User login

Progressive Dystrophy of the Fingernails and Toenails

Progressive Dystrophy of the Fingernails and Toenails

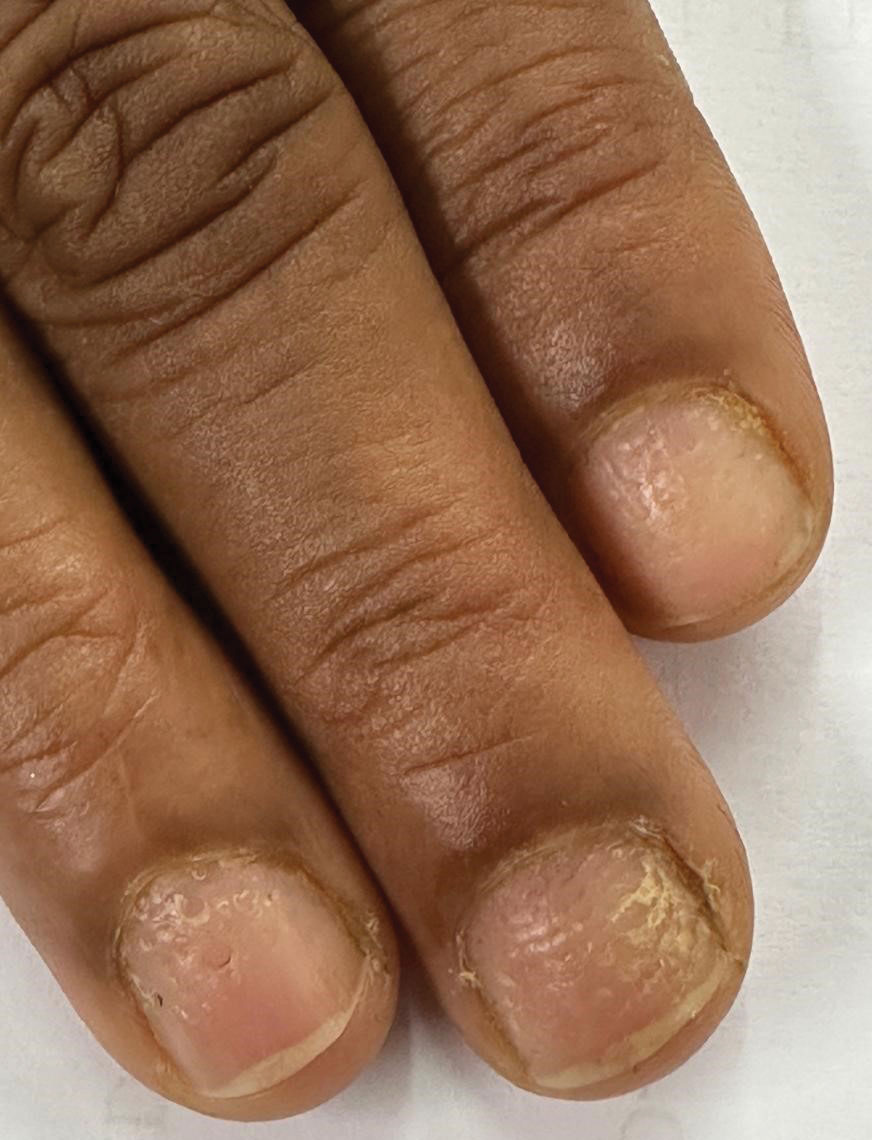

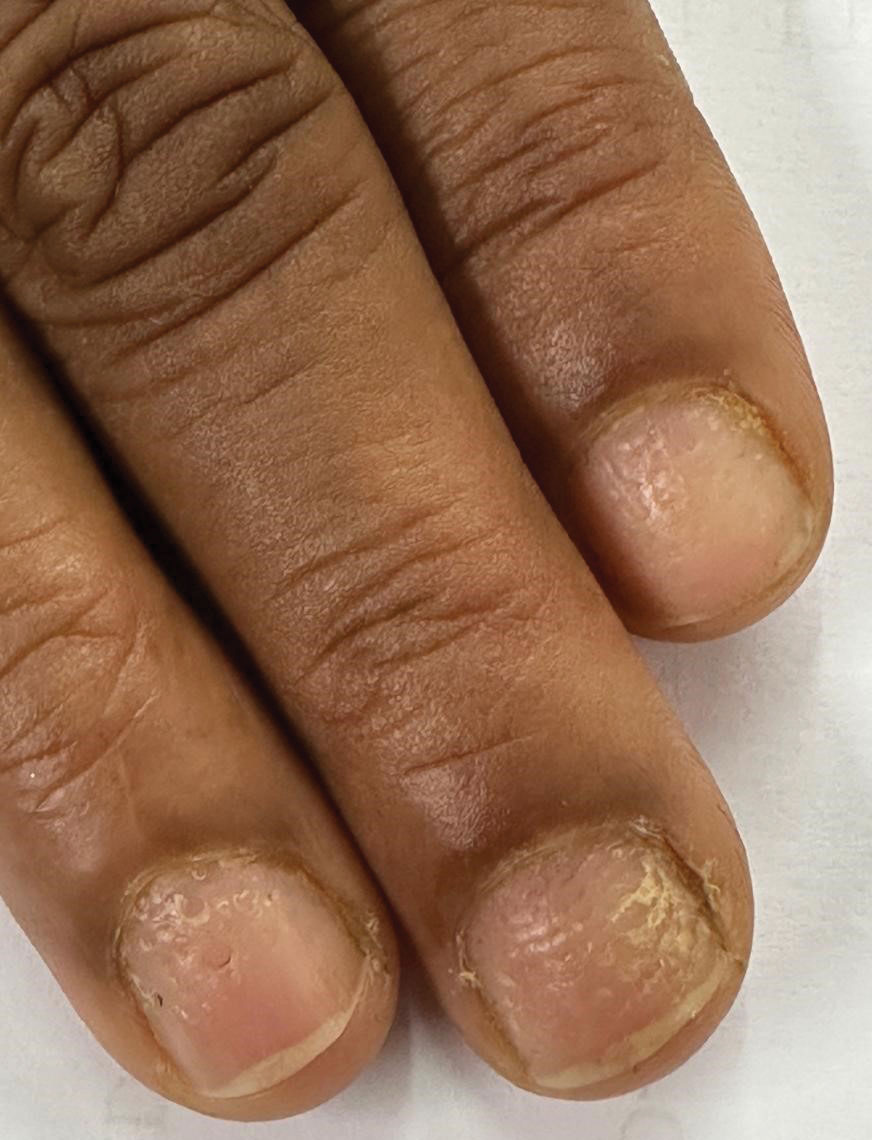

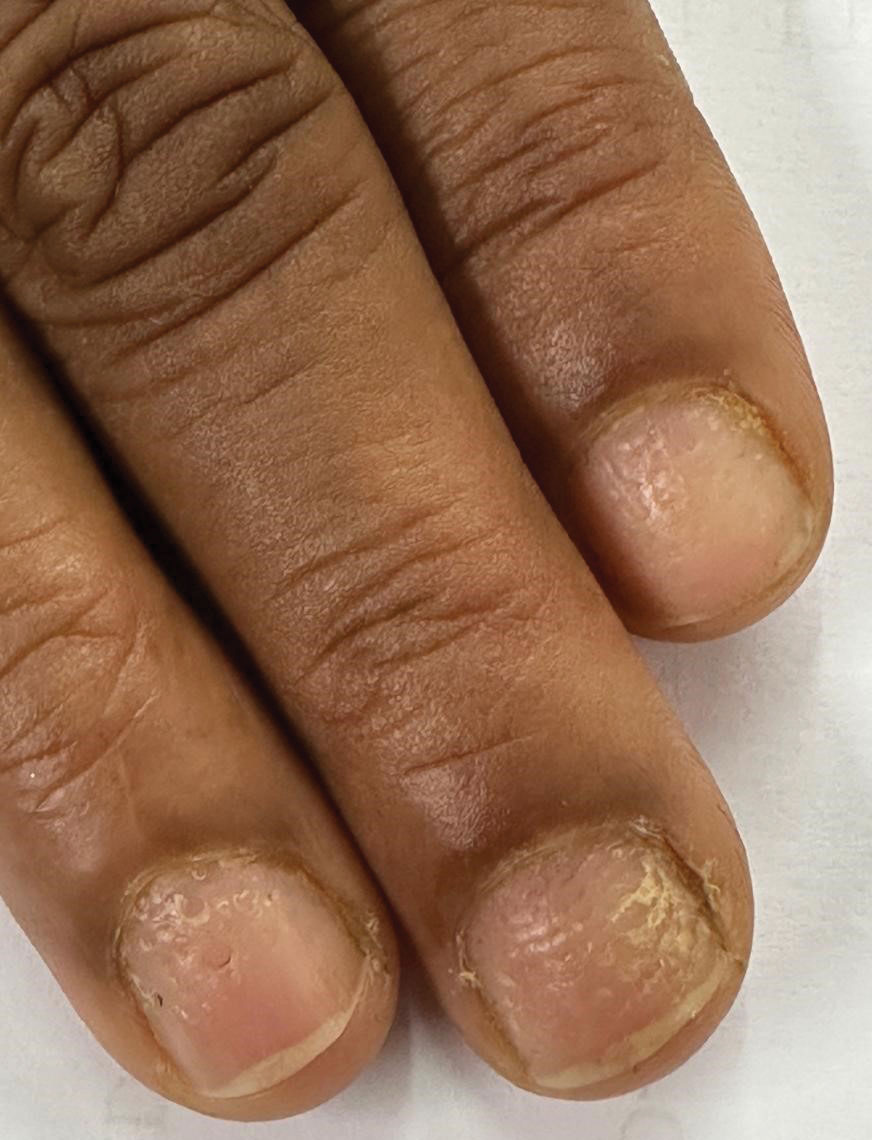

THE DIAGNOSIS: Nail Lichen Planus

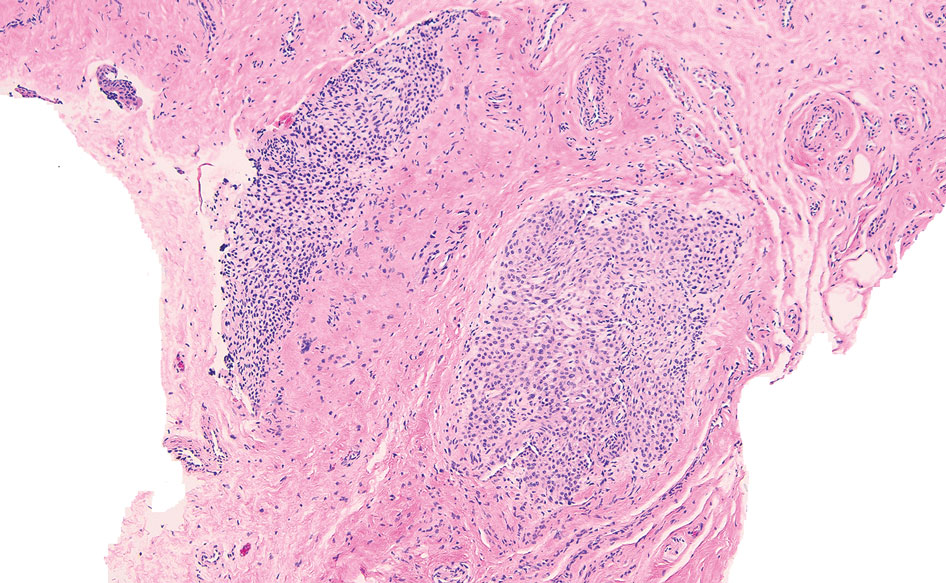

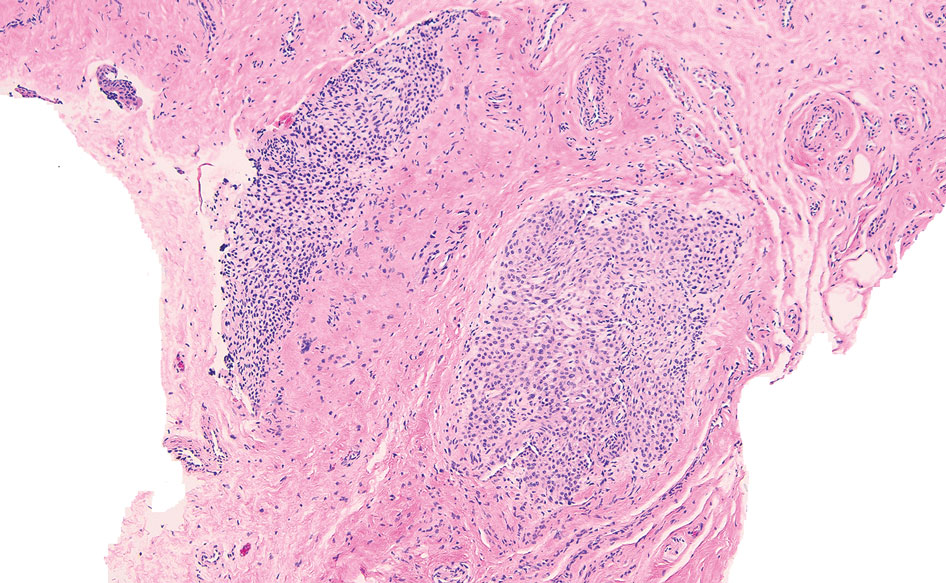

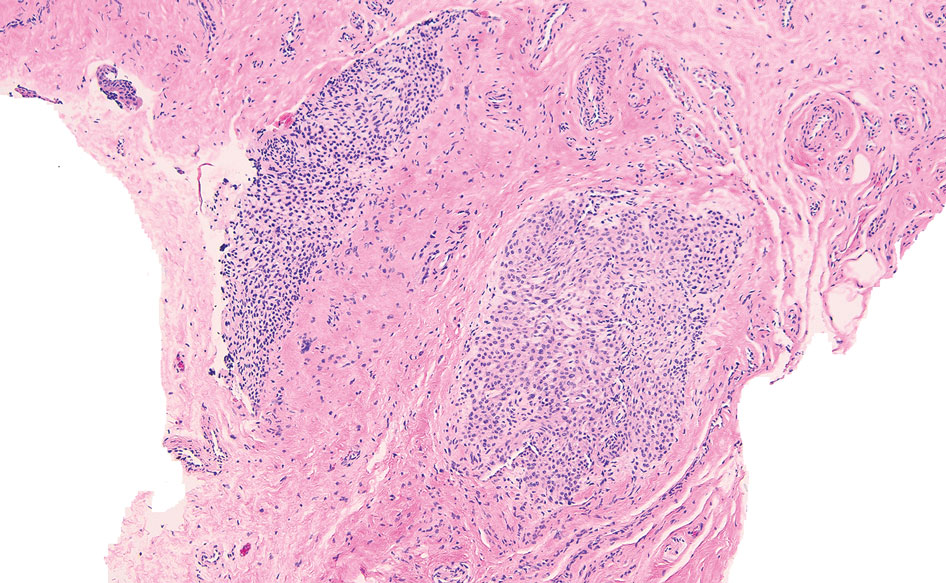

The biopsy results showed features of hypergranulosis of the matricial epithelium, irregular acanthosis, apoptotic keratinocytes along the basal layer, and a lichenoid infiltrate consistent with nail lichen planus. The patient was started on topical clobetasol propionate 0.05% applied once daily under overnight occlusion. Additionally, intramatricial triamcinolone acetonide (2.5 mg/mL; 0.1 mL per injection) was administered into the affected nail matrix at 4-week intervals for a total of 2 sessions. At the 2-month follow-up visit, the patient reported improvement in longitudinal ridging; however, he subsequently was lost to follow-up.

Nail lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory disorder that occurs in 10% to 15% of patients with lichen planus worldwide and is more common in adults than children.1 It can manifest independently or concurrently with cutaneous and/or oral mucosal involvement. The fingernails are more commonly affected than the toenails.2 The clinical features of nail lichen planus can be classified based on involvement of the nail matrix (longitudinal ridging, red lunula, thinning of the nail plate, koilonychia, trachyonychia, pterygium, and anonychia) or nail bed (onycholysis, subungual hyperkeratosis, and splinter hemorrhages).1

In our patient, who presented with chronic progressive nail dystrophy affecting all 20 nails, onychomycosis, nail psoriasis, onychotillomania, and idiopathic trachyonychia were included in the differential.1

Onychomycosis manifests as white or yellow-brown discoloration of the nail, onycholysis, subungual hyperkeratosis, and thickening of the nail plate. Diagnosis is confirmed by the presence of septate hyphae (dermatophytes) or budding yeast cells (Candida species) on a potassium hydroxide mount. Other diagnostic modalities include dermoscopy, fungal culture, and histopathology of nail clippings, with demonstration of fungal elements identified on periodic acid-Schiff staining (eFigure 1).3

Nail psoriasis characteristically manifests as deep irregular pitting of the nails. Other features favoring psoriasis include involvement of the nail matrix manifesting as leukonychia, red lunula, and crumbling, as well as involvement of the nail bed manifesting as onycholysis, subungual hyperkeratosis, salmon patches/oil spots, and splinter hemorrhages (eFigure 2).4 Diagnosis primarily is clinical, supported by histopathology when uncertainty exists.

