User login

The Diagnosis: Mycobacterium chelonae Arising Within a Tattoo

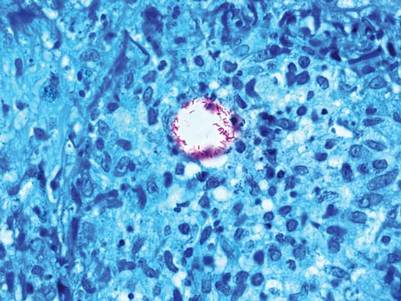

A 3-mm punch biopsy specimen was obtained from one of the plaques. Histopathology revealed an unremarkable epidermis with granulomatous collections of epithelioid histiocytes in association with neutrophils and lymphocytes in the dermis (Figure 1). Periodic acid–Schiff stain was negative for fungal organisms. Gram stain was negative for bacteria. Fite stain was positive for acid-fast bacilli (Figure 2). Clinical and histopathologic findings led to the initial diagnosis of a mycobacterial infection within the tattoo. The patient was empirically started on oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and oral clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily with mild improvement of the lesions over the next month. After 6 weeks the mycobacterial cultures were persistently negative and high-performance liquid chromatography was performed verifying the presence of Mycobacterium chelonae. Clarithromycin was continued and the doxycycline was replaced with oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (double strength) twice daily due to resistance. The patient was referred to an infectious disease specialist who concurred with the treatment regimen for a duration of 6 months to a year. A chest radiograph also was performed to rule out disseminated disease. Several months later the patient’s close friend presented with a similar infection that was acquired on the same day as our patient at the same tattoo parlor. The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene was notified about these cases and informed us of other cases in New York State linked to contaminated tattoo ink.

|

Mycobacterium chelonae is a rapidly growing nontuberculous mycobacteria (Runyon group IV) that is found in nature and contaminated sources such as soil, lakes, sewage, and tap water.1 Inoculation ofM chelonae through contaminated instruments leads to the formation of painful lesions, abscesses, fistulas, and granulomas that are extremely difficult to treat.2 In our patient, M chelonae was most likely transmitted via contaminated tap water that was used to dilute the black tattoo ink to yield a gray color. Alternative sources are the ink itself or the container used to mix the ink.3Mycobacterium chelonae can cause infections in the skin, lungs, joints, bones, and eyes.4 With the exception of lung disease, trauma is the usual inciting factor. Disseminated infections are almost exclusively found in immunosuppressed individuals. Mycobacterium chelonae is typically found to grow on culture within 7 days. However, in our case there was no growth after 6 weeks of incubation. High-performance liquid chromatography analysis of mycolic acid is an alternative method of identifying mycobacteria. This technique verified the presence of M chelonae in our case when cultures were persistently negative.5

Mycobacterium chelonae is difficult to treat. The most common antibiotics used for treatment are clarithromycin, azithromycin, doxycycline, and linezolid.6 Studies of various antibiotics have shown that clarithromycin is the most effective macrolide against M chelonae.7 Tetracyclines also were studied in their effectiveness at treating nontuberculous mycobacteria infections but were found to have increased resistance to M chelonae.8 Although treatment regimens vary, the highest success rates are achieved with a minimum of 6 months of therapy using at least 2 drugs. Longer treatment is recommended for immunocompromised individuals.9

The case we present is important from a public health perspective. The tattoo industry and ink manufacturers should bemade aware of the risks of various infections from nonsterile techniques. Tattoo parlor employees should be advised of the risks of using nonsterile water for ink dilution and cleaning tattoo equipment. They also should be continuously educated on aseptic techniques.

1. Lee RP, Cheung KW, Chiu KH, et al. Mycobacterium chelonae infection after total knee arthroplasty: a case report. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2012;20:134-136.

2. Camargo D, Saad C, Ruiz F, et al. latrogenic outbreak of M. chelonae skin abscesses. Epidemiol Infect. 1996;117:113-119.

3. Rodríguez-Blanco I, Fernández LC, Suárez-Peñaranda JM, et al. Mycobacterium chelonae infection associated with tattoos. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:61-62.

4. Karak K, Bhattacharyya S, Majumdar S, et al. Pulmonary infections caused by mycobacteria other than M. tuberculosis in and around Calcutta. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 1996;39:131-134.

5. Butler WR, Floyd MM, Silcox V, et al. Standardized Method for HPLC Identification of Mycobacteria. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 1996.

6. Brown-Elliot BA, Wallace RJ Jr, Blinkhorn R, et al. Successful treatment of disseminated Mycobacterium chelonae infection with linezolid. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:1433-1434.

7. Brown BA, Wallace RJ Jr, Onyi GO, et al. Activities of four macrolides, including clarithromycin, against Mycobacterium fortuitum, Mycobacterium chelonae, and Mycobacterium chelonae-like organisms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:180-184.

8. Swenson JM, Wallace RJ Jr, Silcox VA, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of five subgroups of Mycobacterium fortuitum and Mycobacterium chelonae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985;28:807-811.

