User login

- Start by determining whether pain is located in the anterior, lateral, or posterior hip. As the site varies, so does the etiology.

- Besides location, consider sudden vs insidious onset, motions and positions that reproduce pain, predisposing activities, and effect of ambulation or weight bearing.

- Physical examination tests that elucidate range of motion, muscle strength, and pain replication will narrow the diagnostic search.

- Magnetic resonance imaging is usually diagnostic if plain x-rays and conservative therapy are ineffective.

- Conservative measures and selective use of injection therapy are usually effective.

Given the number of disorders capable of causing hip pain, and the fact that hip pathology can refer pain to other areas, and pathology elsewhere (particularly the lumbar spine) can refer pain to the hip,* a useful starting point in the evaluation is one that begins to narrow the search immediately.

*Medial groin pain is often included in the discussion of hip pain, but this topic is beyond the scope of this review.

In the work-up of hip pain, the first fact to establish is whether pain is felt in the anterior, lateral, or posterior part of the hip. Each location suggests a distinctive set of possible underlying causes. We provide diagnostic algorithms for all 3 scenarios, to aid in determining the best course for the work-up.

Anterior hip pain

Anterior hip pain (Figure 1), which is the most common, usually indicates pathology of the hip joint (ie, degenerative arthritis), hip flexor muscle strains or tendonitis, and iliopsoas bursitis. In a study by Lamberts and colleagues,5 by far the most common diagnosis of patients with hip complaints seen by their general practitioner was osteoarthritis. In a study of subjects older than 40 years who experienced a new episode of hip pain, 44% had evidence of osteoarthritis (level of evidence [LOE]=1b).6

Iliopsoas bursitis, a less common cause of anterior hip pain, involves inflammation of the bursa between the iliopsoas muscle and the iliopectineal eminence or “pelvic brim (Figure 2).

Stress fractures typically occur in athletes as the structural demands from training exceed bone remodeling (fatigue fractures), and may also occur in the setting of osteoporosis under normal physiologic loads (insufficiency fractures).

Labral tears have recently been recognized in younger athletic patients with unexplained hip joint pain and normal radiographic findings.7

FIGURE 1

Evaluating anterior hip pain

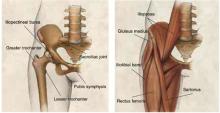

FIGURE 2

Hip joint

Anatomy of the hip joint and surrounding musculature.

Lateral hip pain

Lateral hip pain (Figure 3) is usually associated with greater trochanteric pain syndrome, iliotibial band syndrome, or meralgia paresthetica.

Greater trochanteric pain syndrome is a relatively new term that includes greater trochanteric bursitis and gluteus medius pathology.8,9 Trochanteric bursitis is a common cause of lateral hip pain, especially in older patients. However, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study of 24 women with greater trochanteric pain syndrome (described as chronic pain and tenderness over the lateral aspect of the hip) found that 45.8% had a gluteus medius tear and 62.5% had gluteus medius tendonitis, calling into question how many of these patients actually have bursitis (LOE=4).9

Iliotibial band syndrome is particularly common in athletes. It is caused by repetitive movement of the iliotibial band over the greater trochanter.

Meralgia paresthetica, an entrapment syndrome of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, is another cause of lateral hip pain that occurs more frequently in middle age. Meralgia paresthetica is characterized by hyperesthesia in the anterolateral thigh, although 23% of patients with this disorder also complain of lateral hip pain.10

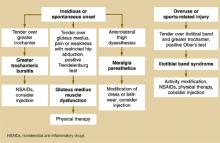

FIGURE 3

Evaluating lateral hip pain

Posterior hip pain

Posterior hip pain (Figure 4) is the least common pain pattern, and it usually suggests a source outside the hip joint. Posterior pain is typically referred from such disorders of the lumbar spine as degenerative disc disease, facet arthropathy, and spinal stenosis. Posterior hip pain is also caused by disorders of the sacroiliac joint, hip extensor and external rotator muscles, or, rarely, aortoiliac vascular occlusive disease.

The family physician in a typical practice can expect to see a patient with hip pain every 1 to 2 weeks, given that this complaint accounts for 0.61% of all visits to family practitioners, or about 1 in every 164 encounters.1 However, few studies shed light on the prevalence of hip disorders, and no clear consensus exists on this matter or even on terminology. Most information about causes of hip pain is drawn from expert opinion in a range of disciplines, including orthopedics, sports medicine, rheumatology, and family medicine.

Runners report an average yearly hip or pelvic injury rate of 2% to 11%.2 In the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III), 14.3% of patients aged 60 years and older reported significant hip pain on most days over the previous 6 weeks.3 Older women were more likely to report hip pain than older men. NHANES III also reported that 18.4% of those who had not participated in leisure time physical activity during the previous month reported severe hip pain as opposed to 12.6% of those who did engage in physical activity.

In younger patients, sports injuries about the hip and pelvis are most common in ballet dancers, soccer players, and runners (incidence of 44%, 13%, and 11% respectively).4

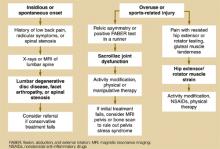

FIGURE 4

Evaluating posterior hip pain

Integrating history and physical examination

Little research has been performed to clarify the sensitivity and specificity of most history and physical examination maneuvers used in the diagnosis of hip pain. Therefore, much of the evaluation of hip pain is based on level 5 evidence: expert opinion.

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons created a clinical guideline on the evaluation of hip pain.11 Although a useful resource, this guideline focuses primarily on 3 diagnoses—osteoarthritis, inflammatory arthritis, and avascular necrosis—and does not expand upon the many other causes of hip pain that present to a primary care physician. Based on the available literature as well as our experience, we recommend the following approach to a patient with hip pain.

Medical history

After identifying whether the pain is anterior, lateral, or posterior (Figure 1, (Figure 3), and (Figure 4), focus on other characteristics of the pain—sudden vs insidious onset, movements and positions that reproduce the pain, predisposing activities, and the effect of ambulation or weight-bearing activity on the pain (Table 1).

In general, osteoarthritis and trochanteric bursitis are more common in older, less active patients, whereas stress fractures, iliopsoas strain or bursitis, and iliotibial band syndrome are more common in athletes. Complaints of a “snapping sensation may indicate iliopsoas bursitis if the snapping is anterior, or iliotibial band syndrome if the snapping is lateral.

Warning signs for other conditions. With any adult who has acute hip pain, be alert for “red flags that may indicate a more serious medical condition as the source of pain. Fever, malaise, night sweats, weight loss, night pain, intravenous drug abuse, a history of cancer, or known immunocompromised state should prompt you to consider such conditions as tumor, infection (ie, septic arthritis or osteomyelitis), or an inflammatory arthritis. Consider appropriate laboratory studies such as a complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein; and expedited imaging, diagnostic arthrocentesis, or referral. Fractures must also be excluded if there is a history of significant trauma, fall, or motor vehicle accident.

TABLE 1

Integrating the history and physical examination to diagnose hip pain

| Disorder | Presentation and exam findings | |

|---|---|---|

| Anterior pain | Osteoarthritis | Gradual onset anterior thigh/groin pain worsening with weight-bearing |

| Limited range of motion with pain, especially internal rotation (LOE=1b)12 | ||

| Abnormal FABER test | ||

| Hip flexor muscle strain/tendonitis | History of overuse or sports injury | |

| Pain with resisted muscle testing | ||

| Tenderness over specific muscle or tendon | ||

| Iliopsoas bursitis | Anterior pain and associated snapping sensation | |

| Tenderness with deep palpation over femoral triangle | ||

| Positive snapping hip maneuver | ||

| Etiology from overuse, acute trauma, or rheumatoid arthritis | ||

| Hip fracture (proximal femur) | Fall or trauma followed by inability to walk | |

| Limb externally rotated, abducted, and shortened | ||

| Pain with any movement | ||

| Stress fracture | History of overuse or osteoporosis | |

| Pain with weight-bearing activity; antalgic gait | ||

| Limited range of motion, sensitivity 87% (LOE=4)13 | ||

| Inflammatory arthritis | Morning stiffness or associated systemic symptoms | |

| Previous history of inflammatory arthritis | ||

| Limited range of motion and pain with passive motion | ||

| Acetabular labral tear | Activity-related sharp groin/anterior thigh pain, esp. upon hip extension | |

| Deep clicking felt, sensitivity 89% (LOE=4)14 | ||

| Positive Thomas flexion-extension test | ||

| Avascular necrosis of femoral head | Dull ache in groin, thigh, and buttock usually with risk factors (corticosteroid exposure, alcohol abuse) | |

| Limited range of movement with pain | ||

| Lateral pain | Greater trochanteric bursitis | Female:male 4:1, fourth to sixth decade |

