User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Adult ADHD: Tips for an accurate diagnosis

With the diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) on the rise1 and a surge in prescriptions to treat the disorder leading to stimulant shortages,2 ensuring that patients are appropriately evaluated for ADHD is more critical than ever. ADHD is a clinical diagnosis that can be established by clinical interview, although the results of neuropsychological testing and collateral information from family members are helpful. Assessing adults for ADHD can be challenging when they appear to want to convince the clinician that they have the disorder. In this article, I provide tips to help you accurately diagnose ADHD in adult patients.

Use an ADHD symptom scale

An ADHD symptom checklist, such as the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale, is an effective tool to establish the presence of ADHD symptoms. A patient can complete this self-assessment tool before their visit, and you can use the results as a springboard to ask them about ADHD symptoms. It is important to elicit specific examples of the ADHD symptoms the patient reports, and to understand how these symptoms affect their functioning and quality of life.

Review the prescription drug monitoring program

Review your state’s prescription drug monitoring program to explore the patient’s prior and current prescriptions of stimulants and other controlled substances. Discern if, when, and by whom a patient was previously treated for ADHD, and rule out the rare possibility that the patient has obtained multiple prescriptions for controlled substances from multiple clinicians, which suggests the patient may have a substance use disorder.

Begin the assessment at your initial contact with the patient

How patients present on an initial screening call or how they compose emails can reveal clues about their level of organization and overall executive functioning. The way patients complete intake forms (eg, using a concise vs a meandering writing style) as well as their punctuality when presenting to appointments can also be telling.

Conduct a mental status examination

Patients can have difficulty focusing and completing tasks for reasons other than having ADHD. A mental status examination can sometimes provide objective clues that an individual has ADHD. A digressive thought process, visible physical restlessness, and instances of a patient interrupting the evaluator are suggestive of ADHD, although all these symptoms can be present in other conditions (eg, mania). However, signs of ADHD in the mental status examination do not confirm an ADHD diagnosis, nor does their absence rule it out.

Maintain an appropriate diagnostic threshold

Per DSM-5, an ADHD diagnosis requires that the symptoms cause a significant impairment in functioning.3 It is up to the clinician to determine if this threshold is met. It is imperative to thoughtfully consider this because stimulants are first-line treatment for ADHD and are commonly misused. Psychiatrists are usually motivated to please their patients in order to maintain them as patients and develop a positive therapeutic relationship, which improves outcomes.4 However, it is important to demonstrate integrity, provide an accurate diagnosis, and not be unduly swayed by a patient’s wish to receive an ADHD diagnosis. If you sense that a prospective patient is hoping they will receive an ADHD diagnosis and be prescribed a stimulant, it may be prudent to emphasize that the patient will be assessed for multiple mental health conditions, including ADHD, and that treatment will depend on the outcome of the evaluation.

1. Chung W, Jiang SF, Paksarian D, et al. Trends in the prevalence and incidence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among adults and children of different racial and ethnic groups. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(11):e1914344. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.14344

2. Danielson ML, Bohm MK, Newsome K, et al. Trends in stimulant prescription fills among commercially insured children and adults - United States, 2016-2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(13):327-332. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7213a1

3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013:59-63.

4. Totura CMW, Fields SA, Karver MS. The role of the therapeutic relationship in psychopharmacological treatment outcomes: a meta-analytic review. Pyschiatr Serv. 2018;69(1):41-47. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201700114

With the diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) on the rise1 and a surge in prescriptions to treat the disorder leading to stimulant shortages,2 ensuring that patients are appropriately evaluated for ADHD is more critical than ever. ADHD is a clinical diagnosis that can be established by clinical interview, although the results of neuropsychological testing and collateral information from family members are helpful. Assessing adults for ADHD can be challenging when they appear to want to convince the clinician that they have the disorder. In this article, I provide tips to help you accurately diagnose ADHD in adult patients.

Use an ADHD symptom scale

An ADHD symptom checklist, such as the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale, is an effective tool to establish the presence of ADHD symptoms. A patient can complete this self-assessment tool before their visit, and you can use the results as a springboard to ask them about ADHD symptoms. It is important to elicit specific examples of the ADHD symptoms the patient reports, and to understand how these symptoms affect their functioning and quality of life.

Review the prescription drug monitoring program

Review your state’s prescription drug monitoring program to explore the patient’s prior and current prescriptions of stimulants and other controlled substances. Discern if, when, and by whom a patient was previously treated for ADHD, and rule out the rare possibility that the patient has obtained multiple prescriptions for controlled substances from multiple clinicians, which suggests the patient may have a substance use disorder.

Begin the assessment at your initial contact with the patient

How patients present on an initial screening call or how they compose emails can reveal clues about their level of organization and overall executive functioning. The way patients complete intake forms (eg, using a concise vs a meandering writing style) as well as their punctuality when presenting to appointments can also be telling.

Conduct a mental status examination

Patients can have difficulty focusing and completing tasks for reasons other than having ADHD. A mental status examination can sometimes provide objective clues that an individual has ADHD. A digressive thought process, visible physical restlessness, and instances of a patient interrupting the evaluator are suggestive of ADHD, although all these symptoms can be present in other conditions (eg, mania). However, signs of ADHD in the mental status examination do not confirm an ADHD diagnosis, nor does their absence rule it out.

Maintain an appropriate diagnostic threshold

Per DSM-5, an ADHD diagnosis requires that the symptoms cause a significant impairment in functioning.3 It is up to the clinician to determine if this threshold is met. It is imperative to thoughtfully consider this because stimulants are first-line treatment for ADHD and are commonly misused. Psychiatrists are usually motivated to please their patients in order to maintain them as patients and develop a positive therapeutic relationship, which improves outcomes.4 However, it is important to demonstrate integrity, provide an accurate diagnosis, and not be unduly swayed by a patient’s wish to receive an ADHD diagnosis. If you sense that a prospective patient is hoping they will receive an ADHD diagnosis and be prescribed a stimulant, it may be prudent to emphasize that the patient will be assessed for multiple mental health conditions, including ADHD, and that treatment will depend on the outcome of the evaluation.

With the diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) on the rise1 and a surge in prescriptions to treat the disorder leading to stimulant shortages,2 ensuring that patients are appropriately evaluated for ADHD is more critical than ever. ADHD is a clinical diagnosis that can be established by clinical interview, although the results of neuropsychological testing and collateral information from family members are helpful. Assessing adults for ADHD can be challenging when they appear to want to convince the clinician that they have the disorder. In this article, I provide tips to help you accurately diagnose ADHD in adult patients.

Use an ADHD symptom scale

An ADHD symptom checklist, such as the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale, is an effective tool to establish the presence of ADHD symptoms. A patient can complete this self-assessment tool before their visit, and you can use the results as a springboard to ask them about ADHD symptoms. It is important to elicit specific examples of the ADHD symptoms the patient reports, and to understand how these symptoms affect their functioning and quality of life.

Review the prescription drug monitoring program

Review your state’s prescription drug monitoring program to explore the patient’s prior and current prescriptions of stimulants and other controlled substances. Discern if, when, and by whom a patient was previously treated for ADHD, and rule out the rare possibility that the patient has obtained multiple prescriptions for controlled substances from multiple clinicians, which suggests the patient may have a substance use disorder.

Begin the assessment at your initial contact with the patient

How patients present on an initial screening call or how they compose emails can reveal clues about their level of organization and overall executive functioning. The way patients complete intake forms (eg, using a concise vs a meandering writing style) as well as their punctuality when presenting to appointments can also be telling.

Conduct a mental status examination

Patients can have difficulty focusing and completing tasks for reasons other than having ADHD. A mental status examination can sometimes provide objective clues that an individual has ADHD. A digressive thought process, visible physical restlessness, and instances of a patient interrupting the evaluator are suggestive of ADHD, although all these symptoms can be present in other conditions (eg, mania). However, signs of ADHD in the mental status examination do not confirm an ADHD diagnosis, nor does their absence rule it out.

Maintain an appropriate diagnostic threshold

Per DSM-5, an ADHD diagnosis requires that the symptoms cause a significant impairment in functioning.3 It is up to the clinician to determine if this threshold is met. It is imperative to thoughtfully consider this because stimulants are first-line treatment for ADHD and are commonly misused. Psychiatrists are usually motivated to please their patients in order to maintain them as patients and develop a positive therapeutic relationship, which improves outcomes.4 However, it is important to demonstrate integrity, provide an accurate diagnosis, and not be unduly swayed by a patient’s wish to receive an ADHD diagnosis. If you sense that a prospective patient is hoping they will receive an ADHD diagnosis and be prescribed a stimulant, it may be prudent to emphasize that the patient will be assessed for multiple mental health conditions, including ADHD, and that treatment will depend on the outcome of the evaluation.

1. Chung W, Jiang SF, Paksarian D, et al. Trends in the prevalence and incidence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among adults and children of different racial and ethnic groups. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(11):e1914344. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.14344

2. Danielson ML, Bohm MK, Newsome K, et al. Trends in stimulant prescription fills among commercially insured children and adults - United States, 2016-2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(13):327-332. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7213a1

3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013:59-63.

