User login

What is your diagnosis? - February 2019

Retrograde colocolic intussusception induced by colonic adenocarcinoma

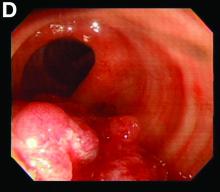

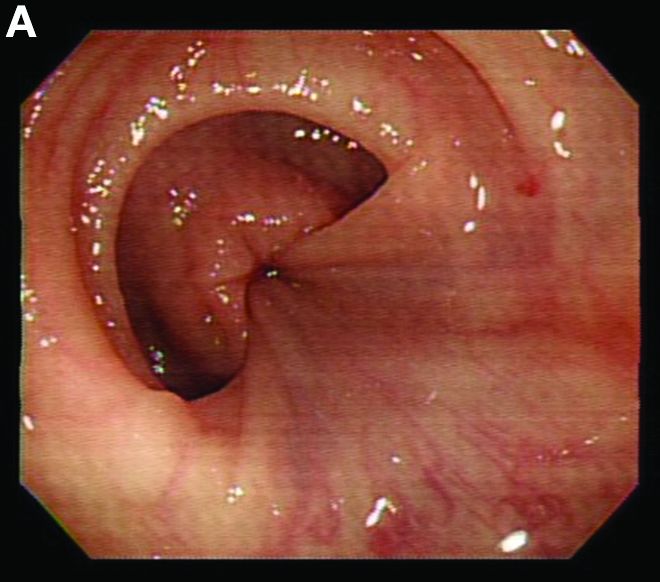

We used biopsy forceps for slow retraction (Figure B) and complete reduction (Figure C). The colonoscope was further inserted up to the cecum and no other lesions were found. A very large polyp was excised partially using a snare for the prevention of repeated intussusception and for histologic examination (Figure D). The pathology revealed adenocarcinoma and the patient underwent surgery. Recovery was uneventful and the patient was discharged 1 week later.

Intussusception is defined as the invagination of a segment of the bowel and its mesentery into the adjacent bowel lumen. It is a common cause of intestinal obstruction in children, but rare in adults. Adult intussusception accounts for 5% of all causes of bowel obstruction and 5%-10% of all intussusception, and usually has a lead point.1 Retrograde colocolic intussusception is especially rare, with only 26 cases reported up to 2014.2 Altered peristalsis in focal areas of the bowel wall can lead to dysrhythmic contractions and cause retrograde intussusception.

Adult colonic intussusception has atypical, nonspecific, intermittent, and vague symptoms and signs, resulting in a diagnostic challenge. Approximately one-half of patients present with symptoms of colonic obstruction with a duration of more than 1 month, as in our case. Many cases involve acute intestinal obstruction and are managed through emergency operation. Ultrasound imaging and computed tomography scans are the most sensitive and most commonly used preoperative diagnostic modalities. Colonoscopy is a useful tool for evaluating intussusception in colocolic intussusception,3 but there is no reported diagnosis of retrograde colocolic intussusception and reduction, as in this case.

Treatment of adult intussusception is more frequently surgical compared with that in children, and leads to resection of the involved bowel segment without reduction before resection.3 In our case, intussusception was reduced easily with biopsy forceps under a direct colonoscopic view and was cured through elective laparoscopic left hemicolectomy after histologic proof was obtained.

References

1. Joseph T, Desai AL. Retrograde intussusception of sigmoid colon. J R Soc Med. 2004;7:127-8.

2.Baba M, Higaki N, Ishida M, et al. A case of retrograde intussusception due to semipedunculated polypiform adenocarcinoma in tubular adenoma of the sigmoid colon in an adult. Jpn J Gastroenterol Surg. 2001;34:282-6.

3. Kamble MA, Thawait AP, Kamble AT. Left side reverse colocolic intussusception secondary to malignant polypoidal growth: a rare clinical entity. Int Surg J. 2014;1:39-42.

Retrograde colocolic intussusception induced by colonic adenocarcinoma

We used biopsy forceps for slow retraction (Figure B) and complete reduction (Figure C). The colonoscope was further inserted up to the cecum and no other lesions were found. A very large polyp was excised partially using a snare for the prevention of repeated intussusception and for histologic examination (Figure D). The pathology revealed adenocarcinoma and the patient underwent surgery. Recovery was uneventful and the patient was discharged 1 week later.

Intussusception is defined as the invagination of a segment of the bowel and its mesentery into the adjacent bowel lumen. It is a common cause of intestinal obstruction in children, but rare in adults. Adult intussusception accounts for 5% of all causes of bowel obstruction and 5%-10% of all intussusception, and usually has a lead point.1 Retrograde colocolic intussusception is especially rare, with only 26 cases reported up to 2014.2 Altered peristalsis in focal areas of the bowel wall can lead to dysrhythmic contractions and cause retrograde intussusception.

Adult colonic intussusception has atypical, nonspecific, intermittent, and vague symptoms and signs, resulting in a diagnostic challenge. Approximately one-half of patients present with symptoms of colonic obstruction with a duration of more than 1 month, as in our case. Many cases involve acute intestinal obstruction and are managed through emergency operation. Ultrasound imaging and computed tomography scans are the most sensitive and most commonly used preoperative diagnostic modalities. Colonoscopy is a useful tool for evaluating intussusception in colocolic intussusception,3 but there is no reported diagnosis of retrograde colocolic intussusception and reduction, as in this case.

Treatment of adult intussusception is more frequently surgical compared with that in children, and leads to resection of the involved bowel segment without reduction before resection.3 In our case, intussusception was reduced easily with biopsy forceps under a direct colonoscopic view and was cured through elective laparoscopic left hemicolectomy after histologic proof was obtained.

References

1. Joseph T, Desai AL. Retrograde intussusception of sigmoid colon. J R Soc Med. 2004;7:127-8.

2.Baba M, Higaki N, Ishida M, et al. A case of retrograde intussusception due to semipedunculated polypiform adenocarcinoma in tubular adenoma of the sigmoid colon in an adult. Jpn J Gastroenterol Surg. 2001;34:282-6.

3. Kamble MA, Thawait AP, Kamble AT. Left side reverse colocolic intussusception secondary to malignant polypoidal growth: a rare clinical entity. Int Surg J. 2014;1:39-42.

Retrograde colocolic intussusception induced by colonic adenocarcinoma

We used biopsy forceps for slow retraction (Figure B) and complete reduction (Figure C). The colonoscope was further inserted up to the cecum and no other lesions were found. A very large polyp was excised partially using a snare for the prevention of repeated intussusception and for histologic examination (Figure D). The pathology revealed adenocarcinoma and the patient underwent surgery. Recovery was uneventful and the patient was discharged 1 week later.

Intussusception is defined as the invagination of a segment of the bowel and its mesentery into the adjacent bowel lumen. It is a common cause of intestinal obstruction in children, but rare in adults. Adult intussusception accounts for 5% of all causes of bowel obstruction and 5%-10% of all intussusception, and usually has a lead point.1 Retrograde colocolic intussusception is especially rare, with only 26 cases reported up to 2014.2 Altered peristalsis in focal areas of the bowel wall can lead to dysrhythmic contractions and cause retrograde intussusception.

Adult colonic intussusception has atypical, nonspecific, intermittent, and vague symptoms and signs, resulting in a diagnostic challenge. Approximately one-half of patients present with symptoms of colonic obstruction with a duration of more than 1 month, as in our case. Many cases involve acute intestinal obstruction and are managed through emergency operation. Ultrasound imaging and computed tomography scans are the most sensitive and most commonly used preoperative diagnostic modalities. Colonoscopy is a useful tool for evaluating intussusception in colocolic intussusception,3 but there is no reported diagnosis of retrograde colocolic intussusception and reduction, as in this case.

Treatment of adult intussusception is more frequently surgical compared with that in children, and leads to resection of the involved bowel segment without reduction before resection.3 In our case, intussusception was reduced easily with biopsy forceps under a direct colonoscopic view and was cured through elective laparoscopic left hemicolectomy after histologic proof was obtained.

References

1. Joseph T, Desai AL. Retrograde intussusception of sigmoid colon. J R Soc Med. 2004;7:127-8.

2.Baba M, Higaki N, Ishida M, et al. A case of retrograde intussusception due to semipedunculated polypiform adenocarcinoma in tubular adenoma of the sigmoid colon in an adult. Jpn J Gastroenterol Surg. 2001;34:282-6.

3. Kamble MA, Thawait AP, Kamble AT. Left side reverse colocolic intussusception secondary to malignant polypoidal growth: a rare clinical entity. Int Surg J. 2014;1:39-42.

What is your diagnosis? - January 2019

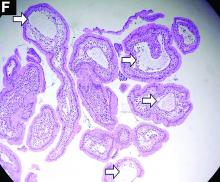

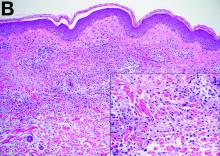

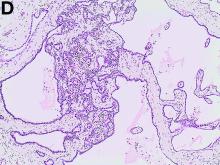

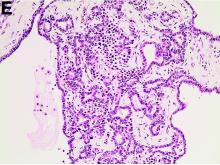

Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia

Histologic examination shows chronic inflammation of the ileum characterized by increased lymphoplasma cell infiltration of lamina propria without malignancy. Moreover, marked dilatation of lymphatic ducts that involved the mucosa was identified (Figure F, arrows; stain: hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification, ×100). On the basis of pathologic examinations, a diagnosis of primary intestinal lymphangiectasia (PIL) was made.

