User login

American Heart Association (AHA): Scientific Sessions 2015

AHA: One in Three Black Americans Will Experience PAD

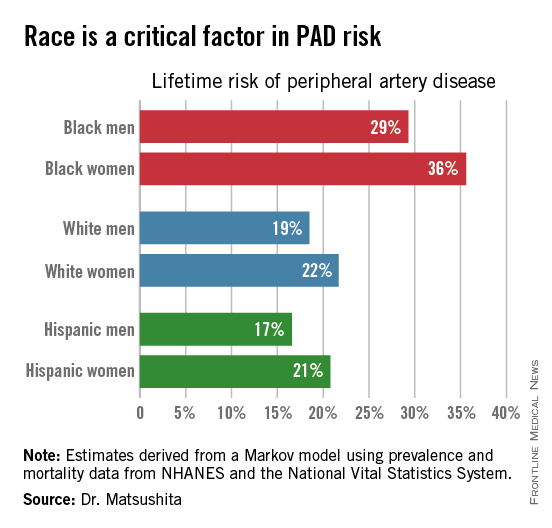

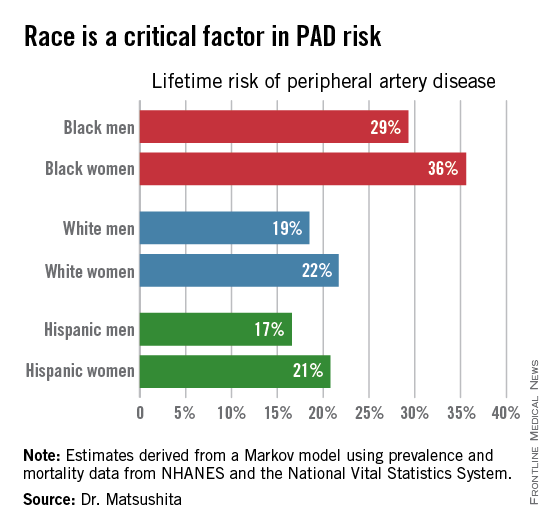

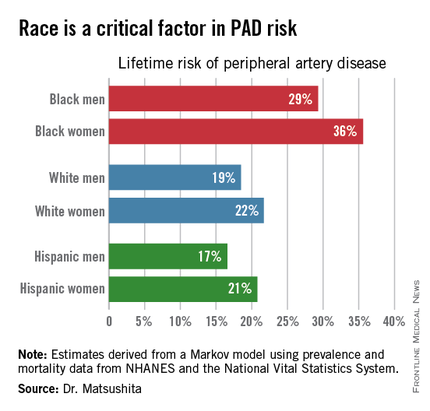

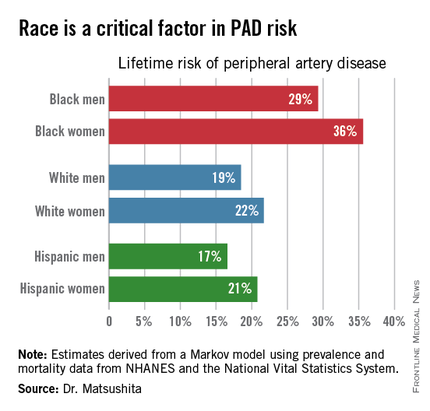

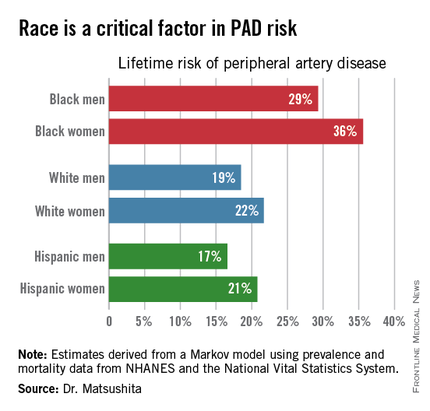

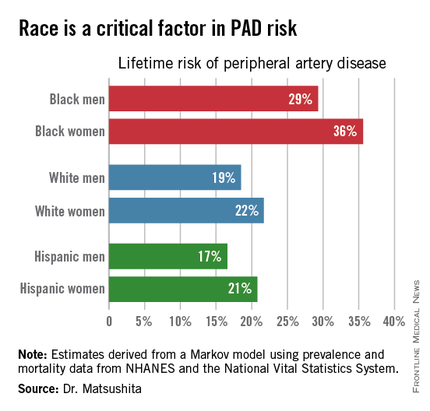

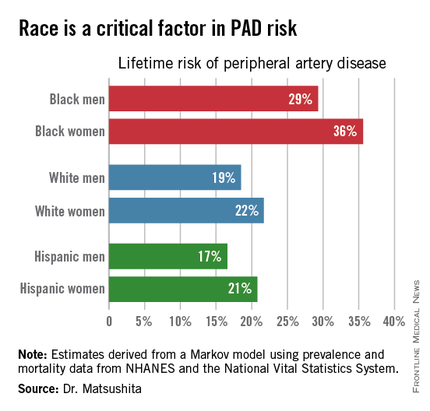

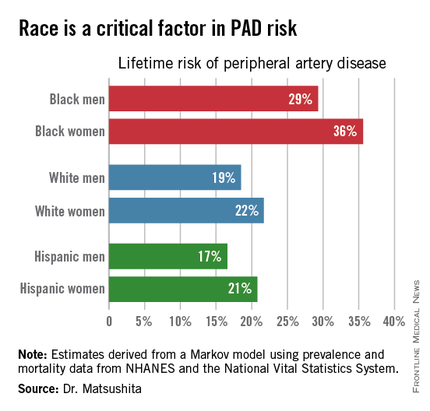

ORLANDO – One in three black Americans and one in five whites and Hispanics will develop lower extremity peripheral artery disease during their lifetime, according to the first-ever lifetime risk estimate calculated for this important manifestation of atherosclerotic vascular disease.

“Our results suggest that race is a critical factor in PAD [peripheral artery disease] risk. Current clinical guidelines recommend measuring ankle-brachial index according to age, traditional cardiovascular risk factors, and leg symptoms. Our results suggest race should also be taken into account,” Dr. Kunihiro Matsushita said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

This lifetime risk estimate for PAD was derived from national prevalence and mortality data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) and the National Vital Statistics System. The analytic methods employed have previously been used to estimate lifetime risk of kidney disease and other major health issues with significant impact upon quality of life and longevity, noted Dr. Matsushita of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Over an 80-year time horizon, the projected risk of experiencing PAD was similar for men and women of the same race, but 1.5-fold higher for blacks, compared with whites or Hispanics (see chart).

An estimated 10% of black Americans will develop PAD by age 60. Among whites and Hispanics, a 10% prevalence is not reached until age 70. For individuals who don’t have PAD by age 65, their risk during the next 15 years is in the range of 28%-30% for black men and women, and 16%-18% in white or Hispanic men and women, according to Dr. Matsushita.

He declared having no financial conflicts related to this study. His work is supported by an AHA award.

ORLANDO – One in three black Americans and one in five whites and Hispanics will develop lower extremity peripheral artery disease during their lifetime, according to the first-ever lifetime risk estimate calculated for this important manifestation of atherosclerotic vascular disease.

“Our results suggest that race is a critical factor in PAD [peripheral artery disease] risk. Current clinical guidelines recommend measuring ankle-brachial index according to age, traditional cardiovascular risk factors, and leg symptoms. Our results suggest race should also be taken into account,” Dr. Kunihiro Matsushita said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

This lifetime risk estimate for PAD was derived from national prevalence and mortality data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) and the National Vital Statistics System. The analytic methods employed have previously been used to estimate lifetime risk of kidney disease and other major health issues with significant impact upon quality of life and longevity, noted Dr. Matsushita of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Over an 80-year time horizon, the projected risk of experiencing PAD was similar for men and women of the same race, but 1.5-fold higher for blacks, compared with whites or Hispanics (see chart).

An estimated 10% of black Americans will develop PAD by age 60. Among whites and Hispanics, a 10% prevalence is not reached until age 70. For individuals who don’t have PAD by age 65, their risk during the next 15 years is in the range of 28%-30% for black men and women, and 16%-18% in white or Hispanic men and women, according to Dr. Matsushita.

He declared having no financial conflicts related to this study. His work is supported by an AHA award.

ORLANDO – One in three black Americans and one in five whites and Hispanics will develop lower extremity peripheral artery disease during their lifetime, according to the first-ever lifetime risk estimate calculated for this important manifestation of atherosclerotic vascular disease.

