User login

One of the nation’s most preventable diseases is killing newborns in ever-increasing numbers.

Seventy-eight of those babies were stillborn, and 16 died after birth.

In California, cases of congenital syphilis – the term used when a mother passes the infection to her baby during pregnancy – continued a stark 7-year climb, to 332 cases, an 18.1% increase from 2017, according to the federal data. Only Texas, Nevada, Louisiana, and Arizona had congenital syphilis rates higher than California’s. Those five states combined made up nearly two-thirds of total cases, although all but 17 states saw increases in their congenital syphilis rates.

The state-by-state numbers were released as part of a broader report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tracking trends in sexually transmitted diseases. Cases of syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia combined reached an all-time high in 2018. Cases of the most infectious stage of syphilis rose 14% to more than 35,000 cases; gonorrhea increased 5% to more than 580,000 cases; and chlamydia increased 3% to more than 1.7 million cases.

For veteran public health workers, the upward trend in congenital syphilis numbers is particularly disturbing because the condition is so easy to prevent. Blood tests can identify infection in pregnant women. The treatment is relatively simple and effective. When caught during pregnancy, transmission from mother to baby generally can be stopped.

“When we see a case of congenital syphilis, it is a hallmark of a health system and a health care failure,” said Virginia Bowen, PhD, an epidemiologist with the CDC and an author of the report.

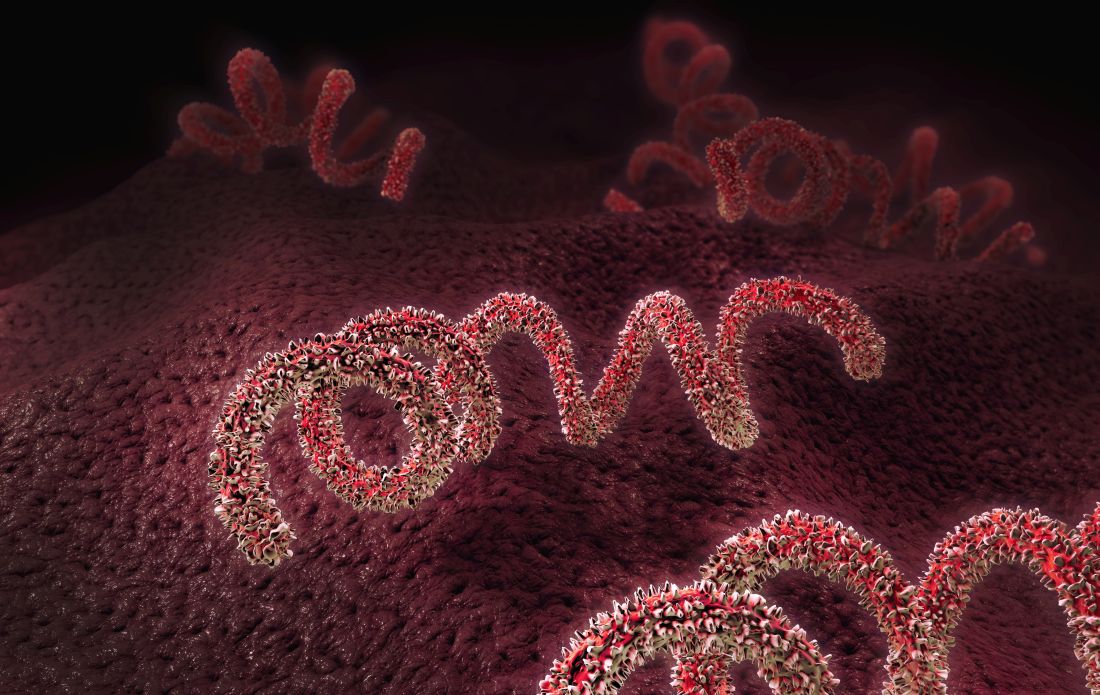

It takes just a few shots of antibiotics to prevent a baby from getting syphilis from its mother. Left untreated, Treponema pallidum, the corkscrew-shaped organism that causes syphilis, can wiggle its way through a mother’s placenta and into a fetus. Once there, it can multiply furiously, invading every part of the body.

