User login

Achieving Psychological Safety in High Reliability Organizations

Worldwide, health care is becoming increasingly complex as a result of greater clinical workforce demands, expanded roles and responsibilities, health care system mergers, stakeholder calls for new capabilities, and digital transformation. 1,2These increasing demands has prompted many health care institutions to place greater focus on the psychological safety of their workforce, particularly in high reliability organizations (HROs). Building a robust foundation for high reliability in health care requires the presence of psychological safety—that is, staff members at all levels of the organization must feel comfortable speaking up when they have questions or concerns.3,4 Psychological safety can improve the safety and quality of patient care but has not reached its full potential in health care.5,6 However, there are strategies that promote the widespread implementation of psychological safety in health care organizations.3-6

PSYCHOLOGICAL SAFETY

The concept of psychological safety in organizational behavior originated in 1965 when Edgar Schein and Warren Bennis, leaders in organizational psychology and management, published their reflections on the importance of psychological safety in helping individuals feel secure in the work environment.5-7 Psychological safety in the workplace is foundational to staff members feeling comfortable asking questions or expressing concerns without fear of negative consequences.8,9 It supports both individual and team efforts to raise safety concerns and report near misses and adverse events so that similar events can be averted in the future.9 Patients aren’t the only ones who benefit; psychological safety has also been found to promote job satisfaction and employee well-being.10

THE VETERANS HEALTH ADMINISTRATION JOURNEY

Achieving psychological safety is by no means an easy or comfortable process. As with any organizational change, a multipronged approach offers the best chance of success.6,9 When the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) began its incremental, enterprise-wide journey to high reliability in 2019, 3 cohorts were identified. In February 2019, 18 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers (VAMCs) (cohort 1) began the process of becoming HROs. Cohort 2 followed in October 2020 and included 54 VAMC. Finally, in October 2021, 67 additional VAMCs (cohort 3) started the process.2 During cohort 2, the VA Providence Healthcare System (VAPHCS) decided to emphasize psychological safety at the start of the journey to becoming an HRO. This system is part of the VA New England Healthcare System (VISN 1), which includes VAMCs and clinics in Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont.11 Soon thereafter, the VA Bedford Healthcare System and the VA Connecticut Healthcare System adopted similar strategies. Since then, other VAMCs have also adopted this approach. These collective experiences identified 4 useful strategies for achieving psychological safety: leadership engagement, open communication, education and training, and accountability.

Leadership Engagement

Health care organization leaders play a critical role in making psychological safety happen—especially in complex and constantly changing environments, such as HROs.4 Leaders behaviors are consistently linked to the perception of psychological safety at the individual, team, and organizational levels.8 It is especially important to have leaders who recognize the views of individuals and team members and encourage staff participation in discussions to gain additional perspectives.7,8,12 Psychological safety can also be facilitated when leaders are visible, approachable, and communicative.4,7-9

Organizational practices, policies, and processes (eg, reporting adverse events without the fear of negative consequences) are also important ways that leaders can establish and sustain psychological safety. On a more granular level, leaders can enhance psychological safety by promoting and acknowledging individuals who speak up, regularly asking staff about safety concerns, highlighting “good catches” when harm is avoided, and using staff feedback to initiate improvements.4,7,13Finally, in the authors’ experience, psychological safety requires clear commitment from leaders at all levels of an organization. Communication should be bidirectional, and leaders should close the proverbial “loop” with feedback and timely follow-up. This encourages and reinforces staff engagement and speaking up behaviors.2,4,7,13

Open Communication

Promoting an environment of open communication, where all individuals and teams feel empowered to speak up with questions, concerns, and recommendations—regardless of position within the organization—is critical to psychological safety.4,6,9 Open communication is especially critical when processes and systems are constantly changing and advancing as a result of new information and technology.9 Promoting open, bidirectional communication during the delivery of patient care can be accomplished with huddles, tiered safety huddles, leader rounding for high reliability, and time-outs.2,4,6 These opportunities allow team members to discuss concerns, identify resources that support safe, high-quality care; reflect on successes and opportunities for improvement; and circle back on concerns.2,6 Open communication in psychologically safe environments empowers staff to raise patient care concerns and is instrumental for improving patient safety, increasing staff job satisfaction, and decreasing turnover.6,14

