User login

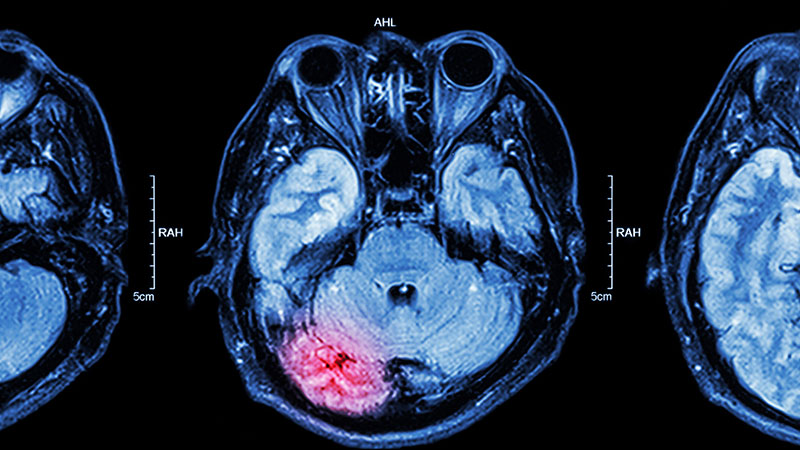

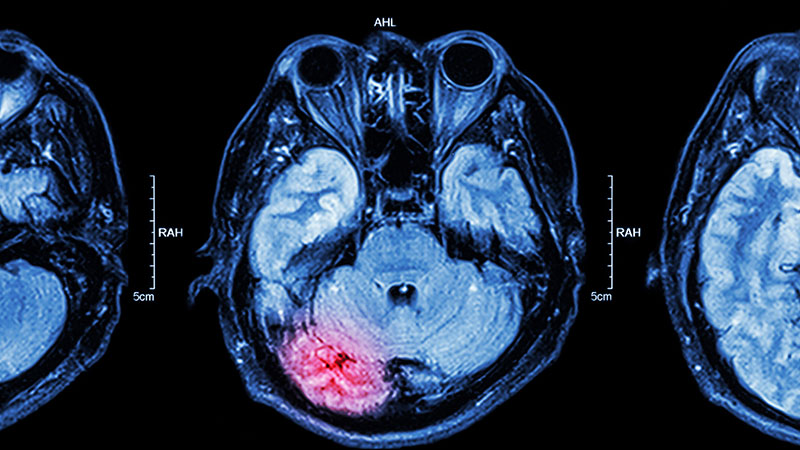

The correct diagnosis is adolescent posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), as the patient's symptoms — recurrent nightmares, flashbacks, hypervigilance, and avoidance behaviors — are closely linked to her recent traumatic experience, fitting the clinical profile of PTSD. The MRI finding, although abnormal, does not correlate with a neurologic cause for her symptoms and may be incidental.

Temporal lobe epilepsy can cause behavioral changes but does not explain the specific PTSD symptoms like flashbacks and nightmares.

Chronic migraine could explain the headaches but not the full spectrum of PTSD symptoms.

Major depressive disorder could account for some of the emotional and social symptoms but lacks the characteristic re-experiencing and avoidance behaviors typical of PTSD.

Adolescent PTSD is a significant public health concern, causing significant distress to a small portion of the youth population. By late adolescence, approximately two thirds of youths have been exposed to trauma, and 8% of these individuals meet the criteria for PTSD by age 18. The incidence is exceptionally high in cases of sexual abuse and assault, with rates reaching up to 40%. PTSD in adolescents is associated with severe psychological distress, reduced academic performance, and a high rate of comorbidities, including anxiety and depression. There are specific populations (including children who are evacuated from home, asylum seekers, etc.) that show higher rates of PTSD.

PTSD can lead to chronic impairments, comorbid psychiatric disorders, and an increased risk for suicide, with cases documented in toddlers as young as 1 year old. Thus, it is important to consider the individual's background and social history, as older children with PTSD may present with symptoms from early childhood trauma, often distant from the time of clinical evaluation.

Intrusion symptoms are a hallmark of PTSD, characterized by persistent and uncontrollable thoughts, dreams, and emotional reactions related to the traumatic event. These symptoms distinguish PTSD from other anxiety and mood disorders. Children with PTSD often experience involuntary, distressing thoughts and memories triggered by trauma cues, such as sights, sounds, or smells associated with the traumatic event. In younger children, these intrusive thoughts may manifest through repetitive play that re-enacts aspects of the trauma.

Nightmares are also common, although in children the content may not always directly relate to the traumatic event. Chronic nightmares contribute to sleep disturbances, exacerbating PTSD symptoms. Trauma reminders, which can be both internal (thoughts, memories) and external (places, sensory experiences), can provoke severe distress and physiologic reactions.

