User login

› Avoid scheduling annual visits exclusively for preventive care. A

› Institute simple practice changes to improve the preventive services you provide, such as implementing standing orders for influenza vaccines. A

› Adopt components of the chronic care model for preventive services wherever possible—using ancillary providers to remind patients to undergo colorectal cancer screening and recommending apps that support self-management, for example. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

For well over a century, the periodic health exam has been associated with the delivery of preventive services1—a model widely accepted by physicians and patients alike. Approximately 8% of ambulatory care visits are for check-ups, and more than 20% of US residents schedule a health exam annually.2

Periodic health exams, however, do not result in optimal preventive care. Evidence suggests that important preventive services, such as dietary counseling, occur at only 8% of such visits; that just 10 seconds, on average, is devoted to smoking cessation; and that 80% of the preventive services patients receive are delivered outside of scheduled health exams.2 Because physicians and patients alike understandably prioritize acute problems, any discussion of health maintenance issues during a periodic check-up is likely to occur despite the visit’s agenda, not as part of it.3-7

Primary care physicians and practices are increasingly being held accountable for their performance on preventive measures. With that in mind, being familiar with evidence-based guidelines relating to the delivery of preventive services in ambulatory care settings, such as those developed by the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF),8 is crucial. Identifying elements of the chronic care model that can be effectively applied to preventive care—and recognizing that the reactive acute care model is ineffective for both chronic illness and preventive services—is essential, as well.

Preventive care that's evidence-based

Good practice guidelines should have the following features, according to the Institute of Medicine:9

• Validity. Application would lead to the desired health and cost outcomes.

• Reliability/reproducibility. Others using the same data/interpretation would reach the same conclusion.

• Clinical applicability. Patient populations are appropriately defined.

• Clinical flexibility. Known or generally expected exceptions are identified.

• Clarity. Guideline uses unambiguous language with precise definitions.

• Multidisciplinary process. Developed with the participation of all key stakeholders.

• Scheduled review. Periodically reviewed and revised to incorporate new evidence/changing consensus.

• Documentation. Procedures used in development are well documented.

The USPSTF guidelines are consistent with these attributes.8

Some brief interventions fail

Guidelines are useful as practice standards for establishing preventive care goals, but their existence alone does not ensure the delivery of high-quality preventive services in an office setting. One key factor is time. It is estimated that a primary care physician with an average-sized patient panel would require an additional 7.4 hours per day to achieve 100% compliance with all of the USPSTF recommendations.10

Counseling, in particular, is an intervention that may be more effective in theory than in practice. Evidence suggests that even when primary care providers are trained in preventive counseling (and many are not), many brief interventions are not effective at creating sustained behavior change or health improvement.11

Others are effective

That’s not to say that there’s little that can be done. Use of standing orders for influenza vaccination is one example of an effective and easily implemented preventive measure that requires little or no additional physician time. Yet some doctors are resistant, fearing loss of control or lawsuits. In fact, the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program specifically provides protection against vaccinerelated malpractice claims.12 A standing order for office staff to arrange a screening mammogram is another effective intervention; it has been shown to improve screening rates by as much as 30%.13

Lessons from chronic illness management

Chronic illness care and preventive care have much in common.14 Both acknowledge the need for proactive screening and counseling to bring about behavior change. In addition, both require ongoing care and follow-up, as well as depend on links to community resources. And finally, both are resource-intensive—too resource-intensive, some say, to be delivered in a cost-effective manner.

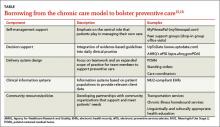

The Chronic Care Model has been proposed as a framework for improving preventive services (TABLE).15,16 Evidence suggests adopting some key components of chronic care can lead to significant gains in the delivery of preventive care, with the largest improvement seen when multiple components are used simultaneously.17-20

Self-management support. A growing body of evidence shows that self-management activities are associated with improved outcomes.21 Instituting a peer support group for pregnant women at a federally qualified health center, for example, led to a 7% absolute risk reduction in preterm births.22

Not all efforts to encourage self-management are effective, however, and evaluation is crucial to determine what works. In one large-scale trial, the use of patient reminder cards to facilitate a reduction in health risk behaviors such as tobacco use, risky drinking, unhealthy dietary patterns, and physical inactivity led to fewer health risk assessments being performed, fewer individual counseling encounters, and no change in these behaviors.23

Decision support. Clinical decision support systems, which generate patient-specific evidence-based assessments and/or recommendations that are actionable as part of the workflow at the point of care, have been found to improve care.24,25 An example of this is a prompt that reminds the physician to discuss chemoprevention with a patient at high risk for breast cancer.

Delivery system design. The patient-centered medical home (PCMH) is a well-known example of a redesign of health care delivery.26 Conversion to this model is associated with a small positive effect on preventive interventions.27 However, the persistence of a fee-for-service payment system—which does not include physician reimbursement for some of the added services incorporated into the PCMH—limits the implementation of the PCMH model.28

Many practices are improving health care delivery by using nonphysicians for various tasks related to preventive care. Care managers, for example, typically have smaller caseloads and focus on reducing unnecessary treatment for patients with high-risk conditions, such as congestive heart failure, while patient navigators generally have less clinical expertise but more knowledge of community services.

In one study, practice-initiated phone conversations with nonphysicians increased colorectal cancer screening by up to 40%.29 And in one pilot program, the use of ancillary providers led to an increase in colorectal cancer screening by as much as 123%.30 The human touch seems to be key to the success of these interventions. Passive reminders, such as videos being shown on waiting room televisions, have not proven to be effective.31

Clinical information systems. Early on, the power of electronic health records (EHRs) to improve practices’ delivery of preventive services was recognized. As early as 1995, the use of a reminder system to highlight such services during acute care visits was linked to improvements in counseling about smoking cessation and higher rates of cervical cancer screening, among other preventive measures.32,33 Overall, the use of EHRs alone has been shown to improve rates of preventive services by as much as 66%, with most practices reporting improvements of at least 20%.34

Today, EHRs that are Meaningful Use Stage 2-compliant have the tools needed to improve care. Requirements include the ability to generate patient registries of all those with a given disease and to identify patients on the registry who have not received needed care.35 To improve preventive care, registries should focus on the mitigation of risk factors, such as identifying—and contacting—patients with diabetes who are in need of, or overdue for, an annual eye exam.