The effects on a newborn can be devastating. Philip Cheng, MD, is a neonatologist at St. Joseph’s Medical Center in Stockton, a city in San Joaquin County in California’s Central Valley. Twenty-six babies were infected last year in San Joaquin County, according to state data.

The brain of one of Cheng’s patients didn’t develop properly and the baby died shortly after birth. Other young patients survive but battle blood abnormalities, bone deformities, and organ damage. Congenital syphilis can cause blindness and excruciating pain.

Public health departments across the Central Valley, a largely rural expanse, report similar experiences. Following the release of the CDC report Tuesday, the California Department of Public Health released its county-by-county numbers for 2018. The report showed syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia levels at their highest in 30 years, and attributed 22 stillbirths or neonatal deaths to congenital syphilis.

For the past several years, Fresno County, which had 63 cases of congenital syphilis in 2017, had the highest rate in California. In 2018, Fresno fell to fourth, behind Yuba, Kern, and San Joaquin counties. But the epidemic is far from under control. “I couldn’t even tell you how soon I think we’re going to see a decrease,” said Jena Adams, who oversees HIV and STD programs for Fresno County.

Syphilis was once a prolific and widely feared STD. But by the 1940s, penicillin was found to have a near-perfect cure rate for the disease. By 2000, syphilis rates were so low in the U.S. that the federal government launched a plan to eliminate the disease. Today, that goal is a distant memory.

Health departments once tracked down every person who tested positive for chlamydia, gonorrhea, or syphilis, to make sure they and their partners got treatment. With limited funds and climbing caseloads, many states now devote resources only to tracking syphilis. The caseloads are so high in some California counties that they track only women of childbearing age or just pregnant women.

“A lot of the funding for day-to-day public health work isn’t there,” said Jeffrey Klausner, MD, a professor at the University of California-Los Angeles who ran San Francisco’s STD program for more than a decade.

The bulk of STD prevention funding is appropriated by Congress to the CDC, which passes it on to states. That funding has been largely flat since 2003, according to data from the National Coalition of STD Directors, which represents health departments across the country. Take into account inflation and the growing caseloads, and the money is spread thinner. “It takes money, it takes training, it takes resources,” Dr. Klausner said, “and policymakers have just not prioritized that.”

A report this year by Trust for America’s Health, a public health policy research and advocacy group, estimated that 55,000 jobs were cut from local public health departments from 2008 to 2017. “We have our hands tied as much as [states] do,” said Dr. Bowen of the CDC. “We take what we’re given and try to distribute it as fairly as we can.”

San Joaquin County health officials have reorganized the department and applied for grants to increase the number of investigators available while congenital syphilis has spiked, said Hemal Parikh, county coordinator for STD control. But even with new hires and cutting back to tracking only women of childbearing age with syphilis, an investigator can have anywhere from 20 to 30 open cases at a time. In other counties, the caseload can be double that.

In 2018, Jennifer Wagman, PhD, a UCLA professor who studies infectious diseases and gender inequality, was part of a group that received CDC funding to look into what is causing the spike in congenital syphilis in California’s Central Valley.

Dr. Wagman said that, after years of studying health systems in other countries, she was shocked to see how much basic public health infrastructure has crumbled in California. In many parts of the Central Valley, county walk-in clinics that tested for and treated STDs were shuttered in the wake of the recession. That left few places for drop-in care, and investigators with no place to take someone for immediate treatment. Investigators or their patients must make appointments at one of the few providers who carry the right kind of treatment and hope the patients can keep the appointment when the time comes.

In focus groups, women told Dr. Wagman that working hourly jobs, or dealing with chaotic lives involving homelessness, abusive partners, and drug use, can make it all but impossible to stick to the appointments required at private clinics.

Dr. Wagman found that women in these high-risk groups were seeking care, though sometimes late in their pregnancy. They were just more likely to visit an emergency room, urgent care, or even a methadone clinic – places that take drop-ins but don’t necessarily routinely test for or treat syphilis.

