User login

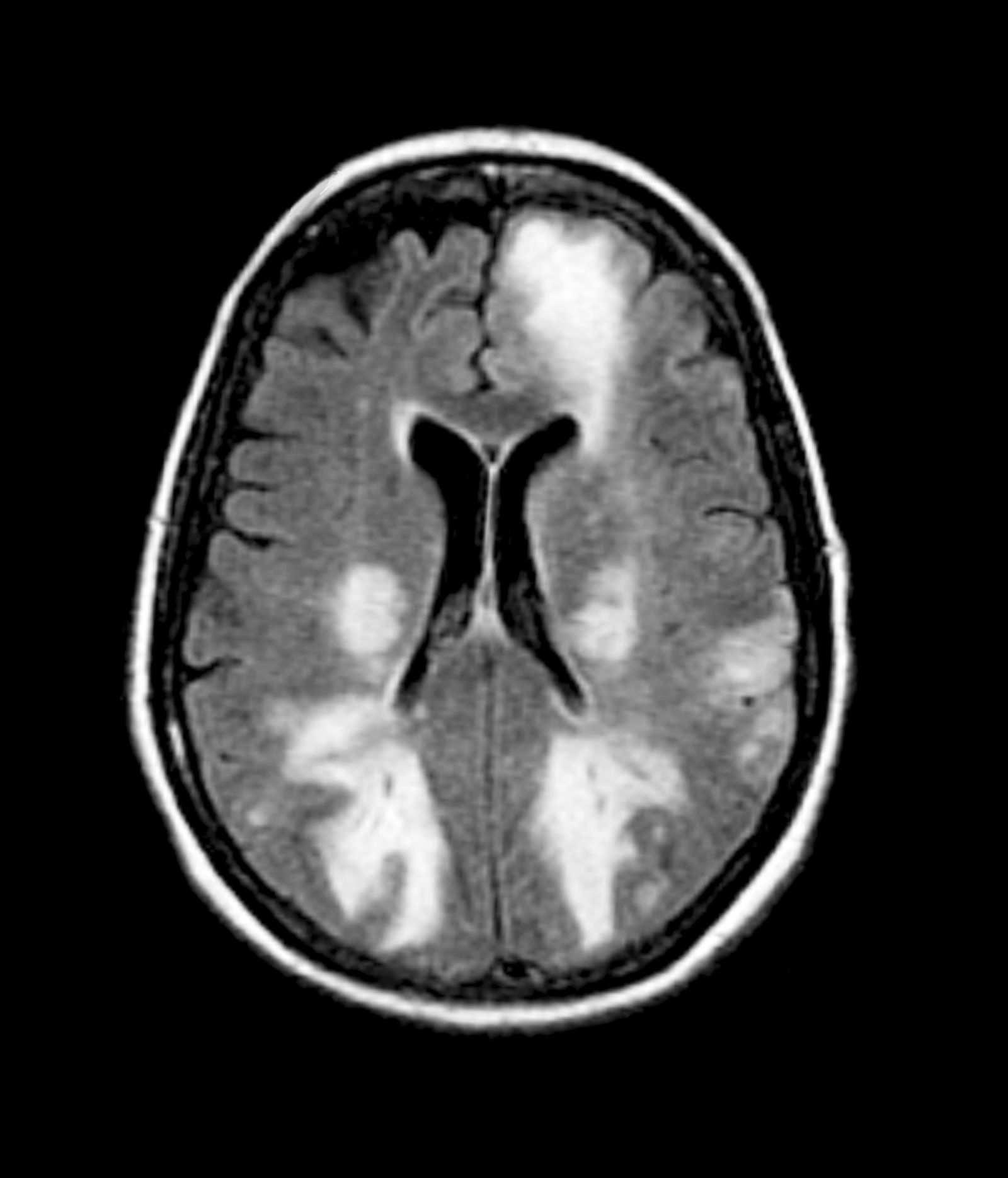

Given the patient's results on the genetic panel and MRI, as well as the noted cognitive decline and increased aggression, this patient is suspected of having limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy (LATE) secondary to AD and is referred to the neurologist on her multidisciplinary care team for further consultation and testing.

AD is one of the most common forms of dementia. More than 6 million people in the United States have clinical AD or mild cognitive impairment because of AD. LATE is a new classification of dementia, identified in 2019, that mimics AD but is a unique disease entity driven by the misfolding of the protein TDP-43, which regulates gene expression in the brain. Misfolded TDP-43 protein is common among older adults aged ≥ 85 years, and about a quarter of this population has enough misfolded TDP-43 protein to affect their memory and cognition.