Trials using the registry function, in combination with automated messaging to deliver targeted information to various patient groups (identified by the demographic information available from the EHR), are ongoing.

Community resources. Many clinicians have informal referral relationships with community organizations, such as the YMCA. Physician practices that establish links to community resources have the potential to have a large effect on unhealthy behaviors. (See “Putting theory into practice: 2 cases”.) However, a systematic review found that, while evidence to support such connections is mainly positive, research is limited and further evaluation is needed.36

The Practical Playbook (practicalplaybook.org)37 developed by the deBeaumont Foundation, Duke Department of Community and Family Medicine, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, offers concrete examples of how physician practices are linking with community resources to improve the health of the population. For example, Duke University’s “Just for Us” program provides in-home chronic illness care to 350 high-risk elderly individuals. The LATCH program connects thousands of Latino immigrants to health care services and culturally and linguistically appropriate health education classes.37

CASE 1

Dominic B, a 53-year-old patient, has scheduled a visit for a cough that has persisted for 4 weeks. The patient is a nonsmoker, is married, and has no first-degree relatives with cancer. But when you review his chart before the visit, you note that he missed his 6-month check-up for hypertension and hyperlipidemia. In addition, your electronic health record (EHR ) flags the fact that he has not undergone colorectal screening and that his immunizations are not current. Because you have standing orders in place, your medical assistant gives him a flu shot and a pamphlet providing information on colorectal cancer screening before you enter the room.

During the visit, Mr. B mentions that his father, age 82, recently had a heart attack. This event—reinforced by the postcards and phone messages he received from your office after he missed his 6-month follow-up—prompted him to reluctantly admit it was “time for a check-up.” You take the patient’s blood pressure (BP) and review his lipid panel (blood work was ordered prior to his visit) with him. He is relieved to know that he will not need to be on a statin and agrees to be screened for colorectal cancer using a sensitive stool study.

Before he leaves, the patient requests medication for erectile dysfunction—a problem he never reported before. You ask him to keep a diary and return in 2 months, and promise to discuss his erectile dysfunction at that time.

CASE 2

A review of your practice’s patient registry reveals that Gladys P, age 55, is behind on breast and cervical cancer screening. She has had only a few sporadic office visits, the last of which was for bronchitis 18 months ago. At that time, the patient’s systolic BP was 162 mm Hg. You told her you would recheck it in 6 weeks, but she failed to return for follow-up.

Ms. P smokes, but has no other chronic diseases and takes no medications. There is no record of a mammogram or Pap smear, and you don’t know whether she sees a gynecologist routinely. Your office contacts her and discovers that you are the only doctor she sees. The patient tells the medical assistant who placed the call that her car broke down but she has not had money to repair or replace it, so she has had no way to get to your office.

Your staff arranges for her to get a ride from a community volunteer group, first to the nearby hospital for a mammogram and then to your office, where you perform a Pap smear and address her elevated BP and smoking. You are rewarded for the counseling and preventive care with a letter and a bonus check from Ms. P’s insurance carrier, congratulating you on your quality improvement efforts.

Growing emphasis on quality

Systemic changes in the US health care system are occurring rapidly, with an emphasis on quality and improved outcomes. Many physicians are now required to submit data to external agencies for payment, and much of the data is grounded in preventive standards. Medicare’s Physicians Quality Reporting System requires that all Medicare providers provide data on preventive and chronic illness care. Rates of vaccination, obesity screening, and tobacco use screening are examples of preventive services that will be reported publicly on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ Physician Compare Web site.38

Physicians who work in accountable care organizations are required to meet quality standards on the delivery of certain preventive services, including breast cancer screening, colorectal cancer screening, influenza and pneumonia immunization, body mass index screening and follow-up, tobacco use screening and cessation intervention, screening for high blood pressure and followup, and screening for clinical depression and follow-up.39 As patients discover that the Affordable Care Act mandates that preventive services be covered with no cost sharing, they are likely to become more receptive to physician attempts to provide them.40,41

CORRESPONDENCE

Gerald Liu, MD, 1504 Springhill Avenue, Suite 3414, Mobile, AL 36604-3207; gliu@health.southalabama.edu

1. Han P. Historical changes in the objectives of the periodic health exam. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:910-917.

2. Mehrota A, Zaslavsky A, Anyanian J. Preventive health examinations and preventive gynecologic examinations in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1876-1883.

3. Jean CR, Stange KC, Nutting PA. Competing demands of primary care: a model for the delivery of clinical preventive services. J Fam Pract. 1994;38:166-171.

4. McGinnis JM, Foege WH. The immediate versus the important. JAMA. 2004;291:1263-1264.

5. Crabtree BF, Miller WL, Tallia AF, et al. Delivery of clinical preventive services in family medicine offices. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3:430-435.

6. US Department of Health and Human Services. August 28, 2013. Healthy People 2020. Available at: www.healthypeople.gov. Accessed September 13, 2013.

7. Pollak KI, Krause KM, Yarnall KS, et al. Estimated time spent on preventive services by primary care physicians. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:245.

8. US Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to Clinical Preventive Services. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; 1996.

9. Field MJ, Lohr KN, Committee to Advise the Public Health Service on Clinical Practice Guidelines, Institute of Medicine. Clinical Practice Guidelines: Directions for a New Program. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1990.

10. Yarnell K, Pollak K, Ostbye T, et al. Primary care: is there enough time for prevention? Am J Public Health. 2003;93:635-641.

11. Butler CC, Simpson SA, Hood K, et al. Training practitioners to deliver opportunistic multiple behaviour change counselling in primary care: a cluster randomized trial. BMJ. 2013;346:f1191.

12. Yonas M, Nowalk M, Zimmerman R, et al. Examining structural and clinical factors associated with implementation of standing orders for adult immunization. J Healthcare Qual. 2012;34:34-42.

13. Donahue K, Plescia M, Stafford K. Do standing orders help with chronic disease care and health maintenance in ambulatory practice? J Fam Pract. 2010;59:226-227.

14. Glasgow R, Orleans T, Wagner E. Does the chronic care model serve also as a template for improving prevention? Milbank Q. 2002;79.

15. Wagner EH. Chronic disease management: What will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Effective Clin Pract. 1998;1:2-4.

16. Barr V, Robinson S, Marin-Link B, et al. Chronic care model: an integration of concepts and strategies from population health promotion and the chronic care model. Hosp Q. 2003;7:73-83.

17. Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA. 2002;288:1775-1779.

18. Moore LG. Escaping the tyranny of the urgent by delivering planned care. Fam Pract Manage. 2006;13:37-40.

19. Tsai AC, Morton SC, Mangione CM, et al. A meta-analysis of interventions to improve care for chronic illnesses. Am J Managed Care. 2005;11:478-488.

20. Coleman K, Austin BT, Brach C, et al. Evidence on the chronic care model in the new millenium. Health Affairs. 2009;28:75-85.

21. Pearson ML, Mattke S, Shaw R, et al. Patient Self-Management Support Programs: An Evaluation. Final Contract Report. Publication No. 08-0011. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. November 2007.

22. Feder J. Restructuring care in a federally qualified health center to better meet patients’ needs. Health Affairs. 2011. Available at: http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/30/3/419.full.html. Accessed February 13, 2014.

23. Hung D, Rundall T, Tallia A, et al. Rethinking prevention in primary care: applying the chronic care model to address health risk behaviors. Milbank Q. 2007;85:69-91.

24. Lobach D, Sanders GD, Bright TJ, et al. Enabling Health Care Decisionmaking Through Clinical Decision Support and Knowledge Management. Evidence Report No. 203. Publication No. 12-E001-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. April 2012.

25. Kawamoto K, Houlihan C, Balas E, et al. Improving clinical practice using clinical decision support systems: a systemic review of trials to identify features critical to success. BMJ. 2005;330:765.

26. American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Physicians, American Osteopathic Association. Joint Principles of the Patient-Centered Medical Home. March 2007. American Academy of Family Physicians Web site. Available at: http://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/practice_management/pcmh/initiatives/PCMHJoint.pdf. Accessed May 7, 2015.

27. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The Patient-Centered Medical Home. Closing the Quality Gap: Revisiting the State of the Science: Evidence Report/Technology Assessment Executive Summary No. 208. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Web site. Available at: http://www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/391/1178/EvidReport208_CQGPatientCenteredMedicalHome_FinalReport_20120703.pdf. Accessed May 7, 2015.

28. Peikes D, Zutshi A, Genevro J, et al. Early Evidence on the Patient-Centered Medical Home. Final Report. Publication No. 12-0020-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. February 2012.

29. Liu G, Perkins A. Using a lay cancer screening navigator to increase colorectal cancer screening rates. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28:280-282.

30. Baker N, Parsons M, Donnelly S, et al. Improving colon cancer screening rates in primary care: a pilot study emphasising the role of the medical assistant. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18:355-359.

31. Holden D, Jonas D, Portersfield D. Systematic review: enhancing the use and quality of colorectal cancer screening. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:668-676.

32. Dexheimer JW, Talbot TR, Sanders DL, et al. Prompting clinicians about preventive care measures: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Am Med Inf Assoc. 2008;15:311-320.

33. Shea S, DuMouchel W, Bahamonde L. A meta-analysis of 16 randomized controlled trials to evaluate computer-based clinical reminder systems for preventive care in the ambulatory setting. J Am Med Inf Assoc. 1996;3:399-409.

34. Chaudhry B, Wang J, Wu S, et al. Systematic review: impact of health information technology on quality, efficiency, and costs of medical care. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:742-752.

35. Future of Family Medicine Leadership Committee. The future of family medicine: a collaborative project of the family medicine community. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(Suppl 1):S3-S32.

36. Porterfield D, Hinnant L, Kane H, et al. Linkages Between Clinical Practices and Community Organizations for Prevention: Final Report. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. October 2010.

37. deBeaumont Foundation, Duke Community and Family Medicine, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A Practical Playbook. Available at: https://practicalplaybook.org. Accessed March 29, 2015.

38. Physician Quality Reporting System. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/PQRS. Accessed March 29, 2015.

39. RTI International. Accountable Care Organization 2014 Program Analysis Quality Performance Standards Narrative Measure Specifications. 2014. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Feefor-Service-Payment/sharedsavingsprogram/Downloads/ACONarrativeMeasures-Specs.pdf. Accessed May 7, 2015.

40. Koh K, Sebelius K. Promoting prevention through the Affordable Care Act. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1296-1299.

41. Rosenbaum S. The patient protection and affordable care act: Implications for public health policy and practice. Public Health Rep. 2011;126:130-135.

› Avoid scheduling annual visits exclusively for preventive care. A

› Institute simple practice changes to improve the preventive services you provide, such as implementing standing orders for influenza vaccines. A

› Adopt components of the chronic care model for preventive services wherever possible—using ancillary providers to remind patients to undergo colorectal cancer screening and recommending apps that support self-management, for example. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

For well over a century, the periodic health exam has been associated with the delivery of preventive services1—a model widely accepted by physicians and patients alike. Approximately 8% of ambulatory care visits are for check-ups, and more than 20% of US residents schedule a health exam annually.2

Periodic health exams, however, do not result in optimal preventive care. Evidence suggests that important preventive services, such as dietary counseling, occur at only 8% of such visits; that just 10 seconds, on average, is devoted to smoking cessation; and that 80% of the preventive services patients receive are delivered outside of scheduled health exams.2 Because physicians and patients alike understandably prioritize acute problems, any discussion of health maintenance issues during a periodic check-up is likely to occur despite the visit’s agenda, not as part of it.3-7

Primary care physicians and practices are increasingly being held accountable for their performance on preventive measures. With that in mind, being familiar with evidence-based guidelines relating to the delivery of preventive services in ambulatory care settings, such as those developed by the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF),8 is crucial. Identifying elements of the chronic care model that can be effectively applied to preventive care—and recognizing that the reactive acute care model is ineffective for both chronic illness and preventive services—is essential, as well.

Preventive care that's evidence-based

Good practice guidelines should have the following features, according to the Institute of Medicine:9

• Validity. Application would lead to the desired health and cost outcomes.

• Reliability/reproducibility. Others using the same data/interpretation would reach the same conclusion.

• Clinical applicability. Patient populations are appropriately defined.

• Clinical flexibility. Known or generally expected exceptions are identified.

• Clarity. Guideline uses unambiguous language with precise definitions.

• Multidisciplinary process. Developed with the participation of all key stakeholders.

• Scheduled review. Periodically reviewed and revised to incorporate new evidence/changing consensus.

• Documentation. Procedures used in development are well documented.

The USPSTF guidelines are consistent with these attributes.8

Some brief interventions fail

Guidelines are useful as practice standards for establishing preventive care goals, but their existence alone does not ensure the delivery of high-quality preventive services in an office setting. One key factor is time. It is estimated that a primary care physician with an average-sized patient panel would require an additional 7.4 hours per day to achieve 100% compliance with all of the USPSTF recommendations.10

Counseling, in particular, is an intervention that may be more effective in theory than in practice. Evidence suggests that even when primary care providers are trained in preventive counseling (and many are not), many brief interventions are not effective at creating sustained behavior change or health improvement.11

Others are effective

That’s not to say that there’s little that can be done. Use of standing orders for influenza vaccination is one example of an effective and easily implemented preventive measure that requires little or no additional physician time. Yet some doctors are resistant, fearing loss of control or lawsuits. In fact, the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program specifically provides protection against vaccinerelated malpractice claims.12 A standing order for office staff to arrange a screening mammogram is another effective intervention; it has been shown to improve screening rates by as much as 30%.13

Lessons from chronic illness management

Chronic illness care and preventive care have much in common.14 Both acknowledge the need for proactive screening and counseling to bring about behavior change. In addition, both require ongoing care and follow-up, as well as depend on links to community resources. And finally, both are resource-intensive—too resource-intensive, some say, to be delivered in a cost-effective manner.

The Chronic Care Model has been proposed as a framework for improving preventive services (TABLE).15,16 Evidence suggests adopting some key components of chronic care can lead to significant gains in the delivery of preventive care, with the largest improvement seen when multiple components are used simultaneously.17-20

Self-management support. A growing body of evidence shows that self-management activities are associated with improved outcomes.21 Instituting a peer support group for pregnant women at a federally qualified health center, for example, led to a 7% absolute risk reduction in preterm births.22

Not all efforts to encourage self-management are effective, however, and evaluation is crucial to determine what works. In one large-scale trial, the use of patient reminder cards to facilitate a reduction in health risk behaviors such as tobacco use, risky drinking, unhealthy dietary patterns, and physical inactivity led to fewer health risk assessments being performed, fewer individual counseling encounters, and no change in these behaviors.23

Decision support. Clinical decision support systems, which generate patient-specific evidence-based assessments and/or recommendations that are actionable as part of the workflow at the point of care, have been found to improve care.24,25 An example of this is a prompt that reminds the physician to discuss chemoprevention with a patient at high risk for breast cancer.

Delivery system design. The patient-centered medical home (PCMH) is a well-known example of a redesign of health care delivery.26 Conversion to this model is associated with a small positive effect on preventive interventions.27 However, the persistence of a fee-for-service payment system—which does not include physician reimbursement for some of the added services incorporated into the PCMH—limits the implementation of the PCMH model.28

Many practices are improving health care delivery by using nonphysicians for various tasks related to preventive care. Care managers, for example, typically have smaller caseloads and focus on reducing unnecessary treatment for patients with high-risk conditions, such as congestive heart failure, while patient navigators generally have less clinical expertise but more knowledge of community services.

In one study, practice-initiated phone conversations with nonphysicians increased colorectal cancer screening by up to 40%.29 And in one pilot program, the use of ancillary providers led to an increase in colorectal cancer screening by as much as 123%.30 The human touch seems to be key to the success of these interventions. Passive reminders, such as videos being shown on waiting room televisions, have not proven to be effective.31

Clinical information systems. Early on, the power of electronic health records (EHRs) to improve practices’ delivery of preventive services was recognized. As early as 1995, the use of a reminder system to highlight such services during acute care visits was linked to improvements in counseling about smoking cessation and higher rates of cervical cancer screening, among other preventive measures.32,33 Overall, the use of EHRs alone has been shown to improve rates of preventive services by as much as 66%, with most practices reporting improvements of at least 20%.34

Today, EHRs that are Meaningful Use Stage 2-compliant have the tools needed to improve care. Requirements include the ability to generate patient registries of all those with a given disease and to identify patients on the registry who have not received needed care.35 To improve preventive care, registries should focus on the mitigation of risk factors, such as identifying—and contacting—patients with diabetes who are in need of, or overdue for, an annual eye exam.

Trials using the registry function, in combination with automated messaging to deliver targeted information to various patient groups (identified by the demographic information available from the EHR), are ongoing.

Community resources. Many clinicians have informal referral relationships with community organizations, such as the YMCA. Physician practices that establish links to community resources have the potential to have a large effect on unhealthy behaviors. (See “Putting theory into practice: 2 cases”.) However, a systematic review found that, while evidence to support such connections is mainly positive, research is limited and further evaluation is needed.36

The Practical Playbook (practicalplaybook.org)37 developed by the deBeaumont Foundation, Duke Department of Community and Family Medicine, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, offers concrete examples of how physician practices are linking with community resources to improve the health of the population. For example, Duke University’s “Just for Us” program provides in-home chronic illness care to 350 high-risk elderly individuals. The LATCH program connects thousands of Latino immigrants to health care services and culturally and linguistically appropriate health education classes.37

CASE 1

Dominic B, a 53-year-old patient, has scheduled a visit for a cough that has persisted for 4 weeks. The patient is a nonsmoker, is married, and has no first-degree relatives with cancer. But when you review his chart before the visit, you note that he missed his 6-month check-up for hypertension and hyperlipidemia. In addition, your electronic health record (EHR ) flags the fact that he has not undergone colorectal screening and that his immunizations are not current. Because you have standing orders in place, your medical assistant gives him a flu shot and a pamphlet providing information on colorectal cancer screening before you enter the room.

During the visit, Mr. B mentions that his father, age 82, recently had a heart attack. This event—reinforced by the postcards and phone messages he received from your office after he missed his 6-month follow-up—prompted him to reluctantly admit it was “time for a check-up.” You take the patient’s blood pressure (BP) and review his lipid panel (blood work was ordered prior to his visit) with him. He is relieved to know that he will not need to be on a statin and agrees to be screened for colorectal cancer using a sensitive stool study.

Before he leaves, the patient requests medication for erectile dysfunction—a problem he never reported before. You ask him to keep a diary and return in 2 months, and promise to discuss his erectile dysfunction at that time.

CASE 2

A review of your practice’s patient registry reveals that Gladys P, age 55, is behind on breast and cervical cancer screening. She has had only a few sporadic office visits, the last of which was for bronchitis 18 months ago. At that time, the patient’s systolic BP was 162 mm Hg. You told her you would recheck it in 6 weeks, but she failed to return for follow-up.

Ms. P smokes, but has no other chronic diseases and takes no medications. There is no record of a mammogram or Pap smear, and you don’t know whether she sees a gynecologist routinely. Your office contacts her and discovers that you are the only doctor she sees. The patient tells the medical assistant who placed the call that her car broke down but she has not had money to repair or replace it, so she has had no way to get to your office.

Your staff arranges for her to get a ride from a community volunteer group, first to the nearby hospital for a mammogram and then to your office, where you perform a Pap smear and address her elevated BP and smoking. You are rewarded for the counseling and preventive care with a letter and a bonus check from Ms. P’s insurance carrier, congratulating you on your quality improvement efforts.

Growing emphasis on quality

Systemic changes in the US health care system are occurring rapidly, with an emphasis on quality and improved outcomes. Many physicians are now required to submit data to external agencies for payment, and much of the data is grounded in preventive standards. Medicare’s Physicians Quality Reporting System requires that all Medicare providers provide data on preventive and chronic illness care. Rates of vaccination, obesity screening, and tobacco use screening are examples of preventive services that will be reported publicly on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ Physician Compare Web site.38

Physicians who work in accountable care organizations are required to meet quality standards on the delivery of certain preventive services, including breast cancer screening, colorectal cancer screening, influenza and pneumonia immunization, body mass index screening and follow-up, tobacco use screening and cessation intervention, screening for high blood pressure and followup, and screening for clinical depression and follow-up.39 As patients discover that the Affordable Care Act mandates that preventive services be covered with no cost sharing, they are likely to become more receptive to physician attempts to provide them.40,41

CORRESPONDENCE

Gerald Liu, MD, 1504 Springhill Avenue, Suite 3414, Mobile, AL 36604-3207; gliu@health.southalabama.edu

› Avoid scheduling annual visits exclusively for preventive care. A

› Institute simple practice changes to improve the preventive services you provide, such as implementing standing orders for influenza vaccines. A

› Adopt components of the chronic care model for preventive services wherever possible—using ancillary providers to remind patients to undergo colorectal cancer screening and recommending apps that support self-management, for example. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

For well over a century, the periodic health exam has been associated with the delivery of preventive services1—a model widely accepted by physicians and patients alike. Approximately 8% of ambulatory care visits are for check-ups, and more than 20% of US residents schedule a health exam annually.2

Periodic health exams, however, do not result in optimal preventive care. Evidence suggests that important preventive services, such as dietary counseling, occur at only 8% of such visits; that just 10 seconds, on average, is devoted to smoking cessation; and that 80% of the preventive services patients receive are delivered outside of scheduled health exams.2 Because physicians and patients alike understandably prioritize acute problems, any discussion of health maintenance issues during a periodic check-up is likely to occur despite the visit’s agenda, not as part of it.3-7

Primary care physicians and practices are increasingly being held accountable for their performance on preventive measures. With that in mind, being familiar with evidence-based guidelines relating to the delivery of preventive services in ambulatory care settings, such as those developed by the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF),8 is crucial. Identifying elements of the chronic care model that can be effectively applied to preventive care—and recognizing that the reactive acute care model is ineffective for both chronic illness and preventive services—is essential, as well.

Preventive care that's evidence-based

Good practice guidelines should have the following features, according to the Institute of Medicine:9

• Validity. Application would lead to the desired health and cost outcomes.

• Reliability/reproducibility. Others using the same data/interpretation would reach the same conclusion.

• Clinical applicability. Patient populations are appropriately defined.

• Clinical flexibility. Known or generally expected exceptions are identified.

• Clarity. Guideline uses unambiguous language with precise definitions.

• Multidisciplinary process. Developed with the participation of all key stakeholders.

• Scheduled review. Periodically reviewed and revised to incorporate new evidence/changing consensus.

• Documentation. Procedures used in development are well documented.

The USPSTF guidelines are consistent with these attributes.8

Some brief interventions fail

Guidelines are useful as practice standards for establishing preventive care goals, but their existence alone does not ensure the delivery of high-quality preventive services in an office setting. One key factor is time. It is estimated that a primary care physician with an average-sized patient panel would require an additional 7.4 hours per day to achieve 100% compliance with all of the USPSTF recommendations.10

Counseling, in particular, is an intervention that may be more effective in theory than in practice. Evidence suggests that even when primary care providers are trained in preventive counseling (and many are not), many brief interventions are not effective at creating sustained behavior change or health improvement.11

Others are effective

That’s not to say that there’s little that can be done. Use of standing orders for influenza vaccination is one example of an effective and easily implemented preventive measure that requires little or no additional physician time. Yet some doctors are resistant, fearing loss of control or lawsuits. In fact, the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program specifically provides protection against vaccinerelated malpractice claims.12 A standing order for office staff to arrange a screening mammogram is another effective intervention; it has been shown to improve screening rates by as much as 30%.13

Lessons from chronic illness management

Chronic illness care and preventive care have much in common.14 Both acknowledge the need for proactive screening and counseling to bring about behavior change. In addition, both require ongoing care and follow-up, as well as depend on links to community resources. And finally, both are resource-intensive—too resource-intensive, some say, to be delivered in a cost-effective manner.

The Chronic Care Model has been proposed as a framework for improving preventive services (TABLE).15,16 Evidence suggests adopting some key components of chronic care can lead to significant gains in the delivery of preventive care, with the largest improvement seen when multiple components are used simultaneously.17-20

Self-management support. A growing body of evidence shows that self-management activities are associated with improved outcomes.21 Instituting a peer support group for pregnant women at a federally qualified health center, for example, led to a 7% absolute risk reduction in preterm births.22

Not all efforts to encourage self-management are effective, however, and evaluation is crucial to determine what works. In one large-scale trial, the use of patient reminder cards to facilitate a reduction in health risk behaviors such as tobacco use, risky drinking, unhealthy dietary patterns, and physical inactivity led to fewer health risk assessments being performed, fewer individual counseling encounters, and no change in these behaviors.23

Decision support. Clinical decision support systems, which generate patient-specific evidence-based assessments and/or recommendations that are actionable as part of the workflow at the point of care, have been found to improve care.24,25 An example of this is a prompt that reminds the physician to discuss chemoprevention with a patient at high risk for breast cancer.

Delivery system design. The patient-centered medical home (PCMH) is a well-known example of a redesign of health care delivery.26 Conversion to this model is associated with a small positive effect on preventive interventions.27 However, the persistence of a fee-for-service payment system—which does not include physician reimbursement for some of the added services incorporated into the PCMH—limits the implementation of the PCMH model.28

Many practices are improving health care delivery by using nonphysicians for various tasks related to preventive care. Care managers, for example, typically have smaller caseloads and focus on reducing unnecessary treatment for patients with high-risk conditions, such as congestive heart failure, while patient navigators generally have less clinical expertise but more knowledge of community services.

In one study, practice-initiated phone conversations with nonphysicians increased colorectal cancer screening by up to 40%.29 And in one pilot program, the use of ancillary providers led to an increase in colorectal cancer screening by as much as 123%.30 The human touch seems to be key to the success of these interventions. Passive reminders, such as videos being shown on waiting room televisions, have not proven to be effective.31

Clinical information systems. Early on, the power of electronic health records (EHRs) to improve practices’ delivery of preventive services was recognized. As early as 1995, the use of a reminder system to highlight such services during acute care visits was linked to improvements in counseling about smoking cessation and higher rates of cervical cancer screening, among other preventive measures.32,33 Overall, the use of EHRs alone has been shown to improve rates of preventive services by as much as 66%, with most practices reporting improvements of at least 20%.34

Today, EHRs that are Meaningful Use Stage 2-compliant have the tools needed to improve care. Requirements include the ability to generate patient registries of all those with a given disease and to identify patients on the registry who have not received needed care.35 To improve preventive care, registries should focus on the mitigation of risk factors, such as identifying—and contacting—patients with diabetes who are in need of, or overdue for, an annual eye exam.

Trials using the registry function, in combination with automated messaging to deliver targeted information to various patient groups (identified by the demographic information available from the EHR), are ongoing.

Community resources. Many clinicians have informal referral relationships with community organizations, such as the YMCA. Physician practices that establish links to community resources have the potential to have a large effect on unhealthy behaviors. (See “Putting theory into practice: 2 cases”.) However, a systematic review found that, while evidence to support such connections is mainly positive, research is limited and further evaluation is needed.36

The Practical Playbook (practicalplaybook.org)37 developed by the deBeaumont Foundation, Duke Department of Community and Family Medicine, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, offers concrete examples of how physician practices are linking with community resources to improve the health of the population. For example, Duke University’s “Just for Us” program provides in-home chronic illness care to 350 high-risk elderly individuals. The LATCH program connects thousands of Latino immigrants to health care services and culturally and linguistically appropriate health education classes.37

CASE 1

Dominic B, a 53-year-old patient, has scheduled a visit for a cough that has persisted for 4 weeks. The patient is a nonsmoker, is married, and has no first-degree relatives with cancer. But when you review his chart before the visit, you note that he missed his 6-month check-up for hypertension and hyperlipidemia. In addition, your electronic health record (EHR ) flags the fact that he has not undergone colorectal screening and that his immunizations are not current. Because you have standing orders in place, your medical assistant gives him a flu shot and a pamphlet providing information on colorectal cancer screening before you enter the room.

During the visit, Mr. B mentions that his father, age 82, recently had a heart attack. This event—reinforced by the postcards and phone messages he received from your office after he missed his 6-month follow-up—prompted him to reluctantly admit it was “time for a check-up.” You take the patient’s blood pressure (BP) and review his lipid panel (blood work was ordered prior to his visit) with him. He is relieved to know that he will not need to be on a statin and agrees to be screened for colorectal cancer using a sensitive stool study.

Before he leaves, the patient requests medication for erectile dysfunction—a problem he never reported before. You ask him to keep a diary and return in 2 months, and promise to discuss his erectile dysfunction at that time.

CASE 2

A review of your practice’s patient registry reveals that Gladys P, age 55, is behind on breast and cervical cancer screening. She has had only a few sporadic office visits, the last of which was for bronchitis 18 months ago. At that time, the patient’s systolic BP was 162 mm Hg. You told her you would recheck it in 6 weeks, but she failed to return for follow-up.

Ms. P smokes, but has no other chronic diseases and takes no medications. There is no record of a mammogram or Pap smear, and you don’t know whether she sees a gynecologist routinely. Your office contacts her and discovers that you are the only doctor she sees. The patient tells the medical assistant who placed the call that her car broke down but she has not had money to repair or replace it, so she has had no way to get to your office.

Your staff arranges for her to get a ride from a community volunteer group, first to the nearby hospital for a mammogram and then to your office, where you perform a Pap smear and address her elevated BP and smoking. You are rewarded for the counseling and preventive care with a letter and a bonus check from Ms. P’s insurance carrier, congratulating you on your quality improvement efforts.

Growing emphasis on quality

Systemic changes in the US health care system are occurring rapidly, with an emphasis on quality and improved outcomes. Many physicians are now required to submit data to external agencies for payment, and much of the data is grounded in preventive standards. Medicare’s Physicians Quality Reporting System requires that all Medicare providers provide data on preventive and chronic illness care. Rates of vaccination, obesity screening, and tobacco use screening are examples of preventive services that will be reported publicly on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ Physician Compare Web site.38

Physicians who work in accountable care organizations are required to meet quality standards on the delivery of certain preventive services, including breast cancer screening, colorectal cancer screening, influenza and pneumonia immunization, body mass index screening and follow-up, tobacco use screening and cessation intervention, screening for high blood pressure and followup, and screening for clinical depression and follow-up.39 As patients discover that the Affordable Care Act mandates that preventive services be covered with no cost sharing, they are likely to become more receptive to physician attempts to provide them.40,41

CORRESPONDENCE

Gerald Liu, MD, 1504 Springhill Avenue, Suite 3414, Mobile, AL 36604-3207; gliu@health.southalabama.edu

1. Han P. Historical changes in the objectives of the periodic health exam. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:910-917.

2. Mehrota A, Zaslavsky A, Anyanian J. Preventive health examinations and preventive gynecologic examinations in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1876-1883.

3. Jean CR, Stange KC, Nutting PA. Competing demands of primary care: a model for the delivery of clinical preventive services. J Fam Pract. 1994;38:166-171.

