User login

Personal protective equipment (PPE) is an important component in limiting transmission of SARS-CoV-2. The World Health Organization and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued guidelines for appropriate PPE use, but recommendations for head and shoe coverings are lacking. In this article, we analyze the literature on pathogen transmission via hair and shoes and make evidence-based recommendations for PPE selection during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Pathogens on Shoes and Hair

Hair and shoes may act as vehicles for pathogen transmission. In a study that simulated contamination of uncovered skin in health care workers after intubating manikins in respiratory distress, 8 (100%) had fluorescent markers on the hair, 6 (75%) on the neck, and 4 (50%) on the shoes.1 In another study of postsurgical operating room (OR) surfaces (517 cultures), uncovered shoe tops and reusable hair coverings had 10-times more bacterial colony–forming units compared to other surfaces. On average, disposable shoe covers/head coverings had less than one-third bacterial colony–forming units compared with uncovered shoes/reusable hair coverings.2

Hair characteristics and coverings may affect pathogen transmission. Exposed hair may collect bacteria, as Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis attach to both scalp and facial hair. In one case, β-hemolytic streptococci cultured from the scalp of a perioperative nurse was linked to postsurgical infections in 20 patients.3 Hair coverings include bouffant caps and skullcaps. The bouffant cap is similar to a shower cap; it is relatively loose and secured around the head with elastic. The skullcap, or scrub cap, is tighter but leaves the neck nape and sideburns exposed. In a study comparing disposable bouffant caps, disposable skullcaps, and home-laundered cloth skullcaps worn by 2 teams of 5 surgeons, the disposable bouffant caps had the highest permeability, penetration, and microbial shed of airborne particles.4

Physicians’ shoes may act as fomites for transmission of pathogens to patients. In a study of 41 physicians and nurses in an acute care hospital, shoe soles were positive for at least one pathogen in 12 (29.3%) participants; methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus was most common. Additionally, 98% (49/50) of shoes worn outdoors showed positive bacterial cultures compared to 56% (28/50) of shoes reserved for the OR only.5 In a study examining ventilation effects on airborne pathogens in the OR, 15% of OR airborne bacteria originated from OR floors, and higher bacterial counts correlated with a higher number of steps in the OR.2 In another study designed to evaluate SARS-CoV-2 distribution on hospital floors, 70% (7/10) of quantitative polymerase chain reaction assays performed on floor samples from intensive care units were positive. In addition, 100% (3/3) of swabs taken from hospital pharmacy floors with no COVID-19 patients were positive for SARS-CoV-2, meaning contaminated shoes likely served as vectors.6 Middle East respiratory syndrome, SARS-CoV-2, and influenza viruses may survive on porous and nonporous materials for hours to days.7Enterococcus, Candida, and Aspergillus may survive on textiles for up to 90 days.3

