User login

Transplantation palliative care: The time is ripe

Over 10 years ago, a challenge was made in a surgical publication for increased collaboration between the fields of transplantation and palliative care.1

Since that time not much progress has been made bringing these fields together in a consistent way that would mutually benefit patients and the specialties. However, other progress has been made, particularly in the field of palliative care, which could brighten the prospects and broaden the opportunities to accomplish collaboration between palliative care and transplantation.

Growth of palliative services

During the past decade there has been a robust proliferation of hospital-based palliative care programs in the United States. In all, 67% of U.S. hospitals with 50 or more beds report palliative care teams, up from 63% in 2011 and 53% in 2008.

Only a decade ago, critical care and palliative care were generally considered mutually exclusive. Evidence is trickling in to suggest that this is no longer the case. Although palliative care was not an integral part of critical care at that time, patients, families, and even practitioners began to demand these services. Cook and Rocker have eloquently advocated the rightful place of palliative care in the ICU.2

Studies in recent years have shown that the integration of palliative care into critical care decreases in length of ICU and hospital stay, decreases costs, enhances patient/family satisfaction, and promotes a more rapid consensus about goals of care, without increasing mortality. The ICU experience to date could be considered a reassuring precedent for transplantation palliative care.

Integration of palliative care with transplantation

Early palliative care intervention has been shown to improve symptom burden and depression scores in end-stage liver disease patients awaiting transplant. In addition, early palliative care consultation in conjunction with cancer treatment has been associated with increased survival in non–small-cell lung cancer patients. It has been demonstrated that early integration of palliative care in the surgical ICU alongside disease-directed curative care can be accomplished without change in mortality, while improving end-of-life practice in liver transplant patients.3

What palliative care can do for transplant patients

What does palliative care mean for the person (and family) awaiting transplantation? For the cirrhotic patient with cachexia, ascites, and encephalopathy, it means access to the services of a team trained in the management of these symptoms. Palliative care teams can also provide psychosocial and spiritual support for patients and families who are intimidated by the complex navigation of the health care system and the existential threat that end-stage organ failure presents to them. Skilled palliative care and services can be the difference between failing and extended life with a higher quality of life for these very sick patients

Resuscitation of a patient, whether through restoration of organ function or interdicting the progression of disease, begins with resuscitation of hope. Nothing achieves this more quickly than amelioration of burdensome symptoms for the patient and family.

The barriers for transplant surgeons and teams referring and incorporating palliative care services in their practices are multiple and profound. The unique dilemma facing the transplant team is to balance the treatment of the failing organ, the treatment of the patient (and family and friends), and the best use of the graft, a precious gift of society.

Palliative surgery has been defined as any invasive procedure in which the main intention is to mitigate physical symptoms in patients with noncurable disease without causing premature death. The very success of transplantation over the past 3 decades has obscured our memory of transplantation as a type of palliative surgery. It is a well-known axiom of reconstructive surgery that the reconstructed site should be compared to what was there, not to “normal.” Even in the current era of improved immunosuppression and posttransplant support services, one could hardly describe even a successful transplant patient’s experience as “normal.” These patients’ lives may be extended and/or enhanced but they need palliative care before, during, and after transplantation. The growing availability of trained palliative care clinicians and teams, the increased familiarity of palliative and end-of-life care to surgical residents and fellows, and quality metrics measuring palliative care outcomes will provide reassurance and guidance to address reservations about the convergence of the two seemingly opposite realities.

A modest proposal

We propose that palliative care be presented to the entire spectrum of transplantation care: on the ward, in the ICU, and after transplantation. More specific “triggers” for palliative care for referral of transplant patients should be identified. Wentlandt et al.4 have described a promising model for an ambulatory clinic, which provides early, integrated palliative care to patients awaiting and receiving organ transplantation. In addition, we propose an application for grant funding for a conference and eventual formation of a work group of transplant surgeons and team members, palliative care clinicians, and patient/families who have experienced one of the aspects of the transplant spectrum. We await the subspecialty certification in hospice and palliative medicine of a transplant surgeon. Outside of transplantation, every other surgical specialty in the United States has diplomates certified in hospice and palliative medicine. We await the benefits that will accrue from research about the merging of these fields.

1. Molmenti EP, Dunn GP: Transplantation and palliative care: The convergence of two seemingly opposite realities. Surg Clin North Am. 2005;85:373-82.

2. Cook D, Rocker G. Dying with dignity in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2506-14.

3. Lamba S, Murphy P, McVicker S, Smith JH, and Mosenthal AC. Changing end-of-life care practice for liver transplant patients: structured palliative care intervention in the surgical intensive care unit. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012; 44(4):508-19.

4. Wentlandt, K., Dall’Osto, A., Freeman, N., Le, L. W., Kaya, E., Ross, H., Singer, L. G., Abbey, S., Clarke, H. and Zimmermann, C. (2016), The Transplant Palliative Care Clinic: An early palliative care model for patients in a transplant program. Clin Transplant. 2016 Nov 4; doi: 10.1111/ctr.12838.

Dr. Azoulay is a transplantation specialist of Assistance Publique – Hôpitaux de Paris, and the University of Paris. Dr. Dunn is medical director of the Palliative Care Consultation Service at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Hamot, and vice-chair of the ACS Committee on Surgical Palliative Care.

Over 10 years ago, a challenge was made in a surgical publication for increased collaboration between the fields of transplantation and palliative care.1

Since that time not much progress has been made bringing these fields together in a consistent way that would mutually benefit patients and the specialties. However, other progress has been made, particularly in the field of palliative care, which could brighten the prospects and broaden the opportunities to accomplish collaboration between palliative care and transplantation.

Growth of palliative services

During the past decade there has been a robust proliferation of hospital-based palliative care programs in the United States. In all, 67% of U.S. hospitals with 50 or more beds report palliative care teams, up from 63% in 2011 and 53% in 2008.

Only a decade ago, critical care and palliative care were generally considered mutually exclusive. Evidence is trickling in to suggest that this is no longer the case. Although palliative care was not an integral part of critical care at that time, patients, families, and even practitioners began to demand these services. Cook and Rocker have eloquently advocated the rightful place of palliative care in the ICU.2

Studies in recent years have shown that the integration of palliative care into critical care decreases in length of ICU and hospital stay, decreases costs, enhances patient/family satisfaction, and promotes a more rapid consensus about goals of care, without increasing mortality. The ICU experience to date could be considered a reassuring precedent for transplantation palliative care.

Integration of palliative care with transplantation

Early palliative care intervention has been shown to improve symptom burden and depression scores in end-stage liver disease patients awaiting transplant. In addition, early palliative care consultation in conjunction with cancer treatment has been associated with increased survival in non–small-cell lung cancer patients. It has been demonstrated that early integration of palliative care in the surgical ICU alongside disease-directed curative care can be accomplished without change in mortality, while improving end-of-life practice in liver transplant patients.3

What palliative care can do for transplant patients

What does palliative care mean for the person (and family) awaiting transplantation? For the cirrhotic patient with cachexia, ascites, and encephalopathy, it means access to the services of a team trained in the management of these symptoms. Palliative care teams can also provide psychosocial and spiritual support for patients and families who are intimidated by the complex navigation of the health care system and the existential threat that end-stage organ failure presents to them. Skilled palliative care and services can be the difference between failing and extended life with a higher quality of life for these very sick patients

Resuscitation of a patient, whether through restoration of organ function or interdicting the progression of disease, begins with resuscitation of hope. Nothing achieves this more quickly than amelioration of burdensome symptoms for the patient and family.

The barriers for transplant surgeons and teams referring and incorporating palliative care services in their practices are multiple and profound. The unique dilemma facing the transplant team is to balance the treatment of the failing organ, the treatment of the patient (and family and friends), and the best use of the graft, a precious gift of society.

Palliative surgery has been defined as any invasive procedure in which the main intention is to mitigate physical symptoms in patients with noncurable disease without causing premature death. The very success of transplantation over the past 3 decades has obscured our memory of transplantation as a type of palliative surgery. It is a well-known axiom of reconstructive surgery that the reconstructed site should be compared to what was there, not to “normal.” Even in the current era of improved immunosuppression and posttransplant support services, one could hardly describe even a successful transplant patient’s experience as “normal.” These patients’ lives may be extended and/or enhanced but they need palliative care before, during, and after transplantation. The growing availability of trained palliative care clinicians and teams, the increased familiarity of palliative and end-of-life care to surgical residents and fellows, and quality metrics measuring palliative care outcomes will provide reassurance and guidance to address reservations about the convergence of the two seemingly opposite realities.

A modest proposal

We propose that palliative care be presented to the entire spectrum of transplantation care: on the ward, in the ICU, and after transplantation. More specific “triggers” for palliative care for referral of transplant patients should be identified. Wentlandt et al.4 have described a promising model for an ambulatory clinic, which provides early, integrated palliative care to patients awaiting and receiving organ transplantation. In addition, we propose an application for grant funding for a conference and eventual formation of a work group of transplant surgeons and team members, palliative care clinicians, and patient/families who have experienced one of the aspects of the transplant spectrum. We await the subspecialty certification in hospice and palliative medicine of a transplant surgeon. Outside of transplantation, every other surgical specialty in the United States has diplomates certified in hospice and palliative medicine. We await the benefits that will accrue from research about the merging of these fields.

1. Molmenti EP, Dunn GP: Transplantation and palliative care: The convergence of two seemingly opposite realities. Surg Clin North Am. 2005;85:373-82.

2. Cook D, Rocker G. Dying with dignity in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2506-14.

3. Lamba S, Murphy P, McVicker S, Smith JH, and Mosenthal AC. Changing end-of-life care practice for liver transplant patients: structured palliative care intervention in the surgical intensive care unit. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012; 44(4):508-19.

4. Wentlandt, K., Dall’Osto, A., Freeman, N., Le, L. W., Kaya, E., Ross, H., Singer, L. G., Abbey, S., Clarke, H. and Zimmermann, C. (2016), The Transplant Palliative Care Clinic: An early palliative care model for patients in a transplant program. Clin Transplant. 2016 Nov 4; doi: 10.1111/ctr.12838.

Dr. Azoulay is a transplantation specialist of Assistance Publique – Hôpitaux de Paris, and the University of Paris. Dr. Dunn is medical director of the Palliative Care Consultation Service at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Hamot, and vice-chair of the ACS Committee on Surgical Palliative Care.

Over 10 years ago, a challenge was made in a surgical publication for increased collaboration between the fields of transplantation and palliative care.1

Since that time not much progress has been made bringing these fields together in a consistent way that would mutually benefit patients and the specialties. However, other progress has been made, particularly in the field of palliative care, which could brighten the prospects and broaden the opportunities to accomplish collaboration between palliative care and transplantation.

Growth of palliative services

During the past decade there has been a robust proliferation of hospital-based palliative care programs in the United States. In all, 67% of U.S. hospitals with 50 or more beds report palliative care teams, up from 63% in 2011 and 53% in 2008.

Only a decade ago, critical care and palliative care were generally considered mutually exclusive. Evidence is trickling in to suggest that this is no longer the case. Although palliative care was not an integral part of critical care at that time, patients, families, and even practitioners began to demand these services. Cook and Rocker have eloquently advocated the rightful place of palliative care in the ICU.2

Studies in recent years have shown that the integration of palliative care into critical care decreases in length of ICU and hospital stay, decreases costs, enhances patient/family satisfaction, and promotes a more rapid consensus about goals of care, without increasing mortality. The ICU experience to date could be considered a reassuring precedent for transplantation palliative care.

Integration of palliative care with transplantation

Early palliative care intervention has been shown to improve symptom burden and depression scores in end-stage liver disease patients awaiting transplant. In addition, early palliative care consultation in conjunction with cancer treatment has been associated with increased survival in non–small-cell lung cancer patients. It has been demonstrated that early integration of palliative care in the surgical ICU alongside disease-directed curative care can be accomplished without change in mortality, while improving end-of-life practice in liver transplant patients.3

What palliative care can do for transplant patients

What does palliative care mean for the person (and family) awaiting transplantation? For the cirrhotic patient with cachexia, ascites, and encephalopathy, it means access to the services of a team trained in the management of these symptoms. Palliative care teams can also provide psychosocial and spiritual support for patients and families who are intimidated by the complex navigation of the health care system and the existential threat that end-stage organ failure presents to them. Skilled palliative care and services can be the difference between failing and extended life with a higher quality of life for these very sick patients

Resuscitation of a patient, whether through restoration of organ function or interdicting the progression of disease, begins with resuscitation of hope. Nothing achieves this more quickly than amelioration of burdensome symptoms for the patient and family.

The barriers for transplant surgeons and teams referring and incorporating palliative care services in their practices are multiple and profound. The unique dilemma facing the transplant team is to balance the treatment of the failing organ, the treatment of the patient (and family and friends), and the best use of the graft, a precious gift of society.

