User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Pediatric Photosensitivity Disorders

Review the PDF of the fact sheet on pediatric photosensitivity disorders with board-relevant, easy-to-review material. This month's fact sheet will review important disorders in the pediatric population where photosensitivity is a major feature

Practice Questions

1. Which photosensitivity disorder is characterized by decreased immunoglobulin-mediated immunity?

a. Bloom syndrome

b. Cockayne syndrome

c. hydroa vacciniforme

d. Kindler syndrome

e. poikiloderma congenitale

2. Which of the following is an inappropriate treatment for a young Mexican girl with cheilitis and treatment-resistant chronic pruritic crusted papules and scars on both sun-exposed and nonexposed sites?

a. oral isotretinoin

b. oral prednisone

c. oral thalidomide

d. topical calcineurin inhibitors

e. topical corticosteroids

3. Which gene is mutated in a patient with a history of congenital acral blistering and then gradual onset of cutaneous atrophy and fragility, oral lesions, and photosensitivity?

a. DHCR7

b. KIND1

c. RECQL4

d. SLC6A19

e. XPD

4. Which photosensitivity disorder is associated with an increased risk for osteosarcoma?

a. actinic prurigo

b. Rothmund-Thomson syndrome

c. Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome

d. trichothiodystrophy

e. xeroderma pigmentosum

5. All of the following are features seen in De Sanctis-Cacchione syndrome except:

a. ataxia

b. basal ganglion calcification

c. deafness

d. hypogonadism

e. short stature

Answers to practice questions provided on next page

Practice Question Answers

1. Which photosensitivity disorder is characterized by decreased immunoglobulin-mediated immunity?

a. Bloom syndrome

b. Cockayne syndrome

c. hydroa vacciniforme

d. Kindler syndrome

e. poikiloderma congenitale

2. Which of the following is an inappropriate treatment for a young Mexican girl with cheilitis and treatment-resistant chronic pruritic crusted papules and scars on both sun-exposed and nonexposed sites?

a. oral isotretinoin

b. oral prednisone

c. oral thalidomide

d. topical calcineurin inhibitors

e. topical corticosteroids

3. Which gene is mutated in a patient with a history of congenital acral blistering and then gradual onset of cutaneous atrophy and fragility, oral lesions, and photosensitivity?

a. DHCR7

b. KIND1

c. RECQL4

d. SLC6A19

e. XPD

4. Which photosensitivity disorder is associated with an increased risk for osteosarcoma?

a. actinic prurigo

b. Rothmund-Thomson syndrome

c. Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome

d. trichothiodystrophy

e. xeroderma pigmentosum

5. All of the following are features seen in De Sanctis-Cacchione syndrome except:

a. ataxia

b. basal ganglion calcification

c. deafness

d. hypogonadism

e. short stature

Review the PDF of the fact sheet on pediatric photosensitivity disorders with board-relevant, easy-to-review material. This month's fact sheet will review important disorders in the pediatric population where photosensitivity is a major feature

Practice Questions

1. Which photosensitivity disorder is characterized by decreased immunoglobulin-mediated immunity?

a. Bloom syndrome

b. Cockayne syndrome

c. hydroa vacciniforme

d. Kindler syndrome

e. poikiloderma congenitale

2. Which of the following is an inappropriate treatment for a young Mexican girl with cheilitis and treatment-resistant chronic pruritic crusted papules and scars on both sun-exposed and nonexposed sites?

a. oral isotretinoin

b. oral prednisone

c. oral thalidomide

d. topical calcineurin inhibitors

e. topical corticosteroids

3. Which gene is mutated in a patient with a history of congenital acral blistering and then gradual onset of cutaneous atrophy and fragility, oral lesions, and photosensitivity?

a. DHCR7

b. KIND1

c. RECQL4

d. SLC6A19

e. XPD

4. Which photosensitivity disorder is associated with an increased risk for osteosarcoma?

a. actinic prurigo

b. Rothmund-Thomson syndrome

c. Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome

d. trichothiodystrophy

e. xeroderma pigmentosum

5. All of the following are features seen in De Sanctis-Cacchione syndrome except:

a. ataxia

b. basal ganglion calcification

c. deafness

d. hypogonadism

e. short stature

Answers to practice questions provided on next page

Practice Question Answers

1. Which photosensitivity disorder is characterized by decreased immunoglobulin-mediated immunity?

a. Bloom syndrome

b. Cockayne syndrome

c. hydroa vacciniforme

d. Kindler syndrome

e. poikiloderma congenitale

2. Which of the following is an inappropriate treatment for a young Mexican girl with cheilitis and treatment-resistant chronic pruritic crusted papules and scars on both sun-exposed and nonexposed sites?

a. oral isotretinoin

b. oral prednisone

c. oral thalidomide

d. topical calcineurin inhibitors

e. topical corticosteroids

3. Which gene is mutated in a patient with a history of congenital acral blistering and then gradual onset of cutaneous atrophy and fragility, oral lesions, and photosensitivity?

a. DHCR7

b. KIND1

c. RECQL4

d. SLC6A19

e. XPD

4. Which photosensitivity disorder is associated with an increased risk for osteosarcoma?

a. actinic prurigo

b. Rothmund-Thomson syndrome

c. Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome

d. trichothiodystrophy

e. xeroderma pigmentosum

5. All of the following are features seen in De Sanctis-Cacchione syndrome except:

a. ataxia

b. basal ganglion calcification

c. deafness

d. hypogonadism

e. short stature

Review the PDF of the fact sheet on pediatric photosensitivity disorders with board-relevant, easy-to-review material. This month's fact sheet will review important disorders in the pediatric population where photosensitivity is a major feature

Practice Questions

1. Which photosensitivity disorder is characterized by decreased immunoglobulin-mediated immunity?

a. Bloom syndrome

b. Cockayne syndrome

c. hydroa vacciniforme

d. Kindler syndrome

e. poikiloderma congenitale

2. Which of the following is an inappropriate treatment for a young Mexican girl with cheilitis and treatment-resistant chronic pruritic crusted papules and scars on both sun-exposed and nonexposed sites?

a. oral isotretinoin

b. oral prednisone

c. oral thalidomide

d. topical calcineurin inhibitors

e. topical corticosteroids

3. Which gene is mutated in a patient with a history of congenital acral blistering and then gradual onset of cutaneous atrophy and fragility, oral lesions, and photosensitivity?

a. DHCR7

b. KIND1

c. RECQL4

d. SLC6A19

e. XPD

4. Which photosensitivity disorder is associated with an increased risk for osteosarcoma?

a. actinic prurigo

b. Rothmund-Thomson syndrome

c. Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome

d. trichothiodystrophy

e. xeroderma pigmentosum

5. All of the following are features seen in De Sanctis-Cacchione syndrome except:

a. ataxia

b. basal ganglion calcification

c. deafness

d. hypogonadism

e. short stature

Answers to practice questions provided on next page

Practice Question Answers

1. Which photosensitivity disorder is characterized by decreased immunoglobulin-mediated immunity?

a. Bloom syndrome

b. Cockayne syndrome

c. hydroa vacciniforme

d. Kindler syndrome

e. poikiloderma congenitale

2. Which of the following is an inappropriate treatment for a young Mexican girl with cheilitis and treatment-resistant chronic pruritic crusted papules and scars on both sun-exposed and nonexposed sites?

a. oral isotretinoin

b. oral prednisone

c. oral thalidomide

d. topical calcineurin inhibitors

e. topical corticosteroids

3. Which gene is mutated in a patient with a history of congenital acral blistering and then gradual onset of cutaneous atrophy and fragility, oral lesions, and photosensitivity?

a. DHCR7

b. KIND1

c. RECQL4

d. SLC6A19

e. XPD

4. Which photosensitivity disorder is associated with an increased risk for osteosarcoma?

a. actinic prurigo

b. Rothmund-Thomson syndrome

c. Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome

d. trichothiodystrophy

e. xeroderma pigmentosum

5. All of the following are features seen in De Sanctis-Cacchione syndrome except:

a. ataxia

b. basal ganglion calcification

c. deafness

d. hypogonadism

e. short stature

New Digital Editor Appointed for Cutis®

We are pleased to announce that Gary Goldenberg, MD, has been named Digital Editor of Cutis. In this new role, Dr. Goldenberg will work closely with our Editorial Board and editorial/publishing staff on our website, www.cutis.com. Dr. Goldenberg is Assistant Clinical Professor of Dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, New York, and Medical Director of the Dermatology Faculty Practice at The Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York. Dr. Goldenberg has been a member of the Cutis Editorial Board since April 2008 due to his expertise in dermatopathology as well as medical and cosmetic dermatology. Over the years, Dr. Goldenberg’s involvement in the journal’s presence in print and online has expanded to include a regular series of Cosmetic Dermatology articles and video commentaries on practice management topics. With Dr. Goldenberg’s oversight, we will expand our offerings of highly practical content in the digital arena with an emphasis on resources for the practicing dermatologist.

“We welcome Gary as our first Digital Editor of Cutis and thank him for agreeing to lead us into the future,” said Cutis Editor-in-Chief Vincent A. DeLeo, MD. “Cutis has been a leader in print readership among dermatologists and with Gary’s input, we will be able to offer more to our readers online.”

We are pleased to announce that Gary Goldenberg, MD, has been named Digital Editor of Cutis. In this new role, Dr. Goldenberg will work closely with our Editorial Board and editorial/publishing staff on our website, www.cutis.com. Dr. Goldenberg is Assistant Clinical Professor of Dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, New York, and Medical Director of the Dermatology Faculty Practice at The Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York. Dr. Goldenberg has been a member of the Cutis Editorial Board since April 2008 due to his expertise in dermatopathology as well as medical and cosmetic dermatology. Over the years, Dr. Goldenberg’s involvement in the journal’s presence in print and online has expanded to include a regular series of Cosmetic Dermatology articles and video commentaries on practice management topics. With Dr. Goldenberg’s oversight, we will expand our offerings of highly practical content in the digital arena with an emphasis on resources for the practicing dermatologist.

“We welcome Gary as our first Digital Editor of Cutis and thank him for agreeing to lead us into the future,” said Cutis Editor-in-Chief Vincent A. DeLeo, MD. “Cutis has been a leader in print readership among dermatologists and with Gary’s input, we will be able to offer more to our readers online.”

We are pleased to announce that Gary Goldenberg, MD, has been named Digital Editor of Cutis. In this new role, Dr. Goldenberg will work closely with our Editorial Board and editorial/publishing staff on our website, www.cutis.com. Dr. Goldenberg is Assistant Clinical Professor of Dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, New York, and Medical Director of the Dermatology Faculty Practice at The Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York. Dr. Goldenberg has been a member of the Cutis Editorial Board since April 2008 due to his expertise in dermatopathology as well as medical and cosmetic dermatology. Over the years, Dr. Goldenberg’s involvement in the journal’s presence in print and online has expanded to include a regular series of Cosmetic Dermatology articles and video commentaries on practice management topics. With Dr. Goldenberg’s oversight, we will expand our offerings of highly practical content in the digital arena with an emphasis on resources for the practicing dermatologist.

“We welcome Gary as our first Digital Editor of Cutis and thank him for agreeing to lead us into the future,” said Cutis Editor-in-Chief Vincent A. DeLeo, MD. “Cutis has been a leader in print readership among dermatologists and with Gary’s input, we will be able to offer more to our readers online.”

Tuberculous Cellulitis: Diseases Behind Cellulitislike Erythema

Local tender erythema is a typical manifestation of cellulitis, which is commonly seen by dermatologists; however, cutaneous manifestations of other diseases may bear resemblance to the more banal cellulitis. We present the case of a patient with tuberculous cellulitis, a rare variant of cutaneous tuberculosis.

Case Report

An 89-year-old man presented to a local primary care physician with a fever (temperature, 38°C). Infectious disease was suspected. Antibiotic therapy with oral cefaclor and intravenous cefotiam hydrochloride was started, but the patient’s fever did not subside. Six days after initiation of treatment, he was referred to our dermatology department for evaluation of a painful erythematous rash on the left thigh that had suddenly appeared. The patient had a history of pulmonary tuberculosis 71 years prior. He also underwent surgical treatment of pancreatic cancer 14 years prior. Additionally, he had chronic kidney disease (CKD) and polymyalgia rheumatica, which was currently being treated with oral prednisolone 5 mg once daily.

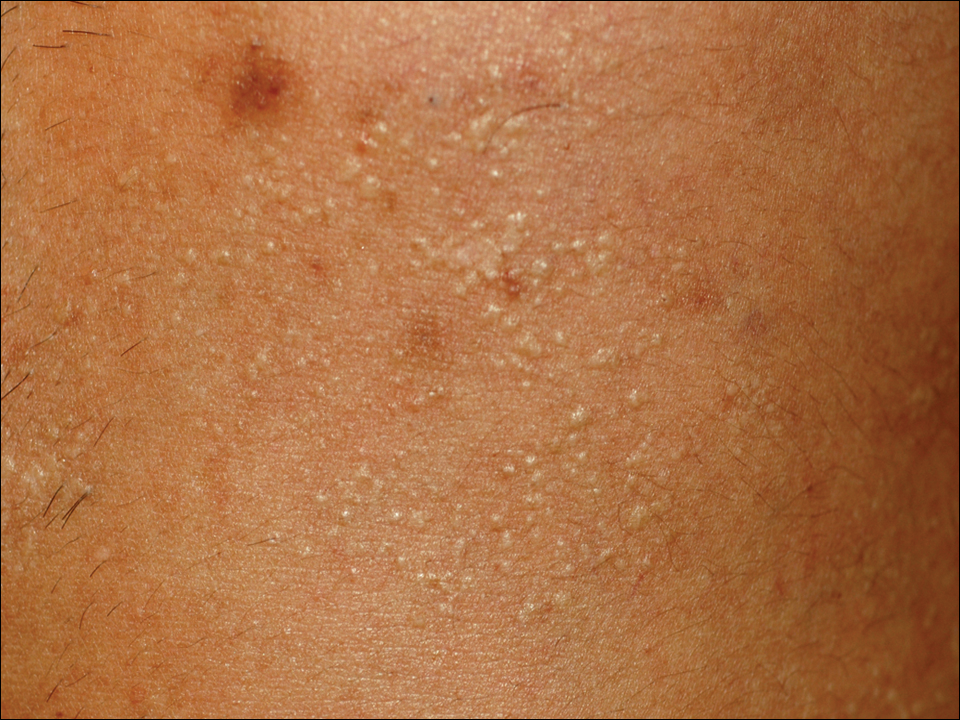

Physical examination revealed a hot and tender erythematous plaque on the left thigh (Figure 1). The edge of the lesion was not well defined and there was no regional lymphadenopathy.