| Spontaneous, insidious onset lateral hip pain | ||

| Point tenderness over greater trochanter | ||

| Gluteus medius muscle dysfunction | Pain with resisted hip abduction | |

| Tender over gluteus medius (cephalad to greater trochanter) | ||

| Trendelenburg test: sensitivity 72.7%, specificity 76.9% for detecting gluteus medius muscle tear (LOE=2b)9 | ||

| Iliotibial band syndrome | Lateral hip pain or snapping associated with walking, jogging, or cycling | |

| Positive Ober's test | ||

| Meralgia paresthetica | Numbness, tingling, and burning pain over anterolateral thigh | |

| Aggravated by extension of hip and with walking | ||

| Pressure over nerve may reproduce dysesthesia in distribution of lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (LOE=5)15 | ||

| Posterior pain | Referred pain from lumbar spine | History of low back pain |

| Pain reproduced with isolated lumbar flexion or extension | ||

| Radicular symptoms or history consistent with spinal stenosis | ||

| Sacroiliac joint dysfunction | Controversial diagnosis | |

| Posterior hip or buttocks pain usually in runners | ||

| Pelvic asymmetry found on exam | ||

| Hip extensor or rotator muscle strain | History of overuse or acute injury | |

| Pain with resisted muscle testing | ||

| Tender over gluteal muscles | ||

| LOE, level of evidence. For an explanation of levels of evidence. | ||

Physical examination

Begin your examination by observing the patient's gait and general ability to move around the examining room.

Range of motion. Carefully assess range of motion of the hip, comparing the affected side with the normal side to detect subtle limitations or painful movements. Range of motion testing includes passive hip flexion, internal and external rotation, and the flexion, abduction, and external rotation (FABER) test (Figure 5).

In the FABER test, the patient lies supine; the affected leg is flexed, abducted, and externally rotated. Lower the leg toward the table. A positive test elicits anterior or posterior pain and indicates hip or sacroiliac joint involvement.

The most predictive finding for osteoarthritis is decreased range of motion with restriction in internal rotation (LOE=1b).12 For those patients with one plane of restricted movement, the sensitivity for osteoarthritis is 100% and specificity is 42%; in 3 planes of restricted movement, sensitivity is 54% and specificity is 88% with a likelihood ratio of 4.4.12 A positive FABER test has been shown to be 88% sensitive for intra-articular pathology in an athletic population.16

Muscle testing. Test muscle strength to assess whether particular muscle groups are the source of pain. Maneuvers include resisted hip flexion, adduction, abduction, external rotation, and extension.

Other tests. With lateral hip pain, findings of weakness or pain while testing hip abduction may point to gluteus medius muscle dysfunction associated with greater trochanteric pain syndrome. The Trendelenburg test may also help. The patient stands on the affected leg. A negative test result occurs when the pelvis rises on the opposite side. A positive test result occurs when the pelvis on the opposite side drops and indicates a weak or painful gluteus medius muscle.

With Ober's test, the patient lies on his or her side with hips and knees flexed. The upper leg is passively extended then lowered to the table. Lateral hip pain or considerable tightness may indicate iliotibial band syndrome.

With the Thomas test, the contralateral hip is flexed, and the symptomatic hip is moved from full flexion to full extension. A deep click palpated may be indicative of a labral tear.

The snapping hip maneuver (Figure 6) may also be helpful in diagnosing the cause of pain. Loss of sensation to the anterolateral thigh is consistent with meralgia paresthetica.

Palpation. Finally, palpate over specific structures, such as the hip flexor muscles, greater trochanter, iliotibial band, and gluteus medius muscle, to further localize the source of pain. For instance, tenderness may be present over the anterior soft tissues in a hip flexor muscle strain or iliopsoas bursitis, and over the greater trochanter in trochanteric bursitis.

FIGURE 5

FABER test

FIGURE 6

Snapping hip maneuver

When diagnostic imaging is beneficial

In most cases, a thorough history and physical examination are adequate to establish a diagnosis. In the Lamberts study,5 only 16% of hip complaints required imaging for further elucidation. (Table 2) summarizes use of imaging studies with different disorders.

X-ray studies

Patients with a history of traumatic injury, osteoporosis, cancer, high-dose corticosteroid exposure, or alcohol abuse are at higher risk of such bony hip pathology as fracture, osteoarthritis, or avascular necrosis. These patients should undergo x-ray studies during their initial evaluation. An anteroposterior pelvic radiograph and a lateral radiograph of the hip are appropriate.

Although no specific patient age has been identified as a threshold for ordering x-ray studies, we recommend that all patients older than 65 years with new-onset hip pain undergo such studies.

We also recommend x-ray films for a patient of any age who has chronic severe hip pain.

TABLE 2

Indications for diagnostic imaging studies

| Disorder | Test | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Osteoarthritis | AP and lateral hip x-ray studies—weight-bearing17 | 2 |

| Muscle strain/tendonitis | None needed initially; consider MRI if not resolving | 5 |

| Greater trochanteric pain syndrome | None needed initially; consider MRI if not resolving9 | 4 |

| Hip fracture (proximal femur) | AP pelvis and cross table lateral x-ray studies | * |

| Stress fracture | MRI—sensitivity 100%13 | 4 |

| Iliopsoas bursitis | None needed initially; consider MRI if not resolving Can also use iliopsoas bursa imaging18-20 | 4 |

| Iliotibial band syndrome | None needed initially; consider MRI if not resolving | 5 |

| Meralgia paresthetica | Usually diagnosed by history. Can use sensory nerve conduction study21 | 4 |

| Inflammatory arthritis | Complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein, arthrocentesis, x-ray study | * |

| Referred pain from lumbar spine | MRI of lumbar spine | * |

| Avascular necrosis of femoral head | AP and lateral hip x-rays MRI for staging22 | 4 |

| Acetabular labral tear | MR arthrography—sensitivity 91%, specificity 71%23 25 | 4 |

| *Level of evidence not reported as specific references could not be found. | ||

| AP, anteroposterior; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging | ||

Magnetic resonance imaging

Advanced imaging may be required when initial conservative therapy is not effective or x-ray findings are unrevealing. Although computed tomography (CT) scan and bone scan have roles in the evaluation of some hip disorders, MRI has emerged as the study of choice in diagnosing hip pathology, especially in athletes.13

MRI offers valuable information regarding occult bony and cartilage injury such as stress fractures, avascular necrosis, and osteoarthritis, as well as soft tissue abnormalities such as muscle tears and bursitis. In a retrospective study of patients with suspected hip fracture but negative plain film results, MRI showed occult femoral fractures in 37% of patients, occult pelvic fractures in 23%, and associated soft-tissue abnormalities such as muscle edema and hematoma or joint effusion in 74%.26

Other imaging tests

In cases of suspected labral or intra-articular pathology, MR arthrography, anesthetic intraarticular injection and examination under local anesthesia, or diagnostic arthroscopy may be needed.16 These are relatively new techniques that help diagnose disorders not previously recognized.

Treatment

Depending on the presumed cause of pain, treatment options include activity modification, acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), analgesics, corticosteroid injections, physical therapy, and, if necessary, walking support.

Osteoarthritis. When symptoms persist despite conservative treatment for osteoarthritis, fluoroscopically guided intra-articular injection of a corticosteroid—or, more recently, viscosupplementation with hyaluronic acid preparations—may be useful in decreasing pain, and delaying or possibly avoiding hip arthroplasty (LOE=4).27-29

Greater trochanteric bursitis. Corticosteroid injection is also helpful and easily performed by a family physician for treatment of greater trochanteric bursitis, with 77% of patients improving in 1 week, and 61% with sustained improvement at 26 weeks (LOE=4).30

Iliopsoas bursitis. This disorder has been shown to respond to a physical therapy program emphasizing hip rotation strengthening (LOE=4).31 However, recalcitrant cases may require intrabursal injection or surgical lengthening of the iliopsoas muscle (LOE=4).32,33

Meralgia paresthetica. This condition may respond to an injection of corticosteroid adjacent to the anterior superior iliac spine near the emergence of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve.10 In cases of suspected sacroiliac joint dysfunction, manipulative therapy was shown to provide short-term improvement.34

When To Refer

When hip pain is refractory to conventional treatment, consider referral to a specialist, such as a sports medicine specialist, physiatrist, rheumatologist, or orthopedic surgeon.

1. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Hyattsville, Md: National Center for Health Statistics; 1995. CHS CD-ROM series 13, no. 11. Issued July 1997.

2. van Mechelen W. Running injuries. A review of the epidemiological literature. Sports Med 1992;14:320-335.