Palliative surgery has been defined as any invasive procedure in which the main intention is to mitigate physical symptoms in patients with noncurable disease without causing premature death. The very success of transplantation over the past 3 decades has obscured our memory of transplantation as a type of palliative surgery. It is a well-known axiom of reconstructive surgery that the reconstructed site should be compared to what was there, not to “normal.” Even in the current era of improved immunosuppression and posttransplant support services, one could hardly describe even a successful transplant patient’s experience as “normal.” These patients’ lives may be extended and/or enhanced but they need palliative care before, during, and after transplantation. The growing availability of trained palliative care clinicians and teams, the increased familiarity of palliative and end-of-life care to surgical residents and fellows, and quality metrics measuring palliative care outcomes will provide reassurance and guidance to address reservations about the convergence of the two seemingly opposite realities.

A modest proposal

We propose that palliative care be presented to the entire spectrum of transplantation care: on the ward, in the ICU, and after transplantation. More specific “triggers” for palliative care for referral of transplant patients should be identified. Wentlandt et al.4 have described a promising model for an ambulatory clinic, which provides early, integrated palliative care to patients awaiting and receiving organ transplantation. In addition, we propose an application for grant funding for a conference and eventual formation of a work group of transplant surgeons and team members, palliative care clinicians, and patient/families who have experienced one of the aspects of the transplant spectrum. We await the subspecialty certification in hospice and palliative medicine of a transplant surgeon. Outside of transplantation, every other surgical specialty in the United States has diplomates certified in hospice and palliative medicine. We await the benefits that will accrue from research about the merging of these fields.

1. Molmenti EP, Dunn GP: Transplantation and palliative care: The convergence of two seemingly opposite realities. Surg Clin North Am. 2005;85:373-82.

2. Cook D, Rocker G. Dying with dignity in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2506-14.

3. Lamba S, Murphy P, McVicker S, Smith JH, and Mosenthal AC. Changing end-of-life care practice for liver transplant patients: structured palliative care intervention in the surgical intensive care unit. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012; 44(4):508-19.

4. Wentlandt, K., Dall’Osto, A., Freeman, N., Le, L. W., Kaya, E., Ross, H., Singer, L. G., Abbey, S., Clarke, H. and Zimmermann, C. (2016), The Transplant Palliative Care Clinic: An early palliative care model for patients in a transplant program. Clin Transplant. 2016 Nov 4; doi: 10.1111/ctr.12838.

Dr. Azoulay is a transplantation specialist of Assistance Publique – Hôpitaux de Paris, and the University of Paris. Dr. Dunn is medical director of the Palliative Care Consultation Service at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Hamot, and vice-chair of the ACS Committee on Surgical Palliative Care.

SVS Now Accepting Abstracts for VAM 2017

Abstracts for the 2017 Vascular Annual Meeting are now being accepted. The submission site opened Monday, Nov. 14 for the meeting, to be held May 31 to June 3, 2017, in San Diego. Plenary sessions and exhibits will be June 1 to 3.

Participants may submit abstracts into any of 14 categories and a number of presentation types, including videos. In 2016, organizers selected approximately two-thirds of the submitted abstracts, and this year the VAM Program Committee is seeking additional venues for people to present their work in, including more sessions and other presentation formats.

Click here for abstract guidelines and more information. Abstracts themselves may be submitted here.

Abstracts for the 2017 Vascular Annual Meeting are now being accepted. The submission site opened Monday, Nov. 14 for the meeting, to be held May 31 to June 3, 2017, in San Diego. Plenary sessions and exhibits will be June 1 to 3.

Participants may submit abstracts into any of 14 categories and a number of presentation types, including videos. In 2016, organizers selected approximately two-thirds of the submitted abstracts, and this year the VAM Program Committee is seeking additional venues for people to present their work in, including more sessions and other presentation formats.

Click here for abstract guidelines and more information. Abstracts themselves may be submitted here.

Abstracts for the 2017 Vascular Annual Meeting are now being accepted. The submission site opened Monday, Nov. 14 for the meeting, to be held May 31 to June 3, 2017, in San Diego. Plenary sessions and exhibits will be June 1 to 3.

Participants may submit abstracts into any of 14 categories and a number of presentation types, including videos. In 2016, organizers selected approximately two-thirds of the submitted abstracts, and this year the VAM Program Committee is seeking additional venues for people to present their work in, including more sessions and other presentation formats.

Click here for abstract guidelines and more information. Abstracts themselves may be submitted here.

Best Practices: Protecting Dry Vulnerable Skin with CeraVe® Healing Ointment

A supplement to Dermatology News. This advertising supplement is sponsored by Valeant Pharmaceuticals.

- Reinforcing the Skin Barrier

- NEA Seal of Acceptance

- A Preventative Approach to Dry, Cracked Skin

- CeraVe Ointment in the Clinical Setting

Faculty/Faculty Disclosure

Sheila Fallon Friedlander, MD

Professor of Clinical Dermatology & Pediatrics

Director, Pediatric Dermatology Fellowship Training Program

University of California at San Diego School of Medicine

Rady Children’s Hospital,

San Diego, California

Dr. Friedlander was compensated for her participation in the development of this article.

CeraVe is a registered trademark of Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc. or its affiliates.

A supplement to Dermatology News. This advertising supplement is sponsored by Valeant Pharmaceuticals.

- Reinforcing the Skin Barrier

- NEA Seal of Acceptance

- A Preventative Approach to Dry, Cracked Skin

- CeraVe Ointment in the Clinical Setting

Faculty/Faculty Disclosure

Sheila Fallon Friedlander, MD

Professor of Clinical Dermatology & Pediatrics

Director, Pediatric Dermatology Fellowship Training Program

University of California at San Diego School of Medicine

Rady Children’s Hospital,

San Diego, California

Dr. Friedlander was compensated for her participation in the development of this article.

CeraVe is a registered trademark of Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc. or its affiliates.

A supplement to Dermatology News. This advertising supplement is sponsored by Valeant Pharmaceuticals.

- Reinforcing the Skin Barrier

- NEA Seal of Acceptance

- A Preventative Approach to Dry, Cracked Skin

- CeraVe Ointment in the Clinical Setting

Faculty/Faculty Disclosure

Sheila Fallon Friedlander, MD

Professor of Clinical Dermatology & Pediatrics

Director, Pediatric Dermatology Fellowship Training Program

University of California at San Diego School of Medicine

Rady Children’s Hospital,

San Diego, California

Dr. Friedlander was compensated for her participation in the development of this article.

CeraVe is a registered trademark of Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc. or its affiliates.

Thoracic Intramedullary Mass Causing Neurologic Weakness

Thoracic Intramedullary Mass Causing Neurologic Weakness

Discussion

A diagnosis of dural arteriovenous fistula (dAVF) was made. Lesions involving the spinal cord are traditionally classified by location as extradural, intradural/extramedullary, or intramedullary. Intramedullary spinal cord abnormalities pose considerable diagnostic and management challenges because of the risks of biopsy in this location and the added potential for morbidity and mortality from improperly treated lesions. Although MRI is the preferred imaging modality, PET/CT and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) may also help narrow the differential diagnosis and potentially avoid complications from an invasive biopsy.1 This patient’s intramedullary lesion, which represented a dAVF, posed a diagnostic challenge; after diagnosis, it was successfully managed conservatively with dexamethasone and physical therapy.

Intradural tumors account for 2% to 4% of all primary central nervous system (CNS) tumors.2 Ependymomas account for 50% to 60% of intramedullary tumors in adults, while astrocytomas account for about 60% of all lesions in children and adolescents.3,4 The differential diagnosis for intramedullary tumors also includes hemangioblastoma, metastases, primary CNS lymphoma, germ cell tumors, and gangliogliomas.5,6

Intramedullary metastases remain rare, although the incidence is rising with improvements in oncologic and supportive treatments. Autopsy studies conducted decades ago demonstrated that about 0.9% to 2.1% of patients with systemic cancer have intramedullary metastases at death.7,8 In patients with an established history of malignancy, a metastatic intramedullary tumor should be placed higher on the differential diagnosis. Intramedullary metastases most often occur in the setting of widespread metastatic disease. A systematic review of the literature on patients with lung cancer (small cell and non-small cell lung carcinomas) and ≥ 1 intramedullary spinal cord metastasis demonstrated that 55.8% of patients had concurrent brain metastases, 20.0% had leptomeningeal carcinomatosis, and 19.5% had vertebral metastases.9 While about half of all intramedullary metastases are associated with lung cancer, other common malignancies that metastasize to this area include colorectal, breast, and renal cell carcinoma, as well as lymphoma and melanoma primaries.10,11

On imaging, intramedullary metastases often appear as several short, studded segments with surrounding edema, typically out of proportion to the size of the lesion.1 By contrast, astrocytomas and ependymomas often span multiple segments, and enhancement patterns can vary depending on the subtype and grade. Glioblastoma multiforme, or grade 4 IDH wild-type astrocytomas, demonstrate an irregular, heterogeneous pattern of enhancement. Hemangioblastomas vary in size and are classically hypointense to isointense on T1-weighted sequences, isointense to hyperintense on T2-weighted sequences, and demonstrate avid enhancement on T1- postcontrast images. In large hemangioblastomas, flow voids due to prominent vasculature may be visualized.

Numerous nonneoplastic tumor mimics can obscure the differential diagnosis. Vascular malformations, including cavernomas and dAVFs, can also present with enhancement and edema. dAVFs are the most common type of spinal vascular malformation, accounting for about 70% of cases.12 They are supplied by the radiculomeningeal arteries, whereas pial arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are supplied by the radiculomedullary and radiculopial arteries. On MRI, dAVFs usually have venous congestion with intramedullary edema, which appears as an ill-defined centromedullary hyperintensity on T2-weighted imaging over multiple segments. The spinal cord may appear swollen with atrophic changes in chronic cases. Spinal cord AVMs are rarer and have an intramedullary nidus. They usually demonstrate mixed heterogeneous signal on T1- and T2-weighted imaging due to blood products, while the nidus demonstrates a variable degree of enhancement. Serpiginous flow voids are seen both within the nidus and at the cord surface.

Demyelinating lesions of the spine may be seen in neuroinflammatory conditions such as multiple sclerosis, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder, acute transverse myelitis, and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. In multiple sclerosis, lesions typically extend ≤ 2 vertebral segments in length, cover less than half of the vertebral cross-sectional area, and have a dorsolateral predilection.13 Active lesions may demonstrate enhancement along the rim or in a patchy pattern. In the presence of demyelinating lesions, there may occasionally appear to be an expansile mass with a syrinx.14

Infections such as tuberculosis and neurosarcoidosis should also remain on the differential diagnosis. On MRI, tuberculosis usually involves the thoracic cord and is typically rim-enhancing.15 If there are caseating granulomas, T2-weighted images may also demonstrate rim enhancement.16 Spinal sarcoidosis is unusual without intracranial involvement, and its appearance may include leptomeningeal enhancement, cord expansion, and hyperintense signal on T2- weighted imaging.17

Finally, iatrogenic causes are also possible, including radiation myelopathy and mechanical spinal cord injury. For radiation myelopathy, it is important to ascertain whether a patient has undergone prior radiotherapy in the region and to obtain the pertinent dosimetry. Spinal cord injury may cause a focal signal abnormality within the cord, with T2 hyperintensity; these foci may or may not present with enhancement, edema, or hematoma and therefore may resemble tumors.13

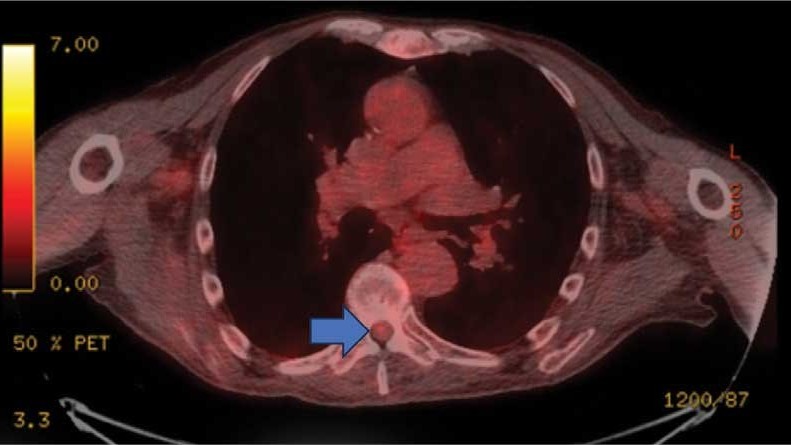

This patient presented with progressive right-sided lower extremity weakness and hypoesthesia and a history of a low-grade right renal/pelvic ureteral tumor. The immediate impression was that the thoracic intramedullary lesion represented a metastatic lesion. However, in the absence of any systemic or intracranial metastases, this progression was much less likely. An extensive interdisciplinary workup was conducted that included medical oncology, neurology, neuroradiology, neuro-oncology, neurosurgery, nuclear medicine, and radiation oncology. Neuroradiology and nuclear medicine identified a slightly hypermetabolic focus on the PET/CT from 1.5 years prior that correlated exactly with the same location as the lesion on the recent spinal MRI. This finding, along with the MRA, confirmed the diagnosis of a dAVF, which was successfully managed conservatively with dexamethasone and physical therapy, rather than through oncologic treatments such as radiotherapy

There remains debate regarding the utility of steroids in treating patients with dAVF. Although there are some case reports documenting that the edema associated with the dAVF responds to steroids, other case series have found that steroids may worsen outcomes in patients with dAVF, possibly due to increased venous hydrostatic pressure.