A complete blood cell count revealed anemia (white blood cell count, 8070/μL [reference range, 4000–9,000/μL]; neutrophils, 77.1% [reference range, 44%–74%]; lymphocytes, 13.8% [reference range, 20%–50%]; hemoglobin, 9.3 g/dL [reference range, 13.0–17.0 g/dL]; and platelet count, 329×103/μL [reference range, 150–400×103/μL]). The C-reactive protein level was 7.3 mg/dL (reference range, 0.08–0.3 mg/dL). The creatinine level was 2.93 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6–1.2 mg/dL). There were no signs of liver dysfunction.

A blood culture was negative. A purified protein derivative (tuberculin) skin test was negative (6×7 mm [reference range, ≤9 mm). A chest computed tomography (CT) scan showed small centrilobular nodules that had not changed in number or size since evaluation 3 months prior.

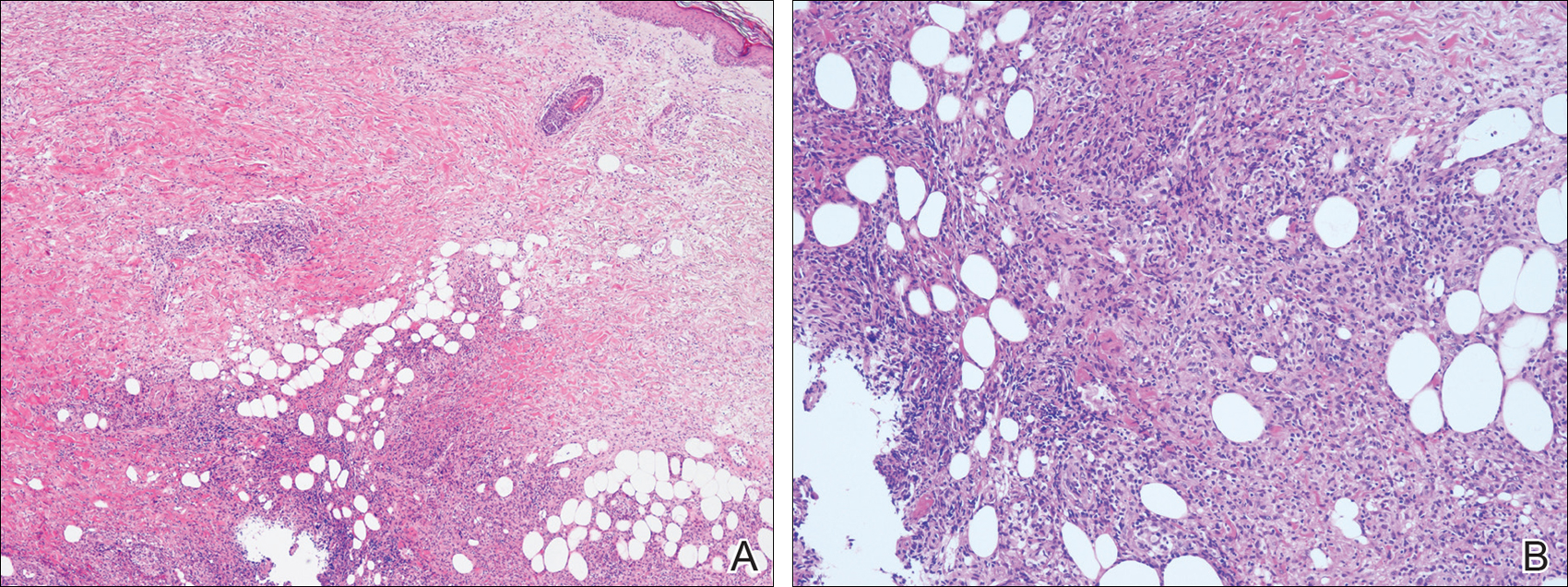

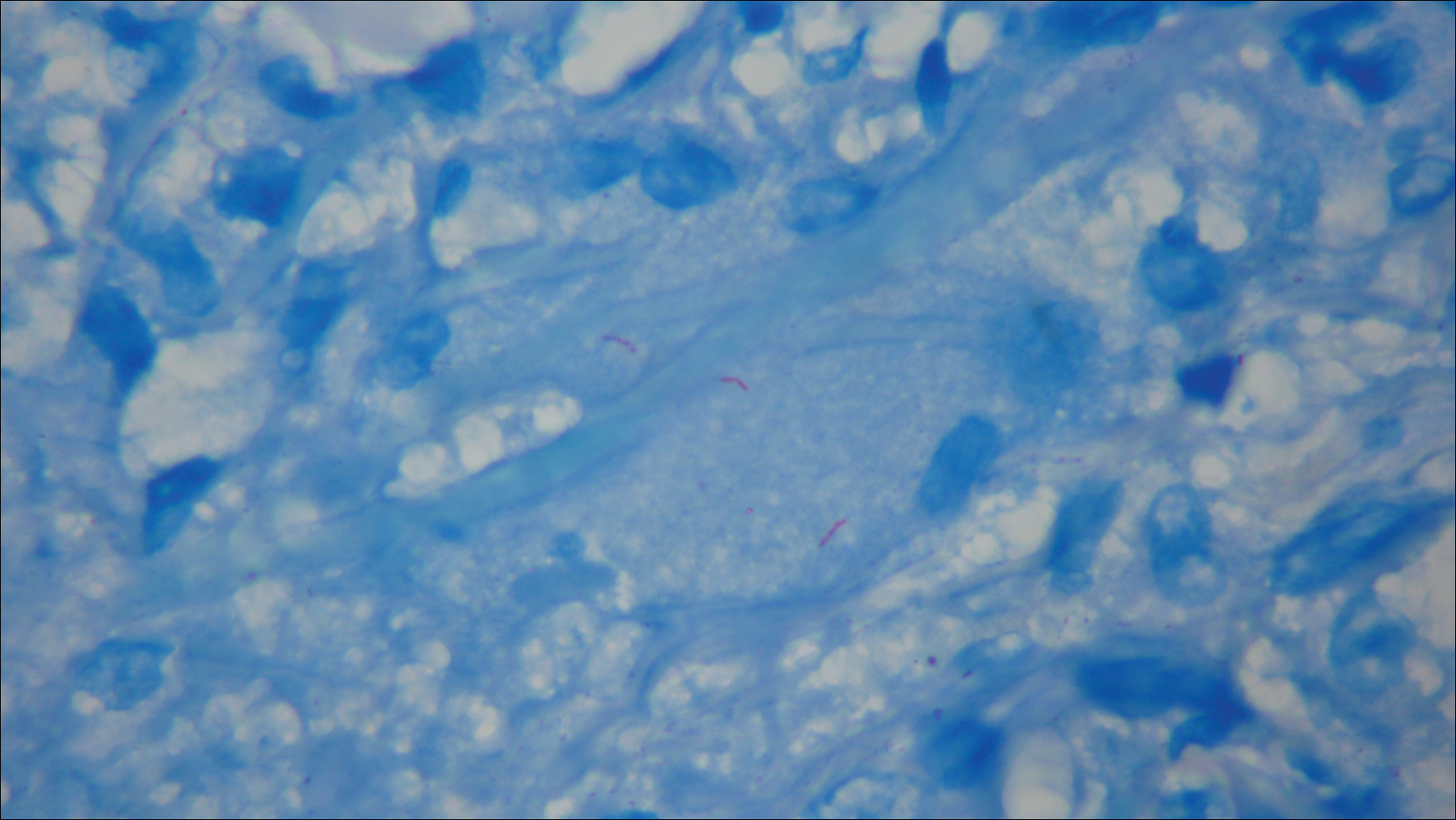

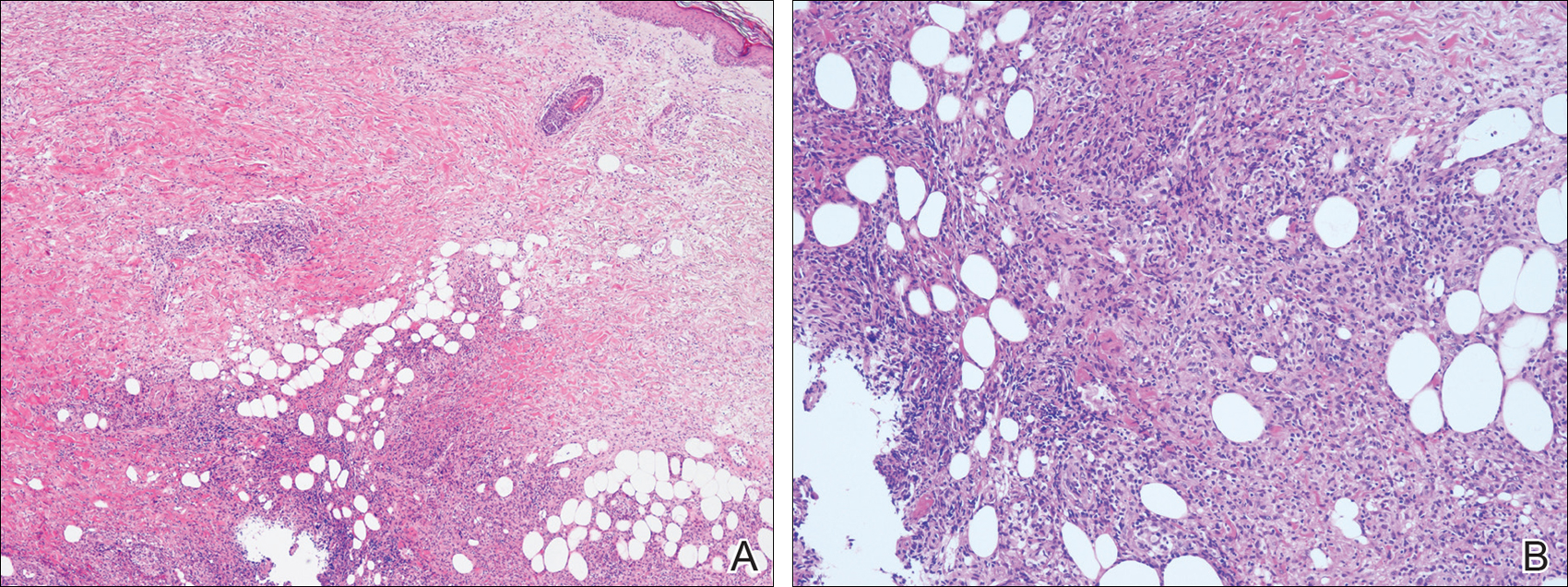

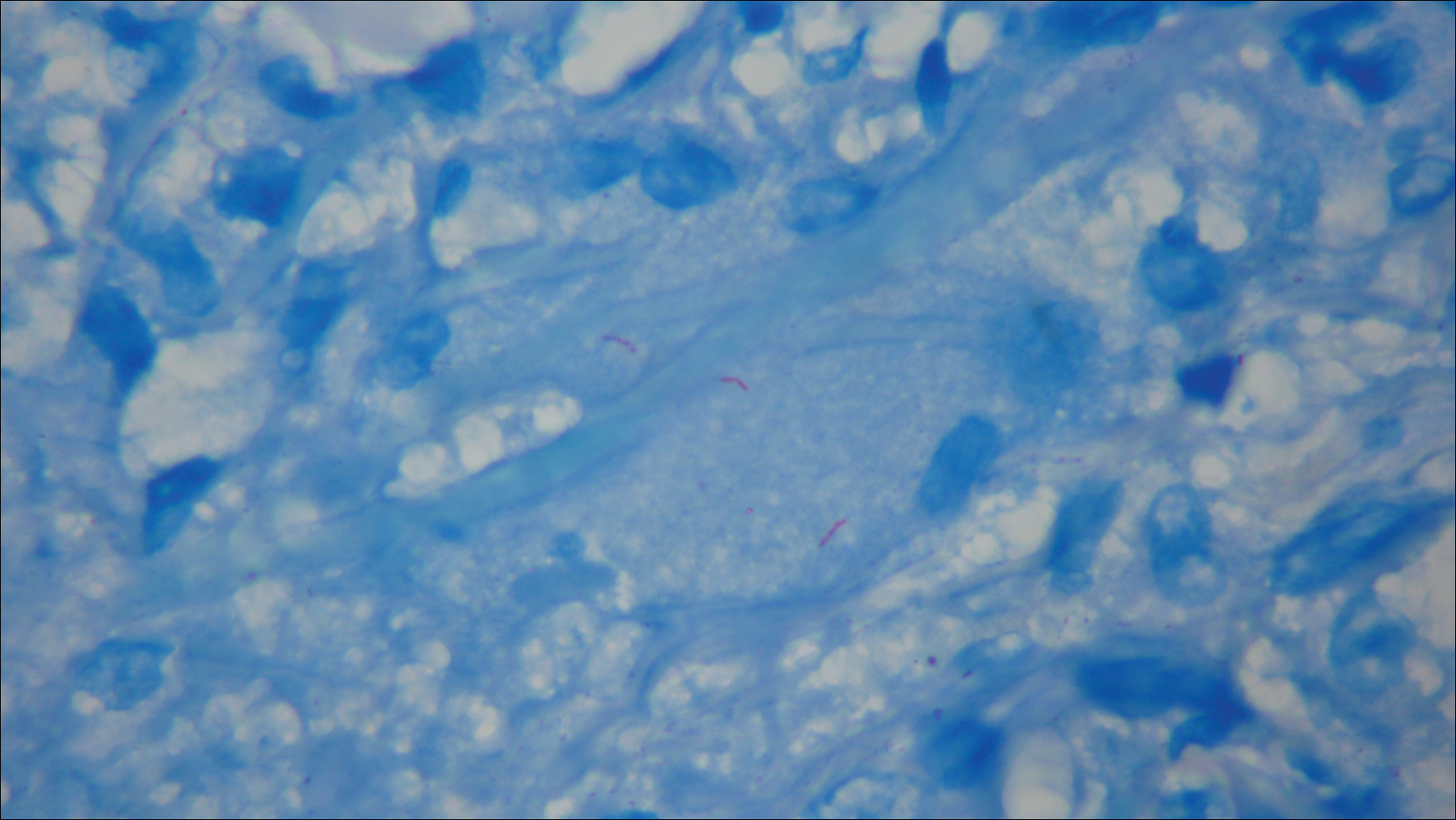

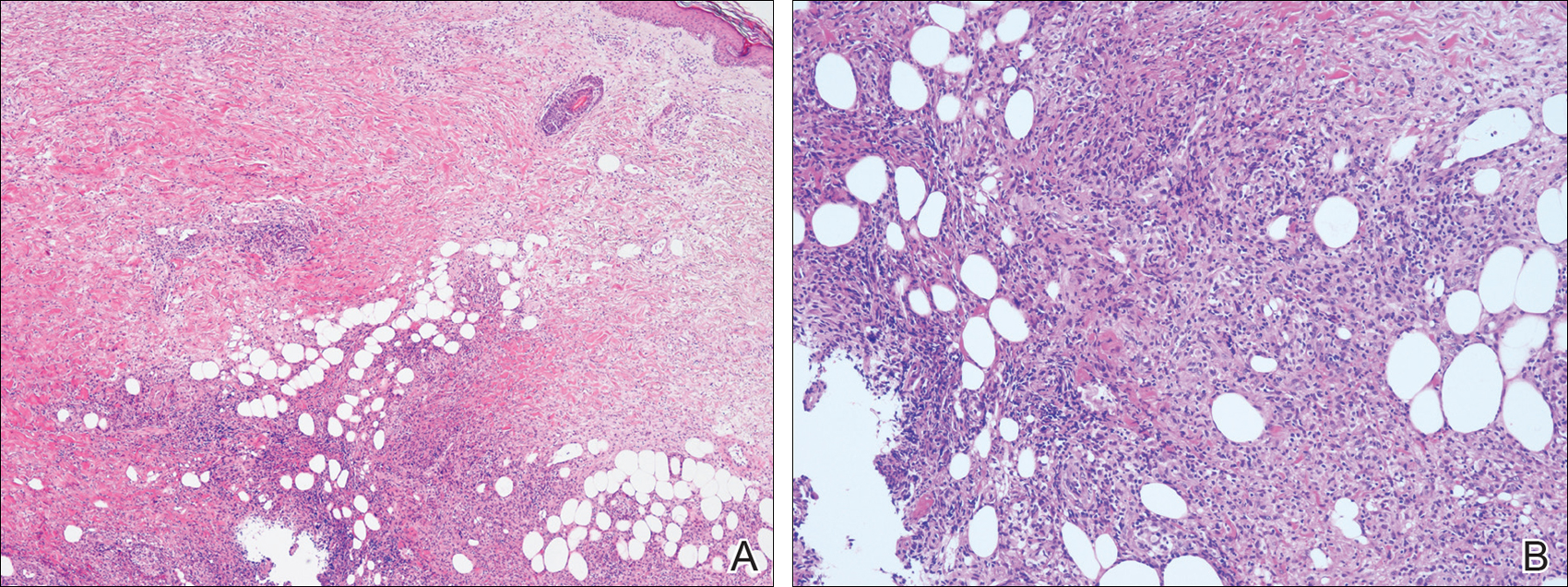

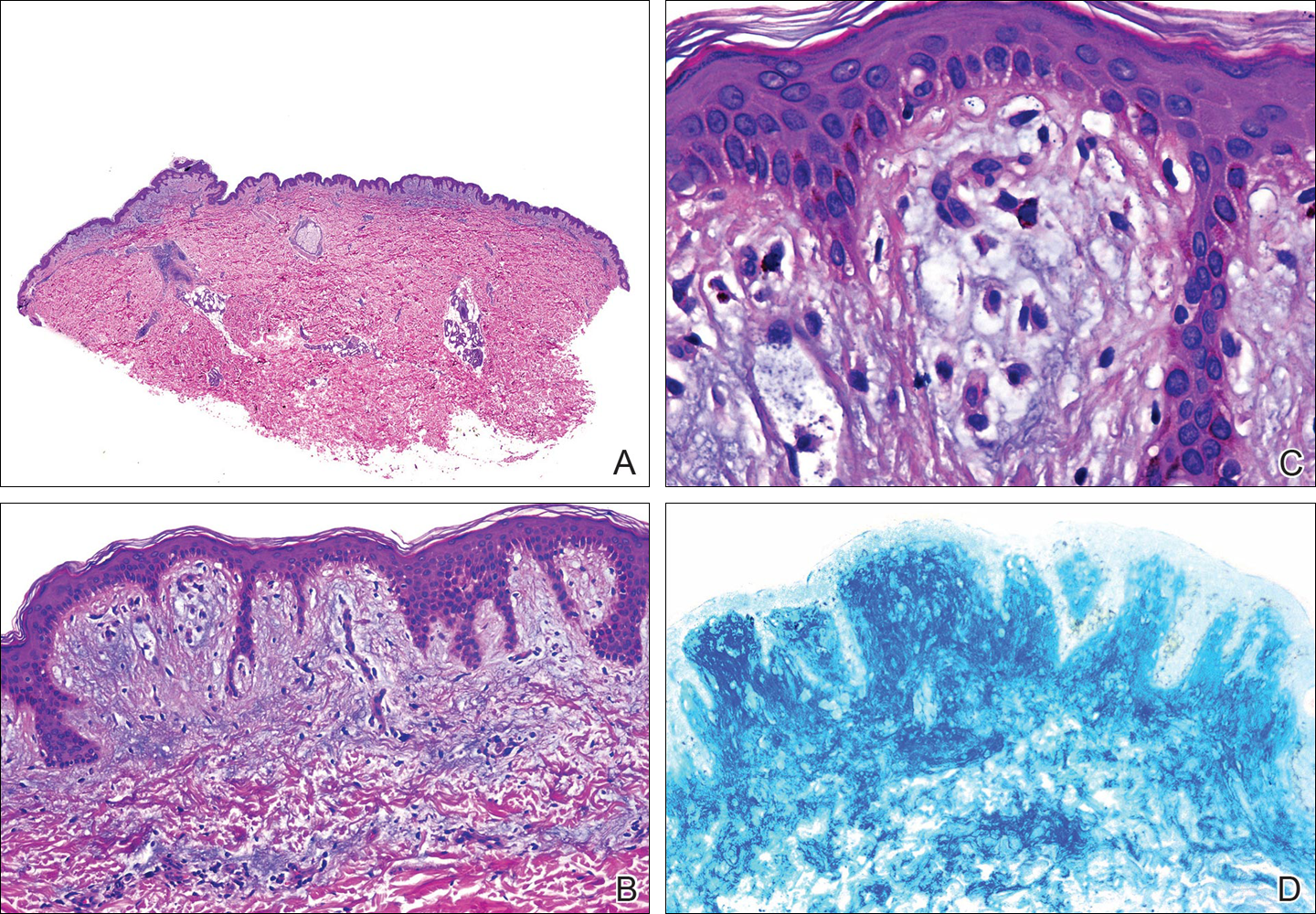

The antibiotics were changed to meropenem hydrate 0.5 g and clindamycin 300 mg twice daily for presumed bacterial cellulitis, then meropenem hydrate 1 g and clindamycin 600 mg daily, but there was still no improvement after about 1 week. Therefore, a skin biopsy was performed on the left thigh. The specimen showed epithelioid cell granulomas throughout the dermis and subcutis (Figure 2). Ziehl-Neelsen stain revealed numerous acid-fast bacilli (Figure 3). Polymerase chain reaction was positive for Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the skin biopsy specimen and gastric fluid. Additionally, M tuberculosis was isolated from the skin biopsy specimen, gastric fluid, and sputum culture. After the series of treatments described above, a remarkable increase in nodule size and number was observed in a follow-up chest CT scan compared with the prior examination. These pulmonary lesions showed bronchogenic spread.

A diagnosis of tuberculous cellulitis with pulmonary tuberculosis was made. Treatment with isoniazid 200 mg once daily, rifampin 300 mg once daily, and ethambutol 500 mg once every other day was started; the dosages were reduced from the standard dose due to the patient’s CKD.1 Four days after initiation of these medications, the patient was transferred to a hospital specifically for the treatment of tuberculosis. Approximately 8 months after treatment with isoniazid, rifampin, and ethambutol, M tuberculosis could not be detected in the sputum and a chest CT revealed that the pulmonary lesions were remarkably improved. However, polymerase chain reaction of the skin biopsy specimen was still positive for M tuberculosis. It was determined that debridement of the skin lesion was needed, but the patient died from complications of deteriorating CKD 10 months after the initiation of the antituberculosis medications.

Comment

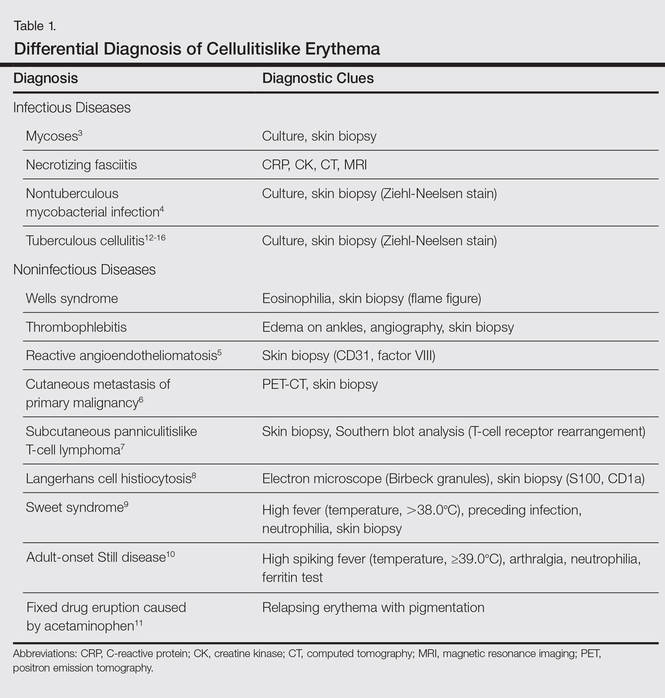

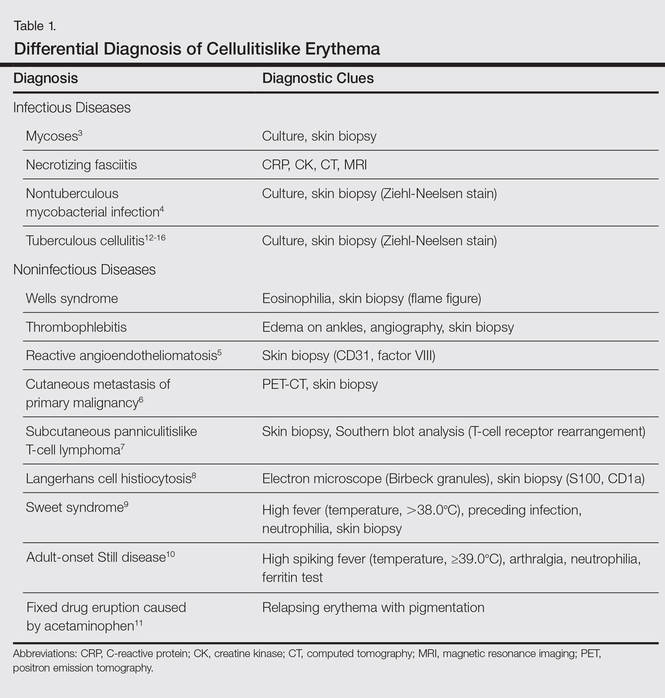

