User login

New guidelines update VTE treatment recommendations

Updated guidelines regarding the treatment of patients with venous thromboembolism advise abandoning the routine use of compression stockings for prevention of postthrombotic syndrome in patients who have had an acute deep vein thrombosis, according to Dr. Clive Kearon, lead author of the American College of Chest Physicians’ 10th edition of “Antithrombotic Therapy for VTE Disease” (Chest. 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2015.11.026).

The VTE guidelines include 12 recommendations. Two other key changes from the previous guidelines include new treatment recommendations about which patients with isolated subsegmental pulmonary embolism (PE) should, and should not, receive anticoagulant therapy, and as a recommendation for the use of non–vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) instead of warfarin for initial and long-term treatment of VTE in patients without cancer.

It is another of the group’s “living guidelines,” intended to be flexible, easy-to-update recommendations … based on the best available evidence, and to identify gaps in our knowledge and areas for future research,” Dr. Kearon of McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., said in an interview.

“Clinicians and guideline developers would like clinician decisions to be supported by very strong, or almost irrefutable, evidence,” he said. ”It’s difficult to do studies that provide irrefutable evidence, however,” and most of the updated recommendations are not based on the highest level of study evidence – large, randomized controlled trials.

Nevertheless, “the quality of evidence that supports guidelines and clinical decision making is much better now than it was 20 or 30 years ago,” Dr. Kearon said, mainly because more recent studies are considerably larger and involve multiple clinical centers. Plus, “we’re continually improving our skills at doing high-quality studies and studies that have a low potential for bias.”

The old recommendation to use graduated compression stockings for 2 years after DVT to reduce the risk of postthrombotic syndrome was mainly based on findings of two small single-center randomized trials, published in the Lancet and Annals of Internal Medicine, in which patients and study personnel were not blinded to stocking use. Since then, a much larger multicenter, placebo-controlled trial found that routine use of graduated compression stockings did not reduce postthrombotic syndrome or have other important benefits in 410 patients with a first proximal DVT randomized to receive either active or placebo compression stockings. The incidence of postthrombotic syndrome was 14% in the active group and 13% in the placebo group – a nonsignificant difference. The same study also found that routine use of graduated compression stockings did not reduce leg pain during the 3 months after a DVT – although the stockings were still able to reduce acute symptoms of DVT, and chronic symptoms in patients with postthrombotic syndrome.

The recommendation to replace warfarin with NOACs is based on new data suggesting that the agents are associated with a lower risk of bleeding, and on observations that NOACs are much easier for patients and clinicians to use. Several of the studies upon which earlier guidelines were based have been reanalyzed, Dr. Kearon and his coauthors wrote. There are also now extensive data on the comparative safety of NOACs and warfarin.

“Based on less bleeding with NOACs and greater convenience for patients and health care providers, we now suggest that a NOAC is used in preference to VKA [vitamin K antagonist] for the initial and long-term treatment of VTE in patients without cancer,” they wrote.

The recommendation to employ watchful waiting over anticoagulation in some patients with subsegmental pulmonary embolism is based on a compendium of clinical evidence rather than on large studies. A true subsegmental PE is unlikely to need anticoagulation, because it will have arisen from a small clot and thus carry a small risk of progression or recurrence.

“There is, however, high-quality evidence for the efficacy and safety of anticoagulant therapy in patients with larger PE, and this is expected to apply similarly to patients with subsegmental PE,” the authors wrote. “Whether the risk of progressive or recurrent VTE is high enough to justify anticoagulation in patients with subsegmental PE is uncertain.”

If clinical assessment suggests that anticoagulation isn’t appropriate, these patients should have a confirmatory bilateral ultrasound to rule out proximal DVTs, especially in high-risk locations. If a DVT is detected, clinicians may choose to conduct subsequent ultrasounds to identify and treat any evolving proximal clots.

The guideline has been endorsed by the American Association for Clinical Chemistry, the American College of Clinical Pharmacy, the International Society for Thrombosis and Haemostasis, and the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists.

Dr. Kearon has been compensated for speaking engagements sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim and Bayer Healthcare related to VTE therapy. Some of the other guideline authors also disclosed relationships with pharmaceutical companies.

Updated guidelines regarding the treatment of patients with venous thromboembolism advise abandoning the routine use of compression stockings for prevention of postthrombotic syndrome in patients who have had an acute deep vein thrombosis, according to Dr. Clive Kearon, lead author of the American College of Chest Physicians’ 10th edition of “Antithrombotic Therapy for VTE Disease” (Chest. 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2015.11.026).

The VTE guidelines include 12 recommendations. Two other key changes from the previous guidelines include new treatment recommendations about which patients with isolated subsegmental pulmonary embolism (PE) should, and should not, receive anticoagulant therapy, and as a recommendation for the use of non–vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) instead of warfarin for initial and long-term treatment of VTE in patients without cancer.

It is another of the group’s “living guidelines,” intended to be flexible, easy-to-update recommendations … based on the best available evidence, and to identify gaps in our knowledge and areas for future research,” Dr. Kearon of McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., said in an interview.

“Clinicians and guideline developers would like clinician decisions to be supported by very strong, or almost irrefutable, evidence,” he said. ”It’s difficult to do studies that provide irrefutable evidence, however,” and most of the updated recommendations are not based on the highest level of study evidence – large, randomized controlled trials.

Nevertheless, “the quality of evidence that supports guidelines and clinical decision making is much better now than it was 20 or 30 years ago,” Dr. Kearon said, mainly because more recent studies are considerably larger and involve multiple clinical centers. Plus, “we’re continually improving our skills at doing high-quality studies and studies that have a low potential for bias.”

The old recommendation to use graduated compression stockings for 2 years after DVT to reduce the risk of postthrombotic syndrome was mainly based on findings of two small single-center randomized trials, published in the Lancet and Annals of Internal Medicine, in which patients and study personnel were not blinded to stocking use. Since then, a much larger multicenter, placebo-controlled trial found that routine use of graduated compression stockings did not reduce postthrombotic syndrome or have other important benefits in 410 patients with a first proximal DVT randomized to receive either active or placebo compression stockings. The incidence of postthrombotic syndrome was 14% in the active group and 13% in the placebo group – a nonsignificant difference. The same study also found that routine use of graduated compression stockings did not reduce leg pain during the 3 months after a DVT – although the stockings were still able to reduce acute symptoms of DVT, and chronic symptoms in patients with postthrombotic syndrome.

The recommendation to replace warfarin with NOACs is based on new data suggesting that the agents are associated with a lower risk of bleeding, and on observations that NOACs are much easier for patients and clinicians to use. Several of the studies upon which earlier guidelines were based have been reanalyzed, Dr. Kearon and his coauthors wrote. There are also now extensive data on the comparative safety of NOACs and warfarin.

“Based on less bleeding with NOACs and greater convenience for patients and health care providers, we now suggest that a NOAC is used in preference to VKA [vitamin K antagonist] for the initial and long-term treatment of VTE in patients without cancer,” they wrote.

The recommendation to employ watchful waiting over anticoagulation in some patients with subsegmental pulmonary embolism is based on a compendium of clinical evidence rather than on large studies. A true subsegmental PE is unlikely to need anticoagulation, because it will have arisen from a small clot and thus carry a small risk of progression or recurrence.

“There is, however, high-quality evidence for the efficacy and safety of anticoagulant therapy in patients with larger PE, and this is expected to apply similarly to patients with subsegmental PE,” the authors wrote. “Whether the risk of progressive or recurrent VTE is high enough to justify anticoagulation in patients with subsegmental PE is uncertain.”

If clinical assessment suggests that anticoagulation isn’t appropriate, these patients should have a confirmatory bilateral ultrasound to rule out proximal DVTs, especially in high-risk locations. If a DVT is detected, clinicians may choose to conduct subsequent ultrasounds to identify and treat any evolving proximal clots.

The guideline has been endorsed by the American Association for Clinical Chemistry, the American College of Clinical Pharmacy, the International Society for Thrombosis and Haemostasis, and the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists.

Dr. Kearon has been compensated for speaking engagements sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim and Bayer Healthcare related to VTE therapy. Some of the other guideline authors also disclosed relationships with pharmaceutical companies.

Updated guidelines regarding the treatment of patients with venous thromboembolism advise abandoning the routine use of compression stockings for prevention of postthrombotic syndrome in patients who have had an acute deep vein thrombosis, according to Dr. Clive Kearon, lead author of the American College of Chest Physicians’ 10th edition of “Antithrombotic Therapy for VTE Disease” (Chest. 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2015.11.026).