Recommendations for Hair and Shoe Coverings

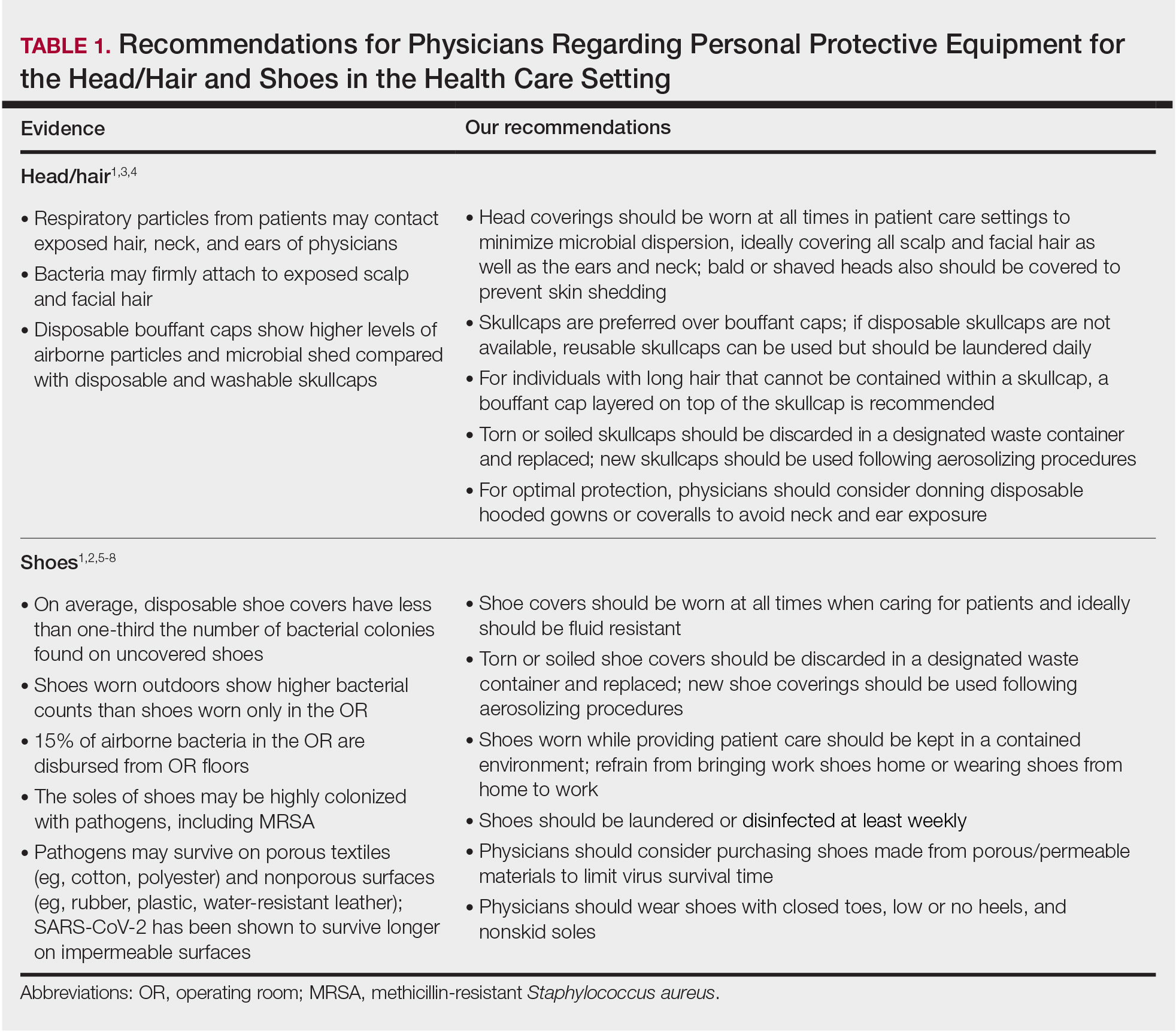

We recommend that physicians utilize disposable skullcaps to cover the hair and consider a hooded gown or coverall for neck/ear coverage. We also recommend that physicians designate shoes that remain in the workplace and can be easily washed or disinfected at least weekly; physicians may choose to wash or disinfect shoes more often if they frequently are performing procedures that generate aerosols. Additionally, physicians should always wear shoe coverings when caring for patients (Table 1).