3. Christmas C, Crespo CJ, Franckowiak SC, Bathon JM, Bartlett SJ, Andersen RE. How common is hip pain among older adults? Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Fam Pract 2002;51:345-348.

4. Scopp JM, Moorman CT. The assessment of athletic hip injury. Clin Sports Med 2001;20:647-659.

5. Lamberts H, Brouwer HJ, Marinus AFM, Hofmans-Okkes IM. The use of ICPC in the Transition project.Episode-oriented epidemiology in general practice. In: Lamberts H, Wood M, Hofmans-Okkes IM, eds. International Classification of Primary Care in the European Community. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1993;45-93.

6. Birrell F, Croft P, Cooper C, Hosie G, Macfarlane GJ, Silman A. Radiographic change is common in new presenters in primary care with hip pain. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2000;39:772-775.

7. Hickman JM, Peters CL. Hip pain in the young adult: diagnosis and treatment of disorders of the acetabular labrum and acetabular dysplasia. Am J Orthop 2001;30:459-467.

8. Shbeeb MI, Matteson EL. Trochanteric bursitis (greater trochanter pain syndrome). Mayo Clin Proc 1996;71:565-569.

9. Bird PA, Oakley SP, Shnier R, Kirkham BW. Prospective evaluation of magnetic resonance imaging and physical examination findings in patients with greater trochanteric pain syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 2001;44:2138-2145.

10. Jones RK. Meralgia paresthetica as a cause of leg discomfort. Can Med Assoc J 1974;111:541-542.

11. Individual Clinical Guidelines: Hip Pain (non-traumatic) Phase 1. Version 1.0. Rosemont, Ill: Department of Research and Scientific Affairs, American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 1996.

12. Birrell F, Croft P, Cooper C, Hosie G, Macfarlane G, Silman A; PCR Hip Study Group. Predicting radiographic hip osteoarthritis from range of movement. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2001;40:506-512.

13. Shin AY, Morin WD, Gorman JD, Jones SB, Lapinsky AS. The superiority of magnetic resonance imaging in differentiating the cause of hip pain in endurance athletes. Am J Sports Med 1996;24:168-176.

14. McCarthy JC, Busconi B. The role of hip arthroscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of hip disease. Orthopedics 1995;18:753-756.

15. Grossman MG, Ducey SA, Nadler SS, Levy AS. Meralgia paresthetica: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2001;9:336-344.

16. Mitchell B, McCrory P, Brukner P, O'Donnell J, Colson E, Howells R. Hip joint pathology: clinical presentation and correlation between magnetic resonance arthrography, ultrasound, and arthroscopic findings in 25 consecutive cases. Clin J Sport Med 2003;13:152-156.

17. Croft P, Cooper C, Coggon D. Case definition of hip osteoarthritis in epidemiologic studies. J Rheumatol 1994;21:591-592.

18. Harper MC, Schaberg JE, Allen WC. Primary iliopsoas bursography in the diagnosis of disorders of the hip. Clin Orthop 1987;221:238-241.

19. Vaccaro JP, Sauser DD, Beals RK. Iliopsoas bursa imaging: efficacy in depicting abnormal iliopsoas tendon motion in patients with internal snapping hip syndrome. Radiology 1995;197:853-856.

20. Janzen DL, Partridge E, Logan PM, Connell DG, Duncan CP. The snapping hip: clinical and imaging findings in transient subluxation of the iliopsoas tendon. Can Assoc Radiol J 1996;47:202-208.

21. Seror P. Lateral femoral cutaneous nerve conduction v MRI may be required when conservative therapy is not effective or x-rays are unrevealing somatosensory evoked potentials for electrodiagnosis of meralgia paresthetica. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 1999;78:313-316.

22. Mitchell DG, Rao VM, Dalinka MK, et al. Femoral head avascular necrosis: correlation of MR imaging, radiographic staging, radionuclide imaging, and clinical findings. Radiology 1987;162:709-715.

23. Czerny C, Hofmann S, Neuhold A, et al. Lesions of the acetabular labrum: accuracy of MR imaging and MR arthrography in detection and staging. Radiology 1996;200:225-230.

24. Czerny C, Hofmann S, Urban M, et al. MR arthrography of the adult acetabular capsular-labral complex: correlation with surgery and anatomy. AJR Am J Roentengol 1999;173:345-349.

25. Petersilge DA, Haque MA, Petersilge WJ, Lewin JS, Lieberman JM, Buly R. Acetabular labral tears: evaluation with MR arthrography. Radiology 1996;200:231-235.

26. Bogost GA, Lizerbram EK, Crues JV. MR imaging in evaluation of suspected hip fracture: frequency of unsuspected bone and soft-tissue injury. Radiology 1995;197:263-267.

27. Creamer P. Intra-articular corticosteroid treatment in osteoarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 1999;11:417-421.

28. Migliore A, Martin LS, Alimonti A, Valente C, Tormenta S. Efficacy and safety of viscosupplementation by ultrasound-guided intra-articular injection in osteoarthrits of the hip. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2003;11:305-306.

29. Brocq O, Tran G, Breuil V, Grisot C, Flory P, Euller-Ziegler L. Hip osteoarthritis: short-term efficacy and safety of viscosupplementation by hylan G-F 20. An open-label study in 22 patients. Joint Bone Spine 2002;69:388-391.

30. Shbeeb MI, O'Duffy JD, Michet CJ, O'Fallon WM, Matteson EL. Evaluation of glucocorticosteroid injection for the treatment of trochanteric bursitis. J Rheumatol 1996;23:2104-2106.

31. Johnston CA, Lindsay DM, Wiley JP. Treatment of iliopsoas syndrome with a hip rotation strengthening program: a retrospective case series. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1999;29:218-224.

32. Johnston CA, Wiley JP, Lindsay DM, Wiseman DA. Iliopsoas bursitis and tendonitis. A review. Sports Med 1998;25:271-283.

33. Gruen GS, Scioscia TN, Lowenstein JE. The surgical treatment of internal snapping hip. Am J Sports Med 2002;30:607-613.

34. Cibulka MT, Delitto A. A comparison of two different methods to treat hip pain in runners. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1993;17:172-176.

- Start by determining whether pain is located in the anterior, lateral, or posterior hip. As the site varies, so does the etiology.

- Besides location, consider sudden vs insidious onset, motions and positions that reproduce pain, predisposing activities, and effect of ambulation or weight bearing.

- Physical examination tests that elucidate range of motion, muscle strength, and pain replication will narrow the diagnostic search.

- Magnetic resonance imaging is usually diagnostic if plain x-rays and conservative therapy are ineffective.

- Conservative measures and selective use of injection therapy are usually effective.

Given the number of disorders capable of causing hip pain, and the fact that hip pathology can refer pain to other areas, and pathology elsewhere (particularly the lumbar spine) can refer pain to the hip,* a useful starting point in the evaluation is one that begins to narrow the search immediately.

*Medial groin pain is often included in the discussion of hip pain, but this topic is beyond the scope of this review.

In the work-up of hip pain, the first fact to establish is whether pain is felt in the anterior, lateral, or posterior part of the hip. Each location suggests a distinctive set of possible underlying causes. We provide diagnostic algorithms for all 3 scenarios, to aid in determining the best course for the work-up.

Anterior hip pain

Anterior hip pain (Figure 1), which is the most common, usually indicates pathology of the hip joint (ie, degenerative arthritis), hip flexor muscle strains or tendonitis, and iliopsoas bursitis. In a study by Lamberts and colleagues,5 by far the most common diagnosis of patients with hip complaints seen by their general practitioner was osteoarthritis. In a study of subjects older than 40 years who experienced a new episode of hip pain, 44% had evidence of osteoarthritis (level of evidence [LOE]=1b).6

Iliopsoas bursitis, a less common cause of anterior hip pain, involves inflammation of the bursa between the iliopsoas muscle and the iliopectineal eminence or “pelvic brim (Figure 2).

Stress fractures typically occur in athletes as the structural demands from training exceed bone remodeling (fatigue fractures), and may also occur in the setting of osteoporosis under normal physiologic loads (insufficiency fractures).

Labral tears have recently been recognized in younger athletic patients with unexplained hip joint pain and normal radiographic findings.7

FIGURE 1

Evaluating anterior hip pain

FIGURE 2

Hip joint

Anatomy of the hip joint and surrounding musculature.

Lateral hip pain

Lateral hip pain (Figure 3) is usually associated with greater trochanteric pain syndrome, iliotibial band syndrome, or meralgia paresthetica.

