User login

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Diagnostic tests

- Complications of PID

- CDC treatment regimens

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is an ascending polymicrobial infection of the female upper reproductive tract that primarily affects sexually active women ages 15 to 29. Around 5% of sexually active women in the United States were treated for PID from 2011-2013.1 The rates and severity of PID have declined in North America and Western Europe due to overall decrease in sexually transmitted infection (STI) rates, improved screening initiatives for Chlamydia trachomatis, better treatment compliance secondary to increased access to antibiotics, and diagnostic tests with higher sensitivity.2 Despite this rate reduction, PID remains a major public health concern given the significant long-term complications, which include infertility, ectopic pregnancy, and chronic pelvic pain.3

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

PID is caused by sexually transmitted bacteria or enteric organisms that have spread to internal reproductive organs. Historically, the two most common pathogens identified in cases of PID have been Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae; however, the decline in rates of gonorrhea has led to a diminished role for N gonorrhoeae (though it continues to be associated with more severe cases).4,5

More recent studies have suggested a shift in the causative organisms; less than half of women diagnosed with acute PID test positive for either N gonorrhoeae or C trachomatis.6 Emerging infectious agents associated with PID include Mycoplasma genitalium, Gardnerella vaginalis, and bacterial vaginosis–associated bacteria.5,7,8-10

RISK FACTORS

Women ages 15 to 25 are at an increased risk for PID. The high prevalence in this age group may be attributable to high-risk behaviors, including a high number of sexual partners, high frequency of new sexual partners, and engagement in sexual intercourse without condoms.11

Taking an accurate sexual history is imperative. Clinicians should maintain a high level of suspicion for PID in women with a history of the disease, as 25% will experience recurrence.12

Clinicians should not be deterred from screening for STIs and cervical cancer in women who report having sex with other women. In addition, transgender patients should be assessed for STIs and HIV-related risks based on current anatomy sexual practices.13

PHYSICAL EXAM

While some cases of PID are asymptomatic, the typical presentation includes bilateral abdominal pain and/or pelvic pain, with onset during or shortly after menses. The pain often worsens with movement and coitus. Associated signs and symptoms include abnormal uterine bleeding or vaginal discharge; dysuria; fever and chills; frequent urination; lower back pain; and nausea and/or vomiting.14,15

All females suspected of having PID should undergo both a bimanual exam and a speculum exam. On bimanual examination, adnexal tenderness has the highest sensitivity (93% to 95.5%) for ruling out acute PID, whereas on speculum exam, purulent endocervical discharge has the highest specificity (93%).16,17 Bimanual exam findings suggestive of PID include cervical motion tenderness, uterine tenderness, and/or adnexal tenderness. Suggestive speculum exam findings include abnormal discoloration or texture of the cervix and/or endocervical mucopurulent discharge.5,16,17

One cardinal rule that should not be overlooked is that all females of reproductive age who present with abdominal pain and/or pelvic pain should take a pregnancy test to rule out ectopic pregnancy and any other pregnancy-related complications.

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of PID relies on clinical judgement and a high index of suspicion.5,18 The CDC’s diagnostic criteria for acute PID include

- Sexually active female AND

- Pelvic or lower abdominal pain AND

- Cervical motion tenderness OR uterine tenderness OR adnexal tenderness.5

Additional findings that support the diagnosis include

- Abnormal cervical mucopurulent discharge or cervical friability

- Abundant white blood cells (WBCs) on saline microscopy of vaginal fluid

- Elevated C-reactive protein

- Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- Laboratory documentation of infection with C trachomatis or N gonorrhea

- Oral temperature > 101°F.5,18

The CDC notes that the first two findings (mucopurulent discharge and evidence of WBCs on microscopy) occur in most women with PID; in their absence, the diagnosis is unlikely and other sources of pain should be considered.5 The differential for PID includes acute appendicitis; adhesions; carcinoid tumor; cholecystitis; ectopic pregnancy; endometriosis; inflammatory bowel disease; and ovarian cyst.19

