User login

What is the appropriate use of chronic medications in the perioperative setting?

Case

A 72-year-old female with multiple medical problems is admitted with a hip fracture. Surgery is scheduled in 48 hours. The patient’s home medications include aspirin, carbidopa/levodopa, celecoxib, clonidine, estradiol, ginkgo, lisinopril, NPH insulin, sulfasalazine, and prednisone 10 mg a day, which she has been taking for years. How should these and other medications be managed in the perioperative period?

Background

Perioperative management of chronic medications is a complex issue, as physicians are required to balance the beneficial and harmful effects of the individual drugs prescribed to their patients. On one hand, cessation of medications can result in decompensation of disease or withdrawal. On the other hand, continuation of drugs can alter metabolism of anesthetic agents, cause perioperative hemodynamic instability, or result in such post-operative complications as acute renal failure, bleeding, infection, and impaired wound healing.

Certain traits make it reasonable to continue medications during the perioperative period. A long elimination half-life or duration of action makes stopping some medications impractical as it takes four to five half-lives to completely clear the drug from the body; holding the drug for a few days around surgery will not appreciably affect its concentration. Stopping drugs that carry severe withdrawal symptoms can be impractical because of the need for lengthy tapers, which can delay surgery and result in decompensation of underlying disease.

Drugs with no significant interactions with anesthesia or risk of perioperative complications should be continued in order to avoid deterioration of the underlying disease. Conversely, drugs that interact with anesthesia or increase risk for complications should be stopped if this can be accomplished safely. Patient-specific factors should receive consideration, as the risk of complications has to be balanced against the danger of exacerbating the underlying disease.

Overview of the Data

The challenge in providing recommendations on perioperative medication management lies in a dearth of high-quality clinical trials. Thus, much of the information comes from case reports, expert opinion, and sound application of pharmacology.

Antiplatelet therapy: Nuances of perioperative antiplatelet therapy are beyond the scope of this review, but some general principles can be elucidated from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) 2007 perioperative guidelines.1 Management of antiplatelet therapy should be done in conjunction with the surgical team, as cardiovascular risk has to be weighed against bleeding risk.

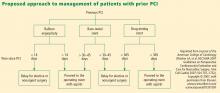

Aspirin therapy should be continued in all patients with a history of coronary artery disease (CAD), balloon angioplasty, or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), unless the risk of bleeding complications is felt to exceed the cardioprotective benefits—for example, in some neurosurgical patients.1

Clopidogrel therapy is crucial for prevention of in-stent thrombosis (IST) following PCI because patients who experience IST suffer catastrophic myocardial infarctions with high mortality. Ideally, surgery should be delayed to permit completion of clopidogrel therapy—30 to 45 days after implantation of a bare-metal stent and 365 days after a drug-eluting stent. If surgery has to be performed sooner, guidelines recommend operating on dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel.1 Again, this course of treatment has to be balanced against the risk of hemorrhagic complications from surgery.

Both aspirin and clopidogrel irreversibly inhibit platelet aggregation. The recovery of normal coagulation involves formation of new platelets, which necessitates cessation of therapy for seven to 10 days before surgery. Platelet inhibition begins within minutes of restarting aspirin and within hours of taking clopidogrel, although attaining peak clopidogrel effect takes three to seven days, unless a loading dose is used.

Cardiovascular Drugs

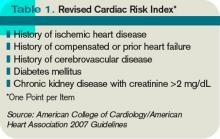

Beta-blockers in the perioperative setting are a focus of an ongoing debate beyond the scope of this review (see “What Pre-Operative Cardiac Evaluation of Patients Undergoing Intermediate-Risk Surgery Is Most Effective?,” February 2008, p. 26). Given the current evidence and the latest ACC/AHA guidelines, it is still reasonable to continue therapy in patients who are already taking them to avoid precipitating cardiovascular events by withdrawal. Patients with increased cardiac risk, demonstrated by a Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI) score of ≥2 (see Table 1, p. 12), should be considered for beta-blocker therapy before surgery.1 In either case, the dose should be titrated to a heart rate <65 for optimal cardiac protection.1

Statins should be continued if the patient is taking them, especially because preoperative withdrawal has been associated with a 4.6-fold increase in troponin release and a 7.5-fold increased risk of myocardial infarction (MI) and cardiovascular death following major vascular surgery.2 Patients with increased cardiac risk— RCRI ≥1—can be considered for initiation of statin therapy before surgery, although the benefit of this intervention has not been examined in prospective studies.1

Amiodarone has an exceptionally long half-life of up to 142 days. It should be continued in the perioperative period.

Calcium channel blockers (CCBs) can be continued with no unpleasant perioperative hemodynamic effects.1 CCBs have potential cardioprotective benefits.

Clonidine withdrawal can result in severe rebound hypertension with reports of encephalopathy, stroke, and death. These effects are exacerbated by concomitant beta-blocker therapy. For this reason, if a patient is expected to be NPO for more than 12 hours, they should be converted to a clonidine patch 48-72 hours before surgery with concurrent tapering of the oral dose.3

Digoxin has a long half-life (up to 48 hours) and should be continued with monitoring of levels if there is a change in renal function.

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) have been associated with a 50% increased risk of hypotension requiring vasopressors during induction of anesthesia.4 However, it is worth mentioning that this finding has not been corroborated in other studies. A large retrospective cohort of cardiothoracic surgical patients found a 28% increased risk of post-operative acute renal failure (ARF) with both drug classes, although another cardiothoracic report published the same year demonstrated a 50% reduction in risk with ACEIs.5,6 Although the evidence of harm is not unequivocal, perioperative blood-pressure control can be achieved with other drugs without hemodynamic or renal risk, such as CCBs, and in most cases ACEIs/ARBs should be stopped one day before surgery.

Diuretics carry a risk of volume depletion and electrolyte derangements, and should be stopped once a patient becomes NPO. Excess volume is managed with as-needed intravenous formulations.

Drugs Acting on the Central Nervous System

The majority of central nervous system (CNS)-active drugs, including antiepileptics, antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, bupropion, gabapentin, lithium, mirtazapine, selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs and SNRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), and valproic acid, balance a low risk of perioperative complications against a significant potential for withdrawal and disease decompensation. Therefore, these medications should be continued.

Carbidopa/Levodopa should be continued because abrupt cessation can precipitate systemic withdrawal resembling serotonin syndrome and rapid deterioration of Parkinson’s symptoms.

Monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) therapy usually indicates refractory psychiatric illness, so these drugs should be continued to avoid decompensation. Importantly, MAOI-safe anesthesia without dextromethorphan, meperidine, epinephrine, or norepinephrine has to be used due to the risk of cardiovascular instability.7

Diabetic Drugs

Insulin therapy should be continued with adjustments. Glargine basal insulin has no peak and can be continued without changing the dose. Likewise, patients with insulin pumps can continue the usual basal rate. Short-acting insulin or such insulin mixes as 70/30 should be stopped four hours before surgery to avoid hypoglycemia. Intermediate-acting insulin (e.g., NPH) can be administered at half the usual dose the day of surgery with a perioperative 5% dextrose infusion. NPH should not be given the day of surgery if the dextrose infusion cannot be used.8

Incretins (exenatide, sitagliptin) rarely cause hypoglycemia in the absence of insulin and may be beneficial in controlling intraoperative hyperglycemia. Therefore, these medications can be continued.8

Thiazolidinediones (TZDs; pioglitazone, rosiglitazone) alter gene transcription with biological duration of action on the order of weeks and low risk of hypoglycemia, and should be continued.

Metformin carries an FDA black-box warning to discontinue therapy before any intravascular radiocontrast studies or surgical procedures due to the risk of severe lactic acidosis if renal failure develops. It should be stopped 24 hours before surgery and restarted at least 48-72 hours after. Normal renal function should be confirmed before restarting therapy.8

Sulfonylureas (glimepiride, glipizide, glyburide) carry a significant risk of hypoglycemia in a patient who is NPO; they should be stopped the night before surgery or before commencement of NPO status.

