User login

CLINICAL SCENARIO

A 59-year-old man is observed in the hospital for substernal chest pain initially concerning for angina. Serial troponin testing is negative, and based on additional history of intermittent dysphagia, an elective upper endoscopy is recommended after discharge. The patient does not have health insurance and expresses anxiety about the cost of endoscopy. He asks how he could compare the costs at different hospitals. How do federal price transparency rules assist the hospitalist in addressing this patient’s question?

BACKGROUND AND HISTORY

Healthcare costs continue to rise in the United States despite mounting concerns about wasteful spending and unaffordability.1 One contributor is a lack of price transparency.2 In theory, price transparency allows individuals to shop for services, spurring competition and lower prices. However, healthcare prices have historically been opaque to both physicians and patients; unlike other licensed professionals who provide clients estimates for their work (eg, lawyers, electricians), physicians are rarely able to offer patients real-time insight or guidance about costs, which most patients discover only when the bill arrives. The situation is particularly problematic for patients who bear higher out-of-pocket costs, such as the uninsured or those with high-deductible health plans.3

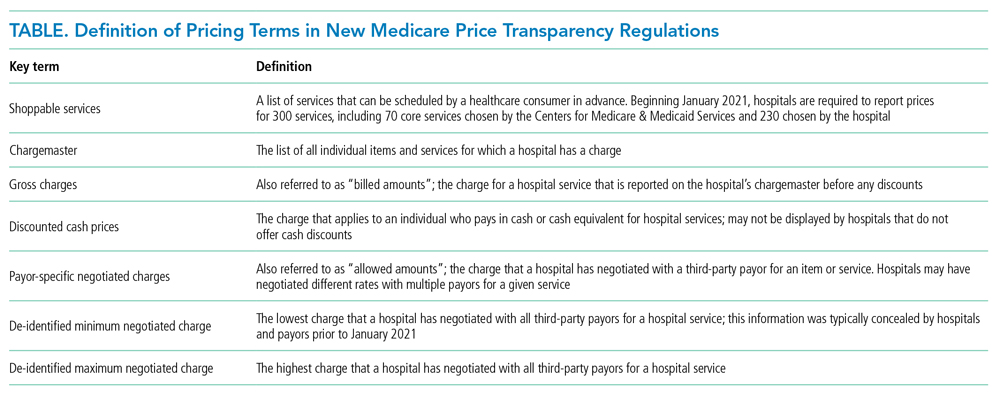

Decades of work to improve healthcare price transparency have unfortunately borne little fruit. Multiple states and organizations have attempted to disseminate price information on comparison websites.4 These efforts only modestly reduced some prices, with benefits confined to elective, single-episode, commodifiable services such as magnetic resonance imaging scans.5 The Affordable Care Act required hospitals to publish standard charges, also called a chargemaster (Table).6 However, chargemaster fees are notoriously inflated and inaccessible at the point of service, undercutting transparency.

POLICY IN CLINICAL PRACTICE

Beginning January 2021, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) required all hospitals to publish negotiated prices—including payor-specific negotiated charges—for 300 “shoppable services” (Table).6 The list must include 70 common CMS-specified services, such as a basic metabolic panel, upper endoscopy, and prostate biopsy, as well as another 230 services that each hospital determines relevant to its patient population.

In circumstances where hospitals have negotiated different prices for a service, they must list each third-party payor and their payor-specific charge. The information must be prominently displayed, accessible without requiring the patient to enter personal information, and provided in a machine-readable file. CMS may impose a $300 daily penalty on hospitals failing to comply with the policy. Of note, the policy does not apply to clinics or ambulatory surgery centers.

As more hospitals share data, this policy will directly benefit both patients and physicians. It can benefit patients with the time, foresight, and ability to search for the lowest price for shoppable services. Other patients may also benefit indirectly, to the extent that insurers and other purchasers apply this information to negotiate lower and more uniform prices. Decreased price variation may also encourage hospitals to compete on quality to distinguish the value of their services. Hospitalists could benefit through the ability to directly help patients locate price information.