Education and Training

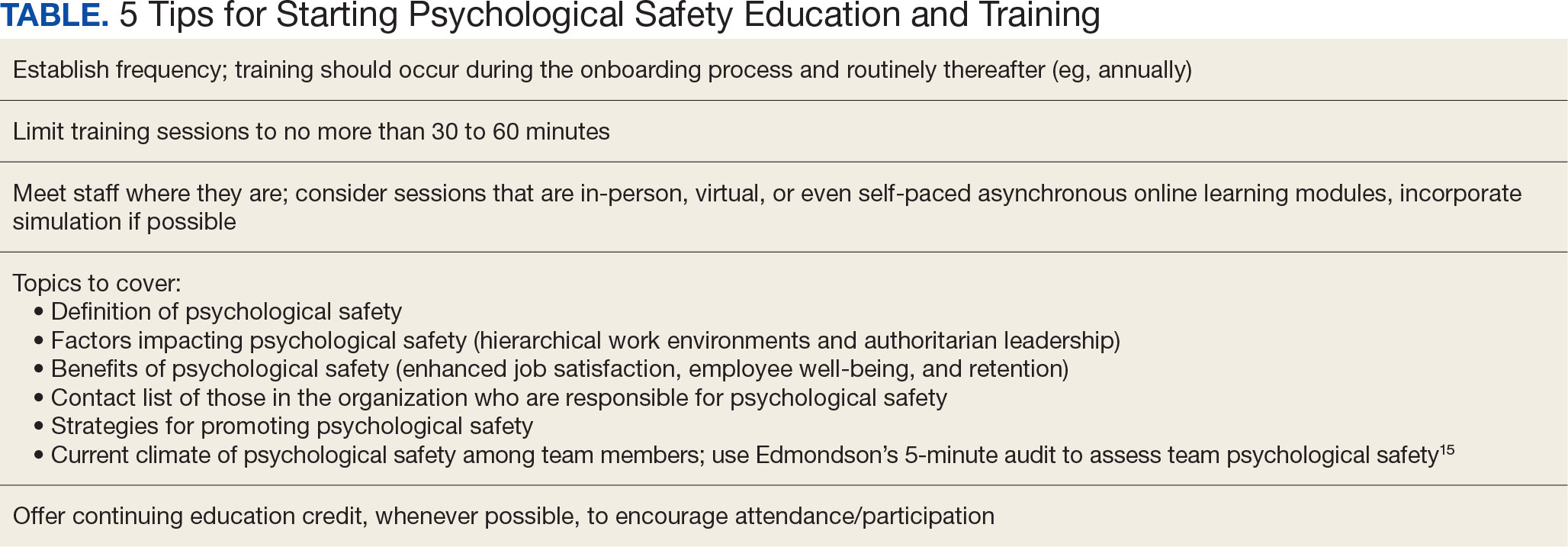

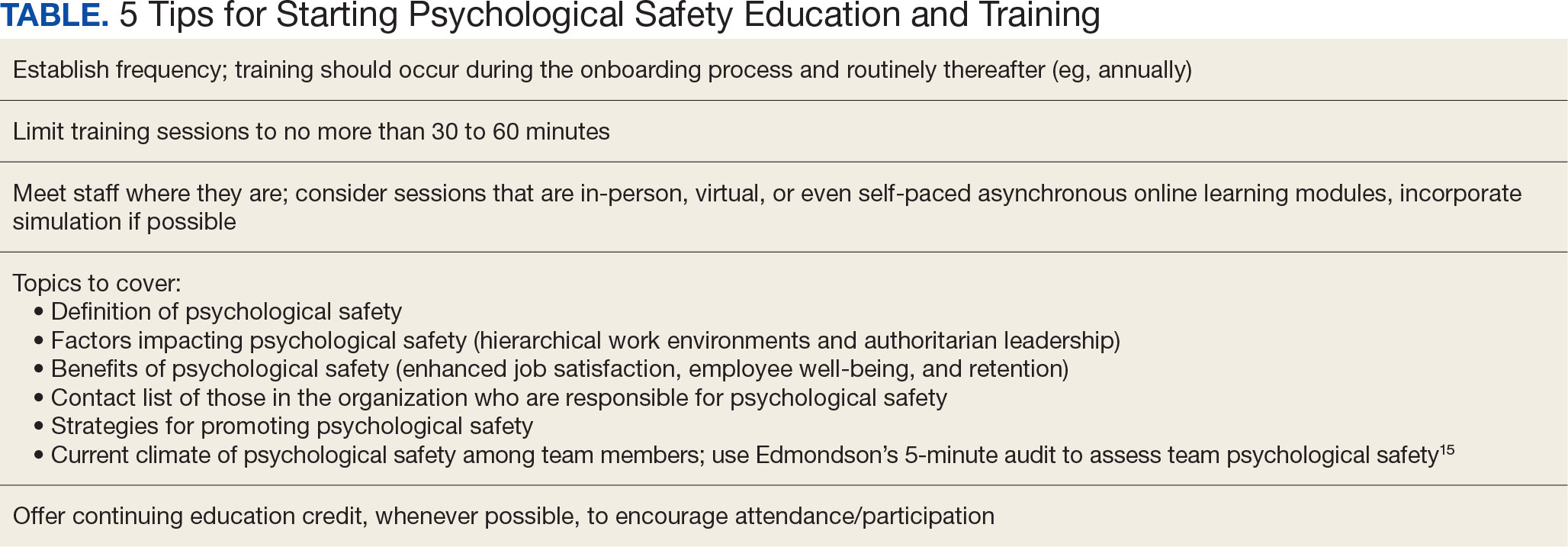

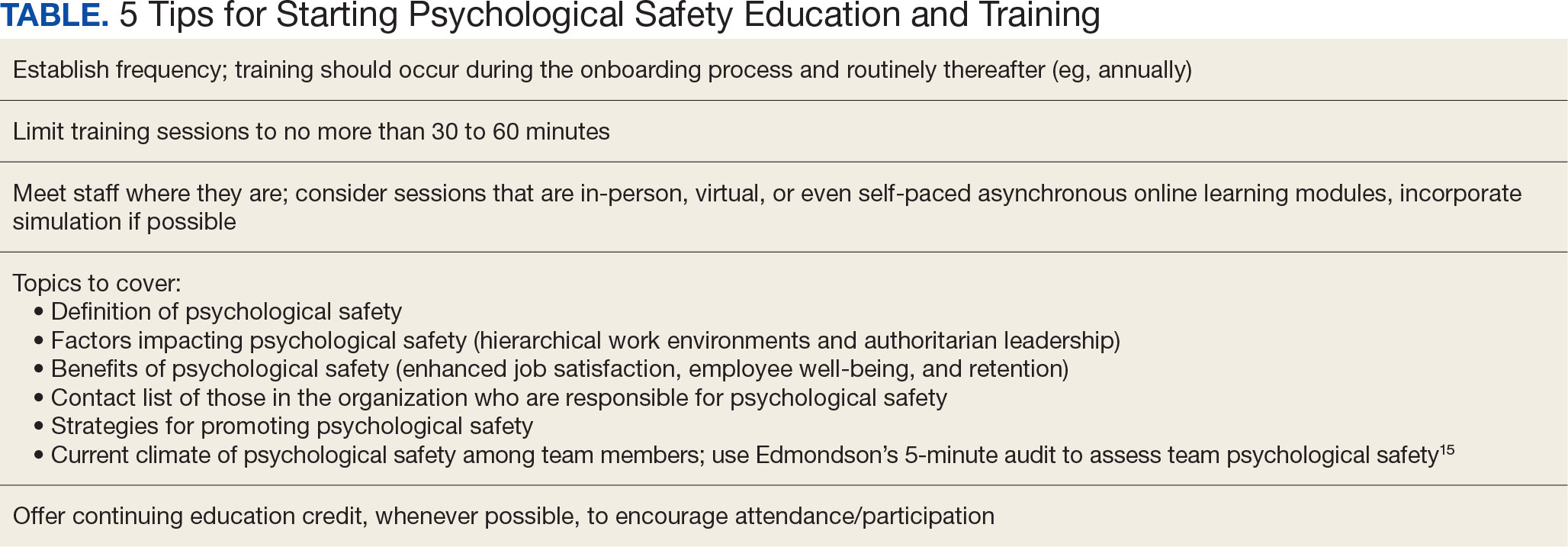

Education and training for all staff—from the frontline to the executive level—are essential to successfully implementing the principles and practices of psychological safety.5-7 VHA training covers many topics, including the origins, benefits, and implementation strategies of psychological safety (Table). Role-playing simulation is an effective teaching format, providing staff with opportunities to practice techniques for raising concerns or share feedback in a controlled environment.6 In addition, education should be ongoing; it helps leaders and staff members feel competent and confident when implementing psychological safety across the health care organization.6,10

