User login

You are in the middle of a busy clinic day and think, “there has to be a better way to do this.” Suddenly, a better way to do something becomes obvious. Maybe it’s a tool that simplifies documentation, a device that improves patient comfort, or an app that bridges a clinical gap. Many physicians, especially early career gastroenterologists, have ideas like this, but few know what to do next.

This article is for the curious innovator at the beginning of their clinical career. It offers practical, real-world guidance on developing a clinical product: whether that be hardware, software, or a hybrid. It outlines what questions to ask, who to consult, and how to protect your work, using personal insights and business principles learned through lived experience.

1. Understand Intellectual Property (IP): Know Its Value and Ownership

What is IP?

Intellectual property refers to your original creations: inventions, designs, software, and more. This is what you want to protect legally through patents, trademarks, or copyrights.

Who owns your idea?

This is the first and most important question to ask. If you are employed (especially by a hospital or academic center), your contract may already give your employer rights to any inventions you create, even those developed in your personal time.

What to ask:

- Does my employment contract include an “assignment of inventions” clause?

- Does the institution claim rights to anything developed with institutional resources?

- Are there moonlighting or external activity policies that affect this?

If you are developing an idea on your personal time, with your own resources, and outside your scope of clinical duties, it might still be considered “theirs” under some contracts. Early legal consultation is critical. A specialized IP attorney can help you understand what you own and how to protect it. This should be done early, ideally before you start building anything.

2. Lawyers Aren’t Optional: They’re Essential Early Partners

You do not need a full legal team, but you do need a lawyer early. An early consultation with an IP attorney can clarify your rights, guide your filing process (e.g. provisional patents), and help you avoid costly missteps.

Do this before sharing your idea publicly, including in academic presentations, pitch competitions, or even on social media. Public disclosure can start a clock ticking for application to protect your IP.

3. Build a Founding Team with Intent

Think of your startup team like a long-term relationship: you’re committing to build something together through uncertainty, tension, and change.

Strong early-stage teams often include:

- The Visionary – understands the clinical need and vision

- The Builder – engineer, developer, or designer

- The Doer – project manager or operations lead

Before forming a company, clearly define:

- Ownership (equity percentages)

- Roles and responsibilities

- Time commitments

- What happens if someone exits

Have these discussions early and document your agreements. Avoid informal “handshake” deals that can lead to serious disputes later.

4. You Don’t Need to Know Everything on Day One

You do not need to know how to write code, build a prototype, or get FDA clearance on day one. Successful innovators are humble learners. Use a Minimum Viable Product (MVP), a simple, functional version of your idea, to test assumptions and gather feedback. Iterate based on what you learn. Do not chase perfection; pursue progress. Consider using online accelerators like Y Combinator’s startup school or AGA’s Center for GI Innovation and Technology.

5. Incubators: Use them Strategically

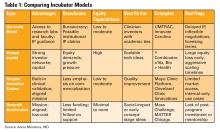

Incubators can offer mentorship, seed funding, legal support, and technical resources, but they vary widely in value (see Table 1). Many may want equity, and not all offer when you truly need.

Ask Yourself:

- Do I need technical help, business mentorship, or just accountability?

- What does this incubator offer in terms of IP protection, exposure, and connections?

- Do I understand the equity trade-off?

- What services and funding do they provide?

- Do they take equity? How much and when?

- What’s their track record with similar ventures?

- Are their incentives aligned with your vision?

6. Academic Institutions: Partners or Pitfalls?

Universities can provide credibility, resources, and early funding through their tech transfer office (TTO).

Key Questions to Ask:

- Will my IP be managed by the TTO?

- How much say do I have in licensing decisions?

- Are there royalty-sharing agreements in place?

- Can I form a startup while employed here?

You may need to negotiate if you want to commercialize your idea independently.

7. Do it for Purpose, Not Payday

Most founders end up owning only a small percentage of their company by the time a product reaches the market. Do not expect to get rich. Do it because it solves a problem you care about. If it happens to come with a nice paycheck, then that is an added bonus.

Your clinical training and insight give you a unique edge. You already know what’s broken. Use that as your compass.

Conclusion

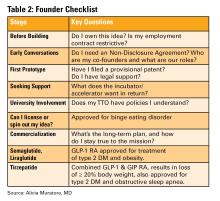

Innovation isn’t about brilliance, it’s about curiosity, structure, and tenacity (see Table 2). Start small. Protect your work. Choose the right partners. Most importantly, stay anchored in your mission to make GI care better.

Dr. Muratore is based at UNC Rex Digestive Health, Raleigh, North Carolina. She has no conflicts related to this article. Dr. Wechsler is based at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina. She holds a patent assigned to Trustees of Dartmouth College. Dr. Shah is based at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan. He consults for Ardelyx, Laborie, Neuraxis, Salix, Sanofi, and Takeda and holds a patent with the Regents of the University of Michigan.