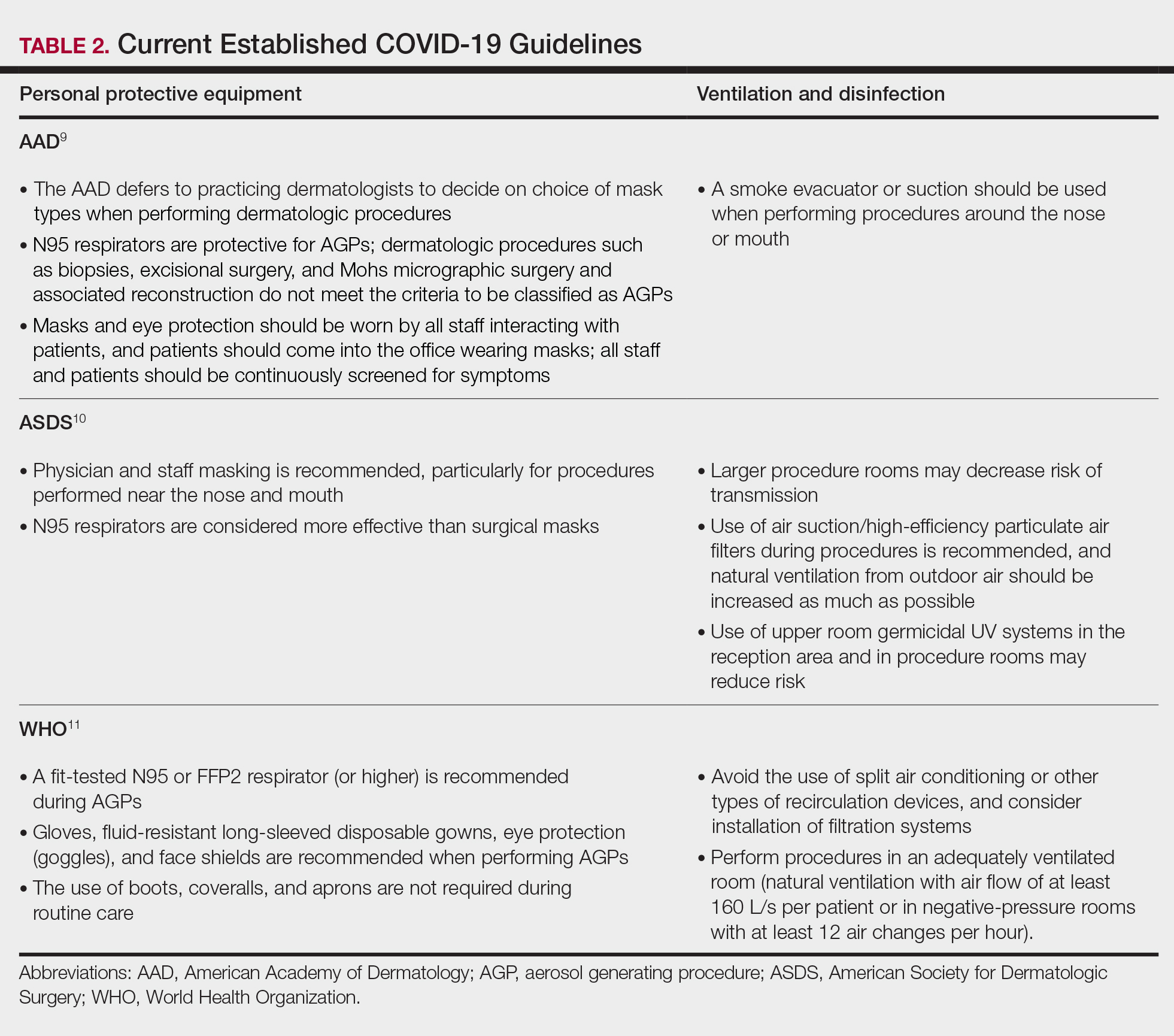

Our hair and shoe covering recommendations may serve to protect dermatologists when caring for patients. These protocols may be particularly important for dermatologists performing high-risk procedures, including facial surgery, intraoral/intranasal procedures, and treatment with ablative lasers and facial injectables, especially when the patient is unmasked. These recommendations may limit viral transmission to dermatologists and also protect individuals living in their households. Additional established guidelines by the American Academy of Dermatology, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, and World Health Organization are listed in Table 2.8-10

Current PPE recommendations that do not include hair and shoe coverings may be inadequate for limiting SARS-CoV-2 exposure between and among physicians and patients. Adherence to head covering and shoe recommendations may aid in reducing unwanted SARS-CoV-2 transmission in the health care setting, even as the pandemic continues.

- Feldman O, Meir M, Shavit D, et al. Exposure to a surrogate measure of contamination from simulated patients by emergency department personnel wearing personal protective equipment. JAMA. 2020;323:2091-2093. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.6633

- Alexander JW, Van Sweringen H, Vanoss K, et al. Surveillance of bacterial colonization in operating rooms. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2013;14:345-351. doi:10.1089/sur.2012.134

- Blanchard J. Clinical issues—August 2010. AORN Journal. 2010;92:228-232. doi:10.1016/j.aorn.2010.06.001

- Markel TA, Gormley T, Greeley D, et al. Hats off: a study of different operating room headgear assessed by environmental quality indicators. J Am Coll Surg. 2017;225:573-581. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.08.014

- Kanwar A, Thakur M, Wazzan M, et al. Clothing and shoes of personnel as potential vectors for transfer of health care-associated pathogens to the community. Am J Infect Control. 2019;47:577-579. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2019.01.028

- Guo ZD, Wang ZY, Zhang SF, et al. Aerosol and surface distribution of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in hospital wards, Wuhan, China, 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1583-1591. doi:10.3201/eid2607.200885

- Otter JA, Donskey C, Yezli S, et al. Transmission of SARS and MERS coronaviruses and influenza virus in healthcare settings: the possible role of dry surface contamination. J Hosp Infect. 2016;92:235-250. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2015.08.027

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Science Brief: SARS-CoV-2 and Surface (Fomite) Transmission for Indoor Community Environments. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/more/science-and-research/surface-transmission.html#ref10

