User login

Codes, Contracts, and Commitments: Who Defines What is a Profession?

Codes, Contracts, and Commitments: Who Defines What is a Profession?

A professional is someone who can do his best work when he doesn’t feel like it.

Alistair Cooke

When I was a young person with no idea about growing up to be something, my father used to tell me there were 4 learned professions: medicine to heal the body, law to protect the body politic, teaching to nurture the mind, and the clergy to care for the soul.1 That adage, or some version of it, is attributed to a variety of sources, likely because it captures something essential and timeless about the learned professions. I write this as a much older person, and it has been my privilege to have worked in some capacity in all 4 of these venerable vocations.

There are many more recognized professions now than in my father’s time with new ones still emerging as the world becomes more complicated and specialized. In November 2025, however, the growth of the professions was dealt a serious blow when the US Department of Education (DOE) redefined what constitutes a profession for the purpose of federal funding of graduate degrees.2 The internet is understandably abuzz with opinions across the political spectrum. What is missing from many of these discussions is an understanding of the criteria for a profession and, even more importantly, who has the authority to decide when an individual or a group has met that standard.

But first, what and why did the DOE make this change? The One Big Beautiful Bill Act charged the DOE with reducing what it claims is massive overspending on graduate education by limiting the programs that meet the definition of a “professional degree” eligible for higher funding. Of my father’s 4, medicine (including dentistry) and law made the cut with students in those professions able to borrow up to $200,000 in direct unsubsidized student loans while those in other programs would be limited to $100,000.2

As one of the oldest and most respected professions in America, nursing has received the most media attention, yet there are also other important and valued professions that are missing from the DOE list.3 The excluded professions also include: physician assistants, physical therapists, audiologists, architects, accountants, educators, and social workers. The proposed regulatory changes are not yet finalized and Congressional representatives, health care experts, and a myriad of professional associations have rightly objected the reclassification will only worsen the critical shortage of nurses, teachers, and other helping professions the country is already facing.4

There are thousands of federal health care professionals who worked long and hard to achieve their goals whom this Act undervalues. Moreover, the regulatory change leaves many students enrolled in education and training programs under federal practice auspices confused and overwhelmed. Perhaps they can take some hope and inspiration from the recognition that historically and philosophically, no agency or administration can unilaterally define what is a profession.

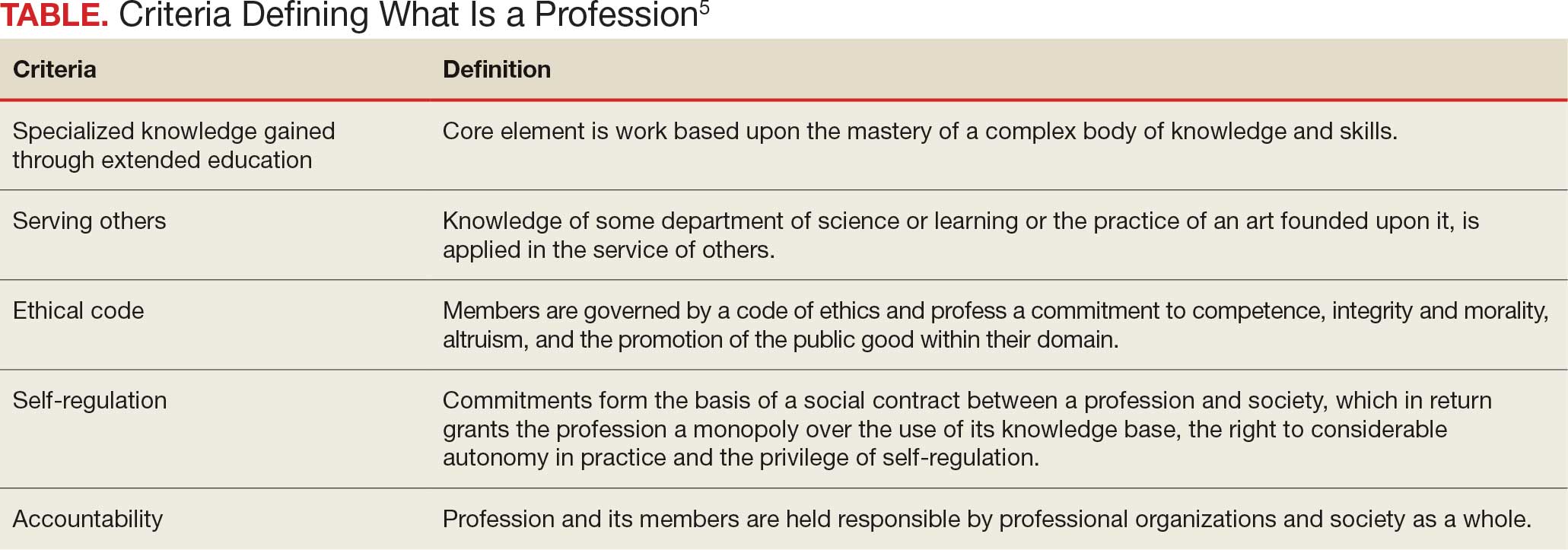

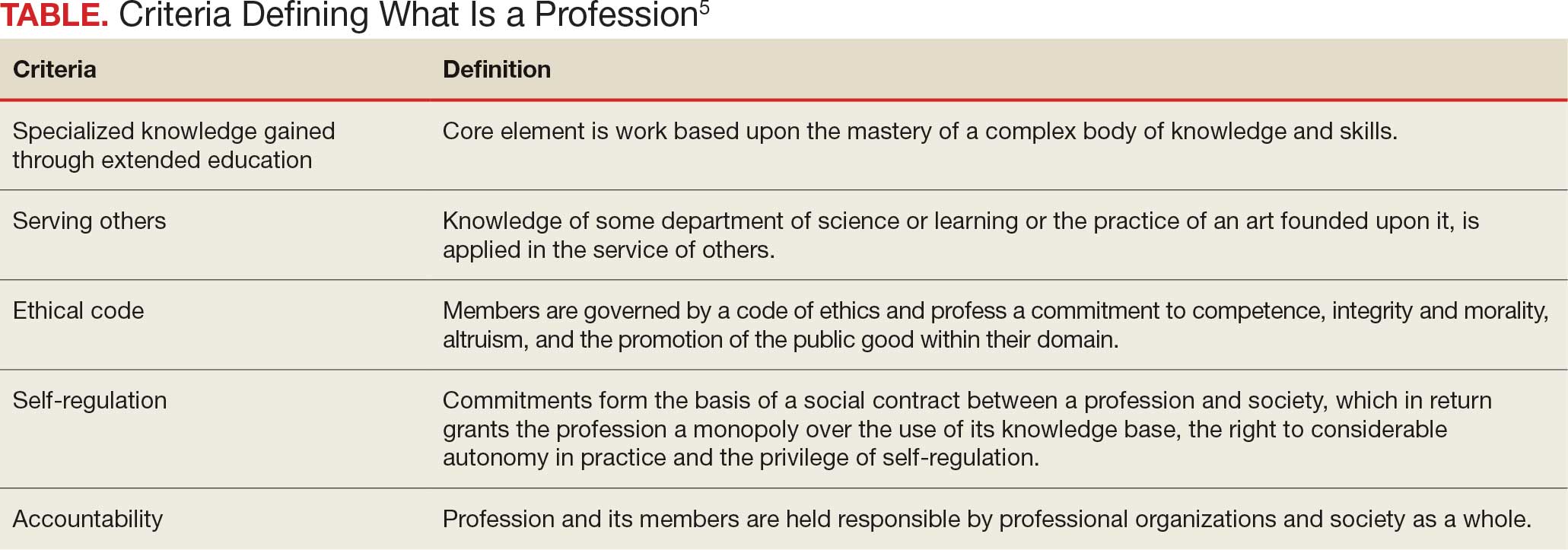

The literature on professionalism is voluminous, in large part because it has been surprisingly difficult to reach a consensus definition. A proposed definition from scholars captures most of the key aspects of a profession. While it is drawn from the medical literature, it applies to most of the caring professions the DOE disqualified. For pedagogic purposes, the definition is parsed into discrete criteria in the Table.5

Even this simple summary makes it obvious that a government agency alone could not possibly have the competence to determine who meets these complex technical and moral criteria. The members of the profession must assume a primary role in that determination. The complicated history of the professions shows that the locus of these decisions has resided in various combinations of educational institutions, such as nursing schools,6 professional societies (eg, National Association of Social Workers),7 and certifying boards (eg, National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants).8 States, not the federal government, have long played a key part in defining professions in the US, through their authority to grant licenses to practice.9

In response to criticism, the DOE has stated that “the definition of a ‘professional degree’ is an internal definition used by the Department of Education to distinguish among programs that qualify for higher loan limits, not a value judgment about the importance of programs. It has no bearing on whether a program is professional in nature or not.”2 Given the ancient compact between society and the professions in which the government subsidizes the training of professionals dedicated to public service, it is hard to see how these changes can be dismissed as merely semantic and not a promissory breach.10

I recognize that this abstract editorial is little comfort to beleaguered and demoralized professionals and students. Still, it offers a voice of support for each federal practitioner or trainee who fulfills the epigraph’s description of a professional day after day. The nurse who works the extra shift without complaint or resentment so that veterans receive the care they deserve, the social worker who responds on a weekend night to an active duty family without food so they do not spend another night hungry, and the physician assistant who makes it into the isolated public health clinic despite the terrible weather so there is someone ready to take care for patients in need. The proposed policy shift cannot in any meaningful sense rob them of their identity as individuals committed to a code of caring. However, without an intact social compact, it may well remove their practical ability to remain and enter the helping professions to the detriment of us all.

