User login

The traditional clinical trial, designed to test whether a new treatment is better than a placebo or another active treatment, is known as a “superiority” trial—although rarely labeled as such. In contrast, the goal of a noninferiority trial is simply to demonstrate that a new treatment is not substantially less effective than the standard therapy.

Such trials are useful when a new therapy is thought to be safer, easier to administer, or less costly than the existing treatment, but not necessarily more effective. And, because it would be unethical to randomize patients with a serious condition for which there already is an effective treatment to placebo, a noninferiority trial is another means of determining if the new treatment is effective.

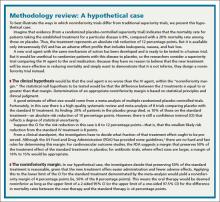

Noninferiority trials have unique design features and methodology and require a different analysis than traditional superiority trials. Yet many physicians know far less about them; many investigators appear to be less than proficient, as well. A review of 116 noninferiority trials and 46 equivalence trials found that only 20% fulfilled generally accepted quality criteria.1 To improve the quality of noninferiority trials, the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) Group has published a checklist for trial design and reporting standards.2,3 Based on this checklist, we came up with 7 key questions to consider when evaluating a noninferiority trial. In the pages that follow, you’ll also find an at-a-glance guide (TABLE) and a methodology review using a hypothetical case (page E7).

1. Is a noninferiority trial appropriate?

The introduction to a noninferiority trial should provide the rationale for this design and the absence of a placebo control group. Look for a review of the evidence of the efficacy of the reference treatment that placebo-controlled trials have revealed, along with the effect size. The advantages of the new treatment over the standard treatment—eg, fewer adverse effects, easier administration, or lower cost—should be discussed, as well.

In the Randomized Evaluation of Long-term Anticoagulation Therapy (RE-LY)—a prominent noninferiority trial—investigators compared the standard anticoagulant (warfarin) for patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) at risk of stroke with a new agent, dabigatran.4 In the methods section of the abstract and the statistical analysis section of the main body, the authors clearly indicated that this was a noninferiority trial. They began by referring to the existing evidence of warfarin’s effectiveness, then detailed the qualities that make warfarin cumbersome to use, including the need for frequent laboratory monitoring. This was followed by evidence that many patients stop taking warfarin and that even for those who persist with treatment, adequate anticoagulation is difficult to maintain.

The authors went on to state that because dabigatran requires no long-term monitoring, it is easier to use. Therefore, if dabigatran could be shown to be no worse than warfarin in preventing strokes, it would be a reasonable alternative, leaving no doubt that this was an appropriate noninferiority trial.

2. Is the noninferiority margin based on clinical judgment and statistical reasoning?

The noninferiority margin should be based on clinical judgment as to how effective a new treatment must be in order to be declared not clinically inferior to the standard treatment. This can be based on several factors, including the severity of the outcome and the expected advantages of the new treatment. The margin should also take into account the size of the standard treatment’s effect vs placebo. In RELY, for example, the authors noted that the noninferiority margin was based on the desire to preserve at least 50% of the lower limit of the confidence interval (CI) of warfarin’s estimated effect; this was done using data from a previously published meta-analysis of 6 trials comparing warfarin with placebo for stroke prevention in patients with AF.4-6

3. Are the hypothesis and statistical analysis formulated correctly?

The clinical hypothesis in a noninferiority trial is that the new treatment is not worse than the standard treatment by a prespecified margin; therefore, the statistical null hypothesis to be tested is that the new treatment is worse than the reference treatment by more than that margin. Rejecting a true null hypothesis (for example, because the P value is <.05) is known as a type l error. In this setting, making a type I error would mean accepting a new treatment that is truly worse than the standard by at least the specified margin. Failure to reject a false null hypothesis is known as a type II error, which in this case would mean failing to identify a new treatment that is truly noninferior to the standard.7

In RE-LY, the authors stated that the upper limit of the one-sided 97.5% CI for the relative risk of a stroke with dabigatran vs warfarin had to fall below 1.46.4 (This is the same as testing the null hypothesis that the hazard ratio is ≥1.46.) Thus, the hypothesis was formulated correctly.

4. Is the sample size appropriate and justified?

The sample size in a noninferiority trial should provide high power to reject the null hypothesis that the difference (or relative risk) between groups is equal to or greater than the noninferiority margin under some clinically meaningful assumption about the true difference (or absolute risk reduction) between groups. A true difference of 0 (or a relative risk of 1) is typically assumed for sample size calculation. However, assuming that the new treatment is truly slightly better or slightly worse than the standard may be clinically appropriate in some cases. This would indicate a need for a smaller or larger sample size, respectively, than that required under the usual assumption of no difference.

When the justification for the sample size in a noninferiority trial is not provided or the number of participants is based on an inappropriate approach (eg, using superiority trial calculations for a noninferiority trial), questions about the quality of the trial arise. The primary concern is whether the noninferiority margin was actually selected before the trial began, as it should have been. And if the researchers used overly optimistic assumptions about the efficacy of the new treatment relative to the standard therapy, the failure to rule out the margin could be misleading. (As with superiority trials that fail to reject the null hypothesis, post hoc power calculations should be avoided.) After the study has ended, the resulting CIs should be used to evaluate whether the study was large enough to adequately assess the relative effectiveness of the treatments.

The RE-LY trial calculated the sample size that was expected to provide 84% power to rule out the prespecified hazard ratio of 1.46, assuming a true event rate of 1.6% per year (presumably for both groups), a recruitment period of 2 years, and at least one year of follow-up. The sample size was subsequently increased from 15,000 to 18,000 to maintain power in case of a low event rate.4,5

5. Is the noninferiority trial as similar as possible to the trial(s) comparing the standard treatment with placebo?

Characteristics of participants, setting, reference treatment, and outcomes used in a noninferiority trial should be as close as possible to those in the trial(s) comparing the treatment with placebo. This is known as the constancy assumption, and it is key to researchers’ ability to draw a conclusion about noninferiority.

The trials used to calculate the noninferiority margin and the RE-LY trial itself involved similar populations of patients with AF, and the outcome (stroke) was similar.

6. Is a per protocol analysis reported in the results?

In randomized controlled superiority trials, the participants should be analyzed in the groups to which they were originally allocated, regardless of whether they adhered to treatment during the entire follow-up period. Such intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis is important because it provides a more conservative estimate of treatment effect—taking into account that some people who are offered treatment will not accept it and others will discontinue treatment. An ITT analysis therefore tends to minimize treatment effects compared with a “per protocol” analysis, in which participants are analyzed according to the treatment they actually received and are often removed from the analysis if they discontinue or do not adhere to treatment.

In noninferiority trials, if patients in the intervention group cross over to the standard treatment group or those in the standard treatment group have poor adherence, an ITT analysis can increase the risk of wrongly claiming noninferiority.7 Therefore, a per protocol analysis should be included—and indeed may be preferable.

In RE-LY, ITT analyses were reported, and complete follow-up data were available for 99.9% of patients. However, the rates of treatment discontinuation at one year were about 15% for those on dabigatran and 10% for the warfarin group, and 21% and 17%, respectively, at 2 years.4,5 If the new treatment were truly less efficacious than the standard treatment, these moderate discontinuation rates could lead to more similar rates of stroke in the 2 groups than would be expected with higher continuation rates, biasing results towards the alternative of noninferiority. Although the original publication of trial results did not include a per protocol analysis, the RE-LY authors later reported that a per protocol analysis yielded similar results to the ITT analysis.

7. Are the overall design and execution of the trial high quality?

Because a poor quality noninferiority trial can appear to demonstrate noninferiority, looking at such studies critically is crucial. Appropriate randomization, concealed allocation, masking, and careful attention to participant flow must all be assessed.2,3

To continue with our example, the RE-LY trial was well conducted. Randomization was performed centrally via an automated telephone system and 2 doses of dabigatran were administered in a masked fashion, while warfarin was open-label. Remarkably, follow-up was achieved for 99.9% of participants over a median of 2 years, and independent adjudicators masked to treatment group assessed outcomes.4,5

CORRESPONDENCE

Anne Mounsey, MD, UNC Chapel Hill Department of Family Medicine, 590 Manning Drive, CB 7595, Chapel Hill, NC 27590; anne_mounsey@med.unc.edu

1. Le Henanff A, Giraudeau B, Baron G, et al. Quality of reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials. JAMA. 2006;295:1147-1151.

2. Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Pocock SJ, et al; CONSORT Group. Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: extension of the CONSORT 2010 statement. JAMA. 2012;308:2594-2604.

3. Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman D; CONSORT Group (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials). The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. JAMA. 2001;285:1987-1991.

4. Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, et al; RE-LY Steering Committee and Investigators. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1139-1151.

5. Ezekowitz MD, Connolly S, Parekh A, et al. Rationale and design of RE-LY: randomized evaluation of long-term anticoagulant therapy, warfarin, compared with dabigatran. Am Heart J. 2009;157:805-810, 810.e1-2.

6. Hart RG, Benavente O, McBride R, et al. Antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:492-501.

7. US Department of Health and Human Services. Guidance for industry non-inferiority clinical trials. US Food and Drug Administration Web site. March 2010. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM202140.pdf. Accessed February 4, 2014.

The traditional clinical trial, designed to test whether a new treatment is better than a placebo or another active treatment, is known as a “superiority” trial—although rarely labeled as such. In contrast, the goal of a noninferiority trial is simply to demonstrate that a new treatment is not substantially less effective than the standard therapy.

Such trials are useful when a new therapy is thought to be safer, easier to administer, or less costly than the existing treatment, but not necessarily more effective. And, because it would be unethical to randomize patients with a serious condition for which there already is an effective treatment to placebo, a noninferiority trial is another means of determining if the new treatment is effective.

Noninferiority trials have unique design features and methodology and require a different analysis than traditional superiority trials. Yet many physicians know far less about them; many investigators appear to be less than proficient, as well. A review of 116 noninferiority trials and 46 equivalence trials found that only 20% fulfilled generally accepted quality criteria.1 To improve the quality of noninferiority trials, the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) Group has published a checklist for trial design and reporting standards.2,3 Based on this checklist, we came up with 7 key questions to consider when evaluating a noninferiority trial. In the pages that follow, you’ll also find an at-a-glance guide (TABLE) and a methodology review using a hypothetical case (page E7).

1. Is a noninferiority trial appropriate?

The introduction to a noninferiority trial should provide the rationale for this design and the absence of a placebo control group. Look for a review of the evidence of the efficacy of the reference treatment that placebo-controlled trials have revealed, along with the effect size. The advantages of the new treatment over the standard treatment—eg, fewer adverse effects, easier administration, or lower cost—should be discussed, as well.

In the Randomized Evaluation of Long-term Anticoagulation Therapy (RE-LY)—a prominent noninferiority trial—investigators compared the standard anticoagulant (warfarin) for patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) at risk of stroke with a new agent, dabigatran.4 In the methods section of the abstract and the statistical analysis section of the main body, the authors clearly indicated that this was a noninferiority trial. They began by referring to the existing evidence of warfarin’s effectiveness, then detailed the qualities that make warfarin cumbersome to use, including the need for frequent laboratory monitoring. This was followed by evidence that many patients stop taking warfarin and that even for those who persist with treatment, adequate anticoagulation is difficult to maintain.

The authors went on to state that because dabigatran requires no long-term monitoring, it is easier to use. Therefore, if dabigatran could be shown to be no worse than warfarin in preventing strokes, it would be a reasonable alternative, leaving no doubt that this was an appropriate noninferiority trial.

2. Is the noninferiority margin based on clinical judgment and statistical reasoning?

The noninferiority margin should be based on clinical judgment as to how effective a new treatment must be in order to be declared not clinically inferior to the standard treatment. This can be based on several factors, including the severity of the outcome and the expected advantages of the new treatment. The margin should also take into account the size of the standard treatment’s effect vs placebo. In RELY, for example, the authors noted that the noninferiority margin was based on the desire to preserve at least 50% of the lower limit of the confidence interval (CI) of warfarin’s estimated effect; this was done using data from a previously published meta-analysis of 6 trials comparing warfarin with placebo for stroke prevention in patients with AF.4-6

3. Are the hypothesis and statistical analysis formulated correctly?

The clinical hypothesis in a noninferiority trial is that the new treatment is not worse than the standard treatment by a prespecified margin; therefore, the statistical null hypothesis to be tested is that the new treatment is worse than the reference treatment by more than that margin. Rejecting a true null hypothesis (for example, because the P value is <.05) is known as a type l error. In this setting, making a type I error would mean accepting a new treatment that is truly worse than the standard by at least the specified margin. Failure to reject a false null hypothesis is known as a type II error, which in this case would mean failing to identify a new treatment that is truly noninferior to the standard.7

In RE-LY, the authors stated that the upper limit of the one-sided 97.5% CI for the relative risk of a stroke with dabigatran vs warfarin had to fall below 1.46.4 (This is the same as testing the null hypothesis that the hazard ratio is ≥1.46.) Thus, the hypothesis was formulated correctly.

4. Is the sample size appropriate and justified?

The sample size in a noninferiority trial should provide high power to reject the null hypothesis that the difference (or relative risk) between groups is equal to or greater than the noninferiority margin under some clinically meaningful assumption about the true difference (or absolute risk reduction) between groups. A true difference of 0 (or a relative risk of 1) is typically assumed for sample size calculation. However, assuming that the new treatment is truly slightly better or slightly worse than the standard may be clinically appropriate in some cases. This would indicate a need for a smaller or larger sample size, respectively, than that required under the usual assumption of no difference.

When the justification for the sample size in a noninferiority trial is not provided or the number of participants is based on an inappropriate approach (eg, using superiority trial calculations for a noninferiority trial), questions about the quality of the trial arise. The primary concern is whether the noninferiority margin was actually selected before the trial began, as it should have been. And if the researchers used overly optimistic assumptions about the efficacy of the new treatment relative to the standard therapy, the failure to rule out the margin could be misleading. (As with superiority trials that fail to reject the null hypothesis, post hoc power calculations should be avoided.) After the study has ended, the resulting CIs should be used to evaluate whether the study was large enough to adequately assess the relative effectiveness of the treatments.

The RE-LY trial calculated the sample size that was expected to provide 84% power to rule out the prespecified hazard ratio of 1.46, assuming a true event rate of 1.6% per year (presumably for both groups), a recruitment period of 2 years, and at least one year of follow-up. The sample size was subsequently increased from 15,000 to 18,000 to maintain power in case of a low event rate.4,5

5. Is the noninferiority trial as similar as possible to the trial(s) comparing the standard treatment with placebo?

Characteristics of participants, setting, reference treatment, and outcomes used in a noninferiority trial should be as close as possible to those in the trial(s) comparing the treatment with placebo. This is known as the constancy assumption, and it is key to researchers’ ability to draw a conclusion about noninferiority.

The trials used to calculate the noninferiority margin and the RE-LY trial itself involved similar populations of patients with AF, and the outcome (stroke) was similar.

6. Is a per protocol analysis reported in the results?

In randomized controlled superiority trials, the participants should be analyzed in the groups to which they were originally allocated, regardless of whether they adhered to treatment during the entire follow-up period. Such intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis is important because it provides a more conservative estimate of treatment effect—taking into account that some people who are offered treatment will not accept it and others will discontinue treatment. An ITT analysis therefore tends to minimize treatment effects compared with a “per protocol” analysis, in which participants are analyzed according to the treatment they actually received and are often removed from the analysis if they discontinue or do not adhere to treatment.

In noninferiority trials, if patients in the intervention group cross over to the standard treatment group or those in the standard treatment group have poor adherence, an ITT analysis can increase the risk of wrongly claiming noninferiority.7 Therefore, a per protocol analysis should be included—and indeed may be preferable.

In RE-LY, ITT analyses were reported, and complete follow-up data were available for 99.9% of patients. However, the rates of treatment discontinuation at one year were about 15% for those on dabigatran and 10% for the warfarin group, and 21% and 17%, respectively, at 2 years.4,5 If the new treatment were truly less efficacious than the standard treatment, these moderate discontinuation rates could lead to more similar rates of stroke in the 2 groups than would be expected with higher continuation rates, biasing results towards the alternative of noninferiority. Although the original publication of trial results did not include a per protocol analysis, the RE-LY authors later reported that a per protocol analysis yielded similar results to the ITT analysis.

7. Are the overall design and execution of the trial high quality?

Because a poor quality noninferiority trial can appear to demonstrate noninferiority, looking at such studies critically is crucial. Appropriate randomization, concealed allocation, masking, and careful attention to participant flow must all be assessed.2,3

To continue with our example, the RE-LY trial was well conducted. Randomization was performed centrally via an automated telephone system and 2 doses of dabigatran were administered in a masked fashion, while warfarin was open-label. Remarkably, follow-up was achieved for 99.9% of participants over a median of 2 years, and independent adjudicators masked to treatment group assessed outcomes.4,5

CORRESPONDENCE

Anne Mounsey, MD, UNC Chapel Hill Department of Family Medicine, 590 Manning Drive, CB 7595, Chapel Hill, NC 27590; anne_mounsey@med.unc.edu

The traditional clinical trial, designed to test whether a new treatment is better than a placebo or another active treatment, is known as a “superiority” trial—although rarely labeled as such. In contrast, the goal of a noninferiority trial is simply to demonstrate that a new treatment is not substantially less effective than the standard therapy.

Such trials are useful when a new therapy is thought to be safer, easier to administer, or less costly than the existing treatment, but not necessarily more effective. And, because it would be unethical to randomize patients with a serious condition for which there already is an effective treatment to placebo, a noninferiority trial is another means of determining if the new treatment is effective.

Noninferiority trials have unique design features and methodology and require a different analysis than traditional superiority trials. Yet many physicians know far less about them; many investigators appear to be less than proficient, as well. A review of 116 noninferiority trials and 46 equivalence trials found that only 20% fulfilled generally accepted quality criteria.1 To improve the quality of noninferiority trials, the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) Group has published a checklist for trial design and reporting standards.2,3 Based on this checklist, we came up with 7 key questions to consider when evaluating a noninferiority trial. In the pages that follow, you’ll also find an at-a-glance guide (TABLE) and a methodology review using a hypothetical case (page E7).

1. Is a noninferiority trial appropriate?

The introduction to a noninferiority trial should provide the rationale for this design and the absence of a placebo control group. Look for a review of the evidence of the efficacy of the reference treatment that placebo-controlled trials have revealed, along with the effect size. The advantages of the new treatment over the standard treatment—eg, fewer adverse effects, easier administration, or lower cost—should be discussed, as well.

In the Randomized Evaluation of Long-term Anticoagulation Therapy (RE-LY)—a prominent noninferiority trial—investigators compared the standard anticoagulant (warfarin) for patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) at risk of stroke with a new agent, dabigatran.4 In the methods section of the abstract and the statistical analysis section of the main body, the authors clearly indicated that this was a noninferiority trial. They began by referring to the existing evidence of warfarin’s effectiveness, then detailed the qualities that make warfarin cumbersome to use, including the need for frequent laboratory monitoring. This was followed by evidence that many patients stop taking warfarin and that even for those who persist with treatment, adequate anticoagulation is difficult to maintain.

The authors went on to state that because dabigatran requires no long-term monitoring, it is easier to use. Therefore, if dabigatran could be shown to be no worse than warfarin in preventing strokes, it would be a reasonable alternative, leaving no doubt that this was an appropriate noninferiority trial.

2. Is the noninferiority margin based on clinical judgment and statistical reasoning?

The noninferiority margin should be based on clinical judgment as to how effective a new treatment must be in order to be declared not clinically inferior to the standard treatment. This can be based on several factors, including the severity of the outcome and the expected advantages of the new treatment. The margin should also take into account the size of the standard treatment’s effect vs placebo. In RELY, for example, the authors noted that the noninferiority margin was based on the desire to preserve at least 50% of the lower limit of the confidence interval (CI) of warfarin’s estimated effect; this was done using data from a previously published meta-analysis of 6 trials comparing warfarin with placebo for stroke prevention in patients with AF.4-6

3. Are the hypothesis and statistical analysis formulated correctly?

The clinical hypothesis in a noninferiority trial is that the new treatment is not worse than the standard treatment by a prespecified margin; therefore, the statistical null hypothesis to be tested is that the new treatment is worse than the reference treatment by more than that margin. Rejecting a true null hypothesis (for example, because the P value is <.05) is known as a type l error. In this setting, making a type I error would mean accepting a new treatment that is truly worse than the standard by at least the specified margin. Failure to reject a false null hypothesis is known as a type II error, which in this case would mean failing to identify a new treatment that is truly noninferior to the standard.7

In RE-LY, the authors stated that the upper limit of the one-sided 97.5% CI for the relative risk of a stroke with dabigatran vs warfarin had to fall below 1.46.4 (This is the same as testing the null hypothesis that the hazard ratio is ≥1.46.) Thus, the hypothesis was formulated correctly.

4. Is the sample size appropriate and justified?

The sample size in a noninferiority trial should provide high power to reject the null hypothesis that the difference (or relative risk) between groups is equal to or greater than the noninferiority margin under some clinically meaningful assumption about the true difference (or absolute risk reduction) between groups. A true difference of 0 (or a relative risk of 1) is typically assumed for sample size calculation. However, assuming that the new treatment is truly slightly better or slightly worse than the standard may be clinically appropriate in some cases. This would indicate a need for a smaller or larger sample size, respectively, than that required under the usual assumption of no difference.

When the justification for the sample size in a noninferiority trial is not provided or the number of participants is based on an inappropriate approach (eg, using superiority trial calculations for a noninferiority trial), questions about the quality of the trial arise. The primary concern is whether the noninferiority margin was actually selected before the trial began, as it should have been. And if the researchers used overly optimistic assumptions about the efficacy of the new treatment relative to the standard therapy, the failure to rule out the margin could be misleading. (As with superiority trials that fail to reject the null hypothesis, post hoc power calculations should be avoided.) After the study has ended, the resulting CIs should be used to evaluate whether the study was large enough to adequately assess the relative effectiveness of the treatments.

The RE-LY trial calculated the sample size that was expected to provide 84% power to rule out the prespecified hazard ratio of 1.46, assuming a true event rate of 1.6% per year (presumably for both groups), a recruitment period of 2 years, and at least one year of follow-up. The sample size was subsequently increased from 15,000 to 18,000 to maintain power in case of a low event rate.4,5

5. Is the noninferiority trial as similar as possible to the trial(s) comparing the standard treatment with placebo?

Characteristics of participants, setting, reference treatment, and outcomes used in a noninferiority trial should be as close as possible to those in the trial(s) comparing the treatment with placebo. This is known as the constancy assumption, and it is key to researchers’ ability to draw a conclusion about noninferiority.

The trials used to calculate the noninferiority margin and the RE-LY trial itself involved similar populations of patients with AF, and the outcome (stroke) was similar.

