User login

The Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program and Observation Hospitalizations

The Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) was designed to improve quality and safety for traditional Medicare beneficiaries.1 Since 2012, the program has reduced payments to institutions with excess inpatient rehospitalizations within 30 days of an index inpatient stay for targeted medical conditions. Observation hospitalizations, billed as outpatient and covered under Medicare Part B, are not counted as index or 30-day rehospitalizations under HRRP methods. Historically, observation occurred almost exclusively in observation units. Now, observation hospitalizations commonly occur on hospital wards, even in intensive care units, and are often clinically indistinguishable from inpatient hospitalizations billed under Medicare Part A.2 The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) state that beneficiaries expected to need 2 or more midnights of hospital care should generally be considered inpatients, yet observation hospitalizations commonly exceed 2 midnights.3,4

The increasing use of observation hospitalizations5,6 raises questions about its impact on HRRP measurements. While observation hospitalizations have been studied as part of 30-day follow-up (numerator) to index inpatient hospitalizations,5,6 little is known about how observation hospitalizations impact rates when they are factored in as both index stays (denominator) and in the 30-day rehospitalization rate (numerator).2,7 We analyzed the complete combinations of observation and inpatient hospitalizations, including observation as index hospitalization, rehospitalization, or both, to determine HRRP impact.

METHODS

Study Cohort

Medicare fee-for-service standard claim files for all beneficiaries (100% population file version) were used to examine qualifying index inpatient and observation hospitalizations between January 1, 2014, and November 30, 2014, as well as 30-day inpatient and observation rehospitalizations. We used CMS’s 30-day methodology, including previously described standard exclusions (Appendix Figure),8 except for the aforementioned inclusion of observation hospitalizations. Observation hospitalizations were identified using established methods,3,9,10 excluding those observation encounters coded with revenue center code 0761 only3,10 in order to be most conservative in identifying observation hospitalizations (Appendix Figure). These methods assign hospitalization type (observation or inpatient) based on the final (billed) status. The terms hospitalization and rehospitalization refer to both inpatient and observation encounters. The University of Wisconsin Health Sciences Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program

Index HRRP admissions for congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, myocardial infarction, and pneumonia were examined as a prespecified subgroup.1,11 Coronary artery bypass grafting, total hip replacement, and total knee replacement were excluded in this analysis, as no crosswalk exists between International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes and Current Procedural Terminology codes for these surgical conditions.11

Analysis

Analyses were conducted at the encounter level, consistent with CMS methods.8 Descriptive statistics were used to summarize index and 30-day outcomes.

RESULTS

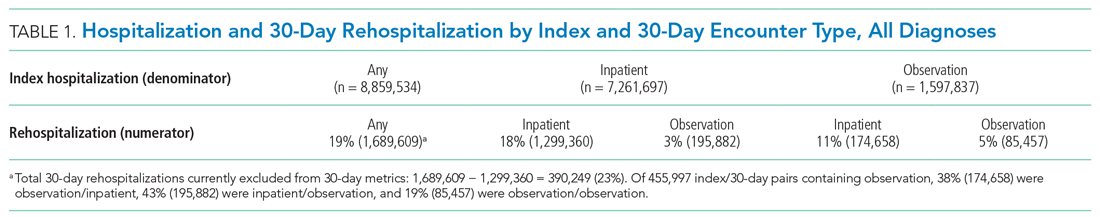

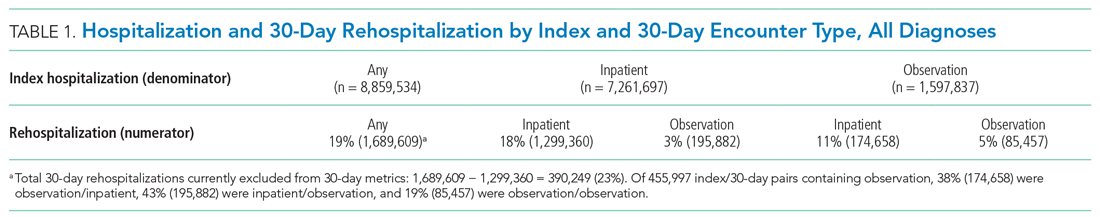

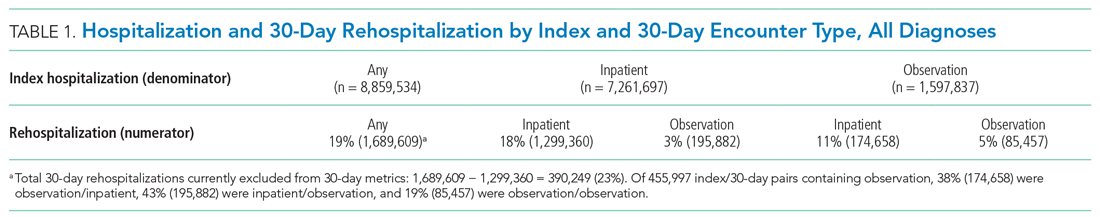

Of 8,859,534 index hospitalizations for any reason or diagnosis, 1,597,837 (18%) were observation and 7,261,697 (82%) were inpatient. Including all hospitalizations, 23% (390,249/1,689,609) of rehospitalizations were excluded from readmission measurement by virtue of the index hospitalization and/or 30-day rehospitalization being observation (Table 1 and Table 2).

For the subgroup of HRRP conditions, 418,923 (11%) and 3,387,849 (89%) of 3,806,772 index hospitalizations were observation and inpatient, respectively. Including HRRP conditions only, 18% (155,553/876,033) of rehospitalizations were excluded from HRRP reporting owing to observation hospitalization as index, 30-day outcome, or both. Of 188,430 index/30-day pairs containing observation, 34% (63,740) were observation/inpatient, 53% (100,343) were inpatient/observation, and 13% (24,347) were observation/observation (Table 1 and Table 2).

DISCUSSION

By ignoring observation hospitalizations in 30-day HRRP quality metrics, nearly one of five potential rehospitalizations is missed. Observation hospitalizations commonly occur as either the index event or 30-day outcome, so accurately determining 30-day HRRP rates must include observation in both positions. Given hospital variability in observation use,3,7 these findings are critically important to accurately understand rehospitalization risk and indicate that HRRP may not be fulfilling its intended purpose.

Including all hospitalizations for any diagnosis, we found that observation and inpatient hospitalizations commonly occur within 30 days of each other. Nearly one in four hospitalization/rehospitalization pairs include observation as index, 30-day rehospitalization, or both. Although not directly related to HRRP metrics, these data demonstrate the growing importance and presence of outpatient (observation) hospitalizations in the Medicare program.

Our study adds to the evolving body of literature investigating quality measures under a two-tiered hospital system where inpatient hospitalizations are counted and observation hospitalizations are not. Figueroa and colleagues12 found that improvements in avoidable admission rates for patients with ambulatory care–sensitive conditions were largely attributable to a shift from counted inpatient to uncounted observation hospitalizations. In other words, hospitalizations were still occurring, but were not being tallied due to outpatient (observation) classification. Zuckerman et al5 and the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC)6 concluded that readmissions improvements recognized by the HRRP were not explained by a shift to more observation hospitalizations following an index inpatient hospitalization; however, both studies included observation hospitalizations as part of 30-day rehospitalization (numerator) only, not also as part of index hospitalizations (denominator). Our study confirms the importance of including observation hospitalizations in both the index (denominator) and 30-day (numerator) rehospitalization positions to determine the full impact of observation hospitalizations on Medicare’s HRRP metrics.

Our study has limitations. We focused on nonsurgical HRRP conditions, which may have impacted our findings. Additionally, some authors have suggested including emergency department (ED) visits in rehospitalization studies.7 Although ED visits occur at hospitals, they are not hospitalizations; we excluded them as a first step. Had we included ED visits, encounters excluded from HRRP measurements would have increased, suggesting that our findings, while sizeable, are likely conservative. Additionally, we could not determine the merits or medical necessity of hospitalizations (inpatient or outpatient observation), but this is an inherent limitation in a large claims dataset like this one. Finally, we only included a single year of data in this analysis, and it is possible that additional years of data would show different trends. However, we have no reason to believe the study year to be an aberrant year; if anything, observation rates have increased since 2014,6 again pointing out that while our findings are sizable, they are likely conservative. Future research could include additional years of data to confirm even greater proportions of rehospitalizations exempt from HRRP over time due to observation hospitalizations as index and/or 30-day events.