Cellulitis is a suppurative inflammation involving the subcutis.2 Local tender erythema, malaise, chills, and fever may be present at the onset. Cellulitis is commonly seen by dermatologists, and it is well known that other infectious diseases such as necrotizing fasciitis, cutaneous and subcutaneous mycoses,3 and nontuberculous mycobacterial infections4 sometimes present as cellulitislike skin lesions. Moreover, noninfectious diseases, such as Wells syndrome, thrombophlebitis, reactive angioendotheliomatosis,5 cutaneous metastasis of a primary malignancy,6 subcutaneous panniculitislike T-cell lymphoma,7 Langerhans cell histiocytosis,8 Sweet syndrome,9 adult-onset Still disease,10 and fixed drug eruption caused by acetaminophen11 should be excluded. These differential diagnoses and diagnostic clues of cellulitislike erythema are summarized in Table 1.3-16

Cutaneous tuberculosis presenting as cellulitis, so-called tuberculous cellulitis, also is characterized as a clinical mimicker of cellulitis. On the other hand, histologically, it has features of cutaneous tuberculosis (eg, necrotic granuloma).12,14,15 Tuberculous cellulitis is rare and therefore may often be misdiagnosed even in highly endemic areas. We summarized the clinical information of 5 well-documented cases of tuberculous cellulitis along with the current case in Table 2.12-16 All of these cases had an associated disease and involved patients who were currently taking oral corticosteroids. If a patient undergoing immunosuppressive therapy develops cellulitislike erythema, tuberculous cellulitis should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Cutaneous tuberculosis generally is classified into 4 types according to the mechanism of disease acquisition: (1) inoculation from an exogenous source, (2) endogenous cutaneous spread contiguously or by autoinoculation, (3) hematogenous spread to the skin, and (4) tuberculids. In our case, it was suspected that the cellulitislike erythema may have been caused by hematogenous spread from pulmonary tuberculosis. Considering that negative reactions to purified protein derivative (tuberculin) skin tests often are observed in cases of miliary tuberculosis (widespread dissemination of M tuberculosis to 2 or more organs via hematogenous spread), we suspected that our patient could proceed to miliary tuberculosis; in fact, a case was reported in which miliary tuberculosis emerged approximately 3 weeks after the onset of erythema,13 as observed in the present case. Therefore, erythema in the setting of tuberculosis may be a predictor of miliary tuberculosis. The types of cutaneous lesions caused by tuberculosis infection also are dependent on multiple host factors.2 Cutaneous tuberculosis with an atypical clinical appearance has become more common because of the increasing number of immunocompromised patients.17

In addition, most cases of cutaneous tuberculosis are not associated with pain. Generally, tuberculous cellulitis also causes nontender erythematous plaques or nodules.2 However, in some cases of tuberculous cellulitis, including our case, tender skin lesions have been reported.12-14 Therefore, this symptom is not a sensitive factor for differential diagnosis.

