User login

Improving Healthcare Value: COVID-19 Emergency Regulatory Relief and Implications for Post-Acute Skilled Nursing Facility Care

Medicare beneficiary who requires skilled care in a nursing home? Better be admitted for at least 3 days in the hospital first if you want the nursing home paid for. Govt doesn’t always make sense. We’re listening to feedback.

—Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Administrator Seema Verma, @SeemaCMS, August 4, 2019, via Twitter.1

On March 13, 2020, the president of the United States declared a national health emergency, granting the secretary of the United States Department of Health & Human Services authority to grant waivers intended to ease certain Medicare and Medicaid program requirements.2 Broad waiver categories include those that may be requested by an individual institution, as well as “COVID-19 Emergency Declaration Blanket Waivers,” which automatically apply across all facilities and providers. As stated by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), waivers are intended to create “regulatory flexibilities to help healthcare providers contain the spread of 2019 Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19).” These provisions are retroactive to March 1, 2020, expire at the end of the “emergency period or 60 days from the date the waiver . . . is first published” and can be extended by the secretary.2

The issued blanket waivers remove administrative requirements in a wide range of care settings including home health, hospice, hospitals, and skilled nursing facilities (SNF), among others. The waiving of many of these administrative requirements are welcomed by providers and administrators alike in this time of national crisis. For example, relaxation of verbal order signage requirements and expanded coverage of telehealth will, almost certainly, improve accessibility, efficiency, and requisite coordination and care across settings. Emergence of these new “COVID-19” waivers also present rare and valuable opportunities to examine care improvement in areas long believed to need permanent regulatory change. Perhaps the most important of these long over-due changes is the current CMS process for determining Part A eligibility for post-acute skilled nursing facility coverage for traditional Medicare beneficiaries following an inpatient hospitalization. Under COVID-19, CMS has now granted a waiver that “authorizes the Secretary to provide for Skilled Nursing Facilities (SNF) coverage in the absence of a qualifying [three consecutive inpatient midnight] hospital stay. . . .”2 Although demand for SNF placement may shift during the pandemic, hospitals facing capacity issues will more easily be able to discharge Medicare beneficiaries ready for post-acute care.

POST-ACUTE SKILLED NURSING FACILITY COVERAGE

When Medicare was established in 1965, approximately half of Americans over age 65 did not have health insurance, and older adults were the most likely demographic to be living in poverty.3 Originally called “Hospital Insurance” or “Medicare Part A,” these “Inpatient Hospital Services” are described in Social Security statute as “items and services furnished to an inpatient of a hospital” including room and board, nursing services, pharmaceuticals, and medical and surgical services delivered in the hospital.4 In 1967, Medicare beneficiaries staying three consecutive inpatient hospital midnights were also afforded post-acute SNF coverage for up to 100 days. As expected, hospital use increased as seniors had coverage for hospital care and were also, in many cases, able to access higher quality post-hospital care.5

Over the past 50 years, two important changes have shifted Medicare beneficiary SNF coverage. First, due to efficiencies and changes in care delivery, average length of hospital stay for Americans over age 65 has shrunk from 14 days in 1965 to approximately 5 days currently.5,6 Now, fewer beneficiaries spend the necessary three or more nights in the hospital to qualify for post-acute SNF coverage. Second, and most importantly, CMS created “observation status” in the 1980s, which allowed for patients to be observed as “outpatients” in a hospital instead of as inpatients. Notably, these observation nights fall under outpatient status (Part B), and therefore do not count toward the statutory SNF coverage requirement of three inpatient midnights.

According to CMS, observation should be used so that a “decision can be made regarding whether patients will require further treatment as hospital inpatients or if they are able to be discharged from the hospital. . . . In the majority of cases, the decision can be made in less than 48 hours, usually in less than 24 hours.”7 At the time of its development, this concept fit the growing use of Emergency Department observation units, in which patients presented for an acute issue but could usually discharge home in the stated time frame.

OBSERVATION CARE

In reality, outpatient (observation) status is not synonymous with observation units. Because observation is a billing determination, not a specific type of clinical care, observation care may be delivered anywhere in a hospital—including an observation unit, a hospital ward, or even an intensive care unit (ICU). While all hospitals may deliver observation care, only about one-third of hospitals have observation units, and even hospitals with observation units deliver observation care outside of these units. Traditional Medicare beneficiaries who stay three or more nights in the hospital but cannot meet the three inpatient midnight requirement to access their SNF coverage benefits because of outpatient (observation) nights are often left vulnerable and confused, saddling them with an average of $10,503 for each uncovered SNF stay.8 As emergent evidence demonstrates striking racial, geographic, and socioeconomic-based health disparities in COVID-19, renewal of the “three-midnight rule” could have disproportionate and long-lasting ramifications for these populations in particular.9

Hospital observation stays (or observation nights) can look identical to inpatient hospital stays, as defined by the Social Security statute4; yet never count toward the three-inpatient-midnight tally. In 2014, the Office of Inspector General (OIG) found there were 633,148 hospital stays that lasted three midnights or longer but did not contain three consecutive inpatient midnights, which resulted in nonqualifying stays for purposes of SNF coverage, if that coverage was needed.10 A more recent OIG report found that Medicare was paying erroneously for some SNF stays because even CMS could not distinguish between three midnights that were all inpatient or a combination of inpatient and observation.11 Additionally, because care provided is often indistinguishable, status changes between outpatient and inpatient are common; in 2014, 40% of Medicare observation stays occurring within 30 days of an inpatient stay changed to inpatient over the course of a single hospitalization.12 Now, in the time of COVID-19, this untenable decades-long problem has the potential to be definitively addressed by a permanent removal of the three midnight requirement altogether.

PROGRESS TOWARD REFORM

Several recent signals suggest that change is supported by a diverse group of stakeholders. In their 2019 Top 25 Unimplemented Recommendations, the OIG acknowledged the similarity in observation and inpatient care, recommending that “CMS . . . analyze the potential impacts of counting time spent as an outpatient toward the 3-night requirement for skilled nursing facility (SNF) services so that beneficiaries receiving similar hospital care have similar access to these services.”13 The “Improving Access to Medicare Coverage Act of 2019,” reintroduced in the 116th Congress, would count all midnights spent in the hospital, whether those nights are inpatient or observation, toward the three midnight requirement.14 This bill has bipartisan, bicameral support, which demonstrates unified legislative interest across the political spectrum. More recently in March 2020, a federal judge in the class action lawsuit Alexander v Azar determined that Medicare beneficiaries had the right to appeal to Medicare if a physician placed a patient in inpatient status and this decision was overturned administratively by a hospital, resulting in loss of a beneficiary’s SNF coverage.15 Although now under appeal, this judicial decision signals the importance of beneficiary rights to appeal directly to CMS.

Given the mounting support for reform, it is probable that cost concerns and allocation of resources to the Part A vs Part B “buckets” remain the only barrier to permanently reforming the three-midnight inpatient stay policy. Pilot programs testing Medicare SNF waivers more than 30 years ago suggested increased cost and SNF usage.16 However, more contemporary experience from Medicare Advantage programs suggest just the opposite. Grebla et al showed there was no increased SNF use nor SNF length of stay for beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage plans that waived the three inpatient midnight requirement.17

Arguably, the current COVID-19 emergency blanket SNF waiver is not a perfect test of short- or long-term Medicare costs. First, factors such as reduced hospital elective surgeries that may typically drive post-acute SNF admissions, as well as potentially reduced SNF utilization caused by fear of COVID-19 outbreaks, may temporarily lower SNF use and associated Medicare expenditures. The existing waiver of statute is also financially constrained, stipulating that “this action does not increase overall program payments. . . .”2 Longer term, innovations in care delivery prompted by accelerated telehealth reforms may shift more post-acute care from SNFs to the home setting, changing patterns of SNF utilization altogether. Despite these limitations, this regulatory relief will still provide valuable utilization and cost information on SNF use under a system absent the three-midnight requirement.