- American Academy of Dermatology. Clinical guidance for COVID-19. Accessed March 15, 2021. https://www.aad.org/member/practice/coronavirus/clinical-guidance

- Narla S, Alam M, Ozog DM, et al. American Society of Dermatologic Surgery Association (ASDSA) and American Society for Laser Medicine & Surgery (ASLMS) guidance for cosmetic dermatology practices during COVID-19. Updated January 11, 2021. Accessed March 15, 2021. https://www.asds.net/Portals/0/PDF/asdsa/asdsa-aslms-cosmetic-reopening-guidance.pdf

- World Health Organization. Country & technical guidance—coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Accessed March 15, 2021. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance-publications

Personal protective equipment (PPE) is an important component in limiting transmission of SARS-CoV-2. The World Health Organization and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued guidelines for appropriate PPE use, but recommendations for head and shoe coverings are lacking. In this article, we analyze the literature on pathogen transmission via hair and shoes and make evidence-based recommendations for PPE selection during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Pathogens on Shoes and Hair

Hair and shoes may act as vehicles for pathogen transmission. In a study that simulated contamination of uncovered skin in health care workers after intubating manikins in respiratory distress, 8 (100%) had fluorescent markers on the hair, 6 (75%) on the neck, and 4 (50%) on the shoes.1 In another study of postsurgical operating room (OR) surfaces (517 cultures), uncovered shoe tops and reusable hair coverings had 10-times more bacterial colony–forming units compared to other surfaces. On average, disposable shoe covers/head coverings had less than one-third bacterial colony–forming units compared with uncovered shoes/reusable hair coverings.2

Hair characteristics and coverings may affect pathogen transmission. Exposed hair may collect bacteria, as Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis attach to both scalp and facial hair. In one case, β-hemolytic streptococci cultured from the scalp of a perioperative nurse was linked to postsurgical infections in 20 patients.3 Hair coverings include bouffant caps and skullcaps. The bouffant cap is similar to a shower cap; it is relatively loose and secured around the head with elastic. The skullcap, or scrub cap, is tighter but leaves the neck nape and sideburns exposed. In a study comparing disposable bouffant caps, disposable skullcaps, and home-laundered cloth skullcaps worn by 2 teams of 5 surgeons, the disposable bouffant caps had the highest permeability, penetration, and microbial shed of airborne particles.4

Physicians’ shoes may act as fomites for transmission of pathogens to patients. In a study of 41 physicians and nurses in an acute care hospital, shoe soles were positive for at least one pathogen in 12 (29.3%) participants; methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus was most common. Additionally, 98% (49/50) of shoes worn outdoors showed positive bacterial cultures compared to 56% (28/50) of shoes reserved for the OR only.5 In a study examining ventilation effects on airborne pathogens in the OR, 15% of OR airborne bacteria originated from OR floors, and higher bacterial counts correlated with a higher number of steps in the OR.2 In another study designed to evaluate SARS-CoV-2 distribution on hospital floors, 70% (7/10) of quantitative polymerase chain reaction assays performed on floor samples from intensive care units were positive. In addition, 100% (3/3) of swabs taken from hospital pharmacy floors with no COVID-19 patients were positive for SARS-CoV-2, meaning contaminated shoes likely served as vectors.6 Middle East respiratory syndrome, SARS-CoV-2, and influenza viruses may survive on porous and nonporous materials for hours to days.7Enterococcus, Candida, and Aspergillus may survive on textiles for up to 90 days.3

Recommendations for Hair and Shoe Coverings

We recommend that physicians utilize disposable skullcaps to cover the hair and consider a hooded gown or coverall for neck/ear coverage. We also recommend that physicians designate shoes that remain in the workplace and can be easily washed or disinfected at least weekly; physicians may choose to wash or disinfect shoes more often if they frequently are performing procedures that generate aerosols. Additionally, physicians should always wear shoe coverings when caring for patients (Table 1).

Our hair and shoe covering recommendations may serve to protect dermatologists when caring for patients. These protocols may be particularly important for dermatologists performing high-risk procedures, including facial surgery, intraoral/intranasal procedures, and treatment with ablative lasers and facial injectables, especially when the patient is unmasked. These recommendations may limit viral transmission to dermatologists and also protect individuals living in their households. Additional established guidelines by the American Academy of Dermatology, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, and World Health Organization are listed in Table 2.8-10

Current PPE recommendations that do not include hair and shoe coverings may be inadequate for limiting SARS-CoV-2 exposure between and among physicians and patients. Adherence to head covering and shoe recommendations may aid in reducing unwanted SARS-CoV-2 transmission in the health care setting, even as the pandemic continues.

