User login

European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL): International Liver Congress

Statins linked to better outcomes in hep C cirrhosis

VIENNA – Patients infected with hepatitis C virus who developed cirrhosis and received statin treatment had significantly lower rates of both death and cirrhosis decompensation, compared with cirrhosis patients who did not receive a statin in a confounder-adjusted analysis of data from more than 2,700 patients in a U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs database.

While this suggestive evidence is not strong enough to warrant routinely prescribing statins to cirrhosis patients, it does highlight the need to prescribe a statin to any cirrhosis patient who qualifies for the drug by standard criteria because of established cardiovascular disease or as part of primary prevention when there is elevated cardiovascular risk, Dr. Arpan Mohanty said at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

Conventional wisdom has often led to withholding statins from patients with liver disease out of concern for risk of statin-induced hepatotoxicity, said Dr. Mohanty, a gastroenterology researcher at Yale University in New Haven, Conn. But the new findings suggesting such overwhelming benefit from statin treatment in these patients indicates that “statin use should not be avoided” when patients with liver disease would otherwise qualify for statin treatment.

“Statins should be prescribed when required for atherosclerosis,” she said, adding that in New Haven her program has run sessions to educate primary care physicians on this.

The study used data collected during 1996-2009 by the Hepatitis C Virus Clinical Case Registry of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, which includes more than 340,000 veterans, of whom more than 45,000 had been diagnosed with cirrhosis. Further analysis identified 1,323 eligible veterans from this group on statin treatment, and 12,522 not on statin treatment. Propensity score matching narrowed the study group down to 685 hepatitis C virus–infected veterans with cirrhosis who were on statin treatment, and 2,062 closely matched veterans infected with HCV and with cirrhosis but not receiving statin therapy.

The patients averaged 56 years old, 98% were men, and comorbidities were common; a third had a history of coronary artery disease, more than 80% had hypertension, more than half had diabetes, and more than half had alcohol dependency. Among patients with a serum cholesterol level greater than 200 mg/dL, 57% were not on a statin; among those with a serum low-density cholesterol level of about 160 mg/dL, 35% were not receiving a statin. “Statin use is low in patients with cirrhosis, even in those with high cardiovascular risk,” Dr. Mohanty said.

She and her associates tracked the incidence of death for a median of more than 2 years in these patients, and they followed new episodes of cirrhosis decompensation for nearly 2 years.

With adjustment for age, body mass index, serum albumin, and fibrosis-4 and MELD (Model for End-Stage Liver Disease) scores, the rates of both death and cirrhosis decompensation were each a statistically significant 45% lower among the patients on statins, compared with those not on a statin, they reported.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

VIENNA – Patients infected with hepatitis C virus who developed cirrhosis and received statin treatment had significantly lower rates of both death and cirrhosis decompensation, compared with cirrhosis patients who did not receive a statin in a confounder-adjusted analysis of data from more than 2,700 patients in a U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs database.

While this suggestive evidence is not strong enough to warrant routinely prescribing statins to cirrhosis patients, it does highlight the need to prescribe a statin to any cirrhosis patient who qualifies for the drug by standard criteria because of established cardiovascular disease or as part of primary prevention when there is elevated cardiovascular risk, Dr. Arpan Mohanty said at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

Conventional wisdom has often led to withholding statins from patients with liver disease out of concern for risk of statin-induced hepatotoxicity, said Dr. Mohanty, a gastroenterology researcher at Yale University in New Haven, Conn. But the new findings suggesting such overwhelming benefit from statin treatment in these patients indicates that “statin use should not be avoided” when patients with liver disease would otherwise qualify for statin treatment.

“Statins should be prescribed when required for atherosclerosis,” she said, adding that in New Haven her program has run sessions to educate primary care physicians on this.

The study used data collected during 1996-2009 by the Hepatitis C Virus Clinical Case Registry of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, which includes more than 340,000 veterans, of whom more than 45,000 had been diagnosed with cirrhosis. Further analysis identified 1,323 eligible veterans from this group on statin treatment, and 12,522 not on statin treatment. Propensity score matching narrowed the study group down to 685 hepatitis C virus–infected veterans with cirrhosis who were on statin treatment, and 2,062 closely matched veterans infected with HCV and with cirrhosis but not receiving statin therapy.

The patients averaged 56 years old, 98% were men, and comorbidities were common; a third had a history of coronary artery disease, more than 80% had hypertension, more than half had diabetes, and more than half had alcohol dependency. Among patients with a serum cholesterol level greater than 200 mg/dL, 57% were not on a statin; among those with a serum low-density cholesterol level of about 160 mg/dL, 35% were not receiving a statin. “Statin use is low in patients with cirrhosis, even in those with high cardiovascular risk,” Dr. Mohanty said.

She and her associates tracked the incidence of death for a median of more than 2 years in these patients, and they followed new episodes of cirrhosis decompensation for nearly 2 years.

With adjustment for age, body mass index, serum albumin, and fibrosis-4 and MELD (Model for End-Stage Liver Disease) scores, the rates of both death and cirrhosis decompensation were each a statistically significant 45% lower among the patients on statins, compared with those not on a statin, they reported.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

VIENNA – Patients infected with hepatitis C virus who developed cirrhosis and received statin treatment had significantly lower rates of both death and cirrhosis decompensation, compared with cirrhosis patients who did not receive a statin in a confounder-adjusted analysis of data from more than 2,700 patients in a U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs database.

While this suggestive evidence is not strong enough to warrant routinely prescribing statins to cirrhosis patients, it does highlight the need to prescribe a statin to any cirrhosis patient who qualifies for the drug by standard criteria because of established cardiovascular disease or as part of primary prevention when there is elevated cardiovascular risk, Dr. Arpan Mohanty said at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

Conventional wisdom has often led to withholding statins from patients with liver disease out of concern for risk of statin-induced hepatotoxicity, said Dr. Mohanty, a gastroenterology researcher at Yale University in New Haven, Conn. But the new findings suggesting such overwhelming benefit from statin treatment in these patients indicates that “statin use should not be avoided” when patients with liver disease would otherwise qualify for statin treatment.

“Statins should be prescribed when required for atherosclerosis,” she said, adding that in New Haven her program has run sessions to educate primary care physicians on this.

The study used data collected during 1996-2009 by the Hepatitis C Virus Clinical Case Registry of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, which includes more than 340,000 veterans, of whom more than 45,000 had been diagnosed with cirrhosis. Further analysis identified 1,323 eligible veterans from this group on statin treatment, and 12,522 not on statin treatment. Propensity score matching narrowed the study group down to 685 hepatitis C virus–infected veterans with cirrhosis who were on statin treatment, and 2,062 closely matched veterans infected with HCV and with cirrhosis but not receiving statin therapy.

The patients averaged 56 years old, 98% were men, and comorbidities were common; a third had a history of coronary artery disease, more than 80% had hypertension, more than half had diabetes, and more than half had alcohol dependency. Among patients with a serum cholesterol level greater than 200 mg/dL, 57% were not on a statin; among those with a serum low-density cholesterol level of about 160 mg/dL, 35% were not receiving a statin. “Statin use is low in patients with cirrhosis, even in those with high cardiovascular risk,” Dr. Mohanty said.

She and her associates tracked the incidence of death for a median of more than 2 years in these patients, and they followed new episodes of cirrhosis decompensation for nearly 2 years.

With adjustment for age, body mass index, serum albumin, and fibrosis-4 and MELD (Model for End-Stage Liver Disease) scores, the rates of both death and cirrhosis decompensation were each a statistically significant 45% lower among the patients on statins, compared with those not on a statin, they reported.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

Unrecognized hepatitis C linked with advanced hepatic fibrosis

VIENNA – Roughly half of American adults with chronic hepatitis C infection are unaware of their infection, and about one-fifth of these people with unsuspected infection likely have advanced liver fibrosis, according to a new analysis of U.S. data.

These findings “strengthen the recommendation for hepatitis C virus (HCV) screening in asymptomatic individuals,” Dr. Prowpanga Udompap said at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

People infected by HCV with advanced liver fibrosis have top priority for receiving curative drug treatment, according to recommendations by the American Association for the Study of the Liver and the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

People who have HCV-associated liver fibrosis that goes untreated also risk having their infection become more refractory to cure over time, they risk progressive hepatic deterioration that will eventually become symptomatic, and they face increasing risk for developing liver cancer, noted Dr. W. Ray Kim, senior author of the study and professor of medicine and chief of gastroenterology and hepatology at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Dr. Kim said he was surprised that such a large percentage of Americans who have unrecognized HCV infection also probably have substantial hepatic damage. “To me it’s alarming that 20% of people who are not aware of their HCV infection are treatment candidates. These people are out there, but not getting treated,” he said in an interview.

