User login

ORLANDO – Women with breast cancer who look for well-rounded information about treatment on the websites of prominent U.S. cancer centers are likely to come up short, suggests a study presented at a symposium on quality care sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Research has shown that nearly all women with breast cancer search the Internet for information about its treatment, and two-thirds report that what they find has a strong influence on their decision-making process (J Cancer Educ. 2013;28[4]:662-8).

But the analysis of content on the websites of 63 National Cancer Institute–designated comprehensive cancer centers or clinical cancer centers found that, on average, they addressed only 21% of a set of key concepts that women need to understand to make informed decisions about surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, hormone therapy, and breast reconstruction. This contrasted starkly with 85% for the National Cancer Institute’s own website (cancer.gov) and 88% for the Susan G. Komen Foundation’s website (komen.org).

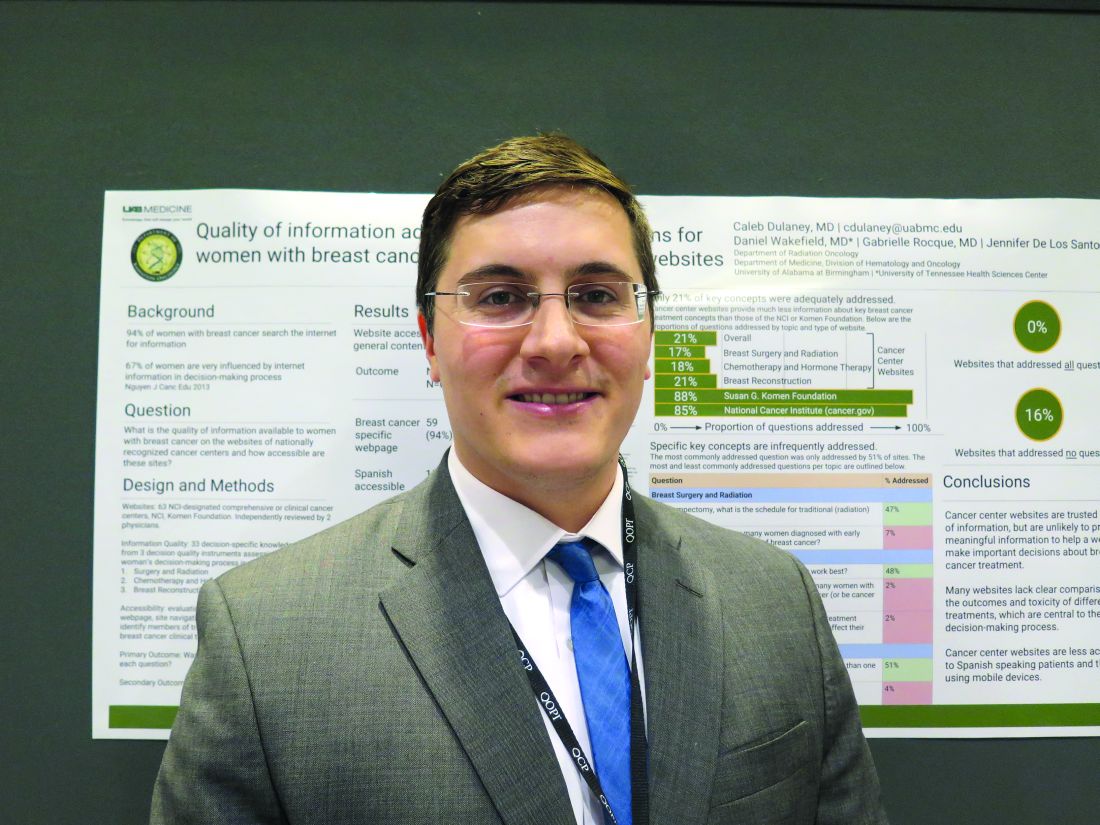

“These are websites that we think are reliable, cancer center websites, and these are the most prominent cancer centers in the country,” first author Caleb Dulaney, MD, a resident in radiation oncology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, said in an interview. “This is where a lot of people receive their care, so they should be very reliable as to the information they provide.

“A lot of websites just had information from the NCI basically integrated into their website or a link to the NCI website,” he acknowledged. “Is it really the goal of the cancer center’s website to provide information? It may not be. But you have to take responsibility for being a trusted source of information. So if you are not going to provide it, you should at least direct people to very accurate, reliable information, and it can also kind of inform what you talk about in clinic.”