Greater trochanteric pain syndrome is a relatively new term that includes greater trochanteric bursitis and gluteus medius pathology.8,9 Trochanteric bursitis is a common cause of lateral hip pain, especially in older patients. However, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study of 24 women with greater trochanteric pain syndrome (described as chronic pain and tenderness over the lateral aspect of the hip) found that 45.8% had a gluteus medius tear and 62.5% had gluteus medius tendonitis, calling into question how many of these patients actually have bursitis (LOE=4).9

Iliotibial band syndrome is particularly common in athletes. It is caused by repetitive movement of the iliotibial band over the greater trochanter.

Meralgia paresthetica, an entrapment syndrome of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, is another cause of lateral hip pain that occurs more frequently in middle age. Meralgia paresthetica is characterized by hyperesthesia in the anterolateral thigh, although 23% of patients with this disorder also complain of lateral hip pain.10

FIGURE 3

Evaluating lateral hip pain

Posterior hip pain

Posterior hip pain (Figure 4) is the least common pain pattern, and it usually suggests a source outside the hip joint. Posterior pain is typically referred from such disorders of the lumbar spine as degenerative disc disease, facet arthropathy, and spinal stenosis. Posterior hip pain is also caused by disorders of the sacroiliac joint, hip extensor and external rotator muscles, or, rarely, aortoiliac vascular occlusive disease.

The family physician in a typical practice can expect to see a patient with hip pain every 1 to 2 weeks, given that this complaint accounts for 0.61% of all visits to family practitioners, or about 1 in every 164 encounters.1 However, few studies shed light on the prevalence of hip disorders, and no clear consensus exists on this matter or even on terminology. Most information about causes of hip pain is drawn from expert opinion in a range of disciplines, including orthopedics, sports medicine, rheumatology, and family medicine.

Runners report an average yearly hip or pelvic injury rate of 2% to 11%.2 In the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III), 14.3% of patients aged 60 years and older reported significant hip pain on most days over the previous 6 weeks.3 Older women were more likely to report hip pain than older men. NHANES III also reported that 18.4% of those who had not participated in leisure time physical activity during the previous month reported severe hip pain as opposed to 12.6% of those who did engage in physical activity.

In younger patients, sports injuries about the hip and pelvis are most common in ballet dancers, soccer players, and runners (incidence of 44%, 13%, and 11% respectively).4

FIGURE 4

Evaluating posterior hip pain

Integrating history and physical examination

Little research has been performed to clarify the sensitivity and specificity of most history and physical examination maneuvers used in the diagnosis of hip pain. Therefore, much of the evaluation of hip pain is based on level 5 evidence: expert opinion.

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons created a clinical guideline on the evaluation of hip pain.11 Although a useful resource, this guideline focuses primarily on 3 diagnoses—osteoarthritis, inflammatory arthritis, and avascular necrosis—and does not expand upon the many other causes of hip pain that present to a primary care physician. Based on the available literature as well as our experience, we recommend the following approach to a patient with hip pain.

Medical history

After identifying whether the pain is anterior, lateral, or posterior (Figure 1, (Figure 3), and (Figure 4), focus on other characteristics of the pain—sudden vs insidious onset, movements and positions that reproduce the pain, predisposing activities, and the effect of ambulation or weight-bearing activity on the pain (Table 1).

In general, osteoarthritis and trochanteric bursitis are more common in older, less active patients, whereas stress fractures, iliopsoas strain or bursitis, and iliotibial band syndrome are more common in athletes. Complaints of a “snapping sensation may indicate iliopsoas bursitis if the snapping is anterior, or iliotibial band syndrome if the snapping is lateral.

Warning signs for other conditions. With any adult who has acute hip pain, be alert for “red flags that may indicate a more serious medical condition as the source of pain. Fever, malaise, night sweats, weight loss, night pain, intravenous drug abuse, a history of cancer, or known immunocompromised state should prompt you to consider such conditions as tumor, infection (ie, septic arthritis or osteomyelitis), or an inflammatory arthritis. Consider appropriate laboratory studies such as a complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein; and expedited imaging, diagnostic arthrocentesis, or referral. Fractures must also be excluded if there is a history of significant trauma, fall, or motor vehicle accident.

TABLE 1

Integrating the history and physical examination to diagnose hip pain

| Disorder | Presentation and exam findings | |

|---|---|---|

| Anterior pain | Osteoarthritis | Gradual onset anterior thigh/groin pain worsening with weight-bearing |

| Limited range of motion with pain, especially internal rotation (LOE=1b)12 | ||

| Abnormal FABER test | ||

| Hip flexor muscle strain/tendonitis | History of overuse or sports injury | |

| Pain with resisted muscle testing | ||

| Tenderness over specific muscle or tendon | ||

| Iliopsoas bursitis | Anterior pain and associated snapping sensation | |

| Tenderness with deep palpation over femoral triangle | ||

| Positive snapping hip maneuver | ||

| Etiology from overuse, acute trauma, or rheumatoid arthritis | ||

| Hip fracture (proximal femur) | Fall or trauma followed by inability to walk | |

| Limb externally rotated, abducted, and shortened | ||

| Pain with any movement | ||

| Stress fracture | History of overuse or osteoporosis | |

| Pain with weight-bearing activity; antalgic gait | ||

| Limited range of motion, sensitivity 87% (LOE=4)13 | ||

| Inflammatory arthritis | Morning stiffness or associated systemic symptoms | |

| Previous history of inflammatory arthritis | ||

| Limited range of motion and pain with passive motion | ||

| Acetabular labral tear | Activity-related sharp groin/anterior thigh pain, esp. upon hip extension | |

| Deep clicking felt, sensitivity 89% (LOE=4)14 | ||

| Positive Thomas flexion-extension test | ||

| Avascular necrosis of femoral head | Dull ache in groin, thigh, and buttock usually with risk factors (corticosteroid exposure, alcohol abuse) | |

| Limited range of movement with pain | ||

| Lateral pain | Greater trochanteric bursitis | Female:male 4:1, fourth to sixth decade |

| Spontaneous, insidious onset lateral hip pain | ||

| Point tenderness over greater trochanter | ||

| Gluteus medius muscle dysfunction | Pain with resisted hip abduction | |

| Tender over gluteus medius (cephalad to greater trochanter) | ||

| Trendelenburg test: sensitivity 72.7%, specificity 76.9% for detecting gluteus medius muscle tear (LOE=2b)9 | ||

| Iliotibial band syndrome | Lateral hip pain or snapping associated with walking, jogging, or cycling | |

| Positive Ober's test | ||

| Meralgia paresthetica | Numbness, tingling, and burning pain over anterolateral thigh | |

| Aggravated by extension of hip and with walking | ||

| Pressure over nerve may reproduce dysesthesia in distribution of lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (LOE=5)15 | ||

| Posterior pain | Referred pain from lumbar spine | History of low back pain |

| Pain reproduced with isolated lumbar flexion or extension | ||

| Radicular symptoms or history consistent with spinal stenosis | ||

| Sacroiliac joint dysfunction | Controversial diagnosis | |

| Posterior hip or buttocks pain usually in runners | ||

| Pelvic asymmetry found on exam | ||

| Hip extensor or rotator muscle strain | History of overuse or acute injury | |

| Pain with resisted muscle testing | ||

| Tender over gluteal muscles | ||

| LOE, level of evidence. For an explanation of levels of evidence. | ||

Physical examination

Begin your examination by observing the patient's gait and general ability to move around the examining room.

Range of motion. Carefully assess range of motion of the hip, comparing the affected side with the normal side to detect subtle limitations or painful movements. Range of motion testing includes passive hip flexion, internal and external rotation, and the flexion, abduction, and external rotation (FABER) test (Figure 5).

In the FABER test, the patient lies supine; the affected leg is flexed, abducted, and externally rotated. Lower the leg toward the table. A positive test elicits anterior or posterior pain and indicates hip or sacroiliac joint involvement.

The most predictive finding for osteoarthritis is decreased range of motion with restriction in internal rotation (LOE=1b).12 For those patients with one plane of restricted movement, the sensitivity for osteoarthritis is 100% and specificity is 42%; in 3 planes of restricted movement, sensitivity is 54% and specificity is 88% with a likelihood ratio of 4.4.12 A positive FABER test has been shown to be 88% sensitive for intra-articular pathology in an athletic population.16

Muscle testing. Test muscle strength to assess whether particular muscle groups are the source of pain. Maneuvers include resisted hip flexion, adduction, abduction, external rotation, and extension.

Other tests. With lateral hip pain, findings of weakness or pain while testing hip abduction may point to gluteus medius muscle dysfunction associated with greater trochanteric pain syndrome. The Trendelenburg test may also help. The patient stands on the affected leg. A negative test result occurs when the pelvis rises on the opposite side. A positive test result occurs when the pelvis on the opposite side drops and indicates a weak or painful gluteus medius muscle.

