User login

No evidence to guide selection of biologic for severe asthma

Although “biologics have been really revolutionary for the treatment of severe uncontrolled asthma, we still don’t have evidence to know the right drug for the right patient,” said Wendy Moore, MD, of Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C.

“You start with your best guess and then switch,” she said in an interview.

There are no real-world contemporary measurements of biologic therapy in the United States at this time, Dr. Moore explained during her presentation of findings from the CHRONICLE trial at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST 2020), held virtually this year.

The agents have different targets: omalizumab targets immunoglobulin E, mepolizumab and reslizumab target interleukin (IL)-5, benralizumab targets the IL-5 receptor, and dupilumab targets the common receptor IL-4 receptor A for IL-4 and IL-13.

When the starting biologic doesn’t get the desired results, there is no evidence to show whether another will work better. What we say is, “This one is not working as well as I’d like, let’s try something new?” said Dr. Moore.

However, when looking at data on patients with severe asthma who change from one biologic to another, “I was actually pleased to see that only 10% are switching,” she said in an interview.

But, she added, “if you add that up with the 8% who are stopping, that means that almost 20% don’t get the clinical response they want.”

CHRONICLE trial

In the ongoing observational CHRONICLE trial, Dr. Moore and colleagues assessed biologic initiations, discontinuations, and switches to a different agent.

All 1,884 study participants had a diagnosis of severe asthma and were being treated by an allergist/immunologist or a pulmonologist. All were taking high-dose inhaled corticosteroids and additional controllers, or had received an Food and Drug Administration–approved monoclonal antibody, systemic corticosteroid, or another systemic immunosuppressant for at least half of the previous 12 months.

In the study cohort, 1,219 participants were receiving one biologic and 27 were receiving two.

Before November 2018, “it was almost universally all benralizumab being prescribed.” An earlier preference was omalizumab, which was prescribed to 99% of patients before November 2015 and to 45% from November 2017 to November 2018.

“As new drugs were introduced, patients were switched if the desired outcome was not achieved,” Dr. Moore explained.

Over the 2-year period from February 2018 to February 2020, 134 patients – about 10% of all participants taking a biologic – made 148 switches to another biologic.

“The most common reasons reported for switching were lack of efficacy, worsening of asthma control, or waning efficacy,” Dr. Moore reported.

Of the 101 patients (8%) who discontinued 106 biologics, reasons cited were a worsening of asthma symptoms, a desire to change to a cheaper medication, and a waning of effectiveness.

“It seems that the biologic used depended on when you started and whether you were prescribed by an immunologist or pulmonologist,” said Dr. Moore. “I don’t think we understand the perfect patient for any one of these drugs.”

Large-population studies need to be done on each of the drugs. “You have to look at who’s the super responder, the partial responder, compared with the nonresponders, for each medication, but those comparative studies are unlikely to happen,” she said.

In her own practice, her 175 patients are “pretty evenly split between dupilumab, benralizumab, and mepolizumab.”

I have opinions on what works, said Dr. Moore, but none of it is evidence-based. “Those with upper airway involvement with chronic sinusitis tend to do better with mepolizumab than benralizumab. My opinion,” she emphasized.

“People with nasal problems may do better with dupilumab and mepolizumab,” she added. “Also in my opinion.

“But more likely, the issue is you have a partial responder who’s on a T2 high drug but has a T2 low problem too.”

PATHWAY study

Findings from the phase 2B PATHWAY study showed that tezepelumab reduced exacerbations in patients with uncontrolled asthma better than inhaled corticosteroids, and improved forced expiratory volume in 1 second.

“Adherence was monitored very carefully,” said investigator Jonathan Corren, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, who presented the PATHWAY data. This could explain, in part, why some patients in the control group “showed improvement from baseline.”

Before switching to a biologic, “we should always consider some of these issues that might contribute to better asthma control, like patient adherence or the inability to use an inhaler properly,” Dr. Corren said.

Some people have never been “shown how to use their inhalers properly,” said Moore. “Some of them come back fine when we show them.”

Dr. Moore has been on the advisory board for AstraZeneca, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), Regeneron, and Sanofi. Dr. Corren reports receiving honoraria from AstraZeneca.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Although “biologics have been really revolutionary for the treatment of severe uncontrolled asthma, we still don’t have evidence to know the right drug for the right patient,” said Wendy Moore, MD, of Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C.

“You start with your best guess and then switch,” she said in an interview.

There are no real-world contemporary measurements of biologic therapy in the United States at this time, Dr. Moore explained during her presentation of findings from the CHRONICLE trial at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST 2020), held virtually this year.

The agents have different targets: omalizumab targets immunoglobulin E, mepolizumab and reslizumab target interleukin (IL)-5, benralizumab targets the IL-5 receptor, and dupilumab targets the common receptor IL-4 receptor A for IL-4 and IL-13.

When the starting biologic doesn’t get the desired results, there is no evidence to show whether another will work better. What we say is, “This one is not working as well as I’d like, let’s try something new?” said Dr. Moore.

However, when looking at data on patients with severe asthma who change from one biologic to another, “I was actually pleased to see that only 10% are switching,” she said in an interview.

But, she added, “if you add that up with the 8% who are stopping, that means that almost 20% don’t get the clinical response they want.”

CHRONICLE trial

In the ongoing observational CHRONICLE trial, Dr. Moore and colleagues assessed biologic initiations, discontinuations, and switches to a different agent.

All 1,884 study participants had a diagnosis of severe asthma and were being treated by an allergist/immunologist or a pulmonologist. All were taking high-dose inhaled corticosteroids and additional controllers, or had received an Food and Drug Administration–approved monoclonal antibody, systemic corticosteroid, or another systemic immunosuppressant for at least half of the previous 12 months.

In the study cohort, 1,219 participants were receiving one biologic and 27 were receiving two.

Before November 2018, “it was almost universally all benralizumab being prescribed.” An earlier preference was omalizumab, which was prescribed to 99% of patients before November 2015 and to 45% from November 2017 to November 2018.

“As new drugs were introduced, patients were switched if the desired outcome was not achieved,” Dr. Moore explained.

Over the 2-year period from February 2018 to February 2020, 134 patients – about 10% of all participants taking a biologic – made 148 switches to another biologic.

“The most common reasons reported for switching were lack of efficacy, worsening of asthma control, or waning efficacy,” Dr. Moore reported.

Of the 101 patients (8%) who discontinued 106 biologics, reasons cited were a worsening of asthma symptoms, a desire to change to a cheaper medication, and a waning of effectiveness.

“It seems that the biologic used depended on when you started and whether you were prescribed by an immunologist or pulmonologist,” said Dr. Moore. “I don’t think we understand the perfect patient for any one of these drugs.”

Large-population studies need to be done on each of the drugs. “You have to look at who’s the super responder, the partial responder, compared with the nonresponders, for each medication, but those comparative studies are unlikely to happen,” she said.

In her own practice, her 175 patients are “pretty evenly split between dupilumab, benralizumab, and mepolizumab.”

I have opinions on what works, said Dr. Moore, but none of it is evidence-based. “Those with upper airway involvement with chronic sinusitis tend to do better with mepolizumab than benralizumab. My opinion,” she emphasized.

“People with nasal problems may do better with dupilumab and mepolizumab,” she added. “Also in my opinion.

“But more likely, the issue is you have a partial responder who’s on a T2 high drug but has a T2 low problem too.”

PATHWAY study

Findings from the phase 2B PATHWAY study showed that tezepelumab reduced exacerbations in patients with uncontrolled asthma better than inhaled corticosteroids, and improved forced expiratory volume in 1 second.

“Adherence was monitored very carefully,” said investigator Jonathan Corren, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, who presented the PATHWAY data. This could explain, in part, why some patients in the control group “showed improvement from baseline.”

Before switching to a biologic, “we should always consider some of these issues that might contribute to better asthma control, like patient adherence or the inability to use an inhaler properly,” Dr. Corren said.

Some people have never been “shown how to use their inhalers properly,” said Moore. “Some of them come back fine when we show them.”