9. Leung YY, Choi KW, Ho KM, et al. Disseminated cutaneous infection with Mycobacterium chelonae mimicking panniculitis in a patient with dermatomyositis. Hong Kong Med J. 2005;11:515-519.

The Diagnosis: Mycobacterium chelonae Arising Within a Tattoo

A 3-mm punch biopsy specimen was obtained from one of the plaques. Histopathology revealed an unremarkable epidermis with granulomatous collections of epithelioid histiocytes in association with neutrophils and lymphocytes in the dermis (Figure 1). Periodic acid–Schiff stain was negative for fungal organisms. Gram stain was negative for bacteria. Fite stain was positive for acid-fast bacilli (Figure 2). Clinical and histopathologic findings led to the initial diagnosis of a mycobacterial infection within the tattoo. The patient was empirically started on oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and oral clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily with mild improvement of the lesions over the next month. After 6 weeks the mycobacterial cultures were persistently negative and high-performance liquid chromatography was performed verifying the presence of Mycobacterium chelonae. Clarithromycin was continued and the doxycycline was replaced with oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (double strength) twice daily due to resistance. The patient was referred to an infectious disease specialist who concurred with the treatment regimen for a duration of 6 months to a year. A chest radiograph also was performed to rule out disseminated disease. Several months later the patient’s close friend presented with a similar infection that was acquired on the same day as our patient at the same tattoo parlor. The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene was notified about these cases and informed us of other cases in New York State linked to contaminated tattoo ink.

|

Mycobacterium chelonae is a rapidly growing nontuberculous mycobacteria (Runyon group IV) that is found in nature and contaminated sources such as soil, lakes, sewage, and tap water.1 Inoculation ofM chelonae through contaminated instruments leads to the formation of painful lesions, abscesses, fistulas, and granulomas that are extremely difficult to treat.2 In our patient, M chelonae was most likely transmitted via contaminated tap water that was used to dilute the black tattoo ink to yield a gray color. Alternative sources are the ink itself or the container used to mix the ink.3Mycobacterium chelonae can cause infections in the skin, lungs, joints, bones, and eyes.4 With the exception of lung disease, trauma is the usual inciting factor. Disseminated infections are almost exclusively found in immunosuppressed individuals. Mycobacterium chelonae is typically found to grow on culture within 7 days. However, in our case there was no growth after 6 weeks of incubation. High-performance liquid chromatography analysis of mycolic acid is an alternative method of identifying mycobacteria. This technique verified the presence of M chelonae in our case when cultures were persistently negative.5

Mycobacterium chelonae is difficult to treat. The most common antibiotics used for treatment are clarithromycin, azithromycin, doxycycline, and linezolid.6 Studies of various antibiotics have shown that clarithromycin is the most effective macrolide against M chelonae.7 Tetracyclines also were studied in their effectiveness at treating nontuberculous mycobacteria infections but were found to have increased resistance to M chelonae.8 Although treatment regimens vary, the highest success rates are achieved with a minimum of 6 months of therapy using at least 2 drugs. Longer treatment is recommended for immunocompromised individuals.9

The case we present is important from a public health perspective. The tattoo industry and ink manufacturers should bemade aware of the risks of various infections from nonsterile techniques. Tattoo parlor employees should be advised of the risks of using nonsterile water for ink dilution and cleaning tattoo equipment. They also should be continuously educated on aseptic techniques.

The Diagnosis: Mycobacterium chelonae Arising Within a Tattoo

A 3-mm punch biopsy specimen was obtained from one of the plaques. Histopathology revealed an unremarkable epidermis with granulomatous collections of epithelioid histiocytes in association with neutrophils and lymphocytes in the dermis (Figure 1). Periodic acid–Schiff stain was negative for fungal organisms. Gram stain was negative for bacteria. Fite stain was positive for acid-fast bacilli (Figure 2). Clinical and histopathologic findings led to the initial diagnosis of a mycobacterial infection within the tattoo. The patient was empirically started on oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and oral clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily with mild improvement of the lesions over the next month. After 6 weeks the mycobacterial cultures were persistently negative and high-performance liquid chromatography was performed verifying the presence of Mycobacterium chelonae. Clarithromycin was continued and the doxycycline was replaced with oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (double strength) twice daily due to resistance. The patient was referred to an infectious disease specialist who concurred with the treatment regimen for a duration of 6 months to a year. A chest radiograph also was performed to rule out disseminated disease. Several months later the patient’s close friend presented with a similar infection that was acquired on the same day as our patient at the same tattoo parlor. The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene was notified about these cases and informed us of other cases in New York State linked to contaminated tattoo ink.

|

Mycobacterium chelonae is a rapidly growing nontuberculous mycobacteria (Runyon group IV) that is found in nature and contaminated sources such as soil, lakes, sewage, and tap water.1 Inoculation ofM chelonae through contaminated instruments leads to the formation of painful lesions, abscesses, fistulas, and granulomas that are extremely difficult to treat.2 In our patient, M chelonae was most likely transmitted via contaminated tap water that was used to dilute the black tattoo ink to yield a gray color. Alternative sources are the ink itself or the container used to mix the ink.3Mycobacterium chelonae can cause infections in the skin, lungs, joints, bones, and eyes.4 With the exception of lung disease, trauma is the usual inciting factor. Disseminated infections are almost exclusively found in immunosuppressed individuals. Mycobacterium chelonae is typically found to grow on culture within 7 days. However, in our case there was no growth after 6 weeks of incubation. High-performance liquid chromatography analysis of mycolic acid is an alternative method of identifying mycobacteria. This technique verified the presence of M chelonae in our case when cultures were persistently negative.5