You are in the middle of a busy clinic day and think, “there has to be a better way to do this.” Suddenly, a better way to do something becomes obvious. Maybe it’s a tool that simplifies documentation, a device that improves patient comfort, or an app that bridges a clinical gap. Many physicians, especially early career gastroenterologists, have ideas like this, but few know what to do next.

This article is for the curious innovator at the beginning of their clinical career. It offers practical, real-world guidance on developing a clinical product: whether that be hardware, software, or a hybrid. It outlines what questions to ask, who to consult, and how to protect your work, using personal insights and business principles learned through lived experience.

1. Understand Intellectual Property (IP): Know Its Value and Ownership

What is IP?

Intellectual property refers to your original creations: inventions, designs, software, and more. This is what you want to protect legally through patents, trademarks, or copyrights.

Who owns your idea?

This is the first and most important question to ask. If you are employed (especially by a hospital or academic center), your contract may already give your employer rights to any inventions you create, even those developed in your personal time.

What to ask:

- Does my employment contract include an “assignment of inventions” clause?

- Does the institution claim rights to anything developed with institutional resources?

- Are there moonlighting or external activity policies that affect this?

If you are developing an idea on your personal time, with your own resources, and outside your scope of clinical duties, it might still be considered “theirs” under some contracts. Early legal consultation is critical. A specialized IP attorney can help you understand what you own and how to protect it. This should be done early, ideally before you start building anything.

2. Lawyers Aren’t Optional: They’re Essential Early Partners

You do not need a full legal team, but you do need a lawyer early. An early consultation with an IP attorney can clarify your rights, guide your filing process (e.g. provisional patents), and help you avoid costly missteps.

Do this before sharing your idea publicly, including in academic presentations, pitch competitions, or even on social media. Public disclosure can start a clock ticking for application to protect your IP.

3. Build a Founding Team with Intent

Think of your startup team like a long-term relationship: you’re committing to build something together through uncertainty, tension, and change.

Strong early-stage teams often include:

- The Visionary – understands the clinical need and vision

- The Builder – engineer, developer, or designer

- The Doer – project manager or operations lead

Before forming a company, clearly define:

- Ownership (equity percentages)

- Roles and responsibilities

- Time commitments

- What happens if someone exits

Have these discussions early and document your agreements. Avoid informal “handshake” deals that can lead to serious disputes later.

4. You Don’t Need to Know Everything on Day One

You do not need to know how to write code, build a prototype, or get FDA clearance on day one. Successful innovators are humble learners. Use a Minimum Viable Product (MVP), a simple, functional version of your idea, to test assumptions and gather feedback. Iterate based on what you learn. Do not chase perfection; pursue progress. Consider using online accelerators like Y Combinator’s startup school or AGA’s Center for GI Innovation and Technology.

5. Incubators: Use them Strategically

Incubators can offer mentorship, seed funding, legal support, and technical resources, but they vary widely in value (see Table 1). Many may want equity, and not all offer when you truly need.

Ask Yourself:

- Do I need technical help, business mentorship, or just accountability?

- What does this incubator offer in terms of IP protection, exposure, and connections?

- Do I understand the equity trade-off?

- What services and funding do they provide?

- Do they take equity? How much and when?

- What’s their track record with similar ventures?

- Are their incentives aligned with your vision?

6. Academic Institutions: Partners or Pitfalls?

Universities can provide credibility, resources, and early funding through their tech transfer office (TTO).

Key Questions to Ask:

- Will my IP be managed by the TTO?

- How much say do I have in licensing decisions?

- Are there royalty-sharing agreements in place?

- Can I form a startup while employed here?

You may need to negotiate if you want to commercialize your idea independently.

7. Do it for Purpose, Not Payday

Most founders end up owning only a small percentage of their company by the time a product reaches the market. Do not expect to get rich. Do it because it solves a problem you care about. If it happens to come with a nice paycheck, then that is an added bonus.

Your clinical training and insight give you a unique edge. You already know what’s broken. Use that as your compass.

Conclusion

Innovation isn’t about brilliance, it’s about curiosity, structure, and tenacity (see Table 2). Start small. Protect your work. Choose the right partners. Most importantly, stay anchored in your mission to make GI care better.

Dr. Muratore is based at UNC Rex Digestive Health, Raleigh, North Carolina. She has no conflicts related to this article. Dr. Wechsler is based at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina. She holds a patent assigned to Trustees of Dartmouth College. Dr. Shah is based at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan. He consults for Ardelyx, Laborie, Neuraxis, Salix, Sanofi, and Takeda and holds a patent with the Regents of the University of Michigan.

