User login

Chaplains play important part of integrated palliative care

WASHINGTON – Hospital chaplains are key partners in meeting the needs of palliative care patients and, as such, have much to offer psychiatry, according to an expert.

“I think we should work with chaplains,” Dr. Laura B. Dunn, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford (Calif.) University, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry. “It’s very helpful to know what they do, and for them to know what we do in terms of diagnosing and using a biopsychosocial model.”

Dr. Dunn said the relegation of chaplaincy and spiritual care in medicine has been unfortunate. After all, the level of a patient’s spiritual health is an inherent aspect of quality of life in palliative care, particularly for those over age 60 who often want help reconciling with loved ones, data collected by Dr. Dunn show. Viewing those patients in terms of their core needs rather than seeking a psychiatric diagnosis can make them more satisfied with their overall palliative care experience, she said.

How is spiritual health measured? There are few models and even fewer empirical studies, but Dr. Dunn said in addition learning how to deliver pastoral care, professional chaplains are trained to assess, intervene, and observe outcomes in spiritual health.

To begin with, spirituality is defined not in terms of “religiosity” but more as following an ethical path, similar to the idea of the Golden Rule or the ethic of reciprocity: Love your neighbor as yourself, in other words. The spiritual maturity to follow such a path requires the ability to love oneself that is balanced with a connection to others, and God, “if your belief includes God,” said Dr. Dunn, who pointed out that chaplaincy programs for atheists also exist.

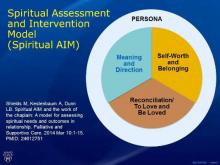

By observing a person’s behavior and conversing with him or her, paying close attention to the person’s attributions of blame, if any, and expressions of chief concerns, a chaplain will assess where on the continuum that person is in three key components of spiritual health: the need for meaning and direction, a sense of self-worth and belonging, and an ability to love and be loved. This latter component often is facilitated through seeking reconciliation when relationships are broken.

In the face of crisis, such as with terminal illness, one of those needs typically supersedes the others. This is what is known as the person’s “core spiritual need,” said Dr. Dunn, who also serves director of the university’s Geriatric Psychiatry Fellowship Training Program, and has extensive research and clinical experience evaluating and managing older adults with mood, anxiety, and cognitive disorders. As part of her research, she and her colleagues have developed a schematic called the Spiritual AIM (Spiritual Assessment and Intervention Model), which depicts those three concerns in relation to one another (Palliat Support Care. 2015 Feb;13:75-89).

Chaplains also are trained to rely on their own feelings about people, similar to the way in which psychiatrists use countertransference. “It is not intrapersonal; it is interpersonal,” Dr. Dunn said. “Healing happens in relationship, and the focus is on that relationship.”

Chaplains undergo standardized clinical pastoral training programs predicated on a combination of theological reflection and psychological theory, plus critique from professional peers and students.

“Their model is very similar to what we [geriatric psychiatrists] do when we assess a patient,” Dr. Dunn said. “We might be more structured trying to ferret out a diagnosis, but we’re assessing all the time.”

Depending on which aspect of spiritual health is most lacking, the chaplain will choose the role of either a “guide” to help with balancing the need for meaning and direction, a “valuer” to help restore feelings of worth and belonging, or a “truth-teller” who will explore with the patient ways he or she might have contributed to broken relationships, and actions the patient might take in order to heal them. This is all done within the context of an interdisciplinary team, Dr. Dunn said.

She and a team of researchers, including a chaplain, conducted a study of 31 advanced-stage adult cancer patients in an outpatient palliative care service, that measured self-reported changes in their spiritual, psychological, and physical symptoms both before and after Spiritual AIM sessions with a chaplain.

The need for balancing one of the three key components of spiritual health was determined by the chaplain to be fairly equal across the cohort, although just more than half of patients younger than 60 years of age struggled more with self-worth and belonging (P = .030). Those over 60 years were equally concerned with either reconciliation or meaning and direction (P less than .05). Two-thirds of the cohort were women, although a relationship between gender and spiritual assessment needs was not determined. Two-thirds also identified themselves as Christian, just over one-third were Jewish, and the rest identified as either Buddhist or nondenominational.