Outpatient observation hospitalizations can occur anywhere in the hospital and are often clinically similar to inpatient hospitalizations, yet observation hospitalizations are essentially invisible under inpatient quality metrics. Requiring the HRRP to include observation hospitalizations is the most obvious solution, but this could require major regulatory and legislative change11,13—change that would fix a metric but fail to address broad policy concerns inherent in the two-tiered observation and inpatient billing distinction. Instead, CMS and Congress might consider this an opportunity to address the oxymoron of “outpatient hospitalizations” by engaging in comprehensive observation reform.

1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP). Accessed March 12, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program

2. Sabbatini AK, Wright B. Excluding observation stays from readmission rates—what quality measures are missing. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(22):2062-2065. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1800732

3. Sheehy AM, Powell WR, Kaiksow FA, et al. Thirty-day re-observation, chronic re-observation, and neighborhood disadvantage. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(12):2644-2654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.06.059

4. US Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Inspector General. Vulnerabilities remain under Medicare’s 2-midnight hospital policy. December 19, 2016. Accessed February 11, 2021. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-15-00020.asp

5. Zuckerman RB, Sheingold SH, Orav EJ, Ruhter J, Epstein AM. Readmissions, observation and the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(16):1543-1551. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1513024

6. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Mandated report: the effects of the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. In: Report to the Congress: Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System. 2018;3-31. Accessed March 17, 2021. Available at: http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/jun18_medpacreporttocongress_rev_nov2019_note_sec.pdf?sfvrsn=0

7. Wadhera RK, Yeh RW, Maddox KEJ. The Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program—time for a reboot. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(24):2289-2291. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1901225

8. National Quality Forum. Measure #1789: Hospital-wide all-cause unplanned readmission measure. Accessed January 30, 2021. https://www.qualityforum.org/ProjectDescription.aspx?projectID=73619

9. Sheehy AM, Shi F, Kind AJH. Identifying observation stays in Medicare data: policy implications of a definition. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(2):96-100. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3038

10. Powell WR, Kaiksow FA, Kind AJH, Sheehy AM. What is an observation stay? Evaluating the use of hospital observation stays in Medicare. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(7):1568-1572. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16441

11. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) Archives. Accessed February 10, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/HRRP-Archives

12. Figueroa JF, Burke LG, Zheng J, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Trends in hospitalization vs observation stay for ambulatory care-sensitive conditions. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(12): 1714-1716. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.3177

13. Public Law 111-148, Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 111th Congress. March 23, 2010. Accessed March 12, 2021.https://www.congress.gov/111/plaws/publ148/PLAW-111publ148.pdf

The Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) was designed to improve quality and safety for traditional Medicare beneficiaries.1 Since 2012, the program has reduced payments to institutions with excess inpatient rehospitalizations within 30 days of an index inpatient stay for targeted medical conditions. Observation hospitalizations, billed as outpatient and covered under Medicare Part B, are not counted as index or 30-day rehospitalizations under HRRP methods. Historically, observation occurred almost exclusively in observation units. Now, observation hospitalizations commonly occur on hospital wards, even in intensive care units, and are often clinically indistinguishable from inpatient hospitalizations billed under Medicare Part A.2 The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) state that beneficiaries expected to need 2 or more midnights of hospital care should generally be considered inpatients, yet observation hospitalizations commonly exceed 2 midnights.3,4

The increasing use of observation hospitalizations5,6 raises questions about its impact on HRRP measurements. While observation hospitalizations have been studied as part of 30-day follow-up (numerator) to index inpatient hospitalizations,5,6 little is known about how observation hospitalizations impact rates when they are factored in as both index stays (denominator) and in the 30-day rehospitalization rate (numerator).2,7 We analyzed the complete combinations of observation and inpatient hospitalizations, including observation as index hospitalization, rehospitalization, or both, to determine HRRP impact.

METHODS

Study Cohort

Medicare fee-for-service standard claim files for all beneficiaries (100% population file version) were used to examine qualifying index inpatient and observation hospitalizations between January 1, 2014, and November 30, 2014, as well as 30-day inpatient and observation rehospitalizations. We used CMS’s 30-day methodology, including previously described standard exclusions (Appendix Figure),8 except for the aforementioned inclusion of observation hospitalizations. Observation hospitalizations were identified using established methods,3,9,10 excluding those observation encounters coded with revenue center code 0761 only3,10 in order to be most conservative in identifying observation hospitalizations (Appendix Figure). These methods assign hospitalization type (observation or inpatient) based on the final (billed) status. The terms hospitalization and rehospitalization refer to both inpatient and observation encounters. The University of Wisconsin Health Sciences Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program

Index HRRP admissions for congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, myocardial infarction, and pneumonia were examined as a prespecified subgroup.1,11 Coronary artery bypass grafting, total hip replacement, and total knee replacement were excluded in this analysis, as no crosswalk exists between International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes and Current Procedural Terminology codes for these surgical conditions.11

Analysis

Analyses were conducted at the encounter level, consistent with CMS methods.8 Descriptive statistics were used to summarize index and 30-day outcomes.

RESULTS

Of 8,859,534 index hospitalizations for any reason or diagnosis, 1,597,837 (18%) were observation and 7,261,697 (82%) were inpatient. Including all hospitalizations, 23% (390,249/1,689,609) of rehospitalizations were excluded from readmission measurement by virtue of the index hospitalization and/or 30-day rehospitalization being observation (Table 1 and Table 2).

For the subgroup of HRRP conditions, 418,923 (11%) and 3,387,849 (89%) of 3,806,772 index hospitalizations were observation and inpatient, respectively. Including HRRP conditions only, 18% (155,553/876,033) of rehospitalizations were excluded from HRRP reporting owing to observation hospitalization as index, 30-day outcome, or both. Of 188,430 index/30-day pairs containing observation, 34% (63,740) were observation/inpatient, 53% (100,343) were inpatient/observation, and 13% (24,347) were observation/observation (Table 1 and Table 2).

DISCUSSION

By ignoring observation hospitalizations in 30-day HRRP quality metrics, nearly one of five potential rehospitalizations is missed. Observation hospitalizations commonly occur as either the index event or 30-day outcome, so accurately determining 30-day HRRP rates must include observation in both positions. Given hospital variability in observation use,3,7 these findings are critically important to accurately understand rehospitalization risk and indicate that HRRP may not be fulfilling its intended purpose.

Including all hospitalizations for any diagnosis, we found that observation and inpatient hospitalizations commonly occur within 30 days of each other. Nearly one in four hospitalization/rehospitalization pairs include observation as index, 30-day rehospitalization, or both. Although not directly related to HRRP metrics, these data demonstrate the growing importance and presence of outpatient (observation) hospitalizations in the Medicare program.

Our study adds to the evolving body of literature investigating quality measures under a two-tiered hospital system where inpatient hospitalizations are counted and observation hospitalizations are not. Figueroa and colleagues12 found that improvements in avoidable admission rates for patients with ambulatory care–sensitive conditions were largely attributable to a shift from counted inpatient to uncounted observation hospitalizations. In other words, hospitalizations were still occurring, but were not being tallied due to outpatient (observation) classification. Zuckerman et al5 and the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC)6 concluded that readmissions improvements recognized by the HRRP were not explained by a shift to more observation hospitalizations following an index inpatient hospitalization; however, both studies included observation hospitalizations as part of 30-day rehospitalization (numerator) only, not also as part of index hospitalizations (denominator). Our study confirms the importance of including observation hospitalizations in both the index (denominator) and 30-day (numerator) rehospitalization positions to determine the full impact of observation hospitalizations on Medicare’s HRRP metrics.

