User login

To view three clips of surgical pearls for laparoscopy, visit the Video Library.

<huc>Q.</huc>What is the only surgical procedure that is completely safe?

<huc>A.</huc>The surgical procedure that is not performed.

The unfortunate truth is that complications can occur during any operative procedure, despite our best efforts—and laparoscopy is no exception. Being vigilant for iatrogenic injuries, both during and after surgery, and ensuring that repairs are both thorough and timely, are two of our best weapons against major complications, along with meticulous technique and adequate experience.

This article features five cases that illustrate some of the most serious complications of laparoscopy—and how to prevent and manage them.

CASE 1: Surgical patient returns with signs of ureteral injury

A 42-year-old woman with a history of endometriosis undergoes laparoscopic hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. She is discharged 2 days later. Two days after that, she returns to the hospital complaining of fluid leaking from the vagina. She has no fever or any other significant complaint or physical findings other than abdominal tenderness, which is to be expected after surgery. A computed tomography (CT) scan with intravenous (IV) contrast reveals left ureteral obstruction near the bladder, with extravasation of contrast media into the abdominal cavity. Further investigation reveals a left ureteral transection.

Could this injury have been avoided? How should it be managed?

Postoperative diagnosis of ureteral injury can be challenging, in part because up to 50% of unilateral cases are asymptomatic. Be on the lookout for this complication in women who have undergone pelvic sidewall dissection or laparoscopic hysterectomy, such as the patient in the case just described. As the number of laparoscopic hysterectomies and retroperitoneal procedures has risen in recent years, so has the rate of ureteral injury, with an incidence of 0.3% to 2%.1,2

Ureteral injury can be caused by ligation, ischemia, resection, transection, crushing, or angulation. Three sites are particularly troublesome: the infundibulopelvic ligament, ovarian fossa, and ureteral tunnel.3,4 In Case 1, injury to the ureter was proximal to the bladder and probably occurred during transection of the uterosacral cardinal ligament complex.

What’s the best preventive strategy?

Meticulous technique is imperative to protect the ureters. This includes adequate visualization, intraperitoneal or retroperitoneal dissection, and early identification of the ureter. In a high-risk patient likely to have distorted anatomy due to severe endometriosis and fibrosis, retroperitoneal dissection of any adhesions or tumor and identification of the ureter are the best ways to avoid injury.

Intraperitoneal identification and dissection of the ureters can be enhanced by hydrodissection and resection of the affected peritoneum.3,4 To create a safe operating plane, make a small opening in the peritoneum below the ureter and inject 50 to 100 mL of lactated Ringer’s solution along the course of the ureter, which will displace it laterally.5

Although neither IV indigo carmine nor ureteral catheterization has been shown to reduce the risk of ureteral injury or identify ligation or thermal injury,3,6 both can help the surgeon identify intraoperative perforation of the ureter. Liberal use of cystoscopy with indigo carmine administration for identification of ureteral flow and ureteral catheterization can be used in potentially high-risk patients. If there is suspicion for devascularization or thermal injury, use prophylactic ureteral stents postoperatively for 2 to 4 weeks.

Don’t hesitate to consult a urologist

In Case 1, the surgeon sought immediate urologic consultation and the patient underwent laparotomy with ureteroneocystotomy without sequelae.

In general, management of ureteral injury depends on its severity and location, as well as the comfort level of the surgeon. Minor injuries are sometimes managed with cystoscopic stent placement, but more severe cases may require operative ureteral repair.

In cases like this one, where ureteral injury occurred in close proximity to the bladder, a ureteroneocystotomy is possible. However, in more cephalad injuries, there may be insufficient residual ureter to allow such a repair. In these cases, a Boari flap may be attempted to use bladder tissue to bridge the gap to the ureteral edge. Rarely, in high ureteral injuries, trans-ureteroureterostomy may be appropriate. This procedure carries the greatest risk, given that both kidneys are reliant on one ureter.

Is laparoscopic repair reasonable?

When surgical intervention is necessary, the choice between laparoscopy and laparotomy depends on the skill and comfort level of the surgeon and the availability of instruments and support team.6,7 That said, ureteral injury is usually treated via laparotomy.1 As operative laparoscopy becomes even more commonplace, reconstruction of the urinary system will increasingly be managed laparoscopically.

Depending on the size and location of the injury, reconstruction may involve ureteral reimplantation with or without a psoas hitch, Boari flap, or primary endtoend anastomosis.8-10

CASE 2: Postoperative symptoms lead to rehospitalization

A 35-year-old patient undergoes laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy and returns home the same day. She is readmitted 72 hours later because of lower abdominal tenderness, worsening nausea and vomiting, and urine-like drainage from her midline suprapubic trocar site. Analysis of the leaking fluid shows high creatinine levels consistent with urine. The patient has no fever and is hemodynamically stable. Examination reveals a moderately distended abdomen with decreased bowel sounds. Hematuria is evident on urine analysis.

Urologic consultation is obtained, and the patient undergoes simultaneous laparoscopy and cystoscopy, during which perforation of the bladder dome is discovered, apparently caused by the mid suprapubic trocar. The bladder is mobilized anteriorly, and both anterior and posterior aspects of the perforation are repaired in one layer laparoscopically.

After continuous drainage with a transurethral Foley catheter for 7 days, cystography shows complete healing of the bladder, and the Foley catheter is removed. The patient recovers completely.

Vesical injury sometimes occurs in patients who have a history of laparotomy, a full bladder at the time of surgery, or displaced anatomy due to pelvic adhesions.11 Although bladder injury is rare, laparoscopy increases the risk. Trocars, uterine manipulators, and blunt instruments can perforate or lacerate the bladder, and energy devices can cause thermal injury. The risk of bladder injury increases during laparoscopic hysterectomy.

Be vigilant about trocar placement and dissection techniques

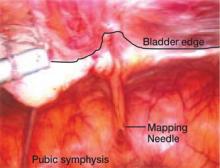

Accessory trocars can injure a full bladder. Injury can also occur when distorted anatomy from a previous pelvic operation obscures bladder boundaries, making insertion of the midline trocar potentially perilous (FIGURE 1). The Veress needle and Rubin’s cannula can perforate the bladder.11-13 And in the anterior cul-de-sac, adhesiolysis, deep coagulation, laser ablation, or sharp excision of endometriosis implants can predispose a patient to bladder injury.

In women with severe endometriosis, lower-segment myoma, or a history of cesarean section, the bladder is vulnerable to laceration when blunt dissection is used during laparoscopic hysterectomy or laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy (LAVH). A vesical injury also can occur at the time of laparoscopic bladder-neck suspension upon entry into, and dissection of, the space of Retzius.

FIGURE 1 A bladder at risk

In this patient with a previous cesarean section, the bladder is adherent to the anterior abdominal wall. Needle mapping in the conventional midline trocar position indicates that the trocar must be relocated to avoid bladder injury.

Intraoperative findings that suggest bladder injury include air in the urinary catheter, hematuria, trocar site drainage of urine, or indigo carmine leakage. Postoperative signs and symptoms include leaking from incisional sites, a mass in the abdominal wall, and abdominal swelling.

Liberal use of cystoscopy or distension of the bladder with 300 to 500 mL of normal saline is recommended whenever there is a suspicion of bladder injury, especially during laparoscopic hysterectomy or LAVH. When a trocar causes the injury, look for both entry and exit punctures, both of which should be treated.

No matter how much care is taken, some bladder injuries, such as vesicovaginal fistulae, become apparent only postoperatively. More rarely, peritonitis or pseudoascites herald the injury. Retrograde cystography may aid identification.

Treatment of bladder injuries

Small perforations recognized intraoperatively may be conservatively managed by postoperative bladder drainage for 5 to 7 days. Most other bladder injuries require prompt intervention. For example, trocar injury to the bladder dome requires one- or two-layer closure followed by 5 to 7 days of urinary drainage. (Both closing and healing are promoted by drainage.)

Laparoscopy or laparotomy? Laparoscopic repair has become increasingly common, and bladder injury is a common complication of LAVH.13,14

CASE 3: Postop pain, tachycardia

A 41-year-old obese woman undergoes laparoscopic cystectomy for an 8-cm left ovarian mass. The abdomen is entered on the second attempt with a long Veress needle. The umbilical trocar is reinserted “several” times because of difficulty opening the peritoneum with the tip of the trocar sheath. The surgical procedure is completed within 2 hours, and the patient is discharged 23 hours later.