All of the investigators evaluating sites in the study were medical professionals, so the team has initiated a new study in which patients will instead perform the evaluations.

“We found that for a few websites, one person found a lot of information and another found no information. So the information may technically be there, but is it transmitted to the patient? Can they find it, and do they understand it?” Dr. Dulaney said. “So it will be interesting when we use patients to evaluate these websites. I’ll be curious to see how many questions they are able to find answers to.”

Study details

For the study, the investigators developed a list of 33 decision-specific knowledge questions about breast cancer treatment by drawing on decision quality instruments that assess how informed a woman’s decision-making process is. The primary outcome was whether the website provided sufficient information to answer each question. The researchers assessed seven measures of accessibility as secondary outcomes.

Results showed that websites contained sufficient content to address only 21% of the decision-specific knowledge questions, Dr. Dulaney reported in a poster session. The value was 17% for questions pertaining to breast surgery and radiation therapy, 18% for those pertaining to chemotherapy and hormone therapy, and 21% for those pertaining to breast reconstruction.

In addition, “a lot of websites put the information in silos,” he noted. “You can read about mastectomy, you can read about lumpectomy, you can read about chemo. But you can’t really get the big picture, which is how do these compare to each other, and which treatment is best for me.”

Even the most commonly addressed single question – what type of reconstruction is most likely to require more than one surgery or procedure – was addressed by only 51% of sites. Proportions were similar for questions pertaining to the type of tumors against which hormone therapy works best (48%) and the schedule for radiation therapy after lumpectomy (47%).

At the other extreme, however, very small proportions of sites addressed questions pertaining to how many women with treated early breast cancer will die from the disease (7%), how many undergoing breast reconstruction will experience complications requiring hospitalization or an unplanned procedure (4%), how skipping chemotherapy and hormone therapy influences risk of death (2%), and whether waiting several weeks to decide about those therapies affects survival (2%). These topics are more negative, Dr. Dulaney observed, “but these are things women need to know.”

None of the websites provided sufficient information to answer all 33 knowledge questions. But perhaps more worrisome, 16% did not provide sufficient information to answer any of them, he said.

When it came to accessibility of information, 94% of sites clearly had a breast cancer–specific page, 87% had information about breast cancer–specific trials, and 86% showed members of the center’s breast cancer team. But only 59% were mobile device friendly as assessed with a Google tool, and merely 24% had obvious links to view information in Spanish.

“A lot of minorities and people of lower socioeconomic status exclusively access the Internet via mobile devices, so they may not have a computer or [other] access to the Internet. But they have a cell phone that is probably a smartphone, and they can get online and search for information that way,” Dr. Dulaney said.

Many oncologists may not have had any say regarding the content and accessibility features of their institution’s website, he acknowledged.

“So we should maybe, number one, try to have more involvement in what information goes on to the website, and two, take a look at our own websites to see what’s on there, because patients are going to look for you, and they are going to associate this information with you,” he said. “If you are at a big institution and you really can’t make a change on your website, you can use alternatives such as social media platforms, things like that, to try and get information out to people.”

From a larger perspective, oncologists have often simply counseled patients that they can’t rely on information they have found online, according to Dr. Dulaney.

“But in this day and age, that can’t really be an answer,” he concluded. “Information on the web is ubiquitous, and there is good information out there. We need to do a better job of speaking up in the conversation. We have the answers to a lot of these questions, we just need to make our voices heard and also direct patients to reliable sources of information.”

ORLANDO – Women with breast cancer who look for well-rounded information about treatment on the websites of prominent U.S. cancer centers are likely to come up short, suggests a study presented at a symposium on quality care sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Research has shown that nearly all women with breast cancer search the Internet for information about its treatment, and two-thirds report that what they find has a strong influence on their decision-making process (J Cancer Educ. 2013;28[4]:662-8).

But the analysis of content on the websites of 63 National Cancer Institute–designated comprehensive cancer centers or clinical cancer centers found that, on average, they addressed only 21% of a set of key concepts that women need to understand to make informed decisions about surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, hormone therapy, and breast reconstruction. This contrasted starkly with 85% for the National Cancer Institute’s own website (cancer.gov) and 88% for the Susan G. Komen Foundation’s website (komen.org).

“These are websites that we think are reliable, cancer center websites, and these are the most prominent cancer centers in the country,” first author Caleb Dulaney, MD, a resident in radiation oncology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, said in an interview. “This is where a lot of people receive their care, so they should be very reliable as to the information they provide.

“A lot of websites just had information from the NCI basically integrated into their website or a link to the NCI website,” he acknowledged. “Is it really the goal of the cancer center’s website to provide information? It may not be. But you have to take responsibility for being a trusted source of information. So if you are not going to provide it, you should at least direct people to very accurate, reliable information, and it can also kind of inform what you talk about in clinic.”

All of the investigators evaluating sites in the study were medical professionals, so the team has initiated a new study in which patients will instead perform the evaluations.

“We found that for a few websites, one person found a lot of information and another found no information. So the information may technically be there, but is it transmitted to the patient? Can they find it, and do they understand it?” Dr. Dulaney said. “So it will be interesting when we use patients to evaluate these websites. I’ll be curious to see how many questions they are able to find answers to.”

Study details

For the study, the investigators developed a list of 33 decision-specific knowledge questions about breast cancer treatment by drawing on decision quality instruments that assess how informed a woman’s decision-making process is. The primary outcome was whether the website provided sufficient information to answer each question. The researchers assessed seven measures of accessibility as secondary outcomes.

Results showed that websites contained sufficient content to address only 21% of the decision-specific knowledge questions, Dr. Dulaney reported in a poster session. The value was 17% for questions pertaining to breast surgery and radiation therapy, 18% for those pertaining to chemotherapy and hormone therapy, and 21% for those pertaining to breast reconstruction.

In addition, “a lot of websites put the information in silos,” he noted. “You can read about mastectomy, you can read about lumpectomy, you can read about chemo. But you can’t really get the big picture, which is how do these compare to each other, and which treatment is best for me.”

Even the most commonly addressed single question – what type of reconstruction is most likely to require more than one surgery or procedure – was addressed by only 51% of sites. Proportions were similar for questions pertaining to the type of tumors against which hormone therapy works best (48%) and the schedule for radiation therapy after lumpectomy (47%).

At the other extreme, however, very small proportions of sites addressed questions pertaining to how many women with treated early breast cancer will die from the disease (7%), how many undergoing breast reconstruction will experience complications requiring hospitalization or an unplanned procedure (4%), how skipping chemotherapy and hormone therapy influences risk of death (2%), and whether waiting several weeks to decide about those therapies affects survival (2%). These topics are more negative, Dr. Dulaney observed, “but these are things women need to know.”

None of the websites provided sufficient information to answer all 33 knowledge questions. But perhaps more worrisome, 16% did not provide sufficient information to answer any of them, he said.

When it came to accessibility of information, 94% of sites clearly had a breast cancer–specific page, 87% had information about breast cancer–specific trials, and 86% showed members of the center’s breast cancer team. But only 59% were mobile device friendly as assessed with a Google tool, and merely 24% had obvious links to view information in Spanish.

“A lot of minorities and people of lower socioeconomic status exclusively access the Internet via mobile devices, so they may not have a computer or [other] access to the Internet. But they have a cell phone that is probably a smartphone, and they can get online and search for information that way,” Dr. Dulaney said.

Many oncologists may not have had any say regarding the content and accessibility features of their institution’s website, he acknowledged.

“So we should maybe, number one, try to have more involvement in what information goes on to the website, and two, take a look at our own websites to see what’s on there, because patients are going to look for you, and they are going to associate this information with you,” he said. “If you are at a big institution and you really can’t make a change on your website, you can use alternatives such as social media platforms, things like that, to try and get information out to people.”

From a larger perspective, oncologists have often simply counseled patients that they can’t rely on information they have found online, according to Dr. Dulaney.

“But in this day and age, that can’t really be an answer,” he concluded. “Information on the web is ubiquitous, and there is good information out there. We need to do a better job of speaking up in the conversation. We have the answers to a lot of these questions, we just need to make our voices heard and also direct patients to reliable sources of information.”

ORLANDO – Women with breast cancer who look for well-rounded information about treatment on the websites of prominent U.S. cancer centers are likely to come up short, suggests a study presented at a symposium on quality care sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Research has shown that nearly all women with breast cancer search the Internet for information about its treatment, and two-thirds report that what they find has a strong influence on their decision-making process (J Cancer Educ. 2013;28[4]:662-8).

But the analysis of content on the websites of 63 National Cancer Institute–designated comprehensive cancer centers or clinical cancer centers found that, on average, they addressed only 21% of a set of key concepts that women need to understand to make informed decisions about surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, hormone therapy, and breast reconstruction. This contrasted starkly with 85% for the National Cancer Institute’s own website (cancer.gov) and 88% for the Susan G. Komen Foundation’s website (komen.org).

“These are websites that we think are reliable, cancer center websites, and these are the most prominent cancer centers in the country,” first author Caleb Dulaney, MD, a resident in radiation oncology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, said in an interview. “This is where a lot of people receive their care, so they should be very reliable as to the information they provide.

“A lot of websites just had information from the NCI basically integrated into their website or a link to the NCI website,” he acknowledged. “Is it really the goal of the cancer center’s website to provide information? It may not be. But you have to take responsibility for being a trusted source of information. So if you are not going to provide it, you should at least direct people to very accurate, reliable information, and it can also kind of inform what you talk about in clinic.”

All of the investigators evaluating sites in the study were medical professionals, so the team has initiated a new study in which patients will instead perform the evaluations.

“We found that for a few websites, one person found a lot of information and another found no information. So the information may technically be there, but is it transmitted to the patient? Can they find it, and do they understand it?” Dr. Dulaney said. “So it will be interesting when we use patients to evaluate these websites. I’ll be curious to see how many questions they are able to find answers to.”

Study details

For the study, the investigators developed a list of 33 decision-specific knowledge questions about breast cancer treatment by drawing on decision quality instruments that assess how informed a woman’s decision-making process is. The primary outcome was whether the website provided sufficient information to answer each question. The researchers assessed seven measures of accessibility as secondary outcomes.

Results showed that websites contained sufficient content to address only 21% of the decision-specific knowledge questions, Dr. Dulaney reported in a poster session. The value was 17% for questions pertaining to breast surgery and radiation therapy, 18% for those pertaining to chemotherapy and hormone therapy, and 21% for those pertaining to breast reconstruction.

In addition, “a lot of websites put the information in silos,” he noted. “You can read about mastectomy, you can read about lumpectomy, you can read about chemo. But you can’t really get the big picture, which is how do these compare to each other, and which treatment is best for me.”

Even the most commonly addressed single question – what type of reconstruction is most likely to require more than one surgery or procedure – was addressed by only 51% of sites. Proportions were similar for questions pertaining to the type of tumors against which hormone therapy works best (48%) and the schedule for radiation therapy after lumpectomy (47%).

At the other extreme, however, very small proportions of sites addressed questions pertaining to how many women with treated early breast cancer will die from the disease (7%), how many undergoing breast reconstruction will experience complications requiring hospitalization or an unplanned procedure (4%), how skipping chemotherapy and hormone therapy influences risk of death (2%), and whether waiting several weeks to decide about those therapies affects survival (2%). These topics are more negative, Dr. Dulaney observed, “but these are things women need to know.”

None of the websites provided sufficient information to answer all 33 knowledge questions. But perhaps more worrisome, 16% did not provide sufficient information to answer any of them, he said.

When it came to accessibility of information, 94% of sites clearly had a breast cancer–specific page, 87% had information about breast cancer–specific trials, and 86% showed members of the center’s breast cancer team. But only 59% were mobile device friendly as assessed with a Google tool, and merely 24% had obvious links to view information in Spanish.

“A lot of minorities and people of lower socioeconomic status exclusively access the Internet via mobile devices, so they may not have a computer or [other] access to the Internet. But they have a cell phone that is probably a smartphone, and they can get online and search for information that way,” Dr. Dulaney said.

Many oncologists may not have had any say regarding the content and accessibility features of their institution’s website, he acknowledged.

“So we should maybe, number one, try to have more involvement in what information goes on to the website, and two, take a look at our own websites to see what’s on there, because patients are going to look for you, and they are going to associate this information with you,” he said. “If you are at a big institution and you really can’t make a change on your website, you can use alternatives such as social media platforms, things like that, to try and get information out to people.”

From a larger perspective, oncologists have often simply counseled patients that they can’t rely on information they have found online, according to Dr. Dulaney.

“But in this day and age, that can’t really be an answer,” he concluded. “Information on the web is ubiquitous, and there is good information out there. We need to do a better job of speaking up in the conversation. We have the answers to a lot of these questions, we just need to make our voices heard and also direct patients to reliable sources of information.”

AT THE QUALITY CARE SYMPOSIUM

Key clinical point:

Major finding: On average, the sites addressed 21% of 33 key concepts needed to make informed decisions about treatment.

Data source: An analysis of breast cancer information on the websites of 63 NCI-designated comprehensive cancer centers or clinical cancer centers.

Disclosures: Dr. Dulaney disclosed that he had no relevant conflicts of interest.