Despite these potential benefits, the policy has limitations. Price information about shoppable services is most useful for discharge planning, and other solutions are needed to address transparency before and during unplanned admissions. Patients who prioritize continuity with a hospital or physician may be less price sensitive, particularly for more complex services. Patients with commercial insurance may be shielded from cost considerations and personal incentives to comparison shop. Interpreting hospitals’ estimates remains difficult, as it can be unclear if professional fees are included or if certain prices are offered to outpatients.7 Price information is not accompanied by corresponding quality data. Additionally, price transparency may also fail to lower prices in heavily concentrated payor or provider markets, and it remains unknown whether some providers may actually raise prices after learning about higher rates negotiated by competitors.8,9

Another issue is hospital participation. Early evidence suggests that most hospitals have not complied with the letter or spirit of the regulation.

Despite its limitations, this policy represents a meaningful advance for healthcare competition and patient empowerment. Additionally, it signals federal willingness to address the lack of price transparency as a source of widespread patient and clinician frustration—a commitment that will be needed to sustain this policy and implement additional measures in the future.

COMMENTARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

CMS could consider five steps to augment the policy and maximize transparency and value for patients.

First, CMS could consider increasing daily nonparticipation penalties. Hospitals, particularly those in areas with less competition, have less incentive to participate given meager current penalties. Because the magnitude needed to compel action remains unknown, CMS could gradually escalate penalties over time until there is broader participation across hospitals.

Second, policymakers could aggregate price information centrally, organize the data around patients’ clinical scenarios, and advertise its availability. Currently, this information is scattered and time-consuming for hospitalists and patients to gather for decision-making. Additionally, CMS could encourage the development of third-party tools that aggregate and analyze machine-readable price data or require that prices be posted at the point of service.

Third, CMS could revise the policy to include quality as well as price information. Price alone does not offer a full enough picture of what consumers can expect from hospitals for shoppable services. Pairing price and quality information is better aligned to addressing costs in the context of value, rather than cost-cutting for its own purposes.

Fourth, over time, CMS could expand the list of services and sites required to report (eg, clinics and ambulatory surgical centers as well as hospitals).

Fifth, CMS rule-makers could set reporting standards and contextualize price information in common clinical scenarios. Patients may have difficulty shopping for complex healthcare services without understanding how they apply in different clinical situations. Decision-making would also be aided by reporting standards—for instance, for how prices are displayed and whether they include certain fees (eg, professional fees, pathology studies).

WHAT SHOULD I TELL MY PATIENT?

Hospitalists planning follow-up care should inform patients that price information is increasingly available and encourage them to search on the internet or contact hospital billing offices to request information (eg, discounted cash prices and minimum negotiated charges) before obtaining elective services after discharge. Hospitalists can also encourage patients to discuss shoppable services with their primary care physicians to understand the clinical context and make high-value decisions. Hospitalists who wish to build communication skills discussing costs with patients can increasingly find resources for these conversations and request that prices be displayed in the electronic health record for this purpose.13,14 As conversations occur, hospitalists should seek to understand other factors, such as convenience and continuity relationships, that might influence choices.

CONCLUSIONS

Starting in 2021, CMS policy requires that hospitals report prices for services such as the endoscopy recommended for the patient in the scenario. Though the policy gives patients new hope for greater transparency and better prices, additional steps are needed to help patients and hospitalists achieve these benefits.

1. Shrank WH, Rogstad TL, Parekh N. Waste in the US health care system: estimated costs and potential for savings. JAMA. 2019;322(15):1501-1509. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.13978

2. Wetzell S. Transparency: a needed step towards health care affordability. American Health Policy Institute. March 2014. Accessed August 26, 2021. https://www.americanhealthpolicy.org/Content/documents/resources/Transparency%20Study%201%20-%20The%20Need%20for%20Health%20Care%20Transparency.pdf

3. Mehrotra A, Dean KM, Sinaiko AD, Sood N. Americans support price shopping for health care, but few actually seek out price information. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(8):1392-1400. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1471

4. Kullgren JT, Duey KA, Werner RM. A census of state health care price transparency websites. JAMA. 2013;309(23):2437-2438. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.6557

5. Brown ZY. Equilibrium effects of health care price information. Rev Econ Stat. 2019;101(4):699-712. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_00765

6. Medicare and Medicaid Programs: CY 2020 hospital outpatient PPS policy changes and payment rates and ambulatory surgical center payment system policy changes and payment rates. Price transparency requirements for hospitals to make standard charges public. 45 CFR §180.20 (2019).