Dr. Moore has been on the advisory board for AstraZeneca, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), Regeneron, and Sanofi. Dr. Corren reports receiving honoraria from AstraZeneca.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Although “biologics have been really revolutionary for the treatment of severe uncontrolled asthma, we still don’t have evidence to know the right drug for the right patient,” said Wendy Moore, MD, of Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C.

“You start with your best guess and then switch,” she said in an interview.

There are no real-world contemporary measurements of biologic therapy in the United States at this time, Dr. Moore explained during her presentation of findings from the CHRONICLE trial at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST 2020), held virtually this year.

The agents have different targets: omalizumab targets immunoglobulin E, mepolizumab and reslizumab target interleukin (IL)-5, benralizumab targets the IL-5 receptor, and dupilumab targets the common receptor IL-4 receptor A for IL-4 and IL-13.

When the starting biologic doesn’t get the desired results, there is no evidence to show whether another will work better. What we say is, “This one is not working as well as I’d like, let’s try something new?” said Dr. Moore.

However, when looking at data on patients with severe asthma who change from one biologic to another, “I was actually pleased to see that only 10% are switching,” she said in an interview.

But, she added, “if you add that up with the 8% who are stopping, that means that almost 20% don’t get the clinical response they want.”

CHRONICLE trial

In the ongoing observational CHRONICLE trial, Dr. Moore and colleagues assessed biologic initiations, discontinuations, and switches to a different agent.

All 1,884 study participants had a diagnosis of severe asthma and were being treated by an allergist/immunologist or a pulmonologist. All were taking high-dose inhaled corticosteroids and additional controllers, or had received an Food and Drug Administration–approved monoclonal antibody, systemic corticosteroid, or another systemic immunosuppressant for at least half of the previous 12 months.

In the study cohort, 1,219 participants were receiving one biologic and 27 were receiving two.

Before November 2018, “it was almost universally all benralizumab being prescribed.” An earlier preference was omalizumab, which was prescribed to 99% of patients before November 2015 and to 45% from November 2017 to November 2018.

“As new drugs were introduced, patients were switched if the desired outcome was not achieved,” Dr. Moore explained.

Over the 2-year period from February 2018 to February 2020, 134 patients – about 10% of all participants taking a biologic – made 148 switches to another biologic.

“The most common reasons reported for switching were lack of efficacy, worsening of asthma control, or waning efficacy,” Dr. Moore reported.

Of the 101 patients (8%) who discontinued 106 biologics, reasons cited were a worsening of asthma symptoms, a desire to change to a cheaper medication, and a waning of effectiveness.

“It seems that the biologic used depended on when you started and whether you were prescribed by an immunologist or pulmonologist,” said Dr. Moore. “I don’t think we understand the perfect patient for any one of these drugs.”

Large-population studies need to be done on each of the drugs. “You have to look at who’s the super responder, the partial responder, compared with the nonresponders, for each medication, but those comparative studies are unlikely to happen,” she said.

In her own practice, her 175 patients are “pretty evenly split between dupilumab, benralizumab, and mepolizumab.”

I have opinions on what works, said Dr. Moore, but none of it is evidence-based. “Those with upper airway involvement with chronic sinusitis tend to do better with mepolizumab than benralizumab. My opinion,” she emphasized.

“People with nasal problems may do better with dupilumab and mepolizumab,” she added. “Also in my opinion.

“But more likely, the issue is you have a partial responder who’s on a T2 high drug but has a T2 low problem too.”

PATHWAY study

Findings from the phase 2B PATHWAY study showed that tezepelumab reduced exacerbations in patients with uncontrolled asthma better than inhaled corticosteroids, and improved forced expiratory volume in 1 second.

“Adherence was monitored very carefully,” said investigator Jonathan Corren, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, who presented the PATHWAY data. This could explain, in part, why some patients in the control group “showed improvement from baseline.”

Before switching to a biologic, “we should always consider some of these issues that might contribute to better asthma control, like patient adherence or the inability to use an inhaler properly,” Dr. Corren said.

Some people have never been “shown how to use their inhalers properly,” said Moore. “Some of them come back fine when we show them.”

Dr. Moore has been on the advisory board for AstraZeneca, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), Regeneron, and Sanofi. Dr. Corren reports receiving honoraria from AstraZeneca.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

OSA diagnoses not carried forward to the inpatient setting

Obstructive sleep apnea diagnoses may not be carried over to the inpatient setting, with potentially negative consequences for clinical outcomes, quality of life, and health care costs, an investigator said at the virtual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

In a retrospective, single-center study, nearly 40% of patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) diagnosed in the outpatient setting did not have a corresponding diagnosis during hospitalization, according to researcher Nitasa Sahu, MD.*

The missed OSA diagnoses could have especially negative implications for patients who don’t continue on positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy during the hospital stay, said Dr. Sahu, a fellow in pulmonary/critical care at St. Luke’s University Health Network in Bethlehem, Pa.

The finding indicates a large-magnitude opportunity to improve health care through better communication and optimized care, according to the researcher.

“Obstructive sleep apnea is underrecognized, it’s underdiagnosed, and it has a lot of implications for a patient’s hospitalization,” she said in interview

Clinical pathways should be set up to ensure that patients with OSA are properly identified and use their prescribed treatment, according to Dr. Sahu.

“I think that should, and would, reduce overall health care costs, with better outcomes as well,” she said.

Pulmonologist Saadia A. Faiz, MD, FCCP, said she hoped this study, presented at a late-breaking abstract at the virtual meeting, would highlight the importance of OSA screening and call attention to barriers to screening that may be in place in the inpatient setting.

That’s especially important because, after admission, the focus is often on the cause of admission rather than underlying comorbidities such as OSA, said Dr. Faiz, professor in the department of pulmonary medicine at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

“Working in a cancer hospital, the focus is always on the cancer, so sometimes even the patient will dismiss issues with their sleep,” Dr. Faiz said of her own experience in an interview.

“Often with sleep apnea, for people in the general population, the reason they seek medical attention is because their spouse notices that they’re snoring, so it is something that is not as emphasized,” added Dr. Faiz, who was not involved in the study.

In their study, Dr. Sahu and coauthors reviewed electronic health record data for adults hospitalized on the general internal medicine service at Penn State Hershey Medical Center from January 2017 through 2018. They restricted their search to first admissions.

The researchers looked for ICD-9 codes indicating an OSA diagnosis during their inpatient admission. They looked for the same codes in the preceding 5 years to see if the patients had a prior outpatient OSA diagnosis.

The inpatient cohort included 13,067 patients, of whom 53% were male, 87% were White, and 77% were over 50 years of age. Comorbidities included hypertension in 42%, atrial fibrillation in 21%, type 2 diabetes mellitus in 14%, congestive heart failure in 15%, and prior stroke in 0.5%.

A total of 991 individuals in the inpatient cohort had a prior outpatient OSA diagnosis. Of that group, 376 patients (38%) did not have an inpatient OSA diagnosis on inpatient record, according to the reported study data.

That large proportion of discordant diagnoses suggests a lot of missed opportunities to provide OSA therapy in the inpatient setting and to reinforce chronic disease state management, according to Dr. Sahu and colleagues.

How those discordant OSA diagnoses impact length of stay, cost of care, and readmissions are unanswered questions that deserve further study, Dr. Sahu said.

Among patients who did not have outpatient OSA diagnoses, another 804 patients, or about 6%, ended up with an inpatient diagnosis during their hospitalization, the researchers also reported.

While a number of those inpatient OSA diagnoses could have been coded in error, it’s also possible that they were indeed cases of OSA that went unrecognized until the individuals were hospitalized, Dr. Sahu said.

Dr. Sahu had no relevant relationships to report related to the study. One of four study coauthors reported relationships with Boehringer-Ingelheim, Nitto Denko, and Galapagos.

SOURCE: Sahu N. CHEST 2020. Abstract.

*Correction, 11/3/20: An earlier version of this article misstated the name of Nitasa Sahu, MD.