4. Totura CMW, Fields SA, Karver MS. The role of the therapeutic relationship in psychopharmacological treatment outcomes: a meta-analytic review. Pyschiatr Serv. 2018;69(1):41-47. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201700114

1. Chung W, Jiang SF, Paksarian D, et al. Trends in the prevalence and incidence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among adults and children of different racial and ethnic groups. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(11):e1914344. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.14344

2. Danielson ML, Bohm MK, Newsome K, et al. Trends in stimulant prescription fills among commercially insured children and adults - United States, 2016-2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(13):327-332. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7213a1

3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013:59-63.

4. Totura CMW, Fields SA, Karver MS. The role of the therapeutic relationship in psychopharmacological treatment outcomes: a meta-analytic review. Pyschiatr Serv. 2018;69(1):41-47. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201700114

Childbirth-related PTSD: How it differs and who’s at risk

Childbirth-related posttraumatic stress disorder (CB-PTSD) is a form of PTSD that can develop related to trauma surrounding the events of giving birth. It affects approximately 5% of women after any birth, which is similar to the rate of PTSD after experiencing a natural disaster.1 Up to 17% of women may have posttraumatic symptoms in the postpartum period.1 Despite the high prevalence of CB-PTSD, many psychiatric clinicians have not incorporated screening for and management of CB-PTSD into their practice.

This is partly because childbirth has been conceptualized as a “stressful but positive life event.”2 Historically, childbirth was not recognized as a traumatic event; for example, in DSM-III-R, the criteria for trauma in PTSD required an event outside the range of usual human experience, and childbirth was implicitly excluded as being too common to be traumatic. In the past decade, this clinical phenomenon has been more formally recognized and studied.2

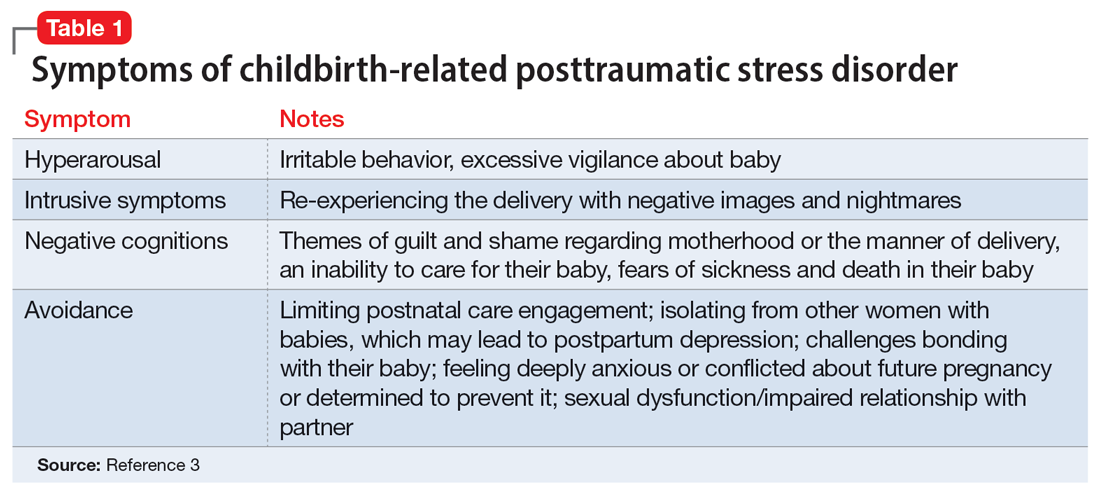

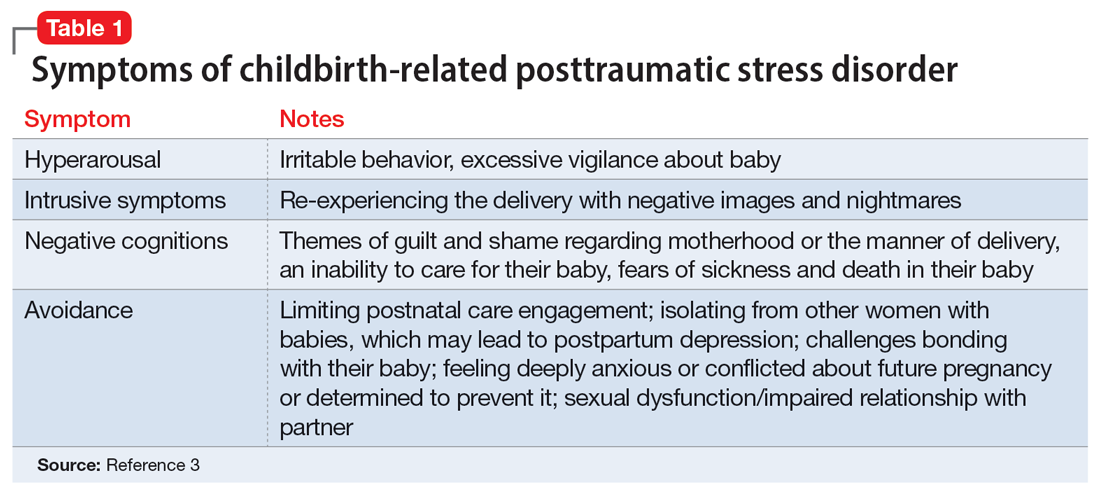

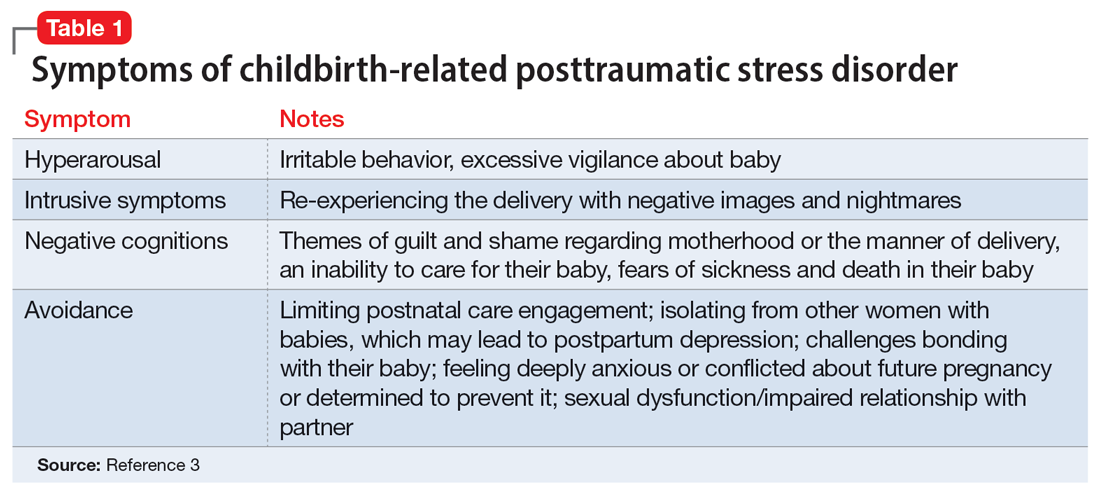

CB-PTSD presents with symptoms similar to those of other forms of PTSD, with some nuances, as outlined in Table 1.3 Avoidance can be the predominant symptom; this can affect mothers’ engagement in postnatal care and is a major risk factor for postpartum depression.3