CONCLUSION

Rarely, if ever, does a national healthcare system experience such a rapid and marked change as that seen with the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the tragic emergency circumstances prompting CMS’s blanket waivers, it provides CMS and stakeholders with a rare opportunity to evaluate potential improvements revealed by each individual aspect of COVID-19 regulatory relief. CMS has in the past argued the three-midnight SNF requirement is a statutory issue and thus not within their control, yet they have used their regulatory authority to waive this policy to facilitate efficient care in a national health crisis. This is a change that many believe is long overdue, and one that should be maintained even after COVID-19 abates. “Govt doesn’t always make sense,” as Administrator Verma wrote,1 should be a cry for government to make better sense of existing legislation and regulation. Reform of the three-midnight inpatient rule is the right place to start.

1. @SeemaCMS. #Medicare beneficiary who requires skilled care in a nursing home? Better be admitted for at least 3 days in the hospital first if you want the nursing home paid for. [Flushed face emoji] Govt doesn’t always make sense. We’re listening to feedback. #RedTapeTales #TheBoldAndTheBureaucratic. August 4, 2019. Accessed April 17, 2020. https://twitter.com/SeemaCMS/status/1158029830056828928

2. COVID-19 Emergency Declaration Blanket Waivers for Health Care Providers. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2020. Accessed April 17, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/summary-covid-19-emergency-declaration-waivers.pdf

3. Medicare & Medicaid Milestones, 1937 to 2015. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2015. Accessed April 17, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/About-CMS/Agency-Information/History/Downloads/Medicare-and-Medicaid-Milestones-1937-2015.pdf

4. Social Security Laws, 42 USC 1395x §1861 (1965). Accessed April 17, 2020. https://www.ssa.gov/OP_Home/ssact/title18/1861.htm

5. Loewenstein R. Early effects of Medicare on the health care of the aged. Social Security Bulletin. April 1971; pp 3-20, 42. Accessed April 14, 2020. https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v34n4/v34n4p3.pdf

6. Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A. Overview of Hospital Stays in the United States, 2012. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2014. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb180-Hospitalizations-United-States-2012.pdf

7. Medicare Benefits Policy Manual, Internet-Only Manuals. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Pub. 100-02, Chapter 6, § 20.6. Updated April 5, 2012. Accessed April 17, 2020. http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/Internet-Only-Manuals-IOMs.html

8. Wright S. Hospitals’ Use of Observation Stays and Short Inpatient Stays for Medicare Beneficiaries. Office of the Inspector General, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2014. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-12-00040.asp

9. Yancy CW. COVID-19 and African Americans. JAMA. Published online April 15, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6548

10. Levinson DR. Vulnerabilities Remain Under Medicare’s 2-Midnight Hospital Policy. Office of the Inspector General, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2016. Accessed April 18, 2020. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-15-00020.pdf

11. Levinson DR. CMS Improperly Paid Millions of Dollars for Skilled Nursing Facility Services When the Medicare 3-Day Inpatient Hospital Stay Requirement Was Not Met. Office of the Inspector General, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2019. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://www.oig.hhs.gov/oas/reports/region5/51600043.pdf

12. Sheehy A, Shi F, Kind A. Identifying observation stays in Medicare data: policy implications of a definition. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(2):96-100. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3038

13. Solutions to Reduce Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in HHS Programs: OIG’s Top Recommendations. Office of the Inspector General, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2019. Accessed April 18, 2020. https://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/compendium/files/compendium2019.pdf

14. Improving Access to Medicare Coverage Act of 2019, HR 1682, 116th Congress (2019). Accessed April 16, 2020. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/1682

15. Alexander v Azar, 396 F Supp 3d 242 (D CT 2019). Accessed May 26, 2020. https://casetext.com/case/alexander-v-azar-1?

16. Lipsitz L. The 3-night hospital stay and Medicare coverage for skilled nursing care. JAMA. 2013;310(14):1441-1442. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.254845

17. Grebla R, Keohane L, Lee Y, Lipsitz L, Rahman M, Trevedi A. Waiving the three-day rule: admissions and length-of-stay at hospitals and skilled nursing facilities did not increase. Health Affairs (Millwood). 2015;34(8):1324-1330. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0054

Medicare beneficiary who requires skilled care in a nursing home? Better be admitted for at least 3 days in the hospital first if you want the nursing home paid for. Govt doesn’t always make sense. We’re listening to feedback.

—Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Administrator Seema Verma, @SeemaCMS, August 4, 2019, via Twitter.1

On March 13, 2020, the president of the United States declared a national health emergency, granting the secretary of the United States Department of Health & Human Services authority to grant waivers intended to ease certain Medicare and Medicaid program requirements.2 Broad waiver categories include those that may be requested by an individual institution, as well as “COVID-19 Emergency Declaration Blanket Waivers,” which automatically apply across all facilities and providers. As stated by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), waivers are intended to create “regulatory flexibilities to help healthcare providers contain the spread of 2019 Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19).” These provisions are retroactive to March 1, 2020, expire at the end of the “emergency period or 60 days from the date the waiver . . . is first published” and can be extended by the secretary.2

The issued blanket waivers remove administrative requirements in a wide range of care settings including home health, hospice, hospitals, and skilled nursing facilities (SNF), among others. The waiving of many of these administrative requirements are welcomed by providers and administrators alike in this time of national crisis. For example, relaxation of verbal order signage requirements and expanded coverage of telehealth will, almost certainly, improve accessibility, efficiency, and requisite coordination and care across settings. Emergence of these new “COVID-19” waivers also present rare and valuable opportunities to examine care improvement in areas long believed to need permanent regulatory change. Perhaps the most important of these long over-due changes is the current CMS process for determining Part A eligibility for post-acute skilled nursing facility coverage for traditional Medicare beneficiaries following an inpatient hospitalization. Under COVID-19, CMS has now granted a waiver that “authorizes the Secretary to provide for Skilled Nursing Facilities (SNF) coverage in the absence of a qualifying [three consecutive inpatient midnight] hospital stay. . . .”2 Although demand for SNF placement may shift during the pandemic, hospitals facing capacity issues will more easily be able to discharge Medicare beneficiaries ready for post-acute care.

POST-ACUTE SKILLED NURSING FACILITY COVERAGE

When Medicare was established in 1965, approximately half of Americans over age 65 did not have health insurance, and older adults were the most likely demographic to be living in poverty.3 Originally called “Hospital Insurance” or “Medicare Part A,” these “Inpatient Hospital Services” are described in Social Security statute as “items and services furnished to an inpatient of a hospital” including room and board, nursing services, pharmaceuticals, and medical and surgical services delivered in the hospital.4 In 1967, Medicare beneficiaries staying three consecutive inpatient hospital midnights were also afforded post-acute SNF coverage for up to 100 days. As expected, hospital use increased as seniors had coverage for hospital care and were also, in many cases, able to access higher quality post-hospital care.5

Over the past 50 years, two important changes have shifted Medicare beneficiary SNF coverage. First, due to efficiencies and changes in care delivery, average length of hospital stay for Americans over age 65 has shrunk from 14 days in 1965 to approximately 5 days currently.5,6 Now, fewer beneficiaries spend the necessary three or more nights in the hospital to qualify for post-acute SNF coverage. Second, and most importantly, CMS created “observation status” in the 1980s, which allowed for patients to be observed as “outpatients” in a hospital instead of as inpatients. Notably, these observation nights fall under outpatient status (Part B), and therefore do not count toward the statutory SNF coverage requirement of three inpatient midnights.