PIL is an extremely rare cause of protein-losing enteropathy characterized by the presence of dilated lymphatic channels in the mucosa, submucosa, or subserosa leading to protein-losing enteropathy.1 The true incidence and prevalence of this disease remains unclear. The disease affects males and females equally, and usually occurs in children and young adults. To date, less than 200 cases of PIL have been reported in the literature. The clinical manifestations of PIL may be asymptomatic or symptomatic such as abdominal pain, edema, diarrhea, and dyspnea. The diagnosis is based on the typical endoscopic findings of diffuse scattered mucosal white blebs with characteristic histologic findings of abnormal lymphatic dilatation. Double-balloon enteroscopy and capsule endoscopy are powerful modalities to evaluate the entire affected area of PIL.2 Although diet modification is a major treatment of PIL, several medicines have been reported to be useful such as corticosteroids, octreotide, and antiplasmin.3 Moreover, in patients with segmental lesions, surgery with local bowel resection is a useful treatment.3 In addition, PIL had a 5% risk of malignant transformation into lymphoma.3

References

1. Waldmann TA, Steinfeld JL, Dutcher TF, et al. The role of the gastrointestinal system in “idiopathic hypoproteinemia.” Gastroenterology. 1961;41:197-207.

2. Oh TG, Chung JW, Kim HM, et al. Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia diagnosed by capsule endoscopy and double balloon enteroscopy. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;3:235-40.

3. Wen J, Tang Q, Wu, J. Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia: four case reports and a review of the literature. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:3466-72.

Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia

Histologic examination shows chronic inflammation of the ileum characterized by increased lymphoplasma cell infiltration of lamina propria without malignancy. Moreover, marked dilatation of lymphatic ducts that involved the mucosa was identified (Figure F, arrows; stain: hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification, ×100). On the basis of pathologic examinations, a diagnosis of primary intestinal lymphangiectasia (PIL) was made.

PIL is an extremely rare cause of protein-losing enteropathy characterized by the presence of dilated lymphatic channels in the mucosa, submucosa, or subserosa leading to protein-losing enteropathy.1 The true incidence and prevalence of this disease remains unclear. The disease affects males and females equally, and usually occurs in children and young adults. To date, less than 200 cases of PIL have been reported in the literature. The clinical manifestations of PIL may be asymptomatic or symptomatic such as abdominal pain, edema, diarrhea, and dyspnea. The diagnosis is based on the typical endoscopic findings of diffuse scattered mucosal white blebs with characteristic histologic findings of abnormal lymphatic dilatation. Double-balloon enteroscopy and capsule endoscopy are powerful modalities to evaluate the entire affected area of PIL.2 Although diet modification is a major treatment of PIL, several medicines have been reported to be useful such as corticosteroids, octreotide, and antiplasmin.3 Moreover, in patients with segmental lesions, surgery with local bowel resection is a useful treatment.3 In addition, PIL had a 5% risk of malignant transformation into lymphoma.3

References

1. Waldmann TA, Steinfeld JL, Dutcher TF, et al. The role of the gastrointestinal system in “idiopathic hypoproteinemia.” Gastroenterology. 1961;41:197-207.

2. Oh TG, Chung JW, Kim HM, et al. Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia diagnosed by capsule endoscopy and double balloon enteroscopy. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;3:235-40.

3. Wen J, Tang Q, Wu, J. Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia: four case reports and a review of the literature. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:3466-72.

Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia

Histologic examination shows chronic inflammation of the ileum characterized by increased lymphoplasma cell infiltration of lamina propria without malignancy. Moreover, marked dilatation of lymphatic ducts that involved the mucosa was identified (Figure F, arrows; stain: hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification, ×100). On the basis of pathologic examinations, a diagnosis of primary intestinal lymphangiectasia (PIL) was made.

PIL is an extremely rare cause of protein-losing enteropathy characterized by the presence of dilated lymphatic channels in the mucosa, submucosa, or subserosa leading to protein-losing enteropathy.1 The true incidence and prevalence of this disease remains unclear. The disease affects males and females equally, and usually occurs in children and young adults. To date, less than 200 cases of PIL have been reported in the literature. The clinical manifestations of PIL may be asymptomatic or symptomatic such as abdominal pain, edema, diarrhea, and dyspnea. The diagnosis is based on the typical endoscopic findings of diffuse scattered mucosal white blebs with characteristic histologic findings of abnormal lymphatic dilatation. Double-balloon enteroscopy and capsule endoscopy are powerful modalities to evaluate the entire affected area of PIL.2 Although diet modification is a major treatment of PIL, several medicines have been reported to be useful such as corticosteroids, octreotide, and antiplasmin.3 Moreover, in patients with segmental lesions, surgery with local bowel resection is a useful treatment.3 In addition, PIL had a 5% risk of malignant transformation into lymphoma.3

References

1. Waldmann TA, Steinfeld JL, Dutcher TF, et al. The role of the gastrointestinal system in “idiopathic hypoproteinemia.” Gastroenterology. 1961;41:197-207.

2. Oh TG, Chung JW, Kim HM, et al. Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia diagnosed by capsule endoscopy and double balloon enteroscopy. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;3:235-40.

3. Wen J, Tang Q, Wu, J. Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia: four case reports and a review of the literature. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:3466-72.

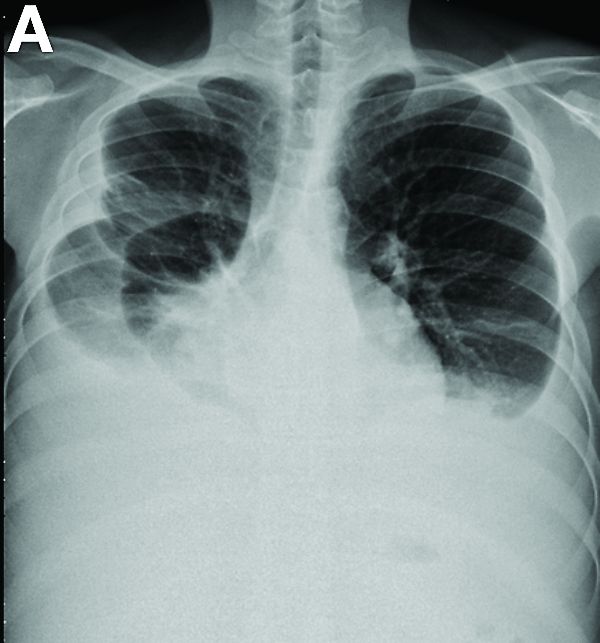

A 19-year-old boy presented to our hospital because of a 6-month history of progressive dyspnea and generalized edema. He developed cough, abdominal fullness, diarrhea, and leg edema 5 years ago.

Liver cirrhosis was suspected at that time. However, he seemed to have a poor response to medical treatment. Physical examination showed decreased breathing sounds and rales of the bilateral lower chest area, a distended abdomen with multiple purple striae, and edema of bilateral lower legs.

Laboratory tests showed a low serum total protein of 3.8 g/dL (normal range, 5.5–8), albumin of 2.0 g/dL (normal range, 3.8–5.4), total calcium of 7 mg/dL (normal range, 8.4–10.8), C-reactive protein of 11.02 mg/dL (normal, below 0.8). His hemogram showed a white blood cell count of 13,310 × 109/L (normal range, 3.5–11 × 109/L) with lymphocytopenia (9.8%).

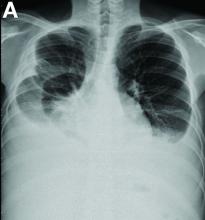

Other blood tests were within normal limits. The urinalysis and stool analysis were normal. Chest radiography showed bilateral pleural effusions (Figure A). Abdominal computed tomography demonstrated large ascites (Figure B). Paracentesis showed his serum ascites albumin gradient was 1.9 g/dL.

Subsequently, antegrade double-balloon enteroscopy (Fujinon EN-450T5; Fujinon, Saitama, Japan) demonstrated nodular mucosal lesions with a milk-like surface in the duodenum (Figure C).

Moreover, a snowflake appearance of mucosa was found in the jejunum and proximal ileum (Figure D). However, normal appearance of mucosa was identified in the middle ileum (Figure E). Biopsy specimens from these abnormal mucosal lesions were taken for pathology.

What is the diagnosis?

What is your diagnosis? - December 2018

Cecal carcinoma–associated paraneoplastic Sweet’s syndrome

Based on the tomographic appearance of an “apple core”–like lesion in the right lower quadrant, the patient was referred for colonoscopy, which revealed a malignant-appearing cecal mass (Figure D), with biopsies confirming adenocarcinoma; despite these findings, no bowel-related symptoms were reported. The patient underwent laparoscopic right hemicolectomy, after which the skin lesions began to resolve, and corticosteroids were successfully tapered. The overall presentation was consistent with Sweet’s syndrome, with a paraneoplastic etiology being favored given the clinical scenario, including absence of alternative etiologies and dependence on corticosteroids for control of skin disease until resection of the underlying malignancy was performed.

Sweet’s syndrome was first described in a case series of eight patients published in 1964 by the English dermatologist Dr. Robert Douglas Sweet.1,2 Sweet’s syndrome is characterized by fever, neutrophilia, and sterile erythematous plaques or nodules, which most commonly involve the upper extremities and face and respond to corticosteroid therapy. It may be malignancy associated, drug induced, autoimmune disease related, or idiopathic.2,3 The pathogenesis of Sweet’s syndrome is unclear, but T-lymphocyte, neutrophil chemotaxis, and cytokine (e.g., interleukin-6 and granulocyte colony–stimulating factor) abnormalities have been suggested.2 Diagnosis is based on the clinical presentation and context together with typical dermatopathologic findings, including a dense neutrophilic infiltrate. Skin lesions may be phasic, but persist typically until appropriate therapy (e.g., corticosteroids, chemotherapy) is administered or the offending drug removed. Malignancy-associated (i.e., paraneoplastic) Sweet’s syndrome accounts for approximately 20% of all cases; these primarily involve hematologic malignancies, most commonly leukemia, but adenocarcinomata have also been implicated.3 Recurrence of Sweet’s syndrome can occur and often heralds relapse of the underlying disease.

References

1. Sweet RD. An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1964;76:349-56.

2. Von den Driesch P. Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:535-56.

3. Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome–a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34.

