User login

‘So You Have an Idea…’: A Practical Guide to Tech and Device Development for the Early Career GI

You are in the middle of a busy clinic day and think, “there has to be a better way to do this.” Suddenly, a better way to do something becomes obvious. Maybe it’s a tool that simplifies documentation, a device that improves patient comfort, or an app that bridges a clinical gap. Many physicians, especially early career gastroenterologists, have ideas like this, but few know what to do next.

This article is for the curious innovator at the beginning of their clinical career. It offers practical, real-world guidance on developing a clinical product: whether that be hardware, software, or a hybrid. It outlines what questions to ask, who to consult, and how to protect your work, using personal insights and business principles learned through lived experience.

1. Understand Intellectual Property (IP): Know Its Value and Ownership

What is IP?

Intellectual property refers to your original creations: inventions, designs, software, and more. This is what you want to protect legally through patents, trademarks, or copyrights.

Who owns your idea?

This is the first and most important question to ask. If you are employed (especially by a hospital or academic center), your contract may already give your employer rights to any inventions you create, even those developed in your personal time.

What to ask:

- Does my employment contract include an “assignment of inventions” clause?

- Does the institution claim rights to anything developed with institutional resources?

- Are there moonlighting or external activity policies that affect this?

If you are developing an idea on your personal time, with your own resources, and outside your scope of clinical duties, it might still be considered “theirs” under some contracts. Early legal consultation is critical. A specialized IP attorney can help you understand what you own and how to protect it. This should be done early, ideally before you start building anything.

2. Lawyers Aren’t Optional: They’re Essential Early Partners

You do not need a full legal team, but you do need a lawyer early. An early consultation with an IP attorney can clarify your rights, guide your filing process (e.g. provisional patents), and help you avoid costly missteps.

Do this before sharing your idea publicly, including in academic presentations, pitch competitions, or even on social media. Public disclosure can start a clock ticking for application to protect your IP.

3. Build a Founding Team with Intent

Think of your startup team like a long-term relationship: you’re committing to build something together through uncertainty, tension, and change.

Strong early-stage teams often include:

- The Visionary – understands the clinical need and vision

- The Builder – engineer, developer, or designer

- The Doer – project manager or operations lead

Before forming a company, clearly define:

- Ownership (equity percentages)

- Roles and responsibilities

- Time commitments

- What happens if someone exits

Have these discussions early and document your agreements. Avoid informal “handshake” deals that can lead to serious disputes later.

4. You Don’t Need to Know Everything on Day One

You do not need to know how to write code, build a prototype, or get FDA clearance on day one. Successful innovators are humble learners. Use a Minimum Viable Product (MVP), a simple, functional version of your idea, to test assumptions and gather feedback. Iterate based on what you learn. Do not chase perfection; pursue progress. Consider using online accelerators like Y Combinator’s startup school or AGA’s Center for GI Innovation and Technology.

5. Incubators: Use them Strategically

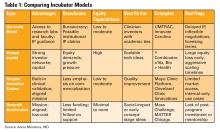

Incubators can offer mentorship, seed funding, legal support, and technical resources, but they vary widely in value (see Table 1). Many may want equity, and not all offer when you truly need.

Ask Yourself:

- Do I need technical help, business mentorship, or just accountability?

- What does this incubator offer in terms of IP protection, exposure, and connections?

- Do I understand the equity trade-off?

- What services and funding do they provide?

- Do they take equity? How much and when?

- What’s their track record with similar ventures?

- Are their incentives aligned with your vision?

6. Academic Institutions: Partners or Pitfalls?

Universities can provide credibility, resources, and early funding through their tech transfer office (TTO).

Key Questions to Ask:

- Will my IP be managed by the TTO?

- How much say do I have in licensing decisions?

- Are there royalty-sharing agreements in place?

- Can I form a startup while employed here?

You may need to negotiate if you want to commercialize your idea independently.

7. Do it for Purpose, Not Payday

Most founders end up owning only a small percentage of their company by the time a product reaches the market. Do not expect to get rich. Do it because it solves a problem you care about. If it happens to come with a nice paycheck, then that is an added bonus.