Onychotillomania is a behavioral disorder characterized by an irresistible urge or impulse in patients to either pick or pull at their fingernails and/or toenails. Clinicopathologic features of the involved nails are nonspecific and atypical, with possible involvement of periungual and digital skin. Diagnosis of onychotillomania is challenging.5 Dermoscopic features including anonychia with multiple obliquely arranged nail bed hemorrhages, gray pigmentation of the nail bed, and wavy lines, has been proposed to aid the diagnosis of onychotillomania.6

Idiopathic trachyonychia is isolated nail involvement characterized by rough, ridged, and thin nails affecting multiple or all of the fingernails and toenails without an underlying systemic or dermatologic condition (eFigure 3). The terms trachyonychia and 20-nail dystrophy have been used interchangeably in the literature; however, trachyonychia does not always involve all 20 nails. Other conditions causing widespread dystrophy of all 20 nails cannot be diagnosed as 20-nail dystrophy or trachyonychia without the distinct morphologic features of thin brittle nails with pronounced longitudinal ridging.7

Prompt diagnosis and early intervention in nail lichen planus is crucial due to the potential for irreversible scarring. First-line treatment options include intramatricial and intramuscular triamcinolone acetonide for 3 to 6 months.4 Second-line therapies include oral retinoids such as acitretin and alitretinoin and immunosuppressive agents such as azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, and cyclosporine. Other reported treatment options include clobetasol propionate, tacrolimus, dapsone, griseofulvin, etanercept, hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, and UV therapy.4

- Gupta MK, Lipner SR. Review of nail lichen planus: epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Dermatol Clin. 2021;39:221-230. doi:10.1016/j.det.2020.12.002

- Iorizzo M, Tosti A, Starace M, et al. Isolated nail lichen planus: an expert consensus on treatment of the classical form. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1717-1723. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.02.056

- Leung AKC, Lam JM, Leong KF, et al. Onychomycosis: an updated review. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2020;14:32-45. doi:10.2174/1872213X13666191026090713

- Hwang JK, Grover C, Iorizzo M, et al. Nail psoriasis and nail lichen planus: updates on diagnosis and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:585-596. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.11.024

- Sidiropoulou P, Sgouros D, Theodoropoulos K, et al. Onychotillomania: a chameleon-like disorder: case report and review of literature. Skin Appendage Disord. 2019;5:104-107. doi:10.1159/000489941

- Maddy AJ, Tosti A. Dermoscopic features of onychotillomania: a study of 36 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:702-705. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2018.04.015

- Haber JS, Chairatchaneeboon M, Rubin AI. Trachyonychia: review and update on clinical aspects, histology, and therapy. Skin Appendage Disord. 2017;2:109-115. doi:10.1159/000449063

THE DIAGNOSIS: Nail Lichen Planus

The biopsy results showed features of hypergranulosis of the matricial epithelium, irregular acanthosis, apoptotic keratinocytes along the basal layer, and a lichenoid infiltrate consistent with nail lichen planus. The patient was started on topical clobetasol propionate 0.05% applied once daily under overnight occlusion. Additionally, intramatricial triamcinolone acetonide (2.5 mg/mL; 0.1 mL per injection) was administered into the affected nail matrix at 4-week intervals for a total of 2 sessions. At the 2-month follow-up visit, the patient reported improvement in longitudinal ridging; however, he subsequently was lost to follow-up.

Nail lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory disorder that occurs in 10% to 15% of patients with lichen planus worldwide and is more common in adults than children.1 It can manifest independently or concurrently with cutaneous and/or oral mucosal involvement. The fingernails are more commonly affected than the toenails.2 The clinical features of nail lichen planus can be classified based on involvement of the nail matrix (longitudinal ridging, red lunula, thinning of the nail plate, koilonychia, trachyonychia, pterygium, and anonychia) or nail bed (onycholysis, subungual hyperkeratosis, and splinter hemorrhages).1

In our patient, who presented with chronic progressive nail dystrophy affecting all 20 nails, onychomycosis, nail psoriasis, onychotillomania, and idiopathic trachyonychia were included in the differential.1

Onychomycosis manifests as white or yellow-brown discoloration of the nail, onycholysis, subungual hyperkeratosis, and thickening of the nail plate. Diagnosis is confirmed by the presence of septate hyphae (dermatophytes) or budding yeast cells (Candida species) on a potassium hydroxide mount. Other diagnostic modalities include dermoscopy, fungal culture, and histopathology of nail clippings, with demonstration of fungal elements identified on periodic acid-Schiff staining (eFigure 1).3

Nail psoriasis characteristically manifests as deep irregular pitting of the nails. Other features favoring psoriasis include involvement of the nail matrix manifesting as leukonychia, red lunula, and crumbling, as well as involvement of the nail bed manifesting as onycholysis, subungual hyperkeratosis, salmon patches/oil spots, and splinter hemorrhages (eFigure 2).4 Diagnosis primarily is clinical, supported by histopathology when uncertainty exists.

Onychotillomania is a behavioral disorder characterized by an irresistible urge or impulse in patients to either pick or pull at their fingernails and/or toenails. Clinicopathologic features of the involved nails are nonspecific and atypical, with possible involvement of periungual and digital skin. Diagnosis of onychotillomania is challenging.5 Dermoscopic features including anonychia with multiple obliquely arranged nail bed hemorrhages, gray pigmentation of the nail bed, and wavy lines, has been proposed to aid the diagnosis of onychotillomania.6

Idiopathic trachyonychia is isolated nail involvement characterized by rough, ridged, and thin nails affecting multiple or all of the fingernails and toenails without an underlying systemic or dermatologic condition (eFigure 3). The terms trachyonychia and 20-nail dystrophy have been used interchangeably in the literature; however, trachyonychia does not always involve all 20 nails. Other conditions causing widespread dystrophy of all 20 nails cannot be diagnosed as 20-nail dystrophy or trachyonychia without the distinct morphologic features of thin brittle nails with pronounced longitudinal ridging.7

Prompt diagnosis and early intervention in nail lichen planus is crucial due to the potential for irreversible scarring. First-line treatment options include intramatricial and intramuscular triamcinolone acetonide for 3 to 6 months.4 Second-line therapies include oral retinoids such as acitretin and alitretinoin and immunosuppressive agents such as azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, and cyclosporine. Other reported treatment options include clobetasol propionate, tacrolimus, dapsone, griseofulvin, etanercept, hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, and UV therapy.4

THE DIAGNOSIS: Nail Lichen Planus

The biopsy results showed features of hypergranulosis of the matricial epithelium, irregular acanthosis, apoptotic keratinocytes along the basal layer, and a lichenoid infiltrate consistent with nail lichen planus. The patient was started on topical clobetasol propionate 0.05% applied once daily under overnight occlusion. Additionally, intramatricial triamcinolone acetonide (2.5 mg/mL; 0.1 mL per injection) was administered into the affected nail matrix at 4-week intervals for a total of 2 sessions. At the 2-month follow-up visit, the patient reported improvement in longitudinal ridging; however, he subsequently was lost to follow-up.

Nail lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory disorder that occurs in 10% to 15% of patients with lichen planus worldwide and is more common in adults than children.1 It can manifest independently or concurrently with cutaneous and/or oral mucosal involvement. The fingernails are more commonly affected than the toenails.2 The clinical features of nail lichen planus can be classified based on involvement of the nail matrix (longitudinal ridging, red lunula, thinning of the nail plate, koilonychia, trachyonychia, pterygium, and anonychia) or nail bed (onycholysis, subungual hyperkeratosis, and splinter hemorrhages).1

In our patient, who presented with chronic progressive nail dystrophy affecting all 20 nails, onychomycosis, nail psoriasis, onychotillomania, and idiopathic trachyonychia were included in the differential.1

Onychomycosis manifests as white or yellow-brown discoloration of the nail, onycholysis, subungual hyperkeratosis, and thickening of the nail plate. Diagnosis is confirmed by the presence of septate hyphae (dermatophytes) or budding yeast cells (Candida species) on a potassium hydroxide mount. Other diagnostic modalities include dermoscopy, fungal culture, and histopathology of nail clippings, with demonstration of fungal elements identified on periodic acid-Schiff staining (eFigure 1).3

Nail psoriasis characteristically manifests as deep irregular pitting of the nails. Other features favoring psoriasis include involvement of the nail matrix manifesting as leukonychia, red lunula, and crumbling, as well as involvement of the nail bed manifesting as onycholysis, subungual hyperkeratosis, salmon patches/oil spots, and splinter hemorrhages (eFigure 2).4 Diagnosis primarily is clinical, supported by histopathology when uncertainty exists.

Onychotillomania is a behavioral disorder characterized by an irresistible urge or impulse in patients to either pick or pull at their fingernails and/or toenails. Clinicopathologic features of the involved nails are nonspecific and atypical, with possible involvement of periungual and digital skin. Diagnosis of onychotillomania is challenging.5 Dermoscopic features including anonychia with multiple obliquely arranged nail bed hemorrhages, gray pigmentation of the nail bed, and wavy lines, has been proposed to aid the diagnosis of onychotillomania.6

Idiopathic trachyonychia is isolated nail involvement characterized by rough, ridged, and thin nails affecting multiple or all of the fingernails and toenails without an underlying systemic or dermatologic condition (eFigure 3). The terms trachyonychia and 20-nail dystrophy have been used interchangeably in the literature; however, trachyonychia does not always involve all 20 nails. Other conditions causing widespread dystrophy of all 20 nails cannot be diagnosed as 20-nail dystrophy or trachyonychia without the distinct morphologic features of thin brittle nails with pronounced longitudinal ridging.7

Prompt diagnosis and early intervention in nail lichen planus is crucial due to the potential for irreversible scarring. First-line treatment options include intramatricial and intramuscular triamcinolone acetonide for 3 to 6 months.4 Second-line therapies include oral retinoids such as acitretin and alitretinoin and immunosuppressive agents such as azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, and cyclosporine. Other reported treatment options include clobetasol propionate, tacrolimus, dapsone, griseofulvin, etanercept, hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, and UV therapy.4

- Gupta MK, Lipner SR. Review of nail lichen planus: epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Dermatol Clin. 2021;39:221-230. doi:10.1016/j.det.2020.12.002

- Iorizzo M, Tosti A, Starace M, et al. Isolated nail lichen planus: an expert consensus on treatment of the classical form. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1717-1723. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.02.056

- Leung AKC, Lam JM, Leong KF, et al. Onychomycosis: an updated review. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2020;14:32-45. doi:10.2174/1872213X13666191026090713

- Hwang JK, Grover C, Iorizzo M, et al. Nail psoriasis and nail lichen planus: updates on diagnosis and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:585-596. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.11.024

- Sidiropoulou P, Sgouros D, Theodoropoulos K, et al. Onychotillomania: a chameleon-like disorder: case report and review of literature. Skin Appendage Disord. 2019;5:104-107. doi:10.1159/000489941

- Maddy AJ, Tosti A. Dermoscopic features of onychotillomania: a study of 36 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:702-705. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2018.04.015

- Haber JS, Chairatchaneeboon M, Rubin AI. Trachyonychia: review and update on clinical aspects, histology, and therapy. Skin Appendage Disord. 2017;2:109-115. doi:10.1159/000449063

- Gupta MK, Lipner SR. Review of nail lichen planus: epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Dermatol Clin. 2021;39:221-230. doi:10.1016/j.det.2020.12.002

- Iorizzo M, Tosti A, Starace M, et al. Isolated nail lichen planus: an expert consensus on treatment of the classical form. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1717-1723. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.02.056

- Leung AKC, Lam JM, Leong KF, et al. Onychomycosis: an updated review. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2020;14:32-45. doi:10.2174/1872213X13666191026090713

- Hwang JK, Grover C, Iorizzo M, et al. Nail psoriasis and nail lichen planus: updates on diagnosis and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:585-596. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.11.024

- Sidiropoulou P, Sgouros D, Theodoropoulos K, et al. Onychotillomania: a chameleon-like disorder: case report and review of literature. Skin Appendage Disord. 2019;5:104-107. doi:10.1159/000489941

- Maddy AJ, Tosti A. Dermoscopic features of onychotillomania: a study of 36 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:702-705. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2018.04.015

- Haber JS, Chairatchaneeboon M, Rubin AI. Trachyonychia: review and update on clinical aspects, histology, and therapy. Skin Appendage Disord. 2017;2:109-115. doi:10.1159/000449063

Progressive Dystrophy of the Fingernails and Toenails

Progressive Dystrophy of the Fingernails and Toenails

A 35-year-old man presented to the dermatology department with gradually progressive dystrophy of the fingernails and toenails of 20 years’ duration. The patient reported no history of other dermatologic conditions. Physical examination revealed longitudinal ridging of all 20 nails and discoloration of the nail plates, as well as a few nails showing pterygium and anonychia; the skin and mucosal surfaces were otherwise normal, and nail plate thinning was not observed. A potassium hydroxide mount was negative. A biopsy of the nail matrix on the left thumbnail was performed.

Alopecia and Pruritic Rash on the Forehead and Scalp

Alopecia and Pruritic Rash on the Forehead and Scalp

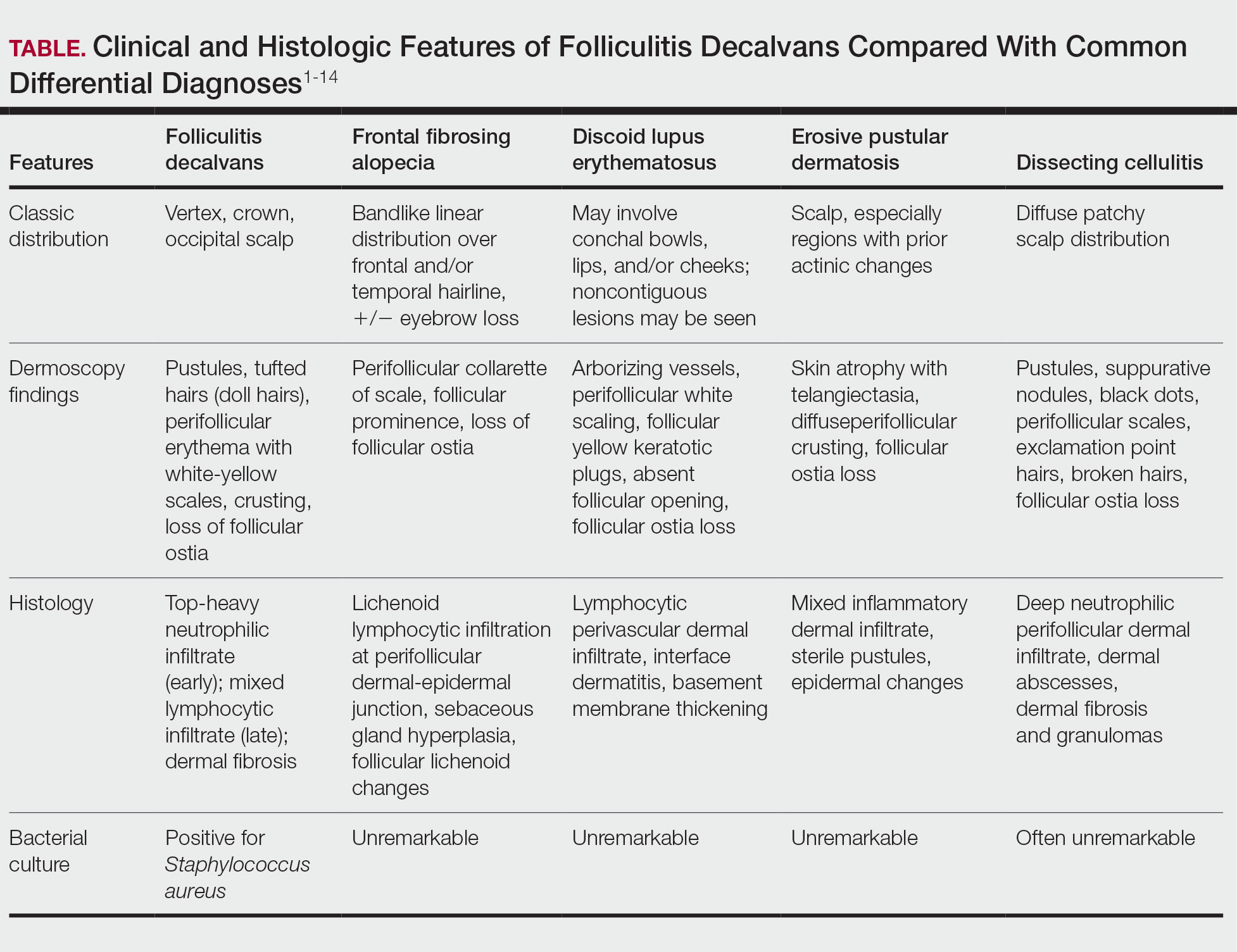

THE DIAGNOSIS: Folliculitis Decalvans

Biopsy results revealed a brisk perifollicular and intrafollicular mixed inflammatory infiltrate comprising lymphocytes, neutrophils, and plasma cells filling the upper dermis and encircling dilated hair follicles. Elastic stain (Verhoeff-van Gieson) demonstrated loss of elastic fibers in areas of scarring. Periodic acid–Schiff with diastase staining was negative for fungal elements, while Gram staining revealed colonies of bacterial cocci in the stratum corneum and within the hair follicles. Immunofluorescence was unremarkable, and culture revealed methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus, leading to a diagnosis of folliculitis decalvans (FD). The patient was treated with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and received intralesional triamcinolone 2.5 mg/mL (total volume, 2 mL) every 6 weeks with considerable improvement in pustules, erythema, and scaling (Figure). While not yet in complete remission, our patient demonstrated short regrowing hairs in areas of incomplete scarring and focal remaining perifollicular erythema and scale along the midline frontal scalp 5 months after initial presentation.

