User login

Most U.S. mainland pediatric practitioners will see only one or two cases of Kawasaki disease (KD) in their careers, but no one wants to miss even one case.

Making the diagnosis as early as possible is important to reduce the chance of sequelae, particularly the coronary artery aneurysms that will eventually lead to 5% of overall acute coronary syndromes in adults. And because there is no “KD test,” or sometimes incomplete KD. And there are some new data that complicate this. Despite the recently updated 2017 guideline,1 most cases end up being confirmed and managed by regional “experts.” But nearly all of the approximately 6,000 KD cases/year in U.S. children younger than 5 years old start out with one or more primary care, urgent care, or ED visits.

This means that every clinician in the trenches not only needs a high index of suspicion but also needs to be at least a partial expert, too. What raises our index of suspicion? Classic data tell us we need 5 consecutive days of fever plus four or five other principal clinical findings for a KD diagnosis. The principal findings are:

1. Eyes: Bilateral bulbar nonexudative conjunctival injection.

2. Mouth: Erythema of oral/pharyngeal mucosa or cracked lips or strawberry tongue or oral mucositis.

3. Rash.

4. Hands or feet findings: Swelling/erythema or later periungual desquamation.

5. Cervical adenopathy greater than 1.4 cm, usually unilateral.

Other factors that have classically increased suspicion are winter/early spring presentation in North America, male gender (1.5:1 ratio to females), and Asian (particularly Japanese) ancestry. The importance of genetics was initially based on epidemiology (Japan/Asian risk) but lately has been further associated with six gene polymorphisms. However, molecular genetic testing is not currently a practical tool.

Clinical scenarios that also should raise suspicion include less-than-6-month-old infants with prolonged fever/irritability (may be the only clinical manifestations of KD) and children over 4 years old who more often may have incomplete KD. Both groups have higher prevalence of coronary artery abnormalities. Other high suspicion scenarios include prolonged fever with unexplained/culture-negative shock, or antibiotic treatment failure for cervical adenitis or retro/parapharyngeal phlegmon. Consultation with or referral to a regional KD expert may be needed.

Fuzzy KD math

Current guidelines list an exception to the 5-day fever requirement in that only 4 days of fever are needed with four or more principal clinical features, particularly when hand and feet findings exist. Some call this the “4X4 exception.” Then there is a sub-caveat: “Experienced clinicians who have treated many patients with KD may establish the diagnosis with 3 days of fever in rare cases.”1

Incomplete KD

This is another exception, which seems to be a more frequent diagnosis in the past decade. Incomplete KD requires the 5 days of fever duration plus an elevated C-reactive protein or erythrocyte sedimentation rate. But one needs only two or three of the five principal clinical KD criteria plus three or more of six other laboratory findings (anemia, low albumin, leukocytosis, thrombocytosis, pyuria, or elevated alanine aminotransferase). Incomplete KD can be confirmed by an abnormal echocardiogram – usually not until after 7 days of KD symptoms.1

New KD nuances

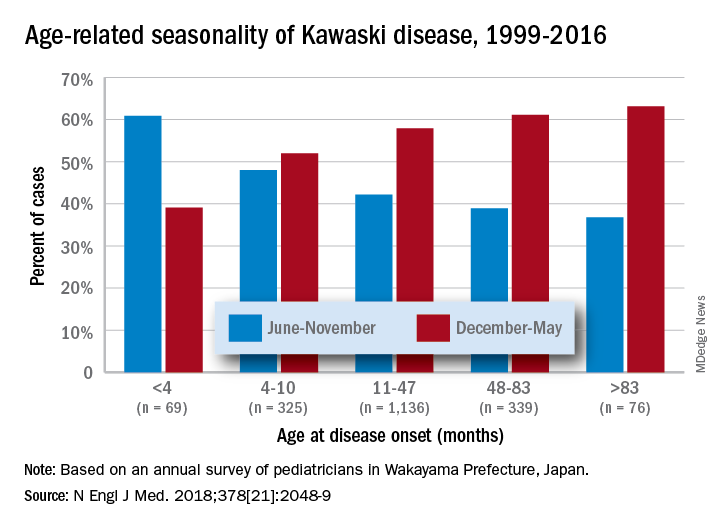

In a recent report on 20 years of data from Japan (n = 1,945 KD cases), more granularity on age, seasonal epidemiology, and outcome were seen.2 There was an inverse correlation of male predominance to age, i.e. as age groups got older, there was a gradual shift to female predominance by 7 years of age. The winter/spring predominance (60% of overall cases) did not hold true in younger age groups where summer/fall was the peak season (65% of cases).

With the goal of not missing any KD and diagnosing as early as possible to limit sequelae, we all need to be relative experts and keep alert for clinical scenarios that warrant our raising our index of suspicion. But now the seasonality trends appear blurred in the youngest cases and the male predominance is blurred in the oldest cases. And remember that fever and irritability for longer than 7 days in young infants may be the only clue to KD.