Current U.S. HCV screening recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention call for screening all Americans born during 1945-1965, “but there is no incentive to screen” and many U.S. primary care physicians don’t have HCV screening on their radar, he said.

The analysis conducted by Dr. Udompap and Dr. Kim used data collected by the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey during 2001-2012, when the National Center for Health Statistics administered HCV testing to 45,000 of the 62,000 individuals who participated in the survey then.

Of the 45,000 people tested, 420 (0.9%) screened antibody positive and had infection confirmed by a second, RNA-based test. The HCV-positive patients then received a survey that included a question on whether they were aware of their HCV status before their current test result notification. One hundred sixty-three people (39%) completed and returned the survey: Eighty-three said they had previously been unaware they were HCV positive, and 80 said that they had known about their infection. The 50% rate of awareness of HCV chronic infection is consistent with a previously reported rate (Hepatology 2012;55:1652-61), said Dr. Udompap, a gastroenterology researcher at Stanford.

Individuals who were aware of their infection and those who were not had very similar demographic and clinical parameters. The average age was 53 years, and about two-thirds were men.

Dr. Udompap ran estimates of each respondent’s liver fibrosis and cirrhosis severity using the FIB-4 score and APRI score and data collected during the survey on age, liver enzyme levels, and platelet counts. These calculations showed that 22% of those ignorant of their HCV-positive status had a high probability of having advanced fibrosis, and 11% had a high probability of having cirrhosis, Dr. Udompap reported. These rates tracked close to those of the people who knew about their HCV-positive status, of whom 15% had a high probability of having advanced liver fibrosis and 11% were highly likely to have cirrhosis.

Dr. Udompap reported no financial disclosures. Dr. Kim has been a consultant to several drug companies that market, or are developing, drugs used in HCV.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

VIENNA – Roughly half of American adults with chronic hepatitis C infection are unaware of their infection, and about one-fifth of these people with unsuspected infection likely have advanced liver fibrosis, according to a new analysis of U.S. data.

These findings “strengthen the recommendation for hepatitis C virus (HCV) screening in asymptomatic individuals,” Dr. Prowpanga Udompap said at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

People infected by HCV with advanced liver fibrosis have top priority for receiving curative drug treatment, according to recommendations by the American Association for the Study of the Liver and the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

People who have HCV-associated liver fibrosis that goes untreated also risk having their infection become more refractory to cure over time, they risk progressive hepatic deterioration that will eventually become symptomatic, and they face increasing risk for developing liver cancer, noted Dr. W. Ray Kim, senior author of the study and professor of medicine and chief of gastroenterology and hepatology at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Dr. Kim said he was surprised that such a large percentage of Americans who have unrecognized HCV infection also probably have substantial hepatic damage. “To me it’s alarming that 20% of people who are not aware of their HCV infection are treatment candidates. These people are out there, but not getting treated,” he said in an interview.

Current U.S. HCV screening recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention call for screening all Americans born during 1945-1965, “but there is no incentive to screen” and many U.S. primary care physicians don’t have HCV screening on their radar, he said.

The analysis conducted by Dr. Udompap and Dr. Kim used data collected by the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey during 2001-2012, when the National Center for Health Statistics administered HCV testing to 45,000 of the 62,000 individuals who participated in the survey then.

Of the 45,000 people tested, 420 (0.9%) screened antibody positive and had infection confirmed by a second, RNA-based test. The HCV-positive patients then received a survey that included a question on whether they were aware of their HCV status before their current test result notification. One hundred sixty-three people (39%) completed and returned the survey: Eighty-three said they had previously been unaware they were HCV positive, and 80 said that they had known about their infection. The 50% rate of awareness of HCV chronic infection is consistent with a previously reported rate (Hepatology 2012;55:1652-61), said Dr. Udompap, a gastroenterology researcher at Stanford.

Individuals who were aware of their infection and those who were not had very similar demographic and clinical parameters. The average age was 53 years, and about two-thirds were men.

Dr. Udompap ran estimates of each respondent’s liver fibrosis and cirrhosis severity using the FIB-4 score and APRI score and data collected during the survey on age, liver enzyme levels, and platelet counts. These calculations showed that 22% of those ignorant of their HCV-positive status had a high probability of having advanced fibrosis, and 11% had a high probability of having cirrhosis, Dr. Udompap reported. These rates tracked close to those of the people who knew about their HCV-positive status, of whom 15% had a high probability of having advanced liver fibrosis and 11% were highly likely to have cirrhosis.

Dr. Udompap reported no financial disclosures. Dr. Kim has been a consultant to several drug companies that market, or are developing, drugs used in HCV.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

VIENNA – Roughly half of American adults with chronic hepatitis C infection are unaware of their infection, and about one-fifth of these people with unsuspected infection likely have advanced liver fibrosis, according to a new analysis of U.S. data.

These findings “strengthen the recommendation for hepatitis C virus (HCV) screening in asymptomatic individuals,” Dr. Prowpanga Udompap said at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

People infected by HCV with advanced liver fibrosis have top priority for receiving curative drug treatment, according to recommendations by the American Association for the Study of the Liver and the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

People who have HCV-associated liver fibrosis that goes untreated also risk having their infection become more refractory to cure over time, they risk progressive hepatic deterioration that will eventually become symptomatic, and they face increasing risk for developing liver cancer, noted Dr. W. Ray Kim, senior author of the study and professor of medicine and chief of gastroenterology and hepatology at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Dr. Kim said he was surprised that such a large percentage of Americans who have unrecognized HCV infection also probably have substantial hepatic damage. “To me it’s alarming that 20% of people who are not aware of their HCV infection are treatment candidates. These people are out there, but not getting treated,” he said in an interview.

Current U.S. HCV screening recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention call for screening all Americans born during 1945-1965, “but there is no incentive to screen” and many U.S. primary care physicians don’t have HCV screening on their radar, he said.

The analysis conducted by Dr. Udompap and Dr. Kim used data collected by the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey during 2001-2012, when the National Center for Health Statistics administered HCV testing to 45,000 of the 62,000 individuals who participated in the survey then.

Of the 45,000 people tested, 420 (0.9%) screened antibody positive and had infection confirmed by a second, RNA-based test. The HCV-positive patients then received a survey that included a question on whether they were aware of their HCV status before their current test result notification. One hundred sixty-three people (39%) completed and returned the survey: Eighty-three said they had previously been unaware they were HCV positive, and 80 said that they had known about their infection. The 50% rate of awareness of HCV chronic infection is consistent with a previously reported rate (Hepatology 2012;55:1652-61), said Dr. Udompap, a gastroenterology researcher at Stanford.

Individuals who were aware of their infection and those who were not had very similar demographic and clinical parameters. The average age was 53 years, and about two-thirds were men.

Dr. Udompap ran estimates of each respondent’s liver fibrosis and cirrhosis severity using the FIB-4 score and APRI score and data collected during the survey on age, liver enzyme levels, and platelet counts. These calculations showed that 22% of those ignorant of their HCV-positive status had a high probability of having advanced fibrosis, and 11% had a high probability of having cirrhosis, Dr. Udompap reported. These rates tracked close to those of the people who knew about their HCV-positive status, of whom 15% had a high probability of having advanced liver fibrosis and 11% were highly likely to have cirrhosis.

Dr. Udompap reported no financial disclosures. Dr. Kim has been a consultant to several drug companies that market, or are developing, drugs used in HCV.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

Key clinical point: One-fifth of Americans with unrecognized chronic hepatitis C infection likely have advanced hepatic fibrosis.

Major finding: Among U.S. adults with unrecognized chronic hepatitis C infection, 22% had laboratory results indicating a high probability of advanced hepatic fibrosis.

Data source: Data collected from 420 Americans found to have a chronic hepatitis C infection in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey during 2001-2012.

Disclosures: Dr. Udompap reported having no financial disclosures. Dr. Kim has been a consultant to several drug companies that market or develop drugs to eradicate hepatitis C infections.

Shortening all-oral HCV therapy feasible

VIENNA – All-oral HCV therapy with grazoprevir and elbasvir plus sofosbuvir achieved high, sustained virologic response (SVR) rates at 12 weeks after only 6-8 weeks of therapy in a proof-of-concept phase II study.