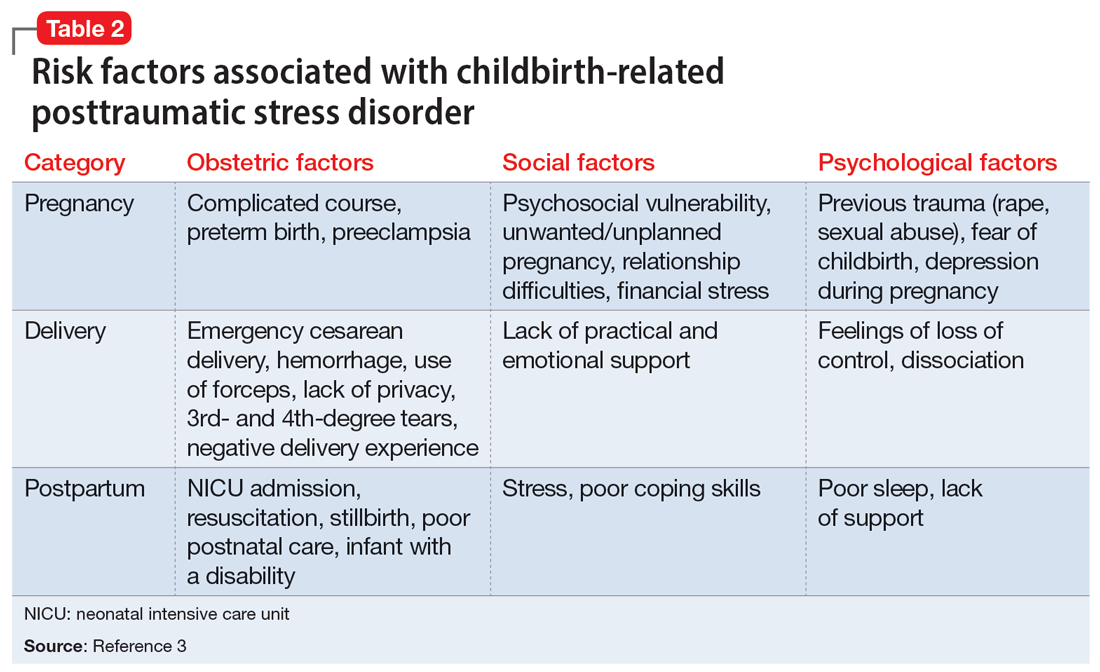

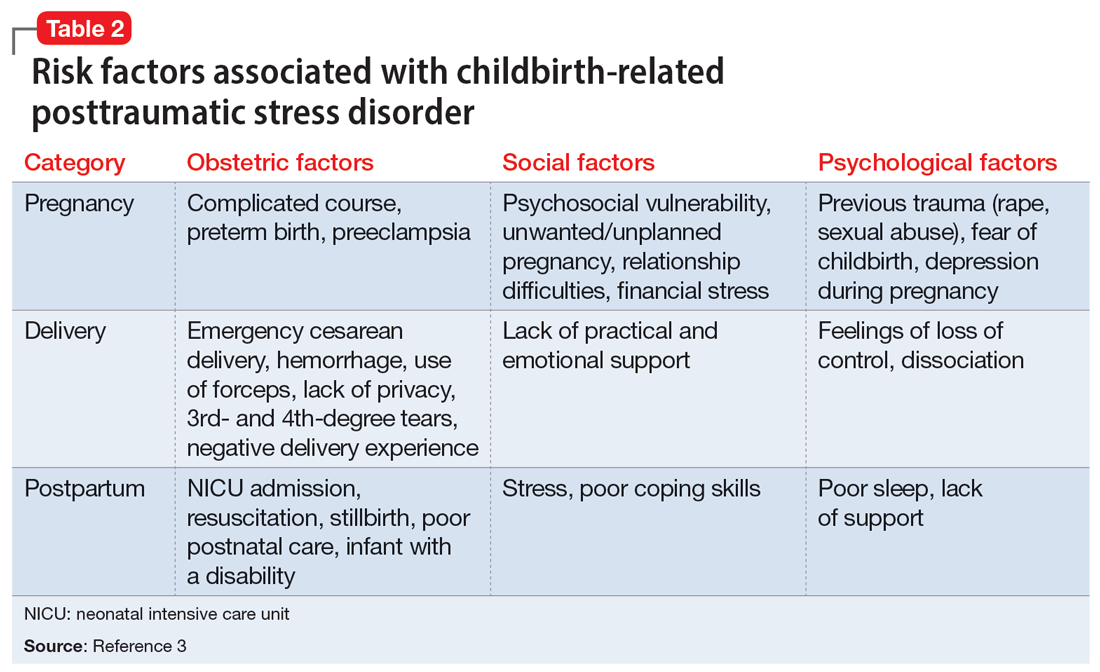

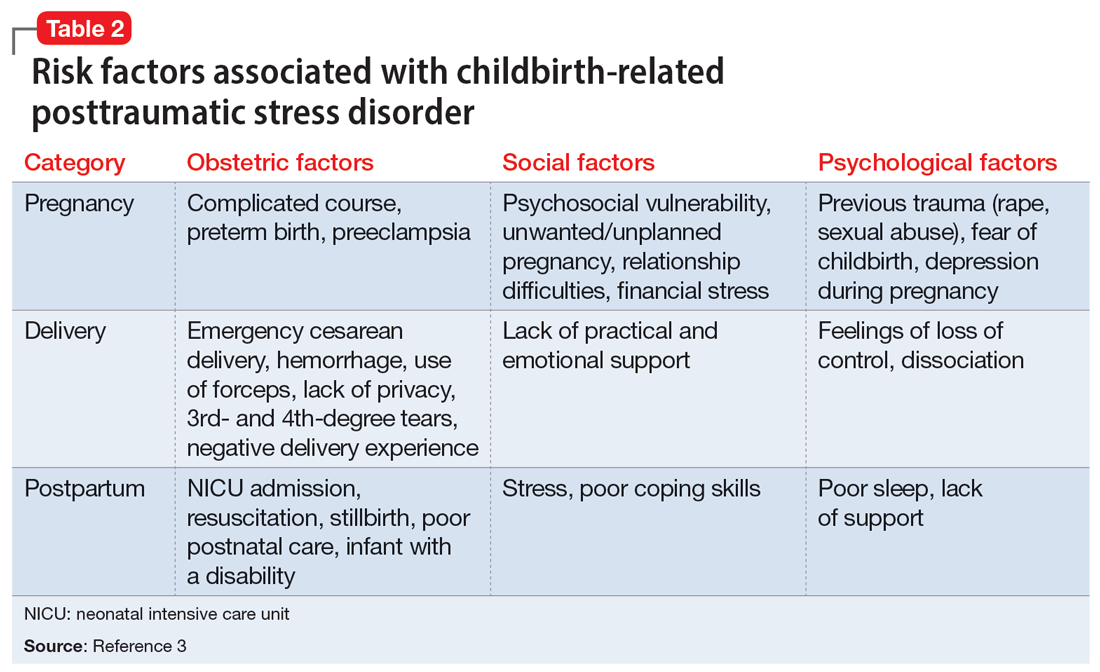

Many risk factors in the peripartum period can impact the development of CB-PTSD (Table 23). The most significant risk factor is whether the patient views the delivery of their baby as a subjectively negative experience, regardless of the presence or lack of peripartum complications.1 However, parents of infants who require treatment in a neonatal intensive care unit and women who require emergency medical treatment following delivery are at higher risk.

Screening and treatment

Ideally, every woman should be screened for CB-PTSD by their psychiatrist or obstetrician during a postpartum visit at least 1 month after delivery. In particular, high-risk populations and women with subjectively negative birth experiences should be screened, as well as women with postpartum depression that may have been precipitated or perpetuated by a traumatic experience. The City Birth Trauma Scale is a free 31-item self-report scale that can be used for such screening. It addresses both general and birth-related symptoms and is validated in multiple languages.4

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and prazosin may be helpful for symptomatic treatment of CB-PTSD. Ongoing research studying the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing for CB-PTSD has yielded promising results but is limited in its generalizability.

Many women who develop CB-PTSD choose to get pregnant again. Psychiatrists can apply the principles of trauma-informed care and collaborate with obstetric and pediatric physicians to reduce the risk of retraumatization. It is critical to identify at-risk women and educate and prepare them for their next delivery experience. By focusing on communication, informed consent, and emotional support, we can do our best to prevent the recurrence of CB-PTSD.

1. Dekel S, Stuebe C, Dishy G. Childbirth induced posttraumatic stress syndrome: a systematic review of prevalence and risk factors. Front Psych. 2017;8:560. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00560

2. Horesh D, Garthus-Niegel S, Horsch A. Childbirth-related PTSD: is it a unique post-traumatic disorder? J Reprod Infant Psych. 2021;39(3):221-224. doi:10.1080/02646838.2021.1930739

3. Kranenburg L, Lambregtse-van den Berg M, Stramrood C. Traumatic childbirth experience and childbirth-related post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): a contemporary overview. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(4):2775. doi:10.3390/ijerph20042775

4. Ayers S, Wright DB, Thornton A. Development of a measure of postpartum PTSD: The City Birth Trauma Scale. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:409. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00409

Childbirth-related posttraumatic stress disorder (CB-PTSD) is a form of PTSD that can develop related to trauma surrounding the events of giving birth. It affects approximately 5% of women after any birth, which is similar to the rate of PTSD after experiencing a natural disaster.1 Up to 17% of women may have posttraumatic symptoms in the postpartum period.1 Despite the high prevalence of CB-PTSD, many psychiatric clinicians have not incorporated screening for and management of CB-PTSD into their practice.

This is partly because childbirth has been conceptualized as a “stressful but positive life event.”2 Historically, childbirth was not recognized as a traumatic event; for example, in DSM-III-R, the criteria for trauma in PTSD required an event outside the range of usual human experience, and childbirth was implicitly excluded as being too common to be traumatic. In the past decade, this clinical phenomenon has been more formally recognized and studied.2

CB-PTSD presents with symptoms similar to those of other forms of PTSD, with some nuances, as outlined in Table 1.3 Avoidance can be the predominant symptom; this can affect mothers’ engagement in postnatal care and is a major risk factor for postpartum depression.3

Many risk factors in the peripartum period can impact the development of CB-PTSD (Table 23). The most significant risk factor is whether the patient views the delivery of their baby as a subjectively negative experience, regardless of the presence or lack of peripartum complications.1 However, parents of infants who require treatment in a neonatal intensive care unit and women who require emergency medical treatment following delivery are at higher risk.