“Our results suggest that race is a critical factor in PAD [peripheral artery disease] risk. Current clinical guidelines recommend measuring ankle-brachial index according to age, traditional cardiovascular risk factors, and leg symptoms. Our results suggest race should also be taken into account,” Dr. Kunihiro Matsushita said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

This lifetime risk estimate for PAD was derived from national prevalence and mortality data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) and the National Vital Statistics System. The analytic methods employed have previously been used to estimate lifetime risk of kidney disease and other major health issues with significant impact upon quality of life and longevity, noted Dr. Matsushita of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Over an 80-year time horizon, the projected risk of experiencing PAD was similar for men and women of the same race, but 1.5-fold higher for blacks, compared with whites or Hispanics (see chart).

An estimated 10% of black Americans will develop PAD by age 60. Among whites and Hispanics, a 10% prevalence is not reached until age 70. For individuals who don’t have PAD by age 65, their risk during the next 15 years is in the range of 28%-30% for black men and women, and 16%-18% in white or Hispanic men and women, according to Dr. Matsushita.

He declared having no financial conflicts related to this study. His work is supported by an AHA award.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

AHA: One in three black Americans will experience PAD

ORLANDO – One in three black Americans and one in five whites and Hispanics will develop lower extremity peripheral artery disease during their lifetime, according to the first-ever lifetime risk estimate calculated for this important manifestation of atherosclerotic vascular disease.

“Our results suggest that race is a critical factor in PAD [peripheral artery disease] risk. Current clinical guidelines recommend measuring ankle-brachial index according to age, traditional cardiovascular risk factors, and leg symptoms. Our results suggest race should also be taken into account,” Dr. Kunihiro Matsushita said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

This lifetime risk estimate for PAD was derived from national prevalence and mortality data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) and the National Vital Statistics System. The analytic methods employed have previously been used to estimate lifetime risk of kidney disease and other major health issues with significant impact upon quality of life and longevity, noted Dr. Matsushita of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Over an 80-year time horizon, the projected risk of experiencing PAD was similar for men and women of the same race, but 1.5-fold higher for blacks, compared with whites or Hispanics (see chart).

An estimated 10% of black Americans will develop PAD by age 60. Among whites and Hispanics, a 10% prevalence is not reached until age 70. For individuals who don’t have PAD by age 65, their risk during the next 15 years is in the range of 28%-30% for black men and women, and 16%-18% in white or Hispanic men and women, according to Dr. Matsushita.

He declared having no financial conflicts related to this study. His work is supported by an AHA award.

ORLANDO – One in three black Americans and one in five whites and Hispanics will develop lower extremity peripheral artery disease during their lifetime, according to the first-ever lifetime risk estimate calculated for this important manifestation of atherosclerotic vascular disease.

“Our results suggest that race is a critical factor in PAD [peripheral artery disease] risk. Current clinical guidelines recommend measuring ankle-brachial index according to age, traditional cardiovascular risk factors, and leg symptoms. Our results suggest race should also be taken into account,” Dr. Kunihiro Matsushita said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

This lifetime risk estimate for PAD was derived from national prevalence and mortality data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) and the National Vital Statistics System. The analytic methods employed have previously been used to estimate lifetime risk of kidney disease and other major health issues with significant impact upon quality of life and longevity, noted Dr. Matsushita of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Over an 80-year time horizon, the projected risk of experiencing PAD was similar for men and women of the same race, but 1.5-fold higher for blacks, compared with whites or Hispanics (see chart).

An estimated 10% of black Americans will develop PAD by age 60. Among whites and Hispanics, a 10% prevalence is not reached until age 70. For individuals who don’t have PAD by age 65, their risk during the next 15 years is in the range of 28%-30% for black men and women, and 16%-18% in white or Hispanic men and women, according to Dr. Matsushita.

He declared having no financial conflicts related to this study. His work is supported by an AHA award.

ORLANDO – One in three black Americans and one in five whites and Hispanics will develop lower extremity peripheral artery disease during their lifetime, according to the first-ever lifetime risk estimate calculated for this important manifestation of atherosclerotic vascular disease.

“Our results suggest that race is a critical factor in PAD [peripheral artery disease] risk. Current clinical guidelines recommend measuring ankle-brachial index according to age, traditional cardiovascular risk factors, and leg symptoms. Our results suggest race should also be taken into account,” Dr. Kunihiro Matsushita said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

This lifetime risk estimate for PAD was derived from national prevalence and mortality data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) and the National Vital Statistics System. The analytic methods employed have previously been used to estimate lifetime risk of kidney disease and other major health issues with significant impact upon quality of life and longevity, noted Dr. Matsushita of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Over an 80-year time horizon, the projected risk of experiencing PAD was similar for men and women of the same race, but 1.5-fold higher for blacks, compared with whites or Hispanics (see chart).

An estimated 10% of black Americans will develop PAD by age 60. Among whites and Hispanics, a 10% prevalence is not reached until age 70. For individuals who don’t have PAD by age 65, their risk during the next 15 years is in the range of 28%-30% for black men and women, and 16%-18% in white or Hispanic men and women, according to Dr. Matsushita.

He declared having no financial conflicts related to this study. His work is supported by an AHA award.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: The threshold for screening for peripheral artery disease should be lower in black patients.

Major finding: One in three black Americans will develop peripheral artery disease by age 80, as will one in five whites or Hispanics.

Data source: This lifetime risk estimate for peripheral artery disease was derived from a Markov model with data input on the prevalence of the disorder and its associated mortality obtained from NHANES and the National Vital Statistics System.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts. His research is supported by an AHA award.

AHA: Should BP Targets Be Higher in Asymptomatic Aortic Stenosis?

ORLANDO – Optimal blood pressure in patients with asymptomatic mild to moderate aortic stenosis is 140-159 mm Hg for systolic and 70-89 mm Hg for diastolic, according to an analysis of all-cause mortality in the world’s largest data set of such patients with longitudinal follow-up and endpoint evaluation.

Within those target blood pressure ranges, the nadir in terms of all-cause mortality – and thus the true optimal blood pressure – is about 145/82 mm Hg, Dr. Kristian Wachtell reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

He presented an analysis of 1,873 asymptomatic patients with mild to moderate aortic stenosis (AS) and a peak aortic-jet velocity of 2.5-4.0 M/sec upon enrollment in the Simvastatin Ezetimibe in Aortic Stenosis (SEAS) trial. SEAS was a double-blind, multicenter study in which participants were randomized to 40 mg of simvastatin plus 10 mg of ezetimibe per day or placebo and followed for a mean of 4.3 years. Half of them had a history of hypertension at baseline.

As previously reported (N Engl J Med. 2008 Sep 25;359[13]:1343-56), SEAS was a negative trial. Lipid-lowering therapy didn’t affect AS progression or aortic valve–related outcomes. On the plus side, the SEAS cohort is the world’s largest population of patients with asymptomatic AS followed prospectively for clinical endpoints, noted Dr. Wachtell of Oslo University.

He and his coinvestigators decided to plot all-cause mortality versus average blood pressure in the SEAS cohort because of the paucity of data regarding blood pressure and antihypertensive therapy in patients with asymptomatic AS. Neither the 2014 ACC/AHA guidelines for management of valvular heart disease (Circulation. 2014 Jun 10;129[23]:e521-643) nor the European guidelines provide recommendations for optimal blood pressure targets in patients with asymptomatic AS, even though AS is the third most common cardiac disease, behind hypertension and coronary artery disease.

Moreover, nearly 100,000 aortic valve replacements are done per year in the United States as a consequence of AS. And AS and hypertension go hand in hand, with the prevalence of hypertension among patients with AS cited as 50% or more in multiple studies, the cardiologist continued.

In a multivariate analysis adjusted for aortic valve area index and peak velocity, heart failure, MI, and aortic valve replacement during follow-up, all-cause mortality showed a U-shaped relationship with blood pressure. A systolic blood pressure below 120 mm Hg was associated with a 5-fold increased risk of mortality, a systolic of 120-139 mm Hg carried a 1.5-fold increased risk, and a diastolic blood pressure of 90 mm Hg or more was associated with a 1.9-fold increased risk.

“Patients with low systolic blood pressure had an increased mortality risk and should probably undertake individual clinical assessment for blood pressure control and evaluation of their AS,” Dr. Wachtell said.

The first question audience members asked was, “What about SPRINT?” The SPRINT trial, presented elsewhere at the meeting, was a practice-changing study that was the talk of the conference. It redefined the systolic blood pressure treatment target as less than 120 mm Hg instead of less than 140 mm Hg in hypertensive patients (N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1511939).

“I think it’s most likely that for blood pressure, one size does not fit all,” Dr. Wachtell replied. “The extent of target organ damage – and you could say that aortic stenosis is actually target organ damage, like atrial fibrillation or left ventricular hypertrophy – warrants a different level of blood pressure.”

