User login

Congenital heart disease screening cuts infant mortality

BALTIMORE – The mandate to screen all U.S.-born neonates for critical congenital heart disease that started in 2011 has had an apparent effect on infant mortality.

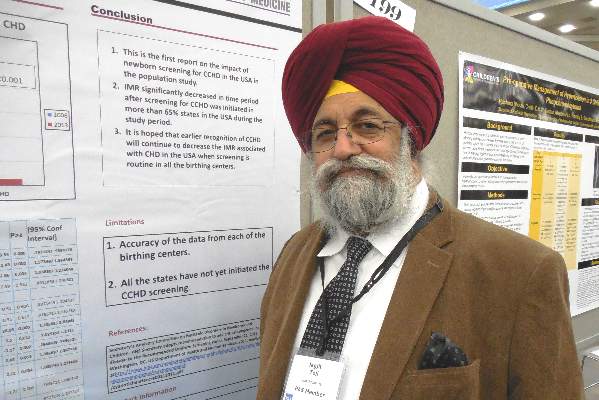

By 2013, national U.S. data showed that the number of U.S. infants who died attributable to congenital heart disease had dropped by a small but statistically significant percentage, compared with a reference year prior to initiation of the mandate, 2006, Dr. Jagjit S. Teji reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

“This is the first report on the impact of newborn screening for critical congenital heart disease,” said Dr. Teji, a neonatologist at Northwestern University in Chicago.

He analyzed birth and death records from the U.S. National Center for Health Statistics and calculated that infant mortality in 2013, compared with 2006, included roughly 100 fewer infants deaths attributable to congenital heart disease, a statistically significant difference, after adjusting for differences in variables between the 2 years that could affect mortality, including gestational ages at delivery, birth weight, maternal age, race, ethnicity, and marital status. The decrease occurred despite an overall increase in U.S. births of about 8% from 2006 to 2013.

In 2013, the rate of infant mortality was 0.027%, while in 2006 it was 0.032%, Dr. Teji reported. The decrease that appeared attributable to early screening for critical congenital heart disease was especially notable because by 2013 only two-thirds of states had a rule in place mandating newborn screening following the 2011 recommendation from the Department of Health & Human Services to U.S. clinicians to noninvasively measure blood oxygenation levels in the upper and lower limbs of newborns, using pulse oximetry, Dr. Teji said. By April 2016, this had grown to 48 states with mandates for newborn screening of critical congenital heart disease, usually performed just before newborns are discharged or after they are 24 hours old. Idaho and Wyoming are the exceptions.

Dr. Teji had no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BALTIMORE – The mandate to screen all U.S.-born neonates for critical congenital heart disease that started in 2011 has had an apparent effect on infant mortality.

By 2013, national U.S. data showed that the number of U.S. infants who died attributable to congenital heart disease had dropped by a small but statistically significant percentage, compared with a reference year prior to initiation of the mandate, 2006, Dr. Jagjit S. Teji reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

“This is the first report on the impact of newborn screening for critical congenital heart disease,” said Dr. Teji, a neonatologist at Northwestern University in Chicago.

He analyzed birth and death records from the U.S. National Center for Health Statistics and calculated that infant mortality in 2013, compared with 2006, included roughly 100 fewer infants deaths attributable to congenital heart disease, a statistically significant difference, after adjusting for differences in variables between the 2 years that could affect mortality, including gestational ages at delivery, birth weight, maternal age, race, ethnicity, and marital status. The decrease occurred despite an overall increase in U.S. births of about 8% from 2006 to 2013.

In 2013, the rate of infant mortality was 0.027%, while in 2006 it was 0.032%, Dr. Teji reported. The decrease that appeared attributable to early screening for critical congenital heart disease was especially notable because by 2013 only two-thirds of states had a rule in place mandating newborn screening following the 2011 recommendation from the Department of Health & Human Services to U.S. clinicians to noninvasively measure blood oxygenation levels in the upper and lower limbs of newborns, using pulse oximetry, Dr. Teji said. By April 2016, this had grown to 48 states with mandates for newborn screening of critical congenital heart disease, usually performed just before newborns are discharged or after they are 24 hours old. Idaho and Wyoming are the exceptions.

Dr. Teji had no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BALTIMORE – The mandate to screen all U.S.-born neonates for critical congenital heart disease that started in 2011 has had an apparent effect on infant mortality.

By 2013, national U.S. data showed that the number of U.S. infants who died attributable to congenital heart disease had dropped by a small but statistically significant percentage, compared with a reference year prior to initiation of the mandate, 2006, Dr. Jagjit S. Teji reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

“This is the first report on the impact of newborn screening for critical congenital heart disease,” said Dr. Teji, a neonatologist at Northwestern University in Chicago.

He analyzed birth and death records from the U.S. National Center for Health Statistics and calculated that infant mortality in 2013, compared with 2006, included roughly 100 fewer infants deaths attributable to congenital heart disease, a statistically significant difference, after adjusting for differences in variables between the 2 years that could affect mortality, including gestational ages at delivery, birth weight, maternal age, race, ethnicity, and marital status. The decrease occurred despite an overall increase in U.S. births of about 8% from 2006 to 2013.

In 2013, the rate of infant mortality was 0.027%, while in 2006 it was 0.032%, Dr. Teji reported. The decrease that appeared attributable to early screening for critical congenital heart disease was especially notable because by 2013 only two-thirds of states had a rule in place mandating newborn screening following the 2011 recommendation from the Department of Health & Human Services to U.S. clinicians to noninvasively measure blood oxygenation levels in the upper and lower limbs of newborns, using pulse oximetry, Dr. Teji said. By April 2016, this had grown to 48 states with mandates for newborn screening of critical congenital heart disease, usually performed just before newborns are discharged or after they are 24 hours old. Idaho and Wyoming are the exceptions.

Dr. Teji had no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE PAS ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Universal screening of U.S. neonates for critical congenital heart disease appeared to result in a significant reduction in infant mortality by 2013.

Major finding: U.S. infant mortality fell from an adjusted rate of 0.032% in 2006 to 0.027% in 2013, a statistically significant difference.

Data source: U.S. birth and death records from the National Center for Health Statistics.

Disclosures: Dr. Teji had no relevant financial disclosures.

VIDEO: Childhood obesity, particularly severe obesity, is not declining

BALTIMORE – Rates of obesity, particularly severe obesity, in children have not decreased since 1999, despite what recent studies may say, according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

“Overall, there is no evidence of a decrease in obesity in any of our age groups,” said Asheley C. Skinner, Ph.D., of Duke University in Durham, N.C., adding that “we see a sort of consistent, ongoing increase up through 2014 for severe obesity and regular class I obesity for all of our age groups.”

In a video interview, Dr. Skinner discussed the findings of her study, in which data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) from the years 1999-2014 were examined to determine obesity in children aged 2-19 years. A combination of body mass index (BMI) and “a percentage of the 95th percentile” of weight across three age groups – 2-5 years, 6-11 years, and 12-19 years – was used to classify children with class I, class II, or class III (severe) obesity.

Dr. Skinner did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

BALTIMORE – Rates of obesity, particularly severe obesity, in children have not decreased since 1999, despite what recent studies may say, according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

“Overall, there is no evidence of a decrease in obesity in any of our age groups,” said Asheley C. Skinner, Ph.D., of Duke University in Durham, N.C., adding that “we see a sort of consistent, ongoing increase up through 2014 for severe obesity and regular class I obesity for all of our age groups.”