Obstructive sleep apnea diagnoses may not be carried over to the inpatient setting, with potentially negative consequences for clinical outcomes, quality of life, and health care costs, an investigator said at the virtual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

In a retrospective, single-center study, nearly 40% of patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) diagnosed in the outpatient setting did not have a corresponding diagnosis during hospitalization, according to researcher Nitasa Sahu, MD.*

The missed OSA diagnoses could have especially negative implications for patients who don’t continue on positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy during the hospital stay, said Dr. Sahu, a fellow in pulmonary/critical care at St. Luke’s University Health Network in Bethlehem, Pa.

The finding indicates a large-magnitude opportunity to improve health care through better communication and optimized care, according to the researcher.

“Obstructive sleep apnea is underrecognized, it’s underdiagnosed, and it has a lot of implications for a patient’s hospitalization,” she said in interview

Clinical pathways should be set up to ensure that patients with OSA are properly identified and use their prescribed treatment, according to Dr. Sahu.

“I think that should, and would, reduce overall health care costs, with better outcomes as well,” she said.

Pulmonologist Saadia A. Faiz, MD, FCCP, said she hoped this study, presented at a late-breaking abstract at the virtual meeting, would highlight the importance of OSA screening and call attention to barriers to screening that may be in place in the inpatient setting.

That’s especially important because, after admission, the focus is often on the cause of admission rather than underlying comorbidities such as OSA, said Dr. Faiz, professor in the department of pulmonary medicine at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

“Working in a cancer hospital, the focus is always on the cancer, so sometimes even the patient will dismiss issues with their sleep,” Dr. Faiz said of her own experience in an interview.

“Often with sleep apnea, for people in the general population, the reason they seek medical attention is because their spouse notices that they’re snoring, so it is something that is not as emphasized,” added Dr. Faiz, who was not involved in the study.

In their study, Dr. Sahu and coauthors reviewed electronic health record data for adults hospitalized on the general internal medicine service at Penn State Hershey Medical Center from January 2017 through 2018. They restricted their search to first admissions.

The researchers looked for ICD-9 codes indicating an OSA diagnosis during their inpatient admission. They looked for the same codes in the preceding 5 years to see if the patients had a prior outpatient OSA diagnosis.

The inpatient cohort included 13,067 patients, of whom 53% were male, 87% were White, and 77% were over 50 years of age. Comorbidities included hypertension in 42%, atrial fibrillation in 21%, type 2 diabetes mellitus in 14%, congestive heart failure in 15%, and prior stroke in 0.5%.

A total of 991 individuals in the inpatient cohort had a prior outpatient OSA diagnosis. Of that group, 376 patients (38%) did not have an inpatient OSA diagnosis on inpatient record, according to the reported study data.

That large proportion of discordant diagnoses suggests a lot of missed opportunities to provide OSA therapy in the inpatient setting and to reinforce chronic disease state management, according to Dr. Sahu and colleagues.

How those discordant OSA diagnoses impact length of stay, cost of care, and readmissions are unanswered questions that deserve further study, Dr. Sahu said.

Among patients who did not have outpatient OSA diagnoses, another 804 patients, or about 6%, ended up with an inpatient diagnosis during their hospitalization, the researchers also reported.

While a number of those inpatient OSA diagnoses could have been coded in error, it’s also possible that they were indeed cases of OSA that went unrecognized until the individuals were hospitalized, Dr. Sahu said.

Dr. Sahu had no relevant relationships to report related to the study. One of four study coauthors reported relationships with Boehringer-Ingelheim, Nitto Denko, and Galapagos.

SOURCE: Sahu N. CHEST 2020. Abstract.

*Correction, 11/3/20: An earlier version of this article misstated the name of Nitasa Sahu, MD.

Obstructive sleep apnea diagnoses may not be carried over to the inpatient setting, with potentially negative consequences for clinical outcomes, quality of life, and health care costs, an investigator said at the virtual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

In a retrospective, single-center study, nearly 40% of patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) diagnosed in the outpatient setting did not have a corresponding diagnosis during hospitalization, according to researcher Nitasa Sahu, MD.*

The missed OSA diagnoses could have especially negative implications for patients who don’t continue on positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy during the hospital stay, said Dr. Sahu, a fellow in pulmonary/critical care at St. Luke’s University Health Network in Bethlehem, Pa.

The finding indicates a large-magnitude opportunity to improve health care through better communication and optimized care, according to the researcher.

“Obstructive sleep apnea is underrecognized, it’s underdiagnosed, and it has a lot of implications for a patient’s hospitalization,” she said in interview

Clinical pathways should be set up to ensure that patients with OSA are properly identified and use their prescribed treatment, according to Dr. Sahu.

“I think that should, and would, reduce overall health care costs, with better outcomes as well,” she said.

Pulmonologist Saadia A. Faiz, MD, FCCP, said she hoped this study, presented at a late-breaking abstract at the virtual meeting, would highlight the importance of OSA screening and call attention to barriers to screening that may be in place in the inpatient setting.

That’s especially important because, after admission, the focus is often on the cause of admission rather than underlying comorbidities such as OSA, said Dr. Faiz, professor in the department of pulmonary medicine at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

“Working in a cancer hospital, the focus is always on the cancer, so sometimes even the patient will dismiss issues with their sleep,” Dr. Faiz said of her own experience in an interview.

“Often with sleep apnea, for people in the general population, the reason they seek medical attention is because their spouse notices that they’re snoring, so it is something that is not as emphasized,” added Dr. Faiz, who was not involved in the study.

In their study, Dr. Sahu and coauthors reviewed electronic health record data for adults hospitalized on the general internal medicine service at Penn State Hershey Medical Center from January 2017 through 2018. They restricted their search to first admissions.

The researchers looked for ICD-9 codes indicating an OSA diagnosis during their inpatient admission. They looked for the same codes in the preceding 5 years to see if the patients had a prior outpatient OSA diagnosis.

The inpatient cohort included 13,067 patients, of whom 53% were male, 87% were White, and 77% were over 50 years of age. Comorbidities included hypertension in 42%, atrial fibrillation in 21%, type 2 diabetes mellitus in 14%, congestive heart failure in 15%, and prior stroke in 0.5%.

A total of 991 individuals in the inpatient cohort had a prior outpatient OSA diagnosis. Of that group, 376 patients (38%) did not have an inpatient OSA diagnosis on inpatient record, according to the reported study data.

That large proportion of discordant diagnoses suggests a lot of missed opportunities to provide OSA therapy in the inpatient setting and to reinforce chronic disease state management, according to Dr. Sahu and colleagues.

How those discordant OSA diagnoses impact length of stay, cost of care, and readmissions are unanswered questions that deserve further study, Dr. Sahu said.

Among patients who did not have outpatient OSA diagnoses, another 804 patients, or about 6%, ended up with an inpatient diagnosis during their hospitalization, the researchers also reported.

While a number of those inpatient OSA diagnoses could have been coded in error, it’s also possible that they were indeed cases of OSA that went unrecognized until the individuals were hospitalized, Dr. Sahu said.

Dr. Sahu had no relevant relationships to report related to the study. One of four study coauthors reported relationships with Boehringer-Ingelheim, Nitto Denko, and Galapagos.

SOURCE: Sahu N. CHEST 2020. Abstract.

*Correction, 11/3/20: An earlier version of this article misstated the name of Nitasa Sahu, MD.

FROM CHEST 2020

Unneeded meds at discharge could cause harm

A significant number of patients leave the hospital with inappropriate drugs because of a lack of medication reconciliation at discharge, new research shows.

Proton pump inhibitors – known to have adverse effects, such as fractures, osteoporosis, and progressive kidney disease – make up 30% of inappropriate prescriptions at discharge.

“These medications can have a significant toxic effect, especially in the long term,” said Harsh Patel, MD, from Medical City Healthcare in Fort Worth, Tex.

And “when we interviewed patients, they were unable to recall ever partaking in a pulmonary function test or endoscopy to warrant the medications,” he said in an interview.

For their retrospective chart review, Dr. Patel and colleagues assessed patients admitted to the ICU in 13 hospitals over a 6-month period in northern Texas. Of the 12,930 patients, 2,557 had not previously received but were prescribed during their hospital stay a bronchodilator, a proton pump inhibitor, or an H2 receptor agonist.