The VTE guidelines include 12 recommendations. Two other key changes from the previous guidelines include new treatment recommendations about which patients with isolated subsegmental pulmonary embolism (PE) should, and should not, receive anticoagulant therapy, and as a recommendation for the use of non–vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) instead of warfarin for initial and long-term treatment of VTE in patients without cancer.

It is another of the group’s “living guidelines,” intended to be flexible, easy-to-update recommendations … based on the best available evidence, and to identify gaps in our knowledge and areas for future research,” Dr. Kearon of McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., said in an interview.

“Clinicians and guideline developers would like clinician decisions to be supported by very strong, or almost irrefutable, evidence,” he said. ”It’s difficult to do studies that provide irrefutable evidence, however,” and most of the updated recommendations are not based on the highest level of study evidence – large, randomized controlled trials.

Nevertheless, “the quality of evidence that supports guidelines and clinical decision making is much better now than it was 20 or 30 years ago,” Dr. Kearon said, mainly because more recent studies are considerably larger and involve multiple clinical centers. Plus, “we’re continually improving our skills at doing high-quality studies and studies that have a low potential for bias.”

The old recommendation to use graduated compression stockings for 2 years after DVT to reduce the risk of postthrombotic syndrome was mainly based on findings of two small single-center randomized trials, published in the Lancet and Annals of Internal Medicine, in which patients and study personnel were not blinded to stocking use. Since then, a much larger multicenter, placebo-controlled trial found that routine use of graduated compression stockings did not reduce postthrombotic syndrome or have other important benefits in 410 patients with a first proximal DVT randomized to receive either active or placebo compression stockings. The incidence of postthrombotic syndrome was 14% in the active group and 13% in the placebo group – a nonsignificant difference. The same study also found that routine use of graduated compression stockings did not reduce leg pain during the 3 months after a DVT – although the stockings were still able to reduce acute symptoms of DVT, and chronic symptoms in patients with postthrombotic syndrome.

The recommendation to replace warfarin with NOACs is based on new data suggesting that the agents are associated with a lower risk of bleeding, and on observations that NOACs are much easier for patients and clinicians to use. Several of the studies upon which earlier guidelines were based have been reanalyzed, Dr. Kearon and his coauthors wrote. There are also now extensive data on the comparative safety of NOACs and warfarin.

“Based on less bleeding with NOACs and greater convenience for patients and health care providers, we now suggest that a NOAC is used in preference to VKA [vitamin K antagonist] for the initial and long-term treatment of VTE in patients without cancer,” they wrote.

The recommendation to employ watchful waiting over anticoagulation in some patients with subsegmental pulmonary embolism is based on a compendium of clinical evidence rather than on large studies. A true subsegmental PE is unlikely to need anticoagulation, because it will have arisen from a small clot and thus carry a small risk of progression or recurrence.

“There is, however, high-quality evidence for the efficacy and safety of anticoagulant therapy in patients with larger PE, and this is expected to apply similarly to patients with subsegmental PE,” the authors wrote. “Whether the risk of progressive or recurrent VTE is high enough to justify anticoagulation in patients with subsegmental PE is uncertain.”

If clinical assessment suggests that anticoagulation isn’t appropriate, these patients should have a confirmatory bilateral ultrasound to rule out proximal DVTs, especially in high-risk locations. If a DVT is detected, clinicians may choose to conduct subsequent ultrasounds to identify and treat any evolving proximal clots.

The guideline has been endorsed by the American Association for Clinical Chemistry, the American College of Clinical Pharmacy, the International Society for Thrombosis and Haemostasis, and the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists.

Dr. Kearon has been compensated for speaking engagements sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim and Bayer Healthcare related to VTE therapy. Some of the other guideline authors also disclosed relationships with pharmaceutical companies.

FROM CHEST

USPSTF urges extra step before treating hypertension

Screening for and treating high blood pressure (HBP) to prevent cardiovascular and renal disease is a tried-and-true preventive intervention that is supported by strong evidence. And not surprisingly, when the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently updated its 2007 recommendation for blood pressure screening for adults, it once again gave an A recommendation for those ages 18 years and older. What is noteworthy, however, is that this update concentrates on the accuracy of blood pressure measurement methods and optimal frequency of screening.1

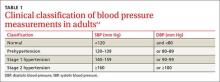

The most significant modification of past recommendations is that HBP found with office measurement of blood pressure (OMBP) should be confirmed with either ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) or home blood pressure monitoring (HBPM) before starting treatment. (For its recommendation, the USPSTF used the HBP definition from the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure [TABLE 1].2,3)

Ensuring accurate blood-pressure measurements. More than 30% of adults in the United States have HBP, with prevalence increasing with age (TABLE 2).2 Only about half of this population has HBP under control.4 This modifiable condition contributes to more than 360,000 deaths annually.2 However, while treatment of true HBP results in substantial benefits, it is important not to over-diagnose HBP and over-treat it.

Studies have shown that 15% to 30% of individuals diagnosed with HBP in a clinical setting will have blood pressure in the normal range when measurements are taken outside of the doctor’s office.1 This discrepancy can be due to measurement error, regression to the mean, recent caffeine ingestion by the patient, or isolated clinical hypertension wherein the stress and anxiety caused by clinic visits elevates blood pressure transiently.

With this in mind, the USPSTF recommends that OMBP-detected HBP be confirmed with either ABPM or HBPM. Of these 2 follow-up methods, ABPM is supported by stronger evidence and is preferred. The USPSTF includes HBPM as an alternative because ABPM equipment may not always be available—or affordable—and using the equipment may present logistical challenges.

Starting off on the right foot

Screening for HBP in a clinical setting is more accurate if conducted according to recommended procedures: use an appropriately sized cuff; take the measurement at least 5 minutes after the patient’s arrival while he or she is seated with legs uncrossed and the cuffed arm is at the level of the heart; and record the mean of 2 separate measurements. There appears to be no real difference in the accuracy of automated vs manual sphygmomanometers.

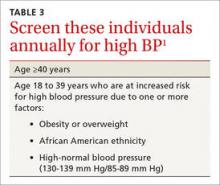

Optimal frequency of screening varies. While the USPSTF found little evidence to support any particular overall screening frequency, it recommends annual screening for those who are 40 years of age or older and those ages 18 to 39 who are obese or overweight, are African American, or who have high-normal blood pressure (TABLE 3).1 Screening every 3 to 5 years is recommended for individuals not in these categories.

Initial steps in treating HBP. The Task Force also commented on which medications to use when initiating HBP treatment (after lifestyle and dietary interventions). Non-African Americans should receive a thiazide diuretic, calcium channel blocker, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, or angiotensin-receptor blocker. African Americans should begin treatment with a thiazide diuretic or calcium channel blocker. These recommendations appear to have been adopted from the Eighth Joint National Committee, since the accompanying evidence report for the USPSTF’s update did not address this issue.5

Don't forget patient support

Patient support is key. As of June 2015, the Community Preventive Services Task Force (CPSTF) recommends self-measured blood pressure monitoring combined with additional support as a means of improving blood pressure control in those with HBP.4

Supportive measures include things such as patient counseling on medications and health behavior changes (eg, diet and exercise); education on HBP and blood pressure self-management; and use of secure electronic or Web-based tools such as text or e-mail reminders to measure blood pressure, show up for appointments, or communicate blood pressure readings to healthcare providers. Patients who participate in home self-measurement of blood pressure with additional support lower their systolic blood pressure, on average, 1.4 mm Hg more than those who do not.4

Remaining questions

The new USPSTF recommendation leaves several issues unaddressed. For one thing, the Affordable Care Act mandates that commercial health insurance plans provide services with an A or B Task Force recommendation to patients with no copayments. So does the new HBP recommendation mean payers have to make ABPM and HBPM available to patients at no charge?

There are other questions, too. If HBP detected by OMBP is not confirmed when ABPM is performed, should ABPM be repeated, and if so, at what interval? What is the role of emerging technologies that use devices other than arm cuffs to measure blood pressure?

Despite these uncertainties, the new USPSTF and CPSTF recommendations refine the longstanding in-office–only approach to diagnosing and monitoring HBP and advocate newer technologies that could help improve diagnostic accuracy, avoid over-diagnosis and over-treatment, and improve patient adherence to treatment goals.

1. US Preventive Services Task Force. High blood pressure in adults: screening. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/high-blood-pressure-in-adults-screening. Accessed November 24, 2015.

2. Piper MA, Evans CV, Burda BU, et al. Screening for high blood pressure in adults: a systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK269495/. Accessed November 24, 2015.

3. US Department of Health and Human Services. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Available at: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/files/docs/guidelines/jnc7full.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2015.

4. Community Preventive Services Task Force. Cardiovascular disease prevention and control: self-measured blood pressure monitoring interventions for improved blood pressure control — when combined with additional support. Available at: http://www.thecommunityguide.org/cvd/SMBP-additional.html. Accessed November 24, 2015.

5. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC8). JAMA. 2014;311:507-520.

Screening for and treating high blood pressure (HBP) to prevent cardiovascular and renal disease is a tried-and-true preventive intervention that is supported by strong evidence. And not surprisingly, when the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently updated its 2007 recommendation for blood pressure screening for adults, it once again gave an A recommendation for those ages 18 years and older. What is noteworthy, however, is that this update concentrates on the accuracy of blood pressure measurement methods and optimal frequency of screening.1

The most significant modification of past recommendations is that HBP found with office measurement of blood pressure (OMBP) should be confirmed with either ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) or home blood pressure monitoring (HBPM) before starting treatment. (For its recommendation, the USPSTF used the HBP definition from the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure [TABLE 1].2,3)

Ensuring accurate blood-pressure measurements. More than 30% of adults in the United States have HBP, with prevalence increasing with age (TABLE 2).2 Only about half of this population has HBP under control.4 This modifiable condition contributes to more than 360,000 deaths annually.2 However, while treatment of true HBP results in substantial benefits, it is important not to over-diagnose HBP and over-treat it.

Studies have shown that 15% to 30% of individuals diagnosed with HBP in a clinical setting will have blood pressure in the normal range when measurements are taken outside of the doctor’s office.1 This discrepancy can be due to measurement error, regression to the mean, recent caffeine ingestion by the patient, or isolated clinical hypertension wherein the stress and anxiety caused by clinic visits elevates blood pressure transiently.

With this in mind, the USPSTF recommends that OMBP-detected HBP be confirmed with either ABPM or HBPM. Of these 2 follow-up methods, ABPM is supported by stronger evidence and is preferred. The USPSTF includes HBPM as an alternative because ABPM equipment may not always be available—or affordable—and using the equipment may present logistical challenges.

Starting off on the right foot

Screening for HBP in a clinical setting is more accurate if conducted according to recommended procedures: use an appropriately sized cuff; take the measurement at least 5 minutes after the patient’s arrival while he or she is seated with legs uncrossed and the cuffed arm is at the level of the heart; and record the mean of 2 separate measurements. There appears to be no real difference in the accuracy of automated vs manual sphygmomanometers.

Optimal frequency of screening varies. While the USPSTF found little evidence to support any particular overall screening frequency, it recommends annual screening for those who are 40 years of age or older and those ages 18 to 39 who are obese or overweight, are African American, or who have high-normal blood pressure (TABLE 3).1 Screening every 3 to 5 years is recommended for individuals not in these categories.

Initial steps in treating HBP. The Task Force also commented on which medications to use when initiating HBP treatment (after lifestyle and dietary interventions). Non-African Americans should receive a thiazide diuretic, calcium channel blocker, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, or angiotensin-receptor blocker. African Americans should begin treatment with a thiazide diuretic or calcium channel blocker. These recommendations appear to have been adopted from the Eighth Joint National Committee, since the accompanying evidence report for the USPSTF’s update did not address this issue.5

Don't forget patient support

Patient support is key. As of June 2015, the Community Preventive Services Task Force (CPSTF) recommends self-measured blood pressure monitoring combined with additional support as a means of improving blood pressure control in those with HBP.4

Supportive measures include things such as patient counseling on medications and health behavior changes (eg, diet and exercise); education on HBP and blood pressure self-management; and use of secure electronic or Web-based tools such as text or e-mail reminders to measure blood pressure, show up for appointments, or communicate blood pressure readings to healthcare providers. Patients who participate in home self-measurement of blood pressure with additional support lower their systolic blood pressure, on average, 1.4 mm Hg more than those who do not.4

Remaining questions

The new USPSTF recommendation leaves several issues unaddressed. For one thing, the Affordable Care Act mandates that commercial health insurance plans provide services with an A or B Task Force recommendation to patients with no copayments. So does the new HBP recommendation mean payers have to make ABPM and HBPM available to patients at no charge?

There are other questions, too. If HBP detected by OMBP is not confirmed when ABPM is performed, should ABPM be repeated, and if so, at what interval? What is the role of emerging technologies that use devices other than arm cuffs to measure blood pressure?

Despite these uncertainties, the new USPSTF and CPSTF recommendations refine the longstanding in-office–only approach to diagnosing and monitoring HBP and advocate newer technologies that could help improve diagnostic accuracy, avoid over-diagnosis and over-treatment, and improve patient adherence to treatment goals.

Screening for and treating high blood pressure (HBP) to prevent cardiovascular and renal disease is a tried-and-true preventive intervention that is supported by strong evidence. And not surprisingly, when the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently updated its 2007 recommendation for blood pressure screening for adults, it once again gave an A recommendation for those ages 18 years and older. What is noteworthy, however, is that this update concentrates on the accuracy of blood pressure measurement methods and optimal frequency of screening.1

The most significant modification of past recommendations is that HBP found with office measurement of blood pressure (OMBP) should be confirmed with either ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) or home blood pressure monitoring (HBPM) before starting treatment. (For its recommendation, the USPSTF used the HBP definition from the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure [TABLE 1].2,3)

Ensuring accurate blood-pressure measurements. More than 30% of adults in the United States have HBP, with prevalence increasing with age (TABLE 2).2 Only about half of this population has HBP under control.4 This modifiable condition contributes to more than 360,000 deaths annually.2 However, while treatment of true HBP results in substantial benefits, it is important not to over-diagnose HBP and over-treat it.

Studies have shown that 15% to 30% of individuals diagnosed with HBP in a clinical setting will have blood pressure in the normal range when measurements are taken outside of the doctor’s office.1 This discrepancy can be due to measurement error, regression to the mean, recent caffeine ingestion by the patient, or isolated clinical hypertension wherein the stress and anxiety caused by clinic visits elevates blood pressure transiently.

With this in mind, the USPSTF recommends that OMBP-detected HBP be confirmed with either ABPM or HBPM. Of these 2 follow-up methods, ABPM is supported by stronger evidence and is preferred. The USPSTF includes HBPM as an alternative because ABPM equipment may not always be available—or affordable—and using the equipment may present logistical challenges.

Starting off on the right foot

Screening for HBP in a clinical setting is more accurate if conducted according to recommended procedures: use an appropriately sized cuff; take the measurement at least 5 minutes after the patient’s arrival while he or she is seated with legs uncrossed and the cuffed arm is at the level of the heart; and record the mean of 2 separate measurements. There appears to be no real difference in the accuracy of automated vs manual sphygmomanometers.

Optimal frequency of screening varies. While the USPSTF found little evidence to support any particular overall screening frequency, it recommends annual screening for those who are 40 years of age or older and those ages 18 to 39 who are obese or overweight, are African American, or who have high-normal blood pressure (TABLE 3).1 Screening every 3 to 5 years is recommended for individuals not in these categories.

Initial steps in treating HBP. The Task Force also commented on which medications to use when initiating HBP treatment (after lifestyle and dietary interventions). Non-African Americans should receive a thiazide diuretic, calcium channel blocker, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, or angiotensin-receptor blocker. African Americans should begin treatment with a thiazide diuretic or calcium channel blocker. These recommendations appear to have been adopted from the Eighth Joint National Committee, since the accompanying evidence report for the USPSTF’s update did not address this issue.5

Don't forget patient support

Patient support is key. As of June 2015, the Community Preventive Services Task Force (CPSTF) recommends self-measured blood pressure monitoring combined with additional support as a means of improving blood pressure control in those with HBP.4

Supportive measures include things such as patient counseling on medications and health behavior changes (eg, diet and exercise); education on HBP and blood pressure self-management; and use of secure electronic or Web-based tools such as text or e-mail reminders to measure blood pressure, show up for appointments, or communicate blood pressure readings to healthcare providers. Patients who participate in home self-measurement of blood pressure with additional support lower their systolic blood pressure, on average, 1.4 mm Hg more than those who do not.4

Remaining questions

The new USPSTF recommendation leaves several issues unaddressed. For one thing, the Affordable Care Act mandates that commercial health insurance plans provide services with an A or B Task Force recommendation to patients with no copayments. So does the new HBP recommendation mean payers have to make ABPM and HBPM available to patients at no charge?

