User login

An insidious onset of symptoms

CASE Tremors, increasing anxiety

Ms. S, age 56, has a history of depression and anxiety.

The authors’ observations

The incidence of serotonin syndrome has increased because of increasing use of serotonergic agents.1-3 Although the severity could range from benign to life-threatening, the potential lethality combined with difficulty of diagnosis makes this condition of continued interest. Stimulation of the 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) receptor subtypes, specifically 5-HT1A and 5-HT2, are implicated in this syndrome.4,5

Serotonin syndrome is a clinical diagnosis with a triad of symptoms that includes mental status changes, autonomic hyperactivity, and neuromuscular abnormalities.1,2 However, because of the varied presentation and similarity to other syndromes such as NMS, serotonin syndrome often is undiagnosed.5

TREATMENT Discontinue fluoxetine

Several months after the fluoxetine increase, Ms. S's physical symptoms emerge. Several weeks later, she notices significant hypertension of 162/102 mm Hg by checking her blood pressure at home. She had no history of hypertension before taking fluoxetine. She then tells her psychiatrist she has been experiencing confusion, shakiness, loss of balance, forgetfulness, joint pain, sweating, and fatigue, along with worsening anxiety. The treatment team makes a diagnosis of serotonin syndrome and recommends discontinuing fluoxetine and starting cyproheptadine, 4 mg initially, and then repeating the cyproheptadine dose in several hours if her symptoms do not resolve. Approximately, 2.5 months after the serotonin syndrome reaction, Ms. S receives hydroxyzine, 10 mg every 8 hours, as needed for anxiety.