Hormones

Antithyroid drugs (methimazole, propylthiouracil) and levothyroxine should be continued, as they have no perioperative contraindications.

Oral contraceptives (OCPs), hormone replacement therapy (HRT), and raloxifene can increase the risk of DVT. The largest study on the topic was the HERS trial of postmenopausal women on estrogen/progesterone HRT. The authors reported a 4.9-fold increased risk of DVT for 90 days after surgery.9 Unfortunately, no information was provided on the types of surgery, or whether appropriate and consistent DVT prophylaxis was utilized. HERS authors also reported a 2.5-fold increased risk of DVT for at least 30 days after cessation of HRT.9

Given the data, it is reasonable to stop hormone therapy four weeks before surgery when prolonged immobilization is anticipated and patients are able to tolerate hormone withdrawal, especially if other DVT risk factors are present. If hormone therapy cannot be stopped, strong consideration should be given to higher-intensity DVT prophylaxis (e.g., chemoprophylaxis as opposed to mechanical measures) of longer duration—up to 28 days following general surgery and up to 35 days after orthopedic procedures.10

Perioperative Corticosteroids

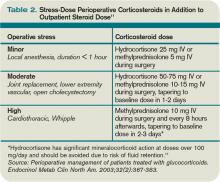

Corticosteroid therapy in excess of prednisone 5 mg/day or equivalent for more than five days in the 30 days preceding surgery might predispose patients to acute adrenal insufficiency in the perioperative period. Surgical procedures typically result in cortisol release of 50-150 mg/day, which returns to baseline within 48 hours.11 Therefore, the recommendation is to continue a patient’s baseline steroid dose and supplement it with stress-dose steroids tailored to the severity of operative stress (see Table 2, above).

Mineralocorticoid supplementation is not necessary, because endogenous production is not suppressed by corticosteroid therapy.11 Although a recent systematic review suggests that routine stress-dose steroids might not be indicated, high-quality prospective data are needed before abandoning this strategy due to complications of acute adrenal insufficiency compared to the risk of a brief corticosteroid burst.

Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

Nonselective cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitors reversibly decrease platelet aggregation only while the drug is present in the circulation and should be stopped one to three days before surgery due to risk of bleeding.

Selective COX-2 inhibitors do not significantly alter platelet aggregation and can be continued for opioid-sparing perioperative pain control.

Both COX-2-selective and nonselective inhibitors should be held if there are concerns for impaired renal function.

Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs (DMARDs) and Biological Response Modifiers (BRMs)

Methotrexate increases the risk of wound infections and dehiscence. However, this is offset by a decreased risk of post-operative disease flares with continued use. It can be continued unless the patient has medical comorbidities, advanced age, or chronic therapy with more than 10 mg/day of prednisone, in which case the drug should be stopped two weeks before surgery.12

Azathioprine, leflunomide, and sulfasalazine are renally cleared with a risk of myelosuppression; all of these medications should be stopped. Long half-life of leflunomide necessitates stopping it two weeks before surgery; azathioprine and sulfasalazine can be stopped one day in advance. The drugs can be restarted three days after surgery, assuming stable renal function.13

Anti-TNF-α (adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab), IL1 antagonist (anakinra), and anti-CD20 (rituximab) agents should be stopped one week before surgery and resumed 1-2 weeks afterward, unless risk of complications from disease flareup outweighs the concern for wound infections and dehiscence.14

Herbal Medicines

It is estimated that as much as a third of the U.S. population uses herbal medicines. These substances can result in perioperative hemodynamic instability (ephedra, ginseng, ma huang), hypoglycemia (ginseng), immunosuppression (echinacea, when taken for more than eight weeks), abnormal bleeding (garlic, ginkgo, ginseng), and prolongation of anesthesia (kava, St. John’s wort, valerian). All of these herbal medicine should be stopped one to two weeks before surgery.15,16

Back to the Case

The patient’s Carbidopa/Levodopa should be continued. Celecoxib can be continued if her renal function in stable. If aspirin is taken for a history of coronary artery disease or percutaneous coronary intervention, it should be continued, if possible. Clonidine should be continued or changed to a patch if an extended NPO period is anticipated. Ginkgo, lisinopril, and sulfasalazine should be stopped.

Hospitalization does not provide the luxury of stopping estradiol in advance, so it might be continued with chemical DVT prophylaxis for up to 35 days after surgery. The patient should receive 50-75 mg of IV hydrocortisone during surgery and an additional 25 mg the following day, in addition to her usual prednisone 10 mg/day. She can either receive half her usual NPH dose the morning of surgery with a 5% dextrose infusion in the operating room, or the NPH should be held altogether.

Bottom Line

Perioperative medication use should be tailored to each patient, balancing the risks and benefits of individual drugs. High-quality trials are needed to provide more robust clinical guidelines. TH

Dr. Levin is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado Denver.

References

- Fleisher LA, Beckman JA, Brown KA, et al. ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation and Care for Noncardiac Surgery: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation for Noncardiac Surgery): Developed in Collaboration With the American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Rhythm Society, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, and Society for Vascular Surgery. Circulation. 2007;116(17):1971-1996.

- Schouten O, Hoeks SE, Welten GM, et al. Effect of statin withdrawal on frequency of cardiac events after vascular surgery. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100(2):316-320.

- Spell NO III. Stopping and restarting medications in the perioperative period. Med Clin North Am. 2001;85(5):1117-1128.

- Rosenman DJ, McDonald FS, Ebbert JO, Erwin PJ, LaBella M, Montori VM. Clinical consequences of withholding versus administering renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system antagonists in the preoperative period. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(4):319-325.

- Arora P, Rajagopalam S, Ranjan R, et al. Preoperative use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/ angiotensin receptor blockers is associated with increased risk for acute kidney injury after cardiovascular surgery. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(5):1266-1273.

- Benedetto U, Sciarretta S, Roscitano A, et al. Preoperative Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and acute kidney injury after coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86(4):1160-1165.

- Pass SE, Simpson RW. Discontinuation and reinstitution of medications during the perioperative period. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004;61(9):899-914.

- Kohl BA, Schwartz S. Surgery in the patient with endocrine dysfunction. Med Clin North Am. 2009;93(5):1031-1047.

- Grady D, Wenger NK, Herrington D, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy increases risk for venous thromboembolic disease: The Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(9):689-696.

- Hirsh J, Guyatt G, Albers GW, Harrington R, Schünemann HJ; American College of Chest Physicians. Executive summary: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (8th edition). Chest. 2008;133(6 Suppl):71S-109S.

- Axelrod L. Perioperative management of patients treated with glucocorticoids. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2003;32(2):367-383.

- Marik PE, Varon J. Requirement of perioperative stress doses of corticosteroids: a systematic review of the literature. Arch Surg. 2008;143(12):1222-1226.

- Rosandich PA, Kelley JT III, Conn DL. Perioperative management of patients with rheumatoid arthritis in the era of biologic response modifiers. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2004;16(3):192-198.

- Saag KG, Teng GG, Patkar NM, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2008 recommendations for the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(6):762-784.

- Ang-Lee MK, Moss J, Yuan CS. Herbal medicines and perioperative care. JAMA. 2001;286(2):208-216.

- Hodges PJ, Kam PC. The peri-operative implications of herbal medicines. Anaesthesia. 2002;57(9):889-899.

Case

A 72-year-old female with multiple medical problems is admitted with a hip fracture. Surgery is scheduled in 48 hours. The patient’s home medications include aspirin, carbidopa/levodopa, celecoxib, clonidine, estradiol, ginkgo, lisinopril, NPH insulin, sulfasalazine, and prednisone 10 mg a day, which she has been taking for years. How should these and other medications be managed in the perioperative period?

Background

Perioperative management of chronic medications is a complex issue, as physicians are required to balance the beneficial and harmful effects of the individual drugs prescribed to their patients. On one hand, cessation of medications can result in decompensation of disease or withdrawal. On the other hand, continuation of drugs can alter metabolism of anesthetic agents, cause perioperative hemodynamic instability, or result in such post-operative complications as acute renal failure, bleeding, infection, and impaired wound healing.

