User login

Cecal carcinoma–associated paraneoplastic Sweet’s syndrome

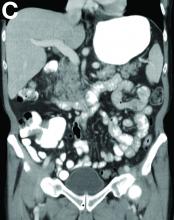

Based on the tomographic appearance of an “apple core”–like lesion in the right lower quadrant, the patient was referred for colonoscopy, which revealed a malignant-appearing cecal mass (Figure D), with biopsies confirming adenocarcinoma; despite these findings, no bowel-related symptoms were reported. The patient underwent laparoscopic right hemicolectomy, after which the skin lesions began to resolve, and corticosteroids were successfully tapered. The overall presentation was consistent with Sweet’s syndrome, with a paraneoplastic etiology being favored given the clinical scenario, including absence of alternative etiologies and dependence on corticosteroids for control of skin disease until resection of the underlying malignancy was performed.

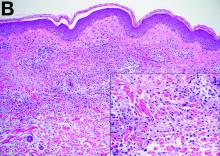

Sweet’s syndrome was first described in a case series of eight patients published in 1964 by the English dermatologist Dr. Robert Douglas Sweet.1,2 Sweet’s syndrome is characterized by fever, neutrophilia, and sterile erythematous plaques or nodules, which most commonly involve the upper extremities and face and respond to corticosteroid therapy. It may be malignancy associated, drug induced, autoimmune disease related, or idiopathic.2,3 The pathogenesis of Sweet’s syndrome is unclear, but T-lymphocyte, neutrophil chemotaxis, and cytokine (e.g., interleukin-6 and granulocyte colony–stimulating factor) abnormalities have been suggested.2 Diagnosis is based on the clinical presentation and context together with typical dermatopathologic findings, including a dense neutrophilic infiltrate. Skin lesions may be phasic, but persist typically until appropriate therapy (e.g., corticosteroids, chemotherapy) is administered or the offending drug removed. Malignancy-associated (i.e., paraneoplastic) Sweet’s syndrome accounts for approximately 20% of all cases; these primarily involve hematologic malignancies, most commonly leukemia, but adenocarcinomata have also been implicated.3 Recurrence of Sweet’s syndrome can occur and often heralds relapse of the underlying disease.

References

1. Sweet RD. An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1964;76:349-56.

2. Von den Driesch P. Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:535-56.

3. Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome–a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34.

Cecal carcinoma–associated paraneoplastic Sweet’s syndrome

Based on the tomographic appearance of an “apple core”–like lesion in the right lower quadrant, the patient was referred for colonoscopy, which revealed a malignant-appearing cecal mass (Figure D), with biopsies confirming adenocarcinoma; despite these findings, no bowel-related symptoms were reported. The patient underwent laparoscopic right hemicolectomy, after which the skin lesions began to resolve, and corticosteroids were successfully tapered. The overall presentation was consistent with Sweet’s syndrome, with a paraneoplastic etiology being favored given the clinical scenario, including absence of alternative etiologies and dependence on corticosteroids for control of skin disease until resection of the underlying malignancy was performed.

Sweet’s syndrome was first described in a case series of eight patients published in 1964 by the English dermatologist Dr. Robert Douglas Sweet.1,2 Sweet’s syndrome is characterized by fever, neutrophilia, and sterile erythematous plaques or nodules, which most commonly involve the upper extremities and face and respond to corticosteroid therapy. It may be malignancy associated, drug induced, autoimmune disease related, or idiopathic.2,3 The pathogenesis of Sweet’s syndrome is unclear, but T-lymphocyte, neutrophil chemotaxis, and cytokine (e.g., interleukin-6 and granulocyte colony–stimulating factor) abnormalities have been suggested.2 Diagnosis is based on the clinical presentation and context together with typical dermatopathologic findings, including a dense neutrophilic infiltrate. Skin lesions may be phasic, but persist typically until appropriate therapy (e.g., corticosteroids, chemotherapy) is administered or the offending drug removed. Malignancy-associated (i.e., paraneoplastic) Sweet’s syndrome accounts for approximately 20% of all cases; these primarily involve hematologic malignancies, most commonly leukemia, but adenocarcinomata have also been implicated.3 Recurrence of Sweet’s syndrome can occur and often heralds relapse of the underlying disease.

References

1. Sweet RD. An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1964;76:349-56.

2. Von den Driesch P. Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:535-56.

3. Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome–a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34.

Cecal carcinoma–associated paraneoplastic Sweet’s syndrome

Based on the tomographic appearance of an “apple core”–like lesion in the right lower quadrant, the patient was referred for colonoscopy, which revealed a malignant-appearing cecal mass (Figure D), with biopsies confirming adenocarcinoma; despite these findings, no bowel-related symptoms were reported. The patient underwent laparoscopic right hemicolectomy, after which the skin lesions began to resolve, and corticosteroids were successfully tapered. The overall presentation was consistent with Sweet’s syndrome, with a paraneoplastic etiology being favored given the clinical scenario, including absence of alternative etiologies and dependence on corticosteroids for control of skin disease until resection of the underlying malignancy was performed.

Sweet’s syndrome was first described in a case series of eight patients published in 1964 by the English dermatologist Dr. Robert Douglas Sweet.1,2 Sweet’s syndrome is characterized by fever, neutrophilia, and sterile erythematous plaques or nodules, which most commonly involve the upper extremities and face and respond to corticosteroid therapy. It may be malignancy associated, drug induced, autoimmune disease related, or idiopathic.2,3 The pathogenesis of Sweet’s syndrome is unclear, but T-lymphocyte, neutrophil chemotaxis, and cytokine (e.g., interleukin-6 and granulocyte colony–stimulating factor) abnormalities have been suggested.2 Diagnosis is based on the clinical presentation and context together with typical dermatopathologic findings, including a dense neutrophilic infiltrate. Skin lesions may be phasic, but persist typically until appropriate therapy (e.g., corticosteroids, chemotherapy) is administered or the offending drug removed. Malignancy-associated (i.e., paraneoplastic) Sweet’s syndrome accounts for approximately 20% of all cases; these primarily involve hematologic malignancies, most commonly leukemia, but adenocarcinomata have also been implicated.3 Recurrence of Sweet’s syndrome can occur and often heralds relapse of the underlying disease.

References

1. Sweet RD. An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1964;76:349-56.

2. Von den Driesch P. Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:535-56.

3. Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome–a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34.