Your clinical training and insight give you a unique edge. You already know what’s broken. Use that as your compass.

Conclusion

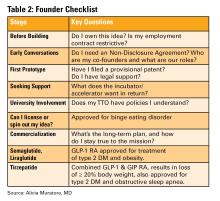

Innovation isn’t about brilliance, it’s about curiosity, structure, and tenacity (see Table 2). Start small. Protect your work. Choose the right partners. Most importantly, stay anchored in your mission to make GI care better.

Dr. Muratore is based at UNC Rex Digestive Health, Raleigh, North Carolina. She has no conflicts related to this article. Dr. Wechsler is based at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina. She holds a patent assigned to Trustees of Dartmouth College. Dr. Shah is based at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan. He consults for Ardelyx, Laborie, Neuraxis, Salix, Sanofi, and Takeda and holds a patent with the Regents of the University of Michigan.

You are in the middle of a busy clinic day and think, “there has to be a better way to do this.” Suddenly, a better way to do something becomes obvious. Maybe it’s a tool that simplifies documentation, a device that improves patient comfort, or an app that bridges a clinical gap. Many physicians, especially early career gastroenterologists, have ideas like this, but few know what to do next.

This article is for the curious innovator at the beginning of their clinical career. It offers practical, real-world guidance on developing a clinical product: whether that be hardware, software, or a hybrid. It outlines what questions to ask, who to consult, and how to protect your work, using personal insights and business principles learned through lived experience.

1. Understand Intellectual Property (IP): Know Its Value and Ownership

What is IP?

Intellectual property refers to your original creations: inventions, designs, software, and more. This is what you want to protect legally through patents, trademarks, or copyrights.

Who owns your idea?

This is the first and most important question to ask. If you are employed (especially by a hospital or academic center), your contract may already give your employer rights to any inventions you create, even those developed in your personal time.

What to ask:

- Does my employment contract include an “assignment of inventions” clause?

- Does the institution claim rights to anything developed with institutional resources?

- Are there moonlighting or external activity policies that affect this?

If you are developing an idea on your personal time, with your own resources, and outside your scope of clinical duties, it might still be considered “theirs” under some contracts. Early legal consultation is critical. A specialized IP attorney can help you understand what you own and how to protect it. This should be done early, ideally before you start building anything.

2. Lawyers Aren’t Optional: They’re Essential Early Partners

You do not need a full legal team, but you do need a lawyer early. An early consultation with an IP attorney can clarify your rights, guide your filing process (e.g. provisional patents), and help you avoid costly missteps.

Do this before sharing your idea publicly, including in academic presentations, pitch competitions, or even on social media. Public disclosure can start a clock ticking for application to protect your IP.

3. Build a Founding Team with Intent

Think of your startup team like a long-term relationship: you’re committing to build something together through uncertainty, tension, and change.

Strong early-stage teams often include:

- The Visionary – understands the clinical need and vision

- The Builder – engineer, developer, or designer

- The Doer – project manager or operations lead

Before forming a company, clearly define:

- Ownership (equity percentages)

- Roles and responsibilities

- Time commitments

- What happens if someone exits

Have these discussions early and document your agreements. Avoid informal “handshake” deals that can lead to serious disputes later.

4. You Don’t Need to Know Everything on Day One

You do not need to know how to write code, build a prototype, or get FDA clearance on day one. Successful innovators are humble learners. Use a Minimum Viable Product (MVP), a simple, functional version of your idea, to test assumptions and gather feedback. Iterate based on what you learn. Do not chase perfection; pursue progress. Consider using online accelerators like Y Combinator’s startup school or AGA’s Center for GI Innovation and Technology.

5. Incubators: Use them Strategically

Incubators can offer mentorship, seed funding, legal support, and technical resources, but they vary widely in value (see Table 1). Many may want equity, and not all offer when you truly need.

Ask Yourself:

- Do I need technical help, business mentorship, or just accountability?

- What does this incubator offer in terms of IP protection, exposure, and connections?

- Do I understand the equity trade-off?

- What services and funding do they provide?