He added, however, that the SEAS analysis was based on observational data, and that’s a limitation.

“This is a qualified guess as to what blood pressures should be in patients with aortic stenosis,” he cautioned.

Dr. Wachtell reported having no conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

ORLANDO – Optimal blood pressure in patients with asymptomatic mild to moderate aortic stenosis is 140-159 mm Hg for systolic and 70-89 mm Hg for diastolic, according to an analysis of all-cause mortality in the world’s largest data set of such patients with longitudinal follow-up and endpoint evaluation.

Within those target blood pressure ranges, the nadir in terms of all-cause mortality – and thus the true optimal blood pressure – is about 145/82 mm Hg, Dr. Kristian Wachtell reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

He presented an analysis of 1,873 asymptomatic patients with mild to moderate aortic stenosis (AS) and a peak aortic-jet velocity of 2.5-4.0 M/sec upon enrollment in the Simvastatin Ezetimibe in Aortic Stenosis (SEAS) trial. SEAS was a double-blind, multicenter study in which participants were randomized to 40 mg of simvastatin plus 10 mg of ezetimibe per day or placebo and followed for a mean of 4.3 years. Half of them had a history of hypertension at baseline.

As previously reported (N Engl J Med. 2008 Sep 25;359[13]:1343-56), SEAS was a negative trial. Lipid-lowering therapy didn’t affect AS progression or aortic valve–related outcomes. On the plus side, the SEAS cohort is the world’s largest population of patients with asymptomatic AS followed prospectively for clinical endpoints, noted Dr. Wachtell of Oslo University.

He and his coinvestigators decided to plot all-cause mortality versus average blood pressure in the SEAS cohort because of the paucity of data regarding blood pressure and antihypertensive therapy in patients with asymptomatic AS. Neither the 2014 ACC/AHA guidelines for management of valvular heart disease (Circulation. 2014 Jun 10;129[23]:e521-643) nor the European guidelines provide recommendations for optimal blood pressure targets in patients with asymptomatic AS, even though AS is the third most common cardiac disease, behind hypertension and coronary artery disease.

Moreover, nearly 100,000 aortic valve replacements are done per year in the United States as a consequence of AS. And AS and hypertension go hand in hand, with the prevalence of hypertension among patients with AS cited as 50% or more in multiple studies, the cardiologist continued.

In a multivariate analysis adjusted for aortic valve area index and peak velocity, heart failure, MI, and aortic valve replacement during follow-up, all-cause mortality showed a U-shaped relationship with blood pressure. A systolic blood pressure below 120 mm Hg was associated with a 5-fold increased risk of mortality, a systolic of 120-139 mm Hg carried a 1.5-fold increased risk, and a diastolic blood pressure of 90 mm Hg or more was associated with a 1.9-fold increased risk.

“Patients with low systolic blood pressure had an increased mortality risk and should probably undertake individual clinical assessment for blood pressure control and evaluation of their AS,” Dr. Wachtell said.

The first question audience members asked was, “What about SPRINT?” The SPRINT trial, presented elsewhere at the meeting, was a practice-changing study that was the talk of the conference. It redefined the systolic blood pressure treatment target as less than 120 mm Hg instead of less than 140 mm Hg in hypertensive patients (N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1511939).

“I think it’s most likely that for blood pressure, one size does not fit all,” Dr. Wachtell replied. “The extent of target organ damage – and you could say that aortic stenosis is actually target organ damage, like atrial fibrillation or left ventricular hypertrophy – warrants a different level of blood pressure.”

He added, however, that the SEAS analysis was based on observational data, and that’s a limitation.

“This is a qualified guess as to what blood pressures should be in patients with aortic stenosis,” he cautioned.

Dr. Wachtell reported having no conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

ORLANDO – Optimal blood pressure in patients with asymptomatic mild to moderate aortic stenosis is 140-159 mm Hg for systolic and 70-89 mm Hg for diastolic, according to an analysis of all-cause mortality in the world’s largest data set of such patients with longitudinal follow-up and endpoint evaluation.

Within those target blood pressure ranges, the nadir in terms of all-cause mortality – and thus the true optimal blood pressure – is about 145/82 mm Hg, Dr. Kristian Wachtell reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

He presented an analysis of 1,873 asymptomatic patients with mild to moderate aortic stenosis (AS) and a peak aortic-jet velocity of 2.5-4.0 M/sec upon enrollment in the Simvastatin Ezetimibe in Aortic Stenosis (SEAS) trial. SEAS was a double-blind, multicenter study in which participants were randomized to 40 mg of simvastatin plus 10 mg of ezetimibe per day or placebo and followed for a mean of 4.3 years. Half of them had a history of hypertension at baseline.

As previously reported (N Engl J Med. 2008 Sep 25;359[13]:1343-56), SEAS was a negative trial. Lipid-lowering therapy didn’t affect AS progression or aortic valve–related outcomes. On the plus side, the SEAS cohort is the world’s largest population of patients with asymptomatic AS followed prospectively for clinical endpoints, noted Dr. Wachtell of Oslo University.

He and his coinvestigators decided to plot all-cause mortality versus average blood pressure in the SEAS cohort because of the paucity of data regarding blood pressure and antihypertensive therapy in patients with asymptomatic AS. Neither the 2014 ACC/AHA guidelines for management of valvular heart disease (Circulation. 2014 Jun 10;129[23]:e521-643) nor the European guidelines provide recommendations for optimal blood pressure targets in patients with asymptomatic AS, even though AS is the third most common cardiac disease, behind hypertension and coronary artery disease.

Moreover, nearly 100,000 aortic valve replacements are done per year in the United States as a consequence of AS. And AS and hypertension go hand in hand, with the prevalence of hypertension among patients with AS cited as 50% or more in multiple studies, the cardiologist continued.

In a multivariate analysis adjusted for aortic valve area index and peak velocity, heart failure, MI, and aortic valve replacement during follow-up, all-cause mortality showed a U-shaped relationship with blood pressure. A systolic blood pressure below 120 mm Hg was associated with a 5-fold increased risk of mortality, a systolic of 120-139 mm Hg carried a 1.5-fold increased risk, and a diastolic blood pressure of 90 mm Hg or more was associated with a 1.9-fold increased risk.

“Patients with low systolic blood pressure had an increased mortality risk and should probably undertake individual clinical assessment for blood pressure control and evaluation of their AS,” Dr. Wachtell said.

The first question audience members asked was, “What about SPRINT?” The SPRINT trial, presented elsewhere at the meeting, was a practice-changing study that was the talk of the conference. It redefined the systolic blood pressure treatment target as less than 120 mm Hg instead of less than 140 mm Hg in hypertensive patients (N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1511939).

“I think it’s most likely that for blood pressure, one size does not fit all,” Dr. Wachtell replied. “The extent of target organ damage – and you could say that aortic stenosis is actually target organ damage, like atrial fibrillation or left ventricular hypertrophy – warrants a different level of blood pressure.”

He added, however, that the SEAS analysis was based on observational data, and that’s a limitation.

“This is a qualified guess as to what blood pressures should be in patients with aortic stenosis,” he cautioned.

Dr. Wachtell reported having no conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

AHA: Should BP targets be higher in asymptomatic aortic stenosis?

ORLANDO – Optimal blood pressure in patients with asymptomatic mild to moderate aortic stenosis is 140-159 mm Hg for systolic and 70-89 mm Hg for diastolic, according to an analysis of all-cause mortality in the world’s largest data set of such patients with longitudinal follow-up and endpoint evaluation.

Within those target blood pressure ranges, the nadir in terms of all-cause mortality – and thus the true optimal blood pressure – is about 145/82 mm Hg, Dr. Kristian Wachtell reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

He presented an analysis of 1,873 asymptomatic patients with mild to moderate aortic stenosis (AS) and a peak aortic-jet velocity of 2.5-4.0 M/sec upon enrollment in the Simvastatin Ezetimibe in Aortic Stenosis (SEAS) trial. SEAS was a double-blind, multicenter study in which participants were randomized to 40 mg of simvastatin plus 10 mg of ezetimibe per day or placebo and followed for a mean of 4.3 years. Half of them had a history of hypertension at baseline.

As previously reported (N Engl J Med. 2008 Sep 25;359[13]:1343-56), SEAS was a negative trial. Lipid-lowering therapy didn’t affect AS progression or aortic valve–related outcomes. On the plus side, the SEAS cohort is the world’s largest population of patients with asymptomatic AS followed prospectively for clinical endpoints, noted Dr. Wachtell of Oslo University.