Folliculitis decalvans is an uncommon subtype of cicatricial alopecia that may mimic other forms of alopecia. Cicatricial alopecia often is difficult to diagnose due to its overlapping clinical characteristics, but early diagnosis is essential for appropriate management and prevention of further permanent hair loss. Traditionally classified as a primary neutrophilic cicatricial alopecia, lymphocyte-predominant variants of FD now are recognized.1

Patients with FD typically present with patchy scarring alopecia at the vertex scalp that gradually expands and may demonstrate secondary features of follicular tufting and pustules.1-3 While the epidemiology of FD is poorly characterized, Vañó-Galván et al4 reported that FD accounted for 2.8% of all alopecia cases and 10.5% of cicatricial alopecia cases in a multicenter study of 2835 patients. The pathophysiology of FD still is under investigation but is thought to result from a dysregulated immune response to a chronic bacterial infection (eg, S aureus), with resulting neutrophilpredominant inflammation in early stages.1-3 Vañó-Galván et al4 reported that, among 35 patients with FD cultured for bacteria, 74% (26/35) returned positive results, 96% (25/26) of which grew S aureus.5

A systematic review of 20 studies that included 263 patients found rifampin and clindamycin to be the most common treatments for FD; however, there is insufficient evidence to determine if this treatment is the most effective.6 In our patient, clindamycin was avoided due to its propensity to negatively alter the gut microbiome long term.7 Other therapies such as oral tetracyclines, high-potency topical steroids, and intralesional triamcinolone also can be used to achieve disease remission.5,6 Other treatments such as isotretinoin, red-light photodynamic therapy, tacrolimus, and external beam radiation have been reported in the literature but vary in efficacy.6 Our patient improved on a regimen of topical benzoyl peroxide wash, oral doxycycline, and intralesional triamcinolone.

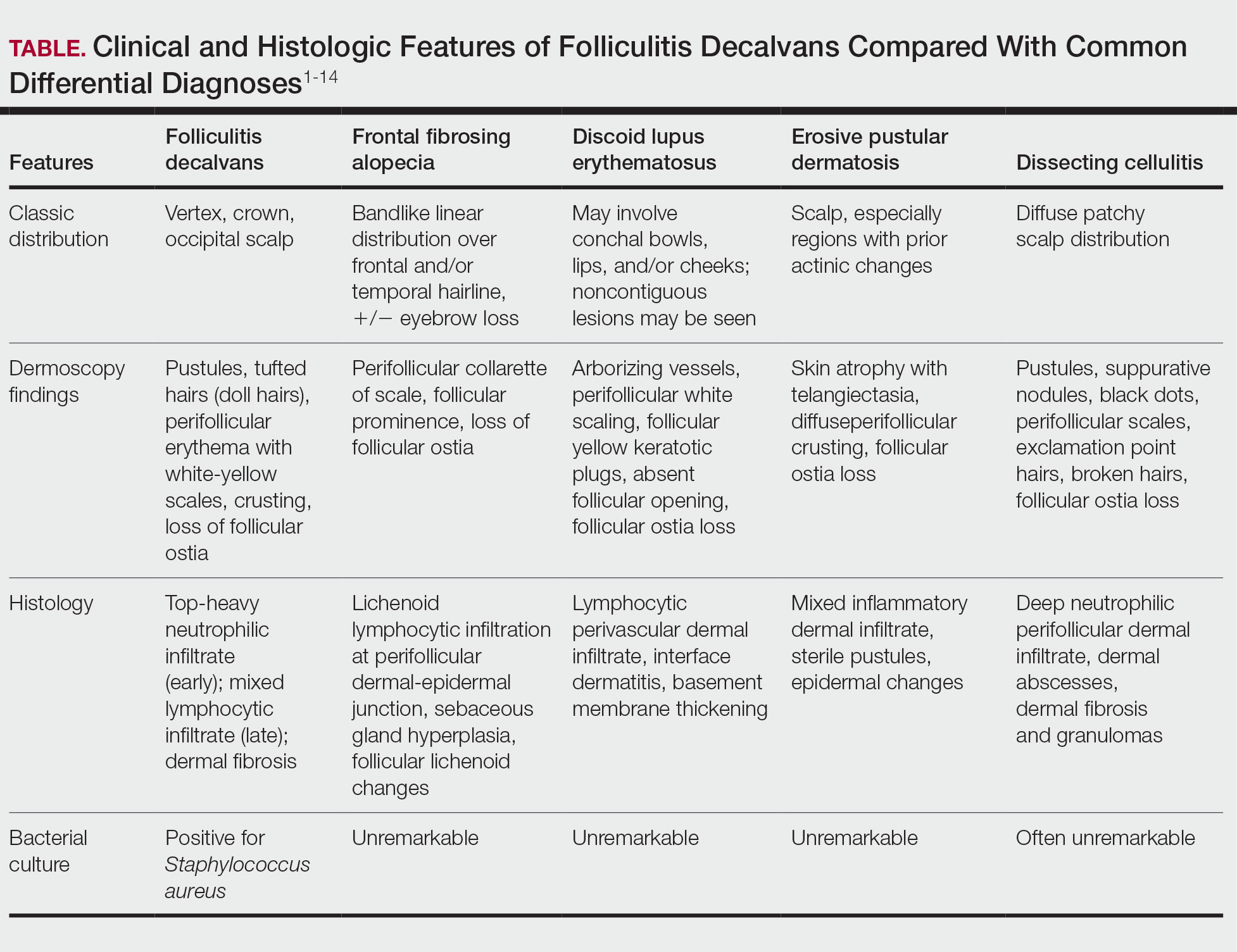

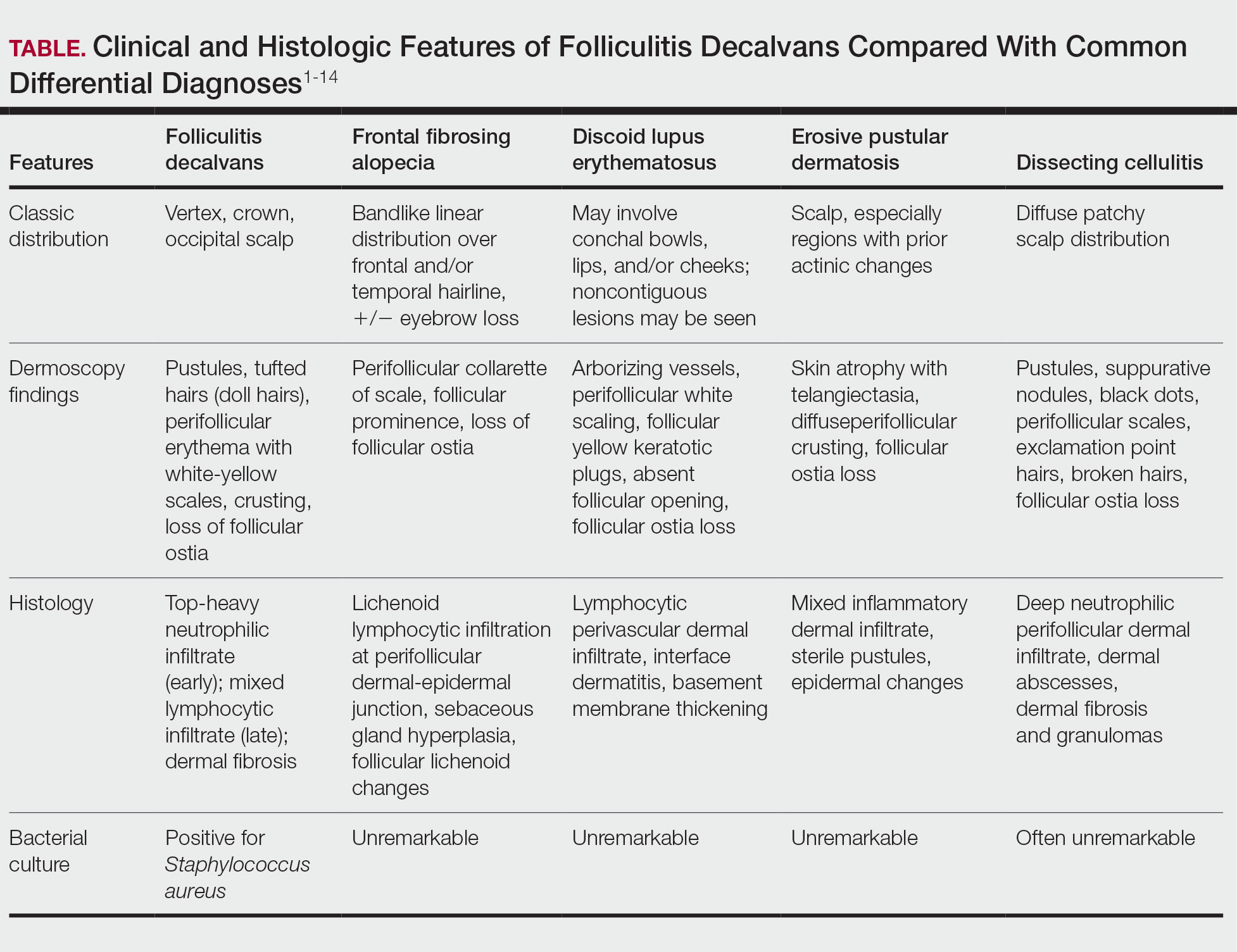

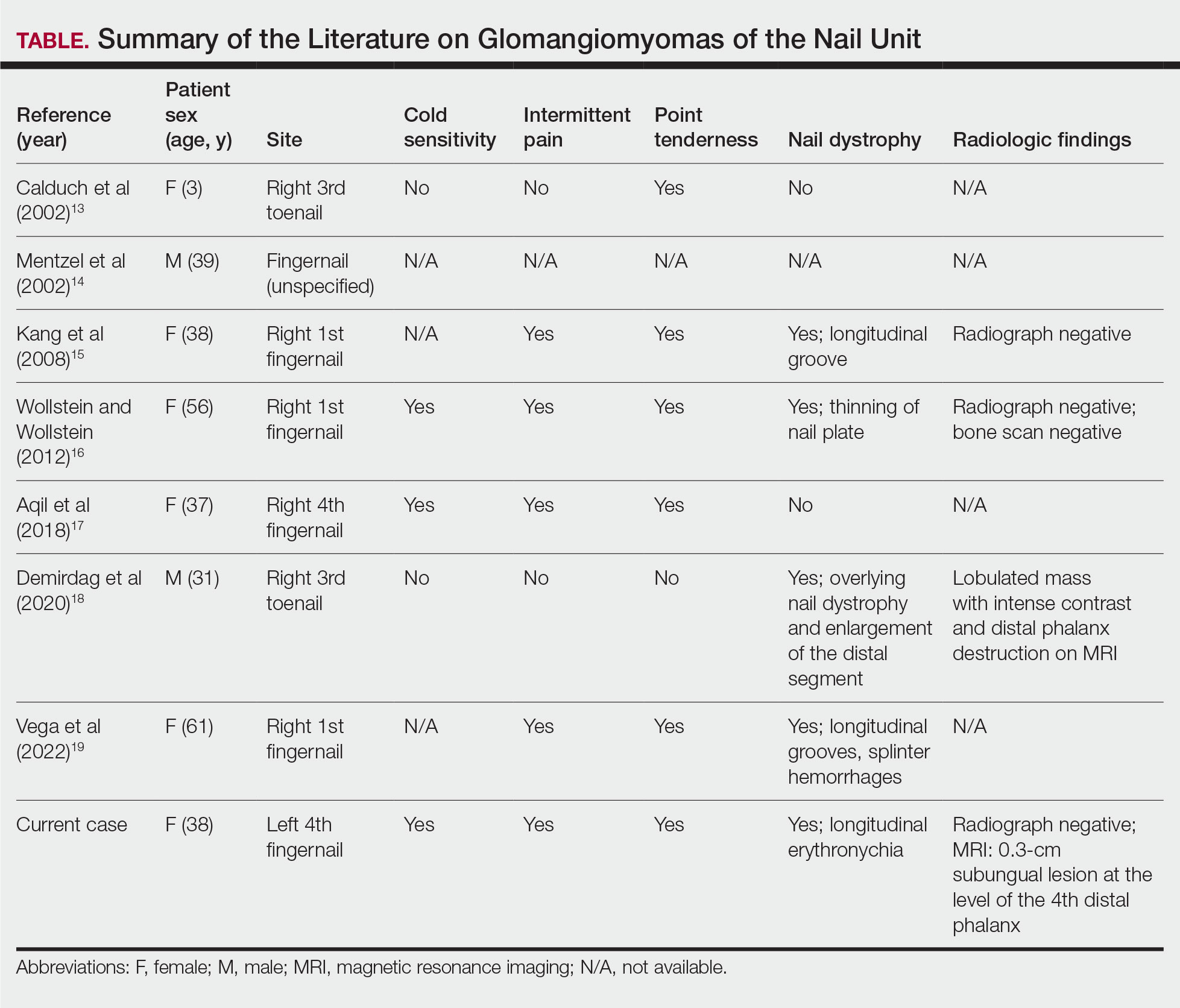

Notably, FD may share clinical features with other causes of cicatricial alopecia. In our patient, FD mimicked other entities including discoid lupus erythematosus, frontal fibrosing alopecia, dissecting cellulitis, and erosive pustular dermatosis (Table).1-14 Discoid lupus erythematosus manifests as round hypopigmented and hyperpigmented plaques with associated atrophy, perifollicular erythema, and follicular plugging. Frontal fibrosing alopecia is a primary lymphocytic scarring alopecia that manifests in a bandlike linear distribution over the frontal scalp and may involve the temporal scalp, posterior hairline, and/or eyebrows. Isolated hairs (known as lonely hairs) often are seen. Dissecting cellulitis is characterized by boggy nodules associated with alopecia on the scalp without notable epidermal change, although pustules and sinus tracts may develop.9 Erosive pustular dermatosis is a diagnosis of exclusion but often is seen in older adults with chronic sun damage and clinically manifests with eroded plaques with adherent crusts.10

While our patient presented with several overlapping clinical features, including progressive hair loss along the frontal scalp in a bandlike pattern suspicious for frontal fibrosing alopecia as well as atrophic depigmented plaques with adherent peripheral scaling suspicious for discoid lupus erythematosus, the presence of pustules was an important clue. The biopsy demonstrating a mixed infiltrate inclusive of neutrophils confirmed the diagnosis of FD.

- Olsen EA, Bergfeld WF, Cotsarelis G, et al. Summary of North American Hair Research Society (NAHRS)-sponsored Workshop on Cicatricial Alopecia, Duke University Medical Center, February 10 and 11, 2001. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:103-110. doi:10.1067/mjd.2003.68

- Filbrandt R, Rufaut N, Jones L. Primary cicatricial alopecia: diagnosis and treatment. CMAJ. 2013;185:1579-1585. doi:10.1503/cmaj.111570

- Otberg N, Kang H, Alzolibani AA, et al. Folliculitis decalvans. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21:238-244. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8019.2008.00204.x

- Vañó-Galván S, Saceda-Corralo D, Blume-Peytavi U, et al. Frequency of the types of alopecia at twenty-two specialist hair clinics: a multicenter study. Skin Appendage Disord. 2019;5:309-315. doi:10.1159/000496708

- Vañó-Galván S, Molina-Ruiz AM, Fernández-Crehuet P, et al. Folliculitis decalvans: a multicentre review of 82 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1750-1757. doi:10.1111/jdv.12993

- Rambhia PH, Conic RRZ, Murad A, et al. Updates in therapeutics for folliculitis decalvans: a systematic review with evidence-based analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:794-801. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.07.050

- Zimmermann P, Curtis N. The effect of antibiotics on the composition of the intestinal microbiota - a systematic review. J Infect. 2019;79:471-489. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2019.10.008

- Kanti V, Röwert-Huber J, Vogt A, et al. Cicatricial alopecia. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:435-461. doi:10.1111/ddg.13498

- Melo DF, Slaibi EB, Siqueira TMFM, et al. Trichoscopy findings in dissecting cellulitis. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:608-611. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2019.09.006

- Anzai A, Pirmez R, Vincenzi C, et al. Trichoscopy findings of frontal fibrosing alopecia on the eyebrows: a study of 151 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1130-1134. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.12.023

- Starace M, Loi C, Bruni F, et al. Erosive pustular dermatosis of the scalp: clinical, trichoscopic, and histopathologic features of 20 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:1109-1114. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.12.016

- Rongioletti F, Christana K. Cicatricial (scarring) alopecias: an overview of pathogenesis, classification, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:247-260. doi:10.2165/11596960-000000000-00000

- Badaoui A, Reygagne P, Cavelier-Balloy B, et al. Dissecting cellulitis of the scalp: a retrospective study of 51 patients and review of literature. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:421-423. doi:10.1111/bjd.13999

- Michelerio A, Vassallo C, Fiandrino G, et al. Erosive pustular dermatosis of the scalp: a clinicopathologic study of fifty cases. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2021;8:450-462. doi:10.3390/dermatopathology8040048

THE DIAGNOSIS: Folliculitis Decalvans

Biopsy results revealed a brisk perifollicular and intrafollicular mixed inflammatory infiltrate comprising lymphocytes, neutrophils, and plasma cells filling the upper dermis and encircling dilated hair follicles. Elastic stain (Verhoeff-van Gieson) demonstrated loss of elastic fibers in areas of scarring. Periodic acid–Schiff with diastase staining was negative for fungal elements, while Gram staining revealed colonies of bacterial cocci in the stratum corneum and within the hair follicles. Immunofluorescence was unremarkable, and culture revealed methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus, leading to a diagnosis of folliculitis decalvans (FD). The patient was treated with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and received intralesional triamcinolone 2.5 mg/mL (total volume, 2 mL) every 6 weeks with considerable improvement in pustules, erythema, and scaling (Figure). While not yet in complete remission, our patient demonstrated short regrowing hairs in areas of incomplete scarring and focal remaining perifollicular erythema and scale along the midline frontal scalp 5 months after initial presentation.