Cecal carcinoma–associated paraneoplastic Sweet’s syndrome

Based on the tomographic appearance of an “apple core”–like lesion in the right lower quadrant, the patient was referred for colonoscopy, which revealed a malignant-appearing cecal mass (Figure D), with biopsies confirming adenocarcinoma; despite these findings, no bowel-related symptoms were reported. The patient underwent laparoscopic right hemicolectomy, after which the skin lesions began to resolve, and corticosteroids were successfully tapered. The overall presentation was consistent with Sweet’s syndrome, with a paraneoplastic etiology being favored given the clinical scenario, including absence of alternative etiologies and dependence on corticosteroids for control of skin disease until resection of the underlying malignancy was performed.

Sweet’s syndrome was first described in a case series of eight patients published in 1964 by the English dermatologist Dr. Robert Douglas Sweet.1,2 Sweet’s syndrome is characterized by fever, neutrophilia, and sterile erythematous plaques or nodules, which most commonly involve the upper extremities and face and respond to corticosteroid therapy. It may be malignancy associated, drug induced, autoimmune disease related, or idiopathic.2,3 The pathogenesis of Sweet’s syndrome is unclear, but T-lymphocyte, neutrophil chemotaxis, and cytokine (e.g., interleukin-6 and granulocyte colony–stimulating factor) abnormalities have been suggested.2 Diagnosis is based on the clinical presentation and context together with typical dermatopathologic findings, including a dense neutrophilic infiltrate. Skin lesions may be phasic, but persist typically until appropriate therapy (e.g., corticosteroids, chemotherapy) is administered or the offending drug removed. Malignancy-associated (i.e., paraneoplastic) Sweet’s syndrome accounts for approximately 20% of all cases; these primarily involve hematologic malignancies, most commonly leukemia, but adenocarcinomata have also been implicated.3 Recurrence of Sweet’s syndrome can occur and often heralds relapse of the underlying disease.

References

1. Sweet RD. An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1964;76:349-56.

2. Von den Driesch P. Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:535-56.

3. Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome–a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34.

Cecal carcinoma–associated paraneoplastic Sweet’s syndrome

Based on the tomographic appearance of an “apple core”–like lesion in the right lower quadrant, the patient was referred for colonoscopy, which revealed a malignant-appearing cecal mass (Figure D), with biopsies confirming adenocarcinoma; despite these findings, no bowel-related symptoms were reported. The patient underwent laparoscopic right hemicolectomy, after which the skin lesions began to resolve, and corticosteroids were successfully tapered. The overall presentation was consistent with Sweet’s syndrome, with a paraneoplastic etiology being favored given the clinical scenario, including absence of alternative etiologies and dependence on corticosteroids for control of skin disease until resection of the underlying malignancy was performed.

Sweet’s syndrome was first described in a case series of eight patients published in 1964 by the English dermatologist Dr. Robert Douglas Sweet.1,2 Sweet’s syndrome is characterized by fever, neutrophilia, and sterile erythematous plaques or nodules, which most commonly involve the upper extremities and face and respond to corticosteroid therapy. It may be malignancy associated, drug induced, autoimmune disease related, or idiopathic.2,3 The pathogenesis of Sweet’s syndrome is unclear, but T-lymphocyte, neutrophil chemotaxis, and cytokine (e.g., interleukin-6 and granulocyte colony–stimulating factor) abnormalities have been suggested.2 Diagnosis is based on the clinical presentation and context together with typical dermatopathologic findings, including a dense neutrophilic infiltrate. Skin lesions may be phasic, but persist typically until appropriate therapy (e.g., corticosteroids, chemotherapy) is administered or the offending drug removed. Malignancy-associated (i.e., paraneoplastic) Sweet’s syndrome accounts for approximately 20% of all cases; these primarily involve hematologic malignancies, most commonly leukemia, but adenocarcinomata have also been implicated.3 Recurrence of Sweet’s syndrome can occur and often heralds relapse of the underlying disease.

References

1. Sweet RD. An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1964;76:349-56.

2. Von den Driesch P. Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:535-56.

3. Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome–a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34.

What is the diagnosis?

What is Your Diagnosis? - November 2018

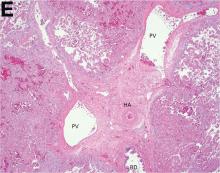

Over the next 6 months she developed progressive liver failure (Model for End-stage Liver Disease score 34), and required several hospitalizations for worsening abdominal pain and debility. Despite the high risk of complications, she agreed to pursue a liver transplant. During the course of surgery, there was significant hemorrhage from tearing of the portal vein (PV) anastomosis and surrounding areas; despite all resuscitative efforts, she went into cardiac arrest and died. The sections of explanted liver revealed soft, spongy parenchyma with blood-filled cyst-like cavities measuring 1-6 mm in diameter (Figure F). The entire liver was affected by vascular malformations (VMs) and there was no evidence of malignancy. On elastin stain, the elastic lamina of the vascular wall appeared thin and disrupted; D2-40 and GLUT1 antibody stains were negative. The hilar PV wall thickness was variable with areas of intramural loose connective tissue separating smooth muscle bundles. This made the PV very friable, which, along with coagulopathy, was the likely cause of uncontrollable intraoperative bleeding. These findings indicate that the vascular spaces were derived from malformation of PV branches.

VMs are rare liver lesions that can be idiopathic or associated with cirrhosis, traumatic injuries, and syndromes such as hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Although not always apparent, VMs are present at birth and grow proportionally with the patient’s age.1 They are usually solitary or multifocal, but rare cases of diffuse hepatic involvement have been reported.2 To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of diffuse hepatic VM in an adult with no evidence of extrahepatic involvement. Diffuse hepatic VM may be confused with diffuse hepatic hemangiomatosis, another rare condition in adults characterized by replacement of the hepatic parenchyma with hemangiomatous lesions, but differs in that it is a vascular tumor and not VM. While vascular tumors, such as hemangioma, are characterized by abnormal endothelial proliferation, VMs develop from abnormal vascular morphogenesis, and are named after the vascular element they closely resemble, namely, capillary, venous, or arterial malformations. Although these are 2 distinct entities, the terms hemangioma and VM have been used indiscriminately and interchangeably in the literature to describe vascular anomalies.1 Most hepatic VMs are asymptomatic, but depending on the extent of involvement, patients may develop high-output heart failure, portal hypertension, and biliary disease.3 Despite extensive liver involvement, our patient did not manifest shunt physiology. The radiographic findings were nonspecific but indicative of diffuse vascular lesions in the liver. Histologic characteristics include dilated, irregular vascular channels, lined by a flat endothelium, separated by liver parenchyma and fibrovascular tissue.2 Histochemical stains for collagen, elastin, and smooth muscle are often used to further characterize VMs. Therapeutic options in focal VMs include sclerotherapy, embolization, and surgical resection. In severe cases with progressive hepatic failure, liver transplantation may be the only feasible option. A case of successful living donor liver transplant in a 14-year-old with VMs involving liver and colon has been described in literature.3 Unfortunately, our patient did not survive the surgery. More reports using accurate terminology to describe hepatic vascular anomalies are needed for further understanding of this rare yet fatal disease.

References

1. George A., Mani V., Noufal A. Update on the classification of hemangioma. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2014;18:S117-20.

2. Sato K., Amanuma M., Fukusato T., et al. Diffuse hepatic vascular malformations with right aortic arch. J Hepatol. 2005;43:1094-5.

3. Hatanaka M., Nakazawa A., Nakano N., et al. Successful living donor liver transplantation for giant extensive venous malformation. Pediatr Transplant. 2014;18:E152-6.

Over the next 6 months she developed progressive liver failure (Model for End-stage Liver Disease score 34), and required several hospitalizations for worsening abdominal pain and debility. Despite the high risk of complications, she agreed to pursue a liver transplant. During the course of surgery, there was significant hemorrhage from tearing of the portal vein (PV) anastomosis and surrounding areas; despite all resuscitative efforts, she went into cardiac arrest and died. The sections of explanted liver revealed soft, spongy parenchyma with blood-filled cyst-like cavities measuring 1-6 mm in diameter (Figure F). The entire liver was affected by vascular malformations (VMs) and there was no evidence of malignancy. On elastin stain, the elastic lamina of the vascular wall appeared thin and disrupted; D2-40 and GLUT1 antibody stains were negative. The hilar PV wall thickness was variable with areas of intramural loose connective tissue separating smooth muscle bundles. This made the PV very friable, which, along with coagulopathy, was the likely cause of uncontrollable intraoperative bleeding. These findings indicate that the vascular spaces were derived from malformation of PV branches.

VMs are rare liver lesions that can be idiopathic or associated with cirrhosis, traumatic injuries, and syndromes such as hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Although not always apparent, VMs are present at birth and grow proportionally with the patient’s age.1 They are usually solitary or multifocal, but rare cases of diffuse hepatic involvement have been reported.2 To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of diffuse hepatic VM in an adult with no evidence of extrahepatic involvement. Diffuse hepatic VM may be confused with diffuse hepatic hemangiomatosis, another rare condition in adults characterized by replacement of the hepatic parenchyma with hemangiomatous lesions, but differs in that it is a vascular tumor and not VM. While vascular tumors, such as hemangioma, are characterized by abnormal endothelial proliferation, VMs develop from abnormal vascular morphogenesis, and are named after the vascular element they closely resemble, namely, capillary, venous, or arterial malformations. Although these are 2 distinct entities, the terms hemangioma and VM have been used indiscriminately and interchangeably in the literature to describe vascular anomalies.1 Most hepatic VMs are asymptomatic, but depending on the extent of involvement, patients may develop high-output heart failure, portal hypertension, and biliary disease.3 Despite extensive liver involvement, our patient did not manifest shunt physiology. The radiographic findings were nonspecific but indicative of diffuse vascular lesions in the liver. Histologic characteristics include dilated, irregular vascular channels, lined by a flat endothelium, separated by liver parenchyma and fibrovascular tissue.2 Histochemical stains for collagen, elastin, and smooth muscle are often used to further characterize VMs. Therapeutic options in focal VMs include sclerotherapy, embolization, and surgical resection. In severe cases with progressive hepatic failure, liver transplantation may be the only feasible option. A case of successful living donor liver transplant in a 14-year-old with VMs involving liver and colon has been described in literature.3 Unfortunately, our patient did not survive the surgery. More reports using accurate terminology to describe hepatic vascular anomalies are needed for further understanding of this rare yet fatal disease.