He and his coinvestigators decided to plot all-cause mortality versus average blood pressure in the SEAS cohort because of the paucity of data regarding blood pressure and antihypertensive therapy in patients with asymptomatic AS. Neither the 2014 ACC/AHA guidelines for management of valvular heart disease (Circulation. 2014 Jun 10;129[23]:e521-643) nor the European guidelines provide recommendations for optimal blood pressure targets in patients with asymptomatic AS, even though AS is the third most common cardiac disease, behind hypertension and coronary artery disease.

Moreover, nearly 100,000 aortic valve replacements are done per year in the United States as a consequence of AS. And AS and hypertension go hand in hand, with the prevalence of hypertension among patients with AS cited as 50% or more in multiple studies, the cardiologist continued.

In a multivariate analysis adjusted for aortic valve area index and peak velocity, heart failure, MI, and aortic valve replacement during follow-up, all-cause mortality showed a U-shaped relationship with blood pressure. A systolic blood pressure below 120 mm Hg was associated with a 5-fold increased risk of mortality, a systolic of 120-139 mm Hg carried a 1.5-fold increased risk, and a diastolic blood pressure of 90 mm Hg or more was associated with a 1.9-fold increased risk.

“Patients with low systolic blood pressure had an increased mortality risk and should probably undertake individual clinical assessment for blood pressure control and evaluation of their AS,” Dr. Wachtell said.

The first question audience members asked was, “What about SPRINT?” The SPRINT trial, presented elsewhere at the meeting, was a practice-changing study that was the talk of the conference. It redefined the systolic blood pressure treatment target as less than 120 mm Hg instead of less than 140 mm Hg in hypertensive patients (N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1511939).

“I think it’s most likely that for blood pressure, one size does not fit all,” Dr. Wachtell replied. “The extent of target organ damage – and you could say that aortic stenosis is actually target organ damage, like atrial fibrillation or left ventricular hypertrophy – warrants a different level of blood pressure.”

He added, however, that the SEAS analysis was based on observational data, and that’s a limitation.

“This is a qualified guess as to what blood pressures should be in patients with aortic stenosis,” he cautioned.

Dr. Wachtell reported having no conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

ORLANDO – Optimal blood pressure in patients with asymptomatic mild to moderate aortic stenosis is 140-159 mm Hg for systolic and 70-89 mm Hg for diastolic, according to an analysis of all-cause mortality in the world’s largest data set of such patients with longitudinal follow-up and endpoint evaluation.

Within those target blood pressure ranges, the nadir in terms of all-cause mortality – and thus the true optimal blood pressure – is about 145/82 mm Hg, Dr. Kristian Wachtell reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

He presented an analysis of 1,873 asymptomatic patients with mild to moderate aortic stenosis (AS) and a peak aortic-jet velocity of 2.5-4.0 M/sec upon enrollment in the Simvastatin Ezetimibe in Aortic Stenosis (SEAS) trial. SEAS was a double-blind, multicenter study in which participants were randomized to 40 mg of simvastatin plus 10 mg of ezetimibe per day or placebo and followed for a mean of 4.3 years. Half of them had a history of hypertension at baseline.

As previously reported (N Engl J Med. 2008 Sep 25;359[13]:1343-56), SEAS was a negative trial. Lipid-lowering therapy didn’t affect AS progression or aortic valve–related outcomes. On the plus side, the SEAS cohort is the world’s largest population of patients with asymptomatic AS followed prospectively for clinical endpoints, noted Dr. Wachtell of Oslo University.

He and his coinvestigators decided to plot all-cause mortality versus average blood pressure in the SEAS cohort because of the paucity of data regarding blood pressure and antihypertensive therapy in patients with asymptomatic AS. Neither the 2014 ACC/AHA guidelines for management of valvular heart disease (Circulation. 2014 Jun 10;129[23]:e521-643) nor the European guidelines provide recommendations for optimal blood pressure targets in patients with asymptomatic AS, even though AS is the third most common cardiac disease, behind hypertension and coronary artery disease.

Moreover, nearly 100,000 aortic valve replacements are done per year in the United States as a consequence of AS. And AS and hypertension go hand in hand, with the prevalence of hypertension among patients with AS cited as 50% or more in multiple studies, the cardiologist continued.

In a multivariate analysis adjusted for aortic valve area index and peak velocity, heart failure, MI, and aortic valve replacement during follow-up, all-cause mortality showed a U-shaped relationship with blood pressure. A systolic blood pressure below 120 mm Hg was associated with a 5-fold increased risk of mortality, a systolic of 120-139 mm Hg carried a 1.5-fold increased risk, and a diastolic blood pressure of 90 mm Hg or more was associated with a 1.9-fold increased risk.

“Patients with low systolic blood pressure had an increased mortality risk and should probably undertake individual clinical assessment for blood pressure control and evaluation of their AS,” Dr. Wachtell said.

The first question audience members asked was, “What about SPRINT?” The SPRINT trial, presented elsewhere at the meeting, was a practice-changing study that was the talk of the conference. It redefined the systolic blood pressure treatment target as less than 120 mm Hg instead of less than 140 mm Hg in hypertensive patients (N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1511939).

“I think it’s most likely that for blood pressure, one size does not fit all,” Dr. Wachtell replied. “The extent of target organ damage – and you could say that aortic stenosis is actually target organ damage, like atrial fibrillation or left ventricular hypertrophy – warrants a different level of blood pressure.”

He added, however, that the SEAS analysis was based on observational data, and that’s a limitation.

“This is a qualified guess as to what blood pressures should be in patients with aortic stenosis,” he cautioned.

Dr. Wachtell reported having no conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

ORLANDO – Optimal blood pressure in patients with asymptomatic mild to moderate aortic stenosis is 140-159 mm Hg for systolic and 70-89 mm Hg for diastolic, according to an analysis of all-cause mortality in the world’s largest data set of such patients with longitudinal follow-up and endpoint evaluation.

Within those target blood pressure ranges, the nadir in terms of all-cause mortality – and thus the true optimal blood pressure – is about 145/82 mm Hg, Dr. Kristian Wachtell reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

He presented an analysis of 1,873 asymptomatic patients with mild to moderate aortic stenosis (AS) and a peak aortic-jet velocity of 2.5-4.0 M/sec upon enrollment in the Simvastatin Ezetimibe in Aortic Stenosis (SEAS) trial. SEAS was a double-blind, multicenter study in which participants were randomized to 40 mg of simvastatin plus 10 mg of ezetimibe per day or placebo and followed for a mean of 4.3 years. Half of them had a history of hypertension at baseline.

As previously reported (N Engl J Med. 2008 Sep 25;359[13]:1343-56), SEAS was a negative trial. Lipid-lowering therapy didn’t affect AS progression or aortic valve–related outcomes. On the plus side, the SEAS cohort is the world’s largest population of patients with asymptomatic AS followed prospectively for clinical endpoints, noted Dr. Wachtell of Oslo University.

He and his coinvestigators decided to plot all-cause mortality versus average blood pressure in the SEAS cohort because of the paucity of data regarding blood pressure and antihypertensive therapy in patients with asymptomatic AS. Neither the 2014 ACC/AHA guidelines for management of valvular heart disease (Circulation. 2014 Jun 10;129[23]:e521-643) nor the European guidelines provide recommendations for optimal blood pressure targets in patients with asymptomatic AS, even though AS is the third most common cardiac disease, behind hypertension and coronary artery disease.

Moreover, nearly 100,000 aortic valve replacements are done per year in the United States as a consequence of AS. And AS and hypertension go hand in hand, with the prevalence of hypertension among patients with AS cited as 50% or more in multiple studies, the cardiologist continued.

In a multivariate analysis adjusted for aortic valve area index and peak velocity, heart failure, MI, and aortic valve replacement during follow-up, all-cause mortality showed a U-shaped relationship with blood pressure. A systolic blood pressure below 120 mm Hg was associated with a 5-fold increased risk of mortality, a systolic of 120-139 mm Hg carried a 1.5-fold increased risk, and a diastolic blood pressure of 90 mm Hg or more was associated with a 1.9-fold increased risk.

“Patients with low systolic blood pressure had an increased mortality risk and should probably undertake individual clinical assessment for blood pressure control and evaluation of their AS,” Dr. Wachtell said.

The first question audience members asked was, “What about SPRINT?” The SPRINT trial, presented elsewhere at the meeting, was a practice-changing study that was the talk of the conference. It redefined the systolic blood pressure treatment target as less than 120 mm Hg instead of less than 140 mm Hg in hypertensive patients (N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1511939).

“I think it’s most likely that for blood pressure, one size does not fit all,” Dr. Wachtell replied. “The extent of target organ damage – and you could say that aortic stenosis is actually target organ damage, like atrial fibrillation or left ventricular hypertrophy – warrants a different level of blood pressure.”

He added, however, that the SEAS analysis was based on observational data, and that’s a limitation.

