User login

The , an expert panel of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NAS) said on Aug. 9.

The assessment is urgently needed, the experts said, and the results should be shared with the Food and Drug Administration, which oversees sunscreens.

In its 400-page report, titled the Review of Fate, Exposure, and Effects of Sunscreens in Aquatic Environments and Implications for Sunscreen Usage and Human Health, the panel does not make recommendations but suggests that such an EPA risk assessment should highlight gaps in knowledge.

“We are teeing up the critical information that will be used to take on the challenge of risk assessment,” Charles A. Menzie, PhD, chair of the committee that wrote the report, said at a media briefing Aug. 9 when the report was released. Dr. Menzie is a principal at Exponent, Inc., an engineering and scientific consulting firm. He is former executive director of the Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry.

The EPA sponsored the study, which was conducted by a committee of the National Academy of Sciences, a nonprofit, nongovernmental organization authorized by Congress that studies issues related to science, technology, and medicine.

Balancing aquatic, human health concerns

Such an EPA assessment, Dr. Menzie said in a statement, will help inform efforts to understand the environmental effects of UV filters as well as clarify a path forward for managing sunscreens. For years, concerns have been raised about the potential toxicity of sunscreens regarding many marine and freshwater aquatic organisms, especially coral. That concern, however, must be balanced against the benefits of sunscreens, which are known to protect against skin cancer. A low percentage of people use sunscreen regularly, Dr. Menzie and other panel members said.

“Only about a third of the U.S. population regularly uses sunscreen,” Mark Cullen, MD, vice chair of the NAS committee and former director of the Center for Population Health Sciences, Stanford (Calif.) University, said at the briefing. About 70% or 80% of people use it at the beach or outdoors, he said.

Report background, details

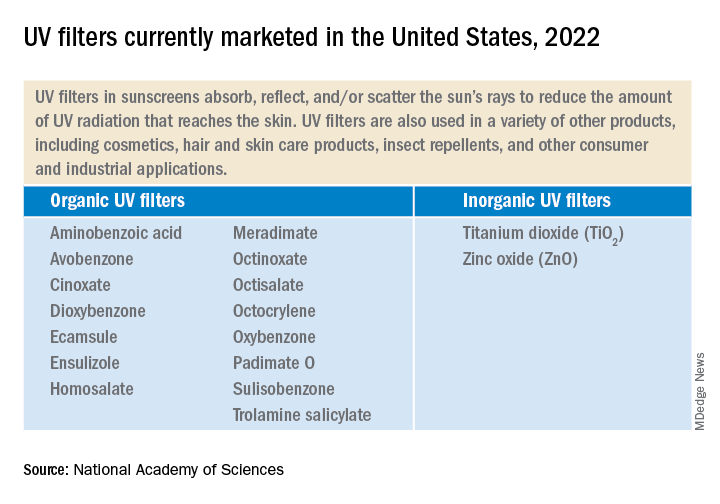

UV filters are the active ingredients in physical as well as chemical sunscreen products. They decrease the amount of UV radiation that reaches the skin. They have been found in water, sediments, and marine organisms, both saltwater and freshwater.

Currently, 17 UV filters are used in U.S. sunscreens; 15 of those are organic, such as oxybenzone and avobenzone, and are used in chemical sunscreens. They work by absorbing the rays before they damage the skin. In addition, two inorganic filters, which are used in physical sunscreens, sit on the skin and as a shield to block the rays.

UV filters enter bodies of water by direct release, as when sunscreens rinse off people while swimming or while engaging in other water activities. They also enter bodies of water in storm water runoff and wastewater.

Lab toxicity tests, which are the most widely used, provide effects data for ecologic risk assessment. The tests are more often used in the study of short-term, not long-term exposure. Test results have shown that in high enough concentrations, some UV filters can be toxic to algal, invertebrate, and fish species.

But much information is lacking, the experts said. Toxicity data for many species, for instance, are limited. There are few studies on the longer-term environmental effects of UV filter exposure. Not enough is known about the rate at which the filters degrade in the environment. The filters accumulate in higher amounts in different areas. Recreational water areas have higher concentrations.

The recommendations

The panel is urging the EPA to complete a formal risk assessment of the UV filters “with some urgency,” Dr. Cullen said. That will enable decisions to be made about the use of the products. The risks to aquatic life must be balanced against the need for sun protection to reduce skin cancer risk.