References

1. George A., Mani V., Noufal A. Update on the classification of hemangioma. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2014;18:S117-20.

2. Sato K., Amanuma M., Fukusato T., et al. Diffuse hepatic vascular malformations with right aortic arch. J Hepatol. 2005;43:1094-5.

3. Hatanaka M., Nakazawa A., Nakano N., et al. Successful living donor liver transplantation for giant extensive venous malformation. Pediatr Transplant. 2014;18:E152-6.

Over the next 6 months she developed progressive liver failure (Model for End-stage Liver Disease score 34), and required several hospitalizations for worsening abdominal pain and debility. Despite the high risk of complications, she agreed to pursue a liver transplant. During the course of surgery, there was significant hemorrhage from tearing of the portal vein (PV) anastomosis and surrounding areas; despite all resuscitative efforts, she went into cardiac arrest and died. The sections of explanted liver revealed soft, spongy parenchyma with blood-filled cyst-like cavities measuring 1-6 mm in diameter (Figure F). The entire liver was affected by vascular malformations (VMs) and there was no evidence of malignancy. On elastin stain, the elastic lamina of the vascular wall appeared thin and disrupted; D2-40 and GLUT1 antibody stains were negative. The hilar PV wall thickness was variable with areas of intramural loose connective tissue separating smooth muscle bundles. This made the PV very friable, which, along with coagulopathy, was the likely cause of uncontrollable intraoperative bleeding. These findings indicate that the vascular spaces were derived from malformation of PV branches.

VMs are rare liver lesions that can be idiopathic or associated with cirrhosis, traumatic injuries, and syndromes such as hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Although not always apparent, VMs are present at birth and grow proportionally with the patient’s age.1 They are usually solitary or multifocal, but rare cases of diffuse hepatic involvement have been reported.2 To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of diffuse hepatic VM in an adult with no evidence of extrahepatic involvement. Diffuse hepatic VM may be confused with diffuse hepatic hemangiomatosis, another rare condition in adults characterized by replacement of the hepatic parenchyma with hemangiomatous lesions, but differs in that it is a vascular tumor and not VM. While vascular tumors, such as hemangioma, are characterized by abnormal endothelial proliferation, VMs develop from abnormal vascular morphogenesis, and are named after the vascular element they closely resemble, namely, capillary, venous, or arterial malformations. Although these are 2 distinct entities, the terms hemangioma and VM have been used indiscriminately and interchangeably in the literature to describe vascular anomalies.1 Most hepatic VMs are asymptomatic, but depending on the extent of involvement, patients may develop high-output heart failure, portal hypertension, and biliary disease.3 Despite extensive liver involvement, our patient did not manifest shunt physiology. The radiographic findings were nonspecific but indicative of diffuse vascular lesions in the liver. Histologic characteristics include dilated, irregular vascular channels, lined by a flat endothelium, separated by liver parenchyma and fibrovascular tissue.2 Histochemical stains for collagen, elastin, and smooth muscle are often used to further characterize VMs. Therapeutic options in focal VMs include sclerotherapy, embolization, and surgical resection. In severe cases with progressive hepatic failure, liver transplantation may be the only feasible option. A case of successful living donor liver transplant in a 14-year-old with VMs involving liver and colon has been described in literature.3 Unfortunately, our patient did not survive the surgery. More reports using accurate terminology to describe hepatic vascular anomalies are needed for further understanding of this rare yet fatal disease.

References

1. George A., Mani V., Noufal A. Update on the classification of hemangioma. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2014;18:S117-20.

2. Sato K., Amanuma M., Fukusato T., et al. Diffuse hepatic vascular malformations with right aortic arch. J Hepatol. 2005;43:1094-5.

3. Hatanaka M., Nakazawa A., Nakano N., et al. Successful living donor liver transplantation for giant extensive venous malformation. Pediatr Transplant. 2014;18:E152-6.

A 50-year-old Guyanese woman was found to have abnormal liver tests on routine testing with total bilirubin, 1.8 mg/dL (normal, 0.2–1.2); alkaline phosphatase, 189 U/L (normal, 47–154); aspartate transaminase, 57 U/L (normal, 11–42); and alanine transaminase, 33 U/L (normal, 0–20).

Published previously in Gastroenterology (2016;151[6]:1081-2).

What's your diagnosis? - October 2018

Idiopathic myointimal hyperplasia of the mesenteric veins

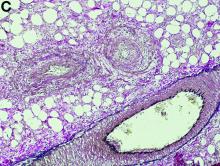

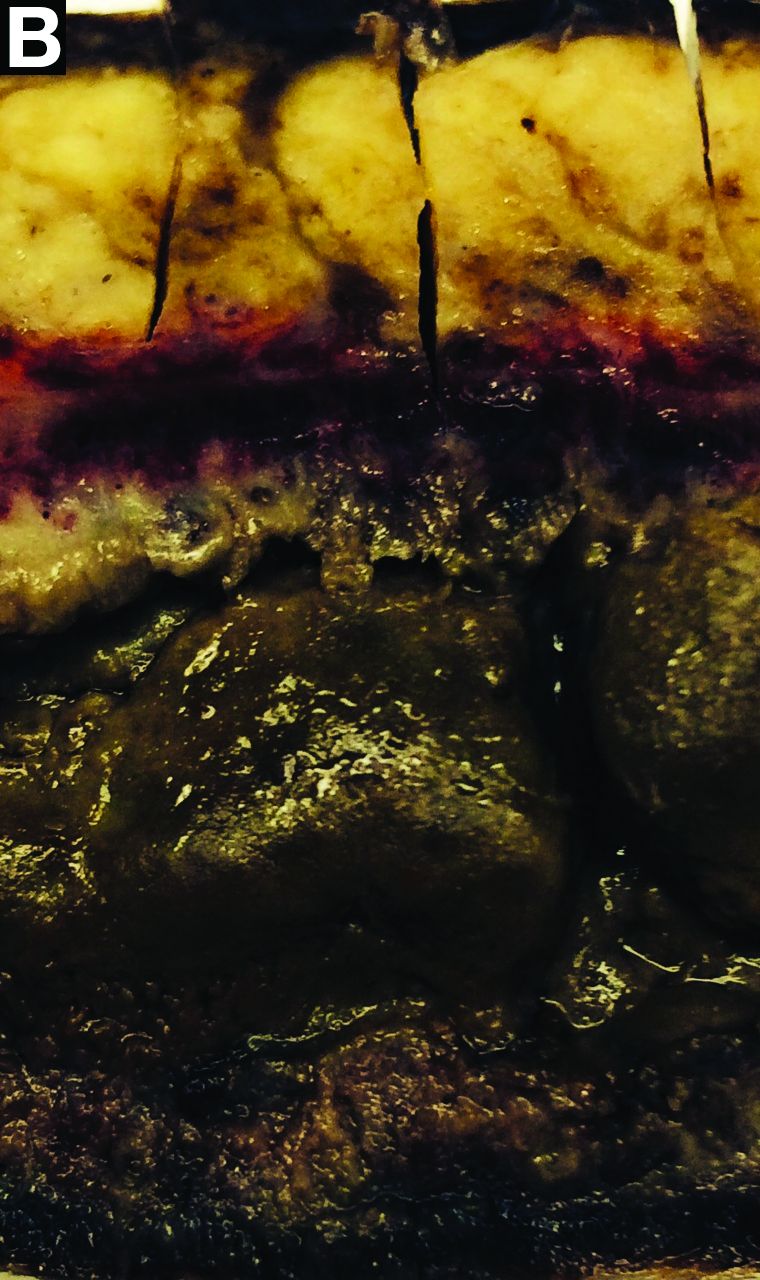

Gross examination of the rectosigmoid colon resected from this patient demonstrated transmural fibrosis. The mucosa was necrotic and hemorrhagic with a granular and cobblestone pattern (Figure B). Histopathologic examination of the mucosa revealed veins with myointimal hyperplasia with sparing of arterial vasculature (Figure C; stain: elastin; original magnification, ×10). The combined findings via endoscopy and histopathology confirmed the diagnosis of idiopathic myointimal hyperplasia of the mesenteric veins (IMHMV).

IMHMV is a rare cause of proctosigmoiditis first described in a case series of 4 patients in 1991 by Genta and Haggitt.1 Owing to its clinical presentation of lower quadrant abdominal pain, diarrhea, hematochezia, and mucous in the stools, the diagnosis is often mistaken for inflammatory bowel disease. However, the endoscopic and pathologic findings of IHMVH resemble ischemic colitis. IMHMV is refractory to medical treatment and its definitive diagnosis and curative management involves surgical resection of the involved segment (often the rectosigmoid colon). The precise pathophysiology of IMHMV is unclear. Histopathologic analysis of veins in the involved segment of colon can demonstrate changes similar to those of failed saphenous grafts from coronary artery bypass.2 Myointimal hyperplasia of the mesenteric veins occurs (best identified with elastin stain on histopathology) with near total occlusion of the venous lumen and without any associated inflammatory infiltrate or arterial involvement.3

After colectomy, our patient’s abdominal symptoms resolved and follow-up colonoscopy at 6 months did not reveal recurrence of IMHMV, at which time, the patient underwent take-down of his colostomy. In the year after colostomy take-down, the patient showed no clinical or endoscopic signs of colitis while off of all medical therapies. Here, we present the first case of a successful take-down of a curative colostomy for an IMHMV patient, a treatment course not described previously in the literature. Prompt diagnosis and timely surgical intervention may allow for avoidance of permanent colostomy in patients with IMHMV.

