidradenomas, and can present a diagnostic quandary based on histologic similarity to other clear cell neoplasms. The clear cells contain glycogen but no lipid. Ductlike structures often are present, and the intervening stroma varies from delicate vascularized cords of fibrous tissue to dense hyalinized collagen. Immunohistochemistry may be required for definitive diagnosis, and clear cell hidradenomas should react with monoclonal antibodies that label both eccrine and apocrine secretory elements, such as cytokeratins 6/18, 7, and 8/18.17

Pyogenic granulomas (also referred to as lobular capillary hemangiomas) are common and present clinically as rapidly growing, polypoid, red masses surrounded by a thickened epidermis that often are found on the fingers or lips. This entity is benign and often regresses spontaneously. Histologically, pyogenic granulomas are characterized by a lobular pattern of vascular proliferation associated with edema and inflammation resembling granulation tissue, with acanthosis and hyperkeratosis at the edges of the lesion (Figure 3).18

Sebaceous carcinoma is a locally aggressive malignant neoplasm arising from the cells of the sebaceous glands and occurring most commonly in the periorbital area. This neoplasm most often affects older adults, with a mean age at diagnosis of 63 to 77 years. It commonly presents as a solitary nodule with yellowish discoloration and madarosis, which is a key distinguishing feature to differentiate this entity from a chalazion or hordeolum. Histologically, sebaceous carcinoma is a dermal-based infiltrative, nodular tumor with varying degrees of clear cell changes—well-differentiated tumors show more clear cell change as compared to more poorly differentiated variants—along with basaloid or squamous features and abundant mitotic activity (Figure 4), which may be useful in distinguishing it from the other entities in the clear cell neoplasm differential.19-22

- Alves de Paula T, Lopes da Silva P, Sueth Berriel LG. Renal cell carcinoma with cutaneous metastasis: case report. J Bras Nefrol. 2010;32:213-215.

- Amaadour L, Atreche L, Azegrar M, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of renal cell carcinoma: a case report. J Cancer Ther. 2017;8:603-607.

- Weiss L, Harlos JP, Torhorst J, et al. Metastatic patterns of renal carcinoma: an analysis of 687 necropsies. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1988;114:605-612.

- Flamigan RC, Campbell SC, Clark JI, et al. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2003;4:385-390.

- Motzer RJ, Bacik J, Schwarz LH, et al. Prognostic factors for survival in previously treated patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:453-463.

- Heng DY, Xie W, Regan MM, et al. Prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with vascular endothelial growth factor–targeted agents: results from a large, multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5694-5799.

- Smyth LG, Rowan GC, David MQ. Renal cell carcinoma presenting as an ominous metachronous scalp metastasis. Can Urol Assoc J. 2010;4:E64-E66.

- Dorairajan LN, Hemal AK, Aron M, et al. Cutaneous metastases in renal cell carcinoma. Urol Int. 1999;63:164-167.

- Koga S, Tsuda S, Nishikido M, et al. Renal cell carcinoma metastatic to the skin. Anticancer Res. 2000;20:1939-1940.

- Krathen RA, Orengo IF, Rosen T. Cutaneous metastasis: a metaanalysis of the data. South Med J. 2003;96:164-167.

- Amano Y, Ohni S, Ishige T, et al. A case of cutaneous metastasis from a clear cell renal cell carcinoma with an eosinophilic cell component to the submandibular region. J Nihon Univ Med Assoc. 2015;74:73-77.

- Arrabal-Polo MA, Arias-Santiago SA, Aneiros-Fernandez J, et al. Cutaneous metastases in renal cell carcinoma: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:7948.

- Sangoi AR, Karamchandani J, Kim J, et al. The use of immunohistochemistry in the diagnosis of metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma: a review of PAX-8, PAX-2, hKIM-1, RCCma, and CD10. Adv Anat Pathol. 2010;17:377-393.

- Velez MJ, Thomas CL, Stratton J, et al. The utility of using immunohistochemistry in the differentiation of metastatic, cutaneous clear cell renal cell carcinoma and clear cell hidradenoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:612-615.

- Nezami BG, MacLennan G. Clear cell. PathologyOutlines website. Published April 20, 2021. Updated March 2, 2022. Accessed April 22, 2022. https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/kidneytumormalignantrccclear.html

- Dhaille F, Courville P, Joly P, et al. Balloon cell nevus: histologic and dermoscopic features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:E55-E56.

- Volmar KE, Cummings TJ, Wang WH, et al. Clear cell hidradenoma: a mimic of metastatic clear cell tumors. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129:E113-E116.

