User login

Severe hypercalcemia in a 54-year-old woman

A morbidly obese 54-year-old woman presented to the emergency department after experiencing generalized abdominal pain for 3 days. She rated the pain as 5 on a scale of 10 and described it as dull, cramping, waxing and waning, not radiating, and not relieved with changes of position—in fact, not alleviated by anything she had tried. Her pain was associated with nausea and 1 episode of vomiting. She also experienced constipation before the onset of pain.

She denied recent trauma, recent travel, diarrhea, fevers, weakness, shortness of breath, chest pain, other muscle pains, or recent changes in diet. She also denied having this pain in the past. She said she had unintentionally lost some weight but was not certain how much. She denied tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drug use. She had no history of surgery.

Her medical history included hypertension, anemia, and uterine fibroids. Her current medications included losartan, hydrochlorothiazide, and albuterol. She had no family history of significant disease.

INITIAL EVALUATION AND MANAGEMENT

On admission, her temperature was 97.8°F (36.6°C), heart rate 100 beats per minute, blood pressure 136/64 mm Hg, respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute, oxygen saturation 97% on room air, weight 130.6 kg, and body mass index 35 kg/m2.

She was alert and oriented to person, place, and time. She was in mild discomfort but no distress. Her lungs were clear to auscultation, with no wheezing or crackles. Heart rate and rhythm were regular, with no extra heart sounds or murmurs. Bowel sounds were normal in all 4 quadrants, with tenderness to palpation of the epigastric area, but with no guarding or rebound tenderness.

Laboratory test results

Notable results of blood testing at presentation were as follows:

- Hemoglobin 8.2 g/dL (reference range 12.3–15.3)

- Hematocrit 26% (41–50)

- Mean corpuscular volume 107 fL (80–100)

- Blood urea nitrogen 33 mg/dL (8–21); 6 months earlier it was 16

- Serum creatinine 3.6 mg/dL (0.58–0.96); 6 months earlier, it was 0.75

- Albumin 3.3 g/dL (3.5–5)

- Calcium 18.4 mg/dL (8.4–10.2); 6 months earlier, it was 9.6

- Corrected calcium 19 mg/dL.

Findings on imaging, electrocardiography

Chest radiography showed no acute cardiopulmonary abnormalities. Abdominal computed tomography without contrast showed no abnormalities within the pancreas and no evidence of inflammation or obstruction. Electrocardiography showed sinus tachycardia.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

1. Which is the most likely cause of this patient’s symptoms?

- Primary hyperparathyroidism

- Malignancy

- Her drug therapy

- Familial hypercalcemic hypocalciuria

In total, her laboratory results were consistent with macrocytic anemia, severe hypercalcemia, and acute kidney injury, and she had generalized symptoms.

Primary hyperparathyroidism

A main cause of hypercalcemia is primary hyperparathyroidism, and this needs to be ruled out. Benign adenomas are the most common cause of primary hyperparathyroidism, and a risk factor for benign adenoma is exposure to therapeutic levels of radiation.3

In hyperparathyroidism, there is an increased secretion of parathyroid hormone (PTH), which has multiple effects including increased reabsorption of calcium from the urine, increased excretion of phosphate, and increased expression of 1,25-hydroxyvitamin D hydroxylase to activate vitamin D. PTH also stimulates osteoclasts to increase their expression of receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B ligand (RANKL), which has a downstream effect on osteoclast precursors to cause bone reabsorption.3

Inherited primary hyperparathyroidism tends to present at a younger age, with multiple overactive parathyroid glands.3 Given our patient’s age, inherited primary hyparathyroidism is thus less likely.

Malignancy

The probability that malignancy is causing the hypercalcemia increases with calcium levels greater than 13 mg/dL. Epidemiologically, in hospitalized patients with hypercalcemia, the source tends to be malignancy.4 Typically, patients who develop hypercalcemia from malignancy have a worse prognosis.5

Solid tumors and leukemias can cause hypercalcemia. The mechanisms include humoral factors secreted by the malignancy, local osteolysis due to tumor invasion of bone, and excessive absorption of calcium due to excess vitamin D produced by malignancies.5 The cancers that most frequently cause an increase in calcium resorption are lung cancer, renal cancer, breast cancer, and multiple myeloma.1

Solid tumors with no bone metastasis and non-Hodgkin lymphoma that release PTH-related protein (PTHrP) cause humoral hypercalcemia in malignancy. The patient is typically in an advanced stage of disease. PTHrP increases serum calcium levels by decreasing the kidney’s ability to excrete calcium and by increasing bone turnover. It has no effect on intestinal absorption because of its inability to stimulate activated vitamin D3. Thus, the increase in systemic calcium comes directly from breakdown of bone and inability to excrete the excess.

PTHrP has a unique role in breast cancer: it is released locally in areas where cancer cells have metastasized to bone, but it does not cause a systemic effect. Bone resorption occurs in areas of metastasis and results from an increase in expression of RANKL and RANK in osteoclasts in response to the effects of PTHrP, leading to an increase in the production of osteoclastic cells.1

Tamoxifen, an endocrine therapy often used in breast cancer, also causes a release of bone-reabsorbing factors from tumor cells, which can partially contribute to hypercalcemia.5

Myeloma cells secrete RANKL, which stimulates osteoclastic activity, and they also release interleukin 6 (IL-6) and activating macrophage inflammatory protein alpha. Serum testing usually shows low or normal intact PTH, PTHrP, and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D.1

Patients with multiple myeloma have a worse prognosis if they have a high red blood cell distribution width, a condition shown to correlate with malnutrition, leading to deficiencies in vitamin B12 and to poor response to treatment.6 Up to 14% of patients with multiple myeloma have vitamin B12 deficiency.7

Our patient’s recent weight loss and severe hypercalcemia raise suspicion of malignancy. Further, her obesity makes proper routine breast examination difficult and thus increases the chance of undiagnosed breast cancer.8 Her decrease in renal function and her anemia complicated by hypercalcemia also raise suspicion of multiple myeloma.

Hypercalcemia due to drug therapy

Thiazide diuretics, lithium, teriparatide, and vitamin A in excessive amounts can raise the serum calcium concentration.5 Our patient was taking a thiazide for hypertension, but her extremely high calcium level places drug-induced hypercalcemia as the sole cause lower on the differential list.