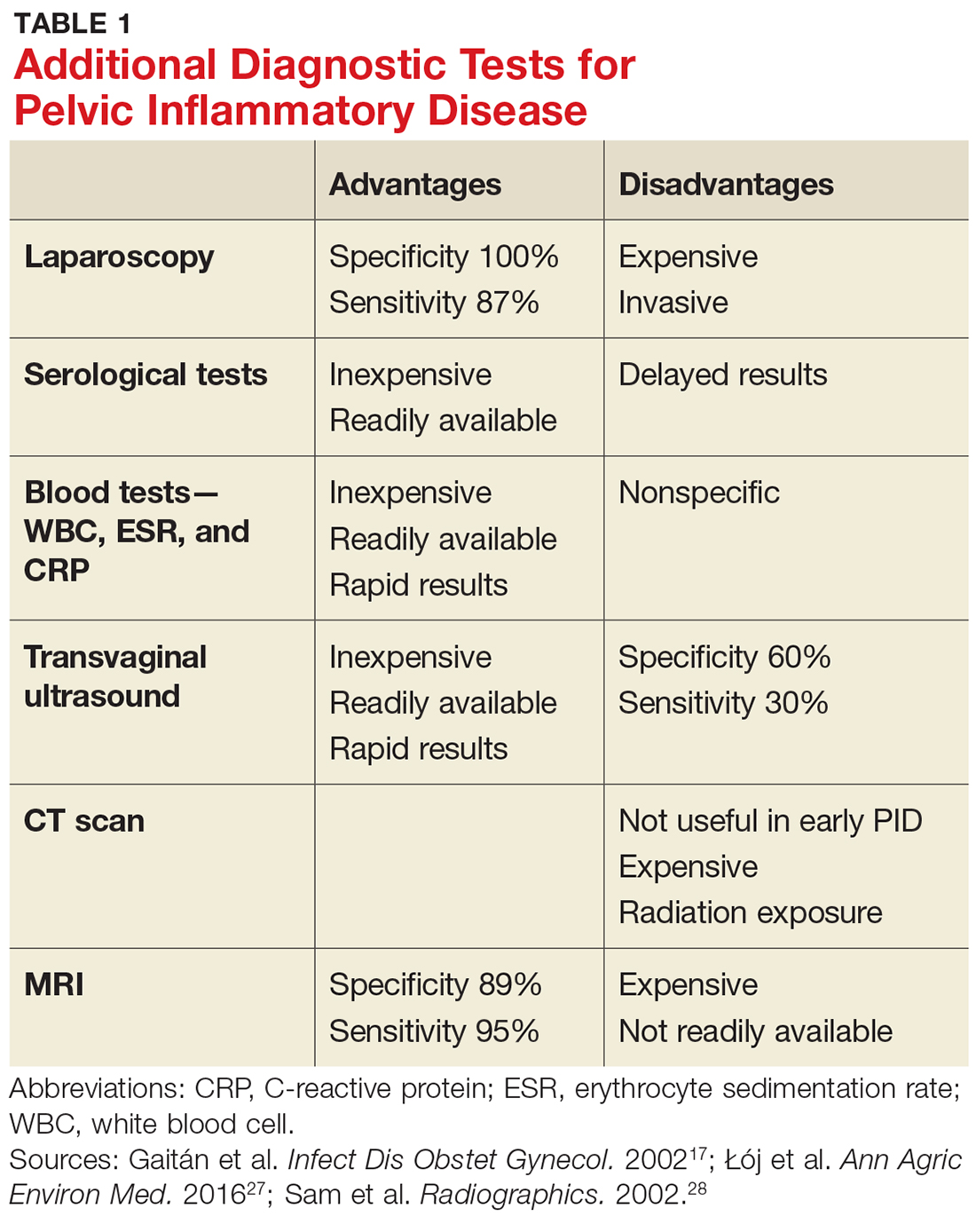

Given the variability in presentation, clinicians may find it useful to perform further diagnostic testing. There are additional laboratory tests that may be ordered for patients with a suspected diagnosis of PID (see Table 1).

TREATMENT

According to the CDC’s 2015 treatment guidelines for PID, a negative endocervical exam and negative microbial screening do not rule out an upper reproductive tract infection. Therefore, all sexually active women who present with lower abdominal pain and/or pelvic pain and have evidence of cervical motion, uterine, or adnexal tenderness on bimanual exam should be treated immediately.5

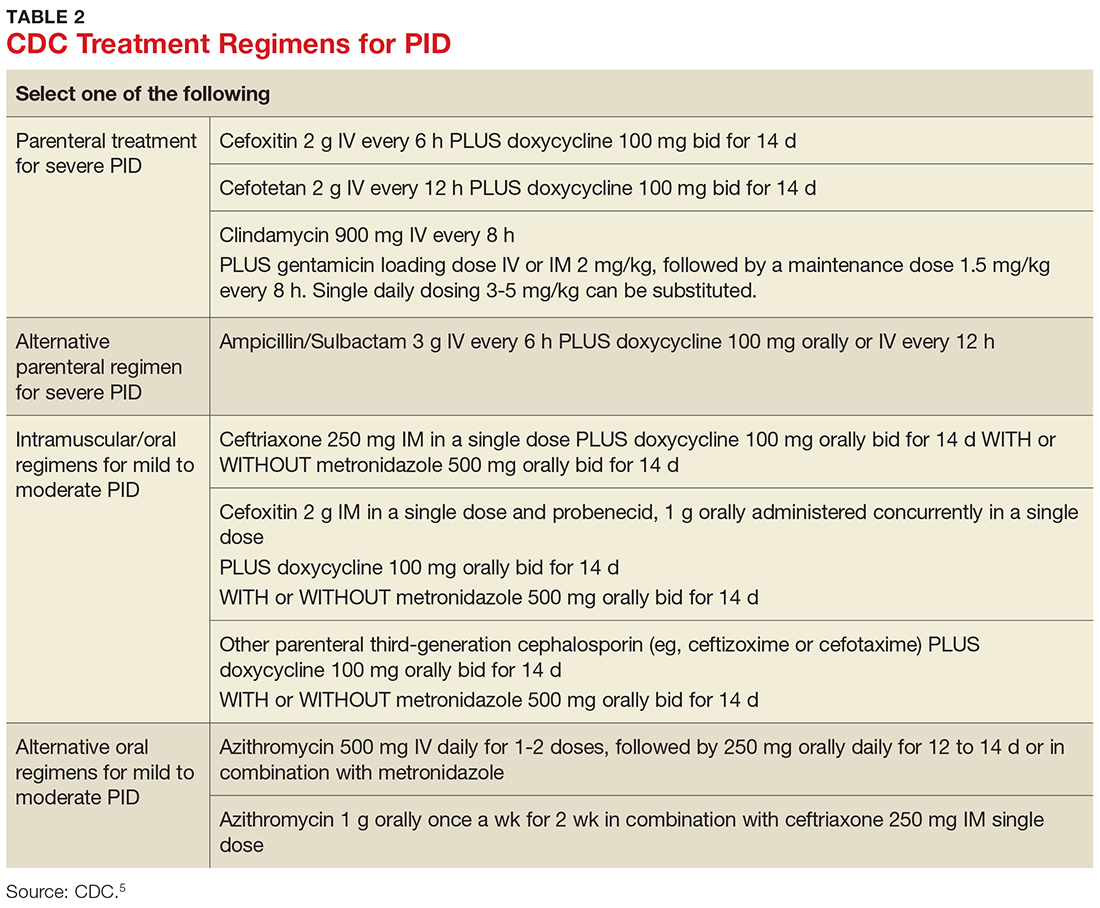

Treatment guidelines are outlined in Table 2. The polymicrobial nature of PID requires gram-negative antibiotic coverage, such as doxycycline plus a second/third-generation cephalosporin.5 Clinicians should note that cefoxitin, a second-generation cephalosporin, is recommended as firstline therapy for inpatients, as it has better anaerobic coverage than ceftriaxone.19 A targeted change in antibiotic coverage—such as inclusion of a macrolide and/or metronidazole—might be necessary if a causative organism is identified by culture.7