Our study has limitations. We focused on nonsurgical HRRP conditions, which may have impacted our findings. Additionally, some authors have suggested including emergency department (ED) visits in rehospitalization studies.7 Although ED visits occur at hospitals, they are not hospitalizations; we excluded them as a first step. Had we included ED visits, encounters excluded from HRRP measurements would have increased, suggesting that our findings, while sizeable, are likely conservative. Additionally, we could not determine the merits or medical necessity of hospitalizations (inpatient or outpatient observation), but this is an inherent limitation in a large claims dataset like this one. Finally, we only included a single year of data in this analysis, and it is possible that additional years of data would show different trends. However, we have no reason to believe the study year to be an aberrant year; if anything, observation rates have increased since 2014,6 again pointing out that while our findings are sizable, they are likely conservative. Future research could include additional years of data to confirm even greater proportions of rehospitalizations exempt from HRRP over time due to observation hospitalizations as index and/or 30-day events.

Outpatient observation hospitalizations can occur anywhere in the hospital and are often clinically similar to inpatient hospitalizations, yet observation hospitalizations are essentially invisible under inpatient quality metrics. Requiring the HRRP to include observation hospitalizations is the most obvious solution, but this could require major regulatory and legislative change11,13—change that would fix a metric but fail to address broad policy concerns inherent in the two-tiered observation and inpatient billing distinction. Instead, CMS and Congress might consider this an opportunity to address the oxymoron of “outpatient hospitalizations” by engaging in comprehensive observation reform.

The Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) was designed to improve quality and safety for traditional Medicare beneficiaries.1 Since 2012, the program has reduced payments to institutions with excess inpatient rehospitalizations within 30 days of an index inpatient stay for targeted medical conditions. Observation hospitalizations, billed as outpatient and covered under Medicare Part B, are not counted as index or 30-day rehospitalizations under HRRP methods. Historically, observation occurred almost exclusively in observation units. Now, observation hospitalizations commonly occur on hospital wards, even in intensive care units, and are often clinically indistinguishable from inpatient hospitalizations billed under Medicare Part A.2 The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) state that beneficiaries expected to need 2 or more midnights of hospital care should generally be considered inpatients, yet observation hospitalizations commonly exceed 2 midnights.3,4

The increasing use of observation hospitalizations5,6 raises questions about its impact on HRRP measurements. While observation hospitalizations have been studied as part of 30-day follow-up (numerator) to index inpatient hospitalizations,5,6 little is known about how observation hospitalizations impact rates when they are factored in as both index stays (denominator) and in the 30-day rehospitalization rate (numerator).2,7 We analyzed the complete combinations of observation and inpatient hospitalizations, including observation as index hospitalization, rehospitalization, or both, to determine HRRP impact.

METHODS

Study Cohort

Medicare fee-for-service standard claim files for all beneficiaries (100% population file version) were used to examine qualifying index inpatient and observation hospitalizations between January 1, 2014, and November 30, 2014, as well as 30-day inpatient and observation rehospitalizations. We used CMS’s 30-day methodology, including previously described standard exclusions (Appendix Figure),8 except for the aforementioned inclusion of observation hospitalizations. Observation hospitalizations were identified using established methods,3,9,10 excluding those observation encounters coded with revenue center code 0761 only3,10 in order to be most conservative in identifying observation hospitalizations (Appendix Figure). These methods assign hospitalization type (observation or inpatient) based on the final (billed) status. The terms hospitalization and rehospitalization refer to both inpatient and observation encounters. The University of Wisconsin Health Sciences Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program

Index HRRP admissions for congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, myocardial infarction, and pneumonia were examined as a prespecified subgroup.1,11 Coronary artery bypass grafting, total hip replacement, and total knee replacement were excluded in this analysis, as no crosswalk exists between International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes and Current Procedural Terminology codes for these surgical conditions.11

Analysis

Analyses were conducted at the encounter level, consistent with CMS methods.8 Descriptive statistics were used to summarize index and 30-day outcomes.

RESULTS

Of 8,859,534 index hospitalizations for any reason or diagnosis, 1,597,837 (18%) were observation and 7,261,697 (82%) were inpatient. Including all hospitalizations, 23% (390,249/1,689,609) of rehospitalizations were excluded from readmission measurement by virtue of the index hospitalization and/or 30-day rehospitalization being observation (Table 1 and Table 2).

For the subgroup of HRRP conditions, 418,923 (11%) and 3,387,849 (89%) of 3,806,772 index hospitalizations were observation and inpatient, respectively. Including HRRP conditions only, 18% (155,553/876,033) of rehospitalizations were excluded from HRRP reporting owing to observation hospitalization as index, 30-day outcome, or both. Of 188,430 index/30-day pairs containing observation, 34% (63,740) were observation/inpatient, 53% (100,343) were inpatient/observation, and 13% (24,347) were observation/observation (Table 1 and Table 2).

DISCUSSION

By ignoring observation hospitalizations in 30-day HRRP quality metrics, nearly one of five potential rehospitalizations is missed. Observation hospitalizations commonly occur as either the index event or 30-day outcome, so accurately determining 30-day HRRP rates must include observation in both positions. Given hospital variability in observation use,3,7 these findings are critically important to accurately understand rehospitalization risk and indicate that HRRP may not be fulfilling its intended purpose.

Including all hospitalizations for any diagnosis, we found that observation and inpatient hospitalizations commonly occur within 30 days of each other. Nearly one in four hospitalization/rehospitalization pairs include observation as index, 30-day rehospitalization, or both. Although not directly related to HRRP metrics, these data demonstrate the growing importance and presence of outpatient (observation) hospitalizations in the Medicare program.

Our study adds to the evolving body of literature investigating quality measures under a two-tiered hospital system where inpatient hospitalizations are counted and observation hospitalizations are not. Figueroa and colleagues12 found that improvements in avoidable admission rates for patients with ambulatory care–sensitive conditions were largely attributable to a shift from counted inpatient to uncounted observation hospitalizations. In other words, hospitalizations were still occurring, but were not being tallied due to outpatient (observation) classification. Zuckerman et al5 and the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC)6 concluded that readmissions improvements recognized by the HRRP were not explained by a shift to more observation hospitalizations following an index inpatient hospitalization; however, both studies included observation hospitalizations as part of 30-day rehospitalization (numerator) only, not also as part of index hospitalizations (denominator). Our study confirms the importance of including observation hospitalizations in both the index (denominator) and 30-day (numerator) rehospitalization positions to determine the full impact of observation hospitalizations on Medicare’s HRRP metrics.

Our study has limitations. We focused on nonsurgical HRRP conditions, which may have impacted our findings. Additionally, some authors have suggested including emergency department (ED) visits in rehospitalization studies.7 Although ED visits occur at hospitals, they are not hospitalizations; we excluded them as a first step. Had we included ED visits, encounters excluded from HRRP measurements would have increased, suggesting that our findings, while sizeable, are likely conservative. Additionally, we could not determine the merits or medical necessity of hospitalizations (inpatient or outpatient observation), but this is an inherent limitation in a large claims dataset like this one. Finally, we only included a single year of data in this analysis, and it is possible that additional years of data would show different trends. However, we have no reason to believe the study year to be an aberrant year; if anything, observation rates have increased since 2014,6 again pointing out that while our findings are sizable, they are likely conservative. Future research could include additional years of data to confirm even greater proportions of rehospitalizations exempt from HRRP over time due to observation hospitalizations as index and/or 30-day events.

Outpatient observation hospitalizations can occur anywhere in the hospital and are often clinically similar to inpatient hospitalizations, yet observation hospitalizations are essentially invisible under inpatient quality metrics. Requiring the HRRP to include observation hospitalizations is the most obvious solution, but this could require major regulatory and legislative change11,13—change that would fix a metric but fail to address broad policy concerns inherent in the two-tiered observation and inpatient billing distinction. Instead, CMS and Congress might consider this an opportunity to address the oxymoron of “outpatient hospitalizations” by engaging in comprehensive observation reform.