7. Kurani N, Ramirez G, Hudman J, Cox C, Kamal R. Early results from federal price transparency rule show difficulty in estimating the cost of care. Peterson-Kaiser Family Foundation. April 9, 2021. Accessed August 26, 2021. https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/brief/early-results-from-federal-price-transparency-rule-show-difficultly-in-estimating-the-cost-of-care/

8. Miller BJ, Mandelberg MC, Griffith NC, Ehrenfeld JM. Price transparency: empowering patient choice and promoting provider competition. J Med Syst. 2020;44(4):80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-020-01553-2

9. Glied S. Price transparency–promise and peril. JAMA. 2021;325(15):1496-1497. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.4640

10. Haque W, Ahmadzada M, Allahrakha H, Haque E, Hsiehchen D. Transparency, accessibility, and variability of US hospital price data. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(5):e2110109. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.10109

11. Henderson M, Mouslim MC. Low compliance from big hospitals on CMS’s hospital price transparency rule. Health Affairs Blog. March 16, 2021. Accessed August 26, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1377/hblog20210311.899634

12. McGinty T, Wilde Mathews A, Evans M. Hospitals hide pricing data from search results. The Wall Street Journal. March 22, 2021. Accessed August 26, 2021. https://www.wsj.com/articles/hospitals-hide-pricing-data-from-search-results-11616405402

13. Dine CJ, Masi D, Smith CD. Tools to help overcome barriers to cost-of-care conversations. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(9 suppl):S36-S38. https://doi.org/10.7326/M19-0778

14. Miller BJ, Slota JM, Ehrenfeld JM. Redefining the physician’s role in cost-conscious care: the potential role of the electronic health record. JAMA. 2019;322(8):721-722. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.9114

CLINICAL SCENARIO

A 59-year-old man is observed in the hospital for substernal chest pain initially concerning for angina. Serial troponin testing is negative, and based on additional history of intermittent dysphagia, an elective upper endoscopy is recommended after discharge. The patient does not have health insurance and expresses anxiety about the cost of endoscopy. He asks how he could compare the costs at different hospitals. How do federal price transparency rules assist the hospitalist in addressing this patient’s question?

BACKGROUND AND HISTORY

Healthcare costs continue to rise in the United States despite mounting concerns about wasteful spending and unaffordability.1 One contributor is a lack of price transparency.2 In theory, price transparency allows individuals to shop for services, spurring competition and lower prices. However, healthcare prices have historically been opaque to both physicians and patients; unlike other licensed professionals who provide clients estimates for their work (eg, lawyers, electricians), physicians are rarely able to offer patients real-time insight or guidance about costs, which most patients discover only when the bill arrives. The situation is particularly problematic for patients who bear higher out-of-pocket costs, such as the uninsured or those with high-deductible health plans.3

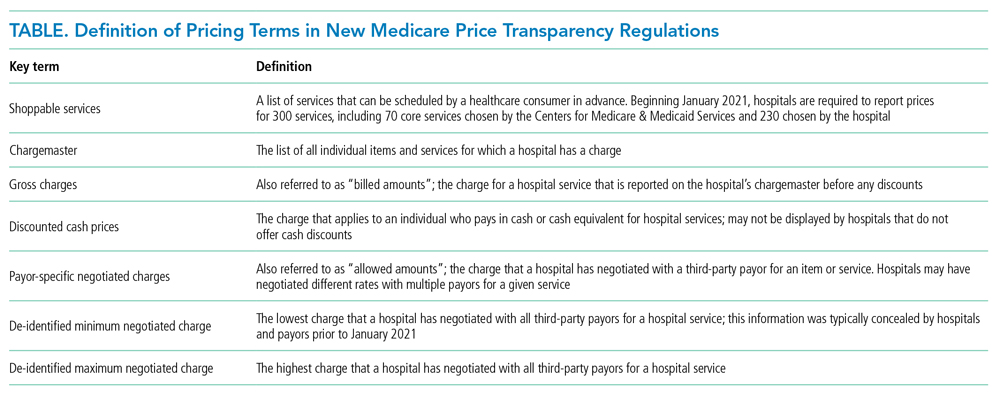

Decades of work to improve healthcare price transparency have unfortunately borne little fruit. Multiple states and organizations have attempted to disseminate price information on comparison websites.4 These efforts only modestly reduced some prices, with benefits confined to elective, single-episode, commodifiable services such as magnetic resonance imaging scans.5 The Affordable Care Act required hospitals to publish standard charges, also called a chargemaster (Table).6 However, chargemaster fees are notoriously inflated and inaccessible at the point of service, undercutting transparency.