“HCV therapy is evolving toward a once-daily, short duration, pan-genotypic, highly effective and safe regimen,” said Dr. Fred Poordad of the Texas Liver Institute, San Antonio, who reported the findings of the C-SWIFT study at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

“The aim of this study was to combine three highly potent direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) grazoprevir, elbasvir and sofosbuvir, each with a different mechanisms of action, to see if we could shorten therapy in two of the most difficult-to-cure populations, genotype 1 [GT1] and genotype 3 [GT3] with and without cirrhosis,” he said.

For inclusion, patients had to be treatment naive and older than 18 years of age. Cirrhosis had to be present, assessed either by liver biopsy or via noninvasive testing, and the minimum hemoglobin at enrollment needed to be 9.5 g/dL. Patients also had to be negative for HIV and the hepatitis B virus, and have liver enzyme below 350 IU/L.

Treatment consisted of a fixed-dose, once daily combination of grazoprevir 100 mg and elbasvir 50 mg plus additional sofosbuvir 400 mg, once daily. The duration of therapy depended on genotype and the presence or absence of cirrhosis.

A total of 102 patients with GT1 were enrolled, of whom 61 had no cirrhosis and were treated with the three-drug combination for a total of 4 (n = 31) or 6 (n = 30) weeks. Patients with GT1 and cirrhosis were treated with the regimen for 6 (n = 20) or 8 (n = 21) weeks.

There were 41 GT3 patients enrolled, of whom 29 had no cirrhosis and were treated for 8 (n = 15) or 12 weeks (n = 14). The 12 GT3 cirrhotic patients received 12 weeks of the regimen.

Dr. Poordad noted that the majority of patients studied were male, in their mid-50s, and of white ethnicity. The majority of the GT1 patients were subtype 1a.

Results showed that 33% of GT1 patients without cirrhosis achieved SVR12 with 4 weeks of treatment, and 87% with 6 weeks therapy. SVR12 was achieved in 80% and 94% of patients with GT1 and cirrhosis after 6 and 8 weeks of therapy, respectively.

No patient experienced breakthrough. Twenty of the noncirrhotic GT1 patients treated for 4 weeks relapsed, as did four who were treated for 6 weeks. Four relapses also occurred in cirrhotic GT1 patients treated for 6 weeks and one patient with cirrhosis relapsed after 8 weeks of treatment.

Dr. Poordad noted that patients relapsed most commonly if they had either wild-type virus or resistant-associated variants (RAV) already present at baseline.

In the GT3 arms, SVR12 was achieved by 93% and 100% of the noncirrhotic patients treated for 8 weeks and 12 weeks, respectively, and by 91% of those with cirrhosis who had 12 weeks of treatment. One patient discontinued treatment early for a reason other than virologic failure and two patients relapsed – one patient without cirrhosis in the 8-week treatment group and one in the cirrhotic group.

“All of the patients became ‘target not detected’ at the end of treatment,” Dr. Poordad observed. “The patient in the 8-week arm relapsed somewhere between SVR4 and SVR12, while the cirrhotic patient relapsed in the first 4 weeks of follow-up” he said.

Of the two GT3 patients with biologic failures, one did not have baseline RAVS and also had wild-type virus at relapse. The other patient had RAVs at baseline in NS3 and in NS5A at relapse.

There were “very few adverse events,” Dr. Poordad said, noting that there were no significant declines in hemoglobin or elevations in liver enzymes or bilirubin. The most common adverse events were headache, fatigue, and nausea, all of which occurred in fairly low numbers.

“This novel regimen of grazoprevir/elbasvir with sofosbuvir was able to shorten therapy duration to 8 weeks or less among patients who were cirrhotic and noncirrhotic with genotype 1,” Dr. Poordad said in summary.

Even GT3 patients were able to achieve high SVR12 rates with 8-12 weeks of therapy, including those who had cirrhosis.

“The concept of shortening therapy, even in the cirrhotic patients, has been demonstrated by this study,” he concluded.

He noted that retreatment of virologic failures was ongoing.

The study was sponsored by Merck & Co. Dr. Poordad has received grant/research support from Merck & Co. and numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

VIENNA – All-oral HCV therapy with grazoprevir and elbasvir plus sofosbuvir achieved high, sustained virologic response (SVR) rates at 12 weeks after only 6-8 weeks of therapy in a proof-of-concept phase II study.

“HCV therapy is evolving toward a once-daily, short duration, pan-genotypic, highly effective and safe regimen,” said Dr. Fred Poordad of the Texas Liver Institute, San Antonio, who reported the findings of the C-SWIFT study at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

“The aim of this study was to combine three highly potent direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) grazoprevir, elbasvir and sofosbuvir, each with a different mechanisms of action, to see if we could shorten therapy in two of the most difficult-to-cure populations, genotype 1 [GT1] and genotype 3 [GT3] with and without cirrhosis,” he said.

For inclusion, patients had to be treatment naive and older than 18 years of age. Cirrhosis had to be present, assessed either by liver biopsy or via noninvasive testing, and the minimum hemoglobin at enrollment needed to be 9.5 g/dL. Patients also had to be negative for HIV and the hepatitis B virus, and have liver enzyme below 350 IU/L.

Treatment consisted of a fixed-dose, once daily combination of grazoprevir 100 mg and elbasvir 50 mg plus additional sofosbuvir 400 mg, once daily. The duration of therapy depended on genotype and the presence or absence of cirrhosis.

A total of 102 patients with GT1 were enrolled, of whom 61 had no cirrhosis and were treated with the three-drug combination for a total of 4 (n = 31) or 6 (n = 30) weeks. Patients with GT1 and cirrhosis were treated with the regimen for 6 (n = 20) or 8 (n = 21) weeks.

There were 41 GT3 patients enrolled, of whom 29 had no cirrhosis and were treated for 8 (n = 15) or 12 weeks (n = 14). The 12 GT3 cirrhotic patients received 12 weeks of the regimen.

Dr. Poordad noted that the majority of patients studied were male, in their mid-50s, and of white ethnicity. The majority of the GT1 patients were subtype 1a.

Results showed that 33% of GT1 patients without cirrhosis achieved SVR12 with 4 weeks of treatment, and 87% with 6 weeks therapy. SVR12 was achieved in 80% and 94% of patients with GT1 and cirrhosis after 6 and 8 weeks of therapy, respectively.

No patient experienced breakthrough. Twenty of the noncirrhotic GT1 patients treated for 4 weeks relapsed, as did four who were treated for 6 weeks. Four relapses also occurred in cirrhotic GT1 patients treated for 6 weeks and one patient with cirrhosis relapsed after 8 weeks of treatment.

Dr. Poordad noted that patients relapsed most commonly if they had either wild-type virus or resistant-associated variants (RAV) already present at baseline.

In the GT3 arms, SVR12 was achieved by 93% and 100% of the noncirrhotic patients treated for 8 weeks and 12 weeks, respectively, and by 91% of those with cirrhosis who had 12 weeks of treatment. One patient discontinued treatment early for a reason other than virologic failure and two patients relapsed – one patient without cirrhosis in the 8-week treatment group and one in the cirrhotic group.

“All of the patients became ‘target not detected’ at the end of treatment,” Dr. Poordad observed. “The patient in the 8-week arm relapsed somewhere between SVR4 and SVR12, while the cirrhotic patient relapsed in the first 4 weeks of follow-up” he said.

Of the two GT3 patients with biologic failures, one did not have baseline RAVS and also had wild-type virus at relapse. The other patient had RAVs at baseline in NS3 and in NS5A at relapse.

There were “very few adverse events,” Dr. Poordad said, noting that there were no significant declines in hemoglobin or elevations in liver enzymes or bilirubin. The most common adverse events were headache, fatigue, and nausea, all of which occurred in fairly low numbers.

“This novel regimen of grazoprevir/elbasvir with sofosbuvir was able to shorten therapy duration to 8 weeks or less among patients who were cirrhotic and noncirrhotic with genotype 1,” Dr. Poordad said in summary.

Even GT3 patients were able to achieve high SVR12 rates with 8-12 weeks of therapy, including those who had cirrhosis.

“The concept of shortening therapy, even in the cirrhotic patients, has been demonstrated by this study,” he concluded.

He noted that retreatment of virologic failures was ongoing.