You are in the middle of a busy clinic day and think, “there has to be a better way to do this.” Suddenly, a better way to do something becomes obvious. Maybe it’s a tool that simplifies documentation, a device that improves patient comfort, or an app that bridges a clinical gap. Many physicians, especially early career gastroenterologists, have ideas like this, but few know what to do next.

This article is for the curious innovator at the beginning of their clinical career. It offers practical, real-world guidance on developing a clinical product: whether that be hardware, software, or a hybrid. It outlines what questions to ask, who to consult, and how to protect your work, using personal insights and business principles learned through lived experience.

1. Understand Intellectual Property (IP): Know Its Value and Ownership

What is IP?

Intellectual property refers to your original creations: inventions, designs, software, and more. This is what you want to protect legally through patents, trademarks, or copyrights.

Who owns your idea?

This is the first and most important question to ask. If you are employed (especially by a hospital or academic center), your contract may already give your employer rights to any inventions you create, even those developed in your personal time.

What to ask:

- Does my employment contract include an “assignment of inventions” clause?

- Does the institution claim rights to anything developed with institutional resources?

- Are there moonlighting or external activity policies that affect this?

If you are developing an idea on your personal time, with your own resources, and outside your scope of clinical duties, it might still be considered “theirs” under some contracts. Early legal consultation is critical. A specialized IP attorney can help you understand what you own and how to protect it. This should be done early, ideally before you start building anything.

2. Lawyers Aren’t Optional: They’re Essential Early Partners

You do not need a full legal team, but you do need a lawyer early. An early consultation with an IP attorney can clarify your rights, guide your filing process (e.g. provisional patents), and help you avoid costly missteps.

Do this before sharing your idea publicly, including in academic presentations, pitch competitions, or even on social media. Public disclosure can start a clock ticking for application to protect your IP.

3. Build a Founding Team with Intent

Think of your startup team like a long-term relationship: you’re committing to build something together through uncertainty, tension, and change.

Strong early-stage teams often include:

- The Visionary – understands the clinical need and vision

- The Builder – engineer, developer, or designer

- The Doer – project manager or operations lead

Before forming a company, clearly define:

- Ownership (equity percentages)

- Roles and responsibilities

- Time commitments

- What happens if someone exits

Have these discussions early and document your agreements. Avoid informal “handshake” deals that can lead to serious disputes later.

4. You Don’t Need to Know Everything on Day One

You do not need to know how to write code, build a prototype, or get FDA clearance on day one. Successful innovators are humble learners. Use a Minimum Viable Product (MVP), a simple, functional version of your idea, to test assumptions and gather feedback. Iterate based on what you learn. Do not chase perfection; pursue progress. Consider using online accelerators like Y Combinator’s startup school or AGA’s Center for GI Innovation and Technology.

5. Incubators: Use them Strategically

Incubators can offer mentorship, seed funding, legal support, and technical resources, but they vary widely in value (see Table 1). Many may want equity, and not all offer when you truly need.

Ask Yourself:

- Do I need technical help, business mentorship, or just accountability?

- What does this incubator offer in terms of IP protection, exposure, and connections?

- Do I understand the equity trade-off?

- What services and funding do they provide?

- Do they take equity? How much and when?

- What’s their track record with similar ventures?

- Are their incentives aligned with your vision?

6. Academic Institutions: Partners or Pitfalls?

Universities can provide credibility, resources, and early funding through their tech transfer office (TTO).

Key Questions to Ask:

- Will my IP be managed by the TTO?

- How much say do I have in licensing decisions?

- Are there royalty-sharing agreements in place?

- Can I form a startup while employed here?

You may need to negotiate if you want to commercialize your idea independently.

7. Do it for Purpose, Not Payday

Most founders end up owning only a small percentage of their company by the time a product reaches the market. Do not expect to get rich. Do it because it solves a problem you care about. If it happens to come with a nice paycheck, then that is an added bonus.

Your clinical training and insight give you a unique edge. You already know what’s broken. Use that as your compass.

Conclusion

Innovation isn’t about brilliance, it’s about curiosity, structure, and tenacity (see Table 2). Start small. Protect your work. Choose the right partners. Most importantly, stay anchored in your mission to make GI care better.

Dr. Muratore is based at UNC Rex Digestive Health, Raleigh, North Carolina. She has no conflicts related to this article. Dr. Wechsler is based at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina. She holds a patent assigned to Trustees of Dartmouth College. Dr. Shah is based at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan. He consults for Ardelyx, Laborie, Neuraxis, Salix, Sanofi, and Takeda and holds a patent with the Regents of the University of Michigan.