Screening and treatment

Ideally, every woman should be screened for CB-PTSD by their psychiatrist or obstetrician during a postpartum visit at least 1 month after delivery. In particular, high-risk populations and women with subjectively negative birth experiences should be screened, as well as women with postpartum depression that may have been precipitated or perpetuated by a traumatic experience. The City Birth Trauma Scale is a free 31-item self-report scale that can be used for such screening. It addresses both general and birth-related symptoms and is validated in multiple languages.4

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and prazosin may be helpful for symptomatic treatment of CB-PTSD. Ongoing research studying the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing for CB-PTSD has yielded promising results but is limited in its generalizability.

Many women who develop CB-PTSD choose to get pregnant again. Psychiatrists can apply the principles of trauma-informed care and collaborate with obstetric and pediatric physicians to reduce the risk of retraumatization. It is critical to identify at-risk women and educate and prepare them for their next delivery experience. By focusing on communication, informed consent, and emotional support, we can do our best to prevent the recurrence of CB-PTSD.

Childbirth-related posttraumatic stress disorder (CB-PTSD) is a form of PTSD that can develop related to trauma surrounding the events of giving birth. It affects approximately 5% of women after any birth, which is similar to the rate of PTSD after experiencing a natural disaster.1 Up to 17% of women may have posttraumatic symptoms in the postpartum period.1 Despite the high prevalence of CB-PTSD, many psychiatric clinicians have not incorporated screening for and management of CB-PTSD into their practice.

This is partly because childbirth has been conceptualized as a “stressful but positive life event.”2 Historically, childbirth was not recognized as a traumatic event; for example, in DSM-III-R, the criteria for trauma in PTSD required an event outside the range of usual human experience, and childbirth was implicitly excluded as being too common to be traumatic. In the past decade, this clinical phenomenon has been more formally recognized and studied.2

CB-PTSD presents with symptoms similar to those of other forms of PTSD, with some nuances, as outlined in Table 1.3 Avoidance can be the predominant symptom; this can affect mothers’ engagement in postnatal care and is a major risk factor for postpartum depression.3

Many risk factors in the peripartum period can impact the development of CB-PTSD (Table 23). The most significant risk factor is whether the patient views the delivery of their baby as a subjectively negative experience, regardless of the presence or lack of peripartum complications.1 However, parents of infants who require treatment in a neonatal intensive care unit and women who require emergency medical treatment following delivery are at higher risk.

Screening and treatment

Ideally, every woman should be screened for CB-PTSD by their psychiatrist or obstetrician during a postpartum visit at least 1 month after delivery. In particular, high-risk populations and women with subjectively negative birth experiences should be screened, as well as women with postpartum depression that may have been precipitated or perpetuated by a traumatic experience. The City Birth Trauma Scale is a free 31-item self-report scale that can be used for such screening. It addresses both general and birth-related symptoms and is validated in multiple languages.4

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and prazosin may be helpful for symptomatic treatment of CB-PTSD. Ongoing research studying the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing for CB-PTSD has yielded promising results but is limited in its generalizability.

Many women who develop CB-PTSD choose to get pregnant again. Psychiatrists can apply the principles of trauma-informed care and collaborate with obstetric and pediatric physicians to reduce the risk of retraumatization. It is critical to identify at-risk women and educate and prepare them for their next delivery experience. By focusing on communication, informed consent, and emotional support, we can do our best to prevent the recurrence of CB-PTSD.

1. Dekel S, Stuebe C, Dishy G. Childbirth induced posttraumatic stress syndrome: a systematic review of prevalence and risk factors. Front Psych. 2017;8:560. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00560

2. Horesh D, Garthus-Niegel S, Horsch A. Childbirth-related PTSD: is it a unique post-traumatic disorder? J Reprod Infant Psych. 2021;39(3):221-224. doi:10.1080/02646838.2021.1930739

3. Kranenburg L, Lambregtse-van den Berg M, Stramrood C. Traumatic childbirth experience and childbirth-related post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): a contemporary overview. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(4):2775. doi:10.3390/ijerph20042775

4. Ayers S, Wright DB, Thornton A. Development of a measure of postpartum PTSD: The City Birth Trauma Scale. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:409. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00409

1. Dekel S, Stuebe C, Dishy G. Childbirth induced posttraumatic stress syndrome: a systematic review of prevalence and risk factors. Front Psych. 2017;8:560. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00560

2. Horesh D, Garthus-Niegel S, Horsch A. Childbirth-related PTSD: is it a unique post-traumatic disorder? J Reprod Infant Psych. 2021;39(3):221-224. doi:10.1080/02646838.2021.1930739

3. Kranenburg L, Lambregtse-van den Berg M, Stramrood C. Traumatic childbirth experience and childbirth-related post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): a contemporary overview. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(4):2775. doi:10.3390/ijerph20042775

4. Ayers S, Wright DB, Thornton A. Development of a measure of postpartum PTSD: The City Birth Trauma Scale. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:409. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00409

Perinatal psychiatric screening: What to ask

Perinatal psychiatry focuses on the evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment of mental health disorders during the preconception, pregnancy, and postpartum periods. Mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and posttraumatic stress disorder are the most common mental health conditions that arise during the perinatal period.1 Mediating factors include hormone fluctuations, sleep deprivation, trauma exposure, financial stress, having a history of psychiatric illness, and factors related to newborn care.

During the perinatal period, a comprehensive psychiatric interview is crucial. Effective screening and identification of maternal mental health conditions necessitate more than merely checking off boxes on a questionnaire. It requires compassionate, informed, and individualized conversations between physicians and their patients.

In addition to asking about pertinent positive and negative psychiatric symptoms, the following screening questions could be asked during a structured interview to identify perinatal issues during pregnancy and the postpartum period.

During pregnancy

- How do you feel about your pregnancy?

- Was this pregnancy planned or unplanned, desired or not?

- Was fertility treatment needed or used?

- Did you think about stopping the pregnancy? If so, was your decision influenced by laws that restrict abortion in your state?

- Do you feel connected to the fetus?

- Do you have a room or crib at home for the baby? A car seat? Clothing? Baby supplies?

- Are you planning on breastfeeding?

- Do you have thoughts on future desired fertility and/or contraception?

- Who is your support system at home?

- How is your relationship with the baby’s father?

- How is the baby’s father’s mental well-being?

- Have you been subject to any abuse, intimate partner violence, or neglect?

- Are your other children being taken care of properly? What is the plan for them during delivery days at the hospital?

During the postpartum period

- Was your baby born prematurely?

- Did you have a vaginal or cesarean delivery?

- Did you encounter any delivery complications?

- Did you see the baby after the delivery?

- Do you feel connected to or able to bond with the baby?

- Do you have access to maternity leave from work?

- Have you had scary or upsetting thoughts about hurting your baby?

- Do you have any concerns about your treatment plan, such as medication use?

- In case of an emergency, are you aware of perinatal psychiatry resources in your area or the national maternal mental health hotline (833-852-6262)?

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists clinical practice guidelines recommend that clinicians conduct depression and anxiety screening at least once during the perinatal period by using a standardized, validated tool.2 Psychiatry residents should receive adequate guidance and education about perinatal psychiatric evaluation, risk assessment, and treatment counseling. Early detection of mental health symptoms allows for early referral, close surveillance during episodes of vulnerability, and better access to mental health care during the perinatal period.

1. Howard LM, Khalifeh H. Perinatal mental health: a review of progress and challenges. World Psychiatry. 2020;19(3):313-327. doi:10.1002/wps.20769

2. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Screening and diagnosis of mental health conditions during pregnancy and postpartum. Clinical Practice Guideline Number 4. June 2023. Accessed November 3, 2023. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/clinical-practice-guideline/articles/2023/06/screening-and-diagnosis-of-mental-health-conditions-during-pregnancy-and-postpartum

Perinatal psychiatry focuses on the evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment of mental health disorders during the preconception, pregnancy, and postpartum periods. Mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and posttraumatic stress disorder are the most common mental health conditions that arise during the perinatal period.1 Mediating factors include hormone fluctuations, sleep deprivation, trauma exposure, financial stress, having a history of psychiatric illness, and factors related to newborn care.

During the perinatal period, a comprehensive psychiatric interview is crucial. Effective screening and identification of maternal mental health conditions necessitate more than merely checking off boxes on a questionnaire. It requires compassionate, informed, and individualized conversations between physicians and their patients.

In addition to asking about pertinent positive and negative psychiatric symptoms, the following screening questions could be asked during a structured interview to identify perinatal issues during pregnancy and the postpartum period.

During pregnancy

- How do you feel about your pregnancy?

- Was this pregnancy planned or unplanned, desired or not?

- Was fertility treatment needed or used?

- Did you think about stopping the pregnancy? If so, was your decision influenced by laws that restrict abortion in your state?

- Do you feel connected to the fetus?