With Ober's test, the patient lies on his or her side with hips and knees flexed. The upper leg is passively extended then lowered to the table. Lateral hip pain or considerable tightness may indicate iliotibial band syndrome.

With the Thomas test, the contralateral hip is flexed, and the symptomatic hip is moved from full flexion to full extension. A deep click palpated may be indicative of a labral tear.

The snapping hip maneuver (Figure 6) may also be helpful in diagnosing the cause of pain. Loss of sensation to the anterolateral thigh is consistent with meralgia paresthetica.

Palpation. Finally, palpate over specific structures, such as the hip flexor muscles, greater trochanter, iliotibial band, and gluteus medius muscle, to further localize the source of pain. For instance, tenderness may be present over the anterior soft tissues in a hip flexor muscle strain or iliopsoas bursitis, and over the greater trochanter in trochanteric bursitis.

FIGURE 5

FABER test

FIGURE 6

Snapping hip maneuver

When diagnostic imaging is beneficial

In most cases, a thorough history and physical examination are adequate to establish a diagnosis. In the Lamberts study,5 only 16% of hip complaints required imaging for further elucidation. (Table 2) summarizes use of imaging studies with different disorders.

X-ray studies

Patients with a history of traumatic injury, osteoporosis, cancer, high-dose corticosteroid exposure, or alcohol abuse are at higher risk of such bony hip pathology as fracture, osteoarthritis, or avascular necrosis. These patients should undergo x-ray studies during their initial evaluation. An anteroposterior pelvic radiograph and a lateral radiograph of the hip are appropriate.

Although no specific patient age has been identified as a threshold for ordering x-ray studies, we recommend that all patients older than 65 years with new-onset hip pain undergo such studies.

We also recommend x-ray films for a patient of any age who has chronic severe hip pain.

TABLE 2

Indications for diagnostic imaging studies

| Disorder | Test | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Osteoarthritis | AP and lateral hip x-ray studies—weight-bearing17 | 2 |

| Muscle strain/tendonitis | None needed initially; consider MRI if not resolving | 5 |

| Greater trochanteric pain syndrome | None needed initially; consider MRI if not resolving9 | 4 |

| Hip fracture (proximal femur) | AP pelvis and cross table lateral x-ray studies | * |

| Stress fracture | MRI—sensitivity 100%13 | 4 |

| Iliopsoas bursitis | None needed initially; consider MRI if not resolving Can also use iliopsoas bursa imaging18-20 | 4 |

| Iliotibial band syndrome | None needed initially; consider MRI if not resolving | 5 |

| Meralgia paresthetica | Usually diagnosed by history. Can use sensory nerve conduction study21 | 4 |

| Inflammatory arthritis | Complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein, arthrocentesis, x-ray study | * |

| Referred pain from lumbar spine | MRI of lumbar spine | * |

| Avascular necrosis of femoral head | AP and lateral hip x-rays MRI for staging22 | 4 |

| Acetabular labral tear | MR arthrography—sensitivity 91%, specificity 71%23 25 | 4 |

| *Level of evidence not reported as specific references could not be found. | ||

| AP, anteroposterior; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging | ||

Magnetic resonance imaging

Advanced imaging may be required when initial conservative therapy is not effective or x-ray findings are unrevealing. Although computed tomography (CT) scan and bone scan have roles in the evaluation of some hip disorders, MRI has emerged as the study of choice in diagnosing hip pathology, especially in athletes.13

MRI offers valuable information regarding occult bony and cartilage injury such as stress fractures, avascular necrosis, and osteoarthritis, as well as soft tissue abnormalities such as muscle tears and bursitis. In a retrospective study of patients with suspected hip fracture but negative plain film results, MRI showed occult femoral fractures in 37% of patients, occult pelvic fractures in 23%, and associated soft-tissue abnormalities such as muscle edema and hematoma or joint effusion in 74%.26

Other imaging tests

In cases of suspected labral or intra-articular pathology, MR arthrography, anesthetic intraarticular injection and examination under local anesthesia, or diagnostic arthroscopy may be needed.16 These are relatively new techniques that help diagnose disorders not previously recognized.

Treatment

Depending on the presumed cause of pain, treatment options include activity modification, acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), analgesics, corticosteroid injections, physical therapy, and, if necessary, walking support.

Osteoarthritis. When symptoms persist despite conservative treatment for osteoarthritis, fluoroscopically guided intra-articular injection of a corticosteroid—or, more recently, viscosupplementation with hyaluronic acid preparations—may be useful in decreasing pain, and delaying or possibly avoiding hip arthroplasty (LOE=4).27-29

Greater trochanteric bursitis. Corticosteroid injection is also helpful and easily performed by a family physician for treatment of greater trochanteric bursitis, with 77% of patients improving in 1 week, and 61% with sustained improvement at 26 weeks (LOE=4).30

Iliopsoas bursitis. This disorder has been shown to respond to a physical therapy program emphasizing hip rotation strengthening (LOE=4).31 However, recalcitrant cases may require intrabursal injection or surgical lengthening of the iliopsoas muscle (LOE=4).32,33

Meralgia paresthetica. This condition may respond to an injection of corticosteroid adjacent to the anterior superior iliac spine near the emergence of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve.10 In cases of suspected sacroiliac joint dysfunction, manipulative therapy was shown to provide short-term improvement.34

When To Refer

When hip pain is refractory to conventional treatment, consider referral to a specialist, such as a sports medicine specialist, physiatrist, rheumatologist, or orthopedic surgeon.

- Start by determining whether pain is located in the anterior, lateral, or posterior hip. As the site varies, so does the etiology.

- Besides location, consider sudden vs insidious onset, motions and positions that reproduce pain, predisposing activities, and effect of ambulation or weight bearing.

- Physical examination tests that elucidate range of motion, muscle strength, and pain replication will narrow the diagnostic search.

- Magnetic resonance imaging is usually diagnostic if plain x-rays and conservative therapy are ineffective.

- Conservative measures and selective use of injection therapy are usually effective.

Given the number of disorders capable of causing hip pain, and the fact that hip pathology can refer pain to other areas, and pathology elsewhere (particularly the lumbar spine) can refer pain to the hip,* a useful starting point in the evaluation is one that begins to narrow the search immediately.

*Medial groin pain is often included in the discussion of hip pain, but this topic is beyond the scope of this review.

In the work-up of hip pain, the first fact to establish is whether pain is felt in the anterior, lateral, or posterior part of the hip. Each location suggests a distinctive set of possible underlying causes. We provide diagnostic algorithms for all 3 scenarios, to aid in determining the best course for the work-up.

Anterior hip pain

Anterior hip pain (Figure 1), which is the most common, usually indicates pathology of the hip joint (ie, degenerative arthritis), hip flexor muscle strains or tendonitis, and iliopsoas bursitis. In a study by Lamberts and colleagues,5 by far the most common diagnosis of patients with hip complaints seen by their general practitioner was osteoarthritis. In a study of subjects older than 40 years who experienced a new episode of hip pain, 44% had evidence of osteoarthritis (level of evidence [LOE]=1b).6

Iliopsoas bursitis, a less common cause of anterior hip pain, involves inflammation of the bursa between the iliopsoas muscle and the iliopectineal eminence or “pelvic brim (Figure 2).

Stress fractures typically occur in athletes as the structural demands from training exceed bone remodeling (fatigue fractures), and may also occur in the setting of osteoporosis under normal physiologic loads (insufficiency fractures).

Labral tears have recently been recognized in younger athletic patients with unexplained hip joint pain and normal radiographic findings.7

FIGURE 1

Evaluating anterior hip pain

FIGURE 2

Hip joint

Anatomy of the hip joint and surrounding musculature.

Lateral hip pain

Lateral hip pain (Figure 3) is usually associated with greater trochanteric pain syndrome, iliotibial band syndrome, or meralgia paresthetica.

Greater trochanteric pain syndrome is a relatively new term that includes greater trochanteric bursitis and gluteus medius pathology.8,9 Trochanteric bursitis is a common cause of lateral hip pain, especially in older patients. However, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study of 24 women with greater trochanteric pain syndrome (described as chronic pain and tenderness over the lateral aspect of the hip) found that 45.8% had a gluteus medius tear and 62.5% had gluteus medius tendonitis, calling into question how many of these patients actually have bursitis (LOE=4).9

Iliotibial band syndrome is particularly common in athletes. It is caused by repetitive movement of the iliotibial band over the greater trochanter.