Treatment is indicated for all patients with a presumptive diagnosis of PID regardless of symptoms or exam findings, as PID may be asymptomatic and long-term sequelae (eg, infertility, ectopic pregnancy) are often irreversible. At-risk patients include sexually active adolescents, women with multiple sexual partners, women with a history of STI, those whose sexual partner has an STI, and women living in communities with a high prevalence of disease.20,21

Women being treated for PID should be advised to abstain from sexual intercourse until symptoms have resolved, treatment is completed, and any sexual partners have been treated as well. It is essential to emphasize to patients (and their partners) the importance of compliance to treatment regimens and the risk for PID co-infection and reinfection, as recurrence leads to an increase in long-term complications.5

Treatment of sexual partners. The CDC instructs that a woman’s most recent partner should be treated if she had sexual intercourse within 60 days of onset of symptoms or diagnosis. Furthermore, men who have had sexual contact with a woman who has PID in the 60 days prior to onset of her symptoms should be evaluated, tested, and treated for chlamydia and gonorrhea, regardless of the etiology of PID or the pathogens isolated from the woman.5

Admission criteria. Hospitalization should be based on provider judgment despite patient age. The suggested admission criteria include surgical emergency (eg, appendicitis), tubo-ovarian abscess, pregnancy, severe illness, nausea and vomiting, high fever, inability to follow or tolerate an outpatient oral regimen, and lack of clinical response to oral antimicrobial therapy.5

Follow-up care. Clinical improvement (ie, reduction in abdominal, uterine, adnexal, and cervical motion tenderness) should occur within 72 hours of antimicrobial therapy initiation. If it does not, hospital admission or adjustment in antimicrobial regimen should be considered, as well as additional diagnostic testing (eg, laparoscopy). In addition, all women with chlamydial- or gonococcal-related PID should return in three months for surveillance testing.22

COMPLICATIONS

Long-term complications—including infertility, chronic pelvic pain, and ectopic pregnancy—may occur, even when there has been a clinical response to adequate treatment. Data from the PID Evaluation and Clinical Health (PEACH) study were analyzed to assess long-term sequelae at seven years postdiagnosis and treatment. The researchers found that about 21% of women experienced recurrent PID, 19% developed infertility, and 42% reported chronic pelvic pain.3 Other research has also shown that repeat episodes of PID and delayed treatment increase the risk for long-term complications.23,24

SCREENING AND PREVENTION

Ten percent of women with an untreated STI will go on to develop PID.4 It is imperative to educate patients on the dangers and consequences of STIs when they become sexually active. Adolescents benefit the most from preventive education; this group is twice as likely as any other age group to be diagnosed with PID due to their inclination toward risky sexual behavior. Additionally, younger women tend to have a more friable cervix, increasing their risk for infection.25,26 Providers should promote safe sexual practices, such as condom use and less frequent partner exchange, in order to reduce STI exposure.

In 2015, the rate of reported cases of C trachomatis was 645.5 per 100,000 females, and of N gonorrheae, 107.2 per 100,000 females.23 The United States Preventive Services Task Force and the CDC recommend annual screening for chlamydia and gonorrhea in all sexually active women younger than 25, as well as sexually active women ages 25 and older who are considered at increased risk.5

CONCLUSION

PID is often difficult to diagnose, since patients may be asymptomatic or present with vague symptoms. Clinicians should maintain a high level of suspicion for PID in adolescent females due to the high incidence of STI exposure in this population. The best way to prevent long-term complications of PID is to prevent the first episode of PID and/or first exposure to STIs. Therefore, clinicians should be proactive in offering STI screenings to all sexually active patients younger than 25 who request care, regardless of their chief complaint, and educating patients on the potential long-term effects of PID and STIs.

1. Leichliter JS, Chandra A, Aral SO. Correlates of self-reported pelvic inflammatory disease treatment in sexually experienced reproductive-aged women in the United States, 1995 and 2006-2010. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(5):413-418.

2. Owusu-Edusei K Jr, Bohm MK, Chesson HW, Kent CK. Chlamydia screening and pelvic inflammatory disease: insights from exploratory time-series analyses. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(6):652-657.

3. Trent M, Bass D, Ness RB, Haggerty C. Recurrent PID, subsequent STI, and reproductive health outcomes: findings from the PID evaluation and clinical health (PEACH) study. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(9):879-881.

4. Mitchell C, Prabhu M. Pelvic inflammatory disease: current concepts in pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2013;27(4):793-809.

5. CDC. Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/pid.htm. Accessed July 13, 2017.

6. Burnett AM, Anderson CP, Zwank MD. Laboratory-confirmed gonorrhea and/or chlamydia rates in clinically diagnosed pelvic inflammatory disease and cervicitis. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30:1114–1117.

7. Bjartling C, Osser S, Persson K. The association between Mycoplasma genitalium and pelvic inflammatory disease after termination of pregnancy. BJOG. 2010;117(3):361-364.

8. Ness RB, Kip KE, Hillier SL, et al. A cluster analysis of bacterial vaginosis-associated microflora and pelvic inflammatory disease. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162(6):585-590.

9. Ness RB, Hillier SL, Kip KE, et al. Bacterial vaginosis and risk of pelvic inflammatory disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(4):761-769.

10. Cherpes TL, Wiesenfeld HC, Melan MA, et al. The associations between pelvic inflammatory disease, Trichomonas vaginalis infection, and positive herpes simplex virus type 2 serology. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(12):747-752.

11. Simms I, Stephenson JM, Mallinson H, et al. Risk factors associated with pelvic inflammatory disease. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82(6):452-457.