References

1. Genta R.M., Haggitt, R.C. Idiopathic myointimal hyperplasia of mesenteric veins. Gastroenterology. 1991;101:533-9.

2. Abu-Alfa A.K., Ayer U., West A.B. Mucosal biopsy findings and venous abnormalities in idiopathic myointimal hyperplasia of the mesenteric veins. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1271-8.

3. Chiang C.K., Lee C.L., Huang C.S., et al. A rare cause of ischemic proctosigmoiditis: Idiopathic myointimal hyperplasia of mesenteric veins. Endoscopy. 2012;44:54-5.

Idiopathic myointimal hyperplasia of the mesenteric veins

Gross examination of the rectosigmoid colon resected from this patient demonstrated transmural fibrosis. The mucosa was necrotic and hemorrhagic with a granular and cobblestone pattern (Figure B). Histopathologic examination of the mucosa revealed veins with myointimal hyperplasia with sparing of arterial vasculature (Figure C; stain: elastin; original magnification, ×10). The combined findings via endoscopy and histopathology confirmed the diagnosis of idiopathic myointimal hyperplasia of the mesenteric veins (IMHMV).

IMHMV is a rare cause of proctosigmoiditis first described in a case series of 4 patients in 1991 by Genta and Haggitt.1 Owing to its clinical presentation of lower quadrant abdominal pain, diarrhea, hematochezia, and mucous in the stools, the diagnosis is often mistaken for inflammatory bowel disease. However, the endoscopic and pathologic findings of IHMVH resemble ischemic colitis. IMHMV is refractory to medical treatment and its definitive diagnosis and curative management involves surgical resection of the involved segment (often the rectosigmoid colon). The precise pathophysiology of IMHMV is unclear. Histopathologic analysis of veins in the involved segment of colon can demonstrate changes similar to those of failed saphenous grafts from coronary artery bypass.2 Myointimal hyperplasia of the mesenteric veins occurs (best identified with elastin stain on histopathology) with near total occlusion of the venous lumen and without any associated inflammatory infiltrate or arterial involvement.3

After colectomy, our patient’s abdominal symptoms resolved and follow-up colonoscopy at 6 months did not reveal recurrence of IMHMV, at which time, the patient underwent take-down of his colostomy. In the year after colostomy take-down, the patient showed no clinical or endoscopic signs of colitis while off of all medical therapies. Here, we present the first case of a successful take-down of a curative colostomy for an IMHMV patient, a treatment course not described previously in the literature. Prompt diagnosis and timely surgical intervention may allow for avoidance of permanent colostomy in patients with IMHMV.

References

1. Genta R.M., Haggitt, R.C. Idiopathic myointimal hyperplasia of mesenteric veins. Gastroenterology. 1991;101:533-9.

2. Abu-Alfa A.K., Ayer U., West A.B. Mucosal biopsy findings and venous abnormalities in idiopathic myointimal hyperplasia of the mesenteric veins. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1271-8.

3. Chiang C.K., Lee C.L., Huang C.S., et al. A rare cause of ischemic proctosigmoiditis: Idiopathic myointimal hyperplasia of mesenteric veins. Endoscopy. 2012;44:54-5.

Idiopathic myointimal hyperplasia of the mesenteric veins

Gross examination of the rectosigmoid colon resected from this patient demonstrated transmural fibrosis. The mucosa was necrotic and hemorrhagic with a granular and cobblestone pattern (Figure B). Histopathologic examination of the mucosa revealed veins with myointimal hyperplasia with sparing of arterial vasculature (Figure C; stain: elastin; original magnification, ×10). The combined findings via endoscopy and histopathology confirmed the diagnosis of idiopathic myointimal hyperplasia of the mesenteric veins (IMHMV).

IMHMV is a rare cause of proctosigmoiditis first described in a case series of 4 patients in 1991 by Genta and Haggitt.1 Owing to its clinical presentation of lower quadrant abdominal pain, diarrhea, hematochezia, and mucous in the stools, the diagnosis is often mistaken for inflammatory bowel disease. However, the endoscopic and pathologic findings of IHMVH resemble ischemic colitis. IMHMV is refractory to medical treatment and its definitive diagnosis and curative management involves surgical resection of the involved segment (often the rectosigmoid colon). The precise pathophysiology of IMHMV is unclear. Histopathologic analysis of veins in the involved segment of colon can demonstrate changes similar to those of failed saphenous grafts from coronary artery bypass.2 Myointimal hyperplasia of the mesenteric veins occurs (best identified with elastin stain on histopathology) with near total occlusion of the venous lumen and without any associated inflammatory infiltrate or arterial involvement.3

After colectomy, our patient’s abdominal symptoms resolved and follow-up colonoscopy at 6 months did not reveal recurrence of IMHMV, at which time, the patient underwent take-down of his colostomy. In the year after colostomy take-down, the patient showed no clinical or endoscopic signs of colitis while off of all medical therapies. Here, we present the first case of a successful take-down of a curative colostomy for an IMHMV patient, a treatment course not described previously in the literature. Prompt diagnosis and timely surgical intervention may allow for avoidance of permanent colostomy in patients with IMHMV.

References

1. Genta R.M., Haggitt, R.C. Idiopathic myointimal hyperplasia of mesenteric veins. Gastroenterology. 1991;101:533-9.

2. Abu-Alfa A.K., Ayer U., West A.B. Mucosal biopsy findings and venous abnormalities in idiopathic myointimal hyperplasia of the mesenteric veins. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1271-8.

3. Chiang C.K., Lee C.L., Huang C.S., et al. A rare cause of ischemic proctosigmoiditis: Idiopathic myointimal hyperplasia of mesenteric veins. Endoscopy. 2012;44:54-5.

What's your diagnosis? - September 2018

Endovascular walled-off pancreatic necrosis complicating a pancreatic duct-portal vein fistula

Pancreatic fistula occurs primarily as a result of abdominal trauma, pancreatic surgery, or disruption of the pancreatic duct. In the vast majority of the cases, the latter is encountered in the context of chronic pancreatitis, and results in chronic pancreatic or peripancreatic fluid or necrotic collections. Rarely, such ductal disruption leads to a direct communication between the ruptured duct and the portal vein lumen. Such pancreas-portal venous fistulas are extremely rare, with less than 20 cases reported in published literature.1 The location of the fistula is within the head of the pancreas in most cases, and it is associated with intrapancreatic necrotic collection in close proximity to the portal vein, as in the present case. The intravascular flow of pancreatic enzymes leads to local and progressively extensive portal vein thrombosis. Importantly, most portal vein thromboses in the context of acute or chronic pancreatitis do not result from pancreas-portal venous fistula, and are explained by local vascular compression by the inflammatory pancreatic head, and acquired coagulation abnormalities owing to the pancreatitis. In case of fistula, the resulting high blood level of the pancreatic enzymes may lead to a range of clinical presentations, from vague abdominal pain to disseminated fat necrosis. Painful erythematous lesions on the lower extremities and arthritis have also been described. The present case is an exceptional complication of pancreatic duct-portal vein fistula, with endovascular organization of walled-off pancreatic necrosis.2 The direct visualization of the fistula is difficult, endoscopic retrograde or, more frequently, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography being the most useful technique.3

Ultrasound imaging can be useful by showing the heterogeneous yet hypoechoic content of the portal venous system. Percutaneous transhepatic puncture has also been described, and is performed, as in our case, to obtain fluid sample and to perform evacuation of fluid/drainage if necessary. Percutaneous puncture may also provide precise extension of the portal venous invasion. The management of patients with pancreatic-portal vein fistula is poorly codified and relies on individual clinical and imaging analysis. Early surgical intervention has been described in patients with disseminated fat necrosis to limit morbidity and prevent mortality. Later in the evolution of the disease, surgery can be performed if the fistula remains active to alleviate the patient's symptoms and prevent future complications. Finally, conservative treatment can be proposed in selected patients with dried up fistula, as in the present report.

References

1. Brown A., Malden E., Kugelmas M., et al. Diagnosis of pancreatic duct-portal vein fistula; A case report and review of the literature. J Radiol Case Rep. 2014;8:31-8.

2. Banks P.A., Bollen T.L., Dervenis C., et al. Classification of acute pancreatitis-2012: Revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102-11.

3. Yoon S.E., Lee Y.H., Yoon K.H., et al. Spontaneous pancreatic pseudocyst-portal vein fistula presenting with pancreatic ascites: Strength of MR cholangiopancreatography. Br J Radiol. 2008;81:e13-6.

Endovascular walled-off pancreatic necrosis complicating a pancreatic duct-portal vein fistula

Pancreatic fistula occurs primarily as a result of abdominal trauma, pancreatic surgery, or disruption of the pancreatic duct. In the vast majority of the cases, the latter is encountered in the context of chronic pancreatitis, and results in chronic pancreatic or peripancreatic fluid or necrotic collections. Rarely, such ductal disruption leads to a direct communication between the ruptured duct and the portal vein lumen. Such pancreas-portal venous fistulas are extremely rare, with less than 20 cases reported in published literature.1 The location of the fistula is within the head of the pancreas in most cases, and it is associated with intrapancreatic necrotic collection in close proximity to the portal vein, as in the present case. The intravascular flow of pancreatic enzymes leads to local and progressively extensive portal vein thrombosis. Importantly, most portal vein thromboses in the context of acute or chronic pancreatitis do not result from pancreas-portal venous fistula, and are explained by local vascular compression by the inflammatory pancreatic head, and acquired coagulation abnormalities owing to the pancreatitis. In case of fistula, the resulting high blood level of the pancreatic enzymes may lead to a range of clinical presentations, from vague abdominal pain to disseminated fat necrosis. Painful erythematous lesions on the lower extremities and arthritis have also been described. The present case is an exceptional complication of pancreatic duct-portal vein fistula, with endovascular organization of walled-off pancreatic necrosis.2 The direct visualization of the fistula is difficult, endoscopic retrograde or, more frequently, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography being the most useful technique.3

Ultrasound imaging can be useful by showing the heterogeneous yet hypoechoic content of the portal venous system. Percutaneous transhepatic puncture has also been described, and is performed, as in our case, to obtain fluid sample and to perform evacuation of fluid/drainage if necessary. Percutaneous puncture may also provide precise extension of the portal venous invasion. The management of patients with pancreatic-portal vein fistula is poorly codified and relies on individual clinical and imaging analysis. Early surgical intervention has been described in patients with disseminated fat necrosis to limit morbidity and prevent mortality. Later in the evolution of the disease, surgery can be performed if the fistula remains active to alleviate the patient's symptoms and prevent future complications. Finally, conservative treatment can be proposed in selected patients with dried up fistula, as in the present report.

