User login

The Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (GRECC) Memory Disorders Clinic at the VA Puget Sound Health Care System (VAPSHCS) in Seattle, Washington, receives referrals from primary and specialty care. About a decade ago, this clinic began to see an influx of Vietnam-era veterans who presented with a variety of symptoms: not remembering where they were going when driving, forgetting why they went into another room, not remembering what their spouse told them, and feeling “out of it.” These symptoms were not associated with the loss of independence, but they were cause for concern. Family members and care providers typically corroborated the symptom description and perception of decline. Yet during workups, these veterans showed no primary medical causes for cognitive impairments and on neuropsychological evaluation demonstrated essentially normal cognition.

Memory Disorders Clinic staff largely were at a loss to know how to care for these patients. The simple reassurance, “You do not have dementia now,” seemed unsatisfactory given the patients’ ongoing concerns and the established risk factors for neurodegenerative disease.1,2 One theme emerged when talking with these veterans and their families: They all had a diagnosis of or history of treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

To help these veterans, the VAPSHCS GRECC sought to address their key areas of concern related to memory. With input from veterans and their families, a quality improvement project was developed with the following goals: (1) to educate veterans and their families about PTSD and cognitive changes; (2) to build and field test a psychoeducational class to teach memory skills in this population; and (3) to inform VA staff about PTSD and cognitive change. In this article, the authors focus on how the first 2 goals were addressed and present preliminary results related to quality improvement.

Memory Skills Classes

Several strategies might promote memory skills, including printed materials for self-directed learning, individual sessions, interactive technologies, or groups. Given the patients’ reports about concentration problems, asking them to work through structured materials independently seemed unproductive. Individual clinical evaluations and cognitive interventions likely would not meet the demand or be cost-effective. Groups have long been used to treat PTSD, and Norrie and colleagues reported that at-risk adults benefited from a group psychoeducation program targeting healthy brain aging.3 At the same time, the Memory Disorders Clinic sought to distinguish itself from PTSD groups, because these groups tend to focus on treating active PTSD.

A better fit for this offering was the description of the sessions as classes. Although the focus was on promoting memory skills among those capable of learning them, the authors were mindful that some veterans might truly have prodromal dementia or acute PTSD symptoms that would require clinical management. The classes were not intended to address all these issues, and there was a plan to refer participants either before or during the class if warranted.

There was no formal evaluation of memory prior to starting the class. These classes were not developed as a research intervention and were exempt from institutional review board (IRB) approval requirements, according to prescreening by the VAPSHCS IRB and a memo from the GRECC director.

Core Components of Memory Skills

It may not be evident at first glance that PTSD or a history of PTSD influences memory. The symptom criteria for PTSD (involving reexperiencing, hyperarousal, and avoidance) might be described as “too much remembering” rather than forgetting. Yet problems with attention and concentration often occur in the setting of intrusive memories and alterations in reactivity. Research has found that older adults with PTSD have deficits of memory, especially new learning.

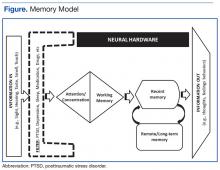

To appreciate these effects, it was important for participants in the memory skills classes to have some understanding of how memory works. The authors developed the Memory Model (Figure) as a visual aid and reference point to discuss the stages of new learning and how different aspects of brain activity are required for new learning and for memory to occur. This straightforward model is based on cognitive science and presented in layman’s terms. An important part of this model is the “filter” stage, which controls the information and stimuli that are available to the brain. Posttraumatic stress disorder involves involuntary emotional responses and efforts to avoid them and selects and colors the information that is processed in some situations (eg, avoidance of situations associated with trauma or dissociation of extreme memories). At other times, such as when a powerful stimulus is presented (eg, a helicopter flying close overhead), the filter may try to block out all inputs in order to preserve safety. The Memory Model also served as a visual aid during class discussions of normal cognitive aging.