12. Schindlbeck C, Dziura D, Mylonas I. Diagnosis of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID): intra-operative findings and comparison of vaginal and intra-abdominal cultures. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;289(6):1263-1269.

13. CDC. 2015 sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/default.htm. Accessed September 6, 2017.

14. Korn AP, Hessol NA, Padian NS, et al. Risk factors for plasma cell endometritis among women with cervical Neisseria gonorrhoeae, cervical Chlamydia trachomatis, or bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178(5):987-990.

15. Wiesenfeld HC, Sweet RL, Ness RB, et al. Comparison of acute and subclinical pelvic inflammatory disease. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32(7):400-405.

16. Peipert JF, Ness RB, Blume J, et al. Clinical predictors of endometritis in women with symptoms and signs of pelvic inflammatory disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184(5):856-864.

17. Gaitán H, Angel E, Diaz R, et al. Accuracy of five different diagnostic techniques in mild-to-moderate pelvic inflammatory disease. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2002;10(4):171-180.

18. Tukeva TA, Aronen HJ, Karjalainen PT, et al. MR imaging in pelvic inflammatory disease: comparison with laparoscopy and US. Radiology. 1999;210(1):209-216.

19. Morino M, Pellegrino L, Castagna E, et al. Acute nonspecific abdominal pain. Ann Surg. 2006;244(6):881-888.

20. Woods JL, Scurlock AM, Hensel DJ. Pelvic inflammatory disease in the adolescent: understanding diagnosis and treatment as a health care provider. Pediatric Emergency Care. 2013;29(6):720-725.

21. LeFevre ML; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for chlamydia and gonorrhea: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(12):902-910.

22. Hosenfeld CB, Workowski KA, Berman S, et al. Repeat infection with Chlamydia and gonorrhea among females: a systematic review of the literature. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36(8):478-489.

23. CDC. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance. www.cdc.gov/std/stats15/STD-Surveillance-2015-print.pdf. Accessed July 13, 2017.

24. Hillis SD, Joesoef R, Marchbanks PA, et al. Delayed care of pelvic inflammatory disease as a risk factor for impaired fertility. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;168(5):1503-1509.

25. Goyal M, Hersh A, Luan X, et al. National trends in pelvic inflammatory disease among adolescents in the emergency department. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53(2):249-252.

26. Gray-Swain MR, Peipert JF. Pelvic inflammatory disease in adolescents. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2006;18(5):503-510.

27. Łój B, Brodowska A, Ciecwiez S, et al. The role of serological testing for Chlamydia trachomatis in differential diagnosis of pelvic pain. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2016;23(3):506-510.

28. Sam JW, Jacobs JE, Birnbaum BA. Spectrum of CT findings in acute pyogenic pelvic inflammatory disease. Radiographics. 2002;22(6):1327-1 334.

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Diagnostic tests

- Complications of PID

- CDC treatment regimens

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is an ascending polymicrobial infection of the female upper reproductive tract that primarily affects sexually active women ages 15 to 29. Around 5% of sexually active women in the United States were treated for PID from 2011-2013.1 The rates and severity of PID have declined in North America and Western Europe due to overall decrease in sexually transmitted infection (STI) rates, improved screening initiatives for Chlamydia trachomatis, better treatment compliance secondary to increased access to antibiotics, and diagnostic tests with higher sensitivity.2 Despite this rate reduction, PID remains a major public health concern given the significant long-term complications, which include infertility, ectopic pregnancy, and chronic pelvic pain.3

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

PID is caused by sexually transmitted bacteria or enteric organisms that have spread to internal reproductive organs. Historically, the two most common pathogens identified in cases of PID have been Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae; however, the decline in rates of gonorrhea has led to a diminished role for N gonorrhoeae (though it continues to be associated with more severe cases).4,5

More recent studies have suggested a shift in the causative organisms; less than half of women diagnosed with acute PID test positive for either N gonorrhoeae or C trachomatis.6 Emerging infectious agents associated with PID include Mycoplasma genitalium, Gardnerella vaginalis, and bacterial vaginosis–associated bacteria.5,7,8-10

RISK FACTORS

Women ages 15 to 25 are at an increased risk for PID. The high prevalence in this age group may be attributable to high-risk behaviors, including a high number of sexual partners, high frequency of new sexual partners, and engagement in sexual intercourse without condoms.11

Taking an accurate sexual history is imperative. Clinicians should maintain a high level of suspicion for PID in women with a history of the disease, as 25% will experience recurrence.12

Clinicians should not be deterred from screening for STIs and cervical cancer in women who report having sex with other women. In addition, transgender patients should be assessed for STIs and HIV-related risks based on current anatomy sexual practices.13

PHYSICAL EXAM

While some cases of PID are asymptomatic, the typical presentation includes bilateral abdominal pain and/or pelvic pain, with onset during or shortly after menses. The pain often worsens with movement and coitus. Associated signs and symptoms include abnormal uterine bleeding or vaginal discharge; dysuria; fever and chills; frequent urination; lower back pain; and nausea and/or vomiting.14,15

All females suspected of having PID should undergo both a bimanual exam and a speculum exam. On bimanual examination, adnexal tenderness has the highest sensitivity (93% to 95.5%) for ruling out acute PID, whereas on speculum exam, purulent endocervical discharge has the highest specificity (93%).16,17 Bimanual exam findings suggestive of PID include cervical motion tenderness, uterine tenderness, and/or adnexal tenderness. Suggestive speculum exam findings include abnormal discoloration or texture of the cervix and/or endocervical mucopurulent discharge.5,16,17

One cardinal rule that should not be overlooked is that all females of reproductive age who present with abdominal pain and/or pelvic pain should take a pregnancy test to rule out ectopic pregnancy and any other pregnancy-related complications.

