User login

Non–Housestaff Medicine Services in Academic Centers

Many academic medical centers (AMCs) have developed nonhousestaff services to provide clinical care once provided by physicians‐in‐training. These services, often staffed by hospitalists and/or midlevel providers, have experienced tremendous growth in the past few years, yet very little exists in the literature about their development, structure, efficacy, or impact on hospitals, patients, and hospital medicine programs. The primary forces driving this growth include Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) resident duty hour restrictions,1 growth of the hospitalist movement,2 and the emphasis on simultaneously improving financial performance and quality of care in AMCs.3

Resident Duty Hour Restrictions

In 2003, the ACGME mandated restrictions on resident work hours, limiting trainees to 80 hours per week.1 Many training programs struggled with how to provide important clinical services while complying with the new restrictionscreating numerous models that bridged care between different shifts of residents.45 Implementation of day floats (a dedicated resident who rounds with the postcall team), night floats (a dedicated overnight resident who admits and cross‐covers patients), or some variation of both was common.6 No guidelines accompanied the ACGME mandate, leaving institutions to independently structure their programs without a known best practice.

Subsequent literature carefully addressed how the duty hour restrictions affect residents' lives and education but failed to discuss models for providing care.711 Training programs began to institute necessary changes but in doing so, created greater patient discontinuity and increased handoffs between residents, elevating the potential for adverse patient outcomes.12 Recent large‐scale studies indicate that inpatient care is the same or improved since adoption of the duty hour restrictions,1316 but controversy continues, with several editorials debating the issue.1719

Because increasing the volume of patients on housestaff services was not a viable option,20 many AMCs created nonhousestaff services and hired midlevel providers (nurse practitioners and physician assistants) to offset resident workloads and comply with the new restrictions. However, this strategy represented a very expensive alternative.21 Moreover, the current 80‐hour work limits may be revised downward, particularly given the lower restrictions in other countries,22 and this will further drive the demand for nonhousestaff services. Hospitalists, with their documented impact on efficiency and return on investment,23 represent a solution to fill these needs and have quickly become the predominant approach at AMCs.

The Hospitalist Movement

Since the term hospitalist was first coined in 1996,24 the remarkable growth of the number of practicing hospitalists emphasizes how first community hospitals and now AMCs have embraced this approach.25 With more than 20,000 nationwide and projections that the field will grow to 30,000 by 2010,26 hospitalists are becoming the primary providers for in‐patients.2 This growth was further catalyzed when widely expressed concerns about safety and quality became public,2728 and hospitalists incorporated patient safety and quality improvement activities into their efforts.3 The confluence of these factors also prompted emergence of hospital medicine programs at AMCs, a growth that came with anticipated dangers.29 Reflecting the recognition that hospital medicine is becoming a separate specialty30 and is integral to the functioning of an AMC, institutions now operate dedicated divisions of hospital medicine.

AMCs and Hospital Performance

AMCs operate 3 related enterprises: a medical school that trains future physicians, a research arena that promotes basic and clinical investigation, and health care services that often encompass both hospitals and clinics. The financial viability of AMCs has always been a topic of debate, largely because of the different missions they pursue and the financial means by which they survive.3133 Over the past decade, cuts in Medicare reimbursement, challenges in balancing bed availability with occupancy rates, and a growing emphasis on cost reduction have created a more competitive health care environment, but without the predicted demise of AMCs.34 Because education and research generally fail to bolster the bottom line, AMCs have focused on optimizing clinical services to promote financial viability.

Hospitalists are uniquely positioned to help this bottom line, just as they do at community hospitals. Their involvement in patient care may produce reductions in length of stay, greater efficiency in discharge planning, and significant cost savings.3537 Hospitalists may also improve throughput in emergency departments and decrease wait times, leading to more efficient bed utilization.38 This leads to a potential for greater hospital revenue by increasing both the number of admissions, particularly surgical cases, and staffed inpatient beds, the latter a premium, as AMCs continue to expand their bed capacity almost annually. Finally, hospitalists may serve as change agents in improving the quality and safety of care delivered, an increasingly important metric given the desire for and expansion of publicly reported measures.

From a financial standpoint, Medicare support to AMCs for training residents now subsidizes fewer clinical care hours. Hospitalist‐driven nonhousestaff services will continue to fulfill a need created by this marked change in residency training. The tension of who pays for nonhousestaff servicesincreased federal support, financial backing from AMCs, or academic department fundsposes an ongoing struggle. In fact, this may be the most important issue currently debated among hospital administrators and department chairs. Regardless, AMCs continue to view hospitalists as a mechanism (or even solution) to maintaining their financial bottom line through improving care delivery systems, adhering to resident work hour restrictions, leading quality and safety improvement initiatives, and improving clinical patient outcomes.

MODELS FOR NONHOUSESTAFF MEDICAL SERVICES

For AMCs developing nonhousestaff services, the process begins by addressing a series of important questions (Table 1). How these questions are answered is often driven by local factors such as the vision of local leadership and the availability of important resources. Nonetheless, it is important for hospitals to share their experiences because best practices remain unclear. Table 2 provides a tabular snapshot of nonhousestaff medicine services at 5 AMCs to highlight similarities and differences. Data in the table were compiled by having a representative from each AMC report the different attributes, which reflects each program as of July 2007. Table 2 provides no data on the quality or efficiency of housestaff versus nonhousestaff services, though this type of investigation is underway and will be critical in future planning.3940

| Questions | Potential options |

|---|---|

| Who will provide care on nonhousestaff services? | Physicians seeking a 1‐year position |

| Physicians committed to a purely clinical career | |

| Physicians committed to an academic career in hospital medicine | |

| Will hospitalists share nonhousestaff service time, or will there be dedicated nonhousestaff hospitalists? | Hybrid positions |

| Dedicated nonhousestaff hospitalists | |

| Use of PGY‐4s1‐year positions (often individuals planning a fellowship) | |

| How should staffing be organized? | Hospitalist‐only services |

| Use of midlevel providers | |

| Will there be 24‐7 coverage, and if so, how will nights be staffed? | Dedicated nocturnists |

| Shared among daytime hospitalists | |

| Midlevel providers | |

| Moonlighters (fellows or residents) | |

| What type of schedule will provide blocks of clinical time to ensure continuity of care but also ensure adequate nonclinical time to prevent physician burnout and turnover? | 7 on/7 off sequences |

| 45 day sequences | |

| Longer shifts with fewer shifts per month | |

| Shorter shifts with more shifts per month | |

| Where will patients on a nonhousestaff service receive care? | Geographically designed serviced |

| ○ Different floor | |

| ○ Different hospital | |

| Mixed among housestaff service | |

| What patient population will be cared for on the nonhousestaff service? | Same as on housestaff service |

| Based on bed availability if nonhousestaff service is geographic (a unit) | |

| Based on triage guidelines (lower acuity, observation patients, specific diagnoses) | |

| What volume of patients will be cared for on the nonhousestaff service? | Fixed census cap based on staffing |

| Flexible census depending on activity of housestaff service (above their cap) | |

| Will compensation for providing nonhousestaff services differ from that on housestaff services? | Higher base salary |

| Incentives tied to nonhousestaff time | |

| Different incentive structures |

| Attributes | BWH | Emory | University of Michigan | Northwestern | UCSF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Description of staffing model | Mon.‐Sun.: 1 daytime Hospitalist | Mon.‐Sun.: 4 daytime hospitalists, 2 swing shift admitters | Weekdays: 7 daytime hospitalists, 1 swing shift hospitalist | Mon.‐Sun.: 8 daytime hospitalists, 1 triage hospitalist | Weekdays: 2 daytime hospitalists, 1 swing shift hospitalist |

| Nights: 1 MD | Nights: 1 MDs | Weekends: 7 daytime hospitalists | Nights: 2 MDs | Weekends: 2 daytime hospitalists | |

| Nights: 2 MDs | Nights: 1 MD | ||||

| Location of service | In same university hospital | In same university hospital | In same university hospital | In same university hospital | Physically separate hospital affiliate (UCSF Medical Center at Mount Zion) |

| Nonhousestaff FTEs/total hospitalist group | 3/15 | 10/14 | 20/30 | 25/34 | 6/36 |

| What hospitalists provide care on nonhous estaff services? | Core of 3 hospitalists (also do month on housestaff service) | Hospitalist group shares nonhousestaff services | Core of 14 FTEs dedicated to nonhousestaff services | Hospitalist group shares nonhousestaff services | Core of 6 Mount Zionbased hospitalists (also spend 23 months on housestaff service at university hospital) |

| Other 6 FTEs consist of 10 faculty with mixed roles | |||||

| Age of service | 2 years | 4 years | 3 years | 5 years | 3 years |

| How patients get assigned to non‐housestaff service? | 1. Only ED admissions with no transfers from ICU or other services | Assigned by rotation | 1. Alternating admissions with housestaff services during afternoon | 1. Alternating admissions with housestaff services during day | 1. Lower‐acuity admissions from ED |

