User login

History of Abuse May Worsen Disease Burden in Migraine

Key clinical point: Patients with migraine and a history of abuse had a greater migraine burden than those without a history of abuse, with this association being mediated by depression and anxiety.

Major findings: Patients with migraine who did vs did not have a history of abuse had significantly higher migraine-specific disability (68 vs 49), subjective cognitive impairment (10 vs 7), and pain interference (65 vs 62.5) scores, as well as greater overall work impairment (47.6% vs 38.6%) and activity impairment (49.3% vs 39.3%; all P < .001). Depression and anxiety mediated the association between history of abuse and migraine burden.

Study details: This cross-sectional study included 866 patients with migraine from the American Registry for Migraine Research, of whom 316 (36.5 %) had a history of abuse.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the American Migraine Foundation and American Academy of Neurology. Some authors declared receiving research funding from or having other ties with various sources.

Source: Trivedi M, Dumkrieger G, Chong CD, et al. A history of abuse is associated with more severe migraine- and pain-related disability: Results from the American Registry for Migraine Research. Headache. 2024 (Jul 25). Doi: 10.1111/head.14787 Source

Key clinical point: Patients with migraine and a history of abuse had a greater migraine burden than those without a history of abuse, with this association being mediated by depression and anxiety.

Major findings: Patients with migraine who did vs did not have a history of abuse had significantly higher migraine-specific disability (68 vs 49), subjective cognitive impairment (10 vs 7), and pain interference (65 vs 62.5) scores, as well as greater overall work impairment (47.6% vs 38.6%) and activity impairment (49.3% vs 39.3%; all P < .001). Depression and anxiety mediated the association between history of abuse and migraine burden.

Study details: This cross-sectional study included 866 patients with migraine from the American Registry for Migraine Research, of whom 316 (36.5 %) had a history of abuse.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the American Migraine Foundation and American Academy of Neurology. Some authors declared receiving research funding from or having other ties with various sources.

Source: Trivedi M, Dumkrieger G, Chong CD, et al. A history of abuse is associated with more severe migraine- and pain-related disability: Results from the American Registry for Migraine Research. Headache. 2024 (Jul 25). Doi: 10.1111/head.14787 Source

Key clinical point: Patients with migraine and a history of abuse had a greater migraine burden than those without a history of abuse, with this association being mediated by depression and anxiety.

Major findings: Patients with migraine who did vs did not have a history of abuse had significantly higher migraine-specific disability (68 vs 49), subjective cognitive impairment (10 vs 7), and pain interference (65 vs 62.5) scores, as well as greater overall work impairment (47.6% vs 38.6%) and activity impairment (49.3% vs 39.3%; all P < .001). Depression and anxiety mediated the association between history of abuse and migraine burden.

Study details: This cross-sectional study included 866 patients with migraine from the American Registry for Migraine Research, of whom 316 (36.5 %) had a history of abuse.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the American Migraine Foundation and American Academy of Neurology. Some authors declared receiving research funding from or having other ties with various sources.

Source: Trivedi M, Dumkrieger G, Chong CD, et al. A history of abuse is associated with more severe migraine- and pain-related disability: Results from the American Registry for Migraine Research. Headache. 2024 (Jul 25). Doi: 10.1111/head.14787 Source

Anti-CGRP Antibody Efficacy Unaffected by Chronic Migraine Duration

Key clinical point: Anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) monoclonal antibodies (mAb) were effective and showed a similar time to onset in patients with chronic migraine (CM), irrespective of disease duration.

Major findings: At 10-12 months of follow-up, anti-CGRP mAb reduced monthly migraine days by an average of 12 days across all tertiles of CM duration (P = .946). Additionally, monthly headache days and acute medication use significantly decreased from baseline to 10-12 months (P < .001) across all tertiles of CM duration, indicating no difference in the time to onset of anti-CGRP mAb across tertiles.

Study details: This cohort study included 335 patients with CM treated with anti-CGRP mAb for at least 12 months. Patients were categorized into different tertiles of CM duration: 0-7 years, 8-18 years, and 18-60 years.

Disclosures: This study did not disclose any funding sources. Four authors declared receiving personal fees from or having other ties with various sources.

Source: Ornello R, Baldini F, Onofri A, et al. Impact of duration of chronic migraine on long-term effectiveness of monoclonal antibodies targeting the calcitonin gene-related peptide pathway-A real-world study. Headache. 2024 (Jul 16). Doi: 10.1111/head.14788 Source

Key clinical point: Anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) monoclonal antibodies (mAb) were effective and showed a similar time to onset in patients with chronic migraine (CM), irrespective of disease duration.

Major findings: At 10-12 months of follow-up, anti-CGRP mAb reduced monthly migraine days by an average of 12 days across all tertiles of CM duration (P = .946). Additionally, monthly headache days and acute medication use significantly decreased from baseline to 10-12 months (P < .001) across all tertiles of CM duration, indicating no difference in the time to onset of anti-CGRP mAb across tertiles.

Study details: This cohort study included 335 patients with CM treated with anti-CGRP mAb for at least 12 months. Patients were categorized into different tertiles of CM duration: 0-7 years, 8-18 years, and 18-60 years.

Disclosures: This study did not disclose any funding sources. Four authors declared receiving personal fees from or having other ties with various sources.

Source: Ornello R, Baldini F, Onofri A, et al. Impact of duration of chronic migraine on long-term effectiveness of monoclonal antibodies targeting the calcitonin gene-related peptide pathway-A real-world study. Headache. 2024 (Jul 16). Doi: 10.1111/head.14788 Source

Key clinical point: Anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) monoclonal antibodies (mAb) were effective and showed a similar time to onset in patients with chronic migraine (CM), irrespective of disease duration.

Major findings: At 10-12 months of follow-up, anti-CGRP mAb reduced monthly migraine days by an average of 12 days across all tertiles of CM duration (P = .946). Additionally, monthly headache days and acute medication use significantly decreased from baseline to 10-12 months (P < .001) across all tertiles of CM duration, indicating no difference in the time to onset of anti-CGRP mAb across tertiles.

Study details: This cohort study included 335 patients with CM treated with anti-CGRP mAb for at least 12 months. Patients were categorized into different tertiles of CM duration: 0-7 years, 8-18 years, and 18-60 years.

Disclosures: This study did not disclose any funding sources. Four authors declared receiving personal fees from or having other ties with various sources.

Source: Ornello R, Baldini F, Onofri A, et al. Impact of duration of chronic migraine on long-term effectiveness of monoclonal antibodies targeting the calcitonin gene-related peptide pathway-A real-world study. Headache. 2024 (Jul 16). Doi: 10.1111/head.14788 Source

Childhood Abuse Linked to Migraine Risk, Meta-analysis Shows

Key clinical point: Childhood abuse was significantly associated with an increased risk for migraine, with specific types such as physical, sexual, and emotional abuse showing a positive association with migraine onset.

Major findings: Individuals who experienced childhood abuse had a higher risk for migraine than those who did not (odd ratio [OR] 1.60; 95% CI 1.49-1.71). This risk was increased in those who were exposed to sexual abuse (OR 1.71; 95% CI 1.43-2.04), physical abuse (OR 1.47; 95% CI 1.38-1.56), and emotional abuse (OR 1.71; 95% CI 1.52-1.93).

Study details: This meta-analysis of 12 studies evaluated the association between childhood abuse and migraine in 110,776 patients with migraine.

Disclosures: No funding source was disclosed for this study. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Liu J, Guo Y, Huang Z, et al. Childhood abuse and risk of migraine: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Abuse Negl. 2024;155:106961 (Aug 2). Doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2024.106961 Source

Key clinical point: Childhood abuse was significantly associated with an increased risk for migraine, with specific types such as physical, sexual, and emotional abuse showing a positive association with migraine onset.

Major findings: Individuals who experienced childhood abuse had a higher risk for migraine than those who did not (odd ratio [OR] 1.60; 95% CI 1.49-1.71). This risk was increased in those who were exposed to sexual abuse (OR 1.71; 95% CI 1.43-2.04), physical abuse (OR 1.47; 95% CI 1.38-1.56), and emotional abuse (OR 1.71; 95% CI 1.52-1.93).

Study details: This meta-analysis of 12 studies evaluated the association between childhood abuse and migraine in 110,776 patients with migraine.

Disclosures: No funding source was disclosed for this study. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Liu J, Guo Y, Huang Z, et al. Childhood abuse and risk of migraine: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Abuse Negl. 2024;155:106961 (Aug 2). Doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2024.106961 Source

Key clinical point: Childhood abuse was significantly associated with an increased risk for migraine, with specific types such as physical, sexual, and emotional abuse showing a positive association with migraine onset.

Major findings: Individuals who experienced childhood abuse had a higher risk for migraine than those who did not (odd ratio [OR] 1.60; 95% CI 1.49-1.71). This risk was increased in those who were exposed to sexual abuse (OR 1.71; 95% CI 1.43-2.04), physical abuse (OR 1.47; 95% CI 1.38-1.56), and emotional abuse (OR 1.71; 95% CI 1.52-1.93).

Study details: This meta-analysis of 12 studies evaluated the association between childhood abuse and migraine in 110,776 patients with migraine.

Disclosures: No funding source was disclosed for this study. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Liu J, Guo Y, Huang Z, et al. Childhood abuse and risk of migraine: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Abuse Negl. 2024;155:106961 (Aug 2). Doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2024.106961 Source

Increasing Daily Steps Predicts Treatment Response to Anti-CGRP Antibodies in Chronic Migraine

Key clinical point: The daily step count increased noticeably after initiating treatment with anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) monoclonal antibodies (mAb) in adults with chronic migraine, with a positive association seen between the increase in daily steps and the treatment response to CGRP mAbs.

Major findings: The average number of steps per day increased from 4421 before initiation of anti-CGRP mAb treatment to 5241 at 3 months after initiation of treatment (P = .039), reflecting a mean percentage increase of 21.3% (95% CI 0.5-42.1). There was a positive association between an increase in daily steps and a reduction in monthly migraine days (correlation coefficient 0.521; P = .013).

Study details: This single-center, cross-sectional, retrospective study included 22 patients with chronic migraine who were treated with anti-CGRP mAbs (erenumab or fremanezumab).

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Lundbeck Foundation. Several authors declared receiving grants, honoraria, or personal fees from or having other ties with various sources.

Source: Jantzen FT, Chaudhry BA, Younis S, et al. Average steps per day as marker of treatment response with anti-CGRP mAbs in adults with chronic migraine: A pilot study. Sci Rep. 2024;14:18068 (Aug 5). Doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-68915-5 Source

Key clinical point: The daily step count increased noticeably after initiating treatment with anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) monoclonal antibodies (mAb) in adults with chronic migraine, with a positive association seen between the increase in daily steps and the treatment response to CGRP mAbs.

Major findings: The average number of steps per day increased from 4421 before initiation of anti-CGRP mAb treatment to 5241 at 3 months after initiation of treatment (P = .039), reflecting a mean percentage increase of 21.3% (95% CI 0.5-42.1). There was a positive association between an increase in daily steps and a reduction in monthly migraine days (correlation coefficient 0.521; P = .013).

Study details: This single-center, cross-sectional, retrospective study included 22 patients with chronic migraine who were treated with anti-CGRP mAbs (erenumab or fremanezumab).

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Lundbeck Foundation. Several authors declared receiving grants, honoraria, or personal fees from or having other ties with various sources.

Source: Jantzen FT, Chaudhry BA, Younis S, et al. Average steps per day as marker of treatment response with anti-CGRP mAbs in adults with chronic migraine: A pilot study. Sci Rep. 2024;14:18068 (Aug 5). Doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-68915-5 Source

Key clinical point: The daily step count increased noticeably after initiating treatment with anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) monoclonal antibodies (mAb) in adults with chronic migraine, with a positive association seen between the increase in daily steps and the treatment response to CGRP mAbs.

Major findings: The average number of steps per day increased from 4421 before initiation of anti-CGRP mAb treatment to 5241 at 3 months after initiation of treatment (P = .039), reflecting a mean percentage increase of 21.3% (95% CI 0.5-42.1). There was a positive association between an increase in daily steps and a reduction in monthly migraine days (correlation coefficient 0.521; P = .013).

Study details: This single-center, cross-sectional, retrospective study included 22 patients with chronic migraine who were treated with anti-CGRP mAbs (erenumab or fremanezumab).

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Lundbeck Foundation. Several authors declared receiving grants, honoraria, or personal fees from or having other ties with various sources.

Source: Jantzen FT, Chaudhry BA, Younis S, et al. Average steps per day as marker of treatment response with anti-CGRP mAbs in adults with chronic migraine: A pilot study. Sci Rep. 2024;14:18068 (Aug 5). Doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-68915-5 Source

Proinflammatory Diet Linked to Chronic Migraine Risk in Women

Key clinical point: Women with an increased adherence to a pro-inflammatory diet, as measured using a dietary inflammation score (DIS), had an increased risk for chronic migraine (CM).

Major findings: Women with CM had a significantly higher DIS than those with episodic migraine (EM) (0.08 vs 0.62; P = .002). The risk for CM was two times higher in women with a high DIS than in those with a low DIS (adjusted odd ratio 2.02; Ptrend = .03).

Study details: This cross-sectional study included 285 women with migraine, of whom 169 (59.3%) had EM and 116 (40.7%) had CM.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Student Research Committee of Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Bakhshimoghaddam F, Shalilahmadi D, Mahdavi R, et al. Association of dietary and lifestyle inflammation score (DLIS) with chronic migraine in women: A cross-sectional study. Sci Rep. 2024;14:16406 (Jul 16). Doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-66776-6 Source

Key clinical point: Women with an increased adherence to a pro-inflammatory diet, as measured using a dietary inflammation score (DIS), had an increased risk for chronic migraine (CM).

Major findings: Women with CM had a significantly higher DIS than those with episodic migraine (EM) (0.08 vs 0.62; P = .002). The risk for CM was two times higher in women with a high DIS than in those with a low DIS (adjusted odd ratio 2.02; Ptrend = .03).