The experts made two recommendations:

- The EPA should conduct ecologic risk assessments for all the UV filters now marketed and for all new ones. The assessment should evaluate the filters individually as well as the risk from co-occurring filters. The assessments should take into account the different exposure scenarios.

- The EPA, along with partner agencies, and sunscreen and UV filter manufacturers should fund, support, and conduct research and share data. Research should include study of human health outcomes if usage and availability of sunscreens change.

Dermatologists should “continue to emphasize the importance of protection from UV radiation in every way that can be done,” Dr. Cullen said, including the use of sunscreen as well as other protective practices, such as wearing long sleeves and hats, seeking shade, and avoiding the sun during peak hours.

A dermatologist’s perspective

“I applaud their scientific curiosity to know one way or the other whether this is an issue,” said Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, DC. “I welcome this investigation.”

The multitude of studies, Dr. Friedman said, don’t always agree about whether the filters pose dangers. He noted that the concentration of UV filters detected in water is often lower than the concentrations found to be harmful in a lab setting to marine life, specifically coral.

However, he said, “these studies are snapshots.” For that reason, calling for more assessment of risk is desirable, Dr. Friedman said, but “I want to be sure the call to do more research is not an admission of guilt. It’s very easy to vilify sunscreens – but the facts we know are that UV light causes skin cancer and aging, and sunscreen protects us against this.”

Dr. Friedman has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The , an expert panel of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NAS) said on Aug. 9.

The assessment is urgently needed, the experts said, and the results should be shared with the Food and Drug Administration, which oversees sunscreens.

In its 400-page report, titled the Review of Fate, Exposure, and Effects of Sunscreens in Aquatic Environments and Implications for Sunscreen Usage and Human Health, the panel does not make recommendations but suggests that such an EPA risk assessment should highlight gaps in knowledge.

“We are teeing up the critical information that will be used to take on the challenge of risk assessment,” Charles A. Menzie, PhD, chair of the committee that wrote the report, said at a media briefing Aug. 9 when the report was released. Dr. Menzie is a principal at Exponent, Inc., an engineering and scientific consulting firm. He is former executive director of the Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry.

The EPA sponsored the study, which was conducted by a committee of the National Academy of Sciences, a nonprofit, nongovernmental organization authorized by Congress that studies issues related to science, technology, and medicine.

Balancing aquatic, human health concerns

Such an EPA assessment, Dr. Menzie said in a statement, will help inform efforts to understand the environmental effects of UV filters as well as clarify a path forward for managing sunscreens. For years, concerns have been raised about the potential toxicity of sunscreens regarding many marine and freshwater aquatic organisms, especially coral. That concern, however, must be balanced against the benefits of sunscreens, which are known to protect against skin cancer. A low percentage of people use sunscreen regularly, Dr. Menzie and other panel members said.

“Only about a third of the U.S. population regularly uses sunscreen,” Mark Cullen, MD, vice chair of the NAS committee and former director of the Center for Population Health Sciences, Stanford (Calif.) University, said at the briefing. About 70% or 80% of people use it at the beach or outdoors, he said.

Report background, details

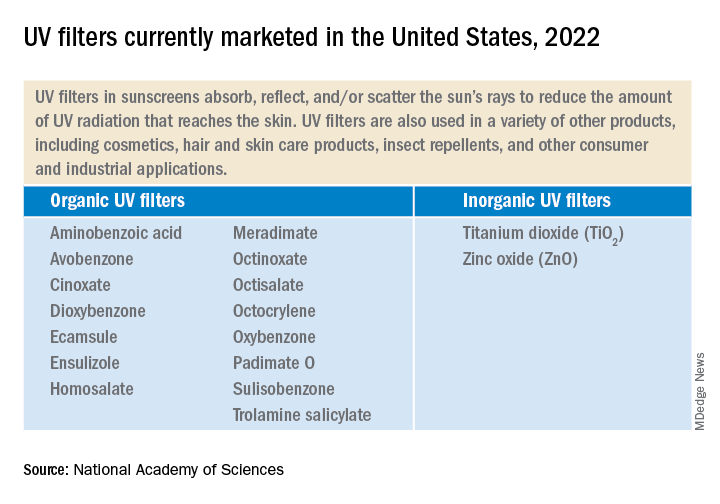

UV filters are the active ingredients in physical as well as chemical sunscreen products. They decrease the amount of UV radiation that reaches the skin. They have been found in water, sediments, and marine organisms, both saltwater and freshwater.