Accountability

The final critical strategy for achieving psychological safety is accountability. It is the responsibility of all leadership—from senior leaders to clinical and nonclinical managers—to create a culture of shared accountability.5 But first, expectations must be set. Leadership must establish well-defined behavioral expectations that align with the organization’s values. Understanding behavioral expectations will help to ensure that employees know what achievement looks like, as well as how they are being held accountable for their individual actions.4,5,7 In practical terms, this means ensuring that staff members have the skills and resources to achieve goals and expectations, providing performance feedback in a timely manner, and including expectations in annual performance evaluations (as they are in the VHA).

Consistency is key. Accountability should be the expectation across all levels and services of the health care organization. No staff member should be exempt from promoting a psychologically safe work environment. Compliance with behavioral expectations should be monitored and if a person’s actions are not consistent with expectations, the situation will need to be addressed. Interventions will depend on the type, severity, and frequency of the problematic behaviors. Depending on an organization’s policies and practices, courses of action can range from feedback counseling to employment termination.5

A practical matter in ensuring accountability is implementing a psychologically safe process for reporting concerns. Staff members must feel comfortable reporting behavioral concerns without fear of retaliation, negative judgment, or consequences from peers and supervisors. One method for doing this is to create a confidential, centralized process for reporting concerns.5

First-Hand Results

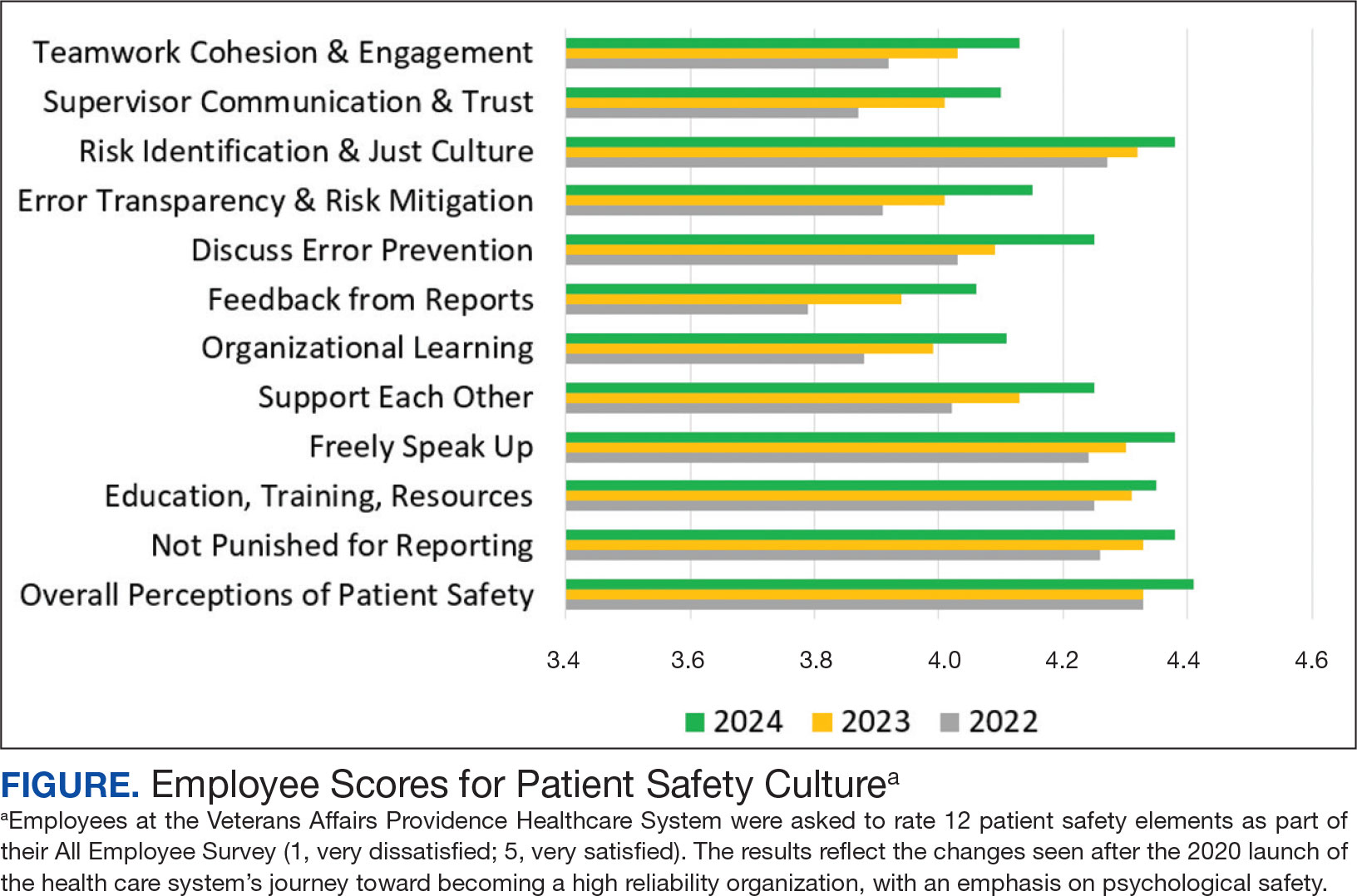

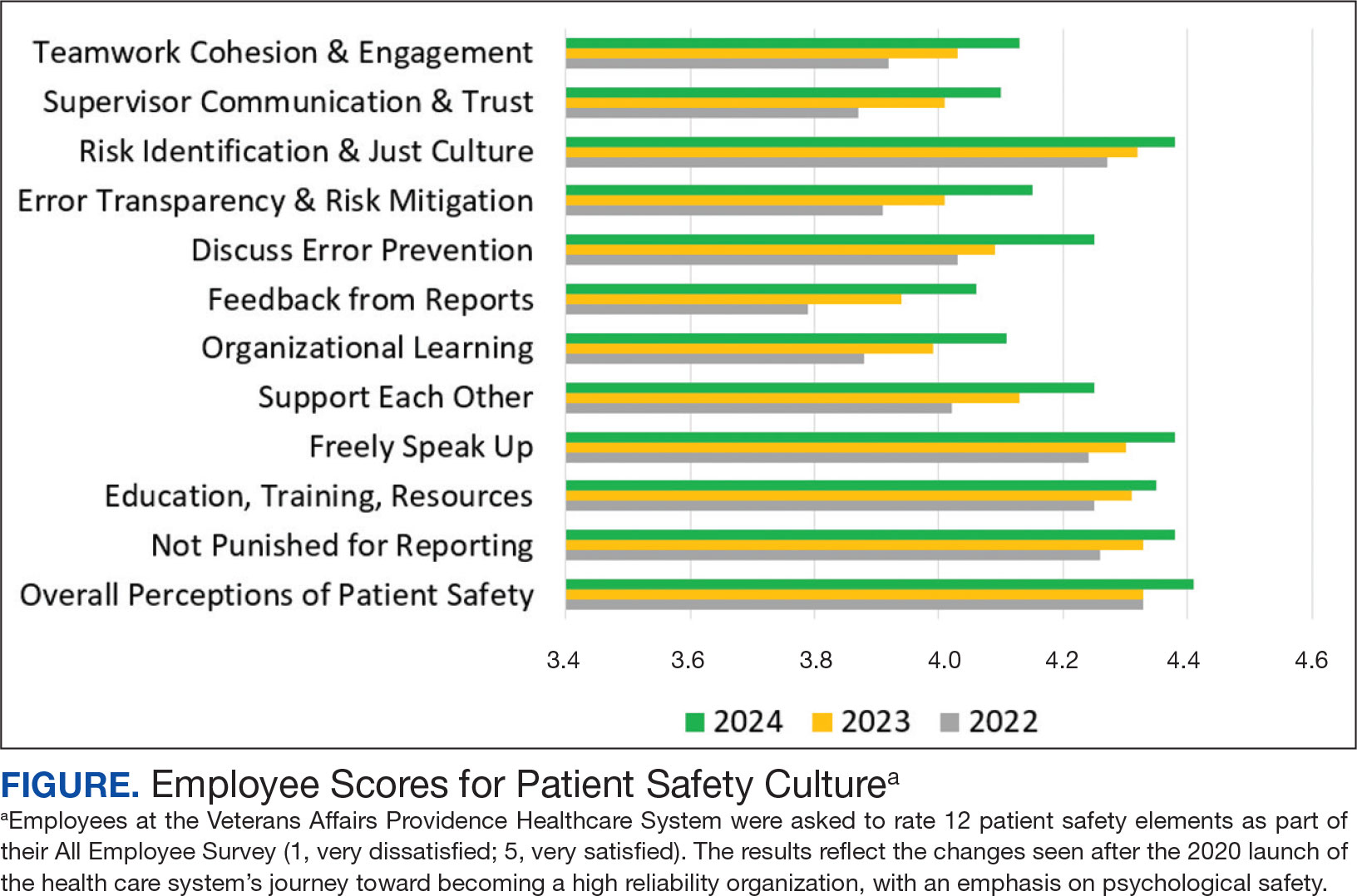

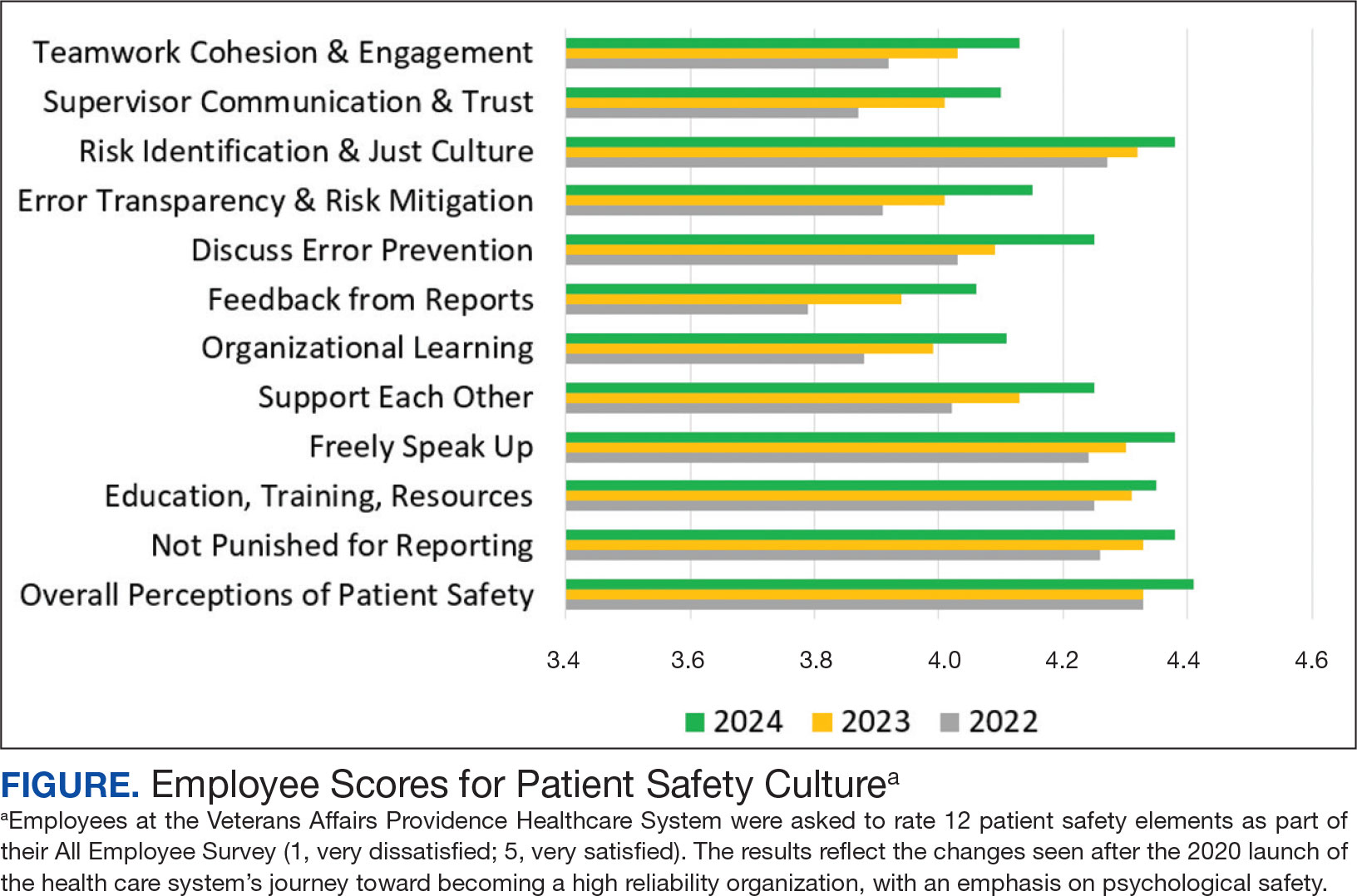

VAPHCS has seen the results of implementing the strategies outlined here. For example, VAPHCS has observed a 45% increase in the use of the patient safety reporting system that logs medical errors and near-misses. In addition, there have been improvements in levels of psychological safety and patient safety reported in the annual VHA All Employee Survey, which is conducted annually to gauge workplace satisfaction, culture, climate, turnover, supervisory behaviors, and general workplace perceptions. VAPHCS has shown consistent improvements in 12 patient safety elements scored on a 5-point scale (1, very dissatisfied; 5, very satisfied) (Figure). Notably, employee ratings of error prevention discussed increased from 4.0 in 2022 to 4.3 in 2024. Data collection and analysis are ongoing; more comprehensive findings will be published in the future.

CONCLUSIONS

Health care organizations are increasingly recognizing the importance of psychologically safe workplaces in order to provide safe, high-quality patient care. Psychological safety is a critical tool for empowering staff to raise concerns, ask tough questions, challenge the status quo, and share new ideas for providing health care services. While psychological safety has been slowly adopted in health care, it’s clear that evidence-based strategies can make psychological safety a reality.