In a video interview, Dr. Skinner discussed the findings of her study, in which data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) from the years 1999-2014 were examined to determine obesity in children aged 2-19 years. A combination of body mass index (BMI) and “a percentage of the 95th percentile” of weight across three age groups – 2-5 years, 6-11 years, and 12-19 years – was used to classify children with class I, class II, or class III (severe) obesity.

Dr. Skinner did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

BALTIMORE – Rates of obesity, particularly severe obesity, in children have not decreased since 1999, despite what recent studies may say, according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

“Overall, there is no evidence of a decrease in obesity in any of our age groups,” said Asheley C. Skinner, Ph.D., of Duke University in Durham, N.C., adding that “we see a sort of consistent, ongoing increase up through 2014 for severe obesity and regular class I obesity for all of our age groups.”

In a video interview, Dr. Skinner discussed the findings of her study, in which data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) from the years 1999-2014 were examined to determine obesity in children aged 2-19 years. A combination of body mass index (BMI) and “a percentage of the 95th percentile” of weight across three age groups – 2-5 years, 6-11 years, and 12-19 years – was used to classify children with class I, class II, or class III (severe) obesity.

Dr. Skinner did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT THE PAS ANNUAL MEETING

Paperwork snarls stand between kids and at-school asthma medications

BALTIMORE – Four out of five children with asthma didn’t have access to their medication at school because the proper paperwork was missing, according to a survey of 10 inner-city Milwaukee elementary schools.

The number of students who had the required physician-signed authorization forms remained low throughout the school year, said Dr. Santiago Encalada, a pulmonary fellow at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

Dr. Encalada cited administrative hurdles, lack of standardization, and challenges in school-physician-family communication as barriers to children’s access to asthma medication at school. Although school nurses in Milwaukee have standing orders for emergency albuterol administration, they otherwise need physician signatures on school-generated forms to administer both rescue and prophylactic asthma administration.

In a study whose purpose was to assess the percentage of children with asthma who had appropriate orders on file in a sample of 10 Milwaukee inner-city schools, the schools had orders on file for just 11% of students, on average, at the beginning of the 2014-2015 school year. At the second assessment in January 2015, the average number of students with orders on file at each school had risen to 22%, with schools that had performed better earlier also showing greater gains at mid-year. However, the June 2015 assessment showed that the gains did not continue, with the schools’ aggregate average of 21% of students with appropriate orders showing no improvement from mid-year.

The number of students with asthma in schools varied from about 40 to nearly 200. Numbers varied through the school year as enrollments shifted in these high-need schools, said Dr. Encalada, who presented his findings during a poster session at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies. In general, the schools with lower enrollments tended to do better with having orders on file, although statistical analysis was not performed for this variable.

“On average, 80% of asthmatic students in the inner city schools we studied did not have school forms or orders available for life-saving asthma rescue medications, with significant variation between schools. Our findings show that access to even basic asthma care necessities are lagging for this vulnerable population, and a significant disparity exists even within this population,” said senior author Nicholas Antos*, associate director of the Cystic Fibrosis Center at Milwaukee’s Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin.

In interviews and discussion with school nurses and physicians’ offices, Dr. Antos* and Dr. Encalada found that there were often simple but fundamental misunderstandings that impeded the proper flow of paperwork. For example, schools in Milwaukee do not have standardized forms that authorize administration of prescription medications at school, so forms may be confusing to providers and their staff. Privacy concerns sometimes impeded the ability of clinic staff to authorize treatment for students. Also, the inevitable shuffle of paperwork in school-aged families meant that the forms sometimes were simply lost on the way to school.

Understanding the barriers in the process both on the school side and in physician offices has helped Dr. Antos*, Dr. Encalada, and their colleagues to start to build a better pathway. For example, a module has been built into the EHR asthma visit template that allows easy generation of a school form and asks for patient consent for release of information to the schools.

Dr. Antos* said in an interview that the work is ongoing: “To help address these problems, we have devised interventions to improve the way school nurses can contact clinicians, and helped design innovative standardized Asthma Action Plans that can double as school orders.”

In addition to working with local providers and schools, Dr. Encalada and Dr. Antos* have reached out to pediatric societies and the American Academy of Asthma, Allergy, and Immunology (AAAAI). Emphasizing the need for “education of stakeholders of all types,” Dr. Antos* said that change “may be difficult, but we hope with the support of pediatric organizations, the AAAAI, and school administrators, we can begin to break down the barriers preventing quality and timely communication with school nurses.”

The authors had no financial disclosures. The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention through the Wisconsin Asthma Coalition (WAC).

On Twitter @karioakes

*In a previous version, Dr. Antos' name was misspelled.

Dr. Susan Millard, FCCP: comments: The issues identified in this article are huge and not just an occurrence in the inner cities. The critical problem is that the children are even more at risk when living in the inner cities and for sudden death due to asthma. Having one form for the whole state would help tremendously because we could print out an asthma action plan and the form for the school and then fax it directly!

Dr. Susan Millard, FCCP: comments: The issues identified in this article are huge and not just an occurrence in the inner cities. The critical problem is that the children are even more at risk when living in the inner cities and for sudden death due to asthma. Having one form for the whole state would help tremendously because we could print out an asthma action plan and the form for the school and then fax it directly!

Dr. Susan Millard, FCCP: comments: The issues identified in this article are huge and not just an occurrence in the inner cities. The critical problem is that the children are even more at risk when living in the inner cities and for sudden death due to asthma. Having one form for the whole state would help tremendously because we could print out an asthma action plan and the form for the school and then fax it directly!

BALTIMORE – Four out of five children with asthma didn’t have access to their medication at school because the proper paperwork was missing, according to a survey of 10 inner-city Milwaukee elementary schools.

The number of students who had the required physician-signed authorization forms remained low throughout the school year, said Dr. Santiago Encalada, a pulmonary fellow at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

Dr. Encalada cited administrative hurdles, lack of standardization, and challenges in school-physician-family communication as barriers to children’s access to asthma medication at school. Although school nurses in Milwaukee have standing orders for emergency albuterol administration, they otherwise need physician signatures on school-generated forms to administer both rescue and prophylactic asthma administration.

In a study whose purpose was to assess the percentage of children with asthma who had appropriate orders on file in a sample of 10 Milwaukee inner-city schools, the schools had orders on file for just 11% of students, on average, at the beginning of the 2014-2015 school year. At the second assessment in January 2015, the average number of students with orders on file at each school had risen to 22%, with schools that had performed better earlier also showing greater gains at mid-year. However, the June 2015 assessment showed that the gains did not continue, with the schools’ aggregate average of 21% of students with appropriate orders showing no improvement from mid-year.

The number of students with asthma in schools varied from about 40 to nearly 200. Numbers varied through the school year as enrollments shifted in these high-need schools, said Dr. Encalada, who presented his findings during a poster session at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies. In general, the schools with lower enrollments tended to do better with having orders on file, although statistical analysis was not performed for this variable.

“On average, 80% of asthmatic students in the inner city schools we studied did not have school forms or orders available for life-saving asthma rescue medications, with significant variation between schools. Our findings show that access to even basic asthma care necessities are lagging for this vulnerable population, and a significant disparity exists even within this population,” said senior author Nicholas Antos*, associate director of the Cystic Fibrosis Center at Milwaukee’s Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin.