Study details: This cross-sectional study included 285 women with migraine, of whom 169 (59.3%) had EM and 116 (40.7%) had CM.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Student Research Committee of Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Bakhshimoghaddam F, Shalilahmadi D, Mahdavi R, et al. Association of dietary and lifestyle inflammation score (DLIS) with chronic migraine in women: A cross-sectional study. Sci Rep. 2024;14:16406 (Jul 16). Doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-66776-6 Source

Key clinical point: Women with an increased adherence to a pro-inflammatory diet, as measured using a dietary inflammation score (DIS), had an increased risk for chronic migraine (CM).

Major findings: Women with CM had a significantly higher DIS than those with episodic migraine (EM) (0.08 vs 0.62; P = .002). The risk for CM was two times higher in women with a high DIS than in those with a low DIS (adjusted odd ratio 2.02; Ptrend = .03).

Study details: This cross-sectional study included 285 women with migraine, of whom 169 (59.3%) had EM and 116 (40.7%) had CM.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Student Research Committee of Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Bakhshimoghaddam F, Shalilahmadi D, Mahdavi R, et al. Association of dietary and lifestyle inflammation score (DLIS) with chronic migraine in women: A cross-sectional study. Sci Rep. 2024;14:16406 (Jul 16). Doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-66776-6 Source

Cardiovascular Risk Factors Affect Migraine Risk in Women

Key clinical point: Cardiovascular risk factors (CVRF), such as current smoking status and diabetes mellitus, were associated with a decreased prevalence of migraine in middle-aged and older-aged women, whereas elevated diastolic blood pressure (BP) was associated with an increased prevalence.

Major findings: Among women, current smokers (odds ratio [OR] 0.72; 95% CI 0.58-0.90) and those with diabetes mellitus (OR 0.74; 95% CI 0.56-0.98) had a decreased prevalence of migraine. Conversely, women with elevated diastolic BP had an increased prevalence of migraine (OR per standard deviation increase 1.16; 95% CI 1.04-1.29). No significant association was observed between CVRF and migraine in men.

Study details: This cross-sectional analysis assessed sex-specific associations of CVRF with migraine in 7266 middle-aged and older participants (4181 women and 3085 men) from the Rotterdam Study.

Disclosures: The Rotterdam Study was funded by the Erasmus Medical Center, Erasmus University Rotterdam, and others. Antoinette MaassenVanDenBrink declared receiving research grants or consultation fees from various sources.

Source: Al-Hassany L, Acarsoy C, Ikram MK, et al. Sex-specific association of cardiovascular risk factors with migraine: The Population-Based Rotterdam Study. Neurology. 2024;103:e209700 (Aug 27). Doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000209700 Source

Key clinical point: Cardiovascular risk factors (CVRF), such as current smoking status and diabetes mellitus, were associated with a decreased prevalence of migraine in middle-aged and older-aged women, whereas elevated diastolic blood pressure (BP) was associated with an increased prevalence.

Major findings: Among women, current smokers (odds ratio [OR] 0.72; 95% CI 0.58-0.90) and those with diabetes mellitus (OR 0.74; 95% CI 0.56-0.98) had a decreased prevalence of migraine. Conversely, women with elevated diastolic BP had an increased prevalence of migraine (OR per standard deviation increase 1.16; 95% CI 1.04-1.29). No significant association was observed between CVRF and migraine in men.

Study details: This cross-sectional analysis assessed sex-specific associations of CVRF with migraine in 7266 middle-aged and older participants (4181 women and 3085 men) from the Rotterdam Study.

Disclosures: The Rotterdam Study was funded by the Erasmus Medical Center, Erasmus University Rotterdam, and others. Antoinette MaassenVanDenBrink declared receiving research grants or consultation fees from various sources.

Source: Al-Hassany L, Acarsoy C, Ikram MK, et al. Sex-specific association of cardiovascular risk factors with migraine: The Population-Based Rotterdam Study. Neurology. 2024;103:e209700 (Aug 27). Doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000209700 Source

Key clinical point: Cardiovascular risk factors (CVRF), such as current smoking status and diabetes mellitus, were associated with a decreased prevalence of migraine in middle-aged and older-aged women, whereas elevated diastolic blood pressure (BP) was associated with an increased prevalence.

Major findings: Among women, current smokers (odds ratio [OR] 0.72; 95% CI 0.58-0.90) and those with diabetes mellitus (OR 0.74; 95% CI 0.56-0.98) had a decreased prevalence of migraine. Conversely, women with elevated diastolic BP had an increased prevalence of migraine (OR per standard deviation increase 1.16; 95% CI 1.04-1.29). No significant association was observed between CVRF and migraine in men.

Study details: This cross-sectional analysis assessed sex-specific associations of CVRF with migraine in 7266 middle-aged and older participants (4181 women and 3085 men) from the Rotterdam Study.

Disclosures: The Rotterdam Study was funded by the Erasmus Medical Center, Erasmus University Rotterdam, and others. Antoinette MaassenVanDenBrink declared receiving research grants or consultation fees from various sources.

Source: Al-Hassany L, Acarsoy C, Ikram MK, et al. Sex-specific association of cardiovascular risk factors with migraine: The Population-Based Rotterdam Study. Neurology. 2024;103:e209700 (Aug 27). Doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000209700 Source

The Use of Tranexamic Acid and Microneedling in the Treatment of Melasma: A Systematic Review

Melasma (also known as chloasma faciei) is a common chronic skin disorder that results in well-demarcated, hyperpigmented, tan to dark patches that mostly appear in sun-exposed areas such as the face and neck and sometimes the arms. The exact prevalence or incidence is not known but is estimated to be 1% to 50% overall depending on the ethnic population and geographic location.1,2 Melasma predominantly affects women, but research has shown that approximately 10% to 20% of men are affected by this condition.3,4 Although melasma can affect patients of all skin types, it primarily affects those with darker skin tones.5 The groups most often affected are women of Black, Hispanic, Middle Eastern, and Southeast Asian ethnicity. Although the pathogenesis is complex and not fully understood, multiple pathways and etiologies have been theorized to cause melasma. Potential causes include exposure to UV radiation, oral contraceptives, hormonal changes, medications, thyroid dysfunction, genetics, and pregnancy.6,7 Cytokines and growth factors, including adipokine and angiopoietin, synthesized by sebaceous glands play a role in the pathogenic mechanism of melasma. Cytokines and growth factors are hypothesized to modulate the function of melanocytes.8 Both melanocytes and sebocytes are controlled by α–melanocyte-stimulating hormone. Therefore, overexpression of α–melanocyte-stimulating hormone will result in overproduction of these 2 cell types, resulting in melasma. Melasma can be classified into 4 subtypes using Wood lamp examination: epidermal, dermal, mixed, or indeterminate.3 Furthermore, melasma is divided into subgroups based on the location: malar region, mandibular region, and centrofacial patch pattern.9,10 The involvement of sebaceous glands in the pathogenesis of melasma may explain the predilection for the centrofacial region, which is the most common pattern.

The severity of melasma can be assessed using the melasma area and severity index (MASI), which is calculated by subjective assessment of 3 main factors: (1) facial area of involvement; (2) darkness of affected region; and (3) homogeneity, with the extent of melasma indicated by a score ranging from 0 to 48.11 The modified MASI (mMASI) subsequently was introduced to assist with assessing the severity of melasma and creating distinct ranges for mild, moderate, and severe cases, ranging from 0 (mild) to 24 (severe).12 Both indices are used in research to assess the improvement of melasma with treatment.

Patients with melasma report a decrease in quality of life, increased emotional stress, and lower self-esteem due to cosmesis.13 Treatment of melasma can be highly challenging and often is complicated by relapsing. Historically, the treatment of melasma has included the use of chemical lightening agents. Additional treatment options include the use of lasers and complex chemical peels,9,10 but these interventions may result in adverse outcomes for individuals with darker skin tones. The current gold-standard treatment is topical hydroquinone and broad-spectrum sunscreen. Although hydroquinone is effective in the treatment of melasma, relapse is common. The goal of melasma management is not only to treat acute hyperpigmentation but also to prevent relapse. Other therapies that currently are being explored for the clinically sustained treatment of melasma include tranexamic acid (TXA)(trans-4-[aminomethyl]cyclohexanecarboxylic acid),9,10 an antifibrinolytic agent routinely used to prevent blood loss during surgery and in the management of menorrhagia. It is a synthetic derivative of lysine and serves as a potent plasmin inhibitor by blocking the lysine-binding sites of plasminogen molecules, thus preventing the conversion of plasminogen to plasmin. It also prevents fibrinolysis and blood loss.

In addition to its hemostatic properties, TXA has been found to have hypopigmentation properties.14,15 Plasminogen also can be found in human epidermal basal cells and human keratinocytes, and it is postulated that TXA’s interaction with these cells explains its hypopigmentation properties. Both UV radiation and hormones activate plasminogen into plasmin, resulting in the activation of tyrosinase and melanogenesis.14,15 Tranexamic acid is postulated to inhibit the keratinocyte-plasminogen pathway, thus leading to the inhibition of UV-induced and hormone-induced pigmentation. Also, TXA serves as a competitive inhibitor for tyrosinase due to its structural similarity to tyrosine.15 The combination of these 2 mechanisms contributes to the skin-lightening effects of TXA, making it a potential treatment for melasma.

Furthermore, the use of microneedling is being explored as a treatment option for melasma. Microneedling creates microscopic punctures in the skin using tiny needles, resulting in a wound-healing response and skin resurfacing. The microneedling technique is utilized to create small holes in the skin, with needle depths that can be adjusted from 0.5 to 3.5 mm to target different layers of the dermis and allow for discreet application of TXA.16 We sought to look at the current literature on the use and effectiveness of microneedling in combination with TXA to treat melasma and prevent relapse.