- Spanos S, Leask E, Patel R, Datyner M, Loh E, Braithwaite J. Healthcare leaders navigating complexity: A scoping review of key trends in future roles and competencies. BMC Med Educ. 2024;24(1):720. doi:10.1186/s12909-024-05689-4

- Murray JS, Baghdadi A, Dannenberg W, Crews P, Walsh ND. The role of high reliability organization foundational practices in building a culture of safety. Fed Pract. 2024;41(7):214-221. doi:10.12788/fp.0486

- Bransby DP, Kerrissey M, Edmondson AC. Paradise lost (and restored?): a study of psychological safety over time. Acad Manag Discov. Published online March 14, 2024. doi:10.5465/amd.2023.0084

- Murray JS, Kelly S, Hanover C. Promoting psychological safety in healthcare organizations. Mil Med. 2022;187(7-8):808-810. doi:10.1093/milmed/usac041

- Jamal N, Young VN, Shapiro J, Brenner MJ, Schmalbach CE. Patient safety/quality improvement primer, part IV: Psychological safety-drivers to outcomes and well-being. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023;168(4):881-888. doi:10.1177/01945998221126966

- Sarofim M. Psychological safety in medicine: What is it, and who cares? Med J Aust. 2024;220(8):398-399. doi:10.5694/mja2.52263

- Edmondson AC, Bransby DP. Psychological safety comes of age: Observed themes in an established literature. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav. 2023;10:55-78. doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-120920-055217

- Kumar S. Psychological safety: What it is, why teams need it, and how to make it flourish. Chest. 2024; 165(4):942-949. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2023.11.016

- Hallam KT, Popovic N, Karimi L. Identifying the key elements of psychologically safe workplaces in healthcare settings. Brain Sci. 2023;13(10):1450. doi:10.3390/brainsci13101450

- Grailey KE, Murray E, Reader T, Brett SJ. The presence and potential impact of psychological safety in the healthcare setting: an evidence synthesis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):773. doi:10.1186/s12913-021-06740-6

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VISN 1: VA New England Healthcare System. Accessed March 25, 2025. https://department.va.gov/integrated-service-networks/visn-01

- Brimhall KC, Tsai CY, Eckardt R, Dionne S, Yang B, Sharp A. The effects of leadership for self-worth, inclusion, trust, and psychological safety on medical error reporting. Health Care Manage Rev. 2023;48(2):120-129. doi:10.1097/HMR.0000000000000358

- Adair KC, Heath A, Frye MA, et al. The Psychological Safety Scale of the Safety, Communication, Operational, Reliability, and Engagement (SCORE) Survey: a brief, diagnostic, and actionable metric for the ability to speak up in healthcare settings. J Patient Saf. 2022;18(6):513-520. doi:10.1097/PTS.0000000000001048

- Cho H, Steege LM, Arsenault Knudsen ÉN. Psychological safety, communication openness, nurse job outcomes, and patient safety in hospital nurses. Res Nurs Health. 2023;46(4):445-453.