According to CMS, observation should be used so that a “decision can be made regarding whether patients will require further treatment as hospital inpatients or if they are able to be discharged from the hospital. . . . In the majority of cases, the decision can be made in less than 48 hours, usually in less than 24 hours.”7 At the time of its development, this concept fit the growing use of Emergency Department observation units, in which patients presented for an acute issue but could usually discharge home in the stated time frame.

OBSERVATION CARE

In reality, outpatient (observation) status is not synonymous with observation units. Because observation is a billing determination, not a specific type of clinical care, observation care may be delivered anywhere in a hospital—including an observation unit, a hospital ward, or even an intensive care unit (ICU). While all hospitals may deliver observation care, only about one-third of hospitals have observation units, and even hospitals with observation units deliver observation care outside of these units. Traditional Medicare beneficiaries who stay three or more nights in the hospital but cannot meet the three inpatient midnight requirement to access their SNF coverage benefits because of outpatient (observation) nights are often left vulnerable and confused, saddling them with an average of $10,503 for each uncovered SNF stay.8 As emergent evidence demonstrates striking racial, geographic, and socioeconomic-based health disparities in COVID-19, renewal of the “three-midnight rule” could have disproportionate and long-lasting ramifications for these populations in particular.9

Hospital observation stays (or observation nights) can look identical to inpatient hospital stays, as defined by the Social Security statute4; yet never count toward the three-inpatient-midnight tally. In 2014, the Office of Inspector General (OIG) found there were 633,148 hospital stays that lasted three midnights or longer but did not contain three consecutive inpatient midnights, which resulted in nonqualifying stays for purposes of SNF coverage, if that coverage was needed.10 A more recent OIG report found that Medicare was paying erroneously for some SNF stays because even CMS could not distinguish between three midnights that were all inpatient or a combination of inpatient and observation.11 Additionally, because care provided is often indistinguishable, status changes between outpatient and inpatient are common; in 2014, 40% of Medicare observation stays occurring within 30 days of an inpatient stay changed to inpatient over the course of a single hospitalization.12 Now, in the time of COVID-19, this untenable decades-long problem has the potential to be definitively addressed by a permanent removal of the three midnight requirement altogether.

PROGRESS TOWARD REFORM

Several recent signals suggest that change is supported by a diverse group of stakeholders. In their 2019 Top 25 Unimplemented Recommendations, the OIG acknowledged the similarity in observation and inpatient care, recommending that “CMS . . . analyze the potential impacts of counting time spent as an outpatient toward the 3-night requirement for skilled nursing facility (SNF) services so that beneficiaries receiving similar hospital care have similar access to these services.”13 The “Improving Access to Medicare Coverage Act of 2019,” reintroduced in the 116th Congress, would count all midnights spent in the hospital, whether those nights are inpatient or observation, toward the three midnight requirement.14 This bill has bipartisan, bicameral support, which demonstrates unified legislative interest across the political spectrum. More recently in March 2020, a federal judge in the class action lawsuit Alexander v Azar determined that Medicare beneficiaries had the right to appeal to Medicare if a physician placed a patient in inpatient status and this decision was overturned administratively by a hospital, resulting in loss of a beneficiary’s SNF coverage.15 Although now under appeal, this judicial decision signals the importance of beneficiary rights to appeal directly to CMS.

Given the mounting support for reform, it is probable that cost concerns and allocation of resources to the Part A vs Part B “buckets” remain the only barrier to permanently reforming the three-midnight inpatient stay policy. Pilot programs testing Medicare SNF waivers more than 30 years ago suggested increased cost and SNF usage.16 However, more contemporary experience from Medicare Advantage programs suggest just the opposite. Grebla et al showed there was no increased SNF use nor SNF length of stay for beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage plans that waived the three inpatient midnight requirement.17

Arguably, the current COVID-19 emergency blanket SNF waiver is not a perfect test of short- or long-term Medicare costs. First, factors such as reduced hospital elective surgeries that may typically drive post-acute SNF admissions, as well as potentially reduced SNF utilization caused by fear of COVID-19 outbreaks, may temporarily lower SNF use and associated Medicare expenditures. The existing waiver of statute is also financially constrained, stipulating that “this action does not increase overall program payments. . . .”2 Longer term, innovations in care delivery prompted by accelerated telehealth reforms may shift more post-acute care from SNFs to the home setting, changing patterns of SNF utilization altogether. Despite these limitations, this regulatory relief will still provide valuable utilization and cost information on SNF use under a system absent the three-midnight requirement.

CONCLUSION

Rarely, if ever, does a national healthcare system experience such a rapid and marked change as that seen with the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the tragic emergency circumstances prompting CMS’s blanket waivers, it provides CMS and stakeholders with a rare opportunity to evaluate potential improvements revealed by each individual aspect of COVID-19 regulatory relief. CMS has in the past argued the three-midnight SNF requirement is a statutory issue and thus not within their control, yet they have used their regulatory authority to waive this policy to facilitate efficient care in a national health crisis. This is a change that many believe is long overdue, and one that should be maintained even after COVID-19 abates. “Govt doesn’t always make sense,” as Administrator Verma wrote,1 should be a cry for government to make better sense of existing legislation and regulation. Reform of the three-midnight inpatient rule is the right place to start.

Medicare beneficiary who requires skilled care in a nursing home? Better be admitted for at least 3 days in the hospital first if you want the nursing home paid for. Govt doesn’t always make sense. We’re listening to feedback.

—Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Administrator Seema Verma, @SeemaCMS, August 4, 2019, via Twitter.1

On March 13, 2020, the president of the United States declared a national health emergency, granting the secretary of the United States Department of Health & Human Services authority to grant waivers intended to ease certain Medicare and Medicaid program requirements.2 Broad waiver categories include those that may be requested by an individual institution, as well as “COVID-19 Emergency Declaration Blanket Waivers,” which automatically apply across all facilities and providers. As stated by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), waivers are intended to create “regulatory flexibilities to help healthcare providers contain the spread of 2019 Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19).” These provisions are retroactive to March 1, 2020, expire at the end of the “emergency period or 60 days from the date the waiver . . . is first published” and can be extended by the secretary.2

The issued blanket waivers remove administrative requirements in a wide range of care settings including home health, hospice, hospitals, and skilled nursing facilities (SNF), among others. The waiving of many of these administrative requirements are welcomed by providers and administrators alike in this time of national crisis. For example, relaxation of verbal order signage requirements and expanded coverage of telehealth will, almost certainly, improve accessibility, efficiency, and requisite coordination and care across settings. Emergence of these new “COVID-19” waivers also present rare and valuable opportunities to examine care improvement in areas long believed to need permanent regulatory change. Perhaps the most important of these long over-due changes is the current CMS process for determining Part A eligibility for post-acute skilled nursing facility coverage for traditional Medicare beneficiaries following an inpatient hospitalization. Under COVID-19, CMS has now granted a waiver that “authorizes the Secretary to provide for Skilled Nursing Facilities (SNF) coverage in the absence of a qualifying [three consecutive inpatient midnight] hospital stay. . . .”2 Although demand for SNF placement may shift during the pandemic, hospitals facing capacity issues will more easily be able to discharge Medicare beneficiaries ready for post-acute care.

POST-ACUTE SKILLED NURSING FACILITY COVERAGE

When Medicare was established in 1965, approximately half of Americans over age 65 did not have health insurance, and older adults were the most likely demographic to be living in poverty.3 Originally called “Hospital Insurance” or “Medicare Part A,” these “Inpatient Hospital Services” are described in Social Security statute as “items and services furnished to an inpatient of a hospital” including room and board, nursing services, pharmaceuticals, and medical and surgical services delivered in the hospital.4 In 1967, Medicare beneficiaries staying three consecutive inpatient hospital midnights were also afforded post-acute SNF coverage for up to 100 days. As expected, hospital use increased as seniors had coverage for hospital care and were also, in many cases, able to access higher quality post-hospital care.5

Over the past 50 years, two important changes have shifted Medicare beneficiary SNF coverage. First, due to efficiencies and changes in care delivery, average length of hospital stay for Americans over age 65 has shrunk from 14 days in 1965 to approximately 5 days currently.5,6 Now, fewer beneficiaries spend the necessary three or more nights in the hospital to qualify for post-acute SNF coverage. Second, and most importantly, CMS created “observation status” in the 1980s, which allowed for patients to be observed as “outpatients” in a hospital instead of as inpatients. Notably, these observation nights fall under outpatient status (Part B), and therefore do not count toward the statutory SNF coverage requirement of three inpatient midnights.

