User login

COVID-19 in pregnant women and the impact on newborns

Clinical question: How does infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in pregnant mothers affect their newborns?

Background: A novel coronavirus, now named SARS-CoV-2 by the World Health Organization (previously referred to as 2019-nCoV), is currently causing a worldwide pandemic. It is believed to have originated in Hubei province, China, but is now rapidly spreading in other countries. Although its effects are most severe in the elderly, SARS-CoV-2 has been infecting younger patients, including pregnant women. The effect of COVID-19, the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2, in pregnant women on their newborn children, is unknown, as is the nature of perinatal transmission of SARS-CoV-2.

Study design: Retrospective analysis.

Setting: Five hospitals in Hubei province, China.

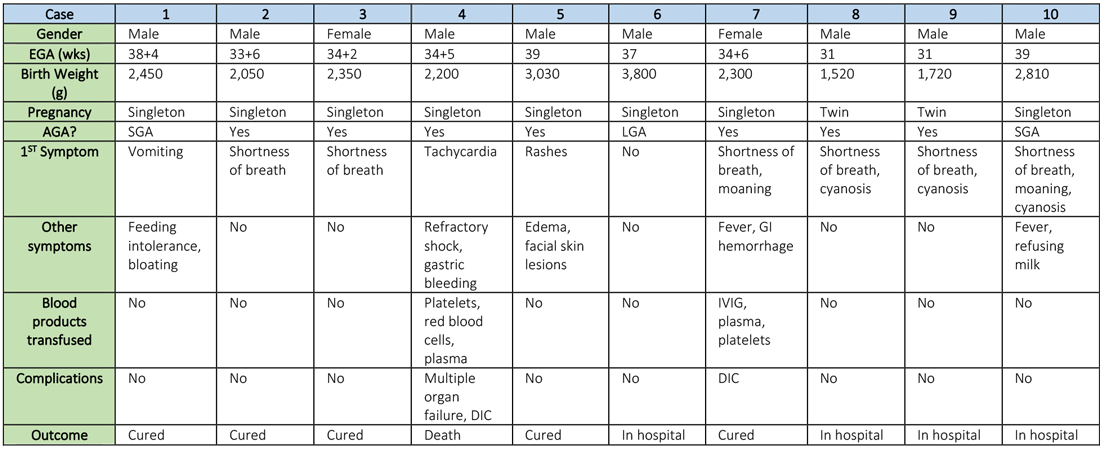

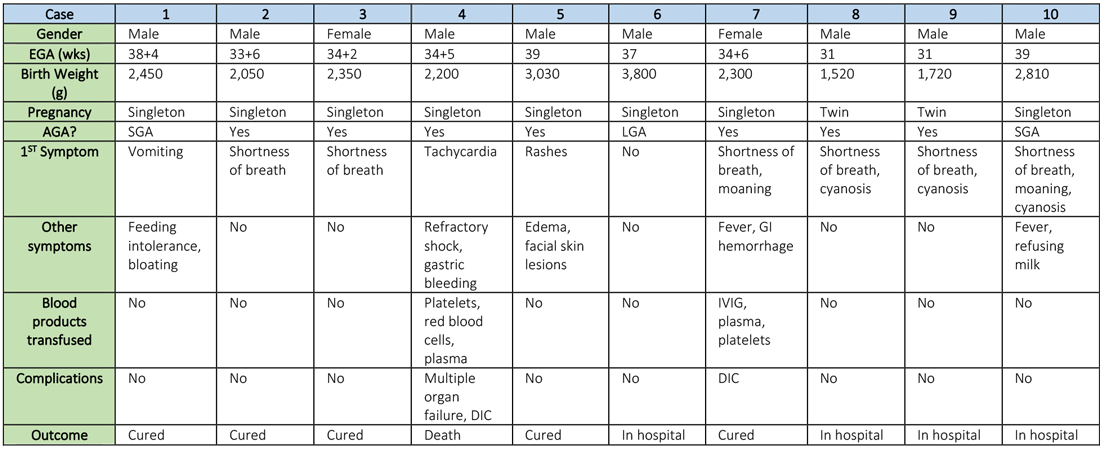

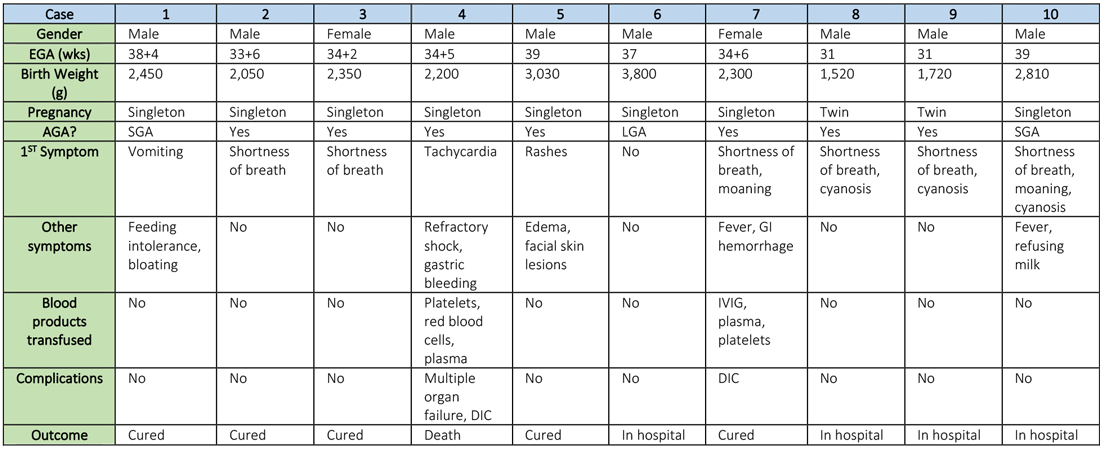

Synopsis: Researchers retrospectively analyzed the clinical features and outcomes of 10 neonates (including two twins) born to nine mothers with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in five hospitals in Hubei province, China, during Jan. 20–Feb. 5, 2020. The mothers were, on average, 30 years of age, but their prior state of health was not described. SARS-CoV-2 infection was confirmed in eight mothers by SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid testing (NAT). The twins’ mother was diagnosed with COVID-19 based on chest CT scan showing viral interstitial pneumonia with other causes of fever and lung infection being “excluded,” despite a negative SARS-CoV-2 NAT test.

Symptoms occurred in the following:

- Before delivery in four mothers, three of whom were treated with oseltamivir (Tamiflu) after delivery.

- On the day of delivery in two mothers, one of whom was treated with oseltamivir and nebulized inhaled interferon after delivery.

- After delivery in three mothers.

Seven mothers delivered by cesarean section and two by vaginal delivery. Prenatal complications included intrauterine distress in six mothers, premature rupture of membranes in three (5-7 hours before onset of true labor), abnormal amniotic fluid in two, “abnormal” umbilical cord in two, and placenta previa in one.

The neonates born to these mothers included two females and eight males; four were full-term and six were premature (degree of prematurity not described). Symptoms first observed in these newborns included shortness of breath (six), fevers (two), tachycardia (one), and vomiting, feeding intolerance, “bloating,” refusing milk, and “gastric bleeding.” Chest radiographs were abnormal in seven newborns, including evidence of “infection” (four), neonatal respiratory distress syndrome (two), and pneumothorax (one). Two cases were described in detail:

- A neonate delivered at 34+5/7 weeks gestational age, was admitted due to shortness of breath and “moaning.” Eight days later, the neonate developed refractory shock, multiple organ failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation requiring transfusions of platelets, red blood cells, and plasma. He died on the ninth day.

- A neonate delivered at 34+6 weeks gestational age and was admitted 25 minutes after delivery due to shortness of breath and “moaning.” He required 2 days of noninvasive support/oxygen therapy and was observed to later develop “oxygen fluctuations” and thrombocytopenia at 3 days of life. The neonate was treated with “respiratory support,” intravenous immunoglobulin, transfusions of platelets and plasma, hydrocortisone (5 mg/kg per day for 6 days), low-dose heparin (2 units/kg per hr for 6 days), and low molecular weight heparin (2 units/kg per hr for 6 days). He was described to be “cured” 15 days later.

All nine neonates underwent pharyngeal swabs for SARS-CoV-2 NAT, and all were negative.

Bottom line: Although data are currently very limited, neonates born to mothers with COVID-19 appear to be at risk for adverse outcomes, including fetal distress, respiratory distress, thrombocytopenia associated with abnormal liver function, and death. There was no evidence of vertical transmission in this study.

Citation: Zhu H et al. Clinical analysis of 10 neonates born to mothers with 2019-nCoV pneumonia. Transl Pediatr. 2020 Feb;9(1):51-60.

Dr. Chang is chief of pediatric hospital medicine at Baystate Children’s Hospital in Springfield, Mass., and associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Massachusetts, also in Springfield.

Clinical question: How does infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in pregnant mothers affect their newborns?

Background: A novel coronavirus, now named SARS-CoV-2 by the World Health Organization (previously referred to as 2019-nCoV), is currently causing a worldwide pandemic. It is believed to have originated in Hubei province, China, but is now rapidly spreading in other countries. Although its effects are most severe in the elderly, SARS-CoV-2 has been infecting younger patients, including pregnant women. The effect of COVID-19, the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2, in pregnant women on their newborn children, is unknown, as is the nature of perinatal transmission of SARS-CoV-2.

Study design: Retrospective analysis.

Setting: Five hospitals in Hubei province, China.

Synopsis: Researchers retrospectively analyzed the clinical features and outcomes of 10 neonates (including two twins) born to nine mothers with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in five hospitals in Hubei province, China, during Jan. 20–Feb. 5, 2020. The mothers were, on average, 30 years of age, but their prior state of health was not described. SARS-CoV-2 infection was confirmed in eight mothers by SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid testing (NAT). The twins’ mother was diagnosed with COVID-19 based on chest CT scan showing viral interstitial pneumonia with other causes of fever and lung infection being “excluded,” despite a negative SARS-CoV-2 NAT test.

Symptoms occurred in the following:

- Before delivery in four mothers, three of whom were treated with oseltamivir (Tamiflu) after delivery.

- On the day of delivery in two mothers, one of whom was treated with oseltamivir and nebulized inhaled interferon after delivery.

- After delivery in three mothers.

Seven mothers delivered by cesarean section and two by vaginal delivery. Prenatal complications included intrauterine distress in six mothers, premature rupture of membranes in three (5-7 hours before onset of true labor), abnormal amniotic fluid in two, “abnormal” umbilical cord in two, and placenta previa in one.

The neonates born to these mothers included two females and eight males; four were full-term and six were premature (degree of prematurity not described). Symptoms first observed in these newborns included shortness of breath (six), fevers (two), tachycardia (one), and vomiting, feeding intolerance, “bloating,” refusing milk, and “gastric bleeding.” Chest radiographs were abnormal in seven newborns, including evidence of “infection” (four), neonatal respiratory distress syndrome (two), and pneumothorax (one). Two cases were described in detail:

- A neonate delivered at 34+5/7 weeks gestational age, was admitted due to shortness of breath and “moaning.” Eight days later, the neonate developed refractory shock, multiple organ failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation requiring transfusions of platelets, red blood cells, and plasma. He died on the ninth day.

- A neonate delivered at 34+6 weeks gestational age and was admitted 25 minutes after delivery due to shortness of breath and “moaning.” He required 2 days of noninvasive support/oxygen therapy and was observed to later develop “oxygen fluctuations” and thrombocytopenia at 3 days of life. The neonate was treated with “respiratory support,” intravenous immunoglobulin, transfusions of platelets and plasma, hydrocortisone (5 mg/kg per day for 6 days), low-dose heparin (2 units/kg per hr for 6 days), and low molecular weight heparin (2 units/kg per hr for 6 days). He was described to be “cured” 15 days later.

All nine neonates underwent pharyngeal swabs for SARS-CoV-2 NAT, and all were negative.

Bottom line: Although data are currently very limited, neonates born to mothers with COVID-19 appear to be at risk for adverse outcomes, including fetal distress, respiratory distress, thrombocytopenia associated with abnormal liver function, and death. There was no evidence of vertical transmission in this study.

Citation: Zhu H et al. Clinical analysis of 10 neonates born to mothers with 2019-nCoV pneumonia. Transl Pediatr. 2020 Feb;9(1):51-60.

Dr. Chang is chief of pediatric hospital medicine at Baystate Children’s Hospital in Springfield, Mass., and associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Massachusetts, also in Springfield.

Clinical question: How does infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in pregnant mothers affect their newborns?

Background: A novel coronavirus, now named SARS-CoV-2 by the World Health Organization (previously referred to as 2019-nCoV), is currently causing a worldwide pandemic. It is believed to have originated in Hubei province, China, but is now rapidly spreading in other countries. Although its effects are most severe in the elderly, SARS-CoV-2 has been infecting younger patients, including pregnant women. The effect of COVID-19, the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2, in pregnant women on their newborn children, is unknown, as is the nature of perinatal transmission of SARS-CoV-2.

Study design: Retrospective analysis.

Setting: Five hospitals in Hubei province, China.

Synopsis: Researchers retrospectively analyzed the clinical features and outcomes of 10 neonates (including two twins) born to nine mothers with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in five hospitals in Hubei province, China, during Jan. 20–Feb. 5, 2020. The mothers were, on average, 30 years of age, but their prior state of health was not described. SARS-CoV-2 infection was confirmed in eight mothers by SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid testing (NAT). The twins’ mother was diagnosed with COVID-19 based on chest CT scan showing viral interstitial pneumonia with other causes of fever and lung infection being “excluded,” despite a negative SARS-CoV-2 NAT test.

Symptoms occurred in the following:

- Before delivery in four mothers, three of whom were treated with oseltamivir (Tamiflu) after delivery.

- On the day of delivery in two mothers, one of whom was treated with oseltamivir and nebulized inhaled interferon after delivery.

- After delivery in three mothers.

Seven mothers delivered by cesarean section and two by vaginal delivery. Prenatal complications included intrauterine distress in six mothers, premature rupture of membranes in three (5-7 hours before onset of true labor), abnormal amniotic fluid in two, “abnormal” umbilical cord in two, and placenta previa in one.

The neonates born to these mothers included two females and eight males; four were full-term and six were premature (degree of prematurity not described). Symptoms first observed in these newborns included shortness of breath (six), fevers (two), tachycardia (one), and vomiting, feeding intolerance, “bloating,” refusing milk, and “gastric bleeding.” Chest radiographs were abnormal in seven newborns, including evidence of “infection” (four), neonatal respiratory distress syndrome (two), and pneumothorax (one). Two cases were described in detail:

- A neonate delivered at 34+5/7 weeks gestational age, was admitted due to shortness of breath and “moaning.” Eight days later, the neonate developed refractory shock, multiple organ failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation requiring transfusions of platelets, red blood cells, and plasma. He died on the ninth day.

- A neonate delivered at 34+6 weeks gestational age and was admitted 25 minutes after delivery due to shortness of breath and “moaning.” He required 2 days of noninvasive support/oxygen therapy and was observed to later develop “oxygen fluctuations” and thrombocytopenia at 3 days of life. The neonate was treated with “respiratory support,” intravenous immunoglobulin, transfusions of platelets and plasma, hydrocortisone (5 mg/kg per day for 6 days), low-dose heparin (2 units/kg per hr for 6 days), and low molecular weight heparin (2 units/kg per hr for 6 days). He was described to be “cured” 15 days later.

All nine neonates underwent pharyngeal swabs for SARS-CoV-2 NAT, and all were negative.

Bottom line: Although data are currently very limited, neonates born to mothers with COVID-19 appear to be at risk for adverse outcomes, including fetal distress, respiratory distress, thrombocytopenia associated with abnormal liver function, and death. There was no evidence of vertical transmission in this study.

Citation: Zhu H et al. Clinical analysis of 10 neonates born to mothers with 2019-nCoV pneumonia. Transl Pediatr. 2020 Feb;9(1):51-60.

Dr. Chang is chief of pediatric hospital medicine at Baystate Children’s Hospital in Springfield, Mass., and associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Massachusetts, also in Springfield.

The rapidly disappearing community pediatric inpatient unit

Greed kills babies. Children’s lives matter. Children over profit.

These were the slogans proclaimed by signs carried by protesters outside of MedStar Franklin Square Medical Center in Baltimore in early May of 2018 to protest the closure of the dedicated pediatric emergency department and inpatient pediatric unit.

But administrators at Franklin Square Medical Center had made their decision long before the glue had dried on the signs, and the protests of patients and community officials fell on deaf ears. Eight doctors and 30 other staff had already lost their jobs, including the chair of pediatrics, Scott Krugman, MD.1

And this was just another drop in a slow ooze of pediatric inpatient units based in community hospitals that have seen the ax fall on what was thought to be a vital medical resource for their communities – yet not vital enough to survive its lack of profitability. From Taunton, Mass., to Chicago, Ill., to rural Tennessee, pediatric inpatient units in community hospitals have failed to even flirt with breaking even, let alone show profitability. Many community pediatric inpatient units are saddled with rock-bottom reimbursements offered by state Medicaid programs, the overwhelmingly prevalent payer for pediatric hospitalizations, which is compounded by the seasonality and unpredictability of pediatric inpatient volumes, so many have seen a glowing red bottom line lead to their demise.

What does this mean for pediatric health in underserved and rural communities? The closure of the pediatric inpatient unit at MedStar Franklin Square Medical Center meant the loss of physicians and nurses staffing the child protection team helping to assist the local district attorney in child abuse cases. Sometimes described as “secondary care,” community pediatric hospitalists also serve as a link between primary care providers and tertiary care subspecialists; they can serve as pediatric generalists throughout a hospital and provide newborn nursery care, delivery room resuscitations, ED consultations, procedural sedations, psychiatric unit support, surgical comanagement, and informal or formal outpatient consultations.2 Losing even a small inpatient pediatric unit can have a ripple effect on inpatient and outpatient pediatric services in a health system and community.

For patients and their caregivers, the loss of pediatric inpatient services in their community hospital can erect additional hurdles to appropriate health care. The need to travel longer distances to urban centers or even the other side of town can be challenging given the difficulties posed by long distances, traffic congestion, public transportation, or just parking.3 For patients suffering from longer hospitalizations caused by medical complexity or chronic illnesses, traveling long distances can exacerbate the caregiver stress from attempting to care for a family at home while participating in the care of a hospitalized child. Longer travel times can also worsen family stress by increasing a caregiver’s absence from home and increased nonmedical expenses, not to mention loss of wages.4 Comfort levels with inpatient providers can also suffer because most pediatric units in community hospitals are staffed by either community general pediatricians or very small pediatric hospitalist groups, which breeds familiarity with frequently admitted patients and their caregivers. This familiarity can be lacking in large academic centers, with confusing and ever-rotating teams of academic hospitalists, residents, and medical students.5

What is driving the slow drumbeat of pediatric inpatient unit closures? On a macroeconomic scale, pediatric hospitalizations have been dropping yearly, driven down by immunizations (despite the best efforts of certain celebrities), antibiotic stewardship, and improved access to outpatient care. In 2006, there were 6.6 million hospitalizations for children aged 17 years and younger,6 but by 2012 this had dropped to 5.9 million hospitalizations.7 In the same age group, the rate of hospitalization from the ED dropped from 4.4% in 2006 to 3.2% in 2015.8

On a hospital level, the presence of multiple small pediatric units in a region may not make sense from a cost standpoint, and a larger, merged unit may provide higher quality because of its higher volumes. On a state and local level, alternative payment models have been implemented with the best of intentions but have led administrators at community general hospitals to look at pediatric units as the lowest hanging money-losing fruit in their efforts to survive a brave new world of hospital payment.

The most extreme (or advanced, depending on your viewpoint) model is in Maryland: Since 2014, acute care hospitals have been only able to receive a fixed amount of revenue from all payers, including Medicare, Medicaid, and commercial insurers.9 Known as an all-payer global budget, it incentivizes lowering unnecessary costs of care, such as readmissions, but also encourages cauterization of cost centers hemorrhaging money – such as inpatient pediatrics. Even the venerable Johns Hopkins Children’s Center has seen its profitability pale in comparison to the expansion team Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital in St. Petersburg, Fla., which is the second-most profitable hospital in the Hopkins system, only edged out by Sibley Memorial Hospital – which also sports an out-of-state location in the District of Columbia.10

But all hope is not lost for your comfy local pediatric inpatient unit. In other states and regions where a more favorable (to hospitals) payer mix exists, large pediatric hospitals are still engaged in turf battles with other local competitors to grab market share. In these regions, community pediatric units have survived by partnering with large pediatric institutions, either through affiliations or wholesale transplantation of the larger pediatric institution’s providers, nurses, and EHRs into essentially what is a leased floor. In addition, large pediatric institutions that participate in capitated models such as accountable care organizations have paradoxically found it financially favorable to direct “bread-and-butter” pediatric hospitalizations to community pediatric units, which often provide the same care at a lower cost.

Utilizing community inpatient pediatric units was “initially … a means of expanding their market share and ‘downstream’ revenue from transfers, but more commonly now [is] a way of alleviating the costs associated with admitting low to moderate acuity patients to the main tertiary sites,” said Francisco Alvarez, MD, associate chief of Regional Pediatric Hospital Medicine Programs at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital in Palo Alto, Calif. “The cost of care provided by pediatric hospitals has always been higher than the average cost for nonpediatric hospitals in regard to caring for pediatric patients due to their highly skilled specialties and services. These have become more scrutinized by private and government insurance plans and, in some cases, have led to lower reimbursements and therefore a lower or deficient net revenue for certain patient populations.”

For community pediatric hospitalists, the shifting sands of reimbursement on which pediatric inpatient care is built can be a motion illness–inducing experience. In addition to concerns over community health care, job security, and population health, care provided in community hospitals can often be subtly undercut by tertiary and quaternary care pediatric hospitals.

“The focus of pediatric residency programs in freestanding children’s hospitals has created a situation where new pediatricians have less opportunity to develop respect for community pediatric hospital medicine,” said Beth Natt, MD, director of pediatric hospital medicine in the Regional Programs at Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, Hartford. “We are the nameless ‘OSH,’ the place that gets ‘Monday-morning quarterbacked’ in resident morning reports without having a voice at the table. Add this to residents learning ‘only’ protocolized care as opposed to a spectrum of appropriate care, and we create a culture of ‘wrong and right’ with the backward nonprotocol driven community docs looking like they are practicing medicine in the Wild West.”

What’s a community pediatric hospitalist to do, faced with an uncertain future and diminishing respect? Continuing to partner with local pediatric providers, community leaders, and local health care advocacy groups will help to enmesh inpatient providers in the fabric of a community’s health care. But making the value case to hospital administrators is critical for community pediatric hospitalists, as adult hospitalists realized soon after the inception of the hospitalist field.

Goals valued by hospital administrators are pursued on a daily basis by community pediatric hospitalists, and these successes need to be brought to light. Achieving value and quality metrics, pursuing high-value care, reducing readmission rates, championing EHRs, and improving documentation are goals that community pediatric hospitalists and hospital administrators can work toward together.11 By pursuing and sharing success in meeting these shared goals, perhaps the local community pediatric inpatient unit can survive – and thrive.

As for Dr. Krugman, he has moved on and is soon to be gainfully employed again. But he continues to be focused, as always, on the health of his patients.

“What are we going to do to take care of kids in their own communities?” Dr. Krugman asked. “It’s going to be an increasing challenge over the next decade due to the consolidation of children’s hospitals and low payments, especially for hospitals that are adult-focused. Unless we find a way to pay for pediatric care as a country.”

Dr. Chang is a pediatric hospitalist at Baystate Children’s Hospital in Springfield, Mass., and is the pediatric editor of The Hospitalist.

References

1. McDaniels A. (2018). Protesters denounce reduction in pediatric services at Baltimore’s MedStar Franklin Square hospital. Baltimore Sun. Available at: http://www.baltimoresun.com/health/health-care/bs-hs-franklin-square-hospital-protest-20180508-story.html.

2. Roberts KB. Pediatric hospitalists in community hospitals: Hospital-based generalists with expanded roles. Hosp Pediatr. 2015 May;5(5):290-2.

3. Georgia Health News. (2018). A hospital crisis is killing rural communities. This state is ‘Ground Zero’. Available at: http://www.georgiahealthnews.com/2017/09/hospital-crisis-killing-rural-communities-state-ground-zero/.

4. DiFazio RL et al. Non-medical out-of-pocket expenses incurred by families during their child’s hospitalization. J Child Health Care. 2013 Sep;17(3):230-41.

5. Gunderman R. Hospitalist and the decline of comprehensive care. N Engl J Med. 2016 Sep 15; 375(11):1011-3.

6. Statistical Brief #56. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb56.jsp.

7. Overview of Hospital Stays for Children in the United States, 2012 #187. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb187-Hospital-Stays-Children-2012.jsp.

8. Trends in Hospital Inpatient Stays by Age and Payer, 2000-2015 #235. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb235-Inpatient-Stays-Age-Payer-Trends.jsp.

9. Maryland All-Payer Model | Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation. (2018). Retrieved from https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/Maryland-All-Payer-Model/.

10. The effects of Maryland’s unique health care system. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.axios.com/johns-hopkins-finances-maryland-1518553853-722c2195-731e-4e02-ab1e-94e4211ba945.html.

11. The Increasing Need for Hospitalist Programs to Demonstrate Value | SCP. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.schumacherclinical.com/providers/blog/the-increasing-need-for-hospitalist-programs-to-demonstrate-value.

Greed kills babies. Children’s lives matter. Children over profit.

These were the slogans proclaimed by signs carried by protesters outside of MedStar Franklin Square Medical Center in Baltimore in early May of 2018 to protest the closure of the dedicated pediatric emergency department and inpatient pediatric unit.

But administrators at Franklin Square Medical Center had made their decision long before the glue had dried on the signs, and the protests of patients and community officials fell on deaf ears. Eight doctors and 30 other staff had already lost their jobs, including the chair of pediatrics, Scott Krugman, MD.1

And this was just another drop in a slow ooze of pediatric inpatient units based in community hospitals that have seen the ax fall on what was thought to be a vital medical resource for their communities – yet not vital enough to survive its lack of profitability. From Taunton, Mass., to Chicago, Ill., to rural Tennessee, pediatric inpatient units in community hospitals have failed to even flirt with breaking even, let alone show profitability. Many community pediatric inpatient units are saddled with rock-bottom reimbursements offered by state Medicaid programs, the overwhelmingly prevalent payer for pediatric hospitalizations, which is compounded by the seasonality and unpredictability of pediatric inpatient volumes, so many have seen a glowing red bottom line lead to their demise.

What does this mean for pediatric health in underserved and rural communities? The closure of the pediatric inpatient unit at MedStar Franklin Square Medical Center meant the loss of physicians and nurses staffing the child protection team helping to assist the local district attorney in child abuse cases. Sometimes described as “secondary care,” community pediatric hospitalists also serve as a link between primary care providers and tertiary care subspecialists; they can serve as pediatric generalists throughout a hospital and provide newborn nursery care, delivery room resuscitations, ED consultations, procedural sedations, psychiatric unit support, surgical comanagement, and informal or formal outpatient consultations.2 Losing even a small inpatient pediatric unit can have a ripple effect on inpatient and outpatient pediatric services in a health system and community.

For patients and their caregivers, the loss of pediatric inpatient services in their community hospital can erect additional hurdles to appropriate health care. The need to travel longer distances to urban centers or even the other side of town can be challenging given the difficulties posed by long distances, traffic congestion, public transportation, or just parking.3 For patients suffering from longer hospitalizations caused by medical complexity or chronic illnesses, traveling long distances can exacerbate the caregiver stress from attempting to care for a family at home while participating in the care of a hospitalized child. Longer travel times can also worsen family stress by increasing a caregiver’s absence from home and increased nonmedical expenses, not to mention loss of wages.4 Comfort levels with inpatient providers can also suffer because most pediatric units in community hospitals are staffed by either community general pediatricians or very small pediatric hospitalist groups, which breeds familiarity with frequently admitted patients and their caregivers. This familiarity can be lacking in large academic centers, with confusing and ever-rotating teams of academic hospitalists, residents, and medical students.5

What is driving the slow drumbeat of pediatric inpatient unit closures? On a macroeconomic scale, pediatric hospitalizations have been dropping yearly, driven down by immunizations (despite the best efforts of certain celebrities), antibiotic stewardship, and improved access to outpatient care. In 2006, there were 6.6 million hospitalizations for children aged 17 years and younger,6 but by 2012 this had dropped to 5.9 million hospitalizations.7 In the same age group, the rate of hospitalization from the ED dropped from 4.4% in 2006 to 3.2% in 2015.8

On a hospital level, the presence of multiple small pediatric units in a region may not make sense from a cost standpoint, and a larger, merged unit may provide higher quality because of its higher volumes. On a state and local level, alternative payment models have been implemented with the best of intentions but have led administrators at community general hospitals to look at pediatric units as the lowest hanging money-losing fruit in their efforts to survive a brave new world of hospital payment.

The most extreme (or advanced, depending on your viewpoint) model is in Maryland: Since 2014, acute care hospitals have been only able to receive a fixed amount of revenue from all payers, including Medicare, Medicaid, and commercial insurers.9 Known as an all-payer global budget, it incentivizes lowering unnecessary costs of care, such as readmissions, but also encourages cauterization of cost centers hemorrhaging money – such as inpatient pediatrics. Even the venerable Johns Hopkins Children’s Center has seen its profitability pale in comparison to the expansion team Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital in St. Petersburg, Fla., which is the second-most profitable hospital in the Hopkins system, only edged out by Sibley Memorial Hospital – which also sports an out-of-state location in the District of Columbia.10

But all hope is not lost for your comfy local pediatric inpatient unit. In other states and regions where a more favorable (to hospitals) payer mix exists, large pediatric hospitals are still engaged in turf battles with other local competitors to grab market share. In these regions, community pediatric units have survived by partnering with large pediatric institutions, either through affiliations or wholesale transplantation of the larger pediatric institution’s providers, nurses, and EHRs into essentially what is a leased floor. In addition, large pediatric institutions that participate in capitated models such as accountable care organizations have paradoxically found it financially favorable to direct “bread-and-butter” pediatric hospitalizations to community pediatric units, which often provide the same care at a lower cost.

Utilizing community inpatient pediatric units was “initially … a means of expanding their market share and ‘downstream’ revenue from transfers, but more commonly now [is] a way of alleviating the costs associated with admitting low to moderate acuity patients to the main tertiary sites,” said Francisco Alvarez, MD, associate chief of Regional Pediatric Hospital Medicine Programs at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital in Palo Alto, Calif. “The cost of care provided by pediatric hospitals has always been higher than the average cost for nonpediatric hospitals in regard to caring for pediatric patients due to their highly skilled specialties and services. These have become more scrutinized by private and government insurance plans and, in some cases, have led to lower reimbursements and therefore a lower or deficient net revenue for certain patient populations.”

For community pediatric hospitalists, the shifting sands of reimbursement on which pediatric inpatient care is built can be a motion illness–inducing experience. In addition to concerns over community health care, job security, and population health, care provided in community hospitals can often be subtly undercut by tertiary and quaternary care pediatric hospitals.

“The focus of pediatric residency programs in freestanding children’s hospitals has created a situation where new pediatricians have less opportunity to develop respect for community pediatric hospital medicine,” said Beth Natt, MD, director of pediatric hospital medicine in the Regional Programs at Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, Hartford. “We are the nameless ‘OSH,’ the place that gets ‘Monday-morning quarterbacked’ in resident morning reports without having a voice at the table. Add this to residents learning ‘only’ protocolized care as opposed to a spectrum of appropriate care, and we create a culture of ‘wrong and right’ with the backward nonprotocol driven community docs looking like they are practicing medicine in the Wild West.”

What’s a community pediatric hospitalist to do, faced with an uncertain future and diminishing respect? Continuing to partner with local pediatric providers, community leaders, and local health care advocacy groups will help to enmesh inpatient providers in the fabric of a community’s health care. But making the value case to hospital administrators is critical for community pediatric hospitalists, as adult hospitalists realized soon after the inception of the hospitalist field.

Goals valued by hospital administrators are pursued on a daily basis by community pediatric hospitalists, and these successes need to be brought to light. Achieving value and quality metrics, pursuing high-value care, reducing readmission rates, championing EHRs, and improving documentation are goals that community pediatric hospitalists and hospital administrators can work toward together.11 By pursuing and sharing success in meeting these shared goals, perhaps the local community pediatric inpatient unit can survive – and thrive.

As for Dr. Krugman, he has moved on and is soon to be gainfully employed again. But he continues to be focused, as always, on the health of his patients.

“What are we going to do to take care of kids in their own communities?” Dr. Krugman asked. “It’s going to be an increasing challenge over the next decade due to the consolidation of children’s hospitals and low payments, especially for hospitals that are adult-focused. Unless we find a way to pay for pediatric care as a country.”

Dr. Chang is a pediatric hospitalist at Baystate Children’s Hospital in Springfield, Mass., and is the pediatric editor of The Hospitalist.

References

1. McDaniels A. (2018). Protesters denounce reduction in pediatric services at Baltimore’s MedStar Franklin Square hospital. Baltimore Sun. Available at: http://www.baltimoresun.com/health/health-care/bs-hs-franklin-square-hospital-protest-20180508-story.html.

2. Roberts KB. Pediatric hospitalists in community hospitals: Hospital-based generalists with expanded roles. Hosp Pediatr. 2015 May;5(5):290-2.

3. Georgia Health News. (2018). A hospital crisis is killing rural communities. This state is ‘Ground Zero’. Available at: http://www.georgiahealthnews.com/2017/09/hospital-crisis-killing-rural-communities-state-ground-zero/.

4. DiFazio RL et al. Non-medical out-of-pocket expenses incurred by families during their child’s hospitalization. J Child Health Care. 2013 Sep;17(3):230-41.

5. Gunderman R. Hospitalist and the decline of comprehensive care. N Engl J Med. 2016 Sep 15; 375(11):1011-3.

6. Statistical Brief #56. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb56.jsp.

7. Overview of Hospital Stays for Children in the United States, 2012 #187. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb187-Hospital-Stays-Children-2012.jsp.

8. Trends in Hospital Inpatient Stays by Age and Payer, 2000-2015 #235. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb235-Inpatient-Stays-Age-Payer-Trends.jsp.

9. Maryland All-Payer Model | Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation. (2018). Retrieved from https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/Maryland-All-Payer-Model/.

10. The effects of Maryland’s unique health care system. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.axios.com/johns-hopkins-finances-maryland-1518553853-722c2195-731e-4e02-ab1e-94e4211ba945.html.

11. The Increasing Need for Hospitalist Programs to Demonstrate Value | SCP. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.schumacherclinical.com/providers/blog/the-increasing-need-for-hospitalist-programs-to-demonstrate-value.

Greed kills babies. Children’s lives matter. Children over profit.

These were the slogans proclaimed by signs carried by protesters outside of MedStar Franklin Square Medical Center in Baltimore in early May of 2018 to protest the closure of the dedicated pediatric emergency department and inpatient pediatric unit.

But administrators at Franklin Square Medical Center had made their decision long before the glue had dried on the signs, and the protests of patients and community officials fell on deaf ears. Eight doctors and 30 other staff had already lost their jobs, including the chair of pediatrics, Scott Krugman, MD.1

And this was just another drop in a slow ooze of pediatric inpatient units based in community hospitals that have seen the ax fall on what was thought to be a vital medical resource for their communities – yet not vital enough to survive its lack of profitability. From Taunton, Mass., to Chicago, Ill., to rural Tennessee, pediatric inpatient units in community hospitals have failed to even flirt with breaking even, let alone show profitability. Many community pediatric inpatient units are saddled with rock-bottom reimbursements offered by state Medicaid programs, the overwhelmingly prevalent payer for pediatric hospitalizations, which is compounded by the seasonality and unpredictability of pediatric inpatient volumes, so many have seen a glowing red bottom line lead to their demise.

What does this mean for pediatric health in underserved and rural communities? The closure of the pediatric inpatient unit at MedStar Franklin Square Medical Center meant the loss of physicians and nurses staffing the child protection team helping to assist the local district attorney in child abuse cases. Sometimes described as “secondary care,” community pediatric hospitalists also serve as a link between primary care providers and tertiary care subspecialists; they can serve as pediatric generalists throughout a hospital and provide newborn nursery care, delivery room resuscitations, ED consultations, procedural sedations, psychiatric unit support, surgical comanagement, and informal or formal outpatient consultations.2 Losing even a small inpatient pediatric unit can have a ripple effect on inpatient and outpatient pediatric services in a health system and community.

For patients and their caregivers, the loss of pediatric inpatient services in their community hospital can erect additional hurdles to appropriate health care. The need to travel longer distances to urban centers or even the other side of town can be challenging given the difficulties posed by long distances, traffic congestion, public transportation, or just parking.3 For patients suffering from longer hospitalizations caused by medical complexity or chronic illnesses, traveling long distances can exacerbate the caregiver stress from attempting to care for a family at home while participating in the care of a hospitalized child. Longer travel times can also worsen family stress by increasing a caregiver’s absence from home and increased nonmedical expenses, not to mention loss of wages.4 Comfort levels with inpatient providers can also suffer because most pediatric units in community hospitals are staffed by either community general pediatricians or very small pediatric hospitalist groups, which breeds familiarity with frequently admitted patients and their caregivers. This familiarity can be lacking in large academic centers, with confusing and ever-rotating teams of academic hospitalists, residents, and medical students.5

What is driving the slow drumbeat of pediatric inpatient unit closures? On a macroeconomic scale, pediatric hospitalizations have been dropping yearly, driven down by immunizations (despite the best efforts of certain celebrities), antibiotic stewardship, and improved access to outpatient care. In 2006, there were 6.6 million hospitalizations for children aged 17 years and younger,6 but by 2012 this had dropped to 5.9 million hospitalizations.7 In the same age group, the rate of hospitalization from the ED dropped from 4.4% in 2006 to 3.2% in 2015.8

On a hospital level, the presence of multiple small pediatric units in a region may not make sense from a cost standpoint, and a larger, merged unit may provide higher quality because of its higher volumes. On a state and local level, alternative payment models have been implemented with the best of intentions but have led administrators at community general hospitals to look at pediatric units as the lowest hanging money-losing fruit in their efforts to survive a brave new world of hospital payment.

The most extreme (or advanced, depending on your viewpoint) model is in Maryland: Since 2014, acute care hospitals have been only able to receive a fixed amount of revenue from all payers, including Medicare, Medicaid, and commercial insurers.9 Known as an all-payer global budget, it incentivizes lowering unnecessary costs of care, such as readmissions, but also encourages cauterization of cost centers hemorrhaging money – such as inpatient pediatrics. Even the venerable Johns Hopkins Children’s Center has seen its profitability pale in comparison to the expansion team Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital in St. Petersburg, Fla., which is the second-most profitable hospital in the Hopkins system, only edged out by Sibley Memorial Hospital – which also sports an out-of-state location in the District of Columbia.10

But all hope is not lost for your comfy local pediatric inpatient unit. In other states and regions where a more favorable (to hospitals) payer mix exists, large pediatric hospitals are still engaged in turf battles with other local competitors to grab market share. In these regions, community pediatric units have survived by partnering with large pediatric institutions, either through affiliations or wholesale transplantation of the larger pediatric institution’s providers, nurses, and EHRs into essentially what is a leased floor. In addition, large pediatric institutions that participate in capitated models such as accountable care organizations have paradoxically found it financially favorable to direct “bread-and-butter” pediatric hospitalizations to community pediatric units, which often provide the same care at a lower cost.

Utilizing community inpatient pediatric units was “initially … a means of expanding their market share and ‘downstream’ revenue from transfers, but more commonly now [is] a way of alleviating the costs associated with admitting low to moderate acuity patients to the main tertiary sites,” said Francisco Alvarez, MD, associate chief of Regional Pediatric Hospital Medicine Programs at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital in Palo Alto, Calif. “The cost of care provided by pediatric hospitals has always been higher than the average cost for nonpediatric hospitals in regard to caring for pediatric patients due to their highly skilled specialties and services. These have become more scrutinized by private and government insurance plans and, in some cases, have led to lower reimbursements and therefore a lower or deficient net revenue for certain patient populations.”

For community pediatric hospitalists, the shifting sands of reimbursement on which pediatric inpatient care is built can be a motion illness–inducing experience. In addition to concerns over community health care, job security, and population health, care provided in community hospitals can often be subtly undercut by tertiary and quaternary care pediatric hospitals.

“The focus of pediatric residency programs in freestanding children’s hospitals has created a situation where new pediatricians have less opportunity to develop respect for community pediatric hospital medicine,” said Beth Natt, MD, director of pediatric hospital medicine in the Regional Programs at Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, Hartford. “We are the nameless ‘OSH,’ the place that gets ‘Monday-morning quarterbacked’ in resident morning reports without having a voice at the table. Add this to residents learning ‘only’ protocolized care as opposed to a spectrum of appropriate care, and we create a culture of ‘wrong and right’ with the backward nonprotocol driven community docs looking like they are practicing medicine in the Wild West.”

What’s a community pediatric hospitalist to do, faced with an uncertain future and diminishing respect? Continuing to partner with local pediatric providers, community leaders, and local health care advocacy groups will help to enmesh inpatient providers in the fabric of a community’s health care. But making the value case to hospital administrators is critical for community pediatric hospitalists, as adult hospitalists realized soon after the inception of the hospitalist field.

Goals valued by hospital administrators are pursued on a daily basis by community pediatric hospitalists, and these successes need to be brought to light. Achieving value and quality metrics, pursuing high-value care, reducing readmission rates, championing EHRs, and improving documentation are goals that community pediatric hospitalists and hospital administrators can work toward together.11 By pursuing and sharing success in meeting these shared goals, perhaps the local community pediatric inpatient unit can survive – and thrive.

As for Dr. Krugman, he has moved on and is soon to be gainfully employed again. But he continues to be focused, as always, on the health of his patients.

“What are we going to do to take care of kids in their own communities?” Dr. Krugman asked. “It’s going to be an increasing challenge over the next decade due to the consolidation of children’s hospitals and low payments, especially for hospitals that are adult-focused. Unless we find a way to pay for pediatric care as a country.”

Dr. Chang is a pediatric hospitalist at Baystate Children’s Hospital in Springfield, Mass., and is the pediatric editor of The Hospitalist.

References

1. McDaniels A. (2018). Protesters denounce reduction in pediatric services at Baltimore’s MedStar Franklin Square hospital. Baltimore Sun. Available at: http://www.baltimoresun.com/health/health-care/bs-hs-franklin-square-hospital-protest-20180508-story.html.

2. Roberts KB. Pediatric hospitalists in community hospitals: Hospital-based generalists with expanded roles. Hosp Pediatr. 2015 May;5(5):290-2.

3. Georgia Health News. (2018). A hospital crisis is killing rural communities. This state is ‘Ground Zero’. Available at: http://www.georgiahealthnews.com/2017/09/hospital-crisis-killing-rural-communities-state-ground-zero/.

4. DiFazio RL et al. Non-medical out-of-pocket expenses incurred by families during their child’s hospitalization. J Child Health Care. 2013 Sep;17(3):230-41.

5. Gunderman R. Hospitalist and the decline of comprehensive care. N Engl J Med. 2016 Sep 15; 375(11):1011-3.

6. Statistical Brief #56. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb56.jsp.

7. Overview of Hospital Stays for Children in the United States, 2012 #187. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb187-Hospital-Stays-Children-2012.jsp.

8. Trends in Hospital Inpatient Stays by Age and Payer, 2000-2015 #235. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb235-Inpatient-Stays-Age-Payer-Trends.jsp.

9. Maryland All-Payer Model | Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation. (2018). Retrieved from https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/Maryland-All-Payer-Model/.

10. The effects of Maryland’s unique health care system. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.axios.com/johns-hopkins-finances-maryland-1518553853-722c2195-731e-4e02-ab1e-94e4211ba945.html.

11. The Increasing Need for Hospitalist Programs to Demonstrate Value | SCP. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.schumacherclinical.com/providers/blog/the-increasing-need-for-hospitalist-programs-to-demonstrate-value.

A clinical pathway to standardize use of maintenance IV fluids

Clinical question

Can an evidence-based clinical pathway improve adherence to recent recommendations to use isotonic solutions for maintenance intravenous fluids in hospitalized children?

Background

The traditional teaching regarding composition of maintenance intravenous fluids (IVF) in children has been based on the Holliday-Segar method.1 Since its publication in Pediatrics in 1957, concerns have been raised regarding the risk of iatrogenic hyponatremia caused by giving hypotonic fluids determined by this method,2 especially in patients with an elevated risk of increased antidiuretic hormone (ADH) secretion.3 Multiple recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses have confirmed that isotonic IVF reduces the risk of hyponatremia in hospitalized children.4

Study design

Interrupted time series analysis before and after pathway implementation.

Setting

370-bed tertiary care free-standing children’s hospital.

Synopsis

A multidisciplinary team was assembled, comprising physicians and nurses in hospital medicine, general pediatrics, emergency medicine, and nephrology. After a systematic review of the recent literature, a clinical algorithm and web-based training module were developed. Faculty in general pediatrics, hospital medicine, and emergency medicine were required to complete the module, while medical and surgical residents were encouraged but not required to complete the module. A maintenance IVF order set was created and embedded into all order sets previously containing IVF orders and was also available in stand-alone form.

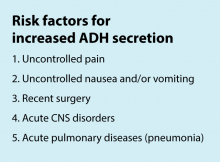

Inclusion criteria (“pathway eligible”) included being euvolemic and requiring IVF. Exclusion criteria included fluid status derangements, critical illness, severe serum sodium abnormalities (serum sodium ≥150 mEq/L or ≤130 mEq/L) use of TPN or ketogenic diet. In the order set, IVF composition was determined based on risk factors for increased ADH secretion. Inclusion of potassium in IVF was also determined by the pathway.

Over the 1-year study period, 11,602 pathway-eligible encounters in 10,287 patients were reviewed. Use of isotonic maintenance IVF increased significantly from 9.3% to 50.6%, while use of hypotonic fluids decreased from 94.2% to 56.6%. Use of potassium-containing IVF increased from 52.9% to 75.3%. Dysnatremia continued to occur due to hypotonic IVF use.

Bottom line

A combined clinical pathway and training module to standardize the composition of IVF is feasible, and results in increased use of isotonic and potassium-containing fluids.

Citation

Rooholamini S, Clifton H, Haaland W, et al. Outcomes of a clinical pathway to standardize use of maintenance intravenous fluids. Hosp Pediatr. 2017 Dec;7(12):703-9.

Dr. Chang is a pediatric hospitalist at Baystate Children’s Hospital in Springfield, Mass., and is the pediatric editor of The Hospitalist.

References

1. Holliday MA et al. The maintenance need for water in parenteral fluid therapy. Pediatrics 1957;19:823-32.

2. Friedman JN et al. Comparison of isotonic and hypotonic intravenous maintenance fluids: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:445-51.

3. Fuchs J et al. Current Issues in Intravenous Fluid Use in Hospitalized Children. Rev Recent Clin Trials. 2017;12:284-9.

4. McNab S et al. Isotonic versus hypotonic solutions for maintenance intravenous fluid administration in children. Cochrane Database. Syst Rev 2014:CD009457.

Clinical question

Can an evidence-based clinical pathway improve adherence to recent recommendations to use isotonic solutions for maintenance intravenous fluids in hospitalized children?

Background

The traditional teaching regarding composition of maintenance intravenous fluids (IVF) in children has been based on the Holliday-Segar method.1 Since its publication in Pediatrics in 1957, concerns have been raised regarding the risk of iatrogenic hyponatremia caused by giving hypotonic fluids determined by this method,2 especially in patients with an elevated risk of increased antidiuretic hormone (ADH) secretion.3 Multiple recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses have confirmed that isotonic IVF reduces the risk of hyponatremia in hospitalized children.4

Study design

Interrupted time series analysis before and after pathway implementation.

Setting

370-bed tertiary care free-standing children’s hospital.

Synopsis

A multidisciplinary team was assembled, comprising physicians and nurses in hospital medicine, general pediatrics, emergency medicine, and nephrology. After a systematic review of the recent literature, a clinical algorithm and web-based training module were developed. Faculty in general pediatrics, hospital medicine, and emergency medicine were required to complete the module, while medical and surgical residents were encouraged but not required to complete the module. A maintenance IVF order set was created and embedded into all order sets previously containing IVF orders and was also available in stand-alone form.

Inclusion criteria (“pathway eligible”) included being euvolemic and requiring IVF. Exclusion criteria included fluid status derangements, critical illness, severe serum sodium abnormalities (serum sodium ≥150 mEq/L or ≤130 mEq/L) use of TPN or ketogenic diet. In the order set, IVF composition was determined based on risk factors for increased ADH secretion. Inclusion of potassium in IVF was also determined by the pathway.

Over the 1-year study period, 11,602 pathway-eligible encounters in 10,287 patients were reviewed. Use of isotonic maintenance IVF increased significantly from 9.3% to 50.6%, while use of hypotonic fluids decreased from 94.2% to 56.6%. Use of potassium-containing IVF increased from 52.9% to 75.3%. Dysnatremia continued to occur due to hypotonic IVF use.

Bottom line

A combined clinical pathway and training module to standardize the composition of IVF is feasible, and results in increased use of isotonic and potassium-containing fluids.

Citation

Rooholamini S, Clifton H, Haaland W, et al. Outcomes of a clinical pathway to standardize use of maintenance intravenous fluids. Hosp Pediatr. 2017 Dec;7(12):703-9.

Dr. Chang is a pediatric hospitalist at Baystate Children’s Hospital in Springfield, Mass., and is the pediatric editor of The Hospitalist.

References

1. Holliday MA et al. The maintenance need for water in parenteral fluid therapy. Pediatrics 1957;19:823-32.

2. Friedman JN et al. Comparison of isotonic and hypotonic intravenous maintenance fluids: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:445-51.

3. Fuchs J et al. Current Issues in Intravenous Fluid Use in Hospitalized Children. Rev Recent Clin Trials. 2017;12:284-9.

4. McNab S et al. Isotonic versus hypotonic solutions for maintenance intravenous fluid administration in children. Cochrane Database. Syst Rev 2014:CD009457.

Clinical question

Can an evidence-based clinical pathway improve adherence to recent recommendations to use isotonic solutions for maintenance intravenous fluids in hospitalized children?

Background

The traditional teaching regarding composition of maintenance intravenous fluids (IVF) in children has been based on the Holliday-Segar method.1 Since its publication in Pediatrics in 1957, concerns have been raised regarding the risk of iatrogenic hyponatremia caused by giving hypotonic fluids determined by this method,2 especially in patients with an elevated risk of increased antidiuretic hormone (ADH) secretion.3 Multiple recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses have confirmed that isotonic IVF reduces the risk of hyponatremia in hospitalized children.4

Study design

Interrupted time series analysis before and after pathway implementation.

Setting

370-bed tertiary care free-standing children’s hospital.

Synopsis

A multidisciplinary team was assembled, comprising physicians and nurses in hospital medicine, general pediatrics, emergency medicine, and nephrology. After a systematic review of the recent literature, a clinical algorithm and web-based training module were developed. Faculty in general pediatrics, hospital medicine, and emergency medicine were required to complete the module, while medical and surgical residents were encouraged but not required to complete the module. A maintenance IVF order set was created and embedded into all order sets previously containing IVF orders and was also available in stand-alone form.

Inclusion criteria (“pathway eligible”) included being euvolemic and requiring IVF. Exclusion criteria included fluid status derangements, critical illness, severe serum sodium abnormalities (serum sodium ≥150 mEq/L or ≤130 mEq/L) use of TPN or ketogenic diet. In the order set, IVF composition was determined based on risk factors for increased ADH secretion. Inclusion of potassium in IVF was also determined by the pathway.

Over the 1-year study period, 11,602 pathway-eligible encounters in 10,287 patients were reviewed. Use of isotonic maintenance IVF increased significantly from 9.3% to 50.6%, while use of hypotonic fluids decreased from 94.2% to 56.6%. Use of potassium-containing IVF increased from 52.9% to 75.3%. Dysnatremia continued to occur due to hypotonic IVF use.

Bottom line

A combined clinical pathway and training module to standardize the composition of IVF is feasible, and results in increased use of isotonic and potassium-containing fluids.

Citation

Rooholamini S, Clifton H, Haaland W, et al. Outcomes of a clinical pathway to standardize use of maintenance intravenous fluids. Hosp Pediatr. 2017 Dec;7(12):703-9.

Dr. Chang is a pediatric hospitalist at Baystate Children’s Hospital in Springfield, Mass., and is the pediatric editor of The Hospitalist.

References

1. Holliday MA et al. The maintenance need for water in parenteral fluid therapy. Pediatrics 1957;19:823-32.

2. Friedman JN et al. Comparison of isotonic and hypotonic intravenous maintenance fluids: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:445-51.

3. Fuchs J et al. Current Issues in Intravenous Fluid Use in Hospitalized Children. Rev Recent Clin Trials. 2017;12:284-9.

4. McNab S et al. Isotonic versus hypotonic solutions for maintenance intravenous fluid administration in children. Cochrane Database. Syst Rev 2014:CD009457.

HM17 session summary: Focus on POCUS – Introduction to Point-of-Care Ultrasound for pediatric hospitalists

Presenters

Nilam Soni, MD, FHM; Thomas Conlon, MD; Ria Dancel, MD, FAAP, FHM; Daniel Schnobrich, MD

Summary

Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) is rapidly gaining acceptance in the medical community as a goal-directed examination that answers a specific diagnostic question or guides a bedside invasive procedure. Adoption by pediatric hospitalists is increasing, aided by multiple training pathways, opportunities for scholarship, and organization development.

The use of POCUS is increasing among nonradiologist physicians due to the expectation for perfection, desire for improved patient experience, and increased availability of ultrasound machines. POCUS is rapid and safe, and can be used serially to monitor, provide procedural guidance, and lead to initiation of appropriate therapies.

Training in POCUS in limited applications is possible in short periods of time. One recent study showed that approximately 40% of POCUS cases led to new findings or alteration of treatment. However, POCUS requires training, monitoring for competence, transparency of training/competence, and a QA process that supports the training. One solution at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia was to use American College of Emergency Physician guidelines for POCUS training.

Pediatric applications include guidance of bladder catheterization, identifying occult abscesses, diagnosis of pneumonia and associated parapneumonic effusion, and IV placement. More advanced applications include diagnosis of appendicitis, intussusception, and increased intracranial pressure. Novel applications conceived by nonradiologist physicians have included sinus ultrasound.

Initial training can be provided by “in-house experts,” such as pediatric ED physicians and PICU physicians. Alternatively, an on-site commercial course can be arranged for larger groups. Consideration should be given to mentorship, with comparison to formal imaging and/or clinical progression. Relationships with traditional imagers should be cultivated, as POCUS can potentially be misunderstood. In fact, formal US utilization has been found to increase once clinicals begin to use POCUS.

Key takeaways for HM

- Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) is rapidly being adopted by pediatric hospitalists.

- Pediatric applications are still being developed, but include guidance of bladder catheterization, identifying occult abscesses, diagnosis of pneumonia/associated effusions, and IV placement.

- Initial training can be provided by pediatric ED physicians/PICU physicians or an on-site commercial course can be arranged for larger groups.

- Relationships with radiologists should be established at the outset to avoid misunderstanding of POCUS.

Dr. Chang is a pediatric hospitalist at Baystate Children’s Hospital and is the pediatric editor of The Hospitalist.

Presenters

Nilam Soni, MD, FHM; Thomas Conlon, MD; Ria Dancel, MD, FAAP, FHM; Daniel Schnobrich, MD

Summary

Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) is rapidly gaining acceptance in the medical community as a goal-directed examination that answers a specific diagnostic question or guides a bedside invasive procedure. Adoption by pediatric hospitalists is increasing, aided by multiple training pathways, opportunities for scholarship, and organization development.

The use of POCUS is increasing among nonradiologist physicians due to the expectation for perfection, desire for improved patient experience, and increased availability of ultrasound machines. POCUS is rapid and safe, and can be used serially to monitor, provide procedural guidance, and lead to initiation of appropriate therapies.

Training in POCUS in limited applications is possible in short periods of time. One recent study showed that approximately 40% of POCUS cases led to new findings or alteration of treatment. However, POCUS requires training, monitoring for competence, transparency of training/competence, and a QA process that supports the training. One solution at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia was to use American College of Emergency Physician guidelines for POCUS training.

Pediatric applications include guidance of bladder catheterization, identifying occult abscesses, diagnosis of pneumonia and associated parapneumonic effusion, and IV placement. More advanced applications include diagnosis of appendicitis, intussusception, and increased intracranial pressure. Novel applications conceived by nonradiologist physicians have included sinus ultrasound.

Initial training can be provided by “in-house experts,” such as pediatric ED physicians and PICU physicians. Alternatively, an on-site commercial course can be arranged for larger groups. Consideration should be given to mentorship, with comparison to formal imaging and/or clinical progression. Relationships with traditional imagers should be cultivated, as POCUS can potentially be misunderstood. In fact, formal US utilization has been found to increase once clinicals begin to use POCUS.

Key takeaways for HM

- Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) is rapidly being adopted by pediatric hospitalists.

- Pediatric applications are still being developed, but include guidance of bladder catheterization, identifying occult abscesses, diagnosis of pneumonia/associated effusions, and IV placement.

- Initial training can be provided by pediatric ED physicians/PICU physicians or an on-site commercial course can be arranged for larger groups.

- Relationships with radiologists should be established at the outset to avoid misunderstanding of POCUS.

Dr. Chang is a pediatric hospitalist at Baystate Children’s Hospital and is the pediatric editor of The Hospitalist.

Presenters

Nilam Soni, MD, FHM; Thomas Conlon, MD; Ria Dancel, MD, FAAP, FHM; Daniel Schnobrich, MD

Summary

Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) is rapidly gaining acceptance in the medical community as a goal-directed examination that answers a specific diagnostic question or guides a bedside invasive procedure. Adoption by pediatric hospitalists is increasing, aided by multiple training pathways, opportunities for scholarship, and organization development.

The use of POCUS is increasing among nonradiologist physicians due to the expectation for perfection, desire for improved patient experience, and increased availability of ultrasound machines. POCUS is rapid and safe, and can be used serially to monitor, provide procedural guidance, and lead to initiation of appropriate therapies.

Training in POCUS in limited applications is possible in short periods of time. One recent study showed that approximately 40% of POCUS cases led to new findings or alteration of treatment. However, POCUS requires training, monitoring for competence, transparency of training/competence, and a QA process that supports the training. One solution at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia was to use American College of Emergency Physician guidelines for POCUS training.

Pediatric applications include guidance of bladder catheterization, identifying occult abscesses, diagnosis of pneumonia and associated parapneumonic effusion, and IV placement. More advanced applications include diagnosis of appendicitis, intussusception, and increased intracranial pressure. Novel applications conceived by nonradiologist physicians have included sinus ultrasound.

Initial training can be provided by “in-house experts,” such as pediatric ED physicians and PICU physicians. Alternatively, an on-site commercial course can be arranged for larger groups. Consideration should be given to mentorship, with comparison to formal imaging and/or clinical progression. Relationships with traditional imagers should be cultivated, as POCUS can potentially be misunderstood. In fact, formal US utilization has been found to increase once clinicals begin to use POCUS.

Key takeaways for HM

- Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) is rapidly being adopted by pediatric hospitalists.

- Pediatric applications are still being developed, but include guidance of bladder catheterization, identifying occult abscesses, diagnosis of pneumonia/associated effusions, and IV placement.

- Initial training can be provided by pediatric ED physicians/PICU physicians or an on-site commercial course can be arranged for larger groups.

- Relationships with radiologists should be established at the outset to avoid misunderstanding of POCUS.

Dr. Chang is a pediatric hospitalist at Baystate Children’s Hospital and is the pediatric editor of The Hospitalist.

Record Attendance, Key Issues Highlight Pediatric Hospital Medicine's 10th Anniversary

With a record number of attendees, Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2013 (PHM) swept into New Orleans last month, carrying with it unbridled enthusiasm about the past, present, and future.