The next day, she experiences increasing abdominal pain and presents to the emergency room. Upon admission she reports intermittent chills, but denies nausea and vomiting. She is in mild distress, pale and tachycardic, with a temperature of 96.4°, pulse of 117, respiration rate of 20, blood pressure of 106/64 mm Hg, and oxygen saturation of 92%. She also has a diffusely tender abdomen but normal blood work. Abdominal and chest x-rays show a large right subphrenic air-fluid level that is consistent with free intraperitoneal air, unsurprising given her recent surgery. Bibasilar atelectasis and consolidation are noted on the initial chest x-ray.

During observation over the next 2 days, she remains afebrile and tachycardic, but her shortness of breath becomes progressively worse. Neither spiral CT nor lower-extremity Doppler suggests pulmonary embolism or deep venous thrombosis. Supplemental oxygen, aggressive pain management, albuterol, ipratropium, and acetylcysteine are initiated after pulmonary consultation.

The patient tolerates a regular diet on postoperative day 3 and has a bowel movement on day 5. However, the same day she begins vomiting and reports worsening abdominal pain. CT imaging of the abdomen and pelvis reveals free air in the abdomen and loculated fluid with air bubbles suspicious for intra-abdominal infection and perforated bowel.

Exploratory laparotomy reveals diffuse feculent peritonitis, as well as food particles and contrast media. There is a perforation in the antimesenteric side of the ileum approximately 1.5 feet proximal to the ileocecal valve. This perforation measures approximately 1 cm in diameter and is freely spilling intestinal contents. Small bowel resection is performed to treat the perforation.

Following the surgery, the patient recovers slowly.

Could the bowel perforation have been detected sooner?

Intestinal tract injury is a serious complication, particularly with postoperative diagnosis.15 Damage can occur during insertion of the Veress needle or trocar when the bowel is immobilized by adhesions, or during enterolysis.16 Unrecognized thermal injury can cause delayed bowel injury.

Small-bowel damage often occurs during uncontrolled insertion of the Veress needle or primary umbilical trocar. It also may result from sharp dissection or thermal injury.17,18 Abrasions and lacerations can occur if traction is exerted on the bowel using serrated graspers. When adhesions are dense and tissue planes poorly defined, the risk of laceration due to energy sources or sharp dissection increases.

Be cautious during bowel manipulation. Avoid blunt dissection. Be especially careful when the small bowel is adherent to the anterior abdominal wall (FIGURE 2A), particularly during evaluation of patients with a history of bowel resection, exploratory laparotomy for trauma-related peritonitis, or tumor debulking.

Remove the primary and ancillary cannulas under direct visualization with the laparoscope to prevent formation of a vacuum that can draw bowel into the incision and cause herniation.19

FIGURE 2 Adherent bowel, minor bleeding

A: Veress needle pressure measurements are persistently elevated before primary trocar insertion in this patient, raising the suspicion of adhesive disease from earlier surgery. As a result, the primary trocar is relocated to the left upper quadrant. Inspection confirms that small bowel is adherent to the anterior abdominal wall.

FIGURE 2 Adherent bowel, minor bleeding

B: After the small-bowel adhesions are dissected off the anterior abdominal wall via laparoscopy, a small hematoma is discovered, likely caused by the Veress needle. The patient is managed conservatively and recovers.

The value of open laparoscopy

In open laparoscopy, an abdominal incision is made into the peritoneal cavity so that the trocar can be placed under direct vision, after which the abdomen is insufflated. This approach can prevent bowel injury only when the adhesions and attachments are to the anterior abdominal wall and away from the entry site. When the attachment lies directly beneath the umbilicus, however, open laparoscopy is no guarantee against injury.

When bowel adhesions are severe, use alternative trocar sites such as the left upper quadrant (Palmer’s point) for the Veress needle and primary trocars.5,20,21

The likelihood of perforation can be reduced with preoperative bowel prep when there is a risk of bowel adhesions.

Identifying bowel injury

We recommend routine inspection of the structures beneath the primary trocar upon insertion of the laparoscope to look for injury to the bowel, mesentery, or vascular structures. If adhesions are found, evaluate the area carefully to rule out injury to the bowel or omentum. It may be necessary to change the position of the laparoscope to assess the patient.

Trauma to the intestinal tract can be mechanical or electrical in nature, and each type of trauma creates a distinctive, characteristic pattern. Thermal injury can be subtle and present as simple blanching or a distinct burn and charring. A small hole or obvious tear in the bowel wall can be the result of mechanical injury.22

Benign-appearing, superficial thermal bowel injuries may be managed conservatively.22 Minimal serosal burns (smaller than 5 mm in diameter) can be managed expectantly. Immediate surgical intervention is needed if the area of blanching on the intestinal serosa exceeds 5 mm in diameter or if the burn appears to involve more than the serosa.23

Small-bowel injuries that escape notice intraoperatively generally become apparent 2 to 4 days later, when the patient develops fever, nausea, lower abdominal pain, and anorexia. On postoperative day 5 or 6, the white blood cell (WBC) count rises and earlier symptoms may become worse. Radiography may reveal multiple air and fluid levels—another sign of bowel injury. Be aware that if the patient has clinical symptoms of gastrointestinal injury, even if the WBC count is normal, exploratory laparoscopy or laparotomy is necessary for accurate diagnosis.

Intraoperatively discovered injury

Careful inspection may reveal no leakage or bleeding in the affected area. Small punctures or superficial lacerations seal readily and may not require further treatment (FIGURE 2B), but larger perforations require repair. Straightforward repair is not always possible when the injury is extensive and considerable time has elapsed before it is discovered.

Inspect the intestine thoroughly at the conclusion of a procedure; obvious leakage requires intervention. Repair the small intestine in one or two layers, using the initial row of interrupted sutures to approximate the mucosa and muscularis.24 To lessen the risk of stenosis, close all lacerations transversely when they are smaller than one half the diameter of the bowel. If the laceration exceeds that size, segmental resection and anastomosis are necessary. Resection is prudent if the mesenteric blood supply is compromised.25

When performing one-layer repair of the small bowel, delayed absorbable suture (eg, Vicryl or PDS) or nonabsorbable suture (eg, silk) is recommended.26

At the conclusion of a repair, copiously irrigate the entire abdomen. Place a nasogastric tube only if ileus is anticipated; the tube can be removed when drainage diminishes and active bowel sounds and flatus appear. Do not give anything by mouth until the patient has return of bowel function and active peristalsis. Prescribe prophylactic antibiotics.

Note that peritonitis sometimes develops after repair of the bowel.25 This can be managed with prolonged bowel rest and peripheral or total parenteral nutrition.

Conservative management may be possible

Patients whose symptoms of bowel laceration become apparent after discharge can sometimes be managed conservatively. More than 50% of patients treated conservatively require no surgery.23 Inpatient management consists of monitoring the WBC count, providing hydration and IV antibiotics, and examining the patient every 6 hours, giving nothing by mouth.

When injury is discovered later

If conservative management with observation and bowel rest fails, or the patient complains of severe abdominal pain, vomiting, nausea, obstipation, or signs and symptoms of peritonitis, such as the patient in Case 3, immediate surgical intervention is necessary. When an injury is not detected until some time after initial surgery, resection of all necrotic tissue is mandatory. In most cases, the perforation is managed by segmental resection and reanastomosis. Evaluate the entire small and large bowel to rule out any other injury, and irrigate generously. Bowel rest, parenteral nutrition, and IV antibiotics also are indicated.

Of 36,928 procedures reported by members of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists, there were two deaths—both caused by unrecognized bowel injury.15

CASE 4: Large-bowel injury precipitates lengthy recovery

A surgeon performs a left laparoscopic salpingo-oophorectomy to remove an 8-cm ovarian endometrioma that is adherent to the rectosigmoid colon of a 40-year-old diabetic woman. Sharp and electrosurgical scissors are used to separate the adnexa from the rectosigmoid colon. No injury is observed, and she is discharged the same day. Four days later, she returns with severe abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and fatigue. Lab tests reveal a WBC count of 17,000; a CT scan shows pockets of air beneath the diaphragm, as well as fluid collection suggestive of a pelvic abscess.

Immediate laparotomy is performed, during which the surgeon discovers contamination of the abdominal viscera by bowel contents, as well as a 0.5-cm perforation of the rectosigmoid colon. The perforation is repaired in two layers after its edges are trimmed, and a diverting colostomy is performed. The patient is admitted to the ICU and requires antibiotic treatment, total parenteral nutrition, and bowel rest due to severe peritonitis. She gradually recovers and is discharged 3 weeks later. The diverting colostomy is reversed 3 months later.