Diagnosing AD currently relies on a clinical approach. A complete physical examination, with a detailed neurologic examination and a mental status examination, is used to evaluate disease stage. Initial mental status testing evaluates attention and concentration, recent and remote memory, language, praxis, executive function, and visuospatial function. Because LATE is a newly discovered form of dementia, there are no set guidelines on diagnosing LATE and no robust biomarker for TDP-43. What is known about LATE has been gleaned mostly from retrospective clinicopathologic studies.

The LATE consensus working group reports that the clinical course of disease, as studied by autopsy-proven LATE neuropathologic change (LATE-NC), is described as an "amnestic cognitive syndrome that can evolve to incorporate multiple cognitive domains and ultimately to impair activities of daily living." Researchers are currently analyzing different clinical assessments and neuroimaging with MRI to characterize LATE. A group of international researchers recently published a set of clinical criteria for limbic-predominant amnestic neurodegenerative syndrome (LANS), which is associated with LATE-NC. Their criteria include "core, standard and advanced features that are measurable in vivo, including older age at evaluation, mild clinical syndrome, disproportionate hippocampal atrophy, impaired semantic memory, limbic hypometabolism, absence of neocortical degenerative patterns and low likelihood of neocortical tau, with degrees of certainty (highest, high, moderate, low)." Other neuroimaging studies of autopsy-confirmed LATE-NC have shown that atrophy is mostly focused in the medial temporal lobe with marked reduced hippocampal volume.

The group reports that LATE and AD probably share pathophysiologic mechanisms. One of the universally accepted hallmarks of AD is the formation of beta-amyloid plaques, which are dense, mostly insoluble deposits of beta-amyloid protein that develop around neurons in the hippocampus and other regions in the cerebral cortex used for decision-making. These plaques disrupt brain function and lead to brain atrophy. The LATE group also reports that this same pathology has been noted with LATE: "Many subjects with LATE-NC have comorbid brain pathologies, often including amyloid-beta plaques and tauopathy." That said, genetic studies have helped identify five genes with risk alleles for LATE (GRN, TMEM106B, ABCC9, KCNMB2, and APOE), suggesting disease-specific underlying mechanisms compared to AD.

Patient and caregiver education and guidance is vital with a dementia diagnosis. If LATE and/or AD are suspected, physicians should encourage the involvement of family and friends who agree to become more involved in the patient's care as the disease progresses. These individuals need to understand the patient's wishes around care, especially for the future when the patient is no longer able to make decisions. The patient may also consider establishing medical advance directives and durable power of attorney for medical and financial decision-making. Caregivers supporting the patient are encouraged to help balance the physical needs of the patient while maintaining respect for them as a competent adult to the extent allowed by the progression of their disease.

Because LATE is a new classification of dementia, there are no known effective treatments. One ongoing study is testing the use of autologous bone marrow–derived stem cells to help improve cognitive impairment among patients with LATE, AD, and other dementias. Current AD treatments are focused on symptomatic therapies that modulate neurotransmitters — either acetylcholine or glutamate. The standard medical treatment includes cholinesterase inhibitors and a partial N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist. Two amyloid-directed antibodies (aducanumab, lecanemab) are currently available in the United States for individuals with AD exhibiting mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia. A third agent currently in clinical trials (donanemab) has shown significantly slowed clinical progression after 1.5 years among clinical trial participants with early symptomatic AD and amyloid and tau pathology.

Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, Chief of Pain Management, Carilion Clinic and Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, Roanoke, Virginia.

Disclosure: Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Given the patient's results on the genetic panel and MRI, as well as the noted cognitive decline and increased aggression, this patient is suspected of having limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy (LATE) secondary to AD and is referred to the neurologist on her multidisciplinary care team for further consultation and testing.

AD is one of the most common forms of dementia. More than 6 million people in the United States have clinical AD or mild cognitive impairment because of AD. LATE is a new classification of dementia, identified in 2019, that mimics AD but is a unique disease entity driven by the misfolding of the protein TDP-43, which regulates gene expression in the brain. Misfolded TDP-43 protein is common among older adults aged ≥ 85 years, and about a quarter of this population has enough misfolded TDP-43 protein to affect their memory and cognition.

