User login

Guess what? Physician-driven accountable care organizations with a strong primary care core are working – and, in a historic change, primary care physicians are the most highly compensated group.

The even better news? This trend is predictable and inevitable.

ACOs are working

As earlier posts to this column show, there are eight fairly straightforward elements required to create a successful and sustainable ACO:

• A change in financial incentives from those that reward volume, such as fee-for-service, to those that reward value, such as shared savings, if quality benchmarks are met.

• A primary care core.

• Physician cultural change.

• Patient engagement.

• Robust data collection.

• Clinical best practices.

• Administrative infrastructure.

• Enough scale.

A number of ACOs that do not have these elements will fail; but fortunately, more and more are being set up properly.

Recently, the Boston Consulting Group reported that ACO-like Medicare Advantage plans are reporting positive results. They are all distinguished by having "a selective network of providers, financial incentives that are aligned with clinical best practices, and active care management that emphasizes prevention in an effort to minimize expensive acute care."

Not only are emergency department and ambulatory surgery procedures down 20%-30% at these plans, but analysis of their data on 3 million Medicare patients showed that quality went up. These patients had lower single-year mortality rates, shorter average hospital stays, fewer readmissions, and better sustainability of health over time.1

Physician-led ACOs are better

If ACOs are good, physician-sponsored ones are better.

At a recent national meeting of health insurance companies, Paul Ginsburg, Ph.D., president of the Center for Studying Health System Change, told the insurers, "I think physician-led ACOs inherently make markets more competitive, because they have an opportunity to shift patients toward high-value hospitals."

Similarly, Charlie Baker, former secretary of health and human services for Massachusetts, told the group that nearly all of the Medicare Advantage risk contracts are with physician groups and not hospitals. Medicare Advantage participants are chosen by insurers, and he indicated that they know that contracting with physician ACOs is the best way to save money.2

As reported in an earlier column, this truth is becoming more evident, and there are now more physician-led ACOs than any other.

Primary care reaping rewards

Primary care is the only discipline mandated to be in ACOs participating in the Medicare Shared Savings Program. This is because ACO success stems from keeping people out of the hospital, avoiding expensive procedures, and reducing unnecessary tests and imaging. The "target-rich fields" for ACOs to accomplish this are primarily prevention and wellness, coordination of high-cost complex patients, reduced hospitalizations, and transition management across our fragmented system. These are all in primary care’s wheelhouse. It is no wonder that you are the darlings of the accountable care movement.

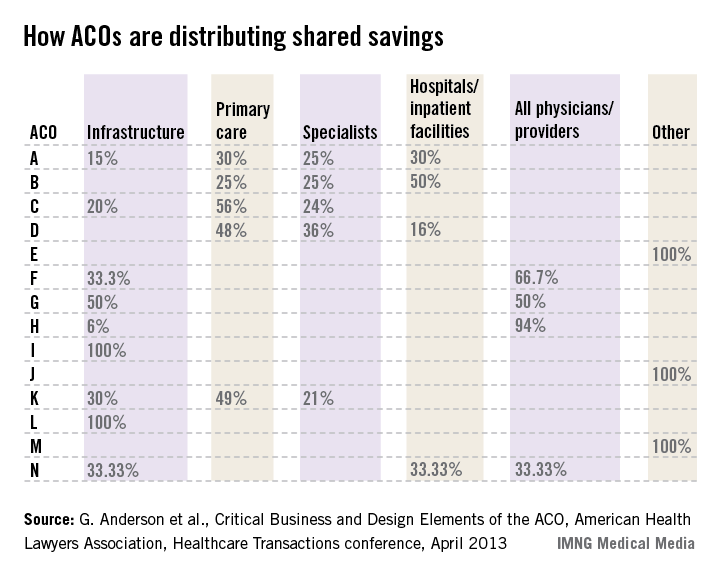

Successful and sustainable ACOs will tie shared savings distributions to relative contribution. A merit system thus likely will be primary care weighted.

For example, one ACO posted this planned distribution of shared savings: 12% to infrastructure; of the remainder, 60% to primary care, 40% to specialists, and 0% to hospitals.

The following small sample survey shows widely varying models; but in all cases where distribution is broken out, primary care receives as much or more than specialists and, with one exception, hospitals.

There are some primary-care-only ACOs that are distributing 100% of savings to their primary care physicians under Medicare Advantage risk or Medicare Shared Savings Program contracts. One interviewed primary care physician ACO member stated that for his full-risk Medicare Advantage patient population, he was seeing half as many patients and making three times the income.

While income recognition for what you do is way overdue, keeping all the savings might be going too far. A fully evolved ACO should incentivize all providers and facilities along the entire continuum of care, but always in proportion to their value-adding contribution.