| 2. Admit whenever bed open on service (geographic) | 2. Observation cases triaged directly to service | 2. Lower‐acuity patients and direct admissions | 2. Lower‐acuity admissions from clinics | ||

| 3. Once housestaff cap, all subsequent admits until midnight to nonhousestaff service | 3. Nonhousestaff service admits all patients once resident caps reached | 3. Transfers from housestaff service no longer requiring tertiary services (or with complex discharge planning) | |||

| Average daily census of nonhousestaff service | 12 | 56 | 70 (75 cap) | 8595 | 2026 |

| Number of shifts per month/shift duration | 15/1012 hours | 15/12 hours | 1517 (depending on number of nights covered)/812 hours (swing = 8 hours, day = 1012 hours, night = 12 hours) | 20/1012 hours | 1617/1012 hours |

| Shift sequences | 710 days consecutive | Variable | 67 days consecutive followed by 1 night for those who cover nights | 7 days consecutive | 4‐ to 6‐day variable sequences |

| Total clinical days worked/year | 168 | 182.5 | 185202 (depending on number of nights covered) | 212 | 196 |

| Weekend clinical time | 50% of weekends | 50% of weekends | 50% of weekends | 50% of weekends | 50% of weekends |

| Night coverage/by whom? | Yes/exclusively moonlighters | Yes/shared (50% covered by 1 dedicated nocturnist) | Yes/66% of nights staffed by dedicated nocturnists with remainder shared | Yes/exclusively by six 1‐year nocturnists | Yes/exclusively by moonlighters |

| Presence of midlevel providers | Yes 6 FTE PAs Mon.‐Sun. | No | Yes 8 FTE PAs weekdays | No | No |

| Presence of dedicated case manager | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Presence of medical students for patient care | No | No | Yes, 4th‐year subinterns or students on elective rotation | No | No |

| Compensation model | Salary + weekend bonus beyond 10 | Salary + incentive | Base + shift‐based incentive + quality incentive | Salary + incentive | Salary |

| Pay differential compared to housestaff service compensation | 10% Higher because of weekend bonus | None | About 20% higher base compensation; loan forgiveness program tied to nonhousestaff time | None | About 20% higher compensation |

| Hospital financial support | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Table 2 does illustrate several important considerations in structuring nonhousestaff services. For example, if a nonhousestaff service operates at a different physical location, careful triage of patients is necessary. Resources, including the availability of subspecialty and surgical consultants, may differ, and thus patient complexity and acuity may dictate whether a patient gets admitted to the nonhousestaff service. These triage factors were a major challenge in the design of UCSF's nonhousestaff service. The other nonhousestaff services handle overflow admissions after the housestaff service reaches a census or admission cap; transfers between services rarely occur, and resources are similar.

Other observations include that hospitalists work a similar number of hours each year and cover 50% of weekends but with differing shift lengths and sequences. Each service also provides night coverage but only Emory, the University of Michigan, and Northwestern utilize dedicated nocturnists. The University of Michigan and Brigham & Women's Hospital are the only sites that employ midlevel providers who work closely with hospitalists. In terms of group structure, Northwestern's hospitalists are the most integrated, with each hospitalist sharing equal responsibility for nonhousestaff coverage. In contrast, the other programs use selected hospitalists or a dedicated core of hospitalists to provide nonhousestaff services. Compensation models also vary, with certain groups salaried and others having incentive systems, although all receive hospital‐based funding support. Hospital‐based funding support ranges from 40% to 100% of total program costs across sites, creating similar variance in a given program's deficit risk. Finally, most programs do compensate nonhousestaff services at higher rates.

All the decisions captured in Table 2 have implications for costs, recruitment, and service structure. Furthermore, the striking variations demonstrate how different academic hospitalist positions can occur both within a hospital medicine group and across institutions. Of note, Table 2 only characterizes nonhousestaff medicine services, not the growing number of comanagement (eg, orthopedics, neurosurgery, or hematology/oncology) and other clinical services (eg, observation unit or preoperative medicine clinic) also staffed by hospitalists at AMCs.

CHALLENGES

Hospital medicine programs and AMCs face several challenges in building non‐housestaff services, but these will likely become less daunting as programs learn from their own experiences, from those of colleagues at other institutions, and from future investigations of these care models. We highlight a few issues below that warrant important consideration.

The Equities of the System

Prior to developing nonhousestaff services, our academic hospitalist programs scheduled teaching service time in month or half‐month blocks, balancing holidays and weekends. Equity in scheduling became a function of required clinical time, sources of non‐clinical funding (eg, grants, educational or administrative roles), and expectations for scholarship, attributes typical of most subspecialty academic divisions. Given the differing clinical missions that have stimulated academic hospital medicine programs to form, concerns of scheduling equity have grown, posing challenges not experienced in other divisions.

Institutions that choose to divide housestaff and nonhousestaff duties among distinct groups of hospitalists create the potential for a 2‐tiered system, one in which those with housestaff roles are more valued and respected by the institution. Hospitalists working on nonhousestaff services admit patients, write orders, and field direct patient calls, a role rarely undertaken by subspecialty attendings or hospitalists on housestaff services. Our collective experiences provide evidence of the danger of this second‐class‐citizen status, one that requires attention to ensure job satisfaction, retention, and necessary career development.

Institutions have accentuated the second‐class‐citizen concern by staffing nonhousestaff roles with 1‐year hospitalistsPGY‐4s. Most of these hires in our institutions are individuals just out of residency and intent on pursuing a fellowship. We speculate that they enjoy the comforts of the AMC where they often trained and accept purely nonhousestaff positions because of what they view as an appealing work schedule and salary. Although this approach addresses the growing need for hospitalists on nonhousestaff services in the short term, these positions must remain attractive enough (both financially and professionally) to encourage residency graduates to pursue an academic hospitalist career instead of a 1‐year position as a transition to fellowship. Otherwise, the approach conveys a message that relatively inexperienced physicians are good enough to be hospitalists.

Developing a cadre of clinically focused hospitalists who provide outstanding patient care and also garner respect as successful academicians is a difficult task. Although 1 group in our sample (Northwestern) shares nonhousestaff responsibilities equally, others may find this impractical, particularly where faculty members were hired before nonhousestaff services were established. Redefining such clinical positions several years into a career may be challenging, as it forces faculty members into roles they didn't sign up for or grandfathers them out of such roles, adding to the risk of a 2‐tiered system. Alternatively, groups may focus on building academic activities into nonhousestaff services, including medical student teaching, quality improvement, or clinical research activities. In this article, we deliberately classified these services as nonhousestaff rather than non‐teaching because the latter fails to acknowledge that these hospitalists often serve as teachers (eg, housestaff conferences, supervision of midlevel providers, and/or rotating medical students)an important if not symbolic distinction. It is imperative that planning for nonhousestaff services balance the larger academic mission of hospital medicine groups with creating equitable, valued, and sustainable job descriptions.

Defining the Patient Mix

Developing an optimal patient mix on nonhousestaff services also carries important implications. For services that work in parallel with the housestaff service and simply take extra patients above the resident cap, this concern may be less significant. However, other nonhousestaff services have been structured to care for lower‐acuity patients (eg, cellulitis, asthma, pneumonia) or select patient populations (eg, sickle cell or inflammatory bowel disease). This distribution system potentially changes the educational experience on the housestaff servicedecreasing the bread‐and‐butter admissionsbut also may affect the job satisfaction of hospitalists and midlevel providers on nonhousestaff services. Building triage criteria, working with emergency department leadership, and avoiding patients being turfed between different services is critical. We strongly recommend a regular process to review admissions to each service and determine when the triage process requires further calibration.

Recruitment and Retention

Traditionally, graduates of residency or fellowship training programs chose academic positions because of an interest in teaching, a desire for scholarship, or a commitment to research. Those interested in primarily clinical roles typically pursued positions in nonacademic settings. The development of nonhousestaff services challenges this paradigm because the objective for academic hospitalist leadership now becomes recruiting pure clinicians as well as academicians. These might be the same individual, a hospitalist who provides both housestaff and nonhousestaff services, or 2 different individuals if the nonhousestaff service is covered by dedicated hospitalists. In addition, with the current promotion structure in academia, a purely clinical position may be less attractive, as it provides fewer opportunities for advancement.

Therefore, recruitment and retention of academic hospitalists will require job descriptions that provide dedicated teaching opportunities, time for participation in quality and safety improvement projects, or pursuit of a scholarly interest in non‐clinical timethe diastole of an academic hospitalist.41 Hospital medicine leadership will also need to better distinguish off‐time from non‐clinical time, as many young hospitalists struggle to balance professional and personal commitmentsa recipe for burnout.42 Regardless of how clinical responsibilities differ between 2 hospitalists, providing them with similar academic resources is what will distinguish their positions from that in the community. Furthermore, many groups have chosen to pay faculty a premium for their nonhousestaff roles or to use specific recruitment incentives such as educational loan forgiveness programs.