Class sessions incorporated specific, measurable, attainable, realistic, and timely (SMART) goals, regular exercises based on mindfulness-based stress reduction approaches, and principles of behavioral activation.5 The SMART goals structure the sessions and permit customization of learning for participants. Class leaders record a goal for each participant and use these throughout the sessions to build rapport, develop communication, and teach memory skills.

Mindfulness-based stress reduction is an evidence-based treatment used in PTSD.6 It provides a counterpoint to the more didactic memory skills and is a method that even those with objective memory impairments can practice and apply successfully. Being in the current moment and emotional regulation are important skills to teach veterans as they learn to exert

Organization

Class sessions occurred weekly for 1 hour for a total of 8 sessions. The weekly class topics included introduction to memory; mood disorders, cognition, and cognitive disorders; barriers to effective memory: assessing readiness for change; developing a routine and becoming organized; attention and concentration; memory improvement (strategies internal and external aids); and reassessing goals.

Over the 3 years of classes reported in this article, the class sizes varied from 4 to 12 participants based on veteran interest, retention, and room size. The classes were structured so that important content areas were covered but with enough elasticity so leaders and veterans would develop a rapport and explore in greater depth the topics that resonated most for the attendees. Group participation was strongly encouraged. Veterans were expressly informed that the class was not for treatment of PTSD and that evidence-based therapies were encouraged to address PTSD especially if their symptoms flared up when compared with previous levels. The attendees also understood that they did not receive formal cognitive or memory testing but were encouraged to pursue testing if they showed significant deficits.

Preliminary Findings

From spring 2012 until spring 2015, 69 veterans agreed to participate and attended at least 1 memory skills class. Eighty-seven percent of participants (n = 60) attended 4 or more classes. The mean age (SD) was 67.3 years (4.2). All the participants were men, and the race/ethnic distribution was similar to that of the aging veteran population and very close to racial demographics for Washington state: 80% white, 14% African American, 2% Asian/Pacific Islander, 2% Native American, and 2% unknown.

Attendees were asked, but not required, to complete questionnaires before the classes began and again at completion. These questionnaires included self-assessments of cognitive strategies and compensatory methods used; an assessment of concern regarding cognition, life satisfaction, and community integration; the PTSD CheckList-Civilian Version (PCL-C); and the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS).7,8 The questionnaire also included open response questions to providefeedback on what attendees liked about the classes and recommendations for improvements. The majority of comments for improvement focused on attendees’ desire for longer sessions and repeat offerings. Five veterans did not complete the full set of questionnaires at the beginning of the classes, and 7 did not complete the questionnaires at completion (the 2 subsets did not perfectly overlap).

At the start of the class, on average, veteran participants were experiencing mild depression and moderate symptoms of PTSD as measured by the GDS (n = 54) and the PCL-C (n = 56), respectively. Preliminary comparisons of ratings pre- and post-classes, using simple paired t tests, indicated a reduction in symptoms of depression on the GDS, improved sense of mastery over their memory symptoms, as well as improved quality of life ratings (all P < .01, no corrections). There was no evidence for a significant reduction in PTSD symptoms or report of elimination of cognitive difficulties. With the small sample and modest effects, the clinical significance of these scores cannot be determined. The authors are planning more detailed analyses on a larger set of participants, including measures of health care utilization before and after the class.

Future Directions

1. Chopra MP, Zhang H, Pless Kaiser A, et al. PTSD is a chronic, fluctuating disorder affecting the mental quality of life in older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22(1):86-97.

2. Donovan NJ, Amariglio RE, Zoller AS, et al. Subjective cognitive concerns and neuropsychiatric predictors of progression to the early clinical stages of Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22(12):1642-1651.

3. Norrie LM, Diamond K, Hickie IB, Rogers NL, Fearns S, Naismith SL. Can older “at risk” adults benefit from psychoeducation targeting healthy brain aging? Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23(3):413-424.