Familial hypercalcemic hypocalciuria

Familial hypercalcemic hypocalciuria is a rare autosomal-dominant cause of hypercalcemia in which the ability of the body (and especially the kidneys) to sense levels of calcium is impaired, leading to a decrease in excretion of calcium in the urine.3 Very high calcium levels are rare in hypercalcemic hypocalciuria.3 In our patient with a corrected calcium concentration of nearly 19 mg/dL, familial hypercalcemic hypocalciuria is very unlikely to be the cause of the hypercalcemia.

WHAT ARE THE NEXT STEPS IN THE WORKUP?

As hypercalcemia has been confirmed, the intact PTH level should be checked to determine whether the patient’s condition is PTH-mediated. If the PTH level is in the upper range of normal or is minimally elevated, primary hyperparathyroidism is likely. Elevated PTH confirms primary hyperparathyroidism. A low-normal or low intact PTH confirms a non-PTH-mediated process, and once this is confirmed, PTHrP levels should be checked. An elevated PTHrP suggests humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy. Serum protein electrophoresis, urine protein electrophoresis, and a serum light chain assay should be performed to rule out multiple myeloma.

Vitamin D toxicity is associated with high concentrations of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D and 25-hydroxyvitamin D metabolites. These levels should be checked in this patient.

Other disorders that cause hypercalcemia are vitamin A toxicity and hyperthyroidism, so vitamin A and thyroid-stimulating hormone levels should also be checked.5

CASE CONTINUED

After further questioning, the patient said that she had had lower back pain about 1 to 2 weeks before coming to the emergency room; her primary care doctor had said the pain was likely from muscle strain. The pain had almost resolved but was still present.

The results of further laboratory testing were as follows:

- Serum PTH 11 pg/mL (15–65)

- PTHrP 3.4 pmol/L (< 2.0)

- Protein electrophoresis showed a monoclonal (M) spike of 0.2 g/dL (0)

- Activated vitamin D < 5 ng/mL (19.9–79.3)

- Vitamin A 7.2 mg/dL (33.1–100)

- Vitamin B12 194 pg/mL (239–931)

- Thyroid-stimulating hormone 1.21 mIU/ L (0.47–4.68

- Free thyroxine 1.27 ng/dL (0.78–2.19)

- Iron 103 µg/dL (37–170)

- Total iron-binding capacity 335 µg/dL (265–497)

- Transferrin 248 mg/dL (206–381)

- Ferritin 66 ng/mL (11.1–264)

- Urine protein (random) 100 mg/dL (0–20)

- Urine microalbumin (random) 5.9 mg/dL (0–1.6)

- Urine creatinine clearance 88.5 mL/min (88–128)

- Urine albumin-creatinine ratio 66.66 mg/g (< 30).

Imaging reports

A nuclear bone scan showed increased bone uptake in the hip and both shoulders, consistent with arthritis, and increased activity in 2 of the lower left ribs, associated with rib fractures secondary to lytic lesions. A skeletal survey at a later date showed multiple well-circumscribed “punched-out” lytic lesions in both forearms and both femurs.

2. What should be the next step in this patient’s management?

- Intravenous (IV) fluids

- Calcitonin

- Bisphosphonate treatment

- Denosumab

- Hemodialysis

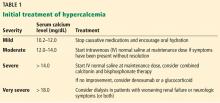

Initial treatment of severe hypercalcemia includes the following:

Start IV isotonic fluids at a rate of 150 mL/h (if the patient is making urine) to maintain urine output at more than 100 mL/h. Closely monitor urine output.

Give calcitonin 4 IU/kg in combination with IV fluids to reduce calcium levels within the first 12 to 48 hours of treatment.

Give a bisphosphonate, eg, zoledronic acid 4 mg over 15 minutes, or pamidronate 60 to 90 mg over 2 hours. Zoledronic acid is preferred in malignancy-induced hypercalcemia because it is more potent. Doses should be adjusted in patients with renal failure.

Give denosumab if hypercalcemia is refractory to bisphosphonates, or when bisphosphonates cannot be used in renal failure.9

Hemodialysis is performed in patients who have significant neurologic symptoms irrespective of acute renal insufficiency.

Our patient was started on 0.9% sodium chloride at a rate of 150 mL/h for severe hypercalcemia. Zoledronic acid 4 mg IV was given once. These measures lowered her calcium level and lessened her acute kidney injury.

ADDITIONAL FINDINGS

Urine testing was positive for Bence Jones protein. Immune electrophoresis, performed because of suspicion of multiple myeloma, showed an elevated level of kappa light chains at 806.7 mg/dL (0.33–1.94) and normal lambda light chains at 0.62 mg/dL (0.57–2.63). The immunoglobulin G level was low at 496 mg/dL (610–1,660). In patients with severe hypercalcemia, these results point to a diagnosis of malignancy. Bone marrow aspiration study showed greater than 10% plasma cells, confirming multiple myeloma.

MULTIPLE MYELOMA

The diagnosis of multiple myeloma is based in part on the presence of 10% or more of clonal bone marrow plasma cells10 and of specific end-organ damage (anemia, hypercalcemia, renal insufficiency, or bone lesions).9

Bone marrow clonality can be shown by the ratio of kappa to lambda light chains as detected with immunohistochemistry, immunofluorescence, or flow cytometry.11 The normal ratio is 0.26 to 1.65 for a patient with normal kidney function. In this patient, however, the ratio was 1,301.08 (806.67 kappa to 0.62 lambda), which was extremely out of range. The patient’s bone marrow biopsy results revealed the presence of 15% clonal bone marrow plasma cells.

Multiple myeloma causes osteolytic lesions through increased activation of osteoclast activating factor that stimulates the growth of osteoclast precursors. At the same time, it inhibits osteoblast formation via multiple pathways, including the action of sclerostin.11 Our patient had lytic lesions in 2 left lower ribs and in both forearms and femurs.