With the expected growth of nonhousestaff services and surgical comanagement, hospital medicine programs will also need to determine if new hires will focus on a specific service (eg, orthopedic hospitalist) or whether job descriptions will include a mix of activities (eg, 3 months' teaching service, 3 months' nonhousestaff medical service, and 3 months' surgical comanagement service). A second and equally important question is where does the hospitalist live? If cardiology wants hospitalists to care for their patients, should they be hired and mentored by cardiologists or by hospitalists in a division of general or hospital medicine? In many cases, a graduating resident with plans to pursue a fellowship (eg, cardiology or hematology/oncology) may be a perfect candidate for a 1‐year position on his or her future specialty service. However, in the long term, maintaining all the academic hospitalists under the same umbrella will provide greater mentorship, professional development, opportunities for collaboration, clinical diversity, and sense of belonging to a group, rather than being a token hospitalist for another division.

Compensation and Financial Relationships with AMCs

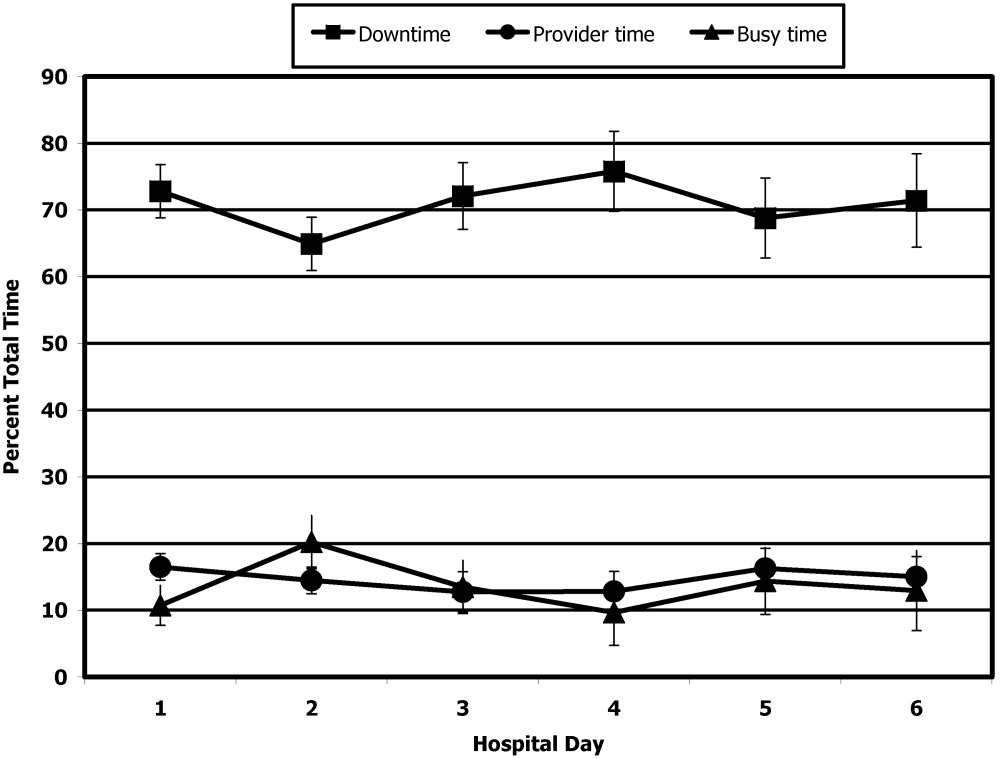

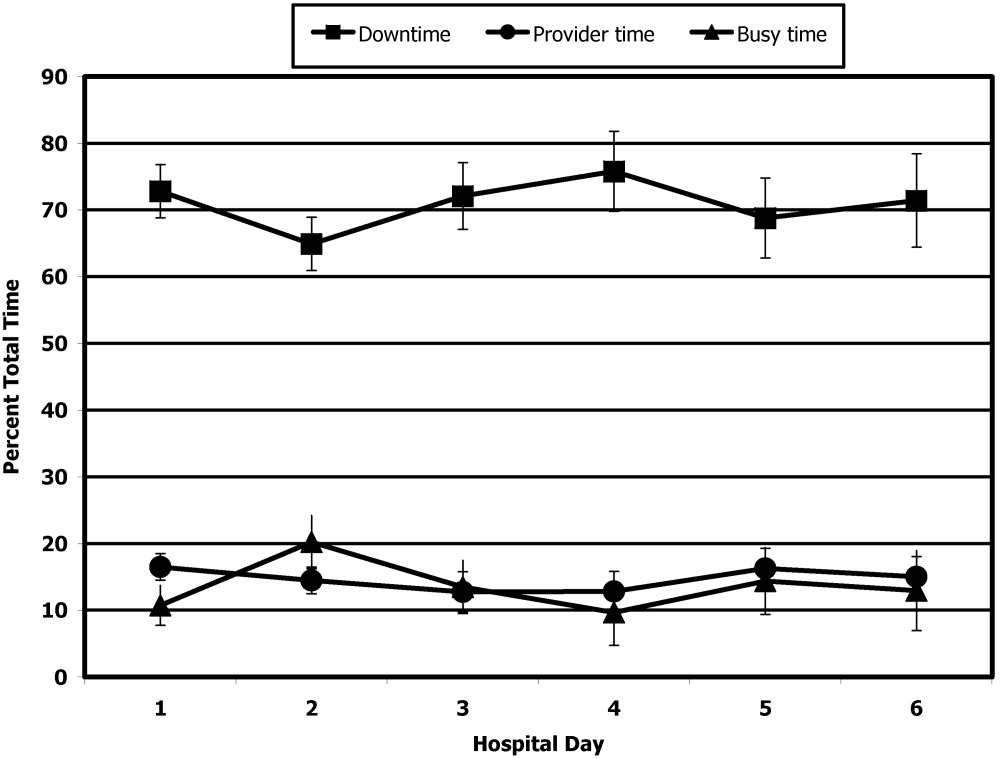

Salaries for hospitalists working on nonhousestaff services are typically higher at AMCs, which are competing with community standards given the similar level of clinical hours worked. However, although pay for nonhousestaff activities should reflect the nature of the work, compensation models based on clinical productivity alone may prove inadequate. It appears hospitalists working in academic facilities spend significant time on indirect patient care because of these hospitals' inefficiencies, usually not found in community settings.43 Devising compensation for an academic hospitalist requires careful attention and must balance a number of factors because these hospitalists will not generate their entire salary from clinical services. Financial support must come from either the division or medical center, an annual negotiation at AMCs.

Several methods exist to structure hospitalist compensation. A hospitalist's salary may be fixed, may have a base salary with incentives, or may be derived based on clinical productivity. For example, if a hospital medicine program provides both housestaff and nonhousestaff services and employs a fixed‐salary approach, it may choose a menu‐style method to determine compensation (eg, 6 months on nonhousestaff service at x dollars/month + 3 months on housestaff service at x dollars/month = annual salary). If a hospitalist takes on a funded nonclinical role or secures extramural funding, the salary menu gets adjusted accordingly as the clinical time is bought out. Critics of the fixed‐salary approach argue that paying each hospitalist the same salary regardless of the specific job description yields an inequitable system in which some are rewarded with less clinical time.

Compensation should probably have a guaranteed base salary with incentives, which could be determined by a formula that weighs clinical productivity, quality improvement efforts, scholarly activity, and teaching excellence. This model provides financial incentives to develop both clinically and academically but introduces complexity in determining a fair incentive structure. Finally, compensation can be structured without salary guarantee and putting compensation fully at risk based on clinical productivity, although this is an unlikely strategy for any hospital medicine group. This approach does disproportionately reward high volume providers, potentially at the risk of quality and safety, but also creates significant incentives to improve efficiency.

With respect to AMC relationships, hospital medicine programs must ensure the positive return on investment that drives financial support at their institutions. This fundamental economic dynamic makes AMCs dependent on their hospital medicine groups and vice versa. We caution programs from solely relying on measures such as reduced hospital costs or length of stay as a basis of funding unless there is a reward for maintaining performance once it inevitably plateaus. Moreover, explicitly tying utilization efficiency (ie, length of stay) to salary violates Stark rules44 and carries potential malpractice implications should patient care errors be attributable to premature hospital discharge. Over time hospitalists will need to maintain clinical benchmarks but also provide additional and valued services to their institutions, including quality and safety improvement activities and compliance with residency work hour restrictions.

Defining the Academic Hospitalist

The question is simple and perhaps philosophical: Are hospitalists who work at an AMC academic hospitalists? And what job description truly defines an academic hospitalist? Currently, there are no standards for the clinical activity of an academic hospitalist position (eg, number of weeks, weekends, and hours) or for assessment of nonclinical productivity. Hospital medicine programs face the challenge of defining positions that fulfill the growing clinical mission at AMCs but have little experience or guidance in ensuring they will lead to advancing the academic mission. Specifically, how do hospitalists who provide mostly clinical care, particularly on nonhousestaff services, achieve promotion? Hospital medicine program leadership must create enough opportunity and time for the development of skills in research, education, and quality or systems improvement if academic hospitalists are to succeed.