Meralgia paresthetica, an entrapment syndrome of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, is another cause of lateral hip pain that occurs more frequently in middle age. Meralgia paresthetica is characterized by hyperesthesia in the anterolateral thigh, although 23% of patients with this disorder also complain of lateral hip pain.10

FIGURE 3

Evaluating lateral hip pain

Posterior hip pain

Posterior hip pain (Figure 4) is the least common pain pattern, and it usually suggests a source outside the hip joint. Posterior pain is typically referred from such disorders of the lumbar spine as degenerative disc disease, facet arthropathy, and spinal stenosis. Posterior hip pain is also caused by disorders of the sacroiliac joint, hip extensor and external rotator muscles, or, rarely, aortoiliac vascular occlusive disease.

The family physician in a typical practice can expect to see a patient with hip pain every 1 to 2 weeks, given that this complaint accounts for 0.61% of all visits to family practitioners, or about 1 in every 164 encounters.1 However, few studies shed light on the prevalence of hip disorders, and no clear consensus exists on this matter or even on terminology. Most information about causes of hip pain is drawn from expert opinion in a range of disciplines, including orthopedics, sports medicine, rheumatology, and family medicine.

Runners report an average yearly hip or pelvic injury rate of 2% to 11%.2 In the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III), 14.3% of patients aged 60 years and older reported significant hip pain on most days over the previous 6 weeks.3 Older women were more likely to report hip pain than older men. NHANES III also reported that 18.4% of those who had not participated in leisure time physical activity during the previous month reported severe hip pain as opposed to 12.6% of those who did engage in physical activity.

In younger patients, sports injuries about the hip and pelvis are most common in ballet dancers, soccer players, and runners (incidence of 44%, 13%, and 11% respectively).4

FIGURE 4

Evaluating posterior hip pain

Integrating history and physical examination

Little research has been performed to clarify the sensitivity and specificity of most history and physical examination maneuvers used in the diagnosis of hip pain. Therefore, much of the evaluation of hip pain is based on level 5 evidence: expert opinion.

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons created a clinical guideline on the evaluation of hip pain.11 Although a useful resource, this guideline focuses primarily on 3 diagnoses—osteoarthritis, inflammatory arthritis, and avascular necrosis—and does not expand upon the many other causes of hip pain that present to a primary care physician. Based on the available literature as well as our experience, we recommend the following approach to a patient with hip pain.

Medical history

After identifying whether the pain is anterior, lateral, or posterior (Figure 1, (Figure 3), and (Figure 4), focus on other characteristics of the pain—sudden vs insidious onset, movements and positions that reproduce the pain, predisposing activities, and the effect of ambulation or weight-bearing activity on the pain (Table 1).

In general, osteoarthritis and trochanteric bursitis are more common in older, less active patients, whereas stress fractures, iliopsoas strain or bursitis, and iliotibial band syndrome are more common in athletes. Complaints of a “snapping sensation may indicate iliopsoas bursitis if the snapping is anterior, or iliotibial band syndrome if the snapping is lateral.

Warning signs for other conditions. With any adult who has acute hip pain, be alert for “red flags that may indicate a more serious medical condition as the source of pain. Fever, malaise, night sweats, weight loss, night pain, intravenous drug abuse, a history of cancer, or known immunocompromised state should prompt you to consider such conditions as tumor, infection (ie, septic arthritis or osteomyelitis), or an inflammatory arthritis. Consider appropriate laboratory studies such as a complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein; and expedited imaging, diagnostic arthrocentesis, or referral. Fractures must also be excluded if there is a history of significant trauma, fall, or motor vehicle accident.

TABLE 1

Integrating the history and physical examination to diagnose hip pain

| Disorder | Presentation and exam findings | |

|---|---|---|

| Anterior pain | Osteoarthritis | Gradual onset anterior thigh/groin pain worsening with weight-bearing |

| Limited range of motion with pain, especially internal rotation (LOE=1b)12 | ||

| Abnormal FABER test | ||

| Hip flexor muscle strain/tendonitis | History of overuse or sports injury | |

| Pain with resisted muscle testing | ||

| Tenderness over specific muscle or tendon | ||

| Iliopsoas bursitis | Anterior pain and associated snapping sensation | |

| Tenderness with deep palpation over femoral triangle | ||

| Positive snapping hip maneuver | ||

| Etiology from overuse, acute trauma, or rheumatoid arthritis | ||

| Hip fracture (proximal femur) | Fall or trauma followed by inability to walk | |

| Limb externally rotated, abducted, and shortened | ||

| Pain with any movement | ||

| Stress fracture | History of overuse or osteoporosis | |

| Pain with weight-bearing activity; antalgic gait | ||

| Limited range of motion, sensitivity 87% (LOE=4)13 | ||

| Inflammatory arthritis | Morning stiffness or associated systemic symptoms | |

| Previous history of inflammatory arthritis | ||

| Limited range of motion and pain with passive motion | ||

| Acetabular labral tear | Activity-related sharp groin/anterior thigh pain, esp. upon hip extension | |

| Deep clicking felt, sensitivity 89% (LOE=4)14 | ||

| Positive Thomas flexion-extension test | ||

| Avascular necrosis of femoral head | Dull ache in groin, thigh, and buttock usually with risk factors (corticosteroid exposure, alcohol abuse) | |

| Limited range of movement with pain | ||

| Lateral pain | Greater trochanteric bursitis | Female:male 4:1, fourth to sixth decade |

| Spontaneous, insidious onset lateral hip pain | ||

| Point tenderness over greater trochanter | ||

| Gluteus medius muscle dysfunction | Pain with resisted hip abduction | |

| Tender over gluteus medius (cephalad to greater trochanter) | ||

| Trendelenburg test: sensitivity 72.7%, specificity 76.9% for detecting gluteus medius muscle tear (LOE=2b)9 | ||

| Iliotibial band syndrome | Lateral hip pain or snapping associated with walking, jogging, or cycling | |

| Positive Ober's test | ||

| Meralgia paresthetica | Numbness, tingling, and burning pain over anterolateral thigh | |

| Aggravated by extension of hip and with walking | ||

| Pressure over nerve may reproduce dysesthesia in distribution of lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (LOE=5)15 | ||

| Posterior pain | Referred pain from lumbar spine | History of low back pain |

| Pain reproduced with isolated lumbar flexion or extension | ||

| Radicular symptoms or history consistent with spinal stenosis | ||

| Sacroiliac joint dysfunction | Controversial diagnosis | |

| Posterior hip or buttocks pain usually in runners | ||

| Pelvic asymmetry found on exam | ||

| Hip extensor or rotator muscle strain | History of overuse or acute injury | |

| Pain with resisted muscle testing | ||

| Tender over gluteal muscles | ||

| LOE, level of evidence. For an explanation of levels of evidence. | ||

Physical examination

Begin your examination by observing the patient's gait and general ability to move around the examining room.

Range of motion. Carefully assess range of motion of the hip, comparing the affected side with the normal side to detect subtle limitations or painful movements. Range of motion testing includes passive hip flexion, internal and external rotation, and the flexion, abduction, and external rotation (FABER) test (Figure 5).

In the FABER test, the patient lies supine; the affected leg is flexed, abducted, and externally rotated. Lower the leg toward the table. A positive test elicits anterior or posterior pain and indicates hip or sacroiliac joint involvement.

The most predictive finding for osteoarthritis is decreased range of motion with restriction in internal rotation (LOE=1b).12 For those patients with one plane of restricted movement, the sensitivity for osteoarthritis is 100% and specificity is 42%; in 3 planes of restricted movement, sensitivity is 54% and specificity is 88% with a likelihood ratio of 4.4.12 A positive FABER test has been shown to be 88% sensitive for intra-articular pathology in an athletic population.16

Muscle testing. Test muscle strength to assess whether particular muscle groups are the source of pain. Maneuvers include resisted hip flexion, adduction, abduction, external rotation, and extension.

Other tests. With lateral hip pain, findings of weakness or pain while testing hip abduction may point to gluteus medius muscle dysfunction associated with greater trochanteric pain syndrome. The Trendelenburg test may also help. The patient stands on the affected leg. A negative test result occurs when the pelvis rises on the opposite side. A positive test result occurs when the pelvis on the opposite side drops and indicates a weak or painful gluteus medius muscle.

With Ober's test, the patient lies on his or her side with hips and knees flexed. The upper leg is passively extended then lowered to the table. Lateral hip pain or considerable tightness may indicate iliotibial band syndrome.

With the Thomas test, the contralateral hip is flexed, and the symptomatic hip is moved from full flexion to full extension. A deep click palpated may be indicative of a labral tear.

The snapping hip maneuver (Figure 6) may also be helpful in diagnosing the cause of pain. Loss of sensation to the anterolateral thigh is consistent with meralgia paresthetica.

Palpation. Finally, palpate over specific structures, such as the hip flexor muscles, greater trochanter, iliotibial band, and gluteus medius muscle, to further localize the source of pain. For instance, tenderness may be present over the anterior soft tissues in a hip flexor muscle strain or iliopsoas bursitis, and over the greater trochanter in trochanteric bursitis.