Methods

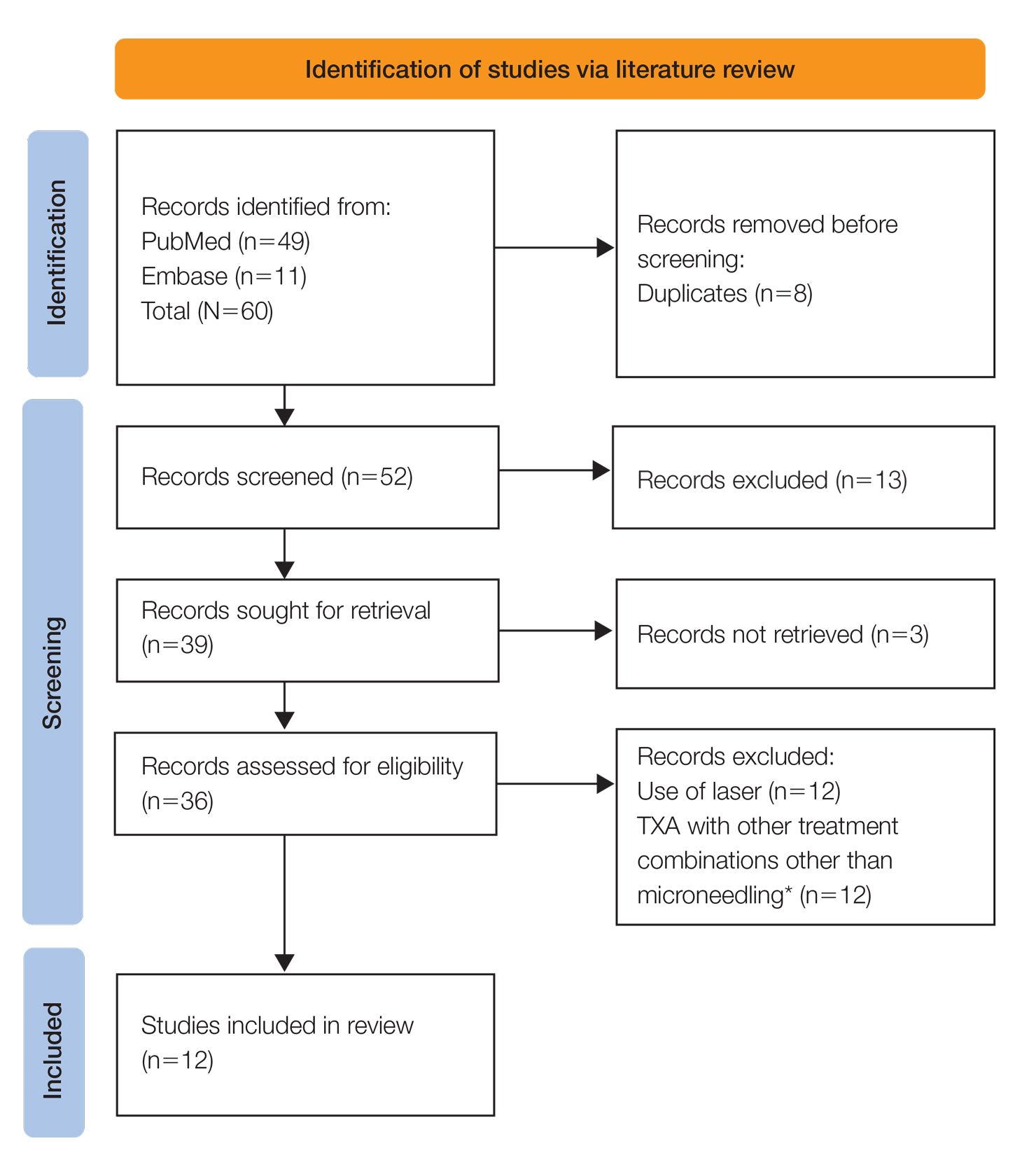

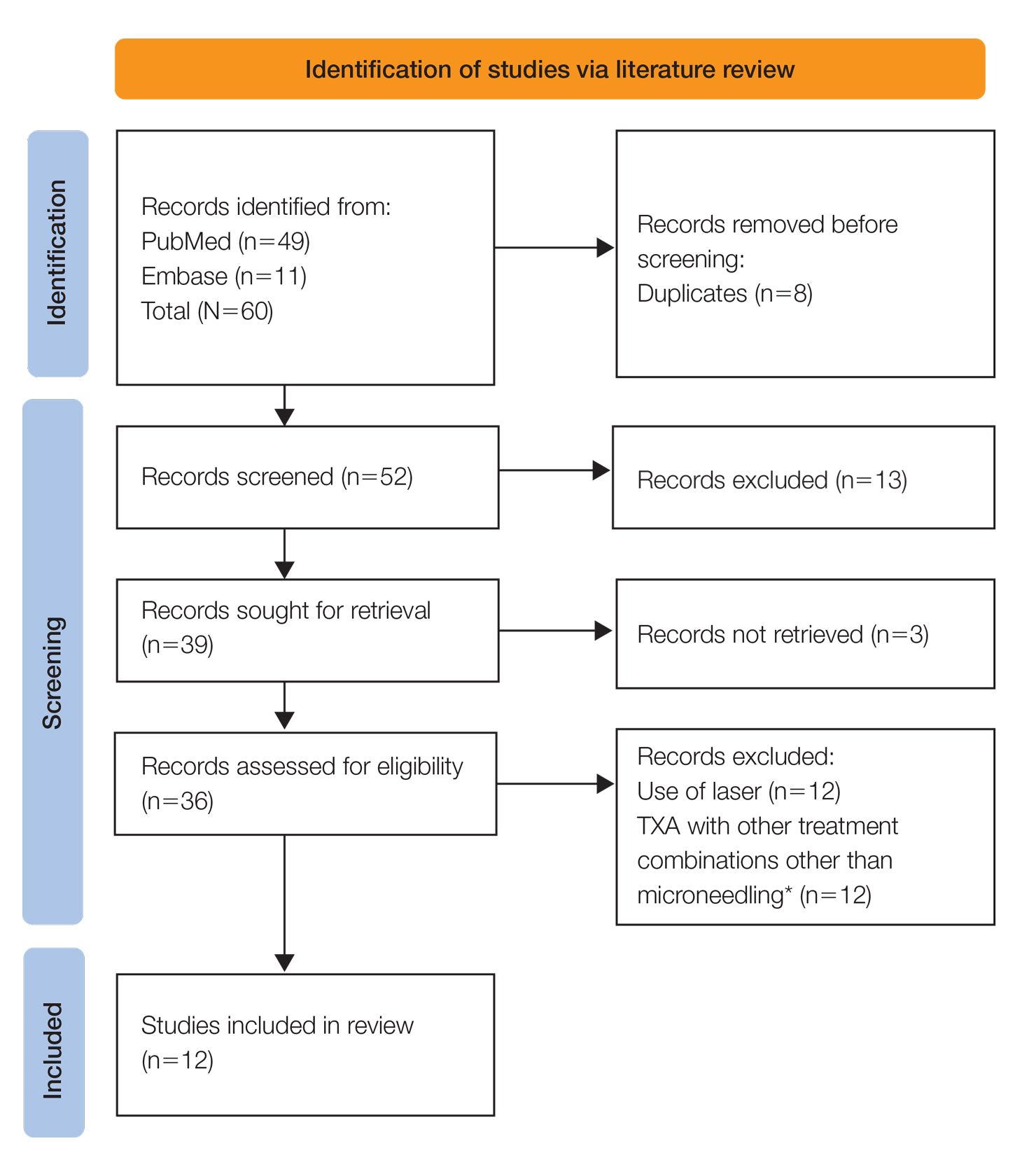

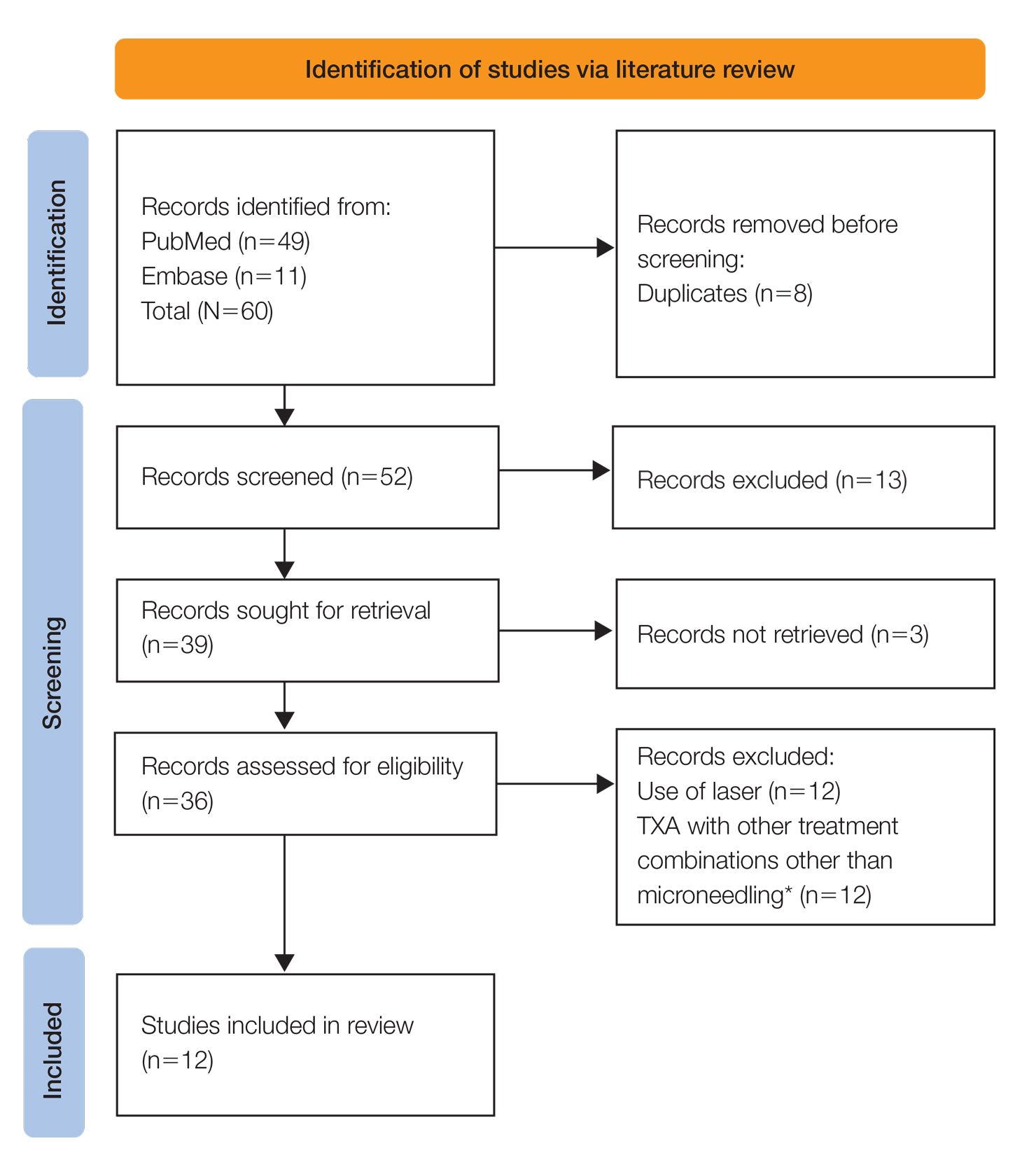

A systematic review was performed of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE and Embase in November 2021 to compile available articles that studied TXA and microneedling as a treatment for melasma. The PubMed search terms were (melasma) AND (microneedling* OR ‘tranexamic acid’ OR TXA or TA). The Embase search terms were (cholasma OR melasma) AND (tranexamic acid OR TXA) AND (microneedling)(Figure). The search was then limited to ”randomized controlled trial” and ”clinical trial” in English-language journals. Duplicates were excluded. After thorough evaluation, articles that discussed the use of TXA in combination with treatment options other than microneedling also were excluded.