This case demonstrates the importance of an interdisciplinary workup when evaluating an intramedullary lesion, as well as maintaining a wide differential diagnosis, particularly in the absence of a history of polymetastatic cancer. All the clues (such as the slightly hypermetabolic focus on a PET/CT from 1.5 years prior) need to be obtained to comfortably reach a diagnosis in the absence of pathologic confirmation. These cases can be especially challenging due to the lack of pathologic confirmation, but by understanding the main differentiating features among the various etiologies and obtaining all available information, a correct diagnosis can be made without unnecessary interventions.

- Moghaddam SM, Bhatt AA. Location, length, and enhancement: systematic approach to differentiating intramedullary spinal cord lesions. Insights Imaging. 2018;9:511-526. doi:10.1007/s13244-018-0608-3

- Grimm S, Chamberlain MC. Adult primary spinal cord tumors. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9:1487-1495. doi:10.1586/ern.09.101

- Miller DJ, McCutcheon IE. Hemangioblastomas and other uncommon intramedullary tumors. J Neurooncol. 2000;47:253- 270. doi:10.1023/a:1006403500801

- Mottl H, Koutecky J. Treatment of spinal cord tumors in children. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;29:293-295.

- Kandemirli SG, Reddy A, Hitchon P, et al. Intramedullary tumours and tumour mimics. Clin Radiol. 2020;75:876.e17-876. e32. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2020.05.010

- Tobin MK, Geraghty JR, Engelhard HH, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord tumors: a review of current and future treatment strategies. Neurosurg Focus. 2015;39:E14. doi:10.3171/2015.5.FOCUS15158

- Chason JL, Walker FB, Landers JW. Metastatic carcinoma in the central nervous system and dorsal root ganglia. A prospective autopsy study. Cancer. 1963;16:781-787.

- Costigan DA, Winkelman MD. Intramedullary spinal cord metastasis. A clinicopathological study of 13 cases. J Neurosurg. 1985;62:227-233.

- Wu L, Wang L, Yang J, et al. Clinical features, treatments, and prognosis of intramedullary spinal cord metastases from lung cancer: a case series and systematic review. Neurospine. 2022;19:65-76. doi:10.14245/ns.2142910.455

- Lv J, Liu B, Quan X, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord metastasis in malignancies: an institutional analysis and review. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:4741-4753. doi:10.2147/OTT.S193235

- Goyal A, Yolcu Y, Kerezoudis P, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord metastases: an institutional review of survival and outcomes. J Neurooncol. 2019;142:347-354. doi:10.1007/s11060-019-03105-2

- Krings T. Vascular malformations of the spine and spinal cord: anatomy, classification, treatment. Clin Neuroradiol. 2010;20:5-24. doi:10.1007/s00062-010-9036-6

- Maj E, Wojtowicz K, Aleksandra PP, et al. Intramedullary spinal tumor-like lesions. Acta Radiol. 2019;60:994-1010. doi:10.1177/0284185118809540

- Waziri A, Vonsattel JP, Kaiser MG, et al. Expansile, enhancing cervical cord lesion with an associated syrinx secondary to demyelination. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;6:52-56. doi:10.3171/spi.2007.6.1.52

- Nussbaum ES, Rockswold GL, Bergman TA, et al. Spinal tuberculosis: a diagnostic and management challenge. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:243-247. doi:10.3171/jns.1995.83.2.0243

- Lu M. Imaging diagnosis of spinal intramedullary tuberculoma: case reports and literature review. J Spinal Cord Med. 2010;33:159-162. doi:10.1080/10790268.2010.11689691

- Do-Dai DD, Brooks MK, Goldkamp A, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of intramedullary spinal cord lesions: a pictorial review. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2010;39:160-185. doi:10.1067/j.cpradiol.2009.05.004

Discussion

A diagnosis of dural arteriovenous fistula (dAVF) was made. Lesions involving the spinal cord are traditionally classified by location as extradural, intradural/extramedullary, or intramedullary. Intramedullary spinal cord abnormalities pose considerable diagnostic and management challenges because of the risks of biopsy in this location and the added potential for morbidity and mortality from improperly treated lesions. Although MRI is the preferred imaging modality, PET/CT and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) may also help narrow the differential diagnosis and potentially avoid complications from an invasive biopsy.1 This patient’s intramedullary lesion, which represented a dAVF, posed a diagnostic challenge; after diagnosis, it was successfully managed conservatively with dexamethasone and physical therapy.

Intradural tumors account for 2% to 4% of all primary central nervous system (CNS) tumors.2 Ependymomas account for 50% to 60% of intramedullary tumors in adults, while astrocytomas account for about 60% of all lesions in children and adolescents.3,4 The differential diagnosis for intramedullary tumors also includes hemangioblastoma, metastases, primary CNS lymphoma, germ cell tumors, and gangliogliomas.5,6

Intramedullary metastases remain rare, although the incidence is rising with improvements in oncologic and supportive treatments. Autopsy studies conducted decades ago demonstrated that about 0.9% to 2.1% of patients with systemic cancer have intramedullary metastases at death.7,8 In patients with an established history of malignancy, a metastatic intramedullary tumor should be placed higher on the differential diagnosis. Intramedullary metastases most often occur in the setting of widespread metastatic disease. A systematic review of the literature on patients with lung cancer (small cell and non-small cell lung carcinomas) and ≥ 1 intramedullary spinal cord metastasis demonstrated that 55.8% of patients had concurrent brain metastases, 20.0% had leptomeningeal carcinomatosis, and 19.5% had vertebral metastases.9 While about half of all intramedullary metastases are associated with lung cancer, other common malignancies that metastasize to this area include colorectal, breast, and renal cell carcinoma, as well as lymphoma and melanoma primaries.10,11

On imaging, intramedullary metastases often appear as several short, studded segments with surrounding edema, typically out of proportion to the size of the lesion.1 By contrast, astrocytomas and ependymomas often span multiple segments, and enhancement patterns can vary depending on the subtype and grade. Glioblastoma multiforme, or grade 4 IDH wild-type astrocytomas, demonstrate an irregular, heterogeneous pattern of enhancement. Hemangioblastomas vary in size and are classically hypointense to isointense on T1-weighted sequences, isointense to hyperintense on T2-weighted sequences, and demonstrate avid enhancement on T1- postcontrast images. In large hemangioblastomas, flow voids due to prominent vasculature may be visualized.

Numerous nonneoplastic tumor mimics can obscure the differential diagnosis. Vascular malformations, including cavernomas and dAVFs, can also present with enhancement and edema. dAVFs are the most common type of spinal vascular malformation, accounting for about 70% of cases.12 They are supplied by the radiculomeningeal arteries, whereas pial arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are supplied by the radiculomedullary and radiculopial arteries. On MRI, dAVFs usually have venous congestion with intramedullary edema, which appears as an ill-defined centromedullary hyperintensity on T2-weighted imaging over multiple segments. The spinal cord may appear swollen with atrophic changes in chronic cases. Spinal cord AVMs are rarer and have an intramedullary nidus. They usually demonstrate mixed heterogeneous signal on T1- and T2-weighted imaging due to blood products, while the nidus demonstrates a variable degree of enhancement. Serpiginous flow voids are seen both within the nidus and at the cord surface.

Demyelinating lesions of the spine may be seen in neuroinflammatory conditions such as multiple sclerosis, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder, acute transverse myelitis, and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. In multiple sclerosis, lesions typically extend ≤ 2 vertebral segments in length, cover less than half of the vertebral cross-sectional area, and have a dorsolateral predilection.13 Active lesions may demonstrate enhancement along the rim or in a patchy pattern. In the presence of demyelinating lesions, there may occasionally appear to be an expansile mass with a syrinx.14

Infections such as tuberculosis and neurosarcoidosis should also remain on the differential diagnosis. On MRI, tuberculosis usually involves the thoracic cord and is typically rim-enhancing.15 If there are caseating granulomas, T2-weighted images may also demonstrate rim enhancement.16 Spinal sarcoidosis is unusual without intracranial involvement, and its appearance may include leptomeningeal enhancement, cord expansion, and hyperintense signal on T2- weighted imaging.17

Finally, iatrogenic causes are also possible, including radiation myelopathy and mechanical spinal cord injury. For radiation myelopathy, it is important to ascertain whether a patient has undergone prior radiotherapy in the region and to obtain the pertinent dosimetry. Spinal cord injury may cause a focal signal abnormality within the cord, with T2 hyperintensity; these foci may or may not present with enhancement, edema, or hematoma and therefore may resemble tumors.13

This patient presented with progressive right-sided lower extremity weakness and hypoesthesia and a history of a low-grade right renal/pelvic ureteral tumor. The immediate impression was that the thoracic intramedullary lesion represented a metastatic lesion. However, in the absence of any systemic or intracranial metastases, this progression was much less likely. An extensive interdisciplinary workup was conducted that included medical oncology, neurology, neuroradiology, neuro-oncology, neurosurgery, nuclear medicine, and radiation oncology. Neuroradiology and nuclear medicine identified a slightly hypermetabolic focus on the PET/CT from 1.5 years prior that correlated exactly with the same location as the lesion on the recent spinal MRI. This finding, along with the MRA, confirmed the diagnosis of a dAVF, which was successfully managed conservatively with dexamethasone and physical therapy, rather than through oncologic treatments such as radiotherapy

There remains debate regarding the utility of steroids in treating patients with dAVF. Although there are some case reports documenting that the edema associated with the dAVF responds to steroids, other case series have found that steroids may worsen outcomes in patients with dAVF, possibly due to increased venous hydrostatic pressure.

This case demonstrates the importance of an interdisciplinary workup when evaluating an intramedullary lesion, as well as maintaining a wide differential diagnosis, particularly in the absence of a history of polymetastatic cancer. All the clues (such as the slightly hypermetabolic focus on a PET/CT from 1.5 years prior) need to be obtained to comfortably reach a diagnosis in the absence of pathologic confirmation. These cases can be especially challenging due to the lack of pathologic confirmation, but by understanding the main differentiating features among the various etiologies and obtaining all available information, a correct diagnosis can be made without unnecessary interventions.

Discussion

A diagnosis of dural arteriovenous fistula (dAVF) was made. Lesions involving the spinal cord are traditionally classified by location as extradural, intradural/extramedullary, or intramedullary. Intramedullary spinal cord abnormalities pose considerable diagnostic and management challenges because of the risks of biopsy in this location and the added potential for morbidity and mortality from improperly treated lesions. Although MRI is the preferred imaging modality, PET/CT and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) may also help narrow the differential diagnosis and potentially avoid complications from an invasive biopsy.1 This patient’s intramedullary lesion, which represented a dAVF, posed a diagnostic challenge; after diagnosis, it was successfully managed conservatively with dexamethasone and physical therapy.

Intradural tumors account for 2% to 4% of all primary central nervous system (CNS) tumors.2 Ependymomas account for 50% to 60% of intramedullary tumors in adults, while astrocytomas account for about 60% of all lesions in children and adolescents.3,4 The differential diagnosis for intramedullary tumors also includes hemangioblastoma, metastases, primary CNS lymphoma, germ cell tumors, and gangliogliomas.5,6

Intramedullary metastases remain rare, although the incidence is rising with improvements in oncologic and supportive treatments. Autopsy studies conducted decades ago demonstrated that about 0.9% to 2.1% of patients with systemic cancer have intramedullary metastases at death.7,8 In patients with an established history of malignancy, a metastatic intramedullary tumor should be placed higher on the differential diagnosis. Intramedullary metastases most often occur in the setting of widespread metastatic disease. A systematic review of the literature on patients with lung cancer (small cell and non-small cell lung carcinomas) and ≥ 1 intramedullary spinal cord metastasis demonstrated that 55.8% of patients had concurrent brain metastases, 20.0% had leptomeningeal carcinomatosis, and 19.5% had vertebral metastases.9 While about half of all intramedullary metastases are associated with lung cancer, other common malignancies that metastasize to this area include colorectal, breast, and renal cell carcinoma, as well as lymphoma and melanoma primaries.10,11

On imaging, intramedullary metastases often appear as several short, studded segments with surrounding edema, typically out of proportion to the size of the lesion.1 By contrast, astrocytomas and ependymomas often span multiple segments, and enhancement patterns can vary depending on the subtype and grade. Glioblastoma multiforme, or grade 4 IDH wild-type astrocytomas, demonstrate an irregular, heterogeneous pattern of enhancement. Hemangioblastomas vary in size and are classically hypointense to isointense on T1-weighted sequences, isointense to hyperintense on T2-weighted sequences, and demonstrate avid enhancement on T1- postcontrast images. In large hemangioblastomas, flow voids due to prominent vasculature may be visualized.