- Do you have a room or crib at home for the baby? A car seat? Clothing? Baby supplies?

- Are you planning on breastfeeding?

- Do you have thoughts on future desired fertility and/or contraception?

- Who is your support system at home?

- How is your relationship with the baby’s father?

- How is the baby’s father’s mental well-being?

- Have you been subject to any abuse, intimate partner violence, or neglect?

- Are your other children being taken care of properly? What is the plan for them during delivery days at the hospital?

During the postpartum period

- Was your baby born prematurely?

- Did you have a vaginal or cesarean delivery?

- Did you encounter any delivery complications?

- Did you see the baby after the delivery?

- Do you feel connected to or able to bond with the baby?

- Do you have access to maternity leave from work?

- Have you had scary or upsetting thoughts about hurting your baby?

- Do you have any concerns about your treatment plan, such as medication use?

- In case of an emergency, are you aware of perinatal psychiatry resources in your area or the national maternal mental health hotline (833-852-6262)?

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists clinical practice guidelines recommend that clinicians conduct depression and anxiety screening at least once during the perinatal period by using a standardized, validated tool.2 Psychiatry residents should receive adequate guidance and education about perinatal psychiatric evaluation, risk assessment, and treatment counseling. Early detection of mental health symptoms allows for early referral, close surveillance during episodes of vulnerability, and better access to mental health care during the perinatal period.

Perinatal psychiatry focuses on the evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment of mental health disorders during the preconception, pregnancy, and postpartum periods. Mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and posttraumatic stress disorder are the most common mental health conditions that arise during the perinatal period.1 Mediating factors include hormone fluctuations, sleep deprivation, trauma exposure, financial stress, having a history of psychiatric illness, and factors related to newborn care.

During the perinatal period, a comprehensive psychiatric interview is crucial. Effective screening and identification of maternal mental health conditions necessitate more than merely checking off boxes on a questionnaire. It requires compassionate, informed, and individualized conversations between physicians and their patients.

In addition to asking about pertinent positive and negative psychiatric symptoms, the following screening questions could be asked during a structured interview to identify perinatal issues during pregnancy and the postpartum period.

During pregnancy

- How do you feel about your pregnancy?

- Was this pregnancy planned or unplanned, desired or not?

- Was fertility treatment needed or used?

- Did you think about stopping the pregnancy? If so, was your decision influenced by laws that restrict abortion in your state?

- Do you feel connected to the fetus?

- Do you have a room or crib at home for the baby? A car seat? Clothing? Baby supplies?

- Are you planning on breastfeeding?

- Do you have thoughts on future desired fertility and/or contraception?

- Who is your support system at home?

- How is your relationship with the baby’s father?

- How is the baby’s father’s mental well-being?

- Have you been subject to any abuse, intimate partner violence, or neglect?

- Are your other children being taken care of properly? What is the plan for them during delivery days at the hospital?

During the postpartum period

- Was your baby born prematurely?

- Did you have a vaginal or cesarean delivery?

- Did you encounter any delivery complications?

- Did you see the baby after the delivery?

- Do you feel connected to or able to bond with the baby?

- Do you have access to maternity leave from work?

- Have you had scary or upsetting thoughts about hurting your baby?

- Do you have any concerns about your treatment plan, such as medication use?

- In case of an emergency, are you aware of perinatal psychiatry resources in your area or the national maternal mental health hotline (833-852-6262)?

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists clinical practice guidelines recommend that clinicians conduct depression and anxiety screening at least once during the perinatal period by using a standardized, validated tool.2 Psychiatry residents should receive adequate guidance and education about perinatal psychiatric evaluation, risk assessment, and treatment counseling. Early detection of mental health symptoms allows for early referral, close surveillance during episodes of vulnerability, and better access to mental health care during the perinatal period.

1. Howard LM, Khalifeh H. Perinatal mental health: a review of progress and challenges. World Psychiatry. 2020;19(3):313-327. doi:10.1002/wps.20769

2. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Screening and diagnosis of mental health conditions during pregnancy and postpartum. Clinical Practice Guideline Number 4. June 2023. Accessed November 3, 2023. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/clinical-practice-guideline/articles/2023/06/screening-and-diagnosis-of-mental-health-conditions-during-pregnancy-and-postpartum

1. Howard LM, Khalifeh H. Perinatal mental health: a review of progress and challenges. World Psychiatry. 2020;19(3):313-327. doi:10.1002/wps.20769

2. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Screening and diagnosis of mental health conditions during pregnancy and postpartum. Clinical Practice Guideline Number 4. June 2023. Accessed November 3, 2023. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/clinical-practice-guideline/articles/2023/06/screening-and-diagnosis-of-mental-health-conditions-during-pregnancy-and-postpartum

Brick and mortar: Changes in the therapeutic relationship in a postvirtual world

My colleagues and I entered the realm of outpatient psychiatry during residency at a logistically and dynamically interesting time. At the beginning of our third year in training (July 2022), almost all of the outpatients we were treating were still being seen virtually. For much of the year, they remained that way. However, with the reinstatement of the Ryan Haight Act in May 2023, I began to meet patients in person for the first time—the same patients whom I had known only virtually for the first 10 months of our therapeutic relationship. I observed vast changes in the dynamic of the room; many of these patients opened up more in their first in-person session than they had all year over Zoom.

Once in-person sessions resumed, patients who during virtual visits had assured me for almost a year that their home situation was optimized had a plethora of new things to share about their seemingly straightforward living situations. Relationships that appeared stable had more layers to reveal once the half of the relationship I was treating was now comfortably seated within the walls of my office. Problems that had previously seemed biologically based suddenly had complex sociocultural elements that were divulged for the first time. Some patients felt freer to be unrestricted in their affect, in contrast to the logistical (and metaphorical) buttoned-up virtual environment. Emotions ranged from cathartic (“It’s so great to see you in person!”) to bemused (“You’re taller/shorter, older/younger than I thought!”). The screen was gone, and the tangibility of it all breathed a different air into the room.

Virtual vs in-person: Crabs on a beach

The virtual treatment space could be envisioned as crabs in shells scattered on a beach, in which 2 crabs situated in their own shells, not necessarily adjacent to each other, could communicate. This certainly had benefits, such as the convenience of not having to move to another shell, as well as the brief but telling opportunity to gaze into their home shell environment. However, sometimes there would be disadvantages, such as interference with the connection due to static in the sand; at other times, there was the potential for other crabs to overhear and inadvertently learn of each other’s presence, thus affecting the openness of the communication. In this analogy, perhaps the equivalent of an in-person meeting would be 1 crab meandering over and the 2 crabs cohabiting a conch for the first time—it’s spacious (enough), all-enveloping, and within the harkened privacy of a shared sacred space.

A unique training experience

My co-residents and I are uniquely positioned to observe this novel phenomenon due to the timing of having entered our outpatient psychiatry training during the COVID-19 pandemic. Previous generations of residents—as well as practicing psychiatrists who had initially met their patients in person and were forced to switch to virtual sessions during the pandemic—had certain perspectives and challenges of their own, but they had a known dynamic of in-person interactions at baseline. Accordingly, residents who practiced peak- and mid-pandemic and graduated without being required to treat patients face-to-face (the classes of 2022 and 2023) might have spent entire therapeutic relationships having never met their patients in person. My class (2024) was situated in this time- and situation-bound frame in which we started virtually, and by requirements of the law, later met our patients in person. Being not only an observer but an active participant in a treatment dyad within the context of this phenomenon taught me astutely about transference, countertransference, and the holding environment. Training in psychodynamic psychotherapy has taught me about the act of listening deeply and qualities of therapeutic communication. Having the opportunity to enact these principles in such a dichotomy of treatment settings has been invaluable in my education, in getting to know different facets of my patients, and in understanding the nuances of the human experience.

My colleagues and I entered the realm of outpatient psychiatry during residency at a logistically and dynamically interesting time. At the beginning of our third year in training (July 2022), almost all of the outpatients we were treating were still being seen virtually. For much of the year, they remained that way. However, with the reinstatement of the Ryan Haight Act in May 2023, I began to meet patients in person for the first time—the same patients whom I had known only virtually for the first 10 months of our therapeutic relationship. I observed vast changes in the dynamic of the room; many of these patients opened up more in their first in-person session than they had all year over Zoom.

Once in-person sessions resumed, patients who during virtual visits had assured me for almost a year that their home situation was optimized had a plethora of new things to share about their seemingly straightforward living situations. Relationships that appeared stable had more layers to reveal once the half of the relationship I was treating was now comfortably seated within the walls of my office. Problems that had previously seemed biologically based suddenly had complex sociocultural elements that were divulged for the first time. Some patients felt freer to be unrestricted in their affect, in contrast to the logistical (and metaphorical) buttoned-up virtual environment. Emotions ranged from cathartic (“It’s so great to see you in person!”) to bemused (“You’re taller/shorter, older/younger than I thought!”). The screen was gone, and the tangibility of it all breathed a different air into the room.