Certain traits make it reasonable to continue medications during the perioperative period. A long elimination half-life or duration of action makes stopping some medications impractical as it takes four to five half-lives to completely clear the drug from the body; holding the drug for a few days around surgery will not appreciably affect its concentration. Stopping drugs that carry severe withdrawal symptoms can be impractical because of the need for lengthy tapers, which can delay surgery and result in decompensation of underlying disease.

Drugs with no significant interactions with anesthesia or risk of perioperative complications should be continued in order to avoid deterioration of the underlying disease. Conversely, drugs that interact with anesthesia or increase risk for complications should be stopped if this can be accomplished safely. Patient-specific factors should receive consideration, as the risk of complications has to be balanced against the danger of exacerbating the underlying disease.

Overview of the Data

The challenge in providing recommendations on perioperative medication management lies in a dearth of high-quality clinical trials. Thus, much of the information comes from case reports, expert opinion, and sound application of pharmacology.

Antiplatelet therapy: Nuances of perioperative antiplatelet therapy are beyond the scope of this review, but some general principles can be elucidated from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) 2007 perioperative guidelines.1 Management of antiplatelet therapy should be done in conjunction with the surgical team, as cardiovascular risk has to be weighed against bleeding risk.

Aspirin therapy should be continued in all patients with a history of coronary artery disease (CAD), balloon angioplasty, or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), unless the risk of bleeding complications is felt to exceed the cardioprotective benefits—for example, in some neurosurgical patients.1

Clopidogrel therapy is crucial for prevention of in-stent thrombosis (IST) following PCI because patients who experience IST suffer catastrophic myocardial infarctions with high mortality. Ideally, surgery should be delayed to permit completion of clopidogrel therapy—30 to 45 days after implantation of a bare-metal stent and 365 days after a drug-eluting stent. If surgery has to be performed sooner, guidelines recommend operating on dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel.1 Again, this course of treatment has to be balanced against the risk of hemorrhagic complications from surgery.

Both aspirin and clopidogrel irreversibly inhibit platelet aggregation. The recovery of normal coagulation involves formation of new platelets, which necessitates cessation of therapy for seven to 10 days before surgery. Platelet inhibition begins within minutes of restarting aspirin and within hours of taking clopidogrel, although attaining peak clopidogrel effect takes three to seven days, unless a loading dose is used.

Cardiovascular Drugs

Beta-blockers in the perioperative setting are a focus of an ongoing debate beyond the scope of this review (see “What Pre-Operative Cardiac Evaluation of Patients Undergoing Intermediate-Risk Surgery Is Most Effective?,” February 2008, p. 26). Given the current evidence and the latest ACC/AHA guidelines, it is still reasonable to continue therapy in patients who are already taking them to avoid precipitating cardiovascular events by withdrawal. Patients with increased cardiac risk, demonstrated by a Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI) score of ≥2 (see Table 1, p. 12), should be considered for beta-blocker therapy before surgery.1 In either case, the dose should be titrated to a heart rate <65 for optimal cardiac protection.1

Statins should be continued if the patient is taking them, especially because preoperative withdrawal has been associated with a 4.6-fold increase in troponin release and a 7.5-fold increased risk of myocardial infarction (MI) and cardiovascular death following major vascular surgery.2 Patients with increased cardiac risk— RCRI ≥1—can be considered for initiation of statin therapy before surgery, although the benefit of this intervention has not been examined in prospective studies.1

Amiodarone has an exceptionally long half-life of up to 142 days. It should be continued in the perioperative period.

Calcium channel blockers (CCBs) can be continued with no unpleasant perioperative hemodynamic effects.1 CCBs have potential cardioprotective benefits.

Clonidine withdrawal can result in severe rebound hypertension with reports of encephalopathy, stroke, and death. These effects are exacerbated by concomitant beta-blocker therapy. For this reason, if a patient is expected to be NPO for more than 12 hours, they should be converted to a clonidine patch 48-72 hours before surgery with concurrent tapering of the oral dose.3

Digoxin has a long half-life (up to 48 hours) and should be continued with monitoring of levels if there is a change in renal function.

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) have been associated with a 50% increased risk of hypotension requiring vasopressors during induction of anesthesia.4 However, it is worth mentioning that this finding has not been corroborated in other studies. A large retrospective cohort of cardiothoracic surgical patients found a 28% increased risk of post-operative acute renal failure (ARF) with both drug classes, although another cardiothoracic report published the same year demonstrated a 50% reduction in risk with ACEIs.5,6 Although the evidence of harm is not unequivocal, perioperative blood-pressure control can be achieved with other drugs without hemodynamic or renal risk, such as CCBs, and in most cases ACEIs/ARBs should be stopped one day before surgery.

Diuretics carry a risk of volume depletion and electrolyte derangements, and should be stopped once a patient becomes NPO. Excess volume is managed with as-needed intravenous formulations.

Drugs Acting on the Central Nervous System

The majority of central nervous system (CNS)-active drugs, including antiepileptics, antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, bupropion, gabapentin, lithium, mirtazapine, selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs and SNRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), and valproic acid, balance a low risk of perioperative complications against a significant potential for withdrawal and disease decompensation. Therefore, these medications should be continued.

Carbidopa/Levodopa should be continued because abrupt cessation can precipitate systemic withdrawal resembling serotonin syndrome and rapid deterioration of Parkinson’s symptoms.

Monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) therapy usually indicates refractory psychiatric illness, so these drugs should be continued to avoid decompensation. Importantly, MAOI-safe anesthesia without dextromethorphan, meperidine, epinephrine, or norepinephrine has to be used due to the risk of cardiovascular instability.7

Diabetic Drugs

Insulin therapy should be continued with adjustments. Glargine basal insulin has no peak and can be continued without changing the dose. Likewise, patients with insulin pumps can continue the usual basal rate. Short-acting insulin or such insulin mixes as 70/30 should be stopped four hours before surgery to avoid hypoglycemia. Intermediate-acting insulin (e.g., NPH) can be administered at half the usual dose the day of surgery with a perioperative 5% dextrose infusion. NPH should not be given the day of surgery if the dextrose infusion cannot be used.8

Incretins (exenatide, sitagliptin) rarely cause hypoglycemia in the absence of insulin and may be beneficial in controlling intraoperative hyperglycemia. Therefore, these medications can be continued.8

Thiazolidinediones (TZDs; pioglitazone, rosiglitazone) alter gene transcription with biological duration of action on the order of weeks and low risk of hypoglycemia, and should be continued.

Metformin carries an FDA black-box warning to discontinue therapy before any intravascular radiocontrast studies or surgical procedures due to the risk of severe lactic acidosis if renal failure develops. It should be stopped 24 hours before surgery and restarted at least 48-72 hours after. Normal renal function should be confirmed before restarting therapy.8

Sulfonylureas (glimepiride, glipizide, glyburide) carry a significant risk of hypoglycemia in a patient who is NPO; they should be stopped the night before surgery or before commencement of NPO status.

Hormones

Antithyroid drugs (methimazole, propylthiouracil) and levothyroxine should be continued, as they have no perioperative contraindications.

Oral contraceptives (OCPs), hormone replacement therapy (HRT), and raloxifene can increase the risk of DVT. The largest study on the topic was the HERS trial of postmenopausal women on estrogen/progesterone HRT. The authors reported a 4.9-fold increased risk of DVT for 90 days after surgery.9 Unfortunately, no information was provided on the types of surgery, or whether appropriate and consistent DVT prophylaxis was utilized. HERS authors also reported a 2.5-fold increased risk of DVT for at least 30 days after cessation of HRT.9

Given the data, it is reasonable to stop hormone therapy four weeks before surgery when prolonged immobilization is anticipated and patients are able to tolerate hormone withdrawal, especially if other DVT risk factors are present. If hormone therapy cannot be stopped, strong consideration should be given to higher-intensity DVT prophylaxis (e.g., chemoprophylaxis as opposed to mechanical measures) of longer duration—up to 28 days following general surgery and up to 35 days after orthopedic procedures.10

Perioperative Corticosteroids

Corticosteroid therapy in excess of prednisone 5 mg/day or equivalent for more than five days in the 30 days preceding surgery might predispose patients to acute adrenal insufficiency in the perioperative period. Surgical procedures typically result in cortisol release of 50-150 mg/day, which returns to baseline within 48 hours.11 Therefore, the recommendation is to continue a patient’s baseline steroid dose and supplement it with stress-dose steroids tailored to the severity of operative stress (see Table 2, above).