- Wade JW. Public responsibilities of the learned professions. Louisiana Law Rev. 1960;21:130-148

- US Department of Education. Myth vs. fact: the definition of professional degrees. Press Release. November 24, 2025. Accessed December 22, 2025. https://www.ed.gov/about/news/press-release/myth-vs-fact-definition-of-professional-degrees

- Laws J. Full list of degrees not classed as “professional” by Trump admin. Newsweek. Updated November 26, 2025. Accessed December 22, 2025. https://www.newsweek.com/full-list-degrees-professional-trump-administration-11085695

- New York Academy of Medicine. Response to stripping “professional status” as proposed by the Department of Education. New York Academy of Medicine. November 24, 2025. Accessed December 22, 2025. https://nyam.org/article/response-to-stripping-professional-status-as-proposed-by-the-department-of-education

- Cruess SR, Johnston S, Cruess RL. “Profession”: a working definition for medical educators. Teach Learn Med. 2004;16:74-76. doi:10.1207/s15328015tlm1601_15

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Nursing is a professional degree. American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Accessed December 20, 2025. https://www.aacnnursing.org/policy-advocacy/take-action/nursing-is-a-professional-degree

- National Association of Social Workers. Social work is a profession. Social Workers. Accessed December 20, 2025. https://www.socialworkers.org

- National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. Accessed December 20, 2025. https://www.nccpa.net/about-nccpa/#who-we-are

- The Federation of State Boards of Physical Therapy. Accessed December 20, 2025. https://www.fsbpt.org/About-Us/Staff-Home

- Cruess SR, Cruess RL. Professionalism and medicine’s contract with social contract with society. Virtual Mentor. 2004;6:185-188. doi:10.1001/virtualmentor.2004.6.4.msoc1-040

A professional is someone who can do his best work when he doesn’t feel like it.

Alistair Cooke

When I was a young person with no idea about growing up to be something, my father used to tell me there were 4 learned professions: medicine to heal the body, law to protect the body politic, teaching to nurture the mind, and the clergy to care for the soul.1 That adage, or some version of it, is attributed to a variety of sources, likely because it captures something essential and timeless about the learned professions. I write this as a much older person, and it has been my privilege to have worked in some capacity in all 4 of these venerable vocations.

There are many more recognized professions now than in my father’s time with new ones still emerging as the world becomes more complicated and specialized. In November 2025, however, the growth of the professions was dealt a serious blow when the US Department of Education (DOE) redefined what constitutes a profession for the purpose of federal funding of graduate degrees.2 The internet is understandably abuzz with opinions across the political spectrum. What is missing from many of these discussions is an understanding of the criteria for a profession and, even more importantly, who has the authority to decide when an individual or a group has met that standard.

But first, what and why did the DOE make this change? The One Big Beautiful Bill Act charged the DOE with reducing what it claims is massive overspending on graduate education by limiting the programs that meet the definition of a “professional degree” eligible for higher funding. Of my father’s 4, medicine (including dentistry) and law made the cut with students in those professions able to borrow up to $200,000 in direct unsubsidized student loans while those in other programs would be limited to $100,000.2

As one of the oldest and most respected professions in America, nursing has received the most media attention, yet there are also other important and valued professions that are missing from the DOE list.3 The excluded professions also include: physician assistants, physical therapists, audiologists, architects, accountants, educators, and social workers. The proposed regulatory changes are not yet finalized and Congressional representatives, health care experts, and a myriad of professional associations have rightly objected the reclassification will only worsen the critical shortage of nurses, teachers, and other helping professions the country is already facing.4

There are thousands of federal health care professionals who worked long and hard to achieve their goals whom this Act undervalues. Moreover, the regulatory change leaves many students enrolled in education and training programs under federal practice auspices confused and overwhelmed. Perhaps they can take some hope and inspiration from the recognition that historically and philosophically, no agency or administration can unilaterally define what is a profession.

The literature on professionalism is voluminous, in large part because it has been surprisingly difficult to reach a consensus definition. A proposed definition from scholars captures most of the key aspects of a profession. While it is drawn from the medical literature, it applies to most of the caring professions the DOE disqualified. For pedagogic purposes, the definition is parsed into discrete criteria in the Table.5

Even this simple summary makes it obvious that a government agency alone could not possibly have the competence to determine who meets these complex technical and moral criteria. The members of the profession must assume a primary role in that determination. The complicated history of the professions shows that the locus of these decisions has resided in various combinations of educational institutions, such as nursing schools,6 professional societies (eg, National Association of Social Workers),7 and certifying boards (eg, National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants).8 States, not the federal government, have long played a key part in defining professions in the US, through their authority to grant licenses to practice.9

In response to criticism, the DOE has stated that “the definition of a ‘professional degree’ is an internal definition used by the Department of Education to distinguish among programs that qualify for higher loan limits, not a value judgment about the importance of programs. It has no bearing on whether a program is professional in nature or not.”2 Given the ancient compact between society and the professions in which the government subsidizes the training of professionals dedicated to public service, it is hard to see how these changes can be dismissed as merely semantic and not a promissory breach.10

I recognize that this abstract editorial is little comfort to beleaguered and demoralized professionals and students. Still, it offers a voice of support for each federal practitioner or trainee who fulfills the epigraph’s description of a professional day after day. The nurse who works the extra shift without complaint or resentment so that veterans receive the care they deserve, the social worker who responds on a weekend night to an active duty family without food so they do not spend another night hungry, and the physician assistant who makes it into the isolated public health clinic despite the terrible weather so there is someone ready to take care for patients in need. The proposed policy shift cannot in any meaningful sense rob them of their identity as individuals committed to a code of caring. However, without an intact social compact, it may well remove their practical ability to remain and enter the helping professions to the detriment of us all.

A professional is someone who can do his best work when he doesn’t feel like it.

Alistair Cooke

When I was a young person with no idea about growing up to be something, my father used to tell me there were 4 learned professions: medicine to heal the body, law to protect the body politic, teaching to nurture the mind, and the clergy to care for the soul.1 That adage, or some version of it, is attributed to a variety of sources, likely because it captures something essential and timeless about the learned professions. I write this as a much older person, and it has been my privilege to have worked in some capacity in all 4 of these venerable vocations.

There are many more recognized professions now than in my father’s time with new ones still emerging as the world becomes more complicated and specialized. In November 2025, however, the growth of the professions was dealt a serious blow when the US Department of Education (DOE) redefined what constitutes a profession for the purpose of federal funding of graduate degrees.2 The internet is understandably abuzz with opinions across the political spectrum. What is missing from many of these discussions is an understanding of the criteria for a profession and, even more importantly, who has the authority to decide when an individual or a group has met that standard.

But first, what and why did the DOE make this change? The One Big Beautiful Bill Act charged the DOE with reducing what it claims is massive overspending on graduate education by limiting the programs that meet the definition of a “professional degree” eligible for higher funding. Of my father’s 4, medicine (including dentistry) and law made the cut with students in those professions able to borrow up to $200,000 in direct unsubsidized student loans while those in other programs would be limited to $100,000.2

As one of the oldest and most respected professions in America, nursing has received the most media attention, yet there are also other important and valued professions that are missing from the DOE list.3 The excluded professions also include: physician assistants, physical therapists, audiologists, architects, accountants, educators, and social workers. The proposed regulatory changes are not yet finalized and Congressional representatives, health care experts, and a myriad of professional associations have rightly objected the reclassification will only worsen the critical shortage of nurses, teachers, and other helping professions the country is already facing.4

There are thousands of federal health care professionals who worked long and hard to achieve their goals whom this Act undervalues. Moreover, the regulatory change leaves many students enrolled in education and training programs under federal practice auspices confused and overwhelmed. Perhaps they can take some hope and inspiration from the recognition that historically and philosophically, no agency or administration can unilaterally define what is a profession.

The literature on professionalism is voluminous, in large part because it has been surprisingly difficult to reach a consensus definition. A proposed definition from scholars captures most of the key aspects of a profession. While it is drawn from the medical literature, it applies to most of the caring professions the DOE disqualified. For pedagogic purposes, the definition is parsed into discrete criteria in the Table.5

Even this simple summary makes it obvious that a government agency alone could not possibly have the competence to determine who meets these complex technical and moral criteria. The members of the profession must assume a primary role in that determination. The complicated history of the professions shows that the locus of these decisions has resided in various combinations of educational institutions, such as nursing schools,6 professional societies (eg, National Association of Social Workers),7 and certifying boards (eg, National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants).8 States, not the federal government, have long played a key part in defining professions in the US, through their authority to grant licenses to practice.9

In response to criticism, the DOE has stated that “the definition of a ‘professional degree’ is an internal definition used by the Department of Education to distinguish among programs that qualify for higher loan limits, not a value judgment about the importance of programs. It has no bearing on whether a program is professional in nature or not.”2 Given the ancient compact between society and the professions in which the government subsidizes the training of professionals dedicated to public service, it is hard to see how these changes can be dismissed as merely semantic and not a promissory breach.10

I recognize that this abstract editorial is little comfort to beleaguered and demoralized professionals and students. Still, it offers a voice of support for each federal practitioner or trainee who fulfills the epigraph’s description of a professional day after day. The nurse who works the extra shift without complaint or resentment so that veterans receive the care they deserve, the social worker who responds on a weekend night to an active duty family without food so they do not spend another night hungry, and the physician assistant who makes it into the isolated public health clinic despite the terrible weather so there is someone ready to take care for patients in need. The proposed policy shift cannot in any meaningful sense rob them of their identity as individuals committed to a code of caring. However, without an intact social compact, it may well remove their practical ability to remain and enter the helping professions to the detriment of us all.