Hypercalcemia in multiple myeloma is attributed to 2 main factors: bone breakdown and macrophage overactivation. Multiple myeloma cells increase the release of macrophage inflammatory protein 1-alpha and tumor necrosis factor, which are inflammatory proteins that cause an increase in macrophages, which cause an increase in calcitriol.11 As noted, our patient’s calcium level at presentation was 18.4 mg/dL uncorrected and 18.96 mg/dL corrected.

Cast nephropathy can occur in the distal tubules from the increased free light chains circulating and combining with Tamm-Horsfall protein, which in turn causes obstruction and local inflammation,12 leading to a rise in creatinine levels and resulting in acute kidney injury,12 as in our patient.

TREATMENT CONSIDERATIONS IN MULTIPLE MYELOMA

Our patient was referred to an oncologist for management.

In the management of multiple myeloma, the patient’s quality of life needs to be considered. With the development of new agents to combat the damages of the osteolytic effects, there is hope for improving quality of life.13,14 New agents under study include anabolic agents such as antisclerostin and anti-Dickkopf-1, which promote osteoblastogenesis, leading to bone formation, with the possibility of repairing existing damage.15

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- If hypercalcemia is mild to moderate, consider primary hyperparathyroidism.

- Identify patients with severe symptoms of hypercalcemia such as volume depletion, acute kidney injury, arrhythmia, or seizures.

- Confirm severe cases of hypercalcemia and treat severe cases effectively.

- Severe hypercalcemia may need further investigation into a potential underlying malignancy.

- Sternlicht H, Glezerman IG. Hypercalcemia of malignancy and new treatment options. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2015; 11:1779–1788. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S83681

- Ahmed R, Hashiba K. Reliability of QT intervals as indicators of clinical hypercalcemia. Clin Cardiol 1988; 11(6):395–400. doi:10.1002/clc.4960110607

- Bilezikian JP, Cusano NE, Khan AA, Liu JM, Marcocci C, Bandeira F. Primary hyperparathyroidism. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016; 2:16033. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2016.33

- Kuchay MS, Kaur P, Mishra SK, Mithal A. The changing profile of hypercalcemia in a tertiary care setting in North India: an 18-month retrospective study. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab 2017; 14(2):131–135. doi:10.11138/ccmbm/2017.14.1.131

- Rosner MH, Dalkin AC. Onco-nephrology: the pathophysiology and treatment of malignancy-associated hypercalcemia. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2012; 7(10):1722–1729. doi:10.2215/CJN.02470312

- Ai L, Mu S, Hu Y. Prognostic role of RDW in hematological malignancies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Cell Int 2018; 18:61. doi:10.1186/s12935-018-0558-3

- Baz R, Alemany C, Green R, Hussein MA. Prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency in patients with plasma cell dyscrasias: a retrospective review. Cancer 2004; 101(4):790–795. doi:10.1002/cncr.20441

- Elmore JG, Carney PA, Abraham LA, et al. The association between obesity and screening mammography accuracy. Arch Intern Med 2004; 164(10):1140–1147. doi:10.1001/archinte.164.10.1140

- Gerecke C, Fuhrmann S, Strifler S, Schmidt-Hieber M, Einsele H, Knop S. The diagnosis and treatment of multiple myeloma. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2016; 113(27–28):470–476. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2016.0470

- Rajkumar SV. Multiple myeloma: 2016 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol 2016; 91(7):719–734. doi:10.1002/ajh.24402

- Silbermann R, Roodman GD. Myeloma bone disease: pathophysiology and management. J Bone Oncol 2013; 2(2):59–69. doi:10.1016/j.jbo.2013.04.001

- Doshi M, Lahoti A, Danesh FR, Batuman V, Sanders PW; American Society of Nephrology Onco-Nephrology Forum. Paraprotein-related kidney disease: kidney injury from paraproteins—what determines the site of injury? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2016; 11(12):2288–2294. doi:10.2215/CJN.02560316

- Reece D. Update on the initial therapy of multiple myeloma. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2013. doi:10.1200/EdBook_AM.2013.33.e307

- Nishida H. Bone-targeted agents in multiple myeloma. Hematol Rep 2018; 10(1):7401. doi:10.4081/hr.2018.7401

- Ring ES, Lawson MA, Snowden JA, Jolley I, Chantry AD. New agents in the treatment of myeloma bone disease. Calcif Tissue Int 2018; 102(2):196–209. doi:10.1007/s00223-017-0351-7

A morbidly obese 54-year-old woman presented to the emergency department after experiencing generalized abdominal pain for 3 days. She rated the pain as 5 on a scale of 10 and described it as dull, cramping, waxing and waning, not radiating, and not relieved with changes of position—in fact, not alleviated by anything she had tried. Her pain was associated with nausea and 1 episode of vomiting. She also experienced constipation before the onset of pain.

She denied recent trauma, recent travel, diarrhea, fevers, weakness, shortness of breath, chest pain, other muscle pains, or recent changes in diet. She also denied having this pain in the past. She said she had unintentionally lost some weight but was not certain how much. She denied tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drug use. She had no history of surgery.

Her medical history included hypertension, anemia, and uterine fibroids. Her current medications included losartan, hydrochlorothiazide, and albuterol. She had no family history of significant disease.

INITIAL EVALUATION AND MANAGEMENT

On admission, her temperature was 97.8°F (36.6°C), heart rate 100 beats per minute, blood pressure 136/64 mm Hg, respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute, oxygen saturation 97% on room air, weight 130.6 kg, and body mass index 35 kg/m2.

She was alert and oriented to person, place, and time. She was in mild discomfort but no distress. Her lungs were clear to auscultation, with no wheezing or crackles. Heart rate and rhythm were regular, with no extra heart sounds or murmurs. Bowel sounds were normal in all 4 quadrants, with tenderness to palpation of the epigastric area, but with no guarding or rebound tenderness.

Laboratory test results

Notable results of blood testing at presentation were as follows:

- Hemoglobin 8.2 g/dL (reference range 12.3–15.3)

- Hematocrit 26% (41–50)

- Mean corpuscular volume 107 fL (80–100)

- Blood urea nitrogen 33 mg/dL (8–21); 6 months earlier it was 16

- Serum creatinine 3.6 mg/dL (0.58–0.96); 6 months earlier, it was 0.75

- Albumin 3.3 g/dL (3.5–5)

- Calcium 18.4 mg/dL (8.4–10.2); 6 months earlier, it was 9.6

- Corrected calcium 19 mg/dL.