- Do they take equity? How much and when?

- What’s their track record with similar ventures?

- Are their incentives aligned with your vision?

6. Academic Institutions: Partners or Pitfalls?

Universities can provide credibility, resources, and early funding through their tech transfer office (TTO).

Key Questions to Ask:

- Will my IP be managed by the TTO?

- How much say do I have in licensing decisions?

- Are there royalty-sharing agreements in place?

- Can I form a startup while employed here?

You may need to negotiate if you want to commercialize your idea independently.

7. Do it for Purpose, Not Payday

Most founders end up owning only a small percentage of their company by the time a product reaches the market. Do not expect to get rich. Do it because it solves a problem you care about. If it happens to come with a nice paycheck, then that is an added bonus.

Your clinical training and insight give you a unique edge. You already know what’s broken. Use that as your compass.

Conclusion

Innovation isn’t about brilliance, it’s about curiosity, structure, and tenacity (see Table 2). Start small. Protect your work. Choose the right partners. Most importantly, stay anchored in your mission to make GI care better.

Dr. Muratore is based at UNC Rex Digestive Health, Raleigh, North Carolina. She has no conflicts related to this article. Dr. Wechsler is based at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina. She holds a patent assigned to Trustees of Dartmouth College. Dr. Shah is based at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan. He consults for Ardelyx, Laborie, Neuraxis, Salix, Sanofi, and Takeda and holds a patent with the Regents of the University of Michigan.

You are in the middle of a busy clinic day and think, “there has to be a better way to do this.” Suddenly, a better way to do something becomes obvious. Maybe it’s a tool that simplifies documentation, a device that improves patient comfort, or an app that bridges a clinical gap. Many physicians, especially early career gastroenterologists, have ideas like this, but few know what to do next.

This article is for the curious innovator at the beginning of their clinical career. It offers practical, real-world guidance on developing a clinical product: whether that be hardware, software, or a hybrid. It outlines what questions to ask, who to consult, and how to protect your work, using personal insights and business principles learned through lived experience.

1. Understand Intellectual Property (IP): Know Its Value and Ownership

What is IP?

Intellectual property refers to your original creations: inventions, designs, software, and more. This is what you want to protect legally through patents, trademarks, or copyrights.

Who owns your idea?

This is the first and most important question to ask. If you are employed (especially by a hospital or academic center), your contract may already give your employer rights to any inventions you create, even those developed in your personal time.

What to ask:

- Does my employment contract include an “assignment of inventions” clause?

- Does the institution claim rights to anything developed with institutional resources?

- Are there moonlighting or external activity policies that affect this?

If you are developing an idea on your personal time, with your own resources, and outside your scope of clinical duties, it might still be considered “theirs” under some contracts. Early legal consultation is critical. A specialized IP attorney can help you understand what you own and how to protect it. This should be done early, ideally before you start building anything.

2. Lawyers Aren’t Optional: They’re Essential Early Partners

You do not need a full legal team, but you do need a lawyer early. An early consultation with an IP attorney can clarify your rights, guide your filing process (e.g. provisional patents), and help you avoid costly missteps.

Do this before sharing your idea publicly, including in academic presentations, pitch competitions, or even on social media. Public disclosure can start a clock ticking for application to protect your IP.

3. Build a Founding Team with Intent

Think of your startup team like a long-term relationship: you’re committing to build something together through uncertainty, tension, and change.

Strong early-stage teams often include:

- The Visionary – understands the clinical need and vision

- The Builder – engineer, developer, or designer

- The Doer – project manager or operations lead

Before forming a company, clearly define:

- Ownership (equity percentages)

- Roles and responsibilities

- Time commitments

- What happens if someone exits

Have these discussions early and document your agreements. Avoid informal “handshake” deals that can lead to serious disputes later.

4. You Don’t Need to Know Everything on Day One

You do not need to know how to write code, build a prototype, or get FDA clearance on day one. Successful innovators are humble learners. Use a Minimum Viable Product (MVP), a simple, functional version of your idea, to test assumptions and gather feedback. Iterate based on what you learn. Do not chase perfection; pursue progress. Consider using online accelerators like Y Combinator’s startup school or AGA’s Center for GI Innovation and Technology.