Virtual vs in-person: Crabs on a beach

The virtual treatment space could be envisioned as crabs in shells scattered on a beach, in which 2 crabs situated in their own shells, not necessarily adjacent to each other, could communicate. This certainly had benefits, such as the convenience of not having to move to another shell, as well as the brief but telling opportunity to gaze into their home shell environment. However, sometimes there would be disadvantages, such as interference with the connection due to static in the sand; at other times, there was the potential for other crabs to overhear and inadvertently learn of each other’s presence, thus affecting the openness of the communication. In this analogy, perhaps the equivalent of an in-person meeting would be 1 crab meandering over and the 2 crabs cohabiting a conch for the first time—it’s spacious (enough), all-enveloping, and within the harkened privacy of a shared sacred space.

A unique training experience

My co-residents and I are uniquely positioned to observe this novel phenomenon due to the timing of having entered our outpatient psychiatry training during the COVID-19 pandemic. Previous generations of residents—as well as practicing psychiatrists who had initially met their patients in person and were forced to switch to virtual sessions during the pandemic—had certain perspectives and challenges of their own, but they had a known dynamic of in-person interactions at baseline. Accordingly, residents who practiced peak- and mid-pandemic and graduated without being required to treat patients face-to-face (the classes of 2022 and 2023) might have spent entire therapeutic relationships having never met their patients in person. My class (2024) was situated in this time- and situation-bound frame in which we started virtually, and by requirements of the law, later met our patients in person. Being not only an observer but an active participant in a treatment dyad within the context of this phenomenon taught me astutely about transference, countertransference, and the holding environment. Training in psychodynamic psychotherapy has taught me about the act of listening deeply and qualities of therapeutic communication. Having the opportunity to enact these principles in such a dichotomy of treatment settings has been invaluable in my education, in getting to know different facets of my patients, and in understanding the nuances of the human experience.

My colleagues and I entered the realm of outpatient psychiatry during residency at a logistically and dynamically interesting time. At the beginning of our third year in training (July 2022), almost all of the outpatients we were treating were still being seen virtually. For much of the year, they remained that way. However, with the reinstatement of the Ryan Haight Act in May 2023, I began to meet patients in person for the first time—the same patients whom I had known only virtually for the first 10 months of our therapeutic relationship. I observed vast changes in the dynamic of the room; many of these patients opened up more in their first in-person session than they had all year over Zoom.

Once in-person sessions resumed, patients who during virtual visits had assured me for almost a year that their home situation was optimized had a plethora of new things to share about their seemingly straightforward living situations. Relationships that appeared stable had more layers to reveal once the half of the relationship I was treating was now comfortably seated within the walls of my office. Problems that had previously seemed biologically based suddenly had complex sociocultural elements that were divulged for the first time. Some patients felt freer to be unrestricted in their affect, in contrast to the logistical (and metaphorical) buttoned-up virtual environment. Emotions ranged from cathartic (“It’s so great to see you in person!”) to bemused (“You’re taller/shorter, older/younger than I thought!”). The screen was gone, and the tangibility of it all breathed a different air into the room.

Virtual vs in-person: Crabs on a beach

The virtual treatment space could be envisioned as crabs in shells scattered on a beach, in which 2 crabs situated in their own shells, not necessarily adjacent to each other, could communicate. This certainly had benefits, such as the convenience of not having to move to another shell, as well as the brief but telling opportunity to gaze into their home shell environment. However, sometimes there would be disadvantages, such as interference with the connection due to static in the sand; at other times, there was the potential for other crabs to overhear and inadvertently learn of each other’s presence, thus affecting the openness of the communication. In this analogy, perhaps the equivalent of an in-person meeting would be 1 crab meandering over and the 2 crabs cohabiting a conch for the first time—it’s spacious (enough), all-enveloping, and within the harkened privacy of a shared sacred space.

A unique training experience

My co-residents and I are uniquely positioned to observe this novel phenomenon due to the timing of having entered our outpatient psychiatry training during the COVID-19 pandemic. Previous generations of residents—as well as practicing psychiatrists who had initially met their patients in person and were forced to switch to virtual sessions during the pandemic—had certain perspectives and challenges of their own, but they had a known dynamic of in-person interactions at baseline. Accordingly, residents who practiced peak- and mid-pandemic and graduated without being required to treat patients face-to-face (the classes of 2022 and 2023) might have spent entire therapeutic relationships having never met their patients in person. My class (2024) was situated in this time- and situation-bound frame in which we started virtually, and by requirements of the law, later met our patients in person. Being not only an observer but an active participant in a treatment dyad within the context of this phenomenon taught me astutely about transference, countertransference, and the holding environment. Training in psychodynamic psychotherapy has taught me about the act of listening deeply and qualities of therapeutic communication. Having the opportunity to enact these principles in such a dichotomy of treatment settings has been invaluable in my education, in getting to know different facets of my patients, and in understanding the nuances of the human experience.

A new doctor in a COVID mask

As a 2020 graduate, my medical school experience was largely untouched by the coronavirus. However, when I transitioned to residency, the world was 4 months into the COVID-19 pandemic, and I was required to wear an N95 mask. Just as I started calling myself Dr. Petteruti, I stopped seeing my patients’ entire face, and they stopped seeing mine. In this article, I share my reflections on wearing a mask during residency.

Even after 3 years of daily practice, I have found that wearing a mask brings an acute awareness of my face. As a community physician, the spheres of personal and public life intersect as I treat patients. Learning to navigate this is an important and shared experience across many community-based residency programs. However, during the first few years of residency, I have been able to shop at a local grocery store or eat at a nearby restaurant without any concerns of being recognized by a patient. Until recently, my patients had never seen my face. That has now changed.

For a new intern, a mask can be a savior. It can hide most of what is on your face from your patient. It is remarkable how the brain fills in the gaps of the visage and, by extension, aspects of the person. Many times, I was thankful to have my morning yawn or facial expression covered during provoking conversations with patients. Furthermore, masks gave me an opportunity to examine my own reactions, emotions, affect, and countertransference of each interaction on my own time.

The mask mandate also protected some features that illustrated my youth. For the patient, a mask can add a dry, clinical distance to the physician, often emitting a professional interpretation to the encounter. For the physician, the mask serves as a concrete barrier to the otherwise effortless acts of observation. Early in my career, I had to set reminders to have patients who were taking antipsychotic medications remove their masks to assess for tardive dyskinesia. Sometimes this surprised the patient, who was hesitant to expose themselves physically and psychologically. Alternatively, mask wearing has proved to be an additional data point on some patients, such as those with disorganized behavior. If the mask is located on the patient’s head, chin, or eyes, or is otherwise inappropriately placed, this provides the clinician with supplemental information.

After spending most of my third year of residency in an outpatient office diligently learning how to build a sturdy therapeutic patient alliance, the mask mandate was lifted. Patients’ transference began to change right before my newly bared face. People often relate age to wisdom and experience, so my lack of age—and thus, possible perceived lack of knowledge—became glaringly apparent. During our initial encounters without masks, patients I had known for most of the year began discussing their symptoms and treatments with more hesitancy. My established patients suddenly had a noticeable change in the intensity of their eye contact. Some even asked if I had cut my hair or what had changed about my appearance since our previous visit. This change in affect and behavior offers a unique experience for the resident; renovating the patient-doctor relationship based on the physician’s appearance.

As psychiatrists, we would generally assume mask wearing has an undesirable effect on the therapeutic alliance and increases skewed inferences in our evaluations. This held true for my experience in residency. In psychotherapy, we work to help patients remove their own metaphorical “masks” of defense and security in self-exploration. However, as young physicians, rather than creating barriers between us and our patients, the mask mandate seemed to have created a sense of credibility in our practice and trustworthiness in our decisions.

Some questions remain. As clinicians, what are we missing when we can only see our patient’s eyes and forehead? How will the COVID-19 pandemic affect my training and career as a psychiatrist? These may remain unanswered for my generation of trainees for some time, as society will look back and contemplate this period for decades. Though we entered our career in uncertain times, with an increased risk of morbidity and death and high demand for proper personal protective equipment, we were and still are thankful for our masks and for the limited infection exposure afforded by the nature of our specialty.

As a 2020 graduate, my medical school experience was largely untouched by the coronavirus. However, when I transitioned to residency, the world was 4 months into the COVID-19 pandemic, and I was required to wear an N95 mask. Just as I started calling myself Dr. Petteruti, I stopped seeing my patients’ entire face, and they stopped seeing mine. In this article, I share my reflections on wearing a mask during residency.

Even after 3 years of daily practice, I have found that wearing a mask brings an acute awareness of my face. As a community physician, the spheres of personal and public life intersect as I treat patients. Learning to navigate this is an important and shared experience across many community-based residency programs. However, during the first few years of residency, I have been able to shop at a local grocery store or eat at a nearby restaurant without any concerns of being recognized by a patient. Until recently, my patients had never seen my face. That has now changed.