Dr. Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Kansas City, Mo. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Circulation. 2017 Mar 29. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000484

2. N Engl J Med. 2018 May 24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1804312.

Most U.S. mainland pediatric practitioners will see only one or two cases of Kawasaki disease (KD) in their careers, but no one wants to miss even one case.

Making the diagnosis as early as possible is important to reduce the chance of sequelae, particularly the coronary artery aneurysms that will eventually lead to 5% of overall acute coronary syndromes in adults. And because there is no “KD test,” or sometimes incomplete KD. And there are some new data that complicate this. Despite the recently updated 2017 guideline,1 most cases end up being confirmed and managed by regional “experts.” But nearly all of the approximately 6,000 KD cases/year in U.S. children younger than 5 years old start out with one or more primary care, urgent care, or ED visits.

This means that every clinician in the trenches not only needs a high index of suspicion but also needs to be at least a partial expert, too. What raises our index of suspicion? Classic data tell us we need 5 consecutive days of fever plus four or five other principal clinical findings for a KD diagnosis. The principal findings are:

1. Eyes: Bilateral bulbar nonexudative conjunctival injection.

2. Mouth: Erythema of oral/pharyngeal mucosa or cracked lips or strawberry tongue or oral mucositis.

3. Rash.

4. Hands or feet findings: Swelling/erythema or later periungual desquamation.

5. Cervical adenopathy greater than 1.4 cm, usually unilateral.

Other factors that have classically increased suspicion are winter/early spring presentation in North America, male gender (1.5:1 ratio to females), and Asian (particularly Japanese) ancestry. The importance of genetics was initially based on epidemiology (Japan/Asian risk) but lately has been further associated with six gene polymorphisms. However, molecular genetic testing is not currently a practical tool.

Clinical scenarios that also should raise suspicion include less-than-6-month-old infants with prolonged fever/irritability (may be the only clinical manifestations of KD) and children over 4 years old who more often may have incomplete KD. Both groups have higher prevalence of coronary artery abnormalities. Other high suspicion scenarios include prolonged fever with unexplained/culture-negative shock, or antibiotic treatment failure for cervical adenitis or retro/parapharyngeal phlegmon. Consultation with or referral to a regional KD expert may be needed.

Fuzzy KD math

Current guidelines list an exception to the 5-day fever requirement in that only 4 days of fever are needed with four or more principal clinical features, particularly when hand and feet findings exist. Some call this the “4X4 exception.” Then there is a sub-caveat: “Experienced clinicians who have treated many patients with KD may establish the diagnosis with 3 days of fever in rare cases.”1

Incomplete KD

This is another exception, which seems to be a more frequent diagnosis in the past decade. Incomplete KD requires the 5 days of fever duration plus an elevated C-reactive protein or erythrocyte sedimentation rate. But one needs only two or three of the five principal clinical KD criteria plus three or more of six other laboratory findings (anemia, low albumin, leukocytosis, thrombocytosis, pyuria, or elevated alanine aminotransferase). Incomplete KD can be confirmed by an abnormal echocardiogram – usually not until after 7 days of KD symptoms.1

New KD nuances

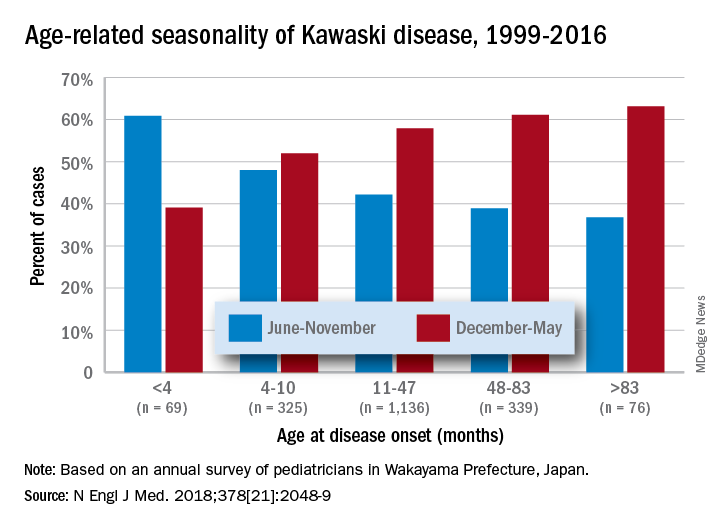

In a recent report on 20 years of data from Japan (n = 1,945 KD cases), more granularity on age, seasonal epidemiology, and outcome were seen.2 There was an inverse correlation of male predominance to age, i.e. as age groups got older, there was a gradual shift to female predominance by 7 years of age. The winter/spring predominance (60% of overall cases) did not hold true in younger age groups where summer/fall was the peak season (65% of cases).

With the goal of not missing any KD and diagnosing as early as possible to limit sequelae, we all need to be relative experts and keep alert for clinical scenarios that warrant our raising our index of suspicion. But now the seasonality trends appear blurred in the youngest cases and the male predominance is blurred in the oldest cases. And remember that fever and irritability for longer than 7 days in young infants may be the only clue to KD.