We suggest that tuberculous cellulitis should always be included in the differential diagnosis of a cellulitislike rash with or without pain if the skin lesion is not improved despite antibiotic therapy.

- Daido-Horiuchi Y, Kikuchi Y, Kobayashi S, et al. Tuberculous cellulitis in a patient with chronic kidney disease and polymyalgia rheumatica. Intern Med. 2012;51:3203-3206.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2011:322-329.

- Schupbach CW, Wheeler CE Jr, Briggaman RA, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of disseminated cryptococcosis. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1734-1740.

- Hsu PY, Yang YH, Hsiao CH, et al. Mycobacterium kansasii infection presenting as cellulitis in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Formos Med Assoc. 2002;101:581-584.

- Aguayo-Leiva I, Vano-Galván S, Salguero I, et al. Reactive angioendotheliomatosis in a patient with myelodysplastic syndrome presenting as a cellulitis-like plaque. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19:182-183.

- Yang HI, Lee MC, Kuo TT, et al. Cellulitis-like cutaneous metastasis of uterine cervical carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:S26-S28.

- Tzeng HE, Teng CL, Yang Y, et al. Occult subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma with initial presentations of cellulitis-like skin lesion and fulminant hemophagocytosis. J Formos Med Assoc. 2007;106:S55-S59.

- Sharma PK, Sabhnani S, Bhardwaj M, et al. Acral, pure cutaneous, self-healing, late-onset, cellulitis-like Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2009;13:43-47.

- Tercedor J, Ródenas JM, Henraz MT, et al. Facial cellulitis-like Sweet’s syndrome in acute myelogenous leukemia. Int J Dermatol. 1992;31:598-599.

- Inaoki M, Nishijima C, Kumada S, et al. Adult-onset Still disease with a cellulitis-like eruption. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19:80-81.

- Prabhu MM, Prabhu S, Mishra P, et al. Cellulitis-like fixed drug eruption attributed to paracetamol (acetaminophen). Dermatol Online J. 2005;11:24.

- Lee NH, Choi EH, Lee WS, et al. Tuberculous cellulitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:222-223.

- Kim JE, Ko JY, Bae SC, et al. Tuberculous cellulitis as a manifestation of miliary tuberculosis in a patient with malignancy-associated dermatomyositis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:450-452.

- Chin PW, Koh CK, Wong KT. Cutaneous tuberculosis mimicking cellulitis in an immunosuppressed patient. Singapore Med J. 1999;40:44-45.

- Seyahi N, Apaydin S, Kahveci A, et al. Cellulitis as a manifestation of miliary tuberculosis in a renal transplant recipient. Transpl Infect Dis. 2005;7:80-85.

- Kato G, Watanabe K, Shibuya Y, et al. A case of cutaneous tuberculosis with cellulitis-like appearance [in Japanese]. Rinsho Hifuka (Jpn J Clin Dermatol). 2010;64:1055-1059.

- Fariña MC, Gegundez MI, Piqué E, et al. Cutaneous tuberculosis: a clinical, histopathologic, and bacteriologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:433-440.

Local tender erythema is a typical manifestation of cellulitis, which is commonly seen by dermatologists; however, cutaneous manifestations of other diseases may bear resemblance to the more banal cellulitis. We present the case of a patient with tuberculous cellulitis, a rare variant of cutaneous tuberculosis.

Case Report

An 89-year-old man presented to a local primary care physician with a fever (temperature, 38°C). Infectious disease was suspected. Antibiotic therapy with oral cefaclor and intravenous cefotiam hydrochloride was started, but the patient’s fever did not subside. Six days after initiation of treatment, he was referred to our dermatology department for evaluation of a painful erythematous rash on the left thigh that had suddenly appeared. The patient had a history of pulmonary tuberculosis 71 years prior. He also underwent surgical treatment of pancreatic cancer 14 years prior. Additionally, he had chronic kidney disease (CKD) and polymyalgia rheumatica, which was currently being treated with oral prednisolone 5 mg once daily.

Physical examination revealed a hot and tender erythematous plaque on the left thigh (Figure 1). The edge of the lesion was not well defined and there was no regional lymphadenopathy.

A complete blood cell count revealed anemia (white blood cell count, 8070/μL [reference range, 4000–9,000/μL]; neutrophils, 77.1% [reference range, 44%–74%]; lymphocytes, 13.8% [reference range, 20%–50%]; hemoglobin, 9.3 g/dL [reference range, 13.0–17.0 g/dL]; and platelet count, 329×103/μL [reference range, 150–400×103/μL]). The C-reactive protein level was 7.3 mg/dL (reference range, 0.08–0.3 mg/dL). The creatinine level was 2.93 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6–1.2 mg/dL). There were no signs of liver dysfunction.

A blood culture was negative. A purified protein derivative (tuberculin) skin test was negative (6×7 mm [reference range, ≤9 mm). A chest computed tomography (CT) scan showed small centrilobular nodules that had not changed in number or size since evaluation 3 months prior.

The antibiotics were changed to meropenem hydrate 0.5 g and clindamycin 300 mg twice daily for presumed bacterial cellulitis, then meropenem hydrate 1 g and clindamycin 600 mg daily, but there was still no improvement after about 1 week. Therefore, a skin biopsy was performed on the left thigh. The specimen showed epithelioid cell granulomas throughout the dermis and subcutis (Figure 2). Ziehl-Neelsen stain revealed numerous acid-fast bacilli (Figure 3). Polymerase chain reaction was positive for Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the skin biopsy specimen and gastric fluid. Additionally, M tuberculosis was isolated from the skin biopsy specimen, gastric fluid, and sputum culture. After the series of treatments described above, a remarkable increase in nodule size and number was observed in a follow-up chest CT scan compared with the prior examination. These pulmonary lesions showed bronchogenic spread.

A diagnosis of tuberculous cellulitis with pulmonary tuberculosis was made. Treatment with isoniazid 200 mg once daily, rifampin 300 mg once daily, and ethambutol 500 mg once every other day was started; the dosages were reduced from the standard dose due to the patient’s CKD.1 Four days after initiation of these medications, the patient was transferred to a hospital specifically for the treatment of tuberculosis. Approximately 8 months after treatment with isoniazid, rifampin, and ethambutol, M tuberculosis could not be detected in the sputum and a chest CT revealed that the pulmonary lesions were remarkably improved. However, polymerase chain reaction of the skin biopsy specimen was still positive for M tuberculosis. It was determined that debridement of the skin lesion was needed, but the patient died from complications of deteriorating CKD 10 months after the initiation of the antituberculosis medications.

Comment

Cellulitis is a suppurative inflammation involving the subcutis.2 Local tender erythema, malaise, chills, and fever may be present at the onset. Cellulitis is commonly seen by dermatologists, and it is well known that other infectious diseases such as necrotizing fasciitis, cutaneous and subcutaneous mycoses,3 and nontuberculous mycobacterial infections4 sometimes present as cellulitislike skin lesions. Moreover, noninfectious diseases, such as Wells syndrome, thrombophlebitis, reactive angioendotheliomatosis,5 cutaneous metastasis of a primary malignancy,6 subcutaneous panniculitislike T-cell lymphoma,7 Langerhans cell histiocytosis,8 Sweet syndrome,9 adult-onset Still disease,10 and fixed drug eruption caused by acetaminophen11 should be excluded. These differential diagnoses and diagnostic clues of cellulitislike erythema are summarized in Table 1.3-16

Cutaneous tuberculosis presenting as cellulitis, so-called tuberculous cellulitis, also is characterized as a clinical mimicker of cellulitis. On the other hand, histologically, it has features of cutaneous tuberculosis (eg, necrotic granuloma).12,14,15 Tuberculous cellulitis is rare and therefore may often be misdiagnosed even in highly endemic areas. We summarized the clinical information of 5 well-documented cases of tuberculous cellulitis along with the current case in Table 2.12-16 All of these cases had an associated disease and involved patients who were currently taking oral corticosteroids. If a patient undergoing immunosuppressive therapy develops cellulitislike erythema, tuberculous cellulitis should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Cutaneous tuberculosis generally is classified into 4 types according to the mechanism of disease acquisition: (1) inoculation from an exogenous source, (2) endogenous cutaneous spread contiguously or by autoinoculation, (3) hematogenous spread to the skin, and (4) tuberculids. In our case, it was suspected that the cellulitislike erythema may have been caused by hematogenous spread from pulmonary tuberculosis. Considering that negative reactions to purified protein derivative (tuberculin) skin tests often are observed in cases of miliary tuberculosis (widespread dissemination of M tuberculosis to 2 or more organs via hematogenous spread), we suspected that our patient could proceed to miliary tuberculosis; in fact, a case was reported in which miliary tuberculosis emerged approximately 3 weeks after the onset of erythema,13 as observed in the present case. Therefore, erythema in the setting of tuberculosis may be a predictor of miliary tuberculosis. The types of cutaneous lesions caused by tuberculosis infection also are dependent on multiple host factors.2 Cutaneous tuberculosis with an atypical clinical appearance has become more common because of the increasing number of immunocompromised patients.17

In addition, most cases of cutaneous tuberculosis are not associated with pain. Generally, tuberculous cellulitis also causes nontender erythematous plaques or nodules.2 However, in some cases of tuberculous cellulitis, including our case, tender skin lesions have been reported.12-14 Therefore, this symptom is not a sensitive factor for differential diagnosis.

We suggest that tuberculous cellulitis should always be included in the differential diagnosis of a cellulitislike rash with or without pain if the skin lesion is not improved despite antibiotic therapy.

Local tender erythema is a typical manifestation of cellulitis, which is commonly seen by dermatologists; however, cutaneous manifestations of other diseases may bear resemblance to the more banal cellulitis. We present the case of a patient with tuberculous cellulitis, a rare variant of cutaneous tuberculosis.

Case Report

An 89-year-old man presented to a local primary care physician with a fever (temperature, 38°C). Infectious disease was suspected. Antibiotic therapy with oral cefaclor and intravenous cefotiam hydrochloride was started, but the patient’s fever did not subside. Six days after initiation of treatment, he was referred to our dermatology department for evaluation of a painful erythematous rash on the left thigh that had suddenly appeared. The patient had a history of pulmonary tuberculosis 71 years prior. He also underwent surgical treatment of pancreatic cancer 14 years prior. Additionally, he had chronic kidney disease (CKD) and polymyalgia rheumatica, which was currently being treated with oral prednisolone 5 mg once daily.

Physical examination revealed a hot and tender erythematous plaque on the left thigh (Figure 1). The edge of the lesion was not well defined and there was no regional lymphadenopathy.

A complete blood cell count revealed anemia (white blood cell count, 8070/μL [reference range, 4000–9,000/μL]; neutrophils, 77.1% [reference range, 44%–74%]; lymphocytes, 13.8% [reference range, 20%–50%]; hemoglobin, 9.3 g/dL [reference range, 13.0–17.0 g/dL]; and platelet count, 329×103/μL [reference range, 150–400×103/μL]). The C-reactive protein level was 7.3 mg/dL (reference range, 0.08–0.3 mg/dL). The creatinine level was 2.93 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6–1.2 mg/dL). There were no signs of liver dysfunction.

A blood culture was negative. A purified protein derivative (tuberculin) skin test was negative (6×7 mm [reference range, ≤9 mm). A chest computed tomography (CT) scan showed small centrilobular nodules that had not changed in number or size since evaluation 3 months prior.

The antibiotics were changed to meropenem hydrate 0.5 g and clindamycin 300 mg twice daily for presumed bacterial cellulitis, then meropenem hydrate 1 g and clindamycin 600 mg daily, but there was still no improvement after about 1 week. Therefore, a skin biopsy was performed on the left thigh. The specimen showed epithelioid cell granulomas throughout the dermis and subcutis (Figure 2). Ziehl-Neelsen stain revealed numerous acid-fast bacilli (Figure 3). Polymerase chain reaction was positive for Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the skin biopsy specimen and gastric fluid. Additionally, M tuberculosis was isolated from the skin biopsy specimen, gastric fluid, and sputum culture. After the series of treatments described above, a remarkable increase in nodule size and number was observed in a follow-up chest CT scan compared with the prior examination. These pulmonary lesions showed bronchogenic spread.