Avoidance symptoms often develop as a coping mechanism in response to distressing re-experiencing symptoms. Children may avoid thoughts, feelings, and memories of the traumatic event or people, places, and activities associated with the trauma. In young children, avoidance may manifest as restricted play or reduced exploration of their environment.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR) outlines specific criteria for diagnosing PTSD in individuals over 6 years old, which includes exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence, and the presence of symptoms such as intrusion, avoidance, negative mood alterations, and heightened arousal. The DSM-5-TR provides tailored diagnostic criteria for developmental differences in symptom expression for children under 6.

Managing PTSD in children requires a patient-specific approach, with an emphasis on obtaining consent from both the patient and guardian. The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) recommends psychotherapy as the first-line treatment for pediatric PTSD. However, patients with severe symptoms or comorbidities may initially be unable to engage in meaningful therapy and may require medication to stabilize symptoms before starting psychotherapy.

Trauma-focused psychotherapy, including cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), exposure-based therapy, and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy, is the preferred treatment for PTSD. Clinical studies have shown that patients receiving trauma-focused psychotherapy experience more remarkable symptom improvement than those who do not receive treatment and, in children, psychotherapy generally yields better outcomes than pharmacotherapy.

While selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors like sertraline and paroxetine are FDA-approved for PTSD treatment in adults, their efficacy in children often produces outcomes similar to those of placebo. Medications are typically reserved for severe symptoms and are used as an off-label treatment in pediatric cases. Pharmacologic management may be necessary when the severity of symptoms prevents the use of trauma-focused psychotherapy or requires immediate stabilization.

Heidi Moawad, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medical Education, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio.

Heidi Moawad, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The correct diagnosis is adolescent posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), as the patient's symptoms — recurrent nightmares, flashbacks, hypervigilance, and avoidance behaviors — are closely linked to her recent traumatic experience, fitting the clinical profile of PTSD. The MRI finding, although abnormal, does not correlate with a neurologic cause for her symptoms and may be incidental.

Temporal lobe epilepsy can cause behavioral changes but does not explain the specific PTSD symptoms like flashbacks and nightmares.

Chronic migraine could explain the headaches but not the full spectrum of PTSD symptoms.

Major depressive disorder could account for some of the emotional and social symptoms but lacks the characteristic re-experiencing and avoidance behaviors typical of PTSD.

Adolescent PTSD is a significant public health concern, causing significant distress to a small portion of the youth population. By late adolescence, approximately two thirds of youths have been exposed to trauma, and 8% of these individuals meet the criteria for PTSD by age 18. The incidence is exceptionally high in cases of sexual abuse and assault, with rates reaching up to 40%. PTSD in adolescents is associated with severe psychological distress, reduced academic performance, and a high rate of comorbidities, including anxiety and depression. There are specific populations (including children who are evacuated from home, asylum seekers, etc.) that show higher rates of PTSD.

PTSD can lead to chronic impairments, comorbid psychiatric disorders, and an increased risk for suicide, with cases documented in toddlers as young as 1 year old. Thus, it is important to consider the individual's background and social history, as older children with PTSD may present with symptoms from early childhood trauma, often distant from the time of clinical evaluation.

Intrusion symptoms are a hallmark of PTSD, characterized by persistent and uncontrollable thoughts, dreams, and emotional reactions related to the traumatic event. These symptoms distinguish PTSD from other anxiety and mood disorders. Children with PTSD often experience involuntary, distressing thoughts and memories triggered by trauma cues, such as sights, sounds, or smells associated with the traumatic event. In younger children, these intrusive thoughts may manifest through repetitive play that re-enacts aspects of the trauma.

Nightmares are also common, although in children the content may not always directly relate to the traumatic event. Chronic nightmares contribute to sleep disturbances, exacerbating PTSD symptoms. Trauma reminders, which can be both internal (thoughts, memories) and external (places, sensory experiences), can provoke severe distress and physiologic reactions.

Avoidance symptoms often develop as a coping mechanism in response to distressing re-experiencing symptoms. Children may avoid thoughts, feelings, and memories of the traumatic event or people, places, and activities associated with the trauma. In young children, avoidance may manifest as restricted play or reduced exploration of their environment.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR) outlines specific criteria for diagnosing PTSD in individuals over 6 years old, which includes exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence, and the presence of symptoms such as intrusion, avoidance, negative mood alterations, and heightened arousal. The DSM-5-TR provides tailored diagnostic criteria for developmental differences in symptom expression for children under 6.

Managing PTSD in children requires a patient-specific approach, with an emphasis on obtaining consent from both the patient and guardian. The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) recommends psychotherapy as the first-line treatment for pediatric PTSD. However, patients with severe symptoms or comorbidities may initially be unable to engage in meaningful therapy and may require medication to stabilize symptoms before starting psychotherapy.

Trauma-focused psychotherapy, including cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), exposure-based therapy, and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy, is the preferred treatment for PTSD. Clinical studies have shown that patients receiving trauma-focused psychotherapy experience more remarkable symptom improvement than those who do not receive treatment and, in children, psychotherapy generally yields better outcomes than pharmacotherapy.

While selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors like sertraline and paroxetine are FDA-approved for PTSD treatment in adults, their efficacy in children often produces outcomes similar to those of placebo. Medications are typically reserved for severe symptoms and are used as an off-label treatment in pediatric cases. Pharmacologic management may be necessary when the severity of symptoms prevents the use of trauma-focused psychotherapy or requires immediate stabilization.

Heidi Moawad, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medical Education, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio.

Heidi Moawad, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The correct diagnosis is adolescent posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), as the patient's symptoms — recurrent nightmares, flashbacks, hypervigilance, and avoidance behaviors — are closely linked to her recent traumatic experience, fitting the clinical profile of PTSD. The MRI finding, although abnormal, does not correlate with a neurologic cause for her symptoms and may be incidental.

Temporal lobe epilepsy can cause behavioral changes but does not explain the specific PTSD symptoms like flashbacks and nightmares.

Chronic migraine could explain the headaches but not the full spectrum of PTSD symptoms.

Major depressive disorder could account for some of the emotional and social symptoms but lacks the characteristic re-experiencing and avoidance behaviors typical of PTSD.

Adolescent PTSD is a significant public health concern, causing significant distress to a small portion of the youth population. By late adolescence, approximately two thirds of youths have been exposed to trauma, and 8% of these individuals meet the criteria for PTSD by age 18. The incidence is exceptionally high in cases of sexual abuse and assault, with rates reaching up to 40%. PTSD in adolescents is associated with severe psychological distress, reduced academic performance, and a high rate of comorbidities, including anxiety and depression. There are specific populations (including children who are evacuated from home, asylum seekers, etc.) that show higher rates of PTSD.

PTSD can lead to chronic impairments, comorbid psychiatric disorders, and an increased risk for suicide, with cases documented in toddlers as young as 1 year old. Thus, it is important to consider the individual's background and social history, as older children with PTSD may present with symptoms from early childhood trauma, often distant from the time of clinical evaluation.

Intrusion symptoms are a hallmark of PTSD, characterized by persistent and uncontrollable thoughts, dreams, and emotional reactions related to the traumatic event. These symptoms distinguish PTSD from other anxiety and mood disorders. Children with PTSD often experience involuntary, distressing thoughts and memories triggered by trauma cues, such as sights, sounds, or smells associated with the traumatic event. In younger children, these intrusive thoughts may manifest through repetitive play that re-enacts aspects of the trauma.

Nightmares are also common, although in children the content may not always directly relate to the traumatic event. Chronic nightmares contribute to sleep disturbances, exacerbating PTSD symptoms. Trauma reminders, which can be both internal (thoughts, memories) and external (places, sensory experiences), can provoke severe distress and physiologic reactions.

Avoidance symptoms often develop as a coping mechanism in response to distressing re-experiencing symptoms. Children may avoid thoughts, feelings, and memories of the traumatic event or people, places, and activities associated with the trauma. In young children, avoidance may manifest as restricted play or reduced exploration of their environment.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR) outlines specific criteria for diagnosing PTSD in individuals over 6 years old, which includes exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence, and the presence of symptoms such as intrusion, avoidance, negative mood alterations, and heightened arousal. The DSM-5-TR provides tailored diagnostic criteria for developmental differences in symptom expression for children under 6.

Managing PTSD in children requires a patient-specific approach, with an emphasis on obtaining consent from both the patient and guardian. The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) recommends psychotherapy as the first-line treatment for pediatric PTSD. However, patients with severe symptoms or comorbidities may initially be unable to engage in meaningful therapy and may require medication to stabilize symptoms before starting psychotherapy.

Trauma-focused psychotherapy, including cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), exposure-based therapy, and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy, is the preferred treatment for PTSD. Clinical studies have shown that patients receiving trauma-focused psychotherapy experience more remarkable symptom improvement than those who do not receive treatment and, in children, psychotherapy generally yields better outcomes than pharmacotherapy.

While selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors like sertraline and paroxetine are FDA-approved for PTSD treatment in adults, their efficacy in children often produces outcomes similar to those of placebo. Medications are typically reserved for severe symptoms and are used as an off-label treatment in pediatric cases. Pharmacologic management may be necessary when the severity of symptoms prevents the use of trauma-focused psychotherapy or requires immediate stabilization.

Heidi Moawad, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medical Education, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio.

Heidi Moawad, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 15-year-old girl presented to the emergency department with complaints of persistent headaches, nightmares, and difficulty concentrating in school over the past 3 months. The patient had recently experienced a traumatic event, a severe car accident in which a close friend was critically injured. Since the incident, the patient has been exhibiting increased irritability, avoidance of activities that she previously enjoyed, and a noticeable withdrawal from social interactions. Additionally, she reported recurrent flashbacks to the accident, often triggered by sounds resembling car engines. On physical examination, the patient appeared anxious and exhibited hypervigilance. An MRI of the brain was performed to rule out any organic causes of her symptoms, revealing an area of increased signal intensity in the left cerebellar hemisphere (as highlighted in the image).