- Wade JW. Public responsibilities of the learned professions. Louisiana Law Rev. 1960;21:130-148

- US Department of Education. Myth vs. fact: the definition of professional degrees. Press Release. November 24, 2025. Accessed December 22, 2025. https://www.ed.gov/about/news/press-release/myth-vs-fact-definition-of-professional-degrees

- Laws J. Full list of degrees not classed as “professional” by Trump admin. Newsweek. Updated November 26, 2025. Accessed December 22, 2025. https://www.newsweek.com/full-list-degrees-professional-trump-administration-11085695

- New York Academy of Medicine. Response to stripping “professional status” as proposed by the Department of Education. New York Academy of Medicine. November 24, 2025. Accessed December 22, 2025. https://nyam.org/article/response-to-stripping-professional-status-as-proposed-by-the-department-of-education

- Cruess SR, Johnston S, Cruess RL. “Profession”: a working definition for medical educators. Teach Learn Med. 2004;16:74-76. doi:10.1207/s15328015tlm1601_15

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Nursing is a professional degree. American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Accessed December 20, 2025. https://www.aacnnursing.org/policy-advocacy/take-action/nursing-is-a-professional-degree

- National Association of Social Workers. Social work is a profession. Social Workers. Accessed December 20, 2025. https://www.socialworkers.org

- National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. Accessed December 20, 2025. https://www.nccpa.net/about-nccpa/#who-we-are

- The Federation of State Boards of Physical Therapy. Accessed December 20, 2025. https://www.fsbpt.org/About-Us/Staff-Home

- Cruess SR, Cruess RL. Professionalism and medicine’s contract with social contract with society. Virtual Mentor. 2004;6:185-188. doi:10.1001/virtualmentor.2004.6.4.msoc1-040

- Wade JW. Public responsibilities of the learned professions. Louisiana Law Rev. 1960;21:130-148

- US Department of Education. Myth vs. fact: the definition of professional degrees. Press Release. November 24, 2025. Accessed December 22, 2025. https://www.ed.gov/about/news/press-release/myth-vs-fact-definition-of-professional-degrees

- Laws J. Full list of degrees not classed as “professional” by Trump admin. Newsweek. Updated November 26, 2025. Accessed December 22, 2025. https://www.newsweek.com/full-list-degrees-professional-trump-administration-11085695

- New York Academy of Medicine. Response to stripping “professional status” as proposed by the Department of Education. New York Academy of Medicine. November 24, 2025. Accessed December 22, 2025. https://nyam.org/article/response-to-stripping-professional-status-as-proposed-by-the-department-of-education

- Cruess SR, Johnston S, Cruess RL. “Profession”: a working definition for medical educators. Teach Learn Med. 2004;16:74-76. doi:10.1207/s15328015tlm1601_15

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Nursing is a professional degree. American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Accessed December 20, 2025. https://www.aacnnursing.org/policy-advocacy/take-action/nursing-is-a-professional-degree

- National Association of Social Workers. Social work is a profession. Social Workers. Accessed December 20, 2025. https://www.socialworkers.org

- National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. Accessed December 20, 2025. https://www.nccpa.net/about-nccpa/#who-we-are

- The Federation of State Boards of Physical Therapy. Accessed December 20, 2025. https://www.fsbpt.org/About-Us/Staff-Home

- Cruess SR, Cruess RL. Professionalism and medicine’s contract with social contract with society. Virtual Mentor. 2004;6:185-188. doi:10.1001/virtualmentor.2004.6.4.msoc1-040

Codes, Contracts, and Commitments: Who Defines What is a Profession?

Codes, Contracts, and Commitments: Who Defines What is a Profession?

The Once and Future Veterans Health Administration

The Once and Future Veterans Health Administration

He who thus considers things in their first growth and origin ... will obtain the clearest view of them. Politics, Book I, Part II by Aristotle

Many seasoned observers of federal practice have signaled that the future of US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care is threatened as never before. Political forces and economic interests are siphoning Veterans Health Administration (VHA) capital and human resources into the community with an ineluctable push toward privatization.1

This Veterans Day, the vitality, if not the very viability of veteran health care, is in serious jeopardy, so it seems fitting to review the rationale for having institutions dedicated to the specialized medical treatment of veterans. Aristotle advises us on how to undertake this intellectual exercise in the epigraph. This column will revisit the historical origins of VA medicine to better appreciate the justification of an agency committed to this unique purpose and what may be sacrificed if it is decimated.

The provision of medical care focused on the injuries and illnesses of warriors is as old as war. The ancient Romans had among the first veterans’ hospital, named a valetudinarium. Sick and injured members of the Roman legions received state-of-the-art medical and surgical care from military doctors inside these facilities.2

