User login

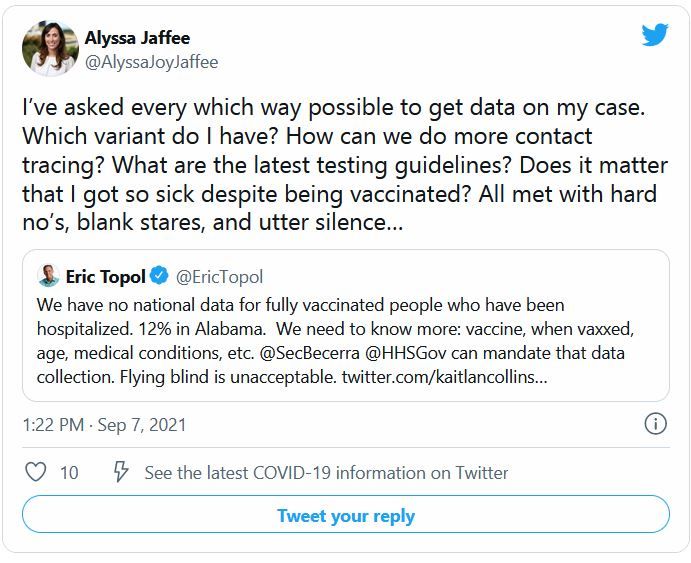

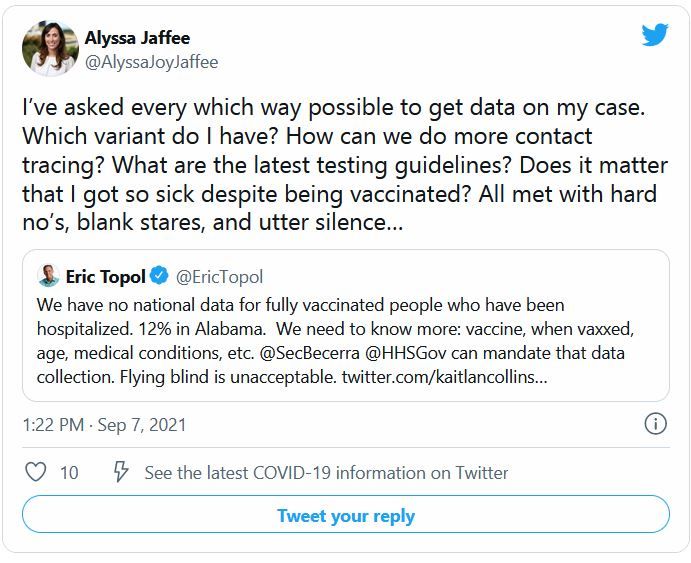

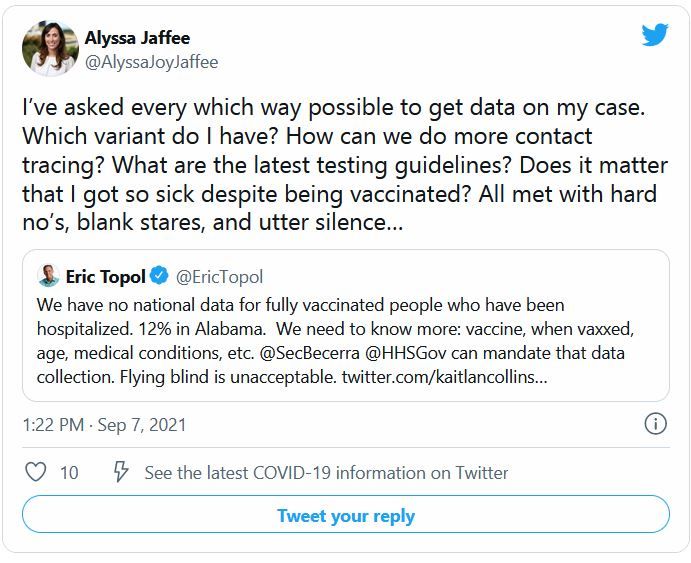

Every day, more than 140,000 people in the United States are diagnosed with COVID-19. But no matter how curious they are about which variant they are fighting, none of them will find out.

The country is dotted with labs that sequence the genomes of COVID-19 cases, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tracks those results. But federal rules say those results are not allowed to make their way back to patients or doctors.

According to public health and infectious disease experts, this is unlikely to change any time soon.

“I know people want to know – I’ve had a lot of friends or family who’ve asked me how they can find out,” says Aubree Gordon, PhD, an epidemiology specialist at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. “I think it’s an interesting thing to find out, for sure. And it would certainly be nice to know. But because it probably isn’t necessary, there is little motivation to change the rules.”

Because the tests that are used have not been approved as diagnostic tools under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments program, which is overseen by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, they can only be used for research purposes.

In fact, the scientists doing the sequencing rarely have any patient information, Dr. Gordon says. For example, the Lauring Lab at University of Michigan – run by Adam Lauring, MD – focuses on viral evolution and currently tests for variants. But this is not done for the sake of the patient or the doctors treating the patient.

“The samples come in ... and they’ve been de-identified,”Dr. Gordon says. “This is just for research purposes. Not much patient information is shared with the researchers.”

But as of now, aside from sheer curiosity, there is not a reason to change this, says Timothy Brewer, MD, a professor of medicine and epidemiology at University of California, Los Angeles.

Although there are emerging variants – including the new Mu variant, also known as B.1.621 and recently classified as a “variant of interest” – the Delta variant accounts for about 99% of U.S. cases.

In addition, Dr. Brewer says, treatments are the same for all COVID-19 patients, regardless of the variant.

“There would have to be some clinical significance for there to be a good reason to give this information,” he says. “That would mean we would be doing something different treatment-wise depending on the variant. As of now, that is not the case.”