1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP). Accessed March 12, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program

2. Sabbatini AK, Wright B. Excluding observation stays from readmission rates—what quality measures are missing. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(22):2062-2065. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1800732

3. Sheehy AM, Powell WR, Kaiksow FA, et al. Thirty-day re-observation, chronic re-observation, and neighborhood disadvantage. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(12):2644-2654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.06.059

4. US Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Inspector General. Vulnerabilities remain under Medicare’s 2-midnight hospital policy. December 19, 2016. Accessed February 11, 2021. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-15-00020.asp

5. Zuckerman RB, Sheingold SH, Orav EJ, Ruhter J, Epstein AM. Readmissions, observation and the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(16):1543-1551. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1513024

6. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Mandated report: the effects of the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. In: Report to the Congress: Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System. 2018;3-31. Accessed March 17, 2021. Available at: http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/jun18_medpacreporttocongress_rev_nov2019_note_sec.pdf?sfvrsn=0

7. Wadhera RK, Yeh RW, Maddox KEJ. The Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program—time for a reboot. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(24):2289-2291. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1901225

8. National Quality Forum. Measure #1789: Hospital-wide all-cause unplanned readmission measure. Accessed January 30, 2021. https://www.qualityforum.org/ProjectDescription.aspx?projectID=73619

9. Sheehy AM, Shi F, Kind AJH. Identifying observation stays in Medicare data: policy implications of a definition. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(2):96-100. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3038

10. Powell WR, Kaiksow FA, Kind AJH, Sheehy AM. What is an observation stay? Evaluating the use of hospital observation stays in Medicare. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(7):1568-1572. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16441

11. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) Archives. Accessed February 10, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/HRRP-Archives

12. Figueroa JF, Burke LG, Zheng J, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Trends in hospitalization vs observation stay for ambulatory care-sensitive conditions. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(12): 1714-1716. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.3177

13. Public Law 111-148, Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 111th Congress. March 23, 2010. Accessed March 12, 2021.https://www.congress.gov/111/plaws/publ148/PLAW-111publ148.pdf

1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP). Accessed March 12, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program

2. Sabbatini AK, Wright B. Excluding observation stays from readmission rates—what quality measures are missing. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(22):2062-2065. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1800732

3. Sheehy AM, Powell WR, Kaiksow FA, et al. Thirty-day re-observation, chronic re-observation, and neighborhood disadvantage. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(12):2644-2654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.06.059

4. US Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Inspector General. Vulnerabilities remain under Medicare’s 2-midnight hospital policy. December 19, 2016. Accessed February 11, 2021. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-15-00020.asp

5. Zuckerman RB, Sheingold SH, Orav EJ, Ruhter J, Epstein AM. Readmissions, observation and the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(16):1543-1551. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1513024

6. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Mandated report: the effects of the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. In: Report to the Congress: Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System. 2018;3-31. Accessed March 17, 2021. Available at: http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/jun18_medpacreporttocongress_rev_nov2019_note_sec.pdf?sfvrsn=0

7. Wadhera RK, Yeh RW, Maddox KEJ. The Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program—time for a reboot. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(24):2289-2291. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1901225

8. National Quality Forum. Measure #1789: Hospital-wide all-cause unplanned readmission measure. Accessed January 30, 2021. https://www.qualityforum.org/ProjectDescription.aspx?projectID=73619

9. Sheehy AM, Shi F, Kind AJH. Identifying observation stays in Medicare data: policy implications of a definition. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(2):96-100. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3038

10. Powell WR, Kaiksow FA, Kind AJH, Sheehy AM. What is an observation stay? Evaluating the use of hospital observation stays in Medicare. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(7):1568-1572. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16441

11. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) Archives. Accessed February 10, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/HRRP-Archives

12. Figueroa JF, Burke LG, Zheng J, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Trends in hospitalization vs observation stay for ambulatory care-sensitive conditions. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(12): 1714-1716. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.3177

13. Public Law 111-148, Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 111th Congress. March 23, 2010. Accessed March 12, 2021.https://www.congress.gov/111/plaws/publ148/PLAW-111publ148.pdf

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Improving Healthcare Value: COVID-19 Emergency Regulatory Relief and Implications for Post-Acute Skilled Nursing Facility Care

Medicare beneficiary who requires skilled care in a nursing home? Better be admitted for at least 3 days in the hospital first if you want the nursing home paid for. Govt doesn’t always make sense. We’re listening to feedback.

—Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Administrator Seema Verma, @SeemaCMS, August 4, 2019, via Twitter.1

On March 13, 2020, the president of the United States declared a national health emergency, granting the secretary of the United States Department of Health & Human Services authority to grant waivers intended to ease certain Medicare and Medicaid program requirements.2 Broad waiver categories include those that may be requested by an individual institution, as well as “COVID-19 Emergency Declaration Blanket Waivers,” which automatically apply across all facilities and providers. As stated by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), waivers are intended to create “regulatory flexibilities to help healthcare providers contain the spread of 2019 Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19).” These provisions are retroactive to March 1, 2020, expire at the end of the “emergency period or 60 days from the date the waiver . . . is first published” and can be extended by the secretary.2

The issued blanket waivers remove administrative requirements in a wide range of care settings including home health, hospice, hospitals, and skilled nursing facilities (SNF), among others. The waiving of many of these administrative requirements are welcomed by providers and administrators alike in this time of national crisis. For example, relaxation of verbal order signage requirements and expanded coverage of telehealth will, almost certainly, improve accessibility, efficiency, and requisite coordination and care across settings. Emergence of these new “COVID-19” waivers also present rare and valuable opportunities to examine care improvement in areas long believed to need permanent regulatory change. Perhaps the most important of these long over-due changes is the current CMS process for determining Part A eligibility for post-acute skilled nursing facility coverage for traditional Medicare beneficiaries following an inpatient hospitalization. Under COVID-19, CMS has now granted a waiver that “authorizes the Secretary to provide for Skilled Nursing Facilities (SNF) coverage in the absence of a qualifying [three consecutive inpatient midnight] hospital stay. . . .”2 Although demand for SNF placement may shift during the pandemic, hospitals facing capacity issues will more easily be able to discharge Medicare beneficiaries ready for post-acute care.

POST-ACUTE SKILLED NURSING FACILITY COVERAGE

When Medicare was established in 1965, approximately half of Americans over age 65 did not have health insurance, and older adults were the most likely demographic to be living in poverty.3 Originally called “Hospital Insurance” or “Medicare Part A,” these “Inpatient Hospital Services” are described in Social Security statute as “items and services furnished to an inpatient of a hospital” including room and board, nursing services, pharmaceuticals, and medical and surgical services delivered in the hospital.4 In 1967, Medicare beneficiaries staying three consecutive inpatient hospital midnights were also afforded post-acute SNF coverage for up to 100 days. As expected, hospital use increased as seniors had coverage for hospital care and were also, in many cases, able to access higher quality post-hospital care.5

Over the past 50 years, two important changes have shifted Medicare beneficiary SNF coverage. First, due to efficiencies and changes in care delivery, average length of hospital stay for Americans over age 65 has shrunk from 14 days in 1965 to approximately 5 days currently.5,6 Now, fewer beneficiaries spend the necessary three or more nights in the hospital to qualify for post-acute SNF coverage. Second, and most importantly, CMS created “observation status” in the 1980s, which allowed for patients to be observed as “outpatients” in a hospital instead of as inpatients. Notably, these observation nights fall under outpatient status (Part B), and therefore do not count toward the statutory SNF coverage requirement of three inpatient midnights.

According to CMS, observation should be used so that a “decision can be made regarding whether patients will require further treatment as hospital inpatients or if they are able to be discharged from the hospital. . . . In the majority of cases, the decision can be made in less than 48 hours, usually in less than 24 hours.”7 At the time of its development, this concept fit the growing use of Emergency Department observation units, in which patients presented for an acute issue but could usually discharge home in the stated time frame.