Findings on imaging, electrocardiography

Chest radiography showed no acute cardiopulmonary abnormalities. Abdominal computed tomography without contrast showed no abnormalities within the pancreas and no evidence of inflammation or obstruction. Electrocardiography showed sinus tachycardia.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

1. Which is the most likely cause of this patient’s symptoms?

- Primary hyperparathyroidism

- Malignancy

- Her drug therapy

- Familial hypercalcemic hypocalciuria

In total, her laboratory results were consistent with macrocytic anemia, severe hypercalcemia, and acute kidney injury, and she had generalized symptoms.

Primary hyperparathyroidism

A main cause of hypercalcemia is primary hyperparathyroidism, and this needs to be ruled out. Benign adenomas are the most common cause of primary hyperparathyroidism, and a risk factor for benign adenoma is exposure to therapeutic levels of radiation.3

In hyperparathyroidism, there is an increased secretion of parathyroid hormone (PTH), which has multiple effects including increased reabsorption of calcium from the urine, increased excretion of phosphate, and increased expression of 1,25-hydroxyvitamin D hydroxylase to activate vitamin D. PTH also stimulates osteoclasts to increase their expression of receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B ligand (RANKL), which has a downstream effect on osteoclast precursors to cause bone reabsorption.3

Inherited primary hyperparathyroidism tends to present at a younger age, with multiple overactive parathyroid glands.3 Given our patient’s age, inherited primary hyparathyroidism is thus less likely.

Malignancy

The probability that malignancy is causing the hypercalcemia increases with calcium levels greater than 13 mg/dL. Epidemiologically, in hospitalized patients with hypercalcemia, the source tends to be malignancy.4 Typically, patients who develop hypercalcemia from malignancy have a worse prognosis.5

Solid tumors and leukemias can cause hypercalcemia. The mechanisms include humoral factors secreted by the malignancy, local osteolysis due to tumor invasion of bone, and excessive absorption of calcium due to excess vitamin D produced by malignancies.5 The cancers that most frequently cause an increase in calcium resorption are lung cancer, renal cancer, breast cancer, and multiple myeloma.1

Solid tumors with no bone metastasis and non-Hodgkin lymphoma that release PTH-related protein (PTHrP) cause humoral hypercalcemia in malignancy. The patient is typically in an advanced stage of disease. PTHrP increases serum calcium levels by decreasing the kidney’s ability to excrete calcium and by increasing bone turnover. It has no effect on intestinal absorption because of its inability to stimulate activated vitamin D3. Thus, the increase in systemic calcium comes directly from breakdown of bone and inability to excrete the excess.

PTHrP has a unique role in breast cancer: it is released locally in areas where cancer cells have metastasized to bone, but it does not cause a systemic effect. Bone resorption occurs in areas of metastasis and results from an increase in expression of RANKL and RANK in osteoclasts in response to the effects of PTHrP, leading to an increase in the production of osteoclastic cells.1

Tamoxifen, an endocrine therapy often used in breast cancer, also causes a release of bone-reabsorbing factors from tumor cells, which can partially contribute to hypercalcemia.5

Myeloma cells secrete RANKL, which stimulates osteoclastic activity, and they also release interleukin 6 (IL-6) and activating macrophage inflammatory protein alpha. Serum testing usually shows low or normal intact PTH, PTHrP, and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D.1

Patients with multiple myeloma have a worse prognosis if they have a high red blood cell distribution width, a condition shown to correlate with malnutrition, leading to deficiencies in vitamin B12 and to poor response to treatment.6 Up to 14% of patients with multiple myeloma have vitamin B12 deficiency.7

Our patient’s recent weight loss and severe hypercalcemia raise suspicion of malignancy. Further, her obesity makes proper routine breast examination difficult and thus increases the chance of undiagnosed breast cancer.8 Her decrease in renal function and her anemia complicated by hypercalcemia also raise suspicion of multiple myeloma.

Hypercalcemia due to drug therapy

Thiazide diuretics, lithium, teriparatide, and vitamin A in excessive amounts can raise the serum calcium concentration.5 Our patient was taking a thiazide for hypertension, but her extremely high calcium level places drug-induced hypercalcemia as the sole cause lower on the differential list.

Familial hypercalcemic hypocalciuria

Familial hypercalcemic hypocalciuria is a rare autosomal-dominant cause of hypercalcemia in which the ability of the body (and especially the kidneys) to sense levels of calcium is impaired, leading to a decrease in excretion of calcium in the urine.3 Very high calcium levels are rare in hypercalcemic hypocalciuria.3 In our patient with a corrected calcium concentration of nearly 19 mg/dL, familial hypercalcemic hypocalciuria is very unlikely to be the cause of the hypercalcemia.

WHAT ARE THE NEXT STEPS IN THE WORKUP?

As hypercalcemia has been confirmed, the intact PTH level should be checked to determine whether the patient’s condition is PTH-mediated. If the PTH level is in the upper range of normal or is minimally elevated, primary hyperparathyroidism is likely. Elevated PTH confirms primary hyperparathyroidism. A low-normal or low intact PTH confirms a non-PTH-mediated process, and once this is confirmed, PTHrP levels should be checked. An elevated PTHrP suggests humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy. Serum protein electrophoresis, urine protein electrophoresis, and a serum light chain assay should be performed to rule out multiple myeloma.

Vitamin D toxicity is associated with high concentrations of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D and 25-hydroxyvitamin D metabolites. These levels should be checked in this patient.

Other disorders that cause hypercalcemia are vitamin A toxicity and hyperthyroidism, so vitamin A and thyroid-stimulating hormone levels should also be checked.5

CASE CONTINUED

After further questioning, the patient said that she had had lower back pain about 1 to 2 weeks before coming to the emergency room; her primary care doctor had said the pain was likely from muscle strain. The pain had almost resolved but was still present.