A diagnosis of tuberculous cellulitis with pulmonary tuberculosis was made. Treatment with isoniazid 200 mg once daily, rifampin 300 mg once daily, and ethambutol 500 mg once every other day was started; the dosages were reduced from the standard dose due to the patient’s CKD.1 Four days after initiation of these medications, the patient was transferred to a hospital specifically for the treatment of tuberculosis. Approximately 8 months after treatment with isoniazid, rifampin, and ethambutol, M tuberculosis could not be detected in the sputum and a chest CT revealed that the pulmonary lesions were remarkably improved. However, polymerase chain reaction of the skin biopsy specimen was still positive for M tuberculosis. It was determined that debridement of the skin lesion was needed, but the patient died from complications of deteriorating CKD 10 months after the initiation of the antituberculosis medications.

Comment

Cellulitis is a suppurative inflammation involving the subcutis.2 Local tender erythema, malaise, chills, and fever may be present at the onset. Cellulitis is commonly seen by dermatologists, and it is well known that other infectious diseases such as necrotizing fasciitis, cutaneous and subcutaneous mycoses,3 and nontuberculous mycobacterial infections4 sometimes present as cellulitislike skin lesions. Moreover, noninfectious diseases, such as Wells syndrome, thrombophlebitis, reactive angioendotheliomatosis,5 cutaneous metastasis of a primary malignancy,6 subcutaneous panniculitislike T-cell lymphoma,7 Langerhans cell histiocytosis,8 Sweet syndrome,9 adult-onset Still disease,10 and fixed drug eruption caused by acetaminophen11 should be excluded. These differential diagnoses and diagnostic clues of cellulitislike erythema are summarized in Table 1.3-16

Cutaneous tuberculosis presenting as cellulitis, so-called tuberculous cellulitis, also is characterized as a clinical mimicker of cellulitis. On the other hand, histologically, it has features of cutaneous tuberculosis (eg, necrotic granuloma).12,14,15 Tuberculous cellulitis is rare and therefore may often be misdiagnosed even in highly endemic areas. We summarized the clinical information of 5 well-documented cases of tuberculous cellulitis along with the current case in Table 2.12-16 All of these cases had an associated disease and involved patients who were currently taking oral corticosteroids. If a patient undergoing immunosuppressive therapy develops cellulitislike erythema, tuberculous cellulitis should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Cutaneous tuberculosis generally is classified into 4 types according to the mechanism of disease acquisition: (1) inoculation from an exogenous source, (2) endogenous cutaneous spread contiguously or by autoinoculation, (3) hematogenous spread to the skin, and (4) tuberculids. In our case, it was suspected that the cellulitislike erythema may have been caused by hematogenous spread from pulmonary tuberculosis. Considering that negative reactions to purified protein derivative (tuberculin) skin tests often are observed in cases of miliary tuberculosis (widespread dissemination of M tuberculosis to 2 or more organs via hematogenous spread), we suspected that our patient could proceed to miliary tuberculosis; in fact, a case was reported in which miliary tuberculosis emerged approximately 3 weeks after the onset of erythema,13 as observed in the present case. Therefore, erythema in the setting of tuberculosis may be a predictor of miliary tuberculosis. The types of cutaneous lesions caused by tuberculosis infection also are dependent on multiple host factors.2 Cutaneous tuberculosis with an atypical clinical appearance has become more common because of the increasing number of immunocompromised patients.17

In addition, most cases of cutaneous tuberculosis are not associated with pain. Generally, tuberculous cellulitis also causes nontender erythematous plaques or nodules.2 However, in some cases of tuberculous cellulitis, including our case, tender skin lesions have been reported.12-14 Therefore, this symptom is not a sensitive factor for differential diagnosis.

We suggest that tuberculous cellulitis should always be included in the differential diagnosis of a cellulitislike rash with or without pain if the skin lesion is not improved despite antibiotic therapy.

- Daido-Horiuchi Y, Kikuchi Y, Kobayashi S, et al. Tuberculous cellulitis in a patient with chronic kidney disease and polymyalgia rheumatica. Intern Med. 2012;51:3203-3206.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2011:322-329.

- Schupbach CW, Wheeler CE Jr, Briggaman RA, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of disseminated cryptococcosis. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1734-1740.

- Hsu PY, Yang YH, Hsiao CH, et al. Mycobacterium kansasii infection presenting as cellulitis in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Formos Med Assoc. 2002;101:581-584.

- Aguayo-Leiva I, Vano-Galván S, Salguero I, et al. Reactive angioendotheliomatosis in a patient with myelodysplastic syndrome presenting as a cellulitis-like plaque. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19:182-183.

- Yang HI, Lee MC, Kuo TT, et al. Cellulitis-like cutaneous metastasis of uterine cervical carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:S26-S28.

- Tzeng HE, Teng CL, Yang Y, et al. Occult subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma with initial presentations of cellulitis-like skin lesion and fulminant hemophagocytosis. J Formos Med Assoc. 2007;106:S55-S59.

- Sharma PK, Sabhnani S, Bhardwaj M, et al. Acral, pure cutaneous, self-healing, late-onset, cellulitis-like Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2009;13:43-47.

- Tercedor J, Ródenas JM, Henraz MT, et al. Facial cellulitis-like Sweet’s syndrome in acute myelogenous leukemia. Int J Dermatol. 1992;31:598-599.

- Inaoki M, Nishijima C, Kumada S, et al. Adult-onset Still disease with a cellulitis-like eruption. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19:80-81.

- Prabhu MM, Prabhu S, Mishra P, et al. Cellulitis-like fixed drug eruption attributed to paracetamol (acetaminophen). Dermatol Online J. 2005;11:24.

- Lee NH, Choi EH, Lee WS, et al. Tuberculous cellulitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:222-223.

- Kim JE, Ko JY, Bae SC, et al. Tuberculous cellulitis as a manifestation of miliary tuberculosis in a patient with malignancy-associated dermatomyositis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:450-452.

- Chin PW, Koh CK, Wong KT. Cutaneous tuberculosis mimicking cellulitis in an immunosuppressed patient. Singapore Med J. 1999;40:44-45.

- Seyahi N, Apaydin S, Kahveci A, et al. Cellulitis as a manifestation of miliary tuberculosis in a renal transplant recipient. Transpl Infect Dis. 2005;7:80-85.

- Kato G, Watanabe K, Shibuya Y, et al. A case of cutaneous tuberculosis with cellulitis-like appearance [in Japanese]. Rinsho Hifuka (Jpn J Clin Dermatol). 2010;64:1055-1059.

- Fariña MC, Gegundez MI, Piqué E, et al. Cutaneous tuberculosis: a clinical, histopathologic, and bacteriologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:433-440.

- Daido-Horiuchi Y, Kikuchi Y, Kobayashi S, et al. Tuberculous cellulitis in a patient with chronic kidney disease and polymyalgia rheumatica. Intern Med. 2012;51:3203-3206.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2011:322-329.

- Schupbach CW, Wheeler CE Jr, Briggaman RA, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of disseminated cryptococcosis. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1734-1740.

- Hsu PY, Yang YH, Hsiao CH, et al. Mycobacterium kansasii infection presenting as cellulitis in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Formos Med Assoc. 2002;101:581-584.

- Aguayo-Leiva I, Vano-Galván S, Salguero I, et al. Reactive angioendotheliomatosis in a patient with myelodysplastic syndrome presenting as a cellulitis-like plaque. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19:182-183.

- Yang HI, Lee MC, Kuo TT, et al. Cellulitis-like cutaneous metastasis of uterine cervical carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:S26-S28.

- Tzeng HE, Teng CL, Yang Y, et al. Occult subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma with initial presentations of cellulitis-like skin lesion and fulminant hemophagocytosis. J Formos Med Assoc. 2007;106:S55-S59.

- Sharma PK, Sabhnani S, Bhardwaj M, et al. Acral, pure cutaneous, self-healing, late-onset, cellulitis-like Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2009;13:43-47.

- Tercedor J, Ródenas JM, Henraz MT, et al. Facial cellulitis-like Sweet’s syndrome in acute myelogenous leukemia. Int J Dermatol. 1992;31:598-599.

- Inaoki M, Nishijima C, Kumada S, et al. Adult-onset Still disease with a cellulitis-like eruption. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19:80-81.

- Prabhu MM, Prabhu S, Mishra P, et al. Cellulitis-like fixed drug eruption attributed to paracetamol (acetaminophen). Dermatol Online J. 2005;11:24.

- Lee NH, Choi EH, Lee WS, et al. Tuberculous cellulitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:222-223.

- Kim JE, Ko JY, Bae SC, et al. Tuberculous cellulitis as a manifestation of miliary tuberculosis in a patient with malignancy-associated dermatomyositis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:450-452.

- Chin PW, Koh CK, Wong KT. Cutaneous tuberculosis mimicking cellulitis in an immunosuppressed patient. Singapore Med J. 1999;40:44-45.

- Seyahi N, Apaydin S, Kahveci A, et al. Cellulitis as a manifestation of miliary tuberculosis in a renal transplant recipient. Transpl Infect Dis. 2005;7:80-85.

- Kato G, Watanabe K, Shibuya Y, et al. A case of cutaneous tuberculosis with cellulitis-like appearance [in Japanese]. Rinsho Hifuka (Jpn J Clin Dermatol). 2010;64:1055-1059.

- Fariña MC, Gegundez MI, Piqué E, et al. Cutaneous tuberculosis: a clinical, histopathologic, and bacteriologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:433-440.

Primary Cutaneous Dermal Mucinosis on Herpes Zoster Scars

Mucin is an amorphous gelatinous substance that is found in a large variety of tissues. There are 2 types of cutaneous mucin: dermal and epithelial. Both types appear as basophilic shreds and granules with hematoxylin and eosin stain.1 Epithelial mucin (sialomucin) is found mainly in the gastrointestinal tract and lungs. In the skin, it is present in the cytoplasm of the dark cells of the eccrine glands and in the apocrine secretory cells. Epithelial mucin contains both neutral and acid glycosaminoglycans, stains positive with Alcian blue (pH 2.5) and periodic acid–Schiff, is resistant to hyaluronidase, and does not stain metachromatically with toluidine blue. Dermal mucin is composed of acid glycosaminoglycans (eg, dermatan sulfate, chondroitin 6-sulfate, chondroitin 4-sulfate, hyaluronic acid) and normally is produced by dermal fibroblasts. Dermal mucin stains positive with Alcian blue (pH 2.5); is periodic acid–Schiff negative and sensitive to hyaluronidase; and shows metachromasia with toluidine blue, methylene blue, and thionine.

Cutaneous mucinosis comprises a heterogeneous group of skin disorders characterized by the deposition of mucin in the interstices of the dermis. These diseases may be classified as primary mucinosis with the mucin deposition as the main histologic feature resulting in clinically distinctive lesions and secondary mucinosis with the mucin deposition as an additional histologic finding within the context of an independent skin disease or lesion (eg, basal cell carcinoma) with deposits of mucin in the stroma. Primary cutaneous mucinosis may be subclassified into 2 groups: degenerative-inflammatory mucinoses and neoplastic-hamartomatous mucinoses. According to the histologic features, the degenerative-inflammatory mucinoses are better divided into dermal and follicular mucinoses.2 We describe a case of primary cutaneous dermal mucinosis on herpes zoster (HZ) scars as an isotopic response.

