User login

A 32-year-old woman presented to our emergency department with chest pain and painful ulcerations on her arms, abdomen, back, groin, axillae, and in her mouth. She first noticed the ulcers 7 days earlier.

She also reported bloody diarrhea, which had started 2 years earlier, with 10 or more bowel movements daily. She described her stools as semiformed and associated with urgency and painful abdominal cramps.

Medical history

Her medical history included obstructive sleep apnea and morbid obesity. She had first presented 2 years earlier to another hospital with diarrhea, abdominal pain, and rectal bleeding. At that time, results of esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy were reported as normal. Later, she became pregnant, and her symptoms went away. She had a normal pregnancy and delivery.

About 1 year postpartum, her abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea recurred. Colonoscopy showed severe sigmoid inflammation with small, shallow ulcerations and friable mucosa interrupted by areas of normal mucosa. Histopathologic study of the colonic mucosa indicated mild to moderate chronic active colitis consisting of focal areas of cryptitis with occasional crypt abscess formation. She was diagnosed with Crohn colitis based on the endoscopic appearance, histopathology, and clinical presentation. The endoscope, however, could not be advanced beyond the sigmoid colon, which suggested stenosis. She was started on 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) but developed visual hallucinations, and the medication was stopped.

Her symptoms continued, and she developed worsening rectal bleeding and anemia that required hospitalization and blood transfusions. Another colonoscopy performed 1 month before this emergency department visit had shown multiple mucosal ulcerations, but again, the colonoscope could not be advanced beyond the sigmoid colon. She was started on oral corticosteroids, which provided only minimal clinical improvement.

Her current medications included atenolol (for sinus tachycardia), prednisone (initial dose 60 mg/day tapered to 20 mg/day at presentation), and ciprofloxacin.

Her family history was unknown because she had been adopted.

About 1 week before presentation, she had noticed ulcers developing on her arms, abdomen, back, groin, oral mucosa, and axillae. The ulcers were large and painful, with occasional spontaneous bleeding. She also reported pustules and ulcerations at sites of previous skin punctures, consistent with pathergy.

Findings on presentation

- Temperature 99.5°F (37.5°C)

- Heart rate 124 beats per minute

- Respiratory rate 22 breaths per minute

- Oxygen saturation 100% on room air

- Blood pressure 128/81 mm Hg

- Body mass index 67 kg/m2 (morbidly obese).

She had multiple greyish-white patches and erosions over the soft palate, tongue, and upper and lower lip mucosa, erythematous pustules in the axillae bilaterally, and large erythematous, sharply demarcated ulcerations with a fibrinous base bilaterally covering her arms, thighs, groin, and abdomen.

Blood testing showed multiple abnormal results (Table 1). Urinalysis revealed a urine protein concentration of 100 mg/dL (reference range 0), more than 25 white blood cells per high-power field (reference range < 5), 6 to 10 red blood cells per high-power field (0–3), and more than 10 casts per low-power field (0), which suggested a urinary tract infection with hematuria.

Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous and oral contrast showed diffuse fatty infiltration of the liver and wall thickening of the rectum and sigmoid colon.

She was admitted to the medical intensive care unit for potential septic shock. Intravenous vancomycin and ciprofloxacin were started (the latter owing to penicillin allergy).

CAUSES OF DIARRHEA AND SKIN CHANGES

1. What is the most likely diagnosis in our patient?

- Ulcerative colitis

- Crohn disease

- Behçet disease

- Intestinal tuberculosis

- Herpes simplex virus infection

- Cytomegalovirus infection

All of the above can cause diarrhea in combination with mucocutaneous lesions and other manifestations.

Ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease: Mucocutaneous findings

Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel diseases (Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis, and Behçet disease) include arthritis, ocular involvement, mucocutaneous manifestations, and liver involvement in the form of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Less common extraintestinal manifestations include vascular, renal, pulmonary, cardiac, and neurologic involvement.

Mucocutaneous findings are observed in 5% to 10% of patients with ulcerative colitis and 20% to 75% of patients with Crohn disease.1–3 The most common are erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum.4

Yüksel et al5 reported that of 352 patients with inflammatory bowel disease, 7.4% had erythema nodosum and 2.3% had pyoderma gangrenosum. Erythema nodosum was significantly more common in patients with Crohn disease than in those with ulcerative colitis, and its severity was linked with higher disease activity. Lesions frequently resolved when bowel disease subsided.

Lebwohl and Lebwohl6 reported that pyoderma gangrenosum occurred in up to 20% of patients with Crohn disease and up to 10% of those with ulcerative colitis. It is not known whether pyoderma gangrenosum correlates with intestinal disease severity.

Other mucocutaneous manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease include oral aphthous ulcers, acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet syndrome), and metastatic Crohn disease. Aphthous ulcers in the oral cavity, often observed in both Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis, cannot be differentiated on clinical examination from herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1-induced or idiopathic mucous membrane ulcers. The most common ulcer locations are the lips and buccal mucosa. If biopsied (seldom required), noncaseating granulomas can be identified that are comparable with intestinal mucosal granulomas found in Crohn disease.7

Behçet disease has similar signs

Oral aphthous ulcers are also the most frequent symptom in Behçet disease, occurring in 97% to 100% of cases.8 They most commonly affect the tongue, lips, buccal mucosa, and gingiva.

Cutaneous manifestations include erythema nodosum-like lesions, which present as erythematous painful nodules over pretibial surfaces of the lower limbs but can also affect the arms and thighs; they can also present as papulopustular rosacea eruptions composed of papules, pustules, and noninflammatory comedones, most commonly on the chest, back, and shoulders.8,9

Pathergy, ie, skin hyperresponse to minor trauma such as a bump or bruise, is a typical trait of Behçet disease. A positive pathergy test (ie, skin hyperreactivity to a needlestick or intracutaneous injection) has a specificity of 98.4% in patients with Behçet disease.10

Interestingly, there appears to be a regional difference in the susceptibility to pathergy. While a pathergy response in patients with Behçet disease is rare in the United States and the United Kingdom, it is very common in Japan, Turkey, and Israel.11

Patient demographics also distinguish Behçet disease from Crohn disease. The prevalence of Behçet disease is highest along the Silk Road from the Mediterranean Basin to East Asia and lowest in North America and Northern Europe.12 The mean age at onset is around the third and fourth decades. In males, the prevalence is highest in Mediterranean, Middle Eastern, and Asian countries. In females, the prevalence is highest in the United States, Northern Europe, and East Asia.10

Tuberculosis

Tubercular skin lesions can present in different forms.13 Lupus vulgaris, the most common, occurs after primary infection and presents as translucent brown nodules, mainly over the face and neck. So-called scrofuloderma is common at the site of a lymph node. It appears as a gradually enlarging subcutaneous nodule followed by skin breaks and ulcerations. Tuberculosis verrucosa cutis, also known as warty tuberculosis, is common in developing countries and presents as warty plaque over the hands, knees, and buttocks.14 Tuberculids are skin reactions to systemic tuberculosis infection.

Herpes simplex virus

Mucocutaneous manifestations of herpes simplex virus affect the oral cavity (gingivostomatitis, pharyngitis, and lip border lesions), the entire integumentary system, the eyes (HSV-1), and the genital region (HSV-2). The classic presentation is systemic symptoms (fever and malaise) associated with multiple vesicles on an erythematous base in a distinct region of skin. The virus can remain latent with reactivation occurring because of illness, immunosuppression, or stress. Pruritus and pain precede the appearance of these lesions.

Cytomegalovirus

Primary cytomegalovirus infection is subclinical in almost all cases unless the patient is immunocompromised, and it presents similarly to mononucleosis induced by Epstein-Barr virus. The skin manifestations are nonspecific and can include macular, maculopapular, morbilliform, and urticarial rashes, but usually not ulcerations.15

OUR PATIENT: BEHÇET DISEASE OR CROHN DISEASE?

In our patient, oral mucosal aphthous ulcers and the location of pustular skin lesions, in addition to pathergy, were highly suggestive of Behçet disease. However, Crohn disease with mucocutaneous manifestations remained in the differential diagnosis.

Because there is significant overlap between these diseases, it is important to know the key distinguishing features. Oral aphthous ulcers, pathergy, uveitis, skin and genital lesions, and neurologic involvement are much more common in Behçet disease than in Crohn disease.16,17 Demographic information was not helpful in this case, given that the patient was adopted.

FURTHER WORKUP

2. What should be the next step in the work-up?

- CT enterography

- Skin biopsy

- Colonoscopy with biopsy

- C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and fecal calprotecting testing

The endoscopic appearance and histopathology of the affected tissues are crucial for the diagnosis. Differentiating between Crohn disease and Behçet disease can be particularly challenging because of significant overlap between the intestinal and extraintestinal manifestations of the two diseases, especially the oral lesions and arthralgias. Thus, both colonoscopy with biopsy of the intestinal lesions and biopsy of a cutaneous ulceration should be pursued.

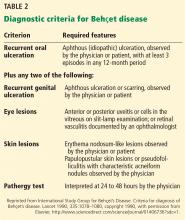

No single test or feature is pathognomonic for Behçet disease. Although many diagnostic criteria have been established, those of the International Study Group (Table 2) are the most widely used.18 Their sensitivity for Behçet disease has been found to be 92%, and their specificity 97%.19

Both CT enterography and inflammatory markers would depict inflammation, but since this is present in both Crohn disease and Behçet disease, these tests would not be helpful in this situation.

Endoscopic appearance of Crohn disease and Behçet disease

Intestinal Behçet disease, like Crohn disease, is an inflammatory bowel disease occurring throughout the gastrointestinal tract (small and large bowel). Both are chronic diseases with a waxing and waning course and have similar extraintestinal manifestations. Typical endoscopic lesions are deep, sharply demarcated (“punched-out”), round ulcers. The intestinal Behçet disease and Crohn disease ulcer phenotype and distribution can look the same, and in both entities, rectal sparing and “skip lesions” have been described.20–22

Nevertheless, findings on endoscopy have been analyzed to try to differentiate between Crohn disease and Behçet disease.

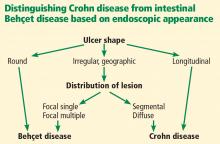

In 2009, Lee et al23 published a simple and accurate strategy for distinguishing the two diseases endoscopically. The authors reviewed 250 patients (115 with Behçet disease, 135 with Crohn disease) with ulcers on colonoscopy and identified 5 endoscopic findings indicative of intestinal Behçet disease:

- Round ulcers

- Focal single or focal multiple distribution of ulcers

- Fewer than 6 ulcers

- Absence of a “cobblestone” appearance

- Absence of aphthous lesions.

The two most accurate factors were absence of a cobblestone appearance (sensitivity 100%) and round ulcer shape (specificity 97.5 %). When more than one factor was present, specificity increased but sensitivity decreased.

Using a classification and regression tree analysis, the investigators created an algorithm that endoscopically differentiates between Crohn disease and Behçet disease (Figure 1) with an accuracy of 92 %.23

Histopathologic analysis of both colonic and skin lesions can provide additional clues to the correct diagnosis. Vasculitis suggests Behçet disease, whereas granulomas suggest Crohn disease.

CASE CONTINUED: SKIN BIOPSY AND COLONOSCOPY

Punch biopsy of the skin was performed on the right anterior thigh. Histopathologic analysis revealed acanthotic epidermis, a discrete full-thickness necrotic ulcer with a neutrophilic base, granulation tissue, and vasculitic changes. There were no vasculitic changes or granulomas outside the ulcer base. Cytomegalovirus staining was negative. An interferon-gamma release assay for tuberculosis was negative. Eye examination results were normal.

Colonoscopy showed multiple deep, round, and confluent ulcers with a punched-out appearance and fissures with normal intervening mucosa in the entire examined colon (Figure 2). The terminal ileal mucosa was normal. Colonic biopsies were consistent with cryptitis and rare crypt abscesses. Vasculitis was not identified.

Although the histologic changes were nonspecific, at this point we considered Behçet disease to be more likely than Crohn disease, given the typical endoscopic appearance and skin changes.

TREATING INTESTINAL BEHÇET DISEASE

3. Which is not considered a standard treatment for intestinal Behçet disease?

- Mesalamine (5-ASA)

- Corticosteroids

- Immunosuppressants

- Mycophenolate mofetil

- Surgery

Overall, data on the management of intestinal Behçet disease are limited. The data that do exist have shown that 5-ASA, corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, and surgery are options, but not mycophenolate mofetil.

Consensus recommendations from the Japanese IBD Research Group,24 published in 2007, included 5-ASA, corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, enteral and total parenteral nutrition, and surgical resection. In 2014, the group published a second consensus statement, adding anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents as standard therapy for this disease.22

Mycophenolate mofetil has not been shown to be effective in the treatment of mucocutaneous Behçet disease,25 although it may be effective in the treatment of its neurologic manifestations.26 Data regarding its efficacy in intestinal Behçet disease are sparse.

Differences in treatment for Crohn and Behçet disease

Although the treatment options are comparable for Behçet disease and Crohn disease, certain features differ.

Doses of 5-ASA and immunnosuppressive agents are typically higher in Crohn disease. For example, the optimal dose of 5-ASA is up to 3 g/day for Behçet disease but up to 4.8 g/day for Crohn disease.

Standard dosing for azathioprine is 50 to 100 mg/day for Behçet disease but 2 to 2.5 mg/kg/day (eg, 168 to 210 mg/day for a 185-lb patient) for Crohn disease.

In addition, evidence supporting the use of biologic agents such as anti-TNF agents or vedolizumab is more abundant in Crohn disease.

Finally, data on monitoring drug levels of immunomodulators or biologics are available only for patients with Crohn disease, not Behçet disease. Thus, an accurate diagnosis is important.

CASE CONTINUED: EMERGENCY LAPAROTOMY

Our patient continued to experience abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea despite receiving corticosteroids intravenously in high doses. We were also considering anti-TNF therapy.

At this point, CT of her abdomen and pelvis was repeated and showed free intraperitoneal air consistent with a perforation of the transverse colon.

She underwent emergency exploratory laparotomy. Intraoperative findings included pneumoperitoneum but no gross peritoneal contamination, extensive colitis with a contained splenic flexure perforation, and normal small-bowel features without evidence of enteritis. Subtotal colectomy, implantation of the rectal stump into the subcutaneous tissue, and end-ileostomy were performed.

After 23 days of recovery in the hospital, she was discharged on oral antibiotics and 4 weeks of steroid taper.

PROGNOSIS OF INTESTINAL BEHÇET DISEASE

4. What can the patient expect from her intestinal Behçet disease in the future?

- The disease is cured after resection of the diseased segments

- Behçet disease is a progressive lifelong disorder that can recur after surgery

Like Crohn disease, Behçet disease should be considered a lifelong progressive disorder, even after surgical resection of diseased segments.

It is unclear which patients will have a complicated disease course and need treatment with stronger immunosuppression. In patients with intestinal Behçet disease whose disease is in remission on thiopurine therapy, the 1-year relapse rate has been reported as 5.8%, and the 5-year relapse rate 51.7%.27,28 After surgical resection, the 5-year recurrence rate was 47.2%, and 30.6% of patients needed repeat surgery.29 Predictors of poor prognosis were younger age, higher erythrocyte sedimentation rate, higher C-reactive protein level, low albumin level at diagnosis, and a high disease-activity index for intestinal Behçet disease.30

The Korean IBD Study Group has developed and validated a disease activity index for intestinal Behçet disease.28 The index has a list of weighted scores for 8 symptoms, which provides for a more objective assessment of disease activity for determining the best treatment approach.

CASE CONTINUED

The patient has continued with her follow-up care and appointments in gastroenterology, rheumatology, and dermatology clinics. She still complains of intermittent abdominal pain, occasional bleeding at the rectal stump, intermittent skin lesions mainly in the form of pustular lesions, and intermittent joint pain. If symptoms persist, anti-TNF therapy is an option.

- Burgdorf W. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn’s disease. J Am Acad Dermatol 1981; 5:689–695.

- Palamaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: a review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2008; 22:1033–1043.

- Timani S, Mutasim DF. Skin manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Dermatol 2008; 26:265–273.

- Tavarela Veloso F. Skin complications associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004; 20(suppl 4):50–53.

- Yüksel I, Basar O, Ataseven H, et al. Mucocutaneous manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2009; 15:546–550.

- Lebwohl M, Lebwohl O. Cutaneous manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 1998; 4:142–148.

- Levine JS, Burakoff R. Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY) 2011; 7:235–241.

- Mat C, Yurdakul S, Sevim A, Özyazgan Y, Tüzün Y. Behçet’s syndrome: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol 2013; 31:352–361.

- Lee ES, Bangz D, Lee S. Dermatologic manifestation of Behçet’s disease. Yonsei Med J 1997; 38:380–389.

- Davatchi F, Chams-Davatchi C, Ghodsi Z, et al. Diagnostic value of pathergy test in Behçet’s disease according to the change of incidence over the time. Clin Rheumatol 2011; 30:1151–1155.

- Friedman-Birnbaum R, Bergman R, Aizen E. Sensitivity and specificity of pathergy test results in Israeli patients with Behçet’s disease. Cutis 1990; 45:261–264.

- Mahr A, Maldini C. Epidemiology of Behçet’s disease. Rev Med Interne 2014; 35:81–89. French.

- Barbagallo J, Tager P, Ingleton R, Hirsch RJ, Weinberg JM. Cutaneous tuberculosis. Am J Clin Dermatol 2002; 3:319–328.

- Padmavathy L, Lakshmana Rao L, Ethirajan N, Ramakrishna Rao M, Subrahmanyan EN, Manohar U. Tuberculosis verrucosa cutis (TBVC)—foot with miliary tuberculosis. Indian J Tuberc 2007; 54:145–148.

- Drago F, Aragone MG, Lugani C, Rebora A. Cytomegalovirus infection in normal and immunocompromised humans. A review. Dermatology 2000; 200:189–195.

- Yazısız V. Similarities and differences between Behçet’s disease and Crohn’s disease. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol 2014; 5:228–238.

- Chin AB, Kumar AS. Behçet colitis. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2015; 28:99–102.

- International Study Group for Behçet’s Disease. Criteria for diagnosis of Behçet’s disease. Lancet 1990; 335:1078–1080.

- Davatchi F. Diagnosis/classification criteria for Behcet’s disease. Patholog Res Int 2012; 2012:607921.

- Chang DK, Kim JJ, Choi H, et al. Double balloon endoscopy in small intestinal Crohn’s disease and other inflammatory diseases such as cryptogenic multifocal ulcerous stenosing enteritis (CMUSE). Gastrointest Endosc 2007; 66(suppl):S96–S98.

- Hamdulay SS, Cheent K, Ghosh C, Stocks J, Ghosh S, Haskard DO. Wireless capsule endoscopy in the investigation of intestinal Behçet’s syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008; 47:1231–1234.

- Hisamatsu T, Ueno F, Matsumoto T, et al. The 2nd edition of consensus statements for the diagnosis and management of intestinal Behçet’s disease: indication of anti-TNFa monoclonal antibodies. J Gastroenterol 2014; 49:156–162.

- Lee SK, Kim BK, Kim TI, Kim WH. Differential diagnosis of intestinal Behçet’s disease and Crohn’s disease by colonoscopic findings. Endoscopy 2009; 41:9–16.

- Kobayashi K, Ueno F, Bito S, et al. Development of consensus statements for the diagnosis and management of intestinal Behçet’s disease using a modified Delphi approach. J Gastroenterol 2007; 42:737–745.

- Adler YD, Mansmann U, Zouboulis CC. Mycophenolate mofetil is ineffective in the treatment of mucocutaneous Adamantiades-Behçet’s disease. Dermatology 2001; 203:322–324.

- Shugaiv E, Tüzün E, Mutlu M, Kiyat-Atamer A, Kurtuncu M, Akman-Demir G. Mycophenolate mofetil as a novel immunosuppressant in the treatment of neuro-Behçet’s disease with parenchymal involvement: presentation of four cases. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2011; 29(suppl 67):S64–S67.

- Jung YS, Cheon JH, Hong SP, Kim TI, Kim WH. Clinical outcomes and prognostic factors for thiopurine maintenance therapy in patients with intestinal Behçet’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2012; 18:750–757.

- Cheon JH, Han DS, Park JY, et al; Korean IBD Study Group. Development, validation, and responsiveness of a novel disease activity index for intestinal Behçet’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2011; 17:605–613.

- Jung YS, Yoon JY, Lee JH, et al. Prognostic factors and long-term clinical outcomes for surgical patients with intestinal Behçet’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2011; 17:1594–1602.

- Jung YS, Cheon JH, Park SJ, Hong SP, Kim TI, Kim WH. Clinical course of intestinal Behçet’s disease during the first five years. Dig Dis Sci 2013; 58:496–503.

A 32-year-old woman presented to our emergency department with chest pain and painful ulcerations on her arms, abdomen, back, groin, axillae, and in her mouth. She first noticed the ulcers 7 days earlier.

She also reported bloody diarrhea, which had started 2 years earlier, with 10 or more bowel movements daily. She described her stools as semiformed and associated with urgency and painful abdominal cramps.

Medical history

Her medical history included obstructive sleep apnea and morbid obesity. She had first presented 2 years earlier to another hospital with diarrhea, abdominal pain, and rectal bleeding. At that time, results of esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy were reported as normal. Later, she became pregnant, and her symptoms went away. She had a normal pregnancy and delivery.

About 1 year postpartum, her abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea recurred. Colonoscopy showed severe sigmoid inflammation with small, shallow ulcerations and friable mucosa interrupted by areas of normal mucosa. Histopathologic study of the colonic mucosa indicated mild to moderate chronic active colitis consisting of focal areas of cryptitis with occasional crypt abscess formation. She was diagnosed with Crohn colitis based on the endoscopic appearance, histopathology, and clinical presentation. The endoscope, however, could not be advanced beyond the sigmoid colon, which suggested stenosis. She was started on 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) but developed visual hallucinations, and the medication was stopped.

Her symptoms continued, and she developed worsening rectal bleeding and anemia that required hospitalization and blood transfusions. Another colonoscopy performed 1 month before this emergency department visit had shown multiple mucosal ulcerations, but again, the colonoscope could not be advanced beyond the sigmoid colon. She was started on oral corticosteroids, which provided only minimal clinical improvement.

Her current medications included atenolol (for sinus tachycardia), prednisone (initial dose 60 mg/day tapered to 20 mg/day at presentation), and ciprofloxacin.

Her family history was unknown because she had been adopted.

About 1 week before presentation, she had noticed ulcers developing on her arms, abdomen, back, groin, oral mucosa, and axillae. The ulcers were large and painful, with occasional spontaneous bleeding. She also reported pustules and ulcerations at sites of previous skin punctures, consistent with pathergy.

Findings on presentation

- Temperature 99.5°F (37.5°C)

- Heart rate 124 beats per minute

- Respiratory rate 22 breaths per minute

- Oxygen saturation 100% on room air

- Blood pressure 128/81 mm Hg

- Body mass index 67 kg/m2 (morbidly obese).

She had multiple greyish-white patches and erosions over the soft palate, tongue, and upper and lower lip mucosa, erythematous pustules in the axillae bilaterally, and large erythematous, sharply demarcated ulcerations with a fibrinous base bilaterally covering her arms, thighs, groin, and abdomen.

Blood testing showed multiple abnormal results (Table 1). Urinalysis revealed a urine protein concentration of 100 mg/dL (reference range 0), more than 25 white blood cells per high-power field (reference range < 5), 6 to 10 red blood cells per high-power field (0–3), and more than 10 casts per low-power field (0), which suggested a urinary tract infection with hematuria.

Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous and oral contrast showed diffuse fatty infiltration of the liver and wall thickening of the rectum and sigmoid colon.

She was admitted to the medical intensive care unit for potential septic shock. Intravenous vancomycin and ciprofloxacin were started (the latter owing to penicillin allergy).

CAUSES OF DIARRHEA AND SKIN CHANGES

1. What is the most likely diagnosis in our patient?

- Ulcerative colitis

- Crohn disease

- Behçet disease

- Intestinal tuberculosis

- Herpes simplex virus infection

- Cytomegalovirus infection

All of the above can cause diarrhea in combination with mucocutaneous lesions and other manifestations.

Ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease: Mucocutaneous findings

Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel diseases (Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis, and Behçet disease) include arthritis, ocular involvement, mucocutaneous manifestations, and liver involvement in the form of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Less common extraintestinal manifestations include vascular, renal, pulmonary, cardiac, and neurologic involvement.

Mucocutaneous findings are observed in 5% to 10% of patients with ulcerative colitis and 20% to 75% of patients with Crohn disease.1–3 The most common are erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum.4

Yüksel et al5 reported that of 352 patients with inflammatory bowel disease, 7.4% had erythema nodosum and 2.3% had pyoderma gangrenosum. Erythema nodosum was significantly more common in patients with Crohn disease than in those with ulcerative colitis, and its severity was linked with higher disease activity. Lesions frequently resolved when bowel disease subsided.

Lebwohl and Lebwohl6 reported that pyoderma gangrenosum occurred in up to 20% of patients with Crohn disease and up to 10% of those with ulcerative colitis. It is not known whether pyoderma gangrenosum correlates with intestinal disease severity.

Other mucocutaneous manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease include oral aphthous ulcers, acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet syndrome), and metastatic Crohn disease. Aphthous ulcers in the oral cavity, often observed in both Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis, cannot be differentiated on clinical examination from herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1-induced or idiopathic mucous membrane ulcers. The most common ulcer locations are the lips and buccal mucosa. If biopsied (seldom required), noncaseating granulomas can be identified that are comparable with intestinal mucosal granulomas found in Crohn disease.7

Behçet disease has similar signs

Oral aphthous ulcers are also the most frequent symptom in Behçet disease, occurring in 97% to 100% of cases.8 They most commonly affect the tongue, lips, buccal mucosa, and gingiva.

Cutaneous manifestations include erythema nodosum-like lesions, which present as erythematous painful nodules over pretibial surfaces of the lower limbs but can also affect the arms and thighs; they can also present as papulopustular rosacea eruptions composed of papules, pustules, and noninflammatory comedones, most commonly on the chest, back, and shoulders.8,9

Pathergy, ie, skin hyperresponse to minor trauma such as a bump or bruise, is a typical trait of Behçet disease. A positive pathergy test (ie, skin hyperreactivity to a needlestick or intracutaneous injection) has a specificity of 98.4% in patients with Behçet disease.10

Interestingly, there appears to be a regional difference in the susceptibility to pathergy. While a pathergy response in patients with Behçet disease is rare in the United States and the United Kingdom, it is very common in Japan, Turkey, and Israel.11

Patient demographics also distinguish Behçet disease from Crohn disease. The prevalence of Behçet disease is highest along the Silk Road from the Mediterranean Basin to East Asia and lowest in North America and Northern Europe.12 The mean age at onset is around the third and fourth decades. In males, the prevalence is highest in Mediterranean, Middle Eastern, and Asian countries. In females, the prevalence is highest in the United States, Northern Europe, and East Asia.10

Tuberculosis

Tubercular skin lesions can present in different forms.13 Lupus vulgaris, the most common, occurs after primary infection and presents as translucent brown nodules, mainly over the face and neck. So-called scrofuloderma is common at the site of a lymph node. It appears as a gradually enlarging subcutaneous nodule followed by skin breaks and ulcerations. Tuberculosis verrucosa cutis, also known as warty tuberculosis, is common in developing countries and presents as warty plaque over the hands, knees, and buttocks.14 Tuberculids are skin reactions to systemic tuberculosis infection.

Herpes simplex virus

Mucocutaneous manifestations of herpes simplex virus affect the oral cavity (gingivostomatitis, pharyngitis, and lip border lesions), the entire integumentary system, the eyes (HSV-1), and the genital region (HSV-2). The classic presentation is systemic symptoms (fever and malaise) associated with multiple vesicles on an erythematous base in a distinct region of skin. The virus can remain latent with reactivation occurring because of illness, immunosuppression, or stress. Pruritus and pain precede the appearance of these lesions.

Cytomegalovirus

Primary cytomegalovirus infection is subclinical in almost all cases unless the patient is immunocompromised, and it presents similarly to mononucleosis induced by Epstein-Barr virus. The skin manifestations are nonspecific and can include macular, maculopapular, morbilliform, and urticarial rashes, but usually not ulcerations.15

OUR PATIENT: BEHÇET DISEASE OR CROHN DISEASE?

In our patient, oral mucosal aphthous ulcers and the location of pustular skin lesions, in addition to pathergy, were highly suggestive of Behçet disease. However, Crohn disease with mucocutaneous manifestations remained in the differential diagnosis.

Because there is significant overlap between these diseases, it is important to know the key distinguishing features. Oral aphthous ulcers, pathergy, uveitis, skin and genital lesions, and neurologic involvement are much more common in Behçet disease than in Crohn disease.16,17 Demographic information was not helpful in this case, given that the patient was adopted.

FURTHER WORKUP

2. What should be the next step in the work-up?

- CT enterography

- Skin biopsy

- Colonoscopy with biopsy

- C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and fecal calprotecting testing

The endoscopic appearance and histopathology of the affected tissues are crucial for the diagnosis. Differentiating between Crohn disease and Behçet disease can be particularly challenging because of significant overlap between the intestinal and extraintestinal manifestations of the two diseases, especially the oral lesions and arthralgias. Thus, both colonoscopy with biopsy of the intestinal lesions and biopsy of a cutaneous ulceration should be pursued.

No single test or feature is pathognomonic for Behçet disease. Although many diagnostic criteria have been established, those of the International Study Group (Table 2) are the most widely used.18 Their sensitivity for Behçet disease has been found to be 92%, and their specificity 97%.19

Both CT enterography and inflammatory markers would depict inflammation, but since this is present in both Crohn disease and Behçet disease, these tests would not be helpful in this situation.

Endoscopic appearance of Crohn disease and Behçet disease

Intestinal Behçet disease, like Crohn disease, is an inflammatory bowel disease occurring throughout the gastrointestinal tract (small and large bowel). Both are chronic diseases with a waxing and waning course and have similar extraintestinal manifestations. Typical endoscopic lesions are deep, sharply demarcated (“punched-out”), round ulcers. The intestinal Behçet disease and Crohn disease ulcer phenotype and distribution can look the same, and in both entities, rectal sparing and “skip lesions” have been described.20–22

Nevertheless, findings on endoscopy have been analyzed to try to differentiate between Crohn disease and Behçet disease.

In 2009, Lee et al23 published a simple and accurate strategy for distinguishing the two diseases endoscopically. The authors reviewed 250 patients (115 with Behçet disease, 135 with Crohn disease) with ulcers on colonoscopy and identified 5 endoscopic findings indicative of intestinal Behçet disease:

- Round ulcers

- Focal single or focal multiple distribution of ulcers

- Fewer than 6 ulcers

- Absence of a “cobblestone” appearance

- Absence of aphthous lesions.

The two most accurate factors were absence of a cobblestone appearance (sensitivity 100%) and round ulcer shape (specificity 97.5 %). When more than one factor was present, specificity increased but sensitivity decreased.

Using a classification and regression tree analysis, the investigators created an algorithm that endoscopically differentiates between Crohn disease and Behçet disease (Figure 1) with an accuracy of 92 %.23

Histopathologic analysis of both colonic and skin lesions can provide additional clues to the correct diagnosis. Vasculitis suggests Behçet disease, whereas granulomas suggest Crohn disease.

CASE CONTINUED: SKIN BIOPSY AND COLONOSCOPY

Punch biopsy of the skin was performed on the right anterior thigh. Histopathologic analysis revealed acanthotic epidermis, a discrete full-thickness necrotic ulcer with a neutrophilic base, granulation tissue, and vasculitic changes. There were no vasculitic changes or granulomas outside the ulcer base. Cytomegalovirus staining was negative. An interferon-gamma release assay for tuberculosis was negative. Eye examination results were normal.

Colonoscopy showed multiple deep, round, and confluent ulcers with a punched-out appearance and fissures with normal intervening mucosa in the entire examined colon (Figure 2). The terminal ileal mucosa was normal. Colonic biopsies were consistent with cryptitis and rare crypt abscesses. Vasculitis was not identified.

Although the histologic changes were nonspecific, at this point we considered Behçet disease to be more likely than Crohn disease, given the typical endoscopic appearance and skin changes.

TREATING INTESTINAL BEHÇET DISEASE

3. Which is not considered a standard treatment for intestinal Behçet disease?

- Mesalamine (5-ASA)

- Corticosteroids

- Immunosuppressants

- Mycophenolate mofetil

- Surgery

Overall, data on the management of intestinal Behçet disease are limited. The data that do exist have shown that 5-ASA, corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, and surgery are options, but not mycophenolate mofetil.

Consensus recommendations from the Japanese IBD Research Group,24 published in 2007, included 5-ASA, corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, enteral and total parenteral nutrition, and surgical resection. In 2014, the group published a second consensus statement, adding anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents as standard therapy for this disease.22

Mycophenolate mofetil has not been shown to be effective in the treatment of mucocutaneous Behçet disease,25 although it may be effective in the treatment of its neurologic manifestations.26 Data regarding its efficacy in intestinal Behçet disease are sparse.

Differences in treatment for Crohn and Behçet disease

Although the treatment options are comparable for Behçet disease and Crohn disease, certain features differ.

Doses of 5-ASA and immunnosuppressive agents are typically higher in Crohn disease. For example, the optimal dose of 5-ASA is up to 3 g/day for Behçet disease but up to 4.8 g/day for Crohn disease.

Standard dosing for azathioprine is 50 to 100 mg/day for Behçet disease but 2 to 2.5 mg/kg/day (eg, 168 to 210 mg/day for a 185-lb patient) for Crohn disease.

In addition, evidence supporting the use of biologic agents such as anti-TNF agents or vedolizumab is more abundant in Crohn disease.

Finally, data on monitoring drug levels of immunomodulators or biologics are available only for patients with Crohn disease, not Behçet disease. Thus, an accurate diagnosis is important.

CASE CONTINUED: EMERGENCY LAPAROTOMY

Our patient continued to experience abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea despite receiving corticosteroids intravenously in high doses. We were also considering anti-TNF therapy.

At this point, CT of her abdomen and pelvis was repeated and showed free intraperitoneal air consistent with a perforation of the transverse colon.

She underwent emergency exploratory laparotomy. Intraoperative findings included pneumoperitoneum but no gross peritoneal contamination, extensive colitis with a contained splenic flexure perforation, and normal small-bowel features without evidence of enteritis. Subtotal colectomy, implantation of the rectal stump into the subcutaneous tissue, and end-ileostomy were performed.

After 23 days of recovery in the hospital, she was discharged on oral antibiotics and 4 weeks of steroid taper.

PROGNOSIS OF INTESTINAL BEHÇET DISEASE

4. What can the patient expect from her intestinal Behçet disease in the future?

- The disease is cured after resection of the diseased segments

- Behçet disease is a progressive lifelong disorder that can recur after surgery

Like Crohn disease, Behçet disease should be considered a lifelong progressive disorder, even after surgical resection of diseased segments.

It is unclear which patients will have a complicated disease course and need treatment with stronger immunosuppression. In patients with intestinal Behçet disease whose disease is in remission on thiopurine therapy, the 1-year relapse rate has been reported as 5.8%, and the 5-year relapse rate 51.7%.27,28 After surgical resection, the 5-year recurrence rate was 47.2%, and 30.6% of patients needed repeat surgery.29 Predictors of poor prognosis were younger age, higher erythrocyte sedimentation rate, higher C-reactive protein level, low albumin level at diagnosis, and a high disease-activity index for intestinal Behçet disease.30

The Korean IBD Study Group has developed and validated a disease activity index for intestinal Behçet disease.28 The index has a list of weighted scores for 8 symptoms, which provides for a more objective assessment of disease activity for determining the best treatment approach.

CASE CONTINUED

The patient has continued with her follow-up care and appointments in gastroenterology, rheumatology, and dermatology clinics. She still complains of intermittent abdominal pain, occasional bleeding at the rectal stump, intermittent skin lesions mainly in the form of pustular lesions, and intermittent joint pain. If symptoms persist, anti-TNF therapy is an option.

A 32-year-old woman presented to our emergency department with chest pain and painful ulcerations on her arms, abdomen, back, groin, axillae, and in her mouth. She first noticed the ulcers 7 days earlier.

She also reported bloody diarrhea, which had started 2 years earlier, with 10 or more bowel movements daily. She described her stools as semiformed and associated with urgency and painful abdominal cramps.

Medical history

Her medical history included obstructive sleep apnea and morbid obesity. She had first presented 2 years earlier to another hospital with diarrhea, abdominal pain, and rectal bleeding. At that time, results of esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy were reported as normal. Later, she became pregnant, and her symptoms went away. She had a normal pregnancy and delivery.

About 1 year postpartum, her abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea recurred. Colonoscopy showed severe sigmoid inflammation with small, shallow ulcerations and friable mucosa interrupted by areas of normal mucosa. Histopathologic study of the colonic mucosa indicated mild to moderate chronic active colitis consisting of focal areas of cryptitis with occasional crypt abscess formation. She was diagnosed with Crohn colitis based on the endoscopic appearance, histopathology, and clinical presentation. The endoscope, however, could not be advanced beyond the sigmoid colon, which suggested stenosis. She was started on 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) but developed visual hallucinations, and the medication was stopped.

Her symptoms continued, and she developed worsening rectal bleeding and anemia that required hospitalization and blood transfusions. Another colonoscopy performed 1 month before this emergency department visit had shown multiple mucosal ulcerations, but again, the colonoscope could not be advanced beyond the sigmoid colon. She was started on oral corticosteroids, which provided only minimal clinical improvement.

Her current medications included atenolol (for sinus tachycardia), prednisone (initial dose 60 mg/day tapered to 20 mg/day at presentation), and ciprofloxacin.

Her family history was unknown because she had been adopted.

About 1 week before presentation, she had noticed ulcers developing on her arms, abdomen, back, groin, oral mucosa, and axillae. The ulcers were large and painful, with occasional spontaneous bleeding. She also reported pustules and ulcerations at sites of previous skin punctures, consistent with pathergy.

Findings on presentation

- Temperature 99.5°F (37.5°C)

- Heart rate 124 beats per minute

- Respiratory rate 22 breaths per minute

- Oxygen saturation 100% on room air

- Blood pressure 128/81 mm Hg

- Body mass index 67 kg/m2 (morbidly obese).

She had multiple greyish-white patches and erosions over the soft palate, tongue, and upper and lower lip mucosa, erythematous pustules in the axillae bilaterally, and large erythematous, sharply demarcated ulcerations with a fibrinous base bilaterally covering her arms, thighs, groin, and abdomen.

Blood testing showed multiple abnormal results (Table 1). Urinalysis revealed a urine protein concentration of 100 mg/dL (reference range 0), more than 25 white blood cells per high-power field (reference range < 5), 6 to 10 red blood cells per high-power field (0–3), and more than 10 casts per low-power field (0), which suggested a urinary tract infection with hematuria.

Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous and oral contrast showed diffuse fatty infiltration of the liver and wall thickening of the rectum and sigmoid colon.

She was admitted to the medical intensive care unit for potential septic shock. Intravenous vancomycin and ciprofloxacin were started (the latter owing to penicillin allergy).

CAUSES OF DIARRHEA AND SKIN CHANGES

1. What is the most likely diagnosis in our patient?

- Ulcerative colitis

- Crohn disease

- Behçet disease

- Intestinal tuberculosis

- Herpes simplex virus infection

- Cytomegalovirus infection

All of the above can cause diarrhea in combination with mucocutaneous lesions and other manifestations.

Ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease: Mucocutaneous findings

Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel diseases (Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis, and Behçet disease) include arthritis, ocular involvement, mucocutaneous manifestations, and liver involvement in the form of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Less common extraintestinal manifestations include vascular, renal, pulmonary, cardiac, and neurologic involvement.

Mucocutaneous findings are observed in 5% to 10% of patients with ulcerative colitis and 20% to 75% of patients with Crohn disease.1–3 The most common are erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum.4

Yüksel et al5 reported that of 352 patients with inflammatory bowel disease, 7.4% had erythema nodosum and 2.3% had pyoderma gangrenosum. Erythema nodosum was significantly more common in patients with Crohn disease than in those with ulcerative colitis, and its severity was linked with higher disease activity. Lesions frequently resolved when bowel disease subsided.

Lebwohl and Lebwohl6 reported that pyoderma gangrenosum occurred in up to 20% of patients with Crohn disease and up to 10% of those with ulcerative colitis. It is not known whether pyoderma gangrenosum correlates with intestinal disease severity.

Other mucocutaneous manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease include oral aphthous ulcers, acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet syndrome), and metastatic Crohn disease. Aphthous ulcers in the oral cavity, often observed in both Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis, cannot be differentiated on clinical examination from herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1-induced or idiopathic mucous membrane ulcers. The most common ulcer locations are the lips and buccal mucosa. If biopsied (seldom required), noncaseating granulomas can be identified that are comparable with intestinal mucosal granulomas found in Crohn disease.7

Behçet disease has similar signs

Oral aphthous ulcers are also the most frequent symptom in Behçet disease, occurring in 97% to 100% of cases.8 They most commonly affect the tongue, lips, buccal mucosa, and gingiva.

Cutaneous manifestations include erythema nodosum-like lesions, which present as erythematous painful nodules over pretibial surfaces of the lower limbs but can also affect the arms and thighs; they can also present as papulopustular rosacea eruptions composed of papules, pustules, and noninflammatory comedones, most commonly on the chest, back, and shoulders.8,9

Pathergy, ie, skin hyperresponse to minor trauma such as a bump or bruise, is a typical trait of Behçet disease. A positive pathergy test (ie, skin hyperreactivity to a needlestick or intracutaneous injection) has a specificity of 98.4% in patients with Behçet disease.10

Interestingly, there appears to be a regional difference in the susceptibility to pathergy. While a pathergy response in patients with Behçet disease is rare in the United States and the United Kingdom, it is very common in Japan, Turkey, and Israel.11

Patient demographics also distinguish Behçet disease from Crohn disease. The prevalence of Behçet disease is highest along the Silk Road from the Mediterranean Basin to East Asia and lowest in North America and Northern Europe.12 The mean age at onset is around the third and fourth decades. In males, the prevalence is highest in Mediterranean, Middle Eastern, and Asian countries. In females, the prevalence is highest in the United States, Northern Europe, and East Asia.10

Tuberculosis

Tubercular skin lesions can present in different forms.13 Lupus vulgaris, the most common, occurs after primary infection and presents as translucent brown nodules, mainly over the face and neck. So-called scrofuloderma is common at the site of a lymph node. It appears as a gradually enlarging subcutaneous nodule followed by skin breaks and ulcerations. Tuberculosis verrucosa cutis, also known as warty tuberculosis, is common in developing countries and presents as warty plaque over the hands, knees, and buttocks.14 Tuberculids are skin reactions to systemic tuberculosis infection.

Herpes simplex virus

Mucocutaneous manifestations of herpes simplex virus affect the oral cavity (gingivostomatitis, pharyngitis, and lip border lesions), the entire integumentary system, the eyes (HSV-1), and the genital region (HSV-2). The classic presentation is systemic symptoms (fever and malaise) associated with multiple vesicles on an erythematous base in a distinct region of skin. The virus can remain latent with reactivation occurring because of illness, immunosuppression, or stress. Pruritus and pain precede the appearance of these lesions.

Cytomegalovirus

Primary cytomegalovirus infection is subclinical in almost all cases unless the patient is immunocompromised, and it presents similarly to mononucleosis induced by Epstein-Barr virus. The skin manifestations are nonspecific and can include macular, maculopapular, morbilliform, and urticarial rashes, but usually not ulcerations.15

OUR PATIENT: BEHÇET DISEASE OR CROHN DISEASE?

In our patient, oral mucosal aphthous ulcers and the location of pustular skin lesions, in addition to pathergy, were highly suggestive of Behçet disease. However, Crohn disease with mucocutaneous manifestations remained in the differential diagnosis.

Because there is significant overlap between these diseases, it is important to know the key distinguishing features. Oral aphthous ulcers, pathergy, uveitis, skin and genital lesions, and neurologic involvement are much more common in Behçet disease than in Crohn disease.16,17 Demographic information was not helpful in this case, given that the patient was adopted.

FURTHER WORKUP

2. What should be the next step in the work-up?

- CT enterography

- Skin biopsy

- Colonoscopy with biopsy

- C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and fecal calprotecting testing

The endoscopic appearance and histopathology of the affected tissues are crucial for the diagnosis. Differentiating between Crohn disease and Behçet disease can be particularly challenging because of significant overlap between the intestinal and extraintestinal manifestations of the two diseases, especially the oral lesions and arthralgias. Thus, both colonoscopy with biopsy of the intestinal lesions and biopsy of a cutaneous ulceration should be pursued.

No single test or feature is pathognomonic for Behçet disease. Although many diagnostic criteria have been established, those of the International Study Group (Table 2) are the most widely used.18 Their sensitivity for Behçet disease has been found to be 92%, and their specificity 97%.19

Both CT enterography and inflammatory markers would depict inflammation, but since this is present in both Crohn disease and Behçet disease, these tests would not be helpful in this situation.

Endoscopic appearance of Crohn disease and Behçet disease

Intestinal Behçet disease, like Crohn disease, is an inflammatory bowel disease occurring throughout the gastrointestinal tract (small and large bowel). Both are chronic diseases with a waxing and waning course and have similar extraintestinal manifestations. Typical endoscopic lesions are deep, sharply demarcated (“punched-out”), round ulcers. The intestinal Behçet disease and Crohn disease ulcer phenotype and distribution can look the same, and in both entities, rectal sparing and “skip lesions” have been described.20–22

Nevertheless, findings on endoscopy have been analyzed to try to differentiate between Crohn disease and Behçet disease.