The authors’ observations

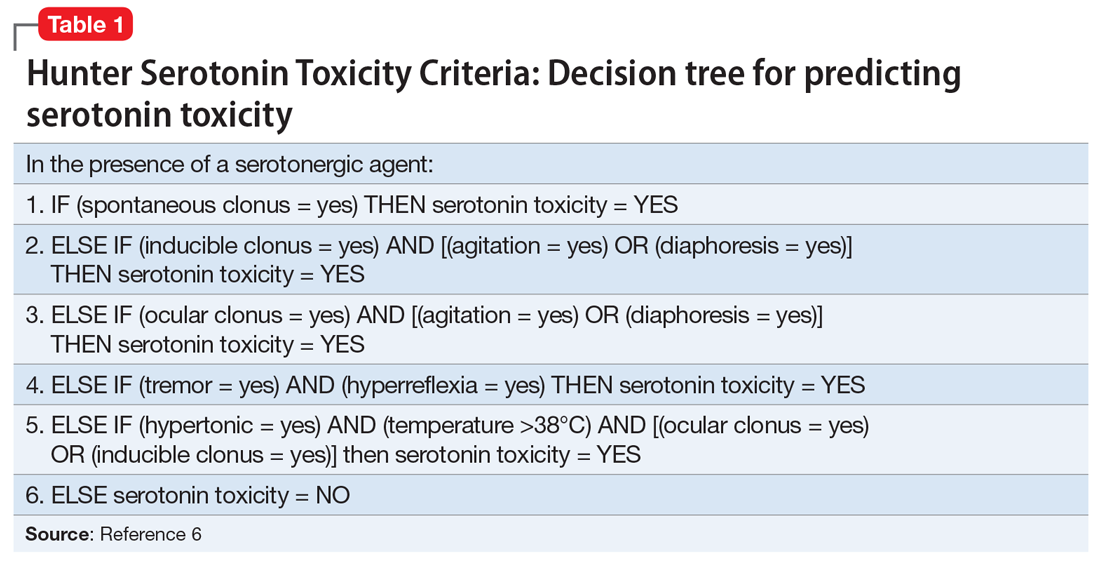

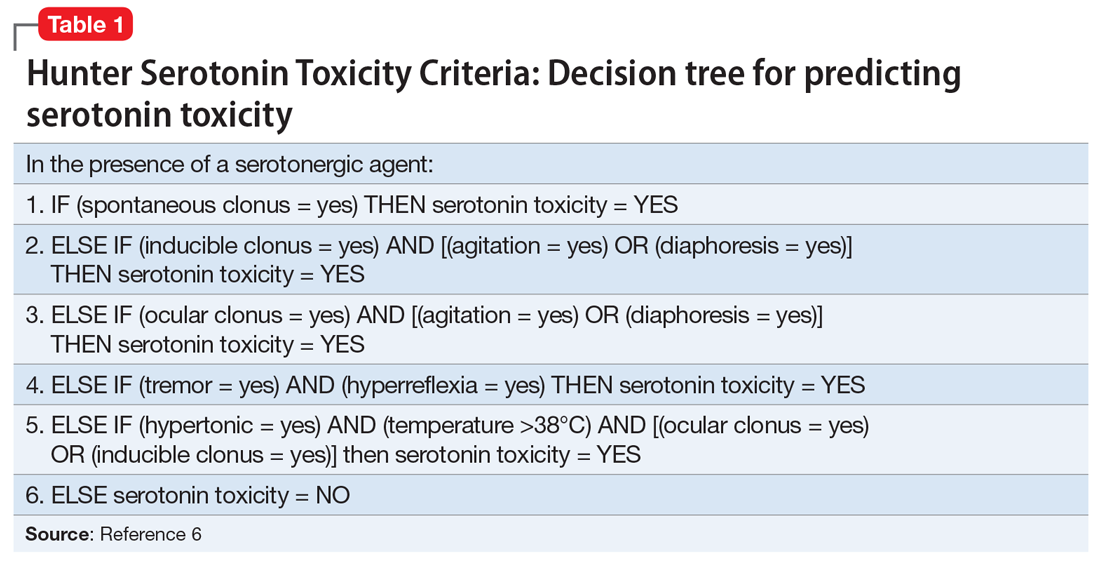

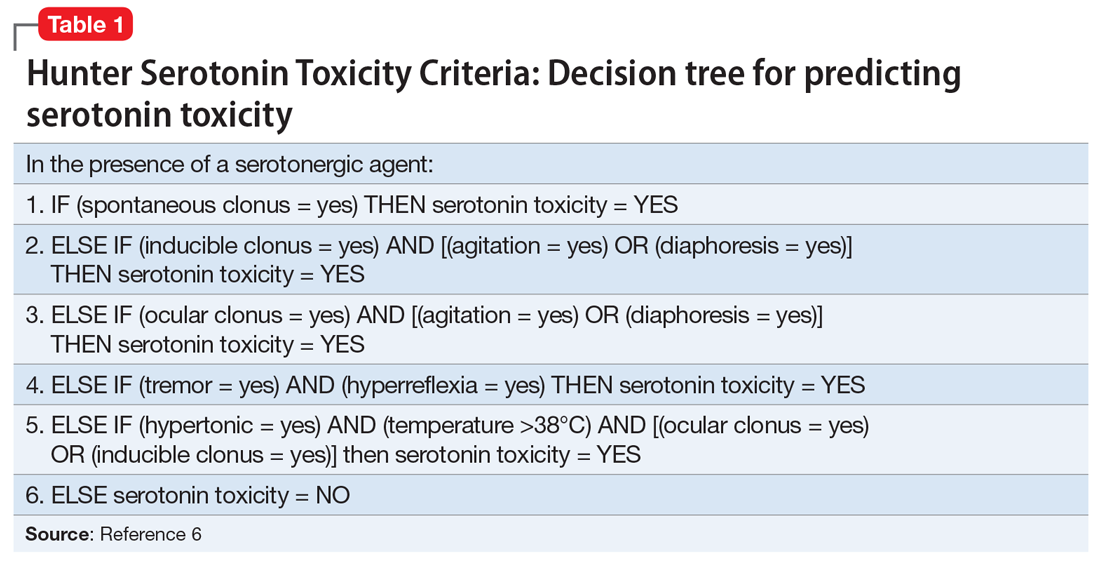

The diagnosis of serotonin syndrome is most accurately made using Hunter Serotonin Toxicity Criteria (Table 16). Because Ms. S had an insidious onset of symptoms, and treatment was initiated before full evaluation, it is unknown if she met Hunter criteria. To meet these criteria, a patient must have ≥1 of the following6:

- spontaneous clonus

- inducible clonus plus agitation or diaphoresis

- ocular clonus plus agitation or diaphoresis

- tremor plus hyperreflexia

- hypertonia plus temperature >38°C plus ocular or inducible clonus.

The Sternbach diagnostic criteria for serotonin syndrome (Table 23) is another commonly used tool.3 These criteria include the addition or increase of a serotonin agent and absence of substances or metabolic derangements that could account for symptoms and at least 3 of the following 10 symptoms3:

- mental status changes (confusion, hypomania)

- agitation

- myoclonus

- hyperreflexia

- diaphoresis

- shivering

- tremor

- diarrhea

- incoordination

- fever.

Continue to: Ms. S met the Sternbach diagnostic criteria...

Ms. S met the Sternbach diagnostic criteria for serotonin syndrome.

Ms. S was taking a single serotonin agent and initially had mild symptoms. More commonly, a patient who presents with serotonin syndrome has been receiving ≥2 serotonergic agents or toxic levels of a single agent, and these agents usually include a psychotropic medication such as a monoamine oxidase inhibitor, tricyclic antidepressant, or SSRI, as well as a medication from a different class, such as dextromethorphan, linezolid, tramadol, methylene blue, and/or St. John’s wort.1,7-13 However, in this case, Ms. S also was taking bupropion, a known inhibitor of cytochrome P450 2D6. Bupropion might have increased Ms. S’s fluoxetine levels.

Ms. S was a healthy, middle-age patient who took no medications other than those listed, had no medical comorbidities, and had a straightforward psychiatric history, which makes the diagnosis of serotonin syndrome clearer. However, other potential differential diagnoses, such as NMS, delirium tremens, and anticholinergic toxicity, might cloud the clinical picture. When differentiating NMS and serotonin syndrome, it is helpful to note whether a patient shows tremor, diarrhea, and myoclonus present in the absence of muscular, “lead-pipe” rigidity, which suggests a diagnosis of serotonin syndrome.2,3,5

[polldaddy:10279173]

The authors’ observations

Treating serotonin syndrome includes supportive care, discontinuing offending agents, administering benzodiazepines, and using a serotonin antagonist as an antidote for patients with moderate-to-severe cases. Cyproheptadine is an antihistaminergic medication with non-specific 5-HT1A and 5-HT2 antagonism. It is FDA-approved for specific allergic reactions, urticaria, and anaphylaxis adjunctive therapy, but not for serotonin syndrome. Case series support the use of cyproheptadine for acute management of serotonin syndrome, with rapid symptom improvement.4,7,14-18 We observed a similar outcome with Ms. S. Her significant autonomic symptoms resolved rapidly, although she experienced some residual, mild symptoms that took weeks to resolve.

Continue to: Because serotonergic agents...

Because serotonergic agents are used frequently and readily by primary care clinicians as well as psychiatrists, the ability to properly diagnose this syndrome is vital, particularly because severe cases can rapidly deteriorate.1,9,16,17 This presentation of a single serotonergic agent causing significant symptoms that worsened over months is not typical, but important to recognize as a patient begins to experience autonomic instability. As was the case with Ms. S, it is important to remain vigilant when changing dosages or adding medications. Symptoms of serotonin syndrome might be vague and difficult to diagnose, especially if the clinician is not aware of the variability of presentation of this syndrome. Cyproheptadine can be used safely and rapidly and should be considered a treatment option for serotonin syndrome.

OUTCOME Hypertension resolves

After her first dose of cyproheptadine, Ms. S’s blood pressure drops to 146/86 mm Hg. Three hours later, she repeats the cyproheptadine dose and her blood pressure drops to 106/60 mm Hg. She reports that her anxiety has lessened, although she is still tremulous. Overall, she says she feels better. She experiences improvement of her condition with a pharmacologic regimen of bupropion, gabapentin, and hydroxyzine.

Several weeks later, her health returns to baseline, with complete resolution of hypertension.

Bottom Line

Although serotonin syndrome is most commonly associated with co-administered serotonergic medications, symptoms can emerge with a single, moderately dosed agent. Treatment includes withdrawing the offending agent, and administering a serotonin antagonist. Mild cases of serotonin syndrome usually resolve.

Related Resources

- Turner AH, Kim JJ, McCarron RM. Differentiating serotonin syndrome and neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(2):30-36.