4. Hopko DR, Robertson SMC, Lejuez CW. Behavioral activation for anxiety disorders. Behav Anal Today. 2006;7(2):212-232.

5. Schuitevoerder S, Rosen JW, Twamley EW, et al. A meta-analysis of cognitive functioning in older adults with PTSD. J Anxiety Disord. 2013;27(6):550-558.

6. Polusny MA, Erbes CR, Thuras P, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for posttraumatic stress disorder among veterans: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314(5):456-465.

7. Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1982-1983;17(1):37-49.

8. Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center. PTSD CheckList-Civilian Version (PCL-C). http://www.mirecc.va.gov/docs/visn6/3_PTSD _CheckList_and_Scoring.pdf Published December 2013. Accessed November 3, 2016.

9. Scott JC, Matt GE, Wrocklage KM, et al. A quantitative meta-analysis of neurocognitive functioning in posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychol Bull. 2015;141(1):105-140.

10. Wrocklage KM, Schweinsburg BC, Krystal JH, et al. Neuropsychological functioning in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: associations with performance validity, comorbidities, and functional outcomes. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2016;22(4):399-411.

11. Cook JM, O’Donnell C. Assessment and psychological treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in older adults. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2005;18(2):61-71.

12. Mota N, Tsai J, Kirwin PD, et al. Late-life exacerbation of PTSD symptoms in US veterans: results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(3):348-354.

13. Yaffe K, Vittinghoff E, Lindquist K, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and risk of dementia among US veterans. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(6):608-613.

The Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (GRECC) Memory Disorders Clinic at the VA Puget Sound Health Care System (VAPSHCS) in Seattle, Washington, receives referrals from primary and specialty care. About a decade ago, this clinic began to see an influx of Vietnam-era veterans who presented with a variety of symptoms: not remembering where they were going when driving, forgetting why they went into another room, not remembering what their spouse told them, and feeling “out of it.” These symptoms were not associated with the loss of independence, but they were cause for concern. Family members and care providers typically corroborated the symptom description and perception of decline. Yet during workups, these veterans showed no primary medical causes for cognitive impairments and on neuropsychological evaluation demonstrated essentially normal cognition.

Memory Disorders Clinic staff largely were at a loss to know how to care for these patients. The simple reassurance, “You do not have dementia now,” seemed unsatisfactory given the patients’ ongoing concerns and the established risk factors for neurodegenerative disease.1,2 One theme emerged when talking with these veterans and their families: They all had a diagnosis of or history of treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

To help these veterans, the VAPSHCS GRECC sought to address their key areas of concern related to memory. With input from veterans and their families, a quality improvement project was developed with the following goals: (1) to educate veterans and their families about PTSD and cognitive changes; (2) to build and field test a psychoeducational class to teach memory skills in this population; and (3) to inform VA staff about PTSD and cognitive change. In this article, the authors focus on how the first 2 goals were addressed and present preliminary results related to quality improvement.

Memory Skills Classes

Several strategies might promote memory skills, including printed materials for self-directed learning, individual sessions, interactive technologies, or groups. Given the patients’ reports about concentration problems, asking them to work through structured materials independently seemed unproductive. Individual clinical evaluations and cognitive interventions likely would not meet the demand or be cost-effective. Groups have long been used to treat PTSD, and Norrie and colleagues reported that at-risk adults benefited from a group psychoeducation program targeting healthy brain aging.3 At the same time, the Memory Disorders Clinic sought to distinguish itself from PTSD groups, because these groups tend to focus on treating active PTSD.

A better fit for this offering was the description of the sessions as classes. Although the focus was on promoting memory skills among those capable of learning them, the authors were mindful that some veterans might truly have prodromal dementia or acute PTSD symptoms that would require clinical management. The classes were not intended to address all these issues, and there was a plan to refer participants either before or during the class if warranted.

There was no formal evaluation of memory prior to starting the class. These classes were not developed as a research intervention and were exempt from institutional review board (IRB) approval requirements, according to prescreening by the VAPSHCS IRB and a memo from the GRECC director.