In interviews and discussion with school nurses and physicians’ offices, Dr. Antos* and Dr. Encalada found that there were often simple but fundamental misunderstandings that impeded the proper flow of paperwork. For example, schools in Milwaukee do not have standardized forms that authorize administration of prescription medications at school, so forms may be confusing to providers and their staff. Privacy concerns sometimes impeded the ability of clinic staff to authorize treatment for students. Also, the inevitable shuffle of paperwork in school-aged families meant that the forms sometimes were simply lost on the way to school.

Understanding the barriers in the process both on the school side and in physician offices has helped Dr. Antos*, Dr. Encalada, and their colleagues to start to build a better pathway. For example, a module has been built into the EHR asthma visit template that allows easy generation of a school form and asks for patient consent for release of information to the schools.

Dr. Antos* said in an interview that the work is ongoing: “To help address these problems, we have devised interventions to improve the way school nurses can contact clinicians, and helped design innovative standardized Asthma Action Plans that can double as school orders.”

In addition to working with local providers and schools, Dr. Encalada and Dr. Antos* have reached out to pediatric societies and the American Academy of Asthma, Allergy, and Immunology (AAAAI). Emphasizing the need for “education of stakeholders of all types,” Dr. Antos* said that change “may be difficult, but we hope with the support of pediatric organizations, the AAAAI, and school administrators, we can begin to break down the barriers preventing quality and timely communication with school nurses.”

The authors had no financial disclosures. The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention through the Wisconsin Asthma Coalition (WAC).

On Twitter @karioakes

*In a previous version, Dr. Antos' name was misspelled.

BALTIMORE – Four out of five children with asthma didn’t have access to their medication at school because the proper paperwork was missing, according to a survey of 10 inner-city Milwaukee elementary schools.

The number of students who had the required physician-signed authorization forms remained low throughout the school year, said Dr. Santiago Encalada, a pulmonary fellow at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

Dr. Encalada cited administrative hurdles, lack of standardization, and challenges in school-physician-family communication as barriers to children’s access to asthma medication at school. Although school nurses in Milwaukee have standing orders for emergency albuterol administration, they otherwise need physician signatures on school-generated forms to administer both rescue and prophylactic asthma administration.

In a study whose purpose was to assess the percentage of children with asthma who had appropriate orders on file in a sample of 10 Milwaukee inner-city schools, the schools had orders on file for just 11% of students, on average, at the beginning of the 2014-2015 school year. At the second assessment in January 2015, the average number of students with orders on file at each school had risen to 22%, with schools that had performed better earlier also showing greater gains at mid-year. However, the June 2015 assessment showed that the gains did not continue, with the schools’ aggregate average of 21% of students with appropriate orders showing no improvement from mid-year.

The number of students with asthma in schools varied from about 40 to nearly 200. Numbers varied through the school year as enrollments shifted in these high-need schools, said Dr. Encalada, who presented his findings during a poster session at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies. In general, the schools with lower enrollments tended to do better with having orders on file, although statistical analysis was not performed for this variable.

“On average, 80% of asthmatic students in the inner city schools we studied did not have school forms or orders available for life-saving asthma rescue medications, with significant variation between schools. Our findings show that access to even basic asthma care necessities are lagging for this vulnerable population, and a significant disparity exists even within this population,” said senior author Nicholas Antos*, associate director of the Cystic Fibrosis Center at Milwaukee’s Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin.

In interviews and discussion with school nurses and physicians’ offices, Dr. Antos* and Dr. Encalada found that there were often simple but fundamental misunderstandings that impeded the proper flow of paperwork. For example, schools in Milwaukee do not have standardized forms that authorize administration of prescription medications at school, so forms may be confusing to providers and their staff. Privacy concerns sometimes impeded the ability of clinic staff to authorize treatment for students. Also, the inevitable shuffle of paperwork in school-aged families meant that the forms sometimes were simply lost on the way to school.

Understanding the barriers in the process both on the school side and in physician offices has helped Dr. Antos*, Dr. Encalada, and their colleagues to start to build a better pathway. For example, a module has been built into the EHR asthma visit template that allows easy generation of a school form and asks for patient consent for release of information to the schools.

Dr. Antos* said in an interview that the work is ongoing: “To help address these problems, we have devised interventions to improve the way school nurses can contact clinicians, and helped design innovative standardized Asthma Action Plans that can double as school orders.”

In addition to working with local providers and schools, Dr. Encalada and Dr. Antos* have reached out to pediatric societies and the American Academy of Asthma, Allergy, and Immunology (AAAAI). Emphasizing the need for “education of stakeholders of all types,” Dr. Antos* said that change “may be difficult, but we hope with the support of pediatric organizations, the AAAAI, and school administrators, we can begin to break down the barriers preventing quality and timely communication with school nurses.”

The authors had no financial disclosures. The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention through the Wisconsin Asthma Coalition (WAC).

On Twitter @karioakes

*In a previous version, Dr. Antos' name was misspelled.

AT THE PAS ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Four out of five high-risk elementary school children lacked proper orders for at-school asthma medication administration.

Major finding: The average number of elementary school children with asthma medication orders on file was 21% at year’s end.

Data source: Yearlong study of 10 inner-city Milwaukee elementary schools; enrollees with asthma ranged from about 40 to nearly 200.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention through the Wisconsin Asthma Coalition (WAC).

VIDEO: Comanagement effective at treating mental health issues in pediatric patients

BALTIMORE – For pediatric group practices to move toward comanagement to more effectively treat any mental health issues their patients may exhibit, the first step is to educate pediatricians about the benefits of comanagement, according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

“Pediatricians who had had at least 4 weeks of developmental behavioral pediatrics – or had targeted training on treatment for ADHD, anxiety, depression, behavioral problems – were more likely to comanage at least 50% of their patients” with mental health disorders, explained Dr. Cori Green of Cornell University, New York.

In a video interview, Dr. Green discussed the findings of her study, which consisted of 305 group practices in the 2013 American Academy of Pediatrics Periodic Survey, and the importance of education in teaching residents, trainees, and fellows about comanagement.

Dr. Green did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

BALTIMORE – For pediatric group practices to move toward comanagement to more effectively treat any mental health issues their patients may exhibit, the first step is to educate pediatricians about the benefits of comanagement, according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

“Pediatricians who had had at least 4 weeks of developmental behavioral pediatrics – or had targeted training on treatment for ADHD, anxiety, depression, behavioral problems – were more likely to comanage at least 50% of their patients” with mental health disorders, explained Dr. Cori Green of Cornell University, New York.

In a video interview, Dr. Green discussed the findings of her study, which consisted of 305 group practices in the 2013 American Academy of Pediatrics Periodic Survey, and the importance of education in teaching residents, trainees, and fellows about comanagement.

Dr. Green did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

BALTIMORE – For pediatric group practices to move toward comanagement to more effectively treat any mental health issues their patients may exhibit, the first step is to educate pediatricians about the benefits of comanagement, according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

“Pediatricians who had had at least 4 weeks of developmental behavioral pediatrics – or had targeted training on treatment for ADHD, anxiety, depression, behavioral problems – were more likely to comanage at least 50% of their patients” with mental health disorders, explained Dr. Cori Green of Cornell University, New York.

In a video interview, Dr. Green discussed the findings of her study, which consisted of 305 group practices in the 2013 American Academy of Pediatrics Periodic Survey, and the importance of education in teaching residents, trainees, and fellows about comanagement.

