User login

Older adults who participate in even light physical activity (LPA) may have a lower risk of developing dementia, new research suggests.

In a retrospective analysis of more than 62,000 individuals aged 65 or older without preexisting dementia, 6% developed dementia.

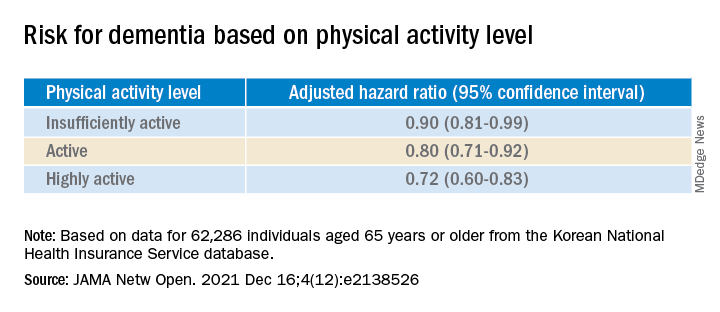

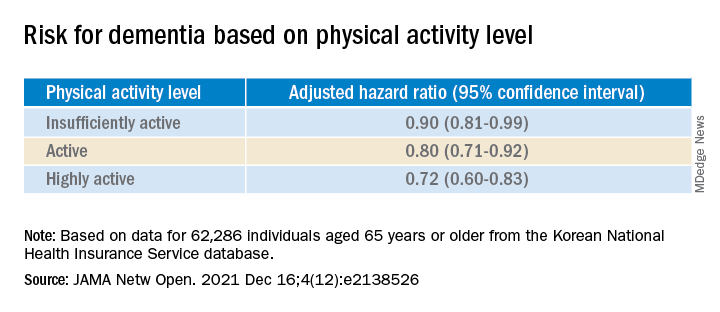

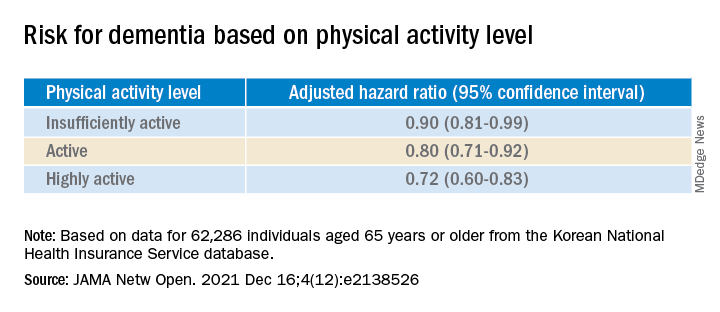

Compared with inactive individuals, “insufficiently active,” “active,” and “highly active” individuals all had a 10%, 20%, and 28% lower risk for dementia, respectively. And this association was consistent regardless of age, sex, other comorbidities, or after the researchers censored for stroke.

Even the lowest amount of LPA was associated with reduced dementia risk, investigators noted.

“In older adults, an increased physical activity level, including a low amount of LPA, was associated with a reduced risk of dementia,” Minjae Yoon, MD, division of cardiology, Severance Cardiovascular Hospital, Yonsei University, Seoul, South Korea, and colleagues wrote.

“Promotion of LPA might reduce the risk of dementia in older adults,” they added.

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Reverse causation?

Physical activity has been shown previously to be associated with reduced dementia risk. Current World Health Organization guidelines recommend that adults with normal cognition should engage in PA to reduce their risk for cognitive decline.

However, some studies have not yielded this result, “suggesting that previous findings showing a lower risk of dementia in physically active people could be attributed to reverse causation,” the investigators noted. Additionally, previous research regarding exercise intensity has been “inconsistent” concerning the role of LPA in reducing dementia risk.

Many older adults with frailty and comorbidity cannot perform intense or even moderate PA, therefore “these adults would have to gain the benefits of physical activity from LPA,” the researchers noted.

To clarify the potential association between PA and new-onset dementia, they focused specifically on the “dose-response association” between PA and dementia – especially LPA.

Between 2009 and 2012, the investigators enrolled 62,286 older individuals (60.4% women; mean age, 73.2 years) with available health checkup data from the National Health Insurance Service–Senior Database of Korea. All had no history of dementia.