Diagnosing AD currently relies on a clinical approach. A complete physical examination, with a detailed neurologic examination and a mental status examination, is used to evaluate disease stage. Initial mental status testing evaluates attention and concentration, recent and remote memory, language, praxis, executive function, and visuospatial function. Because LATE is a newly discovered form of dementia, there are no set guidelines on diagnosing LATE and no robust biomarker for TDP-43. What is known about LATE has been gleaned mostly from retrospective clinicopathologic studies.

The LATE consensus working group reports that the clinical course of disease, as studied by autopsy-proven LATE neuropathologic change (LATE-NC), is described as an "amnestic cognitive syndrome that can evolve to incorporate multiple cognitive domains and ultimately to impair activities of daily living." Researchers are currently analyzing different clinical assessments and neuroimaging with MRI to characterize LATE. A group of international researchers recently published a set of clinical criteria for limbic-predominant amnestic neurodegenerative syndrome (LANS), which is associated with LATE-NC. Their criteria include "core, standard and advanced features that are measurable in vivo, including older age at evaluation, mild clinical syndrome, disproportionate hippocampal atrophy, impaired semantic memory, limbic hypometabolism, absence of neocortical degenerative patterns and low likelihood of neocortical tau, with degrees of certainty (highest, high, moderate, low)." Other neuroimaging studies of autopsy-confirmed LATE-NC have shown that atrophy is mostly focused in the medial temporal lobe with marked reduced hippocampal volume.

The group reports that LATE and AD probably share pathophysiologic mechanisms. One of the universally accepted hallmarks of AD is the formation of beta-amyloid plaques, which are dense, mostly insoluble deposits of beta-amyloid protein that develop around neurons in the hippocampus and other regions in the cerebral cortex used for decision-making. These plaques disrupt brain function and lead to brain atrophy. The LATE group also reports that this same pathology has been noted with LATE: "Many subjects with LATE-NC have comorbid brain pathologies, often including amyloid-beta plaques and tauopathy." That said, genetic studies have helped identify five genes with risk alleles for LATE (GRN, TMEM106B, ABCC9, KCNMB2, and APOE), suggesting disease-specific underlying mechanisms compared to AD.

Patient and caregiver education and guidance is vital with a dementia diagnosis. If LATE and/or AD are suspected, physicians should encourage the involvement of family and friends who agree to become more involved in the patient's care as the disease progresses. These individuals need to understand the patient's wishes around care, especially for the future when the patient is no longer able to make decisions. The patient may also consider establishing medical advance directives and durable power of attorney for medical and financial decision-making. Caregivers supporting the patient are encouraged to help balance the physical needs of the patient while maintaining respect for them as a competent adult to the extent allowed by the progression of their disease.

Because LATE is a new classification of dementia, there are no known effective treatments. One ongoing study is testing the use of autologous bone marrow–derived stem cells to help improve cognitive impairment among patients with LATE, AD, and other dementias. Current AD treatments are focused on symptomatic therapies that modulate neurotransmitters — either acetylcholine or glutamate. The standard medical treatment includes cholinesterase inhibitors and a partial N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist. Two amyloid-directed antibodies (aducanumab, lecanemab) are currently available in the United States for individuals with AD exhibiting mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia. A third agent currently in clinical trials (donanemab) has shown significantly slowed clinical progression after 1.5 years among clinical trial participants with early symptomatic AD and amyloid and tau pathology.

Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, Chief of Pain Management, Carilion Clinic and Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, Roanoke, Virginia.

Disclosure: Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Given the patient's results on the genetic panel and MRI, as well as the noted cognitive decline and increased aggression, this patient is suspected of having limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy (LATE) secondary to AD and is referred to the neurologist on her multidisciplinary care team for further consultation and testing.

AD is one of the most common forms of dementia. More than 6 million people in the United States have clinical AD or mild cognitive impairment because of AD. LATE is a new classification of dementia, identified in 2019, that mimics AD but is a unique disease entity driven by the misfolding of the protein TDP-43, which regulates gene expression in the brain. Misfolded TDP-43 protein is common among older adults aged ≥ 85 years, and about a quarter of this population has enough misfolded TDP-43 protein to affect their memory and cognition.