“This is a qualified guess as to what blood pressures should be in patients with aortic stenosis,” he cautioned.

Dr. Wachtell reported having no conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Optimal blood pressures in patients with asymptomatic aortic stenosis appear to be significantly higher than those identified for the general hypertensive population in the recent SPRINT trial.

Major finding: All-cause mortality in patients with asymptomatic mild to moderate aortic stenosis is lowest at a blood pressure of 145/82 mm Hg.

Data source: This was an analysis of all-cause mortality over a mean follow-up of 4.3 years in 1,873 patients with asymptomatic mild to moderate aortic stenosis.

Disclosures: This secondary analysis of a completed clinical trial was conducted without commercial support. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

AHA: New spotlight on peripheral artery disease

ORLANDO – Peripheral artery disease constitutes “a health crisis that is largely unnoticed” by the public and all too often by physicians as well – but that’s all about to change, Dr. Mark A. Creager said in his presidential address at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

In the coming months, look for rollout of major AHA initiatives on peripheral vascular disease. These programs grew out of a summit meeting of thought leaders in the field of vascular disease convened recently by the AHA in order to find ways to boost public awareness and improve the quality of care for patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD), venous thromboembolism, and aortic aneurysm.

PAD is all too often thought of as a disease of the legs, when in fact it is a clinical manifestation of systemic atherosclerosis, Dr. Creager noted. PAD affects on estimated 200 million people worldwide. In the United States alone, it accounts for $20 billion per year in health care costs. The mortality risk in affected patients is two- to fourfold greater than in individuals without PAD. Moreover, the risk of acute MI, stroke, or cardiovascular death among patients with PAD exceeds that of patients with established cerebrovascular disease.

“Clearly the unrecognized epidemic of vascular disease requires our attention,” observed Dr. Creager, professor of medicine and director of the Heart and Vascular Center at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon, N.H.

Indeed, he made it clear that improved diagnosis and treatment of PAD will be a major AHA priority during his term as president. Noting that the annual rate of deaths due to cardiovascular disease and stroke has already dropped by 13.7% in the 5 years since the AHA set the ambitious goal of a 20% reduction by the year 2020, he emphasized that a critical element in getting the rest of the way there involves addressing peripheral vascular diseases more effectively.

Improved public awareness about PAD has to be a priority. One survey found that 75% of the public is unaware of PAD. It’s a condition which Dr. Creager and others have shown has its highest prevalence in Americans in the lowest income and educational strata, largely independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors.

“Even physicians often fail to consider PAD, chalking up leg pain to age or arthritis. In one study, physicians missed the diagnosis of PAD half the time. And even when physicians diagnose PAD, they often don’t treat it adequately,” according to Dr. Creager.

The use of statins and antiplatelet therapy in patients with PAD each reduces the risk of MI, stroke, or cardiovascular death by about 25%. Yet when Dr. Creager and coworkers analyzed National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data, they found only 19% of patients with PAD who didn’t have previously established coronary or cerebrovascular disease were on a statin, just 21% were on an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker, and 27% were on antiplatelet therapy (Circulation. 2011 Jul 5;124[1]:17-23).

Among patients with symptomatic PAD, studies have shown that supervised exercise training can double walking distance. That’s a major quality of life benefit, yet one that goes unconsidered if the diagnosis is missed. “It’s rarely instituted even with the diagnosis, largely because of the lack of reimbursement,” according to Dr. Creager.

He painted a picture of PAD as a field ripe with opportunities for improved outcomes.

“Our ability to diagnose and treat vascular diseases has never been greater. The field of vascular biology has virtually exploded in recent years,” he said. “I’d like to focus not only on the extent of this crisis, but also on the importance of using what we know to treat it and prevent it, and on the urgency of intensifying our research efforts to better understand it.”

In the diagnostic arena, optical coherence tomography, intravascular ultrasound, PET-CT, and contrast-enhanced MRI provide an unprecedented ability to image plaques and assess their vulnerability to rupture.

On the interventional front, innovative bioengineering has led to the development of drug-coated balloons and bioabsorbable vascular scaffolds with the potential to curb restenosis and preserve patency following endovascular treatment of critical lesions.

In terms of medical management, the novel, super-potent LDL cholesterol–lowering inhibitors of PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin-kexin type 9) will need to be studied in order to see if they have a special role in the treatment and/or prevention of PAD.

Roughly 2 decades ago, Dr. Creager and coinvestigators showed that endothelial function typically drops by 30% in our twenties and then in our thirties, and by 50% once we’re in our forties. A high research priority in PAD will be to learn how to more effectively prolong endothelial health and prevent vascular stiffness, he said.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding his presentation.

ORLANDO – Peripheral artery disease constitutes “a health crisis that is largely unnoticed” by the public and all too often by physicians as well – but that’s all about to change, Dr. Mark A. Creager said in his presidential address at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

In the coming months, look for rollout of major AHA initiatives on peripheral vascular disease. These programs grew out of a summit meeting of thought leaders in the field of vascular disease convened recently by the AHA in order to find ways to boost public awareness and improve the quality of care for patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD), venous thromboembolism, and aortic aneurysm.

PAD is all too often thought of as a disease of the legs, when in fact it is a clinical manifestation of systemic atherosclerosis, Dr. Creager noted. PAD affects on estimated 200 million people worldwide. In the United States alone, it accounts for $20 billion per year in health care costs. The mortality risk in affected patients is two- to fourfold greater than in individuals without PAD. Moreover, the risk of acute MI, stroke, or cardiovascular death among patients with PAD exceeds that of patients with established cerebrovascular disease.

“Clearly the unrecognized epidemic of vascular disease requires our attention,” observed Dr. Creager, professor of medicine and director of the Heart and Vascular Center at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon, N.H.

Indeed, he made it clear that improved diagnosis and treatment of PAD will be a major AHA priority during his term as president. Noting that the annual rate of deaths due to cardiovascular disease and stroke has already dropped by 13.7% in the 5 years since the AHA set the ambitious goal of a 20% reduction by the year 2020, he emphasized that a critical element in getting the rest of the way there involves addressing peripheral vascular diseases more effectively.

Improved public awareness about PAD has to be a priority. One survey found that 75% of the public is unaware of PAD. It’s a condition which Dr. Creager and others have shown has its highest prevalence in Americans in the lowest income and educational strata, largely independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors.

“Even physicians often fail to consider PAD, chalking up leg pain to age or arthritis. In one study, physicians missed the diagnosis of PAD half the time. And even when physicians diagnose PAD, they often don’t treat it adequately,” according to Dr. Creager.

The use of statins and antiplatelet therapy in patients with PAD each reduces the risk of MI, stroke, or cardiovascular death by about 25%. Yet when Dr. Creager and coworkers analyzed National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data, they found only 19% of patients with PAD who didn’t have previously established coronary or cerebrovascular disease were on a statin, just 21% were on an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker, and 27% were on antiplatelet therapy (Circulation. 2011 Jul 5;124[1]:17-23).

Among patients with symptomatic PAD, studies have shown that supervised exercise training can double walking distance. That’s a major quality of life benefit, yet one that goes unconsidered if the diagnosis is missed. “It’s rarely instituted even with the diagnosis, largely because of the lack of reimbursement,” according to Dr. Creager.

He painted a picture of PAD as a field ripe with opportunities for improved outcomes.

“Our ability to diagnose and treat vascular diseases has never been greater. The field of vascular biology has virtually exploded in recent years,” he said. “I’d like to focus not only on the extent of this crisis, but also on the importance of using what we know to treat it and prevent it, and on the urgency of intensifying our research efforts to better understand it.”

In the diagnostic arena, optical coherence tomography, intravascular ultrasound, PET-CT, and contrast-enhanced MRI provide an unprecedented ability to image plaques and assess their vulnerability to rupture.

On the interventional front, innovative bioengineering has led to the development of drug-coated balloons and bioabsorbable vascular scaffolds with the potential to curb restenosis and preserve patency following endovascular treatment of critical lesions.

In terms of medical management, the novel, super-potent LDL cholesterol–lowering inhibitors of PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin-kexin type 9) will need to be studied in order to see if they have a special role in the treatment and/or prevention of PAD.

Roughly 2 decades ago, Dr. Creager and coinvestigators showed that endothelial function typically drops by 30% in our twenties and then in our thirties, and by 50% once we’re in our forties. A high research priority in PAD will be to learn how to more effectively prolong endothelial health and prevent vascular stiffness, he said.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding his presentation.

ORLANDO – Peripheral artery disease constitutes “a health crisis that is largely unnoticed” by the public and all too often by physicians as well – but that’s all about to change, Dr. Mark A. Creager said in his presidential address at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

In the coming months, look for rollout of major AHA initiatives on peripheral vascular disease. These programs grew out of a summit meeting of thought leaders in the field of vascular disease convened recently by the AHA in order to find ways to boost public awareness and improve the quality of care for patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD), venous thromboembolism, and aortic aneurysm.