There are other questions, too. If HBP detected by OMBP is not confirmed when ABPM is performed, should ABPM be repeated, and if so, at what interval? What is the role of emerging technologies that use devices other than arm cuffs to measure blood pressure?

Despite these uncertainties, the new USPSTF and CPSTF recommendations refine the longstanding in-office–only approach to diagnosing and monitoring HBP and advocate newer technologies that could help improve diagnostic accuracy, avoid over-diagnosis and over-treatment, and improve patient adherence to treatment goals.

1. US Preventive Services Task Force. High blood pressure in adults: screening. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/high-blood-pressure-in-adults-screening. Accessed November 24, 2015.

2. Piper MA, Evans CV, Burda BU, et al. Screening for high blood pressure in adults: a systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK269495/. Accessed November 24, 2015.

3. US Department of Health and Human Services. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Available at: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/files/docs/guidelines/jnc7full.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2015.

4. Community Preventive Services Task Force. Cardiovascular disease prevention and control: self-measured blood pressure monitoring interventions for improved blood pressure control — when combined with additional support. Available at: http://www.thecommunityguide.org/cvd/SMBP-additional.html. Accessed November 24, 2015.

5. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC8). JAMA. 2014;311:507-520.

1. US Preventive Services Task Force. High blood pressure in adults: screening. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/high-blood-pressure-in-adults-screening. Accessed November 24, 2015.

2. Piper MA, Evans CV, Burda BU, et al. Screening for high blood pressure in adults: a systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK269495/. Accessed November 24, 2015.

3. US Department of Health and Human Services. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Available at: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/files/docs/guidelines/jnc7full.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2015.

4. Community Preventive Services Task Force. Cardiovascular disease prevention and control: self-measured blood pressure monitoring interventions for improved blood pressure control — when combined with additional support. Available at: http://www.thecommunityguide.org/cvd/SMBP-additional.html. Accessed November 24, 2015.

5. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC8). JAMA. 2014;311:507-520.

Status Report From the American Acne & Rosacea Society on Medical Management of Acne in Adult Women, Part 3: Oral Therapies

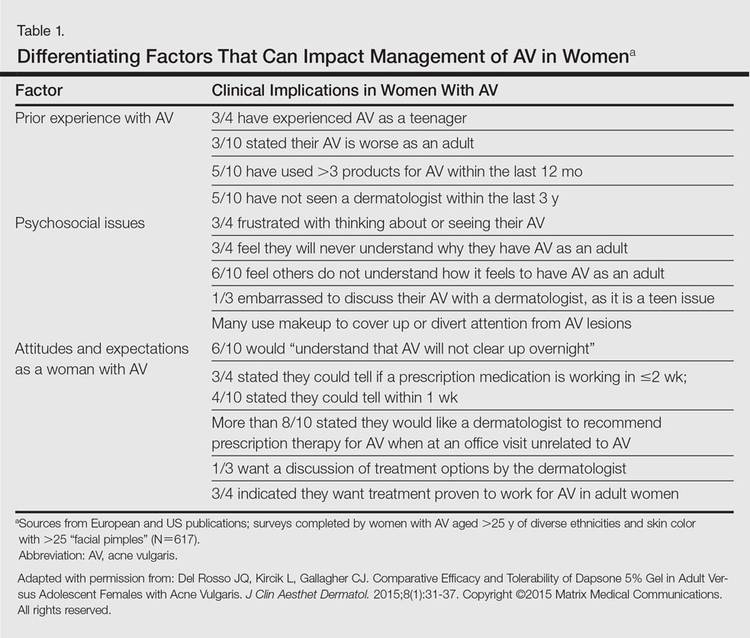

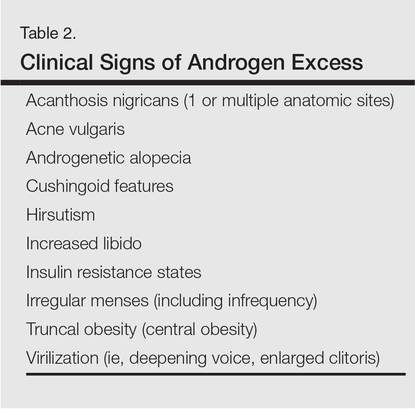

Selection of oral agents for treatment of AV in adult women is dependent on multiple factors including the patient’s age, medication history, child-bearing potential, clinical presentation, and treatment preference following a discussion of the anticipated benefits versus potential risks.1,2 In patients with the mixed inflammatory and comedonal clinical pattern of AV, oral antibiotics can be used concurrently with topical therapies when moderate to severe inflammatory lesions are noted.3,4 However, many adult women who had AV as teenagers have already utilized oral antibiotic therapies in the past and often are interested in alternative options, express concerns regarding antibiotic resistance, report a history of antibiotic-associated yeast infections or other side effects, and/or encounter issues related to drug-drug interactions.3,5-8 Oral hormonal therapies such as combination oral contraceptives (COCs) or spironolactone often are utilized to treat adult women with AV, sometimes in combination with each other or other agents. Combination oral contraceptives appear to be especially effective in the management of the U-shaped clinical pattern or predominantly inflammatory, late-onset AV.1,5,9,10 Potential warnings, contraindications, adverse effects, and drug-drug interactions are important to keep in mind when considering the use of oral hormonal therapies.8-10 Oral isotretinoin, which should be prescribed with strict adherence to the iPLEDGE™ program (https://www.ipledgeprogram.com/), remains a viable option for cases of severe nodular AV and selected cases of refractory inflammatory AV, especially when scarring and/or marked psychosocial distress are noted.1,2,5,11 Although it is recognized that adult women with AV typically present with either a mixed inflammatory and comedonal or U-shaped clinical pattern predominantly involving the lower face and anterolateral neck, the available data do not adequately differentiate the relative responsiveness of these clinical patterns to specific therapeutic agents.

Combination Oral Contraceptives

Combination oral contraceptives are commonly used to treat AV in adult women, including those without and those with measurable androgen excess (eg, polycystic ovary syndrome [PCOS]). Combination oral contraceptives contain ethinyl estradiol and a progestational agent (eg, progestin); the latter varies in terms of its nonselective receptor interactions and the relative magnitude or absence of androgenic effects.10,12,13 Although some COCs are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for AV, there is little data available to determine the comparative efficacy among these and other COCs.10,14 When choosing a COC for treatment of AV, it is best to select an agent whose effectiveness is supported by evidence from clinical studies.10,15

Mechanisms of Action

The reported mechanisms of action for COCs include inhibition of ovarian androgen production and ovulation through gonadotropin suppression; upregulated synthesis of sex hormone–binding globulin, which decreases free testosterone levels through receptor binding; and inhibition of 5α-reductase (by some progestins), which reduces conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone, the active derivative that induces androgenic effects at peripheral target tissues.10,13,16,17

Therapeutic Benefits

Use of COCs to treat AV in adult women who do not have measurable androgen excess is most rational in patients who also desire a method of contraception. Multiple monotherapy studies have demonstrated the efficacy of COCs in the treatment of AV on the face and trunk.4,10,12,15,17,18 It may take a minimum of 3 monthly cycles of use before acne lesion counts begin to appreciably decrease.12,15,19-21 Initiating COC therapy during menstruation ensures the absence of pregnancy. Combination oral contraceptives may be used with other topical and oral therapies for AV.2,3,9,10 Potential ancillary benefits of COCs include normalization of the menstrual cycle; reduced premenstrual dysphoric disorder symptoms; and reduced risk of endometrial cancer (approximately 50%), ovarian cancer (approximately 40%), and colorectal cancer.22-24

Risks and Contraindications

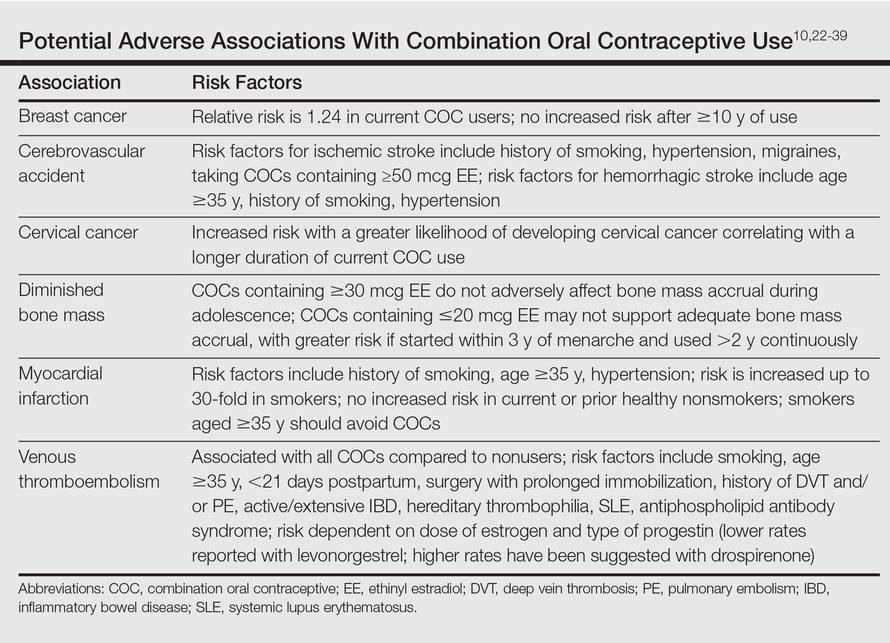

It is important to consider the potential risks associated with the use of COCs, especially in women with AV who are not seeking a method of contraception. Side effects of COCs can include nausea, breast tenderness, breakthrough bleeding, and weight gain.25,26 Potential adverse associations of COCs are described in the Table. The major potential vascular associations include venous thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, and cerebrovascular accident, all of which are influenced by concurrent factors such as a history of smoking, age (≥35 years), and hypertension.27-32 It is recommended that blood pressure be measured before initiating COC therapy as part of the general examination.33

The potential increase in breast cancer risk appears to be low, while the cervical cancer risk is reported to increase relative to the duration of use.34-37 This latter observation may be due to the greater likelihood of unprotected sex in women using a COC and exposure to multiple sexual partners in some cases, which may increase the likelihood of oncogenic human papillomavirus infection of the cervix. If a dermatologist elects to prescribe a COC to treat AV, it has been suggested that the patient also consult with her general practitioner or gynecologist to undergo pelvic and breast examinations and a Papanicolaou test.33 The recommendation for initial screening for cervical cancer is within 3 years of initiation of sexual intercourse or by 21 years of age, whichever is first.33,38,39

Combination oral contraceptives are not ideal for all adult women with AV. Absolute contraindications are pregnancy and history of thromboembolic, cardiac, or hepatic disease; in women aged 35 years and older who smoke, relative contraindications include hypertension, diabetes, migraines, breastfeeding, and current breast or liver cancer.33 In adult women with AV who have relative contra-indications but are likely to benefit from the use of a COC when other options are limited or not viable, consultation with a gynecologist is prudent. Other than rifamycin antibiotics (eg, rifampin) and griseofulvin, there is no definitive evidence that oral antibiotics (eg, tetracycline) or oral antifungal agents reduce the contraceptive efficacy of COCs, although cautions remain in print within some approved package inserts.8

Spironolactone

Available since 1957, spironolactone is an oral aldos-terone antagonist and potassium-sparing diuretic used to treat hypertension and congestive heart failure.9 Recognition of its antiandrogenic effects led to its use in dermatology to treat certain dermatologic disorders in women (eg, hirsutism, alopecia, AV).1,4,5,9,10 Spironolactone is not approved for AV by the FDA; therefore, available data from multiple independent studies and retrospective analyses that have been collectively reviewed support its efficacy when used as both monotherapy or in combination with other agents in adult women with AV, especially those with a U-shaped pattern and/or late-onset AV.9,40-43

Mechanism of Action

Spironolactone inhibits sebaceous gland activity through peripheral androgen receptor blockade, inhibition of 5α-reductase, decrease in androgen production, and increase in sex hormone–binding globulin.9,10,40

Therapeutic Benefits

Good to excellent improvement of AV in women, many of whom are postadolescent, has ranged from 66% to 100% in published reports9,40-43; however, inclusion and exclusion criteria, dosing regimens, and concomitant therapies were not usually controlled. Spironolactone has been used to treat AV in adult women as monotherapy or in combination with topical agents, oral antibiotics, and COCs.9,40-42 Additionally, dose-ranging studies have not been completed with spironolactone for AV.9,40 The suggested dose range is 50 mg to 200 mg daily; however, it usually is best to start at 50 mg daily and increase to 100 mg daily if clinical response is not adequate after 2 to 3 months. The gastrointestinal (GI) absorption of spironolactone is increased when ingested with a high-fat meal.9,10

Once effective control of AV is achieved, it is optimal to use the lowest dose needed to continue reasonable suppression of new AV lesions. There is no defined end point for spironolactone use in AV, with or without concurrent PCOS, as many adult women usually continue treatment with low-dose therapy because they experience marked flaring shortly after the drug is stopped.9

Risks and Contraindications

Side effects associated with spironolactone are dose related and include increased diuresis, migraines, menstrual irregularities, breast tenderness, gynecomastia, fatigue, and dizziness.9,10,40-44 Side effects (particularly menstrual irregularities and breast tenderness) are more common at doses higher than 100 mg daily, especially when used as monotherapy without concurrent use of a COC.9,40

Spironolactone-associated hyperkalemia is most clinically relevant in patients on higher doses (eg, 100–200 mg daily), in those with renal impairment and/or congestive heart failure, and when used concurrently with certain other medications. In any patient on spironolactone, the risk of clinically relevant hyperkalemia may be increased by coingestion of potassium supplements, potassium-based salt substitutes, potassium-sparing diuretics (eg, amiloride, triamterene); aldosterone antagonists and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (eg, lisinopril, benazepril); angiotensin II receptor blockers (eg, losartan, valsartan); and tri-methoprim (with or without sulfamethoxazole).8,9,40,45 Spironolactone may also increase serum levels of lithium or digoxin.9,40,45,46 For management of AV, it is best that spironolactone be avoided in patients taking any of these medications.9

In healthy adult women with AV who are not on medications or supplements that interact adversely with spironolactone, there is no definitive recommendation regarding monitoring of serum potassium levels during treatment with spironolactone, and it has been suggested that monitoring serum potassium levels in this subgroup is not necessary.47 However, each clinician is advised to choose whether or not they wish to obtain baseline and/or periodic serum potassium levels when prescribing spironolactone for AV based on their degree of comfort and the patient’s history. Baseline and periodic blood testing to evaluate serum electrolytes and renal function are reasonable, especially as adult women with AV are usually treated with spironolactone over a prolonged period of time.9

The FDA black box warning for spironolactone states that it is tumorigenic in chronic toxicity studies in rats and refers to exposures 25- to 100-fold higher than those administered to humans.9,48 Although continued vigilance is warranted, evaluation of large populations of women treated with spironolactone do not suggest an association with increased risk of breast cancer.49,50

Spironolactone is a category C drug and thus should be avoided during pregnancy, primarily due to animal data suggesting risks of hypospadias and feminization in male fetuses.9 Importantly, there is an absence of reports linking exposure during pregnancy with congenital defects in humans, including in 2 known cases of high-dose exposures for maternal Bartter syndrome.9

The active metabolite, canrenone, is known to be present in breast milk at 0.2% of the maternal daily dose, but breastfeeding is generally believed to be safe with spironolactone based on evidence to date.9

Oral Antibiotics

Oral antibiotic therapy may be used in combination with a topical regimen to treat AV in adult women, keeping in mind some important caveats.1-7 For instance, monotherapy with oral antibiotics should be avoided, and concomitant use of benzoyl peroxide is suggested to reduce emergence of antibiotic-resistant Propionibacterium acnes strains.3,4 A therapeutic exit plan also is suggested when prescribing oral antibiotics to limit treatment to 3 to 4 months, if possible, to help mitigate the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria (eg, staphylococci and streptococci).3-5,51

Tetracyclines, especially doxycycline and minocycline, are the most commonly prescribed agents. Doxycycline use warrants patient education on measures to limit the risks of esophageal and GI side effects and phototoxicity; enteric-coated and small tablet formulations have been shown to reduce GI side effects, especially when administered with food.3,52-55 In addition to vestibular side effects and hyperpigmentation, minocycline may be associated with rare but potentially severe adverse reactions such as drug hypersensitivity syndrome, autoimmune hepatitis, and lupus-like syndrome, which are reported more commonly in women.5,52,54 Vestibular side effects have been shown to decrease with use of extended-release tablets with weight-based dosing.53

Oral Isotretinoin

Oral isotretinoin is well established as highly effective for treatment of severe, recalcitrant AV, including nodular acne on the face and trunk.4,56 Currently available oral isotretinoins are branded generic formulations based on the pharmacokinetic profile of the original brand (Accutane [Roche Pharmaceuticals]) and with the use of Lidose Technology (Absorica [Cipher Pharmaceuticals]), which substantially increases GI absorption of isotretinoin in the absence of ingestion with a high-calorie, high-fat meal.57 The short- and long-term efficacy, dosing regimens, safety considerations, and serious teratogenic risks for oral isotretinoin are well published.4,56-58 Importantly, oral isotretinoin must be prescribed with strict adherence to the federally mandated iPLEDGE risk management program.

Low-dose oral isotretinoin therapy (<0.5 mg/kg–1 mg/kg daily) administered over several months longer than conventional regimens (ie, 16–20 weeks) has been suggested with demonstrated efficacy.57 However, this approach is not optimal due to the lack of established sustained clearance of AV after discontinuation of therapy and the greater potential for exposure to isotretinoin during pregnancy. Recurrences of AV do occur after completion of isotretinoin therapy, especially if cumulative systemic exposure to the drug during the initial course of treatment was inadequate.56,57

Oral isotretinoin has been shown to be effective in AV in adult women with or without PCOS with 0.5 mg/kg to 1 mg/kg daily and a total cumulative exposure of 120 mg/kg to 150 mg/kg.59 In one study, the presence of PCOS and greater number of nodules at baseline were predictive of a higher risk of relapse during the second year posttreatment.59

Conclusion

All oral therapies that are used to treat AV in adult women warrant individual consideration of possible benefits versus risks. Careful attention to possible side effects, patient-related risk factors, and potential drug-drug interactions is important. End points of therapy are not well established, with the exception of oral isotretinoin therapy. Clinicians must use their judgment in each case along with obtaining feedback from patients regarding the selection of therapy after a discussion of the available options.

- Holzmann R, Shakery K. Postadolescent acne in females. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2014;27(suppl 1):3-8.

- Villasenor J, Berson DS, Kroshinsky D. Treatment guidelines in adult women. In: Shalita AR, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, eds. Acne Vulgaris. London, United Kingdom: Informa Healthcare; 2011:198-207.

- Del Rosso JQ, Kim G. Optimizing use of oral antibiotics in acne vulgaris. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:33-42.

- Gollnick H, Cunliffe W, Berson D, et al. Management of acne: report from a Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(suppl 1):S1-S37.

- Fisk WA, Lev-Tov HA, Sivamani RK. Epidemiology and management of acne in adult women. Curr Derm Rep. 2014;3:29-39.

- Del Rosso JQ, Leyden JJ. Status report on antibiotic resistance: implications for the dermatologist. Dermatol Clin. 2007;25:127-132.

- Bowe WP, Leyden JJ. Clinical implications of antibiotic resistance: risk of systemic infection from Staphylococcus and Streptococcus. In: Shalita AR, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, eds. Acne Vulgaris. London, United Kingdom: Informa Healthcare; 2011:125-133.

- Del Rosso JQ. Oral antibiotic drug interactions of clinical significance to dermatologists. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:91-94.

- Kim GK, Del Rosso JQ. Oral spironolactone in post-teenage female patients with acne vulgaris: practical considerations for the clinician based on current data and clinical experience. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:37-50.

- Keri J, Berson DS, Thiboutot DM. Hormonal treatment of acne in women. In: Shalita AR, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, eds. Acne Vulgaris. London, United Kingdom: Informa Healthcare; 2011:146-155.

- American Academy of Dermatology. Position statement on isotretinoin. AAD Web site. https://www.aad.org /Forms/Policies/Uploads/PS/PS-Isotretinoin.pdf. Updated November 13, 2010. Accessed October 28, 2015.

- Arowojolu AO, Gallo MF, Lopez LM, et al. Combined oral contraceptive pills for treatment of acne. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. June 2012;7:CD004425.

- Sitruk-Ware R. Pharmacology of different progestogens: the special case of drospirenone. Climacteric. 2005;8 (suppl 3):4-12.

- Arowojolu AO, Gallo MF, Lopez LM, et al. Combined oral contraceptive pills for the treatment of acne. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. July 2012;7:CD004425.

- Thiboutot D, Archer DF, Lemay A, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of a low-dose contraceptive containing 20 microg of ethinyl estradiol and 100 microg of levonogestrel for acne treatment. Fertil Steril. 2001;76:461-468.

- Koulianos GT. Treatment of acne with oral contraceptives: criteria for pill selection. Cutis. 2000;66:281-286.

- Rabe T, Kowald A, Ortmann J, et al. Inhibition of skin 5-alpha reductase by oral contraceptive progestins in vitro. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2000;14:223-230.

- Palli MB, Reyes-Habito CM, Lima XT, et al. A single-center, randomized double-blind, parallel-group study to examine the safety and efficacy of 3mg drospirenone/0.02mg ethinyl estradiol compared with placebo in the treatment of moderate truncal acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:633-637.

- Koltun W, Maloney JM, Marr J, et al. Treatment of moderate acne vulgaris using a combined oral contraceptive containing ethinylestradiol 20 μg plus drospirenone 3 mg administered in a 24/4 regimen: a pooled analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;155:171-175.

- Maloney JM, Dietze P, Watson D, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a low-dose combined oral contraceptive containing 3 mg drospirenone plus 20 μg ethinylestradiol in the treatment of acne vulgaris: lesion counts, investigator ratings and subject self-assessment. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:837-844.

- Lucky AW, Koltun W, Thiboutot D, et al. A combined oral contraceptive containing 3-mg drospirenone/20-μg ethinyl estradiol in the treatment of acne vulgaris: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study evaluating lesion counts and participant self-assessment. Cutis. 2008;82:143-150.

- Burkman R, Schlesselman JJ, Zieman M. Safety concerns and health benefits associated with oral contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(suppl 4):S5-S22.

- Maguire K, Westhoff C. The state of hormonal contraception today: established and emerging noncontraceptive health benefits. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205 (suppl 4):S4-S8.

- Weiss NS, Sayvetz TA. Incidence of endometrial cancer in relation to the use of oral contraceptives. N Engl J Med. 1980;302:551-554.

- Tyler KH, Zirwas MJ. Contraception and the dermatologist. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:1022-1029.

- Gallo MF, Lopez LM, Grimes DA, et al. Combination contraceptives: effects on weight. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;4:CD003987.

- de Bastos M, Stegeman BH, Rosendaal FR, et al. Combined oral contraceptives: venous thrombosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;3:CD010813.

- Raymond EG, Burke AE, Espey E. Combined hormonal contraceptives and venous thromboembolism: putting the risks into perspective. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:1039-1044.

- Jick SS, Hernandez RK. Risk of non-fatal venous thromboembolism in women using oral contraceptives containing drospirenone compared with women using oral contraceptives containing levonorgestrel: case-control study using United States claims data. BMJ. 2011;342:d2151.

- US Food and Drug Administration Office of Surveillance and Epidemiology. Combined hormonal contraceptives (CHCs) and the risk of cardiovascular disease endpoints. US Food and Drug Administration Web site. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs /Drug Safety/UCM277384.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2015.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Gynecologic Practice. Risk of venous thromboembolism among users of drospirenone-containing oral contraceptive pills. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:1239-1242.

- World Health Organization. Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception: Report of a WHO Scientific Group. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1998. Technical Report Series 877.

- Frangos JE, Alavian CN, Kimball AB. Acne and oral contraceptives: update on women’s health screening guidelines. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:781-786.

- Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Breast cancer and hormonal contraceptives: collaborative reanalysis of individual data on 53 297 women with breast cancer and 100 239 women without breast cancer from 54 epidemiological studies. Lancet. 1996;347:1713-1727.