The study was sponsored by Merck & Co. Dr. Poordad has received grant/research support from Merck & Co. and numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

VIENNA – All-oral HCV therapy with grazoprevir and elbasvir plus sofosbuvir achieved high, sustained virologic response (SVR) rates at 12 weeks after only 6-8 weeks of therapy in a proof-of-concept phase II study.

“HCV therapy is evolving toward a once-daily, short duration, pan-genotypic, highly effective and safe regimen,” said Dr. Fred Poordad of the Texas Liver Institute, San Antonio, who reported the findings of the C-SWIFT study at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

“The aim of this study was to combine three highly potent direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) grazoprevir, elbasvir and sofosbuvir, each with a different mechanisms of action, to see if we could shorten therapy in two of the most difficult-to-cure populations, genotype 1 [GT1] and genotype 3 [GT3] with and without cirrhosis,” he said.

For inclusion, patients had to be treatment naive and older than 18 years of age. Cirrhosis had to be present, assessed either by liver biopsy or via noninvasive testing, and the minimum hemoglobin at enrollment needed to be 9.5 g/dL. Patients also had to be negative for HIV and the hepatitis B virus, and have liver enzyme below 350 IU/L.

Treatment consisted of a fixed-dose, once daily combination of grazoprevir 100 mg and elbasvir 50 mg plus additional sofosbuvir 400 mg, once daily. The duration of therapy depended on genotype and the presence or absence of cirrhosis.

A total of 102 patients with GT1 were enrolled, of whom 61 had no cirrhosis and were treated with the three-drug combination for a total of 4 (n = 31) or 6 (n = 30) weeks. Patients with GT1 and cirrhosis were treated with the regimen for 6 (n = 20) or 8 (n = 21) weeks.

There were 41 GT3 patients enrolled, of whom 29 had no cirrhosis and were treated for 8 (n = 15) or 12 weeks (n = 14). The 12 GT3 cirrhotic patients received 12 weeks of the regimen.

Dr. Poordad noted that the majority of patients studied were male, in their mid-50s, and of white ethnicity. The majority of the GT1 patients were subtype 1a.

Results showed that 33% of GT1 patients without cirrhosis achieved SVR12 with 4 weeks of treatment, and 87% with 6 weeks therapy. SVR12 was achieved in 80% and 94% of patients with GT1 and cirrhosis after 6 and 8 weeks of therapy, respectively.

No patient experienced breakthrough. Twenty of the noncirrhotic GT1 patients treated for 4 weeks relapsed, as did four who were treated for 6 weeks. Four relapses also occurred in cirrhotic GT1 patients treated for 6 weeks and one patient with cirrhosis relapsed after 8 weeks of treatment.

Dr. Poordad noted that patients relapsed most commonly if they had either wild-type virus or resistant-associated variants (RAV) already present at baseline.

In the GT3 arms, SVR12 was achieved by 93% and 100% of the noncirrhotic patients treated for 8 weeks and 12 weeks, respectively, and by 91% of those with cirrhosis who had 12 weeks of treatment. One patient discontinued treatment early for a reason other than virologic failure and two patients relapsed – one patient without cirrhosis in the 8-week treatment group and one in the cirrhotic group.

“All of the patients became ‘target not detected’ at the end of treatment,” Dr. Poordad observed. “The patient in the 8-week arm relapsed somewhere between SVR4 and SVR12, while the cirrhotic patient relapsed in the first 4 weeks of follow-up” he said.

Of the two GT3 patients with biologic failures, one did not have baseline RAVS and also had wild-type virus at relapse. The other patient had RAVs at baseline in NS3 and in NS5A at relapse.

There were “very few adverse events,” Dr. Poordad said, noting that there were no significant declines in hemoglobin or elevations in liver enzymes or bilirubin. The most common adverse events were headache, fatigue, and nausea, all of which occurred in fairly low numbers.

“This novel regimen of grazoprevir/elbasvir with sofosbuvir was able to shorten therapy duration to 8 weeks or less among patients who were cirrhotic and noncirrhotic with genotype 1,” Dr. Poordad said in summary.

Even GT3 patients were able to achieve high SVR12 rates with 8-12 weeks of therapy, including those who had cirrhosis.

“The concept of shortening therapy, even in the cirrhotic patients, has been demonstrated by this study,” he concluded.

He noted that retreatment of virologic failures was ongoing.

The study was sponsored by Merck & Co. Dr. Poordad has received grant/research support from Merck & Co. and numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

AT THE INTERNATIONAL LIVER CONGRESS 2015

Key clinical point: Shortening HCV therapy to 6-8 weeks is possible, even in cirrhotic patients.

Major finding: SVR12 was achieved by 87%-94% of GT1 patients treated for 6-8 weeks and by 91%-100% of GT3 patients treated for 8-12 weeks.

Data source: Phase II, open-label study of 143 treatment-naive patients with HCV genotype 1 or 3 with or without cirrhosis treated with a fixed-dose combination of grazoprevir (100 mg) and elbasvir (50 mg) plus sofosbuvir (400 mg) for 4, 6, 8, or 12 weeks.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by Merck & Co. Dr. Poordad has received grant/research support from Merck & Co. and numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

ILC: Direct Antivirals Safely Clear HCV Despite ESRD

VIENNA – A 12-week, fixed-dose regimen safely and effectively eradicated chronic hepatitis C infection from the first 10 patients with advanced chronic kidney disease in a multicenter U.S. series.

The regimen of three direct antiviral agents is already on the U.S. market. So far, 20 HCV patients with advanced chronic kidney disease have been treated and there have been no cases of virologic failure. All 10 patients who have been followed for at least 4 weeks after completing treatment sustained their virologic response, Dr. Paul J. Pockros said at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

The series has exclusively enrolled patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. The seven enrolled patients infected with genotype 1b HCV received the three direct antiviral agents only, the combination of ombitasvir, paritaprevir boosted with ritonavir, and dasabuvir, which together are marketed as Viekira Pak. The 13 patients with a genotype 1a infection received treatment with both the three-drug regimen plus ribavirin, which was effective but resulted in significant hemoglobin reduction in eight patients that required dosage interruptions. All patients were then able to restart and continue treatment, said Dr. Pockros, a gastroenterologist at the Scripps Clinic in La Jolla, Calif.

The efficacy and safety of these three direct antivirals in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease – an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of no greater than 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 – contrasts with the caution that exists for another major, direct antiviral agent for hepatitis C eradication, sofosbuvir, which is marketed as Sovaldi as an individual drug and as Harvoni when formulated with ledipavir. The labels for both forms of sofosbuvir say that the drug’s safety and efficacy “has not been established in patients with severe renal impairment (eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73m2) or end stage renal disease (ESRD) requiring hemodialysis. No dose recommendation can be given for patients with severe renal impairment or ESRD.”

A new phase of the trial starting soon will test whether patients infected with genotype 1a HCV can be effectively treated with the three direct antiviral agents alone without ribavirin, Dr. Pockros said. Another soon-to-start aspect of the trial will test the regimen in patients with cirrhosis. The current series has so far enrolled only treatment naive patients without cirrhosis.

The RUBY-1 trial has been run at nine U.S. centers, where researchers enrolled seven patients with stage 4 chronic kidney disease (an eGFR of 15-29 ml/min/ 1.73m2), and 13 patients on hemodialysis and with stage 5 chronic kidney disease, defined as an eGFR of less than 15 mL/min/1.73m2. Fourteen of the 20 enrolled patients (70%) were African American, and 15% were Hispanic, a demographic pattern that is “a fair representation” of U.S. patients with both hepatitis C infection and end-stage renal disease, Dr. Prockros said.

The three direct antivirals tested in the current study are all metabolized in the liver and require no dose modification when used in patients with renal dysfunction. Pharmacokinetic studies done as part of the study showed no differences in blood levels of these drugs in the patients with advanced chronic kidney disease compared with historical patients with better renal function. Several reports published in 2014 documented the efficacy of ombitasvir, paritaprevir plus ritonavir, and dasabuvir for eradicating chronic HCV infection in patients with more normal renal function (N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;370:1594-1603, 1604-14, 1973-82, 1983-92).

RUBY-1 was sponsored by AbbVie, which markets Viekira Pak. Dr. Pockros disclosed ties with AbbVie, Janssen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Merck, Conatus, and Roche Molecular.

VIENNA – A 12-week, fixed-dose regimen safely and effectively eradicated chronic hepatitis C infection from the first 10 patients with advanced chronic kidney disease in a multicenter U.S. series.