POLICY IN CLINICAL PRACTICE

Beginning January 2021, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) required all hospitals to publish negotiated prices—including payor-specific negotiated charges—for 300 “shoppable services” (Table).6 The list must include 70 common CMS-specified services, such as a basic metabolic panel, upper endoscopy, and prostate biopsy, as well as another 230 services that each hospital determines relevant to its patient population.

In circumstances where hospitals have negotiated different prices for a service, they must list each third-party payor and their payor-specific charge. The information must be prominently displayed, accessible without requiring the patient to enter personal information, and provided in a machine-readable file. CMS may impose a $300 daily penalty on hospitals failing to comply with the policy. Of note, the policy does not apply to clinics or ambulatory surgery centers.

As more hospitals share data, this policy will directly benefit both patients and physicians. It can benefit patients with the time, foresight, and ability to search for the lowest price for shoppable services. Other patients may also benefit indirectly, to the extent that insurers and other purchasers apply this information to negotiate lower and more uniform prices. Decreased price variation may also encourage hospitals to compete on quality to distinguish the value of their services. Hospitalists could benefit through the ability to directly help patients locate price information.

Despite these potential benefits, the policy has limitations. Price information about shoppable services is most useful for discharge planning, and other solutions are needed to address transparency before and during unplanned admissions. Patients who prioritize continuity with a hospital or physician may be less price sensitive, particularly for more complex services. Patients with commercial insurance may be shielded from cost considerations and personal incentives to comparison shop. Interpreting hospitals’ estimates remains difficult, as it can be unclear if professional fees are included or if certain prices are offered to outpatients.7 Price information is not accompanied by corresponding quality data. Additionally, price transparency may also fail to lower prices in heavily concentrated payor or provider markets, and it remains unknown whether some providers may actually raise prices after learning about higher rates negotiated by competitors.8,9

Another issue is hospital participation. Early evidence suggests that most hospitals have not complied with the letter or spirit of the regulation.

Despite its limitations, this policy represents a meaningful advance for healthcare competition and patient empowerment. Additionally, it signals federal willingness to address the lack of price transparency as a source of widespread patient and clinician frustration—a commitment that will be needed to sustain this policy and implement additional measures in the future.

COMMENTARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

CMS could consider five steps to augment the policy and maximize transparency and value for patients.

First, CMS could consider increasing daily nonparticipation penalties. Hospitals, particularly those in areas with less competition, have less incentive to participate given meager current penalties. Because the magnitude needed to compel action remains unknown, CMS could gradually escalate penalties over time until there is broader participation across hospitals.

Second, policymakers could aggregate price information centrally, organize the data around patients’ clinical scenarios, and advertise its availability. Currently, this information is scattered and time-consuming for hospitalists and patients to gather for decision-making. Additionally, CMS could encourage the development of third-party tools that aggregate and analyze machine-readable price data or require that prices be posted at the point of service.

Third, CMS could revise the policy to include quality as well as price information. Price alone does not offer a full enough picture of what consumers can expect from hospitals for shoppable services. Pairing price and quality information is better aligned to addressing costs in the context of value, rather than cost-cutting for its own purposes.

Fourth, over time, CMS could expand the list of services and sites required to report (eg, clinics and ambulatory surgical centers as well as hospitals).

Fifth, CMS rule-makers could set reporting standards and contextualize price information in common clinical scenarios. Patients may have difficulty shopping for complex healthcare services without understanding how they apply in different clinical situations. Decision-making would also be aided by reporting standards—for instance, for how prices are displayed and whether they include certain fees (eg, professional fees, pathology studies).

WHAT SHOULD I TELL MY PATIENT?

Hospitalists planning follow-up care should inform patients that price information is increasingly available and encourage them to search on the internet or contact hospital billing offices to request information (eg, discounted cash prices and minimum negotiated charges) before obtaining elective services after discharge. Hospitalists can also encourage patients to discuss shoppable services with their primary care physicians to understand the clinical context and make high-value decisions. Hospitalists who wish to build communication skills discussing costs with patients can increasingly find resources for these conversations and request that prices be displayed in the electronic health record for this purpose.13,14 As conversations occur, hospitalists should seek to understand other factors, such as convenience and continuity relationships, that might influence choices.

CONCLUSIONS

Starting in 2021, CMS policy requires that hospitals report prices for services such as the endoscopy recommended for the patient in the scenario. Though the policy gives patients new hope for greater transparency and better prices, additional steps are needed to help patients and hospitalists achieve these benefits.