Core Components of Memory Skills

It may not be evident at first glance that PTSD or a history of PTSD influences memory. The symptom criteria for PTSD (involving reexperiencing, hyperarousal, and avoidance) might be described as “too much remembering” rather than forgetting. Yet problems with attention and concentration often occur in the setting of intrusive memories and alterations in reactivity. Research has found that older adults with PTSD have deficits of memory, especially new learning.

To appreciate these effects, it was important for participants in the memory skills classes to have some understanding of how memory works. The authors developed the Memory Model (Figure) as a visual aid and reference point to discuss the stages of new learning and how different aspects of brain activity are required for new learning and for memory to occur. This straightforward model is based on cognitive science and presented in layman’s terms. An important part of this model is the “filter” stage, which controls the information and stimuli that are available to the brain. Posttraumatic stress disorder involves involuntary emotional responses and efforts to avoid them and selects and colors the information that is processed in some situations (eg, avoidance of situations associated with trauma or dissociation of extreme memories). At other times, such as when a powerful stimulus is presented (eg, a helicopter flying close overhead), the filter may try to block out all inputs in order to preserve safety. The Memory Model also served as a visual aid during class discussions of normal cognitive aging.

Class sessions incorporated specific, measurable, attainable, realistic, and timely (SMART) goals, regular exercises based on mindfulness-based stress reduction approaches, and principles of behavioral activation.5 The SMART goals structure the sessions and permit customization of learning for participants. Class leaders record a goal for each participant and use these throughout the sessions to build rapport, develop communication, and teach memory skills.

Mindfulness-based stress reduction is an evidence-based treatment used in PTSD.6 It provides a counterpoint to the more didactic memory skills and is a method that even those with objective memory impairments can practice and apply successfully. Being in the current moment and emotional regulation are important skills to teach veterans as they learn to exert

Organization

Class sessions occurred weekly for 1 hour for a total of 8 sessions. The weekly class topics included introduction to memory; mood disorders, cognition, and cognitive disorders; barriers to effective memory: assessing readiness for change; developing a routine and becoming organized; attention and concentration; memory improvement (strategies internal and external aids); and reassessing goals.

Over the 3 years of classes reported in this article, the class sizes varied from 4 to 12 participants based on veteran interest, retention, and room size. The classes were structured so that important content areas were covered but with enough elasticity so leaders and veterans would develop a rapport and explore in greater depth the topics that resonated most for the attendees. Group participation was strongly encouraged. Veterans were expressly informed that the class was not for treatment of PTSD and that evidence-based therapies were encouraged to address PTSD especially if their symptoms flared up when compared with previous levels. The attendees also understood that they did not receive formal cognitive or memory testing but were encouraged to pursue testing if they showed significant deficits.

Preliminary Findings

From spring 2012 until spring 2015, 69 veterans agreed to participate and attended at least 1 memory skills class. Eighty-seven percent of participants (n = 60) attended 4 or more classes. The mean age (SD) was 67.3 years (4.2). All the participants were men, and the race/ethnic distribution was similar to that of the aging veteran population and very close to racial demographics for Washington state: 80% white, 14% African American, 2% Asian/Pacific Islander, 2% Native American, and 2% unknown.

Attendees were asked, but not required, to complete questionnaires before the classes began and again at completion. These questionnaires included self-assessments of cognitive strategies and compensatory methods used; an assessment of concern regarding cognition, life satisfaction, and community integration; the PTSD CheckList-Civilian Version (PCL-C); and the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS).7,8 The questionnaire also included open response questions to providefeedback on what attendees liked about the classes and recommendations for improvements. The majority of comments for improvement focused on attendees’ desire for longer sessions and repeat offerings. Five veterans did not complete the full set of questionnaires at the beginning of the classes, and 7 did not complete the questionnaires at completion (the 2 subsets did not perfectly overlap).