Leisure-time PA was assessed with self-report questionnaires that used a 7-day recall method and included three questions regarding usual frequency (in days per week):

- Vigorous PA (VPA) for at least 20 minutes

- Moderate-intensity PA (MPA) for at least 30 minutes

- LPA for at least 30 minutes

VPA was defined as “intense exercise that caused severe shortness of breath, MPA was defined as activity causing mild shortness of breath, and LPA was defined as “walking at a slow or leisurely pace.”

PA-related energy expenditure was also calculated in metabolic equivalent (MET) minutes per week by “summing the product of frequency, intensity, and duration,” the investigators noted.

Participants were stratified on the basis of their weekly total PA levels into the following groups:

- Inactive (no LPA beyond basic movements)

- Insufficiently active (less than the recommended target range of 1-499 MET-min/wk)

- Active (meeting the recommended target range of 500-999 MET-min/wk)

- Highly active (exceeding the recommended target range of at least 1,000 MET-min/wk)

Of all participants, 35% were categorized as inactive, 25% were insufficiently active, 24.4% were active, and 15.2% were highly active.

Controversy remains

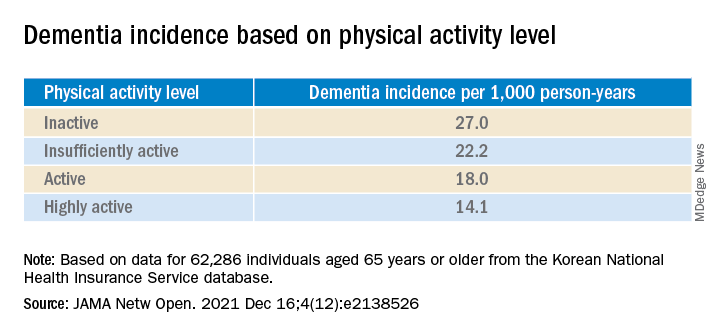

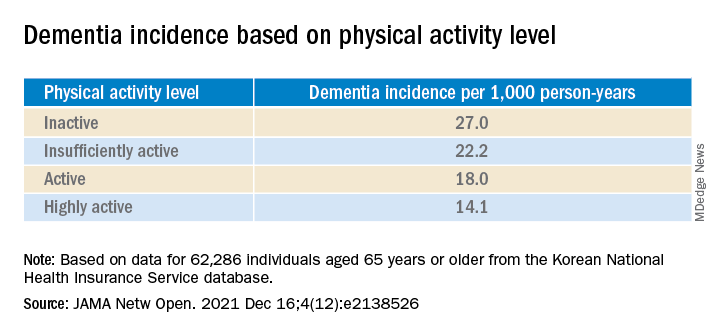

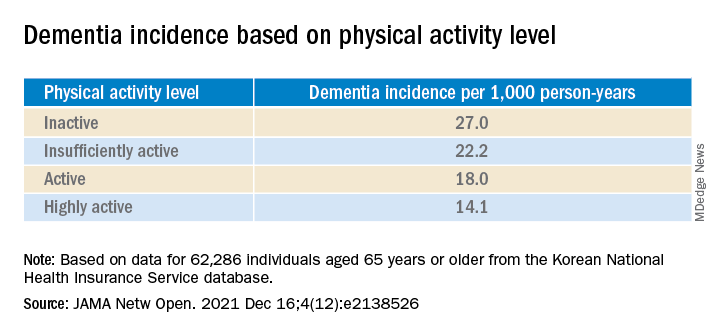

During the total median follow-up of 42 months, 6% of participants had all-cause dementia. After the researchers excluded the first 2 years, incidence of dementia was 21.6 per 1000 person-years during follow-up.

“The cumulative incidence of dementia was associated with a progressively decreasing trend with increasing physical activity” (P = .001 for trend), the investigators reported.

When using a competing-risk multivariable regression model, they found that higher levels of PA were associated with lower risk for dementia, compared with the inactive group.

Similar findings were obtained after censoring for stroke, and were consistent for all follow-up periods. In subgroup analysis, the association between PA level and dementia risk remained consistent, regardless of age, sex, and comorbidities.

Even a low amount of LPA (1-299 MET-min/wk) was linked to reduced risk for dementia versus total sedentary behavior (adjusted HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.74-0.99).

The investigators noted that some “controversy” remains regarding the possibility of reverse causation and, because their study was observational in nature, “it cannot be used to establish causal relationship.”