OBSERVATION CARE

In reality, outpatient (observation) status is not synonymous with observation units. Because observation is a billing determination, not a specific type of clinical care, observation care may be delivered anywhere in a hospital—including an observation unit, a hospital ward, or even an intensive care unit (ICU). While all hospitals may deliver observation care, only about one-third of hospitals have observation units, and even hospitals with observation units deliver observation care outside of these units. Traditional Medicare beneficiaries who stay three or more nights in the hospital but cannot meet the three inpatient midnight requirement to access their SNF coverage benefits because of outpatient (observation) nights are often left vulnerable and confused, saddling them with an average of $10,503 for each uncovered SNF stay.8 As emergent evidence demonstrates striking racial, geographic, and socioeconomic-based health disparities in COVID-19, renewal of the “three-midnight rule” could have disproportionate and long-lasting ramifications for these populations in particular.9

Hospital observation stays (or observation nights) can look identical to inpatient hospital stays, as defined by the Social Security statute4; yet never count toward the three-inpatient-midnight tally. In 2014, the Office of Inspector General (OIG) found there were 633,148 hospital stays that lasted three midnights or longer but did not contain three consecutive inpatient midnights, which resulted in nonqualifying stays for purposes of SNF coverage, if that coverage was needed.10 A more recent OIG report found that Medicare was paying erroneously for some SNF stays because even CMS could not distinguish between three midnights that were all inpatient or a combination of inpatient and observation.11 Additionally, because care provided is often indistinguishable, status changes between outpatient and inpatient are common; in 2014, 40% of Medicare observation stays occurring within 30 days of an inpatient stay changed to inpatient over the course of a single hospitalization.12 Now, in the time of COVID-19, this untenable decades-long problem has the potential to be definitively addressed by a permanent removal of the three midnight requirement altogether.

PROGRESS TOWARD REFORM

Several recent signals suggest that change is supported by a diverse group of stakeholders. In their 2019 Top 25 Unimplemented Recommendations, the OIG acknowledged the similarity in observation and inpatient care, recommending that “CMS . . . analyze the potential impacts of counting time spent as an outpatient toward the 3-night requirement for skilled nursing facility (SNF) services so that beneficiaries receiving similar hospital care have similar access to these services.”13 The “Improving Access to Medicare Coverage Act of 2019,” reintroduced in the 116th Congress, would count all midnights spent in the hospital, whether those nights are inpatient or observation, toward the three midnight requirement.14 This bill has bipartisan, bicameral support, which demonstrates unified legislative interest across the political spectrum. More recently in March 2020, a federal judge in the class action lawsuit Alexander v Azar determined that Medicare beneficiaries had the right to appeal to Medicare if a physician placed a patient in inpatient status and this decision was overturned administratively by a hospital, resulting in loss of a beneficiary’s SNF coverage.15 Although now under appeal, this judicial decision signals the importance of beneficiary rights to appeal directly to CMS.

Given the mounting support for reform, it is probable that cost concerns and allocation of resources to the Part A vs Part B “buckets” remain the only barrier to permanently reforming the three-midnight inpatient stay policy. Pilot programs testing Medicare SNF waivers more than 30 years ago suggested increased cost and SNF usage.16 However, more contemporary experience from Medicare Advantage programs suggest just the opposite. Grebla et al showed there was no increased SNF use nor SNF length of stay for beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage plans that waived the three inpatient midnight requirement.17

Arguably, the current COVID-19 emergency blanket SNF waiver is not a perfect test of short- or long-term Medicare costs. First, factors such as reduced hospital elective surgeries that may typically drive post-acute SNF admissions, as well as potentially reduced SNF utilization caused by fear of COVID-19 outbreaks, may temporarily lower SNF use and associated Medicare expenditures. The existing waiver of statute is also financially constrained, stipulating that “this action does not increase overall program payments. . . .”2 Longer term, innovations in care delivery prompted by accelerated telehealth reforms may shift more post-acute care from SNFs to the home setting, changing patterns of SNF utilization altogether. Despite these limitations, this regulatory relief will still provide valuable utilization and cost information on SNF use under a system absent the three-midnight requirement.

CONCLUSION

Rarely, if ever, does a national healthcare system experience such a rapid and marked change as that seen with the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the tragic emergency circumstances prompting CMS’s blanket waivers, it provides CMS and stakeholders with a rare opportunity to evaluate potential improvements revealed by each individual aspect of COVID-19 regulatory relief. CMS has in the past argued the three-midnight SNF requirement is a statutory issue and thus not within their control, yet they have used their regulatory authority to waive this policy to facilitate efficient care in a national health crisis. This is a change that many believe is long overdue, and one that should be maintained even after COVID-19 abates. “Govt doesn’t always make sense,” as Administrator Verma wrote,1 should be a cry for government to make better sense of existing legislation and regulation. Reform of the three-midnight inpatient rule is the right place to start.

1. @SeemaCMS. #Medicare beneficiary who requires skilled care in a nursing home? Better be admitted for at least 3 days in the hospital first if you want the nursing home paid for. [Flushed face emoji] Govt doesn’t always make sense. We’re listening to feedback. #RedTapeTales #TheBoldAndTheBureaucratic. August 4, 2019. Accessed April 17, 2020. https://twitter.com/SeemaCMS/status/1158029830056828928

2. COVID-19 Emergency Declaration Blanket Waivers for Health Care Providers. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2020. Accessed April 17, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/summary-covid-19-emergency-declaration-waivers.pdf

3. Medicare & Medicaid Milestones, 1937 to 2015. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2015. Accessed April 17, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/About-CMS/Agency-Information/History/Downloads/Medicare-and-Medicaid-Milestones-1937-2015.pdf

4. Social Security Laws, 42 USC 1395x §1861 (1965). Accessed April 17, 2020. https://www.ssa.gov/OP_Home/ssact/title18/1861.htm

5. Loewenstein R. Early effects of Medicare on the health care of the aged. Social Security Bulletin. April 1971; pp 3-20, 42. Accessed April 14, 2020. https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v34n4/v34n4p3.pdf

6. Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A. Overview of Hospital Stays in the United States, 2012. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2014. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb180-Hospitalizations-United-States-2012.pdf

7. Medicare Benefits Policy Manual, Internet-Only Manuals. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Pub. 100-02, Chapter 6, § 20.6. Updated April 5, 2012. Accessed April 17, 2020. http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/Internet-Only-Manuals-IOMs.html

8. Wright S. Hospitals’ Use of Observation Stays and Short Inpatient Stays for Medicare Beneficiaries. Office of the Inspector General, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2014. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-12-00040.asp

9. Yancy CW. COVID-19 and African Americans. JAMA. Published online April 15, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6548

10. Levinson DR. Vulnerabilities Remain Under Medicare’s 2-Midnight Hospital Policy. Office of the Inspector General, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2016. Accessed April 18, 2020. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-15-00020.pdf

11. Levinson DR. CMS Improperly Paid Millions of Dollars for Skilled Nursing Facility Services When the Medicare 3-Day Inpatient Hospital Stay Requirement Was Not Met. Office of the Inspector General, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2019. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://www.oig.hhs.gov/oas/reports/region5/51600043.pdf

12. Sheehy A, Shi F, Kind A. Identifying observation stays in Medicare data: policy implications of a definition. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(2):96-100. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3038

13. Solutions to Reduce Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in HHS Programs: OIG’s Top Recommendations. Office of the Inspector General, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2019. Accessed April 18, 2020. https://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/compendium/files/compendium2019.pdf

14. Improving Access to Medicare Coverage Act of 2019, HR 1682, 116th Congress (2019). Accessed April 16, 2020. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/1682

15. Alexander v Azar, 396 F Supp 3d 242 (D CT 2019). Accessed May 26, 2020. https://casetext.com/case/alexander-v-azar-1?

16. Lipsitz L. The 3-night hospital stay and Medicare coverage for skilled nursing care. JAMA. 2013;310(14):1441-1442. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.254845

17. Grebla R, Keohane L, Lee Y, Lipsitz L, Rahman M, Trevedi A. Waiving the three-day rule: admissions and length-of-stay at hospitals and skilled nursing facilities did not increase. Health Affairs (Millwood). 2015;34(8):1324-1330. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0054

Medicare beneficiary who requires skilled care in a nursing home? Better be admitted for at least 3 days in the hospital first if you want the nursing home paid for. Govt doesn’t always make sense. We’re listening to feedback.

—Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Administrator Seema Verma, @SeemaCMS, August 4, 2019, via Twitter.1

On March 13, 2020, the president of the United States declared a national health emergency, granting the secretary of the United States Department of Health & Human Services authority to grant waivers intended to ease certain Medicare and Medicaid program requirements.2 Broad waiver categories include those that may be requested by an individual institution, as well as “COVID-19 Emergency Declaration Blanket Waivers,” which automatically apply across all facilities and providers. As stated by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), waivers are intended to create “regulatory flexibilities to help healthcare providers contain the spread of 2019 Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19).” These provisions are retroactive to March 1, 2020, expire at the end of the “emergency period or 60 days from the date the waiver . . . is first published” and can be extended by the secretary.2

The issued blanket waivers remove administrative requirements in a wide range of care settings including home health, hospice, hospitals, and skilled nursing facilities (SNF), among others. The waiving of many of these administrative requirements are welcomed by providers and administrators alike in this time of national crisis. For example, relaxation of verbal order signage requirements and expanded coverage of telehealth will, almost certainly, improve accessibility, efficiency, and requisite coordination and care across settings. Emergence of these new “COVID-19” waivers also present rare and valuable opportunities to examine care improvement in areas long believed to need permanent regulatory change. Perhaps the most important of these long over-due changes is the current CMS process for determining Part A eligibility for post-acute skilled nursing facility coverage for traditional Medicare beneficiaries following an inpatient hospitalization. Under COVID-19, CMS has now granted a waiver that “authorizes the Secretary to provide for Skilled Nursing Facilities (SNF) coverage in the absence of a qualifying [three consecutive inpatient midnight] hospital stay. . . .”2 Although demand for SNF placement may shift during the pandemic, hospitals facing capacity issues will more easily be able to discharge Medicare beneficiaries ready for post-acute care.

POST-ACUTE SKILLED NURSING FACILITY COVERAGE

When Medicare was established in 1965, approximately half of Americans over age 65 did not have health insurance, and older adults were the most likely demographic to be living in poverty.3 Originally called “Hospital Insurance” or “Medicare Part A,” these “Inpatient Hospital Services” are described in Social Security statute as “items and services furnished to an inpatient of a hospital” including room and board, nursing services, pharmaceuticals, and medical and surgical services delivered in the hospital.4 In 1967, Medicare beneficiaries staying three consecutive inpatient hospital midnights were also afforded post-acute SNF coverage for up to 100 days. As expected, hospital use increased as seniors had coverage for hospital care and were also, in many cases, able to access higher quality post-hospital care.5

Over the past 50 years, two important changes have shifted Medicare beneficiary SNF coverage. First, due to efficiencies and changes in care delivery, average length of hospital stay for Americans over age 65 has shrunk from 14 days in 1965 to approximately 5 days currently.5,6 Now, fewer beneficiaries spend the necessary three or more nights in the hospital to qualify for post-acute SNF coverage. Second, and most importantly, CMS created “observation status” in the 1980s, which allowed for patients to be observed as “outpatients” in a hospital instead of as inpatients. Notably, these observation nights fall under outpatient status (Part B), and therefore do not count toward the statutory SNF coverage requirement of three inpatient midnights.

According to CMS, observation should be used so that a “decision can be made regarding whether patients will require further treatment as hospital inpatients or if they are able to be discharged from the hospital. . . . In the majority of cases, the decision can be made in less than 48 hours, usually in less than 24 hours.”7 At the time of its development, this concept fit the growing use of Emergency Department observation units, in which patients presented for an acute issue but could usually discharge home in the stated time frame.

OBSERVATION CARE

In reality, outpatient (observation) status is not synonymous with observation units. Because observation is a billing determination, not a specific type of clinical care, observation care may be delivered anywhere in a hospital—including an observation unit, a hospital ward, or even an intensive care unit (ICU). While all hospitals may deliver observation care, only about one-third of hospitals have observation units, and even hospitals with observation units deliver observation care outside of these units. Traditional Medicare beneficiaries who stay three or more nights in the hospital but cannot meet the three inpatient midnight requirement to access their SNF coverage benefits because of outpatient (observation) nights are often left vulnerable and confused, saddling them with an average of $10,503 for each uncovered SNF stay.8 As emergent evidence demonstrates striking racial, geographic, and socioeconomic-based health disparities in COVID-19, renewal of the “three-midnight rule” could have disproportionate and long-lasting ramifications for these populations in particular.9

Hospital observation stays (or observation nights) can look identical to inpatient hospital stays, as defined by the Social Security statute4; yet never count toward the three-inpatient-midnight tally. In 2014, the Office of Inspector General (OIG) found there were 633,148 hospital stays that lasted three midnights or longer but did not contain three consecutive inpatient midnights, which resulted in nonqualifying stays for purposes of SNF coverage, if that coverage was needed.10 A more recent OIG report found that Medicare was paying erroneously for some SNF stays because even CMS could not distinguish between three midnights that were all inpatient or a combination of inpatient and observation.11 Additionally, because care provided is often indistinguishable, status changes between outpatient and inpatient are common; in 2014, 40% of Medicare observation stays occurring within 30 days of an inpatient stay changed to inpatient over the course of a single hospitalization.12 Now, in the time of COVID-19, this untenable decades-long problem has the potential to be definitively addressed by a permanent removal of the three midnight requirement altogether.

PROGRESS TOWARD REFORM

Several recent signals suggest that change is supported by a diverse group of stakeholders. In their 2019 Top 25 Unimplemented Recommendations, the OIG acknowledged the similarity in observation and inpatient care, recommending that “CMS . . . analyze the potential impacts of counting time spent as an outpatient toward the 3-night requirement for skilled nursing facility (SNF) services so that beneficiaries receiving similar hospital care have similar access to these services.”13 The “Improving Access to Medicare Coverage Act of 2019,” reintroduced in the 116th Congress, would count all midnights spent in the hospital, whether those nights are inpatient or observation, toward the three midnight requirement.14 This bill has bipartisan, bicameral support, which demonstrates unified legislative interest across the political spectrum. More recently in March 2020, a federal judge in the class action lawsuit Alexander v Azar determined that Medicare beneficiaries had the right to appeal to Medicare if a physician placed a patient in inpatient status and this decision was overturned administratively by a hospital, resulting in loss of a beneficiary’s SNF coverage.15 Although now under appeal, this judicial decision signals the importance of beneficiary rights to appeal directly to CMS.

Given the mounting support for reform, it is probable that cost concerns and allocation of resources to the Part A vs Part B “buckets” remain the only barrier to permanently reforming the three-midnight inpatient stay policy. Pilot programs testing Medicare SNF waivers more than 30 years ago suggested increased cost and SNF usage.16 However, more contemporary experience from Medicare Advantage programs suggest just the opposite. Grebla et al showed there was no increased SNF use nor SNF length of stay for beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage plans that waived the three inpatient midnight requirement.17

Arguably, the current COVID-19 emergency blanket SNF waiver is not a perfect test of short- or long-term Medicare costs. First, factors such as reduced hospital elective surgeries that may typically drive post-acute SNF admissions, as well as potentially reduced SNF utilization caused by fear of COVID-19 outbreaks, may temporarily lower SNF use and associated Medicare expenditures. The existing waiver of statute is also financially constrained, stipulating that “this action does not increase overall program payments. . . .”2 Longer term, innovations in care delivery prompted by accelerated telehealth reforms may shift more post-acute care from SNFs to the home setting, changing patterns of SNF utilization altogether. Despite these limitations, this regulatory relief will still provide valuable utilization and cost information on SNF use under a system absent the three-midnight requirement.