The regimen of three direct antiviral agents is already on the U.S. market. So far, 20 HCV patients with advanced chronic kidney disease have been treated and there have been no cases of virologic failure. All 10 patients who have been followed for at least 4 weeks after completing treatment sustained their virologic response, Dr. Paul J. Pockros said at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

The series has exclusively enrolled patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. The seven enrolled patients infected with genotype 1b HCV received the three direct antiviral agents only, the combination of ombitasvir, paritaprevir boosted with ritonavir, and dasabuvir, which together are marketed as Viekira Pak. The 13 patients with a genotype 1a infection received treatment with both the three-drug regimen plus ribavirin, which was effective but resulted in significant hemoglobin reduction in eight patients that required dosage interruptions. All patients were then able to restart and continue treatment, said Dr. Pockros, a gastroenterologist at the Scripps Clinic in La Jolla, Calif.

The efficacy and safety of these three direct antivirals in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease – an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of no greater than 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 – contrasts with the caution that exists for another major, direct antiviral agent for hepatitis C eradication, sofosbuvir, which is marketed as Sovaldi as an individual drug and as Harvoni when formulated with ledipavir. The labels for both forms of sofosbuvir say that the drug’s safety and efficacy “has not been established in patients with severe renal impairment (eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73m2) or end stage renal disease (ESRD) requiring hemodialysis. No dose recommendation can be given for patients with severe renal impairment or ESRD.”

A new phase of the trial starting soon will test whether patients infected with genotype 1a HCV can be effectively treated with the three direct antiviral agents alone without ribavirin, Dr. Pockros said. Another soon-to-start aspect of the trial will test the regimen in patients with cirrhosis. The current series has so far enrolled only treatment naive patients without cirrhosis.

The RUBY-1 trial has been run at nine U.S. centers, where researchers enrolled seven patients with stage 4 chronic kidney disease (an eGFR of 15-29 ml/min/ 1.73m2), and 13 patients on hemodialysis and with stage 5 chronic kidney disease, defined as an eGFR of less than 15 mL/min/1.73m2. Fourteen of the 20 enrolled patients (70%) were African American, and 15% were Hispanic, a demographic pattern that is “a fair representation” of U.S. patients with both hepatitis C infection and end-stage renal disease, Dr. Prockros said.

The three direct antivirals tested in the current study are all metabolized in the liver and require no dose modification when used in patients with renal dysfunction. Pharmacokinetic studies done as part of the study showed no differences in blood levels of these drugs in the patients with advanced chronic kidney disease compared with historical patients with better renal function. Several reports published in 2014 documented the efficacy of ombitasvir, paritaprevir plus ritonavir, and dasabuvir for eradicating chronic HCV infection in patients with more normal renal function (N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;370:1594-1603, 1604-14, 1973-82, 1983-92).

RUBY-1 was sponsored by AbbVie, which markets Viekira Pak. Dr. Pockros disclosed ties with AbbVie, Janssen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Merck, Conatus, and Roche Molecular.

VIENNA – A 12-week, fixed-dose regimen safely and effectively eradicated chronic hepatitis C infection from the first 10 patients with advanced chronic kidney disease in a multicenter U.S. series.

The regimen of three direct antiviral agents is already on the U.S. market. So far, 20 HCV patients with advanced chronic kidney disease have been treated and there have been no cases of virologic failure. All 10 patients who have been followed for at least 4 weeks after completing treatment sustained their virologic response, Dr. Paul J. Pockros said at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

The series has exclusively enrolled patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. The seven enrolled patients infected with genotype 1b HCV received the three direct antiviral agents only, the combination of ombitasvir, paritaprevir boosted with ritonavir, and dasabuvir, which together are marketed as Viekira Pak. The 13 patients with a genotype 1a infection received treatment with both the three-drug regimen plus ribavirin, which was effective but resulted in significant hemoglobin reduction in eight patients that required dosage interruptions. All patients were then able to restart and continue treatment, said Dr. Pockros, a gastroenterologist at the Scripps Clinic in La Jolla, Calif.

The efficacy and safety of these three direct antivirals in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease – an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of no greater than 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 – contrasts with the caution that exists for another major, direct antiviral agent for hepatitis C eradication, sofosbuvir, which is marketed as Sovaldi as an individual drug and as Harvoni when formulated with ledipavir. The labels for both forms of sofosbuvir say that the drug’s safety and efficacy “has not been established in patients with severe renal impairment (eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73m2) or end stage renal disease (ESRD) requiring hemodialysis. No dose recommendation can be given for patients with severe renal impairment or ESRD.”

A new phase of the trial starting soon will test whether patients infected with genotype 1a HCV can be effectively treated with the three direct antiviral agents alone without ribavirin, Dr. Pockros said. Another soon-to-start aspect of the trial will test the regimen in patients with cirrhosis. The current series has so far enrolled only treatment naive patients without cirrhosis.

The RUBY-1 trial has been run at nine U.S. centers, where researchers enrolled seven patients with stage 4 chronic kidney disease (an eGFR of 15-29 ml/min/ 1.73m2), and 13 patients on hemodialysis and with stage 5 chronic kidney disease, defined as an eGFR of less than 15 mL/min/1.73m2. Fourteen of the 20 enrolled patients (70%) were African American, and 15% were Hispanic, a demographic pattern that is “a fair representation” of U.S. patients with both hepatitis C infection and end-stage renal disease, Dr. Prockros said.

The three direct antivirals tested in the current study are all metabolized in the liver and require no dose modification when used in patients with renal dysfunction. Pharmacokinetic studies done as part of the study showed no differences in blood levels of these drugs in the patients with advanced chronic kidney disease compared with historical patients with better renal function. Several reports published in 2014 documented the efficacy of ombitasvir, paritaprevir plus ritonavir, and dasabuvir for eradicating chronic HCV infection in patients with more normal renal function (N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;370:1594-1603, 1604-14, 1973-82, 1983-92).

RUBY-1 was sponsored by AbbVie, which markets Viekira Pak. Dr. Pockros disclosed ties with AbbVie, Janssen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Merck, Conatus, and Roche Molecular.

AT THE INTERNATIONAL LIVER CONGRESS 2015

ILC: Direct antivirals safely clear HCV despite ESRD

VIENNA – A 12-week, fixed-dose regimen safely and effectively eradicated chronic hepatitis C infection from the first 10 patients with advanced chronic kidney disease in a multicenter U.S. series.

The regimen of three direct antiviral agents is already on the U.S. market. So far, 20 HCV patients with advanced chronic kidney disease have been treated and there have been no cases of virologic failure. All 10 patients who have been followed for at least 4 weeks after completing treatment sustained their virologic response, Dr. Paul J. Pockros said at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

The series has exclusively enrolled patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. The seven enrolled patients infected with genotype 1b HCV received the three direct antiviral agents only, the combination of ombitasvir, paritaprevir boosted with ritonavir, and dasabuvir, which together are marketed as Viekira Pak. The 13 patients with a genotype 1a infection received treatment with both the three-drug regimen plus ribavirin, which was effective but resulted in significant hemoglobin reduction in eight patients that required dosage interruptions. All patients were then able to restart and continue treatment, said Dr. Pockros, a gastroenterologist at the Scripps Clinic in La Jolla, Calif.

The efficacy and safety of these three direct antivirals in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease – an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of no greater than 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 – contrasts with the caution that exists for another major, direct antiviral agent for hepatitis C eradication, sofosbuvir, which is marketed as Sovaldi as an individual drug and as Harvoni when formulated with ledipavir. The labels for both forms of sofosbuvir say that the drug’s safety and efficacy “has not been established in patients with severe renal impairment (eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73m2) or end stage renal disease (ESRD) requiring hemodialysis. No dose recommendation can be given for patients with severe renal impairment or ESRD.”

A new phase of the trial starting soon will test whether patients infected with genotype 1a HCV can be effectively treated with the three direct antiviral agents alone without ribavirin, Dr. Pockros said. Another soon-to-start aspect of the trial will test the regimen in patients with cirrhosis. The current series has so far enrolled only treatment naive patients without cirrhosis.