Personal protective equipment (PPE) is an important component in limiting transmission of SARS-CoV-2. The World Health Organization and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued guidelines for appropriate PPE use, but recommendations for head and shoe coverings are lacking. In this article, we analyze the literature on pathogen transmission via hair and shoes and make evidence-based recommendations for PPE selection during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Pathogens on Shoes and Hair

Hair and shoes may act as vehicles for pathogen transmission. In a study that simulated contamination of uncovered skin in health care workers after intubating manikins in respiratory distress, 8 (100%) had fluorescent markers on the hair, 6 (75%) on the neck, and 4 (50%) on the shoes.1 In another study of postsurgical operating room (OR) surfaces (517 cultures), uncovered shoe tops and reusable hair coverings had 10-times more bacterial colony–forming units compared to other surfaces. On average, disposable shoe covers/head coverings had less than one-third bacterial colony–forming units compared with uncovered shoes/reusable hair coverings.2

Hair characteristics and coverings may affect pathogen transmission. Exposed hair may collect bacteria, as Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis attach to both scalp and facial hair. In one case, β-hemolytic streptococci cultured from the scalp of a perioperative nurse was linked to postsurgical infections in 20 patients.3 Hair coverings include bouffant caps and skullcaps. The bouffant cap is similar to a shower cap; it is relatively loose and secured around the head with elastic. The skullcap, or scrub cap, is tighter but leaves the neck nape and sideburns exposed. In a study comparing disposable bouffant caps, disposable skullcaps, and home-laundered cloth skullcaps worn by 2 teams of 5 surgeons, the disposable bouffant caps had the highest permeability, penetration, and microbial shed of airborne particles.4

Physicians’ shoes may act as fomites for transmission of pathogens to patients. In a study of 41 physicians and nurses in an acute care hospital, shoe soles were positive for at least one pathogen in 12 (29.3%) participants; methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus was most common. Additionally, 98% (49/50) of shoes worn outdoors showed positive bacterial cultures compared to 56% (28/50) of shoes reserved for the OR only.5 In a study examining ventilation effects on airborne pathogens in the OR, 15% of OR airborne bacteria originated from OR floors, and higher bacterial counts correlated with a higher number of steps in the OR.2 In another study designed to evaluate SARS-CoV-2 distribution on hospital floors, 70% (7/10) of quantitative polymerase chain reaction assays performed on floor samples from intensive care units were positive. In addition, 100% (3/3) of swabs taken from hospital pharmacy floors with no COVID-19 patients were positive for SARS-CoV-2, meaning contaminated shoes likely served as vectors.6 Middle East respiratory syndrome, SARS-CoV-2, and influenza viruses may survive on porous and nonporous materials for hours to days.7Enterococcus, Candida, and Aspergillus may survive on textiles for up to 90 days.3

Recommendations for Hair and Shoe Coverings

We recommend that physicians utilize disposable skullcaps to cover the hair and consider a hooded gown or coverall for neck/ear coverage. We also recommend that physicians designate shoes that remain in the workplace and can be easily washed or disinfected at least weekly; physicians may choose to wash or disinfect shoes more often if they frequently are performing procedures that generate aerosols. Additionally, physicians should always wear shoe coverings when caring for patients (Table 1).

Our hair and shoe covering recommendations may serve to protect dermatologists when caring for patients. These protocols may be particularly important for dermatologists performing high-risk procedures, including facial surgery, intraoral/intranasal procedures, and treatment with ablative lasers and facial injectables, especially when the patient is unmasked. These recommendations may limit viral transmission to dermatologists and also protect individuals living in their households. Additional established guidelines by the American Academy of Dermatology, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, and World Health Organization are listed in Table 2.8-10

Current PPE recommendations that do not include hair and shoe coverings may be inadequate for limiting SARS-CoV-2 exposure between and among physicians and patients. Adherence to head covering and shoe recommendations may aid in reducing unwanted SARS-CoV-2 transmission in the health care setting, even as the pandemic continues.

