User login

The U.S. immunization program has been one of the country’s most successful initiatives and best investments. Prior to 2005, vaccines were targeted for administration to infants and young children. Adolescence was a period for catch-up immunizations. All that changed in 2005 when the first meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MCV) was recommended for administration to preteens at 11-12 years and college freshmen residing in dormitories by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Shortly thereafter in 2006, a new tetanus toxoid, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap) was recommended, and in March 2007 the quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine (HPV4: types 6, 11, 16, and 18) was recommended for use in girls, starting at age 11-12 years, and young women up to 26 years of age. In 2009, a bivalent HPV vaccine (HPV2: types 16 and 18) was licensed, and in 2010, ACIP recommendations indicated that either HPV4 or HPV2 vaccine could be administered to girls and young women. In addition, the use of HPV4 vaccine in males was permitted. In 2011, ACIP recommended routine administration of HPV4 to boys and young adult males up to 21 years of age. Adolescents were the target population for these vaccines, and administration was recommended at the 11- to 12-year wellness visit. The primary role of the adolescent encounter was no longer to provide catch-up immunizations. A definitive adolescent immunization schedule had been established.

Why introduce the HPV vaccine so early?

HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection in both men and women. Recent data suggest that approximately 79 million individuals are infected (Sex. Transm. Dis. 2013;40:187-93). Annually, about 14 million, mostly young adults are infected. Most sexually active individuals will acquire HPV. It is most common in teens and young adults, and intercourse is not required for transmission. It can be transmitted with any type of intimate sexual contact, and it has been isolated from virgins. The majority of these infections are asymptomatic and self- limited. However, persistent infection is associated with cervical and other types of anogenital cancer, and genital warts in both men and women. Complications of these infections may take years to manifest.

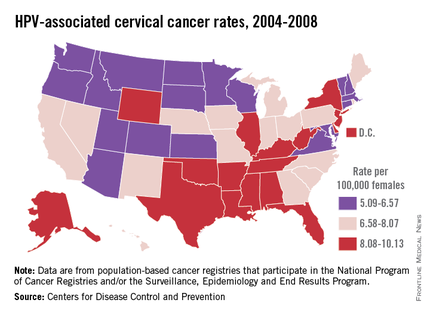

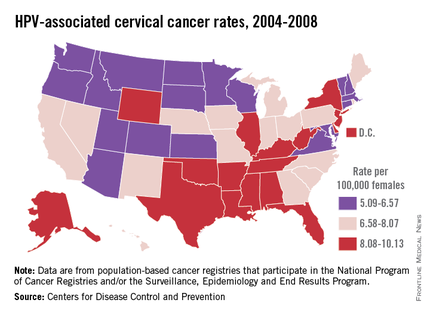

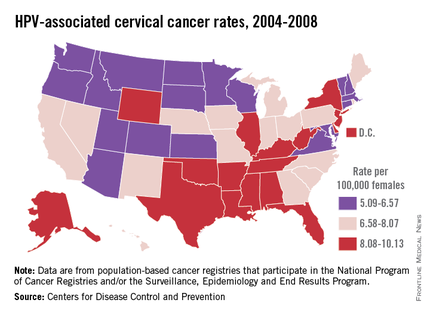

HPV is categorized by its epidemiologic association with cervical cancer. High-risk types cause cervical cancer, and HPV types 16 and 18 account for the majority of cervical cancers (66%) These two types are also associated with vaginal (55%), anal (79%), and oropharyngeal (62%) cancer (MMWR 2014 Jan. 31;63;69-72). It is estimated that each year there are 26,000 HPV-related cancers including 8,800 cases in men and 17,000 in women, 4,000 of whom will die of cervical cancer, according to the CDC. Low-risk types including HPV types 6 and 11 cause benign/low-grade cervical cell changes, recurrent papillomatosis, and 90% of the cases of genital warts.

Once a person is infected, HPV usually clears. If not, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) may occur. The infection may still resolve spontaneously. If it persists, the degree of dysplasia can progress. Several years may pass before progression to invasive cancer. HPV vaccines are prophylactic like other vaccines. They cannot prevent disease progression and need to be administered before exposure to the viruses.