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of PID relies on clinical judgement and a high index of suspicion.5,18 The CDC’s diagnostic criteria for acute PID include

- Sexually active female AND

- Pelvic or lower abdominal pain AND

- Cervical motion tenderness OR uterine tenderness OR adnexal tenderness.5

Additional findings that support the diagnosis include

- Abnormal cervical mucopurulent discharge or cervical friability

- Abundant white blood cells (WBCs) on saline microscopy of vaginal fluid

- Elevated C-reactive protein

- Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- Laboratory documentation of infection with C trachomatis or N gonorrhea

- Oral temperature > 101°F.5,18

The CDC notes that the first two findings (mucopurulent discharge and evidence of WBCs on microscopy) occur in most women with PID; in their absence, the diagnosis is unlikely and other sources of pain should be considered.5 The differential for PID includes acute appendicitis; adhesions; carcinoid tumor; cholecystitis; ectopic pregnancy; endometriosis; inflammatory bowel disease; and ovarian cyst.19

Given the variability in presentation, clinicians may find it useful to perform further diagnostic testing. There are additional laboratory tests that may be ordered for patients with a suspected diagnosis of PID (see Table 1).

TREATMENT

According to the CDC’s 2015 treatment guidelines for PID, a negative endocervical exam and negative microbial screening do not rule out an upper reproductive tract infection. Therefore, all sexually active women who present with lower abdominal pain and/or pelvic pain and have evidence of cervical motion, uterine, or adnexal tenderness on bimanual exam should be treated immediately.5

Treatment guidelines are outlined in Table 2. The polymicrobial nature of PID requires gram-negative antibiotic coverage, such as doxycycline plus a second/third-generation cephalosporin.5 Clinicians should note that cefoxitin, a second-generation cephalosporin, is recommended as firstline therapy for inpatients, as it has better anaerobic coverage than ceftriaxone.19 A targeted change in antibiotic coverage—such as inclusion of a macrolide and/or metronidazole—might be necessary if a causative organism is identified by culture.7

Treatment is indicated for all patients with a presumptive diagnosis of PID regardless of symptoms or exam findings, as PID may be asymptomatic and long-term sequelae (eg, infertility, ectopic pregnancy) are often irreversible. At-risk patients include sexually active adolescents, women with multiple sexual partners, women with a history of STI, those whose sexual partner has an STI, and women living in communities with a high prevalence of disease.20,21

Women being treated for PID should be advised to abstain from sexual intercourse until symptoms have resolved, treatment is completed, and any sexual partners have been treated as well. It is essential to emphasize to patients (and their partners) the importance of compliance to treatment regimens and the risk for PID co-infection and reinfection, as recurrence leads to an increase in long-term complications.5

Treatment of sexual partners. The CDC instructs that a woman’s most recent partner should be treated if she had sexual intercourse within 60 days of onset of symptoms or diagnosis. Furthermore, men who have had sexual contact with a woman who has PID in the 60 days prior to onset of her symptoms should be evaluated, tested, and treated for chlamydia and gonorrhea, regardless of the etiology of PID or the pathogens isolated from the woman.5

Admission criteria. Hospitalization should be based on provider judgment despite patient age. The suggested admission criteria include surgical emergency (eg, appendicitis), tubo-ovarian abscess, pregnancy, severe illness, nausea and vomiting, high fever, inability to follow or tolerate an outpatient oral regimen, and lack of clinical response to oral antimicrobial therapy.5

Follow-up care. Clinical improvement (ie, reduction in abdominal, uterine, adnexal, and cervical motion tenderness) should occur within 72 hours of antimicrobial therapy initiation. If it does not, hospital admission or adjustment in antimicrobial regimen should be considered, as well as additional diagnostic testing (eg, laparoscopy). In addition, all women with chlamydial- or gonococcal-related PID should return in three months for surveillance testing.22

COMPLICATIONS

Long-term complications—including infertility, chronic pelvic pain, and ectopic pregnancy—may occur, even when there has been a clinical response to adequate treatment. Data from the PID Evaluation and Clinical Health (PEACH) study were analyzed to assess long-term sequelae at seven years postdiagnosis and treatment. The researchers found that about 21% of women experienced recurrent PID, 19% developed infertility, and 42% reported chronic pelvic pain.3 Other research has also shown that repeat episodes of PID and delayed treatment increase the risk for long-term complications.23,24

SCREENING AND PREVENTION

Ten percent of women with an untreated STI will go on to develop PID.4 It is imperative to educate patients on the dangers and consequences of STIs when they become sexually active. Adolescents benefit the most from preventive education; this group is twice as likely as any other age group to be diagnosed with PID due to their inclination toward risky sexual behavior. Additionally, younger women tend to have a more friable cervix, increasing their risk for infection.25,26 Providers should promote safe sexual practices, such as condom use and less frequent partner exchange, in order to reduce STI exposure.

In 2015, the rate of reported cases of C trachomatis was 645.5 per 100,000 females, and of N gonorrheae, 107.2 per 100,000 females.23 The United States Preventive Services Task Force and the CDC recommend annual screening for chlamydia and gonorrhea in all sexually active women younger than 25, as well as sexually active women ages 25 and older who are considered at increased risk.5

CONCLUSION

PID is often difficult to diagnose, since patients may be asymptomatic or present with vague symptoms. Clinicians should maintain a high level of suspicion for PID in adolescent females due to the high incidence of STI exposure in this population. The best way to prevent long-term complications of PID is to prevent the first episode of PID and/or first exposure to STIs. Therefore, clinicians should be proactive in offering STI screenings to all sexually active patients younger than 25 who request care, regardless of their chief complaint, and educating patients on the potential long-term effects of PID and STIs.