5. Incubators: Use them Strategically

Incubators can offer mentorship, seed funding, legal support, and technical resources, but they vary widely in value (see Table 1). Many may want equity, and not all offer when you truly need.

Ask Yourself:

- Do I need technical help, business mentorship, or just accountability?

- What does this incubator offer in terms of IP protection, exposure, and connections?

- Do I understand the equity trade-off?

- What services and funding do they provide?

- Do they take equity? How much and when?

- What’s their track record with similar ventures?

- Are their incentives aligned with your vision?

6. Academic Institutions: Partners or Pitfalls?

Universities can provide credibility, resources, and early funding through their tech transfer office (TTO).

Key Questions to Ask:

- Will my IP be managed by the TTO?

- How much say do I have in licensing decisions?

- Are there royalty-sharing agreements in place?

- Can I form a startup while employed here?

You may need to negotiate if you want to commercialize your idea independently.

7. Do it for Purpose, Not Payday

Most founders end up owning only a small percentage of their company by the time a product reaches the market. Do not expect to get rich. Do it because it solves a problem you care about. If it happens to come with a nice paycheck, then that is an added bonus.

Your clinical training and insight give you a unique edge. You already know what’s broken. Use that as your compass.

Conclusion

Innovation isn’t about brilliance, it’s about curiosity, structure, and tenacity (see Table 2). Start small. Protect your work. Choose the right partners. Most importantly, stay anchored in your mission to make GI care better.

Dr. Muratore is based at UNC Rex Digestive Health, Raleigh, North Carolina. She has no conflicts related to this article. Dr. Wechsler is based at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina. She holds a patent assigned to Trustees of Dartmouth College. Dr. Shah is based at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan. He consults for Ardelyx, Laborie, Neuraxis, Salix, Sanofi, and Takeda and holds a patent with the Regents of the University of Michigan.

My experience with the 2017 Gastroenterology Editorial Fellowship

When I entered the Gastroenterology Editorial Fellowship last year, many of my cofellows asked, “What exactly is an editorial fellowship?” After completing the program, I can now reflect on what was truly a fantastic year-long experience that complemented my final year of fellowship training.

Manuscripts certainly don’t review and accept themselves into journals, and fellowship training usually gives little insight into how manuscripts move through the submission, peer review, and production processes. What happens while authors wait for an editorial decision?

Since its first publication in 1943, Gastroenterology has importantly affected clinical care and the direction of research in our field. The quality of the American Gastroenterological Association’s flagship journal is derived from the sweat and muscle put in daily by gastroenterology-oriented and hepatology-oriented professionals who strive to transform the steady stream of cutting-edge manuscript submissions into an influential monthly publication read by a broad audience of clinicians, trainees, academic researchers, and policy makers. Without a doubt, this fellowship provided me with a sincere appreciation for the dedication that the board of editors puts into the peer review process and into maintaining the quality of monthly publications.

Near the beginning of my editorial fellowship, I spent a week at Vanderbilt University with the on-site editors. This was an irreplaceable opportunity for a trainee like myself to meet with both clinical- and research-oriented academic gastroenterologists who integrate demanding editorial roles into busy and fulfilling professional careers. Throughout my week there, I met with editors and staff who held various roles within the journal. Overall, this experience taught me about what metrics the journal uses to ensure quality, how manuscripts move from submission to publication, and how the direction and content of the journal is directed toward both AGA members and a broader readership.

At its core, the fellowship was focused on teaching the fundamental process of peer review. High-quality reviews for Gastroenterology provide consultative content and methodological expertise to editors who can then provide direction and make editorial recommendations to the authors. During my fellowship, I learned how to write a structured and nuanced review on the basis of novelty, clinical relevance and effects, and methodological rigor. I was paired with one of the associate editors on the basis of my primary content area of interest and regularly provided reviews for original article submissions. As the year progressed, I become more comfortable with reviewing beyond my immediate knowledge base. I also became more adept at providing detailed comments that would be insightful and accessible to both authors and editors.