Compared with the introduction of other vaccines, such as Haemophilus influenzae type b and Prevnar7, some pediatric care providers may feel we may not have the benefit of realizing our efforts as immediately as in the past. However, encouraging vaccine effectiveness data in U.S. teens has been published. In one study, the investigators compared HPV prevalence data from the pre- and postvaccine era collected during the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Among females aged 14-19 years, HPV prevalence (HPV-6, -11, -16, or -18 ) decreased from 11.5% in 2003-2006 to 5.1% in 2007-2010. That is a 56% reduction in vaccine type HPV prevalence. This decrease in prevalence occurred within 4 years of vaccine introduction and low vaccine uptake. (J. Infect. Dis. 2013;208:385-93). Studies conducted in Denmark, Australia, Germany, and New Zealand also have shown significant declines in HPV4 vaccine type infection prevalence.

Vaccination coverage

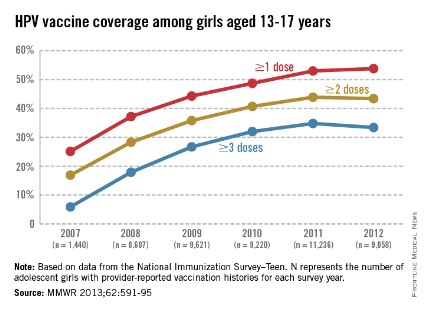

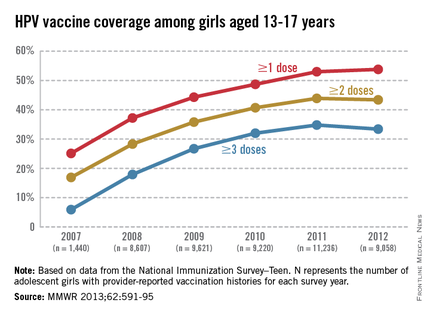

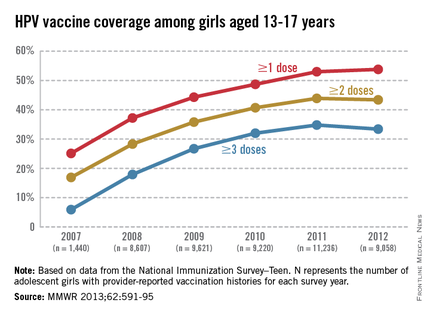

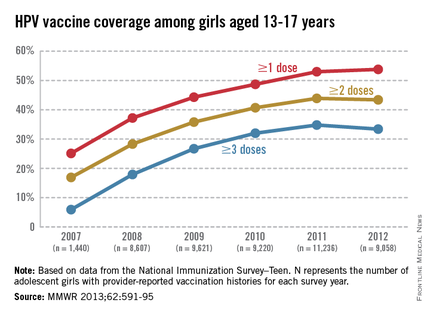

The CDC tracks vaccination coverage annually in the National Immunization Survey–Teen (NIS-Teen), with data obtained from the 50 states, the District of Columbia, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and six major urban areas (MMWR 2013;62:685-93). Vaccination coverage differed significantly although each vaccine is recommended to be routinely administered at the 11- to 12-year visit. Although an increase from 25% to 53% had been noted between 2007 and 2011, in 2012, coverage for receiving at least one dose of HPV among females was almost 54%, essentially unchanged since 2011. The number who had received the recommended three doses was also essentially unchanged from 2011 to 2012 (34.8% in 2011 and 33.4% in 2012). Receipt of a single dose of HPV in boys was 8.3% in 2011 and 20.8% in 2012, the first year after the vaccine was recommended. Completion of the series in boys was 6.3%, an increase from 1.3% in 2011.

In contrast, the 2012 coverage for Tdap increased to 85% and MCV4, to 74%. It has been suggested that the higher coverage of Tdap and MCV may be due to the 40 and 13 states, respectively, that require them for middle school entry.

The disparity in coverage between Tdap and other vaccines suggests there are numerous missed opportunities to vaccinate adolescents. Data revealed that missed opportunities for girls increased from 20.8% in 2007 to 84% in 2012. If all missed opportunities had been eliminated, HPV coverage for at least one dose could have reached 92.6%.Almost 25% of parents indicated that they had no plan to immunize their daughter. The top reasons parents stated for not immunizing their daughters included: not needed or necessary, 19.1%; not recommended by provider, 14.2%; safety concerns, 13.3%; lack of knowledge, 12.6%; and not sexually active, 10.1%. (MMWR 2013;62:591-5).

Vaccine safety also was addressed. All reported adverse events were consistent with prelicensure clinical trial data. Ninety two percent of all adverse events were nonserious and included syncope, dizziness, nausea, and fever. Reports peaked in 2008 and have declined each year thereafter.