- Practical Tool 2: 5 minute psychological safety audit. Accessed March 25, 2025. https://www.educationsupport.org.uk/media/jlnf3cju/practical-tool-2-psychological-safety-audit.pdf

Worldwide, health care is becoming increasingly complex as a result of greater clinical workforce demands, expanded roles and responsibilities, health care system mergers, stakeholder calls for new capabilities, and digital transformation. 1,2These increasing demands has prompted many health care institutions to place greater focus on the psychological safety of their workforce, particularly in high reliability organizations (HROs). Building a robust foundation for high reliability in health care requires the presence of psychological safety—that is, staff members at all levels of the organization must feel comfortable speaking up when they have questions or concerns.3,4 Psychological safety can improve the safety and quality of patient care but has not reached its full potential in health care.5,6 However, there are strategies that promote the widespread implementation of psychological safety in health care organizations.3-6

PSYCHOLOGICAL SAFETY

The concept of psychological safety in organizational behavior originated in 1965 when Edgar Schein and Warren Bennis, leaders in organizational psychology and management, published their reflections on the importance of psychological safety in helping individuals feel secure in the work environment.5-7 Psychological safety in the workplace is foundational to staff members feeling comfortable asking questions or expressing concerns without fear of negative consequences.8,9 It supports both individual and team efforts to raise safety concerns and report near misses and adverse events so that similar events can be averted in the future.9 Patients aren’t the only ones who benefit; psychological safety has also been found to promote job satisfaction and employee well-being.10

THE VETERANS HEALTH ADMINISTRATION JOURNEY

Achieving psychological safety is by no means an easy or comfortable process. As with any organizational change, a multipronged approach offers the best chance of success.6,9 When the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) began its incremental, enterprise-wide journey to high reliability in 2019, 3 cohorts were identified. In February 2019, 18 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers (VAMCs) (cohort 1) began the process of becoming HROs. Cohort 2 followed in October 2020 and included 54 VAMC. Finally, in October 2021, 67 additional VAMCs (cohort 3) started the process.2 During cohort 2, the VA Providence Healthcare System (VAPHCS) decided to emphasize psychological safety at the start of the journey to becoming an HRO. This system is part of the VA New England Healthcare System (VISN 1), which includes VAMCs and clinics in Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont.11 Soon thereafter, the VA Bedford Healthcare System and the VA Connecticut Healthcare System adopted similar strategies. Since then, other VAMCs have also adopted this approach. These collective experiences identified 4 useful strategies for achieving psychological safety: leadership engagement, open communication, education and training, and accountability.