The Association of Chiefs of General Internal Medicine (ACGIM), the Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM), and the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) are currently collaborating to develop consensus guidelines in this area. Ultimately, through the efforts of these important governing bodies, the specialty of hospital medicine will be able to demonstrate the unique skills and services they provide and move toward advocating for academic promotion criteria that recognize their value and accomplishments.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Many lament that the milieu for academic hospitalists raises more challenges than solutions, but we believe the current era is one of excitement and opportunity. In the coming years, we will experience continued growth of nonhousestaff services, including greater comanagement with our surgical and medical specialty colleagues. These opportunities will create new relationships and increase our visibility in AMCs. However, we must remain committed to studying nonhousestaff services and determine if and how they differ from their housestaff and community counterparts, as this will be an important step toward addressing current challenges.

As hospitalists take on increasingly diverse roles,45 we must also lead initiatives to better train, recruit, and retain those interested in our specialty. Promoting our field and recruiting future faculty should occur through local hospitalist career nights, events at national meetings (targeting students, housestaff, and fellows), and other mechanisms utilized by our subspecialty colleagues. For housestaff interested in fellowship training, the growing number of hospitalist fellowships can provide skills in teaching and quality improvement.46 For trainees committed to research, we should work with existing general medicine research fellowships and partner to provide hospitalist mentorship.

Hospitalists are in a unique position to influence the delivery of clinical services, shape the future of residency training, guide quality and safety improvement initiatives, and take on leadership roles through our departments, universities, and medical centers. With the growing number of clinical services being added to our portfolio, we will need careful planning and evaluation of our efforts to build successful partnerships and develop faculty roles that balance clinical and academic pursuits to sustain long‐term and satisfying hospitalist careers.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Information related to the ACGME's effort to address resident duty hours and other relevant resource materials. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/acWebsite/dutyHours/dh_index.asp Accessed May 28,2007.

- ,,,.The status of hospital medicine groups in the United States.J Hosp Med.2006;1:75–80.

- .Reflections: the hospitalist movement a decade later.J Hosp Med.2006;1:248–252.

- .Duty hours for resident physicians—tough choices for teaching hospitals.N Engl J Med.2002;347:1275–1278.

- ,.Resident work hours, hospitalist programs and academic medical centers.The Hospitalist.2005;Jan/Feb:30–33.

- .Adapting to duty‐hour limits—four years on.N Engl J Med.2007;356:2668–2670.

- ,,,,,.Effects of work hour reduction on residents' lives: a systematic review.JAMA.2005;294:1088–1100.

- ,,,,.Impact of reduced duty hours on residents' educational satisfaction at the University of California, San Francisco.Acad Med.2006;81:76–81.

- ,,, et al.Effect of Residency Duty‐Hour Limits. Views of Key Clinical Faculty.Arch Intern Med.2007;167:1487–1492.

- ,,,.Perceived impact of duty hours regulation: a survey of residents and program directors.Am J Med.2007;120:644–648.

- ,,,.The impact of duty hours on resident self reports of errors.J Gen Intern Med.2007;22:205–209.

- ,,,,.Managing discontinuity in academic medical centers: strategies for a safe and effective resident sign‐out.J Hosp Med.2006;1:257–266.

- ,.Changes in hospital mortality associated with residency work‐hour regulations.Ann Intern Med.2007;147:73–80.

- ,,,.Changes in outcomes for internal medicine inpatients after work‐hour regulations.Ann Intern Med.2007;147:97–103.

- ,,, et al.Mortality among hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries in the first 2 years following ACGME resident duty hour reform.JAMA.2007;298:975–983.

- ,,, et al.Mortality among patients in VA hospitals in the first 2 years following ACGME resident duty hour reform.JAMA.2007;298:984–991.

- .An elusive balance—residents' work hours and the continuity of care.N Engl J Med.2007;356:2665–2667.

- ,.Hippocrates affirmed? Limiting residents' work hours does no harm to patients.Ann Intern Med.2007;356:143–144.

- ,.Evaluating resident duty hour reforms.JAMA.2007;298:1055–1057.

- ,,,,.Housestaff team workload and organization effects on patient outcomes in an academic general internal medicine inpatient service.Arch Intern Med.2007;167:47–52.

- ,,,.Predicting future staffing needs at teaching hospitals: use of an analytical program with multiple variables.Arch Surg.2007;142:329–334.

- . A primer on: resident work hours. American Medical Student Association. 6th ed. 2005. Available at: http://www.amsa.org/rwh/RWHprimer_6thEdition.pdf. Accessed May 28,2007.

- ,.The hospitalist movement 5 years later.JAMA.2002;287:487–494.

- ,.The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system.N Engl J Med.1996;335:514–517.

- .The future of hospital medicine: evolution or revolution?Am J Med.2004;117:446–450.

- Society of Hospital Medicine. Media Center link: Growth of hospital medicine nationwide. Available at www.hospitalmedicine.org. Accessed May 28,2007.

- Kohn L,Corrigan JM,Donaldson MS, eds.To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System.Washington DC:Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine, National Academy Press;2000.

- Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine.Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century.Washington, DC:National Academy Press;2001.

- ,.Hospitalists in teaching hospitals: opportunities but not without danger.J Gen Intern Med.2004;19:392–393.

- .What will board certification be‐and mean‐for hospitalists?J Hosp Med.2007;2:102–104.

- .Academic medical centers under siege.N Engl J Med.1994;331:1370–1371.

- ,.Academic medicine meets managed care: a high impact collision.Acad Med.1996;71:839–845.

- .Preventing the academic medical center from becoming an oxymoron.Acad Med.1996;71:117–120.

- ,,.Why have academic medical center survived?JAMA.2005:293;1495–1500.

- ,,,.Comparison of hospitalist and nonhospitalists in inpatient length of stay adjusting for patient and physician characteristics.J Gen Intern Med.2004;19:1127–1132.

- ,,.Comparison of hospital costs and length of stay for community internists, hospitalists, and academicians.J Gen Intern Med.2007;22;662–667.

- ,.The impact of hospitalists on the cost and quality of inpatient care in the United States: a research synthesis.Med Care Res Rev.2005;62:379–406.

- ,,.Hospitalists and an innovative emergency department admissions process.J Gen Intern Med.2004;19:266–268.

- ,,,,.Comparison of resource utilization and clinical outcomes between teaching and nonteaching medical services.J Hosp Med.2007;2:150–157.

- ,,.Comparison of hospital costs and length of stay for community internists, hospitalists, and academicians.J Gen Intern Med.2007;22:662–667.

- ,,,.Preparing for “diastole”: advanced training opportunities for academic hospitalists.J Hosp Med.2006;1:368–377.

- Society of Hospital Medicine Career Satisfaction Task Force. White Paper on Hospitalist Career Satisfaction. 2006;1–45. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org. Accessed August 11,2007.

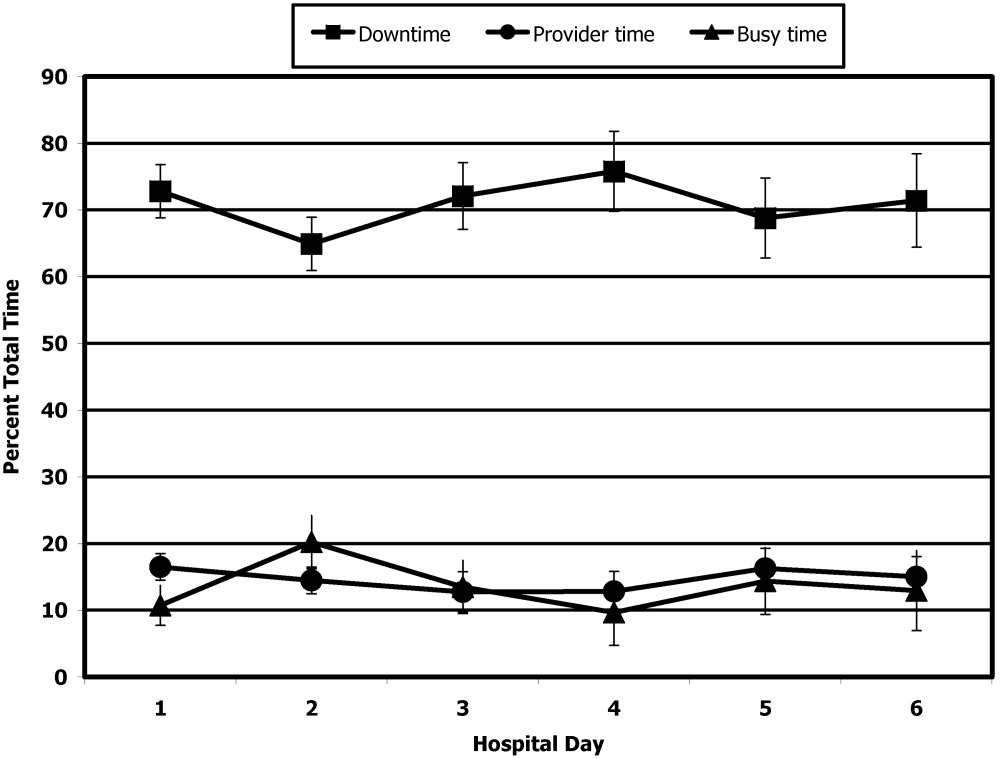

- ,,.How hospitalists spend their time: insights on efficiency and safety.J Hosp Med.2006;1:88–93.