At the start of the class, on average, veteran participants were experiencing mild depression and moderate symptoms of PTSD as measured by the GDS (n = 54) and the PCL-C (n = 56), respectively. Preliminary comparisons of ratings pre- and post-classes, using simple paired t tests, indicated a reduction in symptoms of depression on the GDS, improved sense of mastery over their memory symptoms, as well as improved quality of life ratings (all P < .01, no corrections). There was no evidence for a significant reduction in PTSD symptoms or report of elimination of cognitive difficulties. With the small sample and modest effects, the clinical significance of these scores cannot be determined. The authors are planning more detailed analyses on a larger set of participants, including measures of health care utilization before and after the class.

Future Directions

The Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (GRECC) Memory Disorders Clinic at the VA Puget Sound Health Care System (VAPSHCS) in Seattle, Washington, receives referrals from primary and specialty care. About a decade ago, this clinic began to see an influx of Vietnam-era veterans who presented with a variety of symptoms: not remembering where they were going when driving, forgetting why they went into another room, not remembering what their spouse told them, and feeling “out of it.” These symptoms were not associated with the loss of independence, but they were cause for concern. Family members and care providers typically corroborated the symptom description and perception of decline. Yet during workups, these veterans showed no primary medical causes for cognitive impairments and on neuropsychological evaluation demonstrated essentially normal cognition.

Memory Disorders Clinic staff largely were at a loss to know how to care for these patients. The simple reassurance, “You do not have dementia now,” seemed unsatisfactory given the patients’ ongoing concerns and the established risk factors for neurodegenerative disease.1,2 One theme emerged when talking with these veterans and their families: They all had a diagnosis of or history of treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

To help these veterans, the VAPSHCS GRECC sought to address their key areas of concern related to memory. With input from veterans and their families, a quality improvement project was developed with the following goals: (1) to educate veterans and their families about PTSD and cognitive changes; (2) to build and field test a psychoeducational class to teach memory skills in this population; and (3) to inform VA staff about PTSD and cognitive change. In this article, the authors focus on how the first 2 goals were addressed and present preliminary results related to quality improvement.

Memory Skills Classes

Several strategies might promote memory skills, including printed materials for self-directed learning, individual sessions, interactive technologies, or groups. Given the patients’ reports about concentration problems, asking them to work through structured materials independently seemed unproductive. Individual clinical evaluations and cognitive interventions likely would not meet the demand or be cost-effective. Groups have long been used to treat PTSD, and Norrie and colleagues reported that at-risk adults benefited from a group psychoeducation program targeting healthy brain aging.3 At the same time, the Memory Disorders Clinic sought to distinguish itself from PTSD groups, because these groups tend to focus on treating active PTSD.

A better fit for this offering was the description of the sessions as classes. Although the focus was on promoting memory skills among those capable of learning them, the authors were mindful that some veterans might truly have prodromal dementia or acute PTSD symptoms that would require clinical management. The classes were not intended to address all these issues, and there was a plan to refer participants either before or during the class if warranted.

There was no formal evaluation of memory prior to starting the class. These classes were not developed as a research intervention and were exempt from institutional review board (IRB) approval requirements, according to prescreening by the VAPSHCS IRB and a memo from the GRECC director.

Core Components of Memory Skills

It may not be evident at first glance that PTSD or a history of PTSD influences memory. The symptom criteria for PTSD (involving reexperiencing, hyperarousal, and avoidance) might be described as “too much remembering” rather than forgetting. Yet problems with attention and concentration often occur in the setting of intrusive memories and alterations in reactivity. Research has found that older adults with PTSD have deficits of memory, especially new learning.

To appreciate these effects, it was important for participants in the memory skills classes to have some understanding of how memory works. The authors developed the Memory Model (Figure) as a visual aid and reference point to discuss the stages of new learning and how different aspects of brain activity are required for new learning and for memory to occur. This straightforward model is based on cognitive science and presented in layman’s terms. An important part of this model is the “filter” stage, which controls the information and stimuli that are available to the brain. Posttraumatic stress disorder involves involuntary emotional responses and efforts to avoid them and selects and colors the information that is processed in some situations (eg, avoidance of situations associated with trauma or dissociation of extreme memories). At other times, such as when a powerful stimulus is presented (eg, a helicopter flying close overhead), the filter may try to block out all inputs in order to preserve safety. The Memory Model also served as a visual aid during class discussions of normal cognitive aging.