Case Report

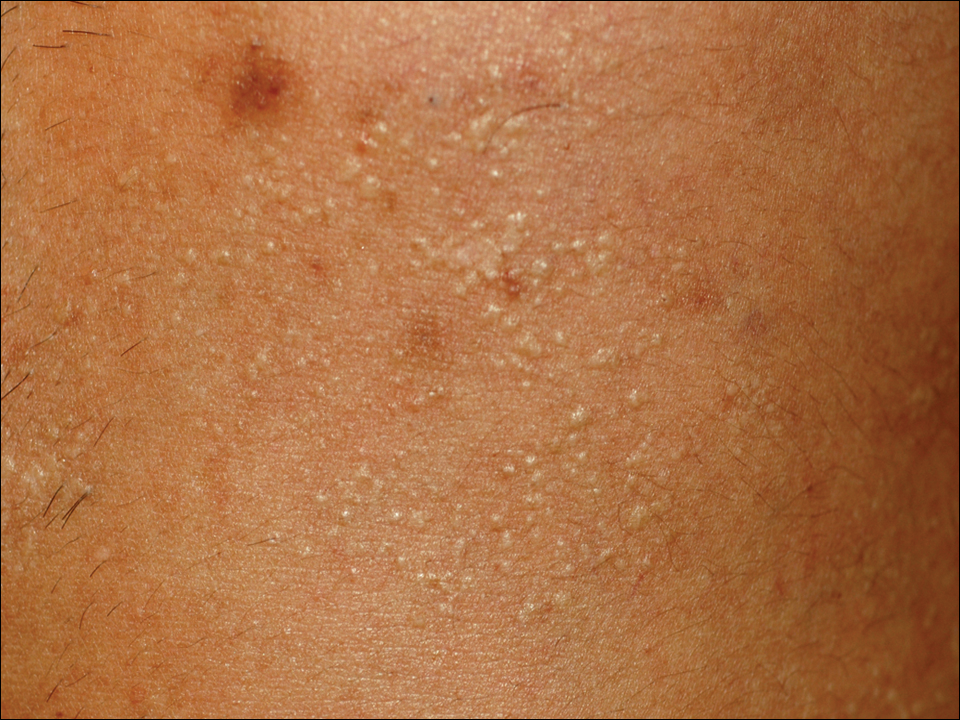

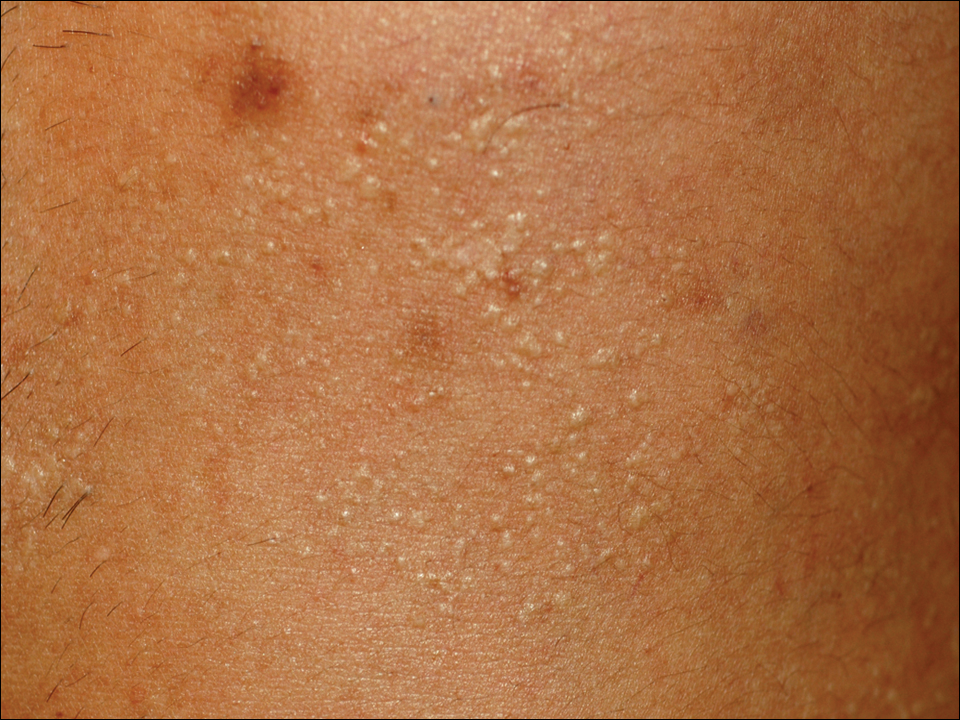

A 33-year-old man presented to the dermatology department with slightly pruritic lesions on the left side of the chest and back that had appeared progressively at the site of HZ scars that had healed without treatment 9 months prior. Dermatologic examination revealed sharply defined whitish papules (Figure 1) measuring 2 to 4 mm in diameter with a smooth surface and linear distribution over the area of the left T8 and T9 dermatomes. The patient reported no postherpetic neuralgia and was otherwise healthy. Laboratory tests including a complete blood cell count, biochemistry, urinalysis, and determination of free thyroid hormones were within reference range. Serologic tests for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B and C viruses, and syphilis were negative. Antinuclear antibodies also were negative.

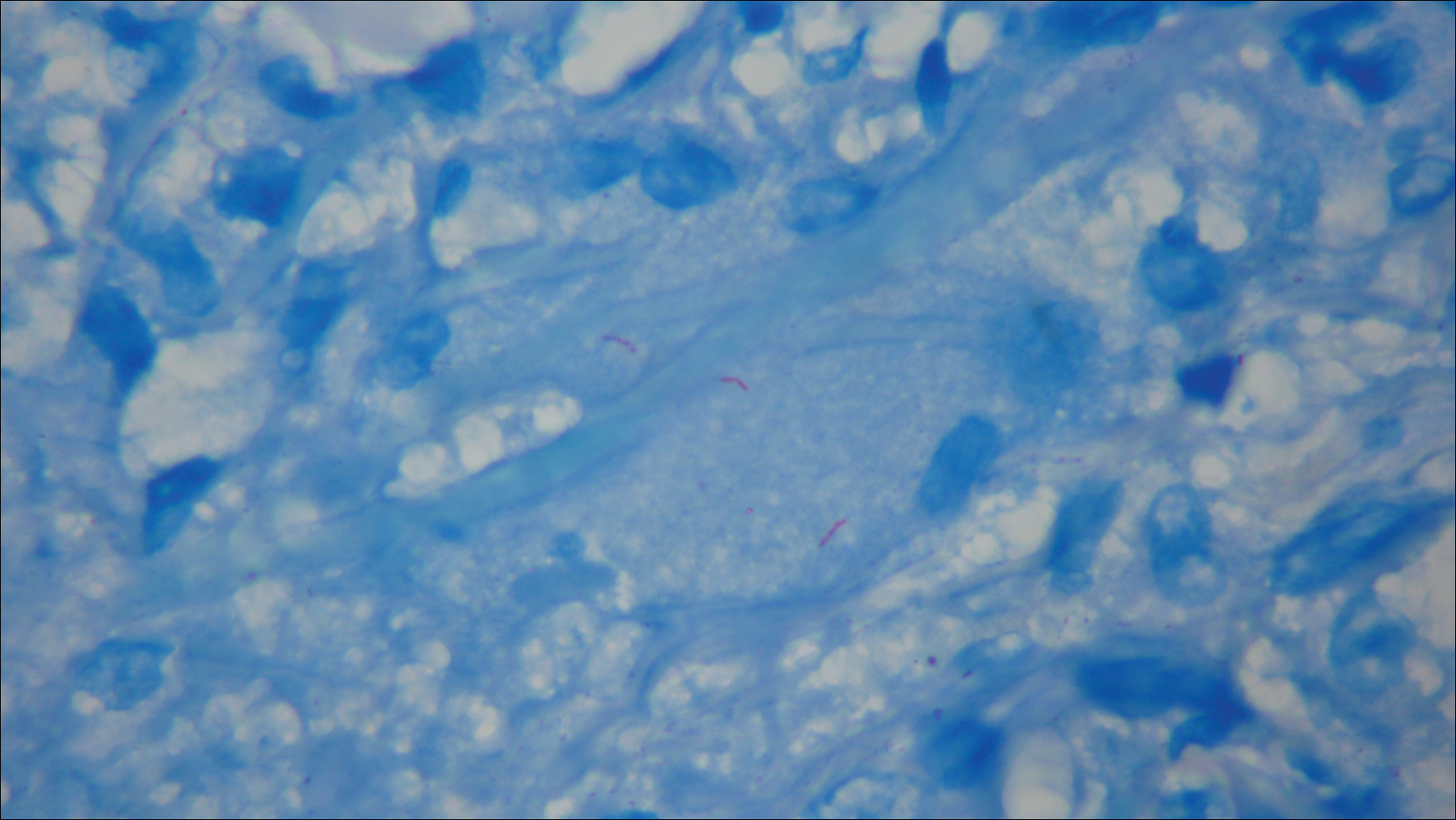

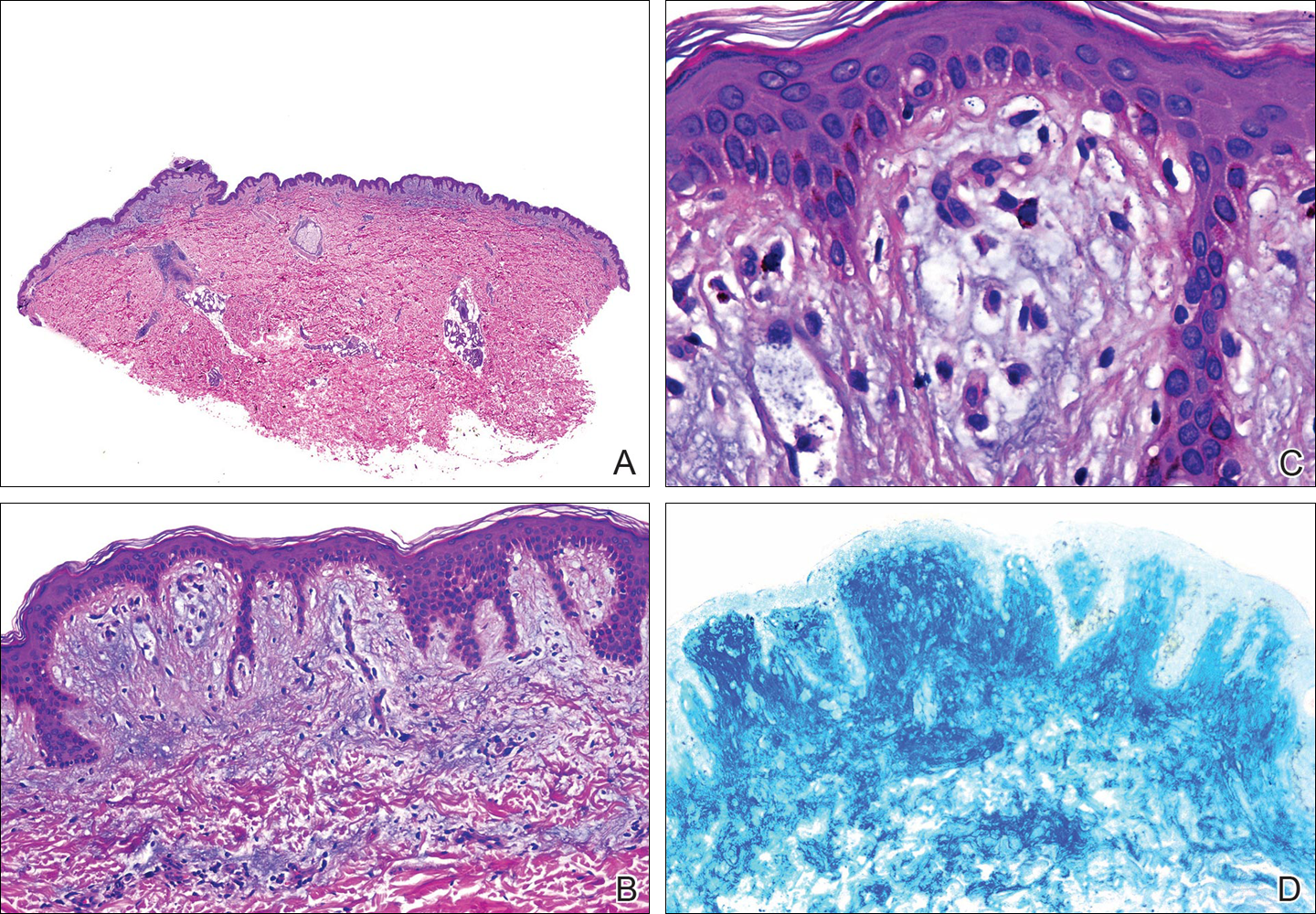

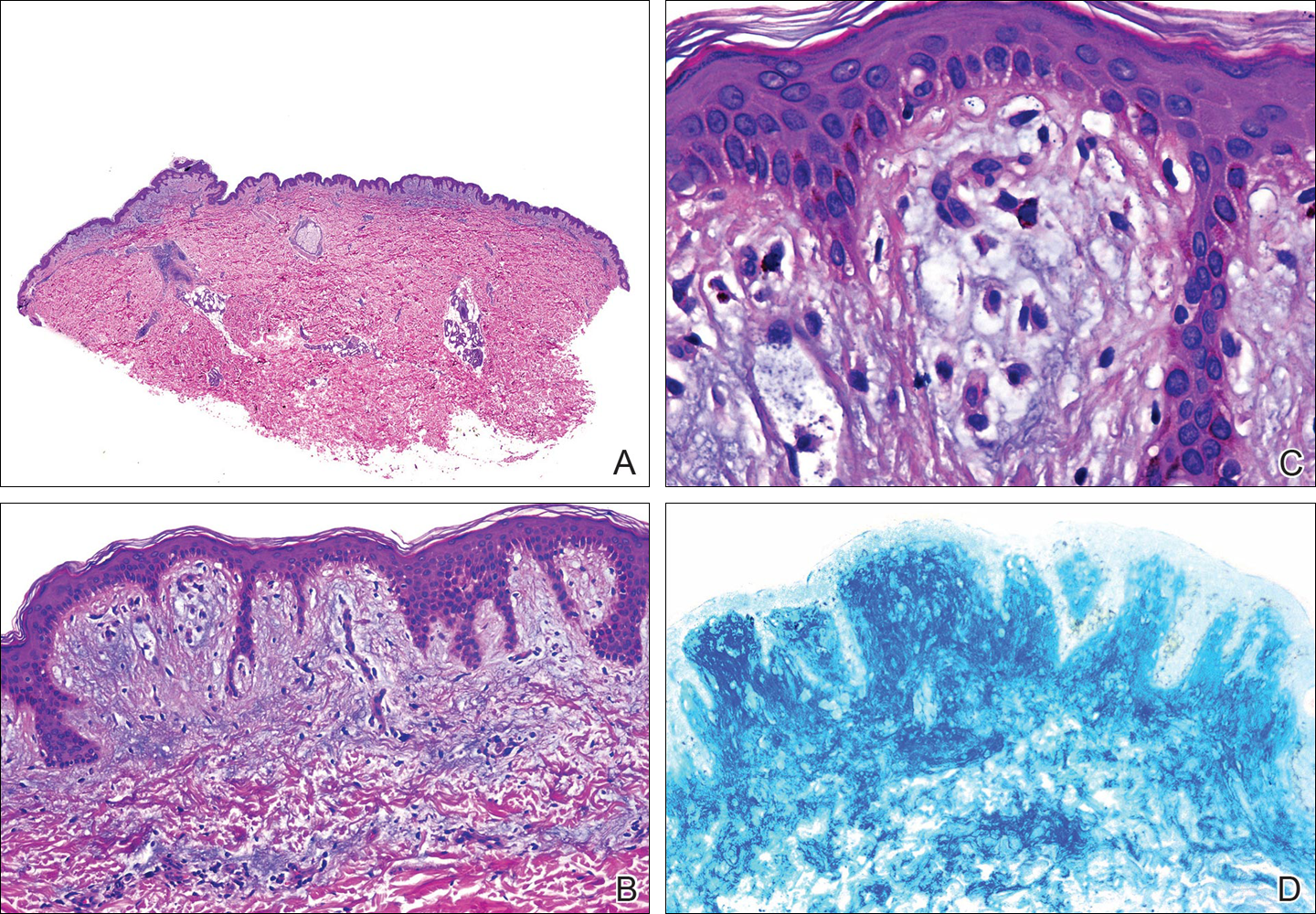

Histopathology demonstrated abundant bluish granular material between collagen bundles of the papillary dermis (Figure 2). No cytopathologic signs of active herpetic infection were seen. The Alcian blue stain at pH 2.5 was strongly positive for mucin, which confirmed the diagnosis of primary cutaneous dermal mucinosis.