“These people already have a million barriers,” said Jenny Malone, the public health nurse for San Joaquin County. “Now there are more.”

The most challenging cases in California are wrapped up with the state’s growing housing crisis and a methamphetamine epidemic with few treatment options. Women who are homeless often have unreliable contact information and are unlikely to have a primary care doctor. That makes them tough to track down to give a positive diagnosis or to follow up on a treatment plan.

Louisiana had the highest rate of congenital syphilis in the country for several years – until 2018. After a 22% drop in its rate, combined with increases in other states, Louisiana now ranks behind Texas and Nevada. That drop is the direct result of $550 million in temporary supplemental funding that the CDC gave the state to combat the epidemic, said Chaquetta Johnson, DNP, deputy director of operations for the state’s STD/HIV/hepatitis program. The money helped bolster the state’s lagging public health infrastructure. It was used to host two conferences for providers in the hardest-hit areas, hire two case managers and a nurse educator, create a program for in-home treatment, and improve data systems to track cases, among other things.

In California, more than 40% of pregnant women with syphilis passed it on to their baby in 2016, the most recent year for which data is available. Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) made additional funding available this year, but it’s a “drop in the bucket,” said Sergio Morales of Essential Access Health, a nonprofit that focuses on sexual and reproductive health and is working with Kern County on congenital syphilis. “We are seeing the results of years of inaction and a lack of prioritization of STD prevention, and we’re now paying the price.”

This KHN story first published on California Healthline, a service of the California Health Care Foundation. Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

[Update: This story was revised at 6:50 p.m. ET on Oct. 8 to reflect news developments.]

One of the nation’s most preventable diseases is killing newborns in ever-increasing numbers.

Seventy-eight of those babies were stillborn, and 16 died after birth.

In California, cases of congenital syphilis – the term used when a mother passes the infection to her baby during pregnancy – continued a stark 7-year climb, to 332 cases, an 18.1% increase from 2017, according to the federal data. Only Texas, Nevada, Louisiana, and Arizona had congenital syphilis rates higher than California’s. Those five states combined made up nearly two-thirds of total cases, although all but 17 states saw increases in their congenital syphilis rates.

The state-by-state numbers were released as part of a broader report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tracking trends in sexually transmitted diseases. Cases of syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia combined reached an all-time high in 2018. Cases of the most infectious stage of syphilis rose 14% to more than 35,000 cases; gonorrhea increased 5% to more than 580,000 cases; and chlamydia increased 3% to more than 1.7 million cases.

For veteran public health workers, the upward trend in congenital syphilis numbers is particularly disturbing because the condition is so easy to prevent. Blood tests can identify infection in pregnant women. The treatment is relatively simple and effective. When caught during pregnancy, transmission from mother to baby generally can be stopped.

“When we see a case of congenital syphilis, it is a hallmark of a health system and a health care failure,” said Virginia Bowen, PhD, an epidemiologist with the CDC and an author of the report.

It takes just a few shots of antibiotics to prevent a baby from getting syphilis from its mother. Left untreated, Treponema pallidum, the corkscrew-shaped organism that causes syphilis, can wiggle its way through a mother’s placenta and into a fetus. Once there, it can multiply furiously, invading every part of the body.

The effects on a newborn can be devastating. Philip Cheng, MD, is a neonatologist at St. Joseph’s Medical Center in Stockton, a city in San Joaquin County in California’s Central Valley. Twenty-six babies were infected last year in San Joaquin County, according to state data.

The brain of one of Cheng’s patients didn’t develop properly and the baby died shortly after birth. Other young patients survive but battle blood abnormalities, bone deformities, and organ damage. Congenital syphilis can cause blindness and excruciating pain.

Public health departments across the Central Valley, a largely rural expanse, report similar experiences. Following the release of the CDC report Tuesday, the California Department of Public Health released its county-by-county numbers for 2018. The report showed syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia levels at their highest in 30 years, and attributed 22 stillbirths or neonatal deaths to congenital syphilis.

For the past several years, Fresno County, which had 63 cases of congenital syphilis in 2017, had the highest rate in California. In 2018, Fresno fell to fourth, behind Yuba, Kern, and San Joaquin counties. But the epidemic is far from under control. “I couldn’t even tell you how soon I think we’re going to see a decrease,” said Jena Adams, who oversees HIV and STD programs for Fresno County.

Syphilis was once a prolific and widely feared STD. But by the 1940s, penicillin was found to have a near-perfect cure rate for the disease. By 2000, syphilis rates were so low in the U.S. that the federal government launched a plan to eliminate the disease. Today, that goal is a distant memory.

Health departments once tracked down every person who tested positive for chlamydia, gonorrhea, or syphilis, to make sure they and their partners got treatment. With limited funds and climbing caseloads, many states now devote resources only to tracking syphilis. The caseloads are so high in some California counties that they track only women of childbearing age or just pregnant women.

“A lot of the funding for day-to-day public health work isn’t there,” said Jeffrey Klausner, MD, a professor at the University of California-Los Angeles who ran San Francisco’s STD program for more than a decade.

The bulk of STD prevention funding is appropriated by Congress to the CDC, which passes it on to states. That funding has been largely flat since 2003, according to data from the National Coalition of STD Directors, which represents health departments across the country. Take into account inflation and the growing caseloads, and the money is spread thinner. “It takes money, it takes training, it takes resources,” Dr. Klausner said, “and policymakers have just not prioritized that.”

A report this year by Trust for America’s Health, a public health policy research and advocacy group, estimated that 55,000 jobs were cut from local public health departments from 2008 to 2017. “We have our hands tied as much as [states] do,” said Dr. Bowen of the CDC. “We take what we’re given and try to distribute it as fairly as we can.”

San Joaquin County health officials have reorganized the department and applied for grants to increase the number of investigators available while congenital syphilis has spiked, said Hemal Parikh, county coordinator for STD control. But even with new hires and cutting back to tracking only women of childbearing age with syphilis, an investigator can have anywhere from 20 to 30 open cases at a time. In other counties, the caseload can be double that.

In 2018, Jennifer Wagman, PhD, a UCLA professor who studies infectious diseases and gender inequality, was part of a group that received CDC funding to look into what is causing the spike in congenital syphilis in California’s Central Valley.

Dr. Wagman said that, after years of studying health systems in other countries, she was shocked to see how much basic public health infrastructure has crumbled in California. In many parts of the Central Valley, county walk-in clinics that tested for and treated STDs were shuttered in the wake of the recession. That left few places for drop-in care, and investigators with no place to take someone for immediate treatment. Investigators or their patients must make appointments at one of the few providers who carry the right kind of treatment and hope the patients can keep the appointment when the time comes.

In focus groups, women told Dr. Wagman that working hourly jobs, or dealing with chaotic lives involving homelessness, abusive partners, and drug use, can make it all but impossible to stick to the appointments required at private clinics.

Dr. Wagman found that women in these high-risk groups were seeking care, though sometimes late in their pregnancy. They were just more likely to visit an emergency room, urgent care, or even a methadone clinic – places that take drop-ins but don’t necessarily routinely test for or treat syphilis.

“These people already have a million barriers,” said Jenny Malone, the public health nurse for San Joaquin County. “Now there are more.”

The most challenging cases in California are wrapped up with the state’s growing housing crisis and a methamphetamine epidemic with few treatment options. Women who are homeless often have unreliable contact information and are unlikely to have a primary care doctor. That makes them tough to track down to give a positive diagnosis or to follow up on a treatment plan.

Louisiana had the highest rate of congenital syphilis in the country for several years – until 2018. After a 22% drop in its rate, combined with increases in other states, Louisiana now ranks behind Texas and Nevada. That drop is the direct result of $550 million in temporary supplemental funding that the CDC gave the state to combat the epidemic, said Chaquetta Johnson, DNP, deputy director of operations for the state’s STD/HIV/hepatitis program. The money helped bolster the state’s lagging public health infrastructure. It was used to host two conferences for providers in the hardest-hit areas, hire two case managers and a nurse educator, create a program for in-home treatment, and improve data systems to track cases, among other things.

In California, more than 40% of pregnant women with syphilis passed it on to their baby in 2016, the most recent year for which data is available. Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) made additional funding available this year, but it’s a “drop in the bucket,” said Sergio Morales of Essential Access Health, a nonprofit that focuses on sexual and reproductive health and is working with Kern County on congenital syphilis. “We are seeing the results of years of inaction and a lack of prioritization of STD prevention, and we’re now paying the price.”

This KHN story first published on California Healthline, a service of the California Health Care Foundation. Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

[Update: This story was revised at 6:50 p.m. ET on Oct. 8 to reflect news developments.]

One of the nation’s most preventable diseases is killing newborns in ever-increasing numbers.

Seventy-eight of those babies were stillborn, and 16 died after birth.

In California, cases of congenital syphilis – the term used when a mother passes the infection to her baby during pregnancy – continued a stark 7-year climb, to 332 cases, an 18.1% increase from 2017, according to the federal data. Only Texas, Nevada, Louisiana, and Arizona had congenital syphilis rates higher than California’s. Those five states combined made up nearly two-thirds of total cases, although all but 17 states saw increases in their congenital syphilis rates.

The state-by-state numbers were released as part of a broader report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tracking trends in sexually transmitted diseases. Cases of syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia combined reached an all-time high in 2018. Cases of the most infectious stage of syphilis rose 14% to more than 35,000 cases; gonorrhea increased 5% to more than 580,000 cases; and chlamydia increased 3% to more than 1.7 million cases.

For veteran public health workers, the upward trend in congenital syphilis numbers is particularly disturbing because the condition is so easy to prevent. Blood tests can identify infection in pregnant women. The treatment is relatively simple and effective. When caught during pregnancy, transmission from mother to baby generally can be stopped.

“When we see a case of congenital syphilis, it is a hallmark of a health system and a health care failure,” said Virginia Bowen, PhD, an epidemiologist with the CDC and an author of the report.

It takes just a few shots of antibiotics to prevent a baby from getting syphilis from its mother. Left untreated, Treponema pallidum, the corkscrew-shaped organism that causes syphilis, can wiggle its way through a mother’s placenta and into a fetus. Once there, it can multiply furiously, invading every part of the body.

The effects on a newborn can be devastating. Philip Cheng, MD, is a neonatologist at St. Joseph’s Medical Center in Stockton, a city in San Joaquin County in California’s Central Valley. Twenty-six babies were infected last year in San Joaquin County, according to state data.

The brain of one of Cheng’s patients didn’t develop properly and the baby died shortly after birth. Other young patients survive but battle blood abnormalities, bone deformities, and organ damage. Congenital syphilis can cause blindness and excruciating pain.

Public health departments across the Central Valley, a largely rural expanse, report similar experiences. Following the release of the CDC report Tuesday, the California Department of Public Health released its county-by-county numbers for 2018. The report showed syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia levels at their highest in 30 years, and attributed 22 stillbirths or neonatal deaths to congenital syphilis.

For the past several years, Fresno County, which had 63 cases of congenital syphilis in 2017, had the highest rate in California. In 2018, Fresno fell to fourth, behind Yuba, Kern, and San Joaquin counties. But the epidemic is far from under control. “I couldn’t even tell you how soon I think we’re going to see a decrease,” said Jena Adams, who oversees HIV and STD programs for Fresno County.

Syphilis was once a prolific and widely feared STD. But by the 1940s, penicillin was found to have a near-perfect cure rate for the disease. By 2000, syphilis rates were so low in the U.S. that the federal government launched a plan to eliminate the disease. Today, that goal is a distant memory.

Health departments once tracked down every person who tested positive for chlamydia, gonorrhea, or syphilis, to make sure they and their partners got treatment. With limited funds and climbing caseloads, many states now devote resources only to tracking syphilis. The caseloads are so high in some California counties that they track only women of childbearing age or just pregnant women.