Dr. Green did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT THE PAS ANNUAL MEETING

Children with internalizing symptoms may not get enough attention

BALTIMORE – Children who exhibit only internalizing symptoms, which are often indicative of anxiety and depression, are less likely to be referred to mental health services than children who exhibit not only the same internalizing behavior, but also external and attentional behavior.

“Pediatricians now are doing much more about mental health; we’ve been energized about how this is an important determinant not only of the child’s present health, but the child’s long-term health, and how they function in the world,” explained Dr. Diane Bloomfield of The Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, Bronx, N.Y., at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

In a video interview, Dr. Bloomfield discussed the importance of making sure children with internalizing symptoms are referred to the proper specialists, how electronic health records can play a part in children slipping through the cracks, and why educating parents is a critical step in addressing the needs of internalizing children.

Dr. Bloomfield did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

BALTIMORE – Children who exhibit only internalizing symptoms, which are often indicative of anxiety and depression, are less likely to be referred to mental health services than children who exhibit not only the same internalizing behavior, but also external and attentional behavior.

“Pediatricians now are doing much more about mental health; we’ve been energized about how this is an important determinant not only of the child’s present health, but the child’s long-term health, and how they function in the world,” explained Dr. Diane Bloomfield of The Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, Bronx, N.Y., at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

In a video interview, Dr. Bloomfield discussed the importance of making sure children with internalizing symptoms are referred to the proper specialists, how electronic health records can play a part in children slipping through the cracks, and why educating parents is a critical step in addressing the needs of internalizing children.

Dr. Bloomfield did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

BALTIMORE – Children who exhibit only internalizing symptoms, which are often indicative of anxiety and depression, are less likely to be referred to mental health services than children who exhibit not only the same internalizing behavior, but also external and attentional behavior.

“Pediatricians now are doing much more about mental health; we’ve been energized about how this is an important determinant not only of the child’s present health, but the child’s long-term health, and how they function in the world,” explained Dr. Diane Bloomfield of The Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, Bronx, N.Y., at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

In a video interview, Dr. Bloomfield discussed the importance of making sure children with internalizing symptoms are referred to the proper specialists, how electronic health records can play a part in children slipping through the cracks, and why educating parents is a critical step in addressing the needs of internalizing children.

Dr. Bloomfield did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT THE PAS ANNUAL MEETING

Acid blockers boost infections in outpatient preemies

BALTIMORE – Treatment of premature infants with a drug that blocks gastroesophageal reflux once they are discharged home during the first year of life was associated with a significantly increased risk for development of pneumonia and gastroenteritis in a case-control study with 695 matched-pairs of infants.

Administering either a histamine2-receptor antagonist or proton pump inhibitor to these children was associated with an adjusted 75% increased risk for pneumonia and a 2.4-fold increased risk for gastroenteritis during the periods when the infants were on these acid-blocking drugs, Dr. Scott A. Lorch said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies. However, these medications did not appear to produce any lingering effects, with the rates of these infections falling to match control rates after acid-blocking treatment ceased.

The findings highlight that acid-blocking drugs “are not without consequences” and so should be “carefully considered before initiating therapy in this medically fragile population [premature infants], and if they are prescribed their continued need should be frequently assessed,” said Dr. Lorch, a neonatologist at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

In his experience, acid blockers “are being used like water, both in the hospital as well as after the infants go home. That is where there is concern. We see a fair number of kids on these medications for a much longer period of time than you’d expect. The average time on these medications is 6 months, and that is a long time to be on them,” Dr. Lorch said.

He noted that study results reported in 2015 by himself and his associates showed that in the 30-site primary care network affiliated with the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, three-quarters of the acid-blocking drug prescriptions written for infants who had been born prematurely came from primary care physicians once the infants had been discharged from the hospital.

The current study used data that had been collected on more than 2,000 infants who had been born at less than 36 weeks’ gestation during 2007-2009 and then discharged within 4 months of delivery into care by the primary care network and then followed until they were 3 years old. From this cohort, the researchers identified 695 infants who began treatment with either a histamine2-receptor antagonist or a proton pump inhibitor at some time during their first year and matched them by gestational age at birth and race with an equal number of infants from the cohort who never received an acid-blocking drug.

Dr. Lorch and his associates then analyzed the incidence rates of four different types of infections in the children during three time periods: while they were on the acid-blocking medication, and at 7 months and 13 months after the acid-blocking treatment stopped. Infection rates in the controls were tallied at ages that matched the periods studied in those who received the acid blockers.

The four infections they studied were pneumonia, gastroenteritis, bronchiolitis, and conjunctivitis. The last was included as a control as the researchers presumed that acid-blocker use should have no impact on the rates of conjunctivitis.

The results showed that during acid-blocker treatment, the incidence rate of pneumonia was 5% in those on an acid blocker and 3% in the controls, and the incidence of gastroenteritis was 19% in those on an acid blocker and 12% in the controls, Dr. Lorch reported. However, the rates of both infections were similar at 7 and 13 months after acid-blocker treatment stopped, and there was also no difference in the rates of both bronchiolitis and conjunctivitis during any period examined.

A multivariate analysis that controlled for a variety of clinical and demographic variables determined the 75% increased odds ratio for pneumonia and the 2.4-fold increased rate of gastroenteritis, compared with the controls, during periods of acid-blocker treatment. The analysis also showed that the presence of chronic lung disease appeared to have no impact on these infection rates.

Dr. Lorch had no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BALTIMORE – Treatment of premature infants with a drug that blocks gastroesophageal reflux once they are discharged home during the first year of life was associated with a significantly increased risk for development of pneumonia and gastroenteritis in a case-control study with 695 matched-pairs of infants.

Administering either a histamine2-receptor antagonist or proton pump inhibitor to these children was associated with an adjusted 75% increased risk for pneumonia and a 2.4-fold increased risk for gastroenteritis during the periods when the infants were on these acid-blocking drugs, Dr. Scott A. Lorch said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies. However, these medications did not appear to produce any lingering effects, with the rates of these infections falling to match control rates after acid-blocking treatment ceased.

The findings highlight that acid-blocking drugs “are not without consequences” and so should be “carefully considered before initiating therapy in this medically fragile population [premature infants], and if they are prescribed their continued need should be frequently assessed,” said Dr. Lorch, a neonatologist at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

In his experience, acid blockers “are being used like water, both in the hospital as well as after the infants go home. That is where there is concern. We see a fair number of kids on these medications for a much longer period of time than you’d expect. The average time on these medications is 6 months, and that is a long time to be on them,” Dr. Lorch said.

He noted that study results reported in 2015 by himself and his associates showed that in the 30-site primary care network affiliated with the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, three-quarters of the acid-blocking drug prescriptions written for infants who had been born prematurely came from primary care physicians once the infants had been discharged from the hospital.

The current study used data that had been collected on more than 2,000 infants who had been born at less than 36 weeks’ gestation during 2007-2009 and then discharged within 4 months of delivery into care by the primary care network and then followed until they were 3 years old. From this cohort, the researchers identified 695 infants who began treatment with either a histamine2-receptor antagonist or a proton pump inhibitor at some time during their first year and matched them by gestational age at birth and race with an equal number of infants from the cohort who never received an acid-blocking drug.