FIGURE 5

FABER test

FIGURE 6

Snapping hip maneuver

When diagnostic imaging is beneficial

In most cases, a thorough history and physical examination are adequate to establish a diagnosis. In the Lamberts study,5 only 16% of hip complaints required imaging for further elucidation. (Table 2) summarizes use of imaging studies with different disorders.

X-ray studies

Patients with a history of traumatic injury, osteoporosis, cancer, high-dose corticosteroid exposure, or alcohol abuse are at higher risk of such bony hip pathology as fracture, osteoarthritis, or avascular necrosis. These patients should undergo x-ray studies during their initial evaluation. An anteroposterior pelvic radiograph and a lateral radiograph of the hip are appropriate.

Although no specific patient age has been identified as a threshold for ordering x-ray studies, we recommend that all patients older than 65 years with new-onset hip pain undergo such studies.

We also recommend x-ray films for a patient of any age who has chronic severe hip pain.

TABLE 2

Indications for diagnostic imaging studies

| Disorder | Test | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Osteoarthritis | AP and lateral hip x-ray studies—weight-bearing17 | 2 |

| Muscle strain/tendonitis | None needed initially; consider MRI if not resolving | 5 |

| Greater trochanteric pain syndrome | None needed initially; consider MRI if not resolving9 | 4 |

| Hip fracture (proximal femur) | AP pelvis and cross table lateral x-ray studies | * |

| Stress fracture | MRI—sensitivity 100%13 | 4 |

| Iliopsoas bursitis | None needed initially; consider MRI if not resolving Can also use iliopsoas bursa imaging18-20 | 4 |

| Iliotibial band syndrome | None needed initially; consider MRI if not resolving | 5 |

| Meralgia paresthetica | Usually diagnosed by history. Can use sensory nerve conduction study21 | 4 |

| Inflammatory arthritis | Complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein, arthrocentesis, x-ray study | * |

| Referred pain from lumbar spine | MRI of lumbar spine | * |

| Avascular necrosis of femoral head | AP and lateral hip x-rays MRI for staging22 | 4 |

| Acetabular labral tear | MR arthrography—sensitivity 91%, specificity 71%23 25 | 4 |

| *Level of evidence not reported as specific references could not be found. | ||

| AP, anteroposterior; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging | ||

Magnetic resonance imaging

Advanced imaging may be required when initial conservative therapy is not effective or x-ray findings are unrevealing. Although computed tomography (CT) scan and bone scan have roles in the evaluation of some hip disorders, MRI has emerged as the study of choice in diagnosing hip pathology, especially in athletes.13

MRI offers valuable information regarding occult bony and cartilage injury such as stress fractures, avascular necrosis, and osteoarthritis, as well as soft tissue abnormalities such as muscle tears and bursitis. In a retrospective study of patients with suspected hip fracture but negative plain film results, MRI showed occult femoral fractures in 37% of patients, occult pelvic fractures in 23%, and associated soft-tissue abnormalities such as muscle edema and hematoma or joint effusion in 74%.26

Other imaging tests

In cases of suspected labral or intra-articular pathology, MR arthrography, anesthetic intraarticular injection and examination under local anesthesia, or diagnostic arthroscopy may be needed.16 These are relatively new techniques that help diagnose disorders not previously recognized.

Treatment

Depending on the presumed cause of pain, treatment options include activity modification, acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), analgesics, corticosteroid injections, physical therapy, and, if necessary, walking support.

Osteoarthritis. When symptoms persist despite conservative treatment for osteoarthritis, fluoroscopically guided intra-articular injection of a corticosteroid—or, more recently, viscosupplementation with hyaluronic acid preparations—may be useful in decreasing pain, and delaying or possibly avoiding hip arthroplasty (LOE=4).27-29

Greater trochanteric bursitis. Corticosteroid injection is also helpful and easily performed by a family physician for treatment of greater trochanteric bursitis, with 77% of patients improving in 1 week, and 61% with sustained improvement at 26 weeks (LOE=4).30

Iliopsoas bursitis. This disorder has been shown to respond to a physical therapy program emphasizing hip rotation strengthening (LOE=4).31 However, recalcitrant cases may require intrabursal injection or surgical lengthening of the iliopsoas muscle (LOE=4).32,33

Meralgia paresthetica. This condition may respond to an injection of corticosteroid adjacent to the anterior superior iliac spine near the emergence of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve.10 In cases of suspected sacroiliac joint dysfunction, manipulative therapy was shown to provide short-term improvement.34

When To Refer

When hip pain is refractory to conventional treatment, consider referral to a specialist, such as a sports medicine specialist, physiatrist, rheumatologist, or orthopedic surgeon.

1. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Hyattsville, Md: National Center for Health Statistics; 1995. CHS CD-ROM series 13, no. 11. Issued July 1997.

2. van Mechelen W. Running injuries. A review of the epidemiological literature. Sports Med 1992;14:320-335.

3. Christmas C, Crespo CJ, Franckowiak SC, Bathon JM, Bartlett SJ, Andersen RE. How common is hip pain among older adults? Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Fam Pract 2002;51:345-348.

4. Scopp JM, Moorman CT. The assessment of athletic hip injury. Clin Sports Med 2001;20:647-659.

5. Lamberts H, Brouwer HJ, Marinus AFM, Hofmans-Okkes IM. The use of ICPC in the Transition project.Episode-oriented epidemiology in general practice. In: Lamberts H, Wood M, Hofmans-Okkes IM, eds. International Classification of Primary Care in the European Community. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1993;45-93.

6. Birrell F, Croft P, Cooper C, Hosie G, Macfarlane GJ, Silman A. Radiographic change is common in new presenters in primary care with hip pain. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2000;39:772-775.

7. Hickman JM, Peters CL. Hip pain in the young adult: diagnosis and treatment of disorders of the acetabular labrum and acetabular dysplasia. Am J Orthop 2001;30:459-467.

8. Shbeeb MI, Matteson EL. Trochanteric bursitis (greater trochanter pain syndrome). Mayo Clin Proc 1996;71:565-569.

9. Bird PA, Oakley SP, Shnier R, Kirkham BW. Prospective evaluation of magnetic resonance imaging and physical examination findings in patients with greater trochanteric pain syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 2001;44:2138-2145.

10. Jones RK. Meralgia paresthetica as a cause of leg discomfort. Can Med Assoc J 1974;111:541-542.

11. Individual Clinical Guidelines: Hip Pain (non-traumatic) Phase 1. Version 1.0. Rosemont, Ill: Department of Research and Scientific Affairs, American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 1996.

12. Birrell F, Croft P, Cooper C, Hosie G, Macfarlane G, Silman A; PCR Hip Study Group. Predicting radiographic hip osteoarthritis from range of movement. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2001;40:506-512.

13. Shin AY, Morin WD, Gorman JD, Jones SB, Lapinsky AS. The superiority of magnetic resonance imaging in differentiating the cause of hip pain in endurance athletes. Am J Sports Med 1996;24:168-176.

14. McCarthy JC, Busconi B. The role of hip arthroscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of hip disease. Orthopedics 1995;18:753-756.

15. Grossman MG, Ducey SA, Nadler SS, Levy AS. Meralgia paresthetica: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2001;9:336-344.

16. Mitchell B, McCrory P, Brukner P, O'Donnell J, Colson E, Howells R. Hip joint pathology: clinical presentation and correlation between magnetic resonance arthrography, ultrasound, and arthroscopic findings in 25 consecutive cases. Clin J Sport Med 2003;13:152-156.

17. Croft P, Cooper C, Coggon D. Case definition of hip osteoarthritis in epidemiologic studies. J Rheumatol 1994;21:591-592.

18. Harper MC, Schaberg JE, Allen WC. Primary iliopsoas bursography in the diagnosis of disorders of the hip. Clin Orthop 1987;221:238-241.

19. Vaccaro JP, Sauser DD, Beals RK. Iliopsoas bursa imaging: efficacy in depicting abnormal iliopsoas tendon motion in patients with internal snapping hip syndrome. Radiology 1995;197:853-856.

20. Janzen DL, Partridge E, Logan PM, Connell DG, Duncan CP. The snapping hip: clinical and imaging findings in transient subluxation of the iliopsoas tendon. Can Assoc Radiol J 1996;47:202-208.

21. Seror P. Lateral femoral cutaneous nerve conduction v MRI may be required when conservative therapy is not effective or x-rays are unrevealing somatosensory evoked potentials for electrodiagnosis of meralgia paresthetica. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 1999;78:313-316.

22. Mitchell DG, Rao VM, Dalinka MK, et al. Femoral head avascular necrosis: correlation of MR imaging, radiographic staging, radionuclide imaging, and clinical findings. Radiology 1987;162:709-715.