For a new intern, a mask can be a savior. It can hide most of what is on your face from your patient. It is remarkable how the brain fills in the gaps of the visage and, by extension, aspects of the person. Many times, I was thankful to have my morning yawn or facial expression covered during provoking conversations with patients. Furthermore, masks gave me an opportunity to examine my own reactions, emotions, affect, and countertransference of each interaction on my own time.

The mask mandate also protected some features that illustrated my youth. For the patient, a mask can add a dry, clinical distance to the physician, often emitting a professional interpretation to the encounter. For the physician, the mask serves as a concrete barrier to the otherwise effortless acts of observation. Early in my career, I had to set reminders to have patients who were taking antipsychotic medications remove their masks to assess for tardive dyskinesia. Sometimes this surprised the patient, who was hesitant to expose themselves physically and psychologically. Alternatively, mask wearing has proved to be an additional data point on some patients, such as those with disorganized behavior. If the mask is located on the patient’s head, chin, or eyes, or is otherwise inappropriately placed, this provides the clinician with supplemental information.

After spending most of my third year of residency in an outpatient office diligently learning how to build a sturdy therapeutic patient alliance, the mask mandate was lifted. Patients’ transference began to change right before my newly bared face. People often relate age to wisdom and experience, so my lack of age—and thus, possible perceived lack of knowledge—became glaringly apparent. During our initial encounters without masks, patients I had known for most of the year began discussing their symptoms and treatments with more hesitancy. My established patients suddenly had a noticeable change in the intensity of their eye contact. Some even asked if I had cut my hair or what had changed about my appearance since our previous visit. This change in affect and behavior offers a unique experience for the resident; renovating the patient-doctor relationship based on the physician’s appearance.

As psychiatrists, we would generally assume mask wearing has an undesirable effect on the therapeutic alliance and increases skewed inferences in our evaluations. This held true for my experience in residency. In psychotherapy, we work to help patients remove their own metaphorical “masks” of defense and security in self-exploration. However, as young physicians, rather than creating barriers between us and our patients, the mask mandate seemed to have created a sense of credibility in our practice and trustworthiness in our decisions.

Some questions remain. As clinicians, what are we missing when we can only see our patient’s eyes and forehead? How will the COVID-19 pandemic affect my training and career as a psychiatrist? These may remain unanswered for my generation of trainees for some time, as society will look back and contemplate this period for decades. Though we entered our career in uncertain times, with an increased risk of morbidity and death and high demand for proper personal protective equipment, we were and still are thankful for our masks and for the limited infection exposure afforded by the nature of our specialty.

As a 2020 graduate, my medical school experience was largely untouched by the coronavirus. However, when I transitioned to residency, the world was 4 months into the COVID-19 pandemic, and I was required to wear an N95 mask. Just as I started calling myself Dr. Petteruti, I stopped seeing my patients’ entire face, and they stopped seeing mine. In this article, I share my reflections on wearing a mask during residency.

Even after 3 years of daily practice, I have found that wearing a mask brings an acute awareness of my face. As a community physician, the spheres of personal and public life intersect as I treat patients. Learning to navigate this is an important and shared experience across many community-based residency programs. However, during the first few years of residency, I have been able to shop at a local grocery store or eat at a nearby restaurant without any concerns of being recognized by a patient. Until recently, my patients had never seen my face. That has now changed.

For a new intern, a mask can be a savior. It can hide most of what is on your face from your patient. It is remarkable how the brain fills in the gaps of the visage and, by extension, aspects of the person. Many times, I was thankful to have my morning yawn or facial expression covered during provoking conversations with patients. Furthermore, masks gave me an opportunity to examine my own reactions, emotions, affect, and countertransference of each interaction on my own time.

The mask mandate also protected some features that illustrated my youth. For the patient, a mask can add a dry, clinical distance to the physician, often emitting a professional interpretation to the encounter. For the physician, the mask serves as a concrete barrier to the otherwise effortless acts of observation. Early in my career, I had to set reminders to have patients who were taking antipsychotic medications remove their masks to assess for tardive dyskinesia. Sometimes this surprised the patient, who was hesitant to expose themselves physically and psychologically. Alternatively, mask wearing has proved to be an additional data point on some patients, such as those with disorganized behavior. If the mask is located on the patient’s head, chin, or eyes, or is otherwise inappropriately placed, this provides the clinician with supplemental information.

After spending most of my third year of residency in an outpatient office diligently learning how to build a sturdy therapeutic patient alliance, the mask mandate was lifted. Patients’ transference began to change right before my newly bared face. People often relate age to wisdom and experience, so my lack of age—and thus, possible perceived lack of knowledge—became glaringly apparent. During our initial encounters without masks, patients I had known for most of the year began discussing their symptoms and treatments with more hesitancy. My established patients suddenly had a noticeable change in the intensity of their eye contact. Some even asked if I had cut my hair or what had changed about my appearance since our previous visit. This change in affect and behavior offers a unique experience for the resident; renovating the patient-doctor relationship based on the physician’s appearance.

As psychiatrists, we would generally assume mask wearing has an undesirable effect on the therapeutic alliance and increases skewed inferences in our evaluations. This held true for my experience in residency. In psychotherapy, we work to help patients remove their own metaphorical “masks” of defense and security in self-exploration. However, as young physicians, rather than creating barriers between us and our patients, the mask mandate seemed to have created a sense of credibility in our practice and trustworthiness in our decisions.

Some questions remain. As clinicians, what are we missing when we can only see our patient’s eyes and forehead? How will the COVID-19 pandemic affect my training and career as a psychiatrist? These may remain unanswered for my generation of trainees for some time, as society will look back and contemplate this period for decades. Though we entered our career in uncertain times, with an increased risk of morbidity and death and high demand for proper personal protective equipment, we were and still are thankful for our masks and for the limited infection exposure afforded by the nature of our specialty.

Worsening mania while receiving low-dose quetiapine: A case report

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

The second-generation antipsychotic quetiapine is commonly used to treat several psychiatric disorders, including bipolar disorder (BD) and insomnia. In this case report, we discuss a patient with a history of unipolar depression and initial signs of mania who experienced an exacerbation of manic symptoms following administration of low-dose quetiapine. This case underscores the need for careful monitoring of patients receiving quetiapine, especially at lower doses, and the potential limitations of its efficacy in controlling manic symptoms.

Depressed with racing thoughts

Mr. X, age 58, is an Army veteran who lives with his wife of 29 years and works as a contractor. He has a history of depression and a suicide attempt 10 years ago by self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head, which left him with a bullet lodged in his sinus cavity and residual dysarthria after tongue surgery. After the suicide attempt, Mr. X was medically hospitalized, but not psychiatrically hospitalized. Shortly after, he self-discontinued all psychotropic medications and follow-up.

Mr. X has no other medical history and takes no other medications or supplements. His family history includes a mother with schizoaffective disorder, 1 brother with BD, and another brother with developmental delay.

Mr. X remained euthymic until his brother died. Soon after, he began to experience low mood, heightened anxiety, racing thoughts, tearfulness, and mild insomnia. He was prescribed quetiapine 25 mg/d at bedtime and instructed to titrate up to 50 mg/d.

Ten days later, Mr. X was brought to the hospital by his wife, who reported that after starting quetiapine, her husband began to act erratically. He had disorganized and racing thoughts, loose associations, labile affect, hyperactivity/restlessness, and was not sleeping. In the morning before presenting to the hospital, Mr. X had gone to work, laid down on the floor, began mumbling to himself, and would not respond to coworkers. Upon evaluation, Mr. X was noted to have pressured speech, disorganized speech, delusions, anxiety, and hallucinations. A CT scan of his head was normal, and a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, thyroid-stimulating hormone, B12, folate, and hemoglobin A1c were within normal limits. Mr. X’s vitamin D level was low at 22 ng/mL, and a syphilis screen was negative.

Mr. X was admitted to the hospital for his safety. The treatment team discontinued quetiapine and started risperidone 3 mg twice a day for psychotic symptoms and mood stabilization. At the time of discharge 7 days later, Mr. X was no longer experiencing any hallucinations or delusions, his thought process was linear and goal-directed, his mood was stable, and his insomnia had improved. Based on the temporal relationship between the initiation of quetiapine and the onset of Mr. X’s manic symptoms, along with an absence of organic causes, the treatment team suspected Mr. X had experienced a worsening of manic symptoms induced by quetiapine. Before starting quetiapine, he had presented with an initial manic symptom of racing thoughts.

At his next outpatient appointment, Mr. X exhibited significant akathisia. The treatment team initiated propranolol 20 mg twice a day but Mr. X did not experience much improvement. Risperidone was reduced to 1 mg twice a day and Mr. X was started on clonazepam 0.5 mg twice a day. The akathisia resolved. The treatment team decided to discontinue all medications and observe Mr. X for any recurrence of symptoms. One year after his manic episode. Mr. X remained euthymic. He was able to resume full-time work and began psychotherapy to process the grief over the loss of his brother.