Of those 2,557 patients, 26.8% were discharged on a proton pump inhibitor, 8.4% on an H2 receptor agonist, and 5.49% on a bronchodilator.

There were no corresponding diseases or diagnoses to justify continued use, Dr. Patel said during his presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians, held virtually this year.

Button fatigue

The problem stems from a technology disconnect when patients are transferred from the ICU to the general population.

Doctors expect that the medications will be reconciled at discharge, said one of the study investigators, Prashanth Reddy, MD, from Medical City Las Colinas (Tex.).

But in some instances, clinicians unfamiliar with the case click through the electronic health record to get the patient “out of the ICU to the floor,” he explained. “They don’t always know what medications to keep.”

“They may have button fatigue, so they just accept and continue,” Dr. Reddy said in an interviews.

In light of these findings, the team has kick-started a project to improve transition out of the ICU and minimize overprescription at discharge.

“This is the kind of a problem where we thought we could have some influence,” said Dr. Reddy.

One solution would be to put “stop orders” on potentially harmful medications. “But we don’t want to increase button fatigue even more, so we have to find a happy medium,” he said. “It’s going to take a while to formulate the best path on this.”

The inclusion of pharmacy residents in rounds could make a difference. “When we rounded with pharmacy residents, these issues got addressed,” Dr. Patel said. The pharmacy residents often asked: “Can we go over the meds? Does this person really need all this?”

Medication reconciliations not only have a positive effect on a patient’s health, they can also cut costs by eliminating unneeded drugs. And “patients are always happy to hear we’re taking them off a drug,” Dr. Patel added.

He said he remembers one of his mentors telling him that, if he could get his patients down to five medications, “then you’ve achieved success as a physician.”

“I’m still working toward that,” he said. “The end goal should sometimes be, less is more.”

COPD patients overprescribed home oxygen

In addition to medications, home oxygen therapy is often prescribed when patients are discharged from the hospital.

A study of 69 patients who were continued on home oxygen therapy after hospitalization for an exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was presented by Analisa Taylor, MD, from the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Despite guideline recommendations that patients be reassessed within 90 days of discharge, only 38 patients in the cohort were reassessed, and “28 were considered eligible for discontinuation,” she said during her presentation.

However, “of those, only four were ultimately discontinued,” she reported.

The reason for this gap needs to be examined, noted Dr. Taylor, suggesting that “perhaps clinical inertia plays a role in the continuation of previously prescribed therapy despite a lack of ongoing clinical benefit.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

A significant number of patients leave the hospital with inappropriate drugs because of a lack of medication reconciliation at discharge, new research shows.

Proton pump inhibitors – known to have adverse effects, such as fractures, osteoporosis, and progressive kidney disease – make up 30% of inappropriate prescriptions at discharge.

“These medications can have a significant toxic effect, especially in the long term,” said Harsh Patel, MD, from Medical City Healthcare in Fort Worth, Tex.

And “when we interviewed patients, they were unable to recall ever partaking in a pulmonary function test or endoscopy to warrant the medications,” he said in an interview.

For their retrospective chart review, Dr. Patel and colleagues assessed patients admitted to the ICU in 13 hospitals over a 6-month period in northern Texas. Of the 12,930 patients, 2,557 had not previously received but were prescribed during their hospital stay a bronchodilator, a proton pump inhibitor, or an H2 receptor agonist.

Of those 2,557 patients, 26.8% were discharged on a proton pump inhibitor, 8.4% on an H2 receptor agonist, and 5.49% on a bronchodilator.

There were no corresponding diseases or diagnoses to justify continued use, Dr. Patel said during his presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians, held virtually this year.

Button fatigue

The problem stems from a technology disconnect when patients are transferred from the ICU to the general population.

Doctors expect that the medications will be reconciled at discharge, said one of the study investigators, Prashanth Reddy, MD, from Medical City Las Colinas (Tex.).

But in some instances, clinicians unfamiliar with the case click through the electronic health record to get the patient “out of the ICU to the floor,” he explained. “They don’t always know what medications to keep.”

“They may have button fatigue, so they just accept and continue,” Dr. Reddy said in an interviews.

In light of these findings, the team has kick-started a project to improve transition out of the ICU and minimize overprescription at discharge.

“This is the kind of a problem where we thought we could have some influence,” said Dr. Reddy.

One solution would be to put “stop orders” on potentially harmful medications. “But we don’t want to increase button fatigue even more, so we have to find a happy medium,” he said. “It’s going to take a while to formulate the best path on this.”

The inclusion of pharmacy residents in rounds could make a difference. “When we rounded with pharmacy residents, these issues got addressed,” Dr. Patel said. The pharmacy residents often asked: “Can we go over the meds? Does this person really need all this?”

Medication reconciliations not only have a positive effect on a patient’s health, they can also cut costs by eliminating unneeded drugs. And “patients are always happy to hear we’re taking them off a drug,” Dr. Patel added.

He said he remembers one of his mentors telling him that, if he could get his patients down to five medications, “then you’ve achieved success as a physician.”

“I’m still working toward that,” he said. “The end goal should sometimes be, less is more.”

COPD patients overprescribed home oxygen

In addition to medications, home oxygen therapy is often prescribed when patients are discharged from the hospital.

A study of 69 patients who were continued on home oxygen therapy after hospitalization for an exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was presented by Analisa Taylor, MD, from the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Despite guideline recommendations that patients be reassessed within 90 days of discharge, only 38 patients in the cohort were reassessed, and “28 were considered eligible for discontinuation,” she said during her presentation.

However, “of those, only four were ultimately discontinued,” she reported.

The reason for this gap needs to be examined, noted Dr. Taylor, suggesting that “perhaps clinical inertia plays a role in the continuation of previously prescribed therapy despite a lack of ongoing clinical benefit.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

A significant number of patients leave the hospital with inappropriate drugs because of a lack of medication reconciliation at discharge, new research shows.

Proton pump inhibitors – known to have adverse effects, such as fractures, osteoporosis, and progressive kidney disease – make up 30% of inappropriate prescriptions at discharge.

“These medications can have a significant toxic effect, especially in the long term,” said Harsh Patel, MD, from Medical City Healthcare in Fort Worth, Tex.

And “when we interviewed patients, they were unable to recall ever partaking in a pulmonary function test or endoscopy to warrant the medications,” he said in an interview.

For their retrospective chart review, Dr. Patel and colleagues assessed patients admitted to the ICU in 13 hospitals over a 6-month period in northern Texas. Of the 12,930 patients, 2,557 had not previously received but were prescribed during their hospital stay a bronchodilator, a proton pump inhibitor, or an H2 receptor agonist.

Of those 2,557 patients, 26.8% were discharged on a proton pump inhibitor, 8.4% on an H2 receptor agonist, and 5.49% on a bronchodilator.

There were no corresponding diseases or diagnoses to justify continued use, Dr. Patel said during his presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians, held virtually this year.

Button fatigue

The problem stems from a technology disconnect when patients are transferred from the ICU to the general population.

Doctors expect that the medications will be reconciled at discharge, said one of the study investigators, Prashanth Reddy, MD, from Medical City Las Colinas (Tex.).

But in some instances, clinicians unfamiliar with the case click through the electronic health record to get the patient “out of the ICU to the floor,” he explained. “They don’t always know what medications to keep.”

“They may have button fatigue, so they just accept and continue,” Dr. Reddy said in an interviews.

In light of these findings, the team has kick-started a project to improve transition out of the ICU and minimize overprescription at discharge.

“This is the kind of a problem where we thought we could have some influence,” said Dr. Reddy.

One solution would be to put “stop orders” on potentially harmful medications. “But we don’t want to increase button fatigue even more, so we have to find a happy medium,” he said. “It’s going to take a while to formulate the best path on this.”

The inclusion of pharmacy residents in rounds could make a difference. “When we rounded with pharmacy residents, these issues got addressed,” Dr. Patel said. The pharmacy residents often asked: “Can we go over the meds? Does this person really need all this?”