Dr. Lorch and his associates then analyzed the incidence rates of four different types of infections in the children during three time periods: while they were on the acid-blocking medication, and at 7 months and 13 months after the acid-blocking treatment stopped. Infection rates in the controls were tallied at ages that matched the periods studied in those who received the acid blockers.

The four infections they studied were pneumonia, gastroenteritis, bronchiolitis, and conjunctivitis. The last was included as a control as the researchers presumed that acid-blocker use should have no impact on the rates of conjunctivitis.

The results showed that during acid-blocker treatment, the incidence rate of pneumonia was 5% in those on an acid blocker and 3% in the controls, and the incidence of gastroenteritis was 19% in those on an acid blocker and 12% in the controls, Dr. Lorch reported. However, the rates of both infections were similar at 7 and 13 months after acid-blocker treatment stopped, and there was also no difference in the rates of both bronchiolitis and conjunctivitis during any period examined.

A multivariate analysis that controlled for a variety of clinical and demographic variables determined the 75% increased odds ratio for pneumonia and the 2.4-fold increased rate of gastroenteritis, compared with the controls, during periods of acid-blocker treatment. The analysis also showed that the presence of chronic lung disease appeared to have no impact on these infection rates.

Dr. Lorch had no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BALTIMORE – Treatment of premature infants with a drug that blocks gastroesophageal reflux once they are discharged home during the first year of life was associated with a significantly increased risk for development of pneumonia and gastroenteritis in a case-control study with 695 matched-pairs of infants.

Administering either a histamine2-receptor antagonist or proton pump inhibitor to these children was associated with an adjusted 75% increased risk for pneumonia and a 2.4-fold increased risk for gastroenteritis during the periods when the infants were on these acid-blocking drugs, Dr. Scott A. Lorch said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies. However, these medications did not appear to produce any lingering effects, with the rates of these infections falling to match control rates after acid-blocking treatment ceased.

The findings highlight that acid-blocking drugs “are not without consequences” and so should be “carefully considered before initiating therapy in this medically fragile population [premature infants], and if they are prescribed their continued need should be frequently assessed,” said Dr. Lorch, a neonatologist at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

In his experience, acid blockers “are being used like water, both in the hospital as well as after the infants go home. That is where there is concern. We see a fair number of kids on these medications for a much longer period of time than you’d expect. The average time on these medications is 6 months, and that is a long time to be on them,” Dr. Lorch said.

He noted that study results reported in 2015 by himself and his associates showed that in the 30-site primary care network affiliated with the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, three-quarters of the acid-blocking drug prescriptions written for infants who had been born prematurely came from primary care physicians once the infants had been discharged from the hospital.

The current study used data that had been collected on more than 2,000 infants who had been born at less than 36 weeks’ gestation during 2007-2009 and then discharged within 4 months of delivery into care by the primary care network and then followed until they were 3 years old. From this cohort, the researchers identified 695 infants who began treatment with either a histamine2-receptor antagonist or a proton pump inhibitor at some time during their first year and matched them by gestational age at birth and race with an equal number of infants from the cohort who never received an acid-blocking drug.

Dr. Lorch and his associates then analyzed the incidence rates of four different types of infections in the children during three time periods: while they were on the acid-blocking medication, and at 7 months and 13 months after the acid-blocking treatment stopped. Infection rates in the controls were tallied at ages that matched the periods studied in those who received the acid blockers.

The four infections they studied were pneumonia, gastroenteritis, bronchiolitis, and conjunctivitis. The last was included as a control as the researchers presumed that acid-blocker use should have no impact on the rates of conjunctivitis.

The results showed that during acid-blocker treatment, the incidence rate of pneumonia was 5% in those on an acid blocker and 3% in the controls, and the incidence of gastroenteritis was 19% in those on an acid blocker and 12% in the controls, Dr. Lorch reported. However, the rates of both infections were similar at 7 and 13 months after acid-blocker treatment stopped, and there was also no difference in the rates of both bronchiolitis and conjunctivitis during any period examined.

A multivariate analysis that controlled for a variety of clinical and demographic variables determined the 75% increased odds ratio for pneumonia and the 2.4-fold increased rate of gastroenteritis, compared with the controls, during periods of acid-blocker treatment. The analysis also showed that the presence of chronic lung disease appeared to have no impact on these infection rates.

Dr. Lorch had no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE PAS ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Premature infants who were discharged home and then received a drug to prevent gastroesophageal reflux during their first year had significantly increased rates of pneumonia and gastroenteritis during the periods when they were on the acid-blocking drugs.

Major finding: Treatment with an acid-blocking drug was associated with a 75% increased rate of pneumonia and a 2.4-fold higher rate of gastroenteritis.

Data source: Case-control study involving 695 matched pairs of infants from a single U.S. primary care network.

Disclosures: Dr. Lorch had no relevant financial disclosures.

Vitamin D Supplementation Cuts Dust Mite Atopy

BALTIMORE – Three months of daily, oral treatment with a relatively high but safe dosage of a vitamin D supplement to pregnant mothers during late gestation followed by continued oral supplementation to their neonates during the first 6 months of life led to a significant reduction in the prevalence of dust-mite skin reactivity in those children once they reached 18 months old in a randomized, controlled trial with 259 mothers and infants.

And in a preliminary assessment that tallied the number of children who required primary care office visits for asthma through age 18 months, children who had received the highest vitamin D supplementation also showed a statistically significant reduction of these visits, compared with the placebo control children, Dr. Cameron C. Grant reported at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

This suggestion that the vitamin D intervention could cut asthma development is not completely certain because in 18-month-old children, diagnosis of asthma is “very insecure,” noted Dr. Grant, a pediatrician at the University of Auckland, New Zealand and at Starship Children’s Hospital, also in Auckland. In addition, a limitation of the observed effect on dust mite atopy on skin-test challenge was that this follow-up occurred in only 186 (72%) of the 259 infants who participated in the study.

The study’s premise was that vitamin D is an immune system modulator, and that New Zealand provides an excellent setting to test the hypothesis that normalized vitamin D levels can help prevent development of atopy and asthma because many of the country’s residents are vitamin D deficient due to their diet and sun avoidance to prevent skin cancers. Results from prior studies had shown that 57% of New Zealand neonates have inadequate levels of vitamin D at birth, defined as a serum level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D of less than 20 ng/ml (less than 50 nmol/L), Dr. Grant noted.

“I think this intervention will only work in populations that are vitamin D deficient,” Dr. Grant said in an interview. In his study, the average serum level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D among control neonates was 38 nmol/L (about 15 ng/mL). In contrast, neonates born to mothers who had received a daily, higher-dose vitamin D supplement during the third trimester had serum measures that were roughly twice that level.

The study enrolled 260 pregnant women from the Auckland area with a single pregnancy at 26-30 weeks’ gestation; average gestational age at baseline was 27 weeks. Dr. Grant and his associates randomized the mothers to receive 1,000 IU oral vitamin D daily, 2,000 oral vitamin D daily, or placebo. The women delivered 259 infants. Infants born to women on the lower dosage supplement then received 400 IU vitamin daily for 6 months, those born to mothers on the higher level supplement received 800 IU vitamin D daily for 6 months, and those born to mothers in the placebo group received placebo supplements daily for 6 months.

Both supplement regimens led to statistically significant increases in serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in maternal serum at 36 weeks’ gestation, in cord blood at delivery, in the neonates’ serum at ages 2 months and 4 months, and in infant serum in the higher dosage group at 6 months of age, compared with similar measures taken at all these time points in the placebo group.