According to CMS, observation should be used so that a “decision can be made regarding whether patients will require further treatment as hospital inpatients or if they are able to be discharged from the hospital. . . . In the majority of cases, the decision can be made in less than 48 hours, usually in less than 24 hours.”7 At the time of its development, this concept fit the growing use of Emergency Department observation units, in which patients presented for an acute issue but could usually discharge home in the stated time frame.

OBSERVATION CARE

In reality, outpatient (observation) status is not synonymous with observation units. Because observation is a billing determination, not a specific type of clinical care, observation care may be delivered anywhere in a hospital—including an observation unit, a hospital ward, or even an intensive care unit (ICU). While all hospitals may deliver observation care, only about one-third of hospitals have observation units, and even hospitals with observation units deliver observation care outside of these units. Traditional Medicare beneficiaries who stay three or more nights in the hospital but cannot meet the three inpatient midnight requirement to access their SNF coverage benefits because of outpatient (observation) nights are often left vulnerable and confused, saddling them with an average of $10,503 for each uncovered SNF stay.8 As emergent evidence demonstrates striking racial, geographic, and socioeconomic-based health disparities in COVID-19, renewal of the “three-midnight rule” could have disproportionate and long-lasting ramifications for these populations in particular.9

Hospital observation stays (or observation nights) can look identical to inpatient hospital stays, as defined by the Social Security statute4; yet never count toward the three-inpatient-midnight tally. In 2014, the Office of Inspector General (OIG) found there were 633,148 hospital stays that lasted three midnights or longer but did not contain three consecutive inpatient midnights, which resulted in nonqualifying stays for purposes of SNF coverage, if that coverage was needed.10 A more recent OIG report found that Medicare was paying erroneously for some SNF stays because even CMS could not distinguish between three midnights that were all inpatient or a combination of inpatient and observation.11 Additionally, because care provided is often indistinguishable, status changes between outpatient and inpatient are common; in 2014, 40% of Medicare observation stays occurring within 30 days of an inpatient stay changed to inpatient over the course of a single hospitalization.12 Now, in the time of COVID-19, this untenable decades-long problem has the potential to be definitively addressed by a permanent removal of the three midnight requirement altogether.

PROGRESS TOWARD REFORM

Several recent signals suggest that change is supported by a diverse group of stakeholders. In their 2019 Top 25 Unimplemented Recommendations, the OIG acknowledged the similarity in observation and inpatient care, recommending that “CMS . . . analyze the potential impacts of counting time spent as an outpatient toward the 3-night requirement for skilled nursing facility (SNF) services so that beneficiaries receiving similar hospital care have similar access to these services.”13 The “Improving Access to Medicare Coverage Act of 2019,” reintroduced in the 116th Congress, would count all midnights spent in the hospital, whether those nights are inpatient or observation, toward the three midnight requirement.14 This bill has bipartisan, bicameral support, which demonstrates unified legislative interest across the political spectrum. More recently in March 2020, a federal judge in the class action lawsuit Alexander v Azar determined that Medicare beneficiaries had the right to appeal to Medicare if a physician placed a patient in inpatient status and this decision was overturned administratively by a hospital, resulting in loss of a beneficiary’s SNF coverage.15 Although now under appeal, this judicial decision signals the importance of beneficiary rights to appeal directly to CMS.

Given the mounting support for reform, it is probable that cost concerns and allocation of resources to the Part A vs Part B “buckets” remain the only barrier to permanently reforming the three-midnight inpatient stay policy. Pilot programs testing Medicare SNF waivers more than 30 years ago suggested increased cost and SNF usage.16 However, more contemporary experience from Medicare Advantage programs suggest just the opposite. Grebla et al showed there was no increased SNF use nor SNF length of stay for beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage plans that waived the three inpatient midnight requirement.17

Arguably, the current COVID-19 emergency blanket SNF waiver is not a perfect test of short- or long-term Medicare costs. First, factors such as reduced hospital elective surgeries that may typically drive post-acute SNF admissions, as well as potentially reduced SNF utilization caused by fear of COVID-19 outbreaks, may temporarily lower SNF use and associated Medicare expenditures. The existing waiver of statute is also financially constrained, stipulating that “this action does not increase overall program payments. . . .”2 Longer term, innovations in care delivery prompted by accelerated telehealth reforms may shift more post-acute care from SNFs to the home setting, changing patterns of SNF utilization altogether. Despite these limitations, this regulatory relief will still provide valuable utilization and cost information on SNF use under a system absent the three-midnight requirement.

CONCLUSION

Rarely, if ever, does a national healthcare system experience such a rapid and marked change as that seen with the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the tragic emergency circumstances prompting CMS’s blanket waivers, it provides CMS and stakeholders with a rare opportunity to evaluate potential improvements revealed by each individual aspect of COVID-19 regulatory relief. CMS has in the past argued the three-midnight SNF requirement is a statutory issue and thus not within their control, yet they have used their regulatory authority to waive this policy to facilitate efficient care in a national health crisis. This is a change that many believe is long overdue, and one that should be maintained even after COVID-19 abates. “Govt doesn’t always make sense,” as Administrator Verma wrote,1 should be a cry for government to make better sense of existing legislation and regulation. Reform of the three-midnight inpatient rule is the right place to start.

1. @SeemaCMS. #Medicare beneficiary who requires skilled care in a nursing home? Better be admitted for at least 3 days in the hospital first if you want the nursing home paid for. [Flushed face emoji] Govt doesn’t always make sense. We’re listening to feedback. #RedTapeTales #TheBoldAndTheBureaucratic. August 4, 2019. Accessed April 17, 2020. https://twitter.com/SeemaCMS/status/1158029830056828928

2. COVID-19 Emergency Declaration Blanket Waivers for Health Care Providers. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2020. Accessed April 17, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/summary-covid-19-emergency-declaration-waivers.pdf

3. Medicare & Medicaid Milestones, 1937 to 2015. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2015. Accessed April 17, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/About-CMS/Agency-Information/History/Downloads/Medicare-and-Medicaid-Milestones-1937-2015.pdf

4. Social Security Laws, 42 USC 1395x §1861 (1965). Accessed April 17, 2020. https://www.ssa.gov/OP_Home/ssact/title18/1861.htm

5. Loewenstein R. Early effects of Medicare on the health care of the aged. Social Security Bulletin. April 1971; pp 3-20, 42. Accessed April 14, 2020. https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v34n4/v34n4p3.pdf

6. Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A. Overview of Hospital Stays in the United States, 2012. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2014. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb180-Hospitalizations-United-States-2012.pdf

7. Medicare Benefits Policy Manual, Internet-Only Manuals. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Pub. 100-02, Chapter 6, § 20.6. Updated April 5, 2012. Accessed April 17, 2020. http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/Internet-Only-Manuals-IOMs.html

8. Wright S. Hospitals’ Use of Observation Stays and Short Inpatient Stays for Medicare Beneficiaries. Office of the Inspector General, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2014. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-12-00040.asp

9. Yancy CW. COVID-19 and African Americans. JAMA. Published online April 15, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6548

10. Levinson DR. Vulnerabilities Remain Under Medicare’s 2-Midnight Hospital Policy. Office of the Inspector General, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2016. Accessed April 18, 2020. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-15-00020.pdf

11. Levinson DR. CMS Improperly Paid Millions of Dollars for Skilled Nursing Facility Services When the Medicare 3-Day Inpatient Hospital Stay Requirement Was Not Met. Office of the Inspector General, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2019. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://www.oig.hhs.gov/oas/reports/region5/51600043.pdf

12. Sheehy A, Shi F, Kind A. Identifying observation stays in Medicare data: policy implications of a definition. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(2):96-100. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3038

13. Solutions to Reduce Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in HHS Programs: OIG’s Top Recommendations. Office of the Inspector General, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2019. Accessed April 18, 2020. https://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/compendium/files/compendium2019.pdf

14. Improving Access to Medicare Coverage Act of 2019, HR 1682, 116th Congress (2019). Accessed April 16, 2020. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/1682

15. Alexander v Azar, 396 F Supp 3d 242 (D CT 2019). Accessed May 26, 2020. https://casetext.com/case/alexander-v-azar-1?