- Gierisch JM, Coeytaux RR, Urrutia RP, et al. Oral contraceptive use and risk of breast, cervical, colorectal, and endometrial cancers: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:1931-1943.

- International Collaboration of Epidemiological Studies of Cervical Cancer. Cervical cancer and hormonal contraceptives: collaborative reanalysis of individual data for 16 573 women with cervical cancer and 35 509 women without cervical cancer from 24 epidemiological studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1609-1621.

- Agostino H, Di Meglio G. Low-dose oral contraceptives in adolescents: how low can you go? J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2010;23:195-201.

- Buzney E, Sheu J, Buzney C, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome: a review for dermatologists: part II. Treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:859.e1-859.e15.

- Stewart FH, Harper CC, Ellertson CE, et al. Clinical breast and pelvic examination requirements for hormonal contraception: current practice vs evidence. JAMA. 2001;285:2232-2239.

- Sawaya ME, Somani N. Antiandrogens and androgen inhibitors. In: Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. Philadelpha, PA: Saunders; 2013:361-374.

- Muhlemann MF, Carter GD, Cream JJ, et al. Oral spironolactone: an effective treatment for acne vulgaris in women. Br J Dermatol. 1986;115:227-232.

- Shaw JC. Low-dose adjunctive spironolactone in the treatment of acne in women: a retrospective analysis of 85 consecutively treated patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:498-502.

- Sato K, Matsumoto D, Iizuka F, et al. Anti-androgenic therapy using oral spironolactone for acne vulgaris in Asians. Aesth Plast Surg. 2006;30:689-694.

- Shaw JC, White LE. Long-term safety of spironolactone in acne: results of an 8-year follow-up study. J Cutan Med Surg. 2002;6:541-545.

- Stockley I. Antihypertensive drug interactions. In: Stockley I, ed. Drug Interactions. 5th ed. London, United Kingdom: Pharmaceutical Press; 1999:335-347.

- Antoniou T, Gomes T, Mamdani MM, et al. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole induced hyperkalaemia in elderly patients receiving spironolactone: nested case-control study. BMJ. 2011;343:d5228.

- Plovanich M, Weng QY, Mostaghimi A. Low usefulness of potassium monitoring among healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:941-944.

- Aldactone [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer Inc; 2008.

- Biggar RJ, Andersen EW, Wohlfahrt J, et al. Spironolactone use and the risk of breast and gynecologic cancers. Cancer Epidemiol. 2013;37:870-875.

- Mackenzie IS, Macdonald TM, Thompson A, et al. Spironolactone and risk of incident breast cancer in women older than 55 years: retrospective, matched cohort study. BMJ. 2012;345:e4447.

- Dreno B, Thiboutot D, Gollnick H, et al. Antibiotic stewardship in dermatology: limiting antibiotic use in acne. Eur J Dermatol. 2014;24:330-334.

- Kim S, Michaels BD, Kim GK, et al. Systemic antibacterial agents. In: Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. Philadelpha, PA: Saunders; 2013:61-97.

- Leyden JJ, Del Rosso JQ. Oral antibiotic therapy for acne vulgaris: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics perspectives. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4:40-47.

- Del Rosso JQ. Oral antibiotics. In: Shalita AR, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, eds. Acne Vulgaris. London, United Kingdom: Informa Healthcare; 2011:113-124.

- Del Rosso JQ. Oral doxycycline in the management of acne vulgaris: current perspectives on clinical use and recent findings with a new double-scored small tablet formulation. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:19-26.

- Osofsky MG, Strauss JS. Isotretinoin. In: Shalita AR, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, eds. Acne Vulgaris. London, United Kingdom: Informa Healthcare; 2011:134-145.

- Leyden JJ, Del Rosso JQ, Baum EW. The use of isotretinoin in the treatment of acne vulgaris: clinical considerations and future directions. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7(suppl 2):S3-S21.

- Patton TJ, Ferris LK. Systemic retinoids. In: Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. Philadelpha, PA: Saunders; 2013:252-268.

- Cakir GA, Erdogan FG, Gurler A. Isotretinoin treatment in nodulocystic acne with and without polycystic ovary syndrome: efficacy and determinants of relapse. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:371-376.

Selection of oral agents for treatment of AV in adult women is dependent on multiple factors including the patient’s age, medication history, child-bearing potential, clinical presentation, and treatment preference following a discussion of the anticipated benefits versus potential risks.1,2 In patients with the mixed inflammatory and comedonal clinical pattern of AV, oral antibiotics can be used concurrently with topical therapies when moderate to severe inflammatory lesions are noted.3,4 However, many adult women who had AV as teenagers have already utilized oral antibiotic therapies in the past and often are interested in alternative options, express concerns regarding antibiotic resistance, report a history of antibiotic-associated yeast infections or other side effects, and/or encounter issues related to drug-drug interactions.3,5-8 Oral hormonal therapies such as combination oral contraceptives (COCs) or spironolactone often are utilized to treat adult women with AV, sometimes in combination with each other or other agents. Combination oral contraceptives appear to be especially effective in the management of the U-shaped clinical pattern or predominantly inflammatory, late-onset AV.1,5,9,10 Potential warnings, contraindications, adverse effects, and drug-drug interactions are important to keep in mind when considering the use of oral hormonal therapies.8-10 Oral isotretinoin, which should be prescribed with strict adherence to the iPLEDGE™ program (https://www.ipledgeprogram.com/), remains a viable option for cases of severe nodular AV and selected cases of refractory inflammatory AV, especially when scarring and/or marked psychosocial distress are noted.1,2,5,11 Although it is recognized that adult women with AV typically present with either a mixed inflammatory and comedonal or U-shaped clinical pattern predominantly involving the lower face and anterolateral neck, the available data do not adequately differentiate the relative responsiveness of these clinical patterns to specific therapeutic agents.

Combination Oral Contraceptives

Combination oral contraceptives are commonly used to treat AV in adult women, including those without and those with measurable androgen excess (eg, polycystic ovary syndrome [PCOS]). Combination oral contraceptives contain ethinyl estradiol and a progestational agent (eg, progestin); the latter varies in terms of its nonselective receptor interactions and the relative magnitude or absence of androgenic effects.10,12,13 Although some COCs are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for AV, there is little data available to determine the comparative efficacy among these and other COCs.10,14 When choosing a COC for treatment of AV, it is best to select an agent whose effectiveness is supported by evidence from clinical studies.10,15

Mechanisms of Action

The reported mechanisms of action for COCs include inhibition of ovarian androgen production and ovulation through gonadotropin suppression; upregulated synthesis of sex hormone–binding globulin, which decreases free testosterone levels through receptor binding; and inhibition of 5α-reductase (by some progestins), which reduces conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone, the active derivative that induces androgenic effects at peripheral target tissues.10,13,16,17

Therapeutic Benefits

Use of COCs to treat AV in adult women who do not have measurable androgen excess is most rational in patients who also desire a method of contraception. Multiple monotherapy studies have demonstrated the efficacy of COCs in the treatment of AV on the face and trunk.4,10,12,15,17,18 It may take a minimum of 3 monthly cycles of use before acne lesion counts begin to appreciably decrease.12,15,19-21 Initiating COC therapy during menstruation ensures the absence of pregnancy. Combination oral contraceptives may be used with other topical and oral therapies for AV.2,3,9,10 Potential ancillary benefits of COCs include normalization of the menstrual cycle; reduced premenstrual dysphoric disorder symptoms; and reduced risk of endometrial cancer (approximately 50%), ovarian cancer (approximately 40%), and colorectal cancer.22-24

Risks and Contraindications

It is important to consider the potential risks associated with the use of COCs, especially in women with AV who are not seeking a method of contraception. Side effects of COCs can include nausea, breast tenderness, breakthrough bleeding, and weight gain.25,26 Potential adverse associations of COCs are described in the Table. The major potential vascular associations include venous thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, and cerebrovascular accident, all of which are influenced by concurrent factors such as a history of smoking, age (≥35 years), and hypertension.27-32 It is recommended that blood pressure be measured before initiating COC therapy as part of the general examination.33

The potential increase in breast cancer risk appears to be low, while the cervical cancer risk is reported to increase relative to the duration of use.34-37 This latter observation may be due to the greater likelihood of unprotected sex in women using a COC and exposure to multiple sexual partners in some cases, which may increase the likelihood of oncogenic human papillomavirus infection of the cervix. If a dermatologist elects to prescribe a COC to treat AV, it has been suggested that the patient also consult with her general practitioner or gynecologist to undergo pelvic and breast examinations and a Papanicolaou test.33 The recommendation for initial screening for cervical cancer is within 3 years of initiation of sexual intercourse or by 21 years of age, whichever is first.33,38,39

Combination oral contraceptives are not ideal for all adult women with AV. Absolute contraindications are pregnancy and history of thromboembolic, cardiac, or hepatic disease; in women aged 35 years and older who smoke, relative contraindications include hypertension, diabetes, migraines, breastfeeding, and current breast or liver cancer.33 In adult women with AV who have relative contra-indications but are likely to benefit from the use of a COC when other options are limited or not viable, consultation with a gynecologist is prudent. Other than rifamycin antibiotics (eg, rifampin) and griseofulvin, there is no definitive evidence that oral antibiotics (eg, tetracycline) or oral antifungal agents reduce the contraceptive efficacy of COCs, although cautions remain in print within some approved package inserts.8

Spironolactone

Available since 1957, spironolactone is an oral aldos-terone antagonist and potassium-sparing diuretic used to treat hypertension and congestive heart failure.9 Recognition of its antiandrogenic effects led to its use in dermatology to treat certain dermatologic disorders in women (eg, hirsutism, alopecia, AV).1,4,5,9,10 Spironolactone is not approved for AV by the FDA; therefore, available data from multiple independent studies and retrospective analyses that have been collectively reviewed support its efficacy when used as both monotherapy or in combination with other agents in adult women with AV, especially those with a U-shaped pattern and/or late-onset AV.9,40-43

Mechanism of Action

Spironolactone inhibits sebaceous gland activity through peripheral androgen receptor blockade, inhibition of 5α-reductase, decrease in androgen production, and increase in sex hormone–binding globulin.9,10,40

Therapeutic Benefits

Good to excellent improvement of AV in women, many of whom are postadolescent, has ranged from 66% to 100% in published reports9,40-43; however, inclusion and exclusion criteria, dosing regimens, and concomitant therapies were not usually controlled. Spironolactone has been used to treat AV in adult women as monotherapy or in combination with topical agents, oral antibiotics, and COCs.9,40-42 Additionally, dose-ranging studies have not been completed with spironolactone for AV.9,40 The suggested dose range is 50 mg to 200 mg daily; however, it usually is best to start at 50 mg daily and increase to 100 mg daily if clinical response is not adequate after 2 to 3 months. The gastrointestinal (GI) absorption of spironolactone is increased when ingested with a high-fat meal.9,10

Once effective control of AV is achieved, it is optimal to use the lowest dose needed to continue reasonable suppression of new AV lesions. There is no defined end point for spironolactone use in AV, with or without concurrent PCOS, as many adult women usually continue treatment with low-dose therapy because they experience marked flaring shortly after the drug is stopped.9

Risks and Contraindications

Side effects associated with spironolactone are dose related and include increased diuresis, migraines, menstrual irregularities, breast tenderness, gynecomastia, fatigue, and dizziness.9,10,40-44 Side effects (particularly menstrual irregularities and breast tenderness) are more common at doses higher than 100 mg daily, especially when used as monotherapy without concurrent use of a COC.9,40

Spironolactone-associated hyperkalemia is most clinically relevant in patients on higher doses (eg, 100–200 mg daily), in those with renal impairment and/or congestive heart failure, and when used concurrently with certain other medications. In any patient on spironolactone, the risk of clinically relevant hyperkalemia may be increased by coingestion of potassium supplements, potassium-based salt substitutes, potassium-sparing diuretics (eg, amiloride, triamterene); aldosterone antagonists and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (eg, lisinopril, benazepril); angiotensin II receptor blockers (eg, losartan, valsartan); and tri-methoprim (with or without sulfamethoxazole).8,9,40,45 Spironolactone may also increase serum levels of lithium or digoxin.9,40,45,46 For management of AV, it is best that spironolactone be avoided in patients taking any of these medications.9

In healthy adult women with AV who are not on medications or supplements that interact adversely with spironolactone, there is no definitive recommendation regarding monitoring of serum potassium levels during treatment with spironolactone, and it has been suggested that monitoring serum potassium levels in this subgroup is not necessary.47 However, each clinician is advised to choose whether or not they wish to obtain baseline and/or periodic serum potassium levels when prescribing spironolactone for AV based on their degree of comfort and the patient’s history. Baseline and periodic blood testing to evaluate serum electrolytes and renal function are reasonable, especially as adult women with AV are usually treated with spironolactone over a prolonged period of time.9

The FDA black box warning for spironolactone states that it is tumorigenic in chronic toxicity studies in rats and refers to exposures 25- to 100-fold higher than those administered to humans.9,48 Although continued vigilance is warranted, evaluation of large populations of women treated with spironolactone do not suggest an association with increased risk of breast cancer.49,50

Spironolactone is a category C drug and thus should be avoided during pregnancy, primarily due to animal data suggesting risks of hypospadias and feminization in male fetuses.9 Importantly, there is an absence of reports linking exposure during pregnancy with congenital defects in humans, including in 2 known cases of high-dose exposures for maternal Bartter syndrome.9

The active metabolite, canrenone, is known to be present in breast milk at 0.2% of the maternal daily dose, but breastfeeding is generally believed to be safe with spironolactone based on evidence to date.9

Oral Antibiotics

Oral antibiotic therapy may be used in combination with a topical regimen to treat AV in adult women, keeping in mind some important caveats.1-7 For instance, monotherapy with oral antibiotics should be avoided, and concomitant use of benzoyl peroxide is suggested to reduce emergence of antibiotic-resistant Propionibacterium acnes strains.3,4 A therapeutic exit plan also is suggested when prescribing oral antibiotics to limit treatment to 3 to 4 months, if possible, to help mitigate the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria (eg, staphylococci and streptococci).3-5,51

Tetracyclines, especially doxycycline and minocycline, are the most commonly prescribed agents. Doxycycline use warrants patient education on measures to limit the risks of esophageal and GI side effects and phototoxicity; enteric-coated and small tablet formulations have been shown to reduce GI side effects, especially when administered with food.3,52-55 In addition to vestibular side effects and hyperpigmentation, minocycline may be associated with rare but potentially severe adverse reactions such as drug hypersensitivity syndrome, autoimmune hepatitis, and lupus-like syndrome, which are reported more commonly in women.5,52,54 Vestibular side effects have been shown to decrease with use of extended-release tablets with weight-based dosing.53

Oral Isotretinoin

Oral isotretinoin is well established as highly effective for treatment of severe, recalcitrant AV, including nodular acne on the face and trunk.4,56 Currently available oral isotretinoins are branded generic formulations based on the pharmacokinetic profile of the original brand (Accutane [Roche Pharmaceuticals]) and with the use of Lidose Technology (Absorica [Cipher Pharmaceuticals]), which substantially increases GI absorption of isotretinoin in the absence of ingestion with a high-calorie, high-fat meal.57 The short- and long-term efficacy, dosing regimens, safety considerations, and serious teratogenic risks for oral isotretinoin are well published.4,56-58 Importantly, oral isotretinoin must be prescribed with strict adherence to the federally mandated iPLEDGE risk management program.

Low-dose oral isotretinoin therapy (<0.5 mg/kg–1 mg/kg daily) administered over several months longer than conventional regimens (ie, 16–20 weeks) has been suggested with demonstrated efficacy.57 However, this approach is not optimal due to the lack of established sustained clearance of AV after discontinuation of therapy and the greater potential for exposure to isotretinoin during pregnancy. Recurrences of AV do occur after completion of isotretinoin therapy, especially if cumulative systemic exposure to the drug during the initial course of treatment was inadequate.56,57

Oral isotretinoin has been shown to be effective in AV in adult women with or without PCOS with 0.5 mg/kg to 1 mg/kg daily and a total cumulative exposure of 120 mg/kg to 150 mg/kg.59 In one study, the presence of PCOS and greater number of nodules at baseline were predictive of a higher risk of relapse during the second year posttreatment.59

Conclusion

All oral therapies that are used to treat AV in adult women warrant individual consideration of possible benefits versus risks. Careful attention to possible side effects, patient-related risk factors, and potential drug-drug interactions is important. End points of therapy are not well established, with the exception of oral isotretinoin therapy. Clinicians must use their judgment in each case along with obtaining feedback from patients regarding the selection of therapy after a discussion of the available options.