CONCLUSION

Rarely, if ever, does a national healthcare system experience such a rapid and marked change as that seen with the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the tragic emergency circumstances prompting CMS’s blanket waivers, it provides CMS and stakeholders with a rare opportunity to evaluate potential improvements revealed by each individual aspect of COVID-19 regulatory relief. CMS has in the past argued the three-midnight SNF requirement is a statutory issue and thus not within their control, yet they have used their regulatory authority to waive this policy to facilitate efficient care in a national health crisis. This is a change that many believe is long overdue, and one that should be maintained even after COVID-19 abates. “Govt doesn’t always make sense,” as Administrator Verma wrote,1 should be a cry for government to make better sense of existing legislation and regulation. Reform of the three-midnight inpatient rule is the right place to start.

Medicare beneficiary who requires skilled care in a nursing home? Better be admitted for at least 3 days in the hospital first if you want the nursing home paid for. Govt doesn’t always make sense. We’re listening to feedback.

—Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Administrator Seema Verma, @SeemaCMS, August 4, 2019, via Twitter.1

On March 13, 2020, the president of the United States declared a national health emergency, granting the secretary of the United States Department of Health & Human Services authority to grant waivers intended to ease certain Medicare and Medicaid program requirements.2 Broad waiver categories include those that may be requested by an individual institution, as well as “COVID-19 Emergency Declaration Blanket Waivers,” which automatically apply across all facilities and providers. As stated by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), waivers are intended to create “regulatory flexibilities to help healthcare providers contain the spread of 2019 Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19).” These provisions are retroactive to March 1, 2020, expire at the end of the “emergency period or 60 days from the date the waiver . . . is first published” and can be extended by the secretary.2

The issued blanket waivers remove administrative requirements in a wide range of care settings including home health, hospice, hospitals, and skilled nursing facilities (SNF), among others. The waiving of many of these administrative requirements are welcomed by providers and administrators alike in this time of national crisis. For example, relaxation of verbal order signage requirements and expanded coverage of telehealth will, almost certainly, improve accessibility, efficiency, and requisite coordination and care across settings. Emergence of these new “COVID-19” waivers also present rare and valuable opportunities to examine care improvement in areas long believed to need permanent regulatory change. Perhaps the most important of these long over-due changes is the current CMS process for determining Part A eligibility for post-acute skilled nursing facility coverage for traditional Medicare beneficiaries following an inpatient hospitalization. Under COVID-19, CMS has now granted a waiver that “authorizes the Secretary to provide for Skilled Nursing Facilities (SNF) coverage in the absence of a qualifying [three consecutive inpatient midnight] hospital stay. . . .”2 Although demand for SNF placement may shift during the pandemic, hospitals facing capacity issues will more easily be able to discharge Medicare beneficiaries ready for post-acute care.

POST-ACUTE SKILLED NURSING FACILITY COVERAGE

When Medicare was established in 1965, approximately half of Americans over age 65 did not have health insurance, and older adults were the most likely demographic to be living in poverty.3 Originally called “Hospital Insurance” or “Medicare Part A,” these “Inpatient Hospital Services” are described in Social Security statute as “items and services furnished to an inpatient of a hospital” including room and board, nursing services, pharmaceuticals, and medical and surgical services delivered in the hospital.4 In 1967, Medicare beneficiaries staying three consecutive inpatient hospital midnights were also afforded post-acute SNF coverage for up to 100 days. As expected, hospital use increased as seniors had coverage for hospital care and were also, in many cases, able to access higher quality post-hospital care.5

Over the past 50 years, two important changes have shifted Medicare beneficiary SNF coverage. First, due to efficiencies and changes in care delivery, average length of hospital stay for Americans over age 65 has shrunk from 14 days in 1965 to approximately 5 days currently.5,6 Now, fewer beneficiaries spend the necessary three or more nights in the hospital to qualify for post-acute SNF coverage. Second, and most importantly, CMS created “observation status” in the 1980s, which allowed for patients to be observed as “outpatients” in a hospital instead of as inpatients. Notably, these observation nights fall under outpatient status (Part B), and therefore do not count toward the statutory SNF coverage requirement of three inpatient midnights.

According to CMS, observation should be used so that a “decision can be made regarding whether patients will require further treatment as hospital inpatients or if they are able to be discharged from the hospital. . . . In the majority of cases, the decision can be made in less than 48 hours, usually in less than 24 hours.”7 At the time of its development, this concept fit the growing use of Emergency Department observation units, in which patients presented for an acute issue but could usually discharge home in the stated time frame.

OBSERVATION CARE

In reality, outpatient (observation) status is not synonymous with observation units. Because observation is a billing determination, not a specific type of clinical care, observation care may be delivered anywhere in a hospital—including an observation unit, a hospital ward, or even an intensive care unit (ICU). While all hospitals may deliver observation care, only about one-third of hospitals have observation units, and even hospitals with observation units deliver observation care outside of these units. Traditional Medicare beneficiaries who stay three or more nights in the hospital but cannot meet the three inpatient midnight requirement to access their SNF coverage benefits because of outpatient (observation) nights are often left vulnerable and confused, saddling them with an average of $10,503 for each uncovered SNF stay.8 As emergent evidence demonstrates striking racial, geographic, and socioeconomic-based health disparities in COVID-19, renewal of the “three-midnight rule” could have disproportionate and long-lasting ramifications for these populations in particular.9

Hospital observation stays (or observation nights) can look identical to inpatient hospital stays, as defined by the Social Security statute4; yet never count toward the three-inpatient-midnight tally. In 2014, the Office of Inspector General (OIG) found there were 633,148 hospital stays that lasted three midnights or longer but did not contain three consecutive inpatient midnights, which resulted in nonqualifying stays for purposes of SNF coverage, if that coverage was needed.10 A more recent OIG report found that Medicare was paying erroneously for some SNF stays because even CMS could not distinguish between three midnights that were all inpatient or a combination of inpatient and observation.11 Additionally, because care provided is often indistinguishable, status changes between outpatient and inpatient are common; in 2014, 40% of Medicare observation stays occurring within 30 days of an inpatient stay changed to inpatient over the course of a single hospitalization.12 Now, in the time of COVID-19, this untenable decades-long problem has the potential to be definitively addressed by a permanent removal of the three midnight requirement altogether.

PROGRESS TOWARD REFORM

Several recent signals suggest that change is supported by a diverse group of stakeholders. In their 2019 Top 25 Unimplemented Recommendations, the OIG acknowledged the similarity in observation and inpatient care, recommending that “CMS . . . analyze the potential impacts of counting time spent as an outpatient toward the 3-night requirement for skilled nursing facility (SNF) services so that beneficiaries receiving similar hospital care have similar access to these services.”13 The “Improving Access to Medicare Coverage Act of 2019,” reintroduced in the 116th Congress, would count all midnights spent in the hospital, whether those nights are inpatient or observation, toward the three midnight requirement.14 This bill has bipartisan, bicameral support, which demonstrates unified legislative interest across the political spectrum. More recently in March 2020, a federal judge in the class action lawsuit Alexander v Azar determined that Medicare beneficiaries had the right to appeal to Medicare if a physician placed a patient in inpatient status and this decision was overturned administratively by a hospital, resulting in loss of a beneficiary’s SNF coverage.15 Although now under appeal, this judicial decision signals the importance of beneficiary rights to appeal directly to CMS.

Given the mounting support for reform, it is probable that cost concerns and allocation of resources to the Part A vs Part B “buckets” remain the only barrier to permanently reforming the three-midnight inpatient stay policy. Pilot programs testing Medicare SNF waivers more than 30 years ago suggested increased cost and SNF usage.16 However, more contemporary experience from Medicare Advantage programs suggest just the opposite. Grebla et al showed there was no increased SNF use nor SNF length of stay for beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage plans that waived the three inpatient midnight requirement.17

Arguably, the current COVID-19 emergency blanket SNF waiver is not a perfect test of short- or long-term Medicare costs. First, factors such as reduced hospital elective surgeries that may typically drive post-acute SNF admissions, as well as potentially reduced SNF utilization caused by fear of COVID-19 outbreaks, may temporarily lower SNF use and associated Medicare expenditures. The existing waiver of statute is also financially constrained, stipulating that “this action does not increase overall program payments. . . .”2 Longer term, innovations in care delivery prompted by accelerated telehealth reforms may shift more post-acute care from SNFs to the home setting, changing patterns of SNF utilization altogether. Despite these limitations, this regulatory relief will still provide valuable utilization and cost information on SNF use under a system absent the three-midnight requirement.