Results

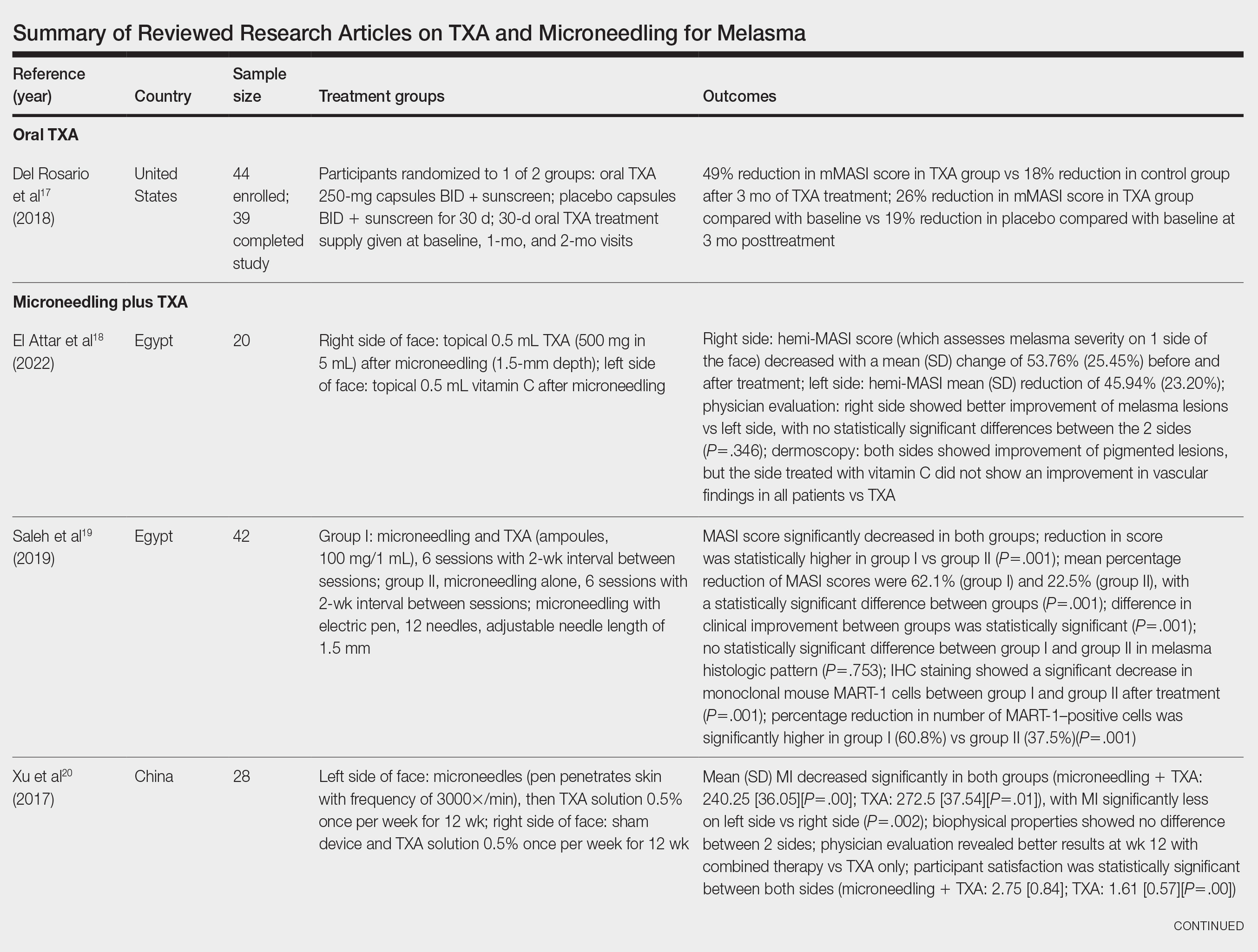

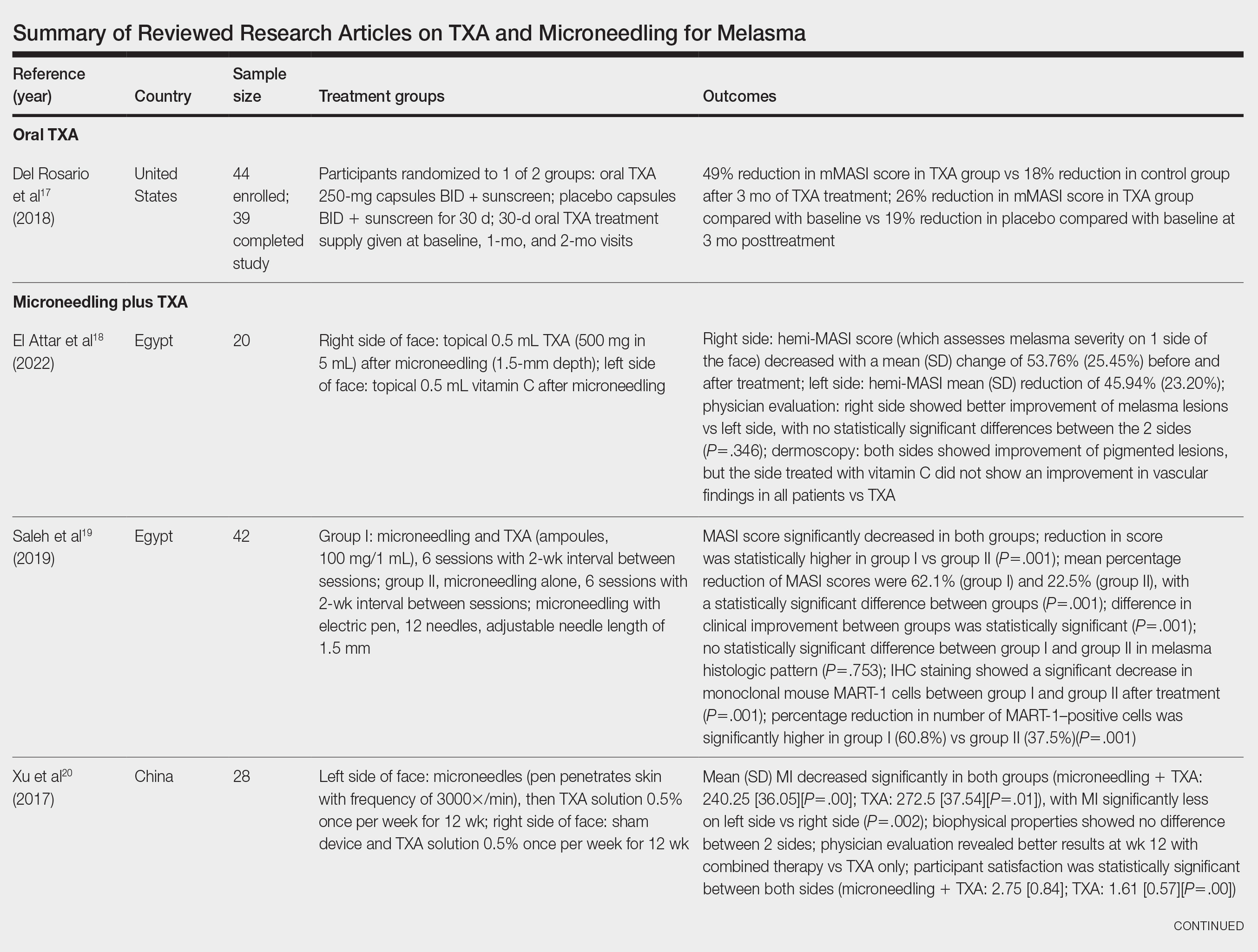

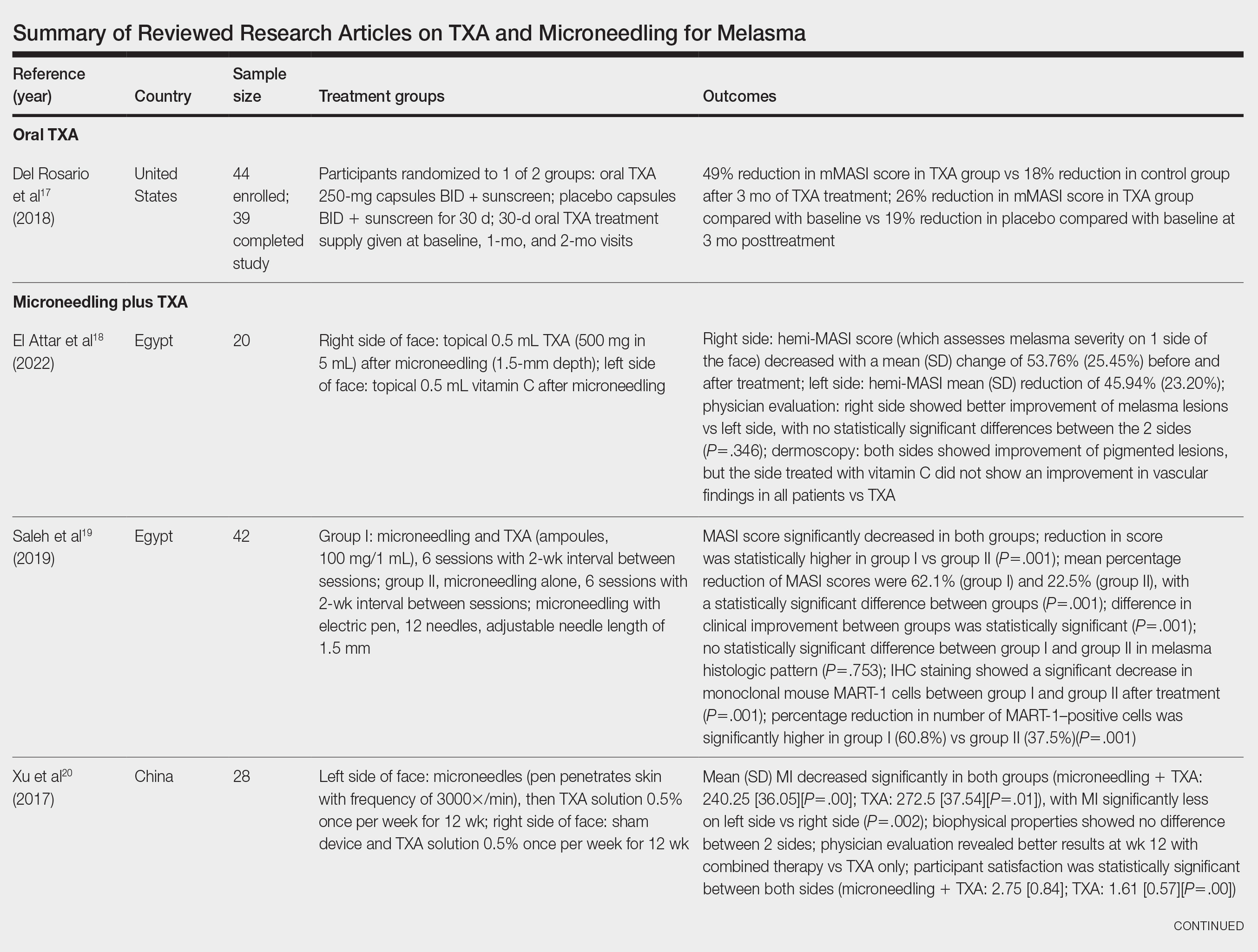

The literature search yielded a total of 12 articles that assessed the effectiveness of TXA and microneedling for the treatment of melasma (Table).17-28 Several articles concluded that TXA was equally effective at reducing melasma lesions when compared with the standard treatment of hydroquinone. Some of the reviewed articles also demonstrated the effectiveness of microneedling in improving melasma lesions as a stand-alone treatment. These studies highlighted the enhanced efficacy of the combined treatment of TXA and microneedling compared with their individual uses.17-28

Comment

Melasma is a common chronic hyperpigmentation disorder, making its treatment clinically challenging. Many patients experience symptom relapses, and limited effective treatment options make achieving complete clearance difficult, underscoring the need for improved therapeutic approaches. Recently, researchers have explored alternative treatments to address the challenges of melasma management. Tranexamic acid is an antifibrinolytic used to prevent blood loss and has emerged as a potential treatment for melasma. Similarly, microneedling—a technique in which multiple punctures are made in the skin to activate and stimulate wound healing and skin rejuvenation—shows promise for melasma.

Oral TXA for Melasma—Oral TXA has been shown to reduce melasma lesions. Del Rosario et al17 recruited 44 women (39 of whom completed the study) with moderate to severe melasma and randomized them into 2 groups: oral TXA and placebo. This study demonstrated a 49% reduction in the mMASI score in all participants taking oral TXA (250 mg twice daily [BID]) compared with an 18% reduction in the control group (placebo capsule BID) after 3 months of treatment. In patients with moderate and severe melasma, 45% and 51% mMASI score reductions were reported in the treatment group, respectively, vs 16% and 19% score reductions in placebo group, respectively. These researchers concluded that oral TXA may be effective at treating moderate to severe melasma. Although patients with severe melasma had a better response to treatment, their improvement was not sustained compared with patients with moderate melasma after a 3-month posttreatment follow-up.17

Microneedling Plus TXA for Melasma—Microneedling alone has been shown to be effective for melasma. El Attar et al18 conducted a split-face study of microneedling (1.5-mm depth) plus topical TXA (0.5 mL)(right side of the face[treatment arm]) compared with microneedling (1.5-mm depth) plus topical vitamin C (0.5 mL)(left side of the face [control group]) in 20 women with melasma. The sessions were repeated every 2 weeks for a total of 6 sessions. Although researchers found no statistically significant differences between the 2 treatment sides, microneedling plus TXA showed a slight advantage over microneedling plus vitamin C in dermoscopic examination. Both sides showed improvement in pigmented lesions, but vitamin C–treated lesions did not show an improvement in vascularity vs TXA.18

Saleh et al19 further showed that combination treatment with microneedling and TXA may improve clinical outcomes better than microneedling alone. Their study demonstrated a reduction in MASI score that was significantly higher in the combination treatment group compared with the microneedling alone group (P=.001). There was a significant reduction in melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1 (MART-1)–positive cells in the combination treatment group compared with the microneedling alone group (P=.001). Lastly, combined therapy improved melasma patches better than microneedling alone.19

Xu et al20 conducted a split-face study (N=28) exploring the effectiveness of transdermal application of topical TXA using a microarray pen with microneedles (vibration at 3000×/min) plus topical TXA on one side of the face, while the other side received only topical TXA as a control. After 12 weeks of treatment, combination therapy with microneedling and TXA decreased brown spot scores, lowered melanin index (MI) values, improved blinded physician assessment, and improved patient satisfaction vs TXA therapy alone.20