Folliculitis decalvans is an uncommon subtype of cicatricial alopecia that may mimic other forms of alopecia. Cicatricial alopecia often is difficult to diagnose due to its overlapping clinical characteristics, but early diagnosis is essential for appropriate management and prevention of further permanent hair loss. Traditionally classified as a primary neutrophilic cicatricial alopecia, lymphocyte-predominant variants of FD now are recognized.1

Patients with FD typically present with patchy scarring alopecia at the vertex scalp that gradually expands and may demonstrate secondary features of follicular tufting and pustules.1-3 While the epidemiology of FD is poorly characterized, Vañó-Galván et al4 reported that FD accounted for 2.8% of all alopecia cases and 10.5% of cicatricial alopecia cases in a multicenter study of 2835 patients. The pathophysiology of FD still is under investigation but is thought to result from a dysregulated immune response to a chronic bacterial infection (eg, S aureus), with resulting neutrophilpredominant inflammation in early stages.1-3 Vañó-Galván et al4 reported that, among 35 patients with FD cultured for bacteria, 74% (26/35) returned positive results, 96% (25/26) of which grew S aureus.5

A systematic review of 20 studies that included 263 patients found rifampin and clindamycin to be the most common treatments for FD; however, there is insufficient evidence to determine if this treatment is the most effective.6 In our patient, clindamycin was avoided due to its propensity to negatively alter the gut microbiome long term.7 Other therapies such as oral tetracyclines, high-potency topical steroids, and intralesional triamcinolone also can be used to achieve disease remission.5,6 Other treatments such as isotretinoin, red-light photodynamic therapy, tacrolimus, and external beam radiation have been reported in the literature but vary in efficacy.6 Our patient improved on a regimen of topical benzoyl peroxide wash, oral doxycycline, and intralesional triamcinolone.

Notably, FD may share clinical features with other causes of cicatricial alopecia. In our patient, FD mimicked other entities including discoid lupus erythematosus, frontal fibrosing alopecia, dissecting cellulitis, and erosive pustular dermatosis (Table).1-14 Discoid lupus erythematosus manifests as round hypopigmented and hyperpigmented plaques with associated atrophy, perifollicular erythema, and follicular plugging. Frontal fibrosing alopecia is a primary lymphocytic scarring alopecia that manifests in a bandlike linear distribution over the frontal scalp and may involve the temporal scalp, posterior hairline, and/or eyebrows. Isolated hairs (known as lonely hairs) often are seen. Dissecting cellulitis is characterized by boggy nodules associated with alopecia on the scalp without notable epidermal change, although pustules and sinus tracts may develop.9 Erosive pustular dermatosis is a diagnosis of exclusion but often is seen in older adults with chronic sun damage and clinically manifests with eroded plaques with adherent crusts.10

While our patient presented with several overlapping clinical features, including progressive hair loss along the frontal scalp in a bandlike pattern suspicious for frontal fibrosing alopecia as well as atrophic depigmented plaques with adherent peripheral scaling suspicious for discoid lupus erythematosus, the presence of pustules was an important clue. The biopsy demonstrating a mixed infiltrate inclusive of neutrophils confirmed the diagnosis of FD.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Folliculitis Decalvans

Biopsy results revealed a brisk perifollicular and intrafollicular mixed inflammatory infiltrate comprising lymphocytes, neutrophils, and plasma cells filling the upper dermis and encircling dilated hair follicles. Elastic stain (Verhoeff-van Gieson) demonstrated loss of elastic fibers in areas of scarring. Periodic acid–Schiff with diastase staining was negative for fungal elements, while Gram staining revealed colonies of bacterial cocci in the stratum corneum and within the hair follicles. Immunofluorescence was unremarkable, and culture revealed methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus, leading to a diagnosis of folliculitis decalvans (FD). The patient was treated with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and received intralesional triamcinolone 2.5 mg/mL (total volume, 2 mL) every 6 weeks with considerable improvement in pustules, erythema, and scaling (Figure). While not yet in complete remission, our patient demonstrated short regrowing hairs in areas of incomplete scarring and focal remaining perifollicular erythema and scale along the midline frontal scalp 5 months after initial presentation.

Folliculitis decalvans is an uncommon subtype of cicatricial alopecia that may mimic other forms of alopecia. Cicatricial alopecia often is difficult to diagnose due to its overlapping clinical characteristics, but early diagnosis is essential for appropriate management and prevention of further permanent hair loss. Traditionally classified as a primary neutrophilic cicatricial alopecia, lymphocyte-predominant variants of FD now are recognized.1

Patients with FD typically present with patchy scarring alopecia at the vertex scalp that gradually expands and may demonstrate secondary features of follicular tufting and pustules.1-3 While the epidemiology of FD is poorly characterized, Vañó-Galván et al4 reported that FD accounted for 2.8% of all alopecia cases and 10.5% of cicatricial alopecia cases in a multicenter study of 2835 patients. The pathophysiology of FD still is under investigation but is thought to result from a dysregulated immune response to a chronic bacterial infection (eg, S aureus), with resulting neutrophilpredominant inflammation in early stages.1-3 Vañó-Galván et al4 reported that, among 35 patients with FD cultured for bacteria, 74% (26/35) returned positive results, 96% (25/26) of which grew S aureus.5

A systematic review of 20 studies that included 263 patients found rifampin and clindamycin to be the most common treatments for FD; however, there is insufficient evidence to determine if this treatment is the most effective.6 In our patient, clindamycin was avoided due to its propensity to negatively alter the gut microbiome long term.7 Other therapies such as oral tetracyclines, high-potency topical steroids, and intralesional triamcinolone also can be used to achieve disease remission.5,6 Other treatments such as isotretinoin, red-light photodynamic therapy, tacrolimus, and external beam radiation have been reported in the literature but vary in efficacy.6 Our patient improved on a regimen of topical benzoyl peroxide wash, oral doxycycline, and intralesional triamcinolone.

Notably, FD may share clinical features with other causes of cicatricial alopecia. In our patient, FD mimicked other entities including discoid lupus erythematosus, frontal fibrosing alopecia, dissecting cellulitis, and erosive pustular dermatosis (Table).1-14 Discoid lupus erythematosus manifests as round hypopigmented and hyperpigmented plaques with associated atrophy, perifollicular erythema, and follicular plugging. Frontal fibrosing alopecia is a primary lymphocytic scarring alopecia that manifests in a bandlike linear distribution over the frontal scalp and may involve the temporal scalp, posterior hairline, and/or eyebrows. Isolated hairs (known as lonely hairs) often are seen. Dissecting cellulitis is characterized by boggy nodules associated with alopecia on the scalp without notable epidermal change, although pustules and sinus tracts may develop.9 Erosive pustular dermatosis is a diagnosis of exclusion but often is seen in older adults with chronic sun damage and clinically manifests with eroded plaques with adherent crusts.10

While our patient presented with several overlapping clinical features, including progressive hair loss along the frontal scalp in a bandlike pattern suspicious for frontal fibrosing alopecia as well as atrophic depigmented plaques with adherent peripheral scaling suspicious for discoid lupus erythematosus, the presence of pustules was an important clue. The biopsy demonstrating a mixed infiltrate inclusive of neutrophils confirmed the diagnosis of FD.

- Olsen EA, Bergfeld WF, Cotsarelis G, et al. Summary of North American Hair Research Society (NAHRS)-sponsored Workshop on Cicatricial Alopecia, Duke University Medical Center, February 10 and 11, 2001. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:103-110. doi:10.1067/mjd.2003.68

- Filbrandt R, Rufaut N, Jones L. Primary cicatricial alopecia: diagnosis and treatment. CMAJ. 2013;185:1579-1585. doi:10.1503/cmaj.111570

- Otberg N, Kang H, Alzolibani AA, et al. Folliculitis decalvans. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21:238-244. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8019.2008.00204.x

- Vañó-Galván S, Saceda-Corralo D, Blume-Peytavi U, et al. Frequency of the types of alopecia at twenty-two specialist hair clinics: a multicenter study. Skin Appendage Disord. 2019;5:309-315. doi:10.1159/000496708

- Vañó-Galván S, Molina-Ruiz AM, Fernández-Crehuet P, et al. Folliculitis decalvans: a multicentre review of 82 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1750-1757. doi:10.1111/jdv.12993

- Rambhia PH, Conic RRZ, Murad A, et al. Updates in therapeutics for folliculitis decalvans: a systematic review with evidence-based analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:794-801. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.07.050

- Zimmermann P, Curtis N. The effect of antibiotics on the composition of the intestinal microbiota - a systematic review. J Infect. 2019;79:471-489. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2019.10.008

- Kanti V, Röwert-Huber J, Vogt A, et al. Cicatricial alopecia. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:435-461. doi:10.1111/ddg.13498

- Melo DF, Slaibi EB, Siqueira TMFM, et al. Trichoscopy findings in dissecting cellulitis. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:608-611. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2019.09.006

- Anzai A, Pirmez R, Vincenzi C, et al. Trichoscopy findings of frontal fibrosing alopecia on the eyebrows: a study of 151 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1130-1134. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.12.023

- Starace M, Loi C, Bruni F, et al. Erosive pustular dermatosis of the scalp: clinical, trichoscopic, and histopathologic features of 20 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:1109-1114. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.12.016

- Rongioletti F, Christana K. Cicatricial (scarring) alopecias: an overview of pathogenesis, classification, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:247-260. doi:10.2165/11596960-000000000-00000

- Badaoui A, Reygagne P, Cavelier-Balloy B, et al. Dissecting cellulitis of the scalp: a retrospective study of 51 patients and review of literature. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:421-423. doi:10.1111/bjd.13999

- Michelerio A, Vassallo C, Fiandrino G, et al. Erosive pustular dermatosis of the scalp: a clinicopathologic study of fifty cases. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2021;8:450-462. doi:10.3390/dermatopathology8040048

- Olsen EA, Bergfeld WF, Cotsarelis G, et al. Summary of North American Hair Research Society (NAHRS)-sponsored Workshop on Cicatricial Alopecia, Duke University Medical Center, February 10 and 11, 2001. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:103-110. doi:10.1067/mjd.2003.68

- Filbrandt R, Rufaut N, Jones L. Primary cicatricial alopecia: diagnosis and treatment. CMAJ. 2013;185:1579-1585. doi:10.1503/cmaj.111570

- Otberg N, Kang H, Alzolibani AA, et al. Folliculitis decalvans. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21:238-244. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8019.2008.00204.x

- Vañó-Galván S, Saceda-Corralo D, Blume-Peytavi U, et al. Frequency of the types of alopecia at twenty-two specialist hair clinics: a multicenter study. Skin Appendage Disord. 2019;5:309-315. doi:10.1159/000496708

- Vañó-Galván S, Molina-Ruiz AM, Fernández-Crehuet P, et al. Folliculitis decalvans: a multicentre review of 82 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1750-1757. doi:10.1111/jdv.12993

- Rambhia PH, Conic RRZ, Murad A, et al. Updates in therapeutics for folliculitis decalvans: a systematic review with evidence-based analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:794-801. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.07.050

- Zimmermann P, Curtis N. The effect of antibiotics on the composition of the intestinal microbiota - a systematic review. J Infect. 2019;79:471-489. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2019.10.008

- Kanti V, Röwert-Huber J, Vogt A, et al. Cicatricial alopecia. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:435-461. doi:10.1111/ddg.13498

- Melo DF, Slaibi EB, Siqueira TMFM, et al. Trichoscopy findings in dissecting cellulitis. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:608-611. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2019.09.006

- Anzai A, Pirmez R, Vincenzi C, et al. Trichoscopy findings of frontal fibrosing alopecia on the eyebrows: a study of 151 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1130-1134. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.12.023

- Starace M, Loi C, Bruni F, et al. Erosive pustular dermatosis of the scalp: clinical, trichoscopic, and histopathologic features of 20 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:1109-1114. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.12.016

- Rongioletti F, Christana K. Cicatricial (scarring) alopecias: an overview of pathogenesis, classification, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:247-260. doi:10.2165/11596960-000000000-00000

- Badaoui A, Reygagne P, Cavelier-Balloy B, et al. Dissecting cellulitis of the scalp: a retrospective study of 51 patients and review of literature. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:421-423. doi:10.1111/bjd.13999

- Michelerio A, Vassallo C, Fiandrino G, et al. Erosive pustular dermatosis of the scalp: a clinicopathologic study of fifty cases. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2021;8:450-462. doi:10.3390/dermatopathology8040048

Alopecia and Pruritic Rash on the Forehead and Scalp

Alopecia and Pruritic Rash on the Forehead and Scalp

A 52-year-old woman presented to the dermatology department with an intermittently pruritic rash in a bandlike distribution on the left upper forehead and the frontal and temporal scalp of 4 years’ duration. The rash initially was diagnosed as psoriasis at an outside facility. Treatment over the year prior to presentation included tildrakizumab-asmn; topical crisaborole 2%; and excimer laser, which was complicated by blistering. The patient reported no history of topical or injected steroid use in the involved areas. Physical examination at the current presentation revealed arcuate erythematous plaques with follicular prominence, perifollicular scaling, pustules, and lone hairs. There also were porcelain-white atrophic plaques with loss of follicular ostia that were most prominent over the temporal scalp. A biopsy of the left lateral forehead was performed.

Management of Facial Hair in Women

Facial hair growth in women is complex and multifaceted. It is not a disease but rather a part of normal anatomy or a symptom influenced by an underlying condition such as hypertrichosis, a hormonal imbalance (eg, hirsutism due to polycystic ovary syndrome [PCOS]), mechanical factors such as pseudofolliculitis barbae (PFB) from shaving, and perimenopausal and postmenopausal hormonal shifts. Additionally, normal facial hair patterns can vary substantially based on genetics, ethnicity, and cultural background. Some populations may naturally have more visible vellus or terminal hairs on the face, which are entirely physiologic rather than indicative of an underlying disorder. Despite this, societal expectations and beauty standards across many cultures dictate that facial hair in women is undesirable, often associating hair-free skin with femininity and attractiveness. This perception drives many women to seek treatment—not necessarily for medical reasons, but due to social pressure and aesthetic preferences.

Hypertrichosis, whether congenital or acquired, refers to excessive hair growth that is not androgen dependent and can appear on any site of the body. Causes include genetic predisposition, porphyria, thyroid disorders, internal malignancies, malnutrition, anorexia nervosa, or use of medications such as cyclosporine, prednisolone, and phenytoin.1 Hirsutism, by contrast, is characterized by the growth of terminal hairs in women at androgen-dependent sites such as the face, neck, and upper chest, where coarse hair typically grows in men.2 This condition often is associated with excess androgens produced by the ovaries or adrenal glands, most commonly due to PCOS although genetic factors may contribute.

Before initiating treatment, a thorough history and physical examination are essential to determine the underlying cause of conditions associated with facial hair growth in women. Clinicians should assess for signs of hyperandrogenism, menstrual irregularities, virilization, medication use, and family history. In cases of a suspected endocrine disorder, further laboratory evaluation may be warranted to guide appropriate management. While each cause of facial hair growth in women has unique management considerations, the shared impact on psychosocial well-being and adherence to grooming standards in the US military warrants an all-encompassing yet targeted approach. This comprehensive review discusses management options for women with facial hair in the military based on a review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE conducted in November 2024 using combinations of the following search terms: hirsutism, facial hair, pseudofolliculitis barbae, women, female, military, grooming standards, hyperandrogenism, and hair removal.