Each week, I participated in a phone call with the board of editors, which was composed of thought leaders with content expertise in both gastroenterology and hepatology. During the call, we would thoughtfully critique some of the most cutting-edge research in our field; each manuscript often represented the culmination of years of meticulous work by research groups and multinational collaborations. From a fellow’s perspective, these calls gave me access to what may be the most insightful discussions taking place in our field, discussions which could have potential implications on future disease management principles and clinical practice guidelines. Through our meetings, it became apparent how much work goes into finding quality reviewers and how much time goes into assimilating the resulting recommendations into a cohesive discussion. This was an opportunity to learn how associate editors walk the entire board through a manuscript: from a basis of current knowledge and practice, through the conduct and findings of a particular study, and ultimately, to how study findings might affect the field.

What I came away with the most from the Gastroenterology Editorial Fellowship was an appreciation for the importance of the editorial and peer review process in maintaining the integrity and detail needed in high-quality research. Ultimately, this fellowship gave me a meaningful and immediate way to give back to the field that I can continue over the course of my professional career. I am certain that this unique program will continue to give future editorial fellows the skills and motivation they need to become actively involved in the editorial and peer review processes when they are beginning their independent careers.

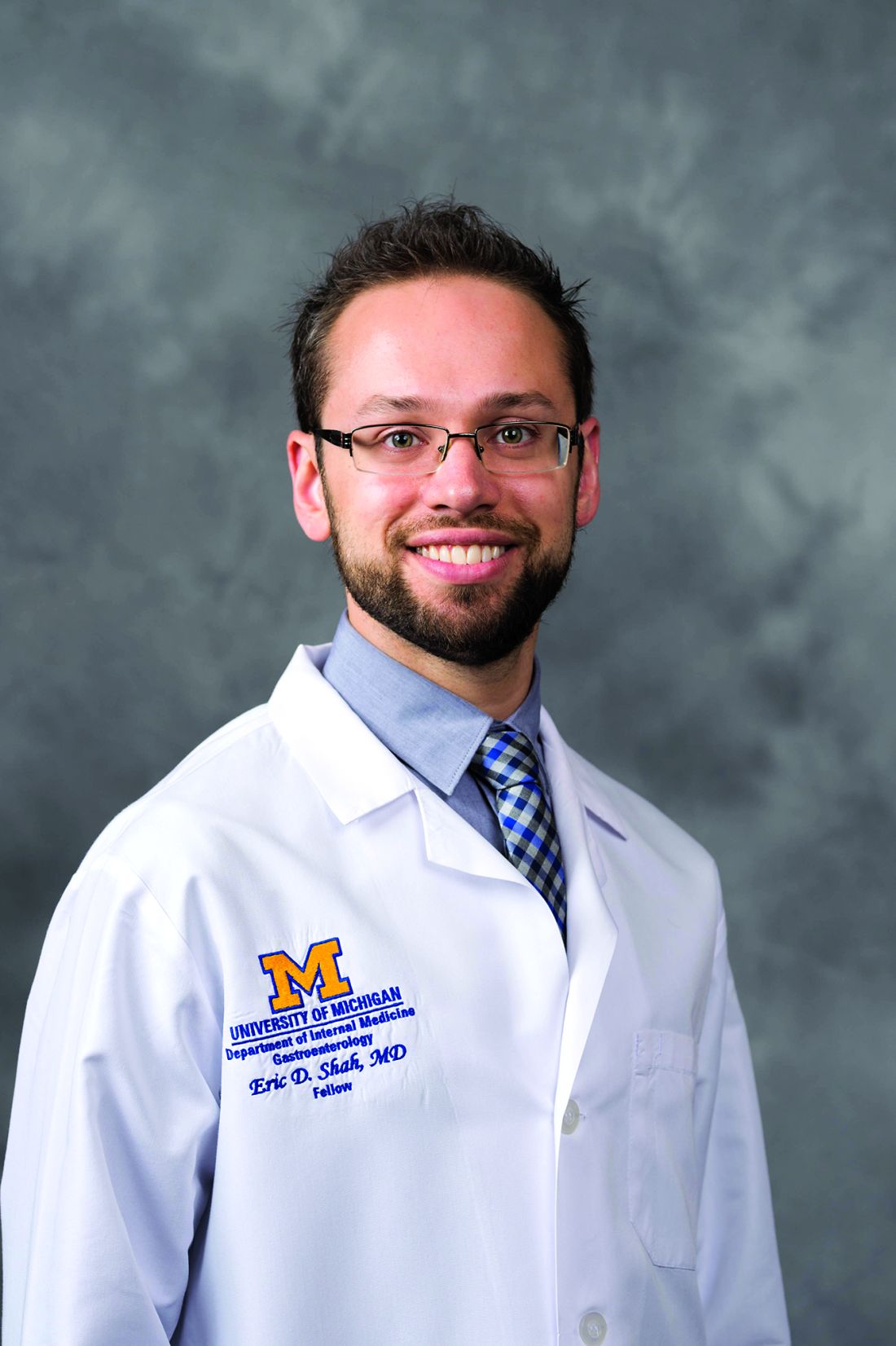

Dr. Shah, MD, MBA, is an assistant professor; he is also the director of the Center for Gastrointestinal Motility in the division of gastroenterology in the department of internal medicine at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H.

When I entered the Gastroenterology Editorial Fellowship last year, many of my cofellows asked, “What exactly is an editorial fellowship?” After completing the program, I can now reflect on what was truly a fantastic year-long experience that complemented my final year of fellowship training.

Manuscripts certainly don’t review and accept themselves into journals, and fellowship training usually gives little insight into how manuscripts move through the submission, peer review, and production processes. What happens while authors wait for an editorial decision?

Since its first publication in 1943, Gastroenterology has importantly affected clinical care and the direction of research in our field. The quality of the American Gastroenterological Association’s flagship journal is derived from the sweat and muscle put in daily by gastroenterology-oriented and hepatology-oriented professionals who strive to transform the steady stream of cutting-edge manuscript submissions into an influential monthly publication read by a broad audience of clinicians, trainees, academic researchers, and policy makers. Without a doubt, this fellowship provided me with a sincere appreciation for the dedication that the board of editors puts into the peer review process and into maintaining the quality of monthly publications.