Mineralocorticoid supplementation is not necessary, because endogenous production is not suppressed by corticosteroid therapy.11 Although a recent systematic review suggests that routine stress-dose steroids might not be indicated, high-quality prospective data are needed before abandoning this strategy due to complications of acute adrenal insufficiency compared to the risk of a brief corticosteroid burst.

Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

Nonselective cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitors reversibly decrease platelet aggregation only while the drug is present in the circulation and should be stopped one to three days before surgery due to risk of bleeding.

Selective COX-2 inhibitors do not significantly alter platelet aggregation and can be continued for opioid-sparing perioperative pain control.

Both COX-2-selective and nonselective inhibitors should be held if there are concerns for impaired renal function.

Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs (DMARDs) and Biological Response Modifiers (BRMs)

Methotrexate increases the risk of wound infections and dehiscence. However, this is offset by a decreased risk of post-operative disease flares with continued use. It can be continued unless the patient has medical comorbidities, advanced age, or chronic therapy with more than 10 mg/day of prednisone, in which case the drug should be stopped two weeks before surgery.12

Azathioprine, leflunomide, and sulfasalazine are renally cleared with a risk of myelosuppression; all of these medications should be stopped. Long half-life of leflunomide necessitates stopping it two weeks before surgery; azathioprine and sulfasalazine can be stopped one day in advance. The drugs can be restarted three days after surgery, assuming stable renal function.13

Anti-TNF-α (adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab), IL1 antagonist (anakinra), and anti-CD20 (rituximab) agents should be stopped one week before surgery and resumed 1-2 weeks afterward, unless risk of complications from disease flareup outweighs the concern for wound infections and dehiscence.14

Herbal Medicines

It is estimated that as much as a third of the U.S. population uses herbal medicines. These substances can result in perioperative hemodynamic instability (ephedra, ginseng, ma huang), hypoglycemia (ginseng), immunosuppression (echinacea, when taken for more than eight weeks), abnormal bleeding (garlic, ginkgo, ginseng), and prolongation of anesthesia (kava, St. John’s wort, valerian). All of these herbal medicine should be stopped one to two weeks before surgery.15,16

Back to the Case

The patient’s Carbidopa/Levodopa should be continued. Celecoxib can be continued if her renal function in stable. If aspirin is taken for a history of coronary artery disease or percutaneous coronary intervention, it should be continued, if possible. Clonidine should be continued or changed to a patch if an extended NPO period is anticipated. Ginkgo, lisinopril, and sulfasalazine should be stopped.

Hospitalization does not provide the luxury of stopping estradiol in advance, so it might be continued with chemical DVT prophylaxis for up to 35 days after surgery. The patient should receive 50-75 mg of IV hydrocortisone during surgery and an additional 25 mg the following day, in addition to her usual prednisone 10 mg/day. She can either receive half her usual NPH dose the morning of surgery with a 5% dextrose infusion in the operating room, or the NPH should be held altogether.

Bottom Line

Perioperative medication use should be tailored to each patient, balancing the risks and benefits of individual drugs. High-quality trials are needed to provide more robust clinical guidelines. TH

Dr. Levin is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado Denver.

References

- Fleisher LA, Beckman JA, Brown KA, et al. ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation and Care for Noncardiac Surgery: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation for Noncardiac Surgery): Developed in Collaboration With the American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Rhythm Society, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, and Society for Vascular Surgery. Circulation. 2007;116(17):1971-1996.

- Schouten O, Hoeks SE, Welten GM, et al. Effect of statin withdrawal on frequency of cardiac events after vascular surgery. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100(2):316-320.

- Spell NO III. Stopping and restarting medications in the perioperative period. Med Clin North Am. 2001;85(5):1117-1128.

- Rosenman DJ, McDonald FS, Ebbert JO, Erwin PJ, LaBella M, Montori VM. Clinical consequences of withholding versus administering renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system antagonists in the preoperative period. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(4):319-325.

- Arora P, Rajagopalam S, Ranjan R, et al. Preoperative use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/ angiotensin receptor blockers is associated with increased risk for acute kidney injury after cardiovascular surgery. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(5):1266-1273.

- Benedetto U, Sciarretta S, Roscitano A, et al. Preoperative Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and acute kidney injury after coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86(4):1160-1165.

- Pass SE, Simpson RW. Discontinuation and reinstitution of medications during the perioperative period. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004;61(9):899-914.

- Kohl BA, Schwartz S. Surgery in the patient with endocrine dysfunction. Med Clin North Am. 2009;93(5):1031-1047.

- Grady D, Wenger NK, Herrington D, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy increases risk for venous thromboembolic disease: The Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(9):689-696.

- Hirsh J, Guyatt G, Albers GW, Harrington R, Schünemann HJ; American College of Chest Physicians. Executive summary: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (8th edition). Chest. 2008;133(6 Suppl):71S-109S.

- Axelrod L. Perioperative management of patients treated with glucocorticoids. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2003;32(2):367-383.

- Marik PE, Varon J. Requirement of perioperative stress doses of corticosteroids: a systematic review of the literature. Arch Surg. 2008;143(12):1222-1226.

- Rosandich PA, Kelley JT III, Conn DL. Perioperative management of patients with rheumatoid arthritis in the era of biologic response modifiers. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2004;16(3):192-198.

- Saag KG, Teng GG, Patkar NM, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2008 recommendations for the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(6):762-784.

- Ang-Lee MK, Moss J, Yuan CS. Herbal medicines and perioperative care. JAMA. 2001;286(2):208-216.

- Hodges PJ, Kam PC. The peri-operative implications of herbal medicines. Anaesthesia. 2002;57(9):889-899.

Case

A 72-year-old female with multiple medical problems is admitted with a hip fracture. Surgery is scheduled in 48 hours. The patient’s home medications include aspirin, carbidopa/levodopa, celecoxib, clonidine, estradiol, ginkgo, lisinopril, NPH insulin, sulfasalazine, and prednisone 10 mg a day, which she has been taking for years. How should these and other medications be managed in the perioperative period?

Background

Perioperative management of chronic medications is a complex issue, as physicians are required to balance the beneficial and harmful effects of the individual drugs prescribed to their patients. On one hand, cessation of medications can result in decompensation of disease or withdrawal. On the other hand, continuation of drugs can alter metabolism of anesthetic agents, cause perioperative hemodynamic instability, or result in such post-operative complications as acute renal failure, bleeding, infection, and impaired wound healing.

Certain traits make it reasonable to continue medications during the perioperative period. A long elimination half-life or duration of action makes stopping some medications impractical as it takes four to five half-lives to completely clear the drug from the body; holding the drug for a few days around surgery will not appreciably affect its concentration. Stopping drugs that carry severe withdrawal symptoms can be impractical because of the need for lengthy tapers, which can delay surgery and result in decompensation of underlying disease.

Drugs with no significant interactions with anesthesia or risk of perioperative complications should be continued in order to avoid deterioration of the underlying disease. Conversely, drugs that interact with anesthesia or increase risk for complications should be stopped if this can be accomplished safely. Patient-specific factors should receive consideration, as the risk of complications has to be balanced against the danger of exacerbating the underlying disease.

Overview of the Data

The challenge in providing recommendations on perioperative medication management lies in a dearth of high-quality clinical trials. Thus, much of the information comes from case reports, expert opinion, and sound application of pharmacology.

Antiplatelet therapy: Nuances of perioperative antiplatelet therapy are beyond the scope of this review, but some general principles can be elucidated from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) 2007 perioperative guidelines.1 Management of antiplatelet therapy should be done in conjunction with the surgical team, as cardiovascular risk has to be weighed against bleeding risk.