In addition, the neonates in the higher dosage group had significantly higher serum levels at 2, 4, and 6 months, compared with the lower dosage group. When measured a final time at 18-month follow-up, a year after the end of vitamin D supplementation, average serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in an three subgroups of children were virtually identical and similar to maternal serum levels at baseline. Dr. Grant and his associates had previously reported these findings and also had documented the safety of both the low and high levels of vitamin D supplements for both mothers and their children (Pediatrics. 2014 Jan;133[1]:e143-53).

The new findings reported by Dr. Grant focused on clinical outcomes at 18 months. He and his colleagues ran skin-prick testing on 186 of the 259 (72%) children in the study (the remaining children weren’t available for this follow-up assessment). They tested three aeroallergens: cat, pollen, and house dust mite. They saw no significant differences in the prevalence of positive skin-prick reactions among the three study groups to cat and pollen, but prevalence levels of positive reactions to dust mite were 9% in the controls, 3% of children in the low-dosage group, and none in the high dosage group. The difference between the controls and high dosage groups was statistically significant; the difference between the controls and the low dosage group was not significant, Dr. Grant said. Additional testing of specific IgE responses to four different dust mite antigens showed statistically significant reductions in responses to each of the four antigens among the high dosage children, compared with the controls and with the low dosage children.

The researchers also tallied the number of acute, primary care office visits during the first 18 months of life among the children in each of the three subgroups for a variety of respiratory diagnoses. The three groups showed no significant differences in total number of office visits for most of these diagnoses, including colds, otitis media, croup, and bronchitis. However, about 12% of children in the control group had been seen in a primary care office for a diagnosis of asthma, compared with none of the children in the low dosage group and about 4% in the high-dosage group. The differences between the two intervention groups and the control group were statistically significant. Dr. Grant cautioned that this finding is very preliminary and that any conclusions about the impact of vitamin D supplements on asthma incidence must await studies with larger numbers of children who are followed to an older age.

Dr. Grant had no disclosures.

BALTIMORE – Three months of daily, oral treatment with a relatively high but safe dosage of a vitamin D supplement to pregnant mothers during late gestation followed by continued oral supplementation to their neonates during the first 6 months of life led to a significant reduction in the prevalence of dust-mite skin reactivity in those children once they reached 18 months old in a randomized, controlled trial with 259 mothers and infants.

And in a preliminary assessment that tallied the number of children who required primary care office visits for asthma through age 18 months, children who had received the highest vitamin D supplementation also showed a statistically significant reduction of these visits, compared with the placebo control children, Dr. Cameron C. Grant reported at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

This suggestion that the vitamin D intervention could cut asthma development is not completely certain because in 18-month-old children, diagnosis of asthma is “very insecure,” noted Dr. Grant, a pediatrician at the University of Auckland, New Zealand and at Starship Children’s Hospital, also in Auckland. In addition, a limitation of the observed effect on dust mite atopy on skin-test challenge was that this follow-up occurred in only 186 (72%) of the 259 infants who participated in the study.

The study’s premise was that vitamin D is an immune system modulator, and that New Zealand provides an excellent setting to test the hypothesis that normalized vitamin D levels can help prevent development of atopy and asthma because many of the country’s residents are vitamin D deficient due to their diet and sun avoidance to prevent skin cancers. Results from prior studies had shown that 57% of New Zealand neonates have inadequate levels of vitamin D at birth, defined as a serum level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D of less than 20 ng/ml (less than 50 nmol/L), Dr. Grant noted.

“I think this intervention will only work in populations that are vitamin D deficient,” Dr. Grant said in an interview. In his study, the average serum level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D among control neonates was 38 nmol/L (about 15 ng/mL). In contrast, neonates born to mothers who had received a daily, higher-dose vitamin D supplement during the third trimester had serum measures that were roughly twice that level.

The study enrolled 260 pregnant women from the Auckland area with a single pregnancy at 26-30 weeks’ gestation; average gestational age at baseline was 27 weeks. Dr. Grant and his associates randomized the mothers to receive 1,000 IU oral vitamin D daily, 2,000 oral vitamin D daily, or placebo. The women delivered 259 infants. Infants born to women on the lower dosage supplement then received 400 IU vitamin daily for 6 months, those born to mothers on the higher level supplement received 800 IU vitamin D daily for 6 months, and those born to mothers in the placebo group received placebo supplements daily for 6 months.

Both supplement regimens led to statistically significant increases in serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in maternal serum at 36 weeks’ gestation, in cord blood at delivery, in the neonates’ serum at ages 2 months and 4 months, and in infant serum in the higher dosage group at 6 months of age, compared with similar measures taken at all these time points in the placebo group.

In addition, the neonates in the higher dosage group had significantly higher serum levels at 2, 4, and 6 months, compared with the lower dosage group. When measured a final time at 18-month follow-up, a year after the end of vitamin D supplementation, average serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in an three subgroups of children were virtually identical and similar to maternal serum levels at baseline. Dr. Grant and his associates had previously reported these findings and also had documented the safety of both the low and high levels of vitamin D supplements for both mothers and their children (Pediatrics. 2014 Jan;133[1]:e143-53).

The new findings reported by Dr. Grant focused on clinical outcomes at 18 months. He and his colleagues ran skin-prick testing on 186 of the 259 (72%) children in the study (the remaining children weren’t available for this follow-up assessment). They tested three aeroallergens: cat, pollen, and house dust mite. They saw no significant differences in the prevalence of positive skin-prick reactions among the three study groups to cat and pollen, but prevalence levels of positive reactions to dust mite were 9% in the controls, 3% of children in the low-dosage group, and none in the high dosage group. The difference between the controls and high dosage groups was statistically significant; the difference between the controls and the low dosage group was not significant, Dr. Grant said. Additional testing of specific IgE responses to four different dust mite antigens showed statistically significant reductions in responses to each of the four antigens among the high dosage children, compared with the controls and with the low dosage children.

The researchers also tallied the number of acute, primary care office visits during the first 18 months of life among the children in each of the three subgroups for a variety of respiratory diagnoses. The three groups showed no significant differences in total number of office visits for most of these diagnoses, including colds, otitis media, croup, and bronchitis. However, about 12% of children in the control group had been seen in a primary care office for a diagnosis of asthma, compared with none of the children in the low dosage group and about 4% in the high-dosage group. The differences between the two intervention groups and the control group were statistically significant. Dr. Grant cautioned that this finding is very preliminary and that any conclusions about the impact of vitamin D supplements on asthma incidence must await studies with larger numbers of children who are followed to an older age.

Dr. Grant had no disclosures.

BALTIMORE – Three months of daily, oral treatment with a relatively high but safe dosage of a vitamin D supplement to pregnant mothers during late gestation followed by continued oral supplementation to their neonates during the first 6 months of life led to a significant reduction in the prevalence of dust-mite skin reactivity in those children once they reached 18 months old in a randomized, controlled trial with 259 mothers and infants.

And in a preliminary assessment that tallied the number of children who required primary care office visits for asthma through age 18 months, children who had received the highest vitamin D supplementation also showed a statistically significant reduction of these visits, compared with the placebo control children, Dr. Cameron C. Grant reported at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

This suggestion that the vitamin D intervention could cut asthma development is not completely certain because in 18-month-old children, diagnosis of asthma is “very insecure,” noted Dr. Grant, a pediatrician at the University of Auckland, New Zealand and at Starship Children’s Hospital, also in Auckland. In addition, a limitation of the observed effect on dust mite atopy on skin-test challenge was that this follow-up occurred in only 186 (72%) of the 259 infants who participated in the study.