Near the beginning of my editorial fellowship, I spent a week at Vanderbilt University with the on-site editors. This was an irreplaceable opportunity for a trainee like myself to meet with both clinical- and research-oriented academic gastroenterologists who integrate demanding editorial roles into busy and fulfilling professional careers. Throughout my week there, I met with editors and staff who held various roles within the journal. Overall, this experience taught me about what metrics the journal uses to ensure quality, how manuscripts move from submission to publication, and how the direction and content of the journal is directed toward both AGA members and a broader readership.

At its core, the fellowship was focused on teaching the fundamental process of peer review. High-quality reviews for Gastroenterology provide consultative content and methodological expertise to editors who can then provide direction and make editorial recommendations to the authors. During my fellowship, I learned how to write a structured and nuanced review on the basis of novelty, clinical relevance and effects, and methodological rigor. I was paired with one of the associate editors on the basis of my primary content area of interest and regularly provided reviews for original article submissions. As the year progressed, I become more comfortable with reviewing beyond my immediate knowledge base. I also became more adept at providing detailed comments that would be insightful and accessible to both authors and editors.

Each week, I participated in a phone call with the board of editors, which was composed of thought leaders with content expertise in both gastroenterology and hepatology. During the call, we would thoughtfully critique some of the most cutting-edge research in our field; each manuscript often represented the culmination of years of meticulous work by research groups and multinational collaborations. From a fellow’s perspective, these calls gave me access to what may be the most insightful discussions taking place in our field, discussions which could have potential implications on future disease management principles and clinical practice guidelines. Through our meetings, it became apparent how much work goes into finding quality reviewers and how much time goes into assimilating the resulting recommendations into a cohesive discussion. This was an opportunity to learn how associate editors walk the entire board through a manuscript: from a basis of current knowledge and practice, through the conduct and findings of a particular study, and ultimately, to how study findings might affect the field.