Numerous nonneoplastic tumor mimics can obscure the differential diagnosis. Vascular malformations, including cavernomas and dAVFs, can also present with enhancement and edema. dAVFs are the most common type of spinal vascular malformation, accounting for about 70% of cases.12 They are supplied by the radiculomeningeal arteries, whereas pial arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are supplied by the radiculomedullary and radiculopial arteries. On MRI, dAVFs usually have venous congestion with intramedullary edema, which appears as an ill-defined centromedullary hyperintensity on T2-weighted imaging over multiple segments. The spinal cord may appear swollen with atrophic changes in chronic cases. Spinal cord AVMs are rarer and have an intramedullary nidus. They usually demonstrate mixed heterogeneous signal on T1- and T2-weighted imaging due to blood products, while the nidus demonstrates a variable degree of enhancement. Serpiginous flow voids are seen both within the nidus and at the cord surface.

Demyelinating lesions of the spine may be seen in neuroinflammatory conditions such as multiple sclerosis, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder, acute transverse myelitis, and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. In multiple sclerosis, lesions typically extend ≤ 2 vertebral segments in length, cover less than half of the vertebral cross-sectional area, and have a dorsolateral predilection.13 Active lesions may demonstrate enhancement along the rim or in a patchy pattern. In the presence of demyelinating lesions, there may occasionally appear to be an expansile mass with a syrinx.14

Infections such as tuberculosis and neurosarcoidosis should also remain on the differential diagnosis. On MRI, tuberculosis usually involves the thoracic cord and is typically rim-enhancing.15 If there are caseating granulomas, T2-weighted images may also demonstrate rim enhancement.16 Spinal sarcoidosis is unusual without intracranial involvement, and its appearance may include leptomeningeal enhancement, cord expansion, and hyperintense signal on T2- weighted imaging.17

Finally, iatrogenic causes are also possible, including radiation myelopathy and mechanical spinal cord injury. For radiation myelopathy, it is important to ascertain whether a patient has undergone prior radiotherapy in the region and to obtain the pertinent dosimetry. Spinal cord injury may cause a focal signal abnormality within the cord, with T2 hyperintensity; these foci may or may not present with enhancement, edema, or hematoma and therefore may resemble tumors.13

This patient presented with progressive right-sided lower extremity weakness and hypoesthesia and a history of a low-grade right renal/pelvic ureteral tumor. The immediate impression was that the thoracic intramedullary lesion represented a metastatic lesion. However, in the absence of any systemic or intracranial metastases, this progression was much less likely. An extensive interdisciplinary workup was conducted that included medical oncology, neurology, neuroradiology, neuro-oncology, neurosurgery, nuclear medicine, and radiation oncology. Neuroradiology and nuclear medicine identified a slightly hypermetabolic focus on the PET/CT from 1.5 years prior that correlated exactly with the same location as the lesion on the recent spinal MRI. This finding, along with the MRA, confirmed the diagnosis of a dAVF, which was successfully managed conservatively with dexamethasone and physical therapy, rather than through oncologic treatments such as radiotherapy

There remains debate regarding the utility of steroids in treating patients with dAVF. Although there are some case reports documenting that the edema associated with the dAVF responds to steroids, other case series have found that steroids may worsen outcomes in patients with dAVF, possibly due to increased venous hydrostatic pressure.

This case demonstrates the importance of an interdisciplinary workup when evaluating an intramedullary lesion, as well as maintaining a wide differential diagnosis, particularly in the absence of a history of polymetastatic cancer. All the clues (such as the slightly hypermetabolic focus on a PET/CT from 1.5 years prior) need to be obtained to comfortably reach a diagnosis in the absence of pathologic confirmation. These cases can be especially challenging due to the lack of pathologic confirmation, but by understanding the main differentiating features among the various etiologies and obtaining all available information, a correct diagnosis can be made without unnecessary interventions.

- Moghaddam SM, Bhatt AA. Location, length, and enhancement: systematic approach to differentiating intramedullary spinal cord lesions. Insights Imaging. 2018;9:511-526. doi:10.1007/s13244-018-0608-3

- Grimm S, Chamberlain MC. Adult primary spinal cord tumors. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9:1487-1495. doi:10.1586/ern.09.101

- Miller DJ, McCutcheon IE. Hemangioblastomas and other uncommon intramedullary tumors. J Neurooncol. 2000;47:253- 270. doi:10.1023/a:1006403500801

- Mottl H, Koutecky J. Treatment of spinal cord tumors in children. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;29:293-295.

- Kandemirli SG, Reddy A, Hitchon P, et al. Intramedullary tumours and tumour mimics. Clin Radiol. 2020;75:876.e17-876. e32. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2020.05.010

- Tobin MK, Geraghty JR, Engelhard HH, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord tumors: a review of current and future treatment strategies. Neurosurg Focus. 2015;39:E14. doi:10.3171/2015.5.FOCUS15158

- Chason JL, Walker FB, Landers JW. Metastatic carcinoma in the central nervous system and dorsal root ganglia. A prospective autopsy study. Cancer. 1963;16:781-787.

- Costigan DA, Winkelman MD. Intramedullary spinal cord metastasis. A clinicopathological study of 13 cases. J Neurosurg. 1985;62:227-233.

- Wu L, Wang L, Yang J, et al. Clinical features, treatments, and prognosis of intramedullary spinal cord metastases from lung cancer: a case series and systematic review. Neurospine. 2022;19:65-76. doi:10.14245/ns.2142910.455

- Lv J, Liu B, Quan X, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord metastasis in malignancies: an institutional analysis and review. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:4741-4753. doi:10.2147/OTT.S193235

- Goyal A, Yolcu Y, Kerezoudis P, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord metastases: an institutional review of survival and outcomes. J Neurooncol. 2019;142:347-354. doi:10.1007/s11060-019-03105-2

- Krings T. Vascular malformations of the spine and spinal cord: anatomy, classification, treatment. Clin Neuroradiol. 2010;20:5-24. doi:10.1007/s00062-010-9036-6

- Maj E, Wojtowicz K, Aleksandra PP, et al. Intramedullary spinal tumor-like lesions. Acta Radiol. 2019;60:994-1010. doi:10.1177/0284185118809540

- Waziri A, Vonsattel JP, Kaiser MG, et al. Expansile, enhancing cervical cord lesion with an associated syrinx secondary to demyelination. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;6:52-56. doi:10.3171/spi.2007.6.1.52

- Nussbaum ES, Rockswold GL, Bergman TA, et al. Spinal tuberculosis: a diagnostic and management challenge. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:243-247. doi:10.3171/jns.1995.83.2.0243

- Lu M. Imaging diagnosis of spinal intramedullary tuberculoma: case reports and literature review. J Spinal Cord Med. 2010;33:159-162. doi:10.1080/10790268.2010.11689691

- Do-Dai DD, Brooks MK, Goldkamp A, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of intramedullary spinal cord lesions: a pictorial review. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2010;39:160-185. doi:10.1067/j.cpradiol.2009.05.004

- Moghaddam SM, Bhatt AA. Location, length, and enhancement: systematic approach to differentiating intramedullary spinal cord lesions. Insights Imaging. 2018;9:511-526. doi:10.1007/s13244-018-0608-3

- Grimm S, Chamberlain MC. Adult primary spinal cord tumors. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9:1487-1495. doi:10.1586/ern.09.101

- Miller DJ, McCutcheon IE. Hemangioblastomas and other uncommon intramedullary tumors. J Neurooncol. 2000;47:253- 270. doi:10.1023/a:1006403500801

- Mottl H, Koutecky J. Treatment of spinal cord tumors in children. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;29:293-295.

- Kandemirli SG, Reddy A, Hitchon P, et al. Intramedullary tumours and tumour mimics. Clin Radiol. 2020;75:876.e17-876. e32. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2020.05.010

- Tobin MK, Geraghty JR, Engelhard HH, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord tumors: a review of current and future treatment strategies. Neurosurg Focus. 2015;39:E14. doi:10.3171/2015.5.FOCUS15158

- Chason JL, Walker FB, Landers JW. Metastatic carcinoma in the central nervous system and dorsal root ganglia. A prospective autopsy study. Cancer. 1963;16:781-787.

- Costigan DA, Winkelman MD. Intramedullary spinal cord metastasis. A clinicopathological study of 13 cases. J Neurosurg. 1985;62:227-233.

- Wu L, Wang L, Yang J, et al. Clinical features, treatments, and prognosis of intramedullary spinal cord metastases from lung cancer: a case series and systematic review. Neurospine. 2022;19:65-76. doi:10.14245/ns.2142910.455

- Lv J, Liu B, Quan X, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord metastasis in malignancies: an institutional analysis and review. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:4741-4753. doi:10.2147/OTT.S193235

- Goyal A, Yolcu Y, Kerezoudis P, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord metastases: an institutional review of survival and outcomes. J Neurooncol. 2019;142:347-354. doi:10.1007/s11060-019-03105-2

- Krings T. Vascular malformations of the spine and spinal cord: anatomy, classification, treatment. Clin Neuroradiol. 2010;20:5-24. doi:10.1007/s00062-010-9036-6

- Maj E, Wojtowicz K, Aleksandra PP, et al. Intramedullary spinal tumor-like lesions. Acta Radiol. 2019;60:994-1010. doi:10.1177/0284185118809540

- Waziri A, Vonsattel JP, Kaiser MG, et al. Expansile, enhancing cervical cord lesion with an associated syrinx secondary to demyelination. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;6:52-56. doi:10.3171/spi.2007.6.1.52

- Nussbaum ES, Rockswold GL, Bergman TA, et al. Spinal tuberculosis: a diagnostic and management challenge. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:243-247. doi:10.3171/jns.1995.83.2.0243

- Lu M. Imaging diagnosis of spinal intramedullary tuberculoma: case reports and literature review. J Spinal Cord Med. 2010;33:159-162. doi:10.1080/10790268.2010.11689691

- Do-Dai DD, Brooks MK, Goldkamp A, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of intramedullary spinal cord lesions: a pictorial review. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2010;39:160-185. doi:10.1067/j.cpradiol.2009.05.004

Thoracic Intramedullary Mass Causing Neurologic Weakness

Thoracic Intramedullary Mass Causing Neurologic Weakness

An 87-year-old man presented to the emergency department reporting a 1-month history of right lower extremity weakness, progressing to an inability to ambulate. The patient had a history of hyperlipidemia, hypertension, benign prostatic hyperplasia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, low-grade right urothelial carcinoma status postbiopsy 2 years earlier, and atrial fibrillation following cardioversion 6 years earlier without anticoagulation therapy. He also reported severe right groin pain and increasing urinary obstruction.

On admission, neurology evaluated the patient’s lower extremity strength as 5/5 on his left, 1/5 on his right hip, and 2/5 on his right knee, with hypoesthesia of his right lower extremity. Computed tomography (CT) with contrast of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis demonstrated moderate to severe right-sided hydronephrosis, possibly due to a proximal right ureteric mass; no evidence of systemic metastases was found. He underwent a gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine, which showed a mass at T7-T8, a mass effect in the central cord, and abnormal spinal cord enhancement from T7 through the conus medullaris. A review of fluorodeoxyglucose- 18 (FDG-18) positron emission tomography (PET)-CT imaging from 1.5 years prior showed a low-grade focus (Figures 1-3). A gadolinium-enhanced brain MRI did not demonstrate any intracranial metastatic disease, acute infarct, hemorrhage, mass effect, or extra-axial fluid collections.

Following the Hyperkalemia Trail: A Case Report of ECG Changes and Treatment Responses

Following the Hyperkalemia Trail: A Case Report of ECG Changes and Treatment Responses

Hyperkalemia involves elevated serum potassium levels (> 5.0 mEq/L) and represents an important electrolyte disturbance due to its potentially severe consequences, including cardiac effects that can lead to dysrhythmia and even asystole and death.1,2 In a US Medicare population, the prevalence of hyperkalemia has been estimated at 2.7% and is associated with substantial health care costs.3 The prevalence is even more marked in patients with preexisting conditions such as chronic kidney disease (CKD) and heart failure.4,5

Hyperkalemia can result from multiple factors, including impaired renal function, adrenal disease, adverse drug reactions of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) and other medications, and heritable mutations.6 Hyperkalemia poses a considerable clinical risk, associated with adverse outcomes such as myocardial infarction and increased mortality in patients with CKD.5,7,8 Electrocardiographic (ECG) changes associated with hyperkalemia play a vital role in guiding clinical decisions and treatment strategies.9 Understanding the pathophysiology, risk factors, and consequences of hyperkalemia, as well as the significance of ECG changes in its management, is essential for health care practitioners.