- A Guide to Complying with Stark Self‐Referral Rules.Washington, DC:Atlantic Information Services, Inc.; 2004. Available at: http://www.aispub.com/. Accessed September 9, 2007.

- ,.The expanding role of hospitalists in the United States.Swiss Med Wkly.2006;136:591–596.

- ,,,.Hospital medicine fellowships: works in progress.Am J Med.2006;119:72e71–e77.

Many academic medical centers (AMCs) have developed nonhousestaff services to provide clinical care once provided by physicians‐in‐training. These services, often staffed by hospitalists and/or midlevel providers, have experienced tremendous growth in the past few years, yet very little exists in the literature about their development, structure, efficacy, or impact on hospitals, patients, and hospital medicine programs. The primary forces driving this growth include Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) resident duty hour restrictions,1 growth of the hospitalist movement,2 and the emphasis on simultaneously improving financial performance and quality of care in AMCs.3

Resident Duty Hour Restrictions

In 2003, the ACGME mandated restrictions on resident work hours, limiting trainees to 80 hours per week.1 Many training programs struggled with how to provide important clinical services while complying with the new restrictionscreating numerous models that bridged care between different shifts of residents.45 Implementation of day floats (a dedicated resident who rounds with the postcall team), night floats (a dedicated overnight resident who admits and cross‐covers patients), or some variation of both was common.6 No guidelines accompanied the ACGME mandate, leaving institutions to independently structure their programs without a known best practice.

Subsequent literature carefully addressed how the duty hour restrictions affect residents' lives and education but failed to discuss models for providing care.711 Training programs began to institute necessary changes but in doing so, created greater patient discontinuity and increased handoffs between residents, elevating the potential for adverse patient outcomes.12 Recent large‐scale studies indicate that inpatient care is the same or improved since adoption of the duty hour restrictions,1316 but controversy continues, with several editorials debating the issue.1719

Because increasing the volume of patients on housestaff services was not a viable option,20 many AMCs created nonhousestaff services and hired midlevel providers (nurse practitioners and physician assistants) to offset resident workloads and comply with the new restrictions. However, this strategy represented a very expensive alternative.21 Moreover, the current 80‐hour work limits may be revised downward, particularly given the lower restrictions in other countries,22 and this will further drive the demand for nonhousestaff services. Hospitalists, with their documented impact on efficiency and return on investment,23 represent a solution to fill these needs and have quickly become the predominant approach at AMCs.

The Hospitalist Movement

Since the term hospitalist was first coined in 1996,24 the remarkable growth of the number of practicing hospitalists emphasizes how first community hospitals and now AMCs have embraced this approach.25 With more than 20,000 nationwide and projections that the field will grow to 30,000 by 2010,26 hospitalists are becoming the primary providers for in‐patients.2 This growth was further catalyzed when widely expressed concerns about safety and quality became public,2728 and hospitalists incorporated patient safety and quality improvement activities into their efforts.3 The confluence of these factors also prompted emergence of hospital medicine programs at AMCs, a growth that came with anticipated dangers.29 Reflecting the recognition that hospital medicine is becoming a separate specialty30 and is integral to the functioning of an AMC, institutions now operate dedicated divisions of hospital medicine.

AMCs and Hospital Performance

AMCs operate 3 related enterprises: a medical school that trains future physicians, a research arena that promotes basic and clinical investigation, and health care services that often encompass both hospitals and clinics. The financial viability of AMCs has always been a topic of debate, largely because of the different missions they pursue and the financial means by which they survive.3133 Over the past decade, cuts in Medicare reimbursement, challenges in balancing bed availability with occupancy rates, and a growing emphasis on cost reduction have created a more competitive health care environment, but without the predicted demise of AMCs.34 Because education and research generally fail to bolster the bottom line, AMCs have focused on optimizing clinical services to promote financial viability.

Hospitalists are uniquely positioned to help this bottom line, just as they do at community hospitals. Their involvement in patient care may produce reductions in length of stay, greater efficiency in discharge planning, and significant cost savings.3537 Hospitalists may also improve throughput in emergency departments and decrease wait times, leading to more efficient bed utilization.38 This leads to a potential for greater hospital revenue by increasing both the number of admissions, particularly surgical cases, and staffed inpatient beds, the latter a premium, as AMCs continue to expand their bed capacity almost annually. Finally, hospitalists may serve as change agents in improving the quality and safety of care delivered, an increasingly important metric given the desire for and expansion of publicly reported measures.

From a financial standpoint, Medicare support to AMCs for training residents now subsidizes fewer clinical care hours. Hospitalist‐driven nonhousestaff services will continue to fulfill a need created by this marked change in residency training. The tension of who pays for nonhousestaff servicesincreased federal support, financial backing from AMCs, or academic department fundsposes an ongoing struggle. In fact, this may be the most important issue currently debated among hospital administrators and department chairs. Regardless, AMCs continue to view hospitalists as a mechanism (or even solution) to maintaining their financial bottom line through improving care delivery systems, adhering to resident work hour restrictions, leading quality and safety improvement initiatives, and improving clinical patient outcomes.

MODELS FOR NONHOUSESTAFF MEDICAL SERVICES

For AMCs developing nonhousestaff services, the process begins by addressing a series of important questions (Table 1). How these questions are answered is often driven by local factors such as the vision of local leadership and the availability of important resources. Nonetheless, it is important for hospitals to share their experiences because best practices remain unclear. Table 2 provides a tabular snapshot of nonhousestaff medicine services at 5 AMCs to highlight similarities and differences. Data in the table were compiled by having a representative from each AMC report the different attributes, which reflects each program as of July 2007. Table 2 provides no data on the quality or efficiency of housestaff versus nonhousestaff services, though this type of investigation is underway and will be critical in future planning.3940

| Questions | Potential options |

|---|---|

| Who will provide care on nonhousestaff services? | Physicians seeking a 1‐year position |

| Physicians committed to a purely clinical career | |

| Physicians committed to an academic career in hospital medicine | |

| Will hospitalists share nonhousestaff service time, or will there be dedicated nonhousestaff hospitalists? | Hybrid positions |

| Dedicated nonhousestaff hospitalists | |

| Use of PGY‐4s1‐year positions (often individuals planning a fellowship) | |

| How should staffing be organized? | Hospitalist‐only services |

| Use of midlevel providers | |

| Will there be 24‐7 coverage, and if so, how will nights be staffed? | Dedicated nocturnists |

| Shared among daytime hospitalists | |

| Midlevel providers | |

| Moonlighters (fellows or residents) | |

| What type of schedule will provide blocks of clinical time to ensure continuity of care but also ensure adequate nonclinical time to prevent physician burnout and turnover? | 7 on/7 off sequences |

| 45 day sequences | |

| Longer shifts with fewer shifts per month | |

| Shorter shifts with more shifts per month | |

| Where will patients on a nonhousestaff service receive care? | Geographically designed serviced |

| ○ Different floor | |

| ○ Different hospital | |

| Mixed among housestaff service | |

| What patient population will be cared for on the nonhousestaff service? | Same as on housestaff service |

| Based on bed availability if nonhousestaff service is geographic (a unit) | |

| Based on triage guidelines (lower acuity, observation patients, specific diagnoses) | |

| What volume of patients will be cared for on the nonhousestaff service? | Fixed census cap based on staffing |

| Flexible census depending on activity of housestaff service (above their cap) | |

| Will compensation for providing nonhousestaff services differ from that on housestaff services? | Higher base salary |

| Incentives tied to nonhousestaff time | |

| Different incentive structures |

| Attributes | BWH | Emory | University of Michigan | Northwestern | UCSF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Description of staffing model | Mon.‐Sun.: 1 daytime Hospitalist | Mon.‐Sun.: 4 daytime hospitalists, 2 swing shift admitters | Weekdays: 7 daytime hospitalists, 1 swing shift hospitalist | Mon.‐Sun.: 8 daytime hospitalists, 1 triage hospitalist | Weekdays: 2 daytime hospitalists, 1 swing shift hospitalist |

| Nights: 1 MD | Nights: 1 MDs | Weekends: 7 daytime hospitalists | Nights: 2 MDs | Weekends: 2 daytime hospitalists | |

| Nights: 2 MDs | Nights: 1 MD | ||||

| Location of service | In same university hospital | In same university hospital | In same university hospital | In same university hospital | Physically separate hospital affiliate (UCSF Medical Center at Mount Zion) |

| Nonhousestaff FTEs/total hospitalist group | 3/15 | 10/14 | 20/30 | 25/34 | 6/36 |

| What hospitalists provide care on nonhous estaff services? | Core of 3 hospitalists (also do month on housestaff service) | Hospitalist group shares nonhousestaff services | Core of 14 FTEs dedicated to nonhousestaff services | Hospitalist group shares nonhousestaff services | Core of 6 Mount Zionbased hospitalists (also spend 23 months on housestaff service at university hospital) |

| Other 6 FTEs consist of 10 faculty with mixed roles | |||||

| Age of service | 2 years | 4 years | 3 years | 5 years | 3 years |

| How patients get assigned to non‐housestaff service? | 1. Only ED admissions with no transfers from ICU or other services | Assigned by rotation | 1. Alternating admissions with housestaff services during afternoon | 1. Alternating admissions with housestaff services during day | 1. Lower‐acuity admissions from ED |

| 2. Admit whenever bed open on service (geographic) | 2. Observation cases triaged directly to service | 2. Lower‐acuity patients and direct admissions | 2. Lower‐acuity admissions from clinics | ||

| 3. Once housestaff cap, all subsequent admits until midnight to nonhousestaff service | 3. Nonhousestaff service admits all patients once resident caps reached | 3. Transfers from housestaff service no longer requiring tertiary services (or with complex discharge planning) | |||

| Average daily census of nonhousestaff service | 12 | 56 | 70 (75 cap) | 8595 | 2026 |

| Number of shifts per month/shift duration | 15/1012 hours | 15/12 hours | 1517 (depending on number of nights covered)/812 hours (swing = 8 hours, day = 1012 hours, night = 12 hours) | 20/1012 hours | 1617/1012 hours |

| Shift sequences | 710 days consecutive | Variable | 67 days consecutive followed by 1 night for those who cover nights | 7 days consecutive | 4‐ to 6‐day variable sequences |

| Total clinical days worked/year | 168 | 182.5 | 185202 (depending on number of nights covered) | 212 | 196 |

| Weekend clinical time | 50% of weekends | 50% of weekends | 50% of weekends | 50% of weekends | 50% of weekends |

| Night coverage/by whom? | Yes/exclusively moonlighters | Yes/shared (50% covered by 1 dedicated nocturnist) | Yes/66% of nights staffed by dedicated nocturnists with remainder shared | Yes/exclusively by six 1‐year nocturnists | Yes/exclusively by moonlighters |

| Presence of midlevel providers | Yes 6 FTE PAs Mon.‐Sun. | No | Yes 8 FTE PAs weekdays | No | No |

| Presence of dedicated case manager | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Presence of medical students for patient care | No | No | Yes, 4th‐year subinterns or students on elective rotation | No | No |

| Compensation model | Salary + weekend bonus beyond 10 | Salary + incentive | Base + shift‐based incentive + quality incentive | Salary + incentive | Salary |

| Pay differential compared to housestaff service compensation | 10% Higher because of weekend bonus | None | About 20% higher base compensation; loan forgiveness program tied to nonhousestaff time | None | About 20% higher compensation |

| Hospital financial support | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Table 2 does illustrate several important considerations in structuring nonhousestaff services. For example, if a nonhousestaff service operates at a different physical location, careful triage of patients is necessary. Resources, including the availability of subspecialty and surgical consultants, may differ, and thus patient complexity and acuity may dictate whether a patient gets admitted to the nonhousestaff service. These triage factors were a major challenge in the design of UCSF's nonhousestaff service. The other nonhousestaff services handle overflow admissions after the housestaff service reaches a census or admission cap; transfers between services rarely occur, and resources are similar.

Other observations include that hospitalists work a similar number of hours each year and cover 50% of weekends but with differing shift lengths and sequences. Each service also provides night coverage but only Emory, the University of Michigan, and Northwestern utilize dedicated nocturnists. The University of Michigan and Brigham & Women's Hospital are the only sites that employ midlevel providers who work closely with hospitalists. In terms of group structure, Northwestern's hospitalists are the most integrated, with each hospitalist sharing equal responsibility for nonhousestaff coverage. In contrast, the other programs use selected hospitalists or a dedicated core of hospitalists to provide nonhousestaff services. Compensation models also vary, with certain groups salaried and others having incentive systems, although all receive hospital‐based funding support. Hospital‐based funding support ranges from 40% to 100% of total program costs across sites, creating similar variance in a given program's deficit risk. Finally, most programs do compensate nonhousestaff services at higher rates.

All the decisions captured in Table 2 have implications for costs, recruitment, and service structure. Furthermore, the striking variations demonstrate how different academic hospitalist positions can occur both within a hospital medicine group and across institutions. Of note, Table 2 only characterizes nonhousestaff medicine services, not the growing number of comanagement (eg, orthopedics, neurosurgery, or hematology/oncology) and other clinical services (eg, observation unit or preoperative medicine clinic) also staffed by hospitalists at AMCs.

CHALLENGES

Hospital medicine programs and AMCs face several challenges in building non‐housestaff services, but these will likely become less daunting as programs learn from their own experiences, from those of colleagues at other institutions, and from future investigations of these care models. We highlight a few issues below that warrant important consideration.

The Equities of the System

Prior to developing nonhousestaff services, our academic hospitalist programs scheduled teaching service time in month or half‐month blocks, balancing holidays and weekends. Equity in scheduling became a function of required clinical time, sources of non‐clinical funding (eg, grants, educational or administrative roles), and expectations for scholarship, attributes typical of most subspecialty academic divisions. Given the differing clinical missions that have stimulated academic hospital medicine programs to form, concerns of scheduling equity have grown, posing challenges not experienced in other divisions.

Institutions that choose to divide housestaff and nonhousestaff duties among distinct groups of hospitalists create the potential for a 2‐tiered system, one in which those with housestaff roles are more valued and respected by the institution. Hospitalists working on nonhousestaff services admit patients, write orders, and field direct patient calls, a role rarely undertaken by subspecialty attendings or hospitalists on housestaff services. Our collective experiences provide evidence of the danger of this second‐class‐citizen status, one that requires attention to ensure job satisfaction, retention, and necessary career development.

Institutions have accentuated the second‐class‐citizen concern by staffing nonhousestaff roles with 1‐year hospitalistsPGY‐4s. Most of these hires in our institutions are individuals just out of residency and intent on pursuing a fellowship. We speculate that they enjoy the comforts of the AMC where they often trained and accept purely nonhousestaff positions because of what they view as an appealing work schedule and salary. Although this approach addresses the growing need for hospitalists on nonhousestaff services in the short term, these positions must remain attractive enough (both financially and professionally) to encourage residency graduates to pursue an academic hospitalist career instead of a 1‐year position as a transition to fellowship. Otherwise, the approach conveys a message that relatively inexperienced physicians are good enough to be hospitalists.

Developing a cadre of clinically focused hospitalists who provide outstanding patient care and also garner respect as successful academicians is a difficult task. Although 1 group in our sample (Northwestern) shares nonhousestaff responsibilities equally, others may find this impractical, particularly where faculty members were hired before nonhousestaff services were established. Redefining such clinical positions several years into a career may be challenging, as it forces faculty members into roles they didn't sign up for or grandfathers them out of such roles, adding to the risk of a 2‐tiered system. Alternatively, groups may focus on building academic activities into nonhousestaff services, including medical student teaching, quality improvement, or clinical research activities. In this article, we deliberately classified these services as nonhousestaff rather than non‐teaching because the latter fails to acknowledge that these hospitalists often serve as teachers (eg, housestaff conferences, supervision of midlevel providers, and/or rotating medical students)an important if not symbolic distinction. It is imperative that planning for nonhousestaff services balance the larger academic mission of hospital medicine groups with creating equitable, valued, and sustainable job descriptions.

Defining the Patient Mix

Developing an optimal patient mix on nonhousestaff services also carries important implications. For services that work in parallel with the housestaff service and simply take extra patients above the resident cap, this concern may be less significant. However, other nonhousestaff services have been structured to care for lower‐acuity patients (eg, cellulitis, asthma, pneumonia) or select patient populations (eg, sickle cell or inflammatory bowel disease). This distribution system potentially changes the educational experience on the housestaff servicedecreasing the bread‐and‐butter admissionsbut also may affect the job satisfaction of hospitalists and midlevel providers on nonhousestaff services. Building triage criteria, working with emergency department leadership, and avoiding patients being turfed between different services is critical. We strongly recommend a regular process to review admissions to each service and determine when the triage process requires further calibration.