The results of further laboratory testing were as follows:

- Serum PTH 11 pg/mL (15–65)

- PTHrP 3.4 pmol/L (< 2.0)

- Protein electrophoresis showed a monoclonal (M) spike of 0.2 g/dL (0)

- Activated vitamin D < 5 ng/mL (19.9–79.3)

- Vitamin A 7.2 mg/dL (33.1–100)

- Vitamin B12 194 pg/mL (239–931)

- Thyroid-stimulating hormone 1.21 mIU/ L (0.47–4.68

- Free thyroxine 1.27 ng/dL (0.78–2.19)

- Iron 103 µg/dL (37–170)

- Total iron-binding capacity 335 µg/dL (265–497)

- Transferrin 248 mg/dL (206–381)

- Ferritin 66 ng/mL (11.1–264)

- Urine protein (random) 100 mg/dL (0–20)

- Urine microalbumin (random) 5.9 mg/dL (0–1.6)

- Urine creatinine clearance 88.5 mL/min (88–128)

- Urine albumin-creatinine ratio 66.66 mg/g (< 30).

Imaging reports

A nuclear bone scan showed increased bone uptake in the hip and both shoulders, consistent with arthritis, and increased activity in 2 of the lower left ribs, associated with rib fractures secondary to lytic lesions. A skeletal survey at a later date showed multiple well-circumscribed “punched-out” lytic lesions in both forearms and both femurs.

2. What should be the next step in this patient’s management?

- Intravenous (IV) fluids

- Calcitonin

- Bisphosphonate treatment

- Denosumab

- Hemodialysis

Initial treatment of severe hypercalcemia includes the following:

Start IV isotonic fluids at a rate of 150 mL/h (if the patient is making urine) to maintain urine output at more than 100 mL/h. Closely monitor urine output.

Give calcitonin 4 IU/kg in combination with IV fluids to reduce calcium levels within the first 12 to 48 hours of treatment.

Give a bisphosphonate, eg, zoledronic acid 4 mg over 15 minutes, or pamidronate 60 to 90 mg over 2 hours. Zoledronic acid is preferred in malignancy-induced hypercalcemia because it is more potent. Doses should be adjusted in patients with renal failure.

Give denosumab if hypercalcemia is refractory to bisphosphonates, or when bisphosphonates cannot be used in renal failure.9

Hemodialysis is performed in patients who have significant neurologic symptoms irrespective of acute renal insufficiency.

Our patient was started on 0.9% sodium chloride at a rate of 150 mL/h for severe hypercalcemia. Zoledronic acid 4 mg IV was given once. These measures lowered her calcium level and lessened her acute kidney injury.

ADDITIONAL FINDINGS

Urine testing was positive for Bence Jones protein. Immune electrophoresis, performed because of suspicion of multiple myeloma, showed an elevated level of kappa light chains at 806.7 mg/dL (0.33–1.94) and normal lambda light chains at 0.62 mg/dL (0.57–2.63). The immunoglobulin G level was low at 496 mg/dL (610–1,660). In patients with severe hypercalcemia, these results point to a diagnosis of malignancy. Bone marrow aspiration study showed greater than 10% plasma cells, confirming multiple myeloma.

MULTIPLE MYELOMA

The diagnosis of multiple myeloma is based in part on the presence of 10% or more of clonal bone marrow plasma cells10 and of specific end-organ damage (anemia, hypercalcemia, renal insufficiency, or bone lesions).9

Bone marrow clonality can be shown by the ratio of kappa to lambda light chains as detected with immunohistochemistry, immunofluorescence, or flow cytometry.11 The normal ratio is 0.26 to 1.65 for a patient with normal kidney function. In this patient, however, the ratio was 1,301.08 (806.67 kappa to 0.62 lambda), which was extremely out of range. The patient’s bone marrow biopsy results revealed the presence of 15% clonal bone marrow plasma cells.

Multiple myeloma causes osteolytic lesions through increased activation of osteoclast activating factor that stimulates the growth of osteoclast precursors. At the same time, it inhibits osteoblast formation via multiple pathways, including the action of sclerostin.11 Our patient had lytic lesions in 2 left lower ribs and in both forearms and femurs.

Hypercalcemia in multiple myeloma is attributed to 2 main factors: bone breakdown and macrophage overactivation. Multiple myeloma cells increase the release of macrophage inflammatory protein 1-alpha and tumor necrosis factor, which are inflammatory proteins that cause an increase in macrophages, which cause an increase in calcitriol.11 As noted, our patient’s calcium level at presentation was 18.4 mg/dL uncorrected and 18.96 mg/dL corrected.

Cast nephropathy can occur in the distal tubules from the increased free light chains circulating and combining with Tamm-Horsfall protein, which in turn causes obstruction and local inflammation,12 leading to a rise in creatinine levels and resulting in acute kidney injury,12 as in our patient.

TREATMENT CONSIDERATIONS IN MULTIPLE MYELOMA

Our patient was referred to an oncologist for management.

In the management of multiple myeloma, the patient’s quality of life needs to be considered. With the development of new agents to combat the damages of the osteolytic effects, there is hope for improving quality of life.13,14 New agents under study include anabolic agents such as antisclerostin and anti-Dickkopf-1, which promote osteoblastogenesis, leading to bone formation, with the possibility of repairing existing damage.15

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- If hypercalcemia is mild to moderate, consider primary hyperparathyroidism.

- Identify patients with severe symptoms of hypercalcemia such as volume depletion, acute kidney injury, arrhythmia, or seizures.

- Confirm severe cases of hypercalcemia and treat severe cases effectively.

- Severe hypercalcemia may need further investigation into a potential underlying malignancy.

A morbidly obese 54-year-old woman presented to the emergency department after experiencing generalized abdominal pain for 3 days. She rated the pain as 5 on a scale of 10 and described it as dull, cramping, waxing and waning, not radiating, and not relieved with changes of position—in fact, not alleviated by anything she had tried. Her pain was associated with nausea and 1 episode of vomiting. She also experienced constipation before the onset of pain.

She denied recent trauma, recent travel, diarrhea, fevers, weakness, shortness of breath, chest pain, other muscle pains, or recent changes in diet. She also denied having this pain in the past. She said she had unintentionally lost some weight but was not certain how much. She denied tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drug use. She had no history of surgery.

Her medical history included hypertension, anemia, and uterine fibroids. Her current medications included losartan, hydrochlorothiazide, and albuterol. She had no family history of significant disease.