Case Presentation

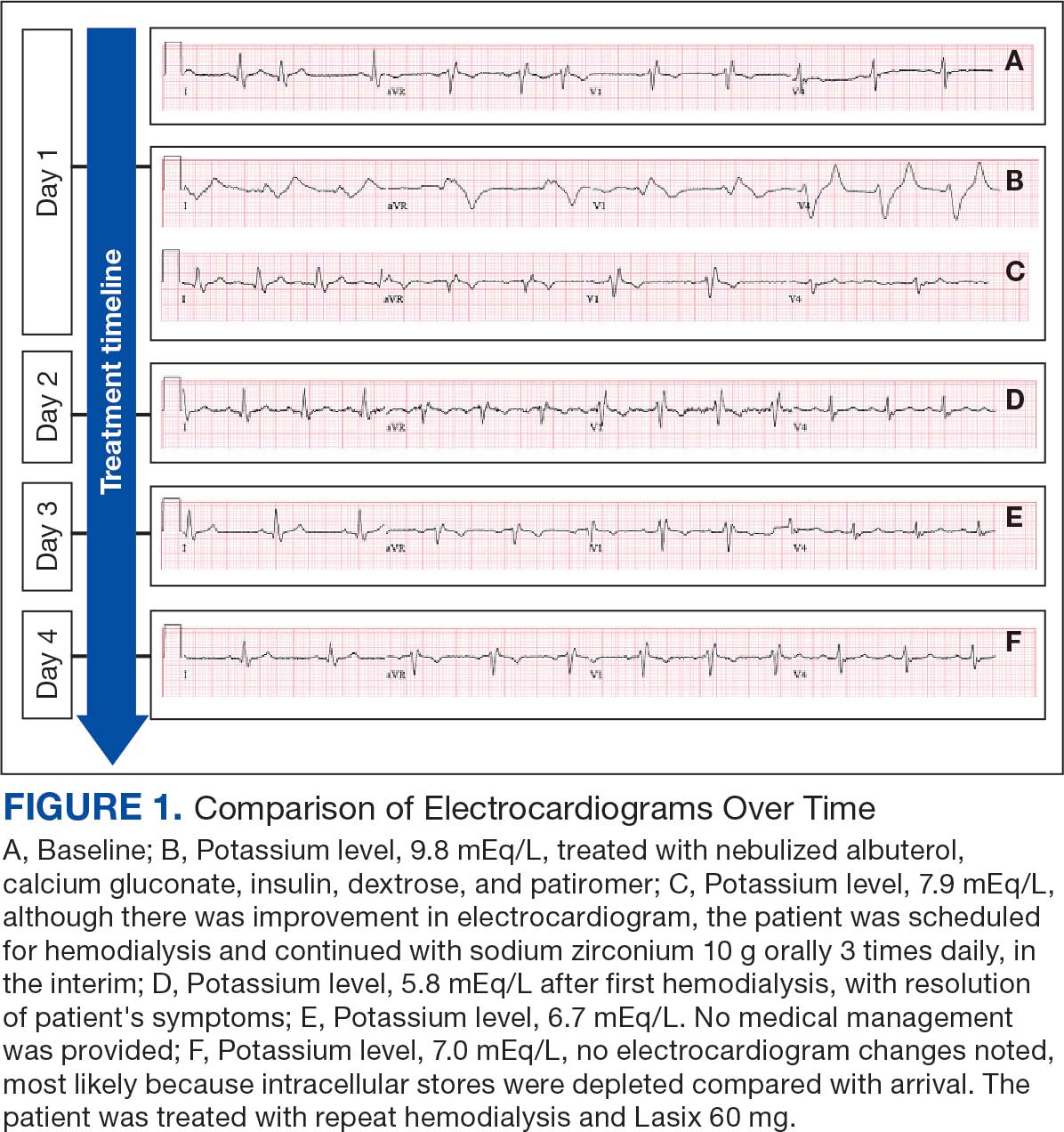

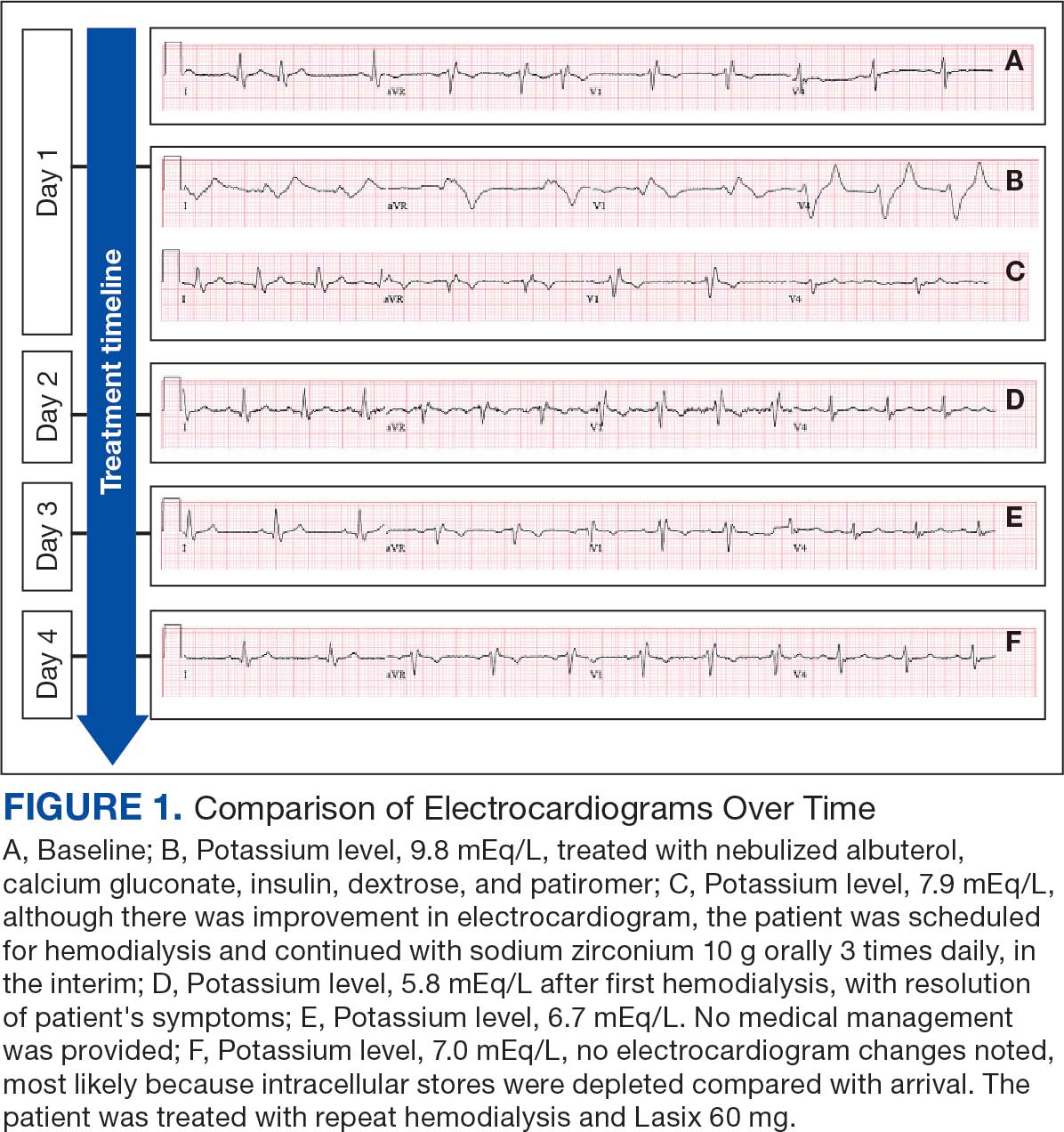

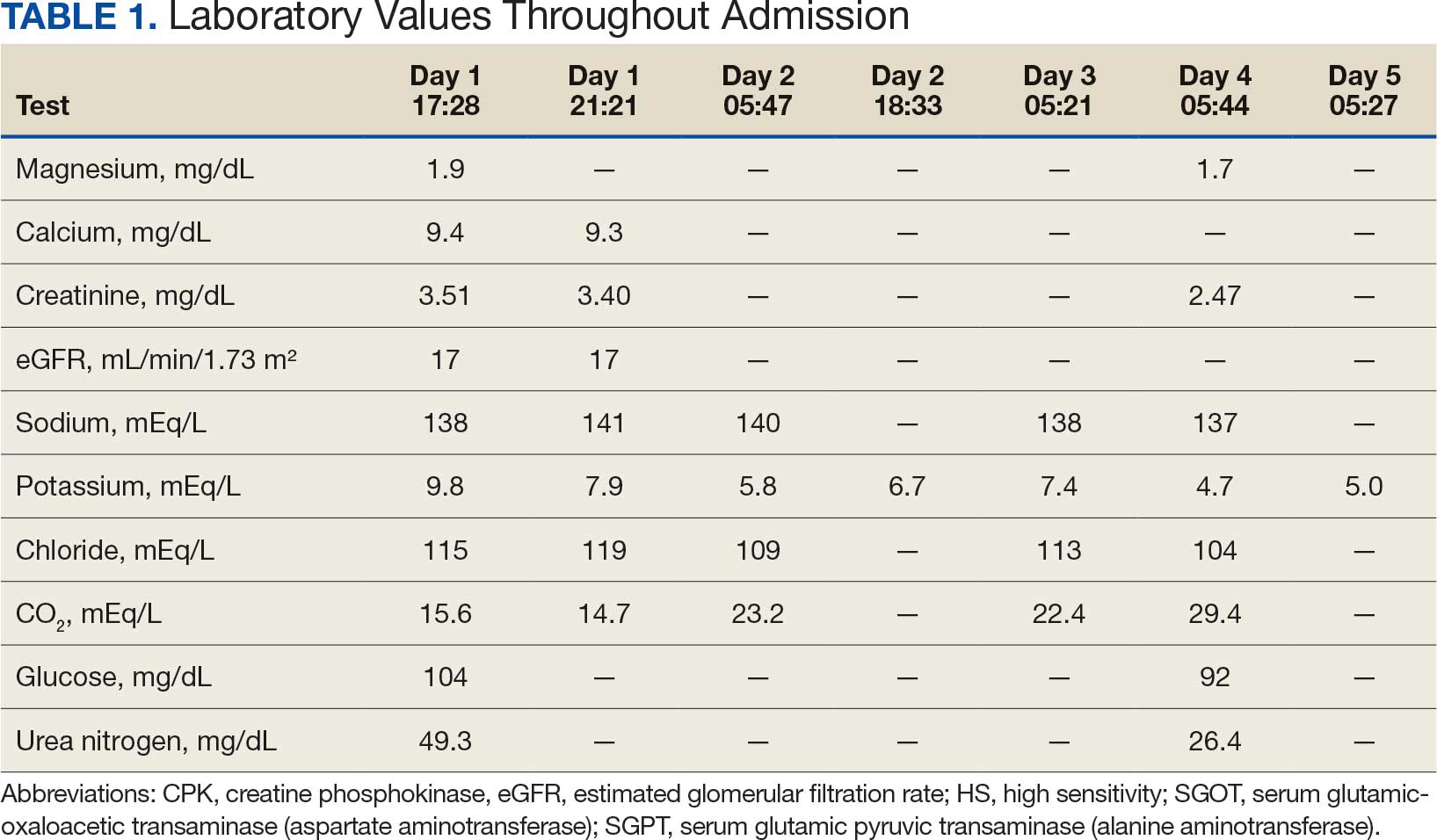

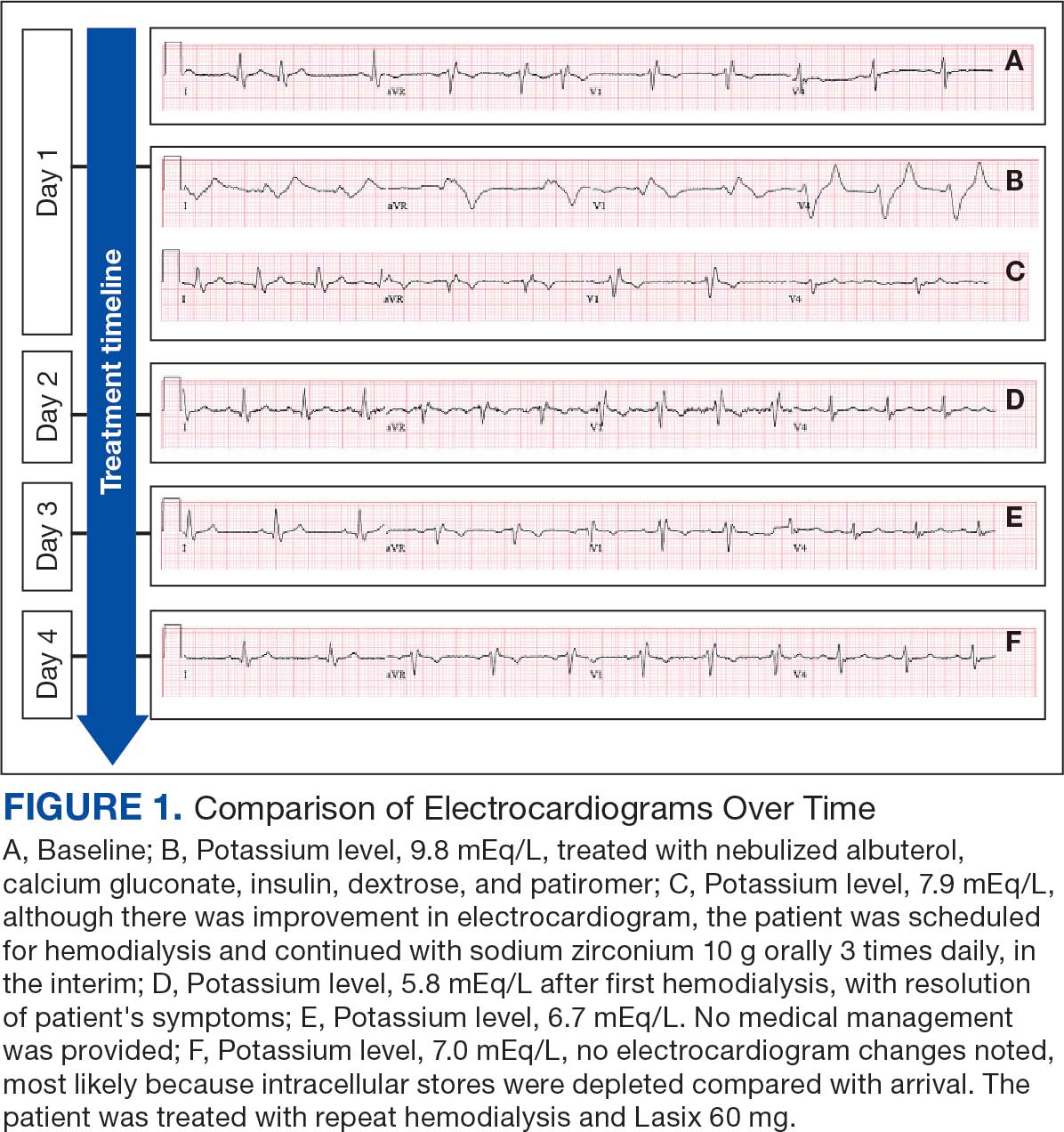

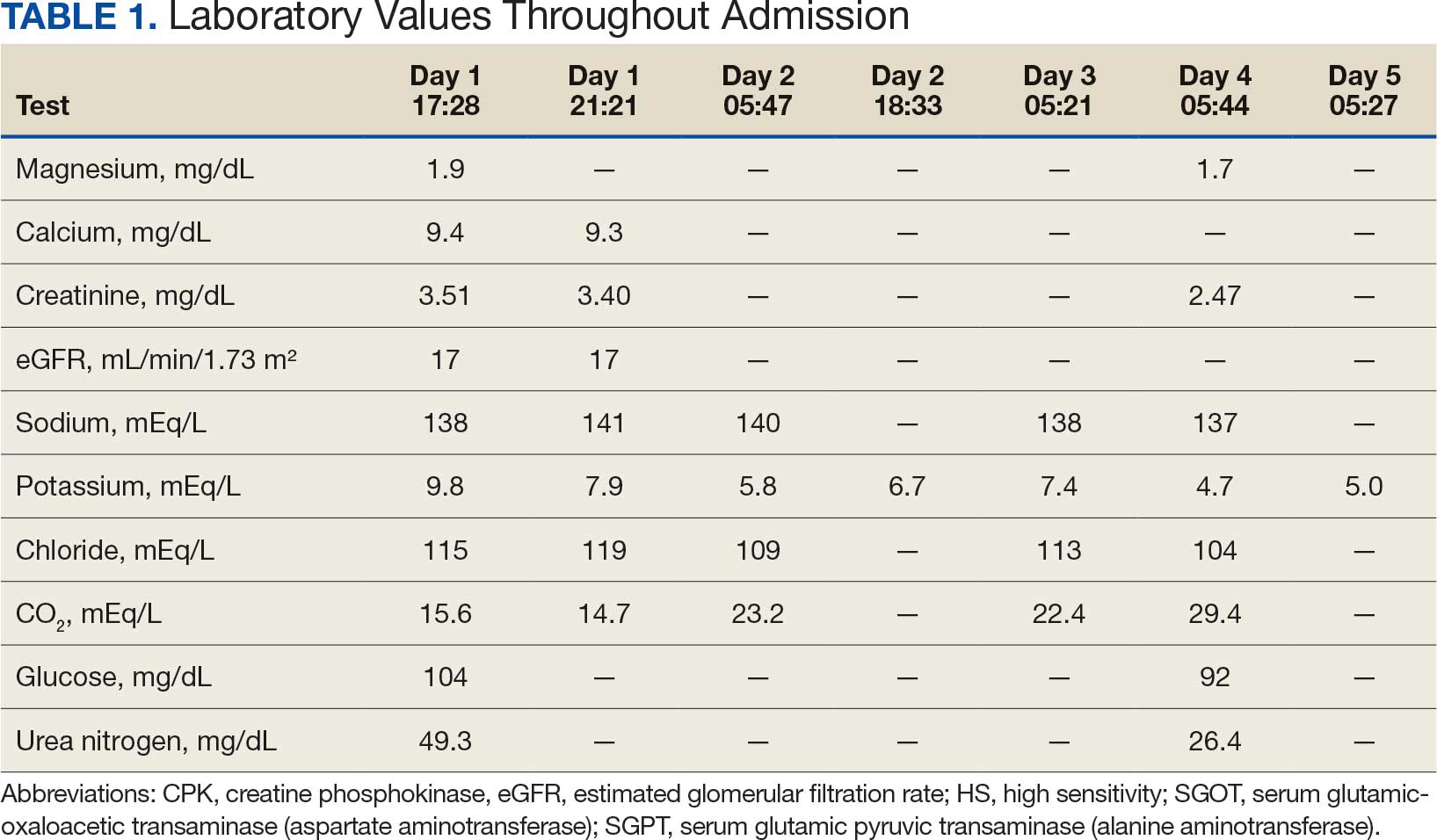

An 81-year-old Hispanic man with a history of hypertension, hypothyroidism, gout, and CKD stage 3B presented to the emergency department with progressive weakness resulting in falls and culminating in an inability to ambulate independently. Additional symptoms included nausea, diarrhea, and myalgia. His vital signs were notable for a pulse of 41 beats/min. The physical examination was remarkable for significant weakness of the bilateral upper extremities, inability to bear his own weight, and bilateral lower extremity edema. His initial ECG upon arrival showed bradycardia with wide QRS, absent P waves, and peaked T waves (Figure 1a). These findings differed from his baseline ECG taken 1 year earlier, which showed sinus rhythm with premature atrial complexes and an old right bundle branch block (Figure 1b).

Medication review revealed that the patient was currently prescribed 100 mg allopurinol daily, 2.5 mg amlodipine daily, 10 mg atorvastatin at bedtime, 4 mg doxazosin daily, 112 mcg levothyroxine daily, 100 mg losartan daily, 25 mg metoprolol daily, and 0.4 mg tamsulosin daily. The patient had also been taking over-the-counter indomethacin for knee pain.