Recruitment and Retention

Traditionally, graduates of residency or fellowship training programs chose academic positions because of an interest in teaching, a desire for scholarship, or a commitment to research. Those interested in primarily clinical roles typically pursued positions in nonacademic settings. The development of nonhousestaff services challenges this paradigm because the objective for academic hospitalist leadership now becomes recruiting pure clinicians as well as academicians. These might be the same individual, a hospitalist who provides both housestaff and nonhousestaff services, or 2 different individuals if the nonhousestaff service is covered by dedicated hospitalists. In addition, with the current promotion structure in academia, a purely clinical position may be less attractive, as it provides fewer opportunities for advancement.

Therefore, recruitment and retention of academic hospitalists will require job descriptions that provide dedicated teaching opportunities, time for participation in quality and safety improvement projects, or pursuit of a scholarly interest in non‐clinical timethe diastole of an academic hospitalist.41 Hospital medicine leadership will also need to better distinguish off‐time from non‐clinical time, as many young hospitalists struggle to balance professional and personal commitmentsa recipe for burnout.42 Regardless of how clinical responsibilities differ between 2 hospitalists, providing them with similar academic resources is what will distinguish their positions from that in the community. Furthermore, many groups have chosen to pay faculty a premium for their nonhousestaff roles or to use specific recruitment incentives such as educational loan forgiveness programs.

With the expected growth of nonhousestaff services and surgical comanagement, hospital medicine programs will also need to determine if new hires will focus on a specific service (eg, orthopedic hospitalist) or whether job descriptions will include a mix of activities (eg, 3 months' teaching service, 3 months' nonhousestaff medical service, and 3 months' surgical comanagement service). A second and equally important question is where does the hospitalist live? If cardiology wants hospitalists to care for their patients, should they be hired and mentored by cardiologists or by hospitalists in a division of general or hospital medicine? In many cases, a graduating resident with plans to pursue a fellowship (eg, cardiology or hematology/oncology) may be a perfect candidate for a 1‐year position on his or her future specialty service. However, in the long term, maintaining all the academic hospitalists under the same umbrella will provide greater mentorship, professional development, opportunities for collaboration, clinical diversity, and sense of belonging to a group, rather than being a token hospitalist for another division.

Compensation and Financial Relationships with AMCs

Salaries for hospitalists working on nonhousestaff services are typically higher at AMCs, which are competing with community standards given the similar level of clinical hours worked. However, although pay for nonhousestaff activities should reflect the nature of the work, compensation models based on clinical productivity alone may prove inadequate. It appears hospitalists working in academic facilities spend significant time on indirect patient care because of these hospitals' inefficiencies, usually not found in community settings.43 Devising compensation for an academic hospitalist requires careful attention and must balance a number of factors because these hospitalists will not generate their entire salary from clinical services. Financial support must come from either the division or medical center, an annual negotiation at AMCs.

Several methods exist to structure hospitalist compensation. A hospitalist's salary may be fixed, may have a base salary with incentives, or may be derived based on clinical productivity. For example, if a hospital medicine program provides both housestaff and nonhousestaff services and employs a fixed‐salary approach, it may choose a menu‐style method to determine compensation (eg, 6 months on nonhousestaff service at x dollars/month + 3 months on housestaff service at x dollars/month = annual salary). If a hospitalist takes on a funded nonclinical role or secures extramural funding, the salary menu gets adjusted accordingly as the clinical time is bought out. Critics of the fixed‐salary approach argue that paying each hospitalist the same salary regardless of the specific job description yields an inequitable system in which some are rewarded with less clinical time.

Compensation should probably have a guaranteed base salary with incentives, which could be determined by a formula that weighs clinical productivity, quality improvement efforts, scholarly activity, and teaching excellence. This model provides financial incentives to develop both clinically and academically but introduces complexity in determining a fair incentive structure. Finally, compensation can be structured without salary guarantee and putting compensation fully at risk based on clinical productivity, although this is an unlikely strategy for any hospital medicine group. This approach does disproportionately reward high volume providers, potentially at the risk of quality and safety, but also creates significant incentives to improve efficiency.

With respect to AMC relationships, hospital medicine programs must ensure the positive return on investment that drives financial support at their institutions. This fundamental economic dynamic makes AMCs dependent on their hospital medicine groups and vice versa. We caution programs from solely relying on measures such as reduced hospital costs or length of stay as a basis of funding unless there is a reward for maintaining performance once it inevitably plateaus. Moreover, explicitly tying utilization efficiency (ie, length of stay) to salary violates Stark rules44 and carries potential malpractice implications should patient care errors be attributable to premature hospital discharge. Over time hospitalists will need to maintain clinical benchmarks but also provide additional and valued services to their institutions, including quality and safety improvement activities and compliance with residency work hour restrictions.

Defining the Academic Hospitalist

The question is simple and perhaps philosophical: Are hospitalists who work at an AMC academic hospitalists? And what job description truly defines an academic hospitalist? Currently, there are no standards for the clinical activity of an academic hospitalist position (eg, number of weeks, weekends, and hours) or for assessment of nonclinical productivity. Hospital medicine programs face the challenge of defining positions that fulfill the growing clinical mission at AMCs but have little experience or guidance in ensuring they will lead to advancing the academic mission. Specifically, how do hospitalists who provide mostly clinical care, particularly on nonhousestaff services, achieve promotion? Hospital medicine program leadership must create enough opportunity and time for the development of skills in research, education, and quality or systems improvement if academic hospitalists are to succeed.

The Association of Chiefs of General Internal Medicine (ACGIM), the Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM), and the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) are currently collaborating to develop consensus guidelines in this area. Ultimately, through the efforts of these important governing bodies, the specialty of hospital medicine will be able to demonstrate the unique skills and services they provide and move toward advocating for academic promotion criteria that recognize their value and accomplishments.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Many lament that the milieu for academic hospitalists raises more challenges than solutions, but we believe the current era is one of excitement and opportunity. In the coming years, we will experience continued growth of nonhousestaff services, including greater comanagement with our surgical and medical specialty colleagues. These opportunities will create new relationships and increase our visibility in AMCs. However, we must remain committed to studying nonhousestaff services and determine if and how they differ from their housestaff and community counterparts, as this will be an important step toward addressing current challenges.

As hospitalists take on increasingly diverse roles,45 we must also lead initiatives to better train, recruit, and retain those interested in our specialty. Promoting our field and recruiting future faculty should occur through local hospitalist career nights, events at national meetings (targeting students, housestaff, and fellows), and other mechanisms utilized by our subspecialty colleagues. For housestaff interested in fellowship training, the growing number of hospitalist fellowships can provide skills in teaching and quality improvement.46 For trainees committed to research, we should work with existing general medicine research fellowships and partner to provide hospitalist mentorship.

Hospitalists are in a unique position to influence the delivery of clinical services, shape the future of residency training, guide quality and safety improvement initiatives, and take on leadership roles through our departments, universities, and medical centers. With the growing number of clinical services being added to our portfolio, we will need careful planning and evaluation of our efforts to build successful partnerships and develop faculty roles that balance clinical and academic pursuits to sustain long‐term and satisfying hospitalist careers.

Many academic medical centers (AMCs) have developed nonhousestaff services to provide clinical care once provided by physicians‐in‐training. These services, often staffed by hospitalists and/or midlevel providers, have experienced tremendous growth in the past few years, yet very little exists in the literature about their development, structure, efficacy, or impact on hospitals, patients, and hospital medicine programs. The primary forces driving this growth include Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) resident duty hour restrictions,1 growth of the hospitalist movement,2 and the emphasis on simultaneously improving financial performance and quality of care in AMCs.3

Resident Duty Hour Restrictions

In 2003, the ACGME mandated restrictions on resident work hours, limiting trainees to 80 hours per week.1 Many training programs struggled with how to provide important clinical services while complying with the new restrictionscreating numerous models that bridged care between different shifts of residents.45 Implementation of day floats (a dedicated resident who rounds with the postcall team), night floats (a dedicated overnight resident who admits and cross‐covers patients), or some variation of both was common.6 No guidelines accompanied the ACGME mandate, leaving institutions to independently structure their programs without a known best practice.

Subsequent literature carefully addressed how the duty hour restrictions affect residents' lives and education but failed to discuss models for providing care.711 Training programs began to institute necessary changes but in doing so, created greater patient discontinuity and increased handoffs between residents, elevating the potential for adverse patient outcomes.12 Recent large‐scale studies indicate that inpatient care is the same or improved since adoption of the duty hour restrictions,1316 but controversy continues, with several editorials debating the issue.1719

Because increasing the volume of patients on housestaff services was not a viable option,20 many AMCs created nonhousestaff services and hired midlevel providers (nurse practitioners and physician assistants) to offset resident workloads and comply with the new restrictions. However, this strategy represented a very expensive alternative.21 Moreover, the current 80‐hour work limits may be revised downward, particularly given the lower restrictions in other countries,22 and this will further drive the demand for nonhousestaff services. Hospitalists, with their documented impact on efficiency and return on investment,23 represent a solution to fill these needs and have quickly become the predominant approach at AMCs.