Primary care physicians tell me that while this economic reward is gratifying and validating, their surprise biggest reward has been empowerment to do health care right and regain control of the physician/patient relationship. They say that seeing happier, healthier patients, and being able to spend more time with them, has returned the fun to the practice of medicine.

References

1. Kaplan, J., et al., Alternative Payer Models Show Improved Health-Care Value, BCG Perspective, May 14, 2013.

2. Pittman, D., Doc-Led ACOs Better Model for Saving $$$, MedPage Today, May 15, 2013.

3. Anderson, G., et al., Critical Business and Design Elements of the ACO, American Health Lawyers Association, Healthcare Transactions conference (April 2013).

Mr. Bobbitt is a senior partner and head of the Health Law Group at the Smith Anderson law firm in Raleigh, North Carolina. He has many years’ experience assisting physicians form integrated delivery systems. He has spoken and written nationally to primary care physicians on the strategies and practicalities of forming or joining ACOs. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at bbobbitt@smithlaw.com or 919-821-6612.

Guess what? Physician-driven accountable care organizations with a strong primary care core are working – and, in a historic change, primary care physicians are the most highly compensated group.

The even better news? This trend is predictable and inevitable.

ACOs are working

As earlier posts to this column show, there are eight fairly straightforward elements required to create a successful and sustainable ACO:

• A change in financial incentives from those that reward volume, such as fee-for-service, to those that reward value, such as shared savings, if quality benchmarks are met.

• A primary care core.

• Physician cultural change.

• Patient engagement.

• Robust data collection.

• Clinical best practices.

• Administrative infrastructure.

• Enough scale.

A number of ACOs that do not have these elements will fail; but fortunately, more and more are being set up properly.

Recently, the Boston Consulting Group reported that ACO-like Medicare Advantage plans are reporting positive results. They are all distinguished by having "a selective network of providers, financial incentives that are aligned with clinical best practices, and active care management that emphasizes prevention in an effort to minimize expensive acute care."

Not only are emergency department and ambulatory surgery procedures down 20%-30% at these plans, but analysis of their data on 3 million Medicare patients showed that quality went up. These patients had lower single-year mortality rates, shorter average hospital stays, fewer readmissions, and better sustainability of health over time.1

Physician-led ACOs are better

If ACOs are good, physician-sponsored ones are better.

At a recent national meeting of health insurance companies, Paul Ginsburg, Ph.D., president of the Center for Studying Health System Change, told the insurers, "I think physician-led ACOs inherently make markets more competitive, because they have an opportunity to shift patients toward high-value hospitals."

Similarly, Charlie Baker, former secretary of health and human services for Massachusetts, told the group that nearly all of the Medicare Advantage risk contracts are with physician groups and not hospitals. Medicare Advantage participants are chosen by insurers, and he indicated that they know that contracting with physician ACOs is the best way to save money.2

As reported in an earlier column, this truth is becoming more evident, and there are now more physician-led ACOs than any other.

Primary care reaping rewards

Primary care is the only discipline mandated to be in ACOs participating in the Medicare Shared Savings Program. This is because ACO success stems from keeping people out of the hospital, avoiding expensive procedures, and reducing unnecessary tests and imaging. The "target-rich fields" for ACOs to accomplish this are primarily prevention and wellness, coordination of high-cost complex patients, reduced hospitalizations, and transition management across our fragmented system. These are all in primary care’s wheelhouse. It is no wonder that you are the darlings of the accountable care movement.

Successful and sustainable ACOs will tie shared savings distributions to relative contribution. A merit system thus likely will be primary care weighted.

For example, one ACO posted this planned distribution of shared savings: 12% to infrastructure; of the remainder, 60% to primary care, 40% to specialists, and 0% to hospitals.

The following small sample survey shows widely varying models; but in all cases where distribution is broken out, primary care receives as much or more than specialists and, with one exception, hospitals.

There are some primary-care-only ACOs that are distributing 100% of savings to their primary care physicians under Medicare Advantage risk or Medicare Shared Savings Program contracts. One interviewed primary care physician ACO member stated that for his full-risk Medicare Advantage patient population, he was seeing half as many patients and making three times the income.

While income recognition for what you do is way overdue, keeping all the savings might be going too far. A fully evolved ACO should incentivize all providers and facilities along the entire continuum of care, but always in proportion to their value-adding contribution.

Primary care physicians tell me that while this economic reward is gratifying and validating, their surprise biggest reward has been empowerment to do health care right and regain control of the physician/patient relationship. They say that seeing happier, healthier patients, and being able to spend more time with them, has returned the fun to the practice of medicine.

References

1. Kaplan, J., et al., Alternative Payer Models Show Improved Health-Care Value, BCG Perspective, May 14, 2013.

2. Pittman, D., Doc-Led ACOs Better Model for Saving $$$, MedPage Today, May 15, 2013.

3. Anderson, G., et al., Critical Business and Design Elements of the ACO, American Health Lawyers Association, Healthcare Transactions conference (April 2013).