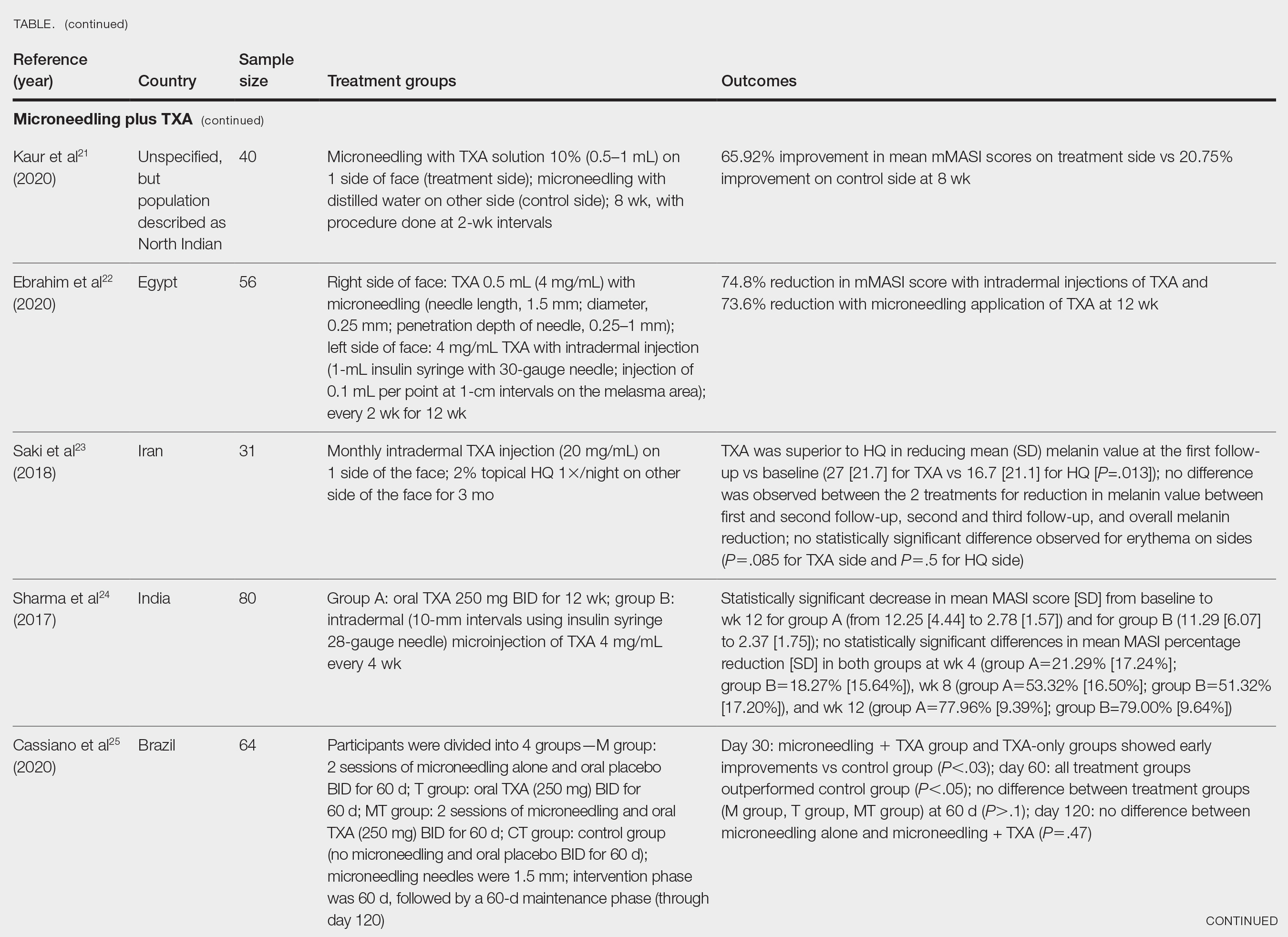

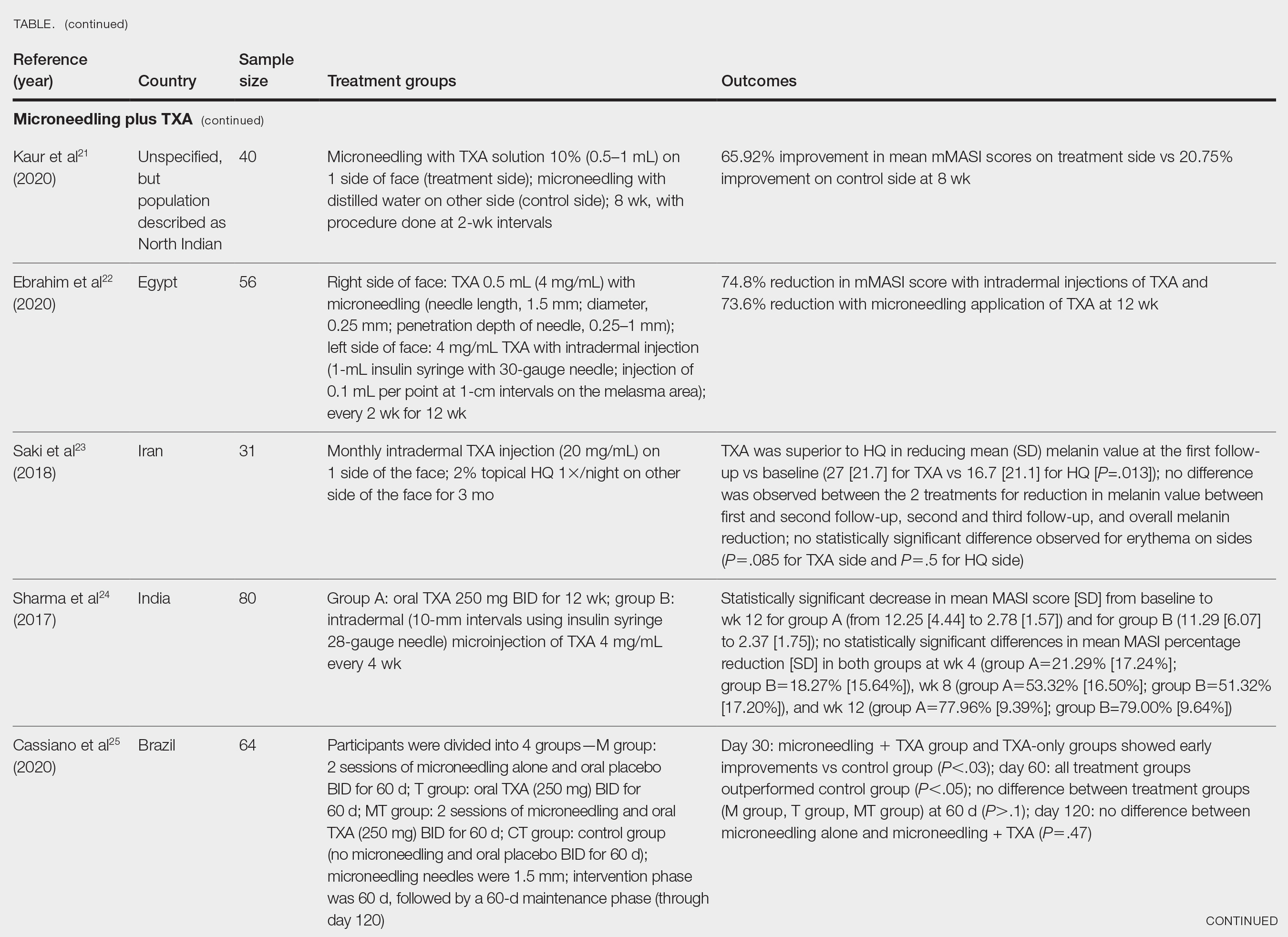

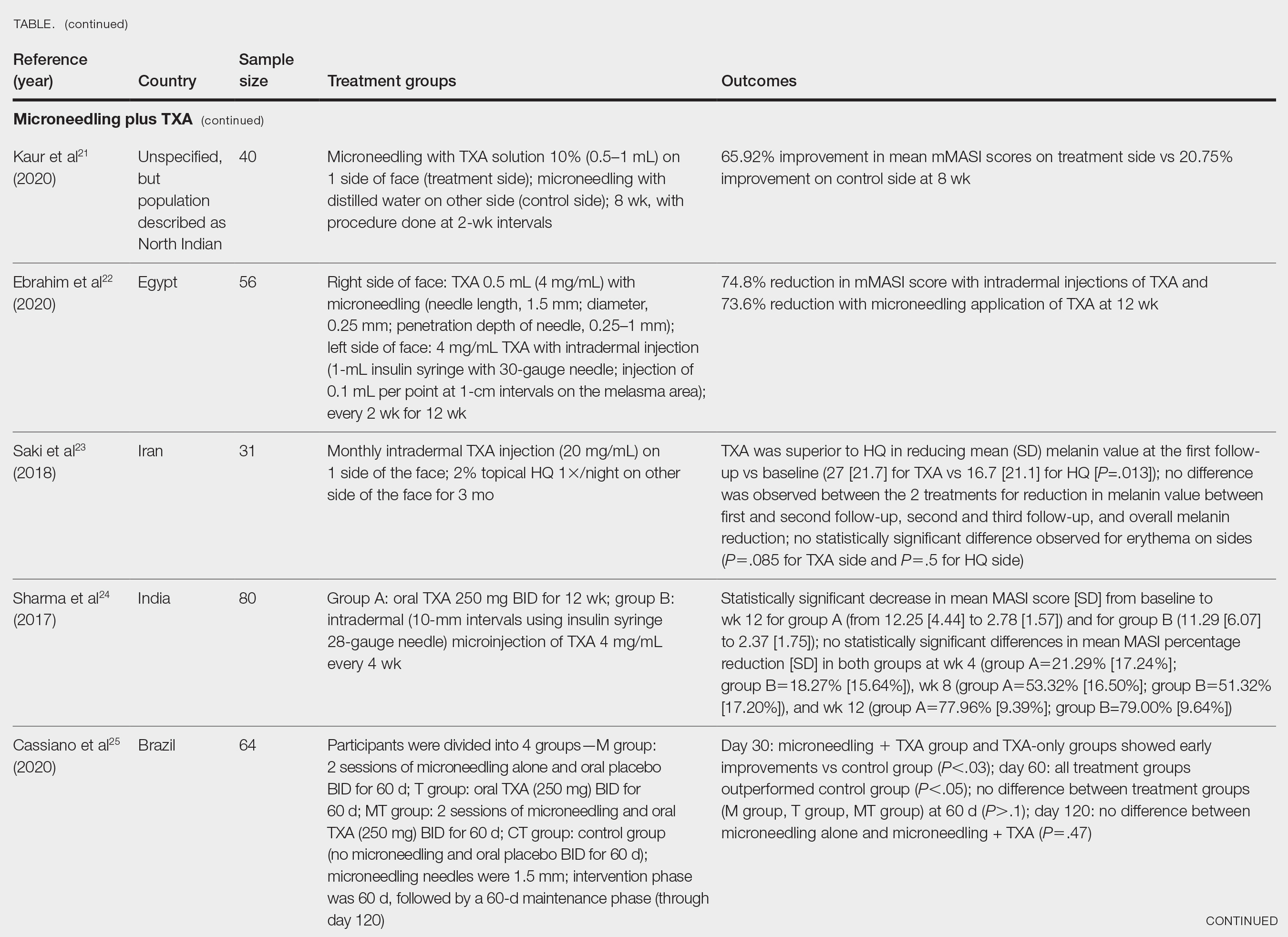

Kaur et al21 conducted a split-face, randomized, controlled trial of microneedling (1-mm depth) with TXA solution 10% vs microneedling (1-mm depth) with distilled water alone for 8 weeks (N=40). They graded participant responses to treatment using reductions in mMASI scores12 at every 2 weeks of follow-up (no response, minimal or poor response=0%–25%; partial or fair response=26%–50%; good response=51%–75%; and excellent response=>75%). They reported an overall reduction in mMASI scores for both the treatment side and the control side in all participants, showing a 65.92% improvement in mean mMASI scores on the treatment side vs 20.75% improvement on the control side at week 8. Both sides showed statistically significant reductions in mean mMASI scores (P<.05). Clinically, 40% (16/40) of participants showed an excellent response to combined treatment compared with 0% (0/40) to microneedling alone. Overall, patient satisfaction was similar across both groups. This study demonstrated that microneedling alone improves melasma, but a combination of microneedling plus TXA showed a better clinical reduction in melasma. However, the researchers did not follow up with participants posttreatment, so it remains unclear if the improved clinical outcomes were sustained long-term.21

Ebrahim et al22 reported that the combination of 0.5 mL TXA (4 mg/mL) and microneedling (0.25- to 1-mm depth) was effective for melasma. Although there was improvement within microneedling and TXA, the study also showed that intradermal injection of TXA was significant in reducing mean mMASI scores and improving melasma (P<.001). The reduction in mMASI scores for the group receiving intradermal injections of TXA (left side; 74.8% reduction in mean mMASI score) vs the group receiving microneedling application of TXA (right side; 73.6% reduction in mean mMASI score) was not statistically significant. These findings suggest that the mode of TXA application may not be critical in determining clinical responses to TXA treatment. Although there was no reported statistically significant difference in clinical outcomes between the 2 treatments, patient satisfaction was higher on the microneedling side. Only 8 of 50 participants (16%) experienced recurrence 3 months posttreatment.22

Saki et al23 compared the efficacy of topical hydroquinone (2%) to intradermal TXA injections in treating melasma. They found intradermal TXA injections to be a clinically effective mode of treatment.23

Sharma et al24 explored the efficacy and safety of oral TXA by randomly assigning 100 Indian patients (20 of whom withdrew before study completion) with melasma into 2 groups: group A received TXA 250 mg twice daily, and group B received intradermal microinjections of TXA (4 mg/mL) every 4 weeks. The MASI scores were assessed at 4-week intervals for a total of 12 weeks. There was a decrease in MASI scores in both groups, and there was no statistically significant difference in mean percentage reduction in MASI scores between the 2 routes of drug administration, further suggesting the effectiveness of TXA independent of administration route. Two patients in group A relapsed at 24 weeks, and there were no relapses in group B, which may suggest a minimal superiority of TXA plus microneedling at providing more sustainable results compared with oral TXA alone. A notable limitation of this study was a high dropout rate as well as lack of long-term follow-up with participants, limiting the generalizability of the conclusions.24

Cassiano et al25 assigned 64 women with melasma to 1 of 3 treatment groups or a control group to compare the effectiveness of microneedling (M group: 1.5 mm; 2 sessions), oral TXA (T group: 250 mg/d twice daily for 60 days), and a combination of microneedling (2 sessions) and oral TXA (MT group: 250 mg/d twice daily for 60 days)with placebo for clinically reducing melasma lesions. The intervention period was 60 days followed by a 60-day maintenance phase for a total study period of 120 days. The researchers evaluated mMASI scores, quality of life, and difference in colorimetric luminosity. All treatment groups showed a reduction in mMASI scores at both 30 days and 60 days, indicating improved melasma severity. The MT and T groups had more significant improvement at 30 days compared with the control group (P<.03), suggesting that microneedling plus TXA and TXA alone promote faster improvement in melasma lesions. By 60 days, the M, T, and MT groups outperformed the control group, with no significant differences between the M, T, and MT groups. However, at the 120-day maintenance follow-up, the T group did not maintain its improvement compared with the control group. The M and MT groups showed no significance difference in effectiveness at 120 days, suggesting that microneedling may promote less frequent relapse and sustained remission compared to TXA alone.25