- Iqbal MM, Basil MJ, Kaplan J, et al. Overview of serotonin syndrome. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2012;24(4):310-318.

Drug Brand Names

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

Cyproheptadine • Periactin

Dextromethorphan • Benylin

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Hydroxyzine • Atarax

Linezolid • Zyvox

Tramadol • Ultram, Ryzolt

1. Mason PJ, Morris VA, Balcezak TJ. Serotonin syndrome: presentation of 2 cases and review of literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2000;79(4):201-209.

2. Boyer EW, Shannon M. The serotonin syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(11):1112-1120.

3. Sternbach H. The serotonin syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(6):705-713.

4. Graudins A, Stearman A, Chan B. Treatment of the serotonin syndrome with cyproheptadine. J Emerg Med. 1998;16(4):615-619.

5. Mills KC. Serotonin syndrome a clinical update. Crit Care Clin. 1997;13(4):763-783.

6. Dunkley EJ, Isbister GK, Sibbritt D, et al. The Hunter Serotonin Toxicity Criteria: simple and accurate diagnostic decision rules for serotonin toxicity. QJM. 2003;96:635-642.

7. Horowitz BZ, Mullins ME. Cyproheptadine for serotonin syndrome in an accidental pediatric sertraline ingestion. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1999;15(5):325-327.

8. Kolecki P. Isolated venlafaxine-induced serotonin syndrome. J Emerg Med. 1996;15:491-493.

9. Pan J, Shen W. Serotonin syndrome induced by low-dose venlafaxine. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37(2):209-211.

10. Hernández JL, Ramos FJ, Infante J, et al. Severe serotonin syndrome induced by mirtazapine monotherapy. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36(4):641-643.

11. Patel DD, Galarneau D. Serotonin syndrome with fluoxetine: two case reports. Ochsner J. 2016;16(4):554-557.

12. Frank C. Recognition and treatment of serotonin syndrome. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54(7):988-992.

13. Zuschlag ZD, Warren MW, K Schultz S. Serotonin toxicity and urinary analgesics: a case report and systematic literature review of methylene blue-induced serotonin syndrome. Psychosomatics. 2018;59(6):539-546.

14. Kapur S, Zipursky RB, Jones C, et al. Cyproheptadine: a potent in vivo serotonin antagonist. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(6):884.

15. Baigel GD. Cyproheptadine and the treatment of an unconscious patient with the serotonin syndrome. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2003;20(7):586-588.

16. Lappin RI, Auchincloss EL. Treatment of the serotonin syndrome with cyproheptadine. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1021-1022.

17. McDaniel WW. Serotonin syndrome: early management with cyproheptadine. Ann Pharmacother. 2001;35(7-8):870-873.

18. Kolecki P. Venlafaxine induced serotonin syndrome occurring after abstinence from phenelzine for more than two weeks. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1997;35(2):211-212.

CASE Tremors, increasing anxiety

Ms. S, age 56, has a history of depression and anxiety.

The authors’ observations

The incidence of serotonin syndrome has increased because of increasing use of serotonergic agents.1-3 Although the severity could range from benign to life-threatening, the potential lethality combined with difficulty of diagnosis makes this condition of continued interest. Stimulation of the 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) receptor subtypes, specifically 5-HT1A and 5-HT2, are implicated in this syndrome.4,5

Serotonin syndrome is a clinical diagnosis with a triad of symptoms that includes mental status changes, autonomic hyperactivity, and neuromuscular abnormalities.1,2 However, because of the varied presentation and similarity to other syndromes such as NMS, serotonin syndrome often is undiagnosed.5

TREATMENT Discontinue fluoxetine

Several months after the fluoxetine increase, Ms. S's physical symptoms emerge. Several weeks later, she notices significant hypertension of 162/102 mm Hg by checking her blood pressure at home. She had no history of hypertension before taking fluoxetine. She then tells her psychiatrist she has been experiencing confusion, shakiness, loss of balance, forgetfulness, joint pain, sweating, and fatigue, along with worsening anxiety. The treatment team makes a diagnosis of serotonin syndrome and recommends discontinuing fluoxetine and starting cyproheptadine, 4 mg initially, and then repeating the cyproheptadine dose in several hours if her symptoms do not resolve. Approximately, 2.5 months after the serotonin syndrome reaction, Ms. S receives hydroxyzine, 10 mg every 8 hours, as needed for anxiety.

The authors’ observations

The diagnosis of serotonin syndrome is most accurately made using Hunter Serotonin Toxicity Criteria (Table 16). Because Ms. S had an insidious onset of symptoms, and treatment was initiated before full evaluation, it is unknown if she met Hunter criteria. To meet these criteria, a patient must have ≥1 of the following6:

- spontaneous clonus

- inducible clonus plus agitation or diaphoresis

- ocular clonus plus agitation or diaphoresis

- tremor plus hyperreflexia

- hypertonia plus temperature >38°C plus ocular or inducible clonus.

The Sternbach diagnostic criteria for serotonin syndrome (Table 23) is another commonly used tool.3 These criteria include the addition or increase of a serotonin agent and absence of substances or metabolic derangements that could account for symptoms and at least 3 of the following 10 symptoms3:

- mental status changes (confusion, hypomania)

- agitation

- myoclonus

- hyperreflexia

- diaphoresis

- shivering

- tremor

- diarrhea

- incoordination

- fever.

Continue to: Ms. S met the Sternbach diagnostic criteria...

Ms. S met the Sternbach diagnostic criteria for serotonin syndrome.

Ms. S was taking a single serotonin agent and initially had mild symptoms. More commonly, a patient who presents with serotonin syndrome has been receiving ≥2 serotonergic agents or toxic levels of a single agent, and these agents usually include a psychotropic medication such as a monoamine oxidase inhibitor, tricyclic antidepressant, or SSRI, as well as a medication from a different class, such as dextromethorphan, linezolid, tramadol, methylene blue, and/or St. John’s wort.1,7-13 However, in this case, Ms. S also was taking bupropion, a known inhibitor of cytochrome P450 2D6. Bupropion might have increased Ms. S’s fluoxetine levels.

Ms. S was a healthy, middle-age patient who took no medications other than those listed, had no medical comorbidities, and had a straightforward psychiatric history, which makes the diagnosis of serotonin syndrome clearer. However, other potential differential diagnoses, such as NMS, delirium tremens, and anticholinergic toxicity, might cloud the clinical picture. When differentiating NMS and serotonin syndrome, it is helpful to note whether a patient shows tremor, diarrhea, and myoclonus present in the absence of muscular, “lead-pipe” rigidity, which suggests a diagnosis of serotonin syndrome.2,3,5

[polldaddy:10279173]

The authors’ observations

Treating serotonin syndrome includes supportive care, discontinuing offending agents, administering benzodiazepines, and using a serotonin antagonist as an antidote for patients with moderate-to-severe cases. Cyproheptadine is an antihistaminergic medication with non-specific 5-HT1A and 5-HT2 antagonism. It is FDA-approved for specific allergic reactions, urticaria, and anaphylaxis adjunctive therapy, but not for serotonin syndrome. Case series support the use of cyproheptadine for acute management of serotonin syndrome, with rapid symptom improvement.4,7,14-18 We observed a similar outcome with Ms. S. Her significant autonomic symptoms resolved rapidly, although she experienced some residual, mild symptoms that took weeks to resolve.

Continue to: Because serotonergic agents...

Because serotonergic agents are used frequently and readily by primary care clinicians as well as psychiatrists, the ability to properly diagnose this syndrome is vital, particularly because severe cases can rapidly deteriorate.1,9,16,17 This presentation of a single serotonergic agent causing significant symptoms that worsened over months is not typical, but important to recognize as a patient begins to experience autonomic instability. As was the case with Ms. S, it is important to remain vigilant when changing dosages or adding medications. Symptoms of serotonin syndrome might be vague and difficult to diagnose, especially if the clinician is not aware of the variability of presentation of this syndrome. Cyproheptadine can be used safely and rapidly and should be considered a treatment option for serotonin syndrome.

OUTCOME Hypertension resolves

After her first dose of cyproheptadine, Ms. S’s blood pressure drops to 146/86 mm Hg. Three hours later, she repeats the cyproheptadine dose and her blood pressure drops to 106/60 mm Hg. She reports that her anxiety has lessened, although she is still tremulous. Overall, she says she feels better. She experiences improvement of her condition with a pharmacologic regimen of bupropion, gabapentin, and hydroxyzine.