Mr. Bobbitt is a senior partner and head of the Health Law Group at the Smith Anderson law firm in Raleigh, North Carolina. He has many years’ experience assisting physicians form integrated delivery systems. He has spoken and written nationally to primary care physicians on the strategies and practicalities of forming or joining ACOs. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at bbobbitt@smithlaw.com or 919-821-6612.

Guess what? Physician-driven accountable care organizations with a strong primary care core are working – and, in a historic change, primary care physicians are the most highly compensated group.

The even better news? This trend is predictable and inevitable.

ACOs are working

As earlier posts to this column show, there are eight fairly straightforward elements required to create a successful and sustainable ACO:

• A change in financial incentives from those that reward volume, such as fee-for-service, to those that reward value, such as shared savings, if quality benchmarks are met.

• A primary care core.

• Physician cultural change.

• Patient engagement.

• Robust data collection.

• Clinical best practices.

• Administrative infrastructure.

• Enough scale.

A number of ACOs that do not have these elements will fail; but fortunately, more and more are being set up properly.

Recently, the Boston Consulting Group reported that ACO-like Medicare Advantage plans are reporting positive results. They are all distinguished by having "a selective network of providers, financial incentives that are aligned with clinical best practices, and active care management that emphasizes prevention in an effort to minimize expensive acute care."

Not only are emergency department and ambulatory surgery procedures down 20%-30% at these plans, but analysis of their data on 3 million Medicare patients showed that quality went up. These patients had lower single-year mortality rates, shorter average hospital stays, fewer readmissions, and better sustainability of health over time.1

Physician-led ACOs are better

If ACOs are good, physician-sponsored ones are better.

At a recent national meeting of health insurance companies, Paul Ginsburg, Ph.D., president of the Center for Studying Health System Change, told the insurers, "I think physician-led ACOs inherently make markets more competitive, because they have an opportunity to shift patients toward high-value hospitals."

Similarly, Charlie Baker, former secretary of health and human services for Massachusetts, told the group that nearly all of the Medicare Advantage risk contracts are with physician groups and not hospitals. Medicare Advantage participants are chosen by insurers, and he indicated that they know that contracting with physician ACOs is the best way to save money.2

As reported in an earlier column, this truth is becoming more evident, and there are now more physician-led ACOs than any other.

Primary care reaping rewards

Primary care is the only discipline mandated to be in ACOs participating in the Medicare Shared Savings Program. This is because ACO success stems from keeping people out of the hospital, avoiding expensive procedures, and reducing unnecessary tests and imaging. The "target-rich fields" for ACOs to accomplish this are primarily prevention and wellness, coordination of high-cost complex patients, reduced hospitalizations, and transition management across our fragmented system. These are all in primary care’s wheelhouse. It is no wonder that you are the darlings of the accountable care movement.

Successful and sustainable ACOs will tie shared savings distributions to relative contribution. A merit system thus likely will be primary care weighted.

For example, one ACO posted this planned distribution of shared savings: 12% to infrastructure; of the remainder, 60% to primary care, 40% to specialists, and 0% to hospitals.

The following small sample survey shows widely varying models; but in all cases where distribution is broken out, primary care receives as much or more than specialists and, with one exception, hospitals.

There are some primary-care-only ACOs that are distributing 100% of savings to their primary care physicians under Medicare Advantage risk or Medicare Shared Savings Program contracts. One interviewed primary care physician ACO member stated that for his full-risk Medicare Advantage patient population, he was seeing half as many patients and making three times the income.

While income recognition for what you do is way overdue, keeping all the savings might be going too far. A fully evolved ACO should incentivize all providers and facilities along the entire continuum of care, but always in proportion to their value-adding contribution.

Primary care physicians tell me that while this economic reward is gratifying and validating, their surprise biggest reward has been empowerment to do health care right and regain control of the physician/patient relationship. They say that seeing happier, healthier patients, and being able to spend more time with them, has returned the fun to the practice of medicine.

References

1. Kaplan, J., et al., Alternative Payer Models Show Improved Health-Care Value, BCG Perspective, May 14, 2013.

2. Pittman, D., Doc-Led ACOs Better Model for Saving $$$, MedPage Today, May 15, 2013.

3. Anderson, G., et al., Critical Business and Design Elements of the ACO, American Health Lawyers Association, Healthcare Transactions conference (April 2013).

Mr. Bobbitt is a senior partner and head of the Health Law Group at the Smith Anderson law firm in Raleigh, North Carolina. He has many years’ experience assisting physicians form integrated delivery systems. He has spoken and written nationally to primary care physicians on the strategies and practicalities of forming or joining ACOs. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at bbobbitt@smithlaw.com or 919-821-6612.