“A lot of the funding for day-to-day public health work isn’t there,” said Jeffrey Klausner, MD, a professor at the University of California-Los Angeles who ran San Francisco’s STD program for more than a decade.

The bulk of STD prevention funding is appropriated by Congress to the CDC, which passes it on to states. That funding has been largely flat since 2003, according to data from the National Coalition of STD Directors, which represents health departments across the country. Take into account inflation and the growing caseloads, and the money is spread thinner. “It takes money, it takes training, it takes resources,” Dr. Klausner said, “and policymakers have just not prioritized that.”

A report this year by Trust for America’s Health, a public health policy research and advocacy group, estimated that 55,000 jobs were cut from local public health departments from 2008 to 2017. “We have our hands tied as much as [states] do,” said Dr. Bowen of the CDC. “We take what we’re given and try to distribute it as fairly as we can.”

San Joaquin County health officials have reorganized the department and applied for grants to increase the number of investigators available while congenital syphilis has spiked, said Hemal Parikh, county coordinator for STD control. But even with new hires and cutting back to tracking only women of childbearing age with syphilis, an investigator can have anywhere from 20 to 30 open cases at a time. In other counties, the caseload can be double that.

In 2018, Jennifer Wagman, PhD, a UCLA professor who studies infectious diseases and gender inequality, was part of a group that received CDC funding to look into what is causing the spike in congenital syphilis in California’s Central Valley.

Dr. Wagman said that, after years of studying health systems in other countries, she was shocked to see how much basic public health infrastructure has crumbled in California. In many parts of the Central Valley, county walk-in clinics that tested for and treated STDs were shuttered in the wake of the recession. That left few places for drop-in care, and investigators with no place to take someone for immediate treatment. Investigators or their patients must make appointments at one of the few providers who carry the right kind of treatment and hope the patients can keep the appointment when the time comes.

In focus groups, women told Dr. Wagman that working hourly jobs, or dealing with chaotic lives involving homelessness, abusive partners, and drug use, can make it all but impossible to stick to the appointments required at private clinics.

Dr. Wagman found that women in these high-risk groups were seeking care, though sometimes late in their pregnancy. They were just more likely to visit an emergency room, urgent care, or even a methadone clinic – places that take drop-ins but don’t necessarily routinely test for or treat syphilis.

“These people already have a million barriers,” said Jenny Malone, the public health nurse for San Joaquin County. “Now there are more.”

The most challenging cases in California are wrapped up with the state’s growing housing crisis and a methamphetamine epidemic with few treatment options. Women who are homeless often have unreliable contact information and are unlikely to have a primary care doctor. That makes them tough to track down to give a positive diagnosis or to follow up on a treatment plan.

Louisiana had the highest rate of congenital syphilis in the country for several years – until 2018. After a 22% drop in its rate, combined with increases in other states, Louisiana now ranks behind Texas and Nevada. That drop is the direct result of $550 million in temporary supplemental funding that the CDC gave the state to combat the epidemic, said Chaquetta Johnson, DNP, deputy director of operations for the state’s STD/HIV/hepatitis program. The money helped bolster the state’s lagging public health infrastructure. It was used to host two conferences for providers in the hardest-hit areas, hire two case managers and a nurse educator, create a program for in-home treatment, and improve data systems to track cases, among other things.

In California, more than 40% of pregnant women with syphilis passed it on to their baby in 2016, the most recent year for which data is available. Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) made additional funding available this year, but it’s a “drop in the bucket,” said Sergio Morales of Essential Access Health, a nonprofit that focuses on sexual and reproductive health and is working with Kern County on congenital syphilis. “We are seeing the results of years of inaction and a lack of prioritization of STD prevention, and we’re now paying the price.”

This KHN story first published on California Healthline, a service of the California Health Care Foundation. Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

[Update: This story was revised at 6:50 p.m. ET on Oct. 8 to reflect news developments.]