The study’s premise was that vitamin D is an immune system modulator, and that New Zealand provides an excellent setting to test the hypothesis that normalized vitamin D levels can help prevent development of atopy and asthma because many of the country’s residents are vitamin D deficient due to their diet and sun avoidance to prevent skin cancers. Results from prior studies had shown that 57% of New Zealand neonates have inadequate levels of vitamin D at birth, defined as a serum level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D of less than 20 ng/ml (less than 50 nmol/L), Dr. Grant noted.

“I think this intervention will only work in populations that are vitamin D deficient,” Dr. Grant said in an interview. In his study, the average serum level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D among control neonates was 38 nmol/L (about 15 ng/mL). In contrast, neonates born to mothers who had received a daily, higher-dose vitamin D supplement during the third trimester had serum measures that were roughly twice that level.

The study enrolled 260 pregnant women from the Auckland area with a single pregnancy at 26-30 weeks’ gestation; average gestational age at baseline was 27 weeks. Dr. Grant and his associates randomized the mothers to receive 1,000 IU oral vitamin D daily, 2,000 oral vitamin D daily, or placebo. The women delivered 259 infants. Infants born to women on the lower dosage supplement then received 400 IU vitamin daily for 6 months, those born to mothers on the higher level supplement received 800 IU vitamin D daily for 6 months, and those born to mothers in the placebo group received placebo supplements daily for 6 months.

Both supplement regimens led to statistically significant increases in serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in maternal serum at 36 weeks’ gestation, in cord blood at delivery, in the neonates’ serum at ages 2 months and 4 months, and in infant serum in the higher dosage group at 6 months of age, compared with similar measures taken at all these time points in the placebo group.

In addition, the neonates in the higher dosage group had significantly higher serum levels at 2, 4, and 6 months, compared with the lower dosage group. When measured a final time at 18-month follow-up, a year after the end of vitamin D supplementation, average serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in an three subgroups of children were virtually identical and similar to maternal serum levels at baseline. Dr. Grant and his associates had previously reported these findings and also had documented the safety of both the low and high levels of vitamin D supplements for both mothers and their children (Pediatrics. 2014 Jan;133[1]:e143-53).

The new findings reported by Dr. Grant focused on clinical outcomes at 18 months. He and his colleagues ran skin-prick testing on 186 of the 259 (72%) children in the study (the remaining children weren’t available for this follow-up assessment). They tested three aeroallergens: cat, pollen, and house dust mite. They saw no significant differences in the prevalence of positive skin-prick reactions among the three study groups to cat and pollen, but prevalence levels of positive reactions to dust mite were 9% in the controls, 3% of children in the low-dosage group, and none in the high dosage group. The difference between the controls and high dosage groups was statistically significant; the difference between the controls and the low dosage group was not significant, Dr. Grant said. Additional testing of specific IgE responses to four different dust mite antigens showed statistically significant reductions in responses to each of the four antigens among the high dosage children, compared with the controls and with the low dosage children.

The researchers also tallied the number of acute, primary care office visits during the first 18 months of life among the children in each of the three subgroups for a variety of respiratory diagnoses. The three groups showed no significant differences in total number of office visits for most of these diagnoses, including colds, otitis media, croup, and bronchitis. However, about 12% of children in the control group had been seen in a primary care office for a diagnosis of asthma, compared with none of the children in the low dosage group and about 4% in the high-dosage group. The differences between the two intervention groups and the control group were statistically significant. Dr. Grant cautioned that this finding is very preliminary and that any conclusions about the impact of vitamin D supplements on asthma incidence must await studies with larger numbers of children who are followed to an older age.

Dr. Grant had no disclosures.

AT THE PAS ANNUAL MEETING

Vitamin D supplementation cuts dust mite atopy

BALTIMORE – Three months of daily, oral treatment with a relatively high but safe dosage of a vitamin D supplement to pregnant mothers during late gestation followed by continued oral supplementation to their neonates during the first 6 months of life led to a significant reduction in the prevalence of dust-mite skin reactivity in those children once they reached 18 months old in a randomized, controlled trial with 259 mothers and infants.

And in a preliminary assessment that tallied the number of children who required primary care office visits for asthma through age 18 months, children who had received the highest vitamin D supplementation also showed a statistically significant reduction of these visits, compared with the placebo control children, Dr. Cameron C. Grant reported at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

This suggestion that the vitamin D intervention could cut asthma development is not completely certain because in 18-month-old children, diagnosis of asthma is “very insecure,” noted Dr. Grant, a pediatrician at the University of Auckland, New Zealand and at Starship Children’s Hospital, also in Auckland. In addition, a limitation of the observed effect on dust mite atopy on skin-test challenge was that this follow-up occurred in only 186 (72%) of the 259 infants who participated in the study.

The study’s premise was that vitamin D is an immune system modulator, and that New Zealand provides an excellent setting to test the hypothesis that normalized vitamin D levels can help prevent development of atopy and asthma because many of the country’s residents are vitamin D deficient due to their diet and sun avoidance to prevent skin cancers. Results from prior studies had shown that 57% of New Zealand neonates have inadequate levels of vitamin D at birth, defined as a serum level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D of less than 20 ng/ml (less than 50 nmol/L), Dr. Grant noted.

“I think this intervention will only work in populations that are vitamin D deficient,” Dr. Grant said in an interview. In his study, the average serum level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D among control neonates was 38 nmol/L (about 15 ng/mL). In contrast, neonates born to mothers who had received a daily, higher-dose vitamin D supplement during the third trimester had serum measures that were roughly twice that level.

The study enrolled 260 pregnant women from the Auckland area with a single pregnancy at 26-30 weeks’ gestation; average gestational age at baseline was 27 weeks. Dr. Grant and his associates randomized the mothers to receive 1,000 IU oral vitamin D daily, 2,000 oral vitamin D daily, or placebo. The women delivered 259 infants. Infants born to women on the lower dosage supplement then received 400 IU vitamin daily for 6 months, those born to mothers on the higher level supplement received 800 IU vitamin D daily for 6 months, and those born to mothers in the placebo group received placebo supplements daily for 6 months.

Both supplement regimens led to statistically significant increases in serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in maternal serum at 36 weeks’ gestation, in cord blood at delivery, in the neonates’ serum at ages 2 months and 4 months, and in infant serum in the higher dosage group at 6 months of age, compared with similar measures taken at all these time points in the placebo group.

In addition, the neonates in the higher dosage group had significantly higher serum levels at 2, 4, and 6 months, compared with the lower dosage group. When measured a final time at 18-month follow-up, a year after the end of vitamin D supplementation, average serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in an three subgroups of children were virtually identical and similar to maternal serum levels at baseline. Dr. Grant and his associates had previously reported these findings and also had documented the safety of both the low and high levels of vitamin D supplements for both mothers and their children (Pediatrics. 2014 Jan;133[1]:e143-53).