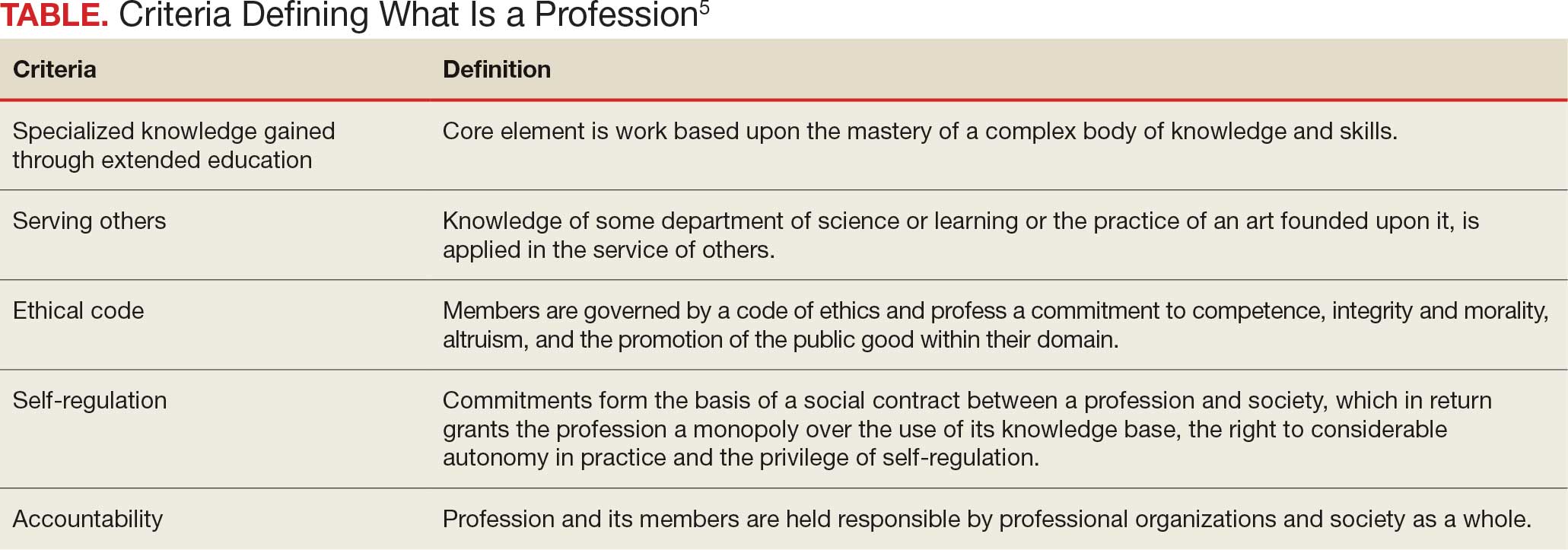

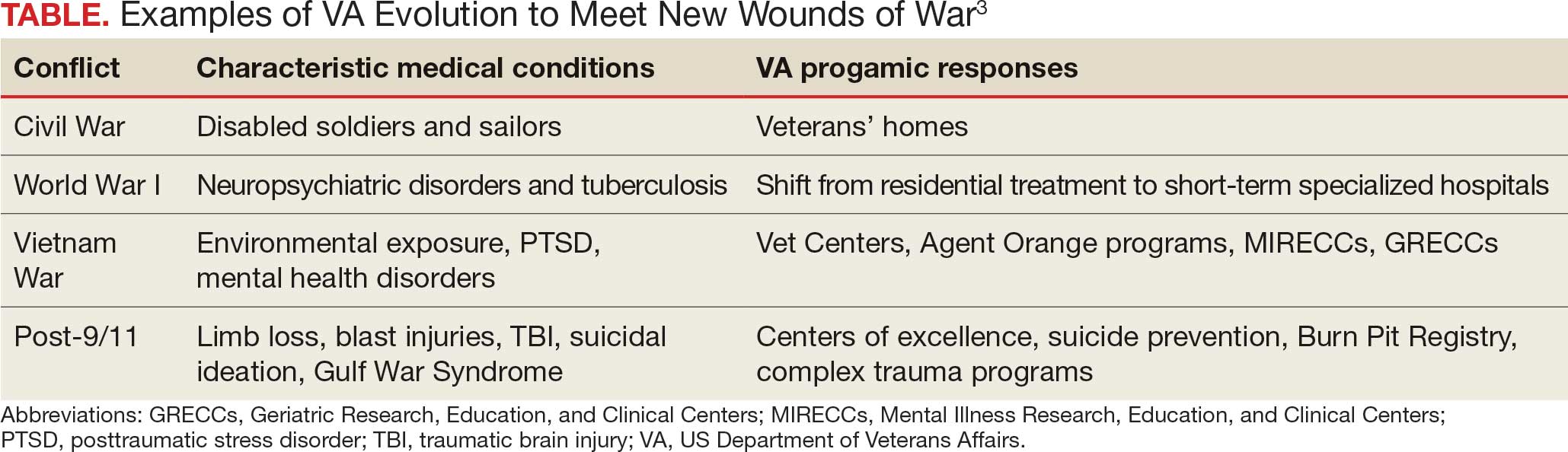

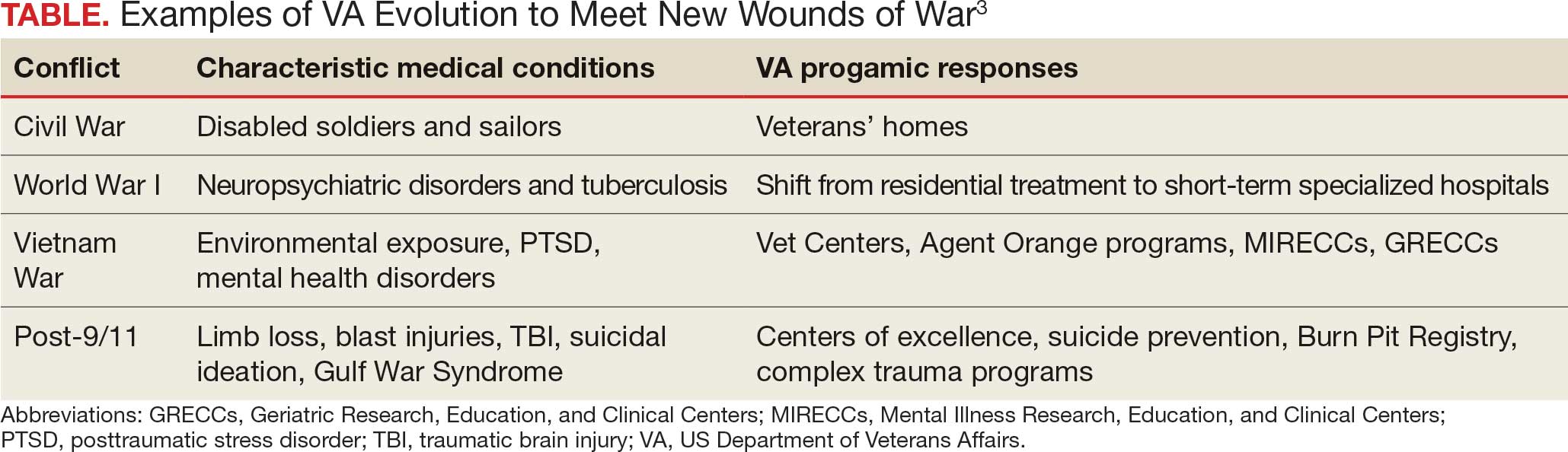

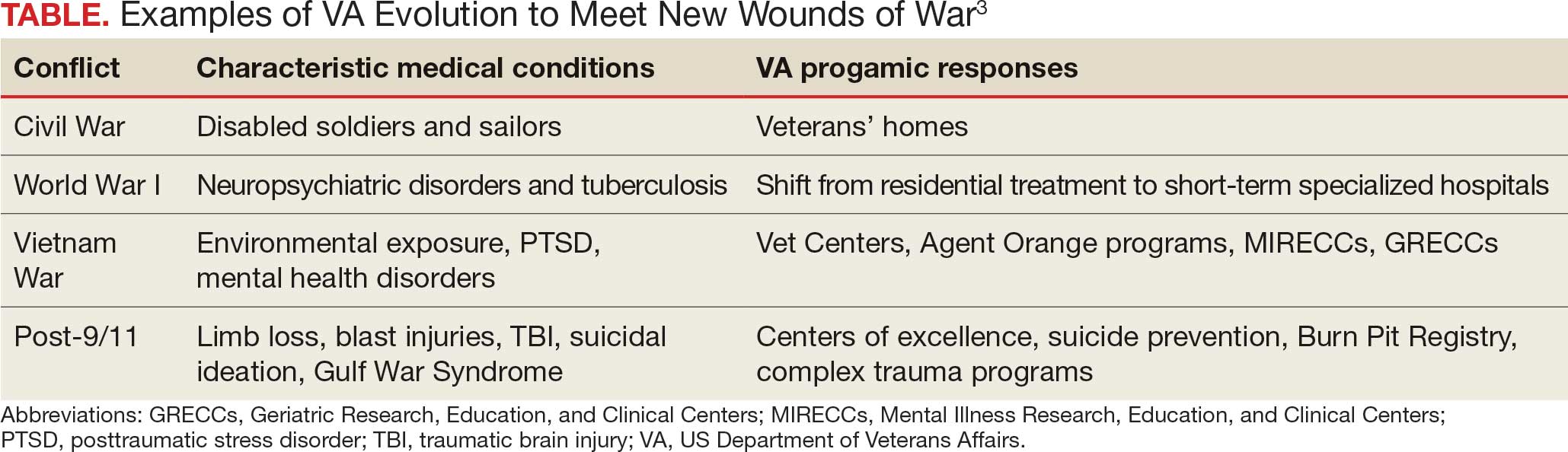

In the United States, federal practice emerged almost simultaneously with the birth of a nation. Wounded troops and families of slain soldiers required rehabilitation and support from the fledgling federal government. This began a pattern of development in which each war generated novel injuries and disorders that required the VA to evolve (Table).3

Many arguments can be marshalled to demonstrate the importance of not just ensuring VA health care survives but also has the resources needed to thrive. I will highlight what I argue are the most important justifications for its existence.

The ethical argument: President Abraham Lincoln and a long line of government officials for more than 2 centuries have called the provision of high-quality health care focused on veterans a sacred trust. Failing to fulfill that promise is a violation of the deepest principles of veracity and fidelity that those who govern owe to the citizens who selflessly sacrificed time, health, and even in some cases life, for the safety and well-being of their country.4

The quality argument: Dozens of studies have found that compared to the community, many areas of veteran medical care are just plain better. Two surveys particularly salient in the aging veteran population illustrate this growing body of positive research. The most recent and largest survey of Medicare patients found that VHA hospitals surpassed community-based hospitals on all 10 metrics.5 A retrospective cohort study of mortality compared veterans transported by ambulance to VHA or community-based hospitals. The researchers found that those taken to VHA facilities had a 30-day all cause adjustment mortality 20 times lower than those taken to civilian hospitals, especially among minoritized populations who generally have higher mortality.6

The cultural argument: Glance at almost any form of communication from veterans or about their health care and you will apprehend common cultural themes. Even when frustrated that the system has not lived up to their expectations, and perhaps because of their sense of belonging, they voice ownership of VHA as their medical home. Surveys of veteran experiences have shown many feel more comfortable receiving care in the company of comrades in arms and from health care professionals with expertise and experience with veterans’ distinctive medical problems and the military values that inform their preferences for care.7

The complexity argument: Anyone who has worked even a short time in a VHA hospital or clinic knows the patients are in general more complicated than similar patients in the community. Multiple medical, geriatric, neuropsychiatric, substance use, and social comorbidities are the expectation, not the exception, as in some civilian systems. Many of the conditions common in the VHA such as traumatic brain injury, service-connected cancers, suicidal ideation, environmental exposures, and posttraumatic stress disorder would be encountered in community health care settings. The differences between VHA and community care led the RAND Corporation to caution that “Community care providers might not be equipped to handle the needs of veterans.”8

Let me bring this 1000-foot view of the crisis facing federal practice down to the literal level of my own home. For many years I have had a wonderful mechanic who has a mobile bike service. I was talking to him as he fixed my trike. I never knew he was a Vietnam era veteran, and he didn’t realize that I was a career VA health care professional at the very VHA hospital where he received care. He spontaneously told me that, “when I first got out, the VA was awful, but now it is wonderful and they are so good to me. I would not go anywhere else.” For the many veterans of that era who would echo his sentiments, we must not allow the VA to lose all it has gained since that painful time

Another philosopher, Søren Kierkegaard, wrote that “life must be understood backwards but lived forwards.”9 Our own brief back to the future journey in this editorial has, I hope, shown that VHA medical institutions and health professionals cannot be replaced with or replicated by civilian systems and clinicians. Continued attempts to do so betray the trust and risks the health and well-being of veterans. It also would deprive the country of research, innovation, and education that make unparalleled contributions to public health. Ultimately, these efforts to diminish VHA compromise the solidarity of service members with each other and with their federal practitioners. If this trend to dismantle an organization that originated with the sole purpose of caring for veterans continues, then the public expressions of respect and gratitude will sound shallower and more tentative with each passing Veterans Day.

- Quil L. Hundreds of VA clinicians warn that cuts threaten vet’s health care. National Public Radio. October 1, 2025. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://www.npr.org/2025/10/01/nx-s1-5554394/hundreds-of-va-clinicians-warn-that-cuts-threaten-vets-health-care

- Nutton V. Ancient Medicine. 2nd ed. Routledge; 2012.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA History Summary. Updated June 13, 2025. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://department.va.gov/history/history-overview/

- Geppert CMA. Learning from history: the ethical foundation of VA health care. Fed Pract. 2016;33:6-7.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Nationwide patient survey shows VA hospitals outperform non-VA hospitals. News release. June 14, 2023. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://news.va.gov/press-room/nationwide-patient-survey-shows-va-hospitals-outperform-non-va-hospitals

- Chan DC, Danesh K, Costantini S, Card D, Taylor L, Studdert DM. Mortality among US veterans after emergency visits to Veterans Affairs and other hospitals: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2022;376:e068099. doi:10.1136/bmj-2021-068099

- Vigilante K, Batten SV, Shang Q, et al. Camaraderie among US veterans and their preferences for health care systems and practitioners. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8(4):e255253. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.5253

- Rasmussen P, Farmer CM. The promise and challenges of VA community care: veterans’ issues in focus. Rand Health Q. 2023;10:9.

- Kierkegaard S. Journalen JJ:167 (1843) in: Søren Kierkegaards Skrifter. Vol 18. Copenhagen; 1997:306.

He who thus considers things in their first growth and origin ... will obtain the clearest view of them. Politics, Book I, Part II by Aristotle

Many seasoned observers of federal practice have signaled that the future of US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care is threatened as never before. Political forces and economic interests are siphoning Veterans Health Administration (VHA) capital and human resources into the community with an ineluctable push toward privatization.1

This Veterans Day, the vitality, if not the very viability of veteran health care, is in serious jeopardy, so it seems fitting to review the rationale for having institutions dedicated to the specialized medical treatment of veterans. Aristotle advises us on how to undertake this intellectual exercise in the epigraph. This column will revisit the historical origins of VA medicine to better appreciate the justification of an agency committed to this unique purpose and what may be sacrificed if it is decimated.

The provision of medical care focused on the injuries and illnesses of warriors is as old as war. The ancient Romans had among the first veterans’ hospital, named a valetudinarium. Sick and injured members of the Roman legions received state-of-the-art medical and surgical care from military doctors inside these facilities.2

In the United States, federal practice emerged almost simultaneously with the birth of a nation. Wounded troops and families of slain soldiers required rehabilitation and support from the fledgling federal government. This began a pattern of development in which each war generated novel injuries and disorders that required the VA to evolve (Table).3

Many arguments can be marshalled to demonstrate the importance of not just ensuring VA health care survives but also has the resources needed to thrive. I will highlight what I argue are the most important justifications for its existence.

