User login

Dyspareunia is persistent or recurrent pain before, during, or after sexual contact and is not limited to cisgender individuals or vaginal intercourse.1-3 With a prevalence as high as 45% in the United States,2-5 it is one of the most common complaints in gynecologic practices.5,6

Causes and contributing factors

There are many possible causes of dyspareunia.2,4,6 While some patients have a single cause, most cases are complex, with multiple overlapping causes and maintaining factors.4,6 Identifying each contributing factor can help you appropriately address all components.

Physical conditions. The range of physical contributors to dyspareunia includes inflammatory processes, structural abnormalities, musculoskeletal dysfunctions, pelvic organ disorders, injuries, iatrogenic effects, infections, allergic reactions, sensitization, hormonal changes, medication effects, adhesions, autoimmune disorders, and other pain syndromes (TABLE 12-4,6-11).

Inadequate arousal. One of the primary causes of pain during vaginal penetration is inadequate arousal and lubrication.1,2,9-11 Arousal is the phase of the sexual response cycle that leads to genital tumescence and prepares the genitals for sexual contact through penile/clitoral erection, vaginal engorgement, and lubrication, which prevents pain and enhances pleasurable sensation.9-11

While some physical conditions can lead to an inability to lubricate, the most common causes of inadequate lubrication are psychosocial-behavioral, wherein patients have the same physical ability to lubricate as patients without genital pain but do not progress through the arousal phase.9-11 Behavioral factors such as inadequate or ineffective foreplay can fail to produce engorgement and lubrication, while psychosocial factors such as low attraction to partner, relationship stressors, anxiety, or low self-esteem can have an inhibitory effect on sexual arousal.1,2,9-11 Psychosocial and behavioral factors may also be maintaining factors or consequences of dyspareunia, and need to be assessed and treated.1,2,9-11

Psychological trauma. Exposure to psychological traumas and the development of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have been linked with the development of pain disorders in general and dyspareunia specifically. Most patients seeking treatment for chronic pain disorders have a history of physical or sexual abuse.12 Changes in physiologic processes (eg, neurochemical, endocrine) that occur with PTSD interfere with the sexual response cycle, and sexual traumas specifically have been linked with pelvic floor dysfunction.13,14 Additionally, when PTSD is caused by a sexual trauma, even consensual sexual encounters can trigger flashbacks, intrusive memories, hyperarousal, and muscle tension that interfere with the sexual response cycle and contribute to genital pain.13

Vaginismus is both a physiologic and psychological contributor to dyspareunia.1,2,4 Patients experiencing pain can develop anxiety about repeated pain and involuntarily contract their pelvic muscles, thereby creating more pain, increasing anxiety, decreasing lubrication, and causing pelvic floor dysfunction.1-4,6 Consequently, all patients with dyspareunia should be assessed and continually monitored for symptoms of vaginismus.

Continue to: Anxiety

Anxiety. As with other pain disorders, anxiety develops around pain triggers.10,15 When expecting sexual activity, patients can experience extreme worry and panic attacks.10,15,16 The distress of sexual encounters can interfere with physiologic arousal and sexual desire, impacting all phases of the sexual response cycle.1,2

Relationship issues. Difficulty engaging in or avoidance of sexual activity can interfere with romantic relationships.2,10,16 Severe pain or vaginismus contractions can prevent penetration, leading to unconsummated marriages and an inability to conceive through intercourse.10 The distress surrounding sexual encounters can precipitate erectile dysfunction in male partners, or partners may continue to demand sexual encounters despite the patient’s pain, further impacting the relationship and heightening sexual distress.10 These stressors have led to relationships ending, patients reluctantly agreeing to nonmonogamy to appease their partners, and patients avoiding relationships altogether.10,16

Devalued self-image. Difficulties with sexuality and relationships impact the self-image of patients with dyspareunia. Diminished self-image may include feeling “inadequate” as a woman and as a sexual partner, or feeling like a “failure.”16 Women with dyspareunia often have more distress related to their body image, physical appearance, and genital self-image than do women without genital pain.17 Feeling resentment toward their body, or feeling “ugly,” embarrassed, shamed, “broken,” and “useless” also contribute to increased depressive symptoms found in patients with dyspareunia.16,18