In 2009, Lee et al23 published a simple and accurate strategy for distinguishing the two diseases endoscopically. The authors reviewed 250 patients (115 with Behçet disease, 135 with Crohn disease) with ulcers on colonoscopy and identified 5 endoscopic findings indicative of intestinal Behçet disease:

- Round ulcers

- Focal single or focal multiple distribution of ulcers

- Fewer than 6 ulcers

- Absence of a “cobblestone” appearance

- Absence of aphthous lesions.

The two most accurate factors were absence of a cobblestone appearance (sensitivity 100%) and round ulcer shape (specificity 97.5 %). When more than one factor was present, specificity increased but sensitivity decreased.

Using a classification and regression tree analysis, the investigators created an algorithm that endoscopically differentiates between Crohn disease and Behçet disease (Figure 1) with an accuracy of 92 %.23

Histopathologic analysis of both colonic and skin lesions can provide additional clues to the correct diagnosis. Vasculitis suggests Behçet disease, whereas granulomas suggest Crohn disease.

CASE CONTINUED: SKIN BIOPSY AND COLONOSCOPY

Punch biopsy of the skin was performed on the right anterior thigh. Histopathologic analysis revealed acanthotic epidermis, a discrete full-thickness necrotic ulcer with a neutrophilic base, granulation tissue, and vasculitic changes. There were no vasculitic changes or granulomas outside the ulcer base. Cytomegalovirus staining was negative. An interferon-gamma release assay for tuberculosis was negative. Eye examination results were normal.

Colonoscopy showed multiple deep, round, and confluent ulcers with a punched-out appearance and fissures with normal intervening mucosa in the entire examined colon (Figure 2). The terminal ileal mucosa was normal. Colonic biopsies were consistent with cryptitis and rare crypt abscesses. Vasculitis was not identified.

Although the histologic changes were nonspecific, at this point we considered Behçet disease to be more likely than Crohn disease, given the typical endoscopic appearance and skin changes.

TREATING INTESTINAL BEHÇET DISEASE

3. Which is not considered a standard treatment for intestinal Behçet disease?

- Mesalamine (5-ASA)

- Corticosteroids

- Immunosuppressants

- Mycophenolate mofetil

- Surgery

Overall, data on the management of intestinal Behçet disease are limited. The data that do exist have shown that 5-ASA, corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, and surgery are options, but not mycophenolate mofetil.

Consensus recommendations from the Japanese IBD Research Group,24 published in 2007, included 5-ASA, corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, enteral and total parenteral nutrition, and surgical resection. In 2014, the group published a second consensus statement, adding anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents as standard therapy for this disease.22

Mycophenolate mofetil has not been shown to be effective in the treatment of mucocutaneous Behçet disease,25 although it may be effective in the treatment of its neurologic manifestations.26 Data regarding its efficacy in intestinal Behçet disease are sparse.

Differences in treatment for Crohn and Behçet disease

Although the treatment options are comparable for Behçet disease and Crohn disease, certain features differ.

Doses of 5-ASA and immunnosuppressive agents are typically higher in Crohn disease. For example, the optimal dose of 5-ASA is up to 3 g/day for Behçet disease but up to 4.8 g/day for Crohn disease.

Standard dosing for azathioprine is 50 to 100 mg/day for Behçet disease but 2 to 2.5 mg/kg/day (eg, 168 to 210 mg/day for a 185-lb patient) for Crohn disease.

In addition, evidence supporting the use of biologic agents such as anti-TNF agents or vedolizumab is more abundant in Crohn disease.

Finally, data on monitoring drug levels of immunomodulators or biologics are available only for patients with Crohn disease, not Behçet disease. Thus, an accurate diagnosis is important.

CASE CONTINUED: EMERGENCY LAPAROTOMY

Our patient continued to experience abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea despite receiving corticosteroids intravenously in high doses. We were also considering anti-TNF therapy.

At this point, CT of her abdomen and pelvis was repeated and showed free intraperitoneal air consistent with a perforation of the transverse colon.

She underwent emergency exploratory laparotomy. Intraoperative findings included pneumoperitoneum but no gross peritoneal contamination, extensive colitis with a contained splenic flexure perforation, and normal small-bowel features without evidence of enteritis. Subtotal colectomy, implantation of the rectal stump into the subcutaneous tissue, and end-ileostomy were performed.

After 23 days of recovery in the hospital, she was discharged on oral antibiotics and 4 weeks of steroid taper.

PROGNOSIS OF INTESTINAL BEHÇET DISEASE

4. What can the patient expect from her intestinal Behçet disease in the future?

- The disease is cured after resection of the diseased segments

- Behçet disease is a progressive lifelong disorder that can recur after surgery

Like Crohn disease, Behçet disease should be considered a lifelong progressive disorder, even after surgical resection of diseased segments.

It is unclear which patients will have a complicated disease course and need treatment with stronger immunosuppression. In patients with intestinal Behçet disease whose disease is in remission on thiopurine therapy, the 1-year relapse rate has been reported as 5.8%, and the 5-year relapse rate 51.7%.27,28 After surgical resection, the 5-year recurrence rate was 47.2%, and 30.6% of patients needed repeat surgery.29 Predictors of poor prognosis were younger age, higher erythrocyte sedimentation rate, higher C-reactive protein level, low albumin level at diagnosis, and a high disease-activity index for intestinal Behçet disease.30

The Korean IBD Study Group has developed and validated a disease activity index for intestinal Behçet disease.28 The index has a list of weighted scores for 8 symptoms, which provides for a more objective assessment of disease activity for determining the best treatment approach.

CASE CONTINUED

The patient has continued with her follow-up care and appointments in gastroenterology, rheumatology, and dermatology clinics. She still complains of intermittent abdominal pain, occasional bleeding at the rectal stump, intermittent skin lesions mainly in the form of pustular lesions, and intermittent joint pain. If symptoms persist, anti-TNF therapy is an option.

- Burgdorf W. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn’s disease. J Am Acad Dermatol 1981; 5:689–695.

- Palamaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: a review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2008; 22:1033–1043.

- Timani S, Mutasim DF. Skin manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Dermatol 2008; 26:265–273.

- Tavarela Veloso F. Skin complications associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004; 20(suppl 4):50–53.

- Yüksel I, Basar O, Ataseven H, et al. Mucocutaneous manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2009; 15:546–550.

- Lebwohl M, Lebwohl O. Cutaneous manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 1998; 4:142–148.

- Levine JS, Burakoff R. Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY) 2011; 7:235–241.

- Mat C, Yurdakul S, Sevim A, Özyazgan Y, Tüzün Y. Behçet’s syndrome: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol 2013; 31:352–361.

- Lee ES, Bangz D, Lee S. Dermatologic manifestation of Behçet’s disease. Yonsei Med J 1997; 38:380–389.

- Davatchi F, Chams-Davatchi C, Ghodsi Z, et al. Diagnostic value of pathergy test in Behçet’s disease according to the change of incidence over the time. Clin Rheumatol 2011; 30:1151–1155.

- Friedman-Birnbaum R, Bergman R, Aizen E. Sensitivity and specificity of pathergy test results in Israeli patients with Behçet’s disease. Cutis 1990; 45:261–264.

- Mahr A, Maldini C. Epidemiology of Behçet’s disease. Rev Med Interne 2014; 35:81–89. French.

- Barbagallo J, Tager P, Ingleton R, Hirsch RJ, Weinberg JM. Cutaneous tuberculosis. Am J Clin Dermatol 2002; 3:319–328.

- Padmavathy L, Lakshmana Rao L, Ethirajan N, Ramakrishna Rao M, Subrahmanyan EN, Manohar U. Tuberculosis verrucosa cutis (TBVC)—foot with miliary tuberculosis. Indian J Tuberc 2007; 54:145–148.

- Drago F, Aragone MG, Lugani C, Rebora A. Cytomegalovirus infection in normal and immunocompromised humans. A review. Dermatology 2000; 200:189–195.

- Yazısız V. Similarities and differences between Behçet’s disease and Crohn’s disease. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol 2014; 5:228–238.