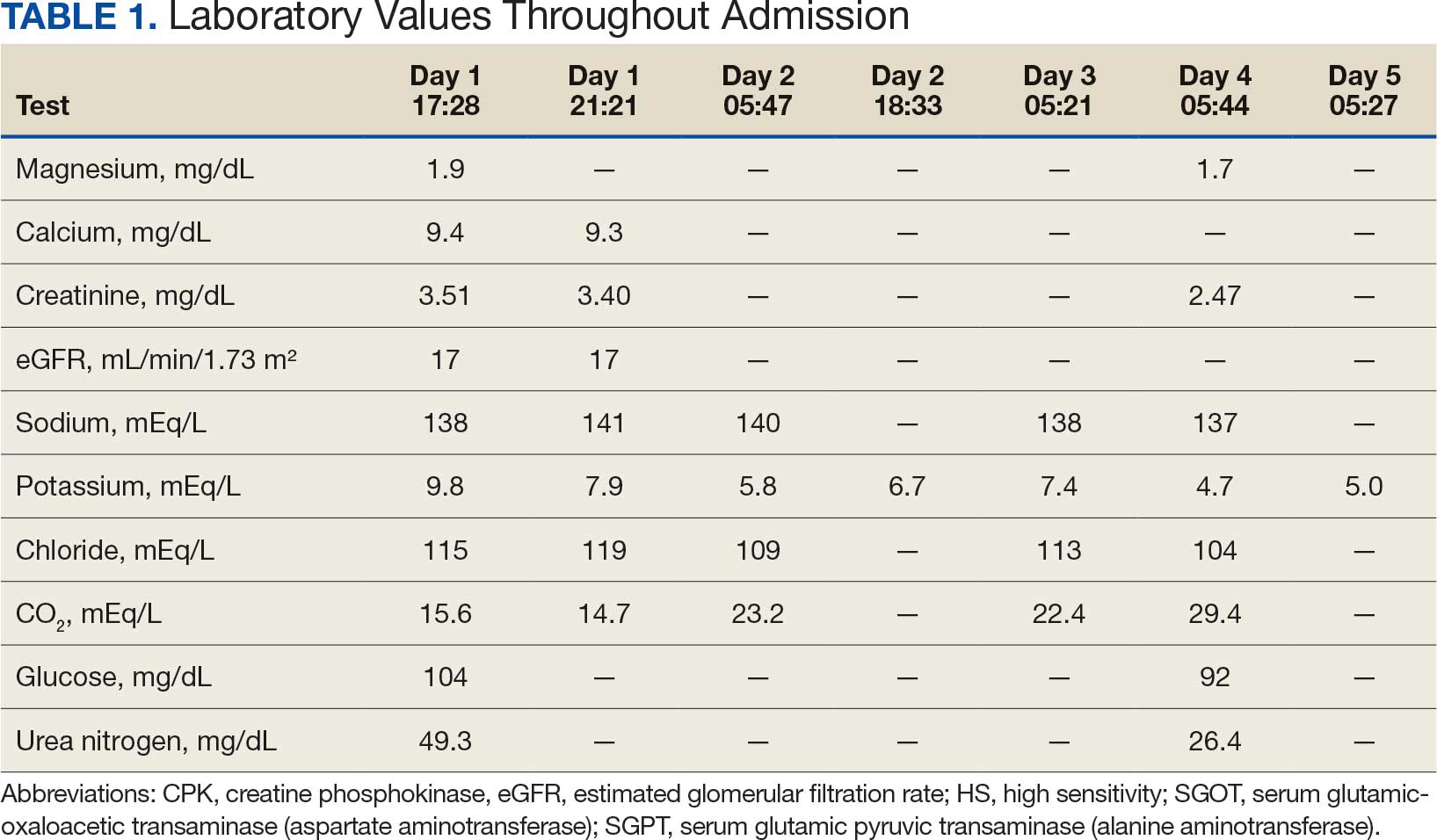

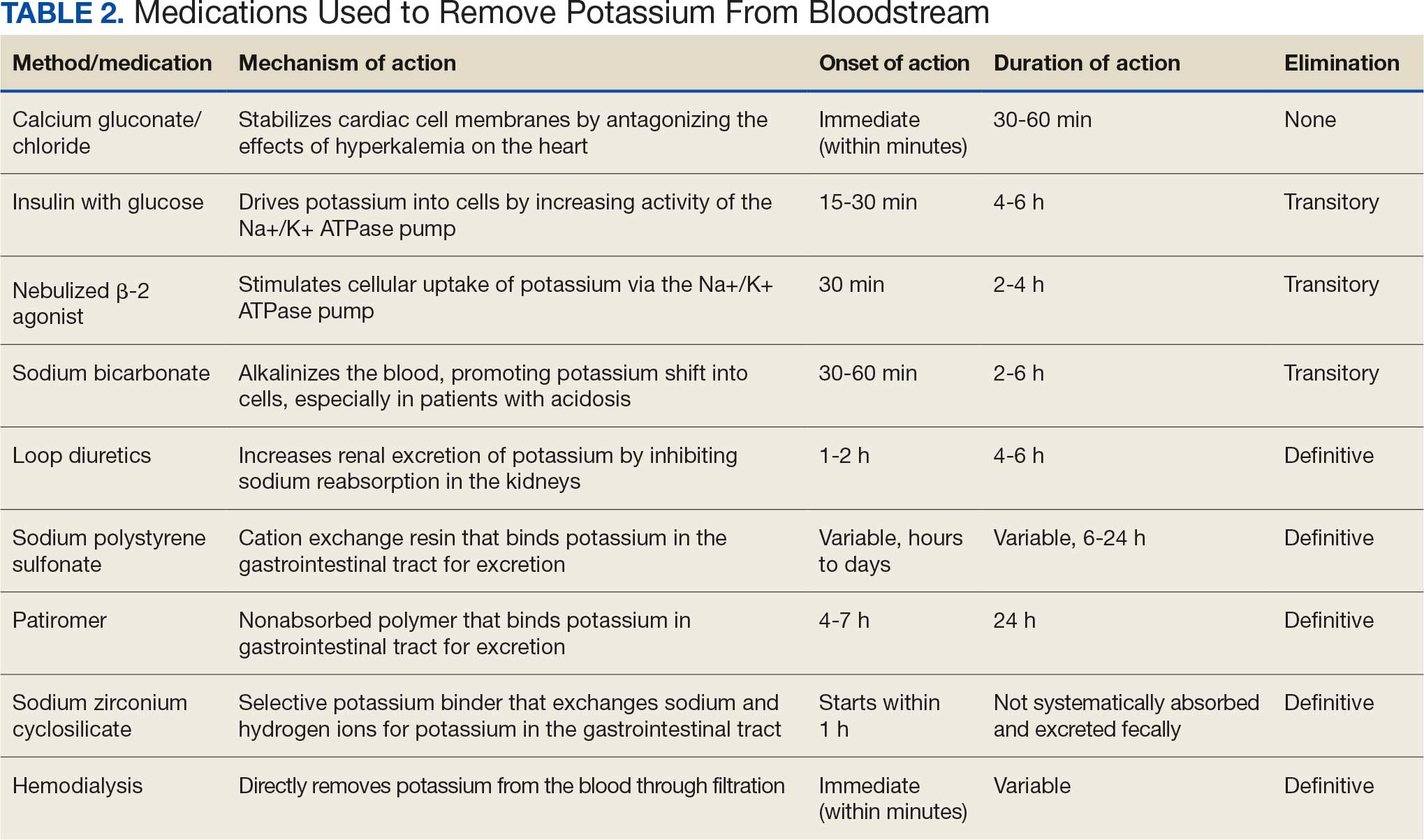

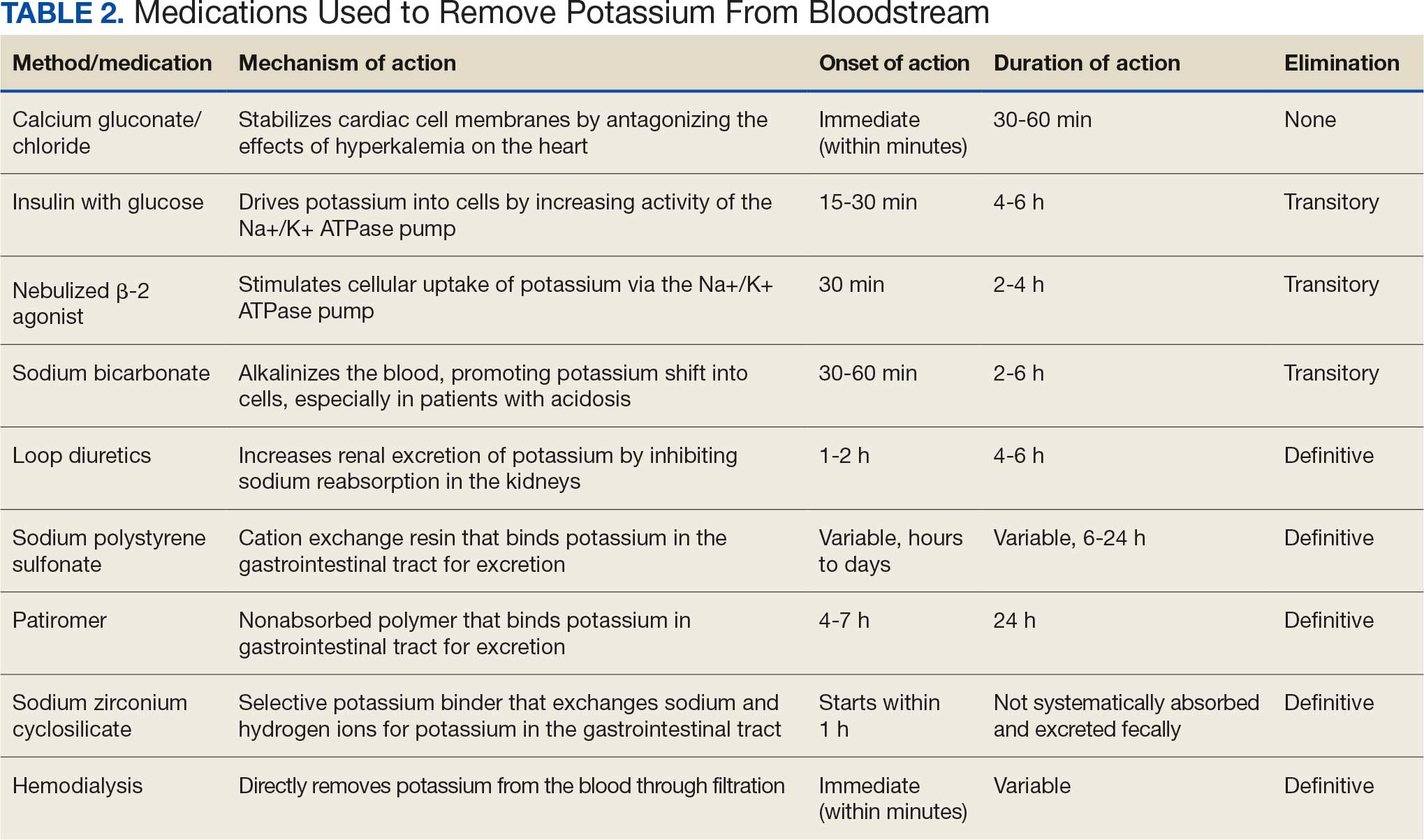

Based on the ECG results, he was treated with 0.083%/6 mL nebulized albuterol, 4.65 Mq/250 mL saline solution intravenous (IV) calcium gluconate, 10 units IV insulin with concomitant 50%/25 mL IV dextrose and 8.4 g of oral patiromer suspension. IV furosemide was held due to concern for renal function. The decision to proceed with hemodialysis was made. Repeat laboratory tests were performed, and an ECG obtained after treatment initiation but prior to hemodialysis demonstrated improvement of rate and T wave shortening (Figure 1c). The serum potassium level dropped from 9.8 mEq/L to 7.9 mEq/L (reference range, 3.5-5.0 mEq/L) (Table 1).

In addition to hemodialysis, sodium zirconium 10 g orally 3 times daily was added. Laboratory test results and an ECG was performed after dialysis continued to demonstrate improvement (Figure 1d). The patient’s potassium level decreased to 5.8 mEq/L, with the ECG demonstrating stability of heart rate and further improvement of the PR interval, QRS complex, and T waves.

Despite the established treatment regimen, potassium levels again rose to 6.7 mEq/L, but there were no significant changes in the ECG, and thus no medication changes were made (Figure 1e). Subsequent monitoring demonstrated a further increase in potassium to 7.4 mEq/L, with an ECG demonstrating a return to the baseline of 1 year prior. The patient underwent hemodialysis again and was given oral furosemide 60 mg every 12 hours. The potassium concentration after dialysis decreased to 4.7 mEq/L and remained stable, not going above 5.0 mEq/L on subsequent monitoring. The patient had resolution of all symptoms and was discharged.

Discussion

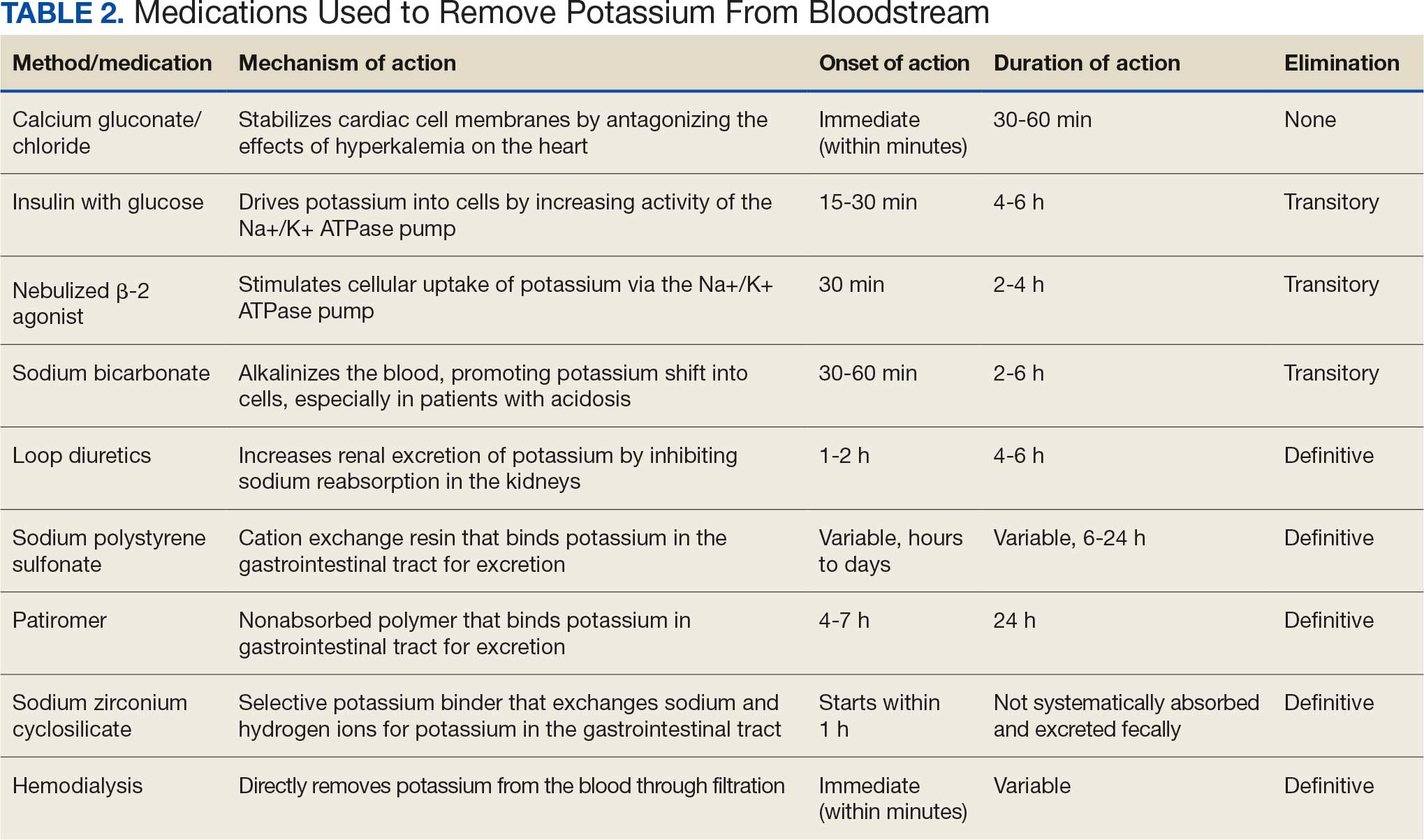

We have described in detail the presentation of each pathology and mechanisms of each treatment, starting with the patient’s initial condition that brought him to the emergency room—muscle weakness. Skeletal muscle weakness is a common manifestation of hyperkalemia, occurring in 20% to 40% of cases, and is more prevalent in severe elevations of potassium. Rarely, the weakness can progress to flaccid paralysis of the patient’s extremities and, in extreme cases, the diaphragm.

Muscle weakness progression occurs in a manner that resembles Guillain-Barré syndrome, starting in the lower extremities and ascending toward the upper extremities.10 This is known as secondary hyperkalemic periodic paralysis. Hyperkalemia lowers the transmembrane gradient in neurons, leading to neuronal depolarization independent of the degree of hyperkalemia. If the degree of hyperkalemia is large enough, this depolarization inactivates voltage-gated sodium channels, making neurons refractory to excitation. Electromyographical studies have shown reduction in the compounded muscle action potential.11 The transient nature of this paralysis is reflected by rapid correction of weakness and paralysis when the electrolyte disorder is corrected.