Even small perforations in the large bowel can cause infection and abscess due to the high bacterial content of the colon. The most common cause of injury to the rectosigmoid colon is pelvic adhesiolysis during cul-de-sac dissection, treatment of pelvic endometriosis, and resection of adherent pelvic masses.

Sharp dissection with scissors or high-powered lasers is relatively safe near the bowel. When dissecting the cul-de-sac, identify the vagina and rectum by placing a probe or finger in each area. Begin dissection from the unaffected pararectal space, and proceed toward the obliterated cul-de-sac.27,28

Bowel prep is indicated before extensive pelvic surgery and when the history suggests endometriosis or significant pelvic adhesions. Some general surgeons base their decision to perform colostomy (or not) on whether the bowel was prepped preoperatively.29

If the large bowel is perforated by the Veress needle, the saline aspiration test will yield brownish fluid. When significant pelvic adhesiolysis or pelvic or endometriotic tumor resection is performed, inject air into the rectum afterward via a sigmoidoscope or bulb syringe and assess the submerged rectum and rectosigmoid colon for bubbling. The rectal wall may be weakened during these types of procedures, so instruct the patient to use oral stool softeners and avoid enemas.30

Delay in detection can have serious ramifications

When a large-bowel injury goes undetected at the time of operation, the patient generally presents on the third or fourth postoperative day with mild fever, occasionally sudden sharp epigastric pain, lower abdominal pain, slight nausea, and anorexia. By the fifth or sixth day, these symptoms have become more severe and are accompanied by peritonitis and an elevated WBC count.

Whenever a patient complains of abdominal pain and a deteriorating condition, assume that bowel injury is the cause until it is proved otherwise.

Intraoperative management

Repair small trocar wounds using primary suture closure. Copious lavage of the peritoneal cavity, drainage, and a broad-spectrum antibiotic minimize the risk of infection. Manage deep electrical injury to the right colon by resecting the injured segment and performing primary anastomosis. Primary closure or resection and reanastomosis may not be adequate when the vascular supply of the descending colon or rectum is compromised. In that case, perform a diverting colostomy or ileostomy, which can be reversed 6 to 12 weeks later.25,26

CASE 5: Vascular injury

A tall, thin, athletic 19-year-old undergoes diagnostic laparoscopy to rule out pelvic pathology after she complains of severe, monthly abdominal pain. Upon insertion of the laparoscope, the surgeon observes a large hematoma forming at the right pelvic sidewall. At the same time, the anesthesiologist reports a significant drop in blood pressure, and vascular injury is diagnosed. The surgeon attempts to control the bleeding using bipolar coagulation, but the problem only becomes worse. He decides to switch to laparotomy.

A vascular surgeon is called in, and injury to the right common iliac artery and vein—apparently caused during insertion of the primary umbilical trocar—is repaired. The patient is given 5 U of red blood cells. She goes home 10 days later, but returns with thrombophlebitis and rejection of the graft. After several surgeries, she finally recovers, with some sequelae, such as unilateral leg edema.

Management of vascular injury depends on the source and type of injury. On major vessels, electrocoagulation is contraindicated. After immediate atraumatic compression with tamponade to control bleeding, vascular repair, in consultation with a vascular surgeon, is indicated. At times, a vascular graft may be required.

Smaller vessels, such as the infundibulopelvic ligament or uterine vessels, can be managed by clips, suture, or loop ligatures. If thermal energy is used in the repair, be careful to avoid injury to surrounding structures.

Most emergency laparotomies are performed for uncontrolled bleeding.30,31 Lack of control or a wrong angle at insertion of the Veress needle and trocars is a major cause of large-vessel injury. Sharp dissection of adhesions, uterosacral ablation, transection of vascular pedicles without adequate dessication, and rough handling of tissues can all cause bleeding. Distorted anatomy is a main cause of vascular injury and can compound injury in areas more prone to bleeding, such as the oviduct, infundibulopelvic ligament, mesosalpinx, and pelvic sidewall vessels.

The return of pressure gradients to normal levels at the end of a procedure can be accompanied by bleeding into the retroperitoneal space, so evaluate the patient in a supine position after intra-abdominal pressure is reduced.

A vascular surgeon may be required

Depending on the type of vessel, size and location of the injury, and degree of bleeding, you may use unipolar or bipolar electrocoagulation, suture, clips, vasopressin, or loop ligatures to control bleeding. Although diluted vasopressin (10 U in 60 mL of lactated Ringer’s saline) can decrease oozing from raw peritoneal areas, injury to a major vessel, such as the iliac vessels, vena cava, or aorta, needs immediate control and proper repair. The decision to perform laparoscopy or laparotomy depends on your preference and experience. In any case, a vascular surgeon may be consulted for major vascular injuries.32

If a major vessel is injured, do not crush-clamp it. If possible (and if your laparoscopic skills are advanced), insert a sponge via a 10-mm trocar and apply pressure to the vessel to minimize bleeding and enhance visualization. The decision to repair the injury laparoscopically or by laparotomy should be made judiciously and promptly. n

The authors acknowledge the editorial contributions of Kristina Petrasek and Barbara Page, of the University of California, Berkeley, to the manuscript of this article.

1. Ostrzenski A, Radolinski B, Ostrzenska K. A review of laparoscopic ureteral injury in pelvic surgery. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2003;58:794-799.

2. Kabalin J. Chapter 1—Surgical anatomy of the retroperitoneum, kidneys, and ureters. In: Walsh P, Retik A, Wein A, eds. Campbell’s Urology. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2002 36-40.

3. Chan J, Morrow J, Manetta A. Prevention of ureteral injuries in gynecologic surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:1273-1277.

4. Grainger DA, Soderstrom RM, Schiff SF, Glickman MG, DeCherney AH, Diamond MP. Ureteral injuries at laparoscopy: insights into diagnosis, management, and prevention. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75:839-843.

5. Nezhat C. Chapter 20. Operative Gynecologic Laparoscopy: Principles and Techniques. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw–Hill; 2000.

6. Ou CS, Huang IA, Rowbotham R. Laparoscopic ureteroureteral anastomosis for repair of ureteral injury involving stricture. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2005;16:155-157.

7. Modi P, Goel R, Dodiya S. Laparoscopic ureteroneocystostomy for distal ureteral injuries. Urology. 2005;66:751-753.

8. Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat CH, et al. Urinary tract endometriosis treated by laparoscopy. Fertil Steril. 1996;66:920-924.

9. Nezhat C, Nezhat F. Laparoscopic repair of ureter resected during operative laparoscopy. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;80:543-544.

10. Nezhat CH, Nezhat FR, Freiha F, Nezhat CR. Laparoscopic vesicopsoas hitch for infiltrative ureteral endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1999;71:376-379.

11. Georgy FM, Fettman HH, Chefetz MD. Complications of laparoscopy: two cases of perforated urinary bladder. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1974;120:1121-1122.

12. Sherer DM. Inadvertent transvaginal cystotomy during laparoscopy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1990;32:77-79.

13. Nezhat CH, Seidman DS, Nezhat F, et al. Laparoscopic management of internal and unintentional cystotomy. J Urol. 1996;156:1400-1402.

14. Lee CL, Lai YM, Soong YK. Management of urinary bladder injuries in laparoscopic assisted vaginal hysterectomy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1996;75:174-177.

15. Peterson HB, et al. American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists’ 1988 membership survey on operative laparoscopy. J Reprod Med. 1990;35:587-589.

16. Phillips JM, Hulka JF, Hulka B, et al. 1978 AAGL membership survey. J Reprod Med. 1981;26:529-533.

17. Chapron C, Pierre F, et al. Gastrointestinal injuries during laparoscopy. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:333-337.

18. Schrenk P, Woisetschlager R, Rieger R, et al. Mechanism, management, and prevention of laparoscopic bowel injuries. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;43:572-574.

19. Sauer M, Jarrett JC. Small bowel obstruction following diagnostic laparoscopy. Fertil Steril. 1984;42:653-654.

20. Penfield AJ. How to prevent complications of open laparoscopy. J Reprod Med. 1985;30:660-663.

21. Brill A, Nezhat F, Nezhat CH, Nezhat C. The incidence of adhesions after prior laparatomy: a laparoscopic appraisal. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85:269-272.

22. Levy BS, Soderstrom RM, Dail DH. Bowel injuries during laparoscopy: gross anatomy and histology. J Reprod Med. 1985;30:168-172.

23. Wheeless CR. Gastrointestinal injuries associated with laparoscopy. In: Phillips JM, ed. Endoscopy in Gynecology. Santa Fe Springs, Calif: American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists; 1978.

24. Borton M. Laparoscopic Complications: Prevention and Management. Philadelphia: Decker; 1986.

25. DeCherney AH. Laparoscopy with unexpected viscus penetration. In: Nichols DH, ed. Clinical Problems, Injuries, and Complications of Gynecologic Surgery. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1988.

26. Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Ambroze W, Pennington E. Laparoscopic repair of small bowel and colon: a report of 26 cases. Surg Endosc. 1993;7:88-89.

27. Redwine D. Laparoscopic en bloc resection for treatment of the obliterated cul-de-sac in endometriosis. J Reprod Med. 1992;37:696-698.

28. Nezhat C, Nezhat F, et al. Laparoscopic treatment of infiltrative rectosigmoid colon and rectovaginal septum endometriosis by the technique of videolaseroscopy and the CO2 laser. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;99:664-667.

29. Nezhat C, Seidman D, Nezhat F, et al. The role of intraoperative proctosigmoidoscopy in laparoscopic pelvic surgery. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2004;11:47-49.

30. Chapron CM, et al. Major vascular injuries during gynecologic laparoscopy. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;185:461-465.

31. Geers J, Holden C. Major vascular injury as a complication of laparoscopic surgery: a report of three cases and review of the literature. Am Surg. 1996;62:377-379.

32. Nezhat C, Childers J, Nezhat F, et al. Major retroperitoneal vascular injury during laparoscopic surgery. Hum Reprod. 1997;12:480-483.

Dr. Farr Nezhat reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Ceana Nezhat is a speaker and consultant for Karl Storz, Johnson & Johnson, Valleylab, US Surgical, and Viking. Dr. Camran Nezhat is a speaker for or receives educational support from Karl Storz, Stryker, Johnson & Johnson, Valleylab, and Baxter.

To view three clips of surgical pearls for laparoscopy, visit the Video Library.

<huc>Q.</huc>What is the only surgical procedure that is completely safe?

<huc>A.</huc>The surgical procedure that is not performed.

The unfortunate truth is that complications can occur during any operative procedure, despite our best efforts—and laparoscopy is no exception. Being vigilant for iatrogenic injuries, both during and after surgery, and ensuring that repairs are both thorough and timely, are two of our best weapons against major complications, along with meticulous technique and adequate experience.

This article features five cases that illustrate some of the most serious complications of laparoscopy—and how to prevent and manage them.

CASE 1: Surgical patient returns with signs of ureteral injury

A 42-year-old woman with a history of endometriosis undergoes laparoscopic hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. She is discharged 2 days later. Two days after that, she returns to the hospital complaining of fluid leaking from the vagina. She has no fever or any other significant complaint or physical findings other than abdominal tenderness, which is to be expected after surgery. A computed tomography (CT) scan with intravenous (IV) contrast reveals left ureteral obstruction near the bladder, with extravasation of contrast media into the abdominal cavity. Further investigation reveals a left ureteral transection.

Could this injury have been avoided? How should it be managed?

Postoperative diagnosis of ureteral injury can be challenging, in part because up to 50% of unilateral cases are asymptomatic. Be on the lookout for this complication in women who have undergone pelvic sidewall dissection or laparoscopic hysterectomy, such as the patient in the case just described. As the number of laparoscopic hysterectomies and retroperitoneal procedures has risen in recent years, so has the rate of ureteral injury, with an incidence of 0.3% to 2%.1,2

Ureteral injury can be caused by ligation, ischemia, resection, transection, crushing, or angulation. Three sites are particularly troublesome: the infundibulopelvic ligament, ovarian fossa, and ureteral tunnel.3,4 In Case 1, injury to the ureter was proximal to the bladder and probably occurred during transection of the uterosacral cardinal ligament complex.

What’s the best preventive strategy?

Meticulous technique is imperative to protect the ureters. This includes adequate visualization, intraperitoneal or retroperitoneal dissection, and early identification of the ureter. In a high-risk patient likely to have distorted anatomy due to severe endometriosis and fibrosis, retroperitoneal dissection of any adhesions or tumor and identification of the ureter are the best ways to avoid injury.

Intraperitoneal identification and dissection of the ureters can be enhanced by hydrodissection and resection of the affected peritoneum.3,4 To create a safe operating plane, make a small opening in the peritoneum below the ureter and inject 50 to 100 mL of lactated Ringer’s solution along the course of the ureter, which will displace it laterally.5

Although neither IV indigo carmine nor ureteral catheterization has been shown to reduce the risk of ureteral injury or identify ligation or thermal injury,3,6 both can help the surgeon identify intraoperative perforation of the ureter. Liberal use of cystoscopy with indigo carmine administration for identification of ureteral flow and ureteral catheterization can be used in potentially high-risk patients. If there is suspicion for devascularization or thermal injury, use prophylactic ureteral stents postoperatively for 2 to 4 weeks.

Don’t hesitate to consult a urologist

In Case 1, the surgeon sought immediate urologic consultation and the patient underwent laparotomy with ureteroneocystotomy without sequelae.

In general, management of ureteral injury depends on its severity and location, as well as the comfort level of the surgeon. Minor injuries are sometimes managed with cystoscopic stent placement, but more severe cases may require operative ureteral repair.

In cases like this one, where ureteral injury occurred in close proximity to the bladder, a ureteroneocystotomy is possible. However, in more cephalad injuries, there may be insufficient residual ureter to allow such a repair. In these cases, a Boari flap may be attempted to use bladder tissue to bridge the gap to the ureteral edge. Rarely, in high ureteral injuries, trans-ureteroureterostomy may be appropriate. This procedure carries the greatest risk, given that both kidneys are reliant on one ureter.

Is laparoscopic repair reasonable?

When surgical intervention is necessary, the choice between laparoscopy and laparotomy depends on the skill and comfort level of the surgeon and the availability of instruments and support team.6,7 That said, ureteral injury is usually treated via laparotomy.1 As operative laparoscopy becomes even more commonplace, reconstruction of the urinary system will increasingly be managed laparoscopically.

Depending on the size and location of the injury, reconstruction may involve ureteral reimplantation with or without a psoas hitch, Boari flap, or primary endtoend anastomosis.8-10

CASE 2: Postoperative symptoms lead to rehospitalization

A 35-year-old patient undergoes laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy and returns home the same day. She is readmitted 72 hours later because of lower abdominal tenderness, worsening nausea and vomiting, and urine-like drainage from her midline suprapubic trocar site. Analysis of the leaking fluid shows high creatinine levels consistent with urine. The patient has no fever and is hemodynamically stable. Examination reveals a moderately distended abdomen with decreased bowel sounds. Hematuria is evident on urine analysis.

Urologic consultation is obtained, and the patient undergoes simultaneous laparoscopy and cystoscopy, during which perforation of the bladder dome is discovered, apparently caused by the mid suprapubic trocar. The bladder is mobilized anteriorly, and both anterior and posterior aspects of the perforation are repaired in one layer laparoscopically.

After continuous drainage with a transurethral Foley catheter for 7 days, cystography shows complete healing of the bladder, and the Foley catheter is removed. The patient recovers completely.

Vesical injury sometimes occurs in patients who have a history of laparotomy, a full bladder at the time of surgery, or displaced anatomy due to pelvic adhesions.11 Although bladder injury is rare, laparoscopy increases the risk. Trocars, uterine manipulators, and blunt instruments can perforate or lacerate the bladder, and energy devices can cause thermal injury. The risk of bladder injury increases during laparoscopic hysterectomy.

Be vigilant about trocar placement and dissection techniques

Accessory trocars can injure a full bladder. Injury can also occur when distorted anatomy from a previous pelvic operation obscures bladder boundaries, making insertion of the midline trocar potentially perilous (FIGURE 1). The Veress needle and Rubin’s cannula can perforate the bladder.11-13 And in the anterior cul-de-sac, adhesiolysis, deep coagulation, laser ablation, or sharp excision of endometriosis implants can predispose a patient to bladder injury.

In women with severe endometriosis, lower-segment myoma, or a history of cesarean section, the bladder is vulnerable to laceration when blunt dissection is used during laparoscopic hysterectomy or laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy (LAVH). A vesical injury also can occur at the time of laparoscopic bladder-neck suspension upon entry into, and dissection of, the space of Retzius.

FIGURE 1 A bladder at risk

In this patient with a previous cesarean section, the bladder is adherent to the anterior abdominal wall. Needle mapping in the conventional midline trocar position indicates that the trocar must be relocated to avoid bladder injury.

Intraoperative findings that suggest bladder injury include air in the urinary catheter, hematuria, trocar site drainage of urine, or indigo carmine leakage. Postoperative signs and symptoms include leaking from incisional sites, a mass in the abdominal wall, and abdominal swelling.

Liberal use of cystoscopy or distension of the bladder with 300 to 500 mL of normal saline is recommended whenever there is a suspicion of bladder injury, especially during laparoscopic hysterectomy or LAVH. When a trocar causes the injury, look for both entry and exit punctures, both of which should be treated.

No matter how much care is taken, some bladder injuries, such as vesicovaginal fistulae, become apparent only postoperatively. More rarely, peritonitis or pseudoascites herald the injury. Retrograde cystography may aid identification.

Treatment of bladder injuries

Small perforations recognized intraoperatively may be conservatively managed by postoperative bladder drainage for 5 to 7 days. Most other bladder injuries require prompt intervention. For example, trocar injury to the bladder dome requires one- or two-layer closure followed by 5 to 7 days of urinary drainage. (Both closing and healing are promoted by drainage.)

Laparoscopy or laparotomy? Laparoscopic repair has become increasingly common, and bladder injury is a common complication of LAVH.13,14

CASE 3: Postop pain, tachycardia

A 41-year-old obese woman undergoes laparoscopic cystectomy for an 8-cm left ovarian mass. The abdomen is entered on the second attempt with a long Veress needle. The umbilical trocar is reinserted “several” times because of difficulty opening the peritoneum with the tip of the trocar sheath. The surgical procedure is completed within 2 hours, and the patient is discharged 23 hours later.

The next day, she experiences increasing abdominal pain and presents to the emergency room. Upon admission she reports intermittent chills, but denies nausea and vomiting. She is in mild distress, pale and tachycardic, with a temperature of 96.4°, pulse of 117, respiration rate of 20, blood pressure of 106/64 mm Hg, and oxygen saturation of 92%. She also has a diffusely tender abdomen but normal blood work. Abdominal and chest x-rays show a large right subphrenic air-fluid level that is consistent with free intraperitoneal air, unsurprising given her recent surgery. Bibasilar atelectasis and consolidation are noted on the initial chest x-ray.

During observation over the next 2 days, she remains afebrile and tachycardic, but her shortness of breath becomes progressively worse. Neither spiral CT nor lower-extremity Doppler suggests pulmonary embolism or deep venous thrombosis. Supplemental oxygen, aggressive pain management, albuterol, ipratropium, and acetylcysteine are initiated after pulmonary consultation.

The patient tolerates a regular diet on postoperative day 3 and has a bowel movement on day 5. However, the same day she begins vomiting and reports worsening abdominal pain. CT imaging of the abdomen and pelvis reveals free air in the abdomen and loculated fluid with air bubbles suspicious for intra-abdominal infection and perforated bowel.

Exploratory laparotomy reveals diffuse feculent peritonitis, as well as food particles and contrast media. There is a perforation in the antimesenteric side of the ileum approximately 1.5 feet proximal to the ileocecal valve. This perforation measures approximately 1 cm in diameter and is freely spilling intestinal contents. Small bowel resection is performed to treat the perforation.

Following the surgery, the patient recovers slowly.

Could the bowel perforation have been detected sooner?

Intestinal tract injury is a serious complication, particularly with postoperative diagnosis.15 Damage can occur during insertion of the Veress needle or trocar when the bowel is immobilized by adhesions, or during enterolysis.16 Unrecognized thermal injury can cause delayed bowel injury.

Small-bowel damage often occurs during uncontrolled insertion of the Veress needle or primary umbilical trocar. It also may result from sharp dissection or thermal injury.17,18 Abrasions and lacerations can occur if traction is exerted on the bowel using serrated graspers. When adhesions are dense and tissue planes poorly defined, the risk of laceration due to energy sources or sharp dissection increases.

Be cautious during bowel manipulation. Avoid blunt dissection. Be especially careful when the small bowel is adherent to the anterior abdominal wall (FIGURE 2A), particularly during evaluation of patients with a history of bowel resection, exploratory laparotomy for trauma-related peritonitis, or tumor debulking.

Remove the primary and ancillary cannulas under direct visualization with the laparoscope to prevent formation of a vacuum that can draw bowel into the incision and cause herniation.19

FIGURE 2 Adherent bowel, minor bleeding

A: Veress needle pressure measurements are persistently elevated before primary trocar insertion in this patient, raising the suspicion of adhesive disease from earlier surgery. As a result, the primary trocar is relocated to the left upper quadrant. Inspection confirms that small bowel is adherent to the anterior abdominal wall.

FIGURE 2 Adherent bowel, minor bleeding

B: After the small-bowel adhesions are dissected off the anterior abdominal wall via laparoscopy, a small hematoma is discovered, likely caused by the Veress needle. The patient is managed conservatively and recovers.

The value of open laparoscopy

In open laparoscopy, an abdominal incision is made into the peritoneal cavity so that the trocar can be placed under direct vision, after which the abdomen is insufflated. This approach can prevent bowel injury only when the adhesions and attachments are to the anterior abdominal wall and away from the entry site. When the attachment lies directly beneath the umbilicus, however, open laparoscopy is no guarantee against injury.

When bowel adhesions are severe, use alternative trocar sites such as the left upper quadrant (Palmer’s point) for the Veress needle and primary trocars.5,20,21

The likelihood of perforation can be reduced with preoperative bowel prep when there is a risk of bowel adhesions.

Identifying bowel injury

We recommend routine inspection of the structures beneath the primary trocar upon insertion of the laparoscope to look for injury to the bowel, mesentery, or vascular structures. If adhesions are found, evaluate the area carefully to rule out injury to the bowel or omentum. It may be necessary to change the position of the laparoscope to assess the patient.

Trauma to the intestinal tract can be mechanical or electrical in nature, and each type of trauma creates a distinctive, characteristic pattern. Thermal injury can be subtle and present as simple blanching or a distinct burn and charring. A small hole or obvious tear in the bowel wall can be the result of mechanical injury.22

Benign-appearing, superficial thermal bowel injuries may be managed conservatively.22 Minimal serosal burns (smaller than 5 mm in diameter) can be managed expectantly. Immediate surgical intervention is needed if the area of blanching on the intestinal serosa exceeds 5 mm in diameter or if the burn appears to involve more than the serosa.23

Small-bowel injuries that escape notice intraoperatively generally become apparent 2 to 4 days later, when the patient develops fever, nausea, lower abdominal pain, and anorexia. On postoperative day 5 or 6, the white blood cell (WBC) count rises and earlier symptoms may become worse. Radiography may reveal multiple air and fluid levels—another sign of bowel injury. Be aware that if the patient has clinical symptoms of gastrointestinal injury, even if the WBC count is normal, exploratory laparoscopy or laparotomy is necessary for accurate diagnosis.

Intraoperatively discovered injury

Careful inspection may reveal no leakage or bleeding in the affected area. Small punctures or superficial lacerations seal readily and may not require further treatment (FIGURE 2B), but larger perforations require repair. Straightforward repair is not always possible when the injury is extensive and considerable time has elapsed before it is discovered.

Inspect the intestine thoroughly at the conclusion of a procedure; obvious leakage requires intervention. Repair the small intestine in one or two layers, using the initial row of interrupted sutures to approximate the mucosa and muscularis.24 To lessen the risk of stenosis, close all lacerations transversely when they are smaller than one half the diameter of the bowel. If the laceration exceeds that size, segmental resection and anastomosis are necessary. Resection is prudent if the mesenteric blood supply is compromised.25

When performing one-layer repair of the small bowel, delayed absorbable suture (eg, Vicryl or PDS) or nonabsorbable suture (eg, silk) is recommended.26

At the conclusion of a repair, copiously irrigate the entire abdomen. Place a nasogastric tube only if ileus is anticipated; the tube can be removed when drainage diminishes and active bowel sounds and flatus appear. Do not give anything by mouth until the patient has return of bowel function and active peristalsis. Prescribe prophylactic antibiotics.

Note that peritonitis sometimes develops after repair of the bowel.25 This can be managed with prolonged bowel rest and peripheral or total parenteral nutrition.

Conservative management may be possible

Patients whose symptoms of bowel laceration become apparent after discharge can sometimes be managed conservatively. More than 50% of patients treated conservatively require no surgery.23 Inpatient management consists of monitoring the WBC count, providing hydration and IV antibiotics, and examining the patient every 6 hours, giving nothing by mouth.

When injury is discovered later

If conservative management with observation and bowel rest fails, or the patient complains of severe abdominal pain, vomiting, nausea, obstipation, or signs and symptoms of peritonitis, such as the patient in Case 3, immediate surgical intervention is necessary. When an injury is not detected until some time after initial surgery, resection of all necrotic tissue is mandatory. In most cases, the perforation is managed by segmental resection and reanastomosis. Evaluate the entire small and large bowel to rule out any other injury, and irrigate generously. Bowel rest, parenteral nutrition, and IV antibiotics also are indicated.

Of 36,928 procedures reported by members of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists, there were two deaths—both caused by unrecognized bowel injury.15

CASE 4: Large-bowel injury precipitates lengthy recovery

A surgeon performs a left laparoscopic salpingo-oophorectomy to remove an 8-cm ovarian endometrioma that is adherent to the rectosigmoid colon of a 40-year-old diabetic woman. Sharp and electrosurgical scissors are used to separate the adnexa from the rectosigmoid colon. No injury is observed, and she is discharged the same day. Four days later, she returns with severe abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and fatigue. Lab tests reveal a WBC count of 17,000; a CT scan shows pockets of air beneath the diaphragm, as well as fluid collection suggestive of a pelvic abscess.

Immediate laparotomy is performed, during which the surgeon discovers contamination of the abdominal viscera by bowel contents, as well as a 0.5-cm perforation of the rectosigmoid colon. The perforation is repaired in two layers after its edges are trimmed, and a diverting colostomy is performed. The patient is admitted to the ICU and requires antibiotic treatment, total parenteral nutrition, and bowel rest due to severe peritonitis. She gradually recovers and is discharged 3 weeks later. The diverting colostomy is reversed 3 months later.

Even small perforations in the large bowel can cause infection and abscess due to the high bacterial content of the colon. The most common cause of injury to the rectosigmoid colon is pelvic adhesiolysis during cul-de-sac dissection, treatment of pelvic endometriosis, and resection of adherent pelvic masses.

Sharp dissection with scissors or high-powered lasers is relatively safe near the bowel. When dissecting the cul-de-sac, identify the vagina and rectum by placing a probe or finger in each area. Begin dissection from the unaffected pararectal space, and proceed toward the obliterated cul-de-sac.27,28

Bowel prep is indicated before extensive pelvic surgery and when the history suggests endometriosis or significant pelvic adhesions. Some general surgeons base their decision to perform colostomy (or not) on whether the bowel was prepped preoperatively.29

If the large bowel is perforated by the Veress needle, the saline aspiration test will yield brownish fluid. When significant pelvic adhesiolysis or pelvic or endometriotic tumor resection is performed, inject air into the rectum afterward via a sigmoidoscope or bulb syringe and assess the submerged rectum and rectosigmoid colon for bubbling. The rectal wall may be weakened during these types of procedures, so instruct the patient to use oral stool softeners and avoid enemas.30

Delay in detection can have serious ramifications

When a large-bowel injury goes undetected at the time of operation, the patient generally presents on the third or fourth postoperative day with mild fever, occasionally sudden sharp epigastric pain, lower abdominal pain, slight nausea, and anorexia. By the fifth or sixth day, these symptoms have become more severe and are accompanied by peritonitis and an elevated WBC count.

Whenever a patient complains of abdominal pain and a deteriorating condition, assume that bowel injury is the cause until it is proved otherwise.

Intraoperative management

Repair small trocar wounds using primary suture closure. Copious lavage of the peritoneal cavity, drainage, and a broad-spectrum antibiotic minimize the risk of infection. Manage deep electrical injury to the right colon by resecting the injured segment and performing primary anastomosis. Primary closure or resection and reanastomosis may not be adequate when the vascular supply of the descending colon or rectum is compromised. In that case, perform a diverting colostomy or ileostomy, which can be reversed 6 to 12 weeks later.25,26

CASE 5: Vascular injury

A tall, thin, athletic 19-year-old undergoes diagnostic laparoscopy to rule out pelvic pathology after she complains of severe, monthly abdominal pain. Upon insertion of the laparoscope, the surgeon observes a large hematoma forming at the right pelvic sidewall. At the same time, the anesthesiologist reports a significant drop in blood pressure, and vascular injury is diagnosed. The surgeon attempts to control the bleeding using bipolar coagulation, but the problem only becomes worse. He decides to switch to laparotomy.

A vascular surgeon is called in, and injury to the right common iliac artery and vein—apparently caused during insertion of the primary umbilical trocar—is repaired. The patient is given 5 U of red blood cells. She goes home 10 days later, but returns with thrombophlebitis and rejection of the graft. After several surgeries, she finally recovers, with some sequelae, such as unilateral leg edema.

Management of vascular injury depends on the source and type of injury. On major vessels, electrocoagulation is contraindicated. After immediate atraumatic compression with tamponade to control bleeding, vascular repair, in consultation with a vascular surgeon, is indicated. At times, a vascular graft may be required.

Smaller vessels, such as the infundibulopelvic ligament or uterine vessels, can be managed by clips, suture, or loop ligatures. If thermal energy is used in the repair, be careful to avoid injury to surrounding structures.

Most emergency laparotomies are performed for uncontrolled bleeding.30,31 Lack of control or a wrong angle at insertion of the Veress needle and trocars is a major cause of large-vessel injury. Sharp dissection of adhesions, uterosacral ablation, transection of vascular pedicles without adequate dessication, and rough handling of tissues can all cause bleeding. Distorted anatomy is a main cause of vascular injury and can compound injury in areas more prone to bleeding, such as the oviduct, infundibulopelvic ligament, mesosalpinx, and pelvic sidewall vessels.

The return of pressure gradients to normal levels at the end of a procedure can be accompanied by bleeding into the retroperitoneal space, so evaluate the patient in a supine position after intra-abdominal pressure is reduced.

A vascular surgeon may be required

Depending on the type of vessel, size and location of the injury, and degree of bleeding, you may use unipolar or bipolar electrocoagulation, suture, clips, vasopressin, or loop ligatures to control bleeding. Although diluted vasopressin (10 U in 60 mL of lactated Ringer’s saline) can decrease oozing from raw peritoneal areas, injury to a major vessel, such as the iliac vessels, vena cava, or aorta, needs immediate control and proper repair. The decision to perform laparoscopy or laparotomy depends on your preference and experience. In any case, a vascular surgeon may be consulted for major vascular injuries.32

If a major vessel is injured, do not crush-clamp it. If possible (and if your laparoscopic skills are advanced), insert a sponge via a 10-mm trocar and apply pressure to the vessel to minimize bleeding and enhance visualization. The decision to repair the injury laparoscopically or by laparotomy should be made judiciously and promptly. n

The authors acknowledge the editorial contributions of Kristina Petrasek and Barbara Page, of the University of California, Berkeley, to the manuscript of this article.

To view three clips of surgical pearls for laparoscopy, visit the Video Library.

<huc>Q.</huc>What is the only surgical procedure that is completely safe?

<huc>A.</huc>The surgical procedure that is not performed.

The unfortunate truth is that complications can occur during any operative procedure, despite our best efforts—and laparoscopy is no exception. Being vigilant for iatrogenic injuries, both during and after surgery, and ensuring that repairs are both thorough and timely, are two of our best weapons against major complications, along with meticulous technique and adequate experience.

This article features five cases that illustrate some of the most serious complications of laparoscopy—and how to prevent and manage them.

CASE 1: Surgical patient returns with signs of ureteral injury

A 42-year-old woman with a history of endometriosis undergoes laparoscopic hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. She is discharged 2 days later. Two days after that, she returns to the hospital complaining of fluid leaking from the vagina. She has no fever or any other significant complaint or physical findings other than abdominal tenderness, which is to be expected after surgery. A computed tomography (CT) scan with intravenous (IV) contrast reveals left ureteral obstruction near the bladder, with extravasation of contrast media into the abdominal cavity. Further investigation reveals a left ureteral transection.

Could this injury have been avoided? How should it be managed?

Postoperative diagnosis of ureteral injury can be challenging, in part because up to 50% of unilateral cases are asymptomatic. Be on the lookout for this complication in women who have undergone pelvic sidewall dissection or laparoscopic hysterectomy, such as the patient in the case just described. As the number of laparoscopic hysterectomies and retroperitoneal procedures has risen in recent years, so has the rate of ureteral injury, with an incidence of 0.3% to 2%.1,2

Ureteral injury can be caused by ligation, ischemia, resection, transection, crushing, or angulation. Three sites are particularly troublesome: the infundibulopelvic ligament, ovarian fossa, and ureteral tunnel.3,4 In Case 1, injury to the ureter was proximal to the bladder and probably occurred during transection of the uterosacral cardinal ligament complex.

What’s the best preventive strategy?

Meticulous technique is imperative to protect the ureters. This includes adequate visualization, intraperitoneal or retroperitoneal dissection, and early identification of the ureter. In a high-risk patient likely to have distorted anatomy due to severe endometriosis and fibrosis, retroperitoneal dissection of any adhesions or tumor and identification of the ureter are the best ways to avoid injury.

Intraperitoneal identification and dissection of the ureters can be enhanced by hydrodissection and resection of the affected peritoneum.3,4 To create a safe operating plane, make a small opening in the peritoneum below the ureter and inject 50 to 100 mL of lactated Ringer’s solution along the course of the ureter, which will displace it laterally.5

Although neither IV indigo carmine nor ureteral catheterization has been shown to reduce the risk of ureteral injury or identify ligation or thermal injury,3,6 both can help the surgeon identify intraoperative perforation of the ureter. Liberal use of cystoscopy with indigo carmine administration for identification of ureteral flow and ureteral catheterization can be used in potentially high-risk patients. If there is suspicion for devascularization or thermal injury, use prophylactic ureteral stents postoperatively for 2 to 4 weeks.

Don’t hesitate to consult a urologist

In Case 1, the surgeon sought immediate urologic consultation and the patient underwent laparotomy with ureteroneocystotomy without sequelae.

In general, management of ureteral injury depends on its severity and location, as well as the comfort level of the surgeon. Minor injuries are sometimes managed with cystoscopic stent placement, but more severe cases may require operative ureteral repair.

In cases like this one, where ureteral injury occurred in close proximity to the bladder, a ureteroneocystotomy is possible. However, in more cephalad injuries, there may be insufficient residual ureter to allow such a repair. In these cases, a Boari flap may be attempted to use bladder tissue to bridge the gap to the ureteral edge. Rarely, in high ureteral injuries, trans-ureteroureterostomy may be appropriate. This procedure carries the greatest risk, given that both kidneys are reliant on one ureter.

Is laparoscopic repair reasonable?

When surgical intervention is necessary, the choice between laparoscopy and laparotomy depends on the skill and comfort level of the surgeon and the availability of instruments and support team.6,7 That said, ureteral injury is usually treated via laparotomy.1 As operative laparoscopy becomes even more commonplace, reconstruction of the urinary system will increasingly be managed laparoscopically.

Depending on the size and location of the injury, reconstruction may involve ureteral reimplantation with or without a psoas hitch, Boari flap, or primary endtoend anastomosis.8-10

CASE 2: Postoperative symptoms lead to rehospitalization

A 35-year-old patient undergoes laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy and returns home the same day. She is readmitted 72 hours later because of lower abdominal tenderness, worsening nausea and vomiting, and urine-like drainage from her midline suprapubic trocar site. Analysis of the leaking fluid shows high creatinine levels consistent with urine. The patient has no fever and is hemodynamically stable. Examination reveals a moderately distended abdomen with decreased bowel sounds. Hematuria is evident on urine analysis.

Urologic consultation is obtained, and the patient undergoes simultaneous laparoscopy and cystoscopy, during which perforation of the bladder dome is discovered, apparently caused by the mid suprapubic trocar. The bladder is mobilized anteriorly, and both anterior and posterior aspects of the perforation are repaired in one layer laparoscopically.

After continuous drainage with a transurethral Foley catheter for 7 days, cystography shows complete healing of the bladder, and the Foley catheter is removed. The patient recovers completely.

Vesical injury sometimes occurs in patients who have a history of laparotomy, a full bladder at the time of surgery, or displaced anatomy due to pelvic adhesions.11 Although bladder injury is rare, laparoscopy increases the risk. Trocars, uterine manipulators, and blunt instruments can perforate or lacerate the bladder, and energy devices can cause thermal injury. The risk of bladder injury increases during laparoscopic hysterectomy.

Be vigilant about trocar placement and dissection techniques

Accessory trocars can injure a full bladder. Injury can also occur when distorted anatomy from a previous pelvic operation obscures bladder boundaries, making insertion of the midline trocar potentially perilous (FIGURE 1). The Veress needle and Rubin’s cannula can perforate the bladder.11-13 And in the anterior cul-de-sac, adhesiolysis, deep coagulation, laser ablation, or sharp excision of endometriosis implants can predispose a patient to bladder injury.

In women with severe endometriosis, lower-segment myoma, or a history of cesarean section, the bladder is vulnerable to laceration when blunt dissection is used during laparoscopic hysterectomy or laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy (LAVH). A vesical injury also can occur at the time of laparoscopic bladder-neck suspension upon entry into, and dissection of, the space of Retzius.

FIGURE 1 A bladder at risk

In this patient with a previous cesarean section, the bladder is adherent to the anterior abdominal wall. Needle mapping in the conventional midline trocar position indicates that the trocar must be relocated to avoid bladder injury.

Intraoperative findings that suggest bladder injury include air in the urinary catheter, hematuria, trocar site drainage of urine, or indigo carmine leakage. Postoperative signs and symptoms include leaking from incisional sites, a mass in the abdominal wall, and abdominal swelling.

Liberal use of cystoscopy or distension of the bladder with 300 to 500 mL of normal saline is recommended whenever there is a suspicion of bladder injury, especially during laparoscopic hysterectomy or LAVH. When a trocar causes the injury, look for both entry and exit punctures, both of which should be treated.

No matter how much care is taken, some bladder injuries, such as vesicovaginal fistulae, become apparent only postoperatively. More rarely, peritonitis or pseudoascites herald the injury. Retrograde cystography may aid identification.

Treatment of bladder injuries

Small perforations recognized intraoperatively may be conservatively managed by postoperative bladder drainage for 5 to 7 days. Most other bladder injuries require prompt intervention. For example, trocar injury to the bladder dome requires one- or two-layer closure followed by 5 to 7 days of urinary drainage. (Both closing and healing are promoted by drainage.)

Laparoscopy or laparotomy? Laparoscopic repair has become increasingly common, and bladder injury is a common complication of LAVH.13,14

CASE 3: Postop pain, tachycardia

A 41-year-old obese woman undergoes laparoscopic cystectomy for an 8-cm left ovarian mass. The abdomen is entered on the second attempt with a long Veress needle. The umbilical trocar is reinserted “several” times because of difficulty opening the peritoneum with the tip of the trocar sheath. The surgical procedure is completed within 2 hours, and the patient is discharged 23 hours later.

The next day, she experiences increasing abdominal pain and presents to the emergency room. Upon admission she reports intermittent chills, but denies nausea and vomiting. She is in mild distress, pale and tachycardic, with a temperature of 96.4°, pulse of 117, respiration rate of 20, blood pressure of 106/64 mm Hg, and oxygen saturation of 92%. She also has a diffusely tender abdomen but normal blood work. Abdominal and chest x-rays show a large right subphrenic air-fluid level that is consistent with free intraperitoneal air, unsurprising given her recent surgery. Bibasilar atelectasis and consolidation are noted on the initial chest x-ray.

During observation over the next 2 days, she remains afebrile and tachycardic, but her shortness of breath becomes progressively worse. Neither spiral CT nor lower-extremity Doppler suggests pulmonary embolism or deep venous thrombosis. Supplemental oxygen, aggressive pain management, albuterol, ipratropium, and acetylcysteine are initiated after pulmonary consultation.

The patient tolerates a regular diet on postoperative day 3 and has a bowel movement on day 5. However, the same day she begins vomiting and reports worsening abdominal pain. CT imaging of the abdomen and pelvis reveals free air in the abdomen and loculated fluid with air bubbles suspicious for intra-abdominal infection and perforated bowel.

Exploratory laparotomy reveals diffuse feculent peritonitis, as well as food particles and contrast media. There is a perforation in the antimesenteric side of the ileum approximately 1.5 feet proximal to the ileocecal valve. This perforation measures approximately 1 cm in diameter and is freely spilling intestinal contents. Small bowel resection is performed to treat the perforation.

Following the surgery, the patient recovers slowly.

Could the bowel perforation have been detected sooner?

Intestinal tract injury is a serious complication, particularly with postoperative diagnosis.15 Damage can occur during insertion of the Veress needle or trocar when the bowel is immobilized by adhesions, or during enterolysis.16 Unrecognized thermal injury can cause delayed bowel injury.

Small-bowel damage often occurs during uncontrolled insertion of the Veress needle or primary umbilical trocar. It also may result from sharp dissection or thermal injury.17,18 Abrasions and lacerations can occur if traction is exerted on the bowel using serrated graspers. When adhesions are dense and tissue planes poorly defined, the risk of laceration due to energy sources or sharp dissection increases.

Be cautious during bowel manipulation. Avoid blunt dissection. Be especially careful when the small bowel is adherent to the anterior abdominal wall (FIGURE 2A), particularly during evaluation of patients with a history of bowel resection, exploratory laparotomy for trauma-related peritonitis, or tumor debulking.

Remove the primary and ancillary cannulas under direct visualization with the laparoscope to prevent formation of a vacuum that can draw bowel into the incision and cause herniation.19

FIGURE 2 Adherent bowel, minor bleeding

A: Veress needle pressure measurements are persistently elevated before primary trocar insertion in this patient, raising the suspicion of adhesive disease from earlier surgery. As a result, the primary trocar is relocated to the left upper quadrant. Inspection confirms that small bowel is adherent to the anterior abdominal wall.

FIGURE 2 Adherent bowel, minor bleeding

B: After the small-bowel adhesions are dissected off the anterior abdominal wall via laparoscopy, a small hematoma is discovered, likely caused by the Veress needle. The patient is managed conservatively and recovers.

The value of open laparoscopy

In open laparoscopy, an abdominal incision is made into the peritoneal cavity so that the trocar can be placed under direct vision, after which the abdomen is insufflated. This approach can prevent bowel injury only when the adhesions and attachments are to the anterior abdominal wall and away from the entry site. When the attachment lies directly beneath the umbilicus, however, open laparoscopy is no guarantee against injury.

When bowel adhesions are severe, use alternative trocar sites such as the left upper quadrant (Palmer’s point) for the Veress needle and primary trocars.5,20,21

The likelihood of perforation can be reduced with preoperative bowel prep when there is a risk of bowel adhesions.

Identifying bowel injury

We recommend routine inspection of the structures beneath the primary trocar upon insertion of the laparoscope to look for injury to the bowel, mesentery, or vascular structures. If adhesions are found, evaluate the area carefully to rule out injury to the bowel or omentum. It may be necessary to change the position of the laparoscope to assess the patient.

Trauma to the intestinal tract can be mechanical or electrical in nature, and each type of trauma creates a distinctive, characteristic pattern. Thermal injury can be subtle and present as simple blanching or a distinct burn and charring. A small hole or obvious tear in the bowel wall can be the result of mechanical injury.22

Benign-appearing, superficial thermal bowel injuries may be managed conservatively.22 Minimal serosal burns (smaller than 5 mm in diameter) can be managed expectantly. Immediate surgical intervention is needed if the area of blanching on the intestinal serosa exceeds 5 mm in diameter or if the burn appears to involve more than the serosa.23

Small-bowel injuries that escape notice intraoperatively generally become apparent 2 to 4 days later, when the patient develops fever, nausea, lower abdominal pain, and anorexia. On postoperative day 5 or 6, the white blood cell (WBC) count rises and earlier symptoms may become worse. Radiography may reveal multiple air and fluid levels—another sign of bowel injury. Be aware that if the patient has clinical symptoms of gastrointestinal injury, even if the WBC count is normal, exploratory laparoscopy or laparotomy is necessary for accurate diagnosis.

Intraoperatively discovered injury

Careful inspection may reveal no leakage or bleeding in the affected area. Small punctures or superficial lacerations seal readily and may not require further treatment (FIGURE 2B), but larger perforations require repair. Straightforward repair is not always possible when the injury is extensive and considerable time has elapsed before it is discovered.

Inspect the intestine thoroughly at the conclusion of a procedure; obvious leakage requires intervention. Repair the small intestine in one or two layers, using the initial row of interrupted sutures to approximate the mucosa and muscularis.24 To lessen the risk of stenosis, close all lacerations transversely when they are smaller than one half the diameter of the bowel. If the laceration exceeds that size, segmental resection and anastomosis are necessary. Resection is prudent if the mesenteric blood supply is compromised.25

When performing one-layer repair of the small bowel, delayed absorbable suture (eg, Vicryl or PDS) or nonabsorbable suture (eg, silk) is recommended.26

At the conclusion of a repair, copiously irrigate the entire abdomen. Place a nasogastric tube only if ileus is anticipated; the tube can be removed when drainage diminishes and active bowel sounds and flatus appear. Do not give anything by mouth until the patient has return of bowel function and active peristalsis. Prescribe prophylactic antibiotics.

Note that peritonitis sometimes develops after repair of the bowel.25 This can be managed with prolonged bowel rest and peripheral or total parenteral nutrition.

Conservative management may be possible

Patients whose symptoms of bowel laceration become apparent after discharge can sometimes be managed conservatively. More than 50% of patients treated conservatively require no surgery.23 Inpatient management consists of monitoring the WBC count, providing hydration and IV antibiotics, and examining the patient every 6 hours, giving nothing by mouth.

When injury is discovered later

If conservative management with observation and bowel rest fails, or the patient complains of severe abdominal pain, vomiting, nausea, obstipation, or signs and symptoms of peritonitis, such as the patient in Case 3, immediate surgical intervention is necessary. When an injury is not detected until some time after initial surgery, resection of all necrotic tissue is mandatory. In most cases, the perforation is managed by segmental resection and reanastomosis. Evaluate the entire small and large bowel to rule out any other injury, and irrigate generously. Bowel rest, parenteral nutrition, and IV antibiotics also are indicated.

Of 36,928 procedures reported by members of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists, there were two deaths—both caused by unrecognized bowel injury.15

CASE 4: Large-bowel injury precipitates lengthy recovery

A surgeon performs a left laparoscopic salpingo-oophorectomy to remove an 8-cm ovarian endometrioma that is adherent to the rectosigmoid colon of a 40-year-old diabetic woman. Sharp and electrosurgical scissors are used to separate the adnexa from the rectosigmoid colon. No injury is observed, and she is discharged the same day. Four days later, she returns with severe abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and fatigue. Lab tests reveal a WBC count of 17,000; a CT scan shows pockets of air beneath the diaphragm, as well as fluid collection suggestive of a pelvic abscess.

Immediate laparotomy is performed, during which the surgeon discovers contamination of the abdominal viscera by bowel contents, as well as a 0.5-cm perforation of the rectosigmoid colon. The perforation is repaired in two layers after its edges are trimmed, and a diverting colostomy is performed. The patient is admitted to the ICU and requires antibiotic treatment, total parenteral nutrition, and bowel rest due to severe peritonitis. She gradually recovers and is discharged 3 weeks later. The diverting colostomy is reversed 3 months later.

Even small perforations in the large bowel can cause infection and abscess due to the high bacterial content of the colon. The most common cause of injury to the rectosigmoid colon is pelvic adhesiolysis during cul-de-sac dissection, treatment of pelvic endometriosis, and resection of adherent pelvic masses.

Sharp dissection with scissors or high-powered lasers is relatively safe near the bowel. When dissecting the cul-de-sac, identify the vagina and rectum by placing a probe or finger in each area. Begin dissection from the unaffected pararectal space, and proceed toward the obliterated cul-de-sac.27,28

Bowel prep is indicated before extensive pelvic surgery and when the history suggests endometriosis or significant pelvic adhesions. Some general surgeons base their decision to perform colostomy (or not) on whether the bowel was prepped preoperatively.29

If the large bowel is perforated by the Veress needle, the saline aspiration test will yield brownish fluid. When significant pelvic adhesiolysis or pelvic or endometriotic tumor resection is performed, inject air into the rectum afterward via a sigmoidoscope or bulb syringe and assess the submerged rectum and rectosigmoid colon for bubbling. The rectal wall may be weakened during these types of procedures, so instruct the patient to use oral stool softeners and avoid enemas.30

Delay in detection can have serious ramifications

When a large-bowel injury goes undetected at the time of operation, the patient generally presents on the third or fourth postoperative day with mild fever, occasionally sudden sharp epigastric pain, lower abdominal pain, slight nausea, and anorexia. By the fifth or sixth day, these symptoms have become more severe and are accompanied by peritonitis and an elevated WBC count.

Whenever a patient complains of abdominal pain and a deteriorating condition, assume that bowel injury is the cause until it is proved otherwise.

Intraoperative management