Aspirin therapy should be continued in all patients with a history of coronary artery disease (CAD), balloon angioplasty, or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), unless the risk of bleeding complications is felt to exceed the cardioprotective benefits—for example, in some neurosurgical patients.1

Clopidogrel therapy is crucial for prevention of in-stent thrombosis (IST) following PCI because patients who experience IST suffer catastrophic myocardial infarctions with high mortality. Ideally, surgery should be delayed to permit completion of clopidogrel therapy—30 to 45 days after implantation of a bare-metal stent and 365 days after a drug-eluting stent. If surgery has to be performed sooner, guidelines recommend operating on dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel.1 Again, this course of treatment has to be balanced against the risk of hemorrhagic complications from surgery.

Both aspirin and clopidogrel irreversibly inhibit platelet aggregation. The recovery of normal coagulation involves formation of new platelets, which necessitates cessation of therapy for seven to 10 days before surgery. Platelet inhibition begins within minutes of restarting aspirin and within hours of taking clopidogrel, although attaining peak clopidogrel effect takes three to seven days, unless a loading dose is used.

Cardiovascular Drugs

Beta-blockers in the perioperative setting are a focus of an ongoing debate beyond the scope of this review (see “What Pre-Operative Cardiac Evaluation of Patients Undergoing Intermediate-Risk Surgery Is Most Effective?,” February 2008, p. 26). Given the current evidence and the latest ACC/AHA guidelines, it is still reasonable to continue therapy in patients who are already taking them to avoid precipitating cardiovascular events by withdrawal. Patients with increased cardiac risk, demonstrated by a Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI) score of ≥2 (see Table 1, p. 12), should be considered for beta-blocker therapy before surgery.1 In either case, the dose should be titrated to a heart rate <65 for optimal cardiac protection.1

Statins should be continued if the patient is taking them, especially because preoperative withdrawal has been associated with a 4.6-fold increase in troponin release and a 7.5-fold increased risk of myocardial infarction (MI) and cardiovascular death following major vascular surgery.2 Patients with increased cardiac risk— RCRI ≥1—can be considered for initiation of statin therapy before surgery, although the benefit of this intervention has not been examined in prospective studies.1

Amiodarone has an exceptionally long half-life of up to 142 days. It should be continued in the perioperative period.

Calcium channel blockers (CCBs) can be continued with no unpleasant perioperative hemodynamic effects.1 CCBs have potential cardioprotective benefits.

Clonidine withdrawal can result in severe rebound hypertension with reports of encephalopathy, stroke, and death. These effects are exacerbated by concomitant beta-blocker therapy. For this reason, if a patient is expected to be NPO for more than 12 hours, they should be converted to a clonidine patch 48-72 hours before surgery with concurrent tapering of the oral dose.3

Digoxin has a long half-life (up to 48 hours) and should be continued with monitoring of levels if there is a change in renal function.

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) have been associated with a 50% increased risk of hypotension requiring vasopressors during induction of anesthesia.4 However, it is worth mentioning that this finding has not been corroborated in other studies. A large retrospective cohort of cardiothoracic surgical patients found a 28% increased risk of post-operative acute renal failure (ARF) with both drug classes, although another cardiothoracic report published the same year demonstrated a 50% reduction in risk with ACEIs.5,6 Although the evidence of harm is not unequivocal, perioperative blood-pressure control can be achieved with other drugs without hemodynamic or renal risk, such as CCBs, and in most cases ACEIs/ARBs should be stopped one day before surgery.

Diuretics carry a risk of volume depletion and electrolyte derangements, and should be stopped once a patient becomes NPO. Excess volume is managed with as-needed intravenous formulations.

Drugs Acting on the Central Nervous System

The majority of central nervous system (CNS)-active drugs, including antiepileptics, antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, bupropion, gabapentin, lithium, mirtazapine, selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs and SNRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), and valproic acid, balance a low risk of perioperative complications against a significant potential for withdrawal and disease decompensation. Therefore, these medications should be continued.

Carbidopa/Levodopa should be continued because abrupt cessation can precipitate systemic withdrawal resembling serotonin syndrome and rapid deterioration of Parkinson’s symptoms.

Monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) therapy usually indicates refractory psychiatric illness, so these drugs should be continued to avoid decompensation. Importantly, MAOI-safe anesthesia without dextromethorphan, meperidine, epinephrine, or norepinephrine has to be used due to the risk of cardiovascular instability.7

Diabetic Drugs

Insulin therapy should be continued with adjustments. Glargine basal insulin has no peak and can be continued without changing the dose. Likewise, patients with insulin pumps can continue the usual basal rate. Short-acting insulin or such insulin mixes as 70/30 should be stopped four hours before surgery to avoid hypoglycemia. Intermediate-acting insulin (e.g., NPH) can be administered at half the usual dose the day of surgery with a perioperative 5% dextrose infusion. NPH should not be given the day of surgery if the dextrose infusion cannot be used.8

Incretins (exenatide, sitagliptin) rarely cause hypoglycemia in the absence of insulin and may be beneficial in controlling intraoperative hyperglycemia. Therefore, these medications can be continued.8

Thiazolidinediones (TZDs; pioglitazone, rosiglitazone) alter gene transcription with biological duration of action on the order of weeks and low risk of hypoglycemia, and should be continued.

Metformin carries an FDA black-box warning to discontinue therapy before any intravascular radiocontrast studies or surgical procedures due to the risk of severe lactic acidosis if renal failure develops. It should be stopped 24 hours before surgery and restarted at least 48-72 hours after. Normal renal function should be confirmed before restarting therapy.8

Sulfonylureas (glimepiride, glipizide, glyburide) carry a significant risk of hypoglycemia in a patient who is NPO; they should be stopped the night before surgery or before commencement of NPO status.

Hormones

Antithyroid drugs (methimazole, propylthiouracil) and levothyroxine should be continued, as they have no perioperative contraindications.

Oral contraceptives (OCPs), hormone replacement therapy (HRT), and raloxifene can increase the risk of DVT. The largest study on the topic was the HERS trial of postmenopausal women on estrogen/progesterone HRT. The authors reported a 4.9-fold increased risk of DVT for 90 days after surgery.9 Unfortunately, no information was provided on the types of surgery, or whether appropriate and consistent DVT prophylaxis was utilized. HERS authors also reported a 2.5-fold increased risk of DVT for at least 30 days after cessation of HRT.9

Given the data, it is reasonable to stop hormone therapy four weeks before surgery when prolonged immobilization is anticipated and patients are able to tolerate hormone withdrawal, especially if other DVT risk factors are present. If hormone therapy cannot be stopped, strong consideration should be given to higher-intensity DVT prophylaxis (e.g., chemoprophylaxis as opposed to mechanical measures) of longer duration—up to 28 days following general surgery and up to 35 days after orthopedic procedures.10

Perioperative Corticosteroids

Corticosteroid therapy in excess of prednisone 5 mg/day or equivalent for more than five days in the 30 days preceding surgery might predispose patients to acute adrenal insufficiency in the perioperative period. Surgical procedures typically result in cortisol release of 50-150 mg/day, which returns to baseline within 48 hours.11 Therefore, the recommendation is to continue a patient’s baseline steroid dose and supplement it with stress-dose steroids tailored to the severity of operative stress (see Table 2, above).

Mineralocorticoid supplementation is not necessary, because endogenous production is not suppressed by corticosteroid therapy.11 Although a recent systematic review suggests that routine stress-dose steroids might not be indicated, high-quality prospective data are needed before abandoning this strategy due to complications of acute adrenal insufficiency compared to the risk of a brief corticosteroid burst.

Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

Nonselective cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitors reversibly decrease platelet aggregation only while the drug is present in the circulation and should be stopped one to three days before surgery due to risk of bleeding.

Selective COX-2 inhibitors do not significantly alter platelet aggregation and can be continued for opioid-sparing perioperative pain control.