Treatment Modalities

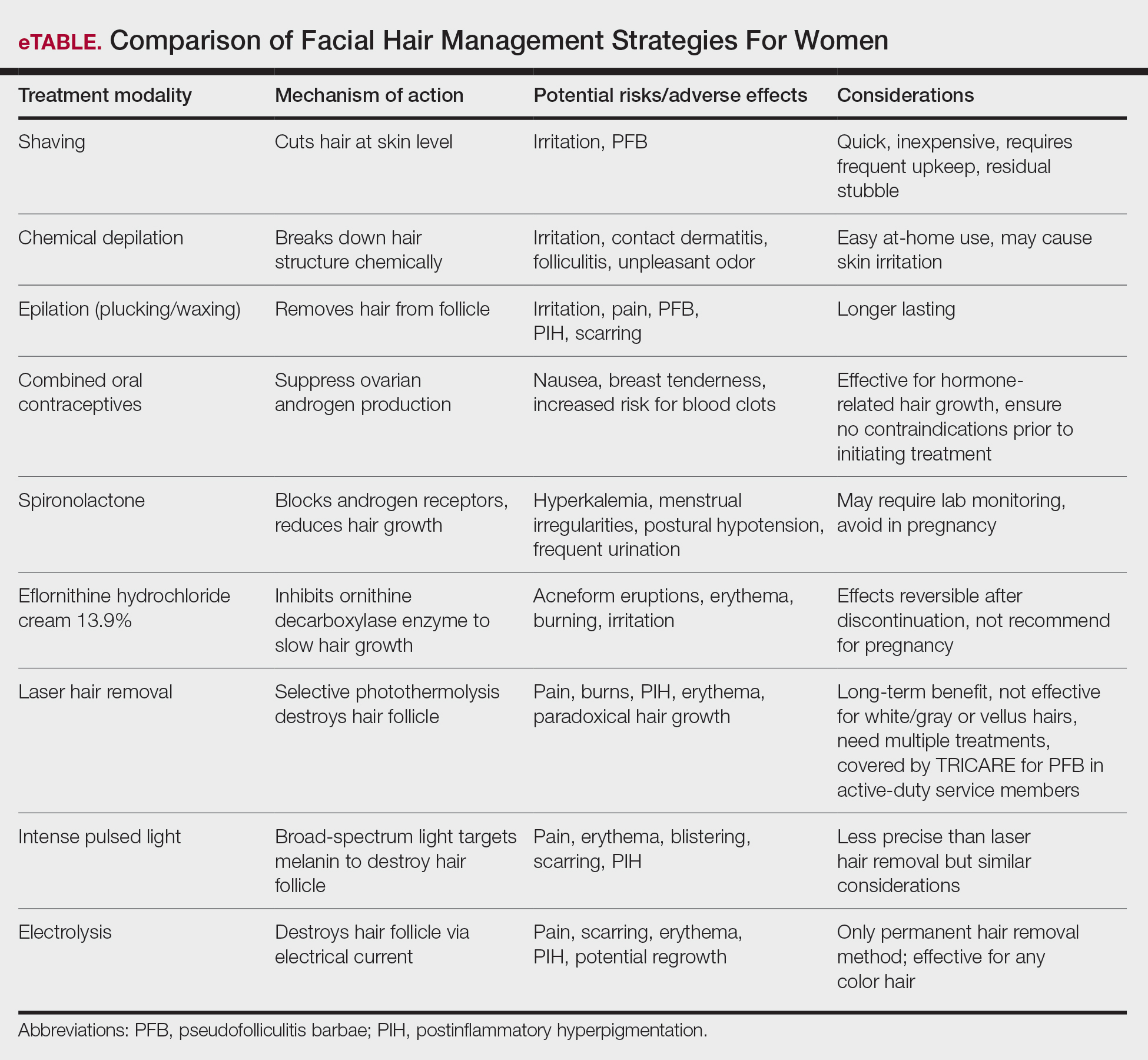

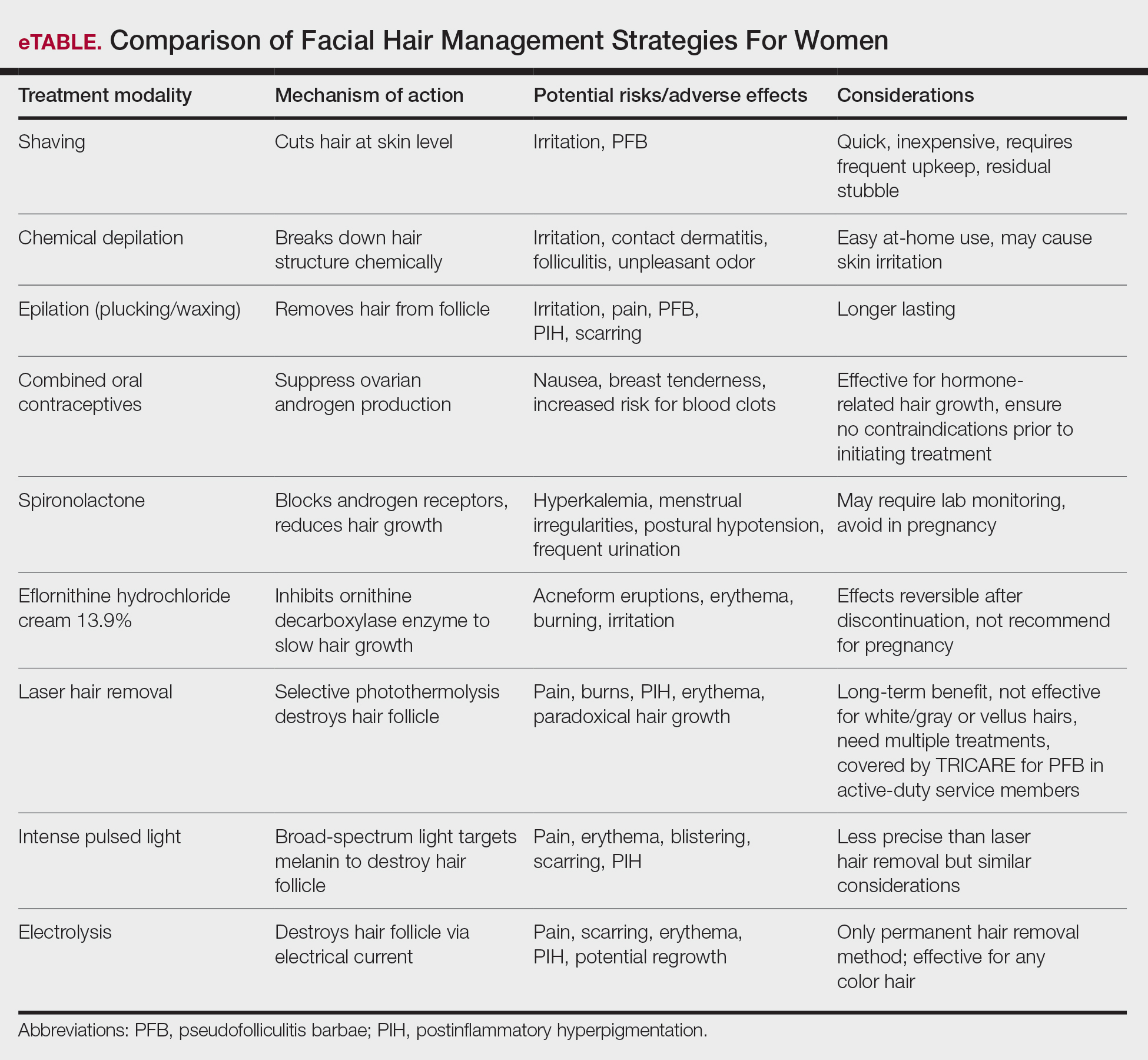

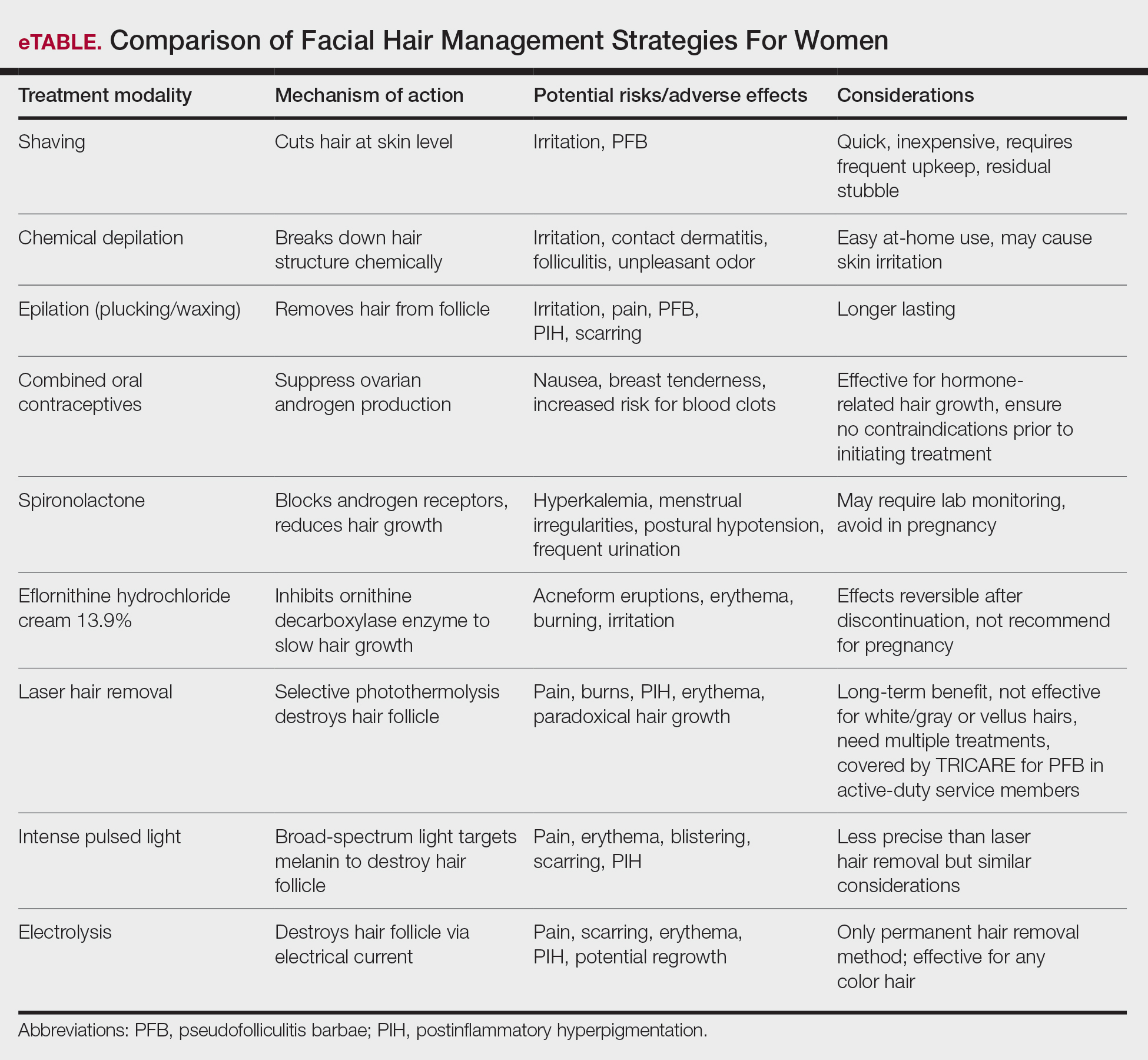

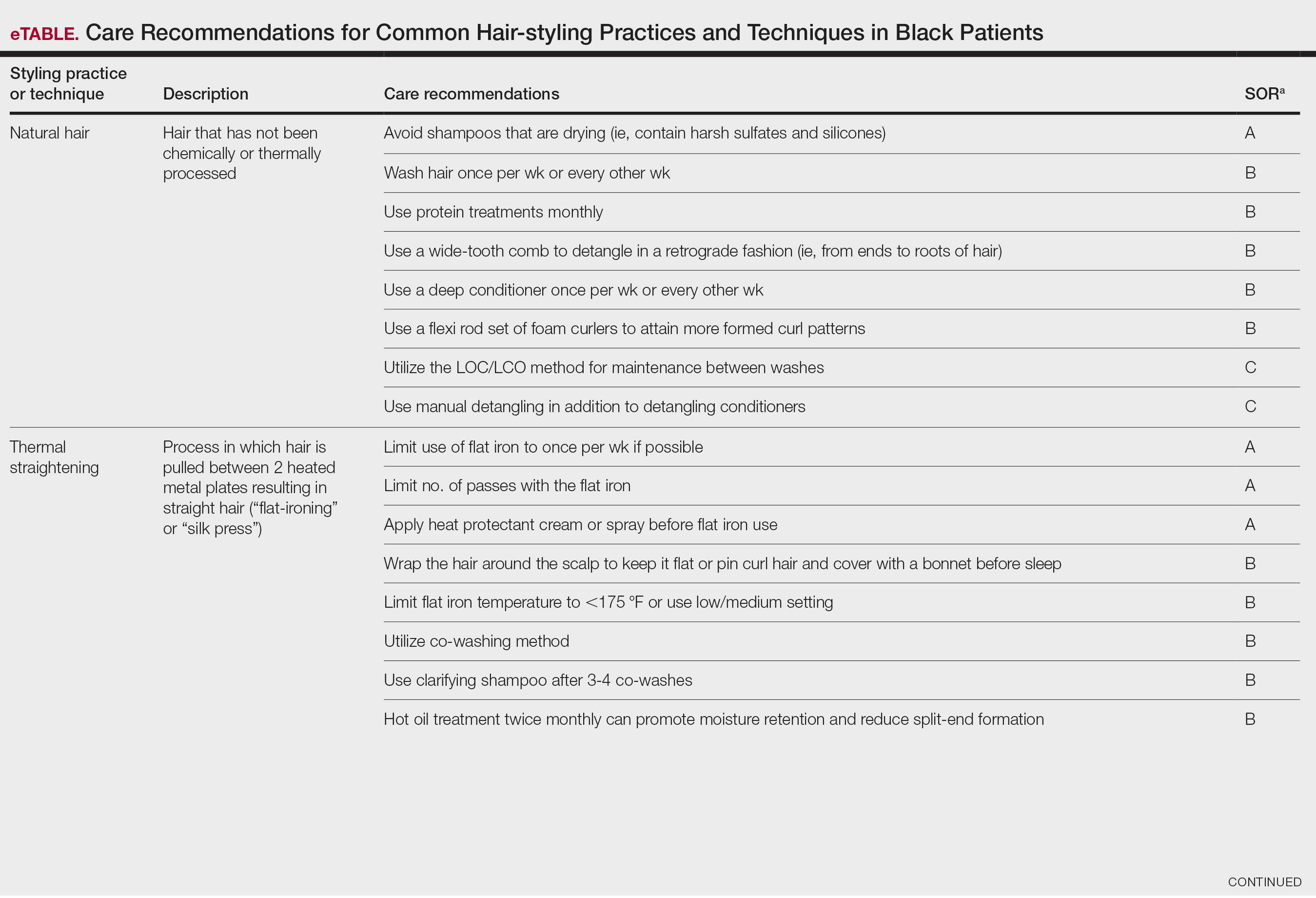

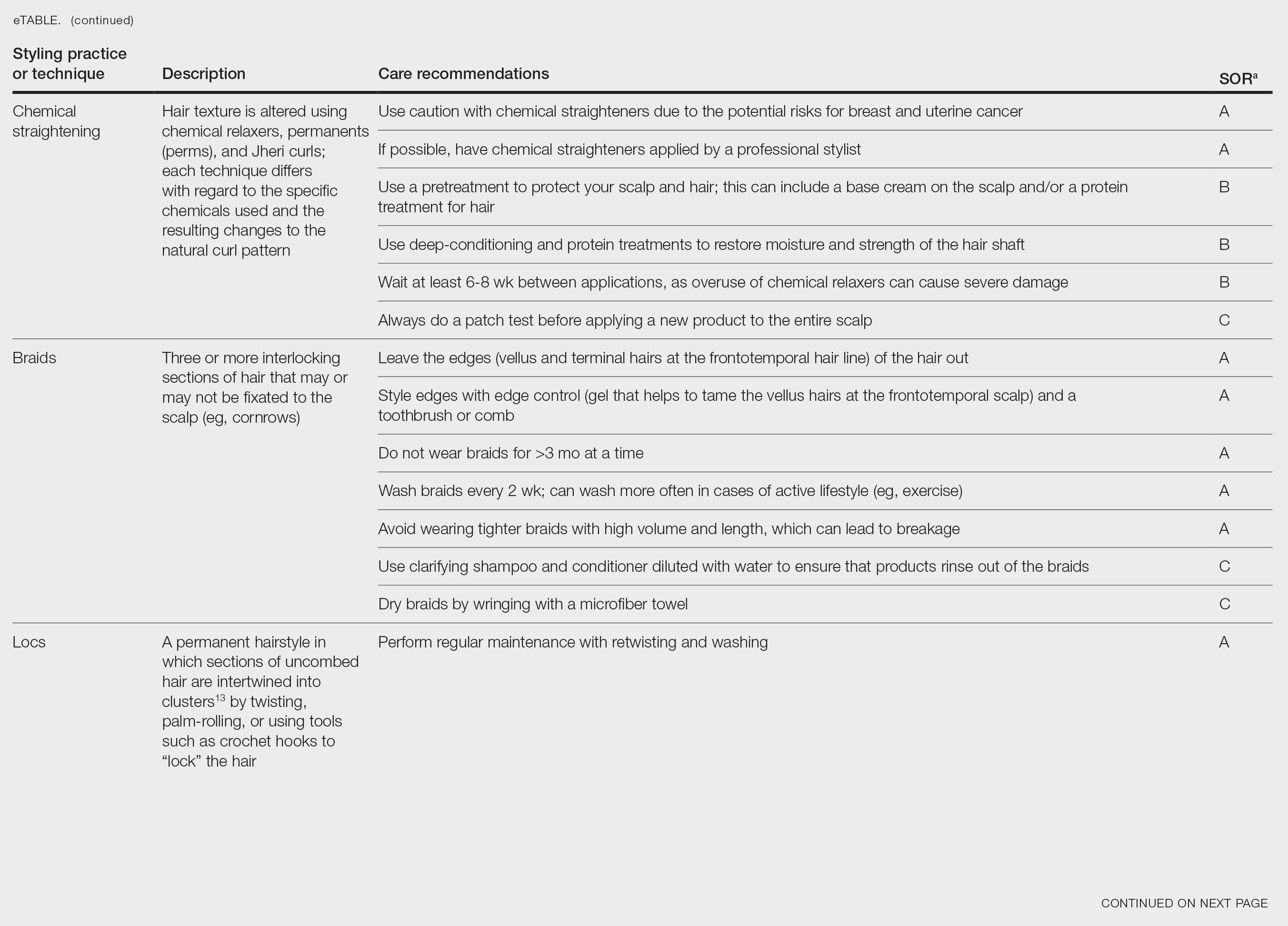

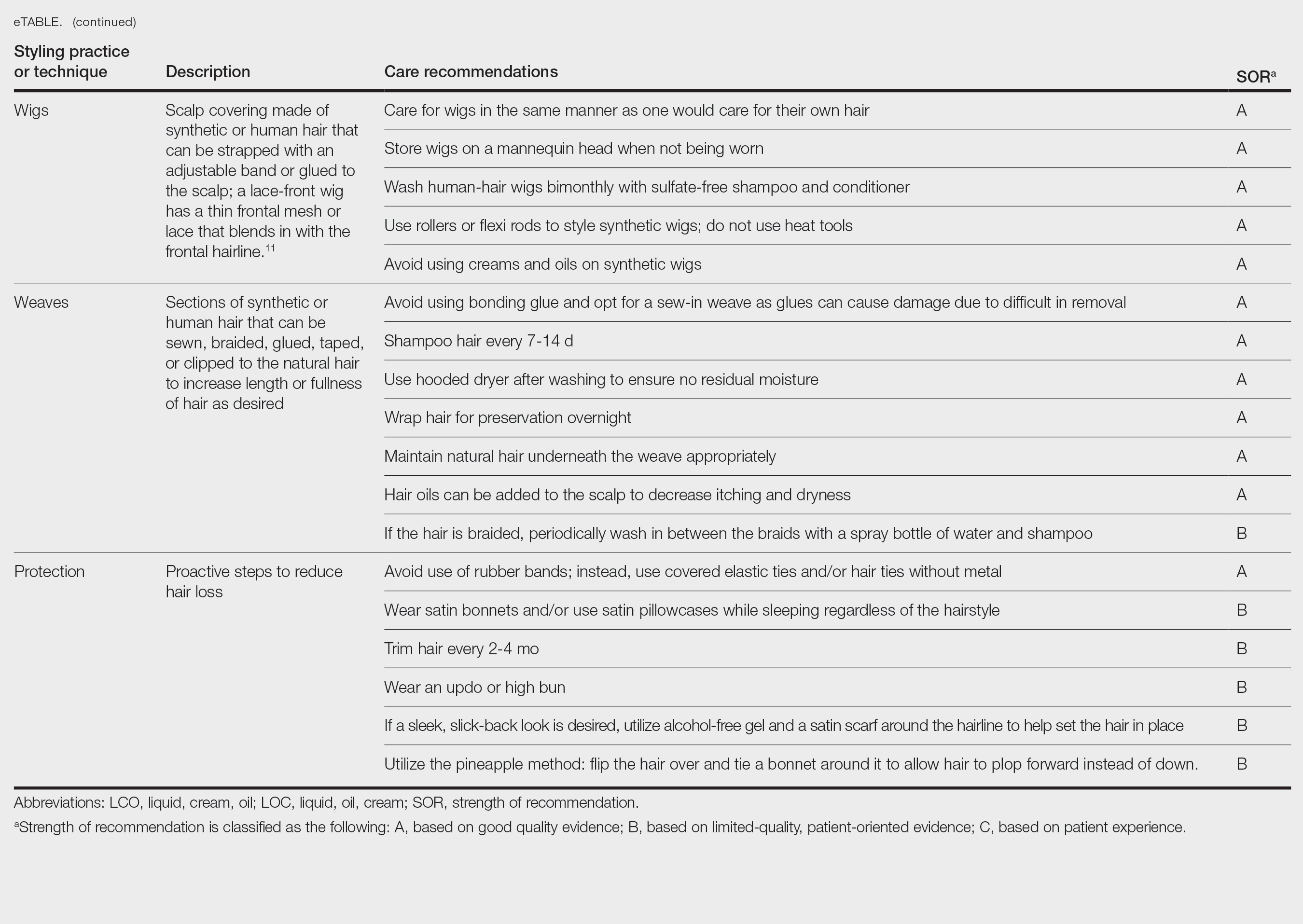

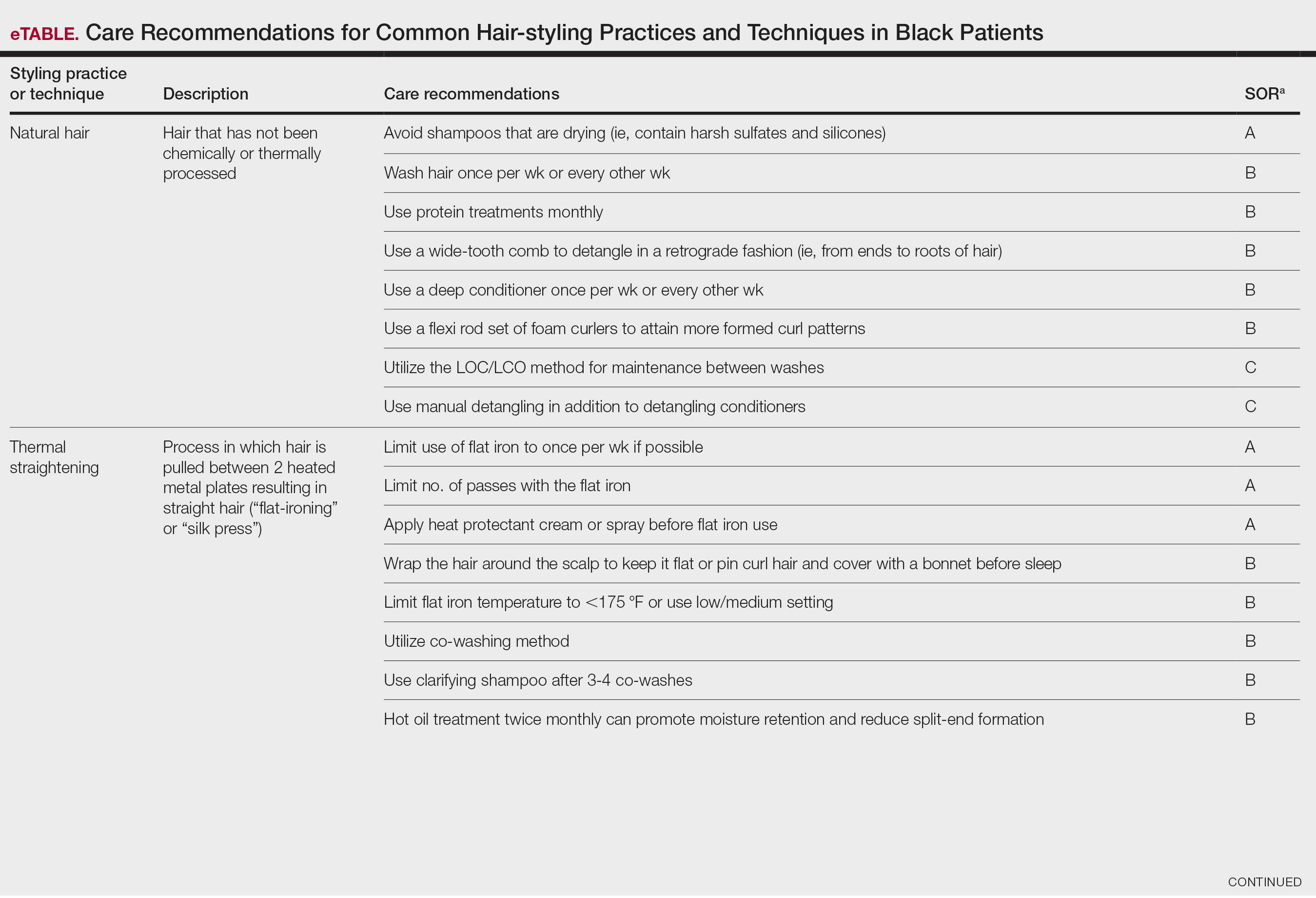

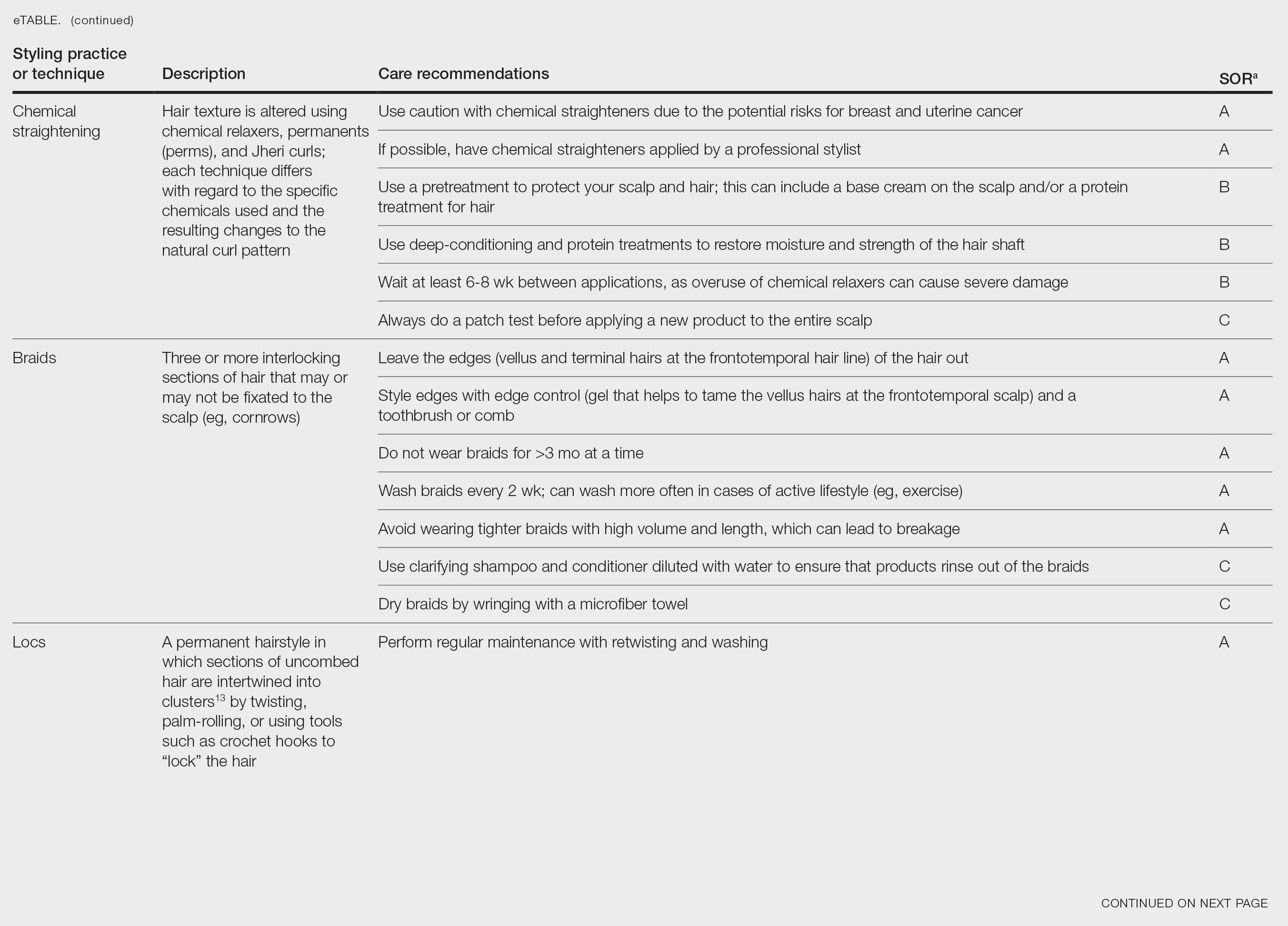

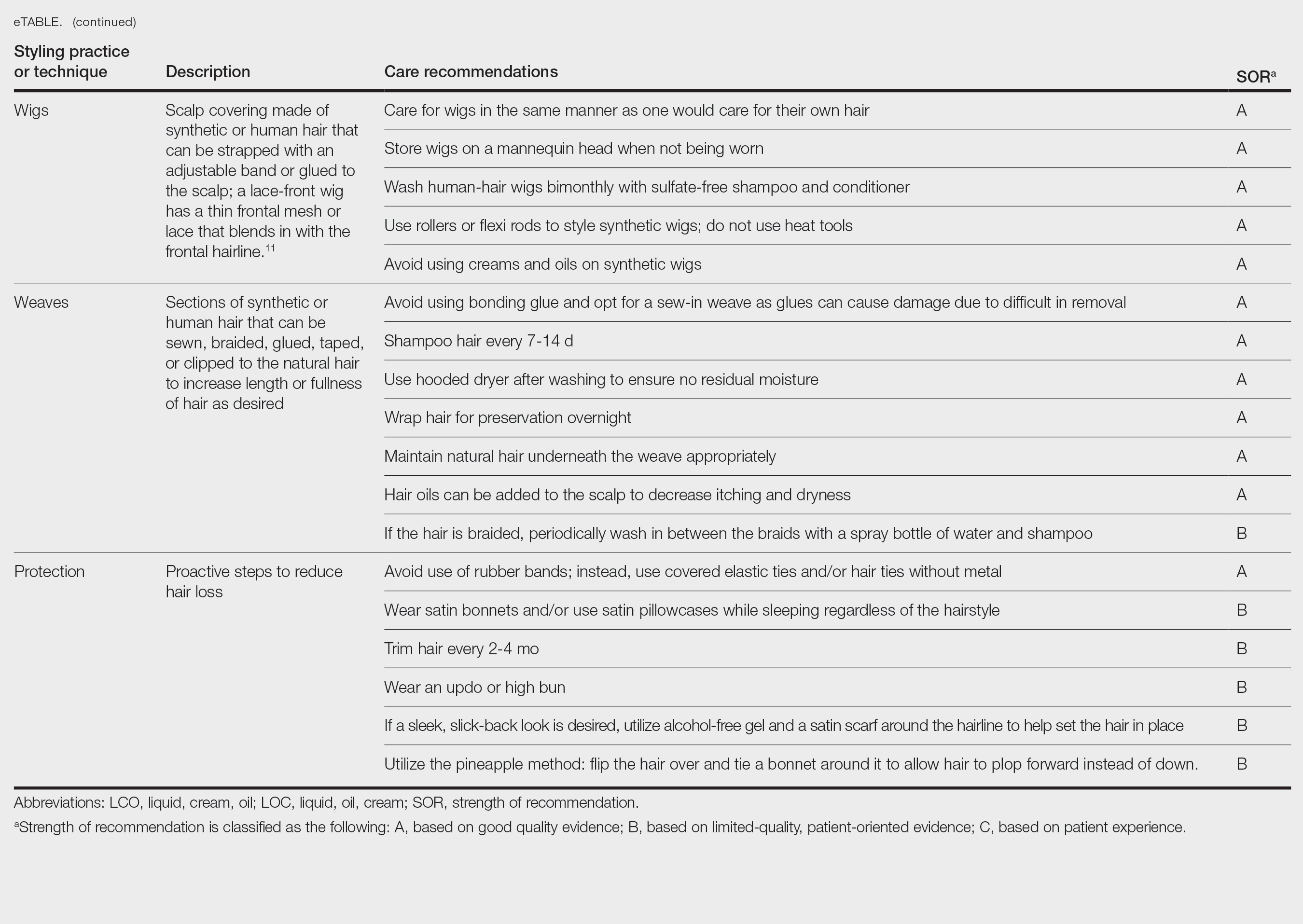

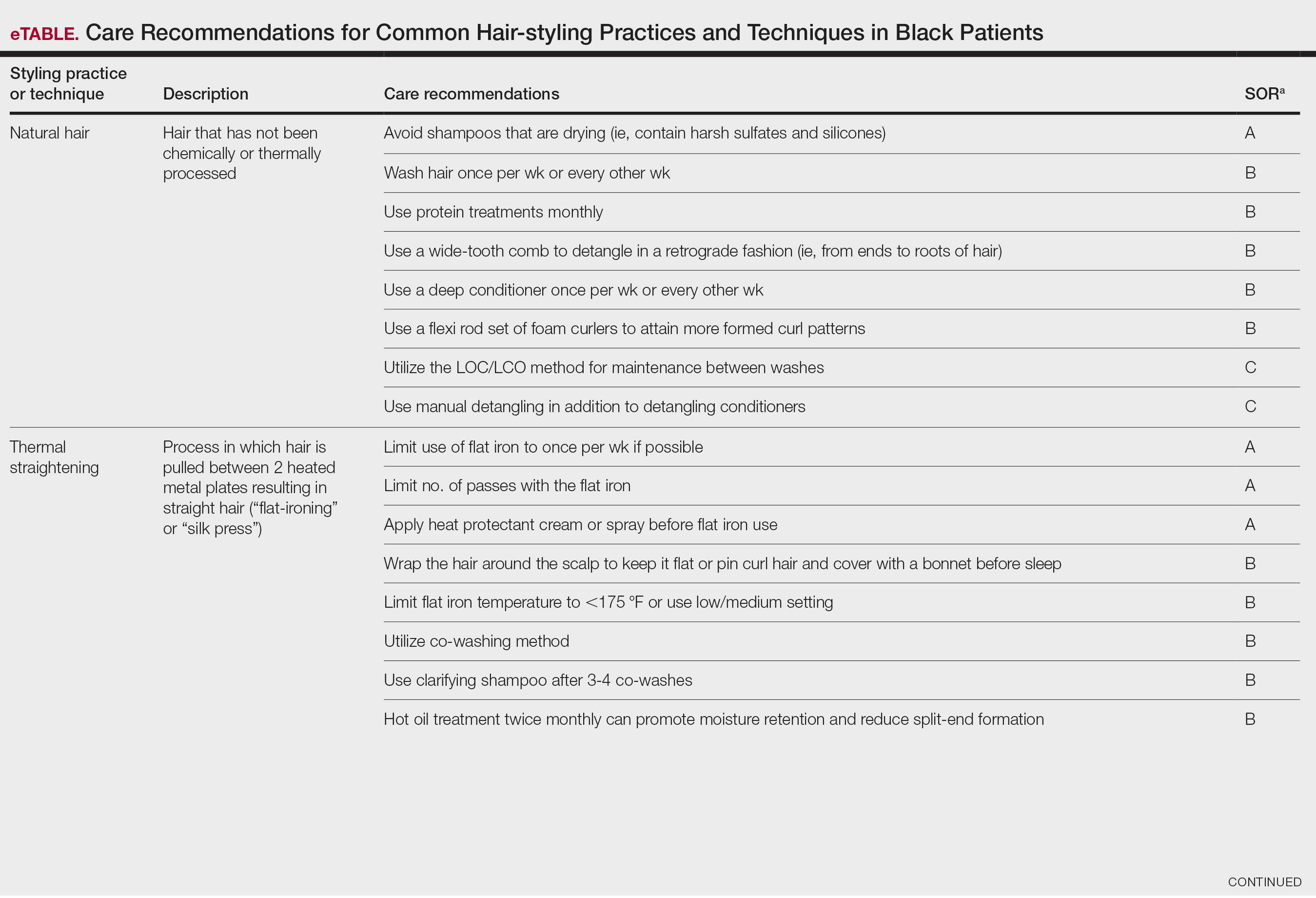

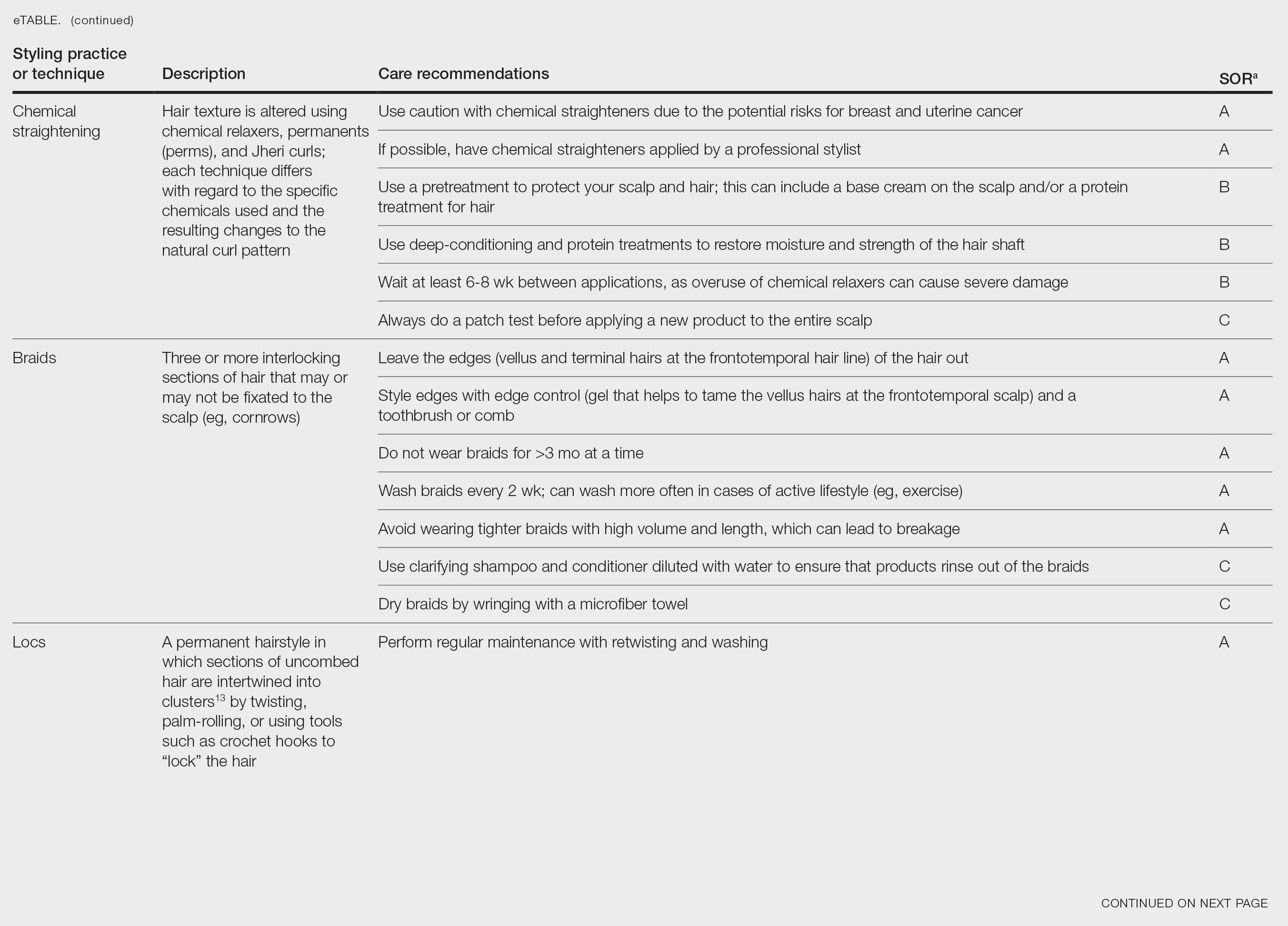

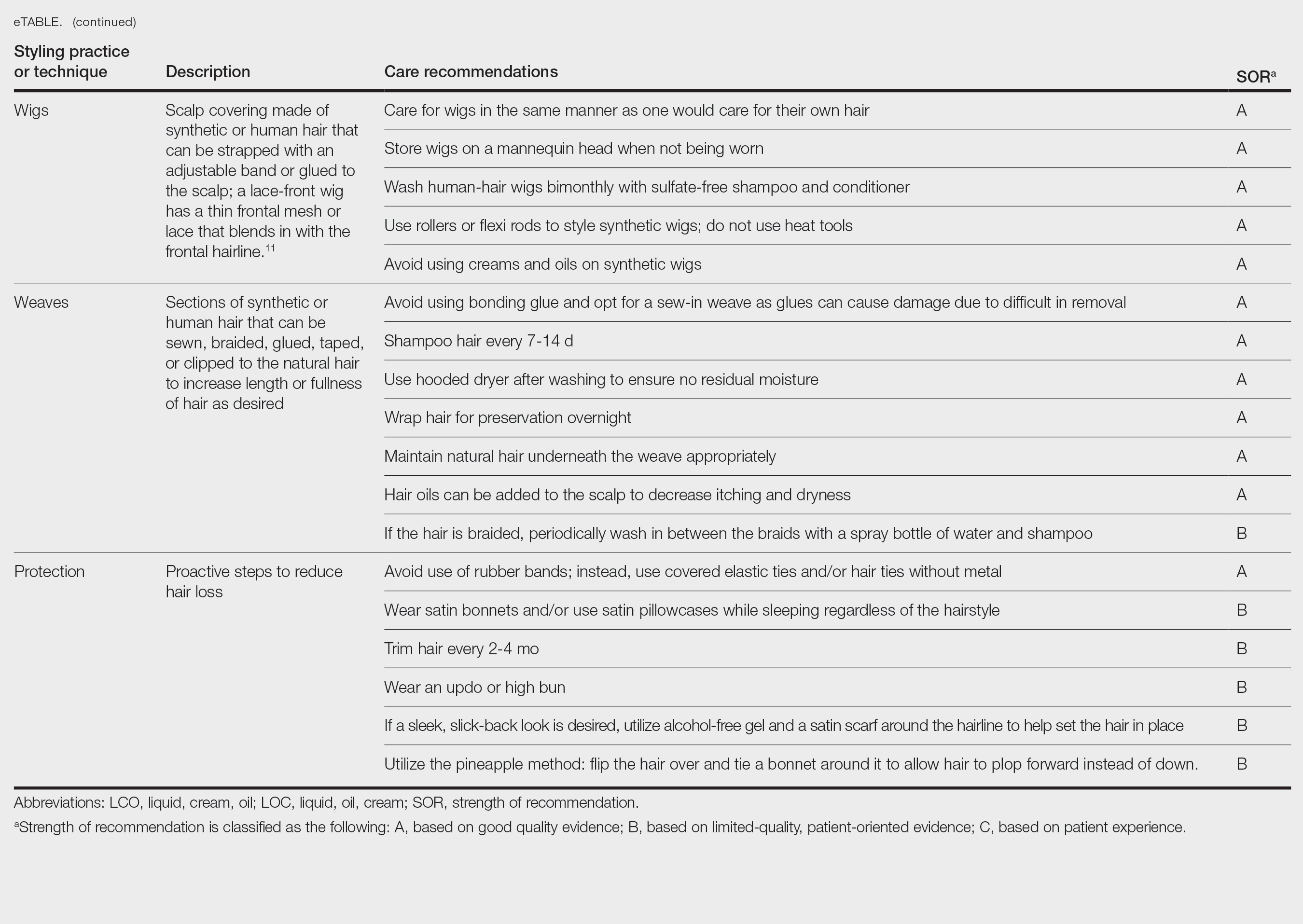

The available treatment modalities, including their mechanisms, potential risks, and considerations are summarized in the eTable.

Mechanical—Shaving remains one of the most widely utilized methods of hair removal in women due to its accessibility and ease of use. It does not disrupt the anagen phase of the hair growth cycle, making it a temporary method that requires frequent repetition (often daily), particularly for individuals with rapid hair growth. The belief that shaving causes hair to grow back thicker or faster is a common misconception. Shaving does not alter the thickness or growth rate of hair; instead, it leaves a blunt tip, making the hair feel coarser or appear thicker than uncut hair.3 Despite its relative convenience, shaving can lead to skin irritation due to mechanical trauma. Potential complications include PFB, superficial abrasions known more broadly as shaving irritation, and an increased risk for infections such as bacterial or fungal folliculitis.4

Chemical depilation, which uses thioglycolates mixed with alkali compounds, disrupts disulfide bonds in the hair, effectively breaking down the shaft without affecting the bulb. The depilatory requires application to the skin for approximately 3 to 15 minutes depending on the specific formulation and the thickness or texture of the hair. While it is a cost-effective option that easily can be done at home, the chemicals involved may trigger irritant contact dermatitis or folliculitis and produce an unpleasant odor from hydrogen disulfide gas.5 They also can lead to PFB.

Epilation removes the entire hair shaft and bulb, with results lasting approximately 6 weeks.6 Methods range from using tweezers to pluck single hairs and devices that simultaneously remove multiple hairs to hot or cold waxing, which use resin to grip and remove hair. Threading is a technique that uses twisted thread to remove the hair at the follicle level; this method may not alter hair growth unless performed during the anagen phase, during which repeated plucking can damage the matrix and potentially lead to permanent hair reduction.5 Common adverse effects include pain during removal, burns from waxing, folliculitis, PFB, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, and scarring, particularly when multiple hairs are removed at once.

Pharmacologic—Pharmacologic therapy commonly is used to manage hirsutism and typically begins with a trial of combined oral contraceptives (COCs) containing estrogen and progestin, which are considered the first-line option unless contraindicated.7 If response to COC monotherapy is inadequate, an antiandrogen such as spironolactone may be added. Combination therapy with a COC and an antiandrogen generally is reserved for severe cases or patients who previously have shown suboptimal response to COCs alone.7 Patients should be counseled to discontinue antiandrogen therapy if they become pregnant due to the risk for fetal undervirilization observed in animal studies.8,9 Typical dosing of spironolactone, a competitive inhibitor of 5-α-reductase and androgen receptors, ranges from 100 mg to 200 mg daily.10 Reported adverse effects include polyuria, postural hypotension, menstrual irregularities, hyperkalemia, and potential liver dysfunction. Although spironolactone has demonstrated tumorigenic effects in animal studies, no such effects have been observed in humans.11

Eflornithine hydrochloride cream 13.9% is the first topical prescription medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for reduction of unwanted facial hair in women.12 It works by irreversibly blocking the activity of ornithine decarboxylase, an enzyme involved in the rate-limiting step of polyamine synthesis, which is essential for hair growth. In a randomized, double-blind clinical trial evaluating its effectiveness and safety, twice-daily application for 24 weeks resulted in a clinically meaningful reduction in hair length and density (measured as surface area) compared with the control group.13 When eflornithine hydrochloride cream 13.9% is discontinued, hair growth gradually returns to baseline. Studies have shown that hair regrowth typically begins within 8 weeks after treatment is stopped; within several months, hair returns to pretreatment levels.14 Adverse effects of eflornithine hydrochloride cream generally are mild and may include local irritation and acneform eruptions. In a randomized bilateral vehicle-controlled trial of 31 women, both eflornithine and vehicle creams were well tolerated, with 1 patient reporting mild tingling with eflornithine that resolved with continued use for 7 days.15