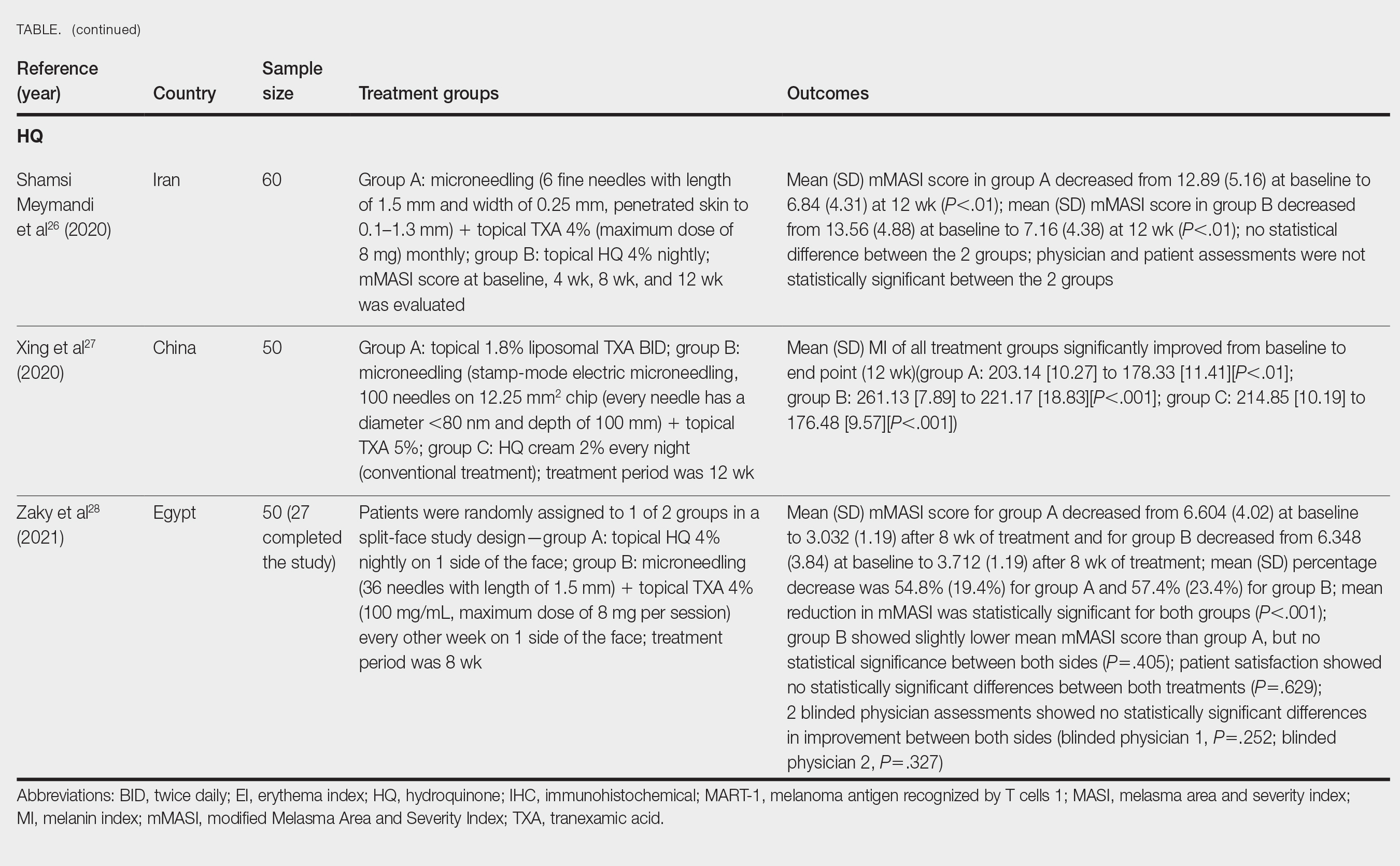

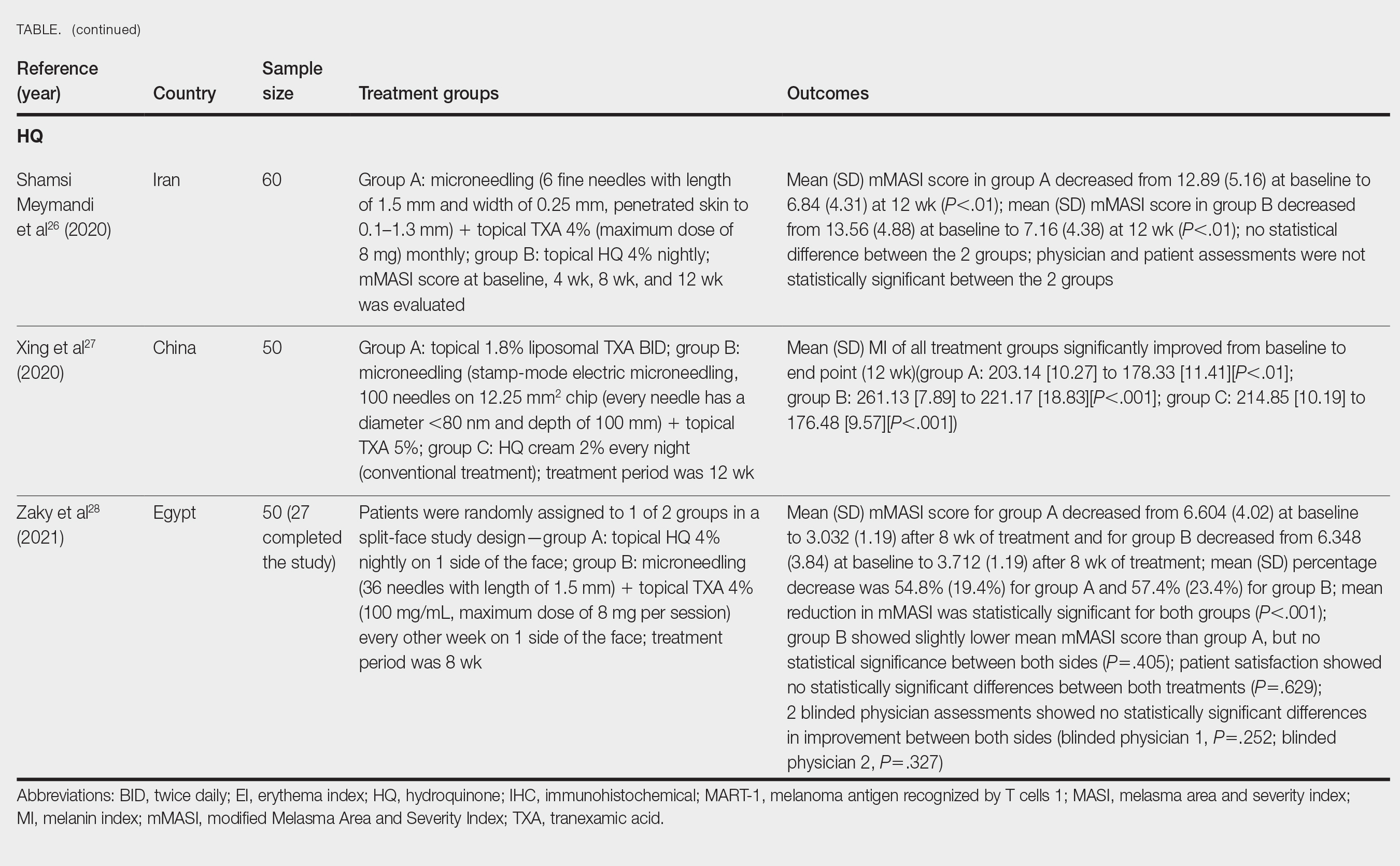

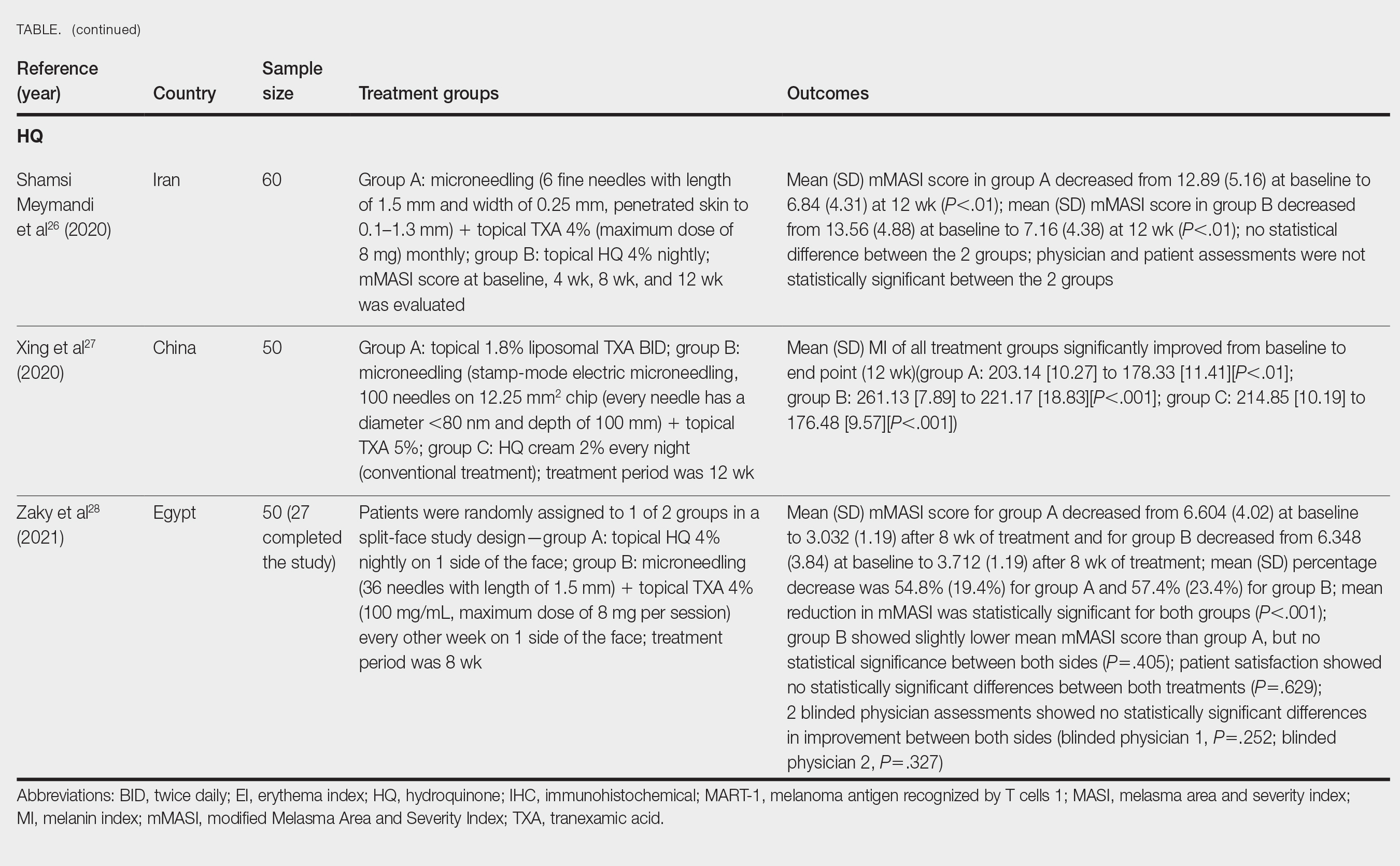

Hydroquinone for Melasma—Additional studies on the use of TXA treatments show that TXA may be an equally effective alternative to the standard use of hydroquinone treatment. Shamsi Meymandi et al26 did not find a statistically significant difference in treatment with TXA plus microneedling vs the standard regimen of hydroquinone. More importantly, patient and physician satisfaction assessments were similar between the 2 groups. Compared to hydroquinone, nightly treatment is not necessary with microneedling and TXA.26

Xing et al27 supported these conclusions with their study. They compared 3 study arms for a duration of 12 weeks: group A received topical 1.8% liposomal TXA BID, group B received stamp-mode electric microneedling with 5% TXA weekly, and group C applied 2% hydroquinone cream nightly. The study concluded that all 3 groups showed a significant reduction in mean MI by the end of the study, but a better MI improvement was observed in groups B and C (both P<.001) compared with group A (P<.01).27

Zaky et al28 showed that both hydroquinone and combination treatment of TXA plus microneedling are effective at improving melasma lesions. Further studies are needed to definitively conclude if combination treatment is more efficacious than hydroquinone; if the combination is more effective, it provides a treatment option for patients with melasma who may not be good candidates for hydroquinone treatment.

Study Limitations—One limitation in all the studies evaluated is the sample size. Because they all had small sample sizes, it is difficult to definitively conclude that the combination TXA and microneedling is an effective and appropriate treatment for patients with melasma. Furthermore, the quality of these studies was mostly dependent on subjectivity of the mMASI scores. Future large randomized controlled trials with a diverse participant population are needed to assess the effectiveness of TXA and microneedling in melasma treatment.

Another limitation is that many of the studies did not follow the patients longitudinally, which did not allow for an evaluation of whether patients had a relapse of melasma. Due to the chronic nature of melasma and frequent disease recurrence, future longitudinal studies are needed to monitor for disease recurrence.

Conclusion

Tranexamic acid and microneedling are potential treatment options for patients with melasma, and combination therapy appears more effective than either TXA or microneedling alone at providing sustained improvement of melasma lesions. Combination therapy appears safe and well tolerated, but its effect on reducing long-term disease recurrence is yet to be established.

- Neagu N, Conforti C, Agozzino M, et al. Melasma treatment: a systematic review. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33:1816-1837. doi:10.1080/09546634.2021.1914313

- Ogbechie-Godec OA, Elbuluk N. Melasma: an up-to-date comprehensive review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2017;7:305-318. doi:10.1007/s13555-017-0194-1

- Mahajan VK, Patil A, Blicharz L, et al. Medical therapies for melasma. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21:3707-3728. doi:10.1111/jocd.15242

- Rigopoulos D, Gregoriou S, Katsambas A. Hyperpigmentation and melasma. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2007;6:195-202. doi:10.1111/j.1473-2165.2007.00321.x

- Kagha K, Fabi S, Goldman M. Melasma’s impact on quality of life. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:184-187. doi:10.36849/JDD.2020.4663

- Lutfi RJ, Fridmanis M, Misiunas AL, et al. Association of melasma with thyroid autoimmunity and other thyroidal abnormalities and their relationship to the origin of the melasma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1985;61:28-31. doi:10.1210/jcem-61-1-28

- Handel AC, Lima PB, Tonolli VM, et al. Risk factors for facial melasma in women: a case-control study. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:588-594. doi:10.1111/bjd.13059

- Filoni A, Mariano M, Cameli N. Melasma: how hormones can modulate skin pigmentation. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2019;18:458-463. doi:10.1111/jocd.12877

- Rodrigues M, Pandya AG. Melasma: clinical diagnosis and management options. Australasian J Dermatol. 2015;56:151-163.

- Huerth KA, Hassan S, Callender VD. Therapeutic insights in melasma and hyperpigmentation management. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:718-727.

- Pandya AG, Hynan LS, Bhore R, et al. Reliability assessment and validation of the Melasma Area and Severity Index (MASI) and a new modified MASI scoring method. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:78-83.e832. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.10.051

- Rodrigues M, Ayala-Cortés AS, Rodríguez-Arámbula A, et al. Interpretability of the modified Melasma Area and Severity Index (mMASI). JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1051-1052. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.1006

- Ikino JK, Nunes DH, da Silva VPM, et al. Melasma and assessment of the quality of life in Brazilian women. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:196-200. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20152771

- Taraz M, Niknam S, Ehsani AH. Tranexamic acid in treatment of melasma: a comprehensive review of clinical studies. Dermatolog Ther. 2017;30:E12465. doi:10.1111/dth.12465

- Bala HR, Lee S, Wong C, et al. Oral tranexamic acid for the treatment of melasma: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:814-825. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001518

- Singh A, Yadav S. Microneedling: advances and widening horizons. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:244-254. doi:10.4103/2229-5178.185468

- Del Rosario E, Florez-Pollack S, Zapata L, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study of oral tranexamic acid in the treatment of moderate-to-severe melasma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:363-369. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.09.053

- El Attar Y, Doghaim N, El Far N, et al. Efficacy and safety of tranexamic acid versus vitamin C after microneedling in treatment of melasma: clinical and dermoscopic study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21:2817-2825. doi:10.1111/jocd.14538

- Saleh FY, Abdel-Azim ES, Ragaie MH, et al. Topical tranexamic acid with microneedling versus microneedling alone in treatment of melasma: clinical, histopathologic, and immunohistochemical study. J Egyptian Womens Dermatolog Soc. 2019;16:89-96. doi:10.4103/jewd.jewd_25_19

- Xu Y, Ma R, Juliandri J, et al. Efficacy of functional microarray of microneedles combined with topical tranexamic acid for melasma: a randomized, self-controlled, split-face study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e6897. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000006897

- Kaur A, Bhalla M, Pal Thami G, et al. Clinical efficacy of topical tranexamic acid with microneedling in melasma. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:E96-E101. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002520

- Ebrahim HM, Said Abdelshafy A, Khattab F, et al. Tranexamic acid for melasma treatment: a split-face study. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:E102-E107. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002449

- Saki N, Darayesh M, Heiran A. Comparing the efficacy of topical hydroquinone 2% versus intradermal tranexamic acid microinjections in treating melasma: a split-face controlled trial. J Dermatolog Treat. 2018;29:405-410. doi:10.1080/09546634.2017.1392476

- Sharma R, Mahajan VK, Mehta KS, et al. Therapeutic efficacy and safety of oral tranexamic acid and that of tranexamic acid local infiltration with microinjections in patients with melasma: a comparative study. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;42:728-734. doi:10.1111/ced.13164

- Cassiano D, Esposito ACC, Hassun K, et al. Efficacy and safety of microneedling and oral tranexamic acid in the treatment of facial melasma in women: an open, evaluator-blinded, randomized clinical trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1176-1178. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.02.002

- Shamsi Meymandi S, Mozayyeni A, Shamsi Meymandi M, et al. Efficacy of microneedling plus topical 4% tranexamic acid solution vs 4% hydroquinone in the treatment of melasma: a single-blind randomized clinical trial. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19:2906-2911. doi:10.1111/jocd.13392