- Hale CS. Capillary/pyogenic granuloma. Pathology Outlines website. Published August 1, 2012. Updated March 10, 2022. Accessed April 20, 2022. https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/skintumornonmelanocyticpyogenicgranuloma.html

- Zada S, Lee BA. Sebaceous carcinoma. Pathology Outlines website. Published August 11, 2021. Accessed April 20, 2022. https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/skintumornonmelanocyticsebaceouscarcinoma.html

- Kahana A, Pribila, JT, Nelson CC, et al. Sebaceous cell carcinoma. In: Levin LA, Albert DM, eds. Ocular Disease: Mechanisms and Management. Elsevier; 2010:396-407.

- Wick MR. Cutaneous tumors and pseudotumors of the head and neck. In: Gnepp DR, ed. Diagnostic Surgical Pathology of the Head and Neck. 2nd ed. Saunders Elsevier; 2009:975-1068.

- Cassarino DS, Dadras SS, Lindberg MR, et al. Sebaceous carcinoma. In: Cassarino DS, Dadras SS, Lindberg MR, et al, eds. Diagnostic Pathology: Neoplastic Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2017:174-179.

- Alves de Paula T, Lopes da Silva P, Sueth Berriel LG. Renal cell carcinoma with cutaneous metastasis: case report. J Bras Nefrol. 2010;32:213-215.

- Amaadour L, Atreche L, Azegrar M, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of renal cell carcinoma: a case report. J Cancer Ther. 2017;8:603-607.

- Weiss L, Harlos JP, Torhorst J, et al. Metastatic patterns of renal carcinoma: an analysis of 687 necropsies. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1988;114:605-612.

- Flamigan RC, Campbell SC, Clark JI, et al. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2003;4:385-390.

- Motzer RJ, Bacik J, Schwarz LH, et al. Prognostic factors for survival in previously treated patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:453-463.

- Heng DY, Xie W, Regan MM, et al. Prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with vascular endothelial growth factor–targeted agents: results from a large, multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5694-5799.

- Smyth LG, Rowan GC, David MQ. Renal cell carcinoma presenting as an ominous metachronous scalp metastasis. Can Urol Assoc J. 2010;4:E64-E66.

- Dorairajan LN, Hemal AK, Aron M, et al. Cutaneous metastases in renal cell carcinoma. Urol Int. 1999;63:164-167.

- Koga S, Tsuda S, Nishikido M, et al. Renal cell carcinoma metastatic to the skin. Anticancer Res. 2000;20:1939-1940.

- Krathen RA, Orengo IF, Rosen T. Cutaneous metastasis: a metaanalysis of the data. South Med J. 2003;96:164-167.

- Amano Y, Ohni S, Ishige T, et al. A case of cutaneous metastasis from a clear cell renal cell carcinoma with an eosinophilic cell component to the submandibular region. J Nihon Univ Med Assoc. 2015;74:73-77.

- Arrabal-Polo MA, Arias-Santiago SA, Aneiros-Fernandez J, et al. Cutaneous metastases in renal cell carcinoma: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:7948.

- Sangoi AR, Karamchandani J, Kim J, et al. The use of immunohistochemistry in the diagnosis of metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma: a review of PAX-8, PAX-2, hKIM-1, RCCma, and CD10. Adv Anat Pathol. 2010;17:377-393.

- Velez MJ, Thomas CL, Stratton J, et al. The utility of using immunohistochemistry in the differentiation of metastatic, cutaneous clear cell renal cell carcinoma and clear cell hidradenoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:612-615.

- Nezami BG, MacLennan G. Clear cell. PathologyOutlines website. Published April 20, 2021. Updated March 2, 2022. Accessed April 22, 2022. https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/kidneytumormalignantrccclear.html

- Dhaille F, Courville P, Joly P, et al. Balloon cell nevus: histologic and dermoscopic features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:E55-E56.

- Volmar KE, Cummings TJ, Wang WH, et al. Clear cell hidradenoma: a mimic of metastatic clear cell tumors. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129:E113-E116.

- Hale CS. Capillary/pyogenic granuloma. Pathology Outlines website. Published August 1, 2012. Updated March 10, 2022. Accessed April 20, 2022. https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/skintumornonmelanocyticpyogenicgranuloma.html

- Zada S, Lee BA. Sebaceous carcinoma. Pathology Outlines website. Published August 11, 2021. Accessed April 20, 2022. https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/skintumornonmelanocyticsebaceouscarcinoma.html

- Kahana A, Pribila, JT, Nelson CC, et al. Sebaceous cell carcinoma. In: Levin LA, Albert DM, eds. Ocular Disease: Mechanisms and Management. Elsevier; 2010:396-407.

- Wick MR. Cutaneous tumors and pseudotumors of the head and neck. In: Gnepp DR, ed. Diagnostic Surgical Pathology of the Head and Neck. 2nd ed. Saunders Elsevier; 2009:975-1068.