Making the diagnosis

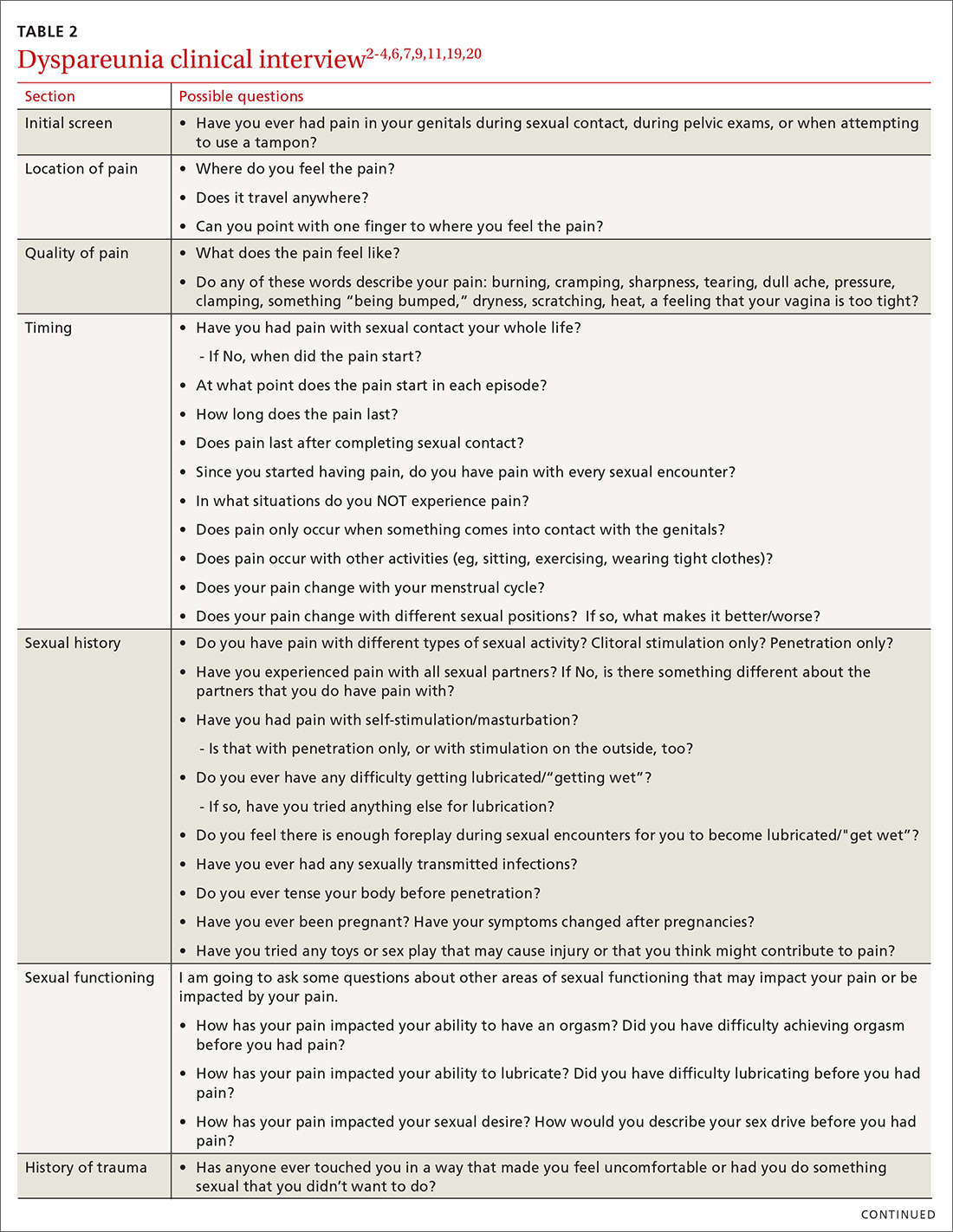

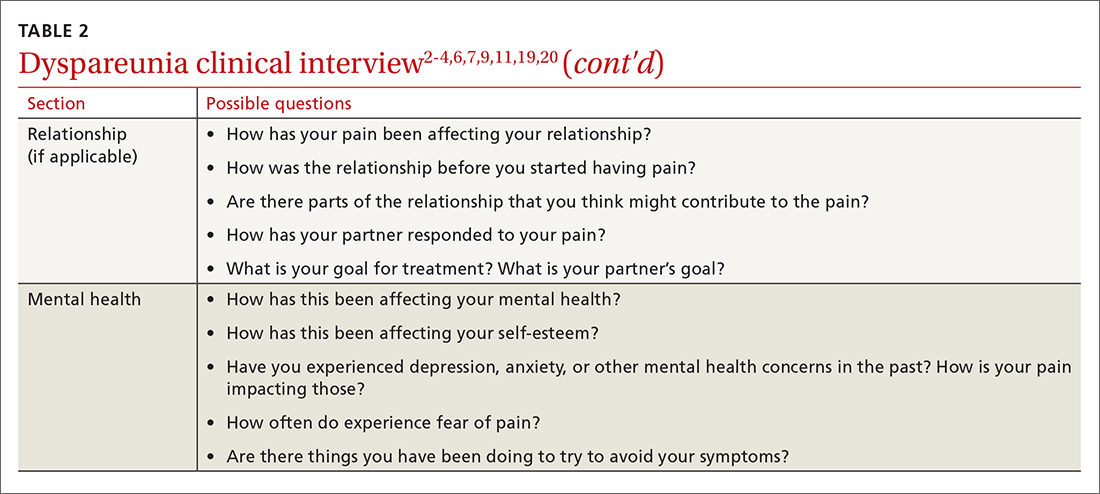

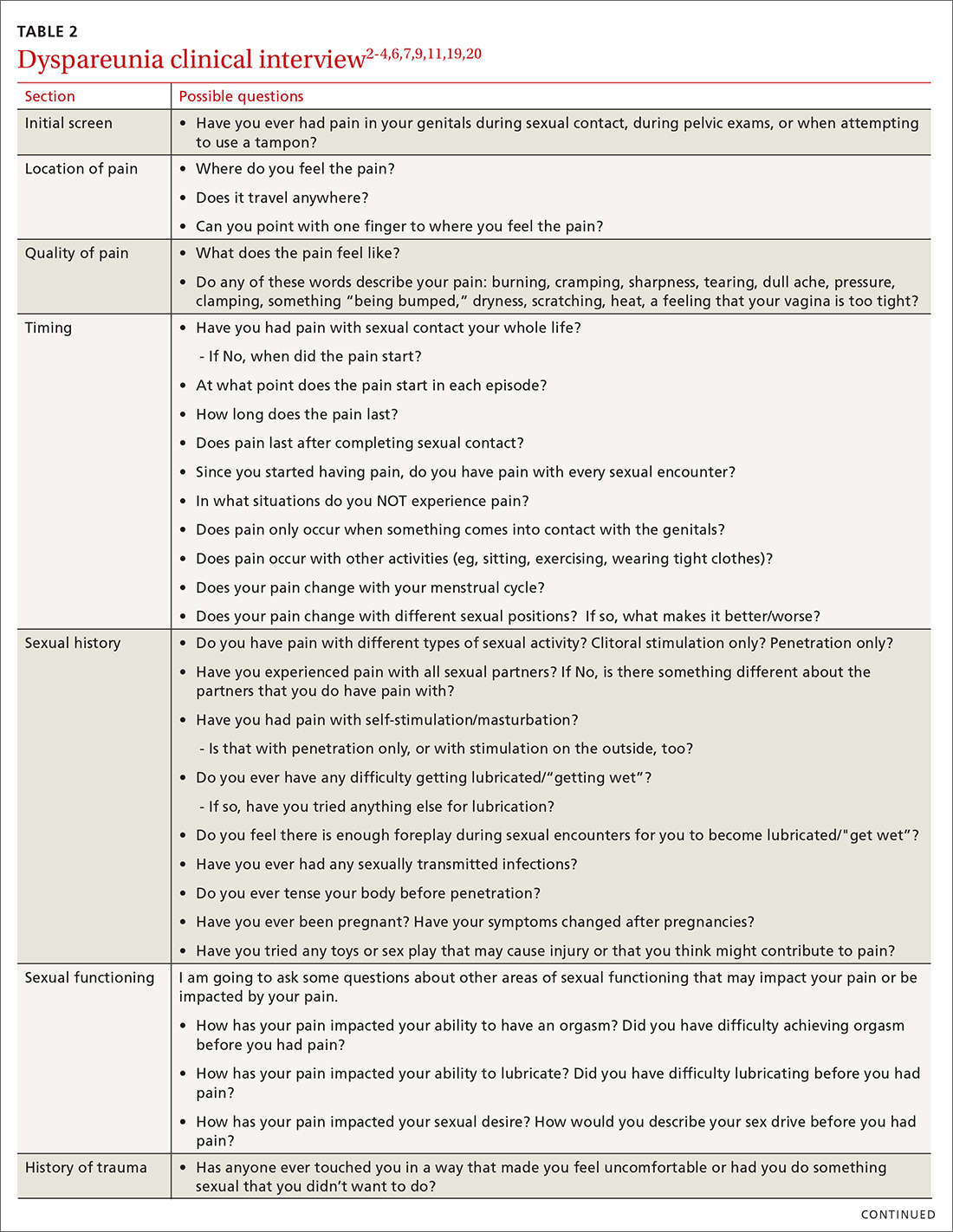

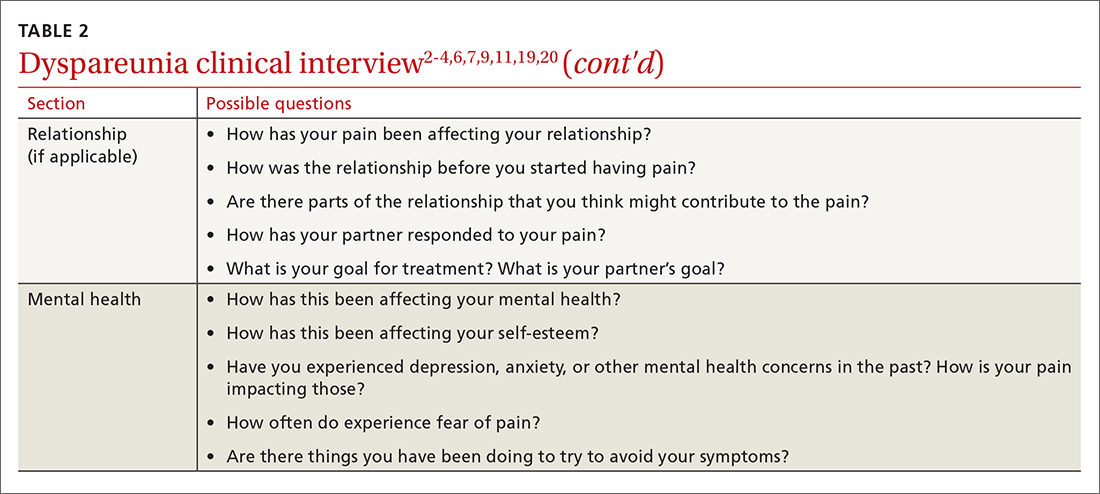

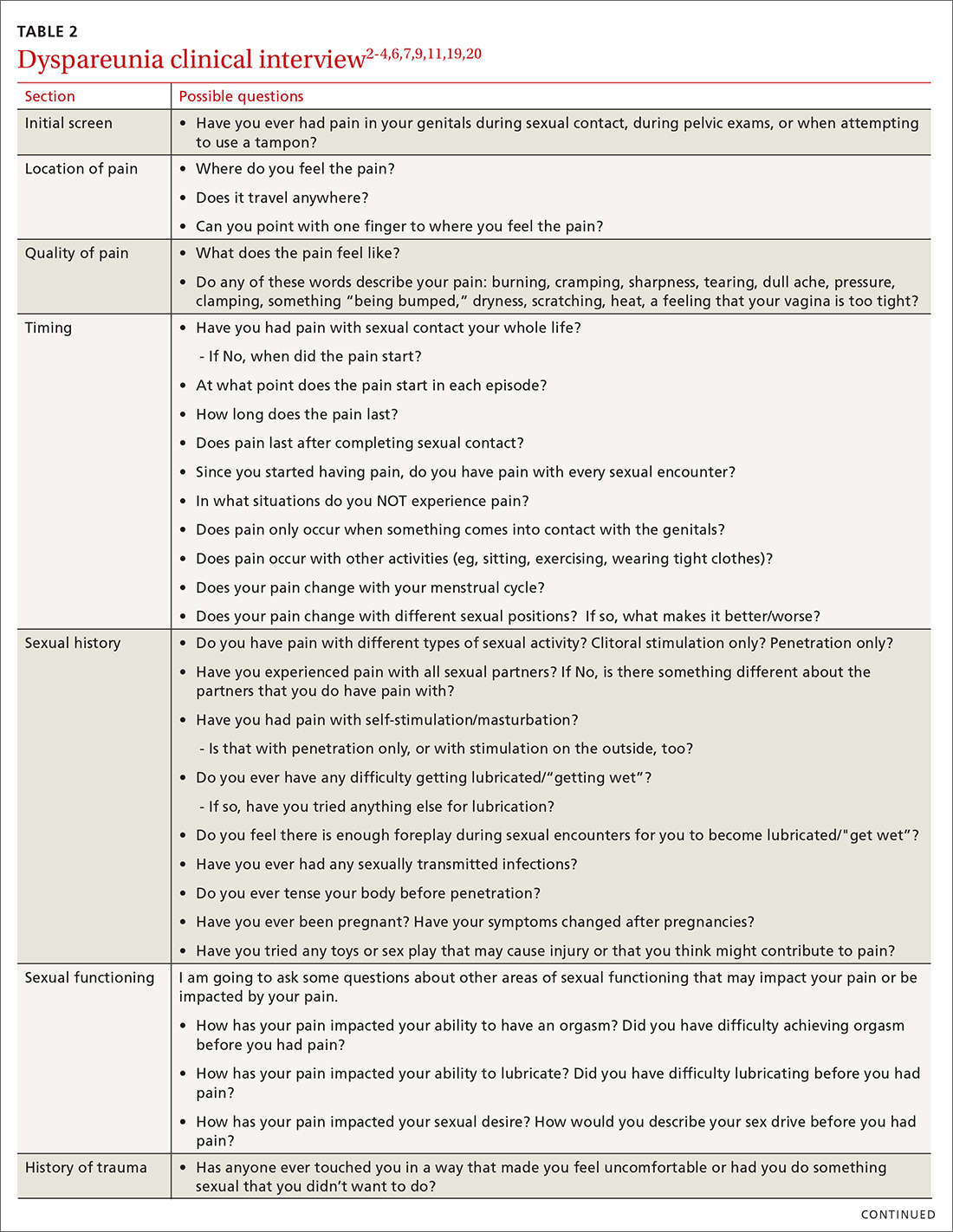

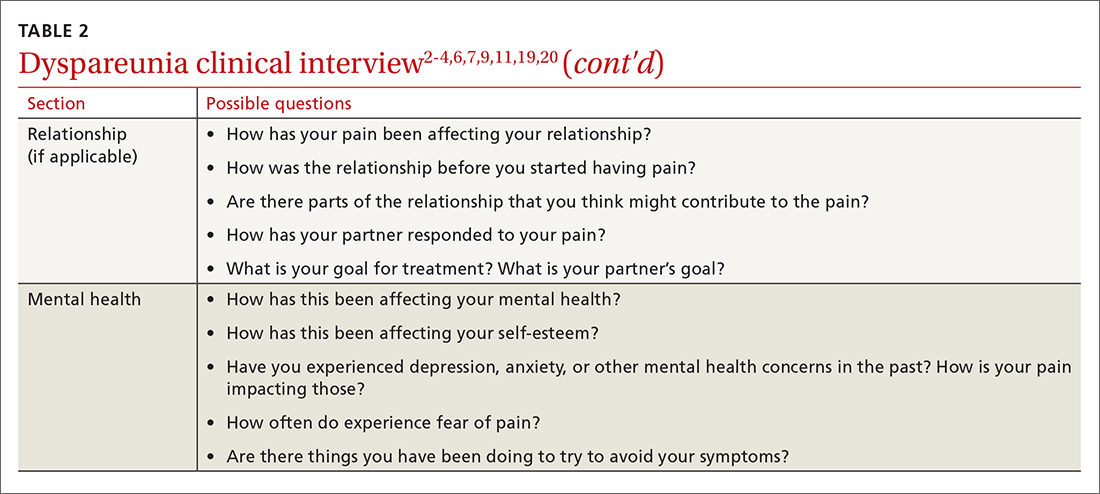

Most patients do not report symptoms unless directly asked2,7; therefore, it is recommended that all patients be screened as a part of an initial intake and before any genital exam (TABLE 22-4,6,7,9,11,19,20).4,7,21 If this screen is positive, a separate appointment may be needed for a thorough evaluation and before any attempt is made at a genital exam.4,7

Items to include in the clinical interview

Given the range of possible causes of dyspareunia and its contributing factors and symptoms, a thorough clinical interview is essential. Begin with a review of the patient’s complete medical and surgical history to identify possible known contributors to genital pain.4 Pregnancy history is of particular importance as the prevalence of postpartum dyspareunia is 35%, with risk being greater for patients who experienced dyspareunia symptoms before pregnancy.22

Knowing the location and quality of pain is important for differentiating between possible diagnoses, as is specifying dyspareunia as lifelong or acquired, superficial or deep, and primary or secondary.1-4,6 Confirm the specific location(s) of pain—eg, at the introitus, in the vestibule, on the labia, in the perineum, or near the clitoris.2,4,6 A diagram or model may be needed to help patients to localize pain.4