Both COX-2-selective and nonselective inhibitors should be held if there are concerns for impaired renal function.

Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs (DMARDs) and Biological Response Modifiers (BRMs)

Methotrexate increases the risk of wound infections and dehiscence. However, this is offset by a decreased risk of post-operative disease flares with continued use. It can be continued unless the patient has medical comorbidities, advanced age, or chronic therapy with more than 10 mg/day of prednisone, in which case the drug should be stopped two weeks before surgery.12

Azathioprine, leflunomide, and sulfasalazine are renally cleared with a risk of myelosuppression; all of these medications should be stopped. Long half-life of leflunomide necessitates stopping it two weeks before surgery; azathioprine and sulfasalazine can be stopped one day in advance. The drugs can be restarted three days after surgery, assuming stable renal function.13

Anti-TNF-α (adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab), IL1 antagonist (anakinra), and anti-CD20 (rituximab) agents should be stopped one week before surgery and resumed 1-2 weeks afterward, unless risk of complications from disease flareup outweighs the concern for wound infections and dehiscence.14

Herbal Medicines

It is estimated that as much as a third of the U.S. population uses herbal medicines. These substances can result in perioperative hemodynamic instability (ephedra, ginseng, ma huang), hypoglycemia (ginseng), immunosuppression (echinacea, when taken for more than eight weeks), abnormal bleeding (garlic, ginkgo, ginseng), and prolongation of anesthesia (kava, St. John’s wort, valerian). All of these herbal medicine should be stopped one to two weeks before surgery.15,16

Back to the Case

The patient’s Carbidopa/Levodopa should be continued. Celecoxib can be continued if her renal function in stable. If aspirin is taken for a history of coronary artery disease or percutaneous coronary intervention, it should be continued, if possible. Clonidine should be continued or changed to a patch if an extended NPO period is anticipated. Ginkgo, lisinopril, and sulfasalazine should be stopped.

Hospitalization does not provide the luxury of stopping estradiol in advance, so it might be continued with chemical DVT prophylaxis for up to 35 days after surgery. The patient should receive 50-75 mg of IV hydrocortisone during surgery and an additional 25 mg the following day, in addition to her usual prednisone 10 mg/day. She can either receive half her usual NPH dose the morning of surgery with a 5% dextrose infusion in the operating room, or the NPH should be held altogether.

Bottom Line

Perioperative medication use should be tailored to each patient, balancing the risks and benefits of individual drugs. High-quality trials are needed to provide more robust clinical guidelines. TH

Dr. Levin is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado Denver.

References

- Fleisher LA, Beckman JA, Brown KA, et al. ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation and Care for Noncardiac Surgery: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation for Noncardiac Surgery): Developed in Collaboration With the American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Rhythm Society, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, and Society for Vascular Surgery. Circulation. 2007;116(17):1971-1996.

- Schouten O, Hoeks SE, Welten GM, et al. Effect of statin withdrawal on frequency of cardiac events after vascular surgery. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100(2):316-320.

- Spell NO III. Stopping and restarting medications in the perioperative period. Med Clin North Am. 2001;85(5):1117-1128.

- Rosenman DJ, McDonald FS, Ebbert JO, Erwin PJ, LaBella M, Montori VM. Clinical consequences of withholding versus administering renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system antagonists in the preoperative period. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(4):319-325.

- Arora P, Rajagopalam S, Ranjan R, et al. Preoperative use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/ angiotensin receptor blockers is associated with increased risk for acute kidney injury after cardiovascular surgery. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(5):1266-1273.

- Benedetto U, Sciarretta S, Roscitano A, et al. Preoperative Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and acute kidney injury after coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86(4):1160-1165.

- Pass SE, Simpson RW. Discontinuation and reinstitution of medications during the perioperative period. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004;61(9):899-914.

- Kohl BA, Schwartz S. Surgery in the patient with endocrine dysfunction. Med Clin North Am. 2009;93(5):1031-1047.

- Grady D, Wenger NK, Herrington D, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy increases risk for venous thromboembolic disease: The Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(9):689-696.

- Hirsh J, Guyatt G, Albers GW, Harrington R, Schünemann HJ; American College of Chest Physicians. Executive summary: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (8th edition). Chest. 2008;133(6 Suppl):71S-109S.

- Axelrod L. Perioperative management of patients treated with glucocorticoids. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2003;32(2):367-383.

- Marik PE, Varon J. Requirement of perioperative stress doses of corticosteroids: a systematic review of the literature. Arch Surg. 2008;143(12):1222-1226.

- Rosandich PA, Kelley JT III, Conn DL. Perioperative management of patients with rheumatoid arthritis in the era of biologic response modifiers. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2004;16(3):192-198.

- Saag KG, Teng GG, Patkar NM, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2008 recommendations for the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(6):762-784.

- Ang-Lee MK, Moss J, Yuan CS. Herbal medicines and perioperative care. JAMA. 2001;286(2):208-216.

- Hodges PJ, Kam PC. The peri-operative implications of herbal medicines. Anaesthesia. 2002;57(9):889-899.

In the Literature

In This Edition

Literature at a Glance

A guide to this month’s studies

- CPOE and quality outcomes

- Outcomes of standardized management of endocarditis

- Effect of tPA three to 4.5 hours after stroke onset

- Failure to notify patients of significant test results

- PFO repair and stroke rate

- Predictors of delay in defibrillation for in-hospital arrest

- H. pylori eradication and risk of future gastric cancer

- Bleeding risk with fondaparinux vs. enoxaparin in ACS

- Perceptions of physician ability to predict medical futility

CPOE Is Associated with Improvement in Quality Measures

Clinical question: Is computerized physician order entry (CPOE) associated with improved outcomes across a large, nationally representative sample of hospitals?

Background: Several single-institution studies suggest CPOE leads to better outcomes in quality measures for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, and pneumonia as defined by the Hospital Quality Alliance (HQA) initiative, led by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Little systematic information is known about the effects of CPOE on quality of care.

Study design: Cross-sectional study.

Setting: The Health Information Management System Society (HIMSS) analytics database of 3,364 hospitals throughout the U.S.

Synopsis: Of the hospitals that reported CPOE utilization to HIMSS, 264 (7.8%) fully implement CPOE throughout their institutions. These CPOE hospitals outperformed their peers on five of 11 quality measures related to ordering medications, and in one of nine non-medication-related measures. No difference was noted in the other measures, except CPOE hospitals were less effective at providing antibiotics within four hours of pneumonia diagnosis. Hospitals that utilized CPOE were generally academic, larger, and nonprofit. After adjusting for these differences, benefits were still preserved.

The authors indicate that the lack of systematic outperformance by CPOE hospitals in all 20 of the quality categories inherently suggests that other factors (e.g., concomitant QI efforts) are not affecting these results. Given the observational nature of this study, no causal relationship can be established between CPOE and the observed benefits. CPOE might represent the commitment of certain hospitals to quality measures, but further study is needed.

Bottom line: Enhanced compliance in several CMS-established quality measures is seen in hospitals that utilize CPOE throughout their institutions.

Citation: Yu FB, Menachemi N, Berner ES, Allison JJ, Weissman NW, Houston TK. Full implementation of computerized physician order entry and medication-related quality outcomes: a study of 3,364 hospitals. Am J Med Qual. 2009;24(4):278-286.

Standardized Management of Endocarditis Leads to Significant Mortality Benefit

Clinical question: Does a standardized approach to the treatment of infective endocarditis reduce mortality and morbidity?

Background: Despite epidemiological changes to the inciting bacteria and improvements in available antibiotics, mortality and morbidity associated with endocarditis remain high. The contribution of inconsistent or inaccurate treatment of endocarditis is unclear.

Study design: Case series with historical controls from 1994 to 2001, compared with protocolized patients from 2002 to 2006.

Setting: Single teaching tertiary-care hospital in France.