PAD is all too often thought of as a disease of the legs, when in fact it is a clinical manifestation of systemic atherosclerosis, Dr. Creager noted. PAD affects on estimated 200 million people worldwide. In the United States alone, it accounts for $20 billion per year in health care costs. The mortality risk in affected patients is two- to fourfold greater than in individuals without PAD. Moreover, the risk of acute MI, stroke, or cardiovascular death among patients with PAD exceeds that of patients with established cerebrovascular disease.

“Clearly the unrecognized epidemic of vascular disease requires our attention,” observed Dr. Creager, professor of medicine and director of the Heart and Vascular Center at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon, N.H.

Indeed, he made it clear that improved diagnosis and treatment of PAD will be a major AHA priority during his term as president. Noting that the annual rate of deaths due to cardiovascular disease and stroke has already dropped by 13.7% in the 5 years since the AHA set the ambitious goal of a 20% reduction by the year 2020, he emphasized that a critical element in getting the rest of the way there involves addressing peripheral vascular diseases more effectively.

Improved public awareness about PAD has to be a priority. One survey found that 75% of the public is unaware of PAD. It’s a condition which Dr. Creager and others have shown has its highest prevalence in Americans in the lowest income and educational strata, largely independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors.

“Even physicians often fail to consider PAD, chalking up leg pain to age or arthritis. In one study, physicians missed the diagnosis of PAD half the time. And even when physicians diagnose PAD, they often don’t treat it adequately,” according to Dr. Creager.

The use of statins and antiplatelet therapy in patients with PAD each reduces the risk of MI, stroke, or cardiovascular death by about 25%. Yet when Dr. Creager and coworkers analyzed National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data, they found only 19% of patients with PAD who didn’t have previously established coronary or cerebrovascular disease were on a statin, just 21% were on an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker, and 27% were on antiplatelet therapy (Circulation. 2011 Jul 5;124[1]:17-23).

Among patients with symptomatic PAD, studies have shown that supervised exercise training can double walking distance. That’s a major quality of life benefit, yet one that goes unconsidered if the diagnosis is missed. “It’s rarely instituted even with the diagnosis, largely because of the lack of reimbursement,” according to Dr. Creager.

He painted a picture of PAD as a field ripe with opportunities for improved outcomes.

“Our ability to diagnose and treat vascular diseases has never been greater. The field of vascular biology has virtually exploded in recent years,” he said. “I’d like to focus not only on the extent of this crisis, but also on the importance of using what we know to treat it and prevent it, and on the urgency of intensifying our research efforts to better understand it.”

In the diagnostic arena, optical coherence tomography, intravascular ultrasound, PET-CT, and contrast-enhanced MRI provide an unprecedented ability to image plaques and assess their vulnerability to rupture.

On the interventional front, innovative bioengineering has led to the development of drug-coated balloons and bioabsorbable vascular scaffolds with the potential to curb restenosis and preserve patency following endovascular treatment of critical lesions.

In terms of medical management, the novel, super-potent LDL cholesterol–lowering inhibitors of PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin-kexin type 9) will need to be studied in order to see if they have a special role in the treatment and/or prevention of PAD.

Roughly 2 decades ago, Dr. Creager and coinvestigators showed that endothelial function typically drops by 30% in our twenties and then in our thirties, and by 50% once we’re in our forties. A high research priority in PAD will be to learn how to more effectively prolong endothelial health and prevent vascular stiffness, he said.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding his presentation.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

AHA: Three measures risk stratify acute heart failure

ORLANDO – Three simple, routinely collected measurements together provide a lot of insight into the risk faced by community-dwelling patients hospitalized for acute decompensated heart failure, according to data collected from 3,628 patients at one U.S. center.

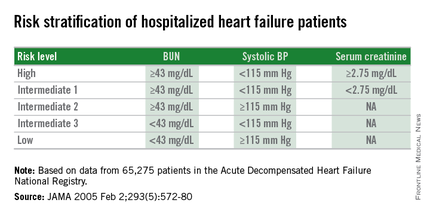

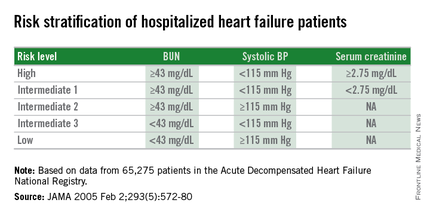

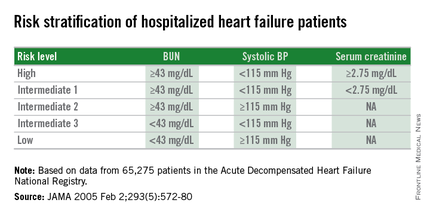

The three measures are blood urea nitrogen (BUN), systolic blood pressure, and serum creatinine. Using dichotomous cutoffs first calculated a decade ago, these three parameters distinguish up to an eightfold range of postdischarge mortality during the 30 or 90 days following an index hospitalization, and up to a fourfold range of risk for rehospitalization for heart failure during the ensuing 30 or 90 days, Dr. Sithu Win said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Applying this three-measure assessment to patients hospitalized with acute decompensated heart failure “may guide care-transition planning and promote efficient allocation of limited resources,” said Dr. Win, a cardiologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. The next step is to try to figure out the best way to use this risk prognostication in routine practice, he added.

Researchers published the original analysis that identified BUN, systolic BP, and serum creatinine as key prognostic measures in 2005 using data taken from more than 65,000 U.S. heart failure patients enrolled in ADHERE (Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry) (JAMA. 2005 Feb 2;293[5]:572-80). Using a classification and regression tree analysis, the 2005 study verified dichotomous cutoffs for these three parameters that identified patients at highest risk for in-hospital mortality.

The 2005 study prioritized the application of these cutoffs to define in-hospital mortality risk: first BUN, then the systolic BP criterion, and lastly the serum creatinine criterion. This resulted in five risk levels: Highest-risk patients had a BUN of at least 43 mg/dL, a systolic BP of less than 115 mm Hg, and a serum creatinine of at least 2.75 mg/dL. Lowest-risk patients had a BUN of less than 43 mg/dL and a systolic BP of more than 115 mm Hg. (In lower-risk patients, serum-creatinine level dropped out as a risk determinant.) The analysis also created three categories of patients with intermediate risk based on various combinations of the three measures.

The new study run by Dr. Win and his associates evaluated how this risk-assessment tool developed to predict in-hospital mortality performed for predicting event rates among community-based heart failure patients who had a total of 5,918 hospitalizations for acute decompensated heart failure at the Mayo Clinic during 2000-2013. They averaged 78 years old, half were women, and 48% had heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.

The risk-level distribution of the 3,628 Mayo patients closely matched the pattern seen in the original ADHERE registry: 63% were low risk, 17% were at intermediate level 3 (the lowest risk level in the intermediate range), 13% were at intermediate level 2, 5% at intermediate level 1, and 2% were categorized as high risk.

For 30-day mortality post hospitalization, patients at the highest risk level had a mortality rate eightfold higher than did the lowest-risk patients, those rated intermediate level 1 had a fivefold higher mortality rate, intermediate level 2 patients had a threefold higher rate, and those at intermediate 3 had a 50% higher rate, Dr. Win reported. During the 90 days after discharge, mortality rates relative to the lowest risk level ranged from a sixfold higher rate among the highest-risk patients to a 50% higher rate among patients with an intermediate 3 designation.

Analysis of rehospitalizations for heart failure showed that, by 30 days after hospitalization, the readmission rate ran threefold higher in the highest-risk patients, compared with those at the lowest risk and fourfold higher among those at intermediate risk level 1. Heart failure readmissions by 90 days following the index hospitalization ran threefold higher for both the highest-risk patients as well as those at intermediate level 1, compared with the patients at lowest risk.

The new analyses also showed that roughly similar risk patterns occurred regardless of whether patients had heart failure with reduced or preserved ejection fraction during their index hospitalization, although the relatively increased rate of 30-day mortality with a worse risk profile was most dramatic among patients with reduced ejection fraction. Age, sex, and comorbidity severity did not have a marked effect on the relationships between event rates and risk levels, Dr. Win said.

Dr. Win had no disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ORLANDO – Three simple, routinely collected measurements together provide a lot of insight into the risk faced by community-dwelling patients hospitalized for acute decompensated heart failure, according to data collected from 3,628 patients at one U.S. center.