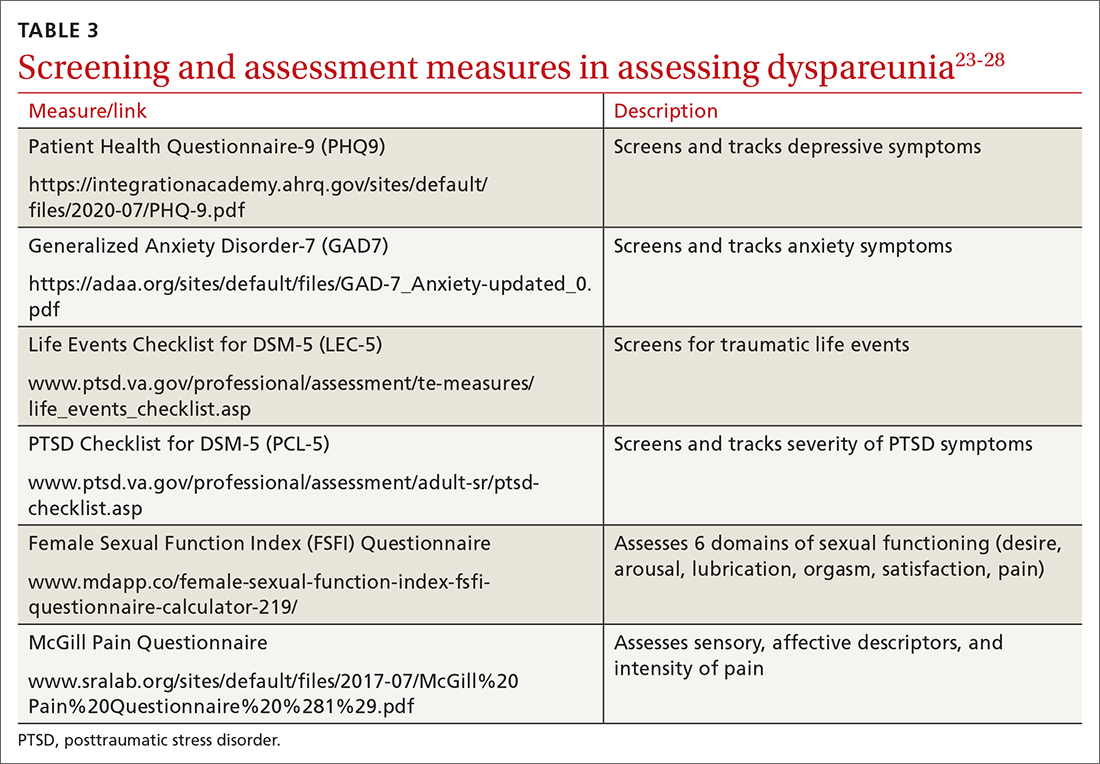

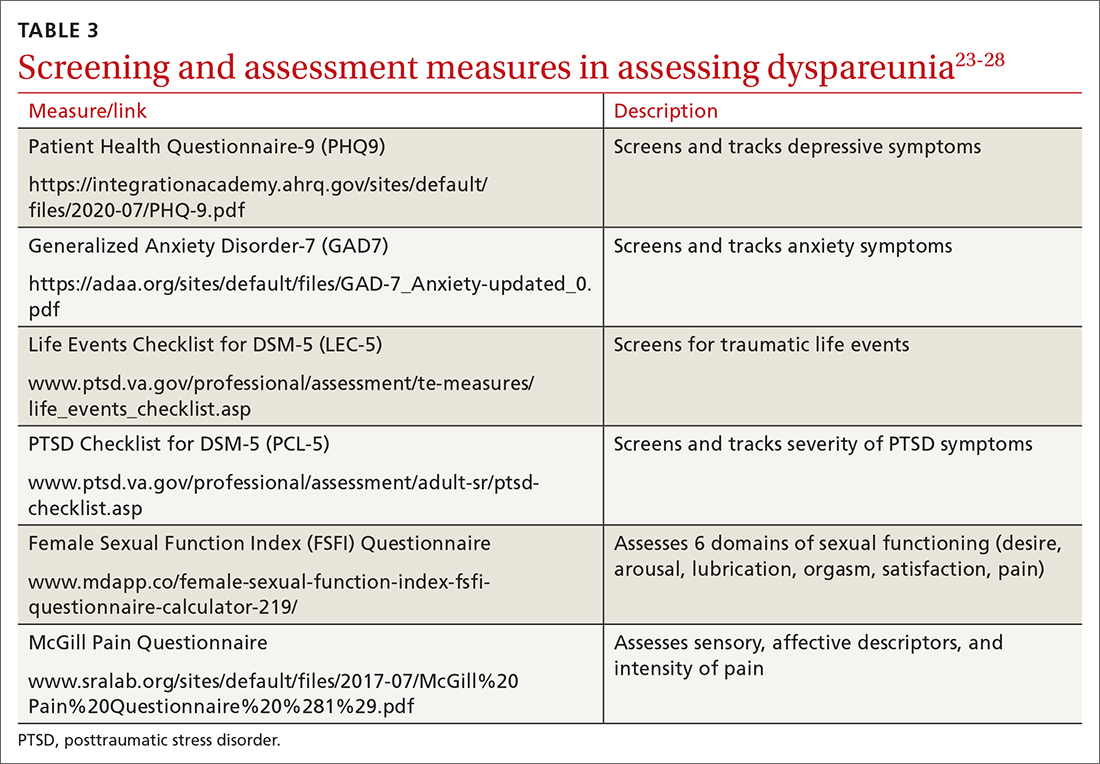

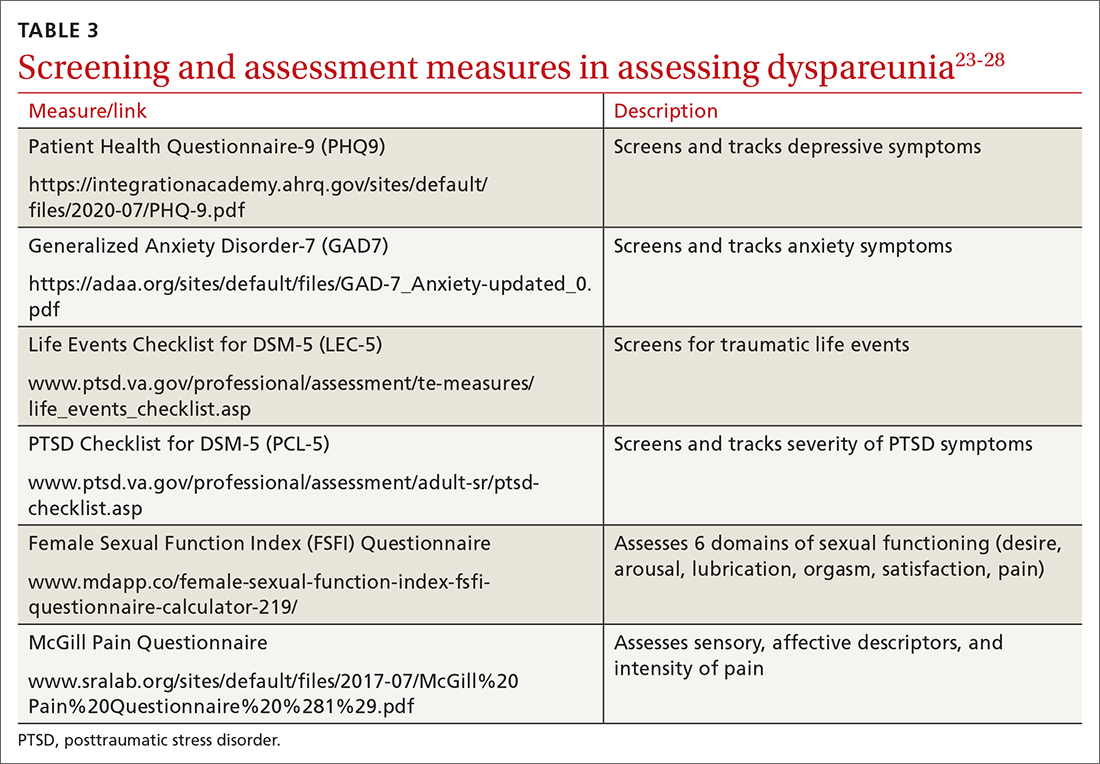

To help narrow the differential, include the following elements in your assessment: pain quality, timing (eg, initial onset, episode onset, episode duration, situational triggers), alleviating factors, symptoms in surrounding structures (eg, bladder, bowel, muscles, bones), sexual history, other areas of sexual functioning, history of psychological trauma, relationship effects, and mental health (TABLE 22-4,6,7,9,11,19,20 and Table 323-28). Screening for a history of sexual trauma is particularly important, as a recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that women with a history of sexual assault had a 42% higher risk of gynecologic problems overall, a 74% higher risk of dyspareunia, and a 71% higher risk of vaginismus than women without a history of sexual assault.29 Using measures such as the Female Sexual Function Index or the McGill Pain Questionnaire can help patients more thoroughly describe their symptoms (TABLE 323-28).3

Continue to: Guidelines for the physical exam

Guidelines for the physical exam

Before the exam, ensure the patient has not used any topical genital treatment in the past 2 weeks that may interfere with sensitivity to the exam.4 To decrease patients’ anxiety about the exam, remind them that they can stop the exam at any time.7 Also consider offering the use of a mirror to better pinpoint the location of pain, and to possibly help the patient learn more about her anatomy.2,7

Begin the exam by palpating surrounding areas that may be involved in pain, including the abdomen and musculoskeletal features.3,6,19 Next visually inspect the external genitalia for lesions, abrasions, discoloration, erythema, or other abnormal findings.2,3,6 Ask the patient for permission before contacting the genitals. Because the labia may be a site of pain, apply gentle pressure in retracting it to fully examine the vestibule.6,7 Contraction of the pelvic floor muscles during approach or initial palpation could signal possible vaginismus.4

After visual inspection of external genitalia, use a cotton swab to map the vulva and vestibule in a clockwise fashion to precisely identify any painful locations.2-4,6 If the patient’s history of pain has been intermittent, it’s possible that the cotton swab will not elicit pain on the day of the initial exam, but it may on other days.4

Begin the internal exam by inserting a single finger into the first inch of the vagina and have the patient squeeze and release to assess tenderness, muscle tightness, and control.2,6 Advance the finger further into the vagina and palpate clockwise, examining the levator muscles, obturator muscles, rectum, urethra, and bladder for abnormal tightness or reproduction of pain.2,4,6 Complete a bimanual exam to evaluate the pelvic organs and adnexa.2,4 If indicated, a more thorough evaluation of pelvic floor musculature can be performed by a physical therapist or gynecologist who specializes in pelvic pain.2-4

If the patient consents to further evaluation, consider using a small speculum, advanced slowly, for further internal examination, noting any lesions, abrasions, discharge, ectropion, or tenderness.2-4,7 A rectal exam may also be needed in cases of deep dyspareunia.6 Initial work-up may include a potassium hydroxide wet prep, sexually transmitted infection testing, and pelvic ultrasound.2,4 In some cases, laparoscopy or biopsy may be needed.2,4

Treatments for common causes

Treatment often begins with education about anatomy, to help patients communicate about symptoms and engage more fully in their care.3 Additional education may be needed on genital functioning and the necessity of adequate stimulation and lubrication prior to penetration.1,2,9-11 A discussion of treatments for the wide range of possible causes of dyspareunia is outside the scope of this article. However, some basic behavioral changes may help patients address some of the more common contributing factors.