- Chin AB, Kumar AS. Behçet colitis. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2015; 28:99–102.

- International Study Group for Behçet’s Disease. Criteria for diagnosis of Behçet’s disease. Lancet 1990; 335:1078–1080.

- Davatchi F. Diagnosis/classification criteria for Behcet’s disease. Patholog Res Int 2012; 2012:607921.

- Chang DK, Kim JJ, Choi H, et al. Double balloon endoscopy in small intestinal Crohn’s disease and other inflammatory diseases such as cryptogenic multifocal ulcerous stenosing enteritis (CMUSE). Gastrointest Endosc 2007; 66(suppl):S96–S98.

- Hamdulay SS, Cheent K, Ghosh C, Stocks J, Ghosh S, Haskard DO. Wireless capsule endoscopy in the investigation of intestinal Behçet’s syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008; 47:1231–1234.

- Hisamatsu T, Ueno F, Matsumoto T, et al. The 2nd edition of consensus statements for the diagnosis and management of intestinal Behçet’s disease: indication of anti-TNFa monoclonal antibodies. J Gastroenterol 2014; 49:156–162.

- Lee SK, Kim BK, Kim TI, Kim WH. Differential diagnosis of intestinal Behçet’s disease and Crohn’s disease by colonoscopic findings. Endoscopy 2009; 41:9–16.

- Kobayashi K, Ueno F, Bito S, et al. Development of consensus statements for the diagnosis and management of intestinal Behçet’s disease using a modified Delphi approach. J Gastroenterol 2007; 42:737–745.

- Adler YD, Mansmann U, Zouboulis CC. Mycophenolate mofetil is ineffective in the treatment of mucocutaneous Adamantiades-Behçet’s disease. Dermatology 2001; 203:322–324.

- Shugaiv E, Tüzün E, Mutlu M, Kiyat-Atamer A, Kurtuncu M, Akman-Demir G. Mycophenolate mofetil as a novel immunosuppressant in the treatment of neuro-Behçet’s disease with parenchymal involvement: presentation of four cases. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2011; 29(suppl 67):S64–S67.

- Jung YS, Cheon JH, Hong SP, Kim TI, Kim WH. Clinical outcomes and prognostic factors for thiopurine maintenance therapy in patients with intestinal Behçet’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2012; 18:750–757.

- Cheon JH, Han DS, Park JY, et al; Korean IBD Study Group. Development, validation, and responsiveness of a novel disease activity index for intestinal Behçet’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2011; 17:605–613.

- Jung YS, Yoon JY, Lee JH, et al. Prognostic factors and long-term clinical outcomes for surgical patients with intestinal Behçet’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2011; 17:1594–1602.

- Jung YS, Cheon JH, Park SJ, Hong SP, Kim TI, Kim WH. Clinical course of intestinal Behçet’s disease during the first five years. Dig Dis Sci 2013; 58:496–503.

- Burgdorf W. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn’s disease. J Am Acad Dermatol 1981; 5:689–695.

- Palamaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: a review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2008; 22:1033–1043.

- Timani S, Mutasim DF. Skin manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Dermatol 2008; 26:265–273.

- Tavarela Veloso F. Skin complications associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004; 20(suppl 4):50–53.

- Yüksel I, Basar O, Ataseven H, et al. Mucocutaneous manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2009; 15:546–550.

- Lebwohl M, Lebwohl O. Cutaneous manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 1998; 4:142–148.

- Levine JS, Burakoff R. Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY) 2011; 7:235–241.

- Mat C, Yurdakul S, Sevim A, Özyazgan Y, Tüzün Y. Behçet’s syndrome: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol 2013; 31:352–361.

- Lee ES, Bangz D, Lee S. Dermatologic manifestation of Behçet’s disease. Yonsei Med J 1997; 38:380–389.

- Davatchi F, Chams-Davatchi C, Ghodsi Z, et al. Diagnostic value of pathergy test in Behçet’s disease according to the change of incidence over the time. Clin Rheumatol 2011; 30:1151–1155.

- Friedman-Birnbaum R, Bergman R, Aizen E. Sensitivity and specificity of pathergy test results in Israeli patients with Behçet’s disease. Cutis 1990; 45:261–264.

- Mahr A, Maldini C. Epidemiology of Behçet’s disease. Rev Med Interne 2014; 35:81–89. French.

- Barbagallo J, Tager P, Ingleton R, Hirsch RJ, Weinberg JM. Cutaneous tuberculosis. Am J Clin Dermatol 2002; 3:319–328.

- Padmavathy L, Lakshmana Rao L, Ethirajan N, Ramakrishna Rao M, Subrahmanyan EN, Manohar U. Tuberculosis verrucosa cutis (TBVC)—foot with miliary tuberculosis. Indian J Tuberc 2007; 54:145–148.

- Drago F, Aragone MG, Lugani C, Rebora A. Cytomegalovirus infection in normal and immunocompromised humans. A review. Dermatology 2000; 200:189–195.

- Yazısız V. Similarities and differences between Behçet’s disease and Crohn’s disease. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol 2014; 5:228–238.

- Chin AB, Kumar AS. Behçet colitis. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2015; 28:99–102.

- International Study Group for Behçet’s Disease. Criteria for diagnosis of Behçet’s disease. Lancet 1990; 335:1078–1080.

- Davatchi F. Diagnosis/classification criteria for Behcet’s disease. Patholog Res Int 2012; 2012:607921.

- Chang DK, Kim JJ, Choi H, et al. Double balloon endoscopy in small intestinal Crohn’s disease and other inflammatory diseases such as cryptogenic multifocal ulcerous stenosing enteritis (CMUSE). Gastrointest Endosc 2007; 66(suppl):S96–S98.

- Hamdulay SS, Cheent K, Ghosh C, Stocks J, Ghosh S, Haskard DO. Wireless capsule endoscopy in the investigation of intestinal Behçet’s syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008; 47:1231–1234.

- Hisamatsu T, Ueno F, Matsumoto T, et al. The 2nd edition of consensus statements for the diagnosis and management of intestinal Behçet’s disease: indication of anti-TNFa monoclonal antibodies. J Gastroenterol 2014; 49:156–162.

- Lee SK, Kim BK, Kim TI, Kim WH. Differential diagnosis of intestinal Behçet’s disease and Crohn’s disease by colonoscopic findings. Endoscopy 2009; 41:9–16.

- Kobayashi K, Ueno F, Bito S, et al. Development of consensus statements for the diagnosis and management of intestinal Behçet’s disease using a modified Delphi approach. J Gastroenterol 2007; 42:737–745.

- Adler YD, Mansmann U, Zouboulis CC. Mycophenolate mofetil is ineffective in the treatment of mucocutaneous Adamantiades-Behçet’s disease. Dermatology 2001; 203:322–324.

- Shugaiv E, Tüzün E, Mutlu M, Kiyat-Atamer A, Kurtuncu M, Akman-Demir G. Mycophenolate mofetil as a novel immunosuppressant in the treatment of neuro-Behçet’s disease with parenchymal involvement: presentation of four cases. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2011; 29(suppl 67):S64–S67.

- Jung YS, Cheon JH, Hong SP, Kim TI, Kim WH. Clinical outcomes and prognostic factors for thiopurine maintenance therapy in patients with intestinal Behçet’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2012; 18:750–757.

- Cheon JH, Han DS, Park JY, et al; Korean IBD Study Group. Development, validation, and responsiveness of a novel disease activity index for intestinal Behçet’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2011; 17:605–613.

- Jung YS, Yoon JY, Lee JH, et al. Prognostic factors and long-term clinical outcomes for surgical patients with intestinal Behçet’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2011; 17:1594–1602.

- Jung YS, Cheon JH, Park SJ, Hong SP, Kim TI, Kim WH. Clinical course of intestinal Behçet’s disease during the first five years. Dig Dis Sci 2013; 58:496–503.