Challenges for HPV prevention

Improving immunization coverage is critical. There are numerous strategies to increase coverage including reminder recall systems, standing orders, and educating parents, patients, health care providers, and office staff who interact with parents. Education should reemphasize why immunization is initiated at 11-12 years and that completion of the series is recommended by 13 years. School requirements have always led to an increase in vaccination coverage. Only the District of Columbia has one for HPV. In this case, eliminating missed opportunities is crucial. It is estimated that for every year coverage is delayed, an additional 4,400 women will develop cervical cancer. The reality is that the burden of HPV-related cancers will persist if coverage is not increased.

As Louis Pasteur once said, "When meditating over a disease, I never think of finding a remedy for it, but, instead a means of preventing it."

For additional resources to assist with discussions about HPV, click here.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. E-mail her at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com. Scan this QR code or visit pediatricnews.com.

The U.S. immunization program has been one of the country’s most successful initiatives and best investments. Prior to 2005, vaccines were targeted for administration to infants and young children. Adolescence was a period for catch-up immunizations. All that changed in 2005 when the first meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MCV) was recommended for administration to preteens at 11-12 years and college freshmen residing in dormitories by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Shortly thereafter in 2006, a new tetanus toxoid, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap) was recommended, and in March 2007 the quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine (HPV4: types 6, 11, 16, and 18) was recommended for use in girls, starting at age 11-12 years, and young women up to 26 years of age. In 2009, a bivalent HPV vaccine (HPV2: types 16 and 18) was licensed, and in 2010, ACIP recommendations indicated that either HPV4 or HPV2 vaccine could be administered to girls and young women. In addition, the use of HPV4 vaccine in males was permitted. In 2011, ACIP recommended routine administration of HPV4 to boys and young adult males up to 21 years of age. Adolescents were the target population for these vaccines, and administration was recommended at the 11- to 12-year wellness visit. The primary role of the adolescent encounter was no longer to provide catch-up immunizations. A definitive adolescent immunization schedule had been established.

Why introduce the HPV vaccine so early?

HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection in both men and women. Recent data suggest that approximately 79 million individuals are infected (Sex. Transm. Dis. 2013;40:187-93). Annually, about 14 million, mostly young adults are infected. Most sexually active individuals will acquire HPV. It is most common in teens and young adults, and intercourse is not required for transmission. It can be transmitted with any type of intimate sexual contact, and it has been isolated from virgins. The majority of these infections are asymptomatic and self- limited. However, persistent infection is associated with cervical and other types of anogenital cancer, and genital warts in both men and women. Complications of these infections may take years to manifest.

HPV is categorized by its epidemiologic association with cervical cancer. High-risk types cause cervical cancer, and HPV types 16 and 18 account for the majority of cervical cancers (66%) These two types are also associated with vaginal (55%), anal (79%), and oropharyngeal (62%) cancer (MMWR 2014 Jan. 31;63;69-72). It is estimated that each year there are 26,000 HPV-related cancers including 8,800 cases in men and 17,000 in women, 4,000 of whom will die of cervical cancer, according to the CDC. Low-risk types including HPV types 6 and 11 cause benign/low-grade cervical cell changes, recurrent papillomatosis, and 90% of the cases of genital warts.

Once a person is infected, HPV usually clears. If not, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) may occur. The infection may still resolve spontaneously. If it persists, the degree of dysplasia can progress. Several years may pass before progression to invasive cancer. HPV vaccines are prophylactic like other vaccines. They cannot prevent disease progression and need to be administered before exposure to the viruses.

Compared with the introduction of other vaccines, such as Haemophilus influenzae type b and Prevnar7, some pediatric care providers may feel we may not have the benefit of realizing our efforts as immediately as in the past. However, encouraging vaccine effectiveness data in U.S. teens has been published. In one study, the investigators compared HPV prevalence data from the pre- and postvaccine era collected during the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Among females aged 14-19 years, HPV prevalence (HPV-6, -11, -16, or -18 ) decreased from 11.5% in 2003-2006 to 5.1% in 2007-2010. That is a 56% reduction in vaccine type HPV prevalence. This decrease in prevalence occurred within 4 years of vaccine introduction and low vaccine uptake. (J. Infect. Dis. 2013;208:385-93). Studies conducted in Denmark, Australia, Germany, and New Zealand also have shown significant declines in HPV4 vaccine type infection prevalence.