For example, if vaginal infection is suspected, advise patients to discontinue the use of harsh soaps, known vaginal irritants (eg, perfumed products, bath additives), and douches.3 Recommend using only preservative- and alcohol-free lubricants for sexual contact, and avoiding lubricants with added functions (eg, warming).3 It’s worth noting that avoidance of tight clothing and thong underwear due to possible risk for infections may not be necessary. A recent study found that women who frequently wore thong underwear (more than half of the time) were no more likely to develop urinary tract infections, yeast vaginitis, or bacterial vaginosis than those who avoid such items.30 However, noncotton underwear fabric, rather than tightness, was associated with yeast vaginitis30; therefore, patients may want to consider using only breathable underwear.3

Continue to: Medication

Medication. Medication may be used to treat the underlying contributing conditions or the symptom of pain directly. Some common options are particularly important for patients whose dyspareunia does not have an identifiable cause. These medications include anti-inflammatory agents, topical anesthetics, tricyclic antidepressants, and hormonal treatments.2-4 Since effectiveness varies based on subtypes of pain, select a medication according to the location, timing, and hypothesized mechanism of pain.3,31,32

Medication for deep pain. A meta-analysis and systematic review found that patients with some types of chronic pelvic pain with pain deep in the vagina or pelvis experienced greater than 50% reduction in pain using medroxyprogesterone acetate compared with placebo.33 Other treatments for deep pain depend on physical exam findings.

Medication for superficial pain. Many remedies have been tried, with at least 26 different treatments for vulvodynia pain alone.16 Only some of these treatments have supporting evidence. For patients with vulvar pain, an intent-to-treat RCT found that patients using a topical steroid experienced a 23% reduction in pain from pre-treatment to 6-month follow-up.32

Surgery is also effective for vulvar pain.34,35 For provoked vestibulodynia (in which pain is localized to the vestibule and triggered by contact with the vulva), or vulvar vestibulitis, RCTs have found that vestibulectomy has stronger effects on pain than other treatments,31,35 with a 53% reduction in pain during intercourse and a 70% reduction in vestibular pain overall.35 However, while vestibulectomy is effective for provoked vestibulodynia, it is not recommended for generalized vulvodynia, in which pain is diffuse across the vulva and occurs without vulvar contact.34

Unsupported treatments. A number of other treatments have not yet been found effective. Although lidocaine for vulvar pain is often used, RCTs have not found any significant reduction in symptoms, and a double-blind RCT found that lidocaine ointment actually performed worse than placebo.31,34 Similarly, oral tricyclics have not been found to decrease vulvar pain more than placebo in double-blind studies.31,34 Furthermore, a meta-analysis of RCTs comparing treatments with placebo for vestibular pain found no significant decrease in dyspareunia for topical conjugated estrogen, topical lidocaine, oral desipramine, oral desipramine with topical lidocaine, laser therapy, or transcranial direct current.32

Tx risks to consider. Risks and benefits of dyspareunia treatment options should be thoroughly weighed and discussed with the patient.2-4 Vestibulectomy, despite reducing pain for many patients, has led to increased pain for 9% of patients who underwent the procedure.35 Topical treatments may lead to allergic reactions, inflammation, and worsening of symptoms,4 and hormonal treatments have been found to increase the risk of weight gain and bloating and are not appropriate for patients trying to conceive.33

Coordinate care with other providers

While medications and surgery can reduce pain, they have not been shown to improve other aspects of sexual functioning such as sexual satisfaction, frequency of sexual intercourse, or overall sense of sexual functioning.35 Additionally, pain reduction does not address muscle tension, anxiety, self-esteem, and relationship problems. As a result, a multidisciplinary approach is generally needed.3,4,32,33

Continue to: Physical therapists

Physical therapists. Pelvic floor physical therapists are often members of the dyspareunia treatment team and can provide a thorough evaluation and treatment of pelvic floor disorders.2-4 An RCT with intent-to-treat analysis found that pain was reduced by 71% following pelvic floor physical therapy.36 Another RCT found that 90% of patients reported a clinically meaningful decrease in pain with pelvic floor physical therapy.37 In addition to addressing pain, pelvic floor physical therapy has also been found to improve sexual functioning, sexual satisfaction, distress, and patient perception of improvement.34,36,37

Behavioral health specialists. Psychotherapists, especially those trained in sex therapy, couples therapy, or cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), are also typically on the treatment team. Multiple RCTs have found evidence of CBT’s effectiveness in the direct treatment of dyspareunia pain. Bergeron et al35 found a 37.5% reduction in vulvar vestibulitis pain intensity during intercourse after patients completed group CBT. Another intent-to-treat RCT found that patients receiving CBT experienced more pain reduction (~ 30%) than patients who were treated with a topical steroid.38

In addition to having a direct impact on pain, CBT has also been found to have a clinically and statistically significant positive impact on other aspects of sexual experience, such as overall sexuality, self-efficacy, overall sexual functioning, frequency of intercourse, and catastrophizing.34,38 A recent meta-analysis of RCTs found that about 80% of vaginismus patients were able to achieve penetrative intercourse after treatment with behavioral sex therapy or CBT.39 This success rate was not exceeded by physical or surgical treatments.39

When PTSD is thought to be a contributing factor, trauma therapy will likely be needed in addition to treatments for dyspareunia. First-line treatments for PTSD include cognitive processing therapy, prolonged exposure, trauma-focused CBT, and cognitive therapy.40

Psychotherapists can also help patients reduce anxiety, reintroduce sexual contact without triggering pain or anxiety, address emotional and self-esteem effects of dyspareunia, address relationship issues, and refocus sexual encounters on pleasure rather than pain avoidance.2-4 Despite patient reports of high treatment satisfaction following therapy,38 many patients may initially lack confidence in psychotherapy as a treatment for pain35 and may need to be educated on its effectiveness and multidimensional benefits.

Gynecologists. Often a gynecologist with specialization in pelvic pain is an essential member of the team for diagnostic clarification, recommendation of treatment options, and performance of more advanced treatments.2,3 If pain has become chronic, the patient may also benefit from a pain management team and support groups.2,3

Follow-up steps

Patients who screen negative for dyspareunia should be re-screened periodically. Continue to assess patients diagnosed with dyspareunia for vaginismus symptoms (if they are not initially present) to ensure that the treatment plan is appropriately adjusted. Once treatment has begun, ask about adverse effects and confidence in the treatment plan to minimize negative impacts on treatment adherence and to anticipate a need for a change in the treatment approach.31,35 In addition to tracking treatment effects on pain, continue to assess for patient-centered outcomes such as emotional functioning, self-esteem, and sexual and relationship satisfaction.34 The Female Sexual Function Index can be a useful tool to track symptoms.27,34

Finally, patients who do not experience sufficient improvement in symptoms and functioning with initial treatment may need continued support and encouragement. Given the broad range of contributing factors and the high number of potential treatments, patients may find hope in learning that multiple other treatment options may be available.

CORRESPONDENCE

Adrienne A. Williams, PhD, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Illinois at Chicago College of Medicine, 1919 W Taylor Street, MC 663, Chicago, IL 60612; awms@uic.edu

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th Ed. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

2. Seehusen DA, Baird DC, Bode DV. Dyspareunia in women. Am Fam Phys. 2014;90:465-470.

3. Sorensen J, Bautista KE, Lamvu G, et al. Evaluation and treatment of female sexual pain: a clinical review. Cureus. 2018;10:e2379.

4. MacNeill C. Dyspareunia. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2006;33:565-77.

5. Latthe P, Latthe M, Say L, et al. WHO systematic review of prevalence of chronic pelvic pain: a neglected reproductive health morbidity. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:177.

6. Steege JF, Zolnoun DA. Evaluation and treatment of dyspareunia. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:1124-1136.

7. Williams AA, Williams M. A guide to performing pelvic speculum exams: a patient-centered approach to reducing iatrogenic effects. Teach Learn Med. 2013;25:383-391.

8. Ünlü Z, Yentur A, Çakil N. Pudendal nerve neuropathy: An unknown-rare cause of pelvic pain. Arch Rheumatol. 2016;31:102-103.

9. Dewitte M, Borg C, Lowenstein L. A psychosocial approach to female genital pain. Nat Rev Urol. 2018;15:25-41.

10. Masters WH, Johnson VE. Human Sexual Inadequacy. 1st ed. Little, Brown; 1970.

11. Rathus SA, Nevid JS, Fichner-Rathus L. Human Sexuality in a World of Diversity. 5th ed. Allyn and Bacon; 2002.

12. Bailey BE, Freedenfeld RN, Kiser RS, et al. Lifetime physical and sexual abuse in chronic pain patients: psychosocial correlates and treatment outcomes. Disabil Rehabil. 2003;25:331-342.

13. Yehuda R, Lehrner A, Rosenbaum TY. PTSD and sexual dysfunction in men and women. J Sex Med. 2015;12:1107-1119.

14. Postma R, Bicanic I, van der Vaart H, et al. Pelvic floor muscle problems mediate sexual problems in young adult rape victims. J Sex Med. 2013;10:1978-1987.

15. Binik YM, Bergeron S, Khalifé S. Dyspareunia and vaginismus: so-called sexual pain. In: Leiblum SR, ed. 4th ed. Principles and Practice of Sex Therapy. The Guilford Press; 2007:124-156.

16. Ayling K, Ussher JM. “If sex hurts, am I still a woman?” The subjective experience of vulvodynia in hetero-sexual women. Arch Sex Behav. 2008;37:294-304.

17. Pazmany E, Bergeron S, Van Oudenhove L, et al. Body image and genital self-image in pre-menopausal women with dyspareunia. Arch Sex Behav. 2013;42:999-1010.

18. Maillé DL, Bergeron S, Lambert B. Body image in women with primary and secondary provoked vestibulodynia: a controlled study. J Sex Med. 2015;12:505-515.

19. Ryan L, Hawton K. Female dyspareunia. BMJ. 2004;328:1357.

20. Waldura JF, Arora I, Randall AM, et al. Fifty shades of stigma: exploring the health care experiences of kink-oriented patients. J Sex Med. 2016;13:1918-1929.

21. Hinchliff S, Gott M. Seeking medical help for sexual concerns in mid- and later life: a review of the literature. J Sex Res. 2011;48:106-117.

22. Banaei M, Kariman N, Ozgoli G, et al. Prevalence of postpartum dyspareunia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021;153:14-24.

23. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr Ann. 2002;32:509-515.

24. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092-1097.

25. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. PTSD: National Center for PTSD. Life events checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5). Accessed February 3, 2022. www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/te-measures/life_events_checklist.asp

26. Weathers FW, Litz BT, Keane TM, et al. The PTSD checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). 2013. Accessed February 3, 2022. www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/adult-sr/ptsd-checklist.asp

27. Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, et al. The female sexual function index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26:191-208.

28. Melzack R. The short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire. Pain. 1987;30:191-197.

29. Hassam T, Kelso E, Chowdary P, et al. Sexual assault as a risk factor for gynaecological morbidity: an exploratory systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;255:222-230.

30. Hamlin AA, Sheeder J, Muffly TM. Brief versus thong hygiene in obstetrics and gynecology (B-THONG): a survey study. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2019;45:1190-1196.