Procedural—Photoepilation therapies widely are considered by dermatologists to be among the most effective methods for reducing unwanted hair.16 Laser hair removal employs selective photothermolysis, a principle by which specific wavelengths of light target melanin in hair follicles. This method results in localized thermal damage, destroying hair follicles and reducing regrowth. Wavelengths between 600 and 1100 nm are most effective for hair removal; widely used devices include the ruby (694 nm), alexandrite (755 nm), diode (800-810 nm), and long-pulsed Nd:YAG lasers (1064 nm). Cooling mechanisms such as cryogen spray or contact cooling often are employed to minimize epidermal damage and lessen patient discomfort.

The hair matrix is most responsive to laser treatment during the anagen phase, necessitating multiple sessions to ensure all hairs are treated during this optimal growth stage. Generally, 4 to 6 sessions spaced at intervals of 4 to 6 weeks are required to achieve satisfactory results.17 Matching the laser wavelength to the absorption properties of melanin—the target chromophore—enables selective destruction of melanin-rich hair follicles while minimizing damage to surrounding skin.

The ideal laser wavelength primarily affects melanin concentrated in the hair bulb, leading to follicular destruction while reducing the risk for unintended depigmentation of the epidermis; however, competing structures in the skin (eg, epidermal pigment) also can absorb laser energy, diminishing treatment efficacy and increasing the risk for adverse effects. Shorter wavelengths are effective for lighter skin types, while longer wavelengths such as the Nd:YAG laser are safer for individuals with darker skin types as they bypass melanin in the epidermis.

It is important to note that laser hair removal is ineffective for white and gray hairs due to the lack of melanin. As a result, alternative methods such as electrolysis, which does not rely on pigment, may be more appropriate for permanent hair removal in individuals with nonpigmented hairs. Research indicates that combining topical eflornithine with alexandrite or Nd:YAG lasers improves outcomes for reducing unwanted facial hair.18

In military settings, laser hair removal is utilized for specific conditions such as PFB in male service members to assist with the reduction of hair and mitigation of symptoms.19 The majority of military dermatology clinics have devices for laser hair removal; however, dermatology services are not available at many military treatment facilities, and dermatologic care may be provided by the local civilian dermatologists. That said, laser therapy is covered in the civilian sector for active-duty service members with PFB of the face and neck under certain criteria. These include a documented safety risk in environments requiring respiratory protection, failure of conservative treatments, and evaluation by a military dermatologist who confirms the necessity of civilian-provided laser therapy when it is unavailable at a military facility.20 While such policies demonstrate the military’s recognition of laser therapy as a viable solution for certain grooming-related conditions, many are unaware that the existing laser hair removal policy also applies to women. Increasing awareness of this coverage could help female service members access treatment options that align with both medical and professional grooming needs.

Intense pulsed light (IPL) systems are nonlaser devices that emit broad-spectrum light in the 590- to 1200-nm range. They utilize a flash lamp to achieve thermal damage. Filters are used to narrow the wavelength range based on the specific target. Intense pulsed light devices are less precise than lasers but remain effective for hair reduction. In addition to hair removal, IPL devices are employed in the treatment of pigmented and vascular lesions. Common adverse effects of both laser and IPL hair removal include transient erythema, perifollicular edema, and pigmentary changes, especially in patients with darker skin types. Rare complications include blistering, scarring, and paradoxical hair stimulation in which untreated areas develop increased hair growth.