The RUBY-1 trial has been run at nine U.S. centers, where researchers enrolled seven patients with stage 4 chronic kidney disease (an eGFR of 15-29 ml/min/ 1.73m2), and 13 patients on hemodialysis and with stage 5 chronic kidney disease, defined as an eGFR of less than 15 mL/min/1.73m2. Fourteen of the 20 enrolled patients (70%) were African American, and 15% were Hispanic, a demographic pattern that is “a fair representation” of U.S. patients with both hepatitis C infection and end-stage renal disease, Dr. Prockros said.

The three direct antivirals tested in the current study are all metabolized in the liver and require no dose modification when used in patients with renal dysfunction. Pharmacokinetic studies done as part of the study showed no differences in blood levels of these drugs in the patients with advanced chronic kidney disease compared with historical patients with better renal function. Several reports published in 2014 documented the efficacy of ombitasvir, paritaprevir plus ritonavir, and dasabuvir for eradicating chronic HCV infection in patients with more normal renal function (N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;370:1594-1603, 1604-14, 1973-82, 1983-92).

RUBY-1 was sponsored by AbbVie, which markets Viekira Pak. Dr. Pockros disclosed ties with AbbVie, Janssen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Merck, Conatus, and Roche Molecular.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

VIENNA – A 12-week, fixed-dose regimen safely and effectively eradicated chronic hepatitis C infection from the first 10 patients with advanced chronic kidney disease in a multicenter U.S. series.

The regimen of three direct antiviral agents is already on the U.S. market. So far, 20 HCV patients with advanced chronic kidney disease have been treated and there have been no cases of virologic failure. All 10 patients who have been followed for at least 4 weeks after completing treatment sustained their virologic response, Dr. Paul J. Pockros said at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

The series has exclusively enrolled patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. The seven enrolled patients infected with genotype 1b HCV received the three direct antiviral agents only, the combination of ombitasvir, paritaprevir boosted with ritonavir, and dasabuvir, which together are marketed as Viekira Pak. The 13 patients with a genotype 1a infection received treatment with both the three-drug regimen plus ribavirin, which was effective but resulted in significant hemoglobin reduction in eight patients that required dosage interruptions. All patients were then able to restart and continue treatment, said Dr. Pockros, a gastroenterologist at the Scripps Clinic in La Jolla, Calif.

The efficacy and safety of these three direct antivirals in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease – an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of no greater than 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 – contrasts with the caution that exists for another major, direct antiviral agent for hepatitis C eradication, sofosbuvir, which is marketed as Sovaldi as an individual drug and as Harvoni when formulated with ledipavir. The labels for both forms of sofosbuvir say that the drug’s safety and efficacy “has not been established in patients with severe renal impairment (eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73m2) or end stage renal disease (ESRD) requiring hemodialysis. No dose recommendation can be given for patients with severe renal impairment or ESRD.”

A new phase of the trial starting soon will test whether patients infected with genotype 1a HCV can be effectively treated with the three direct antiviral agents alone without ribavirin, Dr. Pockros said. Another soon-to-start aspect of the trial will test the regimen in patients with cirrhosis. The current series has so far enrolled only treatment naive patients without cirrhosis.

The RUBY-1 trial has been run at nine U.S. centers, where researchers enrolled seven patients with stage 4 chronic kidney disease (an eGFR of 15-29 ml/min/ 1.73m2), and 13 patients on hemodialysis and with stage 5 chronic kidney disease, defined as an eGFR of less than 15 mL/min/1.73m2. Fourteen of the 20 enrolled patients (70%) were African American, and 15% were Hispanic, a demographic pattern that is “a fair representation” of U.S. patients with both hepatitis C infection and end-stage renal disease, Dr. Prockros said.

The three direct antivirals tested in the current study are all metabolized in the liver and require no dose modification when used in patients with renal dysfunction. Pharmacokinetic studies done as part of the study showed no differences in blood levels of these drugs in the patients with advanced chronic kidney disease compared with historical patients with better renal function. Several reports published in 2014 documented the efficacy of ombitasvir, paritaprevir plus ritonavir, and dasabuvir for eradicating chronic HCV infection in patients with more normal renal function (N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;370:1594-1603, 1604-14, 1973-82, 1983-92).

RUBY-1 was sponsored by AbbVie, which markets Viekira Pak. Dr. Pockros disclosed ties with AbbVie, Janssen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Merck, Conatus, and Roche Molecular.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

VIENNA – A 12-week, fixed-dose regimen safely and effectively eradicated chronic hepatitis C infection from the first 10 patients with advanced chronic kidney disease in a multicenter U.S. series.

The regimen of three direct antiviral agents is already on the U.S. market. So far, 20 HCV patients with advanced chronic kidney disease have been treated and there have been no cases of virologic failure. All 10 patients who have been followed for at least 4 weeks after completing treatment sustained their virologic response, Dr. Paul J. Pockros said at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

The series has exclusively enrolled patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. The seven enrolled patients infected with genotype 1b HCV received the three direct antiviral agents only, the combination of ombitasvir, paritaprevir boosted with ritonavir, and dasabuvir, which together are marketed as Viekira Pak. The 13 patients with a genotype 1a infection received treatment with both the three-drug regimen plus ribavirin, which was effective but resulted in significant hemoglobin reduction in eight patients that required dosage interruptions. All patients were then able to restart and continue treatment, said Dr. Pockros, a gastroenterologist at the Scripps Clinic in La Jolla, Calif.

The efficacy and safety of these three direct antivirals in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease – an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of no greater than 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 – contrasts with the caution that exists for another major, direct antiviral agent for hepatitis C eradication, sofosbuvir, which is marketed as Sovaldi as an individual drug and as Harvoni when formulated with ledipavir. The labels for both forms of sofosbuvir say that the drug’s safety and efficacy “has not been established in patients with severe renal impairment (eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73m2) or end stage renal disease (ESRD) requiring hemodialysis. No dose recommendation can be given for patients with severe renal impairment or ESRD.”

A new phase of the trial starting soon will test whether patients infected with genotype 1a HCV can be effectively treated with the three direct antiviral agents alone without ribavirin, Dr. Pockros said. Another soon-to-start aspect of the trial will test the regimen in patients with cirrhosis. The current series has so far enrolled only treatment naive patients without cirrhosis.

The RUBY-1 trial has been run at nine U.S. centers, where researchers enrolled seven patients with stage 4 chronic kidney disease (an eGFR of 15-29 ml/min/ 1.73m2), and 13 patients on hemodialysis and with stage 5 chronic kidney disease, defined as an eGFR of less than 15 mL/min/1.73m2. Fourteen of the 20 enrolled patients (70%) were African American, and 15% were Hispanic, a demographic pattern that is “a fair representation” of U.S. patients with both hepatitis C infection and end-stage renal disease, Dr. Prockros said.

The three direct antivirals tested in the current study are all metabolized in the liver and require no dose modification when used in patients with renal dysfunction. Pharmacokinetic studies done as part of the study showed no differences in blood levels of these drugs in the patients with advanced chronic kidney disease compared with historical patients with better renal function. Several reports published in 2014 documented the efficacy of ombitasvir, paritaprevir plus ritonavir, and dasabuvir for eradicating chronic HCV infection in patients with more normal renal function (N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;370:1594-1603, 1604-14, 1973-82, 1983-92).

RUBY-1 was sponsored by AbbVie, which markets Viekira Pak. Dr. Pockros disclosed ties with AbbVie, Janssen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Merck, Conatus, and Roche Molecular.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE INTERNATIONAL LIVER CONGRESS 2015

Key clinical point: The trio of direct antiviral agents marketed as Viekira Pak safely eradicated chronic genotype 1 hepatitis C infection in patients with chronic kidney disease.

Major finding: All 10 patients followed so far to at least 4 weeks after completing treatment maintained a sustained virologic response.

Data source: RUBY-1, an open-label series of 20 patients with chronic HCV and advanced chronic kidney disease.

Disclosures: RUBY-1 was sponsored by AbbVie, which markets Viekira Pak. Dr. Pockros disclosed ties with AbbVie, Janssen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Merck, Conatus, and Roche Molecular.

Add vitamin E to NASH ‘toolkit’

VIENNA – Pooled analysis of data from three controlled trials provides further evidence to support the use of vitamin E in the treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH).

Daily vitamin E intake led to resolution of NASH in a higher percentage of patients than in those not treated with vitamin E (38% vs. 20%, P < .001). It also resulted in more patients achieving histologic improvement of NASH (45% vs. 22%, P < .0001).