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Diagnostic tests

- Complications of PID

- CDC treatment regimens

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is an ascending polymicrobial infection of the female upper reproductive tract that primarily affects sexually active women ages 15 to 29. Around 5% of sexually active women in the United States were treated for PID from 2011-2013.1 The rates and severity of PID have declined in North America and Western Europe due to overall decrease in sexually transmitted infection (STI) rates, improved screening initiatives for Chlamydia trachomatis, better treatment compliance secondary to increased access to antibiotics, and diagnostic tests with higher sensitivity.2 Despite this rate reduction, PID remains a major public health concern given the significant long-term complications, which include infertility, ectopic pregnancy, and chronic pelvic pain.3

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

PID is caused by sexually transmitted bacteria or enteric organisms that have spread to internal reproductive organs. Historically, the two most common pathogens identified in cases of PID have been Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae; however, the decline in rates of gonorrhea has led to a diminished role for N gonorrhoeae (though it continues to be associated with more severe cases).4,5

More recent studies have suggested a shift in the causative organisms; less than half of women diagnosed with acute PID test positive for either N gonorrhoeae or C trachomatis.6 Emerging infectious agents associated with PID include Mycoplasma genitalium, Gardnerella vaginalis, and bacterial vaginosis–associated bacteria.5,7,8-10

RISK FACTORS

Women ages 15 to 25 are at an increased risk for PID. The high prevalence in this age group may be attributable to high-risk behaviors, including a high number of sexual partners, high frequency of new sexual partners, and engagement in sexual intercourse without condoms.11

Taking an accurate sexual history is imperative. Clinicians should maintain a high level of suspicion for PID in women with a history of the disease, as 25% will experience recurrence.12

Clinicians should not be deterred from screening for STIs and cervical cancer in women who report having sex with other women. In addition, transgender patients should be assessed for STIs and HIV-related risks based on current anatomy sexual practices.13

PHYSICAL EXAM

While some cases of PID are asymptomatic, the typical presentation includes bilateral abdominal pain and/or pelvic pain, with onset during or shortly after menses. The pain often worsens with movement and coitus. Associated signs and symptoms include abnormal uterine bleeding or vaginal discharge; dysuria; fever and chills; frequent urination; lower back pain; and nausea and/or vomiting.14,15

All females suspected of having PID should undergo both a bimanual exam and a speculum exam. On bimanual examination, adnexal tenderness has the highest sensitivity (93% to 95.5%) for ruling out acute PID, whereas on speculum exam, purulent endocervical discharge has the highest specificity (93%).16,17 Bimanual exam findings suggestive of PID include cervical motion tenderness, uterine tenderness, and/or adnexal tenderness. Suggestive speculum exam findings include abnormal discoloration or texture of the cervix and/or endocervical mucopurulent discharge.5,16,17

One cardinal rule that should not be overlooked is that all females of reproductive age who present with abdominal pain and/or pelvic pain should take a pregnancy test to rule out ectopic pregnancy and any other pregnancy-related complications.

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of PID relies on clinical judgement and a high index of suspicion.5,18 The CDC’s diagnostic criteria for acute PID include

- Sexually active female AND

- Pelvic or lower abdominal pain AND

- Cervical motion tenderness OR uterine tenderness OR adnexal tenderness.5

Additional findings that support the diagnosis include

- Abnormal cervical mucopurulent discharge or cervical friability

- Abundant white blood cells (WBCs) on saline microscopy of vaginal fluid

- Elevated C-reactive protein

- Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- Laboratory documentation of infection with C trachomatis or N gonorrhea

- Oral temperature > 101°F.5,18

The CDC notes that the first two findings (mucopurulent discharge and evidence of WBCs on microscopy) occur in most women with PID; in their absence, the diagnosis is unlikely and other sources of pain should be considered.5 The differential for PID includes acute appendicitis; adhesions; carcinoid tumor; cholecystitis; ectopic pregnancy; endometriosis; inflammatory bowel disease; and ovarian cyst.19

Given the variability in presentation, clinicians may find it useful to perform further diagnostic testing. There are additional laboratory tests that may be ordered for patients with a suspected diagnosis of PID (see Table 1).

TREATMENT

According to the CDC’s 2015 treatment guidelines for PID, a negative endocervical exam and negative microbial screening do not rule out an upper reproductive tract infection. Therefore, all sexually active women who present with lower abdominal pain and/or pelvic pain and have evidence of cervical motion, uterine, or adnexal tenderness on bimanual exam should be treated immediately.5

Treatment guidelines are outlined in Table 2. The polymicrobial nature of PID requires gram-negative antibiotic coverage, such as doxycycline plus a second/third-generation cephalosporin.5 Clinicians should note that cefoxitin, a second-generation cephalosporin, is recommended as firstline therapy for inpatients, as it has better anaerobic coverage than ceftriaxone.19 A targeted change in antibiotic coverage—such as inclusion of a macrolide and/or metronidazole—might be necessary if a causative organism is identified by culture.7

Treatment is indicated for all patients with a presumptive diagnosis of PID regardless of symptoms or exam findings, as PID may be asymptomatic and long-term sequelae (eg, infertility, ectopic pregnancy) are often irreversible. At-risk patients include sexually active adolescents, women with multiple sexual partners, women with a history of STI, those whose sexual partner has an STI, and women living in communities with a high prevalence of disease.20,21

Women being treated for PID should be advised to abstain from sexual intercourse until symptoms have resolved, treatment is completed, and any sexual partners have been treated as well. It is essential to emphasize to patients (and their partners) the importance of compliance to treatment regimens and the risk for PID co-infection and reinfection, as recurrence leads to an increase in long-term complications.5

Treatment of sexual partners. The CDC instructs that a woman’s most recent partner should be treated if she had sexual intercourse within 60 days of onset of symptoms or diagnosis. Furthermore, men who have had sexual contact with a woman who has PID in the 60 days prior to onset of her symptoms should be evaluated, tested, and treated for chlamydia and gonorrhea, regardless of the etiology of PID or the pathogens isolated from the woman.5