Leadership Engagement

Health care organization leaders play a critical role in making psychological safety happen—especially in complex and constantly changing environments, such as HROs.4 Leaders behaviors are consistently linked to the perception of psychological safety at the individual, team, and organizational levels.8 It is especially important to have leaders who recognize the views of individuals and team members and encourage staff participation in discussions to gain additional perspectives.7,8,12 Psychological safety can also be facilitated when leaders are visible, approachable, and communicative.4,7-9

Organizational practices, policies, and processes (eg, reporting adverse events without the fear of negative consequences) are also important ways that leaders can establish and sustain psychological safety. On a more granular level, leaders can enhance psychological safety by promoting and acknowledging individuals who speak up, regularly asking staff about safety concerns, highlighting “good catches” when harm is avoided, and using staff feedback to initiate improvements.4,7,13Finally, in the authors’ experience, psychological safety requires clear commitment from leaders at all levels of an organization. Communication should be bidirectional, and leaders should close the proverbial “loop” with feedback and timely follow-up. This encourages and reinforces staff engagement and speaking up behaviors.2,4,7,13

Open Communication

Promoting an environment of open communication, where all individuals and teams feel empowered to speak up with questions, concerns, and recommendations—regardless of position within the organization—is critical to psychological safety.4,6,9 Open communication is especially critical when processes and systems are constantly changing and advancing as a result of new information and technology.9 Promoting open, bidirectional communication during the delivery of patient care can be accomplished with huddles, tiered safety huddles, leader rounding for high reliability, and time-outs.2,4,6 These opportunities allow team members to discuss concerns, identify resources that support safe, high-quality care; reflect on successes and opportunities for improvement; and circle back on concerns.2,6 Open communication in psychologically safe environments empowers staff to raise patient care concerns and is instrumental for improving patient safety, increasing staff job satisfaction, and decreasing turnover.6,14

Education and Training

Education and training for all staff—from the frontline to the executive level—are essential to successfully implementing the principles and practices of psychological safety.5-7 VHA training covers many topics, including the origins, benefits, and implementation strategies of psychological safety (Table). Role-playing simulation is an effective teaching format, providing staff with opportunities to practice techniques for raising concerns or share feedback in a controlled environment.6 In addition, education should be ongoing; it helps leaders and staff members feel competent and confident when implementing psychological safety across the health care organization.6,10

Accountability

The final critical strategy for achieving psychological safety is accountability. It is the responsibility of all leadership—from senior leaders to clinical and nonclinical managers—to create a culture of shared accountability.5 But first, expectations must be set. Leadership must establish well-defined behavioral expectations that align with the organization’s values. Understanding behavioral expectations will help to ensure that employees know what achievement looks like, as well as how they are being held accountable for their individual actions.4,5,7 In practical terms, this means ensuring that staff members have the skills and resources to achieve goals and expectations, providing performance feedback in a timely manner, and including expectations in annual performance evaluations (as they are in the VHA).

Consistency is key. Accountability should be the expectation across all levels and services of the health care organization. No staff member should be exempt from promoting a psychologically safe work environment. Compliance with behavioral expectations should be monitored and if a person’s actions are not consistent with expectations, the situation will need to be addressed. Interventions will depend on the type, severity, and frequency of the problematic behaviors. Depending on an organization’s policies and practices, courses of action can range from feedback counseling to employment termination.5

A practical matter in ensuring accountability is implementing a psychologically safe process for reporting concerns. Staff members must feel comfortable reporting behavioral concerns without fear of retaliation, negative judgment, or consequences from peers and supervisors. One method for doing this is to create a confidential, centralized process for reporting concerns.5

First-Hand Results

VAPHCS has seen the results of implementing the strategies outlined here. For example, VAPHCS has observed a 45% increase in the use of the patient safety reporting system that logs medical errors and near-misses. In addition, there have been improvements in levels of psychological safety and patient safety reported in the annual VHA All Employee Survey, which is conducted annually to gauge workplace satisfaction, culture, climate, turnover, supervisory behaviors, and general workplace perceptions. VAPHCS has shown consistent improvements in 12 patient safety elements scored on a 5-point scale (1, very dissatisfied; 5, very satisfied) (Figure). Notably, employee ratings of error prevention discussed increased from 4.0 in 2022 to 4.3 in 2024. Data collection and analysis are ongoing; more comprehensive findings will be published in the future.

CONCLUSIONS

Health care organizations are increasingly recognizing the importance of psychologically safe workplaces in order to provide safe, high-quality patient care. Psychological safety is a critical tool for empowering staff to raise concerns, ask tough questions, challenge the status quo, and share new ideas for providing health care services. While psychological safety has been slowly adopted in health care, it’s clear that evidence-based strategies can make psychological safety a reality.