Using a variety of validated palliative care scales, such as the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Syndrome (ESAS) for physical complaints, the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Short Depression Scale, the Mini Mental Adjustment to Cancer scale (Mini-MAC), and the positive and negative RCOPE questionnaire for religious coping, among other scales, Dr. Dunn and her associates found that the change in baseline of overall spiritual health after intervention from the chaplain improved slightly in most measures. Mean baseline scores for the ESAS went from 25 to 24.4 post-intervention. The difference between baseline depression scores fell from 4.2 to 4.1.

Mini-MAC scores improved, particularly in “fighting spirit” and levels of fatalism (P = .084 and P = .036, respectively). In addition, maladaptive coping skills also improved (P = .018).The findings have helped Dr. Dunn in her work as a geriatric psychiatrist, especially when treating cancer patients, or in settings where there is not as much time for a full clinical assessment. “I think of patients in terms of their core needs and what I can do right now to help patients meet those needs.” Dr. Dunn cited, as an example, patients who feel like they don’t belong and are lonely. “If they’re in an assisted living home, can I get them to enter [the communal space]? That’s very different than thinking of them in terms only of depression.”

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

One reason chaplains are such a key part of the palliative care team is that they are seen by patients from a different perspective, Dr. Gurprit S. Lamba said. “Chaplains lend their ears, act as friends, and provide company to these patients,” Dr. Lamba said in an interview. “Discussing spiritual/religious matters helps these individuals cope better. Chaplains can provide more meaningful services with knowledge about different cultures, doctrines, and traditions, so that they can tailor their meetings accordingly.

“Studies have shown that psychiatrists are less religious and show less religious affiliation than their patients and than the population in general. As Dr. Dunn mentioned, chaplaincy programs for atheists also exist. Psychiatrists, with chaplains, can work with any individual to improve and optimize treatment. The critical part lies in assessment of patients’ religious views and spirituality along with their families’ opinions before offering meeting with chaplains.”

Dr. Lamba is a geriatric psychiatrist affiliated with BayRidge Hospital in Lynn, Mass.

One reason chaplains are such a key part of the palliative care team is that they are seen by patients from a different perspective, Dr. Gurprit S. Lamba said. “Chaplains lend their ears, act as friends, and provide company to these patients,” Dr. Lamba said in an interview. “Discussing spiritual/religious matters helps these individuals cope better. Chaplains can provide more meaningful services with knowledge about different cultures, doctrines, and traditions, so that they can tailor their meetings accordingly.

“Studies have shown that psychiatrists are less religious and show less religious affiliation than their patients and than the population in general. As Dr. Dunn mentioned, chaplaincy programs for atheists also exist. Psychiatrists, with chaplains, can work with any individual to improve and optimize treatment. The critical part lies in assessment of patients’ religious views and spirituality along with their families’ opinions before offering meeting with chaplains.”

Dr. Lamba is a geriatric psychiatrist affiliated with BayRidge Hospital in Lynn, Mass.

One reason chaplains are such a key part of the palliative care team is that they are seen by patients from a different perspective, Dr. Gurprit S. Lamba said. “Chaplains lend their ears, act as friends, and provide company to these patients,” Dr. Lamba said in an interview. “Discussing spiritual/religious matters helps these individuals cope better. Chaplains can provide more meaningful services with knowledge about different cultures, doctrines, and traditions, so that they can tailor their meetings accordingly.

“Studies have shown that psychiatrists are less religious and show less religious affiliation than their patients and than the population in general. As Dr. Dunn mentioned, chaplaincy programs for atheists also exist. Psychiatrists, with chaplains, can work with any individual to improve and optimize treatment. The critical part lies in assessment of patients’ religious views and spirituality along with their families’ opinions before offering meeting with chaplains.”