- Cassarino DS, Dadras SS, Lindberg MR, et al. Sebaceous carcinoma. In: Cassarino DS, Dadras SS, Lindberg MR, et al, eds. Diagnostic Pathology: Neoplastic Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2017:174-179.

A 71-year-old man with no notable medical history presented with a bleeding nodule on the right lower cutaneous lip of 9 weeks’ duration. The patient denied any systemic symptoms. A shave biopsy was performed.

Ulcerating Nodule on the Foot

The Diagnosis: Perforating Rheumatoid Nodule

Perforating rheumatoid nodule (RN) is a variant of RN that demonstrates necrobiotic material extruding through the epidermis via the process of transepidermal elimination.1 The necrobiotic material contains fibrin and often harbors karyorrhectic debris. The pathogenesis of RN remains unclear; possible mechanisms include a small vessel vasculitis or mechanical trauma inciting a localized aggregation of inflammatory products and rheumatoid factor complexes. This induces macrophage activation, fibrin deposition, and necrosis.2 The majority of patients with RNs have detectable rheumatoid factor and anticyclic citrullinated protein in the blood.3 Rheumatoid nodules are the most common cutaneous manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and will develop in 30% to 40% of RA patients.4,5 They typically are associated with advanced RA but may precede the onset of clinically severe RA in 5% to 10% of patients.5 Rheumatoid nodules generally range in size from 2 mm to 5 cm and are slightly more prevalent in men than in women. They present as firm painless masses typically on the extensor surfaces of the hands and olecranon process but can occur over any tendinous or ligamentlike structure.6,7 Perforating RNs are most common on areas subjected to pressure or repeated trauma, such as the sacrum.

The diagnosis usually is clinical; however, in cases of diagnostic uncertainty, RN can be distinguished by its histologic appearance. Rheumatoid nodules demonstrate granulomatous palisading necrobiosis with a central zone of highly eosinophilic fibrinoid necrobiosis surrounded by palisading mononuclear cells and an outer zone of granulation tissue. There may be a mixed chronic inflammatory infiltrate predominantly composed of lymphocytes and histiocytes in the background.

Rheumatoid nodules typically do not require treatment; however, perforation is known to increase the risk for infection, and surgical excision generally is indicated for prophylaxis against infection, though nodules may recur in the excision area.1,3,8 Alternatively, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and intralesional corticosteroids may effectively reduce the size of RNs. The differential diagnosis for perforating RNs includes epithelioid sarcoma, perforating granuloma annulare, necrobiotic xanthogranuloma, and necrobiosis lipoidica.

Epithelioid sarcoma is a malignant soft tissue tumor typically found on the upper extremities of adolescent or young adult males. They usually present as hard tender nodules that commonly ulcerate. Epithelioid sarcoma makes up less than 1% of soft tissue sarcomas.9 Although rare, they present a diagnostic pitfall, as the histology may mimic an inflammatory palisaded granulomatous dermatitis similar to RN and granuloma annulare, thus a high index of suspicion is required to not overlook this aggressive malignancy. Histology is typified by nodular aggregates of epithelioid cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and often with central zones of necrosis (Figure 1). Epithelioid sarcoma displays immunoreactivity to cytokeratin, CD34, and epithelial membrane antigen, but loss of integrase interactor 1 expression. Cytologic abnormalities such as pleomorphism and hyperchromatism can be helpful in distinguishing between epithelioid sarcoma and RN.

Perforating granuloma annulare is a rare subtype of granuloma annulare that presents with flesh- to red-colored papules that develop central crust or scale. Perforating granuloma annulare composes approximately 5% of granuloma annulare cases. Perforating granuloma annulare can develop on any region of the body but has an affinity for the extensor surfaces of the extremities. It most frequently occurs in young women and rarely presents as a single lesion.10 Granuloma annulare typically is not associated with joint pain, and thus it differs from most cases of RNs. Histologically, it presents with an inflammatory palisading granuloma. There may be overlying epidermal thinning or parakeratosis, which can progress to perforation and extrusion of necrobiotic material. In comparison with RN, perforating granuloma annulare displays mucin deposition in the necrobiotic zones in lieu of fibrin (Figure 2).10,11

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is a rare chronic form of non-Langerhans histiocytosis that characteristically presents with yellow or violaceous indurated plaques and nodules in a periorbital distribution. It often is associated with monoclonal gammopathy of IgG-κ. Lesions will ulcerate in 40% to 50% of patients.12 The mean age at presentation is in the sixth decade of life, and it is moderately predominant in females.13 Histopathology demonstrates palisading granulomatous formations with a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate and zones of necrobiosis in the mid dermis extending into the panniculus. Characteristic histologic features that are variably present in necrobiotic xanthogranuloma but typically absent in RN include neutrophilic debris, cholesterol clefts, and Touton or foreign body giant cells (Figure 3).13