Nevertheless, the study had important strengths, including the large number of older adults with available data, the assessment of dose-response association between PA and dementia, and the sensitivity analyses they performed, the researchers added.

Piece of important evidence

Commenting on the findings, Takashi Tarumi, PhD, senior research investigator, National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology, Ibaraki, Japan, said previous studies have suggested “an inverse association between physical activity and dementia risk, such that older adults performing a higher dose of exercise may have a greater benefit for reducing the dementia risk.”

Dr. Tarumi, an associate editor at the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, added the current study “significantly extends our knowledge by showing that dementia risk can also be reduced by light physical activities when they are performed for longer hours.”

This provides “another piece of important evidence” to support clinicians recommending regular physical activity for the prevention of dementia in later life, said Dr. Tarumi, who was not involved with the research.

Also commenting, Martin Underwood, MD, Warwick Medical School, Coventry, England, described the association between reduced physical inactivity and dementia as well established – and noted the current study “appears to confirm earlier observational data showing this relationship.”

The current results have “still not been able to fully exclude the possibility of reverse causation,” said Dr. Underwood, who was also not associated with the study.

However, the finding that more physically active individuals are less likely to develop dementia “only becomes of real interest if we can show that increased physical activity prevents the onset, or slows the progression, of dementia,” he noted.

“To my knowledge this has not yet been established” in randomized clinical trials, Dr. Underwood added.

The study was supported by grants from the Patient-Centered Clinical Research Coordinating Center, funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea; and by a research grant from Yonsei University. One coauthor reported serving as a speaker for Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer, Medtronic, and Daiichi-Sankyo, and receiving research funds from Medtronic and Abbott. No other author disclosures were reported. Dr. Tarumi and Dr. Underwood have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Older adults who participate in even light physical activity (LPA) may have a lower risk of developing dementia, new research suggests.

In a retrospective analysis of more than 62,000 individuals aged 65 or older without preexisting dementia, 6% developed dementia.

Compared with inactive individuals, “insufficiently active,” “active,” and “highly active” individuals all had a 10%, 20%, and 28% lower risk for dementia, respectively. And this association was consistent regardless of age, sex, other comorbidities, or after the researchers censored for stroke.

Even the lowest amount of LPA was associated with reduced dementia risk, investigators noted.

“In older adults, an increased physical activity level, including a low amount of LPA, was associated with a reduced risk of dementia,” Minjae Yoon, MD, division of cardiology, Severance Cardiovascular Hospital, Yonsei University, Seoul, South Korea, and colleagues wrote.

“Promotion of LPA might reduce the risk of dementia in older adults,” they added.

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Reverse causation?

Physical activity has been shown previously to be associated with reduced dementia risk. Current World Health Organization guidelines recommend that adults with normal cognition should engage in PA to reduce their risk for cognitive decline.

However, some studies have not yielded this result, “suggesting that previous findings showing a lower risk of dementia in physically active people could be attributed to reverse causation,” the investigators noted. Additionally, previous research regarding exercise intensity has been “inconsistent” concerning the role of LPA in reducing dementia risk.

Many older adults with frailty and comorbidity cannot perform intense or even moderate PA, therefore “these adults would have to gain the benefits of physical activity from LPA,” the researchers noted.

To clarify the potential association between PA and new-onset dementia, they focused specifically on the “dose-response association” between PA and dementia – especially LPA.

Between 2009 and 2012, the investigators enrolled 62,286 older individuals (60.4% women; mean age, 73.2 years) with available health checkup data from the National Health Insurance Service–Senior Database of Korea. All had no history of dementia.

Leisure-time PA was assessed with self-report questionnaires that used a 7-day recall method and included three questions regarding usual frequency (in days per week):

- Vigorous PA (VPA) for at least 20 minutes

- Moderate-intensity PA (MPA) for at least 30 minutes

- LPA for at least 30 minutes

VPA was defined as “intense exercise that caused severe shortness of breath, MPA was defined as activity causing mild shortness of breath, and LPA was defined as “walking at a slow or leisurely pace.”

PA-related energy expenditure was also calculated in metabolic equivalent (MET) minutes per week by “summing the product of frequency, intensity, and duration,” the investigators noted.