Vaccination coverage

The CDC tracks vaccination coverage annually in the National Immunization Survey–Teen (NIS-Teen), with data obtained from the 50 states, the District of Columbia, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and six major urban areas (MMWR 2013;62:685-93). Vaccination coverage differed significantly although each vaccine is recommended to be routinely administered at the 11- to 12-year visit. Although an increase from 25% to 53% had been noted between 2007 and 2011, in 2012, coverage for receiving at least one dose of HPV among females was almost 54%, essentially unchanged since 2011. The number who had received the recommended three doses was also essentially unchanged from 2011 to 2012 (34.8% in 2011 and 33.4% in 2012). Receipt of a single dose of HPV in boys was 8.3% in 2011 and 20.8% in 2012, the first year after the vaccine was recommended. Completion of the series in boys was 6.3%, an increase from 1.3% in 2011.

In contrast, the 2012 coverage for Tdap increased to 85% and MCV4, to 74%. It has been suggested that the higher coverage of Tdap and MCV may be due to the 40 and 13 states, respectively, that require them for middle school entry.

The disparity in coverage between Tdap and other vaccines suggests there are numerous missed opportunities to vaccinate adolescents. Data revealed that missed opportunities for girls increased from 20.8% in 2007 to 84% in 2012. If all missed opportunities had been eliminated, HPV coverage for at least one dose could have reached 92.6%.Almost 25% of parents indicated that they had no plan to immunize their daughter. The top reasons parents stated for not immunizing their daughters included: not needed or necessary, 19.1%; not recommended by provider, 14.2%; safety concerns, 13.3%; lack of knowledge, 12.6%; and not sexually active, 10.1%. (MMWR 2013;62:591-5).

Vaccine safety also was addressed. All reported adverse events were consistent with prelicensure clinical trial data. Ninety two percent of all adverse events were nonserious and included syncope, dizziness, nausea, and fever. Reports peaked in 2008 and have declined each year thereafter.

Challenges for HPV prevention

Improving immunization coverage is critical. There are numerous strategies to increase coverage including reminder recall systems, standing orders, and educating parents, patients, health care providers, and office staff who interact with parents. Education should reemphasize why immunization is initiated at 11-12 years and that completion of the series is recommended by 13 years. School requirements have always led to an increase in vaccination coverage. Only the District of Columbia has one for HPV. In this case, eliminating missed opportunities is crucial. It is estimated that for every year coverage is delayed, an additional 4,400 women will develop cervical cancer. The reality is that the burden of HPV-related cancers will persist if coverage is not increased.

As Louis Pasteur once said, "When meditating over a disease, I never think of finding a remedy for it, but, instead a means of preventing it."

For additional resources to assist with discussions about HPV, click here.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. E-mail her at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com. Scan this QR code or visit pediatricnews.com.

The U.S. immunization program has been one of the country’s most successful initiatives and best investments. Prior to 2005, vaccines were targeted for administration to infants and young children. Adolescence was a period for catch-up immunizations. All that changed in 2005 when the first meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MCV) was recommended for administration to preteens at 11-12 years and college freshmen residing in dormitories by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Shortly thereafter in 2006, a new tetanus toxoid, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap) was recommended, and in March 2007 the quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine (HPV4: types 6, 11, 16, and 18) was recommended for use in girls, starting at age 11-12 years, and young women up to 26 years of age. In 2009, a bivalent HPV vaccine (HPV2: types 16 and 18) was licensed, and in 2010, ACIP recommendations indicated that either HPV4 or HPV2 vaccine could be administered to girls and young women. In addition, the use of HPV4 vaccine in males was permitted. In 2011, ACIP recommended routine administration of HPV4 to boys and young adult males up to 21 years of age. Adolescents were the target population for these vaccines, and administration was recommended at the 11- to 12-year wellness visit. The primary role of the adolescent encounter was no longer to provide catch-up immunizations. A definitive adolescent immunization schedule had been established.

Why introduce the HPV vaccine so early?

HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection in both men and women. Recent data suggest that approximately 79 million individuals are infected (Sex. Transm. Dis. 2013;40:187-93). Annually, about 14 million, mostly young adults are infected. Most sexually active individuals will acquire HPV. It is most common in teens and young adults, and intercourse is not required for transmission. It can be transmitted with any type of intimate sexual contact, and it has been isolated from virgins. The majority of these infections are asymptomatic and self- limited. However, persistent infection is associated with cervical and other types of anogenital cancer, and genital warts in both men and women. Complications of these infections may take years to manifest.