31. Foster DC, Kotok MB, Huang LS, et al. Oral desipramine and topical lidocaine for vulvodynia: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:583-593.

32. Pérez-López FR, Bueno-Notivol J, Hernandez AV, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of treatment modalities for vestibulodynia in women. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2019;24:337-346.

33. Cheong YC, Smotra G, Williams AC. Non-surgical interventions for the management of chronic pelvic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(3):CD008797.

34. Goldstein AT, Pukall CF, Brown C, et al. Vulvodynia: assessment and treatment. J Sex Med. 2016;13:572-590.

35. Bergeron S, Binik YM, Khalifé S, et al. A randomized comparison of group cognitive-behavioral therapy, surface electromyographic biofeedback, and vestibulectomy in the treatment of dyspareunia resulting from vulvar vestibulitis. Pain. 2001;91:297-306.

36. Schvartzman R, Schvartzman L, Ferreira CF, et al. Physical therapy intervention for women with dyspareunia: a randomized clinical trial. J Sex Marital Ther. 2019;45:378-394.

37. Morin M, Dumoulin C, Bergeron S, et al. Multimodal physical therapy versus topical lidocaine for provoked vestibulodynia: a multicenter, randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224:189.e1-189.e12.

38. Bergeron S, Khalifé S, Dupuis M-J, et al. A randomized clinical trial comparing group cognitive-behavioral therapy and a topical steroid for women with dyspareunia. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2016;84:259-268.

39. Maseroli E, Scavello I, Rastrelli G, et al. Outcome of medical and psychosexual interventions for vaginismus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sex Med. 2018;15:1752-1764.

40. American Psychological Association. Clinical practice guideline for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults. 2017. Accessed February 3, 2022. www.apa.org/ptsd-guideline/ptsd.pdf

Dyspareunia is persistent or recurrent pain before, during, or after sexual contact and is not limited to cisgender individuals or vaginal intercourse.1-3 With a prevalence as high as 45% in the United States,2-5 it is one of the most common complaints in gynecologic practices.5,6

Causes and contributing factors

There are many possible causes of dyspareunia.2,4,6 While some patients have a single cause, most cases are complex, with multiple overlapping causes and maintaining factors.4,6 Identifying each contributing factor can help you appropriately address all components.

Physical conditions. The range of physical contributors to dyspareunia includes inflammatory processes, structural abnormalities, musculoskeletal dysfunctions, pelvic organ disorders, injuries, iatrogenic effects, infections, allergic reactions, sensitization, hormonal changes, medication effects, adhesions, autoimmune disorders, and other pain syndromes (TABLE 12-4,6-11).

Inadequate arousal. One of the primary causes of pain during vaginal penetration is inadequate arousal and lubrication.1,2,9-11 Arousal is the phase of the sexual response cycle that leads to genital tumescence and prepares the genitals for sexual contact through penile/clitoral erection, vaginal engorgement, and lubrication, which prevents pain and enhances pleasurable sensation.9-11

While some physical conditions can lead to an inability to lubricate, the most common causes of inadequate lubrication are psychosocial-behavioral, wherein patients have the same physical ability to lubricate as patients without genital pain but do not progress through the arousal phase.9-11 Behavioral factors such as inadequate or ineffective foreplay can fail to produce engorgement and lubrication, while psychosocial factors such as low attraction to partner, relationship stressors, anxiety, or low self-esteem can have an inhibitory effect on sexual arousal.1,2,9-11 Psychosocial and behavioral factors may also be maintaining factors or consequences of dyspareunia, and need to be assessed and treated.1,2,9-11

Psychological trauma. Exposure to psychological traumas and the development of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have been linked with the development of pain disorders in general and dyspareunia specifically. Most patients seeking treatment for chronic pain disorders have a history of physical or sexual abuse.12 Changes in physiologic processes (eg, neurochemical, endocrine) that occur with PTSD interfere with the sexual response cycle, and sexual traumas specifically have been linked with pelvic floor dysfunction.13,14 Additionally, when PTSD is caused by a sexual trauma, even consensual sexual encounters can trigger flashbacks, intrusive memories, hyperarousal, and muscle tension that interfere with the sexual response cycle and contribute to genital pain.13

Vaginismus is both a physiologic and psychological contributor to dyspareunia.1,2,4 Patients experiencing pain can develop anxiety about repeated pain and involuntarily contract their pelvic muscles, thereby creating more pain, increasing anxiety, decreasing lubrication, and causing pelvic floor dysfunction.1-4,6 Consequently, all patients with dyspareunia should be assessed and continually monitored for symptoms of vaginismus.

Continue to: Anxiety

Anxiety. As with other pain disorders, anxiety develops around pain triggers.10,15 When expecting sexual activity, patients can experience extreme worry and panic attacks.10,15,16 The distress of sexual encounters can interfere with physiologic arousal and sexual desire, impacting all phases of the sexual response cycle.1,2

Relationship issues. Difficulty engaging in or avoidance of sexual activity can interfere with romantic relationships.2,10,16 Severe pain or vaginismus contractions can prevent penetration, leading to unconsummated marriages and an inability to conceive through intercourse.10 The distress surrounding sexual encounters can precipitate erectile dysfunction in male partners, or partners may continue to demand sexual encounters despite the patient’s pain, further impacting the relationship and heightening sexual distress.10 These stressors have led to relationships ending, patients reluctantly agreeing to nonmonogamy to appease their partners, and patients avoiding relationships altogether.10,16

Devalued self-image. Difficulties with sexuality and relationships impact the self-image of patients with dyspareunia. Diminished self-image may include feeling “inadequate” as a woman and as a sexual partner, or feeling like a “failure.”16 Women with dyspareunia often have more distress related to their body image, physical appearance, and genital self-image than do women without genital pain.17 Feeling resentment toward their body, or feeling “ugly,” embarrassed, shamed, “broken,” and “useless” also contribute to increased depressive symptoms found in patients with dyspareunia.16,18

Making the diagnosis

Most patients do not report symptoms unless directly asked2,7; therefore, it is recommended that all patients be screened as a part of an initial intake and before any genital exam (TABLE 22-4,6,7,9,11,19,20).4,7,21 If this screen is positive, a separate appointment may be needed for a thorough evaluation and before any attempt is made at a genital exam.4,7

Items to include in the clinical interview

Given the range of possible causes of dyspareunia and its contributing factors and symptoms, a thorough clinical interview is essential. Begin with a review of the patient’s complete medical and surgical history to identify possible known contributors to genital pain.4 Pregnancy history is of particular importance as the prevalence of postpartum dyspareunia is 35%, with risk being greater for patients who experienced dyspareunia symptoms before pregnancy.22

Knowing the location and quality of pain is important for differentiating between possible diagnoses, as is specifying dyspareunia as lifelong or acquired, superficial or deep, and primary or secondary.1-4,6 Confirm the specific location(s) of pain—eg, at the introitus, in the vestibule, on the labia, in the perineum, or near the clitoris.2,4,6 A diagram or model may be needed to help patients to localize pain.4

To help narrow the differential, include the following elements in your assessment: pain quality, timing (eg, initial onset, episode onset, episode duration, situational triggers), alleviating factors, symptoms in surrounding structures (eg, bladder, bowel, muscles, bones), sexual history, other areas of sexual functioning, history of psychological trauma, relationship effects, and mental health (TABLE 22-4,6,7,9,11,19,20 and Table 323-28). Screening for a history of sexual trauma is particularly important, as a recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that women with a history of sexual assault had a 42% higher risk of gynecologic problems overall, a 74% higher risk of dyspareunia, and a 71% higher risk of vaginismus than women without a history of sexual assault.29 Using measures such as the Female Sexual Function Index or the McGill Pain Questionnaire can help patients more thoroughly describe their symptoms (TABLE 323-28).3

Continue to: Guidelines for the physical exam

Guidelines for the physical exam

Before the exam, ensure the patient has not used any topical genital treatment in the past 2 weeks that may interfere with sensitivity to the exam.4 To decrease patients’ anxiety about the exam, remind them that they can stop the exam at any time.7 Also consider offering the use of a mirror to better pinpoint the location of pain, and to possibly help the patient learn more about her anatomy.2,7

Begin the exam by palpating surrounding areas that may be involved in pain, including the abdomen and musculoskeletal features.3,6,19 Next visually inspect the external genitalia for lesions, abrasions, discoloration, erythema, or other abnormal findings.2,3,6 Ask the patient for permission before contacting the genitals. Because the labia may be a site of pain, apply gentle pressure in retracting it to fully examine the vestibule.6,7 Contraction of the pelvic floor muscles during approach or initial palpation could signal possible vaginismus.4

After visual inspection of external genitalia, use a cotton swab to map the vulva and vestibule in a clockwise fashion to precisely identify any painful locations.2-4,6 If the patient’s history of pain has been intermittent, it’s possible that the cotton swab will not elicit pain on the day of the initial exam, but it may on other days.4

Begin the internal exam by inserting a single finger into the first inch of the vagina and have the patient squeeze and release to assess tenderness, muscle tightness, and control.2,6 Advance the finger further into the vagina and palpate clockwise, examining the levator muscles, obturator muscles, rectum, urethra, and bladder for abnormal tightness or reproduction of pain.2,4,6 Complete a bimanual exam to evaluate the pelvic organs and adnexa.2,4 If indicated, a more thorough evaluation of pelvic floor musculature can be performed by a physical therapist or gynecologist who specializes in pelvic pain.2-4

If the patient consents to further evaluation, consider using a small speculum, advanced slowly, for further internal examination, noting any lesions, abrasions, discharge, ectropion, or tenderness.2-4,7 A rectal exam may also be needed in cases of deep dyspareunia.6 Initial work-up may include a potassium hydroxide wet prep, sexually transmitted infection testing, and pelvic ultrasound.2,4 In some cases, laparoscopy or biopsy may be needed.2,4

Treatments for common causes

Treatment often begins with education about anatomy, to help patients communicate about symptoms and engage more fully in their care.3 Additional education may be needed on genital functioning and the necessity of adequate stimulation and lubrication prior to penetration.1,2,9-11 A discussion of treatments for the wide range of possible causes of dyspareunia is outside the scope of this article. However, some basic behavioral changes may help patients address some of the more common contributing factors.

For example, if vaginal infection is suspected, advise patients to discontinue the use of harsh soaps, known vaginal irritants (eg, perfumed products, bath additives), and douches.3 Recommend using only preservative- and alcohol-free lubricants for sexual contact, and avoiding lubricants with added functions (eg, warming).3 It’s worth noting that avoidance of tight clothing and thong underwear due to possible risk for infections may not be necessary. A recent study found that women who frequently wore thong underwear (more than half of the time) were no more likely to develop urinary tract infections, yeast vaginitis, or bacterial vaginosis than those who avoid such items.30 However, noncotton underwear fabric, rather than tightness, was associated with yeast vaginitis30; therefore, patients may want to consider using only breathable underwear.3

Continue to: Medication

Medication. Medication may be used to treat the underlying contributing conditions or the symptom of pain directly. Some common options are particularly important for patients whose dyspareunia does not have an identifiable cause. These medications include anti-inflammatory agents, topical anesthetics, tricyclic antidepressants, and hormonal treatments.2-4 Since effectiveness varies based on subtypes of pain, select a medication according to the location, timing, and hypothesized mechanism of pain.3,31,32

Medication for deep pain. A meta-analysis and systematic review found that patients with some types of chronic pelvic pain with pain deep in the vagina or pelvis experienced greater than 50% reduction in pain using medroxyprogesterone acetate compared with placebo.33 Other treatments for deep pain depend on physical exam findings.