Necrobiosis lipoidica is a rare chronic granulomatous disease characterized by well-demarcated, atrophic, yellow-brown plaques on the pretibial surfaces. It typically presents in the third decade of life in women, and most cases are associated with diabetes mellitus types 1 or 2 or autoimmune conditions.14 Necrobiosis lipoidica begins as asymptomatic papules that enlarge progressively over months to years. They can become pruritic or painful and often develop ulceration. Histopathology shows horizontal zones of palisading histiocytes with intervening necrobiosis. An inflammatory infiltrate containing plasma cells also may be present (Figure 4).

- Horn RT Jr, Goette DK. Perforating rheumatoid nodule. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:696-697.

- Tilstra JS, Lienesch DW. Rheumatoid nodules. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:361-371. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.004

- Kaye BR, Kaye RL, Bobrove A. Rheumatoid nodules. review of the spectrum of associated conditions and proposal of a new classification, with a report of four seronegative cases. Am J Med. 1984;76:279-292. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(84)90787-3

- Nyhäll-Wåhlin BM, Jacobsson LT, Petersson IF, et al; BARFOT study group. Smoking is a strong risk factor for rheumatoid nodules in early rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:601-606. doi:10.1136/ard.2005.039172

- Turesson C, O’Fallon WM, Crowson CS, et al. Occurrence of extraarticular disease manifestations is associated with excess mortality in a community-based cohort of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:62-67.

- Bang S, Kim Y, Jang K, et al. Clinicopathologic features of rheumatoid nodules: a retrospective analysis. Clin Rheumatol. 2019;38:3041-3048. doi:10.1007/s10067-019-04668-1

- Chaganti S, Joshy S, Hariharan K, et al. Rheumatoid nodule presenting as Morton’s neuroma. J Orthop Traumatol. 2013;14:219-222. doi:10.1007/s10195-012-0215-x

- Sayah A, English JC 3rd. Rheumatoid arthritis: a review of the cutaneous manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:191-209; quiz 210-212. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.07.023

- de Visscher SA, van Ginkel RJ, Wobbes T, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma: still an only surgically curable disease. Cancer. 2006;107:606-612. doi:10.1002/cncr.22037

- Penas PF, Jones-Caballero M, Fraga J, et al. Perforating granuloma annulare. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:340-348. doi:10.1046 /j.1365-4362.1997.00047.x

- Gale M, Gilbert E, Blumenthal D. Isolated rheumatoid nodules: a diagnostic dilemma. Case Rep Med. 2015;2015:352352. doi:10.1155/2015/352352

- Wood AJ, Wagner MV, Abbott JJ, et al. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma: a review of 17 cases with emphasis on clinical and pathologic correlation. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:279-284. doi:10.1001 /archdermatol.2008.583

- Nelson CA, Zhong CS, Hashemi DA, et al. A multicenter crosssectional study and systematic review of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma with proposed diagnostic criteria. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:270-279. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.4221

- Sibbald C, Reid S, Alavi A. Necrobiosis lipoidica. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:343-360. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.003

The Diagnosis: Perforating Rheumatoid Nodule

Perforating rheumatoid nodule (RN) is a variant of RN that demonstrates necrobiotic material extruding through the epidermis via the process of transepidermal elimination.1 The necrobiotic material contains fibrin and often harbors karyorrhectic debris. The pathogenesis of RN remains unclear; possible mechanisms include a small vessel vasculitis or mechanical trauma inciting a localized aggregation of inflammatory products and rheumatoid factor complexes. This induces macrophage activation, fibrin deposition, and necrosis.2 The majority of patients with RNs have detectable rheumatoid factor and anticyclic citrullinated protein in the blood.3 Rheumatoid nodules are the most common cutaneous manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and will develop in 30% to 40% of RA patients.4,5 They typically are associated with advanced RA but may precede the onset of clinically severe RA in 5% to 10% of patients.5 Rheumatoid nodules generally range in size from 2 mm to 5 cm and are slightly more prevalent in men than in women. They present as firm painless masses typically on the extensor surfaces of the hands and olecranon process but can occur over any tendinous or ligamentlike structure.6,7 Perforating RNs are most common on areas subjected to pressure or repeated trauma, such as the sacrum.