Several weeks later, her health returns to baseline, with complete resolution of hypertension.

Bottom Line

Although serotonin syndrome is most commonly associated with co-administered serotonergic medications, symptoms can emerge with a single, moderately dosed agent. Treatment includes withdrawing the offending agent, and administering a serotonin antagonist. Mild cases of serotonin syndrome usually resolve.

Related Resources

- Turner AH, Kim JJ, McCarron RM. Differentiating serotonin syndrome and neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(2):30-36.

- Iqbal MM, Basil MJ, Kaplan J, et al. Overview of serotonin syndrome. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2012;24(4):310-318.

Drug Brand Names

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

Cyproheptadine • Periactin

Dextromethorphan • Benylin

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Hydroxyzine • Atarax

Linezolid • Zyvox

Tramadol • Ultram, Ryzolt

CASE Tremors, increasing anxiety

Ms. S, age 56, has a history of depression and anxiety.

The authors’ observations

The incidence of serotonin syndrome has increased because of increasing use of serotonergic agents.1-3 Although the severity could range from benign to life-threatening, the potential lethality combined with difficulty of diagnosis makes this condition of continued interest. Stimulation of the 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) receptor subtypes, specifically 5-HT1A and 5-HT2, are implicated in this syndrome.4,5

Serotonin syndrome is a clinical diagnosis with a triad of symptoms that includes mental status changes, autonomic hyperactivity, and neuromuscular abnormalities.1,2 However, because of the varied presentation and similarity to other syndromes such as NMS, serotonin syndrome often is undiagnosed.5

TREATMENT Discontinue fluoxetine

Several months after the fluoxetine increase, Ms. S's physical symptoms emerge. Several weeks later, she notices significant hypertension of 162/102 mm Hg by checking her blood pressure at home. She had no history of hypertension before taking fluoxetine. She then tells her psychiatrist she has been experiencing confusion, shakiness, loss of balance, forgetfulness, joint pain, sweating, and fatigue, along with worsening anxiety. The treatment team makes a diagnosis of serotonin syndrome and recommends discontinuing fluoxetine and starting cyproheptadine, 4 mg initially, and then repeating the cyproheptadine dose in several hours if her symptoms do not resolve. Approximately, 2.5 months after the serotonin syndrome reaction, Ms. S receives hydroxyzine, 10 mg every 8 hours, as needed for anxiety.

The authors’ observations

The diagnosis of serotonin syndrome is most accurately made using Hunter Serotonin Toxicity Criteria (Table 16). Because Ms. S had an insidious onset of symptoms, and treatment was initiated before full evaluation, it is unknown if she met Hunter criteria. To meet these criteria, a patient must have ≥1 of the following6:

- spontaneous clonus

- inducible clonus plus agitation or diaphoresis

- ocular clonus plus agitation or diaphoresis

- tremor plus hyperreflexia

- hypertonia plus temperature >38°C plus ocular or inducible clonus.

The Sternbach diagnostic criteria for serotonin syndrome (Table 23) is another commonly used tool.3 These criteria include the addition or increase of a serotonin agent and absence of substances or metabolic derangements that could account for symptoms and at least 3 of the following 10 symptoms3:

- mental status changes (confusion, hypomania)

- agitation

- myoclonus

- hyperreflexia

- diaphoresis

- shivering

- tremor

- diarrhea

- incoordination

- fever.

Continue to: Ms. S met the Sternbach diagnostic criteria...

Ms. S met the Sternbach diagnostic criteria for serotonin syndrome.

Ms. S was taking a single serotonin agent and initially had mild symptoms. More commonly, a patient who presents with serotonin syndrome has been receiving ≥2 serotonergic agents or toxic levels of a single agent, and these agents usually include a psychotropic medication such as a monoamine oxidase inhibitor, tricyclic antidepressant, or SSRI, as well as a medication from a different class, such as dextromethorphan, linezolid, tramadol, methylene blue, and/or St. John’s wort.1,7-13 However, in this case, Ms. S also was taking bupropion, a known inhibitor of cytochrome P450 2D6. Bupropion might have increased Ms. S’s fluoxetine levels.

