User login

Looking back after a long and distinguished career, Leon Eisenberg, MD, invoked the term “furor therapeuticus” to describe overzealous treatment by doctors who became frustrated with therapeutic limitations or motivated by professional enthusiasm.1

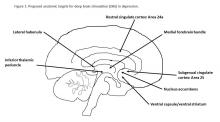

With this in mind, Dr. Eisenberg criticized expansive marketing and prescribing of psychotropic drugs in an editorial published exactly 10 years ago. He might also have questioned the current interest in deep brain stimulation (DBS) as a treatment for depression and a growing list of behavioral disorders. Initial studies of DBS in depression were promising, but recent setbacks have brought research to a scientific and ethical crossroads that compels broader discussion.

Besides uncertainties over the right targets to stimulate, identification of the right candidates for DBS treatment can be difficult. Trials of DBS recruited highly selected depressed subjects with no consensus on symptoms or biomarkers that could be used to predict who might respond. Doctors still rely on clinical symptoms to distinguish patients with melancholic depression, who respond to medications or electroconvulsive therapy and might also respond to DBS, from patients with depressed mood because of psychosocial problems, who respond to psychotherapy or social interventions.

Evidence on the efficacy and safety of DBS in depression is mixed. Initial open trials were promising, with dramatic and sustained recovery in some patients, but they were limited by small numbers of subjects and a lack of randomized controls and standardized methods.4,5

DBS is not without serious side effects, and substantial maintenance costs are not always covered by insurance. So, two recent industry trials were eagerly anticipated but showed no significant differences between active and sham stimulations in depression.6,7 These disappointing results prompted soul-searching among investigators, who presented ingenious ideas for correcting shortcomings that could be tested in future trials but also raised doubts as to the prospects of DBS in depression.4,5

Given that DBS devices already are marketed for neurological disorders, regulation of practice is crucial to prevent off-label misuse in behavioral disorders.8 Federal agencies enforce rules governing DBS devices but rely on investigators and local review boards in research and on voluntary postmarketing reports by individual practitioners to monitor compliance and safety. Unscrupulous commercial interests could expand the market for these devices, as demonstrated by the proliferation of psychotropic drug prescribing decried by Dr. Eisenberg. DBS also must be restricted to specialized teams and medical centers to prevent inappropriate implantation by poorly trained providers.

Because behavioral disorders exact an enormous toll on patients, families, and society, better access to effective care and the search for better treatments must remain public health priorities.

Transformative, breakthrough discoveries in brain research will undoubtedly lead to improvements in treatment, including surgical devices in some cases, but, DBS is at risk of being exaggerated and oversold. Adverse consequences of misuse could provoke a public backlash that would have a chilling effect on vital brain research.

One possible way to prevent this is the risk evaluation and mitigation strategy established by the Food and Drug Administration to manage high-risk pharmaceuticals. The FDA mandates that certain high-risk drugs can be prescribed only if doctors are certified and only if patients are enrolled in a national registry where eligibility, course, and outcome are monitored. A similar mechanism should apply to high-risk surgical devices when used for behavioral disorders.9,10

People with behavioral disorders deserve the right to volunteer for experimental programs that offer hope of recovery for themselves and future generations, but they also deserve to be treated with the utmost scientific rigor and protection that society can provide.

Dr. Caroff is emeritus professor of psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. He has received research grant funding from Sunovion Pharmaceuticals and serves as a consultant to Neurocrine Biosciences and TEVA.

References

1. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(4):552-5

2. Curr Behav Neurosci Rep. 2014;1(2):55-63

3. J Affect Disord. 2014;156:1-7

4. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;739(5):439-40

5. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(4):e9-10

6. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2015;93:366-9

7. Neurotherapeutics. 2014;11(3):475-84

8. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85(9):1003-8

9. Brain Stimul. 2012;5(4):653-5

10. Fed Reg. 1977 May 23;42(99):26318-32

Looking back after a long and distinguished career, Leon Eisenberg, MD, invoked the term “furor therapeuticus” to describe overzealous treatment by doctors who became frustrated with therapeutic limitations or motivated by professional enthusiasm.1

With this in mind, Dr. Eisenberg criticized expansive marketing and prescribing of psychotropic drugs in an editorial published exactly 10 years ago. He might also have questioned the current interest in deep brain stimulation (DBS) as a treatment for depression and a growing list of behavioral disorders. Initial studies of DBS in depression were promising, but recent setbacks have brought research to a scientific and ethical crossroads that compels broader discussion.

Besides uncertainties over the right targets to stimulate, identification of the right candidates for DBS treatment can be difficult. Trials of DBS recruited highly selected depressed subjects with no consensus on symptoms or biomarkers that could be used to predict who might respond. Doctors still rely on clinical symptoms to distinguish patients with melancholic depression, who respond to medications or electroconvulsive therapy and might also respond to DBS, from patients with depressed mood because of psychosocial problems, who respond to psychotherapy or social interventions.

Evidence on the efficacy and safety of DBS in depression is mixed. Initial open trials were promising, with dramatic and sustained recovery in some patients, but they were limited by small numbers of subjects and a lack of randomized controls and standardized methods.4,5

DBS is not without serious side effects, and substantial maintenance costs are not always covered by insurance. So, two recent industry trials were eagerly anticipated but showed no significant differences between active and sham stimulations in depression.6,7 These disappointing results prompted soul-searching among investigators, who presented ingenious ideas for correcting shortcomings that could be tested in future trials but also raised doubts as to the prospects of DBS in depression.4,5

Given that DBS devices already are marketed for neurological disorders, regulation of practice is crucial to prevent off-label misuse in behavioral disorders.8 Federal agencies enforce rules governing DBS devices but rely on investigators and local review boards in research and on voluntary postmarketing reports by individual practitioners to monitor compliance and safety. Unscrupulous commercial interests could expand the market for these devices, as demonstrated by the proliferation of psychotropic drug prescribing decried by Dr. Eisenberg. DBS also must be restricted to specialized teams and medical centers to prevent inappropriate implantation by poorly trained providers.