Participants were stratified on the basis of their weekly total PA levels into the following groups:

- Inactive (no LPA beyond basic movements)

- Insufficiently active (less than the recommended target range of 1-499 MET-min/wk)

- Active (meeting the recommended target range of 500-999 MET-min/wk)

- Highly active (exceeding the recommended target range of at least 1,000 MET-min/wk)

Of all participants, 35% were categorized as inactive, 25% were insufficiently active, 24.4% were active, and 15.2% were highly active.

Controversy remains

During the total median follow-up of 42 months, 6% of participants had all-cause dementia. After the researchers excluded the first 2 years, incidence of dementia was 21.6 per 1000 person-years during follow-up.

“The cumulative incidence of dementia was associated with a progressively decreasing trend with increasing physical activity” (P = .001 for trend), the investigators reported.

When using a competing-risk multivariable regression model, they found that higher levels of PA were associated with lower risk for dementia, compared with the inactive group.

Similar findings were obtained after censoring for stroke, and were consistent for all follow-up periods. In subgroup analysis, the association between PA level and dementia risk remained consistent, regardless of age, sex, and comorbidities.

Even a low amount of LPA (1-299 MET-min/wk) was linked to reduced risk for dementia versus total sedentary behavior (adjusted HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.74-0.99).

The investigators noted that some “controversy” remains regarding the possibility of reverse causation and, because their study was observational in nature, “it cannot be used to establish causal relationship.”

Nevertheless, the study had important strengths, including the large number of older adults with available data, the assessment of dose-response association between PA and dementia, and the sensitivity analyses they performed, the researchers added.

Piece of important evidence

Commenting on the findings, Takashi Tarumi, PhD, senior research investigator, National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology, Ibaraki, Japan, said previous studies have suggested “an inverse association between physical activity and dementia risk, such that older adults performing a higher dose of exercise may have a greater benefit for reducing the dementia risk.”

Dr. Tarumi, an associate editor at the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, added the current study “significantly extends our knowledge by showing that dementia risk can also be reduced by light physical activities when they are performed for longer hours.”

This provides “another piece of important evidence” to support clinicians recommending regular physical activity for the prevention of dementia in later life, said Dr. Tarumi, who was not involved with the research.

Also commenting, Martin Underwood, MD, Warwick Medical School, Coventry, England, described the association between reduced physical inactivity and dementia as well established – and noted the current study “appears to confirm earlier observational data showing this relationship.”

The current results have “still not been able to fully exclude the possibility of reverse causation,” said Dr. Underwood, who was also not associated with the study.

However, the finding that more physically active individuals are less likely to develop dementia “only becomes of real interest if we can show that increased physical activity prevents the onset, or slows the progression, of dementia,” he noted.

“To my knowledge this has not yet been established” in randomized clinical trials, Dr. Underwood added.

The study was supported by grants from the Patient-Centered Clinical Research Coordinating Center, funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea; and by a research grant from Yonsei University. One coauthor reported serving as a speaker for Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer, Medtronic, and Daiichi-Sankyo, and receiving research funds from Medtronic and Abbott. No other author disclosures were reported. Dr. Tarumi and Dr. Underwood have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Older adults who participate in even light physical activity (LPA) may have a lower risk of developing dementia, new research suggests.

In a retrospective analysis of more than 62,000 individuals aged 65 or older without preexisting dementia, 6% developed dementia.

Compared with inactive individuals, “insufficiently active,” “active,” and “highly active” individuals all had a 10%, 20%, and 28% lower risk for dementia, respectively. And this association was consistent regardless of age, sex, other comorbidities, or after the researchers censored for stroke.

Even the lowest amount of LPA was associated with reduced dementia risk, investigators noted.

“In older adults, an increased physical activity level, including a low amount of LPA, was associated with a reduced risk of dementia,” Minjae Yoon, MD, division of cardiology, Severance Cardiovascular Hospital, Yonsei University, Seoul, South Korea, and colleagues wrote.

“Promotion of LPA might reduce the risk of dementia in older adults,” they added.

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Reverse causation?

Physical activity has been shown previously to be associated with reduced dementia risk. Current World Health Organization guidelines recommend that adults with normal cognition should engage in PA to reduce their risk for cognitive decline.

However, some studies have not yielded this result, “suggesting that previous findings showing a lower risk of dementia in physically active people could be attributed to reverse causation,” the investigators noted. Additionally, previous research regarding exercise intensity has been “inconsistent” concerning the role of LPA in reducing dementia risk.