What I came away with the most from the Gastroenterology Editorial Fellowship was an appreciation for the importance of the editorial and peer review process in maintaining the integrity and detail needed in high-quality research. Ultimately, this fellowship gave me a meaningful and immediate way to give back to the field that I can continue over the course of my professional career. I am certain that this unique program will continue to give future editorial fellows the skills and motivation they need to become actively involved in the editorial and peer review processes when they are beginning their independent careers.

Dr. Shah, MD, MBA, is an assistant professor; he is also the director of the Center for Gastrointestinal Motility in the division of gastroenterology in the department of internal medicine at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H.

When I entered the Gastroenterology Editorial Fellowship last year, many of my cofellows asked, “What exactly is an editorial fellowship?” After completing the program, I can now reflect on what was truly a fantastic year-long experience that complemented my final year of fellowship training.

Manuscripts certainly don’t review and accept themselves into journals, and fellowship training usually gives little insight into how manuscripts move through the submission, peer review, and production processes. What happens while authors wait for an editorial decision?

Since its first publication in 1943, Gastroenterology has importantly affected clinical care and the direction of research in our field. The quality of the American Gastroenterological Association’s flagship journal is derived from the sweat and muscle put in daily by gastroenterology-oriented and hepatology-oriented professionals who strive to transform the steady stream of cutting-edge manuscript submissions into an influential monthly publication read by a broad audience of clinicians, trainees, academic researchers, and policy makers. Without a doubt, this fellowship provided me with a sincere appreciation for the dedication that the board of editors puts into the peer review process and into maintaining the quality of monthly publications.

Near the beginning of my editorial fellowship, I spent a week at Vanderbilt University with the on-site editors. This was an irreplaceable opportunity for a trainee like myself to meet with both clinical- and research-oriented academic gastroenterologists who integrate demanding editorial roles into busy and fulfilling professional careers. Throughout my week there, I met with editors and staff who held various roles within the journal. Overall, this experience taught me about what metrics the journal uses to ensure quality, how manuscripts move from submission to publication, and how the direction and content of the journal is directed toward both AGA members and a broader readership.

At its core, the fellowship was focused on teaching the fundamental process of peer review. High-quality reviews for Gastroenterology provide consultative content and methodological expertise to editors who can then provide direction and make editorial recommendations to the authors. During my fellowship, I learned how to write a structured and nuanced review on the basis of novelty, clinical relevance and effects, and methodological rigor. I was paired with one of the associate editors on the basis of my primary content area of interest and regularly provided reviews for original article submissions. As the year progressed, I become more comfortable with reviewing beyond my immediate knowledge base. I also became more adept at providing detailed comments that would be insightful and accessible to both authors and editors.

Each week, I participated in a phone call with the board of editors, which was composed of thought leaders with content expertise in both gastroenterology and hepatology. During the call, we would thoughtfully critique some of the most cutting-edge research in our field; each manuscript often represented the culmination of years of meticulous work by research groups and multinational collaborations. From a fellow’s perspective, these calls gave me access to what may be the most insightful discussions taking place in our field, discussions which could have potential implications on future disease management principles and clinical practice guidelines. Through our meetings, it became apparent how much work goes into finding quality reviewers and how much time goes into assimilating the resulting recommendations into a cohesive discussion. This was an opportunity to learn how associate editors walk the entire board through a manuscript: from a basis of current knowledge and practice, through the conduct and findings of a particular study, and ultimately, to how study findings might affect the field.

What I came away with the most from the Gastroenterology Editorial Fellowship was an appreciation for the importance of the editorial and peer review process in maintaining the integrity and detail needed in high-quality research. Ultimately, this fellowship gave me a meaningful and immediate way to give back to the field that I can continue over the course of my professional career. I am certain that this unique program will continue to give future editorial fellows the skills and motivation they need to become actively involved in the editorial and peer review processes when they are beginning their independent careers.

Dr. Shah, MD, MBA, is an assistant professor; he is also the director of the Center for Gastrointestinal Motility in the division of gastroenterology in the department of internal medicine at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H.