Admission criteria. Hospitalization should be based on provider judgment despite patient age. The suggested admission criteria include surgical emergency (eg, appendicitis), tubo-ovarian abscess, pregnancy, severe illness, nausea and vomiting, high fever, inability to follow or tolerate an outpatient oral regimen, and lack of clinical response to oral antimicrobial therapy.5

Follow-up care. Clinical improvement (ie, reduction in abdominal, uterine, adnexal, and cervical motion tenderness) should occur within 72 hours of antimicrobial therapy initiation. If it does not, hospital admission or adjustment in antimicrobial regimen should be considered, as well as additional diagnostic testing (eg, laparoscopy). In addition, all women with chlamydial- or gonococcal-related PID should return in three months for surveillance testing.22

COMPLICATIONS

Long-term complications—including infertility, chronic pelvic pain, and ectopic pregnancy—may occur, even when there has been a clinical response to adequate treatment. Data from the PID Evaluation and Clinical Health (PEACH) study were analyzed to assess long-term sequelae at seven years postdiagnosis and treatment. The researchers found that about 21% of women experienced recurrent PID, 19% developed infertility, and 42% reported chronic pelvic pain.3 Other research has also shown that repeat episodes of PID and delayed treatment increase the risk for long-term complications.23,24

SCREENING AND PREVENTION

Ten percent of women with an untreated STI will go on to develop PID.4 It is imperative to educate patients on the dangers and consequences of STIs when they become sexually active. Adolescents benefit the most from preventive education; this group is twice as likely as any other age group to be diagnosed with PID due to their inclination toward risky sexual behavior. Additionally, younger women tend to have a more friable cervix, increasing their risk for infection.25,26 Providers should promote safe sexual practices, such as condom use and less frequent partner exchange, in order to reduce STI exposure.

In 2015, the rate of reported cases of C trachomatis was 645.5 per 100,000 females, and of N gonorrheae, 107.2 per 100,000 females.23 The United States Preventive Services Task Force and the CDC recommend annual screening for chlamydia and gonorrhea in all sexually active women younger than 25, as well as sexually active women ages 25 and older who are considered at increased risk.5

CONCLUSION

PID is often difficult to diagnose, since patients may be asymptomatic or present with vague symptoms. Clinicians should maintain a high level of suspicion for PID in adolescent females due to the high incidence of STI exposure in this population. The best way to prevent long-term complications of PID is to prevent the first episode of PID and/or first exposure to STIs. Therefore, clinicians should be proactive in offering STI screenings to all sexually active patients younger than 25 who request care, regardless of their chief complaint, and educating patients on the potential long-term effects of PID and STIs.

1. Leichliter JS, Chandra A, Aral SO. Correlates of self-reported pelvic inflammatory disease treatment in sexually experienced reproductive-aged women in the United States, 1995 and 2006-2010. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(5):413-418.

2. Owusu-Edusei K Jr, Bohm MK, Chesson HW, Kent CK. Chlamydia screening and pelvic inflammatory disease: insights from exploratory time-series analyses. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(6):652-657.

3. Trent M, Bass D, Ness RB, Haggerty C. Recurrent PID, subsequent STI, and reproductive health outcomes: findings from the PID evaluation and clinical health (PEACH) study. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(9):879-881.

4. Mitchell C, Prabhu M. Pelvic inflammatory disease: current concepts in pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2013;27(4):793-809.

5. CDC. Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/pid.htm. Accessed July 13, 2017.

6. Burnett AM, Anderson CP, Zwank MD. Laboratory-confirmed gonorrhea and/or chlamydia rates in clinically diagnosed pelvic inflammatory disease and cervicitis. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30:1114–1117.

7. Bjartling C, Osser S, Persson K. The association between Mycoplasma genitalium and pelvic inflammatory disease after termination of pregnancy. BJOG. 2010;117(3):361-364.

8. Ness RB, Kip KE, Hillier SL, et al. A cluster analysis of bacterial vaginosis-associated microflora and pelvic inflammatory disease. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162(6):585-590.

9. Ness RB, Hillier SL, Kip KE, et al. Bacterial vaginosis and risk of pelvic inflammatory disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(4):761-769.

10. Cherpes TL, Wiesenfeld HC, Melan MA, et al. The associations between pelvic inflammatory disease, Trichomonas vaginalis infection, and positive herpes simplex virus type 2 serology. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(12):747-752.

11. Simms I, Stephenson JM, Mallinson H, et al. Risk factors associated with pelvic inflammatory disease. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82(6):452-457.

12. Schindlbeck C, Dziura D, Mylonas I. Diagnosis of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID): intra-operative findings and comparison of vaginal and intra-abdominal cultures. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;289(6):1263-1269.

13. CDC. 2015 sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/default.htm. Accessed September 6, 2017.

14. Korn AP, Hessol NA, Padian NS, et al. Risk factors for plasma cell endometritis among women with cervical Neisseria gonorrhoeae, cervical Chlamydia trachomatis, or bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178(5):987-990.

15. Wiesenfeld HC, Sweet RL, Ness RB, et al. Comparison of acute and subclinical pelvic inflammatory disease. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32(7):400-405.

16. Peipert JF, Ness RB, Blume J, et al. Clinical predictors of endometritis in women with symptoms and signs of pelvic inflammatory disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184(5):856-864.

17. Gaitán H, Angel E, Diaz R, et al. Accuracy of five different diagnostic techniques in mild-to-moderate pelvic inflammatory disease. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2002;10(4):171-180.

18. Tukeva TA, Aronen HJ, Karjalainen PT, et al. MR imaging in pelvic inflammatory disease: comparison with laparoscopy and US. Radiology. 1999;210(1):209-216.

19. Morino M, Pellegrino L, Castagna E, et al. Acute nonspecific abdominal pain. Ann Surg. 2006;244(6):881-888.

20. Woods JL, Scurlock AM, Hensel DJ. Pelvic inflammatory disease in the adolescent: understanding diagnosis and treatment as a health care provider. Pediatric Emergency Care. 2013;29(6):720-725.