Ms. S was a healthy, middle-age patient who took no medications other than those listed, had no medical comorbidities, and had a straightforward psychiatric history, which makes the diagnosis of serotonin syndrome clearer. However, other potential differential diagnoses, such as NMS, delirium tremens, and anticholinergic toxicity, might cloud the clinical picture. When differentiating NMS and serotonin syndrome, it is helpful to note whether a patient shows tremor, diarrhea, and myoclonus present in the absence of muscular, “lead-pipe” rigidity, which suggests a diagnosis of serotonin syndrome.2,3,5

[polldaddy:10279173]

The authors’ observations

Treating serotonin syndrome includes supportive care, discontinuing offending agents, administering benzodiazepines, and using a serotonin antagonist as an antidote for patients with moderate-to-severe cases. Cyproheptadine is an antihistaminergic medication with non-specific 5-HT1A and 5-HT2 antagonism. It is FDA-approved for specific allergic reactions, urticaria, and anaphylaxis adjunctive therapy, but not for serotonin syndrome. Case series support the use of cyproheptadine for acute management of serotonin syndrome, with rapid symptom improvement.4,7,14-18 We observed a similar outcome with Ms. S. Her significant autonomic symptoms resolved rapidly, although she experienced some residual, mild symptoms that took weeks to resolve.

Continue to: Because serotonergic agents...

Because serotonergic agents are used frequently and readily by primary care clinicians as well as psychiatrists, the ability to properly diagnose this syndrome is vital, particularly because severe cases can rapidly deteriorate.1,9,16,17 This presentation of a single serotonergic agent causing significant symptoms that worsened over months is not typical, but important to recognize as a patient begins to experience autonomic instability. As was the case with Ms. S, it is important to remain vigilant when changing dosages or adding medications. Symptoms of serotonin syndrome might be vague and difficult to diagnose, especially if the clinician is not aware of the variability of presentation of this syndrome. Cyproheptadine can be used safely and rapidly and should be considered a treatment option for serotonin syndrome.

OUTCOME Hypertension resolves

After her first dose of cyproheptadine, Ms. S’s blood pressure drops to 146/86 mm Hg. Three hours later, she repeats the cyproheptadine dose and her blood pressure drops to 106/60 mm Hg. She reports that her anxiety has lessened, although she is still tremulous. Overall, she says she feels better. She experiences improvement of her condition with a pharmacologic regimen of bupropion, gabapentin, and hydroxyzine.

Several weeks later, her health returns to baseline, with complete resolution of hypertension.

Bottom Line

Although serotonin syndrome is most commonly associated with co-administered serotonergic medications, symptoms can emerge with a single, moderately dosed agent. Treatment includes withdrawing the offending agent, and administering a serotonin antagonist. Mild cases of serotonin syndrome usually resolve.

Related Resources

- Turner AH, Kim JJ, McCarron RM. Differentiating serotonin syndrome and neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(2):30-36.

- Iqbal MM, Basil MJ, Kaplan J, et al. Overview of serotonin syndrome. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2012;24(4):310-318.

Drug Brand Names

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

Cyproheptadine • Periactin

Dextromethorphan • Benylin

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Hydroxyzine • Atarax

Linezolid • Zyvox

Tramadol • Ultram, Ryzolt

1. Mason PJ, Morris VA, Balcezak TJ. Serotonin syndrome: presentation of 2 cases and review of literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2000;79(4):201-209.

2. Boyer EW, Shannon M. The serotonin syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(11):1112-1120.

3. Sternbach H. The serotonin syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(6):705-713.

4. Graudins A, Stearman A, Chan B. Treatment of the serotonin syndrome with cyproheptadine. J Emerg Med. 1998;16(4):615-619.

5. Mills KC. Serotonin syndrome a clinical update. Crit Care Clin. 1997;13(4):763-783.

6. Dunkley EJ, Isbister GK, Sibbritt D, et al. The Hunter Serotonin Toxicity Criteria: simple and accurate diagnostic decision rules for serotonin toxicity. QJM. 2003;96:635-642.