Dr. Lamba is a geriatric psychiatrist affiliated with BayRidge Hospital in Lynn, Mass.

WASHINGTON – Hospital chaplains are key partners in meeting the needs of palliative care patients and, as such, have much to offer psychiatry, according to an expert.

“I think we should work with chaplains,” Dr. Laura B. Dunn, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford (Calif.) University, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry. “It’s very helpful to know what they do, and for them to know what we do in terms of diagnosing and using a biopsychosocial model.”

Dr. Dunn said the relegation of chaplaincy and spiritual care in medicine has been unfortunate. After all, the level of a patient’s spiritual health is an inherent aspect of quality of life in palliative care, particularly for those over age 60 who often want help reconciling with loved ones, data collected by Dr. Dunn show. Viewing those patients in terms of their core needs rather than seeking a psychiatric diagnosis can make them more satisfied with their overall palliative care experience, she said.

How is spiritual health measured? There are few models and even fewer empirical studies, but Dr. Dunn said in addition learning how to deliver pastoral care, professional chaplains are trained to assess, intervene, and observe outcomes in spiritual health.

To begin with, spirituality is defined not in terms of “religiosity” but more as following an ethical path, similar to the idea of the Golden Rule or the ethic of reciprocity: Love your neighbor as yourself, in other words. The spiritual maturity to follow such a path requires the ability to love oneself that is balanced with a connection to others, and God, “if your belief includes God,” said Dr. Dunn, who pointed out that chaplaincy programs for atheists also exist.

By observing a person’s behavior and conversing with him or her, paying close attention to the person’s attributions of blame, if any, and expressions of chief concerns, a chaplain will assess where on the continuum that person is in three key components of spiritual health: the need for meaning and direction, a sense of self-worth and belonging, and an ability to love and be loved. This latter component often is facilitated through seeking reconciliation when relationships are broken.

In the face of crisis, such as with terminal illness, one of those needs typically supersedes the others. This is what is known as the person’s “core spiritual need,” said Dr. Dunn, who also serves director of the university’s Geriatric Psychiatry Fellowship Training Program, and has extensive research and clinical experience evaluating and managing older adults with mood, anxiety, and cognitive disorders. As part of her research, she and her colleagues have developed a schematic called the Spiritual AIM (Spiritual Assessment and Intervention Model), which depicts those three concerns in relation to one another (Palliat Support Care. 2015 Feb;13:75-89).

Chaplains also are trained to rely on their own feelings about people, similar to the way in which psychiatrists use countertransference. “It is not intrapersonal; it is interpersonal,” Dr. Dunn said. “Healing happens in relationship, and the focus is on that relationship.”

Chaplains undergo standardized clinical pastoral training programs predicated on a combination of theological reflection and psychological theory, plus critique from professional peers and students.

“Their model is very similar to what we [geriatric psychiatrists] do when we assess a patient,” Dr. Dunn said. “We might be more structured trying to ferret out a diagnosis, but we’re assessing all the time.”

Depending on which aspect of spiritual health is most lacking, the chaplain will choose the role of either a “guide” to help with balancing the need for meaning and direction, a “valuer” to help restore feelings of worth and belonging, or a “truth-teller” who will explore with the patient ways he or she might have contributed to broken relationships, and actions the patient might take in order to heal them. This is all done within the context of an interdisciplinary team, Dr. Dunn said.

She and a team of researchers, including a chaplain, conducted a study of 31 advanced-stage adult cancer patients in an outpatient palliative care service, that measured self-reported changes in their spiritual, psychological, and physical symptoms both before and after Spiritual AIM sessions with a chaplain.

The need for balancing one of the three key components of spiritual health was determined by the chaplain to be fairly equal across the cohort, although just more than half of patients younger than 60 years of age struggled more with self-worth and belonging (P = .030). Those over 60 years were equally concerned with either reconciliation or meaning and direction (P less than .05). Two-thirds of the cohort were women, although a relationship between gender and spiritual assessment needs was not determined. Two-thirds also identified themselves as Christian, just over one-third were Jewish, and the rest identified as either Buddhist or nondenominational.