Medication reconciliations not only have a positive effect on a patient’s health, they can also cut costs by eliminating unneeded drugs. And “patients are always happy to hear we’re taking them off a drug,” Dr. Patel added.

He said he remembers one of his mentors telling him that, if he could get his patients down to five medications, “then you’ve achieved success as a physician.”

“I’m still working toward that,” he said. “The end goal should sometimes be, less is more.”

COPD patients overprescribed home oxygen

In addition to medications, home oxygen therapy is often prescribed when patients are discharged from the hospital.

A study of 69 patients who were continued on home oxygen therapy after hospitalization for an exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was presented by Analisa Taylor, MD, from the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Despite guideline recommendations that patients be reassessed within 90 days of discharge, only 38 patients in the cohort were reassessed, and “28 were considered eligible for discontinuation,” she said during her presentation.

However, “of those, only four were ultimately discontinued,” she reported.

The reason for this gap needs to be examined, noted Dr. Taylor, suggesting that “perhaps clinical inertia plays a role in the continuation of previously prescribed therapy despite a lack of ongoing clinical benefit.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CHEST 2020

Switching to riociguat effective for some patients with PAH not at treatment goal

In patients with intermediate-risk pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) who are not at treatment goal on standard therapy, switching to riociguat is a promising strategy across a broad range of patient subgroups, an investigator said at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians, held virtually this year.

Patients switching to riociguat in the REPLACE study more frequently met the primary efficacy endpoint, compared with patients who remained on a phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5) inhibitor, said Marius M. Hoeper, MD, of the Clinic for Respiratory Medicine at Hannover (Germany) Medical School.

That clinical benefit of switching to riociguat, a soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) stimulator, was relatively consistent across patient subgroups including age, sex, PAH subtype, according to Dr. Hoeper.

“At the end of the day, we believe that switching from a PDE5 inhibitor to riociguat can benefit patients with PAH at intermediate risk and may serve as a new strategic option for treatment escalation,” he said in a live virtual presentation of the study results.

About 40% of patients switching to riociguat met the primary endpoint of clinical improvement in absence of clinical worsening versus just 20% of patients who stayed on a PDE5 inhibitor, according to top-line results of the phase 4 REPLACE study, which were reported Sept. 7 at the annual meeting of the European Respiratory Society.

Results of REPLACE presented at the CHEST meeting show a benefit across most patient subgroups, including PAH subtype and whether patients came from monotherapy or combination treatment to riociguat. Some groups did not appear to respond quite as well to switching, including elderly patients, patients with a 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) of less than 320 meters at baseline, and patients switching from tadalafil as opposed to sildenafil. However, these findings were not statistically significant and may have been chance findings, according to Dr. Hoeper.

These results of REPLACE suggest the efficacy of riociguat “across the board” for intermediate-risk PAH patients with inadequate response to standard therapy, said Vijay Balasubramanian, MD, FCCP, clinical professor of medicine at the University of California San Francisco, Fresno.

Based on REPLACE results, switching from a PDE5 inhibitor to riociguat is now a “strong potential option” beyond adding a third drug such as selexipag or an inhaled prostacyclin to usual treatment with a PDE5 inhibitor plus an endothelin receptor antagonist, Dr. Balasubramanian said in an interview.

“We now have an evidence-based option where you can stay on a two-drug regimen and see whether the switch would work just as well,” said Dr. Balasubramanian, vice chair of the Pulmonary Vascular Disease Steering Committee for the American College of Chest Physicians.

REPLACE is a randomized phase 4 study including 226 patients with PAH considered to be at intermediate risk according to World Health Organization functional class III or 6MWD of 165-440 meters. The composite primary endpoint was defined as no clinical worsening (death, disease progression, or hospitalization for worsening PAH) plus clinical improvement on at least two measures including an improvement in 6MWD, achieving WHO functional class I/II, or a decrease in N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP).

The primary endpoint of REPLACE was met, showing that 45 patients (41%) who switched to riociguat had clinical improvement without clinical worsening versus 22 patient (20%) who stayed on the PDE5 inhibitor (odds ratio, 2.78; 95% confidence interval, 1.53-5.06; P = .0007), Dr. Hoeper reported.

The benefit appeared consistent across PAH subgroups, according to Dr. Hoeper. In patients with idiopathic, heritable, or drug- and toxin-induced PAH, the primary endpoint favored riociguat over PDE5 inhibitor, at 45% and 23%, respectively. Similarly, a higher proportion of patients with PAH associated with congenital heart disease or portal hypertension achieved the primary endpoint (46% vs. 8%), as did patients with PAH associated with connective tissue disease (25% vs. 16%).

Adverse events were seen in 71% of riociguat-treated patients and 66% of PDE5 inhibitor–treated patients, according to Dr. Hoeper, who said severe adverse events were more frequent with PDE5-inhibitor treatment, at 17% versus 7% for riociguat. There were three clinical worsening events in the PDE5 inhibitor group leading to death, while a fourth patient died in safety follow-up, according to the reported results, whereas there were no deaths reported with riociguat.

The REPLACE study was cofunded by Bayer AG and Merck Sharpe & Dohme, a subsidiary of Merck & Co. Dr. Hoeper reported receiving fees for consultations or lectures from Acceleron, Actelion, Bayer AG, Janssen, MSD, and Pfizer.

SOURCE: Hoeper MM. CHEST 2020, Abstract A2156-A2159.

In patients with intermediate-risk pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) who are not at treatment goal on standard therapy, switching to riociguat is a promising strategy across a broad range of patient subgroups, an investigator said at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians, held virtually this year.

Patients switching to riociguat in the REPLACE study more frequently met the primary efficacy endpoint, compared with patients who remained on a phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5) inhibitor, said Marius M. Hoeper, MD, of the Clinic for Respiratory Medicine at Hannover (Germany) Medical School.

That clinical benefit of switching to riociguat, a soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) stimulator, was relatively consistent across patient subgroups including age, sex, PAH subtype, according to Dr. Hoeper.

“At the end of the day, we believe that switching from a PDE5 inhibitor to riociguat can benefit patients with PAH at intermediate risk and may serve as a new strategic option for treatment escalation,” he said in a live virtual presentation of the study results.

About 40% of patients switching to riociguat met the primary endpoint of clinical improvement in absence of clinical worsening versus just 20% of patients who stayed on a PDE5 inhibitor, according to top-line results of the phase 4 REPLACE study, which were reported Sept. 7 at the annual meeting of the European Respiratory Society.

Results of REPLACE presented at the CHEST meeting show a benefit across most patient subgroups, including PAH subtype and whether patients came from monotherapy or combination treatment to riociguat. Some groups did not appear to respond quite as well to switching, including elderly patients, patients with a 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) of less than 320 meters at baseline, and patients switching from tadalafil as opposed to sildenafil. However, these findings were not statistically significant and may have been chance findings, according to Dr. Hoeper.

These results of REPLACE suggest the efficacy of riociguat “across the board” for intermediate-risk PAH patients with inadequate response to standard therapy, said Vijay Balasubramanian, MD, FCCP, clinical professor of medicine at the University of California San Francisco, Fresno.

Based on REPLACE results, switching from a PDE5 inhibitor to riociguat is now a “strong potential option” beyond adding a third drug such as selexipag or an inhaled prostacyclin to usual treatment with a PDE5 inhibitor plus an endothelin receptor antagonist, Dr. Balasubramanian said in an interview.

“We now have an evidence-based option where you can stay on a two-drug regimen and see whether the switch would work just as well,” said Dr. Balasubramanian, vice chair of the Pulmonary Vascular Disease Steering Committee for the American College of Chest Physicians.

REPLACE is a randomized phase 4 study including 226 patients with PAH considered to be at intermediate risk according to World Health Organization functional class III or 6MWD of 165-440 meters. The composite primary endpoint was defined as no clinical worsening (death, disease progression, or hospitalization for worsening PAH) plus clinical improvement on at least two measures including an improvement in 6MWD, achieving WHO functional class I/II, or a decrease in N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP).