Quetiapine’s unique profile

This case sheds light on the potential limitations of quetiapine, especially at lower doses, for managing manic symptoms. Quetiapine exhibits antidepressant effects, even at doses as low as 50 mg/d.1 At higher doses, quetiapine acts as an antagonist at serotonin (5-HT1A and 5-HT2A), dopamine (D1 and D2), histamine H1, and adrenergic receptors.2 At doses <300 mg/d, there is an absence of dopamine receptor blockade and a higher affinity for 5-HT2A receptors, which could explain why higher doses are generally necessary for treating mania and psychotic symptoms.3-5 High 5-HT2A antagonism may disinhibit the dopaminergic system and paradoxically increase dopaminergic activity, which could be the mechanism responsible for lack of control of manic symptoms with low doses of quetiapine.2 Another possible explanation is that the metabolite of quetiapine, N-desalkylquetiapine, acts as a norepinephrine reuptake blocker and partial 5-HT1A antagonist, which acts as an antidepressant, and antidepressants are known to induce mania in vulnerable patients.4

The antimanic property of most antipsychotics (except possibly clozapine) is attributed to their D2 antagonistic potency. Because quetiapine is among the weaker D2 antagonists, its inability to prevent the progression of mania, especially at 50 mg/d, is not unexpected. Mr. X’s subsequent need for a stronger D2 antagonist—risperidone—at a significant dose further supports this observation. A common misconception is that quetiapine’s sedating effects make it effective for treating mania, but that is not the case. Clinicians should be cautious when prescribing quetiapine, especially at lower doses, to patients who exhibit signs of mania. Given the potential risk, clinicians should consider alternative treatments before resorting to low-dose quetiapine for insomnia. Regular monitoring for manic symptoms is crucial for all patients receiving quetiapine. If patients present with signs of mania or hypomania, a therapeutic dose range of 600 to 800 mg/d is recommended.6

- Weisler R, Joyce M, McGill L, et al. Extended release quetiapine fumarate monotherapy for major depressive disorder: results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. CNS Spectr. 2009;14(6):299-313. doi:10.1017/s1092852900020307

- Khalil RB, Baddoura C. Quetiapine induced hypomania: a case report and a review of the literature. Curr Drug Saf. 2012;7(3):250-253. doi:10.2174/157488612803251333

- Benyamina A, Samalin L. Atypical antipsychotic-induced mania/hypomania: a review of recent case reports and clinical studies. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2012;16(1):2-7. doi:10.3109/13651501.2011.605957

- Gnanavel S. Quetiapine-induced manic episode: a paradox for contemplation. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2013201761. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-201761

- Pacchiarotti I, Manfredi G, Kotzalidis GD, et al. Quetiapine-induced mania. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2003;37(5):626.

- Millard HY, Wilson BA, Noordsy DL. Low-dose quetiapine induced or worsened mania in the context of possible undertreatment. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28(1):154-158. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2015.01.140105

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

The second-generation antipsychotic quetiapine is commonly used to treat several psychiatric disorders, including bipolar disorder (BD) and insomnia. In this case report, we discuss a patient with a history of unipolar depression and initial signs of mania who experienced an exacerbation of manic symptoms following administration of low-dose quetiapine. This case underscores the need for careful monitoring of patients receiving quetiapine, especially at lower doses, and the potential limitations of its efficacy in controlling manic symptoms.

Depressed with racing thoughts

Mr. X, age 58, is an Army veteran who lives with his wife of 29 years and works as a contractor. He has a history of depression and a suicide attempt 10 years ago by self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head, which left him with a bullet lodged in his sinus cavity and residual dysarthria after tongue surgery. After the suicide attempt, Mr. X was medically hospitalized, but not psychiatrically hospitalized. Shortly after, he self-discontinued all psychotropic medications and follow-up.

Mr. X has no other medical history and takes no other medications or supplements. His family history includes a mother with schizoaffective disorder, 1 brother with BD, and another brother with developmental delay.

Mr. X remained euthymic until his brother died. Soon after, he began to experience low mood, heightened anxiety, racing thoughts, tearfulness, and mild insomnia. He was prescribed quetiapine 25 mg/d at bedtime and instructed to titrate up to 50 mg/d.

Ten days later, Mr. X was brought to the hospital by his wife, who reported that after starting quetiapine, her husband began to act erratically. He had disorganized and racing thoughts, loose associations, labile affect, hyperactivity/restlessness, and was not sleeping. In the morning before presenting to the hospital, Mr. X had gone to work, laid down on the floor, began mumbling to himself, and would not respond to coworkers. Upon evaluation, Mr. X was noted to have pressured speech, disorganized speech, delusions, anxiety, and hallucinations. A CT scan of his head was normal, and a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, thyroid-stimulating hormone, B12, folate, and hemoglobin A1c were within normal limits. Mr. X’s vitamin D level was low at 22 ng/mL, and a syphilis screen was negative.

Mr. X was admitted to the hospital for his safety. The treatment team discontinued quetiapine and started risperidone 3 mg twice a day for psychotic symptoms and mood stabilization. At the time of discharge 7 days later, Mr. X was no longer experiencing any hallucinations or delusions, his thought process was linear and goal-directed, his mood was stable, and his insomnia had improved. Based on the temporal relationship between the initiation of quetiapine and the onset of Mr. X’s manic symptoms, along with an absence of organic causes, the treatment team suspected Mr. X had experienced a worsening of manic symptoms induced by quetiapine. Before starting quetiapine, he had presented with an initial manic symptom of racing thoughts.

At his next outpatient appointment, Mr. X exhibited significant akathisia. The treatment team initiated propranolol 20 mg twice a day but Mr. X did not experience much improvement. Risperidone was reduced to 1 mg twice a day and Mr. X was started on clonazepam 0.5 mg twice a day. The akathisia resolved. The treatment team decided to discontinue all medications and observe Mr. X for any recurrence of symptoms. One year after his manic episode. Mr. X remained euthymic. He was able to resume full-time work and began psychotherapy to process the grief over the loss of his brother.

Quetiapine’s unique profile

This case sheds light on the potential limitations of quetiapine, especially at lower doses, for managing manic symptoms. Quetiapine exhibits antidepressant effects, even at doses as low as 50 mg/d.1 At higher doses, quetiapine acts as an antagonist at serotonin (5-HT1A and 5-HT2A), dopamine (D1 and D2), histamine H1, and adrenergic receptors.2 At doses <300 mg/d, there is an absence of dopamine receptor blockade and a higher affinity for 5-HT2A receptors, which could explain why higher doses are generally necessary for treating mania and psychotic symptoms.3-5 High 5-HT2A antagonism may disinhibit the dopaminergic system and paradoxically increase dopaminergic activity, which could be the mechanism responsible for lack of control of manic symptoms with low doses of quetiapine.2 Another possible explanation is that the metabolite of quetiapine, N-desalkylquetiapine, acts as a norepinephrine reuptake blocker and partial 5-HT1A antagonist, which acts as an antidepressant, and antidepressants are known to induce mania in vulnerable patients.4

The antimanic property of most antipsychotics (except possibly clozapine) is attributed to their D2 antagonistic potency. Because quetiapine is among the weaker D2 antagonists, its inability to prevent the progression of mania, especially at 50 mg/d, is not unexpected. Mr. X’s subsequent need for a stronger D2 antagonist—risperidone—at a significant dose further supports this observation. A common misconception is that quetiapine’s sedating effects make it effective for treating mania, but that is not the case. Clinicians should be cautious when prescribing quetiapine, especially at lower doses, to patients who exhibit signs of mania. Given the potential risk, clinicians should consider alternative treatments before resorting to low-dose quetiapine for insomnia. Regular monitoring for manic symptoms is crucial for all patients receiving quetiapine. If patients present with signs of mania or hypomania, a therapeutic dose range of 600 to 800 mg/d is recommended.6

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

The second-generation antipsychotic quetiapine is commonly used to treat several psychiatric disorders, including bipolar disorder (BD) and insomnia. In this case report, we discuss a patient with a history of unipolar depression and initial signs of mania who experienced an exacerbation of manic symptoms following administration of low-dose quetiapine. This case underscores the need for careful monitoring of patients receiving quetiapine, especially at lower doses, and the potential limitations of its efficacy in controlling manic symptoms.

Depressed with racing thoughts

Mr. X, age 58, is an Army veteran who lives with his wife of 29 years and works as a contractor. He has a history of depression and a suicide attempt 10 years ago by self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head, which left him with a bullet lodged in his sinus cavity and residual dysarthria after tongue surgery. After the suicide attempt, Mr. X was medically hospitalized, but not psychiatrically hospitalized. Shortly after, he self-discontinued all psychotropic medications and follow-up.

Mr. X has no other medical history and takes no other medications or supplements. His family history includes a mother with schizoaffective disorder, 1 brother with BD, and another brother with developmental delay.

Mr. X remained euthymic until his brother died. Soon after, he began to experience low mood, heightened anxiety, racing thoughts, tearfulness, and mild insomnia. He was prescribed quetiapine 25 mg/d at bedtime and instructed to titrate up to 50 mg/d.