Because behavioral disorders exact an enormous toll on patients, families, and society, better access to effective care and the search for better treatments must remain public health priorities.

Transformative, breakthrough discoveries in brain research will undoubtedly lead to improvements in treatment, including surgical devices in some cases, but, DBS is at risk of being exaggerated and oversold. Adverse consequences of misuse could provoke a public backlash that would have a chilling effect on vital brain research.

One possible way to prevent this is the risk evaluation and mitigation strategy established by the Food and Drug Administration to manage high-risk pharmaceuticals. The FDA mandates that certain high-risk drugs can be prescribed only if doctors are certified and only if patients are enrolled in a national registry where eligibility, course, and outcome are monitored. A similar mechanism should apply to high-risk surgical devices when used for behavioral disorders.9,10

People with behavioral disorders deserve the right to volunteer for experimental programs that offer hope of recovery for themselves and future generations, but they also deserve to be treated with the utmost scientific rigor and protection that society can provide.

Dr. Caroff is emeritus professor of psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. He has received research grant funding from Sunovion Pharmaceuticals and serves as a consultant to Neurocrine Biosciences and TEVA.

References

1. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(4):552-5

2. Curr Behav Neurosci Rep. 2014;1(2):55-63

3. J Affect Disord. 2014;156:1-7

4. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;739(5):439-40

5. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(4):e9-10

6. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2015;93:366-9

7. Neurotherapeutics. 2014;11(3):475-84

8. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85(9):1003-8

9. Brain Stimul. 2012;5(4):653-5

10. Fed Reg. 1977 May 23;42(99):26318-32

Looking back after a long and distinguished career, Leon Eisenberg, MD, invoked the term “furor therapeuticus” to describe overzealous treatment by doctors who became frustrated with therapeutic limitations or motivated by professional enthusiasm.1

With this in mind, Dr. Eisenberg criticized expansive marketing and prescribing of psychotropic drugs in an editorial published exactly 10 years ago. He might also have questioned the current interest in deep brain stimulation (DBS) as a treatment for depression and a growing list of behavioral disorders. Initial studies of DBS in depression were promising, but recent setbacks have brought research to a scientific and ethical crossroads that compels broader discussion.

Besides uncertainties over the right targets to stimulate, identification of the right candidates for DBS treatment can be difficult. Trials of DBS recruited highly selected depressed subjects with no consensus on symptoms or biomarkers that could be used to predict who might respond. Doctors still rely on clinical symptoms to distinguish patients with melancholic depression, who respond to medications or electroconvulsive therapy and might also respond to DBS, from patients with depressed mood because of psychosocial problems, who respond to psychotherapy or social interventions.

Evidence on the efficacy and safety of DBS in depression is mixed. Initial open trials were promising, with dramatic and sustained recovery in some patients, but they were limited by small numbers of subjects and a lack of randomized controls and standardized methods.4,5

DBS is not without serious side effects, and substantial maintenance costs are not always covered by insurance. So, two recent industry trials were eagerly anticipated but showed no significant differences between active and sham stimulations in depression.6,7 These disappointing results prompted soul-searching among investigators, who presented ingenious ideas for correcting shortcomings that could be tested in future trials but also raised doubts as to the prospects of DBS in depression.4,5

Given that DBS devices already are marketed for neurological disorders, regulation of practice is crucial to prevent off-label misuse in behavioral disorders.8 Federal agencies enforce rules governing DBS devices but rely on investigators and local review boards in research and on voluntary postmarketing reports by individual practitioners to monitor compliance and safety. Unscrupulous commercial interests could expand the market for these devices, as demonstrated by the proliferation of psychotropic drug prescribing decried by Dr. Eisenberg. DBS also must be restricted to specialized teams and medical centers to prevent inappropriate implantation by poorly trained providers.

Because behavioral disorders exact an enormous toll on patients, families, and society, better access to effective care and the search for better treatments must remain public health priorities.

Transformative, breakthrough discoveries in brain research will undoubtedly lead to improvements in treatment, including surgical devices in some cases, but, DBS is at risk of being exaggerated and oversold. Adverse consequences of misuse could provoke a public backlash that would have a chilling effect on vital brain research.

One possible way to prevent this is the risk evaluation and mitigation strategy established by the Food and Drug Administration to manage high-risk pharmaceuticals. The FDA mandates that certain high-risk drugs can be prescribed only if doctors are certified and only if patients are enrolled in a national registry where eligibility, course, and outcome are monitored. A similar mechanism should apply to high-risk surgical devices when used for behavioral disorders.9,10

People with behavioral disorders deserve the right to volunteer for experimental programs that offer hope of recovery for themselves and future generations, but they also deserve to be treated with the utmost scientific rigor and protection that society can provide.

Dr. Caroff is emeritus professor of psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. He has received research grant funding from Sunovion Pharmaceuticals and serves as a consultant to Neurocrine Biosciences and TEVA.

References

1. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(4):552-5

2. Curr Behav Neurosci Rep. 2014;1(2):55-63

3. J Affect Disord. 2014;156:1-7

4. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;739(5):439-40

5. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(4):e9-10

6. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2015;93:366-9

7. Neurotherapeutics. 2014;11(3):475-84

8. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85(9):1003-8

9. Brain Stimul. 2012;5(4):653-5

10. Fed Reg. 1977 May 23;42(99):26318-32