“The magnitude of the effect of vitamin E on NASH was comparable to pioglitazone, metformin, and obeticholic acid,” Dr. Kris Kowdley of the Swedish Medical Center, Seattle, said in an interview at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

The odds ratio (OR) for the resolution of NASH for vitamin E versus no vitamin E was 2.4, (P < .001) and ORs for the other anti-NASH treatments used in the trials were 3.4 for pioglitazone vs. placebo (P = .001), 1.8 for metformin vs. placebo (P = .24), and 1.8 for obeticholic acid vs. placebo (P = .13).

The respective ORs for histologic improvement for vitamin E and the other treatments were 2.9 (P < .0001), 4.1 (P = .0001), 2.7 (P = .02), and 3.1 (P = .0002).

The data combined for the analysis were derived from three controlled studies: PIVENS (Pioglitazone Versus Vitamin E versus Placebo for the Treatment of Nondiabetic Patients with Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis], TONIC (The Treatment of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Children), and FLINT (Farnesoid X Receptor Ligand Obeticholic Acid in NASH Treatment Trial).

In the phase III, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind PIVENS trial, vitamin E therapy was compared to pioglitazone and placebo in 247 nondiabetic adults (N. Engl. J. Med. 2010; 362:1675-85).

In the TONIC phase III, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 173 children with NASH but no diabetes were randomized to treatment with vitamin E, metformin, or placebo for 96 weeks.

In FLINT, a phase II, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial of obeticholic acid, vitamin E was allowed as a concomitant therapy, and 23% of placebo-treated patients took vitamin E at baseline.

Dr. Kowdley noted that natural (d-alpha-tocopherol) not synthetic vitamin E was used in all these trials and the dosage used was 800 IU once daily in the PIVENS trial, 400 IU twice daily in the TONIC trial, and 400-800 IU in the patients who received it in the placebo arm of the FLINT trial.

In total, the pooled analysis considered 347 participants of these trials of whom 155 had been treated with vitamin E and 192 had not.

Histologic improvement was defined as at least a 2-point improvement in NASH with no worsening of fibrosis. NASH resolution was determined by pre- and posttreatment biopsies.

How vitamin E might be exerting its effect is not clear, Dr. Kowdley said. “We know that from the PIVENS trial it does not affect insulin sensitivity, and so presumably it has an antioxidant effect,” he speculated. Combination with other anti-NASH treatments, such as obeticholic acid, could produce synergistic effects perhaps, he acknowledged, but that would require further study.

“Vitamin E appears to be safe in this short-term study,” Dr. Kowdley said. Safety measures included the incidence of cardiac events and changes in lipid levels. However, there was no increased incidence in cardiovascular events with vitamin E use compared to no vitamin E use (6.9% vs. 7.6%, P =.85). There were also no significant differences in net changes in total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, or triglycerides.

Although it was not shown in the late-breaking poster, Dr. Kowdley said that vitamin E appeared to improve NASH in diabetic as well as in nondiabetic subjects with no increased risk of cardiovascular events as other studies have suggested.

“It’s a pooled analysis,” Dr. Kowdley acknowledged, “but we conclude that vitamin E was significantly associated with histologic improvement, reduction in NASH activity score and resolution of NASH, with an effect size that seems in the ballpark of the other therapies.

“So I think this suggests that vitamin E should be our toolkit for treatment of NASH,” he added.

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases sponsored the studies. Dr. Kowdley had no relevant conflicts of interest to disclosure.

VIENNA – Pooled analysis of data from three controlled trials provides further evidence to support the use of vitamin E in the treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH).

Daily vitamin E intake led to resolution of NASH in a higher percentage of patients than in those not treated with vitamin E (38% vs. 20%, P < .001). It also resulted in more patients achieving histologic improvement of NASH (45% vs. 22%, P < .0001).

“The magnitude of the effect of vitamin E on NASH was comparable to pioglitazone, metformin, and obeticholic acid,” Dr. Kris Kowdley of the Swedish Medical Center, Seattle, said in an interview at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

The odds ratio (OR) for the resolution of NASH for vitamin E versus no vitamin E was 2.4, (P < .001) and ORs for the other anti-NASH treatments used in the trials were 3.4 for pioglitazone vs. placebo (P = .001), 1.8 for metformin vs. placebo (P = .24), and 1.8 for obeticholic acid vs. placebo (P = .13).

The respective ORs for histologic improvement for vitamin E and the other treatments were 2.9 (P < .0001), 4.1 (P = .0001), 2.7 (P = .02), and 3.1 (P = .0002).

The data combined for the analysis were derived from three controlled studies: PIVENS (Pioglitazone Versus Vitamin E versus Placebo for the Treatment of Nondiabetic Patients with Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis], TONIC (The Treatment of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Children), and FLINT (Farnesoid X Receptor Ligand Obeticholic Acid in NASH Treatment Trial).

In the phase III, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind PIVENS trial, vitamin E therapy was compared to pioglitazone and placebo in 247 nondiabetic adults (N. Engl. J. Med. 2010; 362:1675-85).

In the TONIC phase III, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 173 children with NASH but no diabetes were randomized to treatment with vitamin E, metformin, or placebo for 96 weeks.

In FLINT, a phase II, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial of obeticholic acid, vitamin E was allowed as a concomitant therapy, and 23% of placebo-treated patients took vitamin E at baseline.

Dr. Kowdley noted that natural (d-alpha-tocopherol) not synthetic vitamin E was used in all these trials and the dosage used was 800 IU once daily in the PIVENS trial, 400 IU twice daily in the TONIC trial, and 400-800 IU in the patients who received it in the placebo arm of the FLINT trial.

In total, the pooled analysis considered 347 participants of these trials of whom 155 had been treated with vitamin E and 192 had not.

Histologic improvement was defined as at least a 2-point improvement in NASH with no worsening of fibrosis. NASH resolution was determined by pre- and posttreatment biopsies.

How vitamin E might be exerting its effect is not clear, Dr. Kowdley said. “We know that from the PIVENS trial it does not affect insulin sensitivity, and so presumably it has an antioxidant effect,” he speculated. Combination with other anti-NASH treatments, such as obeticholic acid, could produce synergistic effects perhaps, he acknowledged, but that would require further study.

“Vitamin E appears to be safe in this short-term study,” Dr. Kowdley said. Safety measures included the incidence of cardiac events and changes in lipid levels. However, there was no increased incidence in cardiovascular events with vitamin E use compared to no vitamin E use (6.9% vs. 7.6%, P =.85). There were also no significant differences in net changes in total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, or triglycerides.

Although it was not shown in the late-breaking poster, Dr. Kowdley said that vitamin E appeared to improve NASH in diabetic as well as in nondiabetic subjects with no increased risk of cardiovascular events as other studies have suggested.

“It’s a pooled analysis,” Dr. Kowdley acknowledged, “but we conclude that vitamin E was significantly associated with histologic improvement, reduction in NASH activity score and resolution of NASH, with an effect size that seems in the ballpark of the other therapies.

“So I think this suggests that vitamin E should be our toolkit for treatment of NASH,” he added.

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases sponsored the studies. Dr. Kowdley had no relevant conflicts of interest to disclosure.

VIENNA – Pooled analysis of data from three controlled trials provides further evidence to support the use of vitamin E in the treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH).

Daily vitamin E intake led to resolution of NASH in a higher percentage of patients than in those not treated with vitamin E (38% vs. 20%, P < .001). It also resulted in more patients achieving histologic improvement of NASH (45% vs. 22%, P < .0001).

“The magnitude of the effect of vitamin E on NASH was comparable to pioglitazone, metformin, and obeticholic acid,” Dr. Kris Kowdley of the Swedish Medical Center, Seattle, said in an interview at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

The odds ratio (OR) for the resolution of NASH for vitamin E versus no vitamin E was 2.4, (P < .001) and ORs for the other anti-NASH treatments used in the trials were 3.4 for pioglitazone vs. placebo (P = .001), 1.8 for metformin vs. placebo (P = .24), and 1.8 for obeticholic acid vs. placebo (P = .13).

The respective ORs for histologic improvement for vitamin E and the other treatments were 2.9 (P < .0001), 4.1 (P = .0001), 2.7 (P = .02), and 3.1 (P = .0002).

The data combined for the analysis were derived from three controlled studies: PIVENS (Pioglitazone Versus Vitamin E versus Placebo for the Treatment of Nondiabetic Patients with Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis], TONIC (The Treatment of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Children), and FLINT (Farnesoid X Receptor Ligand Obeticholic Acid in NASH Treatment Trial).