The diagnosis usually is clinical; however, in cases of diagnostic uncertainty, RN can be distinguished by its histologic appearance. Rheumatoid nodules demonstrate granulomatous palisading necrobiosis with a central zone of highly eosinophilic fibrinoid necrobiosis surrounded by palisading mononuclear cells and an outer zone of granulation tissue. There may be a mixed chronic inflammatory infiltrate predominantly composed of lymphocytes and histiocytes in the background.

Rheumatoid nodules typically do not require treatment; however, perforation is known to increase the risk for infection, and surgical excision generally is indicated for prophylaxis against infection, though nodules may recur in the excision area.1,3,8 Alternatively, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and intralesional corticosteroids may effectively reduce the size of RNs. The differential diagnosis for perforating RNs includes epithelioid sarcoma, perforating granuloma annulare, necrobiotic xanthogranuloma, and necrobiosis lipoidica.

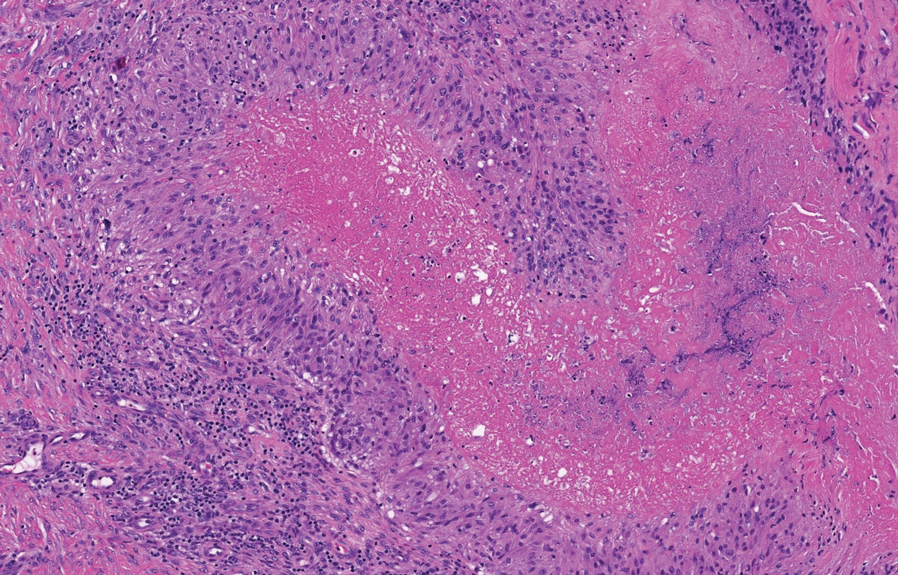

Epithelioid sarcoma is a malignant soft tissue tumor typically found on the upper extremities of adolescent or young adult males. They usually present as hard tender nodules that commonly ulcerate. Epithelioid sarcoma makes up less than 1% of soft tissue sarcomas.9 Although rare, they present a diagnostic pitfall, as the histology may mimic an inflammatory palisaded granulomatous dermatitis similar to RN and granuloma annulare, thus a high index of suspicion is required to not overlook this aggressive malignancy. Histology is typified by nodular aggregates of epithelioid cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and often with central zones of necrosis (Figure 1). Epithelioid sarcoma displays immunoreactivity to cytokeratin, CD34, and epithelial membrane antigen, but loss of integrase interactor 1 expression. Cytologic abnormalities such as pleomorphism and hyperchromatism can be helpful in distinguishing between epithelioid sarcoma and RN.

Perforating granuloma annulare is a rare subtype of granuloma annulare that presents with flesh- to red-colored papules that develop central crust or scale. Perforating granuloma annulare composes approximately 5% of granuloma annulare cases. Perforating granuloma annulare can develop on any region of the body but has an affinity for the extensor surfaces of the extremities. It most frequently occurs in young women and rarely presents as a single lesion.10 Granuloma annulare typically is not associated with joint pain, and thus it differs from most cases of RNs. Histologically, it presents with an inflammatory palisading granuloma. There may be overlying epidermal thinning or parakeratosis, which can progress to perforation and extrusion of necrobiotic material. In comparison with RN, perforating granuloma annulare displays mucin deposition in the necrobiotic zones in lieu of fibrin (Figure 2).10,11

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is a rare chronic form of non-Langerhans histiocytosis that characteristically presents with yellow or violaceous indurated plaques and nodules in a periorbital distribution. It often is associated with monoclonal gammopathy of IgG-κ. Lesions will ulcerate in 40% to 50% of patients.12 The mean age at presentation is in the sixth decade of life, and it is moderately predominant in females.13 Histopathology demonstrates palisading granulomatous formations with a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate and zones of necrobiosis in the mid dermis extending into the panniculus. Characteristic histologic features that are variably present in necrobiotic xanthogranuloma but typically absent in RN include neutrophilic debris, cholesterol clefts, and Touton or foreign body giant cells (Figure 3).13