21. LeFevre ML; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for chlamydia and gonorrhea: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(12):902-910.

22. Hosenfeld CB, Workowski KA, Berman S, et al. Repeat infection with Chlamydia and gonorrhea among females: a systematic review of the literature. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36(8):478-489.

23. CDC. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance. www.cdc.gov/std/stats15/STD-Surveillance-2015-print.pdf. Accessed July 13, 2017.

24. Hillis SD, Joesoef R, Marchbanks PA, et al. Delayed care of pelvic inflammatory disease as a risk factor for impaired fertility. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;168(5):1503-1509.

25. Goyal M, Hersh A, Luan X, et al. National trends in pelvic inflammatory disease among adolescents in the emergency department. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53(2):249-252.

26. Gray-Swain MR, Peipert JF. Pelvic inflammatory disease in adolescents. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2006;18(5):503-510.

27. Łój B, Brodowska A, Ciecwiez S, et al. The role of serological testing for Chlamydia trachomatis in differential diagnosis of pelvic pain. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2016;23(3):506-510.

28. Sam JW, Jacobs JE, Birnbaum BA. Spectrum of CT findings in acute pyogenic pelvic inflammatory disease. Radiographics. 2002;22(6):1327-1 334.

1. Leichliter JS, Chandra A, Aral SO. Correlates of self-reported pelvic inflammatory disease treatment in sexually experienced reproductive-aged women in the United States, 1995 and 2006-2010. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(5):413-418.

2. Owusu-Edusei K Jr, Bohm MK, Chesson HW, Kent CK. Chlamydia screening and pelvic inflammatory disease: insights from exploratory time-series analyses. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(6):652-657.

3. Trent M, Bass D, Ness RB, Haggerty C. Recurrent PID, subsequent STI, and reproductive health outcomes: findings from the PID evaluation and clinical health (PEACH) study. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(9):879-881.

4. Mitchell C, Prabhu M. Pelvic inflammatory disease: current concepts in pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2013;27(4):793-809.

5. CDC. Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/pid.htm. Accessed July 13, 2017.

6. Burnett AM, Anderson CP, Zwank MD. Laboratory-confirmed gonorrhea and/or chlamydia rates in clinically diagnosed pelvic inflammatory disease and cervicitis. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30:1114–1117.

7. Bjartling C, Osser S, Persson K. The association between Mycoplasma genitalium and pelvic inflammatory disease after termination of pregnancy. BJOG. 2010;117(3):361-364.

8. Ness RB, Kip KE, Hillier SL, et al. A cluster analysis of bacterial vaginosis-associated microflora and pelvic inflammatory disease. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162(6):585-590.

9. Ness RB, Hillier SL, Kip KE, et al. Bacterial vaginosis and risk of pelvic inflammatory disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(4):761-769.

10. Cherpes TL, Wiesenfeld HC, Melan MA, et al. The associations between pelvic inflammatory disease, Trichomonas vaginalis infection, and positive herpes simplex virus type 2 serology. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(12):747-752.

11. Simms I, Stephenson JM, Mallinson H, et al. Risk factors associated with pelvic inflammatory disease. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82(6):452-457.

12. Schindlbeck C, Dziura D, Mylonas I. Diagnosis of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID): intra-operative findings and comparison of vaginal and intra-abdominal cultures. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;289(6):1263-1269.

13. CDC. 2015 sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/default.htm. Accessed September 6, 2017.

14. Korn AP, Hessol NA, Padian NS, et al. Risk factors for plasma cell endometritis among women with cervical Neisseria gonorrhoeae, cervical Chlamydia trachomatis, or bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178(5):987-990.

15. Wiesenfeld HC, Sweet RL, Ness RB, et al. Comparison of acute and subclinical pelvic inflammatory disease. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32(7):400-405.

16. Peipert JF, Ness RB, Blume J, et al. Clinical predictors of endometritis in women with symptoms and signs of pelvic inflammatory disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184(5):856-864.

17. Gaitán H, Angel E, Diaz R, et al. Accuracy of five different diagnostic techniques in mild-to-moderate pelvic inflammatory disease. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2002;10(4):171-180.

18. Tukeva TA, Aronen HJ, Karjalainen PT, et al. MR imaging in pelvic inflammatory disease: comparison with laparoscopy and US. Radiology. 1999;210(1):209-216.

19. Morino M, Pellegrino L, Castagna E, et al. Acute nonspecific abdominal pain. Ann Surg. 2006;244(6):881-888.

20. Woods JL, Scurlock AM, Hensel DJ. Pelvic inflammatory disease in the adolescent: understanding diagnosis and treatment as a health care provider. Pediatric Emergency Care. 2013;29(6):720-725.

21. LeFevre ML; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for chlamydia and gonorrhea: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(12):902-910.

22. Hosenfeld CB, Workowski KA, Berman S, et al. Repeat infection with Chlamydia and gonorrhea among females: a systematic review of the literature. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36(8):478-489.

23. CDC. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance. www.cdc.gov/std/stats15/STD-Surveillance-2015-print.pdf. Accessed July 13, 2017.

24. Hillis SD, Joesoef R, Marchbanks PA, et al. Delayed care of pelvic inflammatory disease as a risk factor for impaired fertility. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;168(5):1503-1509.

25. Goyal M, Hersh A, Luan X, et al. National trends in pelvic inflammatory disease among adolescents in the emergency department. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53(2):249-252.

26. Gray-Swain MR, Peipert JF. Pelvic inflammatory disease in adolescents. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2006;18(5):503-510.

27. Łój B, Brodowska A, Ciecwiez S, et al. The role of serological testing for Chlamydia trachomatis in differential diagnosis of pelvic pain. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2016;23(3):506-510.

28. Sam JW, Jacobs JE, Birnbaum BA. Spectrum of CT findings in acute pyogenic pelvic inflammatory disease. Radiographics. 2002;22(6):1327-1 334.