16. Lipsitz L. The 3-night hospital stay and Medicare coverage for skilled nursing care. JAMA. 2013;310(14):1441-1442. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.254845

17. Grebla R, Keohane L, Lee Y, Lipsitz L, Rahman M, Trevedi A. Waiving the three-day rule: admissions and length-of-stay at hospitals and skilled nursing facilities did not increase. Health Affairs (Millwood). 2015;34(8):1324-1330. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0054

1. @SeemaCMS. #Medicare beneficiary who requires skilled care in a nursing home? Better be admitted for at least 3 days in the hospital first if you want the nursing home paid for. [Flushed face emoji] Govt doesn’t always make sense. We’re listening to feedback. #RedTapeTales #TheBoldAndTheBureaucratic. August 4, 2019. Accessed April 17, 2020. https://twitter.com/SeemaCMS/status/1158029830056828928

2. COVID-19 Emergency Declaration Blanket Waivers for Health Care Providers. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2020. Accessed April 17, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/summary-covid-19-emergency-declaration-waivers.pdf

3. Medicare & Medicaid Milestones, 1937 to 2015. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2015. Accessed April 17, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/About-CMS/Agency-Information/History/Downloads/Medicare-and-Medicaid-Milestones-1937-2015.pdf

4. Social Security Laws, 42 USC 1395x §1861 (1965). Accessed April 17, 2020. https://www.ssa.gov/OP_Home/ssact/title18/1861.htm

5. Loewenstein R. Early effects of Medicare on the health care of the aged. Social Security Bulletin. April 1971; pp 3-20, 42. Accessed April 14, 2020. https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v34n4/v34n4p3.pdf

6. Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A. Overview of Hospital Stays in the United States, 2012. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2014. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb180-Hospitalizations-United-States-2012.pdf

7. Medicare Benefits Policy Manual, Internet-Only Manuals. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Pub. 100-02, Chapter 6, § 20.6. Updated April 5, 2012. Accessed April 17, 2020. http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/Internet-Only-Manuals-IOMs.html

8. Wright S. Hospitals’ Use of Observation Stays and Short Inpatient Stays for Medicare Beneficiaries. Office of the Inspector General, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2014. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-12-00040.asp

9. Yancy CW. COVID-19 and African Americans. JAMA. Published online April 15, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6548

10. Levinson DR. Vulnerabilities Remain Under Medicare’s 2-Midnight Hospital Policy. Office of the Inspector General, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2016. Accessed April 18, 2020. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-15-00020.pdf

11. Levinson DR. CMS Improperly Paid Millions of Dollars for Skilled Nursing Facility Services When the Medicare 3-Day Inpatient Hospital Stay Requirement Was Not Met. Office of the Inspector General, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2019. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://www.oig.hhs.gov/oas/reports/region5/51600043.pdf

12. Sheehy A, Shi F, Kind A. Identifying observation stays in Medicare data: policy implications of a definition. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(2):96-100. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3038

13. Solutions to Reduce Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in HHS Programs: OIG’s Top Recommendations. Office of the Inspector General, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2019. Accessed April 18, 2020. https://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/compendium/files/compendium2019.pdf

14. Improving Access to Medicare Coverage Act of 2019, HR 1682, 116th Congress (2019). Accessed April 16, 2020. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/1682

15. Alexander v Azar, 396 F Supp 3d 242 (D CT 2019). Accessed May 26, 2020. https://casetext.com/case/alexander-v-azar-1?

16. Lipsitz L. The 3-night hospital stay and Medicare coverage for skilled nursing care. JAMA. 2013;310(14):1441-1442. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.254845

17. Grebla R, Keohane L, Lee Y, Lipsitz L, Rahman M, Trevedi A. Waiving the three-day rule: admissions and length-of-stay at hospitals and skilled nursing facilities did not increase. Health Affairs (Millwood). 2015;34(8):1324-1330. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0054

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Overlap between Medicare’s Voluntary Bundled Payment and Accountable Care Organization Programs

Voluntary accountable care organizations (ACOs) and bundled payments have concurrently become cornerstone strategies in Medicare’s shift from volume-based fee-for-service toward value-based payment.

Physician practice and hospital participation in Medicare’s largest ACO model, the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP),1 grew to include 561 organizations in 2018. Under MSSP, participants assume financial accountability for the global quality and costs of care for defined populations of Medicare fee-for-service patients. ACOs that manage to maintain or improve quality while achieving savings (ie, containing costs below a predefined population-wide spending benchmark) are eligible to receive a portion of the difference back from Medicare in the form of “shared savings”.

Similarly, hospital participation in Medicare’s bundled payment programs has grown over time. Most notably, more than 700 participants enrolled in the recently concluded Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) initiative,2 Medicare’s largest bundled payment program over the past five years.3 Under BPCI, participants assumed financial accountability for the quality and costs of care for all Medicare patients triggering a qualifying “episode of care”. Participants that limit episode spending below a predefined benchmark without compromising quality were eligible for financial incentives.

As both ACOs and bundled payments grow in prominence and scale, they may increasingly overlap if patients attributed to ACOs receive care at bundled payment hospitals. Overlap could create synergies by increasing incentives to address shared processes (eg, discharge planning) or outcomes (eg, readmissions).4 An ACO focus on reducing hospital admissions could complement bundled payment efforts to increase hospital efficiency.

Conversely, Medicare’s approach to allocating savings and losses can penalize ACOs or bundled payment participants.3 For example, when a patient included in an MSSP ACO population receives episodic care at a hospital participating in BPCI, the historical costs of care for the hospital and the episode type, not the actual costs of care for that specific patient and his/her episode, are counted in the performance of the ACO. In other words, in these cases, the performance of the MSSP ACO is dependent on the historical spending at BPCI hospitals—despite it being out of ACO’s control and having little to do with the actual care its patients receive at BPCI hospitals—and MSSP ACOs cannot benefit from improvements over time. Therefore, MSSP ACOs may be functionally penalized if patients receive care at historically high-cost BPCI hospitals regardless of whether they have considerably improved the value of care delivered. As a corollary, Medicare rules involve a “claw back” stipulation in which savings are recouped from hospitals that participate in both BPCI and MSSP, effectively discouraging participation in both payment models.

Although these dynamics are complex, they highlight an intuitive point that has gained increasing awareness,5 ie, policymakers must understand the magnitude of overlap to evaluate the urgency in coordinating between the payment models. Our objective was to describe the extent of overlap and the characteristics of patients affected by it.

METHODS

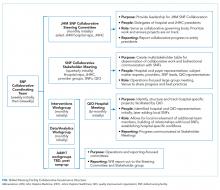

We used 100% institutional Medicare claims, MSSP beneficiary attribution, and BPCI hospital data to identify fee-for-service beneficiaries attributed to MSSP and/or receiving care at BPCI hospitals for its 48 included episodes from the start of BPCI in 2013 quarter 4 through 2016 quarter 4.