Dr. Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Kansas City, Mo. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Circulation. 2017 Mar 29. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000484

2. N Engl J Med. 2018 May 24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1804312.

Most U.S. mainland pediatric practitioners will see only one or two cases of Kawasaki disease (KD) in their careers, but no one wants to miss even one case.

Making the diagnosis as early as possible is important to reduce the chance of sequelae, particularly the coronary artery aneurysms that will eventually lead to 5% of overall acute coronary syndromes in adults. And because there is no “KD test,” or sometimes incomplete KD. And there are some new data that complicate this. Despite the recently updated 2017 guideline,1 most cases end up being confirmed and managed by regional “experts.” But nearly all of the approximately 6,000 KD cases/year in U.S. children younger than 5 years old start out with one or more primary care, urgent care, or ED visits.

This means that every clinician in the trenches not only needs a high index of suspicion but also needs to be at least a partial expert, too. What raises our index of suspicion? Classic data tell us we need 5 consecutive days of fever plus four or five other principal clinical findings for a KD diagnosis. The principal findings are:

1. Eyes: Bilateral bulbar nonexudative conjunctival injection.

2. Mouth: Erythema of oral/pharyngeal mucosa or cracked lips or strawberry tongue or oral mucositis.

3. Rash.

4. Hands or feet findings: Swelling/erythema or later periungual desquamation.

5. Cervical adenopathy greater than 1.4 cm, usually unilateral.

Other factors that have classically increased suspicion are winter/early spring presentation in North America, male gender (1.5:1 ratio to females), and Asian (particularly Japanese) ancestry. The importance of genetics was initially based on epidemiology (Japan/Asian risk) but lately has been further associated with six gene polymorphisms. However, molecular genetic testing is not currently a practical tool.

Clinical scenarios that also should raise suspicion include less-than-6-month-old infants with prolonged fever/irritability (may be the only clinical manifestations of KD) and children over 4 years old who more often may have incomplete KD. Both groups have higher prevalence of coronary artery abnormalities. Other high suspicion scenarios include prolonged fever with unexplained/culture-negative shock, or antibiotic treatment failure for cervical adenitis or retro/parapharyngeal phlegmon. Consultation with or referral to a regional KD expert may be needed.

Fuzzy KD math

Current guidelines list an exception to the 5-day fever requirement in that only 4 days of fever are needed with four or more principal clinical features, particularly when hand and feet findings exist. Some call this the “4X4 exception.” Then there is a sub-caveat: “Experienced clinicians who have treated many patients with KD may establish the diagnosis with 3 days of fever in rare cases.”1

Incomplete KD

This is another exception, which seems to be a more frequent diagnosis in the past decade. Incomplete KD requires the 5 days of fever duration plus an elevated C-reactive protein or erythrocyte sedimentation rate. But one needs only two or three of the five principal clinical KD criteria plus three or more of six other laboratory findings (anemia, low albumin, leukocytosis, thrombocytosis, pyuria, or elevated alanine aminotransferase). Incomplete KD can be confirmed by an abnormal echocardiogram – usually not until after 7 days of KD symptoms.1

New KD nuances

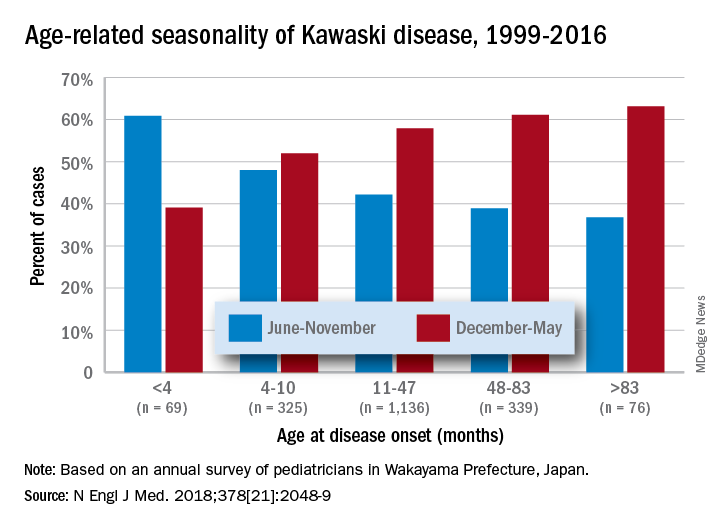

In a recent report on 20 years of data from Japan (n = 1,945 KD cases), more granularity on age, seasonal epidemiology, and outcome were seen.2 There was an inverse correlation of male predominance to age, i.e. as age groups got older, there was a gradual shift to female predominance by 7 years of age. The winter/spring predominance (60% of overall cases) did not hold true in younger age groups where summer/fall was the peak season (65% of cases).

With the goal of not missing any KD and diagnosing as early as possible to limit sequelae, we all need to be relative experts and keep alert for clinical scenarios that warrant our raising our index of suspicion. But now the seasonality trends appear blurred in the youngest cases and the male predominance is blurred in the oldest cases. And remember that fever and irritability for longer than 7 days in young infants may be the only clue to KD.

Dr. Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Kansas City, Mo. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Circulation. 2017 Mar 29. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000484

2. N Engl J Med. 2018 May 24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1804312.