Class sessions incorporated specific, measurable, attainable, realistic, and timely (SMART) goals, regular exercises based on mindfulness-based stress reduction approaches, and principles of behavioral activation.5 The SMART goals structure the sessions and permit customization of learning for participants. Class leaders record a goal for each participant and use these throughout the sessions to build rapport, develop communication, and teach memory skills.

Mindfulness-based stress reduction is an evidence-based treatment used in PTSD.6 It provides a counterpoint to the more didactic memory skills and is a method that even those with objective memory impairments can practice and apply successfully. Being in the current moment and emotional regulation are important skills to teach veterans as they learn to exert

Organization

Class sessions occurred weekly for 1 hour for a total of 8 sessions. The weekly class topics included introduction to memory; mood disorders, cognition, and cognitive disorders; barriers to effective memory: assessing readiness for change; developing a routine and becoming organized; attention and concentration; memory improvement (strategies internal and external aids); and reassessing goals.

Over the 3 years of classes reported in this article, the class sizes varied from 4 to 12 participants based on veteran interest, retention, and room size. The classes were structured so that important content areas were covered but with enough elasticity so leaders and veterans would develop a rapport and explore in greater depth the topics that resonated most for the attendees. Group participation was strongly encouraged. Veterans were expressly informed that the class was not for treatment of PTSD and that evidence-based therapies were encouraged to address PTSD especially if their symptoms flared up when compared with previous levels. The attendees also understood that they did not receive formal cognitive or memory testing but were encouraged to pursue testing if they showed significant deficits.

Preliminary Findings

From spring 2012 until spring 2015, 69 veterans agreed to participate and attended at least 1 memory skills class. Eighty-seven percent of participants (n = 60) attended 4 or more classes. The mean age (SD) was 67.3 years (4.2). All the participants were men, and the race/ethnic distribution was similar to that of the aging veteran population and very close to racial demographics for Washington state: 80% white, 14% African American, 2% Asian/Pacific Islander, 2% Native American, and 2% unknown.

Attendees were asked, but not required, to complete questionnaires before the classes began and again at completion. These questionnaires included self-assessments of cognitive strategies and compensatory methods used; an assessment of concern regarding cognition, life satisfaction, and community integration; the PTSD CheckList-Civilian Version (PCL-C); and the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS).7,8 The questionnaire also included open response questions to providefeedback on what attendees liked about the classes and recommendations for improvements. The majority of comments for improvement focused on attendees’ desire for longer sessions and repeat offerings. Five veterans did not complete the full set of questionnaires at the beginning of the classes, and 7 did not complete the questionnaires at completion (the 2 subsets did not perfectly overlap).

At the start of the class, on average, veteran participants were experiencing mild depression and moderate symptoms of PTSD as measured by the GDS (n = 54) and the PCL-C (n = 56), respectively. Preliminary comparisons of ratings pre- and post-classes, using simple paired t tests, indicated a reduction in symptoms of depression on the GDS, improved sense of mastery over their memory symptoms, as well as improved quality of life ratings (all P < .01, no corrections). There was no evidence for a significant reduction in PTSD symptoms or report of elimination of cognitive difficulties. With the small sample and modest effects, the clinical significance of these scores cannot be determined. The authors are planning more detailed analyses on a larger set of participants, including measures of health care utilization before and after the class.

Future Directions

1. Chopra MP, Zhang H, Pless Kaiser A, et al. PTSD is a chronic, fluctuating disorder affecting the mental quality of life in older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22(1):86-97.