The Hospitalist Movement

Since the term hospitalist was first coined in 1996,24 the remarkable growth of the number of practicing hospitalists emphasizes how first community hospitals and now AMCs have embraced this approach.25 With more than 20,000 nationwide and projections that the field will grow to 30,000 by 2010,26 hospitalists are becoming the primary providers for in‐patients.2 This growth was further catalyzed when widely expressed concerns about safety and quality became public,2728 and hospitalists incorporated patient safety and quality improvement activities into their efforts.3 The confluence of these factors also prompted emergence of hospital medicine programs at AMCs, a growth that came with anticipated dangers.29 Reflecting the recognition that hospital medicine is becoming a separate specialty30 and is integral to the functioning of an AMC, institutions now operate dedicated divisions of hospital medicine.

AMCs and Hospital Performance

AMCs operate 3 related enterprises: a medical school that trains future physicians, a research arena that promotes basic and clinical investigation, and health care services that often encompass both hospitals and clinics. The financial viability of AMCs has always been a topic of debate, largely because of the different missions they pursue and the financial means by which they survive.3133 Over the past decade, cuts in Medicare reimbursement, challenges in balancing bed availability with occupancy rates, and a growing emphasis on cost reduction have created a more competitive health care environment, but without the predicted demise of AMCs.34 Because education and research generally fail to bolster the bottom line, AMCs have focused on optimizing clinical services to promote financial viability.

Hospitalists are uniquely positioned to help this bottom line, just as they do at community hospitals. Their involvement in patient care may produce reductions in length of stay, greater efficiency in discharge planning, and significant cost savings.3537 Hospitalists may also improve throughput in emergency departments and decrease wait times, leading to more efficient bed utilization.38 This leads to a potential for greater hospital revenue by increasing both the number of admissions, particularly surgical cases, and staffed inpatient beds, the latter a premium, as AMCs continue to expand their bed capacity almost annually. Finally, hospitalists may serve as change agents in improving the quality and safety of care delivered, an increasingly important metric given the desire for and expansion of publicly reported measures.

From a financial standpoint, Medicare support to AMCs for training residents now subsidizes fewer clinical care hours. Hospitalist‐driven nonhousestaff services will continue to fulfill a need created by this marked change in residency training. The tension of who pays for nonhousestaff servicesincreased federal support, financial backing from AMCs, or academic department fundsposes an ongoing struggle. In fact, this may be the most important issue currently debated among hospital administrators and department chairs. Regardless, AMCs continue to view hospitalists as a mechanism (or even solution) to maintaining their financial bottom line through improving care delivery systems, adhering to resident work hour restrictions, leading quality and safety improvement initiatives, and improving clinical patient outcomes.

MODELS FOR NONHOUSESTAFF MEDICAL SERVICES

For AMCs developing nonhousestaff services, the process begins by addressing a series of important questions (Table 1). How these questions are answered is often driven by local factors such as the vision of local leadership and the availability of important resources. Nonetheless, it is important for hospitals to share their experiences because best practices remain unclear. Table 2 provides a tabular snapshot of nonhousestaff medicine services at 5 AMCs to highlight similarities and differences. Data in the table were compiled by having a representative from each AMC report the different attributes, which reflects each program as of July 2007. Table 2 provides no data on the quality or efficiency of housestaff versus nonhousestaff services, though this type of investigation is underway and will be critical in future planning.3940

| Questions | Potential options |

|---|---|

| Who will provide care on nonhousestaff services? | Physicians seeking a 1‐year position |

| Physicians committed to a purely clinical career | |

| Physicians committed to an academic career in hospital medicine | |

| Will hospitalists share nonhousestaff service time, or will there be dedicated nonhousestaff hospitalists? | Hybrid positions |

| Dedicated nonhousestaff hospitalists | |

| Use of PGY‐4s1‐year positions (often individuals planning a fellowship) | |

| How should staffing be organized? | Hospitalist‐only services |

| Use of midlevel providers | |

| Will there be 24‐7 coverage, and if so, how will nights be staffed? | Dedicated nocturnists |

| Shared among daytime hospitalists | |

| Midlevel providers | |

| Moonlighters (fellows or residents) | |

| What type of schedule will provide blocks of clinical time to ensure continuity of care but also ensure adequate nonclinical time to prevent physician burnout and turnover? | 7 on/7 off sequences |

| 45 day sequences | |

| Longer shifts with fewer shifts per month | |

| Shorter shifts with more shifts per month | |

| Where will patients on a nonhousestaff service receive care? | Geographically designed serviced |

| ○ Different floor | |

| ○ Different hospital | |

| Mixed among housestaff service | |

| What patient population will be cared for on the nonhousestaff service? | Same as on housestaff service |

| Based on bed availability if nonhousestaff service is geographic (a unit) | |

| Based on triage guidelines (lower acuity, observation patients, specific diagnoses) | |

| What volume of patients will be cared for on the nonhousestaff service? | Fixed census cap based on staffing |

| Flexible census depending on activity of housestaff service (above their cap) | |

| Will compensation for providing nonhousestaff services differ from that on housestaff services? | Higher base salary |

| Incentives tied to nonhousestaff time | |

| Different incentive structures |

| Attributes | BWH | Emory | University of Michigan | Northwestern | UCSF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Description of staffing model | Mon.‐Sun.: 1 daytime Hospitalist | Mon.‐Sun.: 4 daytime hospitalists, 2 swing shift admitters | Weekdays: 7 daytime hospitalists, 1 swing shift hospitalist | Mon.‐Sun.: 8 daytime hospitalists, 1 triage hospitalist | Weekdays: 2 daytime hospitalists, 1 swing shift hospitalist |

| Nights: 1 MD | Nights: 1 MDs | Weekends: 7 daytime hospitalists | Nights: 2 MDs | Weekends: 2 daytime hospitalists | |

| Nights: 2 MDs | Nights: 1 MD | ||||

| Location of service | In same university hospital | In same university hospital | In same university hospital | In same university hospital | Physically separate hospital affiliate (UCSF Medical Center at Mount Zion) |

| Nonhousestaff FTEs/total hospitalist group | 3/15 | 10/14 | 20/30 | 25/34 | 6/36 |

| What hospitalists provide care on nonhous estaff services? | Core of 3 hospitalists (also do month on housestaff service) | Hospitalist group shares nonhousestaff services | Core of 14 FTEs dedicated to nonhousestaff services | Hospitalist group shares nonhousestaff services | Core of 6 Mount Zionbased hospitalists (also spend 23 months on housestaff service at university hospital) |

| Other 6 FTEs consist of 10 faculty with mixed roles | |||||

| Age of service | 2 years | 4 years | 3 years | 5 years | 3 years |

| How patients get assigned to non‐housestaff service? | 1. Only ED admissions with no transfers from ICU or other services | Assigned by rotation | 1. Alternating admissions with housestaff services during afternoon | 1. Alternating admissions with housestaff services during day | 1. Lower‐acuity admissions from ED |

| 2. Admit whenever bed open on service (geographic) | 2. Observation cases triaged directly to service | 2. Lower‐acuity patients and direct admissions | 2. Lower‐acuity admissions from clinics | ||

| 3. Once housestaff cap, all subsequent admits until midnight to nonhousestaff service | 3. Nonhousestaff service admits all patients once resident caps reached | 3. Transfers from housestaff service no longer requiring tertiary services (or with complex discharge planning) | |||

| Average daily census of nonhousestaff service | 12 | 56 | 70 (75 cap) | 8595 | 2026 |

| Number of shifts per month/shift duration | 15/1012 hours | 15/12 hours | 1517 (depending on number of nights covered)/812 hours (swing = 8 hours, day = 1012 hours, night = 12 hours) | 20/1012 hours | 1617/1012 hours |

| Shift sequences | 710 days consecutive | Variable | 67 days consecutive followed by 1 night for those who cover nights | 7 days consecutive | 4‐ to 6‐day variable sequences |

| Total clinical days worked/year | 168 | 182.5 | 185202 (depending on number of nights covered) | 212 | 196 |

| Weekend clinical time | 50% of weekends | 50% of weekends | 50% of weekends | 50% of weekends | 50% of weekends |

| Night coverage/by whom? | Yes/exclusively moonlighters | Yes/shared (50% covered by 1 dedicated nocturnist) | Yes/66% of nights staffed by dedicated nocturnists with remainder shared | Yes/exclusively by six 1‐year nocturnists | Yes/exclusively by moonlighters |

| Presence of midlevel providers | Yes 6 FTE PAs Mon.‐Sun. | No | Yes 8 FTE PAs weekdays | No | No |

| Presence of dedicated case manager | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Presence of medical students for patient care | No | No | Yes, 4th‐year subinterns or students on elective rotation | No | No |