HPV is categorized by its epidemiologic association with cervical cancer. High-risk types cause cervical cancer, and HPV types 16 and 18 account for the majority of cervical cancers (66%) These two types are also associated with vaginal (55%), anal (79%), and oropharyngeal (62%) cancer (MMWR 2014 Jan. 31;63;69-72). It is estimated that each year there are 26,000 HPV-related cancers including 8,800 cases in men and 17,000 in women, 4,000 of whom will die of cervical cancer, according to the CDC. Low-risk types including HPV types 6 and 11 cause benign/low-grade cervical cell changes, recurrent papillomatosis, and 90% of the cases of genital warts.

Once a person is infected, HPV usually clears. If not, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) may occur. The infection may still resolve spontaneously. If it persists, the degree of dysplasia can progress. Several years may pass before progression to invasive cancer. HPV vaccines are prophylactic like other vaccines. They cannot prevent disease progression and need to be administered before exposure to the viruses.

Compared with the introduction of other vaccines, such as Haemophilus influenzae type b and Prevnar7, some pediatric care providers may feel we may not have the benefit of realizing our efforts as immediately as in the past. However, encouraging vaccine effectiveness data in U.S. teens has been published. In one study, the investigators compared HPV prevalence data from the pre- and postvaccine era collected during the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Among females aged 14-19 years, HPV prevalence (HPV-6, -11, -16, or -18 ) decreased from 11.5% in 2003-2006 to 5.1% in 2007-2010. That is a 56% reduction in vaccine type HPV prevalence. This decrease in prevalence occurred within 4 years of vaccine introduction and low vaccine uptake. (J. Infect. Dis. 2013;208:385-93). Studies conducted in Denmark, Australia, Germany, and New Zealand also have shown significant declines in HPV4 vaccine type infection prevalence.

Vaccination coverage

The CDC tracks vaccination coverage annually in the National Immunization Survey–Teen (NIS-Teen), with data obtained from the 50 states, the District of Columbia, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and six major urban areas (MMWR 2013;62:685-93). Vaccination coverage differed significantly although each vaccine is recommended to be routinely administered at the 11- to 12-year visit. Although an increase from 25% to 53% had been noted between 2007 and 2011, in 2012, coverage for receiving at least one dose of HPV among females was almost 54%, essentially unchanged since 2011. The number who had received the recommended three doses was also essentially unchanged from 2011 to 2012 (34.8% in 2011 and 33.4% in 2012). Receipt of a single dose of HPV in boys was 8.3% in 2011 and 20.8% in 2012, the first year after the vaccine was recommended. Completion of the series in boys was 6.3%, an increase from 1.3% in 2011.

In contrast, the 2012 coverage for Tdap increased to 85% and MCV4, to 74%. It has been suggested that the higher coverage of Tdap and MCV may be due to the 40 and 13 states, respectively, that require them for middle school entry.

The disparity in coverage between Tdap and other vaccines suggests there are numerous missed opportunities to vaccinate adolescents. Data revealed that missed opportunities for girls increased from 20.8% in 2007 to 84% in 2012. If all missed opportunities had been eliminated, HPV coverage for at least one dose could have reached 92.6%.Almost 25% of parents indicated that they had no plan to immunize their daughter. The top reasons parents stated for not immunizing their daughters included: not needed or necessary, 19.1%; not recommended by provider, 14.2%; safety concerns, 13.3%; lack of knowledge, 12.6%; and not sexually active, 10.1%. (MMWR 2013;62:591-5).

Vaccine safety also was addressed. All reported adverse events were consistent with prelicensure clinical trial data. Ninety two percent of all adverse events were nonserious and included syncope, dizziness, nausea, and fever. Reports peaked in 2008 and have declined each year thereafter.

Challenges for HPV prevention

Improving immunization coverage is critical. There are numerous strategies to increase coverage including reminder recall systems, standing orders, and educating parents, patients, health care providers, and office staff who interact with parents. Education should reemphasize why immunization is initiated at 11-12 years and that completion of the series is recommended by 13 years. School requirements have always led to an increase in vaccination coverage. Only the District of Columbia has one for HPV. In this case, eliminating missed opportunities is crucial. It is estimated that for every year coverage is delayed, an additional 4,400 women will develop cervical cancer. The reality is that the burden of HPV-related cancers will persist if coverage is not increased.

As Louis Pasteur once said, "When meditating over a disease, I never think of finding a remedy for it, but, instead a means of preventing it."

For additional resources to assist with discussions about HPV, click here.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. E-mail her at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com. Scan this QR code or visit pediatricnews.com.