The patient in this case also presented with bradycardia. The ECG manifestations of hyperkalemia can include atrial asystole, intraventricular conduction disturbances, peaked T waves, and widened QRS complexes. However, some patients with renal insufficiency may not exhibit ECG changes despite significantly elevated serum potassium levels.12

The severity of hyperkalemia is crucial in determining the associated ECG changes, with levels > 6.0 mEq/L presenting with abnormalities.13 ECG findings alone may not always accurately reflect the severity of hyperkalemia, as up to 60% of patients with potassium levels > 6.0 mEq/L may not show ECG changes.14 Additionally, extreme hyperkalemia can lead to inconsistent ECG findings, making it challenging to rely solely on ECG for diagnosis and monitoring.8 The level of potassium that causes these effects varies widely through patient populations.

The main mechanism by which hyperkalemia affects the heart’s conduction system is through voltage differences across the conduction fibers and eventual steady-state inactivation of sodium channels. This combination of mechanisms shortens the action potential duration, allowing more cardiomyocytes to undergo synchronized depolarization. This amalgamation of cardiomyocytes repolarizing can be reflected on ECGs as peaked T waves. As the action potential decreases, there is a period during which cardiomyocytes are prone to tachyarrhythmias and ventricular fibrillation.

A reduced action potential may lead to increased rates of depolarization and thus conduction, which in some scenarios may increase heart rate. As the levels of potassium rise, intracellular accumulation impedes the entry of sodium by decreasing the cation gradient across the cell membrane. This effectively slows the sinus nodes and prolongs the QRS by slowing the overall propagation of action potentials. By this mechanism, conduction delays, blocks, or asystole are manifested. The patient in this case showed conduction delays, peaked T waves, and disappearance of P waves when he first arrived.

Hyperkalemia Treatment

Hyperkalemia develops most commonly due to acute or chronic kidney diseases, as was the case with this patient. The patient’s hyperkalemia was also augmented by the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which can directly affect renal function. A properly functioning kidney is responsible for excretion of up to 90% of ingested potassium, while the remainder is excreted through the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Definitive treatment of hyperkalemia is mitigated primarily through these 2 organ systems. The treatment also includes transitory mechanisms of potassium reduction. The goal of each method is to preserve the action potential of cardiomyocytes and myocytes. This patient presented with acute symptomatic hyperkalemia and received various medications to acutely, transitorily, and definitively treat it.

Initial therapy included calcium gluconate, which functions to stabilize the myocardial cell membrane. Hyperkalemia decreases the resting membrane action potential of excitable cells and predisposes them to early depolarization and thus dysrhythmias. Calcium decreases the threshold potential across cells and offsets the overall gradient back to near normal levels.15 Calcium can be delivered through calcium gluconate or calcium chloride. Calcium chloride is not preferred because extravasation can cause pain, blistering and tissue ischemia. Central venous access is required, potentially delaying prompt treatment. Calcium acts rapidly after administration—within 1 to 3 minutes—but only lasts 30 to 60 minutes.16 Administration of calcium gluconate can be repeated as often as necessary, but patients must be monitored for adverse effects of calcium such as nausea, abdominal pain, polydipsia, polyuria, muscle weakness, and paresthesia. Care must be taken when patients are taking digoxin, because calcium may potentiate toxicity.17 Although calcium provides immediate benefits it does little to correct the underlying cause; other medications are required to remove potassium from the body.

Two medication classes have been proven to shift potassium intracellularly. The first are β-2 agonists, such as albuterol/levalbuterol, and the second is insulin. Both work through sodium-potassium-ATPase in a direct manner. β-2 agonists stimulate sodium-potassium-ATPase to move more potassium intracellularly, but these effects have been seen only with high doses of albuterol, typically 4× the standard dose of 0.5 mg in nebulized solutions to achieve decreases in potassium of 0.3 to 0.6 mEq/L, although some trials have reported decreases of 0.62 to 0.98 mEq/L.15,18 These potassium-lowering effects of β-2 agonist are modest, but can be seen 20 to 30 minutes after administration and persist up to 1 to 2 hours. β-2 agonists are also readily affected by β blockers, which may reduce or negate the desired effect in hyperkalemia. For these reasons, a β-2 agonist should not be given as monotherapy and should be provided as an adjuvant to more independent therapies such as insulin. Insulin binds to receptors on muscle cells and increases the quantity of sodium-potassium-ATPase and glucose transporters. With this increase in influx pumps, surrounding tissues with higher resting membrane potentials can absorb the potassium load, thereby protecting cardiomyocytes.

Potassium Removal

Three methods are currently available to remove potassium from the body: GI excretion, renal excretion, and direct removal from the bloodstream. Under normal physiologic conditions, the kidneys account for about 90% of the body’s ability to remove potassium. Loop diuretics facilitate the removal of potassium by increasing urine production and have an additional potassium-wasting effect. Although the onset of action of loop diuretics is typically 30 to 60 minutes after oral administration, their effect can last for several hours. In this patient, furosemide was introduced later in the treatment plan to manage recurring hyperkalemia by enhancing renal potassium excretion.

Potassium binders such as patiromer act in the GI tract, effectively reducing serum potassium levels although with a slower onset of action than furosemide, generally taking hours to days to exert its effect. Both medications illustrate a tailored approach to managing potassium levels, adapted to the evolving needs and renal function of the patient. The last method is using hemodialysis—by far the most rapid method to remove potassium, but also the most invasive. The different methods of treating hyperkalemia are summarized in Table 2. This patient required multiple days of hemodialysis to completely correct the electrolyte disorder. Upon discharge, the patient continued oral furosemide 40 mg daily and eventually discontinued hemodialysis due to stable renal function.

Often, after correcting an inciting event, potassium stores in the body eventually stabilize and do not require additional follow-up. Patients prone to hyperkalemia should be thoroughly educated on medications to avoid (NSAIDs, ACEIs/ARBs, trimethoprim), an adequate low potassium diet, and symptoms that may warrant medical attention.19

Conclusions

This case illustrates the importance of recognizing the spectrum of manifestations of hyperkalemia, which ranged from muscle weakness to cardiac dysrhythmias. Management strategies for the patient included stabilization of cardiac membranes, potassium shifting, and potassium removal, each tailored to the patient’s individual clinical findings.

The case further illustrates the critical role of continuous monitoring and dynamic adjustment of therapeutic strategies in response to evolving clinical and laboratory findings. The initial and subsequent ECGs, alongside laboratory tests, were instrumental in guiding the adjustments needed in the treatment regimen, ensuring both the efficacy and safety of the interventions. This proactive approach can mitigate the risk of recurrent hyperkalemia and its complications.

- Youn JH, McDonough AA. Recent advances in understanding integrative control of potassium homeostasis. Annu Rev Physiol. 2009;71:381-401. doi:10.1146/annurev.physiol.010908.163241 2.

- Simon LV, Hashmi MF, Farrell MW. Hyperkalemia. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; September 4, 2023. Accessed October 22, 2025.

- Mu F, Betts KA, Woolley JM, et al. Prevalence and economic burden of hyperkalemia in the United States Medicare population. Curr Med Res Opin. 2020;36:1333-1341. doi:10.1080/03007995.2020.1775072

- Loutradis C, Tolika P, Skodra A, et al. Prevalence of hyperkalemia in diabetic and non-diabetic patients with chronic kidney disease: a nested case-control study. Am J Nephrol. 2015;42:351-360. doi:10.1159/000442393

- Grodzinsky A, Goyal A, Gosch K, et al. Prevalence and prognosis of hyperkalemia in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am J Med. 2016;129:858-865. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.03.008

- Hunter RW, Bailey MA. Hyperkalemia: pathophysiology, risk factors and consequences. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2019;34(suppl 3):iii2-iii11. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfz206

- Luo J, Brunelli SM, Jensen DE, Yang A. Association between serum potassium and outcomes in patients with reduced kidney function. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11:90-100. doi:10.2215/CJN.01730215

- Montford JR, Linas S. How dangerous is hyperkalemia? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:3155-3165. doi:10.1681/ASN.2016121344

- Mattu A, Brady WJ, Robinson DA. Electrocardiographic manifestations of hyperkalemia. Am J Emerg Med. 2000;18:721-729. doi:10.1053/ajem.2000.7344

- Kimmons LA, Usery JB. Acute ascending muscle weakness secondary to medication-induced hyperkalemia. Case Rep Med. 2014;2014:789529. doi:10.1155/2014/789529

- Naik KR, Saroja AO, Khanpet MS. Reversible electrophysiological abnormalities in acute secondary hyperkalemic paralysis. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2012;15:339-343. doi:10.4103/0972-2327.104354

- Montague BT, Ouellette JR, Buller GK. Retrospective review of the frequency of ECG changes in hyperkalemia. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:324-330. doi:10.2215/CJN.04611007

- Larivée NL, Michaud JB, More KM, Wilson JA, Tennankore KK. Hyperkalemia: prevalence, predictors and emerging treatments. Cardiol Ther. 2023;12:35-63. doi:10.1007/s40119-022-00289-z

- Shingarev R, Allon M. A physiologic-based approach to the treatment of acute hyperkalemia. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56:578-584. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.03.014

- Parham WA, Mehdirad AA, Biermann KM, Fredman CS. Hyperkalemia revisited. Tex Heart Inst J. 2006;33:40-47.

- Ng KE, Lee CS. Updated treatment options in the management of hyperkalemia. U.S. Pharmacist. February 16, 2017. Accessed October 1, 2025. www.uspharmacist.com/article/updated-treatment-options-in-the-management-of-hyperkalemia

- Quick G, Bastani B. Prolonged asystolic hyperkalemic cardiac arrest with no neurologic sequelae. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;24:305-311. doi:10.1016/s0196-0644(94)70144-x 18.

- Allon M, Dunlay R, Copkney C. Nebulized albuterol for acute hyperkalemia in patients on hemodialysis. Ann Intern Med. 1989;110:426-429. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-110-6-42619.

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 2024;105(4 suppl):S117-S314. doi:10.1016/j.kint.2023.10.018

Hyperkalemia involves elevated serum potassium levels (> 5.0 mEq/L) and represents an important electrolyte disturbance due to its potentially severe consequences, including cardiac effects that can lead to dysrhythmia and even asystole and death.1,2 In a US Medicare population, the prevalence of hyperkalemia has been estimated at 2.7% and is associated with substantial health care costs.3 The prevalence is even more marked in patients with preexisting conditions such as chronic kidney disease (CKD) and heart failure.4,5

Hyperkalemia can result from multiple factors, including impaired renal function, adrenal disease, adverse drug reactions of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) and other medications, and heritable mutations.6 Hyperkalemia poses a considerable clinical risk, associated with adverse outcomes such as myocardial infarction and increased mortality in patients with CKD.5,7,8 Electrocardiographic (ECG) changes associated with hyperkalemia play a vital role in guiding clinical decisions and treatment strategies.9 Understanding the pathophysiology, risk factors, and consequences of hyperkalemia, as well as the significance of ECG changes in its management, is essential for health care practitioners.

Case Presentation

An 81-year-old Hispanic man with a history of hypertension, hypothyroidism, gout, and CKD stage 3B presented to the emergency department with progressive weakness resulting in falls and culminating in an inability to ambulate independently. Additional symptoms included nausea, diarrhea, and myalgia. His vital signs were notable for a pulse of 41 beats/min. The physical examination was remarkable for significant weakness of the bilateral upper extremities, inability to bear his own weight, and bilateral lower extremity edema. His initial ECG upon arrival showed bradycardia with wide QRS, absent P waves, and peaked T waves (Figure 1a). These findings differed from his baseline ECG taken 1 year earlier, which showed sinus rhythm with premature atrial complexes and an old right bundle branch block (Figure 1b).

Medication review revealed that the patient was currently prescribed 100 mg allopurinol daily, 2.5 mg amlodipine daily, 10 mg atorvastatin at bedtime, 4 mg doxazosin daily, 112 mcg levothyroxine daily, 100 mg losartan daily, 25 mg metoprolol daily, and 0.4 mg tamsulosin daily. The patient had also been taking over-the-counter indomethacin for knee pain.

Based on the ECG results, he was treated with 0.083%/6 mL nebulized albuterol, 4.65 Mq/250 mL saline solution intravenous (IV) calcium gluconate, 10 units IV insulin with concomitant 50%/25 mL IV dextrose and 8.4 g of oral patiromer suspension. IV furosemide was held due to concern for renal function. The decision to proceed with hemodialysis was made. Repeat laboratory tests were performed, and an ECG obtained after treatment initiation but prior to hemodialysis demonstrated improvement of rate and T wave shortening (Figure 1c). The serum potassium level dropped from 9.8 mEq/L to 7.9 mEq/L (reference range, 3.5-5.0 mEq/L) (Table 1).

In addition to hemodialysis, sodium zirconium 10 g orally 3 times daily was added. Laboratory test results and an ECG was performed after dialysis continued to demonstrate improvement (Figure 1d). The patient’s potassium level decreased to 5.8 mEq/L, with the ECG demonstrating stability of heart rate and further improvement of the PR interval, QRS complex, and T waves.