The new findings reported by Dr. Grant focused on clinical outcomes at 18 months. He and his colleagues ran skin-prick testing on 186 of the 259 (72%) children in the study (the remaining children weren’t available for this follow-up assessment). They tested three aeroallergens: cat, pollen, and house dust mite. They saw no significant differences in the prevalence of positive skin-prick reactions among the three study groups to cat and pollen, but prevalence levels of positive reactions to dust mite were 9% in the controls, 3% of children in the low-dosage group, and none in the high dosage group. The difference between the controls and high dosage groups was statistically significant; the difference between the controls and the low dosage group was not significant, Dr. Grant said. Additional testing of specific IgE responses to four different dust mite antigens showed statistically significant reductions in responses to each of the four antigens among the high dosage children, compared with the controls and with the low dosage children.

The researchers also tallied the number of acute, primary care office visits during the first 18 months of life among the children in each of the three subgroups for a variety of respiratory diagnoses. The three groups showed no significant differences in total number of office visits for most of these diagnoses, including colds, otitis media, croup, and bronchitis. However, about 12% of children in the control group had been seen in a primary care office for a diagnosis of asthma, compared with none of the children in the low dosage group and about 4% in the high-dosage group. The differences between the two intervention groups and the control group were statistically significant. Dr. Grant cautioned that this finding is very preliminary and that any conclusions about the impact of vitamin D supplements on asthma incidence must await studies with larger numbers of children who are followed to an older age.

Dr. Grant had no disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BALTIMORE – Three months of daily, oral treatment with a relatively high but safe dosage of a vitamin D supplement to pregnant mothers during late gestation followed by continued oral supplementation to their neonates during the first 6 months of life led to a significant reduction in the prevalence of dust-mite skin reactivity in those children once they reached 18 months old in a randomized, controlled trial with 259 mothers and infants.

And in a preliminary assessment that tallied the number of children who required primary care office visits for asthma through age 18 months, children who had received the highest vitamin D supplementation also showed a statistically significant reduction of these visits, compared with the placebo control children, Dr. Cameron C. Grant reported at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

This suggestion that the vitamin D intervention could cut asthma development is not completely certain because in 18-month-old children, diagnosis of asthma is “very insecure,” noted Dr. Grant, a pediatrician at the University of Auckland, New Zealand and at Starship Children’s Hospital, also in Auckland. In addition, a limitation of the observed effect on dust mite atopy on skin-test challenge was that this follow-up occurred in only 186 (72%) of the 259 infants who participated in the study.

The study’s premise was that vitamin D is an immune system modulator, and that New Zealand provides an excellent setting to test the hypothesis that normalized vitamin D levels can help prevent development of atopy and asthma because many of the country’s residents are vitamin D deficient due to their diet and sun avoidance to prevent skin cancers. Results from prior studies had shown that 57% of New Zealand neonates have inadequate levels of vitamin D at birth, defined as a serum level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D of less than 20 ng/ml (less than 50 nmol/L), Dr. Grant noted.

“I think this intervention will only work in populations that are vitamin D deficient,” Dr. Grant said in an interview. In his study, the average serum level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D among control neonates was 38 nmol/L (about 15 ng/mL). In contrast, neonates born to mothers who had received a daily, higher-dose vitamin D supplement during the third trimester had serum measures that were roughly twice that level.

The study enrolled 260 pregnant women from the Auckland area with a single pregnancy at 26-30 weeks’ gestation; average gestational age at baseline was 27 weeks. Dr. Grant and his associates randomized the mothers to receive 1,000 IU oral vitamin D daily, 2,000 oral vitamin D daily, or placebo. The women delivered 259 infants. Infants born to women on the lower dosage supplement then received 400 IU vitamin daily for 6 months, those born to mothers on the higher level supplement received 800 IU vitamin D daily for 6 months, and those born to mothers in the placebo group received placebo supplements daily for 6 months.

Both supplement regimens led to statistically significant increases in serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in maternal serum at 36 weeks’ gestation, in cord blood at delivery, in the neonates’ serum at ages 2 months and 4 months, and in infant serum in the higher dosage group at 6 months of age, compared with similar measures taken at all these time points in the placebo group.

In addition, the neonates in the higher dosage group had significantly higher serum levels at 2, 4, and 6 months, compared with the lower dosage group. When measured a final time at 18-month follow-up, a year after the end of vitamin D supplementation, average serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in an three subgroups of children were virtually identical and similar to maternal serum levels at baseline. Dr. Grant and his associates had previously reported these findings and also had documented the safety of both the low and high levels of vitamin D supplements for both mothers and their children (Pediatrics. 2014 Jan;133[1]:e143-53).

The new findings reported by Dr. Grant focused on clinical outcomes at 18 months. He and his colleagues ran skin-prick testing on 186 of the 259 (72%) children in the study (the remaining children weren’t available for this follow-up assessment). They tested three aeroallergens: cat, pollen, and house dust mite. They saw no significant differences in the prevalence of positive skin-prick reactions among the three study groups to cat and pollen, but prevalence levels of positive reactions to dust mite were 9% in the controls, 3% of children in the low-dosage group, and none in the high dosage group. The difference between the controls and high dosage groups was statistically significant; the difference between the controls and the low dosage group was not significant, Dr. Grant said. Additional testing of specific IgE responses to four different dust mite antigens showed statistically significant reductions in responses to each of the four antigens among the high dosage children, compared with the controls and with the low dosage children.

The researchers also tallied the number of acute, primary care office visits during the first 18 months of life among the children in each of the three subgroups for a variety of respiratory diagnoses. The three groups showed no significant differences in total number of office visits for most of these diagnoses, including colds, otitis media, croup, and bronchitis. However, about 12% of children in the control group had been seen in a primary care office for a diagnosis of asthma, compared with none of the children in the low dosage group and about 4% in the high-dosage group. The differences between the two intervention groups and the control group were statistically significant. Dr. Grant cautioned that this finding is very preliminary and that any conclusions about the impact of vitamin D supplements on asthma incidence must await studies with larger numbers of children who are followed to an older age.

Dr. Grant had no disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BALTIMORE – Three months of daily, oral treatment with a relatively high but safe dosage of a vitamin D supplement to pregnant mothers during late gestation followed by continued oral supplementation to their neonates during the first 6 months of life led to a significant reduction in the prevalence of dust-mite skin reactivity in those children once they reached 18 months old in a randomized, controlled trial with 259 mothers and infants.

And in a preliminary assessment that tallied the number of children who required primary care office visits for asthma through age 18 months, children who had received the highest vitamin D supplementation also showed a statistically significant reduction of these visits, compared with the placebo control children, Dr. Cameron C. Grant reported at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

This suggestion that the vitamin D intervention could cut asthma development is not completely certain because in 18-month-old children, diagnosis of asthma is “very insecure,” noted Dr. Grant, a pediatrician at the University of Auckland, New Zealand and at Starship Children’s Hospital, also in Auckland. In addition, a limitation of the observed effect on dust mite atopy on skin-test challenge was that this follow-up occurred in only 186 (72%) of the 259 infants who participated in the study.

The study’s premise was that vitamin D is an immune system modulator, and that New Zealand provides an excellent setting to test the hypothesis that normalized vitamin D levels can help prevent development of atopy and asthma because many of the country’s residents are vitamin D deficient due to their diet and sun avoidance to prevent skin cancers. Results from prior studies had shown that 57% of New Zealand neonates have inadequate levels of vitamin D at birth, defined as a serum level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D of less than 20 ng/ml (less than 50 nmol/L), Dr. Grant noted.