6. Is a per protocol analysis reported in the results?

In randomized controlled superiority trials, the participants should be analyzed in the groups to which they were originally allocated, regardless of whether they adhered to treatment during the entire follow-up period. Such intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis is important because it provides a more conservative estimate of treatment effect—taking into account that some people who are offered treatment will not accept it and others will discontinue treatment. An ITT analysis therefore tends to minimize treatment effects compared with a “per protocol” analysis, in which participants are analyzed according to the treatment they actually received and are often removed from the analysis if they discontinue or do not adhere to treatment.

In noninferiority trials, if patients in the intervention group cross over to the standard treatment group or those in the standard treatment group have poor adherence, an ITT analysis can increase the risk of wrongly claiming noninferiority.7 Therefore, a per protocol analysis should be included—and indeed may be preferable.

In RE-LY, ITT analyses were reported, and complete follow-up data were available for 99.9% of patients. However, the rates of treatment discontinuation at one year were about 15% for those on dabigatran and 10% for the warfarin group, and 21% and 17%, respectively, at 2 years.4,5 If the new treatment were truly less efficacious than the standard treatment, these moderate discontinuation rates could lead to more similar rates of stroke in the 2 groups than would be expected with higher continuation rates, biasing results towards the alternative of noninferiority. Although the original publication of trial results did not include a per protocol analysis, the RE-LY authors later reported that a per protocol analysis yielded similar results to the ITT analysis.

7. Are the overall design and execution of the trial high quality?

Because a poor quality noninferiority trial can appear to demonstrate noninferiority, looking at such studies critically is crucial. Appropriate randomization, concealed allocation, masking, and careful attention to participant flow must all be assessed.2,3

To continue with our example, the RE-LY trial was well conducted. Randomization was performed centrally via an automated telephone system and 2 doses of dabigatran were administered in a masked fashion, while warfarin was open-label. Remarkably, follow-up was achieved for 99.9% of participants over a median of 2 years, and independent adjudicators masked to treatment group assessed outcomes.4,5

CORRESPONDENCE

Anne Mounsey, MD, UNC Chapel Hill Department of Family Medicine, 590 Manning Drive, CB 7595, Chapel Hill, NC 27590; anne_mounsey@med.unc.edu

1. Le Henanff A, Giraudeau B, Baron G, et al. Quality of reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials. JAMA. 2006;295:1147-1151.

2. Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Pocock SJ, et al; CONSORT Group. Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: extension of the CONSORT 2010 statement. JAMA. 2012;308:2594-2604.

3. Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman D; CONSORT Group (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials). The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. JAMA. 2001;285:1987-1991.

4. Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, et al; RE-LY Steering Committee and Investigators. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1139-1151.

5. Ezekowitz MD, Connolly S, Parekh A, et al. Rationale and design of RE-LY: randomized evaluation of long-term anticoagulant therapy, warfarin, compared with dabigatran. Am Heart J. 2009;157:805-810, 810.e1-2.

6. Hart RG, Benavente O, McBride R, et al. Antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:492-501.

7. US Department of Health and Human Services. Guidance for industry non-inferiority clinical trials. US Food and Drug Administration Web site. March 2010. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM202140.pdf. Accessed February 4, 2014.

1. Le Henanff A, Giraudeau B, Baron G, et al. Quality of reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials. JAMA. 2006;295:1147-1151.

2. Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Pocock SJ, et al; CONSORT Group. Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: extension of the CONSORT 2010 statement. JAMA. 2012;308:2594-2604.

3. Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman D; CONSORT Group (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials). The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. JAMA. 2001;285:1987-1991.

4. Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, et al; RE-LY Steering Committee and Investigators. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1139-1151.

5. Ezekowitz MD, Connolly S, Parekh A, et al. Rationale and design of RE-LY: randomized evaluation of long-term anticoagulant therapy, warfarin, compared with dabigatran. Am Heart J. 2009;157:805-810, 810.e1-2.

6. Hart RG, Benavente O, McBride R, et al. Antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:492-501.

7. US Department of Health and Human Services. Guidance for industry non-inferiority clinical trials. US Food and Drug Administration Web site. March 2010. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM202140.pdf. Accessed February 4, 2014.