The ethical argument: President Abraham Lincoln and a long line of government officials for more than 2 centuries have called the provision of high-quality health care focused on veterans a sacred trust. Failing to fulfill that promise is a violation of the deepest principles of veracity and fidelity that those who govern owe to the citizens who selflessly sacrificed time, health, and even in some cases life, for the safety and well-being of their country.4

The quality argument: Dozens of studies have found that compared to the community, many areas of veteran medical care are just plain better. Two surveys particularly salient in the aging veteran population illustrate this growing body of positive research. The most recent and largest survey of Medicare patients found that VHA hospitals surpassed community-based hospitals on all 10 metrics.5 A retrospective cohort study of mortality compared veterans transported by ambulance to VHA or community-based hospitals. The researchers found that those taken to VHA facilities had a 30-day all cause adjustment mortality 20 times lower than those taken to civilian hospitals, especially among minoritized populations who generally have higher mortality.6

The cultural argument: Glance at almost any form of communication from veterans or about their health care and you will apprehend common cultural themes. Even when frustrated that the system has not lived up to their expectations, and perhaps because of their sense of belonging, they voice ownership of VHA as their medical home. Surveys of veteran experiences have shown many feel more comfortable receiving care in the company of comrades in arms and from health care professionals with expertise and experience with veterans’ distinctive medical problems and the military values that inform their preferences for care.7

The complexity argument: Anyone who has worked even a short time in a VHA hospital or clinic knows the patients are in general more complicated than similar patients in the community. Multiple medical, geriatric, neuropsychiatric, substance use, and social comorbidities are the expectation, not the exception, as in some civilian systems. Many of the conditions common in the VHA such as traumatic brain injury, service-connected cancers, suicidal ideation, environmental exposures, and posttraumatic stress disorder would be encountered in community health care settings. The differences between VHA and community care led the RAND Corporation to caution that “Community care providers might not be equipped to handle the needs of veterans.”8

Let me bring this 1000-foot view of the crisis facing federal practice down to the literal level of my own home. For many years I have had a wonderful mechanic who has a mobile bike service. I was talking to him as he fixed my trike. I never knew he was a Vietnam era veteran, and he didn’t realize that I was a career VA health care professional at the very VHA hospital where he received care. He spontaneously told me that, “when I first got out, the VA was awful, but now it is wonderful and they are so good to me. I would not go anywhere else.” For the many veterans of that era who would echo his sentiments, we must not allow the VA to lose all it has gained since that painful time

Another philosopher, Søren Kierkegaard, wrote that “life must be understood backwards but lived forwards.”9 Our own brief back to the future journey in this editorial has, I hope, shown that VHA medical institutions and health professionals cannot be replaced with or replicated by civilian systems and clinicians. Continued attempts to do so betray the trust and risks the health and well-being of veterans. It also would deprive the country of research, innovation, and education that make unparalleled contributions to public health. Ultimately, these efforts to diminish VHA compromise the solidarity of service members with each other and with their federal practitioners. If this trend to dismantle an organization that originated with the sole purpose of caring for veterans continues, then the public expressions of respect and gratitude will sound shallower and more tentative with each passing Veterans Day.

He who thus considers things in their first growth and origin ... will obtain the clearest view of them. Politics, Book I, Part II by Aristotle

Many seasoned observers of federal practice have signaled that the future of US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care is threatened as never before. Political forces and economic interests are siphoning Veterans Health Administration (VHA) capital and human resources into the community with an ineluctable push toward privatization.1

This Veterans Day, the vitality, if not the very viability of veteran health care, is in serious jeopardy, so it seems fitting to review the rationale for having institutions dedicated to the specialized medical treatment of veterans. Aristotle advises us on how to undertake this intellectual exercise in the epigraph. This column will revisit the historical origins of VA medicine to better appreciate the justification of an agency committed to this unique purpose and what may be sacrificed if it is decimated.

The provision of medical care focused on the injuries and illnesses of warriors is as old as war. The ancient Romans had among the first veterans’ hospital, named a valetudinarium. Sick and injured members of the Roman legions received state-of-the-art medical and surgical care from military doctors inside these facilities.2

In the United States, federal practice emerged almost simultaneously with the birth of a nation. Wounded troops and families of slain soldiers required rehabilitation and support from the fledgling federal government. This began a pattern of development in which each war generated novel injuries and disorders that required the VA to evolve (Table).3

Many arguments can be marshalled to demonstrate the importance of not just ensuring VA health care survives but also has the resources needed to thrive. I will highlight what I argue are the most important justifications for its existence.

The ethical argument: President Abraham Lincoln and a long line of government officials for more than 2 centuries have called the provision of high-quality health care focused on veterans a sacred trust. Failing to fulfill that promise is a violation of the deepest principles of veracity and fidelity that those who govern owe to the citizens who selflessly sacrificed time, health, and even in some cases life, for the safety and well-being of their country.4

The quality argument: Dozens of studies have found that compared to the community, many areas of veteran medical care are just plain better. Two surveys particularly salient in the aging veteran population illustrate this growing body of positive research. The most recent and largest survey of Medicare patients found that VHA hospitals surpassed community-based hospitals on all 10 metrics.5 A retrospective cohort study of mortality compared veterans transported by ambulance to VHA or community-based hospitals. The researchers found that those taken to VHA facilities had a 30-day all cause adjustment mortality 20 times lower than those taken to civilian hospitals, especially among minoritized populations who generally have higher mortality.6

The cultural argument: Glance at almost any form of communication from veterans or about their health care and you will apprehend common cultural themes. Even when frustrated that the system has not lived up to their expectations, and perhaps because of their sense of belonging, they voice ownership of VHA as their medical home. Surveys of veteran experiences have shown many feel more comfortable receiving care in the company of comrades in arms and from health care professionals with expertise and experience with veterans’ distinctive medical problems and the military values that inform their preferences for care.7

The complexity argument: Anyone who has worked even a short time in a VHA hospital or clinic knows the patients are in general more complicated than similar patients in the community. Multiple medical, geriatric, neuropsychiatric, substance use, and social comorbidities are the expectation, not the exception, as in some civilian systems. Many of the conditions common in the VHA such as traumatic brain injury, service-connected cancers, suicidal ideation, environmental exposures, and posttraumatic stress disorder would be encountered in community health care settings. The differences between VHA and community care led the RAND Corporation to caution that “Community care providers might not be equipped to handle the needs of veterans.”8

Let me bring this 1000-foot view of the crisis facing federal practice down to the literal level of my own home. For many years I have had a wonderful mechanic who has a mobile bike service. I was talking to him as he fixed my trike. I never knew he was a Vietnam era veteran, and he didn’t realize that I was a career VA health care professional at the very VHA hospital where he received care. He spontaneously told me that, “when I first got out, the VA was awful, but now it is wonderful and they are so good to me. I would not go anywhere else.” For the many veterans of that era who would echo his sentiments, we must not allow the VA to lose all it has gained since that painful time

Another philosopher, Søren Kierkegaard, wrote that “life must be understood backwards but lived forwards.”9 Our own brief back to the future journey in this editorial has, I hope, shown that VHA medical institutions and health professionals cannot be replaced with or replicated by civilian systems and clinicians. Continued attempts to do so betray the trust and risks the health and well-being of veterans. It also would deprive the country of research, innovation, and education that make unparalleled contributions to public health. Ultimately, these efforts to diminish VHA compromise the solidarity of service members with each other and with their federal practitioners. If this trend to dismantle an organization that originated with the sole purpose of caring for veterans continues, then the public expressions of respect and gratitude will sound shallower and more tentative with each passing Veterans Day.

- Quil L. Hundreds of VA clinicians warn that cuts threaten vet’s health care. National Public Radio. October 1, 2025. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://www.npr.org/2025/10/01/nx-s1-5554394/hundreds-of-va-clinicians-warn-that-cuts-threaten-vets-health-care

- Nutton V. Ancient Medicine. 2nd ed. Routledge; 2012.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA History Summary. Updated June 13, 2025. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://department.va.gov/history/history-overview/

- Geppert CMA. Learning from history: the ethical foundation of VA health care. Fed Pract. 2016;33:6-7.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Nationwide patient survey shows VA hospitals outperform non-VA hospitals. News release. June 14, 2023. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://news.va.gov/press-room/nationwide-patient-survey-shows-va-hospitals-outperform-non-va-hospitals

- Chan DC, Danesh K, Costantini S, Card D, Taylor L, Studdert DM. Mortality among US veterans after emergency visits to Veterans Affairs and other hospitals: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2022;376:e068099. doi:10.1136/bmj-2021-068099

- Vigilante K, Batten SV, Shang Q, et al. Camaraderie among US veterans and their preferences for health care systems and practitioners. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8(4):e255253. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.5253

- Rasmussen P, Farmer CM. The promise and challenges of VA community care: veterans’ issues in focus. Rand Health Q. 2023;10:9.

- Kierkegaard S. Journalen JJ:167 (1843) in: Søren Kierkegaards Skrifter. Vol 18. Copenhagen; 1997:306.

- Quil L. Hundreds of VA clinicians warn that cuts threaten vet’s health care. National Public Radio. October 1, 2025. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://www.npr.org/2025/10/01/nx-s1-5554394/hundreds-of-va-clinicians-warn-that-cuts-threaten-vets-health-care

- Nutton V. Ancient Medicine. 2nd ed. Routledge; 2012.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA History Summary. Updated June 13, 2025. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://department.va.gov/history/history-overview/

- Geppert CMA. Learning from history: the ethical foundation of VA health care. Fed Pract. 2016;33:6-7.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Nationwide patient survey shows VA hospitals outperform non-VA hospitals. News release. June 14, 2023. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://news.va.gov/press-room/nationwide-patient-survey-shows-va-hospitals-outperform-non-va-hospitals

- Chan DC, Danesh K, Costantini S, Card D, Taylor L, Studdert DM. Mortality among US veterans after emergency visits to Veterans Affairs and other hospitals: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2022;376:e068099. doi:10.1136/bmj-2021-068099

- Vigilante K, Batten SV, Shang Q, et al. Camaraderie among US veterans and their preferences for health care systems and practitioners. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8(4):e255253. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.5253

- Rasmussen P, Farmer CM. The promise and challenges of VA community care: veterans’ issues in focus. Rand Health Q. 2023;10:9.

- Kierkegaard S. Journalen JJ:167 (1843) in: Søren Kierkegaards Skrifter. Vol 18. Copenhagen; 1997:306.

The Once and Future Veterans Health Administration

The Once and Future Veterans Health Administration

VHA Facilities Report Severe Staffing Shortages

VHA Facilities Report Severe Staffing Shortages

For > 10 years, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Office of Inspector General (OIG) has annually surveyed Veterans Health Administration (VHA) facilities about staffing. Its recently released report is the 8th to find severe shortages—in this case, across the board. There were 4434 severe staffing shortages reported across all 139 VHA facilities in fiscal year (FY) 2025, a 50% increase from FY 2024.

In the OIG report lexicon, a severe shortage refers to "particular occupations that are difficult to fill," and is not necessarily an indication of vacancies. Vacancy refers to a "specific unoccupied position and is distinct from the designation of a severe shortage." For example, a facility could identify an occupation as a severe occupational shortage, which could have no vacant positions or 100 vacant positions.

Nearly all facilities (94%) had severe shortages for medical officers, and 79% had severe shortages for nurses even with VHA's ability to make noncompetitive appointments for those occupations. Psychology was the most frequently reported severe clinical occupational staffing shortage, reported by 79 facilities (57%), down slightly from FY 2024 (61%). One facility reported 116 clinical occupational shortages.

The report notes that the OIG does not verify or otherwise confirm the questionnaire responses, but it appears to support other data. In the first 9 months of FY 2024, the VA added 223 physicians and 3196 nurses compared with a deficit of 781 physicians and 2129 nurses over the same period in FY 2025.

VHA facilities are finding it hard to reverse the trend. According to internal documents examined by ProPublica, nearly 4 in 10 of the roughly 2000 doctors offered jobs from January through March 2025 turned them down, 4 times the rate in the same time period in 2024. VHA also lost twice as many nurses as it hired between January and June. Many potential candidates reportedly were worried about the stability of VA employment.

VA spokesperson Peter Kasperowicz did not dispute the ProPublica findings but accused the news outlet of bias and "cherry-picking issues that are mostly routine." A nationwide shortage of health care workers has made hiring and retention difficult, he said.

Kasperowicz said the VA is "working to address" the number of doctors declining job offers by speeding up the hiring process and that the agency "has several strategies to navigate shortages." Those include referring veterans to telehealth and private clinicians.

In a statement released Aug. 12, Sen Richard Blumenthal (D-CT), ranking member of the Senate Committee on Veterans' Affairs, said, "This report confirms what we've warned for months—this Administration is driving dedicated VA employees to the private sector at untenable rates."

The OIG survey did not ask about facilities' rationales for identifying shortages. Moreover, the OIG says the responses don't reflect the possible impacts of "workforce reshaping efforts," such as the Deferred Resignation Program announced on January 28, 2025.

In response to the OIG report, Kasperowicz said it is "not based on actual VA health care facility vacancies and therefore is not a reliable indicator of staffing shortages." In a statement to CBS News, he added, "The report simply lists occupations facilities feel are difficult for which to recruit and retain, so the results are completely subjective, not standardized, and unreliable." According to Kasperowicz, the system-wide vacancy rates for doctors and nurses are 14% and 10%, respectively, which are in line with historical averages.

The OIG made no recommendations but "encourages VA leaders to use these review results to inform staffing initiatives and organizational change."

For > 10 years, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Office of Inspector General (OIG) has annually surveyed Veterans Health Administration (VHA) facilities about staffing. Its recently released report is the 8th to find severe shortages—in this case, across the board. There were 4434 severe staffing shortages reported across all 139 VHA facilities in fiscal year (FY) 2025, a 50% increase from FY 2024.

In the OIG report lexicon, a severe shortage refers to "particular occupations that are difficult to fill," and is not necessarily an indication of vacancies. Vacancy refers to a "specific unoccupied position and is distinct from the designation of a severe shortage." For example, a facility could identify an occupation as a severe occupational shortage, which could have no vacant positions or 100 vacant positions.

Nearly all facilities (94%) had severe shortages for medical officers, and 79% had severe shortages for nurses even with VHA's ability to make noncompetitive appointments for those occupations. Psychology was the most frequently reported severe clinical occupational staffing shortage, reported by 79 facilities (57%), down slightly from FY 2024 (61%). One facility reported 116 clinical occupational shortages.

The report notes that the OIG does not verify or otherwise confirm the questionnaire responses, but it appears to support other data. In the first 9 months of FY 2024, the VA added 223 physicians and 3196 nurses compared with a deficit of 781 physicians and 2129 nurses over the same period in FY 2025.

VHA facilities are finding it hard to reverse the trend. According to internal documents examined by ProPublica, nearly 4 in 10 of the roughly 2000 doctors offered jobs from January through March 2025 turned them down, 4 times the rate in the same time period in 2024. VHA also lost twice as many nurses as it hired between January and June. Many potential candidates reportedly were worried about the stability of VA employment.

VA spokesperson Peter Kasperowicz did not dispute the ProPublica findings but accused the news outlet of bias and "cherry-picking issues that are mostly routine." A nationwide shortage of health care workers has made hiring and retention difficult, he said.

Kasperowicz said the VA is "working to address" the number of doctors declining job offers by speeding up the hiring process and that the agency "has several strategies to navigate shortages." Those include referring veterans to telehealth and private clinicians.

In a statement released Aug. 12, Sen Richard Blumenthal (D-CT), ranking member of the Senate Committee on Veterans' Affairs, said, "This report confirms what we've warned for months—this Administration is driving dedicated VA employees to the private sector at untenable rates."

The OIG survey did not ask about facilities' rationales for identifying shortages. Moreover, the OIG says the responses don't reflect the possible impacts of "workforce reshaping efforts," such as the Deferred Resignation Program announced on January 28, 2025.

In response to the OIG report, Kasperowicz said it is "not based on actual VA health care facility vacancies and therefore is not a reliable indicator of staffing shortages." In a statement to CBS News, he added, "The report simply lists occupations facilities feel are difficult for which to recruit and retain, so the results are completely subjective, not standardized, and unreliable." According to Kasperowicz, the system-wide vacancy rates for doctors and nurses are 14% and 10%, respectively, which are in line with historical averages.

The OIG made no recommendations but "encourages VA leaders to use these review results to inform staffing initiatives and organizational change."

For > 10 years, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Office of Inspector General (OIG) has annually surveyed Veterans Health Administration (VHA) facilities about staffing. Its recently released report is the 8th to find severe shortages—in this case, across the board. There were 4434 severe staffing shortages reported across all 139 VHA facilities in fiscal year (FY) 2025, a 50% increase from FY 2024.

In the OIG report lexicon, a severe shortage refers to "particular occupations that are difficult to fill," and is not necessarily an indication of vacancies. Vacancy refers to a "specific unoccupied position and is distinct from the designation of a severe shortage." For example, a facility could identify an occupation as a severe occupational shortage, which could have no vacant positions or 100 vacant positions.

Nearly all facilities (94%) had severe shortages for medical officers, and 79% had severe shortages for nurses even with VHA's ability to make noncompetitive appointments for those occupations. Psychology was the most frequently reported severe clinical occupational staffing shortage, reported by 79 facilities (57%), down slightly from FY 2024 (61%). One facility reported 116 clinical occupational shortages.

The report notes that the OIG does not verify or otherwise confirm the questionnaire responses, but it appears to support other data. In the first 9 months of FY 2024, the VA added 223 physicians and 3196 nurses compared with a deficit of 781 physicians and 2129 nurses over the same period in FY 2025.

VHA facilities are finding it hard to reverse the trend. According to internal documents examined by ProPublica, nearly 4 in 10 of the roughly 2000 doctors offered jobs from January through March 2025 turned them down, 4 times the rate in the same time period in 2024. VHA also lost twice as many nurses as it hired between January and June. Many potential candidates reportedly were worried about the stability of VA employment.

VA spokesperson Peter Kasperowicz did not dispute the ProPublica findings but accused the news outlet of bias and "cherry-picking issues that are mostly routine." A nationwide shortage of health care workers has made hiring and retention difficult, he said.

Kasperowicz said the VA is "working to address" the number of doctors declining job offers by speeding up the hiring process and that the agency "has several strategies to navigate shortages." Those include referring veterans to telehealth and private clinicians.

In a statement released Aug. 12, Sen Richard Blumenthal (D-CT), ranking member of the Senate Committee on Veterans' Affairs, said, "This report confirms what we've warned for months—this Administration is driving dedicated VA employees to the private sector at untenable rates."

The OIG survey did not ask about facilities' rationales for identifying shortages. Moreover, the OIG says the responses don't reflect the possible impacts of "workforce reshaping efforts," such as the Deferred Resignation Program announced on January 28, 2025.

In response to the OIG report, Kasperowicz said it is "not based on actual VA health care facility vacancies and therefore is not a reliable indicator of staffing shortages." In a statement to CBS News, he added, "The report simply lists occupations facilities feel are difficult for which to recruit and retain, so the results are completely subjective, not standardized, and unreliable." According to Kasperowicz, the system-wide vacancy rates for doctors and nurses are 14% and 10%, respectively, which are in line with historical averages.

The OIG made no recommendations but "encourages VA leaders to use these review results to inform staffing initiatives and organizational change."

VHA Facilities Report Severe Staffing Shortages

VHA Facilities Report Severe Staffing Shortages

VA Workforce Shrinking as it Loses Collective Bargaining Rights

VA Workforce Shrinking as it Loses Collective Bargaining Rights

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is on pace to cut nearly 30,000 positions by the end of fiscal year 2025, an initiative driven by a federal hiring freeze, deferred resignations, retirements, and normal attrition. According to the VA Workforce Dashboard, health care experienced the most significant net change through the first 9 months of fiscal year 2025. That included 2129 fewer registered nurses, 751 fewer physicians, and drops of 565 licensed practical nurses, 564 nurse assistants, and 1294 medical support assistants. In total, nearly 17,000 VA employees have left their jobs and 12,000 more are expected to leave by the end of September 2025.

According to VA Secretary Doug Collins, the departures have eliminated the need for the "large-scale" reduction-in-force that he proposed earlier in 2025.

The VA also announced that in accordance with an Executive Order issued by President Donald Trump, it is terminating collective bargaining rights for most of its employees, including most clinical staff not in leadership positions. The order includes the National Nurses Organizing Committee/National Nurses United, which represents 16,000 VA nurses, and the American Federation of Government Employees, which represents 320,000 VA employees. The order exempted police officers, firefighters, and security guards. The Unions have indicated they will continue to fight the changes.

VA staffing has undergone significant reversals over the past year. The VA added 223 physicians and 3196 nurses in the first 9 months of fiscal year 2024 before reversing course this year. According to the Workforce Dashboard, the VA and Veterans Health Administration combined to hire 26,984 employees in fiscal year 2025. Cumulative losses, however, totaled 54,308.

During exit interviews, VA employees noted a variety of reasons for their departure. "Personal/family matters" and "geographic relocation" were cited by many job categories. In addition, medical and dental workers also noted "poor working relationship with supervisor or coworker(s)," "desired work schedule not offered," and "job stress/pressure" among the causes. The VA has lost 148 psychologists in fiscal year 2025 who cited "lack of trust/confidence in senior leaders," as well as "policy or technology barriers to getting the work done," and "job stress/pressure" among their reasons for departure.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is on pace to cut nearly 30,000 positions by the end of fiscal year 2025, an initiative driven by a federal hiring freeze, deferred resignations, retirements, and normal attrition. According to the VA Workforce Dashboard, health care experienced the most significant net change through the first 9 months of fiscal year 2025. That included 2129 fewer registered nurses, 751 fewer physicians, and drops of 565 licensed practical nurses, 564 nurse assistants, and 1294 medical support assistants. In total, nearly 17,000 VA employees have left their jobs and 12,000 more are expected to leave by the end of September 2025.