In the phase III, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind PIVENS trial, vitamin E therapy was compared to pioglitazone and placebo in 247 nondiabetic adults (N. Engl. J. Med. 2010; 362:1675-85).

In the TONIC phase III, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 173 children with NASH but no diabetes were randomized to treatment with vitamin E, metformin, or placebo for 96 weeks.

In FLINT, a phase II, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial of obeticholic acid, vitamin E was allowed as a concomitant therapy, and 23% of placebo-treated patients took vitamin E at baseline.

Dr. Kowdley noted that natural (d-alpha-tocopherol) not synthetic vitamin E was used in all these trials and the dosage used was 800 IU once daily in the PIVENS trial, 400 IU twice daily in the TONIC trial, and 400-800 IU in the patients who received it in the placebo arm of the FLINT trial.

In total, the pooled analysis considered 347 participants of these trials of whom 155 had been treated with vitamin E and 192 had not.

Histologic improvement was defined as at least a 2-point improvement in NASH with no worsening of fibrosis. NASH resolution was determined by pre- and posttreatment biopsies.

How vitamin E might be exerting its effect is not clear, Dr. Kowdley said. “We know that from the PIVENS trial it does not affect insulin sensitivity, and so presumably it has an antioxidant effect,” he speculated. Combination with other anti-NASH treatments, such as obeticholic acid, could produce synergistic effects perhaps, he acknowledged, but that would require further study.

“Vitamin E appears to be safe in this short-term study,” Dr. Kowdley said. Safety measures included the incidence of cardiac events and changes in lipid levels. However, there was no increased incidence in cardiovascular events with vitamin E use compared to no vitamin E use (6.9% vs. 7.6%, P =.85). There were also no significant differences in net changes in total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, or triglycerides.

Although it was not shown in the late-breaking poster, Dr. Kowdley said that vitamin E appeared to improve NASH in diabetic as well as in nondiabetic subjects with no increased risk of cardiovascular events as other studies have suggested.

“It’s a pooled analysis,” Dr. Kowdley acknowledged, “but we conclude that vitamin E was significantly associated with histologic improvement, reduction in NASH activity score and resolution of NASH, with an effect size that seems in the ballpark of the other therapies.

“So I think this suggests that vitamin E should be our toolkit for treatment of NASH,” he added.

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases sponsored the studies. Dr. Kowdley had no relevant conflicts of interest to disclosure.

AT THE INTERNATIONAL LIVER CONGRESS 2015

Key clinical point: Vitamin E was shown to improve nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) to an extent similar to those of pioglitazone, metformin, and obeticholic acid.

Major finding: The odds ratio (OR) for the resolution of NASH was 2.4 (P < .001) and the OR for histologic improvement was 2.9 (P < .0001), comparing vitamin E to no vitamin E therapy.

Data source: Pooled analysis of data on vitamin E use in 347 adults and children with NASH from three controlled trials: PIVENS, TONIC, and FLINT.

Disclosures: The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases sponsored the studies. Dr. Kowdley had no conflicts of interest to disclosure.

Europe Issues Hepatitis C Treatment Priority List

VIENNA – The new European recommendations for diagnosing and treating hepatitis C infection highlight the paradox gripping the field: Safe and potent antiviral drugs are available to cure most patients after 12 weeks of treatment, but cure is not broadly available because the agents are prohibitively expensive.

“Virtually everyone infected by hepatitis C virus [HCV] has the right to be treated,“ Dr. Jean-Michel Pawlotsky said during a session at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) that introduced the association’s new hepatitis C treatment recommendations.

The recommendations, released online around the time of the meeting, say: “Because of the approval of highly efficacious new HCV treatment regimens, access to therapy must be broadened.” In addition, they call for expanded screening to find more of the many unidentified cases of chronic hepatitis C infection (J. Hepatology 2015 [doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2015.03.025]). “However, we also have to acknowledge the reality that these drugs are currently too expensive, and the huge number of patients with HCV infection makes it impossible that we could treat all infected patients over the next couple of years,” said Dr. Pawlotsky, head of the department of virology at the Henri Mondor University Hospital in Créteil, France.

The prioritization scheme the EASL panel published gives highest treatment priority to patients with F3 or F4 liver fibrosis on the Metavir scoring system, HIV- or hepatitis B virus–coinfected patients, liver transplant candidates or recent recipients, and patients with significant extrahepatic manifestations, debilitating fatigue, or a high risk for transmitting infection. The list puts patients with moderate liver fibrosis, with a Metavir score of F2, a step down in priority but still rates them candidates for treatment. But the prioritization table rates patients with F1 or F0 fibrosis and none of the other stated complications as reasonable for deferred treatment.

This approach, as well as the general scheme recommended for drug selection, is “remarkably similar” to the guidance first issued and then revised last year by experts assembled by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America, commented Dr. Donald M. Jensen, a hepatologist in Oak Park, Ill., who helped draft the U.S. guidance. “The more these two guidelines are consistent, the more powerful they are,” Dr. Jensen said as an invited discussant at the session.

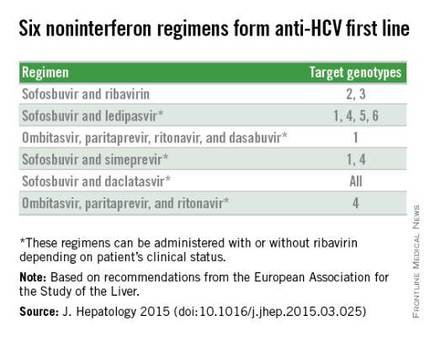

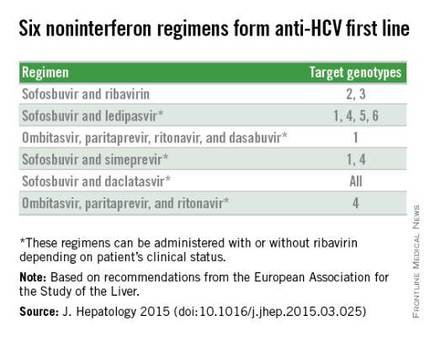

Perhaps the biggest difference between the HCV treatment recommendations from the European and American groups is that the EASL document included daclatasvir (Daklinza), a direct-acting antiviral for HCV that became available for use in Europe in 2014, but which remains under Food and Drug Administration review for U.S. use as of May 2015.

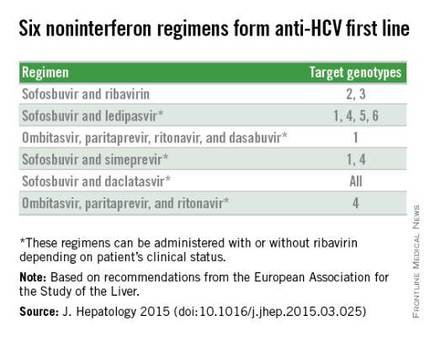

With daclatasvir as an option, the EASL panel highlighted six HCV regimens as first-line HCV options that all avoid treatment with interferon. The recommendations further fine-tune the options from this list of six regimens depending on the infecting HCV genotype, as well as special clinical situations such as compensated or decompensated cirrhosis, recent liver transplant, or end-stage renal disease. The EASL panel also firmly relegated interferon-containing regimens to second-line status.

Another significant issue in choosing among HCV treatments are drug-drug interactions. The EASL panel endorsed a website maintained by the University of Liverpool (England) as an excellent source for researching drug-interaction issues, Dr. Pawlotsky said.

VIENNA – The new European recommendations for diagnosing and treating hepatitis C infection highlight the paradox gripping the field: Safe and potent antiviral drugs are available to cure most patients after 12 weeks of treatment, but cure is not broadly available because the agents are prohibitively expensive.

“Virtually everyone infected by hepatitis C virus [HCV] has the right to be treated,“ Dr. Jean-Michel Pawlotsky said during a session at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) that introduced the association’s new hepatitis C treatment recommendations.

The recommendations, released online around the time of the meeting, say: “Because of the approval of highly efficacious new HCV treatment regimens, access to therapy must be broadened.” In addition, they call for expanded screening to find more of the many unidentified cases of chronic hepatitis C infection (J. Hepatology 2015 [doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2015.03.025]). “However, we also have to acknowledge the reality that these drugs are currently too expensive, and the huge number of patients with HCV infection makes it impossible that we could treat all infected patients over the next couple of years,” said Dr. Pawlotsky, head of the department of virology at the Henri Mondor University Hospital in Créteil, France.