The primary endpoint of REPLACE was met, showing that 45 patients (41%) who switched to riociguat had clinical improvement without clinical worsening versus 22 patient (20%) who stayed on the PDE5 inhibitor (odds ratio, 2.78; 95% confidence interval, 1.53-5.06; P = .0007), Dr. Hoeper reported.

The benefit appeared consistent across PAH subgroups, according to Dr. Hoeper. In patients with idiopathic, heritable, or drug- and toxin-induced PAH, the primary endpoint favored riociguat over PDE5 inhibitor, at 45% and 23%, respectively. Similarly, a higher proportion of patients with PAH associated with congenital heart disease or portal hypertension achieved the primary endpoint (46% vs. 8%), as did patients with PAH associated with connective tissue disease (25% vs. 16%).

Adverse events were seen in 71% of riociguat-treated patients and 66% of PDE5 inhibitor–treated patients, according to Dr. Hoeper, who said severe adverse events were more frequent with PDE5-inhibitor treatment, at 17% versus 7% for riociguat. There were three clinical worsening events in the PDE5 inhibitor group leading to death, while a fourth patient died in safety follow-up, according to the reported results, whereas there were no deaths reported with riociguat.

The REPLACE study was cofunded by Bayer AG and Merck Sharpe & Dohme, a subsidiary of Merck & Co. Dr. Hoeper reported receiving fees for consultations or lectures from Acceleron, Actelion, Bayer AG, Janssen, MSD, and Pfizer.

SOURCE: Hoeper MM. CHEST 2020, Abstract A2156-A2159.

In patients with intermediate-risk pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) who are not at treatment goal on standard therapy, switching to riociguat is a promising strategy across a broad range of patient subgroups, an investigator said at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians, held virtually this year.

Patients switching to riociguat in the REPLACE study more frequently met the primary efficacy endpoint, compared with patients who remained on a phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5) inhibitor, said Marius M. Hoeper, MD, of the Clinic for Respiratory Medicine at Hannover (Germany) Medical School.

That clinical benefit of switching to riociguat, a soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) stimulator, was relatively consistent across patient subgroups including age, sex, PAH subtype, according to Dr. Hoeper.

“At the end of the day, we believe that switching from a PDE5 inhibitor to riociguat can benefit patients with PAH at intermediate risk and may serve as a new strategic option for treatment escalation,” he said in a live virtual presentation of the study results.

About 40% of patients switching to riociguat met the primary endpoint of clinical improvement in absence of clinical worsening versus just 20% of patients who stayed on a PDE5 inhibitor, according to top-line results of the phase 4 REPLACE study, which were reported Sept. 7 at the annual meeting of the European Respiratory Society.

Results of REPLACE presented at the CHEST meeting show a benefit across most patient subgroups, including PAH subtype and whether patients came from monotherapy or combination treatment to riociguat. Some groups did not appear to respond quite as well to switching, including elderly patients, patients with a 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) of less than 320 meters at baseline, and patients switching from tadalafil as opposed to sildenafil. However, these findings were not statistically significant and may have been chance findings, according to Dr. Hoeper.

These results of REPLACE suggest the efficacy of riociguat “across the board” for intermediate-risk PAH patients with inadequate response to standard therapy, said Vijay Balasubramanian, MD, FCCP, clinical professor of medicine at the University of California San Francisco, Fresno.

Based on REPLACE results, switching from a PDE5 inhibitor to riociguat is now a “strong potential option” beyond adding a third drug such as selexipag or an inhaled prostacyclin to usual treatment with a PDE5 inhibitor plus an endothelin receptor antagonist, Dr. Balasubramanian said in an interview.

“We now have an evidence-based option where you can stay on a two-drug regimen and see whether the switch would work just as well,” said Dr. Balasubramanian, vice chair of the Pulmonary Vascular Disease Steering Committee for the American College of Chest Physicians.

REPLACE is a randomized phase 4 study including 226 patients with PAH considered to be at intermediate risk according to World Health Organization functional class III or 6MWD of 165-440 meters. The composite primary endpoint was defined as no clinical worsening (death, disease progression, or hospitalization for worsening PAH) plus clinical improvement on at least two measures including an improvement in 6MWD, achieving WHO functional class I/II, or a decrease in N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP).

The primary endpoint of REPLACE was met, showing that 45 patients (41%) who switched to riociguat had clinical improvement without clinical worsening versus 22 patient (20%) who stayed on the PDE5 inhibitor (odds ratio, 2.78; 95% confidence interval, 1.53-5.06; P = .0007), Dr. Hoeper reported.

The benefit appeared consistent across PAH subgroups, according to Dr. Hoeper. In patients with idiopathic, heritable, or drug- and toxin-induced PAH, the primary endpoint favored riociguat over PDE5 inhibitor, at 45% and 23%, respectively. Similarly, a higher proportion of patients with PAH associated with congenital heart disease or portal hypertension achieved the primary endpoint (46% vs. 8%), as did patients with PAH associated with connective tissue disease (25% vs. 16%).

Adverse events were seen in 71% of riociguat-treated patients and 66% of PDE5 inhibitor–treated patients, according to Dr. Hoeper, who said severe adverse events were more frequent with PDE5-inhibitor treatment, at 17% versus 7% for riociguat. There were three clinical worsening events in the PDE5 inhibitor group leading to death, while a fourth patient died in safety follow-up, according to the reported results, whereas there were no deaths reported with riociguat.

The REPLACE study was cofunded by Bayer AG and Merck Sharpe & Dohme, a subsidiary of Merck & Co. Dr. Hoeper reported receiving fees for consultations or lectures from Acceleron, Actelion, Bayer AG, Janssen, MSD, and Pfizer.

SOURCE: Hoeper MM. CHEST 2020, Abstract A2156-A2159.

FROM CHEST 2020

Score predicts risk for ventilation in COVID-19 patients

A new scoring system can predict whether COVID-19 patients will require invasive mechanical ventilation, researchers report.

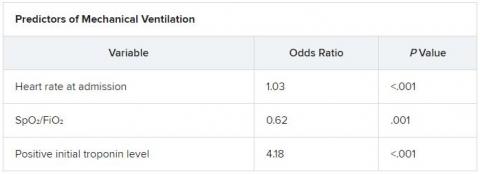

The score uses three variables to predict future risk: heart rate; the ratio of oxygen saturation (SpO2) to fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2); and a positive troponin I level.

“What excites us is it’s a really benign tool,” said Muhtadi Alnababteh, MD, from the Medstar Washington (D.C.) Hospital Center. “For the first two variables you only need to look at vital signs, no labs or invasive diagnostics.”

“The third part is a simple lab, which is performed universally and can be done in any hospital,” he told this news organization. “We know that even rural hospitals can do this.”

For their retrospective analysis, Dr. Alnababteh and his colleagues assessed 265 adults with confirmed COVID-19 infection who were admitted to a single tertiary care center in March and April. They looked at demographic characteristics, lab results, and clinical and outcome information.

Ultimately, 54 of these patients required invasive mechanical ventilation.

On multiple-regression analysis, the researchers determined that three variables independently predicted the need for invasive mechanical ventilation.

Calibration of the model was good (Hosmer–Lemeshow score, 6.3; P = .39), as was predictive ability (area under the curve, 0.80).

The risk for invasive mechanical ventilation increased as the number of positive variables increased (P < .001), from 15.4% for those with one positive variable, to 29.0% for those with two, to 60.5% for those with three positive variables.

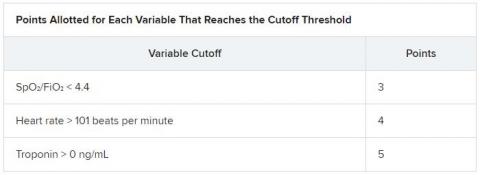

The team established cutoff points for each variable and developed a points-based scoring system to predict risk.

It was an initial surprise that troponin – a cardiac marker – would be a risk factor. “Originally, we thought COVID-19 only affects the lung,” Dr. Alnababteh explained during his presentation at CHEST 2020. Later studies, however, showed it can cause myocarditis symptoms.

The case for looking at cardiac markers was made when a study of young athletes who recovered from COVID-19 after experiencing mild or no symptoms showed that 15% had signs of myocarditis on cardiac MRI.