23. Czerny C, Hofmann S, Neuhold A, et al. Lesions of the acetabular labrum: accuracy of MR imaging and MR arthrography in detection and staging. Radiology 1996;200:225-230.

24. Czerny C, Hofmann S, Urban M, et al. MR arthrography of the adult acetabular capsular-labral complex: correlation with surgery and anatomy. AJR Am J Roentengol 1999;173:345-349.

25. Petersilge DA, Haque MA, Petersilge WJ, Lewin JS, Lieberman JM, Buly R. Acetabular labral tears: evaluation with MR arthrography. Radiology 1996;200:231-235.

26. Bogost GA, Lizerbram EK, Crues JV. MR imaging in evaluation of suspected hip fracture: frequency of unsuspected bone and soft-tissue injury. Radiology 1995;197:263-267.

27. Creamer P. Intra-articular corticosteroid treatment in osteoarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 1999;11:417-421.

28. Migliore A, Martin LS, Alimonti A, Valente C, Tormenta S. Efficacy and safety of viscosupplementation by ultrasound-guided intra-articular injection in osteoarthrits of the hip. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2003;11:305-306.

29. Brocq O, Tran G, Breuil V, Grisot C, Flory P, Euller-Ziegler L. Hip osteoarthritis: short-term efficacy and safety of viscosupplementation by hylan G-F 20. An open-label study in 22 patients. Joint Bone Spine 2002;69:388-391.

30. Shbeeb MI, O'Duffy JD, Michet CJ, O'Fallon WM, Matteson EL. Evaluation of glucocorticosteroid injection for the treatment of trochanteric bursitis. J Rheumatol 1996;23:2104-2106.

31. Johnston CA, Lindsay DM, Wiley JP. Treatment of iliopsoas syndrome with a hip rotation strengthening program: a retrospective case series. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1999;29:218-224.

32. Johnston CA, Wiley JP, Lindsay DM, Wiseman DA. Iliopsoas bursitis and tendonitis. A review. Sports Med 1998;25:271-283.

33. Gruen GS, Scioscia TN, Lowenstein JE. The surgical treatment of internal snapping hip. Am J Sports Med 2002;30:607-613.

34. Cibulka MT, Delitto A. A comparison of two different methods to treat hip pain in runners. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1993;17:172-176.

1. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Hyattsville, Md: National Center for Health Statistics; 1995. CHS CD-ROM series 13, no. 11. Issued July 1997.

2. van Mechelen W. Running injuries. A review of the epidemiological literature. Sports Med 1992;14:320-335.

3. Christmas C, Crespo CJ, Franckowiak SC, Bathon JM, Bartlett SJ, Andersen RE. How common is hip pain among older adults? Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Fam Pract 2002;51:345-348.

4. Scopp JM, Moorman CT. The assessment of athletic hip injury. Clin Sports Med 2001;20:647-659.

5. Lamberts H, Brouwer HJ, Marinus AFM, Hofmans-Okkes IM. The use of ICPC in the Transition project.Episode-oriented epidemiology in general practice. In: Lamberts H, Wood M, Hofmans-Okkes IM, eds. International Classification of Primary Care in the European Community. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1993;45-93.

6. Birrell F, Croft P, Cooper C, Hosie G, Macfarlane GJ, Silman A. Radiographic change is common in new presenters in primary care with hip pain. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2000;39:772-775.

7. Hickman JM, Peters CL. Hip pain in the young adult: diagnosis and treatment of disorders of the acetabular labrum and acetabular dysplasia. Am J Orthop 2001;30:459-467.

8. Shbeeb MI, Matteson EL. Trochanteric bursitis (greater trochanter pain syndrome). Mayo Clin Proc 1996;71:565-569.

9. Bird PA, Oakley SP, Shnier R, Kirkham BW. Prospective evaluation of magnetic resonance imaging and physical examination findings in patients with greater trochanteric pain syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 2001;44:2138-2145.

10. Jones RK. Meralgia paresthetica as a cause of leg discomfort. Can Med Assoc J 1974;111:541-542.

11. Individual Clinical Guidelines: Hip Pain (non-traumatic) Phase 1. Version 1.0. Rosemont, Ill: Department of Research and Scientific Affairs, American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 1996.

12. Birrell F, Croft P, Cooper C, Hosie G, Macfarlane G, Silman A; PCR Hip Study Group. Predicting radiographic hip osteoarthritis from range of movement. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2001;40:506-512.

13. Shin AY, Morin WD, Gorman JD, Jones SB, Lapinsky AS. The superiority of magnetic resonance imaging in differentiating the cause of hip pain in endurance athletes. Am J Sports Med 1996;24:168-176.

14. McCarthy JC, Busconi B. The role of hip arthroscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of hip disease. Orthopedics 1995;18:753-756.

15. Grossman MG, Ducey SA, Nadler SS, Levy AS. Meralgia paresthetica: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2001;9:336-344.

16. Mitchell B, McCrory P, Brukner P, O'Donnell J, Colson E, Howells R. Hip joint pathology: clinical presentation and correlation between magnetic resonance arthrography, ultrasound, and arthroscopic findings in 25 consecutive cases. Clin J Sport Med 2003;13:152-156.

17. Croft P, Cooper C, Coggon D. Case definition of hip osteoarthritis in epidemiologic studies. J Rheumatol 1994;21:591-592.

18. Harper MC, Schaberg JE, Allen WC. Primary iliopsoas bursography in the diagnosis of disorders of the hip. Clin Orthop 1987;221:238-241.

19. Vaccaro JP, Sauser DD, Beals RK. Iliopsoas bursa imaging: efficacy in depicting abnormal iliopsoas tendon motion in patients with internal snapping hip syndrome. Radiology 1995;197:853-856.

20. Janzen DL, Partridge E, Logan PM, Connell DG, Duncan CP. The snapping hip: clinical and imaging findings in transient subluxation of the iliopsoas tendon. Can Assoc Radiol J 1996;47:202-208.

21. Seror P. Lateral femoral cutaneous nerve conduction v MRI may be required when conservative therapy is not effective or x-rays are unrevealing somatosensory evoked potentials for electrodiagnosis of meralgia paresthetica. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 1999;78:313-316.

22. Mitchell DG, Rao VM, Dalinka MK, et al. Femoral head avascular necrosis: correlation of MR imaging, radiographic staging, radionuclide imaging, and clinical findings. Radiology 1987;162:709-715.

23. Czerny C, Hofmann S, Neuhold A, et al. Lesions of the acetabular labrum: accuracy of MR imaging and MR arthrography in detection and staging. Radiology 1996;200:225-230.

24. Czerny C, Hofmann S, Urban M, et al. MR arthrography of the adult acetabular capsular-labral complex: correlation with surgery and anatomy. AJR Am J Roentengol 1999;173:345-349.

25. Petersilge DA, Haque MA, Petersilge WJ, Lewin JS, Lieberman JM, Buly R. Acetabular labral tears: evaluation with MR arthrography. Radiology 1996;200:231-235.

26. Bogost GA, Lizerbram EK, Crues JV. MR imaging in evaluation of suspected hip fracture: frequency of unsuspected bone and soft-tissue injury. Radiology 1995;197:263-267.

27. Creamer P. Intra-articular corticosteroid treatment in osteoarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 1999;11:417-421.

28. Migliore A, Martin LS, Alimonti A, Valente C, Tormenta S. Efficacy and safety of viscosupplementation by ultrasound-guided intra-articular injection in osteoarthrits of the hip. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2003;11:305-306.

29. Brocq O, Tran G, Breuil V, Grisot C, Flory P, Euller-Ziegler L. Hip osteoarthritis: short-term efficacy and safety of viscosupplementation by hylan G-F 20. An open-label study in 22 patients. Joint Bone Spine 2002;69:388-391.

30. Shbeeb MI, O'Duffy JD, Michet CJ, O'Fallon WM, Matteson EL. Evaluation of glucocorticosteroid injection for the treatment of trochanteric bursitis. J Rheumatol 1996;23:2104-2106.

31. Johnston CA, Lindsay DM, Wiley JP. Treatment of iliopsoas syndrome with a hip rotation strengthening program: a retrospective case series. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1999;29:218-224.

32. Johnston CA, Wiley JP, Lindsay DM, Wiseman DA. Iliopsoas bursitis and tendonitis. A review. Sports Med 1998;25:271-283.

33. Gruen GS, Scioscia TN, Lowenstein JE. The surgical treatment of internal snapping hip. Am J Sports Med 2002;30:607-613.

34. Cibulka MT, Delitto A. A comparison of two different methods to treat hip pain in runners. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1993;17:172-176.