There is a loophole that allows labs to release variant information: They can develop their own tests. But they then must go through a lengthy validation process that proves their tests are as effective as the gold standard, says Mark Pandori, PhD, director of the Nevada State Public Health Laboratory.

But even with validation, it is too time-consuming and costly to sequence large numbers of cases, he says.

“The reason we’re not doing it routinely is there’s no way to do the genomic analysis on all the positives,” Dr. Pandori says. “It is about $110 dollars to do a sequence. It’s not like a standard PCR test.”

There is a hypothetical situation that may warrant the release of these results, Dr. Brewer says: If a variant emerges that evades vaccines.

“That would be a real public health issue,” he says. “You want to make sure there aren’t variants emerging somewhere that are escaping immunity.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Every day, more than 140,000 people in the United States are diagnosed with COVID-19. But no matter how curious they are about which variant they are fighting, none of them will find out.

The country is dotted with labs that sequence the genomes of COVID-19 cases, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tracks those results. But federal rules say those results are not allowed to make their way back to patients or doctors.

According to public health and infectious disease experts, this is unlikely to change any time soon.

“I know people want to know – I’ve had a lot of friends or family who’ve asked me how they can find out,” says Aubree Gordon, PhD, an epidemiology specialist at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. “I think it’s an interesting thing to find out, for sure. And it would certainly be nice to know. But because it probably isn’t necessary, there is little motivation to change the rules.”

Because the tests that are used have not been approved as diagnostic tools under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments program, which is overseen by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, they can only be used for research purposes.

In fact, the scientists doing the sequencing rarely have any patient information, Dr. Gordon says. For example, the Lauring Lab at University of Michigan – run by Adam Lauring, MD – focuses on viral evolution and currently tests for variants. But this is not done for the sake of the patient or the doctors treating the patient.

“The samples come in ... and they’ve been de-identified,”Dr. Gordon says. “This is just for research purposes. Not much patient information is shared with the researchers.”

But as of now, aside from sheer curiosity, there is not a reason to change this, says Timothy Brewer, MD, a professor of medicine and epidemiology at University of California, Los Angeles.

Although there are emerging variants – including the new Mu variant, also known as B.1.621 and recently classified as a “variant of interest” – the Delta variant accounts for about 99% of U.S. cases.

In addition, Dr. Brewer says, treatments are the same for all COVID-19 patients, regardless of the variant.

“There would have to be some clinical significance for there to be a good reason to give this information,” he says. “That would mean we would be doing something different treatment-wise depending on the variant. As of now, that is not the case.”

There is a loophole that allows labs to release variant information: They can develop their own tests. But they then must go through a lengthy validation process that proves their tests are as effective as the gold standard, says Mark Pandori, PhD, director of the Nevada State Public Health Laboratory.

But even with validation, it is too time-consuming and costly to sequence large numbers of cases, he says.

“The reason we’re not doing it routinely is there’s no way to do the genomic analysis on all the positives,” Dr. Pandori says. “It is about $110 dollars to do a sequence. It’s not like a standard PCR test.”

There is a hypothetical situation that may warrant the release of these results, Dr. Brewer says: If a variant emerges that evades vaccines.

“That would be a real public health issue,” he says. “You want to make sure there aren’t variants emerging somewhere that are escaping immunity.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Every day, more than 140,000 people in the United States are diagnosed with COVID-19. But no matter how curious they are about which variant they are fighting, none of them will find out.

The country is dotted with labs that sequence the genomes of COVID-19 cases, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tracks those results. But federal rules say those results are not allowed to make their way back to patients or doctors.

According to public health and infectious disease experts, this is unlikely to change any time soon.

“I know people want to know – I’ve had a lot of friends or family who’ve asked me how they can find out,” says Aubree Gordon, PhD, an epidemiology specialist at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. “I think it’s an interesting thing to find out, for sure. And it would certainly be nice to know. But because it probably isn’t necessary, there is little motivation to change the rules.”

Because the tests that are used have not been approved as diagnostic tools under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments program, which is overseen by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, they can only be used for research purposes.

In fact, the scientists doing the sequencing rarely have any patient information, Dr. Gordon says. For example, the Lauring Lab at University of Michigan – run by Adam Lauring, MD – focuses on viral evolution and currently tests for variants. But this is not done for the sake of the patient or the doctors treating the patient.

“The samples come in ... and they’ve been de-identified,”Dr. Gordon says. “This is just for research purposes. Not much patient information is shared with the researchers.”

But as of now, aside from sheer curiosity, there is not a reason to change this, says Timothy Brewer, MD, a professor of medicine and epidemiology at University of California, Los Angeles.

Although there are emerging variants – including the new Mu variant, also known as B.1.621 and recently classified as a “variant of interest” – the Delta variant accounts for about 99% of U.S. cases.

In addition, Dr. Brewer says, treatments are the same for all COVID-19 patients, regardless of the variant.

“There would have to be some clinical significance for there to be a good reason to give this information,” he says. “That would mean we would be doing something different treatment-wise depending on the variant. As of now, that is not the case.”

There is a loophole that allows labs to release variant information: They can develop their own tests. But they then must go through a lengthy validation process that proves their tests are as effective as the gold standard, says Mark Pandori, PhD, director of the Nevada State Public Health Laboratory.

But even with validation, it is too time-consuming and costly to sequence large numbers of cases, he says.

“The reason we’re not doing it routinely is there’s no way to do the genomic analysis on all the positives,” Dr. Pandori says. “It is about $110 dollars to do a sequence. It’s not like a standard PCR test.”

There is a hypothetical situation that may warrant the release of these results, Dr. Brewer says: If a variant emerges that evades vaccines.

“That would be a real public health issue,” he says. “You want to make sure there aren’t variants emerging somewhere that are escaping immunity.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.