Using a variety of validated palliative care scales, such as the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Syndrome (ESAS) for physical complaints, the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Short Depression Scale, the Mini Mental Adjustment to Cancer scale (Mini-MAC), and the positive and negative RCOPE questionnaire for religious coping, among other scales, Dr. Dunn and her associates found that the change in baseline of overall spiritual health after intervention from the chaplain improved slightly in most measures. Mean baseline scores for the ESAS went from 25 to 24.4 post-intervention. The difference between baseline depression scores fell from 4.2 to 4.1.

Mini-MAC scores improved, particularly in “fighting spirit” and levels of fatalism (P = .084 and P = .036, respectively). In addition, maladaptive coping skills also improved (P = .018).The findings have helped Dr. Dunn in her work as a geriatric psychiatrist, especially when treating cancer patients, or in settings where there is not as much time for a full clinical assessment. “I think of patients in terms of their core needs and what I can do right now to help patients meet those needs.” Dr. Dunn cited, as an example, patients who feel like they don’t belong and are lonely. “If they’re in an assisted living home, can I get them to enter [the communal space]? That’s very different than thinking of them in terms only of depression.”

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

WASHINGTON – Hospital chaplains are key partners in meeting the needs of palliative care patients and, as such, have much to offer psychiatry, according to an expert.

“I think we should work with chaplains,” Dr. Laura B. Dunn, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford (Calif.) University, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry. “It’s very helpful to know what they do, and for them to know what we do in terms of diagnosing and using a biopsychosocial model.”

Dr. Dunn said the relegation of chaplaincy and spiritual care in medicine has been unfortunate. After all, the level of a patient’s spiritual health is an inherent aspect of quality of life in palliative care, particularly for those over age 60 who often want help reconciling with loved ones, data collected by Dr. Dunn show. Viewing those patients in terms of their core needs rather than seeking a psychiatric diagnosis can make them more satisfied with their overall palliative care experience, she said.

How is spiritual health measured? There are few models and even fewer empirical studies, but Dr. Dunn said in addition learning how to deliver pastoral care, professional chaplains are trained to assess, intervene, and observe outcomes in spiritual health.

To begin with, spirituality is defined not in terms of “religiosity” but more as following an ethical path, similar to the idea of the Golden Rule or the ethic of reciprocity: Love your neighbor as yourself, in other words. The spiritual maturity to follow such a path requires the ability to love oneself that is balanced with a connection to others, and God, “if your belief includes God,” said Dr. Dunn, who pointed out that chaplaincy programs for atheists also exist.

By observing a person’s behavior and conversing with him or her, paying close attention to the person’s attributions of blame, if any, and expressions of chief concerns, a chaplain will assess where on the continuum that person is in three key components of spiritual health: the need for meaning and direction, a sense of self-worth and belonging, and an ability to love and be loved. This latter component often is facilitated through seeking reconciliation when relationships are broken.

In the face of crisis, such as with terminal illness, one of those needs typically supersedes the others. This is what is known as the person’s “core spiritual need,” said Dr. Dunn, who also serves director of the university’s Geriatric Psychiatry Fellowship Training Program, and has extensive research and clinical experience evaluating and managing older adults with mood, anxiety, and cognitive disorders. As part of her research, she and her colleagues have developed a schematic called the Spiritual AIM (Spiritual Assessment and Intervention Model), which depicts those three concerns in relation to one another (Palliat Support Care. 2015 Feb;13:75-89).

Chaplains also are trained to rely on their own feelings about people, similar to the way in which psychiatrists use countertransference. “It is not intrapersonal; it is interpersonal,” Dr. Dunn said. “Healing happens in relationship, and the focus is on that relationship.”