Worldwide, health care is becoming increasingly complex as a result of greater clinical workforce demands, expanded roles and responsibilities, health care system mergers, stakeholder calls for new capabilities, and digital transformation. 1,2These increasing demands has prompted many health care institutions to place greater focus on the psychological safety of their workforce, particularly in high reliability organizations (HROs). Building a robust foundation for high reliability in health care requires the presence of psychological safety—that is, staff members at all levels of the organization must feel comfortable speaking up when they have questions or concerns.3,4 Psychological safety can improve the safety and quality of patient care but has not reached its full potential in health care.5,6 However, there are strategies that promote the widespread implementation of psychological safety in health care organizations.3-6

PSYCHOLOGICAL SAFETY

The concept of psychological safety in organizational behavior originated in 1965 when Edgar Schein and Warren Bennis, leaders in organizational psychology and management, published their reflections on the importance of psychological safety in helping individuals feel secure in the work environment.5-7 Psychological safety in the workplace is foundational to staff members feeling comfortable asking questions or expressing concerns without fear of negative consequences.8,9 It supports both individual and team efforts to raise safety concerns and report near misses and adverse events so that similar events can be averted in the future.9 Patients aren’t the only ones who benefit; psychological safety has also been found to promote job satisfaction and employee well-being.10

THE VETERANS HEALTH ADMINISTRATION JOURNEY

Achieving psychological safety is by no means an easy or comfortable process. As with any organizational change, a multipronged approach offers the best chance of success.6,9 When the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) began its incremental, enterprise-wide journey to high reliability in 2019, 3 cohorts were identified. In February 2019, 18 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers (VAMCs) (cohort 1) began the process of becoming HROs. Cohort 2 followed in October 2020 and included 54 VAMC. Finally, in October 2021, 67 additional VAMCs (cohort 3) started the process.2 During cohort 2, the VA Providence Healthcare System (VAPHCS) decided to emphasize psychological safety at the start of the journey to becoming an HRO. This system is part of the VA New England Healthcare System (VISN 1), which includes VAMCs and clinics in Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont.11 Soon thereafter, the VA Bedford Healthcare System and the VA Connecticut Healthcare System adopted similar strategies. Since then, other VAMCs have also adopted this approach. These collective experiences identified 4 useful strategies for achieving psychological safety: leadership engagement, open communication, education and training, and accountability.

Leadership Engagement

Health care organization leaders play a critical role in making psychological safety happen—especially in complex and constantly changing environments, such as HROs.4 Leaders behaviors are consistently linked to the perception of psychological safety at the individual, team, and organizational levels.8 It is especially important to have leaders who recognize the views of individuals and team members and encourage staff participation in discussions to gain additional perspectives.7,8,12 Psychological safety can also be facilitated when leaders are visible, approachable, and communicative.4,7-9

Organizational practices, policies, and processes (eg, reporting adverse events without the fear of negative consequences) are also important ways that leaders can establish and sustain psychological safety. On a more granular level, leaders can enhance psychological safety by promoting and acknowledging individuals who speak up, regularly asking staff about safety concerns, highlighting “good catches” when harm is avoided, and using staff feedback to initiate improvements.4,7,13Finally, in the authors’ experience, psychological safety requires clear commitment from leaders at all levels of an organization. Communication should be bidirectional, and leaders should close the proverbial “loop” with feedback and timely follow-up. This encourages and reinforces staff engagement and speaking up behaviors.2,4,7,13

Open Communication

Promoting an environment of open communication, where all individuals and teams feel empowered to speak up with questions, concerns, and recommendations—regardless of position within the organization—is critical to psychological safety.4,6,9 Open communication is especially critical when processes and systems are constantly changing and advancing as a result of new information and technology.9 Promoting open, bidirectional communication during the delivery of patient care can be accomplished with huddles, tiered safety huddles, leader rounding for high reliability, and time-outs.2,4,6 These opportunities allow team members to discuss concerns, identify resources that support safe, high-quality care; reflect on successes and opportunities for improvement; and circle back on concerns.2,6 Open communication in psychologically safe environments empowers staff to raise patient care concerns and is instrumental for improving patient safety, increasing staff job satisfaction, and decreasing turnover.6,14

Education and Training

Education and training for all staff—from the frontline to the executive level—are essential to successfully implementing the principles and practices of psychological safety.5-7 VHA training covers many topics, including the origins, benefits, and implementation strategies of psychological safety (Table). Role-playing simulation is an effective teaching format, providing staff with opportunities to practice techniques for raising concerns or share feedback in a controlled environment.6 In addition, education should be ongoing; it helps leaders and staff members feel competent and confident when implementing psychological safety across the health care organization.6,10

Accountability

The final critical strategy for achieving psychological safety is accountability. It is the responsibility of all leadership—from senior leaders to clinical and nonclinical managers—to create a culture of shared accountability.5 But first, expectations must be set. Leadership must establish well-defined behavioral expectations that align with the organization’s values. Understanding behavioral expectations will help to ensure that employees know what achievement looks like, as well as how they are being held accountable for their individual actions.4,5,7 In practical terms, this means ensuring that staff members have the skills and resources to achieve goals and expectations, providing performance feedback in a timely manner, and including expectations in annual performance evaluations (as they are in the VHA).

Consistency is key. Accountability should be the expectation across all levels and services of the health care organization. No staff member should be exempt from promoting a psychologically safe work environment. Compliance with behavioral expectations should be monitored and if a person’s actions are not consistent with expectations, the situation will need to be addressed. Interventions will depend on the type, severity, and frequency of the problematic behaviors. Depending on an organization’s policies and practices, courses of action can range from feedback counseling to employment termination.5

A practical matter in ensuring accountability is implementing a psychologically safe process for reporting concerns. Staff members must feel comfortable reporting behavioral concerns without fear of retaliation, negative judgment, or consequences from peers and supervisors. One method for doing this is to create a confidential, centralized process for reporting concerns.5

First-Hand Results

VAPHCS has seen the results of implementing the strategies outlined here. For example, VAPHCS has observed a 45% increase in the use of the patient safety reporting system that logs medical errors and near-misses. In addition, there have been improvements in levels of psychological safety and patient safety reported in the annual VHA All Employee Survey, which is conducted annually to gauge workplace satisfaction, culture, climate, turnover, supervisory behaviors, and general workplace perceptions. VAPHCS has shown consistent improvements in 12 patient safety elements scored on a 5-point scale (1, very dissatisfied; 5, very satisfied) (Figure). Notably, employee ratings of error prevention discussed increased from 4.0 in 2022 to 4.3 in 2024. Data collection and analysis are ongoing; more comprehensive findings will be published in the future.

CONCLUSIONS

Health care organizations are increasingly recognizing the importance of psychologically safe workplaces in order to provide safe, high-quality patient care. Psychological safety is a critical tool for empowering staff to raise concerns, ask tough questions, challenge the status quo, and share new ideas for providing health care services. While psychological safety has been slowly adopted in health care, it’s clear that evidence-based strategies can make psychological safety a reality.