CLINICAL SCENARIO

A 59-year-old man is observed in the hospital for substernal chest pain initially concerning for angina. Serial troponin testing is negative, and based on additional history of intermittent dysphagia, an elective upper endoscopy is recommended after discharge. The patient does not have health insurance and expresses anxiety about the cost of endoscopy. He asks how he could compare the costs at different hospitals. How do federal price transparency rules assist the hospitalist in addressing this patient’s question?

BACKGROUND AND HISTORY

Healthcare costs continue to rise in the United States despite mounting concerns about wasteful spending and unaffordability.1 One contributor is a lack of price transparency.2 In theory, price transparency allows individuals to shop for services, spurring competition and lower prices. However, healthcare prices have historically been opaque to both physicians and patients; unlike other licensed professionals who provide clients estimates for their work (eg, lawyers, electricians), physicians are rarely able to offer patients real-time insight or guidance about costs, which most patients discover only when the bill arrives. The situation is particularly problematic for patients who bear higher out-of-pocket costs, such as the uninsured or those with high-deductible health plans.3

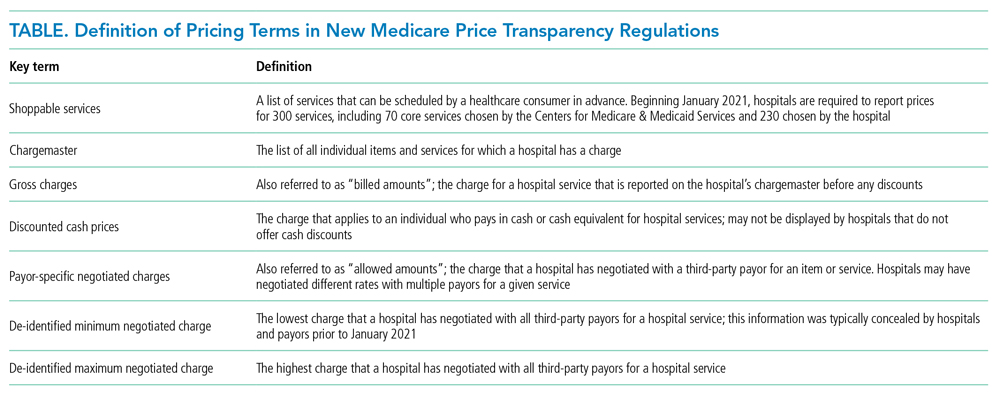

Decades of work to improve healthcare price transparency have unfortunately borne little fruit. Multiple states and organizations have attempted to disseminate price information on comparison websites.4 These efforts only modestly reduced some prices, with benefits confined to elective, single-episode, commodifiable services such as magnetic resonance imaging scans.5 The Affordable Care Act required hospitals to publish standard charges, also called a chargemaster (Table).6 However, chargemaster fees are notoriously inflated and inaccessible at the point of service, undercutting transparency.

POLICY IN CLINICAL PRACTICE

Beginning January 2021, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) required all hospitals to publish negotiated prices—including payor-specific negotiated charges—for 300 “shoppable services” (Table).6 The list must include 70 common CMS-specified services, such as a basic metabolic panel, upper endoscopy, and prostate biopsy, as well as another 230 services that each hospital determines relevant to its patient population.

In circumstances where hospitals have negotiated different prices for a service, they must list each third-party payor and their payor-specific charge. The information must be prominently displayed, accessible without requiring the patient to enter personal information, and provided in a machine-readable file. CMS may impose a $300 daily penalty on hospitals failing to comply with the policy. Of note, the policy does not apply to clinics or ambulatory surgery centers.

As more hospitals share data, this policy will directly benefit both patients and physicians. It can benefit patients with the time, foresight, and ability to search for the lowest price for shoppable services. Other patients may also benefit indirectly, to the extent that insurers and other purchasers apply this information to negotiate lower and more uniform prices. Decreased price variation may also encourage hospitals to compete on quality to distinguish the value of their services. Hospitalists could benefit through the ability to directly help patients locate price information.