Topical corticosteroids were applied for 2 months with no notable improvement. The lesions gradually improved without any other therapy during the subsequent 6 months.

Comment

The occurrence of a new skin disease at the exact site of a prior unrelated cutaneous disorder that had already resolved was first reported by Wyburn-Mason3 in 1955. Forty years later, the term isotopic response was coined by Wolf et al4 to describe this phenomenon. Diverse types of skin diseases such as herpes simplex virus,5 varicella-zoster infections,4 and thrombophlebitis4 have been implicated in cases of isotopic response, but the most frequently associated primary disorder by far is cutaneous HZ.

Several benign and malignant disorders may occur at sites of resolved HZ lesions, including granulomatous dermatitis,6 granuloma annulare,7 fungal granuloma,8 fungal folliculitis,9 psoriasis,10 morphea,11 lichen sclerosus,12 Kaposi sarcoma,13 the lichenoid variant of chronic graft-versus-host disease,14 cutaneous sarcoidosis,15 granulomatous folliculitis,16 comedones,17 furuncles,18 erythema annulare centrifugum,19 eosinophilic dermatosis,20 cutaneous pseudolymphoma,21 granulomatous vasculitis,22 Rosai-Dorfman disease,12 xanthomatous changes,23 tuberculoid granulomas,24 acneform eruption,25 lichen planus,26 acquired reactive perforating collagenosis,27 lymphoma,28 leukemia,29 angiosarcoma,30 basal cell carcinoma,31 squamous cell carcinoma, and cutaneous metastasis from internal carcinoma.32 The interval between the acute HZ episode and presentation of the second disease is quite variable, ranging from days to several months. Postzoster isotopic response has been described in individuals with varying degrees of immune response, affecting both immunocompetent12 and immunocompromised patients.14 There is no predilection for age, sex, or race. It also seems that antiviral treatment during the active episode does not prevent the development of secondary reactions.Kim et al33 reported a 59-year-old woman who developed flesh-colored or erythematous papules on HZ scars over the area of the left T1 and T2 dermatomes 1 week after the active viral process. Histopathologic study demonstrated deposition of mucin between collagen bundles in the dermis. The authors established the diagnosis of secondary cutaneous mucinosis as an isotopic response.33 Nevertheless, we believe that based on the aforementioned classification of cutaneous mucinosis,2 both this case and our case are better considered as primary cutaneous dermal mucinosis, as the mucin deposition in the dermis was the main histologic finding resulting in a distinctive cutaneous disorder. In the case reported by Kim et al,33 a possible relationship between cutaneous mucinosis and postherpetic neuralgia was suggested based on the slow regression of skin lesions in accordance with the improvement of the neuralgic pain; however, our patient did not have postherpetic neuralgia and the lesions persisted unchanged several months after the acute HZ episode. In the literature, there are reports of primary cutaneous dermal mucinosis associated with altered thyroid function34; autoimmune connective tissue diseases, mostly lupus erythematosus35; monoclonal gammopathy36; and human immunodeficiency virus infection,37 but these possibilities were ruled out in our patient by pertinent laboratory studies.

The pathogenesis of the postherpetic isotopic response remains unknown, but several mechanisms have been proposed. Some authors have suggested that postzoster dermatoses may represent isomorphic response of Köbner phenomenon.13,15 Although isomorphic and isotopic responses share some similarities, these terms describe 2 different phenomena: the first refers to the appearance of the same cutaneous disorder at a different site favored by trauma, while the second manifests a new and unrelated disease at the same location.38 Local anatomic changes such as altered microcirculation, collagen rearrangement, and an imperfect skin barrier may promote a prolonged local inflammatory response. Moreover, the destruction of nerve fibers by the varicella-zoster virus may indirectly influence the local immune system through the release of specific neuropeptides in the skin.39 It has been speculated that some secondary reactions may be the result of type III and type IV hypersensitivity reactions40 to viral antigens or to tissue antigens modified by the virus, inducing either immune hypersensitivity or local immune suppression.41 Some authors have documented the presence of varicella-zoster DNA within early postzoster lesions6,7 by using polymerase chain reaction in early lesions but not in late-stage and residual lesions.12,22 Nikkels et al42 studied early granulomatous lesions by immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization techniques and concluded that major viral envelope glycoproteins (glycoproteins I and II) rather than complete viral particles could be responsible for delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions. All these findings suggest that secondary reactions presenting on HZ scars are mainly the result of atypical immune reactions to local antigenic stimuli.

The pathogenesis of our case is unknown. From a theoretical point of view, it is possible that varicella-zoster virus may induce fibroblastic proliferation and mucin production on HZ scars; however, if HZ is a frequent process and the virus may induce mucin production, then focal dermal mucinosis in an HZ scar should be a common finding. In our patient, there was no associated disease favoring the development of the cutaneous mucinosis. These localized variants of primary cutaneous mucinosis usually do not require therapy, and a wait-and-see approach is recommended. Topical applications of corticosteroids, pimecrolimus, or tacrolimus, as well as oral isotretinoin, may have some benefit,43 but spontaneous resolution may occur.44 In our patient, topical corticosteroids were applied 2 months following initial presentation without any benefit and the cutaneous lesions gradually improved without any therapy during the subsequent 6 months. Focal dermal mucinosis should be added to the list of cutaneous reactions that may develop in HZ scars.

- Truhan AP, Roenigk HH Jr. The cutaneous mucinoses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14:1-18.

- Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Cutaneous mucinoses: microscopic criteria for diagnosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:257-267.

- Wyburn-Mason R. Malignant change arising in tissues affected by herpes. BMJ. 1955;2:1106-1109.

- Wolf R, Brenner S, Ruocco V, et al. Isotopic response. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:341-348.

- Ruocco E. Genital warts at the site of healed herpes progenitalis: the isotopic response. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:705-706.

- Serfling U, Penneys NS, Zhu WY, et al. Varicella-zoster virus DNA in granulomatous skin lesions following herpes zoster. a study by the polymerase chain reaction. J Cutan Pathol. 1993;20:28-33.

- Gibney MD, Nahass GT, Leonardi CL. Cutaneous reactions following herpes zoster infections: report of three cases and a review of the literature. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:504-509.

- Huang CW, Tu ME, Wu YH, et al. Isotopic response of fungal granuloma following facial herpes zoster infections-report of three cases. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:1141-1145.

- Tüzün Y, Işçimen A, Göksügür N, et al. Wolf’s isotopic response: Trichophyton rubrum folliculitis appearing on a herpes zoster scar. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:766-768.

- Allegue F, Fachal C, Romo M, et al. Psoriasis at the site of healed herpes zoster: Wolf’s isotopic response. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2007;98:576-578.

- Forschner A, Metzler G, Rassner G, et al. Morphea with features of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus at the site of a herpes zoster scar: another case of an isotopic response. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:524-525.

- Requena L, Kutzner H, Escalonilla P, et al. Cutaneous reactions at sites of herpes zoster scars: an expanded spectrum. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:161-168.

- Niedt GW, Prioleau PG. Kaposi’s sarcoma occurring in a dermatome previously involved by herpes zoster. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18:448-451.

- Sanli H, Anadolu R, Arat M, et al. Dermatomal lichenoid graft-versus-host disease within herpes zoster scars. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:562-564.

- Cecchi R, Giomi A. Scar sarcoidosis following herpes zoster. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1999;12:280-282.

- Fernández-Redondo V, Amrouni B, Varela E, et al. Granulomatous folliculitis at sites of herpes zoster scars: Wolf’s isotopic response. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16:628-630.

- Sanchez-Salas MP. Appearance of comedones at the site of healed herpes zoster: Wolf’s isotopic response. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:633-634.

- Ghorpade A. Wolf’s isotopic response—furuncles at the site of healed herpes zoster in an Indian male. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:105-107.

- Lee HW, Lee DK, Rhee DY, et al. Erythema annulare centrifugum following herpes zoster infection: Wolf’s isotopic response? Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:1241-1243.

- Mitsuhashi Y, Kondo S. Post-zoster eosinophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:465-466.

- Roo E, Villegas C, Lopez-Bran E, et al. Postzoster cutaneous pseudolymphoma. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:661-663.

- Langenberg A, Yen TS, LeBoit PE. Granulomatous vasculitis occurring after cutaneous herpes zoster despite absence of viral genome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:429-433.

- Weidman F, Boston LN. Generalized xanthoma tuberosum with xantomathous changes in fresh scars of intercurrent zoster. Arch Intern Med. 1937;59:793-822.

- Olalquiaga J, Minaño R, Barrio J. Granuloma tuberculoide post-herpético en un paciente con leucemia linfocítica crónica. Med Cutan ILA. 1995;23:113-115.

- Stubbings JM, Goodfield MJ. An unusual distribution of an acneiform rash due to herpes zoster infection. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1993;18:92-93.

- Shemer A, Weiss G, Trau H. Wolf’s isotopic response: a case of zosteriform lichen planus on the site of healed herpes zoster. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:445-447.

- Bang SW, Kim YK, Whang KU. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis: unilateral umbilicated papules along the lesions of herpes zoster. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:778-779.

- Paydaş S, Sahin B, Yavuz S, et al. Lymphomatous skin infiltration at the site of previous varicella zoster virus infection in a patient with T cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2000;37:229-232.

- Cerroni L, Kerl H. Cutaneous localization of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia at the site of varicella/herpes virus eruptions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:1022.

- Hudson CP, Hanno R, Callen JP. Cutaneous angiosarcoma in a site of healed herpes zoster. Int J Dermatol. 1984;23:404-407.

- Wyburn-Mason R. Visceral lesions in herpes zoster. Br Med J. 1957;1:678-681.

- Caroti A. Metastasi cutanee di a adenocarcinoma papillifero ovarico in sede di herpes zoster. Chron Dermatol. 1987;18:769-773.

- Kim MB, Jwa SW, Ko HC, et al. A case of secondary cutaneous mucinosis following herpes zoster: Wolf’s isotopic response. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:212-214.

- Burman KD, McKinley-Grant L. Dermatologic aspects of thyroid disease. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:247-255.

- Shekari AM, Ghiasi M, Ghasemi E, et al. Papulonodular mucinosis indicating systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:558-560.

- Dinneen AM, Dicken CH. Scleromyxedema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:37-43.

- Rongioletti F, Ghigliotti G, De Marchi R, et al. Cutaneous mucinoses and HIV infection. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:1077-1080.

- Krahl D, Hartschuh W, Tilgen W. Granuloma annulare perforans in herpes zoster scars. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:859-862.

- Wolf R, Lotti T, Ruocco V. Isomorphic versus isotopic response: data and hypotheses. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:123-125.

- Fisher G, Jaworski R. Granuloma formation in herpes zoster scars. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:1261-1263.

- Ruocco V, Grimaldi Filioli F. La risposta isotopica post-erpetica: possibile sequela di un locus minoris resistentiae acquisito. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 1999;134:547-552.

- Nikkels AF, Debrus S, Delvenne P, et al. Viral glycoproteins in herpesviridae granulomas. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16:588-592.

- Rongioletti F, Zaccaria E, Cozzani E, et al. Treatment of localized lichen myxedematosus of discrete type with tacrolimus ointment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;5:530-532.

- Kwon OS, Moon SE, Kim JA, et al. Lichen myxodematosus with rapid spontaneous regression. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:295-296.

Mucin is an amorphous gelatinous substance that is found in a large variety of tissues. There are 2 types of cutaneous mucin: dermal and epithelial. Both types appear as basophilic shreds and granules with hematoxylin and eosin stain.1 Epithelial mucin (sialomucin) is found mainly in the gastrointestinal tract and lungs. In the skin, it is present in the cytoplasm of the dark cells of the eccrine glands and in the apocrine secretory cells. Epithelial mucin contains both neutral and acid glycosaminoglycans, stains positive with Alcian blue (pH 2.5) and periodic acid–Schiff, is resistant to hyaluronidase, and does not stain metachromatically with toluidine blue. Dermal mucin is composed of acid glycosaminoglycans (eg, dermatan sulfate, chondroitin 6-sulfate, chondroitin 4-sulfate, hyaluronic acid) and normally is produced by dermal fibroblasts. Dermal mucin stains positive with Alcian blue (pH 2.5); is periodic acid–Schiff negative and sensitive to hyaluronidase; and shows metachromasia with toluidine blue, methylene blue, and thionine.

Cutaneous mucinosis comprises a heterogeneous group of skin disorders characterized by the deposition of mucin in the interstices of the dermis. These diseases may be classified as primary mucinosis with the mucin deposition as the main histologic feature resulting in clinically distinctive lesions and secondary mucinosis with the mucin deposition as an additional histologic finding within the context of an independent skin disease or lesion (eg, basal cell carcinoma) with deposits of mucin in the stroma. Primary cutaneous mucinosis may be subclassified into 2 groups: degenerative-inflammatory mucinoses and neoplastic-hamartomatous mucinoses. According to the histologic features, the degenerative-inflammatory mucinoses are better divided into dermal and follicular mucinoses.2 We describe a case of primary cutaneous dermal mucinosis on herpes zoster (HZ) scars as an isotopic response.

Case Report

A 33-year-old man presented to the dermatology department with slightly pruritic lesions on the left side of the chest and back that had appeared progressively at the site of HZ scars that had healed without treatment 9 months prior. Dermatologic examination revealed sharply defined whitish papules (Figure 1) measuring 2 to 4 mm in diameter with a smooth surface and linear distribution over the area of the left T8 and T9 dermatomes. The patient reported no postherpetic neuralgia and was otherwise healthy. Laboratory tests including a complete blood cell count, biochemistry, urinalysis, and determination of free thyroid hormones were within reference range. Serologic tests for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B and C viruses, and syphilis were negative. Antinuclear antibodies also were negative.

Histopathology demonstrated abundant bluish granular material between collagen bundles of the papillary dermis (Figure 2). No cytopathologic signs of active herpetic infection were seen. The Alcian blue stain at pH 2.5 was strongly positive for mucin, which confirmed the diagnosis of primary cutaneous dermal mucinosis.

Topical corticosteroids were applied for 2 months with no notable improvement. The lesions gradually improved without any other therapy during the subsequent 6 months.

Comment

The occurrence of a new skin disease at the exact site of a prior unrelated cutaneous disorder that had already resolved was first reported by Wyburn-Mason3 in 1955. Forty years later, the term isotopic response was coined by Wolf et al4 to describe this phenomenon. Diverse types of skin diseases such as herpes simplex virus,5 varicella-zoster infections,4 and thrombophlebitis4 have been implicated in cases of isotopic response, but the most frequently associated primary disorder by far is cutaneous HZ.

Several benign and malignant disorders may occur at sites of resolved HZ lesions, including granulomatous dermatitis,6 granuloma annulare,7 fungal granuloma,8 fungal folliculitis,9 psoriasis,10 morphea,11 lichen sclerosus,12 Kaposi sarcoma,13 the lichenoid variant of chronic graft-versus-host disease,14 cutaneous sarcoidosis,15 granulomatous folliculitis,16 comedones,17 furuncles,18 erythema annulare centrifugum,19 eosinophilic dermatosis,20 cutaneous pseudolymphoma,21 granulomatous vasculitis,22 Rosai-Dorfman disease,12 xanthomatous changes,23 tuberculoid granulomas,24 acneform eruption,25 lichen planus,26 acquired reactive perforating collagenosis,27 lymphoma,28 leukemia,29 angiosarcoma,30 basal cell carcinoma,31 squamous cell carcinoma, and cutaneous metastasis from internal carcinoma.32 The interval between the acute HZ episode and presentation of the second disease is quite variable, ranging from days to several months. Postzoster isotopic response has been described in individuals with varying degrees of immune response, affecting both immunocompetent12 and immunocompromised patients.14 There is no predilection for age, sex, or race. It also seems that antiviral treatment during the active episode does not prevent the development of secondary reactions.Kim et al33 reported a 59-year-old woman who developed flesh-colored or erythematous papules on HZ scars over the area of the left T1 and T2 dermatomes 1 week after the active viral process. Histopathologic study demonstrated deposition of mucin between collagen bundles in the dermis. The authors established the diagnosis of secondary cutaneous mucinosis as an isotopic response.33 Nevertheless, we believe that based on the aforementioned classification of cutaneous mucinosis,2 both this case and our case are better considered as primary cutaneous dermal mucinosis, as the mucin deposition in the dermis was the main histologic finding resulting in a distinctive cutaneous disorder. In the case reported by Kim et al,33 a possible relationship between cutaneous mucinosis and postherpetic neuralgia was suggested based on the slow regression of skin lesions in accordance with the improvement of the neuralgic pain; however, our patient did not have postherpetic neuralgia and the lesions persisted unchanged several months after the acute HZ episode. In the literature, there are reports of primary cutaneous dermal mucinosis associated with altered thyroid function34; autoimmune connective tissue diseases, mostly lupus erythematosus35; monoclonal gammopathy36; and human immunodeficiency virus infection,37 but these possibilities were ruled out in our patient by pertinent laboratory studies.

The pathogenesis of the postherpetic isotopic response remains unknown, but several mechanisms have been proposed. Some authors have suggested that postzoster dermatoses may represent isomorphic response of Köbner phenomenon.13,15 Although isomorphic and isotopic responses share some similarities, these terms describe 2 different phenomena: the first refers to the appearance of the same cutaneous disorder at a different site favored by trauma, while the second manifests a new and unrelated disease at the same location.38 Local anatomic changes such as altered microcirculation, collagen rearrangement, and an imperfect skin barrier may promote a prolonged local inflammatory response. Moreover, the destruction of nerve fibers by the varicella-zoster virus may indirectly influence the local immune system through the release of specific neuropeptides in the skin.39 It has been speculated that some secondary reactions may be the result of type III and type IV hypersensitivity reactions40 to viral antigens or to tissue antigens modified by the virus, inducing either immune hypersensitivity or local immune suppression.41 Some authors have documented the presence of varicella-zoster DNA within early postzoster lesions6,7 by using polymerase chain reaction in early lesions but not in late-stage and residual lesions.12,22 Nikkels et al42 studied early granulomatous lesions by immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization techniques and concluded that major viral envelope glycoproteins (glycoproteins I and II) rather than complete viral particles could be responsible for delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions. All these findings suggest that secondary reactions presenting on HZ scars are mainly the result of atypical immune reactions to local antigenic stimuli.

The pathogenesis of our case is unknown. From a theoretical point of view, it is possible that varicella-zoster virus may induce fibroblastic proliferation and mucin production on HZ scars; however, if HZ is a frequent process and the virus may induce mucin production, then focal dermal mucinosis in an HZ scar should be a common finding. In our patient, there was no associated disease favoring the development of the cutaneous mucinosis. These localized variants of primary cutaneous mucinosis usually do not require therapy, and a wait-and-see approach is recommended. Topical applications of corticosteroids, pimecrolimus, or tacrolimus, as well as oral isotretinoin, may have some benefit,43 but spontaneous resolution may occur.44 In our patient, topical corticosteroids were applied 2 months following initial presentation without any benefit and the cutaneous lesions gradually improved without any therapy during the subsequent 6 months. Focal dermal mucinosis should be added to the list of cutaneous reactions that may develop in HZ scars.

Mucin is an amorphous gelatinous substance that is found in a large variety of tissues. There are 2 types of cutaneous mucin: dermal and epithelial. Both types appear as basophilic shreds and granules with hematoxylin and eosin stain.1 Epithelial mucin (sialomucin) is found mainly in the gastrointestinal tract and lungs. In the skin, it is present in the cytoplasm of the dark cells of the eccrine glands and in the apocrine secretory cells. Epithelial mucin contains both neutral and acid glycosaminoglycans, stains positive with Alcian blue (pH 2.5) and periodic acid–Schiff, is resistant to hyaluronidase, and does not stain metachromatically with toluidine blue. Dermal mucin is composed of acid glycosaminoglycans (eg, dermatan sulfate, chondroitin 6-sulfate, chondroitin 4-sulfate, hyaluronic acid) and normally is produced by dermal fibroblasts. Dermal mucin stains positive with Alcian blue (pH 2.5); is periodic acid–Schiff negative and sensitive to hyaluronidase; and shows metachromasia with toluidine blue, methylene blue, and thionine.

Cutaneous mucinosis comprises a heterogeneous group of skin disorders characterized by the deposition of mucin in the interstices of the dermis. These diseases may be classified as primary mucinosis with the mucin deposition as the main histologic feature resulting in clinically distinctive lesions and secondary mucinosis with the mucin deposition as an additional histologic finding within the context of an independent skin disease or lesion (eg, basal cell carcinoma) with deposits of mucin in the stroma. Primary cutaneous mucinosis may be subclassified into 2 groups: degenerative-inflammatory mucinoses and neoplastic-hamartomatous mucinoses. According to the histologic features, the degenerative-inflammatory mucinoses are better divided into dermal and follicular mucinoses.2 We describe a case of primary cutaneous dermal mucinosis on herpes zoster (HZ) scars as an isotopic response.

Case Report

A 33-year-old man presented to the dermatology department with slightly pruritic lesions on the left side of the chest and back that had appeared progressively at the site of HZ scars that had healed without treatment 9 months prior. Dermatologic examination revealed sharply defined whitish papules (Figure 1) measuring 2 to 4 mm in diameter with a smooth surface and linear distribution over the area of the left T8 and T9 dermatomes. The patient reported no postherpetic neuralgia and was otherwise healthy. Laboratory tests including a complete blood cell count, biochemistry, urinalysis, and determination of free thyroid hormones were within reference range. Serologic tests for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B and C viruses, and syphilis were negative. Antinuclear antibodies also were negative.

Histopathology demonstrated abundant bluish granular material between collagen bundles of the papillary dermis (Figure 2). No cytopathologic signs of active herpetic infection were seen. The Alcian blue stain at pH 2.5 was strongly positive for mucin, which confirmed the diagnosis of primary cutaneous dermal mucinosis.

Topical corticosteroids were applied for 2 months with no notable improvement. The lesions gradually improved without any other therapy during the subsequent 6 months.

Comment

The occurrence of a new skin disease at the exact site of a prior unrelated cutaneous disorder that had already resolved was first reported by Wyburn-Mason3 in 1955. Forty years later, the term isotopic response was coined by Wolf et al4 to describe this phenomenon. Diverse types of skin diseases such as herpes simplex virus,5 varicella-zoster infections,4 and thrombophlebitis4 have been implicated in cases of isotopic response, but the most frequently associated primary disorder by far is cutaneous HZ.

Several benign and malignant disorders may occur at sites of resolved HZ lesions, including granulomatous dermatitis,6 granuloma annulare,7 fungal granuloma,8 fungal folliculitis,9 psoriasis,10 morphea,11 lichen sclerosus,12 Kaposi sarcoma,13 the lichenoid variant of chronic graft-versus-host disease,14 cutaneous sarcoidosis,15 granulomatous folliculitis,16 comedones,17 furuncles,18 erythema annulare centrifugum,19 eosinophilic dermatosis,20 cutaneous pseudolymphoma,21 granulomatous vasculitis,22 Rosai-Dorfman disease,12 xanthomatous changes,23 tuberculoid granulomas,24 acneform eruption,25 lichen planus,26 acquired reactive perforating collagenosis,27 lymphoma,28 leukemia,29 angiosarcoma,30 basal cell carcinoma,31 squamous cell carcinoma, and cutaneous metastasis from internal carcinoma.32 The interval between the acute HZ episode and presentation of the second disease is quite variable, ranging from days to several months. Postzoster isotopic response has been described in individuals with varying degrees of immune response, affecting both immunocompetent12 and immunocompromised patients.14 There is no predilection for age, sex, or race. It also seems that antiviral treatment during the active episode does not prevent the development of secondary reactions.Kim et al33 reported a 59-year-old woman who developed flesh-colored or erythematous papules on HZ scars over the area of the left T1 and T2 dermatomes 1 week after the active viral process. Histopathologic study demonstrated deposition of mucin between collagen bundles in the dermis. The authors established the diagnosis of secondary cutaneous mucinosis as an isotopic response.33 Nevertheless, we believe that based on the aforementioned classification of cutaneous mucinosis,2 both this case and our case are better considered as primary cutaneous dermal mucinosis, as the mucin deposition in the dermis was the main histologic finding resulting in a distinctive cutaneous disorder. In the case reported by Kim et al,33 a possible relationship between cutaneous mucinosis and postherpetic neuralgia was suggested based on the slow regression of skin lesions in accordance with the improvement of the neuralgic pain; however, our patient did not have postherpetic neuralgia and the lesions persisted unchanged several months after the acute HZ episode. In the literature, there are reports of primary cutaneous dermal mucinosis associated with altered thyroid function34; autoimmune connective tissue diseases, mostly lupus erythematosus35; monoclonal gammopathy36; and human immunodeficiency virus infection,37 but these possibilities were ruled out in our patient by pertinent laboratory studies.

The pathogenesis of the postherpetic isotopic response remains unknown, but several mechanisms have been proposed. Some authors have suggested that postzoster dermatoses may represent isomorphic response of Köbner phenomenon.13,15 Although isomorphic and isotopic responses share some similarities, these terms describe 2 different phenomena: the first refers to the appearance of the same cutaneous disorder at a different site favored by trauma, while the second manifests a new and unrelated disease at the same location.38 Local anatomic changes such as altered microcirculation, collagen rearrangement, and an imperfect skin barrier may promote a prolonged local inflammatory response. Moreover, the destruction of nerve fibers by the varicella-zoster virus may indirectly influence the local immune system through the release of specific neuropeptides in the skin.39 It has been speculated that some secondary reactions may be the result of type III and type IV hypersensitivity reactions40 to viral antigens or to tissue antigens modified by the virus, inducing either immune hypersensitivity or local immune suppression.41 Some authors have documented the presence of varicella-zoster DNA within early postzoster lesions6,7 by using polymerase chain reaction in early lesions but not in late-stage and residual lesions.12,22 Nikkels et al42 studied early granulomatous lesions by immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization techniques and concluded that major viral envelope glycoproteins (glycoproteins I and II) rather than complete viral particles could be responsible for delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions. All these findings suggest that secondary reactions presenting on HZ scars are mainly the result of atypical immune reactions to local antigenic stimuli.

The pathogenesis of our case is unknown. From a theoretical point of view, it is possible that varicella-zoster virus may induce fibroblastic proliferation and mucin production on HZ scars; however, if HZ is a frequent process and the virus may induce mucin production, then focal dermal mucinosis in an HZ scar should be a common finding. In our patient, there was no associated disease favoring the development of the cutaneous mucinosis. These localized variants of primary cutaneous mucinosis usually do not require therapy, and a wait-and-see approach is recommended. Topical applications of corticosteroids, pimecrolimus, or tacrolimus, as well as oral isotretinoin, may have some benefit,43 but spontaneous resolution may occur.44 In our patient, topical corticosteroids were applied 2 months following initial presentation without any benefit and the cutaneous lesions gradually improved without any therapy during the subsequent 6 months. Focal dermal mucinosis should be added to the list of cutaneous reactions that may develop in HZ scars.