INITIAL EVALUATION AND MANAGEMENT

On admission, her temperature was 97.8°F (36.6°C), heart rate 100 beats per minute, blood pressure 136/64 mm Hg, respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute, oxygen saturation 97% on room air, weight 130.6 kg, and body mass index 35 kg/m2.

She was alert and oriented to person, place, and time. She was in mild discomfort but no distress. Her lungs were clear to auscultation, with no wheezing or crackles. Heart rate and rhythm were regular, with no extra heart sounds or murmurs. Bowel sounds were normal in all 4 quadrants, with tenderness to palpation of the epigastric area, but with no guarding or rebound tenderness.

Laboratory test results

Notable results of blood testing at presentation were as follows:

- Hemoglobin 8.2 g/dL (reference range 12.3–15.3)

- Hematocrit 26% (41–50)

- Mean corpuscular volume 107 fL (80–100)

- Blood urea nitrogen 33 mg/dL (8–21); 6 months earlier it was 16

- Serum creatinine 3.6 mg/dL (0.58–0.96); 6 months earlier, it was 0.75

- Albumin 3.3 g/dL (3.5–5)

- Calcium 18.4 mg/dL (8.4–10.2); 6 months earlier, it was 9.6

- Corrected calcium 19 mg/dL.

Findings on imaging, electrocardiography

Chest radiography showed no acute cardiopulmonary abnormalities. Abdominal computed tomography without contrast showed no abnormalities within the pancreas and no evidence of inflammation or obstruction. Electrocardiography showed sinus tachycardia.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

1. Which is the most likely cause of this patient’s symptoms?

- Primary hyperparathyroidism

- Malignancy

- Her drug therapy

- Familial hypercalcemic hypocalciuria

In total, her laboratory results were consistent with macrocytic anemia, severe hypercalcemia, and acute kidney injury, and she had generalized symptoms.

Primary hyperparathyroidism

A main cause of hypercalcemia is primary hyperparathyroidism, and this needs to be ruled out. Benign adenomas are the most common cause of primary hyperparathyroidism, and a risk factor for benign adenoma is exposure to therapeutic levels of radiation.3

In hyperparathyroidism, there is an increased secretion of parathyroid hormone (PTH), which has multiple effects including increased reabsorption of calcium from the urine, increased excretion of phosphate, and increased expression of 1,25-hydroxyvitamin D hydroxylase to activate vitamin D. PTH also stimulates osteoclasts to increase their expression of receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B ligand (RANKL), which has a downstream effect on osteoclast precursors to cause bone reabsorption.3

Inherited primary hyperparathyroidism tends to present at a younger age, with multiple overactive parathyroid glands.3 Given our patient’s age, inherited primary hyparathyroidism is thus less likely.

Malignancy

The probability that malignancy is causing the hypercalcemia increases with calcium levels greater than 13 mg/dL. Epidemiologically, in hospitalized patients with hypercalcemia, the source tends to be malignancy.4 Typically, patients who develop hypercalcemia from malignancy have a worse prognosis.5

Solid tumors and leukemias can cause hypercalcemia. The mechanisms include humoral factors secreted by the malignancy, local osteolysis due to tumor invasion of bone, and excessive absorption of calcium due to excess vitamin D produced by malignancies.5 The cancers that most frequently cause an increase in calcium resorption are lung cancer, renal cancer, breast cancer, and multiple myeloma.1

Solid tumors with no bone metastasis and non-Hodgkin lymphoma that release PTH-related protein (PTHrP) cause humoral hypercalcemia in malignancy. The patient is typically in an advanced stage of disease. PTHrP increases serum calcium levels by decreasing the kidney’s ability to excrete calcium and by increasing bone turnover. It has no effect on intestinal absorption because of its inability to stimulate activated vitamin D3. Thus, the increase in systemic calcium comes directly from breakdown of bone and inability to excrete the excess.

PTHrP has a unique role in breast cancer: it is released locally in areas where cancer cells have metastasized to bone, but it does not cause a systemic effect. Bone resorption occurs in areas of metastasis and results from an increase in expression of RANKL and RANK in osteoclasts in response to the effects of PTHrP, leading to an increase in the production of osteoclastic cells.1

Tamoxifen, an endocrine therapy often used in breast cancer, also causes a release of bone-reabsorbing factors from tumor cells, which can partially contribute to hypercalcemia.5

Myeloma cells secrete RANKL, which stimulates osteoclastic activity, and they also release interleukin 6 (IL-6) and activating macrophage inflammatory protein alpha. Serum testing usually shows low or normal intact PTH, PTHrP, and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D.1

Patients with multiple myeloma have a worse prognosis if they have a high red blood cell distribution width, a condition shown to correlate with malnutrition, leading to deficiencies in vitamin B12 and to poor response to treatment.6 Up to 14% of patients with multiple myeloma have vitamin B12 deficiency.7

Our patient’s recent weight loss and severe hypercalcemia raise suspicion of malignancy. Further, her obesity makes proper routine breast examination difficult and thus increases the chance of undiagnosed breast cancer.8 Her decrease in renal function and her anemia complicated by hypercalcemia also raise suspicion of multiple myeloma.

Hypercalcemia due to drug therapy

Thiazide diuretics, lithium, teriparatide, and vitamin A in excessive amounts can raise the serum calcium concentration.5 Our patient was taking a thiazide for hypertension, but her extremely high calcium level places drug-induced hypercalcemia as the sole cause lower on the differential list.

Familial hypercalcemic hypocalciuria

Familial hypercalcemic hypocalciuria is a rare autosomal-dominant cause of hypercalcemia in which the ability of the body (and especially the kidneys) to sense levels of calcium is impaired, leading to a decrease in excretion of calcium in the urine.3 Very high calcium levels are rare in hypercalcemic hypocalciuria.3 In our patient with a corrected calcium concentration of nearly 19 mg/dL, familial hypercalcemic hypocalciuria is very unlikely to be the cause of the hypercalcemia.

WHAT ARE THE NEXT STEPS IN THE WORKUP?

As hypercalcemia has been confirmed, the intact PTH level should be checked to determine whether the patient’s condition is PTH-mediated. If the PTH level is in the upper range of normal or is minimally elevated, primary hyperparathyroidism is likely. Elevated PTH confirms primary hyperparathyroidism. A low-normal or low intact PTH confirms a non-PTH-mediated process, and once this is confirmed, PTHrP levels should be checked. An elevated PTHrP suggests humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy. Serum protein electrophoresis, urine protein electrophoresis, and a serum light chain assay should be performed to rule out multiple myeloma.

Vitamin D toxicity is associated with high concentrations of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D and 25-hydroxyvitamin D metabolites. These levels should be checked in this patient.

Other disorders that cause hypercalcemia are vitamin A toxicity and hyperthyroidism, so vitamin A and thyroid-stimulating hormone levels should also be checked.5

CASE CONTINUED

After further questioning, the patient said that she had had lower back pain about 1 to 2 weeks before coming to the emergency room; her primary care doctor had said the pain was likely from muscle strain. The pain had almost resolved but was still present.

The results of further laboratory testing were as follows:

- Serum PTH 11 pg/mL (15–65)

- PTHrP 3.4 pmol/L (< 2.0)

- Protein electrophoresis showed a monoclonal (M) spike of 0.2 g/dL (0)

- Activated vitamin D < 5 ng/mL (19.9–79.3)

- Vitamin A 7.2 mg/dL (33.1–100)

- Vitamin B12 194 pg/mL (239–931)

- Thyroid-stimulating hormone 1.21 mIU/ L (0.47–4.68

- Free thyroxine 1.27 ng/dL (0.78–2.19)

- Iron 103 µg/dL (37–170)

- Total iron-binding capacity 335 µg/dL (265–497)

- Transferrin 248 mg/dL (206–381)

- Ferritin 66 ng/mL (11.1–264)

- Urine protein (random) 100 mg/dL (0–20)

- Urine microalbumin (random) 5.9 mg/dL (0–1.6)

- Urine creatinine clearance 88.5 mL/min (88–128)

- Urine albumin-creatinine ratio 66.66 mg/g (< 30).

Imaging reports

A nuclear bone scan showed increased bone uptake in the hip and both shoulders, consistent with arthritis, and increased activity in 2 of the lower left ribs, associated with rib fractures secondary to lytic lesions. A skeletal survey at a later date showed multiple well-circumscribed “punched-out” lytic lesions in both forearms and both femurs.

2. What should be the next step in this patient’s management?

- Intravenous (IV) fluids

- Calcitonin

- Bisphosphonate treatment

- Denosumab

- Hemodialysis

Initial treatment of severe hypercalcemia includes the following:

Start IV isotonic fluids at a rate of 150 mL/h (if the patient is making urine) to maintain urine output at more than 100 mL/h. Closely monitor urine output.

Give calcitonin 4 IU/kg in combination with IV fluids to reduce calcium levels within the first 12 to 48 hours of treatment.

Give a bisphosphonate, eg, zoledronic acid 4 mg over 15 minutes, or pamidronate 60 to 90 mg over 2 hours. Zoledronic acid is preferred in malignancy-induced hypercalcemia because it is more potent. Doses should be adjusted in patients with renal failure.

Give denosumab if hypercalcemia is refractory to bisphosphonates, or when bisphosphonates cannot be used in renal failure.9

Hemodialysis is performed in patients who have significant neurologic symptoms irrespective of acute renal insufficiency.

Our patient was started on 0.9% sodium chloride at a rate of 150 mL/h for severe hypercalcemia. Zoledronic acid 4 mg IV was given once. These measures lowered her calcium level and lessened her acute kidney injury.

ADDITIONAL FINDINGS

Urine testing was positive for Bence Jones protein. Immune electrophoresis, performed because of suspicion of multiple myeloma, showed an elevated level of kappa light chains at 806.7 mg/dL (0.33–1.94) and normal lambda light chains at 0.62 mg/dL (0.57–2.63). The immunoglobulin G level was low at 496 mg/dL (610–1,660). In patients with severe hypercalcemia, these results point to a diagnosis of malignancy. Bone marrow aspiration study showed greater than 10% plasma cells, confirming multiple myeloma.

MULTIPLE MYELOMA

The diagnosis of multiple myeloma is based in part on the presence of 10% or more of clonal bone marrow plasma cells10 and of specific end-organ damage (anemia, hypercalcemia, renal insufficiency, or bone lesions).9

Bone marrow clonality can be shown by the ratio of kappa to lambda light chains as detected with immunohistochemistry, immunofluorescence, or flow cytometry.11 The normal ratio is 0.26 to 1.65 for a patient with normal kidney function. In this patient, however, the ratio was 1,301.08 (806.67 kappa to 0.62 lambda), which was extremely out of range. The patient’s bone marrow biopsy results revealed the presence of 15% clonal bone marrow plasma cells.

Multiple myeloma causes osteolytic lesions through increased activation of osteoclast activating factor that stimulates the growth of osteoclast precursors. At the same time, it inhibits osteoblast formation via multiple pathways, including the action of sclerostin.11 Our patient had lytic lesions in 2 left lower ribs and in both forearms and femurs.

Hypercalcemia in multiple myeloma is attributed to 2 main factors: bone breakdown and macrophage overactivation. Multiple myeloma cells increase the release of macrophage inflammatory protein 1-alpha and tumor necrosis factor, which are inflammatory proteins that cause an increase in macrophages, which cause an increase in calcitriol.11 As noted, our patient’s calcium level at presentation was 18.4 mg/dL uncorrected and 18.96 mg/dL corrected.

Cast nephropathy can occur in the distal tubules from the increased free light chains circulating and combining with Tamm-Horsfall protein, which in turn causes obstruction and local inflammation,12 leading to a rise in creatinine levels and resulting in acute kidney injury,12 as in our patient.

TREATMENT CONSIDERATIONS IN MULTIPLE MYELOMA

Our patient was referred to an oncologist for management.

In the management of multiple myeloma, the patient’s quality of life needs to be considered. With the development of new agents to combat the damages of the osteolytic effects, there is hope for improving quality of life.13,14 New agents under study include anabolic agents such as antisclerostin and anti-Dickkopf-1, which promote osteoblastogenesis, leading to bone formation, with the possibility of repairing existing damage.15

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- If hypercalcemia is mild to moderate, consider primary hyperparathyroidism.