Despite these potential benefits, the policy has limitations. Price information about shoppable services is most useful for discharge planning, and other solutions are needed to address transparency before and during unplanned admissions. Patients who prioritize continuity with a hospital or physician may be less price sensitive, particularly for more complex services. Patients with commercial insurance may be shielded from cost considerations and personal incentives to comparison shop. Interpreting hospitals’ estimates remains difficult, as it can be unclear if professional fees are included or if certain prices are offered to outpatients.7 Price information is not accompanied by corresponding quality data. Additionally, price transparency may also fail to lower prices in heavily concentrated payor or provider markets, and it remains unknown whether some providers may actually raise prices after learning about higher rates negotiated by competitors.8,9

Another issue is hospital participation. Early evidence suggests that most hospitals have not complied with the letter or spirit of the regulation.

Despite its limitations, this policy represents a meaningful advance for healthcare competition and patient empowerment. Additionally, it signals federal willingness to address the lack of price transparency as a source of widespread patient and clinician frustration—a commitment that will be needed to sustain this policy and implement additional measures in the future.

COMMENTARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

CMS could consider five steps to augment the policy and maximize transparency and value for patients.

First, CMS could consider increasing daily nonparticipation penalties. Hospitals, particularly those in areas with less competition, have less incentive to participate given meager current penalties. Because the magnitude needed to compel action remains unknown, CMS could gradually escalate penalties over time until there is broader participation across hospitals.

Second, policymakers could aggregate price information centrally, organize the data around patients’ clinical scenarios, and advertise its availability. Currently, this information is scattered and time-consuming for hospitalists and patients to gather for decision-making. Additionally, CMS could encourage the development of third-party tools that aggregate and analyze machine-readable price data or require that prices be posted at the point of service.

Third, CMS could revise the policy to include quality as well as price information. Price alone does not offer a full enough picture of what consumers can expect from hospitals for shoppable services. Pairing price and quality information is better aligned to addressing costs in the context of value, rather than cost-cutting for its own purposes.

Fourth, over time, CMS could expand the list of services and sites required to report (eg, clinics and ambulatory surgical centers as well as hospitals).

Fifth, CMS rule-makers could set reporting standards and contextualize price information in common clinical scenarios. Patients may have difficulty shopping for complex healthcare services without understanding how they apply in different clinical situations. Decision-making would also be aided by reporting standards—for instance, for how prices are displayed and whether they include certain fees (eg, professional fees, pathology studies).

WHAT SHOULD I TELL MY PATIENT?

Hospitalists planning follow-up care should inform patients that price information is increasingly available and encourage them to search on the internet or contact hospital billing offices to request information (eg, discounted cash prices and minimum negotiated charges) before obtaining elective services after discharge. Hospitalists can also encourage patients to discuss shoppable services with their primary care physicians to understand the clinical context and make high-value decisions. Hospitalists who wish to build communication skills discussing costs with patients can increasingly find resources for these conversations and request that prices be displayed in the electronic health record for this purpose.13,14 As conversations occur, hospitalists should seek to understand other factors, such as convenience and continuity relationships, that might influence choices.

CONCLUSIONS

Starting in 2021, CMS policy requires that hospitals report prices for services such as the endoscopy recommended for the patient in the scenario. Though the policy gives patients new hope for greater transparency and better prices, additional steps are needed to help patients and hospitalists achieve these benefits.

1. Shrank WH, Rogstad TL, Parekh N. Waste in the US health care system: estimated costs and potential for savings. JAMA. 2019;322(15):1501-1509. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.13978

2. Wetzell S. Transparency: a needed step towards health care affordability. American Health Policy Institute. March 2014. Accessed August 26, 2021. https://www.americanhealthpolicy.org/Content/documents/resources/Transparency%20Study%201%20-%20The%20Need%20for%20Health%20Care%20Transparency.pdf

3. Mehrotra A, Dean KM, Sinaiko AD, Sood N. Americans support price shopping for health care, but few actually seek out price information. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(8):1392-1400. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1471

4. Kullgren JT, Duey KA, Werner RM. A census of state health care price transparency websites. JAMA. 2013;309(23):2437-2438. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.6557

5. Brown ZY. Equilibrium effects of health care price information. Rev Econ Stat. 2019;101(4):699-712. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_00765

6. Medicare and Medicaid Programs: CY 2020 hospital outpatient PPS policy changes and payment rates and ambulatory surgical center payment system policy changes and payment rates. Price transparency requirements for hospitals to make standard charges public. 45 CFR §180.20 (2019).