- Feldman O, Meir M, Shavit D, et al. Exposure to a surrogate measure of contamination from simulated patients by emergency department personnel wearing personal protective equipment. JAMA. 2020;323:2091-2093. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.6633

- Alexander JW, Van Sweringen H, Vanoss K, et al. Surveillance of bacterial colonization in operating rooms. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2013;14:345-351. doi:10.1089/sur.2012.134

- Blanchard J. Clinical issues—August 2010. AORN Journal. 2010;92:228-232. doi:10.1016/j.aorn.2010.06.001

- Markel TA, Gormley T, Greeley D, et al. Hats off: a study of different operating room headgear assessed by environmental quality indicators. J Am Coll Surg. 2017;225:573-581. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.08.014

- Kanwar A, Thakur M, Wazzan M, et al. Clothing and shoes of personnel as potential vectors for transfer of health care-associated pathogens to the community. Am J Infect Control. 2019;47:577-579. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2019.01.028

- Guo ZD, Wang ZY, Zhang SF, et al. Aerosol and surface distribution of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in hospital wards, Wuhan, China, 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1583-1591. doi:10.3201/eid2607.200885

- Otter JA, Donskey C, Yezli S, et al. Transmission of SARS and MERS coronaviruses and influenza virus in healthcare settings: the possible role of dry surface contamination. J Hosp Infect. 2016;92:235-250. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2015.08.027

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Science Brief: SARS-CoV-2 and Surface (Fomite) Transmission for Indoor Community Environments. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/more/science-and-research/surface-transmission.html#ref10

- American Academy of Dermatology. Clinical guidance for COVID-19. Accessed March 15, 2021. https://www.aad.org/member/practice/coronavirus/clinical-guidance

- Narla S, Alam M, Ozog DM, et al. American Society of Dermatologic Surgery Association (ASDSA) and American Society for Laser Medicine & Surgery (ASLMS) guidance for cosmetic dermatology practices during COVID-19. Updated January 11, 2021. Accessed March 15, 2021. https://www.asds.net/Portals/0/PDF/asdsa/asdsa-aslms-cosmetic-reopening-guidance.pdf

- World Health Organization. Country & technical guidance—coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Accessed March 15, 2021. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance-publications

- Feldman O, Meir M, Shavit D, et al. Exposure to a surrogate measure of contamination from simulated patients by emergency department personnel wearing personal protective equipment. JAMA. 2020;323:2091-2093. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.6633

- Alexander JW, Van Sweringen H, Vanoss K, et al. Surveillance of bacterial colonization in operating rooms. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2013;14:345-351. doi:10.1089/sur.2012.134

- Blanchard J. Clinical issues—August 2010. AORN Journal. 2010;92:228-232. doi:10.1016/j.aorn.2010.06.001

- Markel TA, Gormley T, Greeley D, et al. Hats off: a study of different operating room headgear assessed by environmental quality indicators. J Am Coll Surg. 2017;225:573-581. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.08.014

- Kanwar A, Thakur M, Wazzan M, et al. Clothing and shoes of personnel as potential vectors for transfer of health care-associated pathogens to the community. Am J Infect Control. 2019;47:577-579. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2019.01.028

- Guo ZD, Wang ZY, Zhang SF, et al. Aerosol and surface distribution of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in hospital wards, Wuhan, China, 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1583-1591. doi:10.3201/eid2607.200885

- Otter JA, Donskey C, Yezli S, et al. Transmission of SARS and MERS coronaviruses and influenza virus in healthcare settings: the possible role of dry surface contamination. J Hosp Infect. 2016;92:235-250. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2015.08.027

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Science Brief: SARS-CoV-2 and Surface (Fomite) Transmission for Indoor Community Environments. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/more/science-and-research/surface-transmission.html#ref10

- American Academy of Dermatology. Clinical guidance for COVID-19. Accessed March 15, 2021. https://www.aad.org/member/practice/coronavirus/clinical-guidance

- Narla S, Alam M, Ozog DM, et al. American Society of Dermatologic Surgery Association (ASDSA) and American Society for Laser Medicine & Surgery (ASLMS) guidance for cosmetic dermatology practices during COVID-19. Updated January 11, 2021. Accessed March 15, 2021. https://www.asds.net/Portals/0/PDF/asdsa/asdsa-aslms-cosmetic-reopening-guidance.pdf

- World Health Organization. Country & technical guidance—coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Accessed March 15, 2021. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance-publications

Practice Points

- Consistent use of personal protective equipment, including masks, face shields, goggles, and gloves, may limit transmission of SARS-CoV-2.

- Hair and shoes also may transmit SARS-CoV-2, but recommendations for hair and shoe coverings to prevent SARS-CoV-2 are lacking.