- Identify patients with severe symptoms of hypercalcemia such as volume depletion, acute kidney injury, arrhythmia, or seizures.

- Confirm severe cases of hypercalcemia and treat severe cases effectively.

- Severe hypercalcemia may need further investigation into a potential underlying malignancy.

- Sternlicht H, Glezerman IG. Hypercalcemia of malignancy and new treatment options. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2015; 11:1779–1788. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S83681

- Ahmed R, Hashiba K. Reliability of QT intervals as indicators of clinical hypercalcemia. Clin Cardiol 1988; 11(6):395–400. doi:10.1002/clc.4960110607

- Bilezikian JP, Cusano NE, Khan AA, Liu JM, Marcocci C, Bandeira F. Primary hyperparathyroidism. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016; 2:16033. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2016.33

- Kuchay MS, Kaur P, Mishra SK, Mithal A. The changing profile of hypercalcemia in a tertiary care setting in North India: an 18-month retrospective study. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab 2017; 14(2):131–135. doi:10.11138/ccmbm/2017.14.1.131

- Rosner MH, Dalkin AC. Onco-nephrology: the pathophysiology and treatment of malignancy-associated hypercalcemia. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2012; 7(10):1722–1729. doi:10.2215/CJN.02470312

- Ai L, Mu S, Hu Y. Prognostic role of RDW in hematological malignancies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Cell Int 2018; 18:61. doi:10.1186/s12935-018-0558-3

- Baz R, Alemany C, Green R, Hussein MA. Prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency in patients with plasma cell dyscrasias: a retrospective review. Cancer 2004; 101(4):790–795. doi:10.1002/cncr.20441

- Elmore JG, Carney PA, Abraham LA, et al. The association between obesity and screening mammography accuracy. Arch Intern Med 2004; 164(10):1140–1147. doi:10.1001/archinte.164.10.1140

- Gerecke C, Fuhrmann S, Strifler S, Schmidt-Hieber M, Einsele H, Knop S. The diagnosis and treatment of multiple myeloma. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2016; 113(27–28):470–476. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2016.0470

- Rajkumar SV. Multiple myeloma: 2016 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol 2016; 91(7):719–734. doi:10.1002/ajh.24402

- Silbermann R, Roodman GD. Myeloma bone disease: pathophysiology and management. J Bone Oncol 2013; 2(2):59–69. doi:10.1016/j.jbo.2013.04.001

- Doshi M, Lahoti A, Danesh FR, Batuman V, Sanders PW; American Society of Nephrology Onco-Nephrology Forum. Paraprotein-related kidney disease: kidney injury from paraproteins—what determines the site of injury? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2016; 11(12):2288–2294. doi:10.2215/CJN.02560316

- Reece D. Update on the initial therapy of multiple myeloma. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2013. doi:10.1200/EdBook_AM.2013.33.e307

- Nishida H. Bone-targeted agents in multiple myeloma. Hematol Rep 2018; 10(1):7401. doi:10.4081/hr.2018.7401

- Ring ES, Lawson MA, Snowden JA, Jolley I, Chantry AD. New agents in the treatment of myeloma bone disease. Calcif Tissue Int 2018; 102(2):196–209. doi:10.1007/s00223-017-0351-7

- Sternlicht H, Glezerman IG. Hypercalcemia of malignancy and new treatment options. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2015; 11:1779–1788. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S83681

- Ahmed R, Hashiba K. Reliability of QT intervals as indicators of clinical hypercalcemia. Clin Cardiol 1988; 11(6):395–400. doi:10.1002/clc.4960110607

- Bilezikian JP, Cusano NE, Khan AA, Liu JM, Marcocci C, Bandeira F. Primary hyperparathyroidism. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016; 2:16033. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2016.33

- Kuchay MS, Kaur P, Mishra SK, Mithal A. The changing profile of hypercalcemia in a tertiary care setting in North India: an 18-month retrospective study. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab 2017; 14(2):131–135. doi:10.11138/ccmbm/2017.14.1.131

- Rosner MH, Dalkin AC. Onco-nephrology: the pathophysiology and treatment of malignancy-associated hypercalcemia. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2012; 7(10):1722–1729. doi:10.2215/CJN.02470312

- Ai L, Mu S, Hu Y. Prognostic role of RDW in hematological malignancies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Cell Int 2018; 18:61. doi:10.1186/s12935-018-0558-3

- Baz R, Alemany C, Green R, Hussein MA. Prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency in patients with plasma cell dyscrasias: a retrospective review. Cancer 2004; 101(4):790–795. doi:10.1002/cncr.20441

- Elmore JG, Carney PA, Abraham LA, et al. The association between obesity and screening mammography accuracy. Arch Intern Med 2004; 164(10):1140–1147. doi:10.1001/archinte.164.10.1140

- Gerecke C, Fuhrmann S, Strifler S, Schmidt-Hieber M, Einsele H, Knop S. The diagnosis and treatment of multiple myeloma. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2016; 113(27–28):470–476. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2016.0470

- Rajkumar SV. Multiple myeloma: 2016 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol 2016; 91(7):719–734. doi:10.1002/ajh.24402

- Silbermann R, Roodman GD. Myeloma bone disease: pathophysiology and management. J Bone Oncol 2013; 2(2):59–69. doi:10.1016/j.jbo.2013.04.001

- Doshi M, Lahoti A, Danesh FR, Batuman V, Sanders PW; American Society of Nephrology Onco-Nephrology Forum. Paraprotein-related kidney disease: kidney injury from paraproteins—what determines the site of injury? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2016; 11(12):2288–2294. doi:10.2215/CJN.02560316

- Reece D. Update on the initial therapy of multiple myeloma. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2013. doi:10.1200/EdBook_AM.2013.33.e307

- Nishida H. Bone-targeted agents in multiple myeloma. Hematol Rep 2018; 10(1):7401. doi:10.4081/hr.2018.7401

- Ring ES, Lawson MA, Snowden JA, Jolley I, Chantry AD. New agents in the treatment of myeloma bone disease. Calcif Tissue Int 2018; 102(2):196–209. doi:10.1007/s00223-017-0351-7