Synopsis: The authors established a diagnostic protocol for infectious endocarditis from 1994 to 2001 (period 1) and established a treatment protocol from 2002 to 2006 (period 2). Despite a statistically significant sicker population (older, higher comorbidities, higher coagulase-negative staphylococcal infections, and fewer healthy valves), the period-2 patients had a dramatically lower mortality rate of 8.2% (P<0.001), compared with 18.5% in period-1 patients. Fewer episodes of renal failure, organ failure, and deaths associated with embolism were noted in period 2.

Whether these results are due to more frequent care, more aggressive care (patients were “summoned” if they did not show for appointments), standardized medication and surgical options, or the effects of long-term collaboration, these results appear durable, remarkable, and reproducible.

This study is limited by its lack of randomization and extensive time frame, with concomitant changes in medical treatment and observed infectious organisms.

Bottom line: Implementation of a standardized approach to endocarditis has significant benefit on mortality and morbidity.

Citation: Botelho-Nevers E, Thuny F, Casalta JP, et al. Dramatic reduction in infective endocarditis-related mortality with a management-based approach. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(14):1290-1298.

Treatment with tPA in the Three- to 4.5-Hour Time Window after Stroke Is Beneficial

Clinical question: What is the effect of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) on outcomes in patients treated in the three- to 4.5-hour window after stroke?

Background: The third European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study 3 (ECASS-3) demonstrated benefit of treatment of acute stroke with tPA in the three- to 4.5-hour time window. Prior studies, however, did not show superiority of tPA over placebo, and there is a lack of a confirmatory randomized, controlled trial of tPA in this time frame.

Study design: Meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials.

Setting: Four studies involving 1,622 patients who were treated with intravenous tPA for acute ischemic stroke from three to 4.5 hours after stroke compared with placebo.

Synopsis: Of the randomized, controlled trials of intravenous tPA for treatment of acute ischemic stroke from three to 4.5 hours after stroke, four trials (ECASS-1, ECASS-2, ECASS-3, and ATLANTIS) were included in the analysis. Treatment with tPA in the three- to 4.5-hour time window is associated with increased favorable outcomes based on the global outcome measure (OR 1.31; 95% CI: 1.10-1.56, P=0.002) and the modified Rankin Scale (OR 1.31; 95% CI: 1.07-1.59, P=0.01), compared with placebo. The 90-day mortality rate was not significantly different between the treatment and placebo groups (OR 1.04; 95% CI 0.75-1.43, P=0.83).

Due to the relatively high dose of tPA (1.1 mg/kg) administered in the ECASS-1 trial, a separate meta-analysis looking at the other three trials (tPA dose of 0.9 mg/kg) was conducted, and the favorable outcome with tPA remained.

Bottom line: Treatment of acute ischemic stroke with tPA in the three- to 4.5-hour time window results in an increased rate of favorable functional outcomes without a significant difference in mortality.

Citation: Lansberg MG, Bluhmki E, Thijs VN. Efficacy and safety of tissue plasminogen activator 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke: a metaanalysis. Stroke. 2009;40(7):2438-2441.

Outpatients Often Are Not Notified of Clinically Significant Test Results

Clinical question: How frequently do primary-care physicians (PCPs) fail to inform patients of clinically significant outpatient test results?

Background: Diagnostic errors are the most common cause of malpractice claims in the U.S. It is unclear how often providers fail to either inform patients of abnormal test results or document that patients have been notified.

Study design: Retrospective chart review.

Setting: Twenty-three primary-care practices: 19 private, four academic.

Synopsis: More than 5,400 charts were reviewed, and 1,889 abnormal test results were identified in this study. Failure to inform or document notification was identified in 135 cases (7.1%). The failure rates in the practices ranged from 0.0% to 26.2%. Practices with the best processes for managing test results had the lowest failure rates; these processes included: all results being routed to the responsible physician; the physician signing off on all results; the practice informing patients of all results, both normal and abnormal; documenting when the patient is informed; and instructing patients to call if not notified of test results within a certain time interval.

Limitations of this study include the potential of over- or underreporting of failures to inform as a chart review was used, and only practices that agreed to participate were included.

Bottom line: Failure to notify outpatients of test results is common but can be minimized by creating a systematic management of test results that include best practices.

Citation: Casalino LP, Dunham D, Chin MH, et al. Frequency of failure to inform patients of clinically significant outpatient test results. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(12):1123-1129.

Repair of Incidental PFO Discovered During Cardiothoracic Surgery Repair Increases Postoperative Stroke Risk

Clinical question: What is the impact of closing incidentally discovered patent foramen ovale (PFO) defects during cardiothoracic surgery?

Background: PFO’s role in cryptogenic stroke remains controversial. Incidental PFO is commonly detected by transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) during cardiothoracic surgery. Routine PFO closure has been recommended when almost no alteration of the surgical plan is required.

Study design: Retrospective chart review.

Setting: The Cleveland Clinic.

Synopsis: Between 1995 and 2006, 13,092 patients undergoing cardiothoracic surgery had TEE data with no previous diagnosis of PFO, but the review found that 2,277 (17%) had PFO discovered intraoperatively. Of these, 639 (28%) had the PFO repaired.

Patients with an intraoperative diagnosis of PFO had similar rates of in-hospital stroke and hospital death compared with those without PFO. Patients who had their PFO repaired had a greater in-hospital stroke risk (2.8% vs. 1.2%; P=0.04) compared with those with a non-repaired PFO, representing nearly 2.5 times greater odds of having an in-hospital stroke. No other difference was noted in perioperative outcomes for patients who underwent intraoperative repair compared with those who did not, including risk of in-hospital death, hospital length of stay, ICU length of stay, and time on cardiopulmonary bypass. Long-term analysis demonstrated that PFO repair was associated with no survival difference.

The study is limited by its retrospective nature.

Bottom line: Routine surgical closure of incidental PFO detected during intraoperative imaging should be discouraged.

Citation: Krasuski RA, Hart SA, Allen D, et al. Prevalence and repair of interoperatively diagnosed patent foramen ovale and association with perioperative outcomes and long-term survival. JAMA. 2009;302(3):290-297.

Hospital-Level Differences Are Strong Predictors of Time to Defibrillation Delay In Cardiac Arrest

Clinical question: What are the predictors of delay in the time to defibrillation after in-hospital cardiac arrest?

Background: Thirty percent of in-hospital cardiac arrests from ventricular arrhythmias are not treated within the American Heart Association’s recommendation of two minutes. This delay is associated with a 50% lower rate of in-hospital survival. Exploring the hospital-level variation in delays to defibrillation is a critical step toward sharing the best practices.

Study design: Retrospective review of registry data.

Setting: The National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (NRCPR) survey of 200 acute-care, nonpediatric hospitals.

Synopsis: The registry identified 7,479 patients who experienced cardiac arrest from ventricular tachycardia or pulseless ventricular fibrillation. The primary outcome was the hospital rate of delayed defibrillation (time to defibrillation > two minutes), which ranged from 2% to 51%.

Time to defibrillation was found to be a major predictor of survival after a cardiac arrest. Only bed volume and arrest location were associated with differences in rates of delayed defibrillation (lower rates in larger hospitals and in ICUs). The variability was not due to differences in patient characteristics, but was due to hospital-level effects. Academic status, geographical location, arrest volume, and daily admission volume did not affect the time to defibrillation.

The study was able to identify only a few facility characteristics that account for the variability between hospitals in the rate of delayed defibrillation. The study emphasizes the need for new approaches to identifying hospital innovations in process-of-care measures that are associated with improved performance in defibrillation times.

Bottom Line: Future research is needed to better understand the reason for the wide variation between hospitals in the rate of delayed defibrillation after in-hospital cardiac arrest.

Citation: Chan PS, Nichol G, Krumholz HM, Spertus JA, Nallamothu BK; American Heart Association National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (NRCPR) Investigators. Hospital variation in time to defibrillation after in-hospital cardiac arrest. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(14):1265-1273.

Treating for H. Pylori Reduces the Risk for Developing Gastric Cancer in High-Risk Patients

Clinical question: In patients with high-baseline incidence of gastric cancer, does H. pylori eradication reduce the risk for developing gastric cancer?