Medication for superficial pain. Many remedies have been tried, with at least 26 different treatments for vulvodynia pain alone.16 Only some of these treatments have supporting evidence. For patients with vulvar pain, an intent-to-treat RCT found that patients using a topical steroid experienced a 23% reduction in pain from pre-treatment to 6-month follow-up.32

Surgery is also effective for vulvar pain.34,35 For provoked vestibulodynia (in which pain is localized to the vestibule and triggered by contact with the vulva), or vulvar vestibulitis, RCTs have found that vestibulectomy has stronger effects on pain than other treatments,31,35 with a 53% reduction in pain during intercourse and a 70% reduction in vestibular pain overall.35 However, while vestibulectomy is effective for provoked vestibulodynia, it is not recommended for generalized vulvodynia, in which pain is diffuse across the vulva and occurs without vulvar contact.34

Unsupported treatments. A number of other treatments have not yet been found effective. Although lidocaine for vulvar pain is often used, RCTs have not found any significant reduction in symptoms, and a double-blind RCT found that lidocaine ointment actually performed worse than placebo.31,34 Similarly, oral tricyclics have not been found to decrease vulvar pain more than placebo in double-blind studies.31,34 Furthermore, a meta-analysis of RCTs comparing treatments with placebo for vestibular pain found no significant decrease in dyspareunia for topical conjugated estrogen, topical lidocaine, oral desipramine, oral desipramine with topical lidocaine, laser therapy, or transcranial direct current.32

Tx risks to consider. Risks and benefits of dyspareunia treatment options should be thoroughly weighed and discussed with the patient.2-4 Vestibulectomy, despite reducing pain for many patients, has led to increased pain for 9% of patients who underwent the procedure.35 Topical treatments may lead to allergic reactions, inflammation, and worsening of symptoms,4 and hormonal treatments have been found to increase the risk of weight gain and bloating and are not appropriate for patients trying to conceive.33

Coordinate care with other providers

While medications and surgery can reduce pain, they have not been shown to improve other aspects of sexual functioning such as sexual satisfaction, frequency of sexual intercourse, or overall sense of sexual functioning.35 Additionally, pain reduction does not address muscle tension, anxiety, self-esteem, and relationship problems. As a result, a multidisciplinary approach is generally needed.3,4,32,33

Continue to: Physical therapists

Physical therapists. Pelvic floor physical therapists are often members of the dyspareunia treatment team and can provide a thorough evaluation and treatment of pelvic floor disorders.2-4 An RCT with intent-to-treat analysis found that pain was reduced by 71% following pelvic floor physical therapy.36 Another RCT found that 90% of patients reported a clinically meaningful decrease in pain with pelvic floor physical therapy.37 In addition to addressing pain, pelvic floor physical therapy has also been found to improve sexual functioning, sexual satisfaction, distress, and patient perception of improvement.34,36,37

Behavioral health specialists. Psychotherapists, especially those trained in sex therapy, couples therapy, or cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), are also typically on the treatment team. Multiple RCTs have found evidence of CBT’s effectiveness in the direct treatment of dyspareunia pain. Bergeron et al35 found a 37.5% reduction in vulvar vestibulitis pain intensity during intercourse after patients completed group CBT. Another intent-to-treat RCT found that patients receiving CBT experienced more pain reduction (~ 30%) than patients who were treated with a topical steroid.38

In addition to having a direct impact on pain, CBT has also been found to have a clinically and statistically significant positive impact on other aspects of sexual experience, such as overall sexuality, self-efficacy, overall sexual functioning, frequency of intercourse, and catastrophizing.34,38 A recent meta-analysis of RCTs found that about 80% of vaginismus patients were able to achieve penetrative intercourse after treatment with behavioral sex therapy or CBT.39 This success rate was not exceeded by physical or surgical treatments.39

When PTSD is thought to be a contributing factor, trauma therapy will likely be needed in addition to treatments for dyspareunia. First-line treatments for PTSD include cognitive processing therapy, prolonged exposure, trauma-focused CBT, and cognitive therapy.40

Psychotherapists can also help patients reduce anxiety, reintroduce sexual contact without triggering pain or anxiety, address emotional and self-esteem effects of dyspareunia, address relationship issues, and refocus sexual encounters on pleasure rather than pain avoidance.2-4 Despite patient reports of high treatment satisfaction following therapy,38 many patients may initially lack confidence in psychotherapy as a treatment for pain35 and may need to be educated on its effectiveness and multidimensional benefits.

Gynecologists. Often a gynecologist with specialization in pelvic pain is an essential member of the team for diagnostic clarification, recommendation of treatment options, and performance of more advanced treatments.2,3 If pain has become chronic, the patient may also benefit from a pain management team and support groups.2,3

Follow-up steps

Patients who screen negative for dyspareunia should be re-screened periodically. Continue to assess patients diagnosed with dyspareunia for vaginismus symptoms (if they are not initially present) to ensure that the treatment plan is appropriately adjusted. Once treatment has begun, ask about adverse effects and confidence in the treatment plan to minimize negative impacts on treatment adherence and to anticipate a need for a change in the treatment approach.31,35 In addition to tracking treatment effects on pain, continue to assess for patient-centered outcomes such as emotional functioning, self-esteem, and sexual and relationship satisfaction.34 The Female Sexual Function Index can be a useful tool to track symptoms.27,34

Finally, patients who do not experience sufficient improvement in symptoms and functioning with initial treatment may need continued support and encouragement. Given the broad range of contributing factors and the high number of potential treatments, patients may find hope in learning that multiple other treatment options may be available.

CORRESPONDENCE

Adrienne A. Williams, PhD, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Illinois at Chicago College of Medicine, 1919 W Taylor Street, MC 663, Chicago, IL 60612; awms@uic.edu

Dyspareunia is persistent or recurrent pain before, during, or after sexual contact and is not limited to cisgender individuals or vaginal intercourse.1-3 With a prevalence as high as 45% in the United States,2-5 it is one of the most common complaints in gynecologic practices.5,6

Causes and contributing factors

There are many possible causes of dyspareunia.2,4,6 While some patients have a single cause, most cases are complex, with multiple overlapping causes and maintaining factors.4,6 Identifying each contributing factor can help you appropriately address all components.

Physical conditions. The range of physical contributors to dyspareunia includes inflammatory processes, structural abnormalities, musculoskeletal dysfunctions, pelvic organ disorders, injuries, iatrogenic effects, infections, allergic reactions, sensitization, hormonal changes, medication effects, adhesions, autoimmune disorders, and other pain syndromes (TABLE 12-4,6-11).

Inadequate arousal. One of the primary causes of pain during vaginal penetration is inadequate arousal and lubrication.1,2,9-11 Arousal is the phase of the sexual response cycle that leads to genital tumescence and prepares the genitals for sexual contact through penile/clitoral erection, vaginal engorgement, and lubrication, which prevents pain and enhances pleasurable sensation.9-11

While some physical conditions can lead to an inability to lubricate, the most common causes of inadequate lubrication are psychosocial-behavioral, wherein patients have the same physical ability to lubricate as patients without genital pain but do not progress through the arousal phase.9-11 Behavioral factors such as inadequate or ineffective foreplay can fail to produce engorgement and lubrication, while psychosocial factors such as low attraction to partner, relationship stressors, anxiety, or low self-esteem can have an inhibitory effect on sexual arousal.1,2,9-11 Psychosocial and behavioral factors may also be maintaining factors or consequences of dyspareunia, and need to be assessed and treated.1,2,9-11

Psychological trauma. Exposure to psychological traumas and the development of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have been linked with the development of pain disorders in general and dyspareunia specifically. Most patients seeking treatment for chronic pain disorders have a history of physical or sexual abuse.12 Changes in physiologic processes (eg, neurochemical, endocrine) that occur with PTSD interfere with the sexual response cycle, and sexual traumas specifically have been linked with pelvic floor dysfunction.13,14 Additionally, when PTSD is caused by a sexual trauma, even consensual sexual encounters can trigger flashbacks, intrusive memories, hyperarousal, and muscle tension that interfere with the sexual response cycle and contribute to genital pain.13

Vaginismus is both a physiologic and psychological contributor to dyspareunia.1,2,4 Patients experiencing pain can develop anxiety about repeated pain and involuntarily contract their pelvic muscles, thereby creating more pain, increasing anxiety, decreasing lubrication, and causing pelvic floor dysfunction.1-4,6 Consequently, all patients with dyspareunia should be assessed and continually monitored for symptoms of vaginismus.

Continue to: Anxiety

Anxiety. As with other pain disorders, anxiety develops around pain triggers.10,15 When expecting sexual activity, patients can experience extreme worry and panic attacks.10,15,16 The distress of sexual encounters can interfere with physiologic arousal and sexual desire, impacting all phases of the sexual response cycle.1,2

Relationship issues. Difficulty engaging in or avoidance of sexual activity can interfere with romantic relationships.2,10,16 Severe pain or vaginismus contractions can prevent penetration, leading to unconsummated marriages and an inability to conceive through intercourse.10 The distress surrounding sexual encounters can precipitate erectile dysfunction in male partners, or partners may continue to demand sexual encounters despite the patient’s pain, further impacting the relationship and heightening sexual distress.10 These stressors have led to relationships ending, patients reluctantly agreeing to nonmonogamy to appease their partners, and patients avoiding relationships altogether.10,16

Devalued self-image. Difficulties with sexuality and relationships impact the self-image of patients with dyspareunia. Diminished self-image may include feeling “inadequate” as a woman and as a sexual partner, or feeling like a “failure.”16 Women with dyspareunia often have more distress related to their body image, physical appearance, and genital self-image than do women without genital pain.17 Feeling resentment toward their body, or feeling “ugly,” embarrassed, shamed, “broken,” and “useless” also contribute to increased depressive symptoms found in patients with dyspareunia.16,18

Making the diagnosis

Most patients do not report symptoms unless directly asked2,7; therefore, it is recommended that all patients be screened as a part of an initial intake and before any genital exam (TABLE 22-4,6,7,9,11,19,20).4,7,21 If this screen is positive, a separate appointment may be needed for a thorough evaluation and before any attempt is made at a genital exam.4,7

Items to include in the clinical interview

Given the range of possible causes of dyspareunia and its contributing factors and symptoms, a thorough clinical interview is essential. Begin with a review of the patient’s complete medical and surgical history to identify possible known contributors to genital pain.4 Pregnancy history is of particular importance as the prevalence of postpartum dyspareunia is 35%, with risk being greater for patients who experienced dyspareunia symptoms before pregnancy.22

Knowing the location and quality of pain is important for differentiating between possible diagnoses, as is specifying dyspareunia as lifelong or acquired, superficial or deep, and primary or secondary.1-4,6 Confirm the specific location(s) of pain—eg, at the introitus, in the vestibule, on the labia, in the perineum, or near the clitoris.2,4,6 A diagram or model may be needed to help patients to localize pain.4