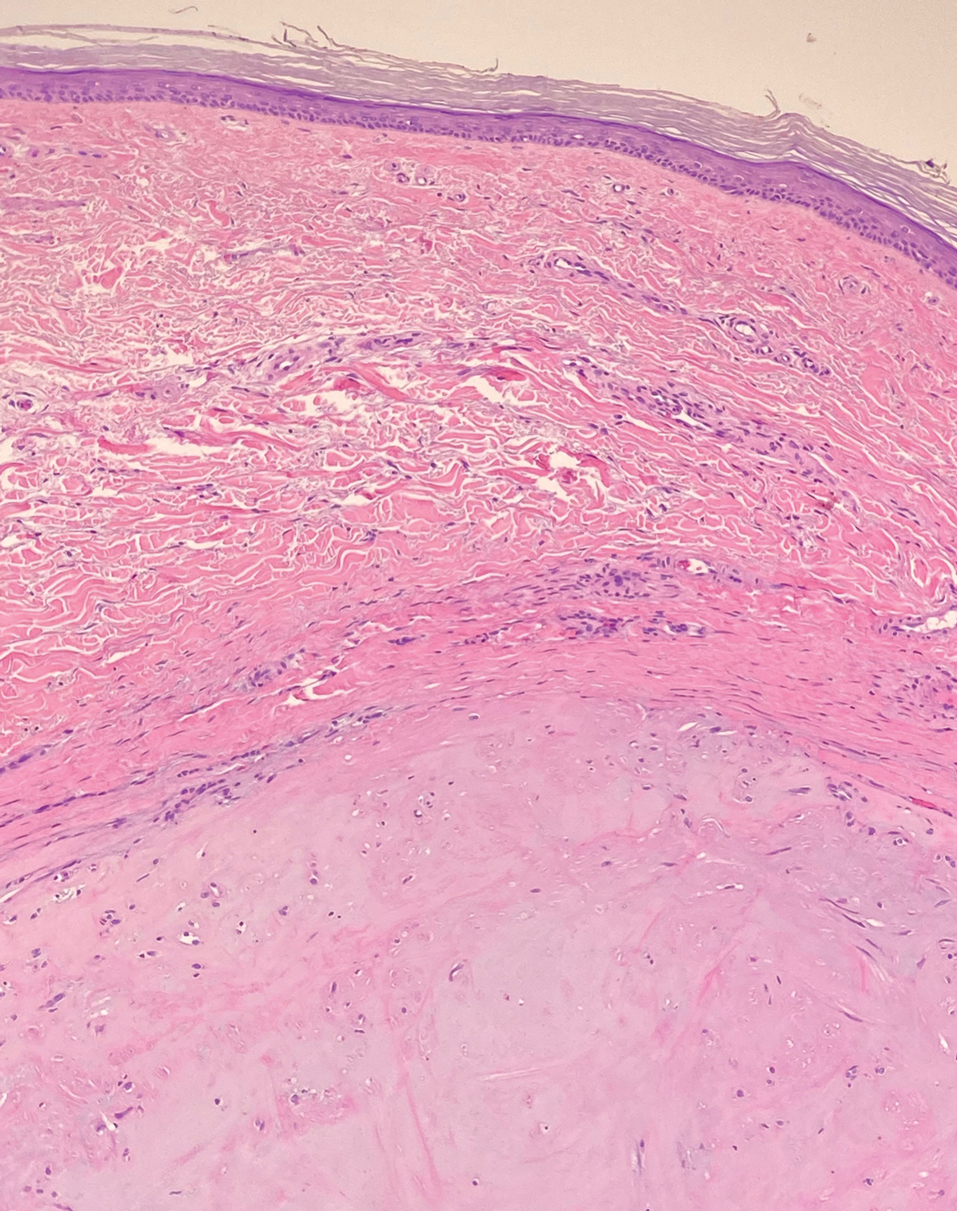

Necrobiosis lipoidica is a rare chronic granulomatous disease characterized by well-demarcated, atrophic, yellow-brown plaques on the pretibial surfaces. It typically presents in the third decade of life in women, and most cases are associated with diabetes mellitus types 1 or 2 or autoimmune conditions.14 Necrobiosis lipoidica begins as asymptomatic papules that enlarge progressively over months to years. They can become pruritic or painful and often develop ulceration. Histopathology shows horizontal zones of palisading histiocytes with intervening necrobiosis. An inflammatory infiltrate containing plasma cells also may be present (Figure 4).