Background: Gastric cancer remains a major health problem in Asia. The link of H. pylori and gastric cancer has been established, but it remains unclear whether treatment for H. pylori is effective primary prevention for the development of gastric cancer.

Study design: Meta-analysis of six studies.

Setting: All but one trial was performed in Asia.

Synopsis: Seven studies met inclusion criteria, one of which was excluded due to heterogeneity. The six remaining studies were pooled, with 37 of 3,388 (1.1%) treated patients developing a new gastric cancer, compared with 56 of 3,307 (1.7%) patients who received placebo or were in the control group (RR 0.65; 0.43-0.98). Most patients received gastric biopsy prior to enrollment, and most of those demonstrated gastric atrophy or intestinal metaplasia.

These patients, despite more advanced precancerous pathology findings, still benefited from eradication. The seventh study, which was excluded, enrolled patients with early gastric cancer; these patients still benefited from H. pylori eradication and, when included in the meta-analysis, the RR was even lower, 0.57 (0.49-0.81).

Only two trials were double-blinded, but all of the studies employed the same definition of gastric cancer and held to excellent data reporting standards. This study encourages screening and treatment in high-risk patients given the widespread incidence of H. pylori.

Bottom Line: Treatment of H. pylori reduces the risk of gastric cancer in high-risk patients.

Citation: Fuccio L, Zagari RM, Eusebi LH, et al. Meta-analysis: can Helicobacter pylori eradication treatment reduce the risk for gastric cancer? Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(2):121-128.

Patients on Anti-Platelet Agents with Acute Coronary Syndrome Have a Lower Bleeding Risk When Treated with Fondaparinux

Clinical question: Is there a difference in bleeding risk with fondaparinux and enoxaparin when used with GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors or thienopyridines in NSTEMI-ACS?

Background: The OASIS 5 study reported a 50% reduction in severe bleeding when comparing fondaparinux to enoxaparin in ACS while maintaining a similar efficacy. This subgroup analysis was performed to evaluate whether reduced bleeding risk with fondaparinux remains in patients treated with additional anti-platelet agents.

Study design: Subgroup analysis of a large, multicenter, randomized, double-blind trial.

Setting: Acute-care hospitals in North America, Eastern and Western Europe, Latin America, Australia, and Asia.

Synopsis: Patients with NSTE-ACS received either fondaparinux or enoxaparin and were treated with GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors or thienopyridines at the discretion of their physician. At 30 days, the fondaparinux group had similar efficacy and decreased bleeding risk in both the GPIIb/IIIa and the thienopyridine groups. Of the 3,630 patients in the GPIIb/IIIa group, the risk for major bleeding with fondaparinux was 5.2%, whereas the risk with enoxaparin was 8.3% (HR 0.61; P<0.001) compared with enoxaparin. Of the 1,352 patients treated with thienopyridines, the risk for major bleeding with fondaparinux was 3.4%, whereas the risk with enoxaparin was 5.4% (HR 0.62; P<0.001).

Bottom Line: This subgroup analysis suggests there are less-severe bleeding complications in patients treated with fondaparinux when compared with enoxaparin in the setting of cotreatment with GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors, thienopyridines, or both.

Citation: Jolly SS, Faxon DP, Fox KA, et al. Efficacy and safety of fondaparinux versus enoxaparin in patients with acute coronary syndromes treated with glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors of thienopyridines: results from the OASIS 5 (Fifth Organization to Assess Strategies in Ischemic Syndromes) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(5):468-476.

Surrogate Decision-Makers Frequently Doubt Clinicians’ Ability to Predict Medical Futility

Clinical question: What attitudes do surrogate decision-makers hold toward clinicians’ predictions of medical futility in critically-ill patients?

Background: The clinical judgment of medical futility leading to the withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment—despite the objections of surrogate decision-makers—is controversial. Very little is known about how surrogate decision-makers view the futility rationale when physicians suggest limiting the use of life-sustaining treatment.

Study design: Multicenter, mixed, qualitative and quantitative study.

Setting: Three ICUs in three different California hospitals from 2006 to 2007.

Synopsis: Semi-structured interviews of surrogate decision-makers for 50 incapacitated, critically-ill patients were performed to ascertain their beliefs about medical futility in response to hypothetical situations. Of the surrogates surveyed, 64% expressed doubt about physicians’ futility predictions.

The interviewees gave four main reasons for their doubts. Two reasons not previously described were doubts about the accuracy of physicians’ predictions and the need for surrogates to see futility themselves. Previously described sources of conflict included a misunderstanding about prognosis and religious-based objections. Surrogates with religious objections were more likely to request continuation of life-sustaining treatments than those with secular or experiential objections (OR 4; 95% CI 1.2-14.0; P=0.03). Nearly a third (32%) of surrogates elected to continue life support with a <1% survival estimate; 18% elected to continue life support when physicians thought there was no chance of survival.

This study has several limitations: a small sample size, the use of hypothetical situations, and the inability to assess attitudes as they change over time.

Bottom line: The nature of surrogate decision-makers’ doubts about medical futility can help predict whether they accept predictions of medical futility from physicians.

Citation: Zier LS, Burack JH, Micco G, Chipman AK, Frank JA, White DB. Surrogate decision makers’ responses to physicians’ predictions of medical futility. Chest. 2009;136:110-117. TH

In This Edition

Literature at a Glance

A guide to this month’s studies

- CPOE and quality outcomes

- Outcomes of standardized management of endocarditis

- Effect of tPA three to 4.5 hours after stroke onset

- Failure to notify patients of significant test results

- PFO repair and stroke rate

- Predictors of delay in defibrillation for in-hospital arrest

- H. pylori eradication and risk of future gastric cancer

- Bleeding risk with fondaparinux vs. enoxaparin in ACS

- Perceptions of physician ability to predict medical futility

CPOE Is Associated with Improvement in Quality Measures

Clinical question: Is computerized physician order entry (CPOE) associated with improved outcomes across a large, nationally representative sample of hospitals?

Background: Several single-institution studies suggest CPOE leads to better outcomes in quality measures for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, and pneumonia as defined by the Hospital Quality Alliance (HQA) initiative, led by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Little systematic information is known about the effects of CPOE on quality of care.

Study design: Cross-sectional study.

Setting: The Health Information Management System Society (HIMSS) analytics database of 3,364 hospitals throughout the U.S.

Synopsis: Of the hospitals that reported CPOE utilization to HIMSS, 264 (7.8%) fully implement CPOE throughout their institutions. These CPOE hospitals outperformed their peers on five of 11 quality measures related to ordering medications, and in one of nine non-medication-related measures. No difference was noted in the other measures, except CPOE hospitals were less effective at providing antibiotics within four hours of pneumonia diagnosis. Hospitals that utilized CPOE were generally academic, larger, and nonprofit. After adjusting for these differences, benefits were still preserved.

The authors indicate that the lack of systematic outperformance by CPOE hospitals in all 20 of the quality categories inherently suggests that other factors (e.g., concomitant QI efforts) are not affecting these results. Given the observational nature of this study, no causal relationship can be established between CPOE and the observed benefits. CPOE might represent the commitment of certain hospitals to quality measures, but further study is needed.

Bottom line: Enhanced compliance in several CMS-established quality measures is seen in hospitals that utilize CPOE throughout their institutions.

Citation: Yu FB, Menachemi N, Berner ES, Allison JJ, Weissman NW, Houston TK. Full implementation of computerized physician order entry and medication-related quality outcomes: a study of 3,364 hospitals. Am J Med Qual. 2009;24(4):278-286.

Standardized Management of Endocarditis Leads to Significant Mortality Benefit

Clinical question: Does a standardized approach to the treatment of infective endocarditis reduce mortality and morbidity?

Background: Despite epidemiological changes to the inciting bacteria and improvements in available antibiotics, mortality and morbidity associated with endocarditis remain high. The contribution of inconsistent or inaccurate treatment of endocarditis is unclear.

Study design: Case series with historical controls from 1994 to 2001, compared with protocolized patients from 2002 to 2006.

Setting: Single teaching tertiary-care hospital in France.