“If mild COVID disease in young patients caused cardiac injury, you can imagine what it can do to older patients with severe disease,” Alnababteh said.

This tool will help triage patients who are not sick enough for the ICU but are known to be at high risk for ventilation. “It’s one of the biggest decisions you have to make: Where do you send your patient? This score helps determine that,” he said.

The researchers are now working to validate the score and evaluate how it performs, he reported.

Existing scores evaluated for COVID-19 outcome prediction

The MuLBSTA score can also be used to predict outcomes in patients with COVID-19.

A retrospective evaluation of 163 patients was presented at CHEST 2020 by Jurgena Tusha, MD, from Wayne State University in Detroit.

Patients who survived their illness had a mean MuLBSTA score of 8.67, whereas patients who died had a mean score of 13.60.

The score “correlated significantly with mortality, ventilator support, and length of stay, which may be used to provide guidance to screen patients and make further clinical decisions,” Dr. Tusha said in a press release.

“Further studies are required to validate this study in larger patient cohorts,” she added.

The three-variable scoring system is easier to use than the MuLBSTA, and more specific, said Dr. Alnababteh.

“The main difference between our study and the MuLBSTA study is that we came up with a novel score for COVID-19 patients,” he said. “Our study score doesn’t require chest x-rays or blood cultures, and the outcome is need for invasive mechanical ventilation, not mortality.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

A new scoring system can predict whether COVID-19 patients will require invasive mechanical ventilation, researchers report.

The score uses three variables to predict future risk: heart rate; the ratio of oxygen saturation (SpO2) to fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2); and a positive troponin I level.

“What excites us is it’s a really benign tool,” said Muhtadi Alnababteh, MD, from the Medstar Washington (D.C.) Hospital Center. “For the first two variables you only need to look at vital signs, no labs or invasive diagnostics.”

“The third part is a simple lab, which is performed universally and can be done in any hospital,” he told this news organization. “We know that even rural hospitals can do this.”

For their retrospective analysis, Dr. Alnababteh and his colleagues assessed 265 adults with confirmed COVID-19 infection who were admitted to a single tertiary care center in March and April. They looked at demographic characteristics, lab results, and clinical and outcome information.

Ultimately, 54 of these patients required invasive mechanical ventilation.

On multiple-regression analysis, the researchers determined that three variables independently predicted the need for invasive mechanical ventilation.

Calibration of the model was good (Hosmer–Lemeshow score, 6.3; P = .39), as was predictive ability (area under the curve, 0.80).

The risk for invasive mechanical ventilation increased as the number of positive variables increased (P < .001), from 15.4% for those with one positive variable, to 29.0% for those with two, to 60.5% for those with three positive variables.

The team established cutoff points for each variable and developed a points-based scoring system to predict risk.

It was an initial surprise that troponin – a cardiac marker – would be a risk factor. “Originally, we thought COVID-19 only affects the lung,” Dr. Alnababteh explained during his presentation at CHEST 2020. Later studies, however, showed it can cause myocarditis symptoms.

The case for looking at cardiac markers was made when a study of young athletes who recovered from COVID-19 after experiencing mild or no symptoms showed that 15% had signs of myocarditis on cardiac MRI.

“If mild COVID disease in young patients caused cardiac injury, you can imagine what it can do to older patients with severe disease,” Alnababteh said.

This tool will help triage patients who are not sick enough for the ICU but are known to be at high risk for ventilation. “It’s one of the biggest decisions you have to make: Where do you send your patient? This score helps determine that,” he said.

The researchers are now working to validate the score and evaluate how it performs, he reported.

Existing scores evaluated for COVID-19 outcome prediction

The MuLBSTA score can also be used to predict outcomes in patients with COVID-19.

A retrospective evaluation of 163 patients was presented at CHEST 2020 by Jurgena Tusha, MD, from Wayne State University in Detroit.

Patients who survived their illness had a mean MuLBSTA score of 8.67, whereas patients who died had a mean score of 13.60.

The score “correlated significantly with mortality, ventilator support, and length of stay, which may be used to provide guidance to screen patients and make further clinical decisions,” Dr. Tusha said in a press release.

“Further studies are required to validate this study in larger patient cohorts,” she added.

The three-variable scoring system is easier to use than the MuLBSTA, and more specific, said Dr. Alnababteh.

“The main difference between our study and the MuLBSTA study is that we came up with a novel score for COVID-19 patients,” he said. “Our study score doesn’t require chest x-rays or blood cultures, and the outcome is need for invasive mechanical ventilation, not mortality.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

A new scoring system can predict whether COVID-19 patients will require invasive mechanical ventilation, researchers report.

The score uses three variables to predict future risk: heart rate; the ratio of oxygen saturation (SpO2) to fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2); and a positive troponin I level.

“What excites us is it’s a really benign tool,” said Muhtadi Alnababteh, MD, from the Medstar Washington (D.C.) Hospital Center. “For the first two variables you only need to look at vital signs, no labs or invasive diagnostics.”

“The third part is a simple lab, which is performed universally and can be done in any hospital,” he told this news organization. “We know that even rural hospitals can do this.”

For their retrospective analysis, Dr. Alnababteh and his colleagues assessed 265 adults with confirmed COVID-19 infection who were admitted to a single tertiary care center in March and April. They looked at demographic characteristics, lab results, and clinical and outcome information.

Ultimately, 54 of these patients required invasive mechanical ventilation.

On multiple-regression analysis, the researchers determined that three variables independently predicted the need for invasive mechanical ventilation.

Calibration of the model was good (Hosmer–Lemeshow score, 6.3; P = .39), as was predictive ability (area under the curve, 0.80).

The risk for invasive mechanical ventilation increased as the number of positive variables increased (P < .001), from 15.4% for those with one positive variable, to 29.0% for those with two, to 60.5% for those with three positive variables.

The team established cutoff points for each variable and developed a points-based scoring system to predict risk.

It was an initial surprise that troponin – a cardiac marker – would be a risk factor. “Originally, we thought COVID-19 only affects the lung,” Dr. Alnababteh explained during his presentation at CHEST 2020. Later studies, however, showed it can cause myocarditis symptoms.

The case for looking at cardiac markers was made when a study of young athletes who recovered from COVID-19 after experiencing mild or no symptoms showed that 15% had signs of myocarditis on cardiac MRI.

“If mild COVID disease in young patients caused cardiac injury, you can imagine what it can do to older patients with severe disease,” Alnababteh said.

This tool will help triage patients who are not sick enough for the ICU but are known to be at high risk for ventilation. “It’s one of the biggest decisions you have to make: Where do you send your patient? This score helps determine that,” he said.

The researchers are now working to validate the score and evaluate how it performs, he reported.

Existing scores evaluated for COVID-19 outcome prediction

The MuLBSTA score can also be used to predict outcomes in patients with COVID-19.

A retrospective evaluation of 163 patients was presented at CHEST 2020 by Jurgena Tusha, MD, from Wayne State University in Detroit.

Patients who survived their illness had a mean MuLBSTA score of 8.67, whereas patients who died had a mean score of 13.60.

The score “correlated significantly with mortality, ventilator support, and length of stay, which may be used to provide guidance to screen patients and make further clinical decisions,” Dr. Tusha said in a press release.

“Further studies are required to validate this study in larger patient cohorts,” she added.

The three-variable scoring system is easier to use than the MuLBSTA, and more specific, said Dr. Alnababteh.

“The main difference between our study and the MuLBSTA study is that we came up with a novel score for COVID-19 patients,” he said. “Our study score doesn’t require chest x-rays or blood cultures, and the outcome is need for invasive mechanical ventilation, not mortality.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Certain statins linked to lower mortality risk in patients admitted for sepsis

Among individuals admitted to hospitals with sepsis, statin users had a lower mortality, compared with nonstatin users, according to a recent analysis focused on a large and diverse cohort of patients in California.

Mortality hazard ratios at 30 and 90 days were lower by about 20% for statin users admitted for sepsis, compared with nonstatin users, according to results of the retrospective cohort study.