Chaplains undergo standardized clinical pastoral training programs predicated on a combination of theological reflection and psychological theory, plus critique from professional peers and students.

“Their model is very similar to what we [geriatric psychiatrists] do when we assess a patient,” Dr. Dunn said. “We might be more structured trying to ferret out a diagnosis, but we’re assessing all the time.”

Depending on which aspect of spiritual health is most lacking, the chaplain will choose the role of either a “guide” to help with balancing the need for meaning and direction, a “valuer” to help restore feelings of worth and belonging, or a “truth-teller” who will explore with the patient ways he or she might have contributed to broken relationships, and actions the patient might take in order to heal them. This is all done within the context of an interdisciplinary team, Dr. Dunn said.

She and a team of researchers, including a chaplain, conducted a study of 31 advanced-stage adult cancer patients in an outpatient palliative care service, that measured self-reported changes in their spiritual, psychological, and physical symptoms both before and after Spiritual AIM sessions with a chaplain.

The need for balancing one of the three key components of spiritual health was determined by the chaplain to be fairly equal across the cohort, although just more than half of patients younger than 60 years of age struggled more with self-worth and belonging (P = .030). Those over 60 years were equally concerned with either reconciliation or meaning and direction (P less than .05). Two-thirds of the cohort were women, although a relationship between gender and spiritual assessment needs was not determined. Two-thirds also identified themselves as Christian, just over one-third were Jewish, and the rest identified as either Buddhist or nondenominational.

Using a variety of validated palliative care scales, such as the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Syndrome (ESAS) for physical complaints, the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Short Depression Scale, the Mini Mental Adjustment to Cancer scale (Mini-MAC), and the positive and negative RCOPE questionnaire for religious coping, among other scales, Dr. Dunn and her associates found that the change in baseline of overall spiritual health after intervention from the chaplain improved slightly in most measures. Mean baseline scores for the ESAS went from 25 to 24.4 post-intervention. The difference between baseline depression scores fell from 4.2 to 4.1.

Mini-MAC scores improved, particularly in “fighting spirit” and levels of fatalism (P = .084 and P = .036, respectively). In addition, maladaptive coping skills also improved (P = .018).The findings have helped Dr. Dunn in her work as a geriatric psychiatrist, especially when treating cancer patients, or in settings where there is not as much time for a full clinical assessment. “I think of patients in terms of their core needs and what I can do right now to help patients meet those needs.” Dr. Dunn cited, as an example, patients who feel like they don’t belong and are lonely. “If they’re in an assisted living home, can I get them to enter [the communal space]? That’s very different than thinking of them in terms only of depression.”

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AAGP 2016

Higher levels of function before hip fracture tied to greater fears of falling at 1 year

WASHINGTON – Fear of falling at 12 weeks was associated with poorer functional recovery up to 1 year after hip fracture, particularly if the person had a high level of function before the fracture, a study has shown.

Inherent in this fear is a tendency of the patient to limit his activities, which in turn affects his sense of balance, visual attention, and gait. This leads to an increased risk of further falls, according to Emily Bower, a doctoral candidate who presented the findings at the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry.

The study included 241 hip fracture patients, three-quarters of whom were female, with an average age of 77 years. All of the patients lived in the community, nearly all were able to participate in basic activities of daily living, and three-quarters could walk without assistance.

Patients were assessed for their level of functionality at week 4, week 12, week 26, and week 52, as well as their fear of falling using the Falls Efficacy Scale International (FES-I).

The investigators found that by week 52, 48% of all patients had reached full recovery of functional status. At week 12, 53% of all patients had FES-I scores indicating a lower fear of falling.

“That means that almost half of our participants were reporting high fear of falling 3 months after hip fracture, which is a substantial number when you consider that in the general population, fear of falling is reported by about one in five older adults,” Ms. Bower, who is enrolled at the San Diego State University/University of California, San Diego, joint doctoral program in clinical psychology, said in an interview.