Mycobacterium chelonae is difficult to treat. The most common antibiotics used for treatment are clarithromycin, azithromycin, doxycycline, and linezolid.6 Studies of various antibiotics have shown that clarithromycin is the most effective macrolide against M chelonae.7 Tetracyclines also were studied in their effectiveness at treating nontuberculous mycobacteria infections but were found to have increased resistance to M chelonae.8 Although treatment regimens vary, the highest success rates are achieved with a minimum of 6 months of therapy using at least 2 drugs. Longer treatment is recommended for immunocompromised individuals.9

The case we present is important from a public health perspective. The tattoo industry and ink manufacturers should bemade aware of the risks of various infections from nonsterile techniques. Tattoo parlor employees should be advised of the risks of using nonsterile water for ink dilution and cleaning tattoo equipment. They also should be continuously educated on aseptic techniques.

1. Lee RP, Cheung KW, Chiu KH, et al. Mycobacterium chelonae infection after total knee arthroplasty: a case report. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2012;20:134-136.

2. Camargo D, Saad C, Ruiz F, et al. latrogenic outbreak of M. chelonae skin abscesses. Epidemiol Infect. 1996;117:113-119.

3. Rodríguez-Blanco I, Fernández LC, Suárez-Peñaranda JM, et al. Mycobacterium chelonae infection associated with tattoos. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:61-62.

4. Karak K, Bhattacharyya S, Majumdar S, et al. Pulmonary infections caused by mycobacteria other than M. tuberculosis in and around Calcutta. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 1996;39:131-134.

5. Butler WR, Floyd MM, Silcox V, et al. Standardized Method for HPLC Identification of Mycobacteria. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 1996.

6. Brown-Elliot BA, Wallace RJ Jr, Blinkhorn R, et al. Successful treatment of disseminated Mycobacterium chelonae infection with linezolid. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:1433-1434.

7. Brown BA, Wallace RJ Jr, Onyi GO, et al. Activities of four macrolides, including clarithromycin, against Mycobacterium fortuitum, Mycobacterium chelonae, and Mycobacterium chelonae-like organisms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:180-184.

8. Swenson JM, Wallace RJ Jr, Silcox VA, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of five subgroups of Mycobacterium fortuitum and Mycobacterium chelonae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985;28:807-811.

9. Leung YY, Choi KW, Ho KM, et al. Disseminated cutaneous infection with Mycobacterium chelonae mimicking panniculitis in a patient with dermatomyositis. Hong Kong Med J. 2005;11:515-519.

1. Lee RP, Cheung KW, Chiu KH, et al. Mycobacterium chelonae infection after total knee arthroplasty: a case report. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2012;20:134-136.

2. Camargo D, Saad C, Ruiz F, et al. latrogenic outbreak of M. chelonae skin abscesses. Epidemiol Infect. 1996;117:113-119.

3. Rodríguez-Blanco I, Fernández LC, Suárez-Peñaranda JM, et al. Mycobacterium chelonae infection associated with tattoos. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:61-62.

4. Karak K, Bhattacharyya S, Majumdar S, et al. Pulmonary infections caused by mycobacteria other than M. tuberculosis in and around Calcutta. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 1996;39:131-134.

5. Butler WR, Floyd MM, Silcox V, et al. Standardized Method for HPLC Identification of Mycobacteria. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 1996.

6. Brown-Elliot BA, Wallace RJ Jr, Blinkhorn R, et al. Successful treatment of disseminated Mycobacterium chelonae infection with linezolid. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:1433-1434.

7. Brown BA, Wallace RJ Jr, Onyi GO, et al. Activities of four macrolides, including clarithromycin, against Mycobacterium fortuitum, Mycobacterium chelonae, and Mycobacterium chelonae-like organisms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:180-184.

8. Swenson JM, Wallace RJ Jr, Silcox VA, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of five subgroups of Mycobacterium fortuitum and Mycobacterium chelonae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985;28:807-811.

9. Leung YY, Choi KW, Ho KM, et al. Disseminated cutaneous infection with Mycobacterium chelonae mimicking panniculitis in a patient with dermatomyositis. Hong Kong Med J. 2005;11:515-519.

A 21-year-old man presented with growing, mildly pruritic, cutaneous papules and plaques on the right extensor forearm of 3 weeks’ duration. The lesions appeared 1 week after receiving a tattoo on the arm. One year prior the patient had a similar tattoo placed on another section of the right arm without any complications. The patient was afebrile and denied a history of sarcoidosis. Physical examination revealed indurated erythematous papules and plaques on the right extensor forearm that were most prominent in the gray-colored areas of the tattoo.