- Xing X, Chen L, Xu Z, et al. The efficacy and safety of topical tranexamic acid (liposomal or lotion with microneedling) versus conventional hydroquinone in the treatment of melasma. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19:3238-3244. doi:10.1111/jocd.13810

- Zaky MS, Obaid ZM, Khalil EA, et al. Microneedling-assisted topical tranexamic acid solution versus 4% hydroquinone for treating melasma: a split-face randomized study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:4011-4016. doi:10.1111/jocd.14440

Melasma (also known as chloasma faciei) is a common chronic skin disorder that results in well-demarcated, hyperpigmented, tan to dark patches that mostly appear in sun-exposed areas such as the face and neck and sometimes the arms. The exact prevalence or incidence is not known but is estimated to be 1% to 50% overall depending on the ethnic population and geographic location.1,2 Melasma predominantly affects women, but research has shown that approximately 10% to 20% of men are affected by this condition.3,4 Although melasma can affect patients of all skin types, it primarily affects those with darker skin tones.5 The groups most often affected are women of Black, Hispanic, Middle Eastern, and Southeast Asian ethnicity. Although the pathogenesis is complex and not fully understood, multiple pathways and etiologies have been theorized to cause melasma. Potential causes include exposure to UV radiation, oral contraceptives, hormonal changes, medications, thyroid dysfunction, genetics, and pregnancy.6,7 Cytokines and growth factors, including adipokine and angiopoietin, synthesized by sebaceous glands play a role in the pathogenic mechanism of melasma. Cytokines and growth factors are hypothesized to modulate the function of melanocytes.8 Both melanocytes and sebocytes are controlled by α–melanocyte-stimulating hormone. Therefore, overexpression of α–melanocyte-stimulating hormone will result in overproduction of these 2 cell types, resulting in melasma. Melasma can be classified into 4 subtypes using Wood lamp examination: epidermal, dermal, mixed, or indeterminate.3 Furthermore, melasma is divided into subgroups based on the location: malar region, mandibular region, and centrofacial patch pattern.9,10 The involvement of sebaceous glands in the pathogenesis of melasma may explain the predilection for the centrofacial region, which is the most common pattern.

The severity of melasma can be assessed using the melasma area and severity index (MASI), which is calculated by subjective assessment of 3 main factors: (1) facial area of involvement; (2) darkness of affected region; and (3) homogeneity, with the extent of melasma indicated by a score ranging from 0 to 48.11 The modified MASI (mMASI) subsequently was introduced to assist with assessing the severity of melasma and creating distinct ranges for mild, moderate, and severe cases, ranging from 0 (mild) to 24 (severe).12 Both indices are used in research to assess the improvement of melasma with treatment.

Patients with melasma report a decrease in quality of life, increased emotional stress, and lower self-esteem due to cosmesis.13 Treatment of melasma can be highly challenging and often is complicated by relapsing. Historically, the treatment of melasma has included the use of chemical lightening agents. Additional treatment options include the use of lasers and complex chemical peels,9,10 but these interventions may result in adverse outcomes for individuals with darker skin tones. The current gold-standard treatment is topical hydroquinone and broad-spectrum sunscreen. Although hydroquinone is effective in the treatment of melasma, relapse is common. The goal of melasma management is not only to treat acute hyperpigmentation but also to prevent relapse. Other therapies that currently are being explored for the clinically sustained treatment of melasma include tranexamic acid (TXA)(trans-4-[aminomethyl]cyclohexanecarboxylic acid),9,10 an antifibrinolytic agent routinely used to prevent blood loss during surgery and in the management of menorrhagia. It is a synthetic derivative of lysine and serves as a potent plasmin inhibitor by blocking the lysine-binding sites of plasminogen molecules, thus preventing the conversion of plasminogen to plasmin. It also prevents fibrinolysis and blood loss.

In addition to its hemostatic properties, TXA has been found to have hypopigmentation properties.14,15 Plasminogen also can be found in human epidermal basal cells and human keratinocytes, and it is postulated that TXA’s interaction with these cells explains its hypopigmentation properties. Both UV radiation and hormones activate plasminogen into plasmin, resulting in the activation of tyrosinase and melanogenesis.14,15 Tranexamic acid is postulated to inhibit the keratinocyte-plasminogen pathway, thus leading to the inhibition of UV-induced and hormone-induced pigmentation. Also, TXA serves as a competitive inhibitor for tyrosinase due to its structural similarity to tyrosine.15 The combination of these 2 mechanisms contributes to the skin-lightening effects of TXA, making it a potential treatment for melasma.

Furthermore, the use of microneedling is being explored as a treatment option for melasma. Microneedling creates microscopic punctures in the skin using tiny needles, resulting in a wound-healing response and skin resurfacing. The microneedling technique is utilized to create small holes in the skin, with needle depths that can be adjusted from 0.5 to 3.5 mm to target different layers of the dermis and allow for discreet application of TXA.16 We sought to look at the current literature on the use and effectiveness of microneedling in combination with TXA to treat melasma and prevent relapse.

Methods

A systematic review was performed of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE and Embase in November 2021 to compile available articles that studied TXA and microneedling as a treatment for melasma. The PubMed search terms were (melasma) AND (microneedling* OR ‘tranexamic acid’ OR TXA or TA). The Embase search terms were (cholasma OR melasma) AND (tranexamic acid OR TXA) AND (microneedling)(Figure). The search was then limited to ”randomized controlled trial” and ”clinical trial” in English-language journals. Duplicates were excluded. After thorough evaluation, articles that discussed the use of TXA in combination with treatment options other than microneedling also were excluded.

Results

The literature search yielded a total of 12 articles that assessed the effectiveness of TXA and microneedling for the treatment of melasma (Table).17-28 Several articles concluded that TXA was equally effective at reducing melasma lesions when compared with the standard treatment of hydroquinone. Some of the reviewed articles also demonstrated the effectiveness of microneedling in improving melasma lesions as a stand-alone treatment. These studies highlighted the enhanced efficacy of the combined treatment of TXA and microneedling compared with their individual uses.17-28

Comment

Melasma is a common chronic hyperpigmentation disorder, making its treatment clinically challenging. Many patients experience symptom relapses, and limited effective treatment options make achieving complete clearance difficult, underscoring the need for improved therapeutic approaches. Recently, researchers have explored alternative treatments to address the challenges of melasma management. Tranexamic acid is an antifibrinolytic used to prevent blood loss and has emerged as a potential treatment for melasma. Similarly, microneedling—a technique in which multiple punctures are made in the skin to activate and stimulate wound healing and skin rejuvenation—shows promise for melasma.

Oral TXA for Melasma—Oral TXA has been shown to reduce melasma lesions. Del Rosario et al17 recruited 44 women (39 of whom completed the study) with moderate to severe melasma and randomized them into 2 groups: oral TXA and placebo. This study demonstrated a 49% reduction in the mMASI score in all participants taking oral TXA (250 mg twice daily [BID]) compared with an 18% reduction in the control group (placebo capsule BID) after 3 months of treatment. In patients with moderate and severe melasma, 45% and 51% mMASI score reductions were reported in the treatment group, respectively, vs 16% and 19% score reductions in placebo group, respectively. These researchers concluded that oral TXA may be effective at treating moderate to severe melasma. Although patients with severe melasma had a better response to treatment, their improvement was not sustained compared with patients with moderate melasma after a 3-month posttreatment follow-up.17

Microneedling Plus TXA for Melasma—Microneedling alone has been shown to be effective for melasma. El Attar et al18 conducted a split-face study of microneedling (1.5-mm depth) plus topical TXA (0.5 mL)(right side of the face[treatment arm]) compared with microneedling (1.5-mm depth) plus topical vitamin C (0.5 mL)(left side of the face [control group]) in 20 women with melasma. The sessions were repeated every 2 weeks for a total of 6 sessions. Although researchers found no statistically significant differences between the 2 treatment sides, microneedling plus TXA showed a slight advantage over microneedling plus vitamin C in dermoscopic examination. Both sides showed improvement in pigmented lesions, but vitamin C–treated lesions did not show an improvement in vascularity vs TXA.18

Saleh et al19 further showed that combination treatment with microneedling and TXA may improve clinical outcomes better than microneedling alone. Their study demonstrated a reduction in MASI score that was significantly higher in the combination treatment group compared with the microneedling alone group (P=.001). There was a significant reduction in melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1 (MART-1)–positive cells in the combination treatment group compared with the microneedling alone group (P=.001). Lastly, combined therapy improved melasma patches better than microneedling alone.19

Xu et al20 conducted a split-face study (N=28) exploring the effectiveness of transdermal application of topical TXA using a microarray pen with microneedles (vibration at 3000×/min) plus topical TXA on one side of the face, while the other side received only topical TXA as a control. After 12 weeks of treatment, combination therapy with microneedling and TXA decreased brown spot scores, lowered melanin index (MI) values, improved blinded physician assessment, and improved patient satisfaction vs TXA therapy alone.20

Kaur et al21 conducted a split-face, randomized, controlled trial of microneedling (1-mm depth) with TXA solution 10% vs microneedling (1-mm depth) with distilled water alone for 8 weeks (N=40). They graded participant responses to treatment using reductions in mMASI scores12 at every 2 weeks of follow-up (no response, minimal or poor response=0%–25%; partial or fair response=26%–50%; good response=51%–75%; and excellent response=>75%). They reported an overall reduction in mMASI scores for both the treatment side and the control side in all participants, showing a 65.92% improvement in mean mMASI scores on the treatment side vs 20.75% improvement on the control side at week 8. Both sides showed statistically significant reductions in mean mMASI scores (P<.05). Clinically, 40% (16/40) of participants showed an excellent response to combined treatment compared with 0% (0/40) to microneedling alone. Overall, patient satisfaction was similar across both groups. This study demonstrated that microneedling alone improves melasma, but a combination of microneedling plus TXA showed a better clinical reduction in melasma. However, the researchers did not follow up with participants posttreatment, so it remains unclear if the improved clinical outcomes were sustained long-term.21

Ebrahim et al22 reported that the combination of 0.5 mL TXA (4 mg/mL) and microneedling (0.25- to 1-mm depth) was effective for melasma. Although there was improvement within microneedling and TXA, the study also showed that intradermal injection of TXA was significant in reducing mean mMASI scores and improving melasma (P<.001). The reduction in mMASI scores for the group receiving intradermal injections of TXA (left side; 74.8% reduction in mean mMASI score) vs the group receiving microneedling application of TXA (right side; 73.6% reduction in mean mMASI score) was not statistically significant. These findings suggest that the mode of TXA application may not be critical in determining clinical responses to TXA treatment. Although there was no reported statistically significant difference in clinical outcomes between the 2 treatments, patient satisfaction was higher on the microneedling side. Only 8 of 50 participants (16%) experienced recurrence 3 months posttreatment.22

Saki et al23 compared the efficacy of topical hydroquinone (2%) to intradermal TXA injections in treating melasma. They found intradermal TXA injections to be a clinically effective mode of treatment.23

Sharma et al24 explored the efficacy and safety of oral TXA by randomly assigning 100 Indian patients (20 of whom withdrew before study completion) with melasma into 2 groups: group A received TXA 250 mg twice daily, and group B received intradermal microinjections of TXA (4 mg/mL) every 4 weeks. The MASI scores were assessed at 4-week intervals for a total of 12 weeks. There was a decrease in MASI scores in both groups, and there was no statistically significant difference in mean percentage reduction in MASI scores between the 2 routes of drug administration, further suggesting the effectiveness of TXA independent of administration route. Two patients in group A relapsed at 24 weeks, and there were no relapses in group B, which may suggest a minimal superiority of TXA plus microneedling at providing more sustainable results compared with oral TXA alone. A notable limitation of this study was a high dropout rate as well as lack of long-term follow-up with participants, limiting the generalizability of the conclusions.24

Cassiano et al25 assigned 64 women with melasma to 1 of 3 treatment groups or a control group to compare the effectiveness of microneedling (M group: 1.5 mm; 2 sessions), oral TXA (T group: 250 mg/d twice daily for 60 days), and a combination of microneedling (2 sessions) and oral TXA (MT group: 250 mg/d twice daily for 60 days)with placebo for clinically reducing melasma lesions. The intervention period was 60 days followed by a 60-day maintenance phase for a total study period of 120 days. The researchers evaluated mMASI scores, quality of life, and difference in colorimetric luminosity. All treatment groups showed a reduction in mMASI scores at both 30 days and 60 days, indicating improved melasma severity. The MT and T groups had more significant improvement at 30 days compared with the control group (P<.03), suggesting that microneedling plus TXA and TXA alone promote faster improvement in melasma lesions. By 60 days, the M, T, and MT groups outperformed the control group, with no significant differences between the M, T, and MT groups. However, at the 120-day maintenance follow-up, the T group did not maintain its improvement compared with the control group. The M and MT groups showed no significance difference in effectiveness at 120 days, suggesting that microneedling may promote less frequent relapse and sustained remission compared to TXA alone.25

Hydroquinone for Melasma—Additional studies on the use of TXA treatments show that TXA may be an equally effective alternative to the standard use of hydroquinone treatment. Shamsi Meymandi et al26 did not find a statistically significant difference in treatment with TXA plus microneedling vs the standard regimen of hydroquinone. More importantly, patient and physician satisfaction assessments were similar between the 2 groups. Compared to hydroquinone, nightly treatment is not necessary with microneedling and TXA.26

Xing et al27 supported these conclusions with their study. They compared 3 study arms for a duration of 12 weeks: group A received topical 1.8% liposomal TXA BID, group B received stamp-mode electric microneedling with 5% TXA weekly, and group C applied 2% hydroquinone cream nightly. The study concluded that all 3 groups showed a significant reduction in mean MI by the end of the study, but a better MI improvement was observed in groups B and C (both P<.001) compared with group A (P<.01).27

Zaky et al28 showed that both hydroquinone and combination treatment of TXA plus microneedling are effective at improving melasma lesions. Further studies are needed to definitively conclude if combination treatment is more efficacious than hydroquinone; if the combination is more effective, it provides a treatment option for patients with melasma who may not be good candidates for hydroquinone treatment.