To help narrow the differential, include the following elements in your assessment: pain quality, timing (eg, initial onset, episode onset, episode duration, situational triggers), alleviating factors, symptoms in surrounding structures (eg, bladder, bowel, muscles, bones), sexual history, other areas of sexual functioning, history of psychological trauma, relationship effects, and mental health (TABLE 22-4,6,7,9,11,19,20 and Table 323-28). Screening for a history of sexual trauma is particularly important, as a recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that women with a history of sexual assault had a 42% higher risk of gynecologic problems overall, a 74% higher risk of dyspareunia, and a 71% higher risk of vaginismus than women without a history of sexual assault.29 Using measures such as the Female Sexual Function Index or the McGill Pain Questionnaire can help patients more thoroughly describe their symptoms (TABLE 323-28).3

Continue to: Guidelines for the physical exam

Guidelines for the physical exam

Before the exam, ensure the patient has not used any topical genital treatment in the past 2 weeks that may interfere with sensitivity to the exam.4 To decrease patients’ anxiety about the exam, remind them that they can stop the exam at any time.7 Also consider offering the use of a mirror to better pinpoint the location of pain, and to possibly help the patient learn more about her anatomy.2,7

Begin the exam by palpating surrounding areas that may be involved in pain, including the abdomen and musculoskeletal features.3,6,19 Next visually inspect the external genitalia for lesions, abrasions, discoloration, erythema, or other abnormal findings.2,3,6 Ask the patient for permission before contacting the genitals. Because the labia may be a site of pain, apply gentle pressure in retracting it to fully examine the vestibule.6,7 Contraction of the pelvic floor muscles during approach or initial palpation could signal possible vaginismus.4

After visual inspection of external genitalia, use a cotton swab to map the vulva and vestibule in a clockwise fashion to precisely identify any painful locations.2-4,6 If the patient’s history of pain has been intermittent, it’s possible that the cotton swab will not elicit pain on the day of the initial exam, but it may on other days.4

Begin the internal exam by inserting a single finger into the first inch of the vagina and have the patient squeeze and release to assess tenderness, muscle tightness, and control.2,6 Advance the finger further into the vagina and palpate clockwise, examining the levator muscles, obturator muscles, rectum, urethra, and bladder for abnormal tightness or reproduction of pain.2,4,6 Complete a bimanual exam to evaluate the pelvic organs and adnexa.2,4 If indicated, a more thorough evaluation of pelvic floor musculature can be performed by a physical therapist or gynecologist who specializes in pelvic pain.2-4

If the patient consents to further evaluation, consider using a small speculum, advanced slowly, for further internal examination, noting any lesions, abrasions, discharge, ectropion, or tenderness.2-4,7 A rectal exam may also be needed in cases of deep dyspareunia.6 Initial work-up may include a potassium hydroxide wet prep, sexually transmitted infection testing, and pelvic ultrasound.2,4 In some cases, laparoscopy or biopsy may be needed.2,4

Treatments for common causes

Treatment often begins with education about anatomy, to help patients communicate about symptoms and engage more fully in their care.3 Additional education may be needed on genital functioning and the necessity of adequate stimulation and lubrication prior to penetration.1,2,9-11 A discussion of treatments for the wide range of possible causes of dyspareunia is outside the scope of this article. However, some basic behavioral changes may help patients address some of the more common contributing factors.

For example, if vaginal infection is suspected, advise patients to discontinue the use of harsh soaps, known vaginal irritants (eg, perfumed products, bath additives), and douches.3 Recommend using only preservative- and alcohol-free lubricants for sexual contact, and avoiding lubricants with added functions (eg, warming).3 It’s worth noting that avoidance of tight clothing and thong underwear due to possible risk for infections may not be necessary. A recent study found that women who frequently wore thong underwear (more than half of the time) were no more likely to develop urinary tract infections, yeast vaginitis, or bacterial vaginosis than those who avoid such items.30 However, noncotton underwear fabric, rather than tightness, was associated with yeast vaginitis30; therefore, patients may want to consider using only breathable underwear.3

Continue to: Medication

Medication. Medication may be used to treat the underlying contributing conditions or the symptom of pain directly. Some common options are particularly important for patients whose dyspareunia does not have an identifiable cause. These medications include anti-inflammatory agents, topical anesthetics, tricyclic antidepressants, and hormonal treatments.2-4 Since effectiveness varies based on subtypes of pain, select a medication according to the location, timing, and hypothesized mechanism of pain.3,31,32

Medication for deep pain. A meta-analysis and systematic review found that patients with some types of chronic pelvic pain with pain deep in the vagina or pelvis experienced greater than 50% reduction in pain using medroxyprogesterone acetate compared with placebo.33 Other treatments for deep pain depend on physical exam findings.

Medication for superficial pain. Many remedies have been tried, with at least 26 different treatments for vulvodynia pain alone.16 Only some of these treatments have supporting evidence. For patients with vulvar pain, an intent-to-treat RCT found that patients using a topical steroid experienced a 23% reduction in pain from pre-treatment to 6-month follow-up.32

Surgery is also effective for vulvar pain.34,35 For provoked vestibulodynia (in which pain is localized to the vestibule and triggered by contact with the vulva), or vulvar vestibulitis, RCTs have found that vestibulectomy has stronger effects on pain than other treatments,31,35 with a 53% reduction in pain during intercourse and a 70% reduction in vestibular pain overall.35 However, while vestibulectomy is effective for provoked vestibulodynia, it is not recommended for generalized vulvodynia, in which pain is diffuse across the vulva and occurs without vulvar contact.34

Unsupported treatments. A number of other treatments have not yet been found effective. Although lidocaine for vulvar pain is often used, RCTs have not found any significant reduction in symptoms, and a double-blind RCT found that lidocaine ointment actually performed worse than placebo.31,34 Similarly, oral tricyclics have not been found to decrease vulvar pain more than placebo in double-blind studies.31,34 Furthermore, a meta-analysis of RCTs comparing treatments with placebo for vestibular pain found no significant decrease in dyspareunia for topical conjugated estrogen, topical lidocaine, oral desipramine, oral desipramine with topical lidocaine, laser therapy, or transcranial direct current.32

Tx risks to consider. Risks and benefits of dyspareunia treatment options should be thoroughly weighed and discussed with the patient.2-4 Vestibulectomy, despite reducing pain for many patients, has led to increased pain for 9% of patients who underwent the procedure.35 Topical treatments may lead to allergic reactions, inflammation, and worsening of symptoms,4 and hormonal treatments have been found to increase the risk of weight gain and bloating and are not appropriate for patients trying to conceive.33

Coordinate care with other providers

While medications and surgery can reduce pain, they have not been shown to improve other aspects of sexual functioning such as sexual satisfaction, frequency of sexual intercourse, or overall sense of sexual functioning.35 Additionally, pain reduction does not address muscle tension, anxiety, self-esteem, and relationship problems. As a result, a multidisciplinary approach is generally needed.3,4,32,33

Continue to: Physical therapists

Physical therapists. Pelvic floor physical therapists are often members of the dyspareunia treatment team and can provide a thorough evaluation and treatment of pelvic floor disorders.2-4 An RCT with intent-to-treat analysis found that pain was reduced by 71% following pelvic floor physical therapy.36 Another RCT found that 90% of patients reported a clinically meaningful decrease in pain with pelvic floor physical therapy.37 In addition to addressing pain, pelvic floor physical therapy has also been found to improve sexual functioning, sexual satisfaction, distress, and patient perception of improvement.34,36,37

Behavioral health specialists. Psychotherapists, especially those trained in sex therapy, couples therapy, or cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), are also typically on the treatment team. Multiple RCTs have found evidence of CBT’s effectiveness in the direct treatment of dyspareunia pain. Bergeron et al35 found a 37.5% reduction in vulvar vestibulitis pain intensity during intercourse after patients completed group CBT. Another intent-to-treat RCT found that patients receiving CBT experienced more pain reduction (~ 30%) than patients who were treated with a topical steroid.38

In addition to having a direct impact on pain, CBT has also been found to have a clinically and statistically significant positive impact on other aspects of sexual experience, such as overall sexuality, self-efficacy, overall sexual functioning, frequency of intercourse, and catastrophizing.34,38 A recent meta-analysis of RCTs found that about 80% of vaginismus patients were able to achieve penetrative intercourse after treatment with behavioral sex therapy or CBT.39 This success rate was not exceeded by physical or surgical treatments.39

When PTSD is thought to be a contributing factor, trauma therapy will likely be needed in addition to treatments for dyspareunia. First-line treatments for PTSD include cognitive processing therapy, prolonged exposure, trauma-focused CBT, and cognitive therapy.40

Psychotherapists can also help patients reduce anxiety, reintroduce sexual contact without triggering pain or anxiety, address emotional and self-esteem effects of dyspareunia, address relationship issues, and refocus sexual encounters on pleasure rather than pain avoidance.2-4 Despite patient reports of high treatment satisfaction following therapy,38 many patients may initially lack confidence in psychotherapy as a treatment for pain35 and may need to be educated on its effectiveness and multidimensional benefits.

Gynecologists. Often a gynecologist with specialization in pelvic pain is an essential member of the team for diagnostic clarification, recommendation of treatment options, and performance of more advanced treatments.2,3 If pain has become chronic, the patient may also benefit from a pain management team and support groups.2,3

Follow-up steps

Patients who screen negative for dyspareunia should be re-screened periodically. Continue to assess patients diagnosed with dyspareunia for vaginismus symptoms (if they are not initially present) to ensure that the treatment plan is appropriately adjusted. Once treatment has begun, ask about adverse effects and confidence in the treatment plan to minimize negative impacts on treatment adherence and to anticipate a need for a change in the treatment approach.31,35 In addition to tracking treatment effects on pain, continue to assess for patient-centered outcomes such as emotional functioning, self-esteem, and sexual and relationship satisfaction.34 The Female Sexual Function Index can be a useful tool to track symptoms.27,34

Finally, patients who do not experience sufficient improvement in symptoms and functioning with initial treatment may need continued support and encouragement. Given the broad range of contributing factors and the high number of potential treatments, patients may find hope in learning that multiple other treatment options may be available.

CORRESPONDENCE

Adrienne A. Williams, PhD, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Illinois at Chicago College of Medicine, 1919 W Taylor Street, MC 663, Chicago, IL 60612; awms@uic.edu

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th Ed. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

2. Seehusen DA, Baird DC, Bode DV. Dyspareunia in women. Am Fam Phys. 2014;90:465-470.

3. Sorensen J, Bautista KE, Lamvu G, et al. Evaluation and treatment of female sexual pain: a clinical review. Cureus. 2018;10:e2379.

4. MacNeill C. Dyspareunia. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2006;33:565-77.

5. Latthe P, Latthe M, Say L, et al. WHO systematic review of prevalence of chronic pelvic pain: a neglected reproductive health morbidity. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:177.

6. Steege JF, Zolnoun DA. Evaluation and treatment of dyspareunia. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:1124-1136.

7. Williams AA, Williams M. A guide to performing pelvic speculum exams: a patient-centered approach to reducing iatrogenic effects. Teach Learn Med. 2013;25:383-391.