7. Kurani N, Ramirez G, Hudman J, Cox C, Kamal R. Early results from federal price transparency rule show difficulty in estimating the cost of care. Peterson-Kaiser Family Foundation. April 9, 2021. Accessed August 26, 2021. https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/brief/early-results-from-federal-price-transparency-rule-show-difficultly-in-estimating-the-cost-of-care/

8. Miller BJ, Mandelberg MC, Griffith NC, Ehrenfeld JM. Price transparency: empowering patient choice and promoting provider competition. J Med Syst. 2020;44(4):80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-020-01553-2

9. Glied S. Price transparency–promise and peril. JAMA. 2021;325(15):1496-1497. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.4640

10. Haque W, Ahmadzada M, Allahrakha H, Haque E, Hsiehchen D. Transparency, accessibility, and variability of US hospital price data. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(5):e2110109. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.10109

11. Henderson M, Mouslim MC. Low compliance from big hospitals on CMS’s hospital price transparency rule. Health Affairs Blog. March 16, 2021. Accessed August 26, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1377/hblog20210311.899634

12. McGinty T, Wilde Mathews A, Evans M. Hospitals hide pricing data from search results. The Wall Street Journal. March 22, 2021. Accessed August 26, 2021. https://www.wsj.com/articles/hospitals-hide-pricing-data-from-search-results-11616405402

13. Dine CJ, Masi D, Smith CD. Tools to help overcome barriers to cost-of-care conversations. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(9 suppl):S36-S38. https://doi.org/10.7326/M19-0778

14. Miller BJ, Slota JM, Ehrenfeld JM. Redefining the physician’s role in cost-conscious care: the potential role of the electronic health record. JAMA. 2019;322(8):721-722. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.9114

1. Shrank WH, Rogstad TL, Parekh N. Waste in the US health care system: estimated costs and potential for savings. JAMA. 2019;322(15):1501-1509. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.13978

2. Wetzell S. Transparency: a needed step towards health care affordability. American Health Policy Institute. March 2014. Accessed August 26, 2021. https://www.americanhealthpolicy.org/Content/documents/resources/Transparency%20Study%201%20-%20The%20Need%20for%20Health%20Care%20Transparency.pdf

3. Mehrotra A, Dean KM, Sinaiko AD, Sood N. Americans support price shopping for health care, but few actually seek out price information. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(8):1392-1400. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1471

4. Kullgren JT, Duey KA, Werner RM. A census of state health care price transparency websites. JAMA. 2013;309(23):2437-2438. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.6557

5. Brown ZY. Equilibrium effects of health care price information. Rev Econ Stat. 2019;101(4):699-712. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_00765

6. Medicare and Medicaid Programs: CY 2020 hospital outpatient PPS policy changes and payment rates and ambulatory surgical center payment system policy changes and payment rates. Price transparency requirements for hospitals to make standard charges public. 45 CFR §180.20 (2019).

7. Kurani N, Ramirez G, Hudman J, Cox C, Kamal R. Early results from federal price transparency rule show difficulty in estimating the cost of care. Peterson-Kaiser Family Foundation. April 9, 2021. Accessed August 26, 2021. https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/brief/early-results-from-federal-price-transparency-rule-show-difficultly-in-estimating-the-cost-of-care/

8. Miller BJ, Mandelberg MC, Griffith NC, Ehrenfeld JM. Price transparency: empowering patient choice and promoting provider competition. J Med Syst. 2020;44(4):80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-020-01553-2

9. Glied S. Price transparency–promise and peril. JAMA. 2021;325(15):1496-1497. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.4640

10. Haque W, Ahmadzada M, Allahrakha H, Haque E, Hsiehchen D. Transparency, accessibility, and variability of US hospital price data. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(5):e2110109. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.10109

11. Henderson M, Mouslim MC. Low compliance from big hospitals on CMS’s hospital price transparency rule. Health Affairs Blog. March 16, 2021. Accessed August 26, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1377/hblog20210311.899634

12. McGinty T, Wilde Mathews A, Evans M. Hospitals hide pricing data from search results. The Wall Street Journal. March 22, 2021. Accessed August 26, 2021. https://www.wsj.com/articles/hospitals-hide-pricing-data-from-search-results-11616405402

13. Dine CJ, Masi D, Smith CD. Tools to help overcome barriers to cost-of-care conversations. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(9 suppl):S36-S38. https://doi.org/10.7326/M19-0778

14. Miller BJ, Slota JM, Ehrenfeld JM. Redefining the physician’s role in cost-conscious care: the potential role of the electronic health record. JAMA. 2019;322(8):721-722. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.9114

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine