User login

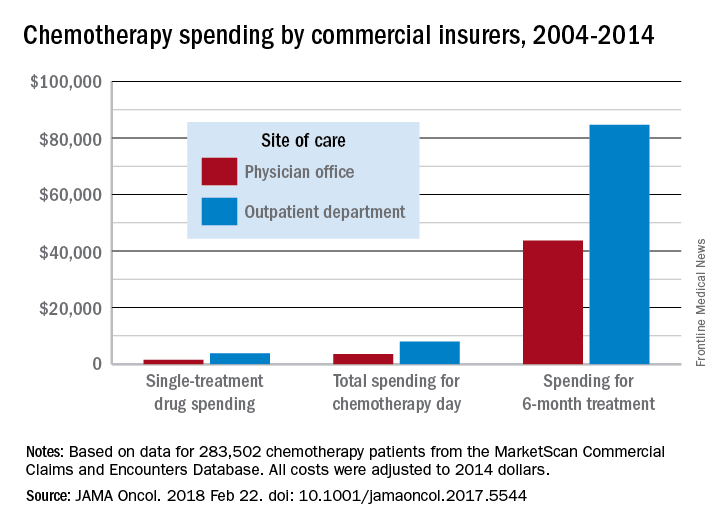

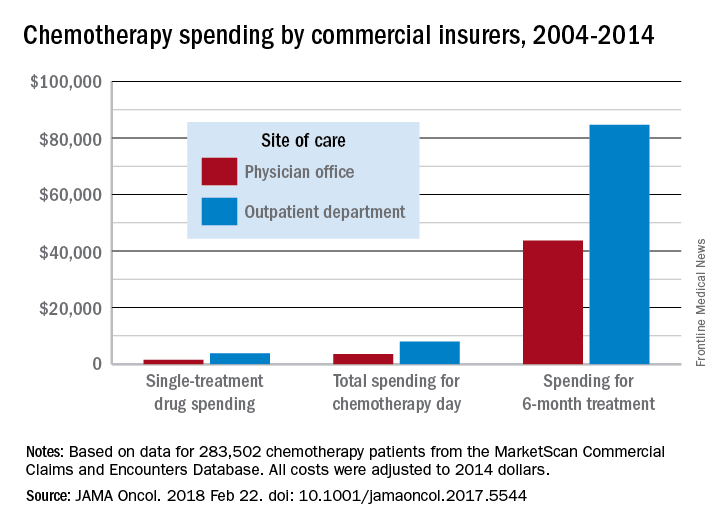

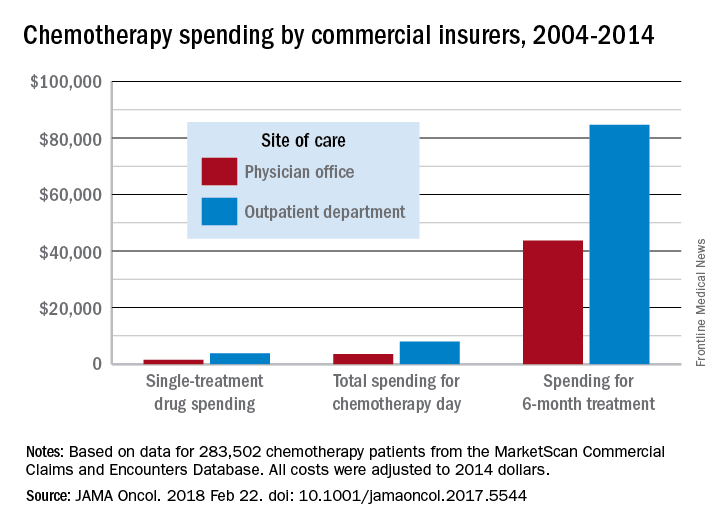

Commercial insurers are spending nearly twice as much on chemotherapy administered in hospital outpatient departments as they are for therapy administered in a physician’s office, according to an analysis of a decade of claims data.

Commercial insurance data from 283,502 patients who initiated treatment with infused chemotherapy and remained enrolled continuously for 6 months, without receiving infused chemotherapy in the preceding 6 months, revealed that spending at the drug level was “significantly lower in offices vs. in HOPDs [hospital outpatient departments],” Aaron Winn, PhD, of the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, and his colleagues wrote in a research letter published Feb. 22 in JAMA Oncology.

During the review period from Jan. 1, 2004 through Dec. 31, 2014, the rate of commercially-insured patients receiving chemotherapy in HOPDs grew from 6% in 2004 to 43% in 2014. The spending data was adjusted for various factors, including, sex, comorbidity, year of diagnosis, drug administered, and location.

“Shifting the provision of infused chemotherapy from physician offices to HOPDs is increasing and is associated with increased spending for chemotherapy services,” the researchers wrote. “Potential targets for reduction of excess spending can come from private insurers following Medicaid’s lead, which has started to equalize payments across sites of care.”

“I was a little surprised that the site location was converging on 50-50 across the country,” Dr. Carole Miller, director of the Cancer Institute at St. Agnes Hospital, Baltimore, said in an interview, adding that the spending figures were not a surprise.

Dr. Miller noted that another thing the claims data does not capture are the kinds of additional services that patients are receiving in their respective sites of care, which could also account for the difference in total reimbursement. For example, hospital-based cancer centers may offer more social support service given that the patients tend to be older and may have more social service needs as well as more uncompensated care.

David Henry, MD, an oncologist who practices in a community setting that is part of the University of Pennsylvania hospital system, said the data fits with his experience. “Is the care better? I don’t think so. Is the overhead bigger? Sure.”

Part of what makes the care better in the community setting is the patient experience, said Dr. Henry, who serves as editor-in-chief of the Journal of Community and Supportive Oncology, which is published by this news organization.

The office setting can often boast a streamlined experience, he added. In the hospital, the administrative elements and travel across the hospital campus can make an infusion a day-long task, versus going to a community office setting where the total infusion process, including the administrative aspects, can be handled in a few hours.

Dr. Henry acknowledged that the hospital setting does have an advantage in terms of depth of services, including specialists to deal with a variety of tumors.

Dr. Henry noted that the current analysis does not address the shift to paying for value and the move away from fee-for-service payment. Speaking about whether Medicare’s Quality Payment Program can level the playing field in some ways between the two settings of care, he said “the idea has potential” but the success will be determined by how it is implemented.

This article was updated on 2/22/18.

gtwachtman@frontlinemedcom.com

SOURCE: Winn A et al., JAMA Oncol. 2018 Feb 22. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.5544.

Commercial insurers are spending nearly twice as much on chemotherapy administered in hospital outpatient departments as they are for therapy administered in a physician’s office, according to an analysis of a decade of claims data.

Commercial insurance data from 283,502 patients who initiated treatment with infused chemotherapy and remained enrolled continuously for 6 months, without receiving infused chemotherapy in the preceding 6 months, revealed that spending at the drug level was “significantly lower in offices vs. in HOPDs [hospital outpatient departments],” Aaron Winn, PhD, of the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, and his colleagues wrote in a research letter published Feb. 22 in JAMA Oncology.

During the review period from Jan. 1, 2004 through Dec. 31, 2014, the rate of commercially-insured patients receiving chemotherapy in HOPDs grew from 6% in 2004 to 43% in 2014. The spending data was adjusted for various factors, including, sex, comorbidity, year of diagnosis, drug administered, and location.

“Shifting the provision of infused chemotherapy from physician offices to HOPDs is increasing and is associated with increased spending for chemotherapy services,” the researchers wrote. “Potential targets for reduction of excess spending can come from private insurers following Medicaid’s lead, which has started to equalize payments across sites of care.”

“I was a little surprised that the site location was converging on 50-50 across the country,” Dr. Carole Miller, director of the Cancer Institute at St. Agnes Hospital, Baltimore, said in an interview, adding that the spending figures were not a surprise.

Dr. Miller noted that another thing the claims data does not capture are the kinds of additional services that patients are receiving in their respective sites of care, which could also account for the difference in total reimbursement. For example, hospital-based cancer centers may offer more social support service given that the patients tend to be older and may have more social service needs as well as more uncompensated care.

David Henry, MD, an oncologist who practices in a community setting that is part of the University of Pennsylvania hospital system, said the data fits with his experience. “Is the care better? I don’t think so. Is the overhead bigger? Sure.”

Part of what makes the care better in the community setting is the patient experience, said Dr. Henry, who serves as editor-in-chief of the Journal of Community and Supportive Oncology, which is published by this news organization.

The office setting can often boast a streamlined experience, he added. In the hospital, the administrative elements and travel across the hospital campus can make an infusion a day-long task, versus going to a community office setting where the total infusion process, including the administrative aspects, can be handled in a few hours.

Dr. Henry acknowledged that the hospital setting does have an advantage in terms of depth of services, including specialists to deal with a variety of tumors.

Dr. Henry noted that the current analysis does not address the shift to paying for value and the move away from fee-for-service payment. Speaking about whether Medicare’s Quality Payment Program can level the playing field in some ways between the two settings of care, he said “the idea has potential” but the success will be determined by how it is implemented.

This article was updated on 2/22/18.

gtwachtman@frontlinemedcom.com

SOURCE: Winn A et al., JAMA Oncol. 2018 Feb 22. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.5544.

Commercial insurers are spending nearly twice as much on chemotherapy administered in hospital outpatient departments as they are for therapy administered in a physician’s office, according to an analysis of a decade of claims data.

Commercial insurance data from 283,502 patients who initiated treatment with infused chemotherapy and remained enrolled continuously for 6 months, without receiving infused chemotherapy in the preceding 6 months, revealed that spending at the drug level was “significantly lower in offices vs. in HOPDs [hospital outpatient departments],” Aaron Winn, PhD, of the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, and his colleagues wrote in a research letter published Feb. 22 in JAMA Oncology.

During the review period from Jan. 1, 2004 through Dec. 31, 2014, the rate of commercially-insured patients receiving chemotherapy in HOPDs grew from 6% in 2004 to 43% in 2014. The spending data was adjusted for various factors, including, sex, comorbidity, year of diagnosis, drug administered, and location.

“Shifting the provision of infused chemotherapy from physician offices to HOPDs is increasing and is associated with increased spending for chemotherapy services,” the researchers wrote. “Potential targets for reduction of excess spending can come from private insurers following Medicaid’s lead, which has started to equalize payments across sites of care.”

“I was a little surprised that the site location was converging on 50-50 across the country,” Dr. Carole Miller, director of the Cancer Institute at St. Agnes Hospital, Baltimore, said in an interview, adding that the spending figures were not a surprise.

Dr. Miller noted that another thing the claims data does not capture are the kinds of additional services that patients are receiving in their respective sites of care, which could also account for the difference in total reimbursement. For example, hospital-based cancer centers may offer more social support service given that the patients tend to be older and may have more social service needs as well as more uncompensated care.

David Henry, MD, an oncologist who practices in a community setting that is part of the University of Pennsylvania hospital system, said the data fits with his experience. “Is the care better? I don’t think so. Is the overhead bigger? Sure.”

Part of what makes the care better in the community setting is the patient experience, said Dr. Henry, who serves as editor-in-chief of the Journal of Community and Supportive Oncology, which is published by this news organization.

The office setting can often boast a streamlined experience, he added. In the hospital, the administrative elements and travel across the hospital campus can make an infusion a day-long task, versus going to a community office setting where the total infusion process, including the administrative aspects, can be handled in a few hours.

Dr. Henry acknowledged that the hospital setting does have an advantage in terms of depth of services, including specialists to deal with a variety of tumors.

Dr. Henry noted that the current analysis does not address the shift to paying for value and the move away from fee-for-service payment. Speaking about whether Medicare’s Quality Payment Program can level the playing field in some ways between the two settings of care, he said “the idea has potential” but the success will be determined by how it is implemented.

This article was updated on 2/22/18.

gtwachtman@frontlinemedcom.com

SOURCE: Winn A et al., JAMA Oncol. 2018 Feb 22. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.5544.

FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Total reimbursement during the 6-month treatment episode was lower in offices ($43,700) than in hospital outpatient departments ($84,660).

Study details: An examination of claims data from 283,502 patients who initiated treatment with infused chemotherapy and remained enrolled continuously for 6 months between Jan. 1, 2004, and Dec. 31, 2014.

Disclosures: The researchers reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Source: Winn A et al., JAMA Oncol. 2018 Feb 22. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.5544.