CONCLUSION

Rarely, if ever, does a national healthcare system experience such a rapid and marked change as that seen with the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the tragic emergency circumstances prompting CMS’s blanket waivers, it provides CMS and stakeholders with a rare opportunity to evaluate potential improvements revealed by each individual aspect of COVID-19 regulatory relief. CMS has in the past argued the three-midnight SNF requirement is a statutory issue and thus not within their control, yet they have used their regulatory authority to waive this policy to facilitate efficient care in a national health crisis. This is a change that many believe is long overdue, and one that should be maintained even after COVID-19 abates. “Govt doesn’t always make sense,” as Administrator Verma wrote,1 should be a cry for government to make better sense of existing legislation and regulation. Reform of the three-midnight inpatient rule is the right place to start.

1. @SeemaCMS. #Medicare beneficiary who requires skilled care in a nursing home? Better be admitted for at least 3 days in the hospital first if you want the nursing home paid for. [Flushed face emoji] Govt doesn’t always make sense. We’re listening to feedback. #RedTapeTales #TheBoldAndTheBureaucratic. August 4, 2019. Accessed April 17, 2020. https://twitter.com/SeemaCMS/status/1158029830056828928

2. COVID-19 Emergency Declaration Blanket Waivers for Health Care Providers. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2020. Accessed April 17, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/summary-covid-19-emergency-declaration-waivers.pdf

3. Medicare & Medicaid Milestones, 1937 to 2015. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2015. Accessed April 17, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/About-CMS/Agency-Information/History/Downloads/Medicare-and-Medicaid-Milestones-1937-2015.pdf

4. Social Security Laws, 42 USC 1395x §1861 (1965). Accessed April 17, 2020. https://www.ssa.gov/OP_Home/ssact/title18/1861.htm

5. Loewenstein R. Early effects of Medicare on the health care of the aged. Social Security Bulletin. April 1971; pp 3-20, 42. Accessed April 14, 2020. https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v34n4/v34n4p3.pdf

6. Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A. Overview of Hospital Stays in the United States, 2012. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2014. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb180-Hospitalizations-United-States-2012.pdf

7. Medicare Benefits Policy Manual, Internet-Only Manuals. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Pub. 100-02, Chapter 6, § 20.6. Updated April 5, 2012. Accessed April 17, 2020. http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/Internet-Only-Manuals-IOMs.html

8. Wright S. Hospitals’ Use of Observation Stays and Short Inpatient Stays for Medicare Beneficiaries. Office of the Inspector General, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2014. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-12-00040.asp

9. Yancy CW. COVID-19 and African Americans. JAMA. Published online April 15, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6548

10. Levinson DR. Vulnerabilities Remain Under Medicare’s 2-Midnight Hospital Policy. Office of the Inspector General, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2016. Accessed April 18, 2020. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-15-00020.pdf

11. Levinson DR. CMS Improperly Paid Millions of Dollars for Skilled Nursing Facility Services When the Medicare 3-Day Inpatient Hospital Stay Requirement Was Not Met. Office of the Inspector General, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2019. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://www.oig.hhs.gov/oas/reports/region5/51600043.pdf

12. Sheehy A, Shi F, Kind A. Identifying observation stays in Medicare data: policy implications of a definition. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(2):96-100. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3038

13. Solutions to Reduce Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in HHS Programs: OIG’s Top Recommendations. Office of the Inspector General, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2019. Accessed April 18, 2020. https://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/compendium/files/compendium2019.pdf

14. Improving Access to Medicare Coverage Act of 2019, HR 1682, 116th Congress (2019). Accessed April 16, 2020. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/1682

15. Alexander v Azar, 396 F Supp 3d 242 (D CT 2019). Accessed May 26, 2020. https://casetext.com/case/alexander-v-azar-1?

16. Lipsitz L. The 3-night hospital stay and Medicare coverage for skilled nursing care. JAMA. 2013;310(14):1441-1442. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.254845

17. Grebla R, Keohane L, Lee Y, Lipsitz L, Rahman M, Trevedi A. Waiving the three-day rule: admissions and length-of-stay at hospitals and skilled nursing facilities did not increase. Health Affairs (Millwood). 2015;34(8):1324-1330. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0054

1. @SeemaCMS. #Medicare beneficiary who requires skilled care in a nursing home? Better be admitted for at least 3 days in the hospital first if you want the nursing home paid for. [Flushed face emoji] Govt doesn’t always make sense. We’re listening to feedback. #RedTapeTales #TheBoldAndTheBureaucratic. August 4, 2019. Accessed April 17, 2020. https://twitter.com/SeemaCMS/status/1158029830056828928

2. COVID-19 Emergency Declaration Blanket Waivers for Health Care Providers. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2020. Accessed April 17, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/summary-covid-19-emergency-declaration-waivers.pdf

3. Medicare & Medicaid Milestones, 1937 to 2015. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2015. Accessed April 17, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/About-CMS/Agency-Information/History/Downloads/Medicare-and-Medicaid-Milestones-1937-2015.pdf

4. Social Security Laws, 42 USC 1395x §1861 (1965). Accessed April 17, 2020. https://www.ssa.gov/OP_Home/ssact/title18/1861.htm

5. Loewenstein R. Early effects of Medicare on the health care of the aged. Social Security Bulletin. April 1971; pp 3-20, 42. Accessed April 14, 2020. https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v34n4/v34n4p3.pdf

6. Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A. Overview of Hospital Stays in the United States, 2012. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2014. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb180-Hospitalizations-United-States-2012.pdf

7. Medicare Benefits Policy Manual, Internet-Only Manuals. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Pub. 100-02, Chapter 6, § 20.6. Updated April 5, 2012. Accessed April 17, 2020. http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/Internet-Only-Manuals-IOMs.html

8. Wright S. Hospitals’ Use of Observation Stays and Short Inpatient Stays for Medicare Beneficiaries. Office of the Inspector General, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2014. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-12-00040.asp

9. Yancy CW. COVID-19 and African Americans. JAMA. Published online April 15, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6548

10. Levinson DR. Vulnerabilities Remain Under Medicare’s 2-Midnight Hospital Policy. Office of the Inspector General, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2016. Accessed April 18, 2020. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-15-00020.pdf

11. Levinson DR. CMS Improperly Paid Millions of Dollars for Skilled Nursing Facility Services When the Medicare 3-Day Inpatient Hospital Stay Requirement Was Not Met. Office of the Inspector General, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2019. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://www.oig.hhs.gov/oas/reports/region5/51600043.pdf

12. Sheehy A, Shi F, Kind A. Identifying observation stays in Medicare data: policy implications of a definition. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(2):96-100. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3038

13. Solutions to Reduce Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in HHS Programs: OIG’s Top Recommendations. Office of the Inspector General, US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2019. Accessed April 18, 2020. https://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/compendium/files/compendium2019.pdf

14. Improving Access to Medicare Coverage Act of 2019, HR 1682, 116th Congress (2019). Accessed April 16, 2020. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/1682

15. Alexander v Azar, 396 F Supp 3d 242 (D CT 2019). Accessed May 26, 2020. https://casetext.com/case/alexander-v-azar-1?

16. Lipsitz L. The 3-night hospital stay and Medicare coverage for skilled nursing care. JAMA. 2013;310(14):1441-1442. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.254845

17. Grebla R, Keohane L, Lee Y, Lipsitz L, Rahman M, Trevedi A. Waiving the three-day rule: admissions and length-of-stay at hospitals and skilled nursing facilities did not increase. Health Affairs (Millwood). 2015;34(8):1324-1330. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0054

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine