User login

The number of ob.gyns. nearing retirement age is outpacing the number of younger physicians in the specialty, making it likely that the United States will not have enough women’s health physicians to meet the demand.

New research by the medical social network Doximity finds that 37% of ob.gyns. in the United States are 55 or older, while just 14% are 40 or younger. Furthering the potential for shortage, Doximity cited research from the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists that most ob.gyns. begin to retire at age 59, with the median retirement age being 64. Doximity’s own research found the average age of ob.gyns. across the nation is 51.

The report notes that after emergency physicians, ob.gyns. “have the highest burn-out rates of all medical specialties. Moreover, due to the nature of obstetrics, and child birth in particular, this job is especially demanding, often requiring ob.gyns. to work at unpredictable hours. This lifestyle can lead ob.gyns. to retire at younger ages than physicians in other specialties.”

At the same time, the ob.gyn. workforce remains stagnant. “According to ACOG, there are now 1,287 first year ob.gyn. residency positions, a number that has increased only minimally in the past few decades, while the number of adult. U.S. women has increased much more significantly, stretching the ratio of ob.gyns. to patients,” the Doximity report said.

William F. Rayburn, MD, distinguished professor and emeritus chair of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, agreed with the findings.

Specifically, more general ob.gyns. are gravitating to metropolitan areas and are employed by health systems or large group practices, he noted.

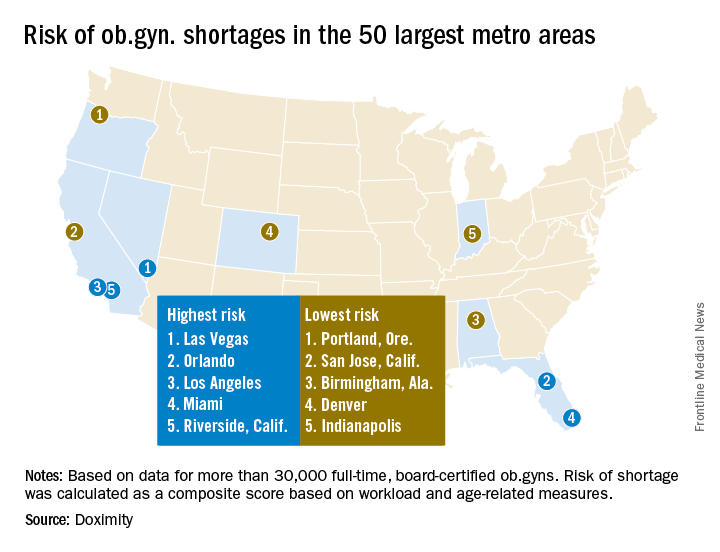

Doximity identified the top 10 metropolitan areas that are at highest risk for an ob.gyn. shortage: Las Vegas; Orlando; Los Angeles; Miami; Riverside, Calif.; Detroit; Memphis; Salt Lake City; St. Louis; and Buffalo, N.Y.

In contrast, the metropolitan areas with the lowest risk of shortages are Portland, Ore.; San Jose, Calif.; Birmingham, Ala.; Denver; Indianapolis; Cleveland; San Francisco; Richmond, Va.; Louisville, Ky.; and Columbus, Ohio.

This is likely to translate to access to care problems in smaller communities, Dr. Rayburn said. “What we are going to be seeing is more graduates from nonphysician clinician programs who are going to be hired, such as nurse practitioners, to fill the gaps.”

The Doximity analysis is based on data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, board certification, and self-reported data from more than 30,000 ob.gyns.

gtwachtman@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @ObGynNews

The number of ob.gyns. nearing retirement age is outpacing the number of younger physicians in the specialty, making it likely that the United States will not have enough women’s health physicians to meet the demand.

New research by the medical social network Doximity finds that 37% of ob.gyns. in the United States are 55 or older, while just 14% are 40 or younger. Furthering the potential for shortage, Doximity cited research from the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists that most ob.gyns. begin to retire at age 59, with the median retirement age being 64. Doximity’s own research found the average age of ob.gyns. across the nation is 51.

The report notes that after emergency physicians, ob.gyns. “have the highest burn-out rates of all medical specialties. Moreover, due to the nature of obstetrics, and child birth in particular, this job is especially demanding, often requiring ob.gyns. to work at unpredictable hours. This lifestyle can lead ob.gyns. to retire at younger ages than physicians in other specialties.”

At the same time, the ob.gyn. workforce remains stagnant. “According to ACOG, there are now 1,287 first year ob.gyn. residency positions, a number that has increased only minimally in the past few decades, while the number of adult. U.S. women has increased much more significantly, stretching the ratio of ob.gyns. to patients,” the Doximity report said.

William F. Rayburn, MD, distinguished professor and emeritus chair of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, agreed with the findings.

Specifically, more general ob.gyns. are gravitating to metropolitan areas and are employed by health systems or large group practices, he noted.

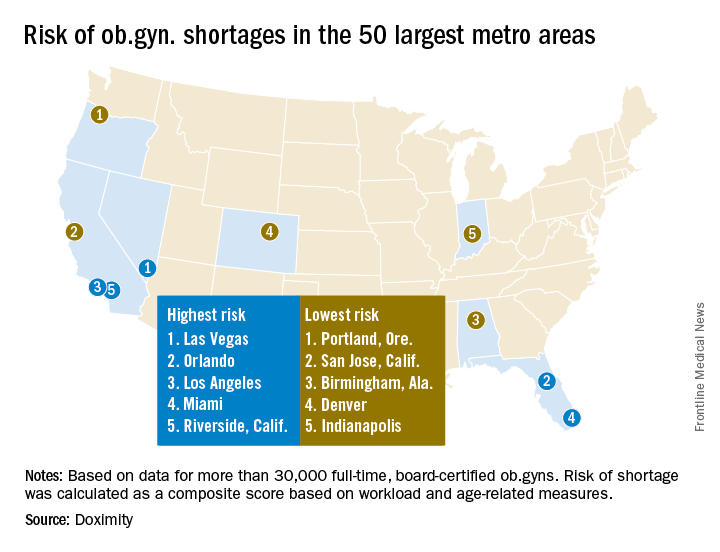

Doximity identified the top 10 metropolitan areas that are at highest risk for an ob.gyn. shortage: Las Vegas; Orlando; Los Angeles; Miami; Riverside, Calif.; Detroit; Memphis; Salt Lake City; St. Louis; and Buffalo, N.Y.

In contrast, the metropolitan areas with the lowest risk of shortages are Portland, Ore.; San Jose, Calif.; Birmingham, Ala.; Denver; Indianapolis; Cleveland; San Francisco; Richmond, Va.; Louisville, Ky.; and Columbus, Ohio.

This is likely to translate to access to care problems in smaller communities, Dr. Rayburn said. “What we are going to be seeing is more graduates from nonphysician clinician programs who are going to be hired, such as nurse practitioners, to fill the gaps.”

The Doximity analysis is based on data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, board certification, and self-reported data from more than 30,000 ob.gyns.

gtwachtman@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @ObGynNews

The number of ob.gyns. nearing retirement age is outpacing the number of younger physicians in the specialty, making it likely that the United States will not have enough women’s health physicians to meet the demand.

New research by the medical social network Doximity finds that 37% of ob.gyns. in the United States are 55 or older, while just 14% are 40 or younger. Furthering the potential for shortage, Doximity cited research from the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists that most ob.gyns. begin to retire at age 59, with the median retirement age being 64. Doximity’s own research found the average age of ob.gyns. across the nation is 51.

The report notes that after emergency physicians, ob.gyns. “have the highest burn-out rates of all medical specialties. Moreover, due to the nature of obstetrics, and child birth in particular, this job is especially demanding, often requiring ob.gyns. to work at unpredictable hours. This lifestyle can lead ob.gyns. to retire at younger ages than physicians in other specialties.”

At the same time, the ob.gyn. workforce remains stagnant. “According to ACOG, there are now 1,287 first year ob.gyn. residency positions, a number that has increased only minimally in the past few decades, while the number of adult. U.S. women has increased much more significantly, stretching the ratio of ob.gyns. to patients,” the Doximity report said.

William F. Rayburn, MD, distinguished professor and emeritus chair of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, agreed with the findings.

Specifically, more general ob.gyns. are gravitating to metropolitan areas and are employed by health systems or large group practices, he noted.

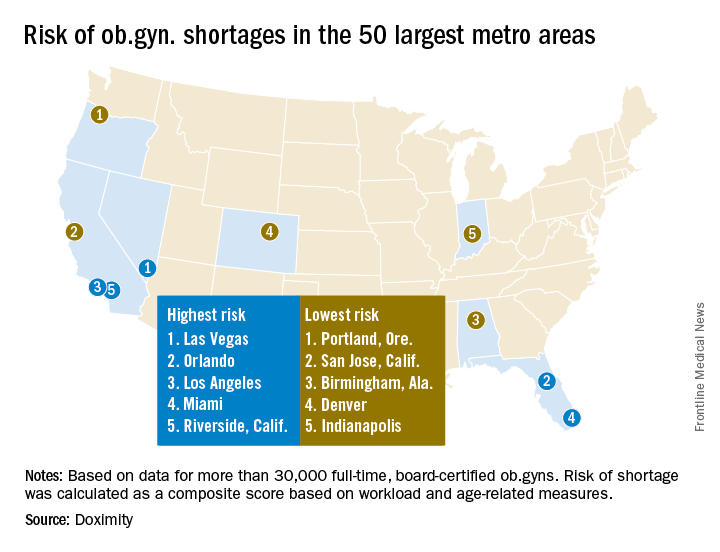

Doximity identified the top 10 metropolitan areas that are at highest risk for an ob.gyn. shortage: Las Vegas; Orlando; Los Angeles; Miami; Riverside, Calif.; Detroit; Memphis; Salt Lake City; St. Louis; and Buffalo, N.Y.

In contrast, the metropolitan areas with the lowest risk of shortages are Portland, Ore.; San Jose, Calif.; Birmingham, Ala.; Denver; Indianapolis; Cleveland; San Francisco; Richmond, Va.; Louisville, Ky.; and Columbus, Ohio.

This is likely to translate to access to care problems in smaller communities, Dr. Rayburn said. “What we are going to be seeing is more graduates from nonphysician clinician programs who are going to be hired, such as nurse practitioners, to fill the gaps.”

The Doximity analysis is based on data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, board certification, and self-reported data from more than 30,000 ob.gyns.

gtwachtman@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @ObGynNews