Hydrophilic and synthetic statins had more favorable mortality outcomes, compared with lipophilic and fungal-derived statins, respectively, added investigator Brannen Liang, MD, a third-year internal medicine resident at Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles Medical Center.

These findings suggest a potential benefit of statins in patients with sepsis, with certain types of statins having a greater protective effect than others, according to Dr. Liang, who presented the original research in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians, held virtually this year.

“I think there’s potential for extending the use of statins to other indications, such as sepsis,” Dr. Liang said in an interview, though he also cautioned that the present study is hypothesis generating and more research is necessary.

Using a certain statin type over another (i.e., a hydrophilic, synthetic statin) might be a consideration for populations who are at greater risk for sepsis, such as the immunocompromised, patients with diabetes, or elderly and who also require a statin for an indication such as hyperlipidemia, he added.

While the link between statin use and sepsis mortality outcomes is not new, this study is unique in that it replicates results of earlier studies in a large and diverse real-world population, Dr. Liang said.

“Numerous studies seem to suggest that statins may play a role in attenuating the mortality of patients admitted to the hospital with sepsis, for whatever reason – whether this is due to their anti-inflammatory effects, their lipid-lowering effects, or if they truly have an antimicrobial effect, which has been studied in vitro and in animal studies,” he said in an interview.

It’s impossible to definitively conclude from retrospective studies such as this whether statins reduce sepsis-related mortality risk, but the present study at least makes the case for using certain types of statins when they are indicated in high-risk patients, said Steven Q. Simpson, MD, FCCP, professor of medicine in the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at the University of Kansas, Kansas City.

“If you have patients at high risk for sepsis and they need a statin, you could give consideration to using a hydrophilic and synthetic statin, rather than either of the other choices,” said Dr. Simpson, CHEST president-elect and senior advisor to the Solving Sepsis initiative of the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority of the Department of Health & Human Services.

The retrospective cohort study by Dr. Liang and colleagues included a total of 137,019 individuals admitted for sepsis within the Kaiser Permanente Southern California health system between 2008 and 2018. Of that group, 36,908 were taking a statin.

Overall, the mean age of patients admitted for sepsis was 66.9 years, and 50.4% were female. Nearly 50% were White, about 12% were Black, 28% were Hispanic, and 8% were Asian. A diagnosis of ischemic heart disease was reported for 43% of statin users and 23% of nonusers, while diabetes mellitus was reported for 60% of statin users and 37% of nonusers (P < .0001 for both comparisons).

Differences in mortality favored statin users, compared with nonusers, with hazard ratios of 0.79 (95% confidence interval, 0.77-0.82) at 30 days and similarly, 0.79 (95% CI, 0.77-0.81) at 90 days, Dr. Liang reported, noting that the models were adjusted for age, race, sex, and comorbidities.

Further analysis suggested a mortality advantage of lipophilic, compared with hydrophilic statins, and an advantage of fungal-derived statins over synthetic-derived statins, the investigator added.

In the comparison of lipophilic statin users and hydrophilic statin users, the 30- and 90-day mortality HRs were 1.13 (95% CI, 1.02-1.26) and 1.17 (95% CI, 1.07-1.28), respectively, the data show. For fungal-derived statin users, compared with synthetic derived statin users, 30- and 90-day mortality HRs were 1.12 (95% CI, 1.06-1.19) and 1.14 (95% CI, 1.09-1.20), respectively.

Dr. Liang and coauthors disclosed no relevant relationships with respect to the work presented at the CHEST meeting.

SOURCE: Liang B et al. CHEST 2020, Abstract A589.

Among individuals admitted to hospitals with sepsis, statin users had a lower mortality, compared with nonstatin users, according to a recent analysis focused on a large and diverse cohort of patients in California.

Mortality hazard ratios at 30 and 90 days were lower by about 20% for statin users admitted for sepsis, compared with nonstatin users, according to results of the retrospective cohort study.

Hydrophilic and synthetic statins had more favorable mortality outcomes, compared with lipophilic and fungal-derived statins, respectively, added investigator Brannen Liang, MD, a third-year internal medicine resident at Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles Medical Center.

These findings suggest a potential benefit of statins in patients with sepsis, with certain types of statins having a greater protective effect than others, according to Dr. Liang, who presented the original research in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians, held virtually this year.

“I think there’s potential for extending the use of statins to other indications, such as sepsis,” Dr. Liang said in an interview, though he also cautioned that the present study is hypothesis generating and more research is necessary.

Using a certain statin type over another (i.e., a hydrophilic, synthetic statin) might be a consideration for populations who are at greater risk for sepsis, such as the immunocompromised, patients with diabetes, or elderly and who also require a statin for an indication such as hyperlipidemia, he added.

While the link between statin use and sepsis mortality outcomes is not new, this study is unique in that it replicates results of earlier studies in a large and diverse real-world population, Dr. Liang said.

“Numerous studies seem to suggest that statins may play a role in attenuating the mortality of patients admitted to the hospital with sepsis, for whatever reason – whether this is due to their anti-inflammatory effects, their lipid-lowering effects, or if they truly have an antimicrobial effect, which has been studied in vitro and in animal studies,” he said in an interview.

It’s impossible to definitively conclude from retrospective studies such as this whether statins reduce sepsis-related mortality risk, but the present study at least makes the case for using certain types of statins when they are indicated in high-risk patients, said Steven Q. Simpson, MD, FCCP, professor of medicine in the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at the University of Kansas, Kansas City.

“If you have patients at high risk for sepsis and they need a statin, you could give consideration to using a hydrophilic and synthetic statin, rather than either of the other choices,” said Dr. Simpson, CHEST president-elect and senior advisor to the Solving Sepsis initiative of the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority of the Department of Health & Human Services.

The retrospective cohort study by Dr. Liang and colleagues included a total of 137,019 individuals admitted for sepsis within the Kaiser Permanente Southern California health system between 2008 and 2018. Of that group, 36,908 were taking a statin.

Overall, the mean age of patients admitted for sepsis was 66.9 years, and 50.4% were female. Nearly 50% were White, about 12% were Black, 28% were Hispanic, and 8% were Asian. A diagnosis of ischemic heart disease was reported for 43% of statin users and 23% of nonusers, while diabetes mellitus was reported for 60% of statin users and 37% of nonusers (P < .0001 for both comparisons).

Differences in mortality favored statin users, compared with nonusers, with hazard ratios of 0.79 (95% confidence interval, 0.77-0.82) at 30 days and similarly, 0.79 (95% CI, 0.77-0.81) at 90 days, Dr. Liang reported, noting that the models were adjusted for age, race, sex, and comorbidities.

Further analysis suggested a mortality advantage of lipophilic, compared with hydrophilic statins, and an advantage of fungal-derived statins over synthetic-derived statins, the investigator added.

In the comparison of lipophilic statin users and hydrophilic statin users, the 30- and 90-day mortality HRs were 1.13 (95% CI, 1.02-1.26) and 1.17 (95% CI, 1.07-1.28), respectively, the data show. For fungal-derived statin users, compared with synthetic derived statin users, 30- and 90-day mortality HRs were 1.12 (95% CI, 1.06-1.19) and 1.14 (95% CI, 1.09-1.20), respectively.

Dr. Liang and coauthors disclosed no relevant relationships with respect to the work presented at the CHEST meeting.

SOURCE: Liang B et al. CHEST 2020, Abstract A589.

Among individuals admitted to hospitals with sepsis, statin users had a lower mortality, compared with nonstatin users, according to a recent analysis focused on a large and diverse cohort of patients in California.

Mortality hazard ratios at 30 and 90 days were lower by about 20% for statin users admitted for sepsis, compared with nonstatin users, according to results of the retrospective cohort study.

Hydrophilic and synthetic statins had more favorable mortality outcomes, compared with lipophilic and fungal-derived statins, respectively, added investigator Brannen Liang, MD, a third-year internal medicine resident at Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles Medical Center.

These findings suggest a potential benefit of statins in patients with sepsis, with certain types of statins having a greater protective effect than others, according to Dr. Liang, who presented the original research in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians, held virtually this year.