The three measures are blood urea nitrogen (BUN), systolic blood pressure, and serum creatinine. Using dichotomous cutoffs first calculated a decade ago, these three parameters distinguish up to an eightfold range of postdischarge mortality during the 30 or 90 days following an index hospitalization, and up to a fourfold range of risk for rehospitalization for heart failure during the ensuing 30 or 90 days, Dr. Sithu Win said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Applying this three-measure assessment to patients hospitalized with acute decompensated heart failure “may guide care-transition planning and promote efficient allocation of limited resources,” said Dr. Win, a cardiologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. The next step is to try to figure out the best way to use this risk prognostication in routine practice, he added.

Researchers published the original analysis that identified BUN, systolic BP, and serum creatinine as key prognostic measures in 2005 using data taken from more than 65,000 U.S. heart failure patients enrolled in ADHERE (Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry) (JAMA. 2005 Feb 2;293[5]:572-80). Using a classification and regression tree analysis, the 2005 study verified dichotomous cutoffs for these three parameters that identified patients at highest risk for in-hospital mortality.

The 2005 study prioritized the application of these cutoffs to define in-hospital mortality risk: first BUN, then the systolic BP criterion, and lastly the serum creatinine criterion. This resulted in five risk levels: Highest-risk patients had a BUN of at least 43 mg/dL, a systolic BP of less than 115 mm Hg, and a serum creatinine of at least 2.75 mg/dL. Lowest-risk patients had a BUN of less than 43 mg/dL and a systolic BP of more than 115 mm Hg. (In lower-risk patients, serum-creatinine level dropped out as a risk determinant.) The analysis also created three categories of patients with intermediate risk based on various combinations of the three measures.

The new study run by Dr. Win and his associates evaluated how this risk-assessment tool developed to predict in-hospital mortality performed for predicting event rates among community-based heart failure patients who had a total of 5,918 hospitalizations for acute decompensated heart failure at the Mayo Clinic during 2000-2013. They averaged 78 years old, half were women, and 48% had heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.

The risk-level distribution of the 3,628 Mayo patients closely matched the pattern seen in the original ADHERE registry: 63% were low risk, 17% were at intermediate level 3 (the lowest risk level in the intermediate range), 13% were at intermediate level 2, 5% at intermediate level 1, and 2% were categorized as high risk.

For 30-day mortality post hospitalization, patients at the highest risk level had a mortality rate eightfold higher than did the lowest-risk patients, those rated intermediate level 1 had a fivefold higher mortality rate, intermediate level 2 patients had a threefold higher rate, and those at intermediate 3 had a 50% higher rate, Dr. Win reported. During the 90 days after discharge, mortality rates relative to the lowest risk level ranged from a sixfold higher rate among the highest-risk patients to a 50% higher rate among patients with an intermediate 3 designation.

Analysis of rehospitalizations for heart failure showed that, by 30 days after hospitalization, the readmission rate ran threefold higher in the highest-risk patients, compared with those at the lowest risk and fourfold higher among those at intermediate risk level 1. Heart failure readmissions by 90 days following the index hospitalization ran threefold higher for both the highest-risk patients as well as those at intermediate level 1, compared with the patients at lowest risk.

The new analyses also showed that roughly similar risk patterns occurred regardless of whether patients had heart failure with reduced or preserved ejection fraction during their index hospitalization, although the relatively increased rate of 30-day mortality with a worse risk profile was most dramatic among patients with reduced ejection fraction. Age, sex, and comorbidity severity did not have a marked effect on the relationships between event rates and risk levels, Dr. Win said.

Dr. Win had no disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ORLANDO – Three simple, routinely collected measurements together provide a lot of insight into the risk faced by community-dwelling patients hospitalized for acute decompensated heart failure, according to data collected from 3,628 patients at one U.S. center.

The three measures are blood urea nitrogen (BUN), systolic blood pressure, and serum creatinine. Using dichotomous cutoffs first calculated a decade ago, these three parameters distinguish up to an eightfold range of postdischarge mortality during the 30 or 90 days following an index hospitalization, and up to a fourfold range of risk for rehospitalization for heart failure during the ensuing 30 or 90 days, Dr. Sithu Win said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Applying this three-measure assessment to patients hospitalized with acute decompensated heart failure “may guide care-transition planning and promote efficient allocation of limited resources,” said Dr. Win, a cardiologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. The next step is to try to figure out the best way to use this risk prognostication in routine practice, he added.

Researchers published the original analysis that identified BUN, systolic BP, and serum creatinine as key prognostic measures in 2005 using data taken from more than 65,000 U.S. heart failure patients enrolled in ADHERE (Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry) (JAMA. 2005 Feb 2;293[5]:572-80). Using a classification and regression tree analysis, the 2005 study verified dichotomous cutoffs for these three parameters that identified patients at highest risk for in-hospital mortality.

The 2005 study prioritized the application of these cutoffs to define in-hospital mortality risk: first BUN, then the systolic BP criterion, and lastly the serum creatinine criterion. This resulted in five risk levels: Highest-risk patients had a BUN of at least 43 mg/dL, a systolic BP of less than 115 mm Hg, and a serum creatinine of at least 2.75 mg/dL. Lowest-risk patients had a BUN of less than 43 mg/dL and a systolic BP of more than 115 mm Hg. (In lower-risk patients, serum-creatinine level dropped out as a risk determinant.) The analysis also created three categories of patients with intermediate risk based on various combinations of the three measures.

The new study run by Dr. Win and his associates evaluated how this risk-assessment tool developed to predict in-hospital mortality performed for predicting event rates among community-based heart failure patients who had a total of 5,918 hospitalizations for acute decompensated heart failure at the Mayo Clinic during 2000-2013. They averaged 78 years old, half were women, and 48% had heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.

The risk-level distribution of the 3,628 Mayo patients closely matched the pattern seen in the original ADHERE registry: 63% were low risk, 17% were at intermediate level 3 (the lowest risk level in the intermediate range), 13% were at intermediate level 2, 5% at intermediate level 1, and 2% were categorized as high risk.

For 30-day mortality post hospitalization, patients at the highest risk level had a mortality rate eightfold higher than did the lowest-risk patients, those rated intermediate level 1 had a fivefold higher mortality rate, intermediate level 2 patients had a threefold higher rate, and those at intermediate 3 had a 50% higher rate, Dr. Win reported. During the 90 days after discharge, mortality rates relative to the lowest risk level ranged from a sixfold higher rate among the highest-risk patients to a 50% higher rate among patients with an intermediate 3 designation.

Analysis of rehospitalizations for heart failure showed that, by 30 days after hospitalization, the readmission rate ran threefold higher in the highest-risk patients, compared with those at the lowest risk and fourfold higher among those at intermediate risk level 1. Heart failure readmissions by 90 days following the index hospitalization ran threefold higher for both the highest-risk patients as well as those at intermediate level 1, compared with the patients at lowest risk.

The new analyses also showed that roughly similar risk patterns occurred regardless of whether patients had heart failure with reduced or preserved ejection fraction during their index hospitalization, although the relatively increased rate of 30-day mortality with a worse risk profile was most dramatic among patients with reduced ejection fraction. Age, sex, and comorbidity severity did not have a marked effect on the relationships between event rates and risk levels, Dr. Win said.

Dr. Win had no disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Dichotomous cutoffs for BUN, systolic BP, and serum creatinine together robustly risk stratified patients hospitalized for acute decompensated heart failure.

Major finding: Three baseline measures together stratified patients over an eightfold range for 30-day mortality following hospital discharge.

Data source: Application of the risk-stratification formula to 3,628 heart failure patients hospitalized at one U.S. center during 2000-2013.

Disclosures: Dr. Win had no disclosures.

AHA: Spirometry Identifies Mortality Risk in Asymptomatic Adults

ORLANDO – Unselected people from the general population without clinically apparent lung disease but with low lung function had significantly increased mortality during follow-up that was independent of cardiac function, in results from more than 13,000 middle-aged Germans.

“Subtle, subclinical pulmonary impairment is a risk indicator for increased mortality independent of cardiac performance,” Dr. Christina Baum said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The researchers used spirometry to measure each subject’s forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC). The results showed that “spirometry is a good screening tool that is not very expensive,” making spirometry an effective risk assessment tool for use in the general adult population, said Dr. Baum of the department of general and interventional cardiology at the University Heart Center in Hamburg, Germany.

She and her associates used data collected in the Gutenberg Health Study, which enrolled more than 15,000 German women and men aged 35-74 years during 2007-2012. The investigators excluded people with a history of pulmonary disease, resulting in a study cohort of 13,191, who averaged 55 years old, with 51% men.