Currently, 17 UV filters are used in U.S. sunscreens; 15 of those are organic, such as oxybenzone and avobenzone, and are used in chemical sunscreens. They work by absorbing the rays before they damage the skin. In addition, two inorganic filters, which are used in physical sunscreens, sit on the skin and as a shield to block the rays.

UV filters enter bodies of water by direct release, as when sunscreens rinse off people while swimming or while engaging in other water activities. They also enter bodies of water in storm water runoff and wastewater.

Lab toxicity tests, which are the most widely used, provide effects data for ecologic risk assessment. The tests are more often used in the study of short-term, not long-term exposure. Test results have shown that in high enough concentrations, some UV filters can be toxic to algal, invertebrate, and fish species.

But much information is lacking, the experts said. Toxicity data for many species, for instance, are limited. There are few studies on the longer-term environmental effects of UV filter exposure. Not enough is known about the rate at which the filters degrade in the environment. The filters accumulate in higher amounts in different areas. Recreational water areas have higher concentrations.

The recommendations

The panel is urging the EPA to complete a formal risk assessment of the UV filters “with some urgency,” Dr. Cullen said. That will enable decisions to be made about the use of the products. The risks to aquatic life must be balanced against the need for sun protection to reduce skin cancer risk.

The experts made two recommendations:

- The EPA should conduct ecologic risk assessments for all the UV filters now marketed and for all new ones. The assessment should evaluate the filters individually as well as the risk from co-occurring filters. The assessments should take into account the different exposure scenarios.

- The EPA, along with partner agencies, and sunscreen and UV filter manufacturers should fund, support, and conduct research and share data. Research should include study of human health outcomes if usage and availability of sunscreens change.

Dermatologists should “continue to emphasize the importance of protection from UV radiation in every way that can be done,” Dr. Cullen said, including the use of sunscreen as well as other protective practices, such as wearing long sleeves and hats, seeking shade, and avoiding the sun during peak hours.

A dermatologist’s perspective

“I applaud their scientific curiosity to know one way or the other whether this is an issue,” said Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, DC. “I welcome this investigation.”

The multitude of studies, Dr. Friedman said, don’t always agree about whether the filters pose dangers. He noted that the concentration of UV filters detected in water is often lower than the concentrations found to be harmful in a lab setting to marine life, specifically coral.

However, he said, “these studies are snapshots.” For that reason, calling for more assessment of risk is desirable, Dr. Friedman said, but “I want to be sure the call to do more research is not an admission of guilt. It’s very easy to vilify sunscreens – but the facts we know are that UV light causes skin cancer and aging, and sunscreen protects us against this.”

Dr. Friedman has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The , an expert panel of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NAS) said on Aug. 9.

The assessment is urgently needed, the experts said, and the results should be shared with the Food and Drug Administration, which oversees sunscreens.

In its 400-page report, titled the Review of Fate, Exposure, and Effects of Sunscreens in Aquatic Environments and Implications for Sunscreen Usage and Human Health, the panel does not make recommendations but suggests that such an EPA risk assessment should highlight gaps in knowledge.

“We are teeing up the critical information that will be used to take on the challenge of risk assessment,” Charles A. Menzie, PhD, chair of the committee that wrote the report, said at a media briefing Aug. 9 when the report was released. Dr. Menzie is a principal at Exponent, Inc., an engineering and scientific consulting firm. He is former executive director of the Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry.

The EPA sponsored the study, which was conducted by a committee of the National Academy of Sciences, a nonprofit, nongovernmental organization authorized by Congress that studies issues related to science, technology, and medicine.

Balancing aquatic, human health concerns

Such an EPA assessment, Dr. Menzie said in a statement, will help inform efforts to understand the environmental effects of UV filters as well as clarify a path forward for managing sunscreens. For years, concerns have been raised about the potential toxicity of sunscreens regarding many marine and freshwater aquatic organisms, especially coral. That concern, however, must be balanced against the benefits of sunscreens, which are known to protect against skin cancer. A low percentage of people use sunscreen regularly, Dr. Menzie and other panel members said.