- Spanos S, Leask E, Patel R, Datyner M, Loh E, Braithwaite J. Healthcare leaders navigating complexity: A scoping review of key trends in future roles and competencies. BMC Med Educ. 2024;24(1):720. doi:10.1186/s12909-024-05689-4

- Murray JS, Baghdadi A, Dannenberg W, Crews P, Walsh ND. The role of high reliability organization foundational practices in building a culture of safety. Fed Pract. 2024;41(7):214-221. doi:10.12788/fp.0486

- Bransby DP, Kerrissey M, Edmondson AC. Paradise lost (and restored?): a study of psychological safety over time. Acad Manag Discov. Published online March 14, 2024. doi:10.5465/amd.2023.0084

- Murray JS, Kelly S, Hanover C. Promoting psychological safety in healthcare organizations. Mil Med. 2022;187(7-8):808-810. doi:10.1093/milmed/usac041

- Jamal N, Young VN, Shapiro J, Brenner MJ, Schmalbach CE. Patient safety/quality improvement primer, part IV: Psychological safety-drivers to outcomes and well-being. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023;168(4):881-888. doi:10.1177/01945998221126966

- Sarofim M. Psychological safety in medicine: What is it, and who cares? Med J Aust. 2024;220(8):398-399. doi:10.5694/mja2.52263

- Edmondson AC, Bransby DP. Psychological safety comes of age: Observed themes in an established literature. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav. 2023;10:55-78. doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-120920-055217

- Kumar S. Psychological safety: What it is, why teams need it, and how to make it flourish. Chest. 2024; 165(4):942-949. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2023.11.016

- Hallam KT, Popovic N, Karimi L. Identifying the key elements of psychologically safe workplaces in healthcare settings. Brain Sci. 2023;13(10):1450. doi:10.3390/brainsci13101450

- Grailey KE, Murray E, Reader T, Brett SJ. The presence and potential impact of psychological safety in the healthcare setting: an evidence synthesis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):773. doi:10.1186/s12913-021-06740-6

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VISN 1: VA New England Healthcare System. Accessed March 25, 2025. https://department.va.gov/integrated-service-networks/visn-01

- Brimhall KC, Tsai CY, Eckardt R, Dionne S, Yang B, Sharp A. The effects of leadership for self-worth, inclusion, trust, and psychological safety on medical error reporting. Health Care Manage Rev. 2023;48(2):120-129. doi:10.1097/HMR.0000000000000358

- Adair KC, Heath A, Frye MA, et al. The Psychological Safety Scale of the Safety, Communication, Operational, Reliability, and Engagement (SCORE) Survey: a brief, diagnostic, and actionable metric for the ability to speak up in healthcare settings. J Patient Saf. 2022;18(6):513-520. doi:10.1097/PTS.0000000000001048

- Cho H, Steege LM, Arsenault Knudsen ÉN. Psychological safety, communication openness, nurse job outcomes, and patient safety in hospital nurses. Res Nurs Health. 2023;46(4):445-453.

- Practical Tool 2: 5 minute psychological safety audit. Accessed March 25, 2025. https://www.educationsupport.org.uk/media/jlnf3cju/practical-tool-2-psychological-safety-audit.pdf

- Spanos S, Leask E, Patel R, Datyner M, Loh E, Braithwaite J. Healthcare leaders navigating complexity: A scoping review of key trends in future roles and competencies. BMC Med Educ. 2024;24(1):720. doi:10.1186/s12909-024-05689-4

- Murray JS, Baghdadi A, Dannenberg W, Crews P, Walsh ND. The role of high reliability organization foundational practices in building a culture of safety. Fed Pract. 2024;41(7):214-221. doi:10.12788/fp.0486

- Bransby DP, Kerrissey M, Edmondson AC. Paradise lost (and restored?): a study of psychological safety over time. Acad Manag Discov. Published online March 14, 2024. doi:10.5465/amd.2023.0084

- Murray JS, Kelly S, Hanover C. Promoting psychological safety in healthcare organizations. Mil Med. 2022;187(7-8):808-810. doi:10.1093/milmed/usac041

- Jamal N, Young VN, Shapiro J, Brenner MJ, Schmalbach CE. Patient safety/quality improvement primer, part IV: Psychological safety-drivers to outcomes and well-being. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023;168(4):881-888. doi:10.1177/01945998221126966

- Sarofim M. Psychological safety in medicine: What is it, and who cares? Med J Aust. 2024;220(8):398-399. doi:10.5694/mja2.52263

- Edmondson AC, Bransby DP. Psychological safety comes of age: Observed themes in an established literature. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav. 2023;10:55-78. doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-120920-055217

- Kumar S. Psychological safety: What it is, why teams need it, and how to make it flourish. Chest. 2024; 165(4):942-949. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2023.11.016

- Hallam KT, Popovic N, Karimi L. Identifying the key elements of psychologically safe workplaces in healthcare settings. Brain Sci. 2023;13(10):1450. doi:10.3390/brainsci13101450

- Grailey KE, Murray E, Reader T, Brett SJ. The presence and potential impact of psychological safety in the healthcare setting: an evidence synthesis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):773. doi:10.1186/s12913-021-06740-6

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VISN 1: VA New England Healthcare System. Accessed March 25, 2025. https://department.va.gov/integrated-service-networks/visn-01

- Brimhall KC, Tsai CY, Eckardt R, Dionne S, Yang B, Sharp A. The effects of leadership for self-worth, inclusion, trust, and psychological safety on medical error reporting. Health Care Manage Rev. 2023;48(2):120-129. doi:10.1097/HMR.0000000000000358

- Adair KC, Heath A, Frye MA, et al. The Psychological Safety Scale of the Safety, Communication, Operational, Reliability, and Engagement (SCORE) Survey: a brief, diagnostic, and actionable metric for the ability to speak up in healthcare settings. J Patient Saf. 2022;18(6):513-520. doi:10.1097/PTS.0000000000001048

- Cho H, Steege LM, Arsenault Knudsen ÉN. Psychological safety, communication openness, nurse job outcomes, and patient safety in hospital nurses. Res Nurs Health. 2023;46(4):445-453.

- Practical Tool 2: 5 minute psychological safety audit. Accessed March 25, 2025. https://www.educationsupport.org.uk/media/jlnf3cju/practical-tool-2-psychological-safety-audit.pdf

Achieving Psychological Safety in High Reliability Organizations

Achieving Psychological Safety in High Reliability Organizations