Study Limitations—One limitation in all the studies evaluated is the sample size. Because they all had small sample sizes, it is difficult to definitively conclude that the combination TXA and microneedling is an effective and appropriate treatment for patients with melasma. Furthermore, the quality of these studies was mostly dependent on subjectivity of the mMASI scores. Future large randomized controlled trials with a diverse participant population are needed to assess the effectiveness of TXA and microneedling in melasma treatment.

Another limitation is that many of the studies did not follow the patients longitudinally, which did not allow for an evaluation of whether patients had a relapse of melasma. Due to the chronic nature of melasma and frequent disease recurrence, future longitudinal studies are needed to monitor for disease recurrence.

Conclusion

Tranexamic acid and microneedling are potential treatment options for patients with melasma, and combination therapy appears more effective than either TXA or microneedling alone at providing sustained improvement of melasma lesions. Combination therapy appears safe and well tolerated, but its effect on reducing long-term disease recurrence is yet to be established.

Melasma (also known as chloasma faciei) is a common chronic skin disorder that results in well-demarcated, hyperpigmented, tan to dark patches that mostly appear in sun-exposed areas such as the face and neck and sometimes the arms. The exact prevalence or incidence is not known but is estimated to be 1% to 50% overall depending on the ethnic population and geographic location.1,2 Melasma predominantly affects women, but research has shown that approximately 10% to 20% of men are affected by this condition.3,4 Although melasma can affect patients of all skin types, it primarily affects those with darker skin tones.5 The groups most often affected are women of Black, Hispanic, Middle Eastern, and Southeast Asian ethnicity. Although the pathogenesis is complex and not fully understood, multiple pathways and etiologies have been theorized to cause melasma. Potential causes include exposure to UV radiation, oral contraceptives, hormonal changes, medications, thyroid dysfunction, genetics, and pregnancy.6,7 Cytokines and growth factors, including adipokine and angiopoietin, synthesized by sebaceous glands play a role in the pathogenic mechanism of melasma. Cytokines and growth factors are hypothesized to modulate the function of melanocytes.8 Both melanocytes and sebocytes are controlled by α–melanocyte-stimulating hormone. Therefore, overexpression of α–melanocyte-stimulating hormone will result in overproduction of these 2 cell types, resulting in melasma. Melasma can be classified into 4 subtypes using Wood lamp examination: epidermal, dermal, mixed, or indeterminate.3 Furthermore, melasma is divided into subgroups based on the location: malar region, mandibular region, and centrofacial patch pattern.9,10 The involvement of sebaceous glands in the pathogenesis of melasma may explain the predilection for the centrofacial region, which is the most common pattern.

The severity of melasma can be assessed using the melasma area and severity index (MASI), which is calculated by subjective assessment of 3 main factors: (1) facial area of involvement; (2) darkness of affected region; and (3) homogeneity, with the extent of melasma indicated by a score ranging from 0 to 48.11 The modified MASI (mMASI) subsequently was introduced to assist with assessing the severity of melasma and creating distinct ranges for mild, moderate, and severe cases, ranging from 0 (mild) to 24 (severe).12 Both indices are used in research to assess the improvement of melasma with treatment.

Patients with melasma report a decrease in quality of life, increased emotional stress, and lower self-esteem due to cosmesis.13 Treatment of melasma can be highly challenging and often is complicated by relapsing. Historically, the treatment of melasma has included the use of chemical lightening agents. Additional treatment options include the use of lasers and complex chemical peels,9,10 but these interventions may result in adverse outcomes for individuals with darker skin tones. The current gold-standard treatment is topical hydroquinone and broad-spectrum sunscreen. Although hydroquinone is effective in the treatment of melasma, relapse is common. The goal of melasma management is not only to treat acute hyperpigmentation but also to prevent relapse. Other therapies that currently are being explored for the clinically sustained treatment of melasma include tranexamic acid (TXA)(trans-4-[aminomethyl]cyclohexanecarboxylic acid),9,10 an antifibrinolytic agent routinely used to prevent blood loss during surgery and in the management of menorrhagia. It is a synthetic derivative of lysine and serves as a potent plasmin inhibitor by blocking the lysine-binding sites of plasminogen molecules, thus preventing the conversion of plasminogen to plasmin. It also prevents fibrinolysis and blood loss.

In addition to its hemostatic properties, TXA has been found to have hypopigmentation properties.14,15 Plasminogen also can be found in human epidermal basal cells and human keratinocytes, and it is postulated that TXA’s interaction with these cells explains its hypopigmentation properties. Both UV radiation and hormones activate plasminogen into plasmin, resulting in the activation of tyrosinase and melanogenesis.14,15 Tranexamic acid is postulated to inhibit the keratinocyte-plasminogen pathway, thus leading to the inhibition of UV-induced and hormone-induced pigmentation. Also, TXA serves as a competitive inhibitor for tyrosinase due to its structural similarity to tyrosine.15 The combination of these 2 mechanisms contributes to the skin-lightening effects of TXA, making it a potential treatment for melasma.

Furthermore, the use of microneedling is being explored as a treatment option for melasma. Microneedling creates microscopic punctures in the skin using tiny needles, resulting in a wound-healing response and skin resurfacing. The microneedling technique is utilized to create small holes in the skin, with needle depths that can be adjusted from 0.5 to 3.5 mm to target different layers of the dermis and allow for discreet application of TXA.16 We sought to look at the current literature on the use and effectiveness of microneedling in combination with TXA to treat melasma and prevent relapse.

Methods

A systematic review was performed of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE and Embase in November 2021 to compile available articles that studied TXA and microneedling as a treatment for melasma. The PubMed search terms were (melasma) AND (microneedling* OR ‘tranexamic acid’ OR TXA or TA). The Embase search terms were (cholasma OR melasma) AND (tranexamic acid OR TXA) AND (microneedling)(Figure). The search was then limited to ”randomized controlled trial” and ”clinical trial” in English-language journals. Duplicates were excluded. After thorough evaluation, articles that discussed the use of TXA in combination with treatment options other than microneedling also were excluded.

Results

The literature search yielded a total of 12 articles that assessed the effectiveness of TXA and microneedling for the treatment of melasma (Table).17-28 Several articles concluded that TXA was equally effective at reducing melasma lesions when compared with the standard treatment of hydroquinone. Some of the reviewed articles also demonstrated the effectiveness of microneedling in improving melasma lesions as a stand-alone treatment. These studies highlighted the enhanced efficacy of the combined treatment of TXA and microneedling compared with their individual uses.17-28

Comment

Melasma is a common chronic hyperpigmentation disorder, making its treatment clinically challenging. Many patients experience symptom relapses, and limited effective treatment options make achieving complete clearance difficult, underscoring the need for improved therapeutic approaches. Recently, researchers have explored alternative treatments to address the challenges of melasma management. Tranexamic acid is an antifibrinolytic used to prevent blood loss and has emerged as a potential treatment for melasma. Similarly, microneedling—a technique in which multiple punctures are made in the skin to activate and stimulate wound healing and skin rejuvenation—shows promise for melasma.

Oral TXA for Melasma—Oral TXA has been shown to reduce melasma lesions. Del Rosario et al17 recruited 44 women (39 of whom completed the study) with moderate to severe melasma and randomized them into 2 groups: oral TXA and placebo. This study demonstrated a 49% reduction in the mMASI score in all participants taking oral TXA (250 mg twice daily [BID]) compared with an 18% reduction in the control group (placebo capsule BID) after 3 months of treatment. In patients with moderate and severe melasma, 45% and 51% mMASI score reductions were reported in the treatment group, respectively, vs 16% and 19% score reductions in placebo group, respectively. These researchers concluded that oral TXA may be effective at treating moderate to severe melasma. Although patients with severe melasma had a better response to treatment, their improvement was not sustained compared with patients with moderate melasma after a 3-month posttreatment follow-up.17

Microneedling Plus TXA for Melasma—Microneedling alone has been shown to be effective for melasma. El Attar et al18 conducted a split-face study of microneedling (1.5-mm depth) plus topical TXA (0.5 mL)(right side of the face[treatment arm]) compared with microneedling (1.5-mm depth) plus topical vitamin C (0.5 mL)(left side of the face [control group]) in 20 women with melasma. The sessions were repeated every 2 weeks for a total of 6 sessions. Although researchers found no statistically significant differences between the 2 treatment sides, microneedling plus TXA showed a slight advantage over microneedling plus vitamin C in dermoscopic examination. Both sides showed improvement in pigmented lesions, but vitamin C–treated lesions did not show an improvement in vascularity vs TXA.18

Saleh et al19 further showed that combination treatment with microneedling and TXA may improve clinical outcomes better than microneedling alone. Their study demonstrated a reduction in MASI score that was significantly higher in the combination treatment group compared with the microneedling alone group (P=.001). There was a significant reduction in melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1 (MART-1)–positive cells in the combination treatment group compared with the microneedling alone group (P=.001). Lastly, combined therapy improved melasma patches better than microneedling alone.19

Xu et al20 conducted a split-face study (N=28) exploring the effectiveness of transdermal application of topical TXA using a microarray pen with microneedles (vibration at 3000×/min) plus topical TXA on one side of the face, while the other side received only topical TXA as a control. After 12 weeks of treatment, combination therapy with microneedling and TXA decreased brown spot scores, lowered melanin index (MI) values, improved blinded physician assessment, and improved patient satisfaction vs TXA therapy alone.20

Kaur et al21 conducted a split-face, randomized, controlled trial of microneedling (1-mm depth) with TXA solution 10% vs microneedling (1-mm depth) with distilled water alone for 8 weeks (N=40). They graded participant responses to treatment using reductions in mMASI scores12 at every 2 weeks of follow-up (no response, minimal or poor response=0%–25%; partial or fair response=26%–50%; good response=51%–75%; and excellent response=>75%). They reported an overall reduction in mMASI scores for both the treatment side and the control side in all participants, showing a 65.92% improvement in mean mMASI scores on the treatment side vs 20.75% improvement on the control side at week 8. Both sides showed statistically significant reductions in mean mMASI scores (P<.05). Clinically, 40% (16/40) of participants showed an excellent response to combined treatment compared with 0% (0/40) to microneedling alone. Overall, patient satisfaction was similar across both groups. This study demonstrated that microneedling alone improves melasma, but a combination of microneedling plus TXA showed a better clinical reduction in melasma. However, the researchers did not follow up with participants posttreatment, so it remains unclear if the improved clinical outcomes were sustained long-term.21

Ebrahim et al22 reported that the combination of 0.5 mL TXA (4 mg/mL) and microneedling (0.25- to 1-mm depth) was effective for melasma. Although there was improvement within microneedling and TXA, the study also showed that intradermal injection of TXA was significant in reducing mean mMASI scores and improving melasma (P<.001). The reduction in mMASI scores for the group receiving intradermal injections of TXA (left side; 74.8% reduction in mean mMASI score) vs the group receiving microneedling application of TXA (right side; 73.6% reduction in mean mMASI score) was not statistically significant. These findings suggest that the mode of TXA application may not be critical in determining clinical responses to TXA treatment. Although there was no reported statistically significant difference in clinical outcomes between the 2 treatments, patient satisfaction was higher on the microneedling side. Only 8 of 50 participants (16%) experienced recurrence 3 months posttreatment.22

Saki et al23 compared the efficacy of topical hydroquinone (2%) to intradermal TXA injections in treating melasma. They found intradermal TXA injections to be a clinically effective mode of treatment.23

Sharma et al24 explored the efficacy and safety of oral TXA by randomly assigning 100 Indian patients (20 of whom withdrew before study completion) with melasma into 2 groups: group A received TXA 250 mg twice daily, and group B received intradermal microinjections of TXA (4 mg/mL) every 4 weeks. The MASI scores were assessed at 4-week intervals for a total of 12 weeks. There was a decrease in MASI scores in both groups, and there was no statistically significant difference in mean percentage reduction in MASI scores between the 2 routes of drug administration, further suggesting the effectiveness of TXA independent of administration route. Two patients in group A relapsed at 24 weeks, and there were no relapses in group B, which may suggest a minimal superiority of TXA plus microneedling at providing more sustainable results compared with oral TXA alone. A notable limitation of this study was a high dropout rate as well as lack of long-term follow-up with participants, limiting the generalizability of the conclusions.24

Cassiano et al25 assigned 64 women with melasma to 1 of 3 treatment groups or a control group to compare the effectiveness of microneedling (M group: 1.5 mm; 2 sessions), oral TXA (T group: 250 mg/d twice daily for 60 days), and a combination of microneedling (2 sessions) and oral TXA (MT group: 250 mg/d twice daily for 60 days)with placebo for clinically reducing melasma lesions. The intervention period was 60 days followed by a 60-day maintenance phase for a total study period of 120 days. The researchers evaluated mMASI scores, quality of life, and difference in colorimetric luminosity. All treatment groups showed a reduction in mMASI scores at both 30 days and 60 days, indicating improved melasma severity. The MT and T groups had more significant improvement at 30 days compared with the control group (P<.03), suggesting that microneedling plus TXA and TXA alone promote faster improvement in melasma lesions. By 60 days, the M, T, and MT groups outperformed the control group, with no significant differences between the M, T, and MT groups. However, at the 120-day maintenance follow-up, the T group did not maintain its improvement compared with the control group. The M and MT groups showed no significance difference in effectiveness at 120 days, suggesting that microneedling may promote less frequent relapse and sustained remission compared to TXA alone.25

Hydroquinone for Melasma—Additional studies on the use of TXA treatments show that TXA may be an equally effective alternative to the standard use of hydroquinone treatment. Shamsi Meymandi et al26 did not find a statistically significant difference in treatment with TXA plus microneedling vs the standard regimen of hydroquinone. More importantly, patient and physician satisfaction assessments were similar between the 2 groups. Compared to hydroquinone, nightly treatment is not necessary with microneedling and TXA.26