“Only about a third of the U.S. population regularly uses sunscreen,” Mark Cullen, MD, vice chair of the NAS committee and former director of the Center for Population Health Sciences, Stanford (Calif.) University, said at the briefing. About 70% or 80% of people use it at the beach or outdoors, he said.

Report background, details

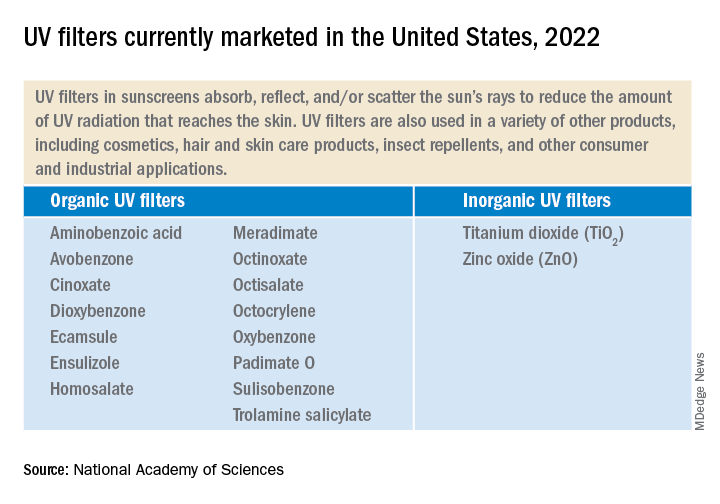

UV filters are the active ingredients in physical as well as chemical sunscreen products. They decrease the amount of UV radiation that reaches the skin. They have been found in water, sediments, and marine organisms, both saltwater and freshwater.

Currently, 17 UV filters are used in U.S. sunscreens; 15 of those are organic, such as oxybenzone and avobenzone, and are used in chemical sunscreens. They work by absorbing the rays before they damage the skin. In addition, two inorganic filters, which are used in physical sunscreens, sit on the skin and as a shield to block the rays.

UV filters enter bodies of water by direct release, as when sunscreens rinse off people while swimming or while engaging in other water activities. They also enter bodies of water in storm water runoff and wastewater.

Lab toxicity tests, which are the most widely used, provide effects data for ecologic risk assessment. The tests are more often used in the study of short-term, not long-term exposure. Test results have shown that in high enough concentrations, some UV filters can be toxic to algal, invertebrate, and fish species.

But much information is lacking, the experts said. Toxicity data for many species, for instance, are limited. There are few studies on the longer-term environmental effects of UV filter exposure. Not enough is known about the rate at which the filters degrade in the environment. The filters accumulate in higher amounts in different areas. Recreational water areas have higher concentrations.

The recommendations

The panel is urging the EPA to complete a formal risk assessment of the UV filters “with some urgency,” Dr. Cullen said. That will enable decisions to be made about the use of the products. The risks to aquatic life must be balanced against the need for sun protection to reduce skin cancer risk.

The experts made two recommendations:

- The EPA should conduct ecologic risk assessments for all the UV filters now marketed and for all new ones. The assessment should evaluate the filters individually as well as the risk from co-occurring filters. The assessments should take into account the different exposure scenarios.

- The EPA, along with partner agencies, and sunscreen and UV filter manufacturers should fund, support, and conduct research and share data. Research should include study of human health outcomes if usage and availability of sunscreens change.

Dermatologists should “continue to emphasize the importance of protection from UV radiation in every way that can be done,” Dr. Cullen said, including the use of sunscreen as well as other protective practices, such as wearing long sleeves and hats, seeking shade, and avoiding the sun during peak hours.

A dermatologist’s perspective

“I applaud their scientific curiosity to know one way or the other whether this is an issue,” said Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, DC. “I welcome this investigation.”

The multitude of studies, Dr. Friedman said, don’t always agree about whether the filters pose dangers. He noted that the concentration of UV filters detected in water is often lower than the concentrations found to be harmful in a lab setting to marine life, specifically coral.

However, he said, “these studies are snapshots.” For that reason, calling for more assessment of risk is desirable, Dr. Friedman said, but “I want to be sure the call to do more research is not an admission of guilt. It’s very easy to vilify sunscreens – but the facts we know are that UV light causes skin cancer and aging, and sunscreen protects us against this.”

Dr. Friedman has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.