We examined the trends in the number of episodes across the following three groups: MSSP-attributed patients hospitalized at BPCI hospitals for an episode included in BPCI (Overlap), MSSP-attributed patients hospitalized for that episode at non-BPCI hospitals (MSSP-only), and non-MSSP-attributed patients hospitalized at BPCI hospitals for a BPCI episode (BPCI-only). We used Medicare and United States Census Bureau data to compare groups with respect to sociodemographic (eg, age, sex, residence in a low-income area),6 clinical (eg, Elixhauser comorbidity index),7 and prior utilization (eg, skilled nursing facility discharge) characteristics.

Categorical and continuous variables were compared using logistic regression and one-way analysis of variance, respectively. Analyses were performed using Stata (StataCorp, College Station, Texas), version 15.0. Statistical tests were 2-tailed and significant at α = 0.05. This study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Pennsylvania.

RESULTS

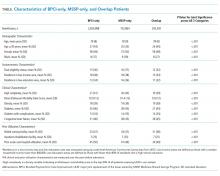

The number of MSSP ACOs increased from 220 in 2013 to 432 in 2016. The number of BPCI hospitals increased from 9 to 389 over this period, peaking at 413 hospitals in 2015. Over our study period, a total of 243,392, 2,824,898, and 702,864 episodes occurred in the Overlap, ACO-only, and BPCI-only groups, respectively (Table). Among episodes, patients in the Overlap group generally showed lower severity than those in other groups, although the differences were small. The BPCI-only, MSSP-only, and Overlap groups also exhibited small differences with respect to other characteristics such as the proportion of patients with Medicare/Medicaid dual-eligibility (15% of individual vs 16% and 12%, respectively) and prior use of skilled nursing facilities (33% vs 34% vs 31%, respectively) and acute care hospitals (45% vs 41% vs 39%, respectively) (P < .001 for all).

The overall overlap facing MSSP patients (overlap as a proportion of all MSSP patients) increased from 0.3% at the end of 2013 to 10% at the end of 2016, whereas over the same period, overlap facing bundled payment patients (overlap as a proportion of all bundled payment patients) increased from 11.9% to 27% (Appendix Figure). Overlap facing MSSP ACOs varied according to episode type, ranging from 3% for both acute myocardial infarction and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease episodes to 18% for automatic implantable cardiac defibrillator episodes at the end of 2016. Similarly, overlap facing bundled payment patients varied from 21% for spinal fusion episodes to 32% for lower extremity joint replacement and automatic implantable cardiac defibrillator episodes.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to describe the sizable and growing overlap facing ACOs with attributed patients who receive care at bundled payment hospitals, as well as bundled payment hospitals that treat patients attributed to ACOs.

The major implication of our findings is that policymakers must address and anticipate forthcoming payment model overlap as a key policy priority. Given the emphasis on ACOs and bundled payments as payment models—for example, Medicare continues to implement both nationwide via the Next Generation ACO model8 and the recently launched BPCI-Advanced program9—policymakers urgently need insights about the extent of payment model overlap. In that context, it is notable that although we have evaluated MSSP and BPCI as flagship programs, true overlap may actually be greater once other programs are considered.

Several factors may underlie the differences in the magnitude of overlap facing bundled payment versus ACO patients. The models differ in how they identify relevant patient populations, with patients falling under bundled payments via hospitalization for certain episode types but patients falling under ACOs via attribution based on the plurality of primary care services. Furthermore, BPCI participation lagged behind MSSP participation in time, while also occurring disproportionately in areas with existing MSSP ACOs.

Given these findings, understanding the implications of overlap should be a priority for future research and policy strategies. Potential policy considerations should include revising cost accounting processes so that when ACO-attributed patients receive episodic care at bundled payment hospitals, actual rather than historical hospital costs are counted toward ACO cost performance. To encourage hospitals to assume more accountability over outcomes—the ostensible overarching goal of value-based payment reform—Medicare could elect not to recoup savings from hospitals in both payment models. Although such changes require careful accounting to protect Medicare from financial losses as it forgoes some savings achieved through payment reforms, this may be worthwhile if hospital engagement in both models yields synergies.

Importantly, any policy changes made to address program overlap would need to accommodate ongoing changes in ACO, bundled payments, and other payment programs. For example, Medicare overhauled MSSP in December 2018. Compared to the earlier rules, in which ACOs could avoid downside financial risk altogether via “upside only” arrangements for up to six years, new MSSP rules require all participants to assume downside risk after several years of participation. Separately, forthcoming payment reforms such as direct contracting10 may draw clinicians and hospitals previously not participating in either Medicare fee-for-service or value-based payment models into payment reform. These factors may affect overlap in unpredictable ways (eg, they may increase the overlap by increasing the number of patients whose care is covered by different payment models or they may decrease overlap by raising the financial stakes of payment reforms to a degree that organizations drop out altogether).

This study has limitations. First, generalizability is limited by the fact that our analysis did not include bundled payment episodes assigned to physician group participants in BPCI or hospitals in mandatory joint replacement bundles under the Medicare Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement model.11 Second, although this study provides the first description of overlap between ACO and bundled payment programs, it was descriptive in nature. Future research is needed to evaluate the impact of overlap on clinical, quality, and cost outcomes. This is particularly important because although we observed only small differences in patient characteristics among MSSP-only, BPCI-only, and Overlap groups, characteristics could change differentially over time. Payment reforms must be carefully monitored for potentially unintended consequences that could arise from differential changes in patient characteristics (eg, cherry-picking behavior that is disadvantageous to vulnerable individuals).

Nonetheless, this study underscores the importance and extent of overlap and the urgency to consider policy measures to coordinate between the payment models.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank research assistance from Sandra Vanderslice who did not receive any compensation for her work. This research was supported in part by The Commonwealth Fund. Rachel Werner was supported in part by K24-AG047908 from the NIA.

1. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Shared Savings Program. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-For-Service-Payment/sharedsavingsprogram/index.html. Accessed July 22, 2019.

2. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) Initiative: General Information. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bundled-payments/. Accessed July 22, 2019.

3. Mechanic RE. When new Medicare payment systems collide. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(18):1706-1709. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1601464.

4. Ryan AM, Krinsky S, Adler-Milstein J, Damberg CL, Maurer KA, Hollingsworth JM. Association between hospitals’ engagement in value-based reforms and readmission reduction in the hospital readmission reduction program. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(6):863-868. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0518.

5. Liao JM, Dykstra SE, Werner RM, Navathe AS. BPCI Advanced will further emphasize the need to address overlap between bundled payments and accountable care organizations. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20180409.159181/full/. Accessed May 14, 2019.

6. Census Bureau. United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/. Accessed May 14, 2018.

7. van Walraven C, Austin PC, Jennings A, Quan H, Forster AJ. A modification of the elixhauser comorbidity measures into a point system for hospital death using administrative data. Med Care. 2009;47(6):626-633. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819432e5.

8. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Next, Generation ACO Model. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/next-generation-aco-model/. Accessed July 22, 2019.

9. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. BPCI Advanced. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bpci-advanced. Accessed July 22, 2019.

10. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Direct Contracting. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/direct-contracting. Accessed July 22, 2019.

11. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement Model. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/CJR. Accessed July 22, 2019.

Voluntary accountable care organizations (ACOs) and bundled payments have concurrently become cornerstone strategies in Medicare’s shift from volume-based fee-for-service toward value-based payment.

Physician practice and hospital participation in Medicare’s largest ACO model, the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP),1 grew to include 561 organizations in 2018. Under MSSP, participants assume financial accountability for the global quality and costs of care for defined populations of Medicare fee-for-service patients. ACOs that manage to maintain or improve quality while achieving savings (ie, containing costs below a predefined population-wide spending benchmark) are eligible to receive a portion of the difference back from Medicare in the form of “shared savings”.