8. Ünlü Z, Yentur A, Çakil N. Pudendal nerve neuropathy: An unknown-rare cause of pelvic pain. Arch Rheumatol. 2016;31:102-103.

9. Dewitte M, Borg C, Lowenstein L. A psychosocial approach to female genital pain. Nat Rev Urol. 2018;15:25-41.

10. Masters WH, Johnson VE. Human Sexual Inadequacy. 1st ed. Little, Brown; 1970.

11. Rathus SA, Nevid JS, Fichner-Rathus L. Human Sexuality in a World of Diversity. 5th ed. Allyn and Bacon; 2002.

12. Bailey BE, Freedenfeld RN, Kiser RS, et al. Lifetime physical and sexual abuse in chronic pain patients: psychosocial correlates and treatment outcomes. Disabil Rehabil. 2003;25:331-342.

13. Yehuda R, Lehrner A, Rosenbaum TY. PTSD and sexual dysfunction in men and women. J Sex Med. 2015;12:1107-1119.

14. Postma R, Bicanic I, van der Vaart H, et al. Pelvic floor muscle problems mediate sexual problems in young adult rape victims. J Sex Med. 2013;10:1978-1987.

15. Binik YM, Bergeron S, Khalifé S. Dyspareunia and vaginismus: so-called sexual pain. In: Leiblum SR, ed. 4th ed. Principles and Practice of Sex Therapy. The Guilford Press; 2007:124-156.

16. Ayling K, Ussher JM. “If sex hurts, am I still a woman?” The subjective experience of vulvodynia in hetero-sexual women. Arch Sex Behav. 2008;37:294-304.

17. Pazmany E, Bergeron S, Van Oudenhove L, et al. Body image and genital self-image in pre-menopausal women with dyspareunia. Arch Sex Behav. 2013;42:999-1010.

18. Maillé DL, Bergeron S, Lambert B. Body image in women with primary and secondary provoked vestibulodynia: a controlled study. J Sex Med. 2015;12:505-515.

19. Ryan L, Hawton K. Female dyspareunia. BMJ. 2004;328:1357.

20. Waldura JF, Arora I, Randall AM, et al. Fifty shades of stigma: exploring the health care experiences of kink-oriented patients. J Sex Med. 2016;13:1918-1929.

21. Hinchliff S, Gott M. Seeking medical help for sexual concerns in mid- and later life: a review of the literature. J Sex Res. 2011;48:106-117.

22. Banaei M, Kariman N, Ozgoli G, et al. Prevalence of postpartum dyspareunia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021;153:14-24.

23. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr Ann. 2002;32:509-515.

24. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092-1097.

25. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. PTSD: National Center for PTSD. Life events checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5). Accessed February 3, 2022. www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/te-measures/life_events_checklist.asp

26. Weathers FW, Litz BT, Keane TM, et al. The PTSD checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). 2013. Accessed February 3, 2022. www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/adult-sr/ptsd-checklist.asp

27. Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, et al. The female sexual function index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26:191-208.

28. Melzack R. The short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire. Pain. 1987;30:191-197.

29. Hassam T, Kelso E, Chowdary P, et al. Sexual assault as a risk factor for gynaecological morbidity: an exploratory systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;255:222-230.

30. Hamlin AA, Sheeder J, Muffly TM. Brief versus thong hygiene in obstetrics and gynecology (B-THONG): a survey study. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2019;45:1190-1196.

31. Foster DC, Kotok MB, Huang LS, et al. Oral desipramine and topical lidocaine for vulvodynia: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:583-593.

32. Pérez-López FR, Bueno-Notivol J, Hernandez AV, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of treatment modalities for vestibulodynia in women. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2019;24:337-346.

33. Cheong YC, Smotra G, Williams AC. Non-surgical interventions for the management of chronic pelvic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(3):CD008797.

34. Goldstein AT, Pukall CF, Brown C, et al. Vulvodynia: assessment and treatment. J Sex Med. 2016;13:572-590.

35. Bergeron S, Binik YM, Khalifé S, et al. A randomized comparison of group cognitive-behavioral therapy, surface electromyographic biofeedback, and vestibulectomy in the treatment of dyspareunia resulting from vulvar vestibulitis. Pain. 2001;91:297-306.

36. Schvartzman R, Schvartzman L, Ferreira CF, et al. Physical therapy intervention for women with dyspareunia: a randomized clinical trial. J Sex Marital Ther. 2019;45:378-394.

37. Morin M, Dumoulin C, Bergeron S, et al. Multimodal physical therapy versus topical lidocaine for provoked vestibulodynia: a multicenter, randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224:189.e1-189.e12.

38. Bergeron S, Khalifé S, Dupuis M-J, et al. A randomized clinical trial comparing group cognitive-behavioral therapy and a topical steroid for women with dyspareunia. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2016;84:259-268.

39. Maseroli E, Scavello I, Rastrelli G, et al. Outcome of medical and psychosexual interventions for vaginismus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sex Med. 2018;15:1752-1764.

40. American Psychological Association. Clinical practice guideline for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults. 2017. Accessed February 3, 2022. www.apa.org/ptsd-guideline/ptsd.pdf

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th Ed. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

2. Seehusen DA, Baird DC, Bode DV. Dyspareunia in women. Am Fam Phys. 2014;90:465-470.

3. Sorensen J, Bautista KE, Lamvu G, et al. Evaluation and treatment of female sexual pain: a clinical review. Cureus. 2018;10:e2379.

4. MacNeill C. Dyspareunia. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2006;33:565-77.

5. Latthe P, Latthe M, Say L, et al. WHO systematic review of prevalence of chronic pelvic pain: a neglected reproductive health morbidity. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:177.

6. Steege JF, Zolnoun DA. Evaluation and treatment of dyspareunia. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:1124-1136.

7. Williams AA, Williams M. A guide to performing pelvic speculum exams: a patient-centered approach to reducing iatrogenic effects. Teach Learn Med. 2013;25:383-391.

8. Ünlü Z, Yentur A, Çakil N. Pudendal nerve neuropathy: An unknown-rare cause of pelvic pain. Arch Rheumatol. 2016;31:102-103.

9. Dewitte M, Borg C, Lowenstein L. A psychosocial approach to female genital pain. Nat Rev Urol. 2018;15:25-41.

10. Masters WH, Johnson VE. Human Sexual Inadequacy. 1st ed. Little, Brown; 1970.

11. Rathus SA, Nevid JS, Fichner-Rathus L. Human Sexuality in a World of Diversity. 5th ed. Allyn and Bacon; 2002.

12. Bailey BE, Freedenfeld RN, Kiser RS, et al. Lifetime physical and sexual abuse in chronic pain patients: psychosocial correlates and treatment outcomes. Disabil Rehabil. 2003;25:331-342.

13. Yehuda R, Lehrner A, Rosenbaum TY. PTSD and sexual dysfunction in men and women. J Sex Med. 2015;12:1107-1119.

14. Postma R, Bicanic I, van der Vaart H, et al. Pelvic floor muscle problems mediate sexual problems in young adult rape victims. J Sex Med. 2013;10:1978-1987.

15. Binik YM, Bergeron S, Khalifé S. Dyspareunia and vaginismus: so-called sexual pain. In: Leiblum SR, ed. 4th ed. Principles and Practice of Sex Therapy. The Guilford Press; 2007:124-156.

16. Ayling K, Ussher JM. “If sex hurts, am I still a woman?” The subjective experience of vulvodynia in hetero-sexual women. Arch Sex Behav. 2008;37:294-304.

17. Pazmany E, Bergeron S, Van Oudenhove L, et al. Body image and genital self-image in pre-menopausal women with dyspareunia. Arch Sex Behav. 2013;42:999-1010.

18. Maillé DL, Bergeron S, Lambert B. Body image in women with primary and secondary provoked vestibulodynia: a controlled study. J Sex Med. 2015;12:505-515.

19. Ryan L, Hawton K. Female dyspareunia. BMJ. 2004;328:1357.

20. Waldura JF, Arora I, Randall AM, et al. Fifty shades of stigma: exploring the health care experiences of kink-oriented patients. J Sex Med. 2016;13:1918-1929.

21. Hinchliff S, Gott M. Seeking medical help for sexual concerns in mid- and later life: a review of the literature. J Sex Res. 2011;48:106-117.

22. Banaei M, Kariman N, Ozgoli G, et al. Prevalence of postpartum dyspareunia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021;153:14-24.

23. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr Ann. 2002;32:509-515.

24. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092-1097.

25. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. PTSD: National Center for PTSD. Life events checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5). Accessed February 3, 2022. www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/te-measures/life_events_checklist.asp

26. Weathers FW, Litz BT, Keane TM, et al. The PTSD checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). 2013. Accessed February 3, 2022. www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/adult-sr/ptsd-checklist.asp

27. Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, et al. The female sexual function index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26:191-208.

28. Melzack R. The short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire. Pain. 1987;30:191-197.

29. Hassam T, Kelso E, Chowdary P, et al. Sexual assault as a risk factor for gynaecological morbidity: an exploratory systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;255:222-230.

30. Hamlin AA, Sheeder J, Muffly TM. Brief versus thong hygiene in obstetrics and gynecology (B-THONG): a survey study. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2019;45:1190-1196.

31. Foster DC, Kotok MB, Huang LS, et al. Oral desipramine and topical lidocaine for vulvodynia: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:583-593.

32. Pérez-López FR, Bueno-Notivol J, Hernandez AV, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of treatment modalities for vestibulodynia in women. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2019;24:337-346.

33. Cheong YC, Smotra G, Williams AC. Non-surgical interventions for the management of chronic pelvic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(3):CD008797.

34. Goldstein AT, Pukall CF, Brown C, et al. Vulvodynia: assessment and treatment. J Sex Med. 2016;13:572-590.

35. Bergeron S, Binik YM, Khalifé S, et al. A randomized comparison of group cognitive-behavioral therapy, surface electromyographic biofeedback, and vestibulectomy in the treatment of dyspareunia resulting from vulvar vestibulitis. Pain. 2001;91:297-306.

36. Schvartzman R, Schvartzman L, Ferreira CF, et al. Physical therapy intervention for women with dyspareunia: a randomized clinical trial. J Sex Marital Ther. 2019;45:378-394.

37. Morin M, Dumoulin C, Bergeron S, et al. Multimodal physical therapy versus topical lidocaine for provoked vestibulodynia: a multicenter, randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224:189.e1-189.e12.

38. Bergeron S, Khalifé S, Dupuis M-J, et al. A randomized clinical trial comparing group cognitive-behavioral therapy and a topical steroid for women with dyspareunia. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2016;84:259-268.

39. Maseroli E, Scavello I, Rastrelli G, et al. Outcome of medical and psychosexual interventions for vaginismus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sex Med. 2018;15:1752-1764.

40. American Psychological Association. Clinical practice guideline for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults. 2017. Accessed February 3, 2022. www.apa.org/ptsd-guideline/ptsd.pdf

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Screen all patients for sexual dysfunctions, as patients often do not report symptoms on their own. B

› Refer patients with dyspareunia for psychotherapy to address both pain and psychosocial causes and sequela of dyspareunia. A

› Refer patients with dyspareunia for pelvic floor physical therapy to address pain and sexual functioning. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series