References

1. Brown A., Malden E., Kugelmas M., et al. Diagnosis of pancreatic duct-portal vein fistula; A case report and review of the literature. J Radiol Case Rep. 2014;8:31-8.

2. Banks P.A., Bollen T.L., Dervenis C., et al. Classification of acute pancreatitis-2012: Revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102-11.

3. Yoon S.E., Lee Y.H., Yoon K.H., et al. Spontaneous pancreatic pseudocyst-portal vein fistula presenting with pancreatic ascites: Strength of MR cholangiopancreatography. Br J Radiol. 2008;81:e13-6.

Endovascular walled-off pancreatic necrosis complicating a pancreatic duct-portal vein fistula

Pancreatic fistula occurs primarily as a result of abdominal trauma, pancreatic surgery, or disruption of the pancreatic duct. In the vast majority of the cases, the latter is encountered in the context of chronic pancreatitis, and results in chronic pancreatic or peripancreatic fluid or necrotic collections. Rarely, such ductal disruption leads to a direct communication between the ruptured duct and the portal vein lumen. Such pancreas-portal venous fistulas are extremely rare, with less than 20 cases reported in published literature.1 The location of the fistula is within the head of the pancreas in most cases, and it is associated with intrapancreatic necrotic collection in close proximity to the portal vein, as in the present case. The intravascular flow of pancreatic enzymes leads to local and progressively extensive portal vein thrombosis. Importantly, most portal vein thromboses in the context of acute or chronic pancreatitis do not result from pancreas-portal venous fistula, and are explained by local vascular compression by the inflammatory pancreatic head, and acquired coagulation abnormalities owing to the pancreatitis. In case of fistula, the resulting high blood level of the pancreatic enzymes may lead to a range of clinical presentations, from vague abdominal pain to disseminated fat necrosis. Painful erythematous lesions on the lower extremities and arthritis have also been described. The present case is an exceptional complication of pancreatic duct-portal vein fistula, with endovascular organization of walled-off pancreatic necrosis.2 The direct visualization of the fistula is difficult, endoscopic retrograde or, more frequently, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography being the most useful technique.3

Ultrasound imaging can be useful by showing the heterogeneous yet hypoechoic content of the portal venous system. Percutaneous transhepatic puncture has also been described, and is performed, as in our case, to obtain fluid sample and to perform evacuation of fluid/drainage if necessary. Percutaneous puncture may also provide precise extension of the portal venous invasion. The management of patients with pancreatic-portal vein fistula is poorly codified and relies on individual clinical and imaging analysis. Early surgical intervention has been described in patients with disseminated fat necrosis to limit morbidity and prevent mortality. Later in the evolution of the disease, surgery can be performed if the fistula remains active to alleviate the patient's symptoms and prevent future complications. Finally, conservative treatment can be proposed in selected patients with dried up fistula, as in the present report.

References

1. Brown A., Malden E., Kugelmas M., et al. Diagnosis of pancreatic duct-portal vein fistula; A case report and review of the literature. J Radiol Case Rep. 2014;8:31-8.

2. Banks P.A., Bollen T.L., Dervenis C., et al. Classification of acute pancreatitis-2012: Revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102-11.

3. Yoon S.E., Lee Y.H., Yoon K.H., et al. Spontaneous pancreatic pseudocyst-portal vein fistula presenting with pancreatic ascites: Strength of MR cholangiopancreatography. Br J Radiol. 2008;81:e13-6.

A 51-year-old man with a history of chronic pancreatitis presented with fatigue, weight loss, and right abdominal pain. He reported excessive alcohol consumption (> 200 g of alcohol per day during the past 35 years), active tobacco smoking (70 pack-years), and diabetes mellitus treated by insulin therapy. He had suffered from recurrent epigastric pain, left unexplored, for several weeks. Abdominal examination revealed no anomaly. Laboratory test results showed serum lipase 146 U/L (normal, < 78), alkaline phosphatase 477 U/L (normal, < 130), gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase 503 U/L (normal, < 55), albumin 23 g/L (normal, 40-49), and prealbumin 0.11 g/L (normal, 0.22-0.39).

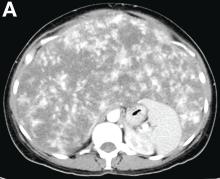

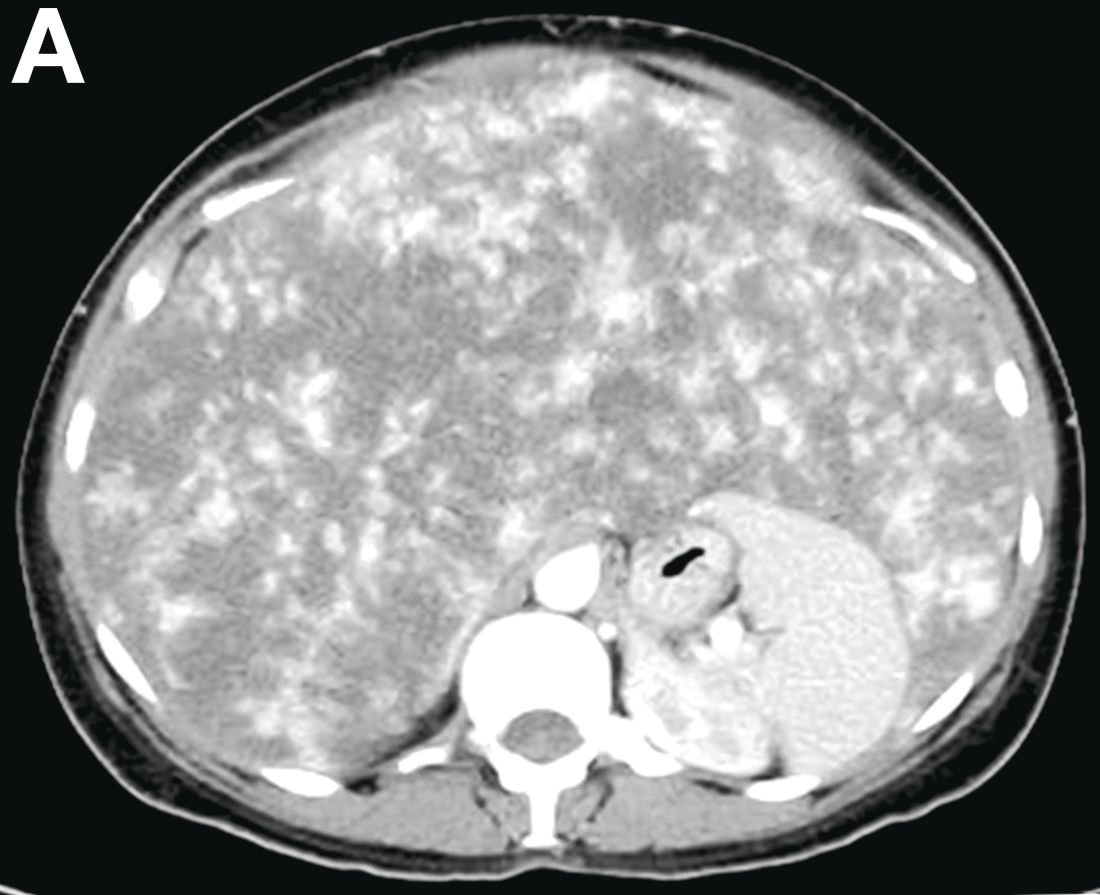

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scanning showed features of chronic pancreatitis including pancreatic atrophy, parenchymal calcifications, marked peripancreatic fat stranding, and cephalic hypoattenuating well-delineated collection (Figure A).

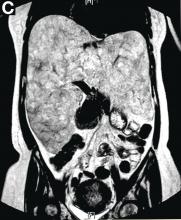

There was a chronic obstruction of the portal vein that was surrounded by numerous tortuous venous channels (Figure B). The entire intrahepatic portal branches were occluded, the right and left portal branches showed marked dilatation with a lumen filled with fluid-like material (mean density, 18 Hounsfield units), and no contrast uptake (Figure C).

Portal vein walls were thickened and showed contrast enhancement (Figure D). The superior mesenteric vein was also thrombosed, whereas the splenic vein remained patent. Bile ducts were unnoticeable.

Ultrasound-guided transhepatic puncture of the left portal branch was performed and allowed for the aspiration of a brown fluid. Analysis showed lipase 89,990 UI/dL and amylase 43,125 UI/dL. The patient was treated by parenteral nutrition, anticoagulation therapy, and somatostatin analogues. The patient is doing well at the 6-month follow-up.

August 2018 - What's your diagnosis?

Mature cystic teratoma of the ovary invading the rectum

The patient was diagnosed with an ovarian dermoid cyst that was fistulating into the rectum. In view of these findings, a decision was made for surgical intervention to remove this lesion. A diagnostic laparoscopy, robotic-assisted left salpingo-oopherectomy, excision of cystorectal fistula, proctotomy, and primary repair of the rectal defect was performed. Intraoperative findings include a large left ovarian dermoid cyst with sebaceous content and hair fistulating into the upper rectum just above the rectovaginal pouch, and was adherent to surrounding structures. After excision of the fistula, the anterior rectal wall defect measured 1.5 cm and was closed primarily. Histology revealed a mature cystic teratoma and a fistula tract in the rectum; no malignant features were found. The patient had an uneventful recovery and was well at follow-up.