Many older adults with frailty and comorbidity cannot perform intense or even moderate PA, therefore “these adults would have to gain the benefits of physical activity from LPA,” the researchers noted.

To clarify the potential association between PA and new-onset dementia, they focused specifically on the “dose-response association” between PA and dementia – especially LPA.

Between 2009 and 2012, the investigators enrolled 62,286 older individuals (60.4% women; mean age, 73.2 years) with available health checkup data from the National Health Insurance Service–Senior Database of Korea. All had no history of dementia.

Leisure-time PA was assessed with self-report questionnaires that used a 7-day recall method and included three questions regarding usual frequency (in days per week):

- Vigorous PA (VPA) for at least 20 minutes

- Moderate-intensity PA (MPA) for at least 30 minutes

- LPA for at least 30 minutes

VPA was defined as “intense exercise that caused severe shortness of breath, MPA was defined as activity causing mild shortness of breath, and LPA was defined as “walking at a slow or leisurely pace.”

PA-related energy expenditure was also calculated in metabolic equivalent (MET) minutes per week by “summing the product of frequency, intensity, and duration,” the investigators noted.

Participants were stratified on the basis of their weekly total PA levels into the following groups:

- Inactive (no LPA beyond basic movements)

- Insufficiently active (less than the recommended target range of 1-499 MET-min/wk)

- Active (meeting the recommended target range of 500-999 MET-min/wk)

- Highly active (exceeding the recommended target range of at least 1,000 MET-min/wk)

Of all participants, 35% were categorized as inactive, 25% were insufficiently active, 24.4% were active, and 15.2% were highly active.

Controversy remains

During the total median follow-up of 42 months, 6% of participants had all-cause dementia. After the researchers excluded the first 2 years, incidence of dementia was 21.6 per 1000 person-years during follow-up.

“The cumulative incidence of dementia was associated with a progressively decreasing trend with increasing physical activity” (P = .001 for trend), the investigators reported.

When using a competing-risk multivariable regression model, they found that higher levels of PA were associated with lower risk for dementia, compared with the inactive group.

Similar findings were obtained after censoring for stroke, and were consistent for all follow-up periods. In subgroup analysis, the association between PA level and dementia risk remained consistent, regardless of age, sex, and comorbidities.

Even a low amount of LPA (1-299 MET-min/wk) was linked to reduced risk for dementia versus total sedentary behavior (adjusted HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.74-0.99).

The investigators noted that some “controversy” remains regarding the possibility of reverse causation and, because their study was observational in nature, “it cannot be used to establish causal relationship.”

Nevertheless, the study had important strengths, including the large number of older adults with available data, the assessment of dose-response association between PA and dementia, and the sensitivity analyses they performed, the researchers added.

Piece of important evidence

Commenting on the findings, Takashi Tarumi, PhD, senior research investigator, National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology, Ibaraki, Japan, said previous studies have suggested “an inverse association between physical activity and dementia risk, such that older adults performing a higher dose of exercise may have a greater benefit for reducing the dementia risk.”

Dr. Tarumi, an associate editor at the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, added the current study “significantly extends our knowledge by showing that dementia risk can also be reduced by light physical activities when they are performed for longer hours.”

This provides “another piece of important evidence” to support clinicians recommending regular physical activity for the prevention of dementia in later life, said Dr. Tarumi, who was not involved with the research.

Also commenting, Martin Underwood, MD, Warwick Medical School, Coventry, England, described the association between reduced physical inactivity and dementia as well established – and noted the current study “appears to confirm earlier observational data showing this relationship.”

The current results have “still not been able to fully exclude the possibility of reverse causation,” said Dr. Underwood, who was also not associated with the study.

However, the finding that more physically active individuals are less likely to develop dementia “only becomes of real interest if we can show that increased physical activity prevents the onset, or slows the progression, of dementia,” he noted.

“To my knowledge this has not yet been established” in randomized clinical trials, Dr. Underwood added.

The study was supported by grants from the Patient-Centered Clinical Research Coordinating Center, funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea; and by a research grant from Yonsei University. One coauthor reported serving as a speaker for Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer, Medtronic, and Daiichi-Sankyo, and receiving research funds from Medtronic and Abbott. No other author disclosures were reported. Dr. Tarumi and Dr. Underwood have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.