4. McGinnis JM, Foege WH. The immediate versus the important. JAMA. 2004;291:1263-1264.

5. Crabtree BF, Miller WL, Tallia AF, et al. Delivery of clinical preventive services in family medicine offices. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3:430-435.

6. US Department of Health and Human Services. August 28, 2013. Healthy People 2020. Available at: www.healthypeople.gov. Accessed September 13, 2013.

7. Pollak KI, Krause KM, Yarnall KS, et al. Estimated time spent on preventive services by primary care physicians. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:245.

8. US Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to Clinical Preventive Services. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; 1996.

9. Field MJ, Lohr KN, Committee to Advise the Public Health Service on Clinical Practice Guidelines, Institute of Medicine. Clinical Practice Guidelines: Directions for a New Program. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1990.

10. Yarnell K, Pollak K, Ostbye T, et al. Primary care: is there enough time for prevention? Am J Public Health. 2003;93:635-641.

11. Butler CC, Simpson SA, Hood K, et al. Training practitioners to deliver opportunistic multiple behaviour change counselling in primary care: a cluster randomized trial. BMJ. 2013;346:f1191.

12. Yonas M, Nowalk M, Zimmerman R, et al. Examining structural and clinical factors associated with implementation of standing orders for adult immunization. J Healthcare Qual. 2012;34:34-42.

13. Donahue K, Plescia M, Stafford K. Do standing orders help with chronic disease care and health maintenance in ambulatory practice? J Fam Pract. 2010;59:226-227.

14. Glasgow R, Orleans T, Wagner E. Does the chronic care model serve also as a template for improving prevention? Milbank Q. 2002;79.

15. Wagner EH. Chronic disease management: What will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Effective Clin Pract. 1998;1:2-4.

16. Barr V, Robinson S, Marin-Link B, et al. Chronic care model: an integration of concepts and strategies from population health promotion and the chronic care model. Hosp Q. 2003;7:73-83.

17. Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA. 2002;288:1775-1779.

18. Moore LG. Escaping the tyranny of the urgent by delivering planned care. Fam Pract Manage. 2006;13:37-40.

19. Tsai AC, Morton SC, Mangione CM, et al. A meta-analysis of interventions to improve care for chronic illnesses. Am J Managed Care. 2005;11:478-488.

20. Coleman K, Austin BT, Brach C, et al. Evidence on the chronic care model in the new millenium. Health Affairs. 2009;28:75-85.

21. Pearson ML, Mattke S, Shaw R, et al. Patient Self-Management Support Programs: An Evaluation. Final Contract Report. Publication No. 08-0011. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. November 2007.

22. Feder J. Restructuring care in a federally qualified health center to better meet patients’ needs. Health Affairs. 2011. Available at: http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/30/3/419.full.html. Accessed February 13, 2014.

23. Hung D, Rundall T, Tallia A, et al. Rethinking prevention in primary care: applying the chronic care model to address health risk behaviors. Milbank Q. 2007;85:69-91.

24. Lobach D, Sanders GD, Bright TJ, et al. Enabling Health Care Decisionmaking Through Clinical Decision Support and Knowledge Management. Evidence Report No. 203. Publication No. 12-E001-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. April 2012.

25. Kawamoto K, Houlihan C, Balas E, et al. Improving clinical practice using clinical decision support systems: a systemic review of trials to identify features critical to success. BMJ. 2005;330:765.

26. American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Physicians, American Osteopathic Association. Joint Principles of the Patient-Centered Medical Home. March 2007. American Academy of Family Physicians Web site. Available at: http://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/practice_management/pcmh/initiatives/PCMHJoint.pdf. Accessed May 7, 2015.

27. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The Patient-Centered Medical Home. Closing the Quality Gap: Revisiting the State of the Science: Evidence Report/Technology Assessment Executive Summary No. 208. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Web site. Available at: http://www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/391/1178/EvidReport208_CQGPatientCenteredMedicalHome_FinalReport_20120703.pdf. Accessed May 7, 2015.

28. Peikes D, Zutshi A, Genevro J, et al. Early Evidence on the Patient-Centered Medical Home. Final Report. Publication No. 12-0020-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. February 2012.

29. Liu G, Perkins A. Using a lay cancer screening navigator to increase colorectal cancer screening rates. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28:280-282.

30. Baker N, Parsons M, Donnelly S, et al. Improving colon cancer screening rates in primary care: a pilot study emphasising the role of the medical assistant. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18:355-359.

31. Holden D, Jonas D, Portersfield D. Systematic review: enhancing the use and quality of colorectal cancer screening. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:668-676.

32. Dexheimer JW, Talbot TR, Sanders DL, et al. Prompting clinicians about preventive care measures: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Am Med Inf Assoc. 2008;15:311-320.

33. Shea S, DuMouchel W, Bahamonde L. A meta-analysis of 16 randomized controlled trials to evaluate computer-based clinical reminder systems for preventive care in the ambulatory setting. J Am Med Inf Assoc. 1996;3:399-409.

34. Chaudhry B, Wang J, Wu S, et al. Systematic review: impact of health information technology on quality, efficiency, and costs of medical care. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:742-752.

35. Future of Family Medicine Leadership Committee. The future of family medicine: a collaborative project of the family medicine community. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(Suppl 1):S3-S32.

36. Porterfield D, Hinnant L, Kane H, et al. Linkages Between Clinical Practices and Community Organizations for Prevention: Final Report. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. October 2010.

37. deBeaumont Foundation, Duke Community and Family Medicine, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A Practical Playbook. Available at: https://practicalplaybook.org. Accessed March 29, 2015.

38. Physician Quality Reporting System. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/PQRS. Accessed March 29, 2015.

39. RTI International. Accountable Care Organization 2014 Program Analysis Quality Performance Standards Narrative Measure Specifications. 2014. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Feefor-Service-Payment/sharedsavingsprogram/Downloads/ACONarrativeMeasures-Specs.pdf. Accessed May 7, 2015.

40. Koh K, Sebelius K. Promoting prevention through the Affordable Care Act. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1296-1299.

41. Rosenbaum S. The patient protection and affordable care act: Implications for public health policy and practice. Public Health Rep. 2011;126:130-135.

1. Han P. Historical changes in the objectives of the periodic health exam. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:910-917.

2. Mehrota A, Zaslavsky A, Anyanian J. Preventive health examinations and preventive gynecologic examinations in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1876-1883.