At enrollment into the study, all people underwent screening spirometry and echocardiography. Their average baseline FEV1 was 2.9 L and their average FVC was 3.7 L, and 4% had heart failure based on assessments of left ventricular size and function by echocardiography. The first 5,000 enrollees also had measurements taken of their serum levels of N-terminal probrain natriuretic peptide and cardiac troponin I through use of a high-sensitivity assay. The researchers used data from patients followed for a median of 5.5 years.

During follow-up, people in the lowest tertile for FEV1 and those in the lowest tertile for FVC had higher rates of all-cause mortality, compared with those in the highest tertile for each of these two parameters.

In a multivariate analysis that adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, smoking status, hypertension, dyslipidemia, heart failure status, serum levels of N-terminal probrain natriuretic peptide and cardiac troponin I, and other parameters, people with lower FEV1 and FVC readings had significantly worse survival, Dr. Baum said. Every 1–standard deviation increase in FEV1 was linked with a statistically significant, 38% reduced mortality rate; furthermore, a similar significant inverse association existed between FVC and mortality, she reported.

ORLANDO – Unselected people from the general population without clinically apparent lung disease but with low lung function had significantly increased mortality during follow-up that was independent of cardiac function, in results from more than 13,000 middle-aged Germans.

“Subtle, subclinical pulmonary impairment is a risk indicator for increased mortality independent of cardiac performance,” Dr. Christina Baum said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The researchers used spirometry to measure each subject’s forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC). The results showed that “spirometry is a good screening tool that is not very expensive,” making spirometry an effective risk assessment tool for use in the general adult population, said Dr. Baum of the department of general and interventional cardiology at the University Heart Center in Hamburg, Germany.

She and her associates used data collected in the Gutenberg Health Study, which enrolled more than 15,000 German women and men aged 35-74 years during 2007-2012. The investigators excluded people with a history of pulmonary disease, resulting in a study cohort of 13,191, who averaged 55 years old, with 51% men.

At enrollment into the study, all people underwent screening spirometry and echocardiography. Their average baseline FEV1 was 2.9 L and their average FVC was 3.7 L, and 4% had heart failure based on assessments of left ventricular size and function by echocardiography. The first 5,000 enrollees also had measurements taken of their serum levels of N-terminal probrain natriuretic peptide and cardiac troponin I through use of a high-sensitivity assay. The researchers used data from patients followed for a median of 5.5 years.

During follow-up, people in the lowest tertile for FEV1 and those in the lowest tertile for FVC had higher rates of all-cause mortality, compared with those in the highest tertile for each of these two parameters.

In a multivariate analysis that adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, smoking status, hypertension, dyslipidemia, heart failure status, serum levels of N-terminal probrain natriuretic peptide and cardiac troponin I, and other parameters, people with lower FEV1 and FVC readings had significantly worse survival, Dr. Baum said. Every 1–standard deviation increase in FEV1 was linked with a statistically significant, 38% reduced mortality rate; furthermore, a similar significant inverse association existed between FVC and mortality, she reported.

ORLANDO – Unselected people from the general population without clinically apparent lung disease but with low lung function had significantly increased mortality during follow-up that was independent of cardiac function, in results from more than 13,000 middle-aged Germans.

“Subtle, subclinical pulmonary impairment is a risk indicator for increased mortality independent of cardiac performance,” Dr. Christina Baum said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The researchers used spirometry to measure each subject’s forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC). The results showed that “spirometry is a good screening tool that is not very expensive,” making spirometry an effective risk assessment tool for use in the general adult population, said Dr. Baum of the department of general and interventional cardiology at the University Heart Center in Hamburg, Germany.

She and her associates used data collected in the Gutenberg Health Study, which enrolled more than 15,000 German women and men aged 35-74 years during 2007-2012. The investigators excluded people with a history of pulmonary disease, resulting in a study cohort of 13,191, who averaged 55 years old, with 51% men.

At enrollment into the study, all people underwent screening spirometry and echocardiography. Their average baseline FEV1 was 2.9 L and their average FVC was 3.7 L, and 4% had heart failure based on assessments of left ventricular size and function by echocardiography. The first 5,000 enrollees also had measurements taken of their serum levels of N-terminal probrain natriuretic peptide and cardiac troponin I through use of a high-sensitivity assay. The researchers used data from patients followed for a median of 5.5 years.

During follow-up, people in the lowest tertile for FEV1 and those in the lowest tertile for FVC had higher rates of all-cause mortality, compared with those in the highest tertile for each of these two parameters.

In a multivariate analysis that adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, smoking status, hypertension, dyslipidemia, heart failure status, serum levels of N-terminal probrain natriuretic peptide and cardiac troponin I, and other parameters, people with lower FEV1 and FVC readings had significantly worse survival, Dr. Baum said. Every 1–standard deviation increase in FEV1 was linked with a statistically significant, 38% reduced mortality rate; furthermore, a similar significant inverse association existed between FVC and mortality, she reported.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

AHA: Spirometry identifies mortality risk in asymptomatic adults

ORLANDO – Unselected people from the general population without clinically apparent lung disease but with low lung function had significantly increased mortality during follow-up that was independent of cardiac function, in results from more than 13,000 middle-aged Germans.

“Subtle, subclinical pulmonary impairment is a risk indicator for increased mortality independent of cardiac performance,” Dr. Christina Baum said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The researchers used spirometry to measure each subject’s forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC). The results showed that “spirometry is a good screening tool that is not very expensive,” making spirometry an effective risk assessment tool for use in the general adult population, said Dr. Baum of the department of general and interventional cardiology at the University Heart Center in Hamburg, Germany.

She and her associates used data collected in the Gutenberg Health Study, which enrolled more than 15,000 German women and men aged 35-74 years during 2007-2012. The investigators excluded people with a history of pulmonary disease, resulting in a study cohort of 13,191, who averaged 55 years old, with 51% men.

At enrollment into the study, all people underwent screening spirometry and echocardiography. Their average baseline FEV1 was 2.9 L and their average FVC was 3.7 L, and 4% had heart failure based on assessments of left ventricular size and function by echocardiography. The first 5,000 enrollees also had measurements taken of their serum levels of N-terminal probrain natriuretic peptide and cardiac troponin I through use of a high-sensitivity assay. The researchers used data from patients followed for a median of 5.5 years.

During follow-up, people in the lowest tertile for FEV1 and those in the lowest tertile for FVC had higher rates of all-cause mortality, compared with those in the highest tertile for each of these two parameters.

In a multivariate analysis that adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, smoking status, hypertension, dyslipidemia, heart failure status, serum levels of N-terminal probrain natriuretic peptide and cardiac troponin I, and other parameters, people with lower FEV1 and FVC readings had significantly worse survival, Dr. Baum said. Every 1–standard deviation increase in FEV1 was linked with a statistically significant, 38% reduced mortality rate; furthermore, a similar significant inverse association existed between FVC and mortality, she reported.

On Twitter@mitchelzoler

ORLANDO – Unselected people from the general population without clinically apparent lung disease but with low lung function had significantly increased mortality during follow-up that was independent of cardiac function, in results from more than 13,000 middle-aged Germans.

“Subtle, subclinical pulmonary impairment is a risk indicator for increased mortality independent of cardiac performance,” Dr. Christina Baum said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The researchers used spirometry to measure each subject’s forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC). The results showed that “spirometry is a good screening tool that is not very expensive,” making spirometry an effective risk assessment tool for use in the general adult population, said Dr. Baum of the department of general and interventional cardiology at the University Heart Center in Hamburg, Germany.

She and her associates used data collected in the Gutenberg Health Study, which enrolled more than 15,000 German women and men aged 35-74 years during 2007-2012. The investigators excluded people with a history of pulmonary disease, resulting in a study cohort of 13,191, who averaged 55 years old, with 51% men.

At enrollment into the study, all people underwent screening spirometry and echocardiography. Their average baseline FEV1 was 2.9 L and their average FVC was 3.7 L, and 4% had heart failure based on assessments of left ventricular size and function by echocardiography. The first 5,000 enrollees also had measurements taken of their serum levels of N-terminal probrain natriuretic peptide and cardiac troponin I through use of a high-sensitivity assay. The researchers used data from patients followed for a median of 5.5 years.

During follow-up, people in the lowest tertile for FEV1 and those in the lowest tertile for FVC had higher rates of all-cause mortality, compared with those in the highest tertile for each of these two parameters.

In a multivariate analysis that adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, smoking status, hypertension, dyslipidemia, heart failure status, serum levels of N-terminal probrain natriuretic peptide and cardiac troponin I, and other parameters, people with lower FEV1 and FVC readings had significantly worse survival, Dr. Baum said. Every 1–standard deviation increase in FEV1 was linked with a statistically significant, 38% reduced mortality rate; furthermore, a similar significant inverse association existed between FVC and mortality, she reported.

On Twitter@mitchelzoler