The Diagnosis: Perforating Rheumatoid Nodule

Perforating rheumatoid nodule (RN) is a variant of RN that demonstrates necrobiotic material extruding through the epidermis via the process of transepidermal elimination.1 The necrobiotic material contains fibrin and often harbors karyorrhectic debris. The pathogenesis of RN remains unclear; possible mechanisms include a small vessel vasculitis or mechanical trauma inciting a localized aggregation of inflammatory products and rheumatoid factor complexes. This induces macrophage activation, fibrin deposition, and necrosis.2 The majority of patients with RNs have detectable rheumatoid factor and anticyclic citrullinated protein in the blood.3 Rheumatoid nodules are the most common cutaneous manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and will develop in 30% to 40% of RA patients.4,5 They typically are associated with advanced RA but may precede the onset of clinically severe RA in 5% to 10% of patients.5 Rheumatoid nodules generally range in size from 2 mm to 5 cm and are slightly more prevalent in men than in women. They present as firm painless masses typically on the extensor surfaces of the hands and olecranon process but can occur over any tendinous or ligamentlike structure.6,7 Perforating RNs are most common on areas subjected to pressure or repeated trauma, such as the sacrum.

The diagnosis usually is clinical; however, in cases of diagnostic uncertainty, RN can be distinguished by its histologic appearance. Rheumatoid nodules demonstrate granulomatous palisading necrobiosis with a central zone of highly eosinophilic fibrinoid necrobiosis surrounded by palisading mononuclear cells and an outer zone of granulation tissue. There may be a mixed chronic inflammatory infiltrate predominantly composed of lymphocytes and histiocytes in the background.

Rheumatoid nodules typically do not require treatment; however, perforation is known to increase the risk for infection, and surgical excision generally is indicated for prophylaxis against infection, though nodules may recur in the excision area.1,3,8 Alternatively, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and intralesional corticosteroids may effectively reduce the size of RNs. The differential diagnosis for perforating RNs includes epithelioid sarcoma, perforating granuloma annulare, necrobiotic xanthogranuloma, and necrobiosis lipoidica.

Epithelioid sarcoma is a malignant soft tissue tumor typically found on the upper extremities of adolescent or young adult males. They usually present as hard tender nodules that commonly ulcerate. Epithelioid sarcoma makes up less than 1% of soft tissue sarcomas.9 Although rare, they present a diagnostic pitfall, as the histology may mimic an inflammatory palisaded granulomatous dermatitis similar to RN and granuloma annulare, thus a high index of suspicion is required to not overlook this aggressive malignancy. Histology is typified by nodular aggregates of epithelioid cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and often with central zones of necrosis (Figure 1). Epithelioid sarcoma displays immunoreactivity to cytokeratin, CD34, and epithelial membrane antigen, but loss of integrase interactor 1 expression. Cytologic abnormalities such as pleomorphism and hyperchromatism can be helpful in distinguishing between epithelioid sarcoma and RN.

Perforating granuloma annulare is a rare subtype of granuloma annulare that presents with flesh- to red-colored papules that develop central crust or scale. Perforating granuloma annulare composes approximately 5% of granuloma annulare cases. Perforating granuloma annulare can develop on any region of the body but has an affinity for the extensor surfaces of the extremities. It most frequently occurs in young women and rarely presents as a single lesion.10 Granuloma annulare typically is not associated with joint pain, and thus it differs from most cases of RNs. Histologically, it presents with an inflammatory palisading granuloma. There may be overlying epidermal thinning or parakeratosis, which can progress to perforation and extrusion of necrobiotic material. In comparison with RN, perforating granuloma annulare displays mucin deposition in the necrobiotic zones in lieu of fibrin (Figure 2).10,11

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is a rare chronic form of non-Langerhans histiocytosis that characteristically presents with yellow or violaceous indurated plaques and nodules in a periorbital distribution. It often is associated with monoclonal gammopathy of IgG-κ. Lesions will ulcerate in 40% to 50% of patients.12 The mean age at presentation is in the sixth decade of life, and it is moderately predominant in females.13 Histopathology demonstrates palisading granulomatous formations with a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate and zones of necrobiosis in the mid dermis extending into the panniculus. Characteristic histologic features that are variably present in necrobiotic xanthogranuloma but typically absent in RN include neutrophilic debris, cholesterol clefts, and Touton or foreign body giant cells (Figure 3).13

Necrobiosis lipoidica is a rare chronic granulomatous disease characterized by well-demarcated, atrophic, yellow-brown plaques on the pretibial surfaces. It typically presents in the third decade of life in women, and most cases are associated with diabetes mellitus types 1 or 2 or autoimmune conditions.14 Necrobiosis lipoidica begins as asymptomatic papules that enlarge progressively over months to years. They can become pruritic or painful and often develop ulceration. Histopathology shows horizontal zones of palisading histiocytes with intervening necrobiosis. An inflammatory infiltrate containing plasma cells also may be present (Figure 4).