Electrolysis is recognized as the only method of truly permanent hair removal and is effective for all hair colors.21 However, the variability in technique among practitioners often leads to inconsistent results, with some patients experiencing hair regrowth. Galvanic electrolysis involves inserting a fine needle into the hair follicle and applying an electrical current to destroy the it and the rapidly dividing cells of the matrix.22 The introduction of thermolytic electrolysis, which uses a high-frequency alternating current (commonly 13.56 MHz or 27.12 MHz), has enhanced efficiency by creating heat at the needle tip to destroy the follicle. This approach is faster and now is commonly combined with galvanic electrolysis.23 While no controlled clinical trials directly compare these methods, many patients experience permanent hair removal, with approximately 15% to 25% regrowth within 6 months.22,24

Alternative Options—Home-use laser and light-based devices have become increasingly popular for managing unwanted hair due to their affordability and convenience, with most devices priced less than $1000.25 These devices utilize various technologies, including lasers (808 nm), IPL, or combinations of IPL and radiofrequency.26 Despite their accessibility, peer-reviewed research on their safety profile and effectiveness is limited, as existing data primarily come from industry-funded, uncontrolled studies with short follow-up durations—making it difficult to assess long-term outcomes.25

Psychosocial Impact

A 2023 study of active-duty female service members with PCOS highlighted the unique challenges they face while managing symptoms such as facial hair within the constraints of military service.27 Although the study focused on PCOS, the findings shed light on how facial hair specifically impacts the psychological well-being of servicewomen. Participants described facial hair as one of the most visible and stigmatizing symptoms, often leading to feelings of embarrassment and diminished confidence. Participants also highlighted the professional implications of facial hair, with some describing feelings of scrutiny and judgment from peers and leadership in public. These challenges can be more pronounced in deployments or field exercises where hygiene resources are limited. The lack of access not only affects self-perception but also can hinder the ability of servicewomen to meet implicit expectations for grooming and appearance.27 There is a notable gap in research examining the impact of facial hair on military servicewomen. Given the unique environmental challenges and professional expectations, further investigation is warranted to better understand how facial hair affects women and to optimize treatment approaches in this population.

Final Thoughts

Limited awareness and understanding of facial hair in woman contribute to stigma, often leaving affected individuals to navigate challenges in isolation. Given the impact on confidence, professional appearance, and adherence to military grooming standards, it is essential for health care practitioners to recognize and address facial hair in women. Importantly, laser hair removal is covered by TRICARE for active-duty female service members with PFB, yet many remain unaware of this benefit. Increased awareness of available mechanical, pharmacologic, and procedural treatment options allows for tailored management, ensuring that women receive appropriate medical care.

Wendelin DS, Pope DN, Mallory SB. Hypertrichosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:161-181. doi:10.1067/mjd.2003.100

Blume-Peytavi U, Hahn S. Medical treatment of hirsutism. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21:329-339. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8019.2008.00215.x

Kang CN, Shah M, Lynde C, et al. Hair removal practices: a literature review. Skin Therapy Lett. 2021;26:6-11.

Matheson E, Bain J. Hirsutism in women. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100:168-175.

Shenenberger DW, Utecht LM. Removal of unwanted facial hair. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66:1907-1911.

Johnson E, Ebling FJ. The effect of plucking hairs during different phases of the follicular cycle. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1964;12:465-474.

Martin KA, Anderson RR, Chang RJ, et al. Evaluation and treatment of hirsutism in premenopausal women: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103:1233-1257. doi:10.1210/jc.2018-00241

Barrionuevo P, Nabhan M, Altayar O, et al. Treatment options for hirsutism: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103:1258-1264. doi:10.1210/jc.2017-02052

Alesi S, Forslund M, Melin J, et al. Efficacy and safety of anti-androgens in the management of polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. EClinicalMedicine. Published online August 9, 2023. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102162

Escobar-Morreale HF, Carmina E, Dewailly D, et al. Epidemiology, diagnosis and management of hirsutism: a consensus statement. Hum Reprod Update. 2012;18:146-170.