According to VA Secretary Doug Collins, the departures have eliminated the need for the "large-scale" reduction-in-force that he proposed earlier in 2025.

The VA also announced that in accordance with an Executive Order issued by President Donald Trump, it is terminating collective bargaining rights for most of its employees, including most clinical staff not in leadership positions. The order includes the National Nurses Organizing Committee/National Nurses United, which represents 16,000 VA nurses, and the American Federation of Government Employees, which represents 320,000 VA employees. The order exempted police officers, firefighters, and security guards. The Unions have indicated they will continue to fight the changes.

VA staffing has undergone significant reversals over the past year. The VA added 223 physicians and 3196 nurses in the first 9 months of fiscal year 2024 before reversing course this year. According to the Workforce Dashboard, the VA and Veterans Health Administration combined to hire 26,984 employees in fiscal year 2025. Cumulative losses, however, totaled 54,308.

During exit interviews, VA employees noted a variety of reasons for their departure. "Personal/family matters" and "geographic relocation" were cited by many job categories. In addition, medical and dental workers also noted "poor working relationship with supervisor or coworker(s)," "desired work schedule not offered," and "job stress/pressure" among the causes. The VA has lost 148 psychologists in fiscal year 2025 who cited "lack of trust/confidence in senior leaders," as well as "policy or technology barriers to getting the work done," and "job stress/pressure" among their reasons for departure.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is on pace to cut nearly 30,000 positions by the end of fiscal year 2025, an initiative driven by a federal hiring freeze, deferred resignations, retirements, and normal attrition. According to the VA Workforce Dashboard, health care experienced the most significant net change through the first 9 months of fiscal year 2025. That included 2129 fewer registered nurses, 751 fewer physicians, and drops of 565 licensed practical nurses, 564 nurse assistants, and 1294 medical support assistants. In total, nearly 17,000 VA employees have left their jobs and 12,000 more are expected to leave by the end of September 2025.

According to VA Secretary Doug Collins, the departures have eliminated the need for the "large-scale" reduction-in-force that he proposed earlier in 2025.

The VA also announced that in accordance with an Executive Order issued by President Donald Trump, it is terminating collective bargaining rights for most of its employees, including most clinical staff not in leadership positions. The order includes the National Nurses Organizing Committee/National Nurses United, which represents 16,000 VA nurses, and the American Federation of Government Employees, which represents 320,000 VA employees. The order exempted police officers, firefighters, and security guards. The Unions have indicated they will continue to fight the changes.

VA staffing has undergone significant reversals over the past year. The VA added 223 physicians and 3196 nurses in the first 9 months of fiscal year 2024 before reversing course this year. According to the Workforce Dashboard, the VA and Veterans Health Administration combined to hire 26,984 employees in fiscal year 2025. Cumulative losses, however, totaled 54,308.

During exit interviews, VA employees noted a variety of reasons for their departure. "Personal/family matters" and "geographic relocation" were cited by many job categories. In addition, medical and dental workers also noted "poor working relationship with supervisor or coworker(s)," "desired work schedule not offered," and "job stress/pressure" among the causes. The VA has lost 148 psychologists in fiscal year 2025 who cited "lack of trust/confidence in senior leaders," as well as "policy or technology barriers to getting the work done," and "job stress/pressure" among their reasons for departure.

VA Workforce Shrinking as it Loses Collective Bargaining Rights

VA Workforce Shrinking as it Loses Collective Bargaining Rights

AVAHO Encourages Members to Make Voices Heard

Advocacy for veterans with cancer has always been a central part of the Association for VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO) mission, but that advocacy has now taken on a new focus: the fate of US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) employees. The advocacy portal provides templated letters, a search function to find local Senators and Members of Congress, a search function to find regional media outlets, updates on voting and elections, and information on key legislation relevant to VA health care.

To ensure its members’ concerns are heard, AVAHO is encouraging members, in their own time and as private citizens, to contact their local representatives to inform them about the real impact of recent policy changes on VA employees and the veterans they care for. Members can select any of 4 letters focused on reductions in force, cancellation of VA contracts, the return to office mandate, and the National Institutes of Health’s proposed cap on indirect cost for research grants: “AVAHO recognizes the power of the individual voice. Our members have an important role in shaping the health care services provided to veterans across our nation.”

"The contracts that have been canceled and continue to be canceled included critical services related to cancer care," AVAHO notes on its Advocacy page. "We know these impacted contracts have hindered the VA’s ability to implement research protocols, process and report pharmacogenomic results, manage Electronic Health Record Modernization workgroups responsible for safety improvements, and execute new oncology services through the Close to Me initiative, just to name a few."

Advocacy for veterans with cancer has always been a central part of the Association for VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO) mission, but that advocacy has now taken on a new focus: the fate of US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) employees. The advocacy portal provides templated letters, a search function to find local Senators and Members of Congress, a search function to find regional media outlets, updates on voting and elections, and information on key legislation relevant to VA health care.

To ensure its members’ concerns are heard, AVAHO is encouraging members, in their own time and as private citizens, to contact their local representatives to inform them about the real impact of recent policy changes on VA employees and the veterans they care for. Members can select any of 4 letters focused on reductions in force, cancellation of VA contracts, the return to office mandate, and the National Institutes of Health’s proposed cap on indirect cost for research grants: “AVAHO recognizes the power of the individual voice. Our members have an important role in shaping the health care services provided to veterans across our nation.”

"The contracts that have been canceled and continue to be canceled included critical services related to cancer care," AVAHO notes on its Advocacy page. "We know these impacted contracts have hindered the VA’s ability to implement research protocols, process and report pharmacogenomic results, manage Electronic Health Record Modernization workgroups responsible for safety improvements, and execute new oncology services through the Close to Me initiative, just to name a few."

Advocacy for veterans with cancer has always been a central part of the Association for VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO) mission, but that advocacy has now taken on a new focus: the fate of US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) employees. The advocacy portal provides templated letters, a search function to find local Senators and Members of Congress, a search function to find regional media outlets, updates on voting and elections, and information on key legislation relevant to VA health care.

To ensure its members’ concerns are heard, AVAHO is encouraging members, in their own time and as private citizens, to contact their local representatives to inform them about the real impact of recent policy changes on VA employees and the veterans they care for. Members can select any of 4 letters focused on reductions in force, cancellation of VA contracts, the return to office mandate, and the National Institutes of Health’s proposed cap on indirect cost for research grants: “AVAHO recognizes the power of the individual voice. Our members have an important role in shaping the health care services provided to veterans across our nation.”

"The contracts that have been canceled and continue to be canceled included critical services related to cancer care," AVAHO notes on its Advocacy page. "We know these impacted contracts have hindered the VA’s ability to implement research protocols, process and report pharmacogenomic results, manage Electronic Health Record Modernization workgroups responsible for safety improvements, and execute new oncology services through the Close to Me initiative, just to name a few."

VA Choice Bill Defeated in the House

A U.S. House of Representatives appropriation to fund the Veterans Choice Program surprisingly went down to defeat on Monday. The VA Choice Program is set to run out of money in September, and VA officials have been calling for Congress to provide additional funding for the program. Republican leaders, hoping to expedite the bill’s passage and thinking that it was not controversial, submitted the bill in a process that required the votes of two-thirds of the representatives. The 219-186 vote fell well short of the necessary two-thirds, and voting fell largely along party lines.

Many veterans service organizations (VSOs) were critical of the bill and called on the House to make substantial changes to it. Seven VSOs signed a joint statement calling for the bill’s defeat. “As organizations who represent and support the interests of America’s 21 million veterans, and in fulfillment of our mandate to ensure that the men and women who served are able to receive the health care and benefits they need and deserve, we are calling on Members of Congress to defeat the House vote on unacceptable choice funding legislation (S. 114, with amendments),” the statement read.

AMVETS, Disabled American Veterans , Military Officers Association of America, Military Order of the Purple Heart, Veterans of Foreign Wars, Vietnam Veterans of America, and Wounded Warrior Project all signed on to the statement. The chief complaint was that the legislation “includes funding only for the ‘choice’ program which provides additional community care options, but makes no investment in VA and uses ‘savings’ from other veterans benefits or services to ‘pay’ for the ‘choice’ program.”

The bill would have allocated $2 billion for the Veterans Choice Program, taken funding for veteran housing loan fees, and would reduce the pensions for some veterans living in nursing facilities that also could be paid for under the Medicaid program.

The fate of the bill and funding for the Veterans Choice Program remains unclear. Senate and House veterans committees seem to be far apart on how to fund the program and for efforts to make more substantive changes to the program. Although House Republicans eventually may be able to pass a bill without Democrats, in the Senate, they will need the support of at least a handful of Democrats to move the bill to the President’s desk.

A U.S. House of Representatives appropriation to fund the Veterans Choice Program surprisingly went down to defeat on Monday. The VA Choice Program is set to run out of money in September, and VA officials have been calling for Congress to provide additional funding for the program. Republican leaders, hoping to expedite the bill’s passage and thinking that it was not controversial, submitted the bill in a process that required the votes of two-thirds of the representatives. The 219-186 vote fell well short of the necessary two-thirds, and voting fell largely along party lines.

Many veterans service organizations (VSOs) were critical of the bill and called on the House to make substantial changes to it. Seven VSOs signed a joint statement calling for the bill’s defeat. “As organizations who represent and support the interests of America’s 21 million veterans, and in fulfillment of our mandate to ensure that the men and women who served are able to receive the health care and benefits they need and deserve, we are calling on Members of Congress to defeat the House vote on unacceptable choice funding legislation (S. 114, with amendments),” the statement read.

AMVETS, Disabled American Veterans , Military Officers Association of America, Military Order of the Purple Heart, Veterans of Foreign Wars, Vietnam Veterans of America, and Wounded Warrior Project all signed on to the statement. The chief complaint was that the legislation “includes funding only for the ‘choice’ program which provides additional community care options, but makes no investment in VA and uses ‘savings’ from other veterans benefits or services to ‘pay’ for the ‘choice’ program.”

The bill would have allocated $2 billion for the Veterans Choice Program, taken funding for veteran housing loan fees, and would reduce the pensions for some veterans living in nursing facilities that also could be paid for under the Medicaid program.