- Horn RT Jr, Goette DK. Perforating rheumatoid nodule. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:696-697.

- Tilstra JS, Lienesch DW. Rheumatoid nodules. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:361-371. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.004

- Kaye BR, Kaye RL, Bobrove A. Rheumatoid nodules. review of the spectrum of associated conditions and proposal of a new classification, with a report of four seronegative cases. Am J Med. 1984;76:279-292. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(84)90787-3

- Nyhäll-Wåhlin BM, Jacobsson LT, Petersson IF, et al; BARFOT study group. Smoking is a strong risk factor for rheumatoid nodules in early rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:601-606. doi:10.1136/ard.2005.039172

- Turesson C, O’Fallon WM, Crowson CS, et al. Occurrence of extraarticular disease manifestations is associated with excess mortality in a community-based cohort of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:62-67.

- Bang S, Kim Y, Jang K, et al. Clinicopathologic features of rheumatoid nodules: a retrospective analysis. Clin Rheumatol. 2019;38:3041-3048. doi:10.1007/s10067-019-04668-1

- Chaganti S, Joshy S, Hariharan K, et al. Rheumatoid nodule presenting as Morton’s neuroma. J Orthop Traumatol. 2013;14:219-222. doi:10.1007/s10195-012-0215-x

- Sayah A, English JC 3rd. Rheumatoid arthritis: a review of the cutaneous manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:191-209; quiz 210-212. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.07.023

- de Visscher SA, van Ginkel RJ, Wobbes T, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma: still an only surgically curable disease. Cancer. 2006;107:606-612. doi:10.1002/cncr.22037

- Penas PF, Jones-Caballero M, Fraga J, et al. Perforating granuloma annulare. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:340-348. doi:10.1046 /j.1365-4362.1997.00047.x

- Gale M, Gilbert E, Blumenthal D. Isolated rheumatoid nodules: a diagnostic dilemma. Case Rep Med. 2015;2015:352352. doi:10.1155/2015/352352

- Wood AJ, Wagner MV, Abbott JJ, et al. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma: a review of 17 cases with emphasis on clinical and pathologic correlation. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:279-284. doi:10.1001 /archdermatol.2008.583

- Nelson CA, Zhong CS, Hashemi DA, et al. A multicenter crosssectional study and systematic review of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma with proposed diagnostic criteria. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:270-279. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.4221

- Sibbald C, Reid S, Alavi A. Necrobiosis lipoidica. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:343-360. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.003

- Horn RT Jr, Goette DK. Perforating rheumatoid nodule. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:696-697.

- Tilstra JS, Lienesch DW. Rheumatoid nodules. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:361-371. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.004

- Kaye BR, Kaye RL, Bobrove A. Rheumatoid nodules. review of the spectrum of associated conditions and proposal of a new classification, with a report of four seronegative cases. Am J Med. 1984;76:279-292. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(84)90787-3

- Nyhäll-Wåhlin BM, Jacobsson LT, Petersson IF, et al; BARFOT study group. Smoking is a strong risk factor for rheumatoid nodules in early rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:601-606. doi:10.1136/ard.2005.039172

- Turesson C, O’Fallon WM, Crowson CS, et al. Occurrence of extraarticular disease manifestations is associated with excess mortality in a community-based cohort of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:62-67.

- Bang S, Kim Y, Jang K, et al. Clinicopathologic features of rheumatoid nodules: a retrospective analysis. Clin Rheumatol. 2019;38:3041-3048. doi:10.1007/s10067-019-04668-1

- Chaganti S, Joshy S, Hariharan K, et al. Rheumatoid nodule presenting as Morton’s neuroma. J Orthop Traumatol. 2013;14:219-222. doi:10.1007/s10195-012-0215-x

- Sayah A, English JC 3rd. Rheumatoid arthritis: a review of the cutaneous manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:191-209; quiz 210-212. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.07.023

- de Visscher SA, van Ginkel RJ, Wobbes T, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma: still an only surgically curable disease. Cancer. 2006;107:606-612. doi:10.1002/cncr.22037

- Penas PF, Jones-Caballero M, Fraga J, et al. Perforating granuloma annulare. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:340-348. doi:10.1046 /j.1365-4362.1997.00047.x

- Gale M, Gilbert E, Blumenthal D. Isolated rheumatoid nodules: a diagnostic dilemma. Case Rep Med. 2015;2015:352352. doi:10.1155/2015/352352

- Wood AJ, Wagner MV, Abbott JJ, et al. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma: a review of 17 cases with emphasis on clinical and pathologic correlation. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:279-284. doi:10.1001 /archdermatol.2008.583