Mature cystic teratomas of the ovary, also referred to as ovarian dermoid cysts, are benign germ cell tumors of the ovary. These account for 10%-20% of all ovarian neoplasms.1 These are commonly asymptomatic and are found incidentally on imaging studies performed for other indications.2 Complications of these tumors include torsion (16%), rupture (0.5%), and malignant degeneration (2%-6%).3 Rectal invasion via fistulation by these lesions are rare; to date, six cases of colorectal involvement by mature cystic teratomas of the ovary are reported in the literature. These fistulas are a result of rupture of the cyst into the pouch of Douglas, which leads to an intense inflammatory response that results in fistulation, rather than freely into the peritoneum.3 These are therefore undetected until symptoms such as diarrhea or passage of cystic contents (mucus, hair, teeth) develop. The management of mature cystic teratomas of the ovary with symptoms or complications commonly involves surgical intervention to resect the involved ovary and address other pathology.

References

1. Rajaganeshan R., Wang H., Abouleid A., et al. Conservative surgery in the management of a benign ovarian cystic teratoma presenting as a rectal mass: a case report. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2001;93 e46-8.

2. Wichremasinghe D., Samarasekera D. A benign teratoma of the ovary fistulating into the rectum. Ceylon Med J. 2010;55:133.

3. Stern J.L., Buscema J., Rosenshein N.B., et al. Spontaneous rupture of benign cystic teratomas. Obstet Gynecol. 1981;57:363-6.

Mature cystic teratoma of the ovary invading the rectum

The patient was diagnosed with an ovarian dermoid cyst that was fistulating into the rectum. In view of these findings, a decision was made for surgical intervention to remove this lesion. A diagnostic laparoscopy, robotic-assisted left salpingo-oopherectomy, excision of cystorectal fistula, proctotomy, and primary repair of the rectal defect was performed. Intraoperative findings include a large left ovarian dermoid cyst with sebaceous content and hair fistulating into the upper rectum just above the rectovaginal pouch, and was adherent to surrounding structures. After excision of the fistula, the anterior rectal wall defect measured 1.5 cm and was closed primarily. Histology revealed a mature cystic teratoma and a fistula tract in the rectum; no malignant features were found. The patient had an uneventful recovery and was well at follow-up.

Mature cystic teratomas of the ovary, also referred to as ovarian dermoid cysts, are benign germ cell tumors of the ovary. These account for 10%-20% of all ovarian neoplasms.1 These are commonly asymptomatic and are found incidentally on imaging studies performed for other indications.2 Complications of these tumors include torsion (16%), rupture (0.5%), and malignant degeneration (2%-6%).3 Rectal invasion via fistulation by these lesions are rare; to date, six cases of colorectal involvement by mature cystic teratomas of the ovary are reported in the literature. These fistulas are a result of rupture of the cyst into the pouch of Douglas, which leads to an intense inflammatory response that results in fistulation, rather than freely into the peritoneum.3 These are therefore undetected until symptoms such as diarrhea or passage of cystic contents (mucus, hair, teeth) develop. The management of mature cystic teratomas of the ovary with symptoms or complications commonly involves surgical intervention to resect the involved ovary and address other pathology.

References

1. Rajaganeshan R., Wang H., Abouleid A., et al. Conservative surgery in the management of a benign ovarian cystic teratoma presenting as a rectal mass: a case report. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2001;93 e46-8.

2. Wichremasinghe D., Samarasekera D. A benign teratoma of the ovary fistulating into the rectum. Ceylon Med J. 2010;55:133.

3. Stern J.L., Buscema J., Rosenshein N.B., et al. Spontaneous rupture of benign cystic teratomas. Obstet Gynecol. 1981;57:363-6.

Mature cystic teratoma of the ovary invading the rectum

The patient was diagnosed with an ovarian dermoid cyst that was fistulating into the rectum. In view of these findings, a decision was made for surgical intervention to remove this lesion. A diagnostic laparoscopy, robotic-assisted left salpingo-oopherectomy, excision of cystorectal fistula, proctotomy, and primary repair of the rectal defect was performed. Intraoperative findings include a large left ovarian dermoid cyst with sebaceous content and hair fistulating into the upper rectum just above the rectovaginal pouch, and was adherent to surrounding structures. After excision of the fistula, the anterior rectal wall defect measured 1.5 cm and was closed primarily. Histology revealed a mature cystic teratoma and a fistula tract in the rectum; no malignant features were found. The patient had an uneventful recovery and was well at follow-up.

Mature cystic teratomas of the ovary, also referred to as ovarian dermoid cysts, are benign germ cell tumors of the ovary. These account for 10%-20% of all ovarian neoplasms.1 These are commonly asymptomatic and are found incidentally on imaging studies performed for other indications.2 Complications of these tumors include torsion (16%), rupture (0.5%), and malignant degeneration (2%-6%).3 Rectal invasion via fistulation by these lesions are rare; to date, six cases of colorectal involvement by mature cystic teratomas of the ovary are reported in the literature. These fistulas are a result of rupture of the cyst into the pouch of Douglas, which leads to an intense inflammatory response that results in fistulation, rather than freely into the peritoneum.3 These are therefore undetected until symptoms such as diarrhea or passage of cystic contents (mucus, hair, teeth) develop. The management of mature cystic teratomas of the ovary with symptoms or complications commonly involves surgical intervention to resect the involved ovary and address other pathology.

References

1. Rajaganeshan R., Wang H., Abouleid A., et al. Conservative surgery in the management of a benign ovarian cystic teratoma presenting as a rectal mass: a case report. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2001;93 e46-8.

2. Wichremasinghe D., Samarasekera D. A benign teratoma of the ovary fistulating into the rectum. Ceylon Med J. 2010;55:133.

3. Stern J.L., Buscema J., Rosenshein N.B., et al. Spontaneous rupture of benign cystic teratomas. Obstet Gynecol. 1981;57:363-6.

What's your diagnosis? - July 2018

Polycystic pancreas

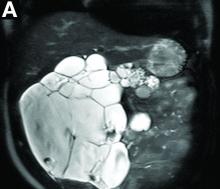

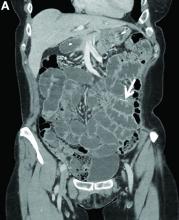

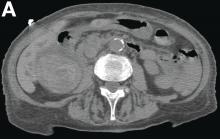

Cross-sectional imaging revealed the diagnosis of polycystic pancreas (diffuse cystic degeneration of the whole organ) with giant cysts in the head and multiple cysts across the whole organ in the absence of concomitant kidney or liver cysts (Figure A, B).

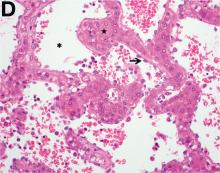

The patient underwent an endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration before the operation, and a mucinous cystic neoplasm was documented. A total duodenopancreatosplenectomy followed. The postoperative course was uneventful. Histology showed multiple cysts of variable diameter lined by monolayer flattened or cuboidal epithelium without atypia and confirmed the diagnosis of polycystic pancreas (Figures D, E; stain: hematoxylin and eosin; original magnifications: ×100 and ×200, respectively).

Genetic testing was negative for von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease. The patient remains in good general condition under diabetes management and oral administration of pancreatic enzymes 45 months 4 years after pancreatectomy. Magnetic resonance imaging of the central nervous system and abdomen were without pathologic findings.

Although pancreatic cysts are very common, a diffuse cystic degeneration of the pancreas in the form of polycystic pancreas is very infrequent and has been described in patients with VHL disease.1 It is almost always associated with multiple renal cysts.1 Genetic testing for VHL disease is suggested in all cases presenting with multiple pancreatic cysts by some investigators.2 It has an accuracy greater than 80%, which reaches 95%-100% in patients who fulfill the clinical criteria for VHL disease.3

The novelty of this case is double; to the best of our knowledge, polycystic pancreas with such a volume (cysts up to 25 cm) has not yet been documented in the literature and has not been at all described in the absence of VHL disease up to now.

References

1. Leung R., Biswas S., Duncan M. et al. Imaging features of Von Hippel-Lindau disease. Radiographics. 2008;28:65-79.

2. Kapur V. Brower S.T. Cystic replacement of pancreas in patient with von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. Gastrointest Cancer Res. 2013;6:25-6.

3. Nielsen S.M., Rhodes L., Blanco I. et al. Von Hippel-Lindau disease: genetics and role of genetic counseling in a multiple neoplasia syndrome. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2172-81.

Polycystic pancreas

Cross-sectional imaging revealed the diagnosis of polycystic pancreas (diffuse cystic degeneration of the whole organ) with giant cysts in the head and multiple cysts across the whole organ in the absence of concomitant kidney or liver cysts (Figure A, B).

The patient underwent an endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration before the operation, and a mucinous cystic neoplasm was documented. A total duodenopancreatosplenectomy followed. The postoperative course was uneventful. Histology showed multiple cysts of variable diameter lined by monolayer flattened or cuboidal epithelium without atypia and confirmed the diagnosis of polycystic pancreas (Figures D, E; stain: hematoxylin and eosin; original magnifications: ×100 and ×200, respectively).

Genetic testing was negative for von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease. The patient remains in good general condition under diabetes management and oral administration of pancreatic enzymes 45 months 4 years after pancreatectomy. Magnetic resonance imaging of the central nervous system and abdomen were without pathologic findings.

Although pancreatic cysts are very common, a diffuse cystic degeneration of the pancreas in the form of polycystic pancreas is very infrequent and has been described in patients with VHL disease.1 It is almost always associated with multiple renal cysts.1 Genetic testing for VHL disease is suggested in all cases presenting with multiple pancreatic cysts by some investigators.2 It has an accuracy greater than 80%, which reaches 95%-100% in patients who fulfill the clinical criteria for VHL disease.3

The novelty of this case is double; to the best of our knowledge, polycystic pancreas with such a volume (cysts up to 25 cm) has not yet been documented in the literature and has not been at all described in the absence of VHL disease up to now.