The fate of the bill and funding for the Veterans Choice Program remains unclear. Senate and House veterans committees seem to be far apart on how to fund the program and for efforts to make more substantive changes to the program. Although House Republicans eventually may be able to pass a bill without Democrats, in the Senate, they will need the support of at least a handful of Democrats to move the bill to the President’s desk.

A U.S. House of Representatives appropriation to fund the Veterans Choice Program surprisingly went down to defeat on Monday. The VA Choice Program is set to run out of money in September, and VA officials have been calling for Congress to provide additional funding for the program. Republican leaders, hoping to expedite the bill’s passage and thinking that it was not controversial, submitted the bill in a process that required the votes of two-thirds of the representatives. The 219-186 vote fell well short of the necessary two-thirds, and voting fell largely along party lines.

Many veterans service organizations (VSOs) were critical of the bill and called on the House to make substantial changes to it. Seven VSOs signed a joint statement calling for the bill’s defeat. “As organizations who represent and support the interests of America’s 21 million veterans, and in fulfillment of our mandate to ensure that the men and women who served are able to receive the health care and benefits they need and deserve, we are calling on Members of Congress to defeat the House vote on unacceptable choice funding legislation (S. 114, with amendments),” the statement read.

AMVETS, Disabled American Veterans , Military Officers Association of America, Military Order of the Purple Heart, Veterans of Foreign Wars, Vietnam Veterans of America, and Wounded Warrior Project all signed on to the statement. The chief complaint was that the legislation “includes funding only for the ‘choice’ program which provides additional community care options, but makes no investment in VA and uses ‘savings’ from other veterans benefits or services to ‘pay’ for the ‘choice’ program.”

The bill would have allocated $2 billion for the Veterans Choice Program, taken funding for veteran housing loan fees, and would reduce the pensions for some veterans living in nursing facilities that also could be paid for under the Medicaid program.

The fate of the bill and funding for the Veterans Choice Program remains unclear. Senate and House veterans committees seem to be far apart on how to fund the program and for efforts to make more substantive changes to the program. Although House Republicans eventually may be able to pass a bill without Democrats, in the Senate, they will need the support of at least a handful of Democrats to move the bill to the President’s desk.

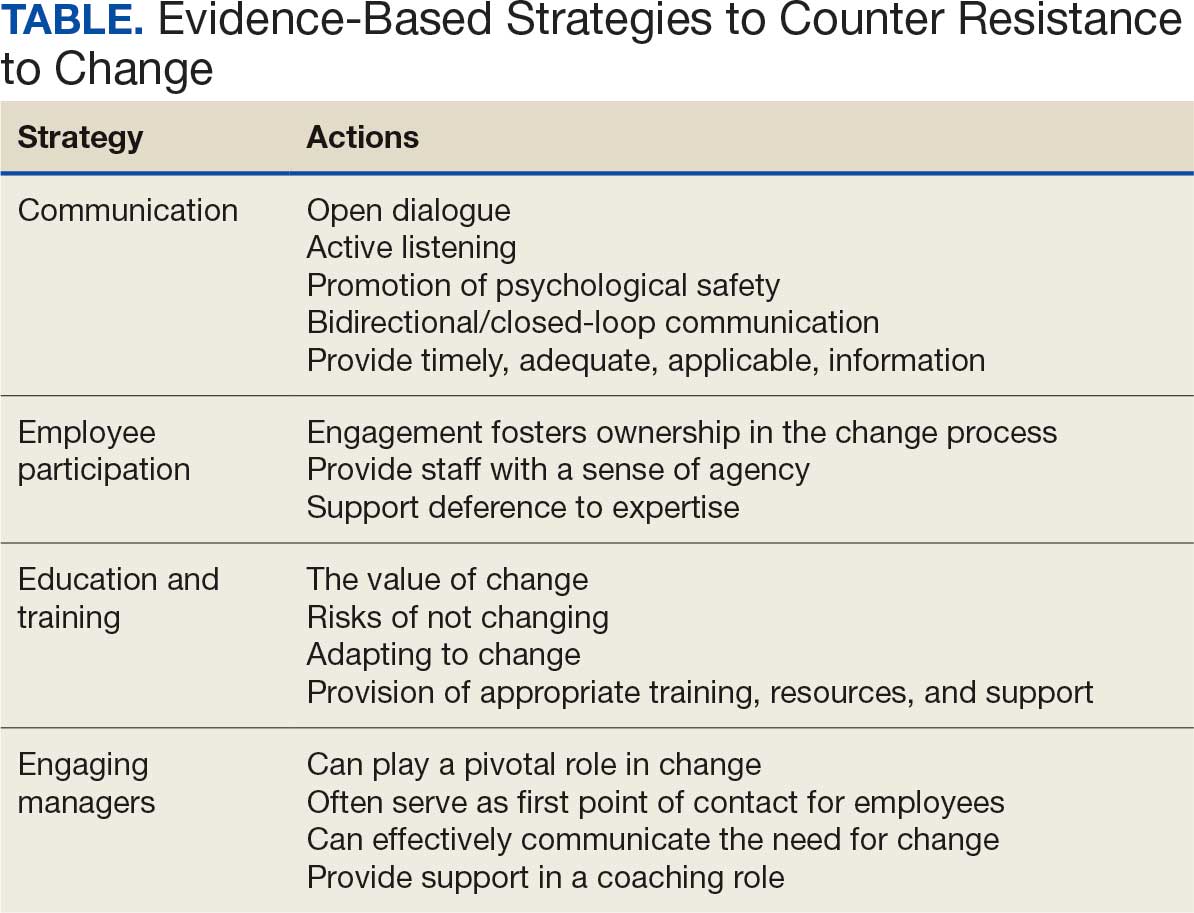

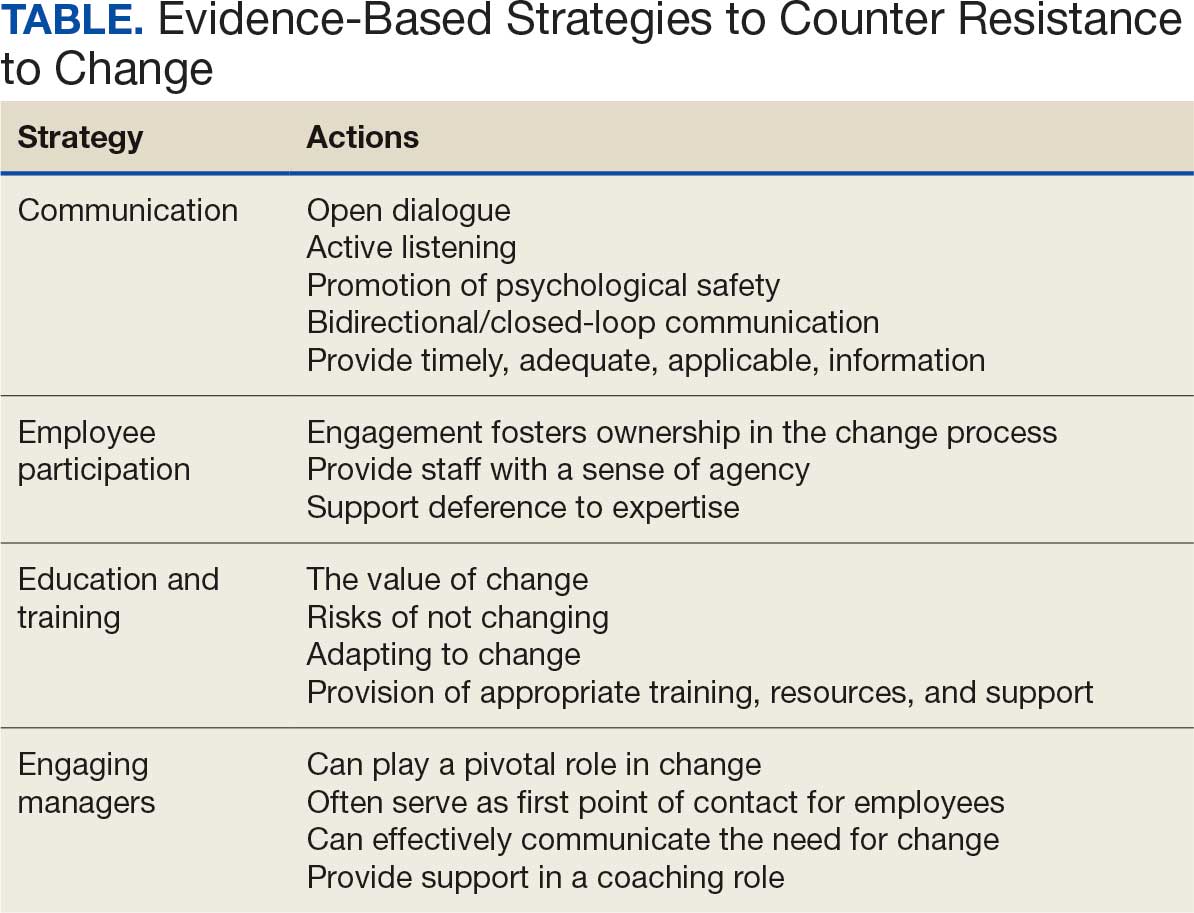

Managing Resistance to Change Along the Journey to High Reliability

Managing Resistance to Change Along the Journey to High Reliability

To improve safety performance, many health care organizations have embarked on the journey to becoming high reliability organizations (HROs). HROs operate in complex, high-risk, constantly changing environments and avoid catastrophic events despite the inherent risks.1 HROs maintain high levels of safety and reliability by adhering to core principles, foundational practices, rigorous processes, a strong organizational culture, and continuous learning and process improvement.1-3

Becoming an HRO requires understanding what makes systems safer for patients and staff at all levels by taking ownership of 5 principles: (1) sensitivity to operations (increased awareness of the current status of systems); (2) reluctance to simplify (avoiding oversimplification of the cause[s] of problems); (3) preoccupation with failure (anticipating risks that might be symptomatic of a larger problem); (4) deference to expertise (relying on the most qualified individuals to make decisions); and (5) commitment to resilience (planning for potential failure and being prepared to respond).1,2,4 In addition to these, the Veterans Health Administration has identified 3 pillars of HROs: leadership commitment (safety and reliability are central to leadership vision, decision-making, and action-oriented behaviors), safety culture (across the organization, safety values are key to preventing harm and learning from mistakes), and continuous process improvement (promoting constant learning and improvement with evidence-based tools and methodologies).5