At 1-year after fracture, for each 1 point increase in FES-I scores, the odds of reaching full recovery were lowered by 12% (P = .003). Meanwhile, in patients with low baseline levels of functioning, there was “no effect of fear of falling,” according to Ms. Bower.

The upshot is that for patients with high levels of functional independence prior to injury, more intervention may be required to bring them back to their levels of activity before the fracture, according to Ms. Bower, who suggested multicomponent activities that combine psychological, physical, and environmental factors, such as tai chi.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

WASHINGTON – Fear of falling at 12 weeks was associated with poorer functional recovery up to 1 year after hip fracture, particularly if the person had a high level of function before the fracture, a study has shown.

Inherent in this fear is a tendency of the patient to limit his activities, which in turn affects his sense of balance, visual attention, and gait. This leads to an increased risk of further falls, according to Emily Bower, a doctoral candidate who presented the findings at the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry.

The study included 241 hip fracture patients, three-quarters of whom were female, with an average age of 77 years. All of the patients lived in the community, nearly all were able to participate in basic activities of daily living, and three-quarters could walk without assistance.

Patients were assessed for their level of functionality at week 4, week 12, week 26, and week 52, as well as their fear of falling using the Falls Efficacy Scale International (FES-I).

The investigators found that by week 52, 48% of all patients had reached full recovery of functional status. At week 12, 53% of all patients had FES-I scores indicating a lower fear of falling.

“That means that almost half of our participants were reporting high fear of falling 3 months after hip fracture, which is a substantial number when you consider that in the general population, fear of falling is reported by about one in five older adults,” Ms. Bower, who is enrolled at the San Diego State University/University of California, San Diego, joint doctoral program in clinical psychology, said in an interview.

At 1-year after fracture, for each 1 point increase in FES-I scores, the odds of reaching full recovery were lowered by 12% (P = .003). Meanwhile, in patients with low baseline levels of functioning, there was “no effect of fear of falling,” according to Ms. Bower.

The upshot is that for patients with high levels of functional independence prior to injury, more intervention may be required to bring them back to their levels of activity before the fracture, according to Ms. Bower, who suggested multicomponent activities that combine psychological, physical, and environmental factors, such as tai chi.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

WASHINGTON – Fear of falling at 12 weeks was associated with poorer functional recovery up to 1 year after hip fracture, particularly if the person had a high level of function before the fracture, a study has shown.

Inherent in this fear is a tendency of the patient to limit his activities, which in turn affects his sense of balance, visual attention, and gait. This leads to an increased risk of further falls, according to Emily Bower, a doctoral candidate who presented the findings at the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry.

The study included 241 hip fracture patients, three-quarters of whom were female, with an average age of 77 years. All of the patients lived in the community, nearly all were able to participate in basic activities of daily living, and three-quarters could walk without assistance.

Patients were assessed for their level of functionality at week 4, week 12, week 26, and week 52, as well as their fear of falling using the Falls Efficacy Scale International (FES-I).

The investigators found that by week 52, 48% of all patients had reached full recovery of functional status. At week 12, 53% of all patients had FES-I scores indicating a lower fear of falling.

“That means that almost half of our participants were reporting high fear of falling 3 months after hip fracture, which is a substantial number when you consider that in the general population, fear of falling is reported by about one in five older adults,” Ms. Bower, who is enrolled at the San Diego State University/University of California, San Diego, joint doctoral program in clinical psychology, said in an interview.

At 1-year after fracture, for each 1 point increase in FES-I scores, the odds of reaching full recovery were lowered by 12% (P = .003). Meanwhile, in patients with low baseline levels of functioning, there was “no effect of fear of falling,” according to Ms. Bower.

The upshot is that for patients with high levels of functional independence prior to injury, more intervention may be required to bring them back to their levels of activity before the fracture, according to Ms. Bower, who suggested multicomponent activities that combine psychological, physical, and environmental factors, such as tai chi.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AAGP 2016