7. Horowitz BZ, Mullins ME. Cyproheptadine for serotonin syndrome in an accidental pediatric sertraline ingestion. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1999;15(5):325-327.

8. Kolecki P. Isolated venlafaxine-induced serotonin syndrome. J Emerg Med. 1996;15:491-493.

9. Pan J, Shen W. Serotonin syndrome induced by low-dose venlafaxine. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37(2):209-211.

10. Hernández JL, Ramos FJ, Infante J, et al. Severe serotonin syndrome induced by mirtazapine monotherapy. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36(4):641-643.

11. Patel DD, Galarneau D. Serotonin syndrome with fluoxetine: two case reports. Ochsner J. 2016;16(4):554-557.

12. Frank C. Recognition and treatment of serotonin syndrome. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54(7):988-992.

13. Zuschlag ZD, Warren MW, K Schultz S. Serotonin toxicity and urinary analgesics: a case report and systematic literature review of methylene blue-induced serotonin syndrome. Psychosomatics. 2018;59(6):539-546.

14. Kapur S, Zipursky RB, Jones C, et al. Cyproheptadine: a potent in vivo serotonin antagonist. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(6):884.

15. Baigel GD. Cyproheptadine and the treatment of an unconscious patient with the serotonin syndrome. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2003;20(7):586-588.

16. Lappin RI, Auchincloss EL. Treatment of the serotonin syndrome with cyproheptadine. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1021-1022.

17. McDaniel WW. Serotonin syndrome: early management with cyproheptadine. Ann Pharmacother. 2001;35(7-8):870-873.

18. Kolecki P. Venlafaxine induced serotonin syndrome occurring after abstinence from phenelzine for more than two weeks. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1997;35(2):211-212.

1. Mason PJ, Morris VA, Balcezak TJ. Serotonin syndrome: presentation of 2 cases and review of literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2000;79(4):201-209.

2. Boyer EW, Shannon M. The serotonin syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(11):1112-1120.

3. Sternbach H. The serotonin syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(6):705-713.

4. Graudins A, Stearman A, Chan B. Treatment of the serotonin syndrome with cyproheptadine. J Emerg Med. 1998;16(4):615-619.

5. Mills KC. Serotonin syndrome a clinical update. Crit Care Clin. 1997;13(4):763-783.

6. Dunkley EJ, Isbister GK, Sibbritt D, et al. The Hunter Serotonin Toxicity Criteria: simple and accurate diagnostic decision rules for serotonin toxicity. QJM. 2003;96:635-642.

7. Horowitz BZ, Mullins ME. Cyproheptadine for serotonin syndrome in an accidental pediatric sertraline ingestion. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1999;15(5):325-327.

8. Kolecki P. Isolated venlafaxine-induced serotonin syndrome. J Emerg Med. 1996;15:491-493.

9. Pan J, Shen W. Serotonin syndrome induced by low-dose venlafaxine. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37(2):209-211.

10. Hernández JL, Ramos FJ, Infante J, et al. Severe serotonin syndrome induced by mirtazapine monotherapy. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36(4):641-643.

11. Patel DD, Galarneau D. Serotonin syndrome with fluoxetine: two case reports. Ochsner J. 2016;16(4):554-557.

12. Frank C. Recognition and treatment of serotonin syndrome. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54(7):988-992.

13. Zuschlag ZD, Warren MW, K Schultz S. Serotonin toxicity and urinary analgesics: a case report and systematic literature review of methylene blue-induced serotonin syndrome. Psychosomatics. 2018;59(6):539-546.

14. Kapur S, Zipursky RB, Jones C, et al. Cyproheptadine: a potent in vivo serotonin antagonist. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(6):884.

15. Baigel GD. Cyproheptadine and the treatment of an unconscious patient with the serotonin syndrome. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2003;20(7):586-588.

16. Lappin RI, Auchincloss EL. Treatment of the serotonin syndrome with cyproheptadine. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1021-1022.

17. McDaniel WW. Serotonin syndrome: early management with cyproheptadine. Ann Pharmacother. 2001;35(7-8):870-873.

18. Kolecki P. Venlafaxine induced serotonin syndrome occurring after abstinence from phenelzine for more than two weeks. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1997;35(2):211-212.