3. Jean CR, Stange KC, Nutting PA. Competing demands of primary care: a model for the delivery of clinical preventive services. J Fam Pract. 1994;38:166-171.

4. McGinnis JM, Foege WH. The immediate versus the important. JAMA. 2004;291:1263-1264.

5. Crabtree BF, Miller WL, Tallia AF, et al. Delivery of clinical preventive services in family medicine offices. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3:430-435.

6. US Department of Health and Human Services. August 28, 2013. Healthy People 2020. Available at: www.healthypeople.gov. Accessed September 13, 2013.

7. Pollak KI, Krause KM, Yarnall KS, et al. Estimated time spent on preventive services by primary care physicians. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:245.

8. US Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to Clinical Preventive Services. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; 1996.

9. Field MJ, Lohr KN, Committee to Advise the Public Health Service on Clinical Practice Guidelines, Institute of Medicine. Clinical Practice Guidelines: Directions for a New Program. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1990.

10. Yarnell K, Pollak K, Ostbye T, et al. Primary care: is there enough time for prevention? Am J Public Health. 2003;93:635-641.

11. Butler CC, Simpson SA, Hood K, et al. Training practitioners to deliver opportunistic multiple behaviour change counselling in primary care: a cluster randomized trial. BMJ. 2013;346:f1191.

12. Yonas M, Nowalk M, Zimmerman R, et al. Examining structural and clinical factors associated with implementation of standing orders for adult immunization. J Healthcare Qual. 2012;34:34-42.

13. Donahue K, Plescia M, Stafford K. Do standing orders help with chronic disease care and health maintenance in ambulatory practice? J Fam Pract. 2010;59:226-227.

14. Glasgow R, Orleans T, Wagner E. Does the chronic care model serve also as a template for improving prevention? Milbank Q. 2002;79.

15. Wagner EH. Chronic disease management: What will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Effective Clin Pract. 1998;1:2-4.

16. Barr V, Robinson S, Marin-Link B, et al. Chronic care model: an integration of concepts and strategies from population health promotion and the chronic care model. Hosp Q. 2003;7:73-83.

17. Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA. 2002;288:1775-1779.

18. Moore LG. Escaping the tyranny of the urgent by delivering planned care. Fam Pract Manage. 2006;13:37-40.

19. Tsai AC, Morton SC, Mangione CM, et al. A meta-analysis of interventions to improve care for chronic illnesses. Am J Managed Care. 2005;11:478-488.

20. Coleman K, Austin BT, Brach C, et al. Evidence on the chronic care model in the new millenium. Health Affairs. 2009;28:75-85.

21. Pearson ML, Mattke S, Shaw R, et al. Patient Self-Management Support Programs: An Evaluation. Final Contract Report. Publication No. 08-0011. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. November 2007.

22. Feder J. Restructuring care in a federally qualified health center to better meet patients’ needs. Health Affairs. 2011. Available at: http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/30/3/419.full.html. Accessed February 13, 2014.

23. Hung D, Rundall T, Tallia A, et al. Rethinking prevention in primary care: applying the chronic care model to address health risk behaviors. Milbank Q. 2007;85:69-91.

24. Lobach D, Sanders GD, Bright TJ, et al. Enabling Health Care Decisionmaking Through Clinical Decision Support and Knowledge Management. Evidence Report No. 203. Publication No. 12-E001-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. April 2012.

25. Kawamoto K, Houlihan C, Balas E, et al. Improving clinical practice using clinical decision support systems: a systemic review of trials to identify features critical to success. BMJ. 2005;330:765.

26. American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Physicians, American Osteopathic Association. Joint Principles of the Patient-Centered Medical Home. March 2007. American Academy of Family Physicians Web site. Available at: http://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/practice_management/pcmh/initiatives/PCMHJoint.pdf. Accessed May 7, 2015.

27. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The Patient-Centered Medical Home. Closing the Quality Gap: Revisiting the State of the Science: Evidence Report/Technology Assessment Executive Summary No. 208. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Web site. Available at: http://www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/391/1178/EvidReport208_CQGPatientCenteredMedicalHome_FinalReport_20120703.pdf. Accessed May 7, 2015.

28. Peikes D, Zutshi A, Genevro J, et al. Early Evidence on the Patient-Centered Medical Home. Final Report. Publication No. 12-0020-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. February 2012.

29. Liu G, Perkins A. Using a lay cancer screening navigator to increase colorectal cancer screening rates. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28:280-282.

30. Baker N, Parsons M, Donnelly S, et al. Improving colon cancer screening rates in primary care: a pilot study emphasising the role of the medical assistant. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18:355-359.

31. Holden D, Jonas D, Portersfield D. Systematic review: enhancing the use and quality of colorectal cancer screening. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:668-676.

32. Dexheimer JW, Talbot TR, Sanders DL, et al. Prompting clinicians about preventive care measures: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Am Med Inf Assoc. 2008;15:311-320.

33. Shea S, DuMouchel W, Bahamonde L. A meta-analysis of 16 randomized controlled trials to evaluate computer-based clinical reminder systems for preventive care in the ambulatory setting. J Am Med Inf Assoc. 1996;3:399-409.

34. Chaudhry B, Wang J, Wu S, et al. Systematic review: impact of health information technology on quality, efficiency, and costs of medical care. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:742-752.

35. Future of Family Medicine Leadership Committee. The future of family medicine: a collaborative project of the family medicine community. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(Suppl 1):S3-S32.

36. Porterfield D, Hinnant L, Kane H, et al. Linkages Between Clinical Practices and Community Organizations for Prevention: Final Report. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. October 2010.

37. deBeaumont Foundation, Duke Community and Family Medicine, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A Practical Playbook. Available at: https://practicalplaybook.org. Accessed March 29, 2015.

38. Physician Quality Reporting System. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/PQRS. Accessed March 29, 2015.

39. RTI International. Accountable Care Organization 2014 Program Analysis Quality Performance Standards Narrative Measure Specifications. 2014. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Feefor-Service-Payment/sharedsavingsprogram/Downloads/ACONarrativeMeasures-Specs.pdf. Accessed May 7, 2015.

40. Koh K, Sebelius K. Promoting prevention through the Affordable Care Act. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1296-1299.

41. Rosenbaum S. The patient protection and affordable care act: Implications for public health policy and practice. Public Health Rep. 2011;126:130-135.