2. Donovan NJ, Amariglio RE, Zoller AS, et al. Subjective cognitive concerns and neuropsychiatric predictors of progression to the early clinical stages of Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22(12):1642-1651.

3. Norrie LM, Diamond K, Hickie IB, Rogers NL, Fearns S, Naismith SL. Can older “at risk” adults benefit from psychoeducation targeting healthy brain aging? Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23(3):413-424.

4. Hopko DR, Robertson SMC, Lejuez CW. Behavioral activation for anxiety disorders. Behav Anal Today. 2006;7(2):212-232.

5. Schuitevoerder S, Rosen JW, Twamley EW, et al. A meta-analysis of cognitive functioning in older adults with PTSD. J Anxiety Disord. 2013;27(6):550-558.

6. Polusny MA, Erbes CR, Thuras P, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for posttraumatic stress disorder among veterans: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314(5):456-465.

7. Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1982-1983;17(1):37-49.

8. Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center. PTSD CheckList-Civilian Version (PCL-C). http://www.mirecc.va.gov/docs/visn6/3_PTSD _CheckList_and_Scoring.pdf Published December 2013. Accessed November 3, 2016.

9. Scott JC, Matt GE, Wrocklage KM, et al. A quantitative meta-analysis of neurocognitive functioning in posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychol Bull. 2015;141(1):105-140.

10. Wrocklage KM, Schweinsburg BC, Krystal JH, et al. Neuropsychological functioning in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: associations with performance validity, comorbidities, and functional outcomes. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2016;22(4):399-411.

11. Cook JM, O’Donnell C. Assessment and psychological treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in older adults. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2005;18(2):61-71.

12. Mota N, Tsai J, Kirwin PD, et al. Late-life exacerbation of PTSD symptoms in US veterans: results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(3):348-354.

13. Yaffe K, Vittinghoff E, Lindquist K, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and risk of dementia among US veterans. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(6):608-613.

1. Chopra MP, Zhang H, Pless Kaiser A, et al. PTSD is a chronic, fluctuating disorder affecting the mental quality of life in older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22(1):86-97.

2. Donovan NJ, Amariglio RE, Zoller AS, et al. Subjective cognitive concerns and neuropsychiatric predictors of progression to the early clinical stages of Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22(12):1642-1651.

3. Norrie LM, Diamond K, Hickie IB, Rogers NL, Fearns S, Naismith SL. Can older “at risk” adults benefit from psychoeducation targeting healthy brain aging? Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23(3):413-424.

4. Hopko DR, Robertson SMC, Lejuez CW. Behavioral activation for anxiety disorders. Behav Anal Today. 2006;7(2):212-232.

5. Schuitevoerder S, Rosen JW, Twamley EW, et al. A meta-analysis of cognitive functioning in older adults with PTSD. J Anxiety Disord. 2013;27(6):550-558.

6. Polusny MA, Erbes CR, Thuras P, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for posttraumatic stress disorder among veterans: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314(5):456-465.

7. Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1982-1983;17(1):37-49.

8. Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center. PTSD CheckList-Civilian Version (PCL-C). http://www.mirecc.va.gov/docs/visn6/3_PTSD _CheckList_and_Scoring.pdf Published December 2013. Accessed November 3, 2016.

9. Scott JC, Matt GE, Wrocklage KM, et al. A quantitative meta-analysis of neurocognitive functioning in posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychol Bull. 2015;141(1):105-140.

10. Wrocklage KM, Schweinsburg BC, Krystal JH, et al. Neuropsychological functioning in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: associations with performance validity, comorbidities, and functional outcomes. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2016;22(4):399-411.

11. Cook JM, O’Donnell C. Assessment and psychological treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in older adults. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2005;18(2):61-71.

12. Mota N, Tsai J, Kirwin PD, et al. Late-life exacerbation of PTSD symptoms in US veterans: results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(3):348-354.

13. Yaffe K, Vittinghoff E, Lindquist K, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and risk of dementia among US veterans. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(6):608-613.