Hussein RS, Abdelbasset WK. Updates on hirsutism: a narrative review. Int J Biomedicine. 2022;12:193-198. doi:10.21103/Article12(2)_RA4

Shapiro J, Lui H. Vaniqa—eflornithine 13.9% cream. Skin Therapy Lett. 2001;6:1-5.

Wolf JE Jr, Shander D, Huber F, et al. Randomized, double-blind clinical evaluation of the efficacy and safety of topical eflornithine HCl 13.9% cream in the treatment of women with facial hair. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:94-98. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.03079.x

Balfour JA, McClellan K. Topical eflornithine. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2001;2:197-202. doi:10.2165/00128071-200102030-00009

Hamzavi I, Tan E, Shapiro J, et al. A randomized bilateral vehicle-controlled study of eflornithine cream combined with laser treatment versus laser treatment alone for facial hirsutism in women. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:54-59. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.09.025

Goldberg DJ. Laser hair removal. In: Goldberg DJ, ed. Laser Dermatology: Pearls and Problems. Blackwell; 2008.

Hussain M, Polnikorn N, Goldberg DJ. Laser-assisted hair removal in Asian skin: efficacy, complications, and the effect of single versus multiple treatments. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:249-254. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2003.29059.x

Smith SR, Piacquadio DJ, Beger B, et al. Eflornithine cream combined with laser therapy in the management of unwanted facial hair growth in women: a randomized trial. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:1237-1243. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2006.32282.x

Jung I, Lannan FM, Weiss A, et al. Treatment and current policies on pseudofolliculitis barbae in the US military. Cutis. 2023;112:299-302. doi:10.12788/cutis.0907

TRICARE Operations Manual 6010.59-M. Supplemental Health Care Program (SHCP)—Chapter 17. Contractor Responsibilities. Military Health System and Defense Health Agency website. Revised November 5, 2021. Accessed February 13, 2024. https://manuals.health.mil/pages/DisplayManualHtmlFile/2022-08-31/AsOf/TO15/C17S3.html

Yanes DA, Smith P, Avram MM. A review of best practices for gender-affirming laser hair removal. Dermatol Surg. 2024;50:S201-S204. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000004441

Wagner RF Jr, Tomich JM, Grande DJ. Electrolysis and thermolysis for permanent hair removal. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:441-449. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(85)70062-x

Olsen EA. Methods of hair removal. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:143-157. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70181-7

Kligman AM, Peters L. Histologic changes of human hair follicles after electrolysis: a comparison of two methods. Cutis. 1984;34:169-176.

Hession MT, Markova A, Graber EM. A review of hand-held, home-use cosmetic laser and light devices. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:307-320. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000283

Wheeland RG. Permanent hair reduction with a home-use diode laser: safety and effectiveness 1 year after eight treatments. Lasers Surg Med. 2012;44:550-557. doi:10.1002/lsm.22051

Hopkins D, Walker SC, Wilson C, et al. The experience of living with polycystic ovary syndrome in the military. Mil Med. 2024;189:E188-E197. doi:10.1093/milmed/usad241

Facial hair growth in women is complex and multifaceted. It is not a disease but rather a part of normal anatomy or a symptom influenced by an underlying condition such as hypertrichosis, a hormonal imbalance (eg, hirsutism due to polycystic ovary syndrome [PCOS]), mechanical factors such as pseudofolliculitis barbae (PFB) from shaving, and perimenopausal and postmenopausal hormonal shifts. Additionally, normal facial hair patterns can vary substantially based on genetics, ethnicity, and cultural background. Some populations may naturally have more visible vellus or terminal hairs on the face, which are entirely physiologic rather than indicative of an underlying disorder. Despite this, societal expectations and beauty standards across many cultures dictate that facial hair in women is undesirable, often associating hair-free skin with femininity and attractiveness. This perception drives many women to seek treatment—not necessarily for medical reasons, but due to social pressure and aesthetic preferences.

Hypertrichosis, whether congenital or acquired, refers to excessive hair growth that is not androgen dependent and can appear on any site of the body. Causes include genetic predisposition, porphyria, thyroid disorders, internal malignancies, malnutrition, anorexia nervosa, or use of medications such as cyclosporine, prednisolone, and phenytoin.1 Hirsutism, by contrast, is characterized by the growth of terminal hairs in women at androgen-dependent sites such as the face, neck, and upper chest, where coarse hair typically grows in men.2 This condition often is associated with excess androgens produced by the ovaries or adrenal glands, most commonly due to PCOS although genetic factors may contribute.

Before initiating treatment, a thorough history and physical examination are essential to determine the underlying cause of conditions associated with facial hair growth in women. Clinicians should assess for signs of hyperandrogenism, menstrual irregularities, virilization, medication use, and family history. In cases of a suspected endocrine disorder, further laboratory evaluation may be warranted to guide appropriate management. While each cause of facial hair growth in women has unique management considerations, the shared impact on psychosocial well-being and adherence to grooming standards in the US military warrants an all-encompassing yet targeted approach. This comprehensive review discusses management options for women with facial hair in the military based on a review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE conducted in November 2024 using combinations of the following search terms: hirsutism, facial hair, pseudofolliculitis barbae, women, female, military, grooming standards, hyperandrogenism, and hair removal.

Treatment Modalities

The available treatment modalities, including their mechanisms, potential risks, and considerations are summarized in the eTable.

Mechanical—Shaving remains one of the most widely utilized methods of hair removal in women due to its accessibility and ease of use. It does not disrupt the anagen phase of the hair growth cycle, making it a temporary method that requires frequent repetition (often daily), particularly for individuals with rapid hair growth. The belief that shaving causes hair to grow back thicker or faster is a common misconception. Shaving does not alter the thickness or growth rate of hair; instead, it leaves a blunt tip, making the hair feel coarser or appear thicker than uncut hair.3 Despite its relative convenience, shaving can lead to skin irritation due to mechanical trauma. Potential complications include PFB, superficial abrasions known more broadly as shaving irritation, and an increased risk for infections such as bacterial or fungal folliculitis.4

Chemical depilation, which uses thioglycolates mixed with alkali compounds, disrupts disulfide bonds in the hair, effectively breaking down the shaft without affecting the bulb. The depilatory requires application to the skin for approximately 3 to 15 minutes depending on the specific formulation and the thickness or texture of the hair. While it is a cost-effective option that easily can be done at home, the chemicals involved may trigger irritant contact dermatitis or folliculitis and produce an unpleasant odor from hydrogen disulfide gas.5 They also can lead to PFB.

Epilation removes the entire hair shaft and bulb, with results lasting approximately 6 weeks.6 Methods range from using tweezers to pluck single hairs and devices that simultaneously remove multiple hairs to hot or cold waxing, which use resin to grip and remove hair. Threading is a technique that uses twisted thread to remove the hair at the follicle level; this method may not alter hair growth unless performed during the anagen phase, during which repeated plucking can damage the matrix and potentially lead to permanent hair reduction.5 Common adverse effects include pain during removal, burns from waxing, folliculitis, PFB, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, and scarring, particularly when multiple hairs are removed at once.

Pharmacologic—Pharmacologic therapy commonly is used to manage hirsutism and typically begins with a trial of combined oral contraceptives (COCs) containing estrogen and progestin, which are considered the first-line option unless contraindicated.7 If response to COC monotherapy is inadequate, an antiandrogen such as spironolactone may be added. Combination therapy with a COC and an antiandrogen generally is reserved for severe cases or patients who previously have shown suboptimal response to COCs alone.7 Patients should be counseled to discontinue antiandrogen therapy if they become pregnant due to the risk for fetal undervirilization observed in animal studies.8,9 Typical dosing of spironolactone, a competitive inhibitor of 5-α-reductase and androgen receptors, ranges from 100 mg to 200 mg daily.10 Reported adverse effects include polyuria, postural hypotension, menstrual irregularities, hyperkalemia, and potential liver dysfunction. Although spironolactone has demonstrated tumorigenic effects in animal studies, no such effects have been observed in humans.11

Eflornithine hydrochloride cream 13.9% is the first topical prescription medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for reduction of unwanted facial hair in women.12 It works by irreversibly blocking the activity of ornithine decarboxylase, an enzyme involved in the rate-limiting step of polyamine synthesis, which is essential for hair growth. In a randomized, double-blind clinical trial evaluating its effectiveness and safety, twice-daily application for 24 weeks resulted in a clinically meaningful reduction in hair length and density (measured as surface area) compared with the control group.13 When eflornithine hydrochloride cream 13.9% is discontinued, hair growth gradually returns to baseline. Studies have shown that hair regrowth typically begins within 8 weeks after treatment is stopped; within several months, hair returns to pretreatment levels.14 Adverse effects of eflornithine hydrochloride cream generally are mild and may include local irritation and acneform eruptions. In a randomized bilateral vehicle-controlled trial of 31 women, both eflornithine and vehicle creams were well tolerated, with 1 patient reporting mild tingling with eflornithine that resolved with continued use for 7 days.15

Procedural—Photoepilation therapies widely are considered by dermatologists to be among the most effective methods for reducing unwanted hair.16 Laser hair removal employs selective photothermolysis, a principle by which specific wavelengths of light target melanin in hair follicles. This method results in localized thermal damage, destroying hair follicles and reducing regrowth. Wavelengths between 600 and 1100 nm are most effective for hair removal; widely used devices include the ruby (694 nm), alexandrite (755 nm), diode (800-810 nm), and long-pulsed Nd:YAG lasers (1064 nm). Cooling mechanisms such as cryogen spray or contact cooling often are employed to minimize epidermal damage and lessen patient discomfort.

The hair matrix is most responsive to laser treatment during the anagen phase, necessitating multiple sessions to ensure all hairs are treated during this optimal growth stage. Generally, 4 to 6 sessions spaced at intervals of 4 to 6 weeks are required to achieve satisfactory results.17 Matching the laser wavelength to the absorption properties of melanin—the target chromophore—enables selective destruction of melanin-rich hair follicles while minimizing damage to surrounding skin.

The ideal laser wavelength primarily affects melanin concentrated in the hair bulb, leading to follicular destruction while reducing the risk for unintended depigmentation of the epidermis; however, competing structures in the skin (eg, epidermal pigment) also can absorb laser energy, diminishing treatment efficacy and increasing the risk for adverse effects. Shorter wavelengths are effective for lighter skin types, while longer wavelengths such as the Nd:YAG laser are safer for individuals with darker skin types as they bypass melanin in the epidermis.

It is important to note that laser hair removal is ineffective for white and gray hairs due to the lack of melanin. As a result, alternative methods such as electrolysis, which does not rely on pigment, may be more appropriate for permanent hair removal in individuals with nonpigmented hairs. Research indicates that combining topical eflornithine with alexandrite or Nd:YAG lasers improves outcomes for reducing unwanted facial hair.18

In military settings, laser hair removal is utilized for specific conditions such as PFB in male service members to assist with the reduction of hair and mitigation of symptoms.19 The majority of military dermatology clinics have devices for laser hair removal; however, dermatology services are not available at many military treatment facilities, and dermatologic care may be provided by the local civilian dermatologists. That said, laser therapy is covered in the civilian sector for active-duty service members with PFB of the face and neck under certain criteria. These include a documented safety risk in environments requiring respiratory protection, failure of conservative treatments, and evaluation by a military dermatologist who confirms the necessity of civilian-provided laser therapy when it is unavailable at a military facility.20 While such policies demonstrate the military’s recognition of laser therapy as a viable solution for certain grooming-related conditions, many are unaware that the existing laser hair removal policy also applies to women. Increasing awareness of this coverage could help female service members access treatment options that align with both medical and professional grooming needs.

Intense pulsed light (IPL) systems are nonlaser devices that emit broad-spectrum light in the 590- to 1200-nm range. They utilize a flash lamp to achieve thermal damage. Filters are used to narrow the wavelength range based on the specific target. Intense pulsed light devices are less precise than lasers but remain effective for hair reduction. In addition to hair removal, IPL devices are employed in the treatment of pigmented and vascular lesions. Common adverse effects of both laser and IPL hair removal include transient erythema, perifollicular edema, and pigmentary changes, especially in patients with darker skin types. Rare complications include blistering, scarring, and paradoxical hair stimulation in which untreated areas develop increased hair growth.

Electrolysis is recognized as the only method of truly permanent hair removal and is effective for all hair colors.21 However, the variability in technique among practitioners often leads to inconsistent results, with some patients experiencing hair regrowth. Galvanic electrolysis involves inserting a fine needle into the hair follicle and applying an electrical current to destroy the it and the rapidly dividing cells of the matrix.22 The introduction of thermolytic electrolysis, which uses a high-frequency alternating current (commonly 13.56 MHz or 27.12 MHz), has enhanced efficiency by creating heat at the needle tip to destroy the follicle. This approach is faster and now is commonly combined with galvanic electrolysis.23 While no controlled clinical trials directly compare these methods, many patients experience permanent hair removal, with approximately 15% to 25% regrowth within 6 months.22,24

Alternative Options—Home-use laser and light-based devices have become increasingly popular for managing unwanted hair due to their affordability and convenience, with most devices priced less than $1000.25 These devices utilize various technologies, including lasers (808 nm), IPL, or combinations of IPL and radiofrequency.26 Despite their accessibility, peer-reviewed research on their safety profile and effectiveness is limited, as existing data primarily come from industry-funded, uncontrolled studies with short follow-up durations—making it difficult to assess long-term outcomes.25

Psychosocial Impact

A 2023 study of active-duty female service members with PCOS highlighted the unique challenges they face while managing symptoms such as facial hair within the constraints of military service.27 Although the study focused on PCOS, the findings shed light on how facial hair specifically impacts the psychological well-being of servicewomen. Participants described facial hair as one of the most visible and stigmatizing symptoms, often leading to feelings of embarrassment and diminished confidence. Participants also highlighted the professional implications of facial hair, with some describing feelings of scrutiny and judgment from peers and leadership in public. These challenges can be more pronounced in deployments or field exercises where hygiene resources are limited. The lack of access not only affects self-perception but also can hinder the ability of servicewomen to meet implicit expectations for grooming and appearance.27 There is a notable gap in research examining the impact of facial hair on military servicewomen. Given the unique environmental challenges and professional expectations, further investigation is warranted to better understand how facial hair affects women and to optimize treatment approaches in this population.

Final Thoughts

Limited awareness and understanding of facial hair in woman contribute to stigma, often leaving affected individuals to navigate challenges in isolation. Given the impact on confidence, professional appearance, and adherence to military grooming standards, it is essential for health care practitioners to recognize and address facial hair in women. Importantly, laser hair removal is covered by TRICARE for active-duty female service members with PFB, yet many remain unaware of this benefit. Increased awareness of available mechanical, pharmacologic, and procedural treatment options allows for tailored management, ensuring that women receive appropriate medical care.

Facial hair growth in women is complex and multifaceted. It is not a disease but rather a part of normal anatomy or a symptom influenced by an underlying condition such as hypertrichosis, a hormonal imbalance (eg, hirsutism due to polycystic ovary syndrome [PCOS]), mechanical factors such as pseudofolliculitis barbae (PFB) from shaving, and perimenopausal and postmenopausal hormonal shifts. Additionally, normal facial hair patterns can vary substantially based on genetics, ethnicity, and cultural background. Some populations may naturally have more visible vellus or terminal hairs on the face, which are entirely physiologic rather than indicative of an underlying disorder. Despite this, societal expectations and beauty standards across many cultures dictate that facial hair in women is undesirable, often associating hair-free skin with femininity and attractiveness. This perception drives many women to seek treatment—not necessarily for medical reasons, but due to social pressure and aesthetic preferences.

Hypertrichosis, whether congenital or acquired, refers to excessive hair growth that is not androgen dependent and can appear on any site of the body. Causes include genetic predisposition, porphyria, thyroid disorders, internal malignancies, malnutrition, anorexia nervosa, or use of medications such as cyclosporine, prednisolone, and phenytoin.1 Hirsutism, by contrast, is characterized by the growth of terminal hairs in women at androgen-dependent sites such as the face, neck, and upper chest, where coarse hair typically grows in men.2 This condition often is associated with excess androgens produced by the ovaries or adrenal glands, most commonly due to PCOS although genetic factors may contribute.

Before initiating treatment, a thorough history and physical examination are essential to determine the underlying cause of conditions associated with facial hair growth in women. Clinicians should assess for signs of hyperandrogenism, menstrual irregularities, virilization, medication use, and family history. In cases of a suspected endocrine disorder, further laboratory evaluation may be warranted to guide appropriate management. While each cause of facial hair growth in women has unique management considerations, the shared impact on psychosocial well-being and adherence to grooming standards in the US military warrants an all-encompassing yet targeted approach. This comprehensive review discusses management options for women with facial hair in the military based on a review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE conducted in November 2024 using combinations of the following search terms: hirsutism, facial hair, pseudofolliculitis barbae, women, female, military, grooming standards, hyperandrogenism, and hair removal.

Treatment Modalities

The available treatment modalities, including their mechanisms, potential risks, and considerations are summarized in the eTable.

Mechanical—Shaving remains one of the most widely utilized methods of hair removal in women due to its accessibility and ease of use. It does not disrupt the anagen phase of the hair growth cycle, making it a temporary method that requires frequent repetition (often daily), particularly for individuals with rapid hair growth. The belief that shaving causes hair to grow back thicker or faster is a common misconception. Shaving does not alter the thickness or growth rate of hair; instead, it leaves a blunt tip, making the hair feel coarser or appear thicker than uncut hair.3 Despite its relative convenience, shaving can lead to skin irritation due to mechanical trauma. Potential complications include PFB, superficial abrasions known more broadly as shaving irritation, and an increased risk for infections such as bacterial or fungal folliculitis.4