Diagnosing AD currently relies on a clinical approach. A complete physical examination, with a detailed neurologic examination and a mental status examination, is used to evaluate disease stage. Initial mental status testing evaluates attention and concentration, recent and remote memory, language, praxis, executive function, and visuospatial function. Because LATE is a newly discovered form of dementia, there are no set guidelines on diagnosing LATE and no robust biomarker for TDP-43. What is known about LATE has been gleaned mostly from retrospective clinicopathologic studies.

The LATE consensus working group reports that the clinical course of disease, as studied by autopsy-proven LATE neuropathologic change (LATE-NC), is described as an "amnestic cognitive syndrome that can evolve to incorporate multiple cognitive domains and ultimately to impair activities of daily living." Researchers are currently analyzing different clinical assessments and neuroimaging with MRI to characterize LATE. A group of international researchers recently published a set of clinical criteria for limbic-predominant amnestic neurodegenerative syndrome (LANS), which is associated with LATE-NC. Their criteria include "core, standard and advanced features that are measurable in vivo, including older age at evaluation, mild clinical syndrome, disproportionate hippocampal atrophy, impaired semantic memory, limbic hypometabolism, absence of neocortical degenerative patterns and low likelihood of neocortical tau, with degrees of certainty (highest, high, moderate, low)." Other neuroimaging studies of autopsy-confirmed LATE-NC have shown that atrophy is mostly focused in the medial temporal lobe with marked reduced hippocampal volume.

The group reports that LATE and AD probably share pathophysiologic mechanisms. One of the universally accepted hallmarks of AD is the formation of beta-amyloid plaques, which are dense, mostly insoluble deposits of beta-amyloid protein that develop around neurons in the hippocampus and other regions in the cerebral cortex used for decision-making. These plaques disrupt brain function and lead to brain atrophy. The LATE group also reports that this same pathology has been noted with LATE: "Many subjects with LATE-NC have comorbid brain pathologies, often including amyloid-beta plaques and tauopathy." That said, genetic studies have helped identify five genes with risk alleles for LATE (GRN, TMEM106B, ABCC9, KCNMB2, and APOE), suggesting disease-specific underlying mechanisms compared to AD.

Patient and caregiver education and guidance is vital with a dementia diagnosis. If LATE and/or AD are suspected, physicians should encourage the involvement of family and friends who agree to become more involved in the patient's care as the disease progresses. These individuals need to understand the patient's wishes around care, especially for the future when the patient is no longer able to make decisions. The patient may also consider establishing medical advance directives and durable power of attorney for medical and financial decision-making. Caregivers supporting the patient are encouraged to help balance the physical needs of the patient while maintaining respect for them as a competent adult to the extent allowed by the progression of their disease.

Because LATE is a new classification of dementia, there are no known effective treatments. One ongoing study is testing the use of autologous bone marrow–derived stem cells to help improve cognitive impairment among patients with LATE, AD, and other dementias. Current AD treatments are focused on symptomatic therapies that modulate neurotransmitters — either acetylcholine or glutamate. The standard medical treatment includes cholinesterase inhibitors and a partial N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist. Two amyloid-directed antibodies (aducanumab, lecanemab) are currently available in the United States for individuals with AD exhibiting mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia. A third agent currently in clinical trials (donanemab) has shown significantly slowed clinical progression after 1.5 years among clinical trial participants with early symptomatic AD and amyloid and tau pathology.

Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, Chief of Pain Management, Carilion Clinic and Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, Roanoke, Virginia.

Disclosure: Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

An 85-year-old woman presents to her geriatrician with her daughter, who is her primary caregiver. Seven years ago, the patient was diagnosed with mild Alzheimer's disease (AD). Her symptoms at diagnosis were irritability, forgetfulness, and panic attacks. Cognitive, behavioral, and functional assessments showed levels of decline; neurologic examination revealed mild hyposmia. The patient has been living with her daughter ever since her AD diagnosis.

At today's visit, the daughter reports that her mother has been experiencing loss of appetite and wide mood fluctuations with moments of unusual agitation. In addition, she tells the geriatrician that her mother has had trouble maintaining her balance and seems to have lost her sense of time. The patient has difficulty remembering what month and day it is, and how long it's been since her brother came to visit — which has been every Sunday like clockwork since the patient moved in with her daughter. The daughter also notes that her mother loses track of the story line when she is watching movie and TV shows lately.

The physician orders a brain MRI and genetic panel. MRI reveals atrophy in the frontal cortex as well as the medial temporal lobe, with hippocampal sclerosis. The genetic panel shows APOE and TMEM106 mutations.