Virginia Moyer, MD, MPH, vice president for maintenance of certification and quality for the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) and professor of pediatrics and chief of academic general pediatrics at Texas Children’s Hospital, delivered a keynote address to 700 attendees that focused on the challenges and opportunities of providing evidence-based, high-quality care in the hospital, as well as ABP’s role in meeting these challenges.

“If evidence-based medicine is an individual sport,” Dr. Moyer said, “then quality improvement is a team sport.”

Barriers to quality improvement (QI)— such as lack of will, lack of data, and lack of training—can be surmounted in a team environment, she said. ABP is continuing in its efforts to support QI education through its Maintenance of Certification (MOC) Part 4 modules, as well as other educational activities.

Other highlights of the 10th annual Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting:

- The addition of a new “Community Hospitalists” track was given high marks by those in attendance. It covered such topics as perioperative management of medically complex pediatric patients, community-acquired pneumonia, and osteomyelitis.

- A 10-year retrospective of pediatric hospital medicine was given by a panel of notable pediatric hospitalists, including Erin Stucky Fisher, MD, FAAP, MHM, chief of hospital medicine at Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego; Mary Ottolini, MD, MPH, chief of hospital medicine at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington; Jack Percelay, MD, MPH, FAAP, associate clinical professor at Pace University; and Daniel Rauch, MD, FAAP, pediatric hospitalist program director at the NYU School of Medicine in New York City. A host of new programs has been established by the PHM community, including the Quality Improvement Innovation Networks (QuIIN); the Value in Pediatrics (VIP) network; the International Network for Simulation-Based Pediatric Innovation, Research, and Education (INSPIRE); patient- and family-centered rounds; and the I-PASS Handoff Program. The panel also discussed future challenges, including reduction of unnecessary treatments, interfacing, and perhaps incorporating “hyphen hospitalists,” and learning from advances made by the adult HM community.

- The ever-popular “Top Articles in Pediatric Hospital Medicine” session was presented by H. Barrett Fromme, MD, associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Chicago, and Ben Bauer, MD, director of pediatric hospital medicine at Riley Hospital for Children at Indiana University Health in Indianapolis, which was met with raucous approval by the audience. The presentation not only educated those in attendance about the most cutting-edge pediatric literature, but it also included dance moves most likely to attract the opposite sex and clothing appropriate for the Australian pediatric hospitalist.

- The three presidents of the sponsoring societies—Thomas McInerney, MD, FAAP, of the American Academy of Pediatrics, David Keller, MD, of the Academic Pediatric Association, and Eric Howell, MD, SFHM, of SHM—presented each society’s contributions to the growth of PHM, as well as future areas for cooperative sponsorship. These include the development of the AAP Section of Hospital Medicine Library website, the APA Quality Scholars program, and SHM’s efforts to increase interest in hospital medicine in medical students and trainees. “Ask not what hospital medicine can do for you,” Dr. Howell implored, “ask what you can do for hospital medicine!”

- Members of the Joint Council of Pediatric Hospital Medicine (JCPHM) presented the recent recommendations of the council arising from an April 2013 meeting with the ABP in Chapel Hill, N.C. Despite acknowledgements that no decision will be met with uniform satisfaction by all the stakeholders, the JCPHM concluded that the path that would best advance the field of PHM, provide for high-quality care of hospitalized children, and ensure the public trust would be a two-year fellowship sponsored by ABP. This would ultimately lead to approved certification eligibility for fellowship graduates by the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS); it would also make provisions for “grandfathering” in current pediatric hospitalists. Concerns from med-peds, community hospitalists, and recent residency graduate communities were addressed by the panel.

- A recurrent theme of reducing unnecessary treatments, interventions, and, perhaps, hospitalizations was summarized eloquently by Alan Schroeder, MD, director of the pediatric ICU and chief of pediatric inpatient care at Santa Clara (Calif.) Valley Health. Barriers to reducing unnecessary care can be substantial, including pressure from families, pressure from colleagues, profit motive, and the “n’s of 1,” according to Dr. Schroeder. Ultimately, however, avoiding testing and treatments that have no benefit to children will improve care. “Ask, ‘How will this test benefit my patient?’ not ‘How will this test change management?’” Dr. Schroeder advised. TH

10: years in existence

720: attendees

220: scientific abstracts

9: tracks

Dr. Chang is The Hospitalist’s pediatric editor and a med-peds-trained hospitalist working at the University of California San Diego and Rady Children’s Hospital.

With a record number of attendees, Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2013 (PHM) swept into New Orleans last month, carrying with it unbridled enthusiasm about the past, present, and future.

Virginia Moyer, MD, MPH, vice president for maintenance of certification and quality for the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) and professor of pediatrics and chief of academic general pediatrics at Texas Children’s Hospital, delivered a keynote address to 700 attendees that focused on the challenges and opportunities of providing evidence-based, high-quality care in the hospital, as well as ABP’s role in meeting these challenges.

“If evidence-based medicine is an individual sport,” Dr. Moyer said, “then quality improvement is a team sport.”

Barriers to quality improvement (QI)— such as lack of will, lack of data, and lack of training—can be surmounted in a team environment, she said. ABP is continuing in its efforts to support QI education through its Maintenance of Certification (MOC) Part 4 modules, as well as other educational activities.

Other highlights of the 10th annual Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting:

- The addition of a new “Community Hospitalists” track was given high marks by those in attendance. It covered such topics as perioperative management of medically complex pediatric patients, community-acquired pneumonia, and osteomyelitis.

- A 10-year retrospective of pediatric hospital medicine was given by a panel of notable pediatric hospitalists, including Erin Stucky Fisher, MD, FAAP, MHM, chief of hospital medicine at Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego; Mary Ottolini, MD, MPH, chief of hospital medicine at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington; Jack Percelay, MD, MPH, FAAP, associate clinical professor at Pace University; and Daniel Rauch, MD, FAAP, pediatric hospitalist program director at the NYU School of Medicine in New York City. A host of new programs has been established by the PHM community, including the Quality Improvement Innovation Networks (QuIIN); the Value in Pediatrics (VIP) network; the International Network for Simulation-Based Pediatric Innovation, Research, and Education (INSPIRE); patient- and family-centered rounds; and the I-PASS Handoff Program. The panel also discussed future challenges, including reduction of unnecessary treatments, interfacing, and perhaps incorporating “hyphen hospitalists,” and learning from advances made by the adult HM community.

- The ever-popular “Top Articles in Pediatric Hospital Medicine” session was presented by H. Barrett Fromme, MD, associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Chicago, and Ben Bauer, MD, director of pediatric hospital medicine at Riley Hospital for Children at Indiana University Health in Indianapolis, which was met with raucous approval by the audience. The presentation not only educated those in attendance about the most cutting-edge pediatric literature, but it also included dance moves most likely to attract the opposite sex and clothing appropriate for the Australian pediatric hospitalist.

- The three presidents of the sponsoring societies—Thomas McInerney, MD, FAAP, of the American Academy of Pediatrics, David Keller, MD, of the Academic Pediatric Association, and Eric Howell, MD, SFHM, of SHM—presented each society’s contributions to the growth of PHM, as well as future areas for cooperative sponsorship. These include the development of the AAP Section of Hospital Medicine Library website, the APA Quality Scholars program, and SHM’s efforts to increase interest in hospital medicine in medical students and trainees. “Ask not what hospital medicine can do for you,” Dr. Howell implored, “ask what you can do for hospital medicine!”

- Members of the Joint Council of Pediatric Hospital Medicine (JCPHM) presented the recent recommendations of the council arising from an April 2013 meeting with the ABP in Chapel Hill, N.C. Despite acknowledgements that no decision will be met with uniform satisfaction by all the stakeholders, the JCPHM concluded that the path that would best advance the field of PHM, provide for high-quality care of hospitalized children, and ensure the public trust would be a two-year fellowship sponsored by ABP. This would ultimately lead to approved certification eligibility for fellowship graduates by the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS); it would also make provisions for “grandfathering” in current pediatric hospitalists. Concerns from med-peds, community hospitalists, and recent residency graduate communities were addressed by the panel.

- A recurrent theme of reducing unnecessary treatments, interventions, and, perhaps, hospitalizations was summarized eloquently by Alan Schroeder, MD, director of the pediatric ICU and chief of pediatric inpatient care at Santa Clara (Calif.) Valley Health. Barriers to reducing unnecessary care can be substantial, including pressure from families, pressure from colleagues, profit motive, and the “n’s of 1,” according to Dr. Schroeder. Ultimately, however, avoiding testing and treatments that have no benefit to children will improve care. “Ask, ‘How will this test benefit my patient?’ not ‘How will this test change management?’” Dr. Schroeder advised. TH

10: years in existence

720: attendees

220: scientific abstracts

9: tracks