Similarly, hospital participation in Medicare’s bundled payment programs has grown over time. Most notably, more than 700 participants enrolled in the recently concluded Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) initiative,2 Medicare’s largest bundled payment program over the past five years.3 Under BPCI, participants assumed financial accountability for the quality and costs of care for all Medicare patients triggering a qualifying “episode of care”. Participants that limit episode spending below a predefined benchmark without compromising quality were eligible for financial incentives.

As both ACOs and bundled payments grow in prominence and scale, they may increasingly overlap if patients attributed to ACOs receive care at bundled payment hospitals. Overlap could create synergies by increasing incentives to address shared processes (eg, discharge planning) or outcomes (eg, readmissions).4 An ACO focus on reducing hospital admissions could complement bundled payment efforts to increase hospital efficiency.

Conversely, Medicare’s approach to allocating savings and losses can penalize ACOs or bundled payment participants.3 For example, when a patient included in an MSSP ACO population receives episodic care at a hospital participating in BPCI, the historical costs of care for the hospital and the episode type, not the actual costs of care for that specific patient and his/her episode, are counted in the performance of the ACO. In other words, in these cases, the performance of the MSSP ACO is dependent on the historical spending at BPCI hospitals—despite it being out of ACO’s control and having little to do with the actual care its patients receive at BPCI hospitals—and MSSP ACOs cannot benefit from improvements over time. Therefore, MSSP ACOs may be functionally penalized if patients receive care at historically high-cost BPCI hospitals regardless of whether they have considerably improved the value of care delivered. As a corollary, Medicare rules involve a “claw back” stipulation in which savings are recouped from hospitals that participate in both BPCI and MSSP, effectively discouraging participation in both payment models.

Although these dynamics are complex, they highlight an intuitive point that has gained increasing awareness,5 ie, policymakers must understand the magnitude of overlap to evaluate the urgency in coordinating between the payment models. Our objective was to describe the extent of overlap and the characteristics of patients affected by it.

METHODS

We used 100% institutional Medicare claims, MSSP beneficiary attribution, and BPCI hospital data to identify fee-for-service beneficiaries attributed to MSSP and/or receiving care at BPCI hospitals for its 48 included episodes from the start of BPCI in 2013 quarter 4 through 2016 quarter 4.

We examined the trends in the number of episodes across the following three groups: MSSP-attributed patients hospitalized at BPCI hospitals for an episode included in BPCI (Overlap), MSSP-attributed patients hospitalized for that episode at non-BPCI hospitals (MSSP-only), and non-MSSP-attributed patients hospitalized at BPCI hospitals for a BPCI episode (BPCI-only). We used Medicare and United States Census Bureau data to compare groups with respect to sociodemographic (eg, age, sex, residence in a low-income area),6 clinical (eg, Elixhauser comorbidity index),7 and prior utilization (eg, skilled nursing facility discharge) characteristics.

Categorical and continuous variables were compared using logistic regression and one-way analysis of variance, respectively. Analyses were performed using Stata (StataCorp, College Station, Texas), version 15.0. Statistical tests were 2-tailed and significant at α = 0.05. This study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Pennsylvania.

RESULTS

The number of MSSP ACOs increased from 220 in 2013 to 432 in 2016. The number of BPCI hospitals increased from 9 to 389 over this period, peaking at 413 hospitals in 2015. Over our study period, a total of 243,392, 2,824,898, and 702,864 episodes occurred in the Overlap, ACO-only, and BPCI-only groups, respectively (Table). Among episodes, patients in the Overlap group generally showed lower severity than those in other groups, although the differences were small. The BPCI-only, MSSP-only, and Overlap groups also exhibited small differences with respect to other characteristics such as the proportion of patients with Medicare/Medicaid dual-eligibility (15% of individual vs 16% and 12%, respectively) and prior use of skilled nursing facilities (33% vs 34% vs 31%, respectively) and acute care hospitals (45% vs 41% vs 39%, respectively) (P < .001 for all).

The overall overlap facing MSSP patients (overlap as a proportion of all MSSP patients) increased from 0.3% at the end of 2013 to 10% at the end of 2016, whereas over the same period, overlap facing bundled payment patients (overlap as a proportion of all bundled payment patients) increased from 11.9% to 27% (Appendix Figure). Overlap facing MSSP ACOs varied according to episode type, ranging from 3% for both acute myocardial infarction and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease episodes to 18% for automatic implantable cardiac defibrillator episodes at the end of 2016. Similarly, overlap facing bundled payment patients varied from 21% for spinal fusion episodes to 32% for lower extremity joint replacement and automatic implantable cardiac defibrillator episodes.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to describe the sizable and growing overlap facing ACOs with attributed patients who receive care at bundled payment hospitals, as well as bundled payment hospitals that treat patients attributed to ACOs.

The major implication of our findings is that policymakers must address and anticipate forthcoming payment model overlap as a key policy priority. Given the emphasis on ACOs and bundled payments as payment models—for example, Medicare continues to implement both nationwide via the Next Generation ACO model8 and the recently launched BPCI-Advanced program9—policymakers urgently need insights about the extent of payment model overlap. In that context, it is notable that although we have evaluated MSSP and BPCI as flagship programs, true overlap may actually be greater once other programs are considered.

Several factors may underlie the differences in the magnitude of overlap facing bundled payment versus ACO patients. The models differ in how they identify relevant patient populations, with patients falling under bundled payments via hospitalization for certain episode types but patients falling under ACOs via attribution based on the plurality of primary care services. Furthermore, BPCI participation lagged behind MSSP participation in time, while also occurring disproportionately in areas with existing MSSP ACOs.

Given these findings, understanding the implications of overlap should be a priority for future research and policy strategies. Potential policy considerations should include revising cost accounting processes so that when ACO-attributed patients receive episodic care at bundled payment hospitals, actual rather than historical hospital costs are counted toward ACO cost performance. To encourage hospitals to assume more accountability over outcomes—the ostensible overarching goal of value-based payment reform—Medicare could elect not to recoup savings from hospitals in both payment models. Although such changes require careful accounting to protect Medicare from financial losses as it forgoes some savings achieved through payment reforms, this may be worthwhile if hospital engagement in both models yields synergies.

Importantly, any policy changes made to address program overlap would need to accommodate ongoing changes in ACO, bundled payments, and other payment programs. For example, Medicare overhauled MSSP in December 2018. Compared to the earlier rules, in which ACOs could avoid downside financial risk altogether via “upside only” arrangements for up to six years, new MSSP rules require all participants to assume downside risk after several years of participation. Separately, forthcoming payment reforms such as direct contracting10 may draw clinicians and hospitals previously not participating in either Medicare fee-for-service or value-based payment models into payment reform. These factors may affect overlap in unpredictable ways (eg, they may increase the overlap by increasing the number of patients whose care is covered by different payment models or they may decrease overlap by raising the financial stakes of payment reforms to a degree that organizations drop out altogether).

This study has limitations. First, generalizability is limited by the fact that our analysis did not include bundled payment episodes assigned to physician group participants in BPCI or hospitals in mandatory joint replacement bundles under the Medicare Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement model.11 Second, although this study provides the first description of overlap between ACO and bundled payment programs, it was descriptive in nature. Future research is needed to evaluate the impact of overlap on clinical, quality, and cost outcomes. This is particularly important because although we observed only small differences in patient characteristics among MSSP-only, BPCI-only, and Overlap groups, characteristics could change differentially over time. Payment reforms must be carefully monitored for potentially unintended consequences that could arise from differential changes in patient characteristics (eg, cherry-picking behavior that is disadvantageous to vulnerable individuals).