References

1. Leung R., Biswas S., Duncan M. et al. Imaging features of Von Hippel-Lindau disease. Radiographics. 2008;28:65-79.

2. Kapur V. Brower S.T. Cystic replacement of pancreas in patient with von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. Gastrointest Cancer Res. 2013;6:25-6.

3. Nielsen S.M., Rhodes L., Blanco I. et al. Von Hippel-Lindau disease: genetics and role of genetic counseling in a multiple neoplasia syndrome. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2172-81.

Polycystic pancreas

Cross-sectional imaging revealed the diagnosis of polycystic pancreas (diffuse cystic degeneration of the whole organ) with giant cysts in the head and multiple cysts across the whole organ in the absence of concomitant kidney or liver cysts (Figure A, B).

The patient underwent an endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration before the operation, and a mucinous cystic neoplasm was documented. A total duodenopancreatosplenectomy followed. The postoperative course was uneventful. Histology showed multiple cysts of variable diameter lined by monolayer flattened or cuboidal epithelium without atypia and confirmed the diagnosis of polycystic pancreas (Figures D, E; stain: hematoxylin and eosin; original magnifications: ×100 and ×200, respectively).

Genetic testing was negative for von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease. The patient remains in good general condition under diabetes management and oral administration of pancreatic enzymes 45 months 4 years after pancreatectomy. Magnetic resonance imaging of the central nervous system and abdomen were without pathologic findings.

Although pancreatic cysts are very common, a diffuse cystic degeneration of the pancreas in the form of polycystic pancreas is very infrequent and has been described in patients with VHL disease.1 It is almost always associated with multiple renal cysts.1 Genetic testing for VHL disease is suggested in all cases presenting with multiple pancreatic cysts by some investigators.2 It has an accuracy greater than 80%, which reaches 95%-100% in patients who fulfill the clinical criteria for VHL disease.3

The novelty of this case is double; to the best of our knowledge, polycystic pancreas with such a volume (cysts up to 25 cm) has not yet been documented in the literature and has not been at all described in the absence of VHL disease up to now.

References

1. Leung R., Biswas S., Duncan M. et al. Imaging features of Von Hippel-Lindau disease. Radiographics. 2008;28:65-79.

2. Kapur V. Brower S.T. Cystic replacement of pancreas in patient with von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. Gastrointest Cancer Res. 2013;6:25-6.

3. Nielsen S.M., Rhodes L., Blanco I. et al. Von Hippel-Lindau disease: genetics and role of genetic counseling in a multiple neoplasia syndrome. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2172-81.

June 2018 - What's your diagnosis?

By Guilherme Piovezani Ramos, MD, Seth Sweetser, MD, and John B. Kisiel, MD

Recurrent SBO owing to contained perforation after accidental ingestion of a metal bristle of a barbecue grill brush

SBO may be caused by a variety of intrinsic or extrinsic lesions. Postoperative adhesions (60%) and malignant tumors (20%) are responsible for the majority of cases in the United States. CD accounts for approximately 5% of all SBOs.1 The unusual root cause of our patient's SBO was unintentional ingestion of a foreign body.

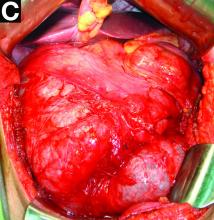

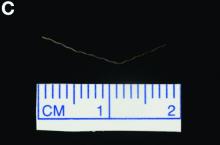

The CT image in Figure A shows an extraluminal foreign body in the left lower quadrant, surrounded by soft tissue thickening which represents reactive granulation tissue. She underwent surgical exploration, which revealed a single adhesion from a loop of the midjejunum to the neighboring mesentery (Figure B) that, when lysed, uncovered a small metal fragment consistent with a wire bristle from a grill-cleaning brush (Figure C). On further history, she reported frequent outdoor residential food grilling and admitted to using a wire grill cleaning brush. It is likely that she unintentionally ingested a metal bristle from a barbecue grill brush that was embedded in cooked food and penetrated through the small bowel wall, causing an adhesive inflammatory reaction and subsequent recurrent SBO.

Ingested foreign bodies are most frequently encountered in the pediatric population. Injury from inadvertent ingestion of wire grill cleaning brush bristles is being reported with increasing frequency in adults.2 Gastroenterologists should be aware of this type of foreign body injury to help prevent delay in diagnosis and ultimately treatment. This case highlights several additional important points. First, the evaluation of SBO must begin with a broad differential diagnosis, even in a patient with established CD. Second, the bristles are small and difficult to visualize on imaging. After resolution of acute obstruction, diagnostic imaging should be performed without positive oral contrast agent, which can obscure subtle mucosal findings or in this case, a diminutive extraluminal foreign body. Finally, greater public awareness should be raised that bristles might dislodge from wire grill brushes and embed in cooked food.3

References:

1. Hayanga AJ, Bass-Wilkins K, Bulkley GB. Current management of small-bowel obstruction. Adv Surg. 2005;39:1-33.

2. Harlor EJ, Lindemann TL, Kennedy TL. Outdoor grilling hazard: wire bristle esophageal foreign body - a report of six cases. Laryngoscope. 2012;122:2216-8.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Injuries from ingestion of wire bristles from grill-cleaning brush - Providence, Rhode Island, March 2011-June 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:490-2.

By Guilherme Piovezani Ramos, MD, Seth Sweetser, MD, and John B. Kisiel, MD

Recurrent SBO owing to contained perforation after accidental ingestion of a metal bristle of a barbecue grill brush

SBO may be caused by a variety of intrinsic or extrinsic lesions. Postoperative adhesions (60%) and malignant tumors (20%) are responsible for the majority of cases in the United States. CD accounts for approximately 5% of all SBOs.1 The unusual root cause of our patient's SBO was unintentional ingestion of a foreign body.

The CT image in Figure A shows an extraluminal foreign body in the left lower quadrant, surrounded by soft tissue thickening which represents reactive granulation tissue. She underwent surgical exploration, which revealed a single adhesion from a loop of the midjejunum to the neighboring mesentery (Figure B) that, when lysed, uncovered a small metal fragment consistent with a wire bristle from a grill-cleaning brush (Figure C). On further history, she reported frequent outdoor residential food grilling and admitted to using a wire grill cleaning brush. It is likely that she unintentionally ingested a metal bristle from a barbecue grill brush that was embedded in cooked food and penetrated through the small bowel wall, causing an adhesive inflammatory reaction and subsequent recurrent SBO.

Ingested foreign bodies are most frequently encountered in the pediatric population. Injury from inadvertent ingestion of wire grill cleaning brush bristles is being reported with increasing frequency in adults.2 Gastroenterologists should be aware of this type of foreign body injury to help prevent delay in diagnosis and ultimately treatment. This case highlights several additional important points. First, the evaluation of SBO must begin with a broad differential diagnosis, even in a patient with established CD. Second, the bristles are small and difficult to visualize on imaging. After resolution of acute obstruction, diagnostic imaging should be performed without positive oral contrast agent, which can obscure subtle mucosal findings or in this case, a diminutive extraluminal foreign body. Finally, greater public awareness should be raised that bristles might dislodge from wire grill brushes and embed in cooked food.3

References:

1. Hayanga AJ, Bass-Wilkins K, Bulkley GB. Current management of small-bowel obstruction. Adv Surg. 2005;39:1-33.

2. Harlor EJ, Lindemann TL, Kennedy TL. Outdoor grilling hazard: wire bristle esophageal foreign body - a report of six cases. Laryngoscope. 2012;122:2216-8.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Injuries from ingestion of wire bristles from grill-cleaning brush - Providence, Rhode Island, March 2011-June 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:490-2.

By Guilherme Piovezani Ramos, MD, Seth Sweetser, MD, and John B. Kisiel, MD

Recurrent SBO owing to contained perforation after accidental ingestion of a metal bristle of a barbecue grill brush

SBO may be caused by a variety of intrinsic or extrinsic lesions. Postoperative adhesions (60%) and malignant tumors (20%) are responsible for the majority of cases in the United States. CD accounts for approximately 5% of all SBOs.1 The unusual root cause of our patient's SBO was unintentional ingestion of a foreign body.

The CT image in Figure A shows an extraluminal foreign body in the left lower quadrant, surrounded by soft tissue thickening which represents reactive granulation tissue. She underwent surgical exploration, which revealed a single adhesion from a loop of the midjejunum to the neighboring mesentery (Figure B) that, when lysed, uncovered a small metal fragment consistent with a wire bristle from a grill-cleaning brush (Figure C). On further history, she reported frequent outdoor residential food grilling and admitted to using a wire grill cleaning brush. It is likely that she unintentionally ingested a metal bristle from a barbecue grill brush that was embedded in cooked food and penetrated through the small bowel wall, causing an adhesive inflammatory reaction and subsequent recurrent SBO.

Ingested foreign bodies are most frequently encountered in the pediatric population. Injury from inadvertent ingestion of wire grill cleaning brush bristles is being reported with increasing frequency in adults.2 Gastroenterologists should be aware of this type of foreign body injury to help prevent delay in diagnosis and ultimately treatment. This case highlights several additional important points. First, the evaluation of SBO must begin with a broad differential diagnosis, even in a patient with established CD. Second, the bristles are small and difficult to visualize on imaging. After resolution of acute obstruction, diagnostic imaging should be performed without positive oral contrast agent, which can obscure subtle mucosal findings or in this case, a diminutive extraluminal foreign body. Finally, greater public awareness should be raised that bristles might dislodge from wire grill brushes and embed in cooked food.3

References:

1. Hayanga AJ, Bass-Wilkins K, Bulkley GB. Current management of small-bowel obstruction. Adv Surg. 2005;39:1-33.

2. Harlor EJ, Lindemann TL, Kennedy TL. Outdoor grilling hazard: wire bristle esophageal foreign body - a report of six cases. Laryngoscope. 2012;122:2216-8.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Injuries from ingestion of wire bristles from grill-cleaning brush - Providence, Rhode Island, March 2011-June 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:490-2.