Nonetheless, this study underscores the importance and extent of overlap and the urgency to consider policy measures to coordinate between the payment models.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank research assistance from Sandra Vanderslice who did not receive any compensation for her work. This research was supported in part by The Commonwealth Fund. Rachel Werner was supported in part by K24-AG047908 from the NIA.

Voluntary accountable care organizations (ACOs) and bundled payments have concurrently become cornerstone strategies in Medicare’s shift from volume-based fee-for-service toward value-based payment.

Physician practice and hospital participation in Medicare’s largest ACO model, the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP),1 grew to include 561 organizations in 2018. Under MSSP, participants assume financial accountability for the global quality and costs of care for defined populations of Medicare fee-for-service patients. ACOs that manage to maintain or improve quality while achieving savings (ie, containing costs below a predefined population-wide spending benchmark) are eligible to receive a portion of the difference back from Medicare in the form of “shared savings”.

Similarly, hospital participation in Medicare’s bundled payment programs has grown over time. Most notably, more than 700 participants enrolled in the recently concluded Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) initiative,2 Medicare’s largest bundled payment program over the past five years.3 Under BPCI, participants assumed financial accountability for the quality and costs of care for all Medicare patients triggering a qualifying “episode of care”. Participants that limit episode spending below a predefined benchmark without compromising quality were eligible for financial incentives.

As both ACOs and bundled payments grow in prominence and scale, they may increasingly overlap if patients attributed to ACOs receive care at bundled payment hospitals. Overlap could create synergies by increasing incentives to address shared processes (eg, discharge planning) or outcomes (eg, readmissions).4 An ACO focus on reducing hospital admissions could complement bundled payment efforts to increase hospital efficiency.

Conversely, Medicare’s approach to allocating savings and losses can penalize ACOs or bundled payment participants.3 For example, when a patient included in an MSSP ACO population receives episodic care at a hospital participating in BPCI, the historical costs of care for the hospital and the episode type, not the actual costs of care for that specific patient and his/her episode, are counted in the performance of the ACO. In other words, in these cases, the performance of the MSSP ACO is dependent on the historical spending at BPCI hospitals—despite it being out of ACO’s control and having little to do with the actual care its patients receive at BPCI hospitals—and MSSP ACOs cannot benefit from improvements over time. Therefore, MSSP ACOs may be functionally penalized if patients receive care at historically high-cost BPCI hospitals regardless of whether they have considerably improved the value of care delivered. As a corollary, Medicare rules involve a “claw back” stipulation in which savings are recouped from hospitals that participate in both BPCI and MSSP, effectively discouraging participation in both payment models.

Although these dynamics are complex, they highlight an intuitive point that has gained increasing awareness,5 ie, policymakers must understand the magnitude of overlap to evaluate the urgency in coordinating between the payment models. Our objective was to describe the extent of overlap and the characteristics of patients affected by it.

METHODS

We used 100% institutional Medicare claims, MSSP beneficiary attribution, and BPCI hospital data to identify fee-for-service beneficiaries attributed to MSSP and/or receiving care at BPCI hospitals for its 48 included episodes from the start of BPCI in 2013 quarter 4 through 2016 quarter 4.

We examined the trends in the number of episodes across the following three groups: MSSP-attributed patients hospitalized at BPCI hospitals for an episode included in BPCI (Overlap), MSSP-attributed patients hospitalized for that episode at non-BPCI hospitals (MSSP-only), and non-MSSP-attributed patients hospitalized at BPCI hospitals for a BPCI episode (BPCI-only). We used Medicare and United States Census Bureau data to compare groups with respect to sociodemographic (eg, age, sex, residence in a low-income area),6 clinical (eg, Elixhauser comorbidity index),7 and prior utilization (eg, skilled nursing facility discharge) characteristics.

Categorical and continuous variables were compared using logistic regression and one-way analysis of variance, respectively. Analyses were performed using Stata (StataCorp, College Station, Texas), version 15.0. Statistical tests were 2-tailed and significant at α = 0.05. This study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Pennsylvania.

RESULTS

The number of MSSP ACOs increased from 220 in 2013 to 432 in 2016. The number of BPCI hospitals increased from 9 to 389 over this period, peaking at 413 hospitals in 2015. Over our study period, a total of 243,392, 2,824,898, and 702,864 episodes occurred in the Overlap, ACO-only, and BPCI-only groups, respectively (Table). Among episodes, patients in the Overlap group generally showed lower severity than those in other groups, although the differences were small. The BPCI-only, MSSP-only, and Overlap groups also exhibited small differences with respect to other characteristics such as the proportion of patients with Medicare/Medicaid dual-eligibility (15% of individual vs 16% and 12%, respectively) and prior use of skilled nursing facilities (33% vs 34% vs 31%, respectively) and acute care hospitals (45% vs 41% vs 39%, respectively) (P < .001 for all).

The overall overlap facing MSSP patients (overlap as a proportion of all MSSP patients) increased from 0.3% at the end of 2013 to 10% at the end of 2016, whereas over the same period, overlap facing bundled payment patients (overlap as a proportion of all bundled payment patients) increased from 11.9% to 27% (Appendix Figure). Overlap facing MSSP ACOs varied according to episode type, ranging from 3% for both acute myocardial infarction and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease episodes to 18% for automatic implantable cardiac defibrillator episodes at the end of 2016. Similarly, overlap facing bundled payment patients varied from 21% for spinal fusion episodes to 32% for lower extremity joint replacement and automatic implantable cardiac defibrillator episodes.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to describe the sizable and growing overlap facing ACOs with attributed patients who receive care at bundled payment hospitals, as well as bundled payment hospitals that treat patients attributed to ACOs.

The major implication of our findings is that policymakers must address and anticipate forthcoming payment model overlap as a key policy priority. Given the emphasis on ACOs and bundled payments as payment models—for example, Medicare continues to implement both nationwide via the Next Generation ACO model8 and the recently launched BPCI-Advanced program9—policymakers urgently need insights about the extent of payment model overlap. In that context, it is notable that although we have evaluated MSSP and BPCI as flagship programs, true overlap may actually be greater once other programs are considered.

Several factors may underlie the differences in the magnitude of overlap facing bundled payment versus ACO patients. The models differ in how they identify relevant patient populations, with patients falling under bundled payments via hospitalization for certain episode types but patients falling under ACOs via attribution based on the plurality of primary care services. Furthermore, BPCI participation lagged behind MSSP participation in time, while also occurring disproportionately in areas with existing MSSP ACOs.

Given these findings, understanding the implications of overlap should be a priority for future research and policy strategies. Potential policy considerations should include revising cost accounting processes so that when ACO-attributed patients receive episodic care at bundled payment hospitals, actual rather than historical hospital costs are counted toward ACO cost performance. To encourage hospitals to assume more accountability over outcomes—the ostensible overarching goal of value-based payment reform—Medicare could elect not to recoup savings from hospitals in both payment models. Although such changes require careful accounting to protect Medicare from financial losses as it forgoes some savings achieved through payment reforms, this may be worthwhile if hospital engagement in both models yields synergies.

Importantly, any policy changes made to address program overlap would need to accommodate ongoing changes in ACO, bundled payments, and other payment programs. For example, Medicare overhauled MSSP in December 2018. Compared to the earlier rules, in which ACOs could avoid downside financial risk altogether via “upside only” arrangements for up to six years, new MSSP rules require all participants to assume downside risk after several years of participation. Separately, forthcoming payment reforms such as direct contracting10 may draw clinicians and hospitals previously not participating in either Medicare fee-for-service or value-based payment models into payment reform. These factors may affect overlap in unpredictable ways (eg, they may increase the overlap by increasing the number of patients whose care is